Abstract

Background

Assessment of mental health in schools has garnered increased interest in recent years. Children spend a large proportion of their waking hours in schools. Teachers can act as gatekeepers by playing a key role in identifying children with mental health difficulties in the classroom and making the necessary onward referrals to external services. The prevalence of mental health difficulties, their impact on schooling (and beyond) and the importance of early intervention means that it is incumbent on schools to identify and support potentially affected children.

Aims

Previous reviews focused on mental health interventions in schools; however, this review focuses on the assessment of mental health in schools and on teachers' perceptions of this, as such a review is still lacking. Therefore, the study fills a gap in the existing literature while also providing new, highly relevant evidence that may inform policy making in this area.

Composition of studies included in this review

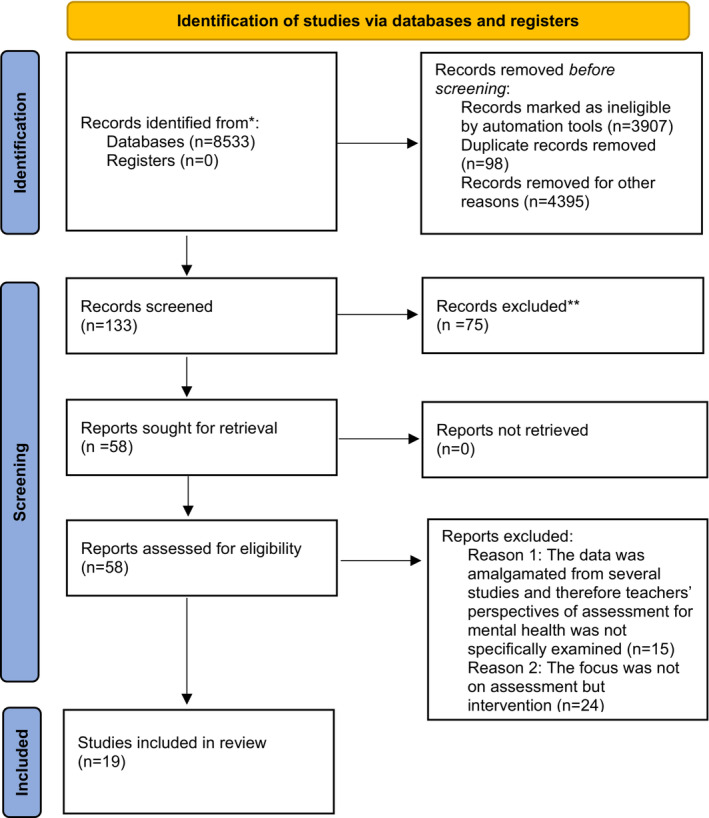

This review included 19 studies. Five studied teachers exclusively at primary/elementary level, and seven focused on secondary level, while six included both primary and secondary teachers. Three studies employed mixed methods, ten were primarily qualitative studies, and five were primarily quantitative.

Methods

Bronfenbrenner's (The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design, Harvard University Press, 1979) framework, adapted by Harvest (How can EPs best support secondary school staff to work effectively with children and young people who experience social, emotional and mental health difficulties? 2018), which includes the mature version of the theory (Tudge et al., 2009, J. Fam. Theory Rev., 1, 198), was used to analyse the literature.

Results

Results found that lack of training in assessment of mental health and ‘role conflict’ were key barriers; some teachers attributed this to their lack of knowledge, skills and confidence in the area.

Conclusion

Implications for practice and research are discussed in relation to the importance of sustained training both pre‐service and in‐service.

Keywords: assessment, barriers, mental health, teachers

INTRODUCTION

A large number of children globally may be at risk of developing social, emotional and behavioural difficulties (SEBD), and this has received increased attention in recent years. Loades and Mastroyannopoulou (2010) highlight that, internationally, children and adolescents with SEBD make up approximately 20% per cent of the school‐age population. For these children, early identification has the potential to mitigate against adverse outcomes both in school and beyond (Carr, 2015; Cook & Ruhaak, 2014; Landrum et al., 2014; Mundschenk & Simpson, 2014). Considering the proportion of their waking hours that children spend there, schools have a crucial role in identifying children with SEBD (Levitt et al., 2007). Furthermore, there is an increasing body of literature which states that emotional well‐being and academic performance in schools are not mutually exclusive and that emotional well‐being provides the foundation from which effective learning can be built (Cefai et al., 2016; Moilanen et al., 2010).

This review examines teachers' perceptions of the barriers to assessment of children who may be experiencing SEBDs, an important topic, considering their centrality to the process. According to the Gateway Provider Model (GPM; Stiffman et al., 2004), the teacher can be the ‘gateway provider’, who identifies children in need of external services. Therefore, teachers can play a key role in identifying children with mental health difficulties in the classroom and making the necessary onward referrals to external services as well as providing the appropriate in‐school supports (Meldrum et al., 2009; Ní Chorcora & Swords, 2021).

Little is known about how schools are identifying children with mental health difficulties in order to liaise with and referring them on to external services. In several countries, the role of schools in mental health is also unclear and changes to policies in this area suggest the school's role is changing (Cefai et al., 2021). This report also acknowledges that the school system needs to play a central role given that children's and young peoples ‘mental health needs are becoming more evident and demanding’ and that social and emotional education for these children is essential (p. 5). Furthermore, this report outlines that children and young people have a right to physical and mental health and that a whole school approach to mental health is necessary to accommodate this. However, recent research shows that there are a wide variety of assessment practices, both structured (e.g., checklists and rating scales) and unstructured (e.g., observation), which are employed by schools (Dwyer et al., 2006; Ford & Finning, 2020). For the purpose of this review, all such practices which aim to formally or informally identify mental health needs of children are included.

Teachers understanding of health and their training

In order to identify and support children with SEBDs, teachers need to understand how they present in school and the classroom, how to assess them and how to support them. Debattista and Mangion (2019) study found that ‘teachers who supported students with SEBD were more aware of strategies to be used in the classroom than those who never supported such students’ (p. 300). This suggests that teacher training can increase teachers' confidence in assessing mental health in the classroom. For example, in one Australian study, researchers asked primary and secondary pre‐service teachers to complete a 13‐week training unit on dealing with sensitive issues, including mental health. Of this cohort of students, (N = 164), seventy‐two completed pre and post measures. Prior to the course, only 29% of the participants felt confident and competent in identifying those presenting with mental health difficulties; however, this increased to 80% post‐course (Lynagh et al., 2010). Furthermore, pre‐service teacher training on mental health is not consistent across countries (Koller & Bertel, 2006). If the curricula of teacher education courses are reviewed, then it is apparent that identifying and working with children with SEBD is conceptualized differently as well as being given different weight. This kind of work can be conceptualized as just dealing with children who need ‘Special and Inclusive Education’ (DCU, Ireland, and Macquarie and Griffith University, Australia), or as part of general well‐being (Cardiff Metropolitan University, Wales), or understanding individuals (Aberdeen, Scotland). The training for this work might focus on the positive aspects, such as positive behaviour support (Leigh University, United States) or creating a positive learning environment (University of Malta, Malta). Furthermore, credits for these modules vary from 2.5 to 15 credits. State et al. (2019) US study further illustrates the inconsistencies that exist in mental health across courses, even within countries. This research sought to gather data from a random sample of 41 US colleges, although N = 26 participated and agreed to share their syllabi on social, emotional and behavioural (SEB) topics in pre‐service teacher training. A startling 14% of the sample had no SEB topics on their syllabi. The research found that overall SEB was not taught in in a comprehensive manner. This shows that inconsistencies that exist are not just across countries but within countries also.

Rationale for this systematic review

Early intervention is crucial when identifying children with SEBDs. Governments are rolling out numerous mental health initiatives for schools. However, it is unclear in what proportion of schools assessment of mental health and identification of children with mental health difficulties are occurring and which procedures are followed. Williams et al. (2007) state that ‘there is a limited understanding of how children are referred in schools for further treatment and conversely what barriers prevent the identification and the referral process from being more effective’ (p. 97). Furthermore, there has been a lack of research in this area since their article was published over a decade ago. For example, there is a dearth of research, which examines teachers' knowledge of children with SEBDs and their perceptions of identifying and working with children with mental health difficulties. This was noted, for instance, in Shillingford and Karlin's (2014) US study with pre‐service teachers, which found that more work needed to be done to improve pre‐service teacher's knowledge of SEBD and to provide strategies for identifying and working with children with SEBDs. Previous reviews have focused on teachers' implementation of mental health interventions (Franklin et al., 2012), the use and feasibility of universal screening programmes (Anderson et al., 2017; Soneson et al., 2020) and teachers' perceptions of children who present with mental health difficulties in schools (Armstrong, 2013). The above reviews focus on interventions, school resources/programmes and on how children with mental health difficulties are perceived by teachers; what is still lacking is a systematic review, which focuses on teachers' perceptions of the assessment of children's mental health in schools. Therefore, a systematic review of the literature on the barriers to assessment of mental health is timely. A systematic review was chosen as one of the goals of this research is to provide evidence to inform policy making and identify gaps in the existing literature (Temple University Libraries, 2022). This was also done to ensure all scholarly research in this area was included. According to Temple University Libraries, this allows the review to be transparent, replicable and rigorous which is important from a policy perspective and to contribute to the research in this area (Temple University Libraries, 2022).

There are multiple personnel in a school, but teachers, especially at primary level, have the most contact with the children and know them best. It is therefore germane to start with exploring these issues from the perspective of teachers. The current review focuses on the assessment of mental health in schools, focusing solely on teachers' perceptions of this. This review takes a systematic approach to identifying the relevant literature (Moher et al., 2009).

Theoretical framework

Bronfenbrenner's (1979) framework, adapted by Harvest (2018), which includes the mature version of the theory (Tudge et al., 2009) was used to analyse the literature. Harvest's framework places the teacher at the centre, unlike Bronfenbrenner's (1979), which places the child or young person at the centre; however, the same systems are referred to in both frameworks. It is acknowledged in the literature that Bronfenbrenner's Process‐Person‐Context‐Time ‘involves the interplay of the theory's crucial concepts’ (Tudge et al., 2016, p. 422). This allows us to understand the synergistic relation between these proximal processes (i.e., the individual (teacher)) and the context (e.g., school, other teaching colleagues, parents and children). This framework is used to illuminate the dynamic relationship between teachers' perceptions of assessment of mental health in schools and the different systems which influence this (Harvest, 2018). It also promotes an understanding of the wider school ecology and its impact on teachers' ability to identify and work with children with SEBD, and, in turn, the impact of interventions on the child (Armstrong, 2013, p. 741).

Purpose of current review

The purpose of this paper is to report on a systematic review of the literature, which examines teachers' perceptions of the barriers to assessment of mental health in schools.

METHOD

Nature and scope of the review and databases used

The search terms used in this review are outlined in Table 1. This review focused on scholarly literature (i.e., peer‐reviewed articles, books and published and unpublished theses) from a range of international sources. In order to ensure all the key literature was identified, the following specific journals were hand‐searched, given their specific relevance to this review: School Mental Health and Emotional Behavioural Difficulties. The primary database used was ScopusEBSCOhost (within this, the ERIC APA Psycinfo and APA PsycArticles databases were searched). These were used because of the need for literature, which spans both education studies and the social sciences.

TABLE 1.

Search strategy

| Teachers' perceptions of the barriers and enablers to assessment of mental health in schools |

|---|

| ((anxiety OR "selective mutism" OR "panic disorder" OR phobia OR "mental health" OR "internalising disorder" OR "internalizing disorder" OR "behavioral disorder" OR "behavioural disorder" OR "behavioral emotional and social difficulties" OR "behavioural emotional and social difficulties" OR "social emotional and behavioral difficulties" OR "social emotional and behavioural difficulties") AND ((TITLE‐ABS KEY (assess* OR identif* OR recogni* OR screen OR "screening measure" OR "test")) AND (TITLE‐ABS‐KEY (child* OR pupil* OR student* OR kid*) AND (TITLE‐ABS‐KEY) ("Primary School" OR "Elementary School" OR "primary education" OR "Elementary Education" OR teacher* OR teacher* OR tutor* OR class* OR "School‐based" OR "School based")) AND (TITLE‐ABS‐KEY) (barrier* OR problem* OR difficult* OR challenge* OR enabler*)) AND (TITLE‐ABSKEY (perception OR attitude OR belief OR opinion OR expectation))) AND (LIMIT‐TO (LANGUAGE, "English")) |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Due to limited time and resources, only English language studies were reviewed. Studies, which were conducted in countries classified as developing economies, were also excluded, given that mental health care is often very different in those countries (World Health Organization, 2019). Studies were excluded where data from teachers were amalgamated with those of other school practitioners, including psychologists and social workers. These were removed as it was difficult to disentangle which information related to teachers and which related to other school participants. They were also excluded if they did not specifically examine teachers' perspectives on assessment for mental health, for example if a study only compared teacher's ratings to students and did not gather information on their perspectives on the barriers to assessment of mental health, it was removed. Studies focusing on principals, pre‐service teachers, pre‐school teachers, review/discussion papers and studies focusing on mental health intervention in schools were also excluded. The decision was made to focus on in‐service teachers for the following reasons. First, this cohort spends much of the school day with the children. Secondly, a large number of countries both in the EU and North America use a tiered approach to mental health identification (i.e., where the teacher plays a key role in this first tier by identifying mental health difficulties and escalating them), which places teachers as gatekeepers to these external services (Cefai et al., 2018). Thirdly, the GPM states that for a teacher to identify ‘at risk’ children to external services, the process may be influenced by three key factors ‘their perception of need, and their knowledge of resources, and their environment’, and therefore, examining teachers perceptions is crucial (Stiffman et al., 2004, p. 189). In some cases, it was not initially clear whether a research paper focusing on teachers supporting students' mental health in schools included assessment and intervention or only assessment. To shed light on the research question, a careful review of full texts was conducted to ensure that they answered this question (i.e., in relation to assessment of mental health).

Methodological framework

The review was guided by a methodological framework (Moher et al., 2009) for conducting scoping studies, which was last updated on 5 April 2021. This ‘PRISMA’ framework was used due its systematic nature and is outlined in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Adapted preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses (PRISMA) flowchart of review process and study selection

RESULTS

Overview of included papers

Thirty‐nine abstracts met the initial inclusion criteria, and of these, 19 met the final inclusion criteria. Those studies which were excluded primarily due to the fact that data from teachers were amalgamated with other school practitioners. Several of these studies are small‐scale and qualitative in their orientation (three mixed methods, eleven qualitative and five quantitative studies) in their orientation; however, when these findings are considered together, a more coherent picture of the current international landscape emerges. The literature, which met the final inclusion criteria, is set out in Table 2. The number of participants ranged from 8 to 771, eight of the studies were carried out in the United Kingdom, four in the United States, three in Australia, with and one each from Norway, Turkey and the Netherlands. Of the 19 studies, six studied teachers exclusively at primary/elementary level and seven focused on secondary level, while six included both primary and secondary teachers. Each system (Harvest's, 2018) is presented and analysed separately in order to highlight the individual nature of different barriers.

TABLE 2.

Literature which satisfied the inclusion criteria for this review

| Author(s) | Location | Stated methodology and research method | Sample size who participated | Application of Harvest's ecological framework to teachers' perceptions of barriers to assessment of mental health in schools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childs‐Fegredo et al. (2021) | UK |

Qualitative: Semi‐structured interviews |

n = 26 teachers (this included teaching assistants, class teachers and head teachers) across four primary schools |

INDIVIDUAL: Fear over expectation of their role. Lack of confidence MACROSYSTEM: Training‐ burden on teachers. Lack of time and resources. Reliability of universal screening MICROSYSTEM: Poor sign posting to services MESOSYSTEM: Parental stigma and parental consent |

| Corcoran and Finney (2015) | UK |

Qualitative: Semi‐structured interviews |

n = 15 secondary school teachers with a focus on senior staff (i.e., Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning coordinators, head teachers, a Special Educational Needs Coordinator SENCO) |

INDIVIDUAL: Role conflict. Fear over expectation of their role MACROSYSTEM: Lack of training |

| Danby and Hamilton (2016) | UK | Mixed methods: semi‐structured interviews and a questionnaire |

n = 18 from two primary schools Nine teachers, seven teaching assistants and two additional learning needs coordinators |

INDIVIDUAL: Role conflict. Lack of knowledge MACROSYSTEM: Lack of training EXOSYSTEM: Mixed consensus –some found external services ‘easy’ or ‘moderately easy’ to access while some did not |

| Ekornes (2015) | Norway |

Mixed methods: electronic survey and focus groups |

n = 15 teachers from three different secondary school participated in the focus groups. n = 771 completed the survey (172 of these worked in primary schools while the rest of the responses were from teachers working in secondary schools) |

INDIVIDUAL: Lack of knowledge MACROSYSTEM: Lack of training. Training needed on confidentiality procedures MESOSYSTEM: Parental stigma |

| Goodman and Burton (2010) (published) | UK |

Qualitative: Semi‐structured interviews |

n = 8 secondary school teachers, teaching across four regions of England |

MACROSYSTEM: Training is inadequate. Little or no specialist training EXOSYSTEM: Lack of availability of external services to conduct further assessment. Difficulties obtaining information about students |

| Gowers et al. (2004) | UK | Quantitative: electronic survey | n = 148 primary school teachers' in a rural district. All teachers were the SENCO in their school |

MACROSYSTEM: Lack of training. Mixed consensus over the helpfulness of training INDIVIDUAL: Lack of knowledge EXOSYSTEM: Children Adolescents Mental Health service (CAMHS) and its referral system viewed as inadequate |

| Graham et al. (2011) | Australia | Quantitative: electronic survey | n = 508 teachers from both primary (49%) and secondary school (46%) and some teachers teaching across both |

INDIVIDUAL: Role conflict MACROSYSTEM: Inadequate pre‐service teacher training |

| Hackett et al. (2010) | UK | Quantitative: online questionnaire | n = 403. Nine primary schools were randomly selected from a large urban area | MACROSYSTEM: The need for support a with primarily externalizing difficulties, however they also addressed internalizing difficulties (e.g., emotional withdrawal) |

| Harvest (2018) (unpublished) | UK |

Qualitative: Two focus groups |

n = 14 school staff across two mainstream secondary schools |

INDIVIDUAL: Lack of knowledge and skills. Role conflict. Stress from taking on the student's mental health difficulties. MACROSYSTEM: Lack of training MICROSYSTEM: School ethos |

| Hinchliffe and Campbell (2016) | Australia |

Qualitative: Semi‐structured interviews |

n = 20 teachers from two primary schools |

INDIVIDUAL: Role conflict MACROSYSTEM: Societal expectations |

| Mooij and Smeets (2009) | Netherlands |

Qualitative: Semi‐structured interviews |

n = 35 teachers, from primary and secondary schools, from five different regions of the Netherlands | MACROSYSTEM and EXOSYSTEM: Insufficient knowledge given to teachers about children |

| Papandrea and Winefield (2011) | Australia | Mixed methods: online questionnaire (closed and open‐ended questions) | n = 152 secondary teachers from 17 South Australian schools |

MACROSYSTEM: Lack of training, particularly in identifying internalizing symptoms in children. Policy (pressure to test) EXOSYSTEM: Inadequate available and sustained access to mental health supports INDIVIDUAL: Lack of knowledge. Role conflict (uncomfortable with the expectation to identify children without training). Teacher stress in managing difficulties |

| Reinke et al. (2011) | United States of America (USA) | Quantitative: online questionnaire | n = 292 elementary teachers across five school districts (rural suburban and urban) |

MACROSYSTEM: Lack of training MICROSYSTEM: Lack of school funding EXOSYSTEM: Insufficient number of mental health professionals MESOSYSTEM: Lack of parental support INDIVIDUAL: Lack of confidence and knowledge |

| Rothi et al. (2008) | UK | Qualitative: semi‐structured interviews | n = 30 teachers Eight participants taught in primary schools, 13 in secondary schools, 8 in special schools and one in a Montessori school |

INDIVIDUAL: Role conflict. Stress, and frustration due to lack of knowledge MACROSYSTEM: Lack of training in assessment (particularly in identifying less visible disorders). Inadequate training for pre‐service teachers |

| Sezer (2017) | Turkey |

Qualitative: Case study |

n = 24 teachers, teaching in primary, secondary and high school | INDIVIDUAL: Teacher stress due to lack of confidence and knowledge in understanding the problem |

| Shelemy et al. (2019) | UK |

Qualitative: Nine focus groups |

n = 49 teachers from nine secondary schools |

MACROSYSTEM: Societal expectations. Lack of training. No consensus over the quality of training received. INDIVIDUAL: Role conflict. Fear of making things worse. MESOSYSTEM: Frustration with parents who are dismissive and difficult to get on board EXOSYSTEM: Lack of communication from CAMHS |

| Walter et al. (2006) | USA | Quantitative: electronic survey | n = 119 elementary teachers across six schools |

MACROSYSTEM: Lack of training, large class sizes and lack of time in the school day. Inadequate pre‐service teacher training INDIVIDUAL: Lack of confidence MESOSYSTEM: Lack of parental involvement |

| Westling (2010) | USA | Quantitative: questionnaire (hard copy delivered by post) | n = 70 teachers (38 special education and 32 general education teachers) from one south‐eastern state in the United States. This included those teaching in kindergarten, primary and secondary schools | MACROSYSTEM: Mixed views over the adequacy of professional preparation training they received in assessment |

| Williams et al. (2007) | USA |

Qualitative: Two focus groups |

n = 19 teachers from two elementary schools |

INDIVIDUAL: Teachers spoke about feeling overwhelmed. Fear over societal expectations MESOSYSTEM: Frustration with parents MICROSYSTEM: School ethos. Lack of time in the school day for mental health assessment |

Although training is not mentioned explicitly, this is implied.

Synthesizing analyses

Macrosystem

Training

In terms of the macrosystem, lack of training was considered a barrier in 15 studies (Corcoran & Finney, 2015; Danby & Hamilton, 2016; Ekornes, 2015; Reinke et al., 2011). Of these, six were cross‐sectional studies using questionnaires, six were qualitative studies involving interviews and focus groups, and three studies used a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods. In the overwhelming majority of the studies, teachers were keen to receive further training. In one large‐scale US study, teachers were asked to list the top three areas they identified for additional training. The first was strategies for working with children with externalizing behaviour problems, the second was training in recognizing and understanding mental health issues in children, and the third was training in classroom management (Reinke et al., 2011). This is noteworthy, given the range of potential areas across education which could have been chosen. An Australian study (Papandrea & Winefield, 2011), in which a random sample of teachers (n = 152) from 28 secondary schools completed an online questionnaire, sought to explore why referral rates for internalizing problems are so low. In this study, four main categories of concern emerged: ‘Insufficient mental health‐related training’ (n = 63), ‘Inadequate available and sustained supports’ (n = 49); referrals prioritized instead to children who are ‘More disruptive in classrooms’ (i.e., externalizing problems; n = 36) and ‘Teacher stress’ (n = 21, p. 227).

Diversity of opinion on training was identified in one US study by Westling (2010) where 70 teachers completed a questionnaire. The results showed mixed views on the adequacy of professional preparation training the teachers had received in ‘data collection and assessment’, with 60% of special education teachers and 39% of general education teachers reporting that they had adequate or extensive preparation in this area (Westling, 2010). This study did not draw a distinction between primary and secondary teachers. Furthermore, the questionnaire used in this study looked exclusively at challenging behaviour. This raises questions as to whether those working with children with special educational needs received more training in this area and were more adequately prepared. Although the overwhelming majority of studies address lack of training as a barrier, some studies identified specific needs in relation to further training and these are outlined below.

Some studies noted that the quality of training was not sufficiently specialized. Participants explained that training needed to include information on warning signs or risk factors (Ekornes, 2015; Goodman & Burton, 2010; Shelemy et al., 2019). There were also calls from participants in one of the UK studies for this training to be accredited (Shelemy et al., 2019). Some studies criticized pre‐service teacher training for not equipping them with the necessary skills to identify children who were experiencing mental health difficulties (Graham et al., 2011; Rothi et al., 2008; Walter et al., 2006). In other studies, there were mixed views on whether teachers had received sufficient professional pre‐service or in‐service training to deal with mental health difficulties in the classroom (Goodman & Burton, 2010; Papandrea & Winefield, 2011; Westling, 2010). Rothi et al. (2008) noted that teachers need training in self‐assessment of their own mental health. One study also called for training in confidentiality procedures (Ekornes, 2015). Other studies, however, noted that teachers require support specifically with identifying internalizing difficulties (Papandrea & Winefield, 2011; Rothi et al., 2008).

National policy guidelines

In total, six studies raised specific concerns about increased pressure on academic testing due to national policies (Corcoran & Finney, 2015; Papandrea & Winefield, 2011; Reinke et al., 2011; Rothi et al., 2008; Walter et al., 2006; Williams et al., 2007) and argued that this left no time for assessing mental health (Walter et al., 2006; Williams et al., 2007). The above studies were conducted in the United Kingdom, the United States and Australia. They highlight that challenges imposed by national policy are not limited to one specific country. Of these, two were cross‐sectional studies using questionnaires, three were qualitative studies involving interviews and focus groups, and one used a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods. Corcoran and Finney (2015) found that teachers reported a constant professional challenge in ‘trying to make sense of competing legislative and policy pressures’ in the context of mental health promotion and early intervention (p. 111). Reinke et al. (2011) commented that there needs to be calls for government polices to mandate this training to address this.

Individual

Role conflict

Ten articles incorporated discussion on the teacher's role. Of these, two were cross‐sectional studies using questionnaires, six were qualitative studies involving interviews and focus groups, and two used a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods. A key issue that emerged from teachers' narratives in seven of these studies was the fear that solving mental health problems was becoming their role (Childs‐Fegredo et al., 2021; Corcoran & Finney, 2015; Danby & Hamilton, 2016; Graham et al., 2011; Harvest, 2018; Hinchliffe & Campbell, 2016; Papandrea & Winefield, 2011; Rothi et al., 2008; Shelemy et al., 2019). In their eyes, they were teachers and their role was purely academic (Shelemy et al., 2019). As one teacher remarked, ‘I certainly didn't sign up for this. I'm totally out of my depth. We receive no training but are expected to deal with so many problems’ (Papandrea & Winefield, 2011, p. 227). Six of the ten studies were from the United Kingdom, while two were conducted in Australia. In contrast to this, in two of the US studies, the majority of teachers believed monitoring that mental health to be part of their role (Reinke et al., 2011; Walter et al., 2006). This would suggest teachers' attitudes to their role in mental health differ across countries.

Harvest's (2018) UK study found that many teachers see their role as more holistic, including mental health promotion and early intervention, and believe they have a duty of care towards children. As one teacher from this UK study put it: ‘we're teachers of young people who need support in all ways because I never come to school just to sit and teach lessons’ (Harvest, 2018, p. 110). There were mixed views, not just between studies but also even within studies. As Harvest noted, ‘all teaching staff at School 2 endorsed the sentiment that we foster that kind of idea of caring about them as individuals not just as like kind of exam stats’. In contrast to this, another teacher remarked, ‘I'm expected to teach, I'm expected to deliver really good lessons, I'm expected to, you know; look after the educational needs of my children. And as much as I'd love to support them pastorally, I physically don't have the capacity’ (Harvest, 2018, pp. 109–110).

However, it is clear that many teachers still view the teaching of core curricular subjects as their primary focus. In one study, for example, teachers acknowledged that it is important to make an onward referral, if anxiety was affecting the students academically. This makes one wonder if students who are still achieving academically, but who are experiencing high levels of anxiety may slip through the cracks (Hinchliffe & Campbell, 2016).

Teachers' mental health

Two studies demonstrate that opinions were divided in terms of the impact of a teacher's own mental health on their ability to identify children with mental health difficulties in the classroom. Of these, one was a cross‐sectional study conducted in Australia using questionnaires, and the other was a qualitative study from the United Kingdom involving focus groups. One study commented on how, if a teacher had experienced mental health difficulties, they may be more aware of the signs or risk factors to look out for (Harvest, 2018). In contrast to this, a different study stressed the importance of teachers' own sense of mental health as an important factor in their ability to identify and support these students with difficulties (Graham et al., 2011).

Knowledge, skills, confidence and fears of teachers

Fifteen studies referred to knowledge, skills, confidence and fears of teachers as barriers to assessment of mental health needs of children. Of these, four were cross‐sectional studies using questionnaires, seven were qualitative studies involving interviews and focus groups, one was a case study (using interviews), and three used a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods, suggesting that it is a robust finding. Teachers also consistently reported feelings of ‘incompetence, frustration and helplessness’ (Rothi et al., 2008, p. 1227). Their feelings of incompetence were often referred to indirectly, as teachers spoke about their lack of knowledge and skills in this area, their lack of understanding of mental health and their low confidence in their skills in this area. One study outlined that many teachers felt that they did not have the knowledge (41%) or the skills (36%) to meet the mental health needs of children in their class (Reinke et al., 2011), although in this study, teachers' knowledge and skills are spoken about more broadly, and not specifically in relation to assessment.

Sezer (2017) examined the views of teachers with less than 3 years' experience (these were referred to as novice teachers in this study). The results demonstrated that novice teachers struggled with disruptive behaviour and this caused stress and anxiety in almost half of such teachers. Some also acknowledged that trying to understand the problem was challenging. Moreover, a Norwegian study found that, irrespective of teaching experience, teachers found it difficult to disentangle what constitute ‘normal mood swings’ from more severe problems (Ekornes, 2015, p. 200). In contrast to these studies, one study in the United States which used two focus groups (across two schools) found that most teachers were comfortable identifying children with mental health problems (particularly externalizing difficulties) but felt they did not have enough time to do so (Williams et al., 2007).

Teachers spoke about a fear of making things worse, noting, for instance, that ‘we don't know when to leave things or when to let things go or when to intervene’ (Shelemy et al., 2019, p. 104). The fear of having the ‘responsibility over the well‐being of their students’ was also addressed in several studies (Shelemy et al., 2019, p. 106). Another fear that was noted by teachers was the expectation that ‘we should have all the answers’ (Williams et al., 2007, p. 100).

Mesosystem

Parents

Nine studies referred to parents as an important component of the assessment process as they can not only act as barriers to assessment (given they are the gatekeepers for giving consent) but also as enablers by identifying their child as presenting with difficulties, prompting the need for onward referral. These results were found across quantitative (n = 2), qualitative (n = 6) and mixed methods studies (n = 1). Several studies expressed frustration with parents who were dismissive and difficult to get on board (Reinke et al., 2011; Shelemy et al., 2019; Walter et al., 2006; Williams et al., 2007). One Norwegian study highlighted that parents could act as barriers if they are reluctant to address mental health difficulties due to their own stigma (Ekornes, 2015), while a US study spoke directly about how parents were a barrier, due to the difficulty in obtaining consent and getting them to follow‐up and attend the services (Williams et al., 2007).

Microsystem

School ethos

Four studies, all qualitative utilizing focus groups, identified school ethos as important. There was a ready acknowledgement from teachers in these studies that the school culture and school ethos can act as a barrier if mental health resources are not prioritized or if time during the school day is not set aside for mental health (Childs‐Fegredo et al., 2021; Harvest, 2018; Shelemy et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2007).

Exosystem

External mental health services

Six studies referred to the role of external services. Of these, one was a cross‐sectional study using questionnaires, four were qualitative studies involving interviews and focus groups, and one used a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods. External services were viewed by the participants in a majority of these studies as inadequate (Goodman & Burton, 2010), and reference was made to lack of clear sign posting to allow teachers to navigate within available services (Childs‐Fegredo et al., 2021). Some teachers commented that there was a lack of ‘appropriate and prompt assessment’ (Goodman & Burton, 2010, p. 226). Teachers were unsure when they were ‘allowed access’, particularly where a further assessment may have been warranted (Gowers et al., 2004, p. 229). Several studies stated that information on students can be difficult to access (Goodman & Burton, 2010; Mooij & Smeets, 2009; Shelemy et al., 2019). This highlights that challenges for teachers in assessment of mental health go beyond the school setting and that difficulties accessing external services may make teachers less likely to make onward referrals in the future.

Summary

There are some clear trends in the literature, which provide worthwhile insights on understanding the barriers to assessment of mental health in schools, as identified by teachers. The overwhelming majority of studies found that lack of training was a barrier and studies outlined different recommendations for this training (e.g., training in confidentiality procedures and in identifying risk factors). Another key finding was the divided opinion among teachers on their role in the assessment of mental health in schools, with some feeling they had an important role to play, and others seeing it as something outside their core duties. In several studies, teachers spoke about their lack of knowledge, skills and confidence in this area and their fear of making things worse. There were also mixed views on the adequacy of external services. Finally, both parents and schools (through their ethos) were identified as clear barriers to the assessment process.

DISCUSSION

This review explored teachers' perceptions of the barriers to assessment of mental health in schools. This review is particularly timely given the psychosocial impact that the SARS‐CoV‐2 (coronavirus disease 2019; previously 2019‐nCoV) pandemic has had on children, including the increasing difficulties faced by children with pre‐existing SEBDs (Ghosh et al., 2020; Youngminds, 2020). Despite the paucity of studies, a number of key themes emerged across different educational systems. At the individual level, the key factors outlined were role conflict, fear, teachers own mental health experiences, lack of knowledge, and the need for skills and confidence. Within the microsystem, the school ethos emerged as important while both parents and colleagues played important roles within the mesosystem. Studies also demonstrated the inadequacy of external services (an element of the exosystem) and the lack of training, the importance of policies and the impact of societal expectations (macrosystem).

Role conflict

A significant issue addressed by Ekornes (2015) was that teachers are becoming an underutilized resource in schools if they are unable to identify the students who are at risk and make appropriate referrals. However, this review demonstrated that there were mixed views over ‘this apparent expansion of the role of teachers around mental health’ (Kidger et al., 2009, p. 11). Corcoran and Finney (2015) outline that some teachers view mental health as ‘peripheral to the purpose of education’ (p. 105). Kidger et al. (2009) argue that educating pupils about ‘good emotional health and identifying and referring on those who need specialist support, may be viewed as newer additions to the traditional teaching role’ (p. 12). Given that the lines for some teachers are blurred around their perceived role in mental health, this suggests the need for policy to explicitly clarify the role of teachers.

Lack of teacher confidence

A key theme that emerged was the lack of teachers' confidence in their knowledge and skills in assessment of mental health. Teachers felt that the ultimate impact of mental health education programmes is dependent on a number of teacher‐specific characteristics. In line with (Bandura, 1977) beliefs on self‐efficacy, a teachers' beliefs, ‘about a students' mental health, together with perceptions of their own capability to recognise and deal with mental health‐related issues, will potentially influence their responses and hence the success or otherwise of mental health education programmes’, (Graham et al., 2011, p. 481). Kidger et al.'s (2009) study found that when teachers' own mental health has been at risk or in danger, such teachers may be less able and/or willing to respond to (recognize or support) pupils with mental health difficulties. This is interesting given that this review found that there were mixed views between studies as to whether a teacher's own state of mental health may hinder or assist in the assessment process. In Kidger et al.'s (2009) study, a teacher reported having a mental health difficulty (in the past), which made them more in‐tune in identifying children with difficulties. However, it is clear that there is a distinction between research on teachers with a mental health difficulty (current) and those that have had one in the past. Furthermore, the stigma attached to mental health difficulties may be different in different countries, which again may affect teachers' attitudes to mental health (Krendl & Pescosolido, 2020).

Parental consent and confidentiality

It is important that schools obtain ‘active parental consent’ from all families during the assessment process (Levitt et al., 2007, p. 183), and in most countries, this is a legal requirement. Furthermore, an important consideration for teachers and mental health professionals is that the data that are shared with parents are clearly outlined and presented to them in ways that foster understanding. This appears to be paramount, as it may influence not just parental awareness of children's possible difficulties but also whether parents' access or give consent for the referral pathways to be followed (Dvorsky et al., 2014). Connecting with mental health services is often a long process for parents, and this may act as a barrier to engaging with available services (Cohen et al., 2012; Iskra et al., 2015). However, some scholars have suggested a possible solution and recommended that services ‘engage with families placed on a waiting list rather than just requiring them to confirm their intention to continue waiting for services [as this] is an effective strategy to increase an uptake of initial appointment and subsequent engagement with services’ (Anderson et al., 2017, p. 171). Policies, which are aimed at promoting the mental health of parents, are also salient (Ford et al., 2007).

Lack of training and National Policies

Government policies were identified as barriers to assessment of mental health in a number of countries. In particular, reference was made to the increased pressure brought on by academic testing. The overwhelming majority of studies found that lack of training was a barrier, and this training may also assist by building on teachers' confidence in assessment of mental health. It is evident from this review that this barrier was not unique to one education system but is apparent in teachers working in different education systems at different levels within those systems. Furthermore, the three studies which criticized pre‐service teacher training were not unique to one country, and they were based on research in the United Kingdom, the United States and Australia. This highlights the importance of teachers' perspectives, as they are on the front line, working with children with mental health difficulties.

Assessment of the quality of the literature

It is beyond the scope of this review to provide a detailed commentary on all aspects of each study reviewed. Moreover, only six countries were represented across the 18 studies. Due to the small number of studies found, it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions. Furthermore, some of the studies' methods were lacking in detail and should be interpreted with caution. For example, survey questions had response items, which could be considered to be somewhat limiting. In one US study, teachers were asked to rank their beliefs about the biggest mental health problems (Walter et al., 2006); however, this scale used solely focused on externalizing problems. Another study outlined that nine schools were invited to participate in interviews and of these seven declined, suggesting difficulties in generalizing the results even within countries (Danby & Hamilton, 2016).

Although two qualitative studies spoke about how teachers' mental health affects their assessment of children's mental health, none of the studies in this review explicitly asked this question. The majority of studies in this review used convenience (Danby & Hamilton, 2016), or purposive sampling (Goodman & Burton, 2010). Although some studies drew from a random sample (Hackett et al., 2010; Papandrea & Winefield, 2011), these were the exception. Teachers may be more likely to participate if they have a more positive attitude towards mental health in schools. Four studies in this review (22%) used focus groups. The results from these studies need to be interpreted with caution given that participants may be reluctant to voice their own opinions, if they are working within a specific school culture (Barbour & Kitzinger, 1998; Gibbs, 1997).

Limitations of the literature review

Cultural differences are likely to impact on how different countries and indeed different areas within countries view mental health and this may have impacted the findings of this review. Furthermore, it is likely that there may be cultural differences in determining the role that assessment of mental health plays in initial teacher education programmes. This review excluded studies, which included data from practitioners (e.g., counsellors and psychologists) alongside teachers, as these results were amalgamated. It is possible that studies, which included these teachers, may have had relevant findings. Given that a small number of articles met the inclusion criteria for this search, it is difficult to make generalizations from this review. Furthermore, there may have been unpublished work, which was overlooked.

Further research

It is clear from the literature that schools play an important role in mental health and that school staff ‘are at the nexus between education and psychology’ (Corcoran & Finney, 2015, p. 98). In light of this, there is a need for further research in this area. This review demonstrates that there are few (English language) studies from a teacher's perspective and there is a need for research across a range of countries. Further investigation into specific barriers or enablers to mental health, which distinguish between research at primary and secondary level, are needed. In several studies, which included teachers working in primary and secondary schools, the results were often combined, making it difficult to disentangle specific challenges within sectors. Only one of the papers that met the inclusion criteria for this review outlined that assessment measures/screeners/available tests (in schools) were a barrier to their assessment of mental health. It is noteworthy that this study asked teachers about universal screening specifically, whereas the other studies did not. This is surprising given that universal school‐based screening is a hotly debated topic in recent years (Dowdy et al., 2010; Humphrey & Wigelsworth, 2016; Lane et al., 2012). Therefore, further research should explore what measures teachers are using and their perception of these. Teacher require education not just in supporting children but also in supporting their own social and emotional competence and resilience (Cefai et al., 2021). Given that teachers can act as gatekeepers, by potentially playing a key role in identifying children with mental health difficulties and making the necessary onward referrals, further research needs to be conducted on how best the school system can support teachers. Yoder (2014) recommends educators engage in self‐assessment and develop their own mental health skills. However, little is known about how (if at all) a teacher's well‐being may influence their role in the assessment process.

Educational and clinical implications

These findings highlight the need for compulsory training in assessment of mental health, which spans both pre‐service and in‐service teachers. As Conway (2014) has noted, ‘professional development for teachers needs to be sustained, not a one off occurrence’ (p. 434). One of the main recommendations for Educational Psychology practice arising from this review is the need to empower teachers by providing training in identifying mental health difficulties. Psychologists are well placed to deliver this training at school level. This training may empower teachers to engage on a more equal basis in consultation, when referring a child who may need further help, as some teachers may not see assessment of mental health as part of their role (O'Farrell & Kinsella, 2018, p. 325). Harding et al. (2019) found that better teacher well‐being was associated with fewer psychological difficulties among students. Investing in training in assessment (including providing teachers with an understanding of self‐assessment of their own mental health) is likely to increase teacher confidence in this area and is likely to have a positive impact on children. Spiker and Hammer (2019) highlight that ‘a lack of mental health knowledge is viewed as a driver of prejudice towards individuals with mental illness, which then leads to discriminatory behaviour’. The GPM highlights the important role of the teacher. Training in mental health literacy (MHL) can have a useful impact by providing the teacher with knowledge on mental health while also providing information on referral pathways and relevant resources. This is line with previous research, which found that training positively affected teachers' MHL and capacity to support these ‘at risk’ children (Mansfield et al., 2021; Ní Chorcora & Swords, 2021).

Bearing in mind the consequences of MHL, collaboration between psychologists who are working with teachers (e.g., through consultation or in‐service training) and parents may be particularly important. Furthermore, a lack of MHL may cause stigma among parents and/or teachers and may lead them to disengagement from the assessment process. However, this could be tackled by educational workshops delivered by psychologists.

External services need to improve how they communicate with schools to ensure that all stakeholders are kept informed and involved. Furthermore, external services would benefit from engaging with families on long wait lists as this may affect that likelihood that parents will access these services. Finally, as Mehrens (1998) states, it is ‘unwise, illogical and unscholarly to just assume that assessments will have positive consequences; there is the potential for both positive and negative consequences’ (p. 28). Therefore, further research should be conducted into teachers', principals' parents' and children's' perceptions of assessment of mental health in schools and the assessment resources used to support decision‐making.

CONCLUSION

This review's findings are relevant as they provide an overview of the studies completed in this area and the various perspectives held by teachers with respect to assessment of children's mental health in schools. This review gives teachers and policy makers food for thought, in particular in terms of the professional training that is been sought by teachers and the need to develop and/or improve existing policies which more clearly outline teachers' roles in the assessment of mental health in schools.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Pia O'Farrell: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; software; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Charlotte Wilson: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; supervision; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Gerry Shiel: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; supervision; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is part of a PhD in the School of Psychology at Trinity College Dublin, funded by School of Policy and Practice, DCU Institute of Education, Dublin City University. This funding has included the provision of research materials to support this research. I would also like to acknowledge the guidance and support of my supervisors Dr. Charlotte Wilson and Dr. Gerry Shiel and both my previous Heads of School, Dr. Brendan Walsh and Dr. Elaine McDonald, and my current Head of School, Dr. Martin Brown. Open access funding provided by IReL.

O’Farrell, P. , Wilson, C. , & Shiel, G. (2023). Teachers' perceptions of the barriers to assessment of mental health in schools with implications for educational policy: A systematic review. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 262–282. 10.1111/bjep.12553

This review was conducted across two universities (Dublin City University and Trinity College Dublin).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- Anderson, J. K. , Howarth, E. L. , Vainre, M. , Jones, P. B. , & Humphrey, A. (2017). A scoping literature review of service‐level barriers for access and engagement with mental health services for children and young people. Children and Youth Services Review, 77, 164–176. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, D. (2013). Educator perceptions of children who present with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties: A literature review with implications for recent educational policy in England and internationally. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 18(7), 731–745. 10.1080/13603116.2013.823245 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self‐efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour, R. , & Kitzinger, J. (Eds.). (1998). Developing focus group research: Politics, theory and practice. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, A. (2015). The handbook of child and adolescent clinical psychology: A contextual approach. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cefai, C. , Bartolo, P. A. , Cavioni, V. , & Downes, P. (2018). Strengthening social and emotional education as a core curricular area across the EU: A review of the international evidence. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Cefai, C. , Downes, P. , & Cavioni, V. (2016). Breaking the cycle: A phenomenological approach to broadening access to post‐secondary education. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 31(2), 255–274. 10.1007/s10212-015-0265 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cefai, C. , Simões, C. , & Caravita, S. (2021). ‘A systemic, whole‐school approach to mental health and wellbeing in schools in the EU’ NESET report. Publications Office of the European Union. 10.2766/50546 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Childs‐Fegredo, J. , Burn, A. M. , Duschinsky, R. , Humphrey, A. , Ford, T. , Jones, P. B. , & Howarth, E. (2021). Acceptability and feasibility of early identification of mental health difficulties in primary schools: A qualitative exploration of UK school staff and parents' perceptions. School Mental Health, 13(1), 143–159. 10.1007/s12310-020-09398-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E. , Calderon, E. , Salinas, G. , SenGupta, S. , & Reiter, M. (2012). Parents' perspectives on access to child and adolescent mental health services. Social Work in Mental Health, 10(4), 294–310. 10.1080/15332985.2012.672318 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conway, R. (2014). What is the value of award bearing professional development for teachers working with students with EBD? In Garner P., Kauffman J., & Elliott J. (Eds.), The sage handbook of emotional behavioural difficulties (pp. 427–438). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, B. G. , & Ruhaak, A. E. (2014). Causality and emotional or behavioral disorders: An introduction. In Garner P., Kauffman J., & Elliott J. (Eds.), The sage handbook of emotional behavioural difficulties (pp. 97–108). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran, T. , & Finney, D. (2015). Between education and psychology: School staff perspectives. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 20(1), 98–113. 10.1080/13632752.2014.947095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Danby, G. , & Hamilton, P. (2016). Addressing the ‘elephant in the room’. The role of the primary school practitioner in supporting children's mental well‐being. Pastoral Care in Education, 34(2), 90–103. 10.1080/02643944.2016.1167110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Debattista, M. , & Mangion, A. (2019). Teachers' awareness of social, emotional and behavioural difficulties in primary schools (Bachelor's thesis, University of Malta).

- Dowdy, E. , Ritchey, K. , & Kamphaus, R. W. (2010). School‐based screening: A population‐based approach to inform and monitor children's mental health needs. School Mental Health, 2, 166–176. 10.1007/s12310-010-9036-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorsky, M. R. , Girio‐Herrera, E. , & Owens, J. S. (2014). School‐based screening for mental health in early childhood. In Handbook of school mental health (pp. 297–310). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, S. B. , Nicholson, J. M. , & Battistutta, D. (2006). Parent and teacher identification of children at risk of developing internalizing or externalizing mental health problems: A comparison of screening methods. Prevention Science, 7(4), 343–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekornes, S. (2015). Teacher perspectives on their role and the challenges of inter‐professional collaboration in mental health promotion. School Mental Health, 7(3), 193–211. 10.1007/s12310-015-9147-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ford, T. , & Finning, K. (2020). Mental health in schools. In Mental health and illness of children and adolescents (pp. 1–15). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, T. , Hamilton, H. , Meltzer, H. , & Goodman, R. (2007). Child mental health is everybody's business: The prevalence of contact with public sector services by type of disorder among British school children in a three‐year period. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 12(1), 13–20. 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2006.00414.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, C. G. , Kim, J. S. , Ryan, T. N. , Kelly, M. S. , & Montgomery, K. L. (2012). Teacher involvement in school mental health interventions: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(5), 973–982. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.01.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, R. , Dubey, M. J. , Chatterjee, S. , & Dubey, S. (2020). Impact of COVID‐19 on children: Special focus on the psychosocial aspect. Minerva Pediatrica, 72(3), 226–235. 10.23736/s0026-4946.20.05887-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, A. (1997). Focus groups. Social research update. Issue Nineteen. University of Surrey. Available from: http://www.soc.surrey.ac.uk/sru/SRU19.html

- Goodman, R. L. , & Burton, D. M. (2010). The inclusion of students with BESD in mainstream schools: Teachers' experiences of and recommendations for creating a successful inclusive environment. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 15(3), 223–237. 10.1080/13632752.2010.497662 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gowers, S. , Thomas, S. , & Deeley, S. (2004). Can primary schools contribute effectively to tier I child mental health services? Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 9(3), 419–425. 10.1177/1359104504043924 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham, A. , Phelps, R. , Maddison, C. , & Fitzgerald, R. (2011). Supporting children's mental health in schools: Teacher views. Teachers and Teaching, 17(4), 479–496. 10.1080/13540602.2011.580525 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, L. , Theodosiou, L. , Bond, C. , Blackburn, C. , Spicer, F. , & Lever, R. (2010). Understanding the mental health needs of primary school children in an inner‐city local authority. Pastoral care in Education, 28(3), 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, S. , Morris, R. , Gunnell, D. , Ford, T. , Hollingworth, W. , Tilling, K. , Evans, R. , Bell, S. , Grey, J. , Brockman, R. , Campbell, R. , Araya, R. , Murphy, S. , & Kidger, J. (2019). Is teachers' mental health and wellbeing associated with students' mental health and wellbeing? Journal of Affective Disorders, 242, 180–187. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvest, H. (2018). How can EPs best support secondary school staff to work effectively with children and young people who experience social, emotional and mental health difficulties? (Doctoral dissertation, UCL (University College London)).

- Hinchliffe, K. J. , & Campbell, M. A. (2016). Tipping points: Teachers' reported reasons for referring primary school children for excessive anxiety. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 26(1), 84–99. 10.1017/jgc.2015.24 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, N. , & Wigelsworth, M. (2016). Making the case for universal school‐based mental health screening. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 21(1), 22–42. 10.1080/13632752.2015.1120051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iskra, W. , Deane, F. P. , Wahlin, T. , & Davis, E. L. (2015). Parental perceptions of barriers to mental health services for young people. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 12(2), 125–134. 10.1111/eip.12281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidger, J. , Gunnell, D. , Biddle, L. , Campbell, R. , & Donovan, J. (2009). Part and parcel of teaching? Secondary school staff's views on supporting student emotional health and well‐being. British Educational Research Journal, 36(6), 919–935. 10.1080/01411920903249308 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koller, J. R. , & Bertel, J. M. (2006). Responding to today's mental health needs of children, families and schools: Revisiting the preservice training and preparation of school‐based personnel. Education and Treatment of Children, 29(2), 197–217. [Google Scholar]

- Krendl, A. C. , & Pescosolido, B. A. (2020). Countries and cultural differences in the stigma of mental illness: The east–west divide. Journal of Cross‐Cultural Psychology, 51(2), 149–167. [Google Scholar]

- Landrum, T. J. , Wiley, A. L. , Tankersley, M. , & Kauffman, J. M. (2014). Is EBD 'special', and is 'special education' an appropriate response? In Garner P., Kauffman J. M., & Elliott J. G. (Eds.), The Sage handbook of emotional and behavioral difficulties (2nd ed., pp. 69–81). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, K. L. , Menzies, H. M. , Oakes, W. P. , & Kalberg, J. R. (2012). Systematic screenings of behavior to support instruction: From preschool to high school. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, J. M. , Saka, N. , Romanelli, L. H. , & Hoagwood, K. (2007). Early identification of mental health problems in schools: The status of instrumentation. Journal of School Psychology, 45, 163–191. 10.1016/j.jsp.2006.11.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loades, M. E. , & Mastroyannopoulou, K. (2010). Teachers' recognition of children's mental health problems. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 15(3), 150–156. 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2009.00551.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynagh, M. , Gilligan, C. , & Handley, T. (2010). Teaching about, and dealing with, sensitive issues in schools: How confident are pre‐service teachers? Asia‐Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 1(3–4), 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield, R. , Humphrey, N. , & Patalay, P. (2021). Educators' perceived mental health literacy and capacity to support students' mental health: Associations with school‐level characteristics and provision in England. Health Promotion International, 36(6), 1621–1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrens, W. A. (1998). Consequences of assessment: What is the evidence? Education Policy Analysis Archives, 6(13), 149–177. [Google Scholar]

- Meldrum, L. , Venn, D. , & Kutcher, S. (2009). Mental health in schools: How teachers have the power to make a difference. Health & Learning Magazine, 8(1), 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D. , Liberati, A. , Tetzlaff, J. , & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moilanen, K. , Shaw, D. S. , & Maxwell, K. L. (2010). Developmental cascades: Externalizing, internalizing and academic competence from middle childhood to early adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 637–655. 10.1017/S0954579410000337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooij, T. , & Smeets, E. (2009). Towards systemic support of pupils with emotional and Behavioural disorders. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 13(6), 597–616. [Google Scholar]

- Mundschenk, D. , & Simpson, R. (2014). Defining emotional or behavioral disorders: The quest for affirmation. In Garner P., Kauffman J., & Elliott J. (Eds.), The sage handbook of emotional behavioural difficulties (pp. 43–54). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ní Chorcora, E. , & Swords, L. (2021). Mental health literacy and help‐giving responses of Irish primary school teachers. Irish Educational Studies, 1–17. 10.1080/03323315.2021.1899029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O'Farrell, P. , & Kinsella, W. (2018). Research exploring parents', teachers' and educational psychologists' perceptions of consultation in a changing Irish context. Educational Psychology in Practice, 34, 315–328. [Google Scholar]

- Papandrea, K. , & Winefield, H. (2011). It's not just the squeaky wheels that need the oil: Examining teachers' views on the disparity between referral rates for students with internalizing versus externalizing problems. School Mental Health, 3(4), 222–235. 10.1007/s12310-011-9063-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reinke, W. M. , Stormont, M. , Herman, K. C. , Puri, R. , & Goel, N. (2011). Supporting children's mental health in schools: Teacher perceptions of needs, roles, and barriers. School Psychology Quarterly, 26(1), 1–13. 10.1037/a0022714 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothi, D. M. , Leavey, G. , & Best, R. (2008). On the front‐line: Teachers as active observers of pupils' mental health. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(5), 1217–1231. 10.1016/j.tate.2007.09.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sezer, S. S. S. (2017). Novice teachers' opinions on students' disruptive behaviours: A case study. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 17(69), 199–219. [Google Scholar]

- Shelemy, L. , Harvey, K. , & Waite, P. (2019). Secondary school teachers' experiences of supporting mental health. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 14(5), 372–383. 10.1108/JMHTEP-10-2018-0056 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shillingford, S. , & Karlin, N. (2014). Preservice teachers' self‐efficacy and knowledge of emotional and behavioural disorders. Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties, 19(2), 176–194. 10.1080/13632752.2013.840958 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soneson, E. , Howarth, E. , Ford, T. , Humphrey, A. , Jones, P. B. , Thompson Coon, J. , Rogers, M. , & Anderson, J. K. (2020). Feasibility of school‐based identification of children and adolescents experiencing, or at‐risk of developing, mental health difficulties: A systematic review. Prevention Science, 21, 581–603. 10.1007/s11121-020-01095-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiker, D. A. , & Hammer, J. H. (2019). Mental health literacy as theory: Current challenges and future directions. Journal of Mental Health, 28(3), 238–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- State, T. M. , Simonsen, B. , Hirn, R. G. , & Wills, H. (2019). Bridging the research‐to‐practice gap through effective professional development for teachers working with students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Behavioral Disorders, 44(2), 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Stiffman, A. R. , Pescosolido, B. , & Cabassa, L. J. (2004). Building a model to understand youth service access: The gateway provider model. Mental Health Services Research, 6(4), 189–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple University Libraries . (2022). Systematic reviews & other review types . Retrieved from https://guides.temple.edu/c.php?g=78618&p=3879604

- Tudge, J. R. H. , Mokrova, I. , Hatfield, B. E. , Van Dorn, R. A. , & Karnak, R. B. (2009). Uses and misuses of Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory of human development. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 1(4), 198–210. [Google Scholar]

- Tudge, J. R. H. , Payir, A. , Mercon‐Vargas, E. , Cao, H. , Liang, Y. , Li, J. , & O'Brien, L. (2016). Still misused after all these years? A reevaluation of the uses of Bronfenbrenner's bioecological theory of human development. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 8, 427–445. 10.1111/jftr.12165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walter, H. J. , Gouze, K. , & Lim, K. G. (2006). Teachers' beliefs about mental health needs in inner city elementary schools. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(1), 61–68. 10.1097/01.chi.0000187243.17824.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westling, D. (2010). Teachers and challenging behaviour: Knowledge, views and practices. Remedial and Special Education, 31(1), 48–63. 10.1177/0741932508327466 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J. H. , Horvath, V. E. , Wei, H. S. , Van Dorn, R. A. , & Jonson‐Reid, M. (2007). Teachers' perspectives of children's mental health service needs in urban elementary schools. Children & Schools, 29(2), 95–107. 10.1093/cs/29.2.95 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2019). The WHO special initiative for mental health (2019–2023): Universal health coverage for mental health (No. WHO/MSD/19.1). World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Yoder, N. (2014). Self‐assessing social and emotional instruction and competencies: A tool for teachers. Center on Great Teachers and Leaders. [Google Scholar]

- Youngminds . (2020). Coronavirus: Impact on young people with mental health needs. (Report 2.) https://youngminds.org.uk/media/3904/coronavirus‐report‐summer‐2020‐final.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.