Abstract

Background

Allodynia and hyperalgesia are common signs in individuals with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), mainly attributed to sensitization of the nociceptive system. Appropriate diagnostic tools for the objective assessment of such hypersensitivities are still lacking, which are essential for the development of mechanism‐based treatment strategies.

Objectives

This study investigated the use of pain‐autonomic readouts to objectively detect sensitization processes in CRPS.

Methods

Twenty individuals with chronic CRPS were recruited for the study alongside 16 age‐ and sex‐matched healthy controls (HC). All individuals underwent quantitative sensory testing and neurophysiological assessments. Sympathetic skin responses (SSRs) were recorded in response to 15 pinprick and 15 noxious heat stimuli of the affected (CRPS hand/foot) and a control area (contralateral shoulder/hand).

Results

Individuals with CRPS showed increased mechanical pain sensitivity and increased SSR amplitudes compared with HC in response to pinprick and heat stimulation of the affected (p < 0.001), but not in the control area (p > 0.05). Habituation of pinprick‐induced SSRs was reduced in CRPS compared to HC in both the affected (p = 0.018) and slightly in the control area (p = 0.048). Habituation of heat‐induced SSR was reduced in CRPS in the affected (p = 0.008), but not the control area (p = 0.053).

Conclusions

This is the first study demonstrating clinical evidence that pain‐related autonomic responses may represent objective tools to quantify sensitization processes along the nociceptive neuraxis in CRPS (e.g. widespread hyperexcitability). Pain‐autonomic readouts could help scrutinize mechanisms underlying the development and maintenance of chronic pain in CRPS and provide valuable metrics to detect mechanism‐based treatment responses in clinical trials.

Significance

This study provides clinical evidence that autonomic measures to noxious stimuli can objectively detect sensitization processes along the nociceptive neuraxis in complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) (e.g. widespread hyperexcitability). Pain‐autonomic readouts may represent valuable tools to explore pathophysiological mechanisms in a variety of pain patients and offer novel avenues to help guide mechanism‐based therapeutic strategies.

1. INTRODUCTION

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a multifactorial disease, including sensory, vasomotor, sudomotor, trophic and motor dysfunction in the affected limb (Birklein et al., 2018; Marinus et al., 2011). Based on the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), CRPS is classified as chronic primary pain (Nicholas et al., 2019) and the most prominent factor for the diagnosis based on the Budapest criteria (Harden et al., 2010) is the presence of ‘continuing pain, which is disproportionate to any inciting event’, such as a fracture, sprain or elective surgical intervention. In particular, hyperalgesia and allodynia to mechanical stimuli are hallmark signs in individuals with CRPS. A major contributing factor to such pain hypersensitivities is sensitization of the nociceptive system (Gierthmühlen et al., 2012; Jensen & Finnerup, 2014; Latremoliere & Woolf, 2009; Reimer et al., 2016).

Previous studies employing quantitative sensory testing (QST) in CRPS have demonstrated widespread hypersensitivities in previously unaffected areas, suggesting generalized sensitization (Drummond et al., 2018; Reimer et al., 2016). While QST allows the investigation of sensory loss (i.e., hypoesthesia/hypoalgesia) and gain (i.e., hyperalgesia and allodynia), the method relies heavily on patient reports and remains purely subjective in its nature (Hansson et al., 2007). Beyond psychophysical measures, objective readouts of sensitization are essential to detect meaningful alterations in somatosensory function (Garcia‐Larrea & Hagiwara, 2019). Such objective readouts may represent useful outcome measures for clinical trials on novel therapeutic interventions targeting sensitization processes. In this regard, autonomic readouts have been proposed as candidate measures as enhanced pain‐related autonomic responses, such as increased sympathetic skin responses (SSR) and reduced SSR habituation, have been reported in patients with chronic pain (De Tommaso et al., 2017; Garcia‐Larrea & Hagiwara, 2019; Ozkul & Ay, 2007; Schestatsky et al., 2007). Other autonomic measures, such as pupil dilation, blood pressure and heart rate variability, have been related to pain rein healthy individuals (Koenig et al., 2014; Nickel et al., 2017; Treister et al., 2012; Wildemeersch et al., 2018).

More recently, studies employing experimental pain models in healthy individuals have demonstrated candidate autonomic surrogate markers of experimentally induced central sensitization (Scheuren et al., 2020; van den Broeke et al., 2019). Alongside the development of mechanical hyperalgesia, pinprick‐induced SSRs were increased and their habituation was reduced in the area of experimentally induced central sensitization (Scheuren et al., 2020). These findings suggest that altered pain–autonomic interaction (i.e., enhanced autonomic responses to nociceptive input), which can occur at multiple levels of the neuraxis (Benarroch, 2001), might be utilized as an objective proxy of sensitization in pain patients.

The objective of the current study was to investigate the value of pain–autonomic readouts for the objective assessment of sensitization along the nociceptive neuraxis in individuals with CRPS presenting with marked signs of mechanical hyperalgesia. We hypothesized that (1) individuals with CPRS show increased pain‐related SSRs compared to HC and (2) SSRs are enhanced in both the affected and a remote, control area in CRPS. The latter implies a potential contribution of widespread neuronal hyperexcitability, i.e., central sensitization, to the pain phenotype.

2. METHODS

2.1. Individuals

Individuals with CRPS were recruited at the Department of Physical Medicine and Rheumatology of the Balgrist University Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland. Individuals between 18 and 80 years of age with a clear diagnosis of chronic CRPS based on state‐of‐the‐art diagnostic criteria including the Budapest criteria (Harden et al., 2010) and the IASP classification of CRPS (Nicholas et al., 2019) were included in the study. Exclusion criteria comprised any neurological disorder (e.g., polyneuropathy, radiculopathy, entrapment neuropathy, central nervous system disorder), history of chronic pain prior to the development of CRPS or history of psychiatric disorder.

Age‐ and sex‐matched healthy control (HC) individuals with no history of or current neurological disorder or psychiatric disorder were recruited for this study. Additional exclusion criteria for HC individuals were acute or chronic pain and intake of medication (i.e., antidepressants, opioids, anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines).

All individuals provided written informed consent prior to study participation. The study was approved by the local ethics committee Kantonale Ethikkommission Zürich (EK‐04/2006, PB_2016‐02051) and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Study design

An extensive pain phenotyping test battery was performed in all individuals and separated into two study visits. Both visits were performed in a quiet room at constant temperature (22°C). We performed a focused clinical neurological examination (visit 1), quantitative pain assessments (visit 1), QST (visit 1) and SSR recordings in response to noxious heat and pinprick stimulation randomized to either visit 1 or visit 2. All assessments were performed in the affected area (i.e., CRPS‐affected limb with the highest pain intensity) and a remote, control area (i.e., clinically unaffected area) defined according to the location of the affected area. The control area was (1) the contralateral shoulder if the affected area was the hand, as previous studies have demonstrated that CRPS can spread to the contralateral extremity over the course of the disease (Reimer et al., 2016; Rommel et al., 2001; Van Rooijen et al., 2013) and (2) the contralateral hand if the affected area was the foot. This followed the protocol of a larger multi‐cohort study, of which the present study was part. The affected and control areas were matched in all HCs and the terms ‘affected’ and ‘control’ area will be used to describe the matched areas in HCs throughout the manuscript and figures. All participants, individuals with CRPS and HC, completed online questionnaires including the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Questionnaires (HADS; Stern, 2014) and Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS; Sullivan et al., 1995).

2.3. Clinical examination and pain assessments

All individuals with CRPS underwent a clinical examination by a physician specialized in CRPS (F.B.) to assess all signs and symptoms including vasomotor, sudomotor, trophic changes, motor changes and neglect‐like symptoms. They were asked to rate their current and average pain intensity over the last 7 days on a numeric rating scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable) with 1/10 as the subjective pain threshold. Semi‐quantitative bedside sensory testing was performed in all HCs to exclude any overt sensory impairments. This included the assessment of vibration detection using a tuning fork, light touch using a cotton swab, pinprick using a safety pin and thermal testing using a cold and warm thermoroller (Rolltemp II, Somedic SenseLab AB, Sweden). The bedside sensory examination was also performed in the control area of all individuals with CRPS to exclude any clinical signs of sensory dysfunction in this area.

2.4. Quantitative sensory testing

All individuals underwent a subset of the QST battery according to the German Research Network on Neuropathic Pain (Rolke et al., 2006) to assess gain of function in large (Aβ‐) and small (Aδ‐ and C‐) fibre function or corresponding central pathways. Heat pain thresholds (HPT), mechanical pain thresholds (MPT), mechanical pain sensitivity (MPS) and dynamic mechanical allodynia (DMA) were assessed by a QST‐certified experimenter. QST was performed in the affected and control areas to investigate potential signs of localized and widespread sensitization, respectively. A familiarization procedure was conducted in an unaffected area other than the affected and control areas prior to the actual testing. QST values were normalized to reference values from the German Research Network on Neuropathic Pain (Rolke et al., 2006) (specific to body region, age and sex) and presented as z‐scores.

2.5. Pain–autonomic readouts: Stimulation paradigm

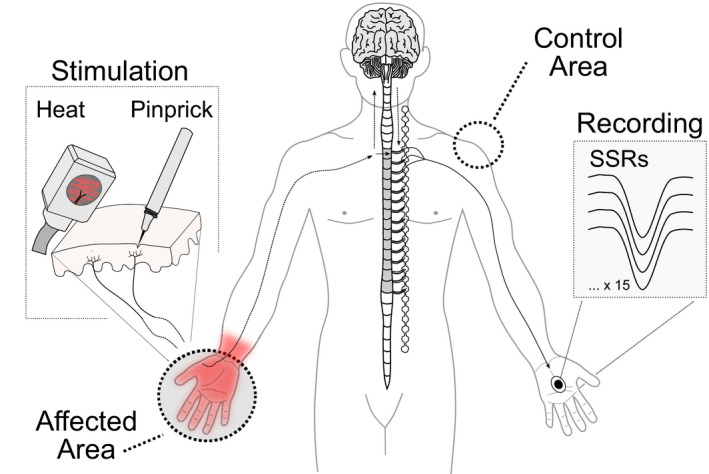

Fifteen contact heat and 15 pinprick stimuli were applied to the affected and control areas in a randomized order with a 2‐min break between stimulation areas (Figure 1). The two modalities (pinprick and heat) were chosen to investigate modality‐specific SSR alterations in relation to psychophysical readouts (i.e., pain ratings). The stimulus modality (heat or pinprick) was randomized between two study visits across all individuals. Contact heat stimuli (baseline temperature 42°C, destination temperature 52°C, ramp 70°C/s; Kramer et al., 2012) were applied to the skin with a 27 mm diameter CHEPs thermode (PATHWAY Pain and Sensory Evaluation System, Medoc Ltd., Ramat Yishai, Israel). Weighted pinprick stimuli (256 mN) were applied to the testing sites with the modified pinprick stimulator with an integrated contact trigger (MRC Systems, Heidelberg, Germany). The interstimulus interval was 13–17 s for both stimulus modalities.

FIGURE 1.

Pain–autonomic interaction. Recordings of sympathetic skin responses (SSRs) in response to noxious heat or pinprick stimulation of the affected and control area.

2.6. Sympathetic skin response recording set‐up

All recordings were performed in a supine position. Time‐locked SSRs were recorded in response to contact heat and pinprick stimulation of the affected and control areas. Surface electrodes (Ambu BlueSensor NF, Ballerup, Denmark) were attached to the recording site, which consisted of the hand contralateral to the affected area. The skin temperature of the recording and stimulation sites was kept constant (≥ 32°C) with heating lamps throughout all measurements (Deltombe et al., 1998). The recording site was prepared with skin prep sandpaper tape (Red Dot™ Trace Prep, 3M) and alcohol. The active electrode was attached to the hand palm, and the reference electrode was attached to the hand dorsum. SSRs were measured as the voltage difference between the active and the reference electrode (mV). SSRs were sampled at 2000 Hz with a pre‐amplifier and a 0.1–12 kHz frequency filter. The recording window was set to 1 s pre‐trigger and 9 s post‐trigger in a customized program based on LabView (V2.6.1. CHEP, ALEA30 Solutions). Signals contaminated with movement artefacts or non‐time‐locked responses were excluded offline. SSR latencies defined as the first deflection point of the signal and SSR amplitudes (i.e., peak‐to‐peak responses) were detected using a customized algorithm in R statistical software for MacOS Mojave 10.14.6, version 4.1.0. (Scheuren et al., 2020).

2.7. Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed in R statistical software (version 4.1.0. MacOS Mojave 10.14.6) and chosen according to the data distribution, which was tested by means of histograms and quantile–quantile plots. The statistical significance was set at 0.05. Bonferroni correction was performed to adjust for multiple comparisons.

Differences between cohorts (HC and CRPS) in terms of age, questionnaire scores and QST parameters (z‐scores) were assessed with two‐sample t‐tests. We used linear mixed effect models (‘lmer’ function from R package ‘lme4’) with post hoc repeated measures (R package ‘emmeans’) to test the difference in the stimulus–response function (i.e., MPS) between both cohorts. For each area (affected and control), we examined the effect of ‘cohort’ (CRPS and HC) and stimulus ‘intensity’ (8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256 and 512 mN) on pain ratings (NRS 0–100) with ‘individual’ as a random effect. The interaction effect ‘cohort x intensity’ was included in the model.

Moreover, we used linear mixed effect models (‘lmer’ function from R package ‘lme4’) to test the effect of the ‘cohort’ and ‘area’ on (a) pinprick pain ratings, (b) heat pain ratings, (c) pinprick‐induced SSR and (d) heat‐induced SSR with post‐hoc multiple comparisons (R package ‘emmeans’). The interaction effect ‘cohort x area’ was included in all models and ‘individual’ was added as a random effect. Habituation of pain ratings and SSRs were assessed as (1) the percent change (normalized values) over time within each individual and (2) absolute reductions in SSR amplitudes over time. The former was performed as absolute SSR amplitudes can be variable, and SSR habituation has been shown to be a reliable measure (De Schoenmacker et al., 2022). For this, we separated the 15 stimuli into three consecutive stimulation ‘blocks’ (‘first’, ‘middle’ and ‘last’) and calculated the mean ratings and SSRs for each stimulation block. First, habituation was calculated as the remaining percent (%) of the ‘last’ compared to the ‘first’ block (last/first × 100). Again, we used linear mixed effect models (R package ‘lme4’) to test the effect of the ‘cohort’ (CRPS and HC) and ‘area’ (affected and control) on the habituation (%) of (a) pinprick pain ratings, (b) heat pain ratings, (c) pinprick‐induced SSRs and (d) heat‐induced SSRs. The interaction effect ‘cohort x area’ was included in all models and ‘individual’ was added as a random effect. Post hoc multiple comparisons were performed for each model using the R package ‘emmeans’. Second, we investigated habituation in terms of absolute reductions in pain ratings and amplitudes across all three blocks. We used linear mixed effect models (R package ‘lme4’) to test the effect of ‘cohort’ (CRPS and HC) and stimulation ‘block’ (‘first’, ‘middle’ and ‘last’) on (a) pinprick pain ratings, (b) heat pain ratings, (c) pinprick‐induced SSR and (d) heat‐induced SSR for both the affected and the control area separately. The interaction effect ‘cohort x block’ was included in all models and ‘individual’ was added as a random effect. Post‐hoc multiple comparisons were performed for each model using the R package ‘emmeans’.

Lastly, pearman correlation analyses were performed to test the correlation between (a) pinprick pain ratings and pinprick‐induced SSR and (b) heat pain ratings and heat‐induced SSRs to test the effect of pain appraisal on autonomic readouts (Mischkowski et al., 2019).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Clinical and pain characteristics

A total of 20 individuals with CRPS (17 females and 3 males) and 16 HC (14 females and 2 males) participated in the study. The two cohorts did not differ in age (CRPS: 44.9 ± 12.8 years; HC: 41.8 ± 13.3 years; t = 0.7; p = 0.45). The time between visit 1 and visit 2 was 6.6 ± 6.8 days in individuals with CRPS and 11.7 ± 24.8 days in HC. Individuals with CRPS presented with pain duration of 38 ± 35.6 months (range 6–144 months), a mean current pain intensity of NRS 4.9 ± 2.3 and 7‐day average pain intensity of NRS 5.4 ± 2.5. Moreover, individuals with CRPS presented with higher pain catastrophizing scores (CRPS: 22.9 ± 12; HC: 5.9 ± 7.9; t = 5.1; p < 0.001) and higher anxiety (CRPS: 8.1 ± 3.9; HC: 3.6 ± 2.8; t = 4.0; p < 0.001) and depression scores (CRPS: 6.8 ± 5.0; HC: 1.5 ± 1.7; t = 4.41; p < 0.001) than HCs. All clinical and pain characteristics are presented in Table 1. Individual characteristics can be found in Table S1.

TABLE 1.

Clinical and pain characteristics

| CRPS characteristics | |

|---|---|

| CRPS limb, n (%) | |

| Upper limb | 14 (70) |

| Lower limb | 6 (30) |

| Multiple limbs | 3 (15) |

| Inciting event, n (%) | |

| Bone fracture | 10 (50) |

| Sprain | 4 (20) |

| Surgical intervention | 5 (25) |

| Bruising trauma | 1 (5) |

| Other signs and symptoms, n (%) | |

| Trophic changes | 7 (35) |

| Oedema | 10 (50) |

| Sudomotor changes | 8 (40) |

| Vasomotor changes | 10 (50) |

| Motor changes | 15 (75) |

| Neglect‐like symptoms | 3 (15) |

| Medication, n (%) | |

| NSAID | 8 (40) |

| SSNRI | 4 (20) |

| Opioids | 5 (25) |

| Gabapentin | 3 (15) |

| Pregabalin | 3 (15) |

| Lidocaine | 1 (5) |

| Antidepressants | 5 (25) |

Abbreviations: CRPS, complex regional pain syndrome; NSAID, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs; SSNRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

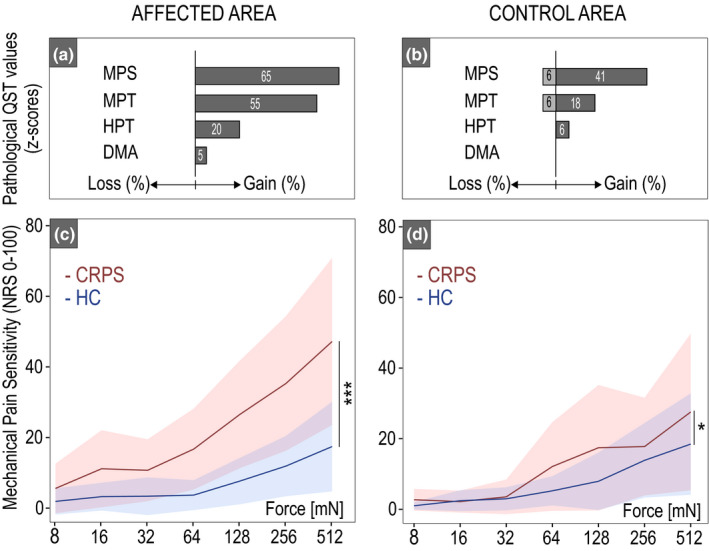

3.2. Quantitative sensory testing

In the affected area, individuals with CRPS showed higher MPS z‐scores (hyperalgesia to mechanical pinprick stimuli) compared to the HC group (t = 2.52, p = 0.02) (Table 2A). In the control area, MPS did not differ between CRPS and HC (t = −0.16, p = 0.87). Individuals with CRPS presented with a leftward shift in the stimulus–response function (MPS) compared to HC in the affected area for the 64–512 mN pinprick intensity (F = 13.7; p < 0.001; Figure 2C) and in the control area (F = 2.2; p = 0.045) for the 128 mN (t = 2.46, p = 0.02) and 512 mN (t = 2.35, p = 0.02) pinprick intensity (Figure 2D). All post hoc comparisons for each stimulus intensity can be found in Table S2. There was no difference in MPT between CRPS and HC in both the affected (t = 1.03, p = 0.31) and control area (t = −0.57, p = 0.57). There was also no difference in HPT between CRPS and HC in both the affected (t = 1.52, p = 0.14) and the control areas (t = 1.43, p = 0.16). Comparing the two areas within the CRPS group, the MPT was lower in the affected compared to the control area (t = −2.47, p = 0.03), but there was no difference in HPT (t = −1.17, p = 0.26) and MPS (= − 1.48, p = 0.16) between the affected and control areas. Individuals with CRPS presented with pathological QST z‐scores (±1.96) in both the affected (up to 65%) (Figure 2a) and control areas (up to 41%) (Figure 2b). Some HC also presented with gain of function in the affected (HPT: 13% [n = 2]; MPT: 13% [n = 2]; MPS: 25% [n = 4]) and control area (HPT: 0%; MPT: 13% [n = 2]; MPS: 19% [n = 3]).

TABLE 2.

Quantitative sensory testing parameters

| HPT (mean ± SD) | MPT (mean ± SD) | MPS (mean ± SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Affected Area | n.s | n.s | * |

| CRPS | 0.79 ± 1.35 | 1.66 ± 1.66 | 2.17 ± 1.35 |

| HC | 0.16 ± 1.15 | 1.30 ± 0.85 | 1.19 ± 0.97 |

| B. Control Area | n.s | n.s | n.s |

| CRPS | 0.07 ± 0.94 | 0.80 ± 1.30 | 1.47 ± 1.87 |

| HC | −0.37 ± 0.82 | 1.06 ± 1.30 | 1.55 ± 0.87 |

Note: Mean and standard deviation (SD) are shown for z‐scores of heat pain thresholds (HPT), mechanical pain thresholds (MPT) and mechanical pain sensitivity (MPS) in (a) the affected and (b) control areas. Significant differences between groups (CRPS vs HC) are labelled as *p < 0.05.

FIGURE 2.

Quantitative sensory testing. The frequencies of pathological QST z‐scores (±1.96 SD) in complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) are shown for the affected (a) and control areas (b). The shift in the stimulus–response function in terms of mechanical pain sensitivity is shown for the CRPS (red) compared to HC (blue) in both the affected (c) and control areas (d). *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. DMA, dynamic mechanical allodynia; HPT, heat pain threshold; MPT, mechanical pain threshold.

3.3. Pain ratings

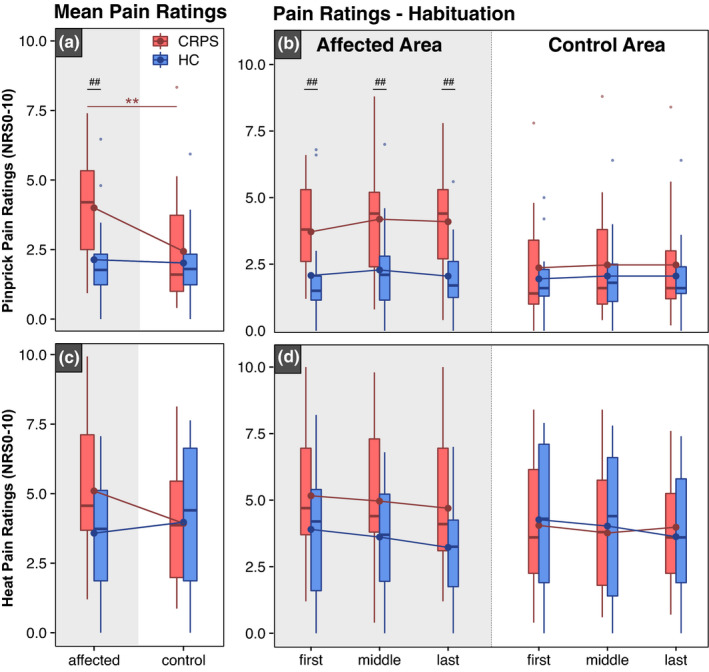

3.3.1. Pinprick pain ratings and habituation

Individuals with CRPS presented with higher mean pinprick pain ratings compared to HC after stimulation of the affected area, but not the control area (Figure 3a). In individuals with CRPS, pain ratings were higher in the affected (NRS 4.0 ± 1.8) compared to the control area (NRS 2.4 ± 2.1). In the HC group, pain ratings did not differ between the affected (NRS 2.1 ± 1.6) and the control areas (NRS 2.0 ± 1.4). Pinprick pain ratings did not habituate in both the affected and control areas for both CRPS and HC (F = 0.10, p = 0.75; Table 3a). In both cohorts (CRPS and HC), pinprick pain ratings did not differ across the three stimulation blocks in the affected and control areas. All model statistics and post‐hoc comparisons can be found in Tables S3a, S4a, S5a, S6.

FIGURE 3.

Pinprick and heat pain ratings. Mean pinprick pain ratings (a) and habituation of pinprick ratings (b) from the ‘first’, ‘middle’ and ‘last’ stimulation blocks are shown in the top panel. Mean heat pain ratings (c) and habituation of heat pain ratings (d) are shown in the bottom panel. Pain ratings are shown after stimulation of the control and affected areas in patients with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS—red) and healthy controls (HC—blue). Significances are shown for comparisons between areas: **p < 0.01 and between cohorts: ## p < 0.01

TABLE 3.

Habituation of pain ratings (a–b) and sympathetic skin responses (c–d)

| CRPS | HC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First block | Last block | Habituation (%) | First block | Last block | Habituation (%) | CRPS vs HC | |

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | p‐value | |

| (a) Pinprick pain rating (NRS) | |||||||

| i. Affected | 3.7 ± 1.6 | 4.1 ± 1.9 | 119 ± 49 | 2.1 ± 1.9 | 1.9 ± 1.2 | 120 ± 48 | n.s |

| ii. Control | 2.4 ± 2.1 | 2.5 ± 2.1 | 116 ± 61 | 2.1 ± 1.4 | 2.0 ± 1.6 | 109 ± 44 | n.s |

| (b) Heat pain rating (NRS) | |||||||

| i. Affected | 5.1 ± 2.5 | 4.7 ± 2.7 | 96 ± 20 | 3.9 ± 2.4 | 3.2 ± 1.8 | 94 ± 31 | n.s |

| ii. Control | 4.0 ± 2.4 | 3.9 ± 2.6 | 141 ± 169 | 4.3 ± 2.7 | 6.3 ± 2.4 | 87 ± 18 | n.s |

| (c) Pinprick‐induced SSR (mV) | |||||||

| i. Affected | 3.7 ± 4.2 | 2.2 ± 2.2 | 81 ± 69 | 1.3 ± 1.7 | 0.4 ± 0.6 | 33 ± 32 | * |

| ii. Control | 1.9 ± 2.0 | 1.1 ± 1.2 | 67 ± 82 | 1.9 ± 1.7 | 0.5 ± 0.7 | 22 ± 23 | * |

| (d) Heat‐induced SSR (mV) | |||||||

| i. Affected | 6.5 ± 4.1 | 3.8 ± 2.2 | 62 ± 28 | 4.2 ± 2.7 | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 36 ± 25 | ** |

| ii. Control | 6.4 ± 4.0 | 4.6 ± 3.7 | 69 ± 26 | 4.6 ± 3.8 | 2.1 ± 2.5 | 49 ± 34 | n.s |

Note: Habituation was computed as the per cent (%) of the last compared to the first block (last/first × 100) for both pain ratings and sympathetic skin response (SSR). The comparison of habituation (%) between both cohorts (CRPS vs HC) for both pain ratings and sympathtic skin responses (SSR) is shown in the last column.

Significance levels: *<0.05; **<0.01.

Abbreviations: CRPS, complex regional pain syndrome; HC, healthy control; NRS, numeric rating scale.

3.3.2. Heat pain ratings and habituation

Mean heat pain ratings did not differ between CRPS and HC after stimulation of the affected (CRPS: 5.1 ± 2.6 and HC: 3.6 ± 2.0) and control area (CRPS: 3.9 ± 2.2 and HC: 3.9 ± 2.6) (Figure 3c). Moreover, there was no difference in the habituation of heat pain ratings in individuals with CRPS compared to HC in both the affected and control areas (F = 1.46, p = 0.24) (Table 3b). In both cohorts (CRPS and HC), heat pain ratings did not differ across all three stimulation blocks (i.e., first, middle and last) in both the affected and control areas. All model statistics and post hoc comparisons can be found in Tables S3b, S4b, S5b, S6b.

3.4. Pain‐related SSR

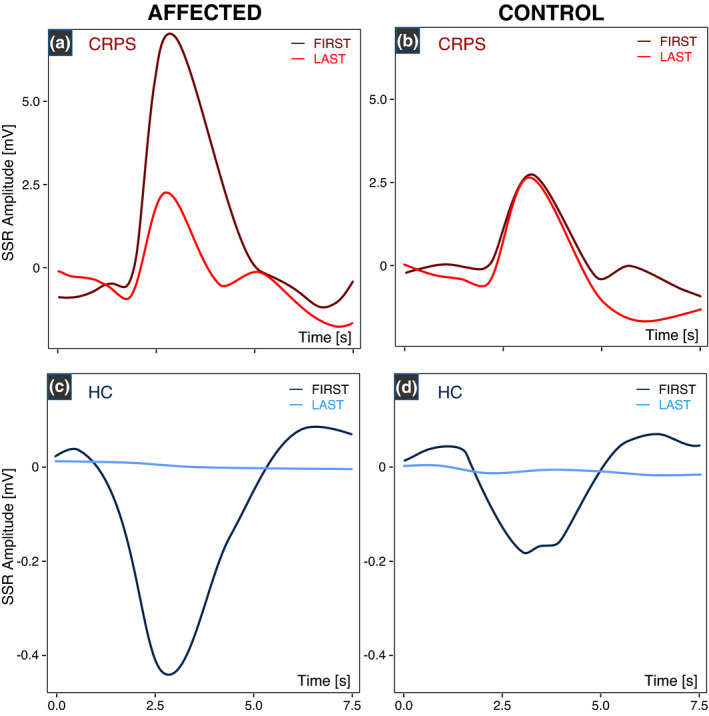

3.4.1. Pinprick‐induced SSR amplitudes and habituation

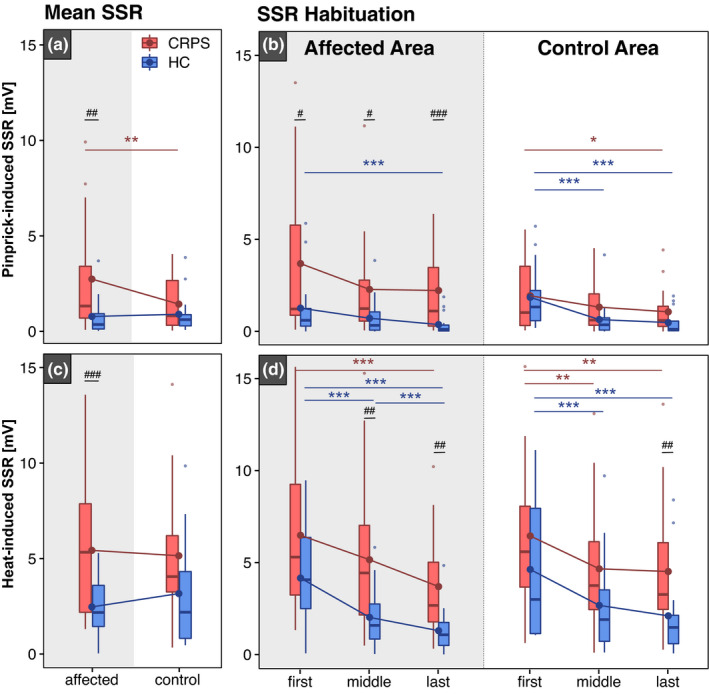

Figure 4 shows an illustrative example of pinprick‐induced SSRs in CRPS and HC. A total of 1.6 ± 1.7 pinprick‐induced SSR traces had to be excluded due to artefacts. Due to technical issues during the recording of pinprick‐induced SSRs in one individual, the 15 traces had to be excluded from the analysis. Overall, pinprick‐induced SSRs were higher in individuals with CRPS compared to HC after stimulation of the affected, but not the control area (Figure 5a). Individuals with CRPS presented with higher pinprick‐induced SSRs in the affected (2.7 ± 2.9 mV) compared to the control area (1.4 ± 1.4 mV). In HCs, pinprick‐induced SSRs did not differ between the affected (0.8 ± 1.0 mV) and control area (0.9 ± 1.1 mV). In addition, individuals with CRPS showed reduced habituation of pinprick‐induced SSRs compared to HC in both the affected and control areas (F = 6.19, p = 0.02; observed statistical power 69.7%) (Table 3c). In detail, pinprick‐induced SSRs did not differ across all three stimulation blocks in the affected area in CRPS (Figure 5b, left). In the control area of CRPS, however, pinprick‐induced SSRs were higher in the first compared to the last block (Figure 5b, right). In HC, pinprick‐induced SSRs were higher in the first compared to the last block in the affected area. In the control area of HCs, pinprick‐induced SSRs were higher in the first compared to both the middle and last block (Figure 5b, right). Model statistics and post hoc comparisons can be found in Tables S3c, S4c, S5c, S6c.

FIGURE 4.

An illustrative example of pinprick‐induced sympathetic skin responses (SSRs) in complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) and healthy control (HC). Pinprick‐induced SSRs are higher in the individual with CRPS (a, b) compared to HC (c, d). In the patient with CRPS, pinprick‐induced SSRs are still prominent in the last stimulation block (i.e., reduced habituation) in both the affected (a) and control areas (b). In the HC, pinprick‐induced SSRs are no longer present in the last stimulation block (i.e., normal physiological habituation). Please note the different y‐axis scales for CRPS and HC.

FIGURE 5.

Pinprick‐ and heat‐induced sympathetic skin responses (SSRs). Mean pinprick‐induced SSRs (a) and SSR habituation (b) from the ‘first’, ‘middle’ and ‘last’ stimulation blocks are shown in the top panel. Mean heat‐induced SSRs (c) and SSR habituation (d) are shown in the bottom panel. SSR amplitudes are shown in response to stimulation of the affected and control areas in individuals with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS—red) and healthy controls (HC—blue). Significances are shown for comparisons between areas: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and between cohorts: # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001.

3.4.2. Heat‐induced SSR amplitudes and habituation

A total of 1.7 ± 1.7 heat‐induced SSR traces had to be excluded due to artefacts. Heat‐induced SSRs were higher in individuals with CRPS compared to HC after stimulation of the affected, but not the control area (Figure 5c). Heat‐induced SSRs did not differ between the affected vs. control area in both individuals with CRPS (5.4 ± 3.6 mV vs. 5.1 ± 3.6 mV, respectively) and in HC (2.5 ± 3.2 mV vs. 3.2 ± 2.9 mV, respectively). Moreover, individuals with CRPS showed reduced habituation of heat‐induced SSRs in the affected, but not the control (F = 10.93, p = 0.003) (Table 3d). In detail, both cohorts (CRPS and HC) showed higher heat‐induced SSRs in the first compared to both the middle and the last stimulation block in both the affected (Figure 5d, left) and control areas (Figure 5d, right). All model statistics and post hoc comparisons can be found in Tables S3d, S4d, S5d and S6d.

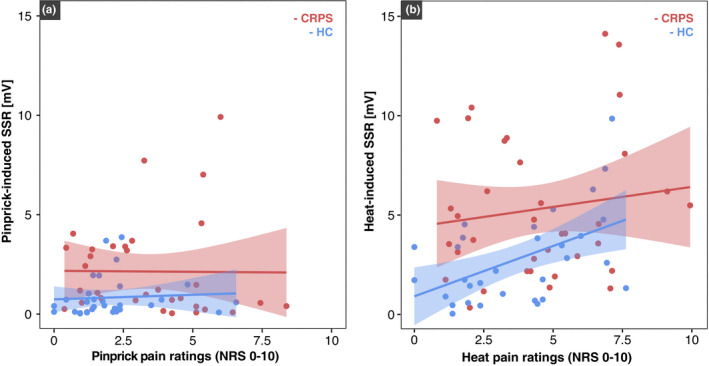

3.4.3. Correlation between pain‐related SSRs and pain ratings

In both CRPS and HC, there was no correlation between the amplitude of pinprick‐induced SSRs and the pinprick pain ratings (HC: R = 0.07, p = 0.72; CRPS: R = −0.01, p = 0.96) (Figure 6a). The amplitude of heat‐induced SSRs was, however, correlated with heat pain ratings in HC (R = 0.5, p = 0.004), but not in CRPS (R = 0.13, p = 0.45; Figure 6b).

FIGURE 6.

Association between sympathetic skin response (SSR) amplitudes and pain ratings in response to noxious heat (a) and pinprick stimulation (b) for complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS‐red) and healthy control (HC‐blue).

4. DISCUSSION

The present findings provide compelling clinical evidence that pain–autonomic interaction represents a surrogate marker of sensitization of the nociceptive system in CRPS. Individuals with CRPS presented with enhanced pinprick‐induced autonomic responses alongside marked signs of mechanical hyperalgesia. Moreover, pinprick‐induced SSR habituation was reduced in CRPS compared to HC. These findings further corroborate results from experimental pain models in healthy individuals (Scheuren et al., 2020; van den Broeke et al., 2019) and demonstrate that autonomic responses can objectively detect nociceptive sensitization.

4.1. Pain–autonomic interaction depicts mechanical hypersensitivities

Individuals with CRPS presented with pronounced mechanical hyperalgesia, which could be demonstrated by a leftward shift in their stimulus–response function (i.e., increased MPS) as well as increased pinprick pain ratings in the affected area compared to HC. Alongside these psychophysical changes in the affected area, pinprick‐induced SSRs were also increased and SSR habituation was reduced in CRPS compared to HC. These findings demonstrate the clinical utility of pain–autonomic interaction with respect to objectively substantiating the clinical observation of mechanical hyperalgesia. Building up on our previous study showing increased pinprick‐induced SSRs and reduced SSR habituation after experimentally induced central sensitization (Scheuren et al., 2020), these results indicate that pain–autonomic interaction may be a potential surrogate marker of nociceptive sensitization. In addition, there was no difference in the habituation of pinprick pain ratings in CRPS compared to HC. This can be explained by the low pinprick ratings in HC (i.e., floor effect), which limits the analysis of pain rating habituation in this cohort. Hence, the objective recording of autonomic readouts compared to only pain ratings offers a great advantage to characterize habituation (or the lack thereof) to repetitive mechanical stimuli.

In the present study, individuals with CRPS presented with mechanical, but not heat hyperalgesia. Moreover, heat pain ratings did not differ between CRPS and HC. Nevertheless, heat‐induced SSRs were increased and SSR habituation was reduced in CRPS compared to HC in the affected area. Heat‐induced SSRs did, however, show a stronger reduction over time (38%) compared to pinprick‐induced SSRs (19%). As such, investigating SSR habituation provided added value to detect modality‐specific hypersensitivities (i.e., mechanical vs heat) in this cohort. It is, however, important to note that pinprick‐ and heat‐induced SSRs were recorded on two different days and thus differentially influenced by mental and emotional factors that may vary between visits. As such, future studies should assess mental and emotional factors prior to each testing session as well as each testing area to enable direct comparisons between modalities and areas for both psychophysical and autonomic readouts.

Overall, these findings are in line with previous studies demonstrating increased autonomic responses in individuals with chronic pain (Ozkul & Ay, 2007; Schestatsky et al., 2007) as well as human experimental pain models (Scheuren et al., 2020; van den Broeke et al., 2019). As nociceptive and autonomic pathways intersect at multiple levels of the central nervous system, it is highly conceivable that autonomic responses, such as SSRs induced by noxious stimuli, can indirectly reflect the existence of provoked pain. A variety of alterations in autonomic responses to noxious stimuli have been reported, such as changes in heart rate, pupil dilation, blood pressure and electrodermal activity (Kyle & McNeil, 2014). Previous investigations have demonstrated that sympathetic responses to noxious stimuli result from nociceptive processes rather than the subjective perception of pain (Loggia & Napadow, 2012; Nickel et al., 2017; Treister et al., 2012). This emphasizes the potential use of autonomic responses (i.e., reduced SSR habituation) as an indirect objective readout of nociceptive sensitization in pain patients.

4.2. Dissociation between subjective pain ratings and autonomic responses

In the present study, we observed a dissociation between subjective heat pain ratings and objective autonomic responses. Autonomic responses to noxious stimuli have previously been related to pain appraisal, indicating that stimuli that are perceived as more painful will in turn generate increased sympathetic and/or decreased parasympathetic outflow (Mischkowski et al., 2019). Moreover, reduced or absent SSR amplitudes have been reported in patients with documented hypoesthesia and reduced afferent integrity (Veciana et al., 2007). Although individuals with CRPS and HC presented with similar heat pain ratings, heat‐induced SSRs were increased in CRPS compared to HC. Moreover, heat‐induced SSRs did not correlate with the respective heat pain ratings in CRPS. This is intriguing as it indicates that the enhanced autonomic responses were not only driven by stimulus‐induced arousal due to the perceived pain intensity. Notably, the modulation of autonomic responses to noxious input may be partially independent of perceptual processes. SSRs may reflect a nociceptive‐specific response driven through direct spinal somato‐sympathetic reflexes or brainstem mechanisms involved in both nociceptive and autonomic function (Benarroch, 2001; Kyle & McNeil, 2014; Sato & Schmidt, 1973). Subjective perception of pain is likely more dependent on secondary evaluative (affective/emotional) influences. In contrast, in HC, the magnitude of the autonomic responses was associated with heat‐pain intensities. The dissociation between psychophysical and autonomic responses in CRPS but not HC implies that physiological‐mediating effects of pain appraisal on autonomic responses (as seen in HC) may undergo pathological changes in individuals with chronic pain. One can thus postulate a state of generalized hyperexcitability in individuals with CRPS, possibly rendering the autonomic nervous system more susceptible to noxious input, irrespective of the perceived stimulus intensity. This may be mediated by sensitization processes involving key substrates implicated in both nociceptive and autonomic processes at spinal and/or supraspinal levels (Benarroch, 2001; Schestatsky et al., 2007). While the present data negate a simple linear relationship between perceived pain intensity and the observed autonomic responses in CRPS, SSRs may still be influenced, at least in part, by higher‐order cognitive and affective processes (Barnes et al., 2021; Colagiuri & Quinn, 2018; Rainville et al., 2005). Individuals with CRPS may present with increased attention and/or negative expectation towards noxious input compared to HC, which may lead to higher autonomic responses in CRPS compared to HC. To our knowledge, the influence of cognitive and affective variables on pain‐related autonomic responses has only been investigated in a few studies (Kyle & McNeil, 2014). In particular, future investigations are warranted to assess the influence of attention and expectation on pain‐related autonomic responses in patients with chronic pain.

4.3. Disentangling peripheral and central sensitization

In the present study, the most prominent sign in individuals with CRPS was increased mechanical hyperalgesia in the affected area compared to HC, which reproduces findings of previous studies investigating QST profiles in individuals with CRPS (Gierthmühlen et al., 2012; Reimer et al., 2016). In addition, 41% of individuals with CRPS presented with pathological MPS scores and increased MPS compared to HC in the unaffected, control area, especially for the 128 and 512 mN pinprick intensity. These findings demonstrate signs of generalized sensitization of the nociceptive system. This is also in line with previous studies demonstrating hypersensitivities in the unaffected contralateral limb over the course of the disease (Huge et al., 2008; Reimer et al., 2016; Van Rooijen et al., 2013). In addition to widespread sensitivities upon QST, pinprick‐induced SSR habituation was reduced in CRPS compared to HC not only in the affected but also control area. These findings highlight that autonomic responses may be able to detect widespread signs of hyperexcitability (i.e., central sensitization). In conjunction with psychophysical readouts (i.e., pain ratings and QST), the observed enhanced autonomic responses offer a novel objective proxy of nociceptive sensitization in the present CRPS cohort.

In individuals with CRPS, it still remains challenging to localize pathological processes along the neuraxis, as alterations in somatosensory function can be driven by peripheral, spinal and/or supraspinal mechanisms (Birklein et al., 2018; Marinus et al., 2011). However, widespread somatosensory dysfunction has been related to central sensitization of the nociceptive system (Arendt‐Nielsen et al., 2017). In particular, mechanical hyperalgesia is a hallmark sign of central sensitization (Baron et al., 2017; Vollert et al., 2018) and was frequently documented in the current study. Moreover, the initial local inflammatory response in acute CRPS (i.e., keratinocyte proliferation, the release of inflammatory mediators, growth factors and mast cell accumulation) is known to normalize over time in the majority of patients, but not all. In such patients with reduced inflammatory responses over time, peripheral sensitization can no longer adequately explain pain hypersensitivities in chronic stages (Birklein et al., 2018). The exaggerated post‐traumatic inflammatory response may lead to sensitization of peripheral nociceptors and second‐order neurons in the spinal dorsal horn (Birklein & Schlereth, 2015), which can persist in chronic CRPS. This pathophysiological shift from acute to chronic CRPS has been related to the ipsilateral spread of hyperalgesia or even the spread to contralateral and remote areas in chronic CRPS (Drummond et al., 2018; Marinus et al., 2011; Reimer et al., 2016; Van Rijn et al., 2011). Nevertheless, some patients in the present study still presented with heat hyperalgesia in the affected area, which may be due to ongoing peripheral sensitization and represent an important contributor to their pain phenotype. In addition, the finding that individuals with CRPS present with lower pain thresholds to mechanical stimuli in the affected compared to the control area highlights that both peripheral and central sensitization may be contributing in a cumulative manner to the pain phenotype in chronic CRPS. As such, alterations in both psychophysical and objective autonomic responses after stimulation of the affected and the control area in CRPS suggest alterations beyond, but not excluding, the peripheral nervous system, possibly due to hyperexcitability at the level of the central nervous system. Taken together, pain–autonomic interaction holds the potential to objectively characterize sensitization processes that may occur at different levels of the nociceptive neuraxis. To further disentangle between peripheral and central processes, additional autonomic measures, such as pupil dilation and heart rate variability, may allow a more precise investigation of pain–autonomic interaction, encompassing both sympathetic activation and parasympathetic withdrawal (Loggia & Napadow, 2012; Möltner et al., 1990; Tousignant‐Laflamme et al., 2005).

While the present study offers novel insights into the potential use of autonomic readouts of sensitization in CRPS, there are some limitations that warrant a discussion. First, the small sample size limits the generalizability of the current findings to a broader cohort of individuals with CRPS. That said, the female/male ratio was slightly higher than suggested in epidemiological studies (Sandroni et al., 2003). Nevertheless, the primary aim of this study was to investigate differences in autonomic responses between CRPS and HC. As all HC were matched in terms of age, sex and areas tested, the overall gender distribution is not as relevant to the current study. Moreover, it would have been beneficial to have used the same control area across all individuals, as SSRs may be different after stimulation of the shoulder or hand. Lastly, our analysis did not take the intake of medication into account as subgrouping based on medication was not feasible due to the small sample size, as was withholding medication.

5. CONCLUSION

This study demonstrates that pain–autonomic readouts may represent objective tools to assess widespread (i.e., peripheral and central) sensitization of the nociceptive system in individuals with CRPS with evoked signs of mechanical hyperalgesia. Future studies are warranted to assess the applicability of pain–autonomic measures in a broader CRPS cohort, across different pain conditions and evaluate their clinical application at an individual level. In this sense, newly introduced pain–autonomic readouts may offer objective novel avenues to explore pathophysiological mechanisms in a wide variety of pain patients and could help guide mechanism‐based treatment strategies.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

P.S.S. contributed substantially to the study conception and design, data acquisition, analysis, data interpretation and drafted the manuscript. I.D.S. contributed to study design, data acquisition, data interpretation and revised the manuscript. J.R. contributed to the study conception and design, interpretation of results and revised the manuscript. F.B. contributed to the study conception, interpretation and revised the manuscript. A.C. contributed to the study conception and design, data interpretation and revised the research article for important intellectual content. M.H. made substantial contributions to study conception and design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation and revised the research article critically for important intellectual content. All authors gave their final approval of the version to be published.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was funded by the Clinical Research Priority Program Pain of the University of Zurich and the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) Grant (32003B_200482).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Supporting information

Table S1

Table S2

Table S3

Table S4

Table S5

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Mr. Tauschek L, Ms. Mollo A, Mr. Carisch S and Mr. Wymann B for their assistance with data acquisition.

Scheuren, P. S. , De Schoenmacker, I. , Rosner, J. , Brunner, F. , Curt, A. , & Hubli, M. (2023). Pain‐autonomic measures reveal nociceptive sensitization in complex regional pain syndrome. European Journal of Pain, 27, 72–85. 10.1002/ejp.2040

REFERENCES

- Arendt‐Nielsen, L. , Morlion, B. , Perrot, S. , Dahan, A. , Dickenson, A. , Kress, H. G. , Wells, C. , Bouhassira, D. , & Mohr Drewes, A. (2017). Assessment and manifestation of central sensitisation across different chronic pain conditions. European Journal of Pain (United Kingdom), 22, 216–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, K. , McNair, N. A. , Harris, J. A. , Sharpe, L. , & Colagiuri, B. (2021). In anticipation of pain: Expectancy modulates corticospinal excitability, autonomic response, and pain perception. Pain, 162, 2287–2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R. , Maier, C. , Attal, N. , Binder, A. , Bouhassira, D. , Cruccu, G. , Finnerup, N. B. , Haanpaä, M. , Hansson, P. , Hüllemann, P. , Jensen, T. S. , Freynhagen, R. , Kennedy, J. D. , Magerl, W. , Mainka, T. , Reimer, M. , Rice, A. S. C. , Segerdahl, M. , Serra, J. , … Treede, R. D. (2017). Peripheral neuropathic pain: A mechanism‐related organizing principle based on sensory profiles. Pain, 158, 261–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benarroch, E. E. (2001). Pain‐autonomic interactions: A selective review. Clinical Autonomic Research, 11, 343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birklein, F. , Ajit, S. K. , Goebel, A. , Perez, R. S. G. M. , & Sommer, C. (2018). Complex regional pain syndrome‐phenotypic characteristics and potential biomarkers. Nature Reviews. Neurology, 14, 272–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birklein, F. , & Schlereth, T. (2015). Complex regional pain syndrome‐significant progress in understanding. Pain, 156, S94–S103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colagiuri, B. , & Quinn, V. F. (2018). Autonomic arousal as a mechanism of the persistence of nocebo hyperalgesia. The Journal of Pain, 19, 476–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Schoenmacker, I. , Leu, C. , Curt, A. , & Hubli, M. (2022). Pain‐autonomic interaction is a reliable measure of pain habituation in healthy subjects. European Journal of Pain, 26, 1679–1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Tommaso, M. , Ricci, K. , Libro, G. , Vecchio, E. , Delussi, M. , Montemurno, A. , Lopalco, G. , & Iannone, F. (2017). Pain processing and vegetative dysfunction in fibromyalgia: A study by sympathetic skin response and laser evoked potentials. Pain Research and Treatment, 2017, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deltombe, T. , Hanson, P. , Jamart, J. , & Clérin, M. (1998). The influence of skin temperature on latency and amplitude of the sympathetic skin response in normal subjects. Muscle & Nerve, 21, 34–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, P. D. , Finch, P. M. , Birklein, F. , Stanton‐Hicks, M. , & Knudsen, L. F. (2018). Hemisensory disturbances in patients with complex regional pain syndrome. Pain, 159, 1824–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia‐Larrea, L. , & Hagiwara, K. (2019). Electrophysiology in diagnosis and management of neuropathic pain. Revue Neurologique (Paris), 175, 26–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gierthmühlen, J. , Maier, C. , Baron, R. , Tölle, T. , Treede, R. D. , Birbaumer, N. , Huge, V. , Koroschetz, J. , Krumova, E. K. , Lauchart, M. , Maihöfner, C. , Richter, H. , & Westermann, A. (2012). Sensory signs in complex regional pain syndrome and peripheral nerve injury. Pain, 153, 765–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson, P. , Backonja, M. , & Bouhassira, D. (2007). Usefulness and limitations of quantitative sensory testing: Clinical and research application in neuropathic pain states. Pain, 129, 256–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden, R. N. , Bruehl, S. , Perez, R. S. G. M. , Birklein, F. , Marinus, J. , Maihofner, C. , Lubenow, T. , Buvanendran, A. , MacKey, S. , Graciosa, J. , Mogilevski, M. , Ramsden, C. , Chont, M. , & Vatine, J. J. (2010). Validation of proposed diagnostic criteria (the “Budapest criteria”) for complex regional pain syndrome. Pain, 150, 268–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huge, V. , Lauchart, M. , Förderreuther, S. , Kaufhold, W. , Valet, M. , Azad, S. C. , Beyer, A. , & Magerl, W. (2008). Interaction of hyperalgesia and sensory loss in complex regional pain syndrome type I (CRPS I). PLoS ONE, 3, e2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, T. S. , & Finnerup, N. B. (2014). Allodynia and hyperalgesia in neuropathic pain: Clinical manifestations and mechanisms. Lancet Neurology, 13, 924–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, J. , Jarczok, M. N. , Ellis, R. J. , Hillecke, T. K. , & Thayer, J. F. (2014). Heart rate variability and experimentally induced pain in healthy adults: A systematic review. European Journal of Pain (United Kingdom), 18, 301–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, J. L. K. , Haefeli, J. , Curt, A. , & Steeves, J. D. (2012). Increased baseline temperature improves the acquisition of contact heat evoked potentials after spinal cord injury. Clinical Neurophysiology, 123, 582–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyle, B. N. , & McNeil, D. W. (2014). Autonomic arousal and experimentally induced pain: A critical review of the literature. Pain Research & Management, 19, 159–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latremoliere, A. , & Woolf, C. (2009). Central sensitization: A generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. The Journal of Pain, 10, 895–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loggia, M. L. , & Napadow, V. (2012). Multi‐parameter autonomic‐based pain assessment: More is more? Pain, 153, 1779–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinus, J. , Moseley, L. , Birklein, F. , Baron, R. , Maihöfner, C. , Kingery, W. S. , & van Hilten, J. (2011). Clinical features and pathophysiology of complex regional pain syndrome – Current state of the art. Lancet Neurology, 10, 637–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mischkowski, D. , Palacios‐Barrios, E. E. , Banker, L. , Dildine, T. C. , & Atlas, L. Y. (2019). Pain or nociception? Subjective experience mediates the effects of acute noxious heat on autonomic responses – Corrected and republished. Pain, 160, 1469–1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möltner, A. , Hölzl, R. , & Strian, F. (1990). Heart rate changes as an autonomic component of the pain response. Pain, 43, 81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, M. , Vlaeyen, J. W. S. , Rief, W. , Barke, A. , Aziz, Q. , Benoliel, R. , Cohen, M. , Evers, S. , Giamberardino, M. A. , Goebel, A. , Korwisi, B. , Perrot, S. , Svensson, P. , Wang, S. J. , & Treede, R. D. (2019). The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD‐11: Chronic primary pain. Pain, 160, 28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickel, M. M. , May, E. S. , Tiemann, L. , Postorino, M. , Ta Dinh, S. , & Ploner, M. (2017). Autonomic responses to tonic pain are more closely related to stimulus intensity than to pain intensity. Pain, 158, 2129–2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozkul, Y. , & Ay, H. (2007). Habituation of sympathetic skin response in migraine and tension type headache. Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic & Clinical, 134, 81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainville, P. , Bao, Q. V. H. , & Chrétien, P. (2005). Pain‐related emotions modulate experimental pain perception and autonomic responses. Pain, 118, 306–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimer, M. , Rempe, T. , Diedrichs, C. , Baron, R. , & Gierthmühlen, J. (2016). Sensitization of the nociceptive system in complex regional pain syndrome. PLoS ONE, 11, e0154553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolke, R. , Magerl, W. , Campbell, K. A. , Schalber, C. , Caspari, S. , Birklein, F. , & Treede, R. (2006). Quantitative sensory testing: A comprehensive protocol for clinical trials. European Journal of Pain, 10, 77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommel, O. , Malin, J. P. , Zenz, M. , & Jänig, W. (2001). Quantitative sensory testing, neurophysiological and psychological examination in patients with complex regional pain syndrome and hemisensory deficits. Pain, 93, 279–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandroni, P. , Benrud‐Larson, L. M. , McClelland, R. L. , & Low, P. A. (2003). Complex regional pain syndrome type I: Incidence and prevalence in Olmsted county, a population‐based study. Pain, 103, 199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato, A. , & Schmidt, R. F. (1973). Somatosympathetic reflexes: Afferent fibers, central pathways, discharge characteristics. Physiological Reviews, 53, 916–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schestatsky, P. , Kumru, H. , Valls‐Sole, J. , Valldeoriola, F. , Marti, M. J. , Tolosa, E. , & Chaves, M. L. (2007). Neurophysiologic study of central pain in patients with Parkinson disease. Neurology, 69, 2162–2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuren, P. S. , Rosner, J. , Curt, A. , & Hubli, M. (2020). Pain‐autonomic interaction: A surrogate marker of central sensitization. European Journal of Pain, 24, 2015–2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern, A. F. (2014). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Occupational Medicine (Chic Ill), 64, 393–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, M. J. L. , Bishop, S. R. , & Pivik, J. (1995). The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and validation. Psychological Assessment, 7, 524–532. [Google Scholar]

- Tousignant‐Laflamme, Y. , Rainville, P. , & Marchand, S. (2005). Establishing a link between heart rate and pain in healthy subjects: A gender effect. The Journal of Pain, 6, 341–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treister, R. , Kliger, M. , Zuckerman, G. , Aryeh, G. I. , & Eisenberg, E. (2012). Differentiating between heat pain intensities: The combined effect of multiple autonomic parameters. Pain, 153, 1807–1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Broeke, E. N. , Hartgerink, D. M. , Butler, J. , Lambert, J. , & Mouraux, A. (2019). Central sensitization increases the pupil dilation elicited by mechanical pinprick stimulation. Journal of Neurophysiology, 121, 1621–1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rijn, M. A. , Marinus, J. , Putter, H. , Bosselaar, S. R. J. , Moseley, G. L. , & Van Hilten, J. J. (2011). Spreading of complex regional pain syndrome: Not a random process. Journal of Neural Transmission, 118, 1301–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooijen, D. E. , Marinus, J. , & Van Hilten, J. J. (2013). Muscle hyperalgesia is widespread in patients with complex regional pain syndrome. Pain, 154, 2745–2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veciana, M. , Valls‐Solé, J. , Schestatsky, P. , Montero, J. , & Casado, V. (2007). Abnormal sudomotor skin responses to temperature and pain stimuli in syringomyelia. Journal of Neurology, 254, 638–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollert, J. , Magerl, W. , Baron, R. , Binder, A. , Enax‐Krumova, E. K. , Geisslinger, G. , Gierthmühlen, J. , Henrich, F. , Hüllemann, P. , Klein, T. , Lötsch, J. , Maier, C. , Oertel, B. , Schuh‐Hofer, S. , Tölle, T. R. , & Treede, R. (2018). Pathophysiological mechanisms of neuropathic pain: Comparison of sensory phenotypes in patients and human surrogate pain models. Pain, 159, 1090–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildemeersch, D. , Peeters, N. , Saldien, V. , Vercauteren, M. , & Hans, G. (2018). Pain assessment by pupil dilation reflex in response to noxious stimulation in anaesthetized adults. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica, 62, 1050–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1

Table S2

Table S3

Table S4

Table S5