Abstract

It is increasingly being recognized that active control of breathing - a key aspect of ancient Vedic meditative practices, can relieve stress and anxiety and improve cognition. However, the underlying mechanisms of respiratory modulation of neurophysiology are just beginning to be elucidated. Research shows that brainstem circuits involved in the motor control of respiration receive input from and can directly modulate activity in subcortical circuits, affecting emotion and arousal. Meanwhile, brain regions involved in the sensory aspects of respiration, such as the olfactory bulb, are like-wise linked with wide-spread brain oscillations; and perturbing olfactory bulb activity can significantly affect both mood and cognition. Thus, via both motor and sensory pathways, there are clear mechanisms by which brain activity is entrained to the respiratory cycle. Here, we review evidence gathered across multiple species demonstrating the links between respiration, entrainment of brain activity and functional relevance for affecting mood and cognition. We also discuss further linkages with cardiac rhythms, and the potential translational implications for biorhythm monitoring and regulation in neuropsychiatric disorders.

Keywords: Respiration, Brainstem, Olfactory bulb, Top-down control, Cardiac rhythm, Meditation

1. Introduction

In this review, we focus on recent research highlighting the potential links between breathing, brain activity, and cognition and mood. Recent work has suggested two mechanisms by which respiratory rhythms can affect the brain: (1) direct activation of subcortical brain regions via medullary brainstem circuits involved in motor respiratory control, and (2) oscillatory entrainment of brain circuits via olfactory bulb. We review relevant studies from both rodents and humans describing each of these links, in turn, to better address both the mechanistic as well as functionally relevant implications of these links. Finally, we highlight the interactions between cardiac rhythms and respiration-linked oscillatory activity across brain networks, and discuss a general model for how respiration and mood/cognition are associated via direct modulation of physiologic activity.

2. Clinical significance of respiratory control and modulation

A major motivation of this article is to review the possible biological mechanisms by which respiratory activity can affect mood and cognition. For this, it is important to review, at the outset, the body of clinical literature demonstrating the relationship between respiratory activity and neuropsychiatric symptoms (Brown et al., 2013; Jerath et al., 2015; Sakakibara and Hayano, 1996). Indeed there are many intriguing associations between respiratory problems and psychiatric symptoms. There is a high prevalence of anxiety disorders in patients with asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) (for example, (Kunik et al., 2005; Mikkelsen et al., 2004; Nascimento et al., 2002; Wagena et al., 2005). A large retrospective cohort study suggests that the respiratory problems precede anxiety; respiratory problems as early as the first year of life have a significant positive association with receiving treatment for an anxiety disorder as an adult (Goodwin and Buka, 2008). In adults, there is a moderate correlation between the degree of nasal obstruction in chronic rhinosinusitis and anxiety and depression scores (Campbell et al., 2017; Schlosser et al., 2016; Tomoum et al., 2015). In patients with both depression and chronic rhinosinusitis, treatment for the sinusitis alone (with either medications or surgery) improved depression symptoms in two-thirds of the patients treated (Schlosser et al., 2016). There are also specific associations between olfactory deficits and neuropsychiatric symptoms, including cognitive decline, that occur in early-stage neurologic disorders like Parkinson’s disorder (Bohnen et al., 2010; Cramer et al., 2010; Morley and Duda, 2011; Postuma and Gagnon, 2010).

Thus, multiple studies demonstrate a positive association for olfactory and respiratory dysfunction and neuropsychiatric dysfunction. These associations are likely multi-factorial – for example, having multiple episodes of being short of breath may contribute to anxiety, completely independent of any direct effect on respiratory function in the brain. However, it is noteworthy that many studies show associations between controlled respiratory activity and improved mental health and well-being. For example, undergraduate students trained in pranayama showed a change in both subjective and objective measures of stress responsivity (Bhimani et al., 2011), and displayed lower test anxiety (Nemati, 2013) compared to a control group. Several studies have found that yoga practices that include pranayama likewise can improve anxiety/depression symptoms (Brown and Gerbarg, 2005; Kozasa et al., 2018; Mobini Bidgoli et al., 2016; Seppälä et al., 2014). Non-pranayama based relaxation breathing practices have also been shown to diminish anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms across diverse populations (Bryant et al., 2005; Clark et al., 1985; Nardi et al., 2009; Tweeddale et al., 1994). It is important to note that while pranayama-based and non-pranayama based respiratory training both focus on slow, controlled diaphragmatic breathing, non-pranayama based breathing practices may not put as much emphasis on nasal breathing. As we shall review below, nasal breathing specifically may be quite important in terms of overall mechanisms by which respiratory activity can affect limbic and cortical brain circuits. Finally, it is important to note that most of these intervention studies are not of the highest quality (not well-controlled) nor with large enough sample sizes to unequivocally demonstrate meaningful clinical effects. Nonetheless, they are interesting and generally consistent in suggesting that changes in patterns of the respiratory rhythm (independent of other aspects of mindfulness, meditation or exercise), itself may play a key role in both the development and/or treatment of mood and anxiety disorders.

3. Breath control in meditative practices

Breath control is an important part of meditative traditions. In pranayama, one of most commonly practiced breath control techniques, there is often a focus on slowing the breath, maintaining standardized pauses during and between inspiration and expiration cycles and using nostril breathing. The Hatha Yoga Pradipika text, described it thus: “When the breath is irregular, the mind wavers; when the breath is steady, so is the mind. To attain steadiness, the yogi should restrain his breath” (Iyengar, 1985). Buddhist meditation practices (Anapama) have been focused more on developing mindful attention to the breath (Tang et al., 2015a, b; Tang and Posner, 2014). However, even these attention-based meditative practices have been shown to modify the respiratory rate and cycle (Jerath et al., 2015; Melnychuk et al., 2018; Sharma, 2015; Vyas and Dikshit, 2002; Wielgosz et al., 2016). Suzuki Roshi, a practitioner of Zen Buddhist, describes this process: “…at that time [after 5 or 10 min of not stopping or being bothered by mind, after which mind calms] your breathing will become quite slow, while your pulse will become a little faster…” (Suzuki, 2011). Thus, most forms of meditative practice affect respiration, and these traditions believe that respiratory attention and control are important for mental and emotional stability.

4. Top-down control of respiratory activity

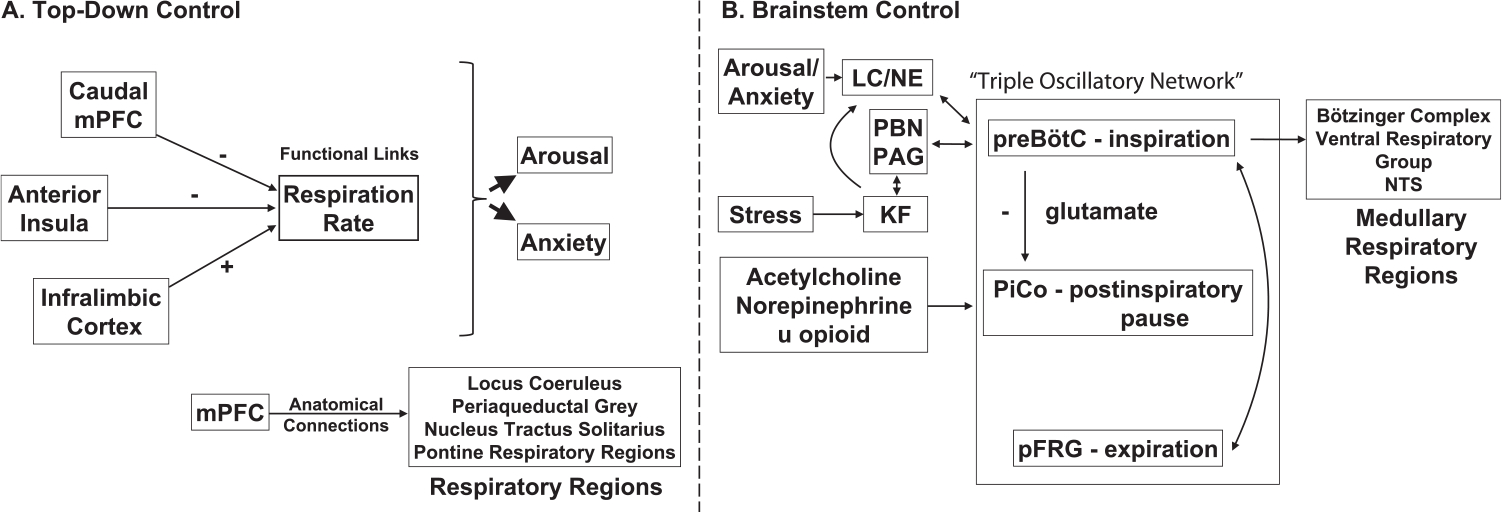

Rapid, volitional control is what distinguishes respiration from most other autonomic processes – we don’t have easy direct control over heart rate, digestive processes, salivation, etc. The ability to volitionally regulate respiration, which in turn can modulate arousal and anxiety, is an essential part of how we can develop breath training practices as a calming/grounding tool in the first place (Craigmyle, 2013). There are several pieces of evidence supporting the importance of prefrontal cortex in controlling respiratory activity. Electrical stimulation of infralimbic cortex (i.e. rodent ventromedial prefrontal cortex (PFC) important for limbic emotional response regulation) increases respiratory flow, even in anesthetized rats, while stimulation of anterior insula decreases respiratory flow (Aleksandrov et al., 2007). Similarly, when bicuculline (a GABA receptor antagonist, resulting in increased excitability of a region) is injected into caudal medial prefrontal cortex of rats, respiratory rate decreases; while when this is injected into infralimbic cortex, respiratory rate increases (Hassan et al., 2013), consistent with the antagonistic effects of these brain regions on impulsivity and behavioral regulation (Bi et al., 2013).

It is unclear from these studies exactly how PFC modulates respiratory rate. However, the medial PFC (mPFC) has extensive anatomical connections to many regions that influence respiratory activity, including the locus coeruleus (LC) (Jodo et al., 1998), the periaqueductal grey (PAG) (Gabbott et al., 2005), the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) (Terreberry and Neafsey, 1987), and pontine respiratory regions (Dutschmann and Dick, 2012). Additionally, such effects may be mediated via projection from mPFC to limbic regions, as amygdala stimulation has also been shown to obstruct respiration (Nobis et al., 2018). Recently, Liu et al. (2020) discovered a potential circuit for non-homeostatic regulation of breathing, involving direct regulation of breathing rhythm by conveying signals from limbic/brainstem areas to medullary rhythm generating neurons. Specifically, the authors identified a cluster of genes involved in coding of the u-opioid receptor in the lateral subdivision of the parabrachial nucleus, which directly regulated breathing rate by sending signals to the preBötzinger complex. Inactivation of these neurons led to decreased breathing rates, as well as, decreased anxiety-like behaviors and strong appetite behaviors. Overall, even though it is obvious that we have volitional control over respiratory activity, and this volitional control likely involves prefrontal cortex (Fig. 1A), the exact circuits that mediate this process remain to be fully understood.

Fig. 1.

Evidence for functional/ anatomical neural connections supporting (A) top-down and (B) bottom-up control of respiration. In (A), various cortical regions are shown that modulate respiration, and are also involved in arousal and anxiety. In (B), the triple oscillatory network that controls respiratory timing is illustrated centrally, with anatomical and functional inputs and outputs to other key respiration-linked regions highlighted, as well. The preBötC and KF nucleus also project to the thalamus and posterior/lateral hypothalamus, not shown here. Together, these respiratory networks influence mood and cognition. Abbreviations: mPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; LC/NE, locus coeruleus norepinephrine system; PAG, periaqueductal gray; PBN, parabrachial nuclei; KF, Kölliker–Fuse nucleus; preBötC, preBötzinger Complex; NTS, nucleus tractus solitarius.

5. Brainstem control of respiration

An exhaustive review of brainstem driven regulation of respiration is beyond the scope of this review and has been comprehensively described elsewhere (Alheid et al., 2004; Dutschmann and Dick, 2012; Feldman, 1986; Negro et al., 2018). The primary focus here is to summarize the brainstem respiratory centers that are involved in respiratory rhythm generation, and projections from these medullary circuits to limbic/neuromodulatory circuits involved in stress, anxiety and arousal. There are three identified medullary brainstem centers involved in controlling the involuntary rhythmic cycle of respiration (Anderson and Ramirez, 2017): the preBötzinger complex (preBötC), the post-inspiratory complex (PiCo) and the parafacial respiratory group (pFRG). These three nuclei are thought to operate as coupled oscillators (Thoby-Brisson et al., 2009) to control the timing of inspiration (preBötC), post-inspiration pause (PiCo), and expiration (pFRG) (Fig. 1B). However, it is worth noting that these results have not been replicated since, and may indicate the PiCo can help modulate, but is not necessary to generate post-inspiration. Recently, Toor et al. (2019) showed that pharmacological inhibition of the PiCo, does not change the three-phase respiratory generation. While the results from Anderson and Ramirez (2017) should not be completely discredited, they perhaps indicate the PiCo in a larger network of post-inspiratory control, not as a single player. This is supported by more recent work (Dhingra et al., 2019), suggesting a distributed circuit involving the preBötC/BötC, NTS and Kölliker–Fuse (KF) nucleus, to generate post-inspiratory motor activities. Of particular importance in this network, and brainstem sensory-motor networks and forebrain rhythms, might be the KF nucleus due to its ability to regulate the gain of sensory feedback via projections to the NTS (Dhingra et al., 2017). It is noteworthy that yogic texts likewise describe three parts of the respiratory cycle: inhalation (Puraka), exhalation (Rechaka) and the pause in-between (Kumbhaka) (Iyengar, 1985). Various practices in pranayama are oriented around varying the timing of each of these parts of the respiratory cycle, which we can now link back to likely modulating activity in each of these medullary respiratory centers.

The preBötC appears to be both necessary and sufficient for controlling the timing of inspiration (Ikeda et al., 2017). The preBötC contains no distinct nucleus (Ikeda et al., 2017), but rather consists of an arrangement of glutamatergic excitatory (Koshiya et al., 2014; Koshiya and Smith, 1999) and GABAergic and glycinergic inhibitory interneurons (Kuwana et al., 2006). The glutamatergic neurons are directly involved in the timing of inspirations; silencing these neurons results in persistent and life-threatening apnea (Gray et al., 2001; McKay et al., 2005; Tan et al., 2008). The inhibitory glycinergic inhibitory neurons do the exact opposite: terminating inspiration and delaying the onset of the next inspiration (Sherman et al., 2015). The preBötC controls inspiration via direct afferent projections of the preBötC to other medullary regions involved in respiratory control, including the BötC, the ventral respiratory group, the PiCo, parafacial respiratory group/retrotrapezoid nucleus (pFRG/RTN), and other respiratory control regions including the parabrachial nuclei (PBN), PAG, and NTS (Tan et al., 2010; Yang and Feldman, 2018). This direct anatomic connectivity to the major medullary motor nuclei controlling respiration suggests that the preBötC acts to coordinate the timing of these disparate regions in the context of the overall respiratory cycle. The preBötC also receives input from glutamatergic neurons of these other respiratory regions, including PAG and the PBN (Oka et al., 2012), thus providing feedback required for “coupled oscillators”.

The next phase of the respiratory cycle following inspiration is a “post-inspiratory” period prior to expiration. As discussed earlier, this period between active inspiration and expiration is termed Kumbhaka in yogic terms, and intense effort is made in yogic practice to prolong/extend this phase of the respiratory cycle. Under normal conditions, there are a number of other processes that need to be coordinated with respiration (vocalization, swallowing, coughing, etc.) that tend to occur during this post-inspiration phase (Anderson et al., 2016). The cluster of neurons that manages this phase is the PiCo (Anderson et al., 2016). Neurons in the PiCo are sensitive to modulation by acetylcholine, norepinephrine, and opioids (Anderson et al., 2016). Activity in these neurons is strongly suppressed by glutamatergic activity of the preBötC, and thus the post-inspiratory burst may be driven by a release of inhibition on this system.

Timing of the expiratory phase of the respiratory cycle seems to be primarily controlled by the pFRG/RTN areas (Pisanski and Pagliardini, 2018). There are also peptidergic neurons that project from this region to preBötC that control sighing (Li et al., 2016). Given that sighing is also connected to emotional state, these neurons may play a key role in this relationship. Thus, it now appears that these three nuclei, preBötC, PiCo and pFRG/RTN together result in a triple oscillatory network that controls respiratory timing (Anderson and Ramirez, 2017; Wittmeier et al., 2008) and changing the duration of the three parts of the respiratory cycle, as occurs during pranayama, can thus vary activity in these brainstem nuclei.

In addition to these medullary respiratory centers, the pons also has an area - the PBN and adjacent KF nucleus, involved in respiratory control (Chamberlin, 2004; Dick et al., 1994; Dutschmann and Dick, 2012; Palmiter, 2018; Sanders et al., 2012; Song et al., 2012) Neurons in the KF nucleus are clearly sensitive to orexin, an arousal-related neuropeptide (Dutschmann et al., 2007), and thus play an important role in linking arousal with respiration (Kaur et al., 2013; Lavezzi et al., 2016). There is evidence that neurons in this region have respiratory locked activity (Dick et al., 1994), and have diverse projections (Chamberlin, 2004; Song et al., 2012). As mentioned earlier, the KF nucleus may play a particularly important role in post-inspiratory control due to its ability to regulate the gain of sensory feedback via projections to the NTS (Dhingra et al., 2017).

6. Link between brainstem respiratory centers, arousal and anxiety

Across species, respiratory rate increases with arousal, anxiety and stress (Carnevali et al., 2013; Masaoka et al., 2003; Masaoka and Homma, 1997; Wilhelm et al., 2001). Certainly, it makes evolutionary sense that, when an animal is anxious or aroused (i.e., in flight/fight mode), the need for increased oxygenation would drive increased respiration. Indeed, norepinephrine has been shown to directly modulate the respiratory rate (Viemari and Ramirez, 2006) by promoting synchronization of brainstem respiratory circuits discussed above. Stress paradigms likewise activate the pontine respiratory group (and, specifically, the KF nucleus), suggesting a direct coupling for how stress increases respiratory drive (Furlong et al., 2014).

It was recently discovered that the opposite is also true – brainstem respiratory centers directly affect activity in the LC noradrenergic system (LC/NE) with functional consequences (Yackle et al., 2017). The LC is a brainstem nucleus that provides the primary source of noradrenaline (NE) to the cortex, hippocampus, hypothalamus and amygdala (Khroud and Saadabadi, 2018; Sara, 2009). The LC/NE system has been implicated in arousal (Sara and Bouret, 2012) and attention (Corbetta et al., 2008; Sara and Bouret, 2012; Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005). Neurons in the LC fire tonically at a 1–3 Hz rhythm to modulate global arousal states (Gary Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005; Howells et al., 2012). Changes in this tonic/background firing occur during transitions of sleep/wake states and other large shifts in arousal (Aston-Jones and Bloom, 1981; Rajkowski et al., 1994) and alterations in tonic firing patterns may explain abnormalities in arousal and anxiety in neuropsychiatric disorders (Howells et al., 2012). The LC also fires in phasic bursts of alpha rhythms (8–10 Hz) during salient stimuli to prolong arousal states and modulate attention (Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005; Minzenberg et al., 2008; Sara, 2009).

Recently, Yackle et al. (2017) found a cluster of preBötC neurons in the brainstem, which can drive intrinsic rhythms in the LC. Glutamatergic neurons in the preBötC are classically defined as either NK1R or SST stain positive. Using a genetic screen, Yackle et al. found a new population of glutamatergic neurons that stain CDH9+/Dbx1+. Removal of these neurons resulted in a shift towards slower breaths (lower respiratory rate) and overall more calm behaviors. There was also a reduction in sniffing and exploration, and an increase in the amount of time spent grooming and sitting still. Yackle et al. (2017) also showed that CDH9+/Dbx1+ neurons project directly to noradrenergic neurons in the LC. As discussed before, pre-BötC neurons are linked with and provide timing to the inspiratory phase of respiration (Cui et al., 2016). Thus, if there is a link between respiratory rate and LC activation, one would expect that there would be a direct relationship between the inspiratory phase of respiration and LC activity. Research in humans suggests this is the case. Pupil diameter, a commonly accepted index of LC activity (Murphy et al., 2014; Reimer et al., 2016), rises in phase with the pre-inspiratory/inspiratory phase of respiration, and falls during the expiratory phase of respiration, consistent with a direct role in activation of LC from pre-inspiratory/inspiratory preBötC neurons (Melnychuk et al., 2018).This cross-species evidence strongly suggests that the cells observed in rodents may also be present in humans and drive LC in a similar way.

In addition to projections to LC, both PreBötC neurons and pontine KF neurons project to other suprapontine brain regions including the PAG, mediodorsal and centro-median thalamus, and posterior/lateral hypothalamic areas (Yang and Feldman, 2018; Dutschmann and Dick, 2012). There is an absence of direct ascending projections from PreBötC neurons to limbic areas. However, other PBN neurons have been shown to project to limbic and cortical areas (Dutschmann and Dick, 2012), and ascending glutamatergic arousal pathways to the forebrain from the PBN (including NTS) likely play a key role in arousal and maintaining a wakeful state (Fuller et al., 2011). These conclusions are consistent with previous anatomic and functional studies (Krukoff et al., 1992; Krukoff et al., 1993) and previous knowledge of NTS projections to brainstem and forebrain targets (Ter Horst and Streefland, 1994), Interestingly, both excitatory and inhibitory neurons from PreBötC send long-range projections to PAG, thalamic and hypothalamic regions suggesting bi-directional control of these down-stream brain regions (i.e., both activation and inhibition) (Yang and Feldman, 2018). All of these projections have implications for the impact of respiratory rate on mood and cognition. PAG is known for coordinating respiratory (and other motor) outputs based on input from limbic, prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (Furlong et al., 2014; Graeff, 2004; Prestipino et al., 2017; Subramanian and Holstege, 2010). Other regions that are connected to PreBötC include centro-median and mediodorsal thalamus, which are key thalamic circuits for modulating frontal circuits associated with higher-level cognition (Parnaudeau et al., 2018; Vertes, 2006). Finally, lateral and dorsomedial hypothalamus, and lateral preoptic area (LPO) are linked with a number of low-level circadian/stress/aggression/feeding circuits (Bonnavion et al., 2016; Nieh et al., 2016; Piñol et al., 2018; Prestipino et al., 2017). Thus, these pontine and medullary projections connect respiratory rhythms to key regions involved in modulating stress, mood and cognition.

We have reviewed, above, how activity in the PreBötC and KF nucleus may play a coordinating role in modulating activity in the LC, hypothalamus and thalamus, providing direct, inspiration-locked activation/ inhibition of these brain circuits. After inspiration is terminated, the PiCo seems to play a role in activating the vagal nerve during the pause between inspiration/ expiration (Anderson et al., 2016). Thus, it is possible that prolongation of this pause period between inspiration and expiration provides increased activation to the vagal nerve. This natural method of activating LC during inspiration and activating vagal tone after inspiration ends, may provide a way of maintaining balance between anxious versus relaxed states; furthermore, this may also be a dual mechanism by which slowing the respiratory rate can help restore balance between parasympathetic/sympathetic activity.

7. Large scale respiratory entrainment of neural oscillations

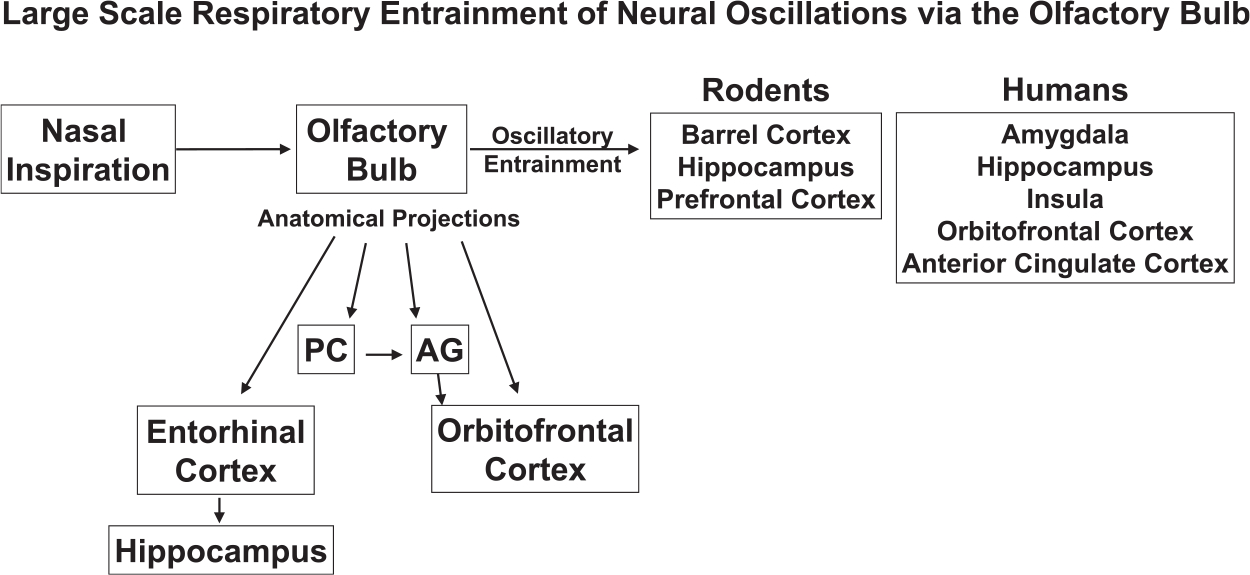

Above, we have been reviewing how circuits involved in respiratory motor control project to subcortical brain circuits involved in emotion and cognition, and how these circuits might explain how respiratory control can modulate and synchronize brain activity. In addition, there is a wealth of evidence linking sensory activity transmitted via olfactory neurons and the olfactory bulb in respiratory rhythm entrainment. Lord Adrian, was one of the first individuals to record gamma oscillations in the olfactory bulb of hedgehogs (Adrian, 1942, 1950). This work was later built upon by Freeman and colleagues (Freeman, 1975; González-Estrada and Freeman, 1980). The primary role of the olfactory bulb (OB) is to process and transmit olfactory information into the brain. Because olfaction tends to be time-locked with respiratory activity (nasal breathing coincides with olfactory sampling), it has long been known that electrical activity in the OB is synchronized with the breathing rhythm in rodents (Adrian, 1950; Macrides and Chorover, 1972; Onoda and Mori, 1980; Ravel and Pager, 1990). Indeed, it is now common to use neural oscillations in the OB as a proxy for respiratory activity (Jessberger et al., 2016; Rojas-Líbano et al., 2018). Prior studies have observed respiratory entrainment of neural activity in the rodent piriform (i.e., olfactory) cortex (Kepecs et al., 2007) and in barrel (i.e., somatosensory) cortex during whisking (Cao et al., 2012; Ito et al., 2014) Entrainment of barrel cortex seems to occur via direct activation of facial motor nuclei by preBötC neurons, such that whisking is time-locked to inspiratory activity (Moore et al., 2013). Interestingly, it was subsequently shown that the olfactory bulb plays a key role in the transmission of the respiratory rhythm to barrel cortex, providing an alternate, non-motor pathway by which this activity can be entrained. Specifically, removal of the OB eliminates respiratory-entrained low-frequency oscillations in barrel cortex (Ito et al., 2014).

It is perhaps understandable that respiration helps to synchronize whisker sensations and olfaction, as both of these processes are directly related to respiration. However, it was quite surprising that the respiratory rhythm also entrains neural oscillations in many other brain regions, including the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. In early studies, conducted under urethane anesthesia, (Chi et al., 2016; Lockmann et al., 2016; Yanovsky et al., 2014), researchers were able to show that respiration-entrained oscillations in hippocampus were clearly separable from endogenous hippocampal theta oscillations, which phase-reverse across layers. A tracheotomy, abolishing nasal breathing, abolished these respiratory-coupled low-frequency oscillations while preserving endogenous theta activity; furthermore, this rhythm was restored via delivery of “air-puffs” into the nostril (Lockmann et al., 2016). Follow-up studies, conducted during awake states, have shown respiratory coupled oscillations between OB and hippocampus at both lower (delta, < 4 Hz) and higher (beta, 15–30 Hz) frequencies (Lockmann et al., 2018), respiratory coupled delta/gamma oscillations in PFC (Biskamp et al., 2017), and respiratory-locked oscillations across many other brain regions (Rojas-Líbano et al., 2018; Tort et al., 2018; Zhong et al., 2017). Interestingly, the degree of respiratory entrainment in cortex and hippocampus is not stable, but rather changes with varying behavioral states, such as exploration, awake immobilization and sleep, (Zhong et al., 2017), suggesting a dynamic & complex process mediating respiratory rhythm entrainment. Hippocampal sharp-wave ripples, which are implicated in memory consolidation and recall, have also been shown to be phase-locked with respiration (Liu et al., 2017). Similar to other experiments, this respiratory influence on hippocampal neuronal activity was eliminated when olfactory bulb activity was inhibited.

This body of work demonstrates the importance of the respiratory rhythm, and, particularly, OB-coupled oscillations, to brain-wide entrainment at both lower and higher frequencies in a number of brain regions relevant to cognition and mood (Fig. 2). The ability of the OB to entrain oscillatory activity is likely mediated through activity of olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs). OSNs have been shown to generate rhythmic signals after being activated in response to mechano-stimulation (Connelly et al., 2015; Grosmaitre et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2017), which could then synchronize respiratory rate and neural oscillations in the OB/Piriform Cortex (Buonviso et al., 2006; Fontanini and Bower, 2005; Fontanini et al., 2003), and in theory, other downstream brain regions as well. If OSNs are compromised or airflow is diverted from the nose, much of this synchrony disappears, yet some intrinsic rhythmic oscillation remains, which we posit likely emerges from preBötC and other medullary brainstem regions involved in respiratory control, as discussed previously. Returning the nasal airflow through mechanically induced puffs of air can regenerate and resynchronize this partial loss of the respiratory rhythm (Fontanini et al., 2003; Ito et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2017).

Fig. 2.

Large scale entrainment of neural oscillations in cortical and limbic regions of rodents and humans, via the olfactory bulb. Also shown are specific, relevant, anatomical projections of the olfactory bulb to cortical and limbic regions. Abbreviations: PC, piriform cortex, AG, amygdala.

There has long been, in Pranayama, an emphasis on “nostril” breathing. The evidence described here suggests that nostril breathing, in humans, can activate OSN mechanoreceptors, and thus drive OB-related entrainment of neural activity in a way that is fundamentally different than what might occur with mouth-breathing. This is important as much of the “relaxation breathing” practices are based on deep diaphragmatic breathing, with less emphasis on nasal breathing specifically. Secondarily, changing the respiratory rate, according to this model and as also empirically shown in rodents, can directly change the respiratory neural rhythm (from delta to high-theta range activity or vice-versa), and thus, provide a direct way of “modulating” wide-spread brain oscillations. Thus, to the degree that certain oscillations at rest may be associated with more relaxed vs. more anxious states, changing OB-mediated respiratory rhythms would provide a separate means of affecting these states quite independent from that discussed above (preBötC - > LC).

We have identified above both motor and sensory pathways by which respiration can cause changes in neuromodulatory systems associated with arousal, and large-scale synchronization of brain activity to the respiratory rate. Importantly, particularly in terms of the relationship between OB and large-scale neural entrainment to the respiratory rate, it is important to recognize that rodents are strongly reliant on odor as a means of gathering sensory information. Thus, such findings may be far less relevant for humans, and the anatomical and functional connectivity differences across species may limit the relevance of findings in rodents, described above. In part to address this issue, there have been several recent studies using intracranial recordings in humans to investigate respiratory entrainment. One study (Zelano et al., 2016) observed low-frequency coherence between oscillations in piriform cortex and the respiratory rhythm (< 0.6 Hz). Importantly, no such low-frequency coherence was observed in neighboring regions, i.e., in the amygdala/ hippocampus, however, higher-frequency entrainment to the respiratory rhythm was observed in both of these regions. Specifically, human subjects showed inspiratory-locked increases in delta/theta and beta oscillations in amygdala and hippocampus. Thus, in humans, this evidence suggests that brain regions that are part of the olfactory system are directly entrained to the respiratory rhythm, while secondary limbic regions show some degree of phase-amplitude coupling of high-frequency oscillations to these very low-frequency oscillations (this mechanism is elaborated further in the next section). Importantly, these inspiratory-locked changes in power were dependent on nasal respirations, and diminished in the context of mouth breathing, consistent with results from rodents that the OB-system was important for driving these phase-locked neural dynamics.

Another study (Herrero et al., 2018) also using intracranial electrodes in humans, investigated high-gamma activity (in part because high-gamma activity is less susceptible to volume conduction and other spatial filtering, which complicates the interpretation of extracellular recordings). They found that high-gamma power correlated with the respiratory rate, with increased activity locked to the inspiratory phase of the cycle, in multiple brain regions. More interestingly, volitional breathing specifically increased this respiratory coupling in multiple cognitive regions including the hippocampus, amygdala, insula, orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and lateral prefrontal cortex. Finally, to causally demonstrate these relationships, experiments were done in which OSN were directly activated using air-puffs while monitoring the effects on brain activity (Piarulli et al., 2018). Air-puff stimulation produced enhanced delta/theta activity (as measured using extracranial electroencephalography (EEG) electrodes), again providing evidence that a large part of the neural entrainment is sensory-mediated.

There are a number of anatomic pathways by which this sensory-mediated neural entrainment may occur in humans. Piriform cortex and amygdala receive direct afferent inputs from the olfactory bulb (Carmichael et al., 1994; Root et al., 2014) and the hippocampus receives projections from the olfactory system via the entorhinal cortex (Carmichael et al., 1994; Haberly and Price, 1978). The OFC also receives direct olfactory projections as well as inputs from the piriform cortex via the amygdala (Soudry et al., 2011), and, thus, may also play a role in linking breathing and cognition. Furthermore, these areas also transmit “top-down” reciprocal axons (Krusemark et al., 2013), again implicating both “bottom-up” and “top-down” interactions between breathing and cognitive circuitry (Kohli et al., 2016).

In the Herrero et al. (2018) study discussed above, attention to the breath increased respiratory rate coherence in ACC and insula, classic cognitive control brain regions. There are direct anatomical olfactory projections to the ACC and insula (Heimer et al., 2007). The insula is particularly important to interoceptive awareness of breath regulation and breath timing, as it has been shown to be a component of time-representation in the body (Livesey et al., 2007) and time synchronization (Bushara et al., 2001). This may be one reason why studies on meditation have shown increased activity, connectivity or plasticity in these brain regions (Brewer et al., 2011; Lazar et al., 2005; Luders et al., 2012; Lutz et al., 2008; Nakata et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2015a, b). In our own work, we have also demonstrated that attention-to-breath training modulates ACC-insula functional connectivity and can enhance neuro-cognitive outcomes, such as improved sustained attention to environmental stimuli and improved distractor suppression (Mishra et al., 2017).

Future investigations need to co-monitor respiratory and neural oscillations as potential biomarkers for neuropsychiatric disorders, and especially in disorders showing deficits in attention such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. We also suggest that future studies devote particular emphasis on investigating the species-specific versus species-general mechanisms observed across various studies (Nguyen Chi et al., 2016; Yanovsky et al., 2014).

8. Functional significance of respiratory entrainment for mood & cognition

In the context of respiratory-neural regulation, theta band (4–8 Hz) oscillations and gamma (30–80 Hz) oscillations that are phase-coupled to theta have been proposed as a mechanism for global entrainment of cortical activity (Heck et al., 2017; Kahana, 2006). Heck et al. (2017) recently put forth a computational model demonstrating that modulation of gamma oscillatory amplitude by the breathing cycle is achievable via intrinsic properties of cortical networks, assuming that respiration drives neuronal excitability. Indeed, there is a huge body of work suggesting ways in which phase-amplitude coupling of low and high-frequency oscillations can contribute to various forms of optimal network functioning and cognition (Canolty and Knight, 2010; Cohen and Frank, 2009; Voytek et al., 2010; Zhong et al., 2017). This suggests that respiratory entrainment of neural activity should have important impacts on mood and cognition.

It is likely not unrelated that removal of the olfactory bulb in rodents has long been used as a model for depression (Song and Leonard, 2005). It is clear that the depressive phenotype is unrelated to the anosmia deficits (Song and Leonard, 2005); instead, animal studies show that depression is related to anterograde and retrograde degeneration of circuits that project to and away from the OB, with changes in neural signals in cortex and hippocampus (Wrynn et al., 2000), reduced dendritic spines in hippocampus (Norrholm and Ouimet, 2001), loss of neurons in dorsal raphe and LC (Grecksch et al., 1997; Nesterova et al., 1997) and changes in amygdala functioning (Shibata and Watanabe, 1994). How olfactory bulbectomy causes all of these changes has not been clearly elucidated. However, it is at least possible that some of these changes that result from an olfactory bulbectomy are related to functional changes that result from a loss of the global respiratory rhythm. Additionally, in humans, decreased olfactory bulb volume has been linked with major depressive disorder as well as associated with childhood maltreatment (Croy et al., 2013; Negoias et al., 2010). Moreover, lesions of the OB are linked with decreased cognitive performance in humans (Kohli et al., 2016).

Beyond co-synchronization of respiration and population neural activity (measured using EEG and local field potential (LFP) recordings), the timing of inspiration/expiration has also been recently shown to affect cognitive behaviors including both olfactory and non-olfactory cognitive processes (Arshamian et al., 2018; Perl et al., 2019; Zelano et al., 2016) In fact, in rodents there is evidence suggesting that cell types within the olfactory bulb may be specifically differentiated for inspiration and expiration (Phillips et al., 2012), providing a potential anatomical basis for the functional differences of inspiratory and expiratory influences on cognition. In humans, Zelano et al. found greater object recall accuracy when objects were encoded or recalled during inspiration as opposed to expiration, with the most accurate encoding & recall epochs occurring during nasal inspiration, as opposed to oral inspiration. These authors had similar findings for increased emotional discrimination accuracy during inspiration versus expiration. This double distinction (inspiration > expiration; nasal > oral), suggests that both mechanisms discussed above (brainstem mediated and OB mediated synchronization of neural activity; Figs. 1B and 2) may have functional roles to play in modulating cognition. Similar improvements for cognition during nasal as opposed to oral respiration were found on an olfactory memory task (Arshamian et al., 2018). In a subsequent study with EEG collected during three tasks (visuospatial, lexical and match task), Perl et al. (2019) found that, when given the option, human subjects spontaneously self-initiate trials synchronized with inspirations rather than expirations. They further found improved performance on the visuospatial task when time-locked to inspiratory rather than expiratory activity, though there was no difference in performance on the lexical task. Interestingly, and at least partially consistent with Zelano et al. (2016), Perl et al. found a benefit for inspiratory-locked behavior when subjects used both nasal and oral respirations, with no clear difference between the two. Underlying these behavioral effects, the authors found inspiratory-locked reductions in alpha/beta power in right postcentral gyrus and precuneus, the latter region known for its role in visuospatial processing. Further follow-up research from Waselius et al. (2019) shows that brain state may be optimized for learning during diastole (of the cardiac cycle) during expiration; participants demonstrated more learned responses if trained during expiration vs inspiration or a random phase of breathing. These results, while not exactly consistent with Zelano et al. (2016), are consistent with the idea that the phase of respiration may be an important modulator of cognitive processes.

9. Association with cardiac rhythms

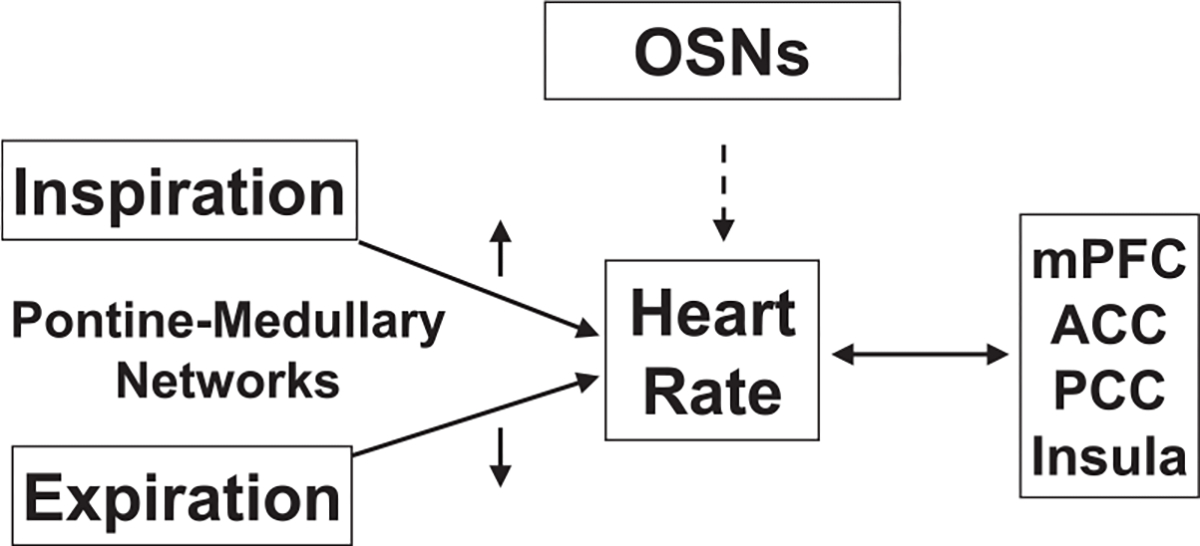

Rhythms are an innate aspect of life; here we briefly discuss evidence for functional interconnections between the respiratory rhythms discussed above, the cardiac rhythm and brain regions important for cognitive control (Fig. 3). Heart rate has been shown to affect cognitive processes (attention, learning and memory, decision making) with the insula proposed as a critical structure in this process, due to its role in interoceptive awareness of bodily states (Critchley and Garfinkel, 2018; Salomon et al., 2016). In a recent systematic review, Forte et al. (2019) found evidence across various studies in healthy adults that higher heart-rate variability (HRV) was associated with greater neural activity of the prefrontal cortex, and in turn finer cognitive performance on executive function tasks, even after adjustment for confounding variables commonly associated with HRV (i.e., age, gender, years of education, body mass index, blood pressure, cardiovascular diseases). Overall, these studies support the Neurovisceral Integration Model (Thayer et al., 2009), which hypothesized cortical integration between the executive, autonomic, and emotional processing systems.

Fig. 3.

Evidence suggests cardio-respiratory coupling and interactions of the cardiac rhythm with cortical cognitive systems. The phase of respiration can alter heart rate. OSNs are also linked to heart rate modulation, albeit with exact mechanisms not known. In turn, heart rate related blood flow changes can affect important cognitive brain regions, especially mPFC, ACC, PCC, Insula. Functional connectivity of these regions is also affected by meditation practices and volitional breath control; the latter also affects heart rate frequency, thus linking these cardio-respiratory-cortical systems in a loop with direct neural signal communication mediated via the vagus nerve. Abbreviations: OSNs, Olfactory Sensory Neurons; mPFC, medial prefrontal cortex, ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; PCC, posterior cingulate cortex.

Heart rate is also closely tied to the respiratory system; during inspiration heart rate increases, and during expiration it tends to decrease (Yasuma and Hayano, 2004); there is much research exploring cardiorespiratory coupling (CRC) (Bartsch et al., 2014; Sobiech et al., 2017; reviewed in Dick et al., 2014). Pokrovskii et al. (2003) hypothesized CRC may occur due to coupling of two neuronal centers in the medulla oblongata, with recent research supporting this hypothesis (Perry et al., 2019). Specifically, the pons has been implicated as a key player in the mechanism of CRC (Dick et al., 2014), further demonstrating the importance of aforementioned pontine-medullary networks.

The vagus nerve serves as a key gateway for innervation of the parasympathetic nervous system and the brain. The vagus nerve provides the pathway for neural signals, originating in the medulla, to propagate to the heart and generate cardiac pulses at the same frequency as neural bursts (Pokrovskii, 2005). Aligned with this, the ability to control our breathing rate and influence HRV, further suggests a need to consider a three-way interaction between the respiratory, cardiovascular and cognitive systems. Like the intrinsic rhythm generators (pacemaker and bursting neurons) in the brainstem (Del Negro, 2005; Morgado-Valle and Beltran-Parrazal, 2017), the heart is capable of producing rhythmic oscillations at a median frequency of ~1.25 Hz at 80 beats per minute. The exact origin of the cardiac beat-to-beat fluctuations are not fully understood, although most research suggests that the physiological needs of gas exchange and blood circulation (Mayr et al., 2012), as well as intrinsic calcium dependent pacemaker cells drive this rhythm (Yaniv et al., 2013). In the context of neurocardio interplay, some research suggests that the heart rate may serve as a resonant frequency and that higher EEG frequencies are perfect harmonics, and can thus be directly modulated by the heart rate or through a more complex pathway involving breathing rates (Klimesch, 2013; Mather and Thayer, 2018).

Besides linkages via the vagus nerve, heat rate or more specifically HRV can also influence cognition through coordinated brain region differences in blood flow, which are in turn associated with differences in functional connectivity (Liang et al., 2013). The brain regions that show strong across-subject correlations between functional connectivity strength and blood flow include mPFC, ACC, posterior cingulate cortex, and insula (Liang et al., 2013). Thus, these brain regions, which we have previously identified and emphasized with respect to respiratory regulation, are among those that also experience high regional blood flow and serve as hub regions for whole brain functional connectivity (Mather and Thayer, 2018). These characteristics make oscillations in blood flow especially likely to impact these specific brain regions. Notably, these regions have also been shown to undergo functional connectivity changes in volitional breath control and meditation practices (reviewed in Hölzel et al., 2011; Vago and Silbersweig, 2012; Tang et al., 2015a, b). Future studies need to use closed-loop methods to address whether oscillations in blood flow and oscillations in electrical neural activity are simply correlative or have causal relationships (Mishra and Gazzaley, 2015).

As another mode of interaction between the respiratory, cardiac and cognitive systems, it has been recently found that OSNs, through their mechano-sensory ability to entrain to respiratory oscillations, and transfer signals to limbic regions, can in turn alter physiological responses such as heart rate (Wu et al., 2017). While the exact mechanism of interaction from mechanical rhythms in the nostril to physiological heart rate changes are not fully established, the potential for these interactions to influence cognition is apparent. Similar to Zelano et al. (2016), who found differences in emotional processing during inhalation vs exhalation, Garfinkel et al. (2014) found differences in processing of fearful and neutral faces in different phases of the heartbeat (systole vs diastole); there is evidence that systolic/diastolic time intervals and blood pressure can be modulated respiration (Van Leeuwen and Kuemmell, 1987; Herakova et al., 2017).

Finally, cardiac rhythms also receive feedback from brain regions controlling executive function; there is evidence that a central pacemaker in the cingulum, may be able to modulate heart rate in intervals of ~10 s, thus influencing HRV (Pfurtscheller et al., 2017). Interestingly, Ave marie prayers and yogic mantras, similar to slow-breathing traditions previously mentioned, have also been shown to slow breath rate to 10 s (Bernardi et al., 2001), while the heart rate also has oscillatory components at the same frequency (.1 Hz) (Mather and Thayer, 2018). In turn, slow breathing at this rate (.1 Hz) has been shown to enhance HRV (relative to the spontaneous breathing rate), which has been associated with general improvement in well-being (Beda et al., 2014; Brown et al., 1993; Lin et al., 2014). This evidence further supports the framework that attentive breath control practices, driven by frontal cortical circuits, may be capable of inducing direct neurophysiological changes as well as further cardiac-mediated cognitive changes.

10. Future directions

Here, we summarize directions for future research to address the missing links in the mechanistic understanding of respiratory regulation of cognition.

In human clinical & translational research, studies of respiratory-locked neural activity have been predominantly limited to limbic system processes. Future investigations must target higher cognitive executive function processes using appropriate cognitive task paradigms that are controlled by brain regions demonstrated to be influenced by respiratory rhythms, such as the ACC and insula.

Interestingly, olfactory deficits have previously been associated with cognitive decline (Graves et al., 1999; Hatta et al., 2017) especially in Alzheimer’s disease patients (Uhlhaas and Singer, 2006) and type-2-diabetes patients (Lietzau et al., 2017). Aberrant olfaction has also been demonstrated as a valid predictor in dementia (Adams et al., 2018) and major depressive disorder (Negoias et al., 2016). Future investigations should continue to explore the potential for olfactory processing as a biomarker for diagnosis for various disorders. These studies should not be limited to probing the sensory modality of olfaction (olfactory detection), but should also investigate its motor modality (i.e., breathing rate generation), as well as obtain simultaneous HRV measures for a multidimensional understanding of the role of olfactory, respiratory and cardiac rhythms in neuropsychiatric disorders.

Early childhood trauma has been associated with higher risk of neuropsychiatric disorders and cognitive dysfunction (Gould et al., 2012). In response to trauma or stressful events and environments, a normal sympathetic system will increase respiratory rate. Continued exposure and response to such environments may permanently disrupt intrinsic respiratory rates in this vulnerable population. Croy et al. (2013) show that adults with a history of childhood trauma have decreased olfactory bulb volumes. The downstream effects of disrupted respiration and OB processes may affect executive function regions directly linked in this network, such as the ACC and insula; these mechanistic pathways need to be systematically investigated in this vulnerable population as it has potential implications for cognitive dysfunction as well as circuit-targeted therapeutics. Indeed, suggestive of bidirectional linkages in these circuits, our own research shows that individuals with childhood trauma who practice paying attention to their breath, in turn demonstrate enhanced ACC-insula functional connectivity, enhanced sustained attention abilities, as well as reduced distractibility and hyperactivity (Mishra et al., 2017). Thus, future studies in childhood trauma would benefit from interrogation of multidimensional systems, including neurophysiology, respiratory rate and HRV monitoring as important potential biomarkers of psychopathology.

In this review, we have discussed the role of neural oscillations, as a means of temporal communication across global and local brain networks, in concert with respiration rate and HRV. For the low frequency oscillations measured using EEG/iEEG/LFPs, heart rate and respiratory rate may be critical resonant frequencies, that are used for global functional connectivity. In turn, the low frequency oscillations may organize and modulate higher frequency oscillations within local neural networks, as observed in studies of cross-frequency coupling (Zhong et al;, 2017; Voytek et al., 2010; Cohen et al., 2009; Canolty et al., 2010). Further elucidation is required to understand the role of frequency band-specific (theta, alpha, beta, gamma) and brain region specific neural oscillations, their intercoupling, and coupling with respiratory and cardiac oscillations. In this context, investigations of differential modulation of these physiological processes in relaxed versus stressed states, either induced cognitive stress (Kirschbaum et al., 1993), or physical stress such as during exercise, are also pertinent.

Of particular therapeutic focus in the future may be multimodal approaches that pair neuromodulation approaches, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), or deep brain stimulation (DBS), or vagus nerve stimulation with breath-control practices. Neuromodulation approaches have independently demonstrated therapeutic benefit in neuropsychiatric disorders (Lo and Widge, 2017; Mishra and Ganguly, 2018; Raedt et al., 2015) and pairing them with breath-control practices may enhance intervention efficacy, mediated via synchronization of specific brain oscillations.

11. Conclusion

This review discusses linkages between respiratory control and neuro-cognitive circuitry and also highlights associations with cardiac rhythms. Key players in this network are:

Intrinsic pace-making neurons within the preBötC capable of generating phasic control in upstream limbic and cortical regions, in response to needs of cognitive control.

Cingulum “top-down” control of LC phasic firing, for regulation of attentional states, and pacemaker capabilities that can modulate heart rate.

Mechano-sensitivity of OSNs, which are capable of inducing global synchrony via respiration entrained oscillations in limbic and cortical brain circuits.

“Bottom-up” feedback from the cardiovascular system that can deliver hemodynamic oscillations to coordinate and strengthen cognitive functional networks.

As per the limitations of this review, a discussion of the interaction of these interacting oscillatory systems with neuromodulators (norepinephrine, dopamine, and others) is beyond-scope. Further, due to our focus on interactions between respiration and cognitive circuitry, we do not discuss evidence linking respiratory interactions with the sensory (visual/auditory) processing systems. The intricacies of the interplay of respiration and cognition are not yet fully understood, but future work must continue to examine both the “bottom-up” effects of breath on cognition, and the “top-down” control of cognition on breath, and how this information may be leveraged for novel neurotherapeutics.

Funding

This research was supported by UC San Diego School of Medicine start-up funds (DR, JM), Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration Career Development Award (7IK2BX003308 to DR), and a Career Award for Medical Scientists from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (1015644 to DR).

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors profess no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adams DR, Kern DW, Wroblewski KE, McClintock MK, Dale W, Pinto JM, 2018. Olfactory dysfunction predicts subsequent dementia in older U.S. adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 66 (1), 140–144. 10.1111/jgs.15048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adrian ED, 1942. Olfactory reactions in the brain of the hedgehog. J. Physiol. 100 (4), 459–473. 10.1113/jphysiol.1942.sp003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adrian ED, 1950. The electrical activity of the mammalian olfactory bulb. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2 (1–4), 377–388. 10.1016/0013-4694(50)90075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleksandrov VG, Ivanova TG, Aleksandrova NP, 2007. Prefrontal control of respiration. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 58 (SUPPL. 5), 17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alheid GF, Milsom WK, McCrimmon DR, 2004. Pontine influences on breathing: an overview. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 143 (2–3), 105–114. 10.1016/J.RESP.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson TM, Ramirez J-M, 2017. Respiratory rhythm generation: triple oscillator hypothesis [version 1; referees: 3 approved]. F1000Research 6. 10.12688/f1000research.10193.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson TM, Garcia AJ, Baertsch NA, Pollak J, Bloom JC, Wei AD, et al. , 2016. A novel excitatory network for the control of breathing. Nature 536 (7614), 76–80. 10.1038/nature18944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arshamian A, Iravani B, Majid A, Lundström JN, 2018. Respiration modulates olfactory memory consolidation in humans. J. Neurosci. 38 (48), 10286–10294. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3360-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Bloom FE, 1981. Activity of norepinephrine-containing locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats anticipates fluctuations in the sleep-waking cycle. J. Neurosci. 1 (8), 876–886. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-08-00876.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones Gary, Cohen JD, 2005. An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: adaptive gain and optimal performance. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 28 (1), 403–450. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch RP, Liu KKL, Ma QDY, Ivanov PC, 2014. Three independent forms of cardio-respiratory coupling: transitions across sleep stages. Comput. Cardiol. 41 (January), 781–784. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beda A, Simpson DM, Carvalho NC, Carvalho ARS, 2014. Low-frequency heart rate variability is related to the breath-to-breath variability in the respiratory pattern. Psychophysiology 51 (2), 197–205. 10.1111/psyp.12163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi L, Sleight P, Bandinelli G, Cencetti S, Fattorini L, Wdowczyc-Szulc J, Lagi A, 2001. Effect of rosary prayer and yoga mantras on autonomic cardiovascular rhythms: comparative study. BMJ 323, 22–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhimani NT, Kulkarni NB, Kowale A, Salvi S, 2011. Effect of Pranayama on stress and cardiovascular autonomic function. Indian J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 55 (4), 370–377. Retrieved from. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23362731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi L, Wang J, Luo Z, Chen S, Geng F, Chen Y, et al. , 2013. Enhanced excitability in the infralimbic cortex produces anxiety-like behaviors. Neuropharmacology 72, 148–156. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biskamp J, Bartos M, Sauer J-F, 2017. Organization of prefrontal network activity by respiration-related oscillations. Sci. Rep. 7, 45508. 10.1038/srep45508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnen NI, Müller MLTM, Kotagal V, Koeppe RA, Kilbourn MA, Albin RL, Frey KA, 2010. Olfactory dysfunction, central cholinergic integrity and cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 133 (6), 1747–1754. 10.1093/brain/awq079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnavion P, Mickelsen LE, Fujita A, Lecea Lde, Jackson AC, 2016. Hubs and spokes of the lateral hypothalamus: cell types, circuits and behaviour. J. Physiol. 594 (22), 6443–6462. 10.1113/JP271946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JA, Worhunsky PD, Gray JR, Tang Y-Y, Weber J, Kober H, 2011. Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108 (50), 20254–20259. 10.1073/pnas.1112029108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RP, Gerbarg PL, 2005. Sudarshan kriya yogic breathing in the treatment of stress, anxiety, and depression: part II—clinical applications and guidelines. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 11 (4), 711–717. 10.1089/acm.2005.11.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TE, Beightol LA, Koh J, Eckberg DL, 1993. Important influence of respiration on human R-R interval power spectra is largely ignored. J. Appl. Physiol. 75 (5), 2310–2317. 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.5.2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RP, Gerbarg PL, Muench F, 2013. Breathing practices for treatment of psychiatric and stress-related medical conditions. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 36, 121–140. 10.1016/j.psc.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA, Felmingham KL, Kemp AH, Barton M, Peduto AS, Rennie C, et al. , 2005. Neural networks of information processing in posttraumatic stress disorder: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol. Psychiatry 58 (2), 111–118. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonviso N, Amat C, Litaudon P, 2006. Respiratory modulation of olfactory neurons in the rodent brain. Chem. Senses 31 (2), 145–154. 10.1093/chemse/bjj010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushara KO, Grafman J, Hallett M, 2001. Neural correlates of auditory-visual stimulus onset asynchrony detection. J. Neurosci. 21 (1), 300–304 https://doi.org/21/1/300[pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell AP, Phillips KM, Hoehle LP, Feng AL, Bergmark RW, Caradonna DS, et al. , 2017. Depression symptoms and lost productivity in chronic rhinosinusitis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 118 (3), 286–289. 10.1016/j.anai.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canolty RT, Knight RT, 2010. The functional role of cross-frequency coupling. Trends Cogn. Sci. 14 (11), 506–515. 10.1016/j.tics.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Roy S, Sachdev RNS, Heck DH, 2012. Dynamic correlation between whisking and breathing rhythms in mice. J. Neurosci. 32 (5), 1653–1659. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4395-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael ST, Clugnet M-C, Price JL, 1994. Central olfactory connnections in the Macaque monkey. J. Comp. Neurol. 346, 403–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnevali L, Sgoifo A, Trombini M, Landgraf R, Neumann ID, Nalivaiko E, 2013. Different patterns of respiration in rat lines selectively bred for high or low anxiety. PLoS One 8 (5), 1–9. 10.1371/journal.pone.0064519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin NL, 2004. Functional organization of the parabrachial complex and inter-trigeminal region in the control of breathing. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 143 (2), 115–125. 10.1016/j.resp.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi VN, Müller C, Wolfenstetter T, Yanovsky Y, Draguhn A, Tort ABL, Brankačk J, 2016. Hippocampal respiration-driven rhythm distinct from Theta oscillations in awake mice. J. Neurosci. 36 (1), 162–177. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2848-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Salkovskis PM, Chalkley AJ, 1985. Respiratory control as a treatment for panic attacks. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 16 (1), 23–30. 10.1016/0005-7916(85)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MX, Frank MJ, 2009. Neurocomputational models of basal ganglia function in learning, memory and choice. Behav. Brain Res. 199 (1), 141–156. 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly T, Yu Y, Grosmaitre X, Wang J, Santarelli LC, Savigner A, et al. , 2015. G protein-coupled odorant receptors underlie mechanosensitivity in mammalian olfactory sensory neurons. PNAS 112 (2), 590–595. 10.1073/pnas.1418515112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M, Patel G, Shulman GL, 2008. The Reorienting system of the human brain: from environment to theory of mind. Neuron 58 (3), 306–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craigmyle NA, 2013. The beneficial effects of meditation: contribution of the anterior cingulate and locus coeruleus. Front. Psychol. 4 (731), 1–16. 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer CK, Friedman JH, Amick MM, 2010. Olfaction and apathy in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 16 (2), 124–126. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley HD, Garfinkel SN, 2018. The influence of physiological signals on cognition. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 19, 13–18. 10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Croy I, Negoias S, Symmank A, Schellong J, Joraschky P, Hummel Thomas, 2013. Reduced olfactory bulb volume in adults with a history of childhood maltreatment. Chem. Senses 38, 679–684. 10.1093/chemse/bjt037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Kam K, Sherman D, Janczewski WA, Zheng Y, Jack L, et al. , 2016. Defining preBötzinger Complex rhythm and pattern generating neural microcircuits in vivo. Neuron 91 (3), 602–614. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.07.003.Defining. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Negro CA, 2005. Sodium and calcium current-mediated pacemaker neurons and respiratory rhythm generation. J. Neurosci. 25 (2), 446–453. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2237-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhingra RR, Dutschmann M, Galán RF, Dick TE, 2017. Kölliker-Fuse nuclei regulate respiratory rhythm variability via a gain-control mechanism. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 312 (2), R172–R188. 10.1152/ajpregu.00238.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhingra RR, Furuya WI, Bautista TG, Dick TE, Galán RF, Dutschmann M, 2019. Increasing local excitability of brainstem respiratory nuclei reveals a distributed network underlying respiratory motor pattern formation. Front. Physiol 10. 10.3389/fphys.2019.00887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick TE, Bellingham MC, Richter DW, 1994. Pontine respiratory neurons in anesthetized cats. Brain Res. 636 (2), 259–269. 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick TE, Hsieh YH, Dhingra RR, Baekey DM, Galán RF, Wehrwein E, Morris KF, 2014. Cardiorespiratory coupling: common rhythms in cardiac, sympathetic, and respiratory activities. Prog. Brain Res. 209, 191–205. 10.1016/B978-0-444-63274-6.00010-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutschmann M, Dick TE, 2012. Pontine mechanisms of respiratory control. Comprehensive Physiology. American Cancer Society, pp. 2443–2469. 10.1002/cphy.c100015. Retrieved from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutschmann M, Kron M, Mörschel M, Gestreau C, 2007. Activation of Orexin B receptors in the pontine Kölliker-Fuse nucleus modulates pre-inspiratory hypoglossal motor activity in rat. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 159 (2), 232–235. 10.1016/j.resp.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman JL, 1986. Neurophysiology of breathing in mammals. Comprehensive Physiology . John Wiley & Sons, Inc, Hoboken, NJ, USA. 10.1002/cphy.cp010409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanini A, Bower JM, 2005. Variable coupling between olfactory system activity and respiration in Ketamine/Xylazine anesthetized rats. J. Neurophysiol. 93 (6), 3573–3581. 10.1152/jn.01320.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanini A, Spano P, Bower JM, 2003. Ketamine–Xylazine-Induced slow (< 1.5 Hz) oscillations in the rat piriform (olfactory) cortex are functionally correlated with respiration. J. Neurosci. 23 (22), 7993–8001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forte G, Favieri F, Casagrande M, 2019. Heart rate variability and cognitive function: a systematic review. Front. Neurosci. 13, 710. 10.3389/fnins.2019.00710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller P, Sherman D, Pedersen NP, Saper CB, Lu J, 2011. Reassessment of the structural basis of the ascending arousal system. J. Comp. Neurol. 519 (5), 933–956. 10.1002/cne.22559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlong TM, McDowall LM, Horiuchi J, Polson JW, Dampney RAL, 2014. The effect of air puff stress on c-Fos expression in rat hypothalamus and brainstem: central circuitry mediating sympathoexcitation and baroreflex resetting. Eur. J. Neurosci. 39 (9), 1429–1438. 10.1111/ejn.12521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbott PLA, Warner TA, Jays PRL, Salway P, Busby SJ, 2005. Prefrontal cortex in the rat: projections to subcortical autonomic, motor, and limbic centers. J. Comp. Neurol. 492 (2), 145–177. 10.1002/cne.20738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel SN, Minati L, Gray MA, Seth AK, Dolan RJ, Critchley HD, 2014. Fear from the heart: sensitivity to fear stimuli depends on individual heartbeats. J. Neurosci. 34 (19), 6573–6582. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3507-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Estrada MT, Freeman WJ, 1980. Effects of carnosine on olfactory bulb EEG, evoked potentials and DC potentials. Brain Res. 202 (2), 373–386. 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Buka SL, 2008. Childhood respiratory disease and the risk of anxiety disorder and major depression in adulthood. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 162 (8), 774. 10.1001/archpedi.162.8.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould F, Clarke J, Heim C, Harvey PD, Majer M, Nemeroff CB, 2012. The effects of child abuse and neglect on cognitive functioning in adulthood. J. Psychiatr. Res. 46 (4), 500–506. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graeff FG, 2004. Serotonin, the periaqueductal gray and panic. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 28 (3), 239–259. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves AB, Bowen JD, Rajaram L, McCormick WC, McCurry SM, Schellenberg GD, Larson EB, 1999. Impaired olfaction as a marker for cognitive decline. Neurology 53 (7), 1480–1487. Retrieved from. http://n.neurology.org/content/53/7/1480.abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray PA, Janczewski WA, Mellen N, McCrimmon DR, Feldman JL, 2001. Normal breathing requires preBötzinger complex neurokinin-1 receptor-expressing neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 4 (9), 927. 10.1038/nn0901-927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grecksch G, Zhou D, Franke C, Schröder U, Sabel B, Becker A, Huether G, 1997. Influence of olfactory bulbectomy and subsequent imipramine treatment on 5-hydroxytryptaminergic presynapses in the rat frontal cortex: behavioural correlates. Br. J. Pharmacol. 122 (8), 1725–1731. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosmaitre X, Santarelli LC, Tan J, Luo M, Ma M, 2007. Dual functions of mammalian olfactory sensory neurons as odor detectors and mechanical sensors. Nat. Neurosci. 10 (3), 348–354. 10.1038/nn1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberly LB, Price JL, 1978. Association and commissural fiber systems of the olfactory cortex of the rat. I. Systems originating in the piriform cortex and adjacent areas. J. Comp. Neurol. 178 (4), 711–740. 10.1002/cne.901780408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan SF, Cornish JL, Goodchild AK, 2013. Respiratory, metabolic and cardiac functions are altered by disinhibition of subregions of the medial prefrontal cortex. J. Physiol. 591 (23), 6069–6088. 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.262071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta T, Katayama N, Hotta C, Higashikawa M, Kato K, 2017. Odor identification and cognitive function in older adults: evidence from the Yakumo study. SM Gerontol. Geriatric Res. 1 (2), 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Heck DH, McAfee SS, Liu Y, Babajani-Feremi A, Rezaie R, Freeman WJ, et al. , 2017. Breathing as a fundamental rhythm of brain function. Front. Neural Circuits 10 (January), 1–8. 10.3389/fncir.2016.00115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimer L, Zahm DS, Trimble MR, Hoesen GWVan., 2007. Anatomy of Neuropsychiatry: the New Anatomy of the Basal Forebrain and Its Implications for Neuropsychiatric Illness. Academic Press, San Diego. [Google Scholar]

- Herakova N, Nwobodo N, Wang Y, Chen F, Zheng D, 2017. Effect of respiratory pattern on automated clinical blood pressure measurement: an observational study with normotensive subjects. Clin. Hypertens. 23, 15. 10.1186/s40885-017-0071-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero JL, Khuvis S, Yeagle E, Cerf M, Mehta AD, 2018. Breathing above the brain stem: volitional control and attentional modulation in humans. J. Neurophysiol. 119, 145–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölzel BK, Lazar SW, Gard T, Schuman-Olivier Z, Vago DR, Ott U, 2011. How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 6 (6), 537–559. 10.1177/1745691611419671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howells FM, Stein DJ, Russell VA, 2012. Synergistic tonic and phasic activity of the locus coeruleus norepinephrine (LC-NE) arousal system is required for optimal attentional performance. Metab. Brain Dis. 27 (3), 267–274. 10.1007/s11011-012-9287-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K, Kawakami K, Onimaru H, Okada Y, 2017. The respiratory control mechanisms in the brainstem and spinal cord: integrative views of the neuroanatomy and neurophysiology. J. Physiol. Sci. 67 (1), 45–62. 10.1007/s12576-016-0475-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito J, Roy S, Liu Y, Cao Y, Fletcher M, Lu L, et al. , 2014. Whisker barrel cortex delta oscillations and gamma power in the awake mouse are linked to respiration. Nat. Commun. 5. 10.1038/ncomms4572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar BKS, 1985. Light on Pranayama: the Yogic Art of Breathing. Crossroad Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Jerath R, Crawford MW, Barnes VA, Harden K, 2015. Self-Regulation of breathing as a primary treatment for anxiety. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 40, 107–115. 10.1007/s10484-015-9279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessberger J, Zhong W, Brankačk J, Draguhn A, 2016. Olfactory bulb field potentials and respiration in sleep-wake states of mice. Neural Plast August 5 Retrieved from. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/np/2016/4570831/abs/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jodo E, Chiang C, Aston-Jones G, 1998. Potent excitatory influence of prefrontal cortex activity on noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons. Neuroscience 83 (1), 63–79. 10.1016/S0306-4522(97)00372-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahana MJ, 2006. The Cognitive correlates of human brain oscillations. J. Neurosci. 26 (6), 1669–1672. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3737-05c.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S, Pedersen NP, Yokota S, Hur EE, Fuller PM, Lazarus M, et al. , 2013. Glutamatergic signaling from the parabrachial nucleus plays a critical role in hypercapnic arousal. J. Neurosci. 33 (18), 7627–7640. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0173-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepecs A, Uchida N, Mainen ZF, 2007. Rapid and precise control of sniffing during olfactory discrimination in rats. J. Neurophysiol. 98, 205–213. 10.1152/jn.00071.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khroud NK, Saadabadi A, 2018. Neuroanatomy, Brain, Locus Ceruleus. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island, FL. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Pirke K-M, Hellhammer DH, 1993. The’ Trier Social Stress Test’ - A tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology 28, 76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimesch W, 2013. An algorithm for the EEG frequency architecture of consciousness and brain body coupling. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7 (766), 1–4. 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli P, Soler ZM, Nguyen SA, Muus JS, Schlosser RJ, 2016. The association between olfaction and depression: a systematic review. Chem. Senses 41 (6), 479–486. 10.1093/chemse/bjw061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiya Naohiro, Smith JC, 1999. Neuronal pacemaker for breathing visualized in vitro. Nature 400 (July), 20–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiya N, Oku Y, Yokota S, Oyamada Y, Yasui Y, Okada Y, 2014. Anatomical and functional pathways of rhythmogenic inspiratory premotor information flow orginating in the pre-bötzinger complex in the rat medulla. Neuroscience 268, 194–211. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozasa EH, Balardin JB, Sato JR, Chaim KT, Lacerda SS, Radvany J, et al. , 2018. Effects of a 7-Day meditation retreat on the brain function of meditators and non-meditators during an attention task. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 12 (222), 1–9. 10.3389/fnhum.2018.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krukoff TL, Morton TL, Harris KH, Jhamandas JH, 1992. Expression of c-fos protein in rat brain elicited by electrical stimulation of the pontine parabrachial nucleus. J. Neurosci. 12 (9), 3582–3590. 10.1523/jneurosci.12-09-03582.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krukoff Teresa L., Harris KH, Jhamandas JH, 1993. Efferent projections from the parabrachial nucleus demonstrated with the anterograde tracer Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin. Brain Res. Bull. 30 (1–2), 163–172. 10.1016/0361-9230(93)90054-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krusemark EA, Novak LR, Gitelman DR, Li W, 2013. When the sense of smell meets emotion: anxiety-state-dependent olfactory processing and neural circuitry adaptation. J. Neurosci. 33 (39), 15324–15332. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1835-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunik ME, Roundy K, Veazey C, Souchek J, Richardson P, Wray NP, Stanley MA, 2005. Surprisingly high prevalence of anxiety and depression in chronic breathing disorders. Chest 127 (4), 1205–1211. 10.1016/S0012-3692(15)34468-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwana S, Tsunekawa N, Yanagawa Y, Okada Y, Kuribayashi J, Obata K, 2006. Electrophysiological and morphological characteristics of GABAergic respiratory neurons in the mouse pre-Bötzinger complex. Eur. J. Neurosci. 23, 667–674. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavezzi AM, Ferrero S, Roncati L, Matturri L, Pusiol T, 2016. Impaired orexin receptor expression in the Kölliker–fuse nucleus in sudden infant death syndrome: possible involvement of this nucleus in arousal pathophysiology. Neurol. Res. 38 (8), 706–716. 10.1080/01616412.2016.1201632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazar SW, Kerr CE, Wasserman RH, Gray JR, Greve DN, Treadway MT, et al. , 2005. Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. Neuroreport 16 (17), 1893–1897. Retrieved from. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1361002/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Janczewski WA, Yackle K, Kam K, Pagliardini S, Krasnow MA, Feldman JL, 2016. The peptidergic control circuit for sighing. Nature 530 (7590), 293–297. 10.1038/nature16964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]