BACKGROUND

Despite significant advances in contraceptive technology and the availability of a nonsurgical option for abortion, the benefits of family planning remain limited by the number of people who can access services. Contributing factors of low family planning use includes inadequate access to contraception and medication abortion, limited user and provider knowledge of family planning methods, inconsistent and/or incorrect use of contraception, and nonuse of contraception. Efforts to address these factors include significant investments in family planning services through global campaigns such as Family Planning 2020,1 efforts to create more effective supply chains,2 and the use of technology to facilitate access to services and information.3,4

The World Health Organization defines telemedicine broadly as the

delivery of health care services, where distance is a critical factor, by all health care professionals using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information for diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, and for the continuing education of health care providers, all in the interests of advancing the health of individuals and their communities.5

The use of telemedicine in obstetrics and gynecology has grown substantially in the last decade, with technology being used to counsel patients, consult with specialists, conduct ultrasounds, and manage illnesses during and after pregnancy, such as diabetes and postpartum depression.6-9 With telemedicine, care may either be delivered to a patient from (1) a remote location virtually and in real time (synchronous delivery) or (2) through static health information generated by health experts offline (asynchronous delivery). In the case of family planning, technology such as mobile phone applications (apps), websites, short message service/text messaging, telephone, and live audiovisual communication has been used to support contraceptive initiation, adherence, and continuation as well as deliver medication abortion services and follow-up to patients.

An assessment of the current use and existing research on telemedicine can help to guide clinicians in adding or testing the feasibility of telemedicine interventions for family planning within current clinical practice, encourage shared lessons across geographic contexts, and highlight spaces where more evidence is needed to reduce barriers to family planning use. Therefore, the aim of this study was to conduct a scoping review to identify and synthesize the evidence on the use of telemedicine for family planning.

METHODS

Protocol and Registration

The protocol for this scoping review was registered with the Open Science Framework and is publicly available.

Scope of Review

This scoping review was designed to map the evidence and highlight key knowledge gaps on the use of mobile phone, online platforms, remote monitoring and care delivery, and virtual visits for family planning. The key questions addressed in this review are:

KQ1. How has telemedicine been used for family planning?

KQ2. Who are the targets of telemedicine for family planning?

KQ3. What outcomes have been assessed for telemedicine for family planning?

We used the PRISMA extension10 for scoping reviews to guide the review and format for this article.

Eligibility criteria

Eligibility criteria were broadly set to ensure a wide capture of studies that describe and evaluate the use of telecommunications technology for 3 family planning services: contraception, medication abortion, and remote follow-up after medication abortion. To be included in this review, articles had to be in English, assess patient and/or provider populations, and describe an intervention where technology was used to provide a clinical service. Clinical service encompassed diagnostic, therapeutic, or preventive (including counseling) procedures. Additionally, articles that described peer-to-peer specialty consultations through virtual visits, direct-to-patient virtual visits, remote patient monitoring, mobile health and apps, and health care delivery apps/platforms were included. There were no restrictions placed on the year in which the study was published, the study design, or settings in which telemedicine for family planning was being used.

Search and screening strategy

We adapted a comprehensive set of search terms developed by the authors in collaboration with American College of Gynecologists Resource Center senior medical librarians for a previous systematic review of telehealth interventions for obstetrics and gynecology. A list of the search terms used for one database is included in Box 1. A comprehensive literature search was performed for primary literature in Cochrane Library, Cochrane Collaboration Registry of Controlled Trials, EMBASE, PubMed, and MEDLINE. The search was completed in September 2017 and updated in 2018 and July 2019 to capture additional studies published between initiation and completion of this review. The authors conducted abstract and full text review to identify peer-reviewed studies for inclusion. Observational studies (retrospective and prospective), systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and outcome evaluations of telemedicine for 3 family planning services were included. Qualitative and quantitative studies were included with no restrictions placed on sample size.

Box 1. Index and keyword terms used for one database.

Telemedicine/or telemedicine.ti,ab. or (interactive adj3 consult$).ti,ab. or (interactive adj3 diagnos$).ti,ab. or (health adj3 mobile).ti,ab. or (mobile adj3 health).ti,ab. or telehealth.ti,ab. or (ehealth or e-health).ti,ab. or (mhealth or m-health).ti,ab. or (telecommunications/and remote.ti,ab.) or remote consultation/or (remote adj3 consult$).ti,ab. or (remote adj3 telecommunication$).ti,ab. or (video adj3 visit$).ti,ab. or (remote adj3 visit$).ti,ab. or (remote adj3 monitor$).ti,ab. or (mobile adj3 app$).ti,ab. or (mobile adj3 media).ti,ab. or (digital adj3 health).ti,ab. or ((smartphone$ or smart phone$) adj3 app$).ti,ab. or smartphone/or mobile applications/or (secure adj3 message$).ti,ab. or wearable$.ti,ab. or (wearable$ adj3 device$).ti,ab. or (patient adj3 generate$ adj3 data).ti,ab. or (distance adj3 health).ti,ab. or (connect$ adj3 health).ti,ab. or (remote.ti,ab. and videoconferencing/) or (remote adj3 videoconferenc$).ti,ab. or telepharmacy.ti,ab. or (telemedicine/and (pharmacy service, hospital/or community pharmacy services/)) or teleradiology/or teleradiology.ti,ab. or ((radiology information systems/or technology, radiologic/) and telemedicine/) or telepathology/or telepathology.ti,ab. or (pathology/and telemedicine/) or in-home.ti,ab. or (wireless adj4 monitor$).ti,ab. or teleultraso$.ti,ab. or tele-ultraso$.ti,ab. or tele-radiology.ti,ab. or tele-pathology.ti,ab. or tele-pharmacy.ti,ab. or tele-medicine.ti,ab. or tele-health.ti,ab. or (virtual adj3 care).ti,ab. or (remote adj3 care).ti,ab. or (digital adj3 technolog$).ti,ab. or (portable adj3 device$).ti,ab. or ((phone or telephone or smartphone or smart phone) adj3 based).ti,ab. or (text adj3 messag$).ti,ab. or ((sms adj3 messag$) or short message service$).ti,ab. or (tablet adj3 app$).ti,ab. or (computers, handheld/and mobile applications/) or (patient adj3 engage$ adj3 app$).ti,ab. or (virtual adj3 consult$).ti,ab. or (virtual adj3 visit$).ti,ab. or (virtual adj3 health$).ti,ab.

Obstetrics/or gynecology/or womens health/or women’s health services/or exp contraceptive agents, female/or exp contraceptive devices, female/or exp maternal health services/or exp *pregnancy outcome/or exp "Female Urogenital Diseases and Pregnancy Complications"/or exp "diagnostic techniques, obstetrical and gynecological"/or exp gynecologic surgical procedures/or exp obstetric surgical procedures/

Family planning.mp. or Family Planning Services/or exp Contraception/or Contraception, postcoital/or Contraception, barrier/or Contraception, behavior/or contracept$.mp. or abortion.mp. or exp Intrauterine devices/or "birth control".mp. or Abortion, Induced/or Abortion, Legal/or (pregnancy adj3 terminat$).mp. or post-abortion.mp.

exp contraceptive agents, female/or exp contraceptive devices, female/

A data extraction form, developed by the lead author, included variables aligned with the key research questions. The variables included general information and evaluation (Table 1). Extracted data were collected in a table and analyzed by family planning service. Studies were reviewed and findings confirmed by authors. Discrepancies in study inclusion were resolved through discussion among the authors.

Table 1.

List of variables extracted for each family planning service

| General Information | Defined as publication year, geographic location, study type (quantitative or qualitative), telemedicine model, and family planning service |

| Evaluation | Study design, sample size, outcome, data collection methods, population studied, gestational age |

RESULTS

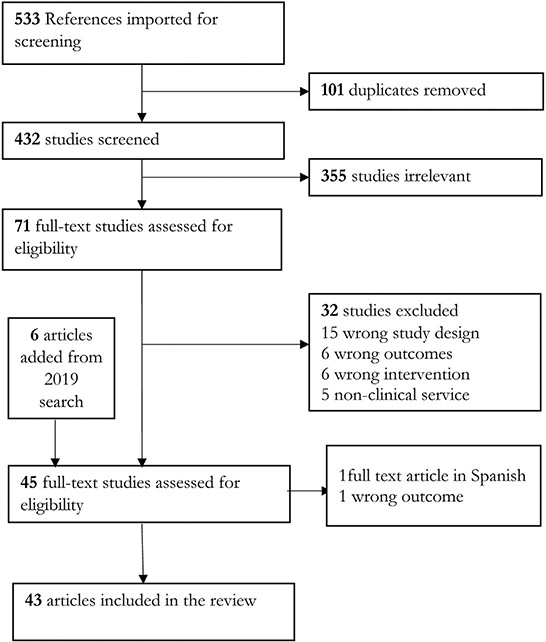

A total of 533 studies were eligible for initial review. After excluding duplicates, studies in languages other than English, commentaries, abstract-only publications, case reports/series, and studies that reviewed services other than family planning services, 43 studies were included in this scoping review; 14 studies on contraception, 20 studies on medication abortion, and 9 studies on medication abortion follow-up (Fig. 1). Publication years ranged from 2008 to 2019 and included telemedicine services in countries in the very high, high, and medium Human Development Index.11

Fig. 1.

Scoping literature review flow chart (modified PRISMA).

Contraception

Contraception studies included in this review examined technological interventions that could facilitate the initiation and use, adherence, continuation, and provision of a contraceptive method. The majority of studies in this review used mobile apps or text message reminders (n = 12). One study described a telephone intervention and another an online platform for oral contraceptive prescriptions. Studies on contraception were done in the last 10 years, between 2008 and 2019 and mapped to at least 1 contraception outcome. All studies in this review used quantitative methods to assess a range of indicators (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of studies on telemedicine for contraception

| Author, Year, Country | Methods | Objective (s) | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gilliam et al,12 2014, United States | RCT of patients, under 30 y, in a Title X clinic (28 intervention and 24 standard care) | Assess the impact of an iOS waiting room app for contraceptive counseling on contraceptive knowledge and uptake | Significantly higher knowledge of contraceptive effectiveness among app users Significantly higher interest in the implant method among app users after the intervention (7.1%–32.1%; P = .02) No significant difference in LARC selection between arms (25% vs 20.8%; P = .72) Acceptability of app use among staff |

| Smith et al,13 2015, Cambodia | RCT of abortion patients, ≥18 y (249 mobile phone users; 251 standard care) | Assess the effect of a mobile phone-based intervention on postabortion contraception use at 4 and 12 mo | Significantly higher proportion of women in intervention group report effective contraception use at 4 mo (64% vs 46%) A significantly higher proportion of women in intervention group report using a long-acting contraceptive method at 4 and 12 mo (29% vs 9% and 25% vs 12%, respectively) |

| Stidham Hall et al,4 2013, United States | RCT of women ages 13–25 y (337 routine care; 346 routine care plus 6 months of daily educational text messages) | Assess the effect of text message reminders on young women’s oral contraceptive knowledge | Oral contraceptive knowledge improved over time for all women Mean knowledge scores were significantly greater among women in the intervention group (intervention [25.5] vs control group [23.7]) |

| Chernick et al,14 2017, United States | RCT of adolescent (14–19 y) emergency department patients receiving texts for 3 months (50 per arm) | Assess the effect of a text messaging intervention on initiation of contraception | Mobile text messaging intervention was acceptable to users Contraceptive initiation limited; initiated in 12% of adolescents in intervention group vs 22.4% in the control group |

| Bull et al,15 2016, United States | RCT of 8 Boys & Girls Clubs into treatment and control sites (youth, 14–18 y: 317 intervention; 315 standard program) | Assess whether the addition of a text messaging intervention increased the effects of an adolescent pregnancy prevention program | No significant differences in condom and contraceptive use, access to care, or pregnancy prevention Hispanic participants in the intervention condition had significantly fewer pregnancies at follow-up (1.79%) than did those in the control group (6.72%) |

| McCarthy et al,16 2018, Tajikistan | RCT of men and women aged 16–24 y (275 intervention arm, 298 control arm) | Assess the effect of a text messaging intervention on acceptability of effective contraceptive methods and contraceptive use at 4 mo and during the study, service uptake, induced abortion, and unintended pregnancy | There was no evidence of a difference in acceptability between groups. Similarly there was no significant difference in contraceptive use, service uptake, or other secondary or process outcomes. Acceptability of effective contraception significantly increased from baseline to follow-up (2%–65%) |

| Buchanan et al,17 2018, United States | Retrospective cohort study of urban adolescent and young adult women (13–21 y). Sixty-seven participants using DMPA at baseline, followed up 20 mo after the intervention | Assess the long term impact of a 9-mo text message intervention on adherence to effective contraceptive methods | Participants in the intervention were close to 4 times more likely to continue using DMPA or a more efficacious method such as implant or intrauterine device at 20 mo after the intervention (odds ratio, 3.65; 95% confidence interval, 1.26–10.08; P = .015) |

| Castano et al,18 2012, United States | RCT of young women (13–25 y) choosing OCPs at an urban family planning health center (337 routine care; 346 routine care and daily educational text messages) | Assess whether text messaging intervention affects oral contraceptive pill continuation at 6 mo | Significantly higher proportion of OCP users in the intervention group were still users at 6 mo (64% vs 54%) Continuation on the method lessened once the intervention ended |

| Trent et al,19 2015, United States | RCT of urban adolescent and young adult women (13–21 y) using DMPA (50 per arm) | Determine feasibility and acceptability of text messaging intervention | Text messaging intervention feasible and acceptable as a clinical support tool for urban young women Preliminary evidence for text message reminders improving clinic attendance for first 2 family planning visits. Return for first and second cycles were higher for youth in the intervention group vs those in the control |

| Hou et al,20 2010, United States | RCT of young women, 18–30 y). Pill taking was tracked for 3 mo by an electronic monitoring device with wireless data collection (41 per arm) | Assess whether daily text message reminders can increase oral contraceptive pill adherence | Oral contraceptive pill adherence was not improved with daily text message reminders; no significant difference in mean number of missed pills per cycle between groups |

| Tsur et al,21 2008, United States | RCT of women (16–45 y) using isotretinoin, a treatment for severe acne (50 intervention, 58 control), follow-up at 3 mo | Assess the impact of a text message intervention on increasing contraceptive use | No significant difference in contraceptive use between groups at follow-up (50% intervention and 40% control group were using a contraceptive method at 3 mo) |

| Thiel et al,22 2017, United States | Quasiexperimental study with 365 matched pairs (women 14 y and older) | Determine whether Bedsider text message and e-mail reminders increase family planning contraceptive continuation and appointment rates | No significant difference in timely return for contraceptive injections between groups No difference in contraceptive coverage between groups |

| Wilkinson et al,23 2017, United States | RCT of women, 13–21 y in an urban adolescent clinic | Assess the feasibility of using text messages to remind adolescents to fulfill their advance emergency contraception prescriptions | Study not powered to assess differences across randomized groups; however, preliminary results show prescription fulfilment following text message reminders. The effect seemed to be additive after each text reminder |

| Zuniga et al,24 2018, United States | Assessment of 9 online platforms that prescribe hormonal contraceptives across various states in the United States | Compare prescribing processes and policies of online platforms in the United States and assess whether online prescribers are providing evidence-based care | Variation in the all parts of the prescribing process (how the patient provides information, who reviews patient information to decide eligibility, and screening for contraindications) across platforms Online prescription platforms serve limited geographic areas Variation in the range of contraceptive methods offered, fees for services, and policies around age restrictions for contraceptives |

Abbreviations: DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; LARC, long-acting reversible contraceptive; OCP, oral contraceptive pill.

Initiation and use

Two RCTs piloted programs to increase contraceptive knowledge and facilitate long-acting reversible contraceptive uptake.12,13 Smith and colleagues’ study,13 based in Cambodia, targeted women seeking safe abortion services. Women were randomized to either a 3-month mobile phone-based intervention—where they received 6 automated, interactive voice messages with counselor phone support (depending on their response to the message) or to a control group receiving standard care, postabortion family planning counseling at the clinic, the offer of a follow-up appointment at the clinic, and contact information for the clinic inclusive of a hotline number operated by the counsellors. Women were contacted at 4 and 12 months to determine if they had initiated and continued use of a contraceptive method, respectively. In Gilliam and colleagues’ study,12 women were randomized to either receive the app and standard of care or just standard of care (described as contraceptive counseling by a clinic counselor followed by a visit with a nurse practitioner to receive [or be prescribed] the contraceptive method of their choice). Those randomized to the intervention arm received a tablet computer with the contraception information app and instructions to use the app for up to 15 minutes. Authors reported a significant increase in contraceptive knowledge among app users,12 increased interest in the implant as a contraceptive method,12 and an increase in short-term use of any effective contraceptive method and the use of a long-acting contraceptive method in the longer term.13

Two RCTs evaluated the use of a text messaging intervention to increase oral contraceptive knowledge and contraceptive use among young women, ages 13 to 25.4,14 Educational texts were sent daily for 314 and 6 months.4 The text message intervention was not shown to increase contraceptive initiation; however, modest improvements were observed in oral contraceptive knowledge over time.4 Two RCTs of text message interventions with young people, 14 to 18 years old, in the United States15 and 16 to 24 in Tajikistan16 were included in this review. Both studies showed no impact on condom15 and contraceptive use,15,16 or in the acceptability of effective contraception.16

Continuation

A retrospective cohort study17 and 2 RCTs18,19 show a beneficial effect of daily interactive text message reminders on oral contraceptive and injectable contraceptive continuation. Participants were followed over time for a period of 618 and 20 months.17 Results from the larger RCT showed that the intervention group had significantly higher continuation rates with no difference by age, history of oral contraceptive use, or race.18 Findings from the injectable contraceptive studies found that intervention participants returned sooner after a scheduled appointment for the first cycle19 and were 3.65 times more likely to continue use of injectables or a more efficacious method at the 20-month postintervention evaluation.17

Adherence

Two RCTs20,21 and 1 quasiexperimental study22 aimed to understand the impact of daily text message/email reminders on oral contraceptive pill adherence. Results showed no effect of daily text message/email reminders on missed pills as assessed by electronic medication monitoring,20 no effect on contraceptive use among women using isotretinoin,21 and no effect on timely return for contraceptive refills and injections.22 Results from a randomized pilot study of young women who received text messages as a reminder to fulfill their advance emergency contraceptive prescriptions showed a potential temporal effect that seemed to be additive after each text reminder.23

Provision

Finally, Zuniga and colleagues24 compared the prescribing processes and policies of online platforms that prescribe hormonal contraceptives to patients in the United States and assessed whether these platforms were providing evidence-based care based on the 2016 US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use.25 To use these platforms, a patient provides relevant information to a health care provider through a remote web portal or sometimes through a synchronous video interaction. The provider reviews the health information, prescribes an appropriate contraceptive method, and sends the contraceptive in the mail or sends a prescription to the patient’s pharmacy. The platforms varied in the range of methods offered, fees for services, policies related to age restrictions, and prescribing processes; however, in general the online platforms appropriately screened potential users according to the US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use.

Telemedicine Provision of Medication Abortion

Medication abortion involves the use of mifepristone together with misoprostol or misoprostol alone to terminate a pregnancy. Telemedicine for the provision of medication abortion, defined as the use of technology to provide or facilitate the safe use of abortion pills, has been in use since 2005.26 Its use has primarily been in settings where access to abortion is legally restricted or because in-person administration of mifepristone is required. Studies included in this review fall into 2 broad categories: telemedicine as part of the health care delivery system and telemedicine as a means to support or facilitate the use of medication abortion—via user-centered gestational age dating, guidance for at-home use of the medications, or reducing wait times. Studies used both qualitative and quantitative methods, and about half (n = 11) analyzed data retrospectively. Finally, all studies on the use of telemedicine to deliver medication abortion used the combined mifepristone-misoprostol regimen (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of studies on telemedicine for medication abortion and medication abortion follow-up

| Author, Year, Country | Methods | Objectives | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aiken et al,27 2017, Republic of Ireland and northern Ireland | Retrospective, population based analysis of 1000 women (<20–≥45 y) who self-sourced medical abortion (up to 9 wk gestation) during a 3-year period | Assess the safety and effectiveness of medical abortion through online provision | Overall, 95% reported successful termination of pregnancy without surgical intervention. Eighty-seven women reported seeking medical attention based on symptoms of the medical abortion. No deaths were reported. |

| Gomperts et al,28 2012, multi-country | Retrospective study of 2320 women (16–49 y) who self-sourced medical abortion during a 1-year period | Assess surgical intervention rates across regions for women getting a medical abortion through online provision | There are regional differences in rates of surgical intervention after a medical abortion through online provision; high rates were found in Eastern Europe (14.8%), Latin America (14.4%), and Asia/Oceania (11%). Lower rates were found in Western Europe (5.8%), the Middle East (4.7%), and Africa (6.1%). Clinical practice and guidelines on incomplete abortion rather than complications may explain observed differences. Rate of surgical intervention increased with gestational age. Surgical intervention influenced women’s views on the acceptability of the telemedicine provision model. |

| Gomperts et al,29 2014, Brazil | Retrospective study of 370 women (16–49 y) of varying gestational ages (<9 wk to >13 wk) during a year | Assess the safety and effectiveness of medical abortion through online provision | Medical abortion through online provision is effective across gestational ages. Although ongoing pregnancy increases with increasing gestational ages (1.9% for pregnancies at 9 wk, 1.4% for pregnancies 10–12 wk, and 6.9% with pregnancies of 13 wk or more), the difference is nonsignificant. Significant difference in surgical intervention rates (19.3% at <9 wk, 15.5% at 11–12 wk, and 44.8% at >13 wk). |

| Gomperts et al,30 2008, multi-country | Retrospective study of 484 women (15–46 y) ≤9 wk gestation from April to December 2006 | Assess the effectiveness and acceptability of medical abortion through online provision | Most (95%) women study found online provision of medical abortion acceptable. <2% of women reported a continuing pregnancy. A 6.8% curettage/vacuum aspiration rate for incomplete termination of pregnancy observed. |

| Les et al,31 2017, Hungary | Retrospective study of 136 women (≤19–≥41 y) over a 5-year period | Assess the safety and acceptability of medical abortion through online provision | Of the 59 women who had a medical abortion, 5 (8.5%) had a surgical intervention. All women who completed the follow-up survey found online provision of medical abortion acceptable. |

| Hyland et al,32 2018, Australia | Retrospective study of 965 women (14–49 y) <8 wk gestation who received services between June 2015 and December 2016 | Assess the safety, effectiveness, and acceptability of at-home telemedicine for medication abortion | Nearly all women (97%) indicate the at-home-telemedicine model was acceptable. At-home telemedicine model for medication abortion is effective; 96% of women who had a medical abortion were able to terminate the pregnancy without surgical intervention and 95% had no face-to-face clinical encounter after the medication abortion. |

| Raymond et al,33 2019, United States | Prospective study of 248 women (15–45 y) who received medication abortion packages, across 5 states, from May 2016 and December 2018 Women completing medication abortion using this model were ≤10 wk gestation |

Assess the safety, effectiveness, feasibility, and acceptability of at-home telemedicine for medication abortion | 64% of women who received medication abortion packages reported being satisfied with the service. Among women who provided abortion outcomes, 93% reported a complete abortion without surgical intervention. Among women who provided follow-up data, reports of clinically adverse events was low: <1% reported hospitalization or excessive bleeding. But 12% had an unscheduled clinical encounter, 50% of which resulted in no treatment. |

| Endler et al,34 2019, Poland | Retrospective population-based analysis of 615 women (16–56 y) from June to December 2016 | Assess the safety and acceptability of online provision of medical abortion | Medical abortion through online provision at >9 wk of gestation is associated with higher risk of same-day or day after clinical visits for concerns related to the procedure (11.7% for 9–11 wk and 22.5% for >11–14 wk). Self-reported rates of heavy bleeding, low satisfaction, or unmet expectations with medical abortion do not increase with gestational age. |

| Wiebe,35 2014, Canada | Retrospective chart review of women who completed a medical abortion from May 2012 and May 2013 | To pilot and assess feasibility of an at-home telemedicine model for medical abortion | Telemedicine seems to be feasible in this geographic setting. In the launch year, 11 women had a medical abortion; 8 completed with no intervention, only 1 required surgical intervention. |

| Aiken et al,42 2017, Republic of Ireland | Retrospective, population based analysis of 5650 women (<20–≥45 y) who self-sourced medical abortion during a 5 year period | Assess the characteristics and experience of women getting a medical abortion through online provision | High levels of satisfaction with online provision of medical abortion; 98% would recommend it to others in a similar situation and 97% felt they made the right choice. Women report feeling serious mental stress owing to the pregnancy and an inability to travel abroad to access abortion services. 70% reported feeling relieved right after completing the medical abortion. |

| Grossman & Grindlay36 2017, United States | Retrospective cohort study of 8765 telemedicine and 10,405 in-person medical abortions performed over a 7-year period; women ≤9 wk gestation | Assess the safety of clinic-to-clinic telemedicine provision of medical abortion (as compared with in person) | Adverse events are rare with medical abortion; no deaths reported. <1% of telemedicine and in-person patients had any adverse event. |

| Grossman et al,37 2011, United States | Prospective cohort study of 449 women (18–45 y) who obtained medical abortion through an in-person visit or via clinic-to-clinic telemedicine over a year (2008–2009) | Assess the safety and acceptability of a clinic-to-clinic telemedicine model for medical abortion | Clinic-to-clinic telemedicine for medical abortion is safe; 99% abortion completion for telemedicine patients and 97% for in-person patients. No significant difference in prevalence of adverse events reported during the study period among telemedicine patients compared with in-person patients/ Ninety-one percent of participants were satisfied with their abortion. |

| Kohn et al,38 2019, United States | Retrospective cohort of 738 telemedicine and 5214 in-person medical abortions performed during a year (2017–2018); gestational age of women (≤19–≥40 y) was ≤7 wk | Assess the safety and effectiveness of clinic-to-clinic telemedicine provision of medical abortion (as compared with in-person) | Adverse events are rare with medical abortion; no deaths reported. <1% of telemedicine and in- person patients had an adverse event. Ongoing pregnancy (0.5% vs 1.8%) and aspiration procedures (1.4% vs 4.5%) were less common among telemedicine patients. |

| Grindlay et al,39 2013, United States | Qualitative study of providers and patients (<25 y) in Iowa (25 telemedicine patients, 5 in-person patients, and 15 clinic staff) | Assess acceptability of clinic-to-clinic telemedicine model | Telemedicine highly acceptable to patients and providers. Patients were positive or indifferent about having a conversation in person with the doctor. Several benefits of telemedicine were cited, including decreased travel for patients and providers and more availability of locations and appointment times in comparison with in-person service. |

| Grindlay & Grossman,40 2017, United States | Qualitative study of providers in Alaska (8 providers and staff) | Assess acceptability and impact of clinic-to-clinic telemedicine model on clinic | Integration of clinic-to-clinic telemedicine into standard practice is feasible; integrating new technology into clinic operations was easy, minimal impact on clinic flow, same overall processes as in person. Increases ability to provide patient-centered care; participants able to be seen sooner, closer to home, and have more options in abortion procedure type. |

| Grossman et al,3 2013, United States | Impact evaluation to capture changes in access (distance from patient residential zip code to clinic and closest clinic providing surgical abortion) for all abortion encounters (women 15–44 y) (n = 17,956) 2 y before and after the introduction of a clinic-to-clinic telemedicine model | Assess the effect of a clinic-to-clinic telemedicine model for medical abortion on service delivery in a clinic system in Iowa | Clinic patients had increased odds of obtaining both medical abortion and abortion before 13 wks gestation after telemedicine was introduced, with adjustment for other factors. Women living >50 miles from the nearest clinic offering surgical abortion were more likely to obtain an abortion after telemedicine introduction. |

| Momberg et al,43 2016, South Africa | Observational study of 78 women (18–42 y) seeking an abortion at 2 health care clinics | Assess acceptability of and ability to use an online gestational age calculator to assess eligibility for medical abortion in a nonclinical setting | The online gestational age calculator was considered easy to use, accurate, and helpful by most (86%–94%) participants. On average women overestimated their gestational age by 0.5 d (standard deviation, 14.5); not clinically significant. |

| Constant et al,44 2014, South Africa | RCT of women (>18 y) undergoing early medical abortion (standard of care only, n = 235; standard of care + messaging, n = 234) | Assess the impact of automated text messages on anxiety and emotional discomfort, as well as feelings of preparedness among medical abortion seekers | Automated text messages significantly reduced emotional stress and anxiety between baseline and follow-up. Women in the intervention group reported feeling more prepared for bleeding, pain, and side effects associated with medical abortion. Women in the intervention group found text messages highly acceptable and would recommend the messages to a friend. |

| de Tolly & Constant,45 2014, South Africa | RCT of women (>18 y) undergoing early medical abortion (standard of care only, n = 235; standard of care + messaging, n = 234 | Assess the feasibility and efficacy of automated text messages | Text messages were highly acceptable and considered a valid form of coaching through the medical abortion process. Women were able to complete a self-assessment questionnaire via mobile phone if given a short training session. |

| Ehrenreich et al,47 2019, United States | Qualitative study with 18 women (19–40 y) who used telemedicine to attend state mandated information visits | Assess patient experience using telemedicine to attend state-mandated information visits | Telemedicine is acceptable as a mode for attending state mandated information visits; technology was easy to use, nurse was attentive to emotions over video. Telemedicine alleviates cost, travel, and time burdens associated with attending 2 in-person visits. |

| Bracken et al,48 2014, United Kingdom | RCT of 999 women (≥16 y) getting remote follow-up (pregnancy test, standardized symptom survey administered via online, text message, or telephone) or to clinic based follow-up with ultrasound at 1 wk; women were ≤63 d of gestation | Assess the effectiveness and feasibility of remote communication technologies to increase follow-up after early medical abortion | Follow-up rate did not differ by group (clinic-based, 73% vs remote, 69%; risk ratio, 1.0; 95% confidence interval, 0.9–1.2). Most women found this follow-up method acceptable, although there was a preference for follow-up by phone or text message in the future. Women in the clinic-based group were 1.9 times more likely to receive some type of additional medical abortion-related care than women in the remote group (risk ratio, 1.875; 95% confidence interval, 1.15–3.06). |

| Ngoc et al,49 2014, Vietnam | RCT of 1433 women (15–46 y) seeking early medical abortion at 4 hospitals getting clinic or phone follow-up; women were ≤63 d of gestation | Assess the effectiveness and feasibility of phone follow-up after early medical abortion | Phone follow-up was highly effective in screening for ongoing pregnancy with a sensitivity and specificity of 92.8% and 90.6%, respectively. The rate of ongoing pregnancy was not significantly different between the 2 groups. 85% of women in the phone group did not need an additional clinic visit. |

| Platais et al,50 2015, Moldova and Uzbekistan | RCT of 2400 women (16–49 y) receiving a medical abortion at ≤63 d gestation (n = 1200 telephone; n = 1200 for clinic follow-up) | Assess the feasibility and acceptability of telephone follow-up combined with a semiquantitative pregnancy test and standard checklist for medical abortion follow-up | Majority of women were successfully contacted by phone (98%). Ongoing pregnancy rate was similar in both groups (0.4%–0.6%), and the semiquantitative pregnancy test identified all ongoing pregnancies in the phone follow-up group. 7% of women in the telephone arm had a clinic follow-up. Women in the phone group found the test and checklist easy to use, and most (76.1%) preferred phone follow-up in the future. |

| Chen et al,51 2016, United States | Retrospective chart review of medical abortions provided over a 3-year period (105 office follow-up; 71 telephone follow-up); women were between 16 and 45 y | Comparing lost to follow-up, abortion completion, and staff effort for medical abortion follow-up by office visit or telephone | Proportion lost to follow-up was similar in both groups. Abortion completion was similar between both groups (94.3% office follow-up vs 92.5% telephone follow-up). Staff made >1 phone call to 43.9% and 69.4% of women at weeks 1 and 4, respectively, and rescheduled 15% of office follow-up visits. |

| Michie & Cameron,52 2014, United Kingdom | A retrospective database review of 1084 women (16–46 y) at a hospital abortion service who had a medical abortion (≤9 wk) | Assess the success of telephone follow-up plus a self-performed LSUP test, in screening for ongoing pregnancies | 656 women were successfully contacted, of which 87% screened negative for ongoing pregnancies and 13% screened positive. Only 3 ongoing pregnancies occurred in the 13% of women who screened positive. The sensitivity of telephone follow-up with LSUP to detect ongoing pregnancy was 100% and the specificity was 88%. The negative predictive value was 100%, and the positive predictive value, 3.6%. |

| Cameron et al,53 2012, Scotland | Retrospective chart review of 476 women (16–46 y) who had telephone follow-up between May 2010 and February 2011 and a prospective study of 75 women after a medical abortion | Assess abortion completion and patient acceptability of telephone follow-up for medical abortion | Telephone follow-up was acceptable; with 100% of surveyed women reporting they would recommend to a friend. 472 women were successfully contacted, of which 60 screened positive for ongoing pregnancy, 3 of whom had ongoing pregnancies, and 1 woman falsely screened negative. The sensitivity of the telephone follow-up was 75%, and specificity was 86%. The negative predictive value was 99.7%, and positive predictive value was 5%. |

| McKay & Rutherford,54 2013, United Kingdom | Prospective study of 220 women (<63 d gestation) whose medical abortions were performed at home from September 2009 to October 2010 | Assess the success and acceptability of clinical telephone follow-up for medical abortion | The majority of women were successfully contacted. 3.6% of all medical abortions with clinical telephone follow-up required surgical intervention. Among survey respondents, acceptability of clinical telephone follow-up was high with 95% feeling like they felt prepared for side effects of medical abortion. |

| Anger et al,55 2019, Mexico | Prospective study of 163 women (14–41 y) who had a medical abortion up to 70 d gestation | Feasibility of an interactive voice response call-in system and at home MLPT for medical abortion follow-up | 10 women who reported MLPT results to the interactive voice response system needed clinical evaluation. Ongoing pregnancy was ruled out for 93% of women who reported MLPT results. Among women who had medical abortions after 63 d, MPLT accurately ruled out ongoing pregnancy for 91%. |

| Perriera et al,56 2010, United States | Prospective study of 139 women (18–41 y) up to 63 d of gestation who received a medical abortion | Assess the feasibility of telephone follow-up combined with high sensitivity urine pregnancy test as a method of follow-up to medical abortion | 135 women completed follow-up. 26 women were evaluated for a positive or inconclusive pregnancy test. None had a gestational sac or continuing pregnancy. There were 4 continuing pregnancies, 1 before phone call, 2 at a follow-up visit after phone call, and 1 at an interim visit before phone call. The sensitivity of telephone follow-up was 100%, specificity of 86.3%. The negative predictive value was 100% and positive predictive value was 18.2%. |

Abbreviations: LSUP, low-sensitivity urine pregnancy; MLPT, multilevel pregnancy test.

Telemedicine as part of the health care delivery system

Direct-to-patient telemedicine models involve the use of telecommunications technology to provide access to the service outside of a clinic setting. Studies that met inclusion criteria featured synchronous and asynchronous models. Patients consult with a provider via a telephone or videoconference. If eligible, the patient is mailed the medications or a prescription is sent to a local pharmacy. After taking the medications, the patient gets follow-up tests and a follow-up consultation with a provider by telephone or videoconference to assess abortion completeness. In contexts where abortion is illegal or highly restricted, patients may access abortion pills through an online platform. Patients complete a consultation form which includes information on pregnancy duration—based on last menstrual period or ultrasound examination—age, pregnancy history, medication history, contraceptive use, and any diseases or allergies. After a review of the medical information and if the clinical criteria are met, the patient is sent a package with the medications along with instructions on its use and support via a helpdesk during and after the abortion process.

Ten studies assessed the safety, effectiveness, and acceptability/satisfaction of direct-to-patient telemedicine models.27-35 Studies were conducted in very high, high, and medium Human Development Index countries. Seven of the 10 studies assessed the online platform provision of medication abortion pills. Sample sizes for the studies ranged from 11 to 1100. Assessments of effectiveness, safety, and acceptability and satisfaction are captured solely among patients of the telemedicine model. Furthermore, acceptability was only measured from the perspective of the patient. Finally, the direct-to-patient telemedicine model was reported as feasible in a few studies, however, there were no explicit feasibility studies conducted.33-35

In the clinic-to-clinic telemedicine model, a patient seeking medication abortion meets with staff in a clinic to obtain a medical history and assess gestational age by ultrasound examination and vital signs. Once complete, the patient meets with a clinician off site via a secure teleconference platform to review their medical history and clinical evaluation, confirm eligibility for the service, and discuss the treatment. If eligible, the patient is provided with the medications and given instructions about taking the misoprostol. Guidance around what to expect during the abortion procedure, warning signs, and a follow-up plan to confirm medication abortion completion is also provided.

Five studies (all conducted in the United States) assessed the safety, effectiveness, and acceptability and satisfaction of clinic-to-clinic models.36-40 Studies that focused on safety and effectiveness as their primary outcomes used a comparison group design. Three studies were prospective, and the remainder were retrospective reviews. The 2 qualitative studies included in this review examined the experience of patients and providers with the clinic-to-clinic telemedicine model—both the acceptability of the model as well as the impact on services. One study evaluated changes in service delivery statistics in the 2-year period before and after telemedicine was introduced in the clinic system.3

Safety and Effectiveness

In 2019, Endler and colleagues,41 conducted a systematic review of telemedicine for medication abortion (direct-to-patient and clinic-to-clinic models). This review includes several of the articles in our study27-33,36,37,39,40,42 and concludes that both the clinic-to-clinic and direct-to-patient models are effective and safe. Abortion completion (defined as lack of surgical intervention following the medication abortion), ranged from 98.1% to 100.0% for pregnancies less than 10 weeks gestation age. For direct-to-patient models, where abortion completion was assessed via self-assessment, abortion completion ranged from 76.9% to 96.4%.27-34 Rates of surgical evacuation after abortion ranged from 0.9% to 19.3%, with 1 study reporting that the higher rate was reflective of clinical practices and guidelines related to incomplete abortion within the geographic context, with a bias toward surgery for complications that may not justify the intervention.30 The proportion who reported a continuing pregnancy after a medication abortion seemed to increase with gestational ages greater than 10 weeks. Reports from 1 study show continuing pregnancy rates ranging from 1.4% at 10 to 12 weeks to 6.9% at 13 weeks or more.29 The proportion requiring surgical evacuation increased with gestational age, with 1 study reporting an incidence of 44.8% among participants at more than 13 weeks gestation.29 Three studies in the systematic review reported on the proportion of women with clinically significant adverse events, defined as death, hospitalization, surgery, blood transfusion, or emergency department visit where treatment was given.27,32,36 All studies assessed safety among women using medication abortion at less than 10 weeks gestation. Proportion of patients requiring blood transfusion were less than 1%, whereas the proportions of patients requiring hospital admission ranged from 0.07% to 2.80%.32,36 One study compared safety-related outcomes between women having a medication abortion through telemedicine versus in person at a clinic in Iowa. This retrospective cohort study, with close to 20,000 women over a 7-year period, showed that less than 1% of patients in both the telemedicine and in-person clinic models experienced a clinically adverse event.36 No deaths were reported in any of the studies. The study concluded that the clinic-to-clinic telemedicine model was noninferior to in-person provision of medication abortion with regard to safety.

Three studies released in 2019 support the findings of this systematic review.33,34,38 A retrospective cohort study of the clinic-to-clinic model with women presenting at 26 health centers across 4 states (Alaska, Idaho, Nevada, and Washington), found that the proportions of ongoing pregnancy and aspiration procedures among telemedicine and in-person patients were small, less than 2% for ongoing pregnancies and 5% for aspiration procedures.38 Results from the direct-to-patient models, which included only patients less than 10 weeks gestation, reported that 93%33 to 97%34 had a complete abortion. Among women having a medication abortion from 11 to 14 weeks gestation, the proportion of patients requiring hospital admission for concerns related to the treatment was 22.5%.34

Acceptability/ Satisfaction

Four of the 10 studies of direct-to-patient telemedicine assessed satisfaction and acceptability.32-34,42 Acceptability was most often captured through 2 questions: whether the patient would recommend the service to others in a similar situation and overall satisfaction with the service. Less commonly asked of patients is whether they felt the service was the right personal choice for them42 or valued aspects of the service.33 Across all studies, acceptability of the telemedicine model was high.

Findings on the acceptability of the clinic-to-clinic telemedicine model comes from 1 prospective study37 and 2 qualitative studies.39,40 Results of the prospective study suggest that the majority of patients were satisfied with their abortion and that telemedicine patients were more likely to recommend the service to a friend as compared with in-person patients. That said, about one-quarter of telemedicine patients indicated that they would have preferred to be in the same room as the provider if that had been possible. Younger, nulliparous, and patients with less than a grade 12 education were more likely to report a preference for being in the same room as the provider. Qualitative findings on acceptability from the patient and provider perspective align with quantitative findings. With regard to impact on the clinic, findings from the qualitative studies noted several benefits of the clinic-to-clinic model, including an increase in the number of appointment days and times they could offer to patients, greater availability of locations, and decreased travel times for patients and providers.

Access

Last, Grossman and colleagues3 evaluated changes in service delivery statistics of 1 clinic system in Iowa following the implementation of a clinic-to-clinic telemedicine model. The pre–post intervention study found that telemedicine was associated with an increase in the probability of a patient receiving a medication abortion and of undergoing a first trimester abortion, as well as a small decrease in travel distance to the clinic. These results suggest that telemedicine provision of medication abortion improves access to early abortion.

Facilitators for medication abortion

Four studies assessed the use of technology to support patients having a medication abortion. Three were conducted in South Africa. They examined an online self-assessment of gestational age43 and a mobile phone intervention to support patients through medication abortion.44,45 Studies on the mobile intervention were RCTs aimed at evaluating the acceptability, feasibility, and impact of receiving automated text messages on the symptoms to expect during a medication abortion. The mobile phones coached women through the medication abortion via automated text messages (medication reminder, symptoms, and warning signs) to assess abortion completion, and provide family planning information. The automated text messages were found to be highly acceptable with 98% of those randomized to receive them reporting that the messages helped them through the medication abortion and 99% stating that they would recommend the messages to a friend having the same procedure. Women in the intervention group also reported feeling more prepared for the bleeding and side effects associated with the medication abortion and that they experienced less emotional stress and a decrease in anxiety between baseline and follow-up. A pilot study of 78 women in 2 health centers explored the feasibility and acceptability of an online self-assessment tool for gestational age. They found that women overestimated their gestational age by 0.5 days when compared with ultrasound gestational age, a nonclinically significant difference.43

The final study examines the use of telemedicine for state-mandated abortion consent. In 27 states of the United States, patients seeking abortion are required to go through a state-mandated informed consent process and then wait a minimum amount of time before undergoing abortion, most commonly 24 hours.46 The Planned Parenthood affiliate in Utah, where patients must wait 72 hours, began offering informed consent visits by videoconference in 2015. A qualitative study found that this telemedicine model was feasible and acceptable to patients and helped to decrease the logistical and financial obstacles associated with the mandatory delay requirement.47

Remote Follow-Up After Medication Abortion

Studies of remote follow-up after medication abortion involved technology (text message, telephone, or online assessments) paired with a home pregnancy test. Three RCTs explored the efficacy and feasibility of using text, online completion of a symptom questionnaire, or telephone as compared with clinic-based follow-up to confirm abortion completion.48-50 Follow-up, as defined by rates of complications and ongoing pregnancy, did not differ by group. Three retrospective reviews51-53 and 3 prospective studies54-56 of women receiving telephone follow-up after a medication abortion, reported low rates of ongoing pregnancy (<8%). The sensitivity of telephone follow-up ranged from 75%53 to 100%56 and specificity from 86%53 to 88%.52 Importantly, all 9 studies were done with women at less than or equal to 70 days gestation.

Discussion

Findings from this scoping review suggest several factors that could facilitate the uptake of telemedicine for family planning into standard of practice. First, telemedicine has been effectively used in contraception, medication abortion careand follow-up, and in a mix of very high, high, and medium Human Development Index countries. Second, telemedicine models that use mobile phones with an app or text messaging intervention can be used to decrease emotional stress and help contraception and abortion patients to feel more supported. Third, findings show that telemedicine for medication abortion services is safe, effective, highly acceptable and feasible for patients and providers to integrate into care.

Although there are hundreds of apps that provide sexual and reproductive health information, evaluations of these apps have focused on accuracy and comprehensiveness of information and the features and functionality.57,58 Our review found no evaluations of sexual and reproductive health apps that assessed knowledge translation as it pertains to contraceptive use, continuation, or translation to better contraceptive counseling practices among family planning providers. The positive effects seen in the study by Gilliam and colleagues12 suggests that the pairing of an informational app with a provider visit may be better at initiating contraceptive use than having potential users’ review and process contraceptive information independently. Presently, evidence for improved initiation and continuation is limited and there is no existing evidence that patient prompts through apps, text messages, or emails lead to better adherence with contraceptive methods. Further, few sexual and reproductive health apps have been found to be accurate, to provide comprehensive contraceptive information, to be developed by reproductive health experts, to cite information from a credible public health source, or advocate for behavior change. These findings, in addition to the lack of regulation of these information apps, makes it difficult to know if and how to incorporate them into clinical practice.

In this review, we identified only 1 study that explored the quality of care provided through online contraception provision platforms. Although there was a wider array of evidence available for medication abortion (ie, safety, effectiveness, acceptability, access, support), the body of evidence was limited by the number of studies available, inclusion of a comparison group, use of convenience samples, use of self-report data, small sample sizes, and high loss to follow-up (for some studies, loss to follow-up was as high as 45%).30 None of the evaluations of direct-to-patient models included a control group, which is often not feasible in legally restricted settings. More research is needed to reinforce the evidence on medication abortion safety and effectiveness, especially for the direct-to-patient models.

To ensure further adoption of telemedicine into family planning care, a few barriers must be removed. Implementing telemedicine services may be challenging for clinics with limited funds for start-up costs, with low computer or eHealth literacy, and with inadequate connectivity and/or technology infrastructure. However, findings from a systematic review of the use of telemedicine in various medical specialties across 114 countries found that telemedicine could be successfully delivered in settings with limited bandwidth through asynchronous delivery models via email services or static websites.59 This simple and low-cost solution may be an initial adoption strategy as we work to bolster technology infrastructure and support across health clinics.

Telemedicine’s relative newness and variety of applications can also make reimbursement challenging. As an example, some insurance programs in the United States limit the types of providers and services that can be reimbursed for telemedicine or prioritize reimbursement for telemedicine services provided in rural or underserved areas versus urban areas.60 Finally, the adoption of telemedicine may be limited based on restrictions placed on the family planning service itself. In the United States, strict restrictions on dispensing mifepristone allows for only 1 telemedicine model for medication abortion, the clinic-to-clinic model,61 which is currently banned in 17 states.62 Other restrictions include increased requirements to ensure patient security and privacy.

There are a few limitations of this study. The scoping review was limited to telemedicine interventions that have been evaluated and peer reviewed. Therefore, this review may have failed to capture some telemedicine for family planning models or unpublished studies. Further, only English language studies were included in this review. Finally, this review does not incorporate a critical appraisal of the evidence on telemedicine for family planning.

SUMMARY

Telemedicine has the potential to increase access to and quality of use of family planning. In particular, text message reminder apps seem to increase contraceptive method continuation, and preliminary evidence suggests that mobile telemedicine platforms may safely screen potential users for contraceptive eligibility. More research is needed on telemedicine provision of contraception. Although the evidence base is solid for telemedicine provision of medication abortion, more research is needed in particular on direct-to-patient models of care.

KEY POINTS.

Text messaging may increase knowledge about contraception, but there is limited evidence about its effectiveness to increase uptake among nonusers.

Text messaging reminders improve continuation among oral contraceptive and injectable users.

One study indicates that telemedicine provision of contraception uses evidence-based criteria for assessing eligibility, but more research is needed on this model.

Telemedicine provision of medication abortion has been shown to be equally safe and effective as in-person provision, and some measures of satisfaction are higher with telemedicine.

Telemedicine provision of medication abortion improved access to early abortion in 1 study in Iowa.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

Dr D. Grossman has received consulting payments from Planned Parenthood Federation of America for work related to telemedicine for medication abortion.

REFERENCES

- 1.FP2020 Catalyzing Collaboration 2017-2018. Available at: http://progress.familyplanning2020.org/. Accessed July 10, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Family Planning Evidence brief: ensuring contraceptive security through effective supply chains. Available at: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/family_planning/contraceptive-security-supply-chains/en/. Accessed July 10, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grossman D, Grindlay K, Buchacker T, et al. Changes in service delivery patterns after introduction of telemedicine provision of medical abortion in Iowa. Am J Public Health 2013;103:73–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stidham Hall K, Westhoff CL, Castano PM. The impact of an educational text message intervention on young urban women’s knowledge of oral contraception. Contraception 2013;87(4):449–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. A health telematics policy in support of WHO’s Health-For-All strategy for global health development: report of the WHO group consultation on health telematics. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Odibo IN, Wendel PJ, Magann EF. Telemedicine in obstetrics. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2013;56(3):422–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magann EF, McKelvey SS, Hitt WC, et al. The use of telemedicine in obstetrics: a review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2011;66(3):170–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Long MC, Angtuaco T, Lowery C. Ultrasound in telemedicine its impact in high-risk obstetric health care delivery. Ultrasound Q 2014;30(3):167–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nudell J, Slade A, Jovanovič L, et al. Technology and pregnancy. Int J Clin Pract Suppl 2011;65(170):55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. Prisma extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169(7):467–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.United Nations Development Program. Human Development Index. Available at: http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-hdi. Accessed, July 10, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilliam ML, Martins SL, Bartlett E, et al. Development and testing of an iOS waiting room “app” for contraceptive counseling in a Title X family planning clinic. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;211:481.e1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith C, Ngo TD, Gold J, et al. Effect of a mobile phone-based intervention on post-abortion contraception: a randomized controlled trial in Cambodia. Bull World Health Organ 2015;93:842–850A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chernick LS, Stockwell MS, Wu M, et al. Texting to increase contraceptive initiation among adolescents in the emergency department. J Adolesc Health 2017;61(6):786–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bull S, Devine S, Schmiege S, et al. Text messaging, teen outreach program, and sexual health behavior: a cluster randomized trial. Am J Public Health 2016;106:S117–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCarthy O, Ahamed I, Kulaeva F, et al. A randomized controlled trial of an intervention delivered by mobile phone app instant messaging to increase acceptability of effective contraception among young people in Tajikistan. Reprod Health 2018;15(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchanan CRM, Tomaszewski K, Chung SE, et al. Why didn’t you text me? Post-study trends from the DepoText trial. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2018;57:82–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castano PM, Bynum JY, Andres R, et al. Effect of daily text messages on oral contraceptive continuation: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2012;119:14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trent M, Thompson C, Tomaszewski K. Text messaging support for urban adolescents and young adults using injectable contraception: outcomes of the DepoText pilot trial. J Adolesc Health 2015;57:100–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hou MY, Hurwitz S, Kavanagh E, et al. Using daily text-message reminders to improve adherence with oral contraceptives: a randomized controlled trial [published erratum appears in Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:1224]. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:633–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsur L, Kozer E, Berkovitch M. The effect of drug consultation center guidance on contraceptive use among women using isotretinoin: a randomized, controlled study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17:579–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thiel de Bocanegra H, Bradsberry M, Lewis C, et al. Do Bedsider family planning mobile text message and e-mail reminders increase kept appointments and contraceptive coverage? Womens Health Issues 2017;27:420–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilkinson TA, Berardi MR, Crocker EA, et al. Feasibility of using text message reminders to increase fulfilment of emergency contraception prescriptions by adolescents [letter]. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2017;43:79–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zuniga C, Grossman D, Harrell S, et al. Breaking down barriers to birth control access: an assessment of online platforms prescribing birth control in the USA. J Telemed Telecare 2018;0(0):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65:1–104, appendices C and D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grant R. The website providing abortion without borders. Available at: http://digg.com/2016/women-on-web. Accessed July 19 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aiken ARA, Digol I, Trussell J, et al. Self reported outcomes and adverse events after medical abortion through online telemedicine: population based study in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. BMJ 2017;357:j2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomperts R, Petow SA, Jelinska K, et al. Regional differences in surgical intervention following medical termination of pregnancy provided by telemedicine. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2012;91:226–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gomperts R, van der Vleuten K, Jelinska K, et al. Provision of medical abortion using telemedicine in Brazil. Contraception 2014;89:129–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gomperts RJ, Jelinska K, Davies S, et al. Using telemedicine for termination of pregnancy with mifepristone and misoprostol in settings where there is no access to safe services. BJOG 2008;115:1171–5 [discussion: 5–8]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Les K, Gomperts R, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Experiences of women living in Hungary seeking a medical abortion online. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2017;22:360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hyland P, Raymond E, Chong E. A direct-to-patient telemedicine abortion service in Australia: retrospective analysis of the first 18 months. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2018;58:335–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raymond E, Chong E, Winikoff B, et al. TelAbortion: evaluation of a direct to patient telemedicine abortion service in the United States. Contraception 2019;100(3):173–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Endler M, Beets L, Gemzell Danielsson K, et al. Safety and acceptability of medical abortion through telemedicine after 9 weeks of gestation: a population-based cohort study. BJOG 2019;126(5):609–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiebe ER. Use of telemedicine for providing medical abortion. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2014;124:177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grossman D, Grindlay K. Safety of medical abortion provided through telemedicine compared with in person. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:778–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grossman D, Grindlay K, Buchacker T, et al. Effectiveness and acceptability of medical abortion provided through telemedicine. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118:296–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kohn JE, Snow JL, Simons HR, et al. Medication Abortion provided through Telemedicine in Four U.S. States. Obstet Gynecol 2019;134(2):343–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grindlay K, Lane K, Grossman D. Women’s and providers’ experiences with medical abortion provided through telemedicine: a qualitative study. Womens Health Issues 2013;23:e117–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grindlay K, Grossman D. Telemedicine provision of medical abortion in Alaska: through the provider’s lens. J Telemed Telecare 2017;23:680–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Endler M, Lavelanet A, Cleeve A, et al. Telemedicine for medical abortion: a systematic review. BJOG 2019;126(9):1094–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aiken A, Gomperts R, Trussell J. Experiences and characteristics of women seeking and completing at-home medical termination of pregnancy through online telemedicine in Ireland and Northern Ireland: a population-based analysis. BJOG 2017;124:1208–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Momberg M, Harries J, Constant D. Self-assessment of eligibility for early medical abortion using m-Health to calculate gestational age in Cape Town, South Africa: a feasibility pilot study. Reprod Health 2016;13:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Constant D, de Tolly K, Harries J, et al. Mobile phone messages to provide support to women during the home phase of medical abortion in South Africa: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception 2014;90(3):226–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Tolly KM, Constant D. Integrating mobile phones into medical abortion provision: intervention development, use, and lessons learned from a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2014;2(1):e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guttmacher Institute. Counseling and Waiting periods for abortion. 2019. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/counseling-and-waiting-periods-abortion. Accessed: July 20, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ehrenreich K, Kaller S, Raifman S, et al. Women’s experiences using telemedicine to attend abortion information visits in Utah: a qualitative study. Womens Health Issues 2019;29(5):407–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bracken H, Lohr PA, Taylor J, et al. RU OK? The acceptability and feasibility of remote technologies for follow-up after early medical abortion. Contraception 2014;90:29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ngoc N, Bracken H, Blum J, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of phone follow-up after early medical abortion in Vietnam: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123(1):88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Platais I, Tsereteli T, Comendant R, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of phone follow-up with a semiquantitative urine pregnancy test after medical abortion in Moldova and Uzbekistan. Contraception 2015;91(2):178–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen M, Rounds K, Creinin M, et al. Comparing office and telephone follow-up after medical abortion. Contraception 2016;94:122–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Michie L, Cameron S. Simplified follow-up after early medical abortion: 12-month experience of a telephone call and self-performed low-sensitivity urine pregnancy test. Contraception 2014;84:440–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cameron S, Glasier A, Dewart H, et al. Telephone follow-up and self-performed urine pregnancy testing after early medical abortion: a service evaluation. Contraception 2012;86:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McKay RJ, Rutherford L. Women’s satisfaction with early home medical abortion with telephone follow-up: a questionnaire based study in the UK. J Obstet Gynaecol 2013;33(6):601–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anger H, Dabash R, Pena M, et al. Use of an at-home multilevel pregnancy test and an automated call-in system to follow-up the outcome of medical abortion. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2019;144:97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Perriera LK, Reeves MF, Chen BA, et al. Feasibility of telephone follow-up after medical abortion. Contraception 2010;81:143–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mangone ER, Lebrun V, Muessig KE. Mobile phone apps for the prevention of unintended pregnancy: a systematic review and content analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2016;4(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lunde B, Perry R, Sridhar A, et al. An evaluation of contraception education and health promotion applications for patients. Womens Health Issues 2017;27-1:29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.World Health Organization. Telemedicine: opportunities and developments in member states. Available at: https://www.who.int/goe/publications/goe_telemedicine_2010.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Center for Connected Health Policy. State telehealth laws and reimbursement Policies: a Comprehensive scan of the 50 States and the District of Columbia. Report. 2019. Available at: https://www.cchpca.org. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Raymond EG, Grossman D, Wiebe E, et al. Reaching women where they are: eliminating the initial in-person medical abortion visit. Contraception 2015; 92(3):190–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guttmacher Institute. Medication abortion, State Laws and Policies (as of May 2019). 2019. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/medication-abortion. Accessed July 20, 2019. [Google Scholar]