Abstract

HIV-related stigma is a major barrier to HIV testing and care engagement. Despite efforts to use mass media to address HIV-related stigma, their impact on reducing HIV-related stigma remains unclear. Thus, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of peer-reviewed publications quantitatively examining the impact of mass media exposure on HIV-related stigma reduction and published from January 1990 to December 2020. Of 388 articles found in the initial screening from scientific databases, 19 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review. Sixteen articles reported the quantitative effect of mass media exposure on HIV-related stigma and were included in the meta-analysis. Systematic review results showed considerable heterogeneity in studied populations with a few interventions and longitudinal studies. Results suggested a higher interest in utilizing mass media by health policymakers in developing countries with greater HIV prevalence to reduce HIV-related stigma. Meta-analysis results showed a modest impact of mass media use on HIV-related stigma reduction. Despite heterogeneity in the impact of mass media on HIV-related stigma, Egger’s regression test and funnel graph indicated no evidence for publication bias. Results demonstrated an increase in the impact of mass media on reducing HIV-related stigma over time and no correlation between the HIV prevalence in countries and the impact of mass media. In summary, mass media exposure has a modest and context-specific impact on HIV-related stigma reduction. More large-scale mass media interventions and studies addressing the impact of mass media on different forms of stigma are required to inform policies.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Stigma, Mass media, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Introduction

About four decades have passed since the first group of HIV-positive individuals were diagnosed among injection drug users and gay men [1]. From the beginning, HIV/AIDS has been associated with the “stigma” of a kind of perversion or immorality. Mass media stories and anecdotal accounts from the early 1980s reveal how people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWH)—as well as people who were merely suspected of being infected—were evicted from their homes, ousted out from their jobs, and being avoided by family and friends [2].

HIV-related stigma is a barrier to finding an effective response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic [3]. The Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) defines HIV stigma as a process in which individuals living with or associated with HIV/AIDS are devalued [4]. HIV stigma can negatively impact HIV preventive measures [5–7], decrease the access of PLWH to health services and social supports, and limit social interactions of PLWH [5, 8, 9]. The HIV-related stigma can be categorized based on how it manifests or how it affects individual health. HIV stigma can manifest at internal and external levels. Internal stigma is a kind of stigma that manifests at the intrapersonal level, such as feeling miserable or having shame and may result in a reluctance to seek help. External stigma is at the interpersonal level and is imposed by families, communities, and the healthcare system on PLWH [10].

Regarding the mechanisms that HIV stigma can affect individuals’ health, Earnshaw et al. [11] suggested three distinct mechanisms for HIV-related stigma, including anticipated, internalized, and enacted stigma resulting in different health outcomes. Anticipated stigma explains how one might expect PLWH to be abused and discriminated against based on their HIV-positive status. Anticipated stigma is predicted as the most influential HIV-related stigma in preventing individuals from adhering to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and attending healthcare appointments [11]. Internalized stigma points out being less valued or inferior to others due to having HIV/AIDS and may lead to mental health issues such as feelings of hopelessness and denial [12]. Internalized HIV-related stigma states acceptance and adoption of negative beliefs about having HIV in society and internalizing them. While some studies demonstrated the adverse impact of internalized HIV-related stigma on adherence to HIV treatment, others found mixed results for this relationship [13]. Finally, enacted stigma reflects the experiences of unfair treatment by others [14–18]. Enacted HIV stigma includes experiences of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination from others because of having HIV [11].

Given the importance of information, HIV knowledge, culture, and public attitudes in HIV stigma [11, 19–21], and the significant role of mass media in influencing these factors, mass media could have a high potential in reducing HIV-related stigma across various cultural settings. Mass media represents a diverse range of media technologies that get to a large audience via mass communication (e.g., radio, TV, film, video and audio recordings, blogs, internet, and print media like newspapers, magazines, brochures, and visual media like billboards, bus stops, etc.). To study the impact of mass media on HIV-related stigma, previous studies have deemed exposure to mass media (mass media use) as the mass media measure. Mass media exposure can include all media programs (general exposure) [22] or exposure to only HIV-related mass media content such as HIV-related media campaigns [23], programs providing HIV information [24] or TV series or stories related to HIV and PLWH [25]. While general exposure to mass media could be associated with higher socioeconomic status and elevate people's awareness and general health knowledge [26], exposure to HIV-related media content could provide essential information related to HIV/AIDS, promote healthy behaviors, and encourage condom use [25].

However, despite the potential benefits of both general and HIV-related mass media exposures, they do not always lead to positive outcomes. Mass media can have their own financial and political interests in stigmatization as it may attract more “eyeballs” in the attention economy (REF). Also, mass media may frame a group of people in a negative light due to their political interests leading to prejudice and discrimination against these people, like the example of stigma against Asians in the COVID-19 pandemic [27]. Moreover, HIV/AIDS is associated with social interaction difficulties and seclusion [1, 11] that may negatively affect the efficacy of mass media programs in reducing HIV-related stigma. Thus, mass media strategies are not as common as other strategies of health communication among vulnerable populations like PLWH.

While many studies have addressed the relationship between the use of mass media and HIV-related stigma in distinct contexts, due to the complexity of this interaction, little is known about how different contexts make mass media strategies for HIV stigma reduction more or less effective. The factors that could characterize a context include the form of mass media (TV, Radio, Newspaper, etc.), type of mass media strategy, type of dominant stigma (anticipated, internalized, and enacted), target country, HIV prevalence, target population (general or vulnerable individuals), and the time of exposure. These context characteristics could also influence mass media policies and the number and content of mass media products related to HIV and indirectly affect the effect of mass media use on HIV-related stigma reduction. In this study we explore how is the interaction between mass media exposure and HIV stigma in different studies (contexts). We conducted a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of the current published literature on the quantitative impact of mass media on HIV-related stigma reduction and discussed how changes in characteristics of the context may explain the results reported by various studies. The reviewed studies include studies that explore the impact of mass media exposure (general and HIV-specific contents) as well as some studies intended to remediate HIV stigma.

Methods

The current systematic review and meta-analysis on the impact of mass media on HIV-related stigma reduction were completed by following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyzes (PRISMA) guidelines [28].

Search Strategy

We conducted a comprehensive search through international indexing databases, including PubMed, Embase, Science Direct, ISI Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Scopus. We conducted the literature search using the keywords including “HIV”, “stigma”, “HIV-related stigma”, “prejudice”, “mass media”, “media exposure”, “communication exposure”, and “media use” in January 2021. The key string used for databases search was (“stigma” OR “HIV-related stigma” OR “prejudice”) AND (“HIV” or “HIV/AIDS”) AND (“mass media” OR “media” OR “media exposure” OR “media use”). The field was limited to “title/abstract”. In addition, to find more eligible studies, we searched the reference list of articles. We used reference management software (Mendeley) to organize and evaluate titles and abstracts as well as to identify duplicate studies. The inclusion criteria for systematic review were (1) primarily focusing on HIV-related stigma, (2) discussing the impact of mass media on HIV-related stigma, (3) Using quantitative or mixed-method approaches, and (4) published in peer-reviewed journals from January 1990 to December 2020. The exclusion criteria were (1) not in English, (2) commentary, letters to the editor or opinion pieces, and protocols, (3) primary focus on social media, and (4) qualitative studies. In the meta-analysis, we included studies that passed the inclusion criteria for systematic review as well as (5) reported quantitative data for the effect of mass media on HIV-related stigma.

Data Extraction

We organized the review using a data extraction form, including author name, title, year of publication, setting, aims, study design, sampling method, type of questionnaire administration, sample size, population, and outcome. Two researchers separately extracted the information of interest from the studies. Cases that have not been agreed upon (12% of cases) were referred to another researcher. All three researchers discussed disagreement cases in a meeting by double-checking extracting strategies and potential reasons for disagreements. In this study, consensus (100% agreement) on all items was obtained through further inspection and discussion by all three researchers. In the first step in selecting materials, we removed articles with unrelated titles. Next, we reviewed the abstracts and texts of the articles to make sure that we only considered articles that meet the inclusion criteria. For assessing the methodological quality of extracted studies, we utilized the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) scale [29].

Statistical Analysis

We examined the studies’ heterogeneity using both Q test and I2 statistics. Heterogeneity is a crucial subject in meta-analysis as it indicates the suitability of combining the studies and affects the reliability of results. The traditional method to examine heterogeneity is the Q test. However, because the Q test often has low statistical power and does not provide an insightful explanation for clinicians, most meta-analyzers also use other measures, such as the I2 statistic, to quantify the level of heterogeneity [30]. The Q statistic partitions the variability we find between studies into variability due to random variation and variability due to potential differences between the studies. The Q test produces p values that imply a binary decision of either presence or absence of heterogeneity [30]. The I2 statistics determine the ratio of the observed variance, which cannot be assigned to the sampling error. I2 indicates the amount to which confidence intervals (CI) of a study estimate overlap with one another. Thus, a significant overlap of confidence intervals results in low I2, and minimal overlap leads to a high I2 value [31]. We considered heterogeneity statistic I2 > 75% or p-value < 0.01 to show notable heterogeneity.

We conducted a funnel plot and Egger's regression test to examine if there was a publication bias. Publication bias seriously threatens the generalizability and validity of systematic review and meta-analysis results and could lead to under- or over-estimated effects. In assessing publication bias, the funnel plot illustrates each study's effect size against its precision or standard error. If all relevant studies are included in the meta-analysis without a publication bias, a symmetrical shape for the funnel plot would be expected. The plot would be asymmetrical if not all relevant studies are included in the analysis [32]. However, the visual examination of the funnel plot is usually subjective. Thus, some statistical tests, such as Egger's regression test, have been suggested for assessing publication bias in the funnel plot. Egger test is a widely used and standard procedure that is based directly on the funnel plot where it regresses the standardized effect estimate (i.e., the effect size divided by its standard error) on a measure of precision (i.e., the inverse of the standard error) [33]. If there is no publication bias, the regression intercept of the Egger test is estimated to be zero [34].

We employed the statistical package, Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 2 (CMA2) [35], to provide pooled estimates with corresponding 95% CI, and run heterogeneity analyses. There are two models for conducting a meta-analysis: fixed and random effects model. While fixed effect meta-analysis assumes a common effect, the random effects model assumes variations of effects from study to study. The fixed effects model considers differences between observed effect sizes because of sampling error. However, the differences in observed effect sizes in the random effects model are considered due to random error and variation in true effects. In this study, a random effects model was chosen for our analyses as the studies varied in terms of effect size. CMA2 automatically weights studies based on a random or fixed-effects model. Furthermore, the potential moderating role of PLWH population, country (location), and study time (year) that shape the context of each study and may influence HIV-related stigma and mass media policies were analyzed.

Results

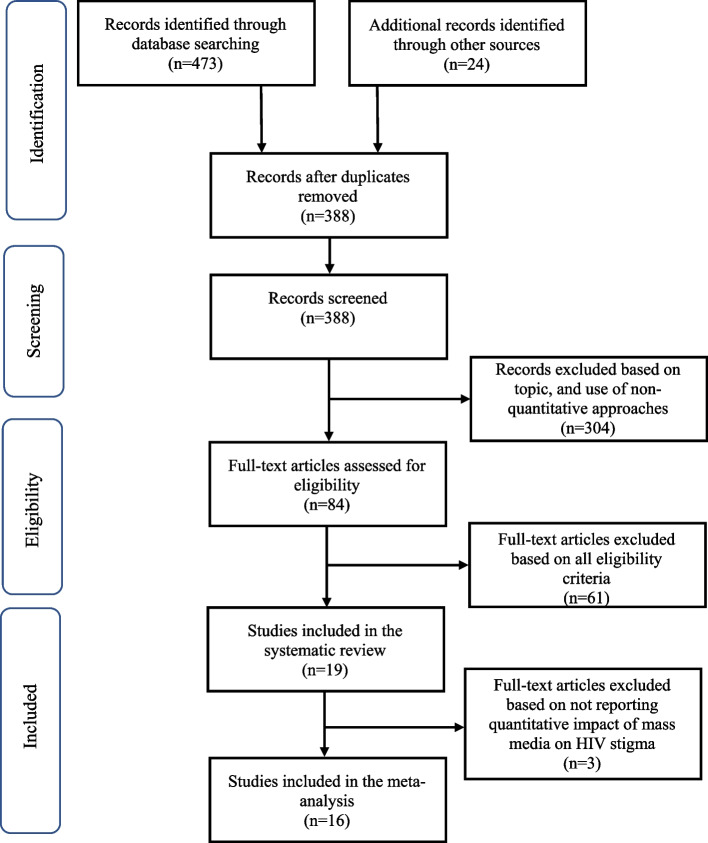

After removing duplicates, we found 388 potentially relevant studies in initial screening. However, 19 studies met the criteria for systematic review and 16 studies met all criteria for meta-analysis (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow of studies into the systematic review and meta-analysis

Systematic Review Results

The 19 included studies for systematic review were summarized by study time, setting (country), study design, sampling method, type of questionnaire administration, sample size, study population, media type, stigma type, and approach (see Table 1). Among these studies, nine studies were conducted in countries from Africa, eight from Asia, and two from North America (USA) in terms of geography. Indonesia and Nigeria each have been studied by three separate studies. Unexpectedly, no eligible study was found that quantitatively measured the impact of exposure to mass media such as TV, Radio, Movies, and Newspapers on HIV-related stigma before 2007. This may indicate that while HIV's global prevalence and its related stigma were significantly higher in the late 1990s and early 2000s, assessing the role of mass media quantitatively could have been overlooked in those time periods. However, systematic review results showed that many studies (8 out of 19) investigated the role of mass media on HIV-related stigma in the last 5 years, displaying a growing interest in the quantitative evaluation of the impact of mass media on HIV-related stigma in recent years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies in the systematic review

| Authors | Year and publisher | Setting | Study design | Sampling method | Questionnaire administration | Quality assessment | Sample size | Population | Media form | Stigma type | Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asamoah et al. | 2017, Global Health Action | Ghana | Cross-sectional survey | Multistage cluster and stratified | Face-to-face | > 75% | 3573 | Young women | TV, Radio | Social Stigma | General media exposure |

| Babalola et al. | 2009, Social Science and Medicine | Nigeria | Cross-sectional survey | Multistage random sampling | Face-to-face | > 75% | 10,081 | General population | TV, Radio, HIV media campaign | Social Stigma | Exposure to HIV-related messages in media; Media campaigns with messages about increasing the awareness of HIV, improving knowledge about modes of transmission, dispelling common myths about HIV transmission, and encouraging positive attitudes to PLWH |

| Bekalu et al. | 2014, PloS One | Sub-Saharan Africa | Cross-sectional survey | Multistage stratified sampling | Face-to-face | > 75% | 204,343 | General population | TV, Radio, Print media | Social Stigma | General media exposure |

| Bekalu and Eggermont | 2015, Journal of Communication in Healthcare | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional survey | Multistage cluster & random sampling | Face-to-face | > 75% | 977 | General population | TV, Radio | Social Stigma | HIV-related media use |

| Boulay et al. | 2008, Journal of AIDS Research | Ghana | Longitudinal survey | Cluster sampling | Face-to-face | > 75% | 5672 | General population | TV, Radio, Leaflets, Posters, Songs, Billboards | Social Stigma | HIV-related media campaign exposure; Encouraging compassion for PLWH by religious leaders; Highlighting the faith-based organizations’ role in addressing HIV |

| Hutchinson et al. | 2007, AIDS Education and Prevention | Botswana | Cross-sectional survey | Cluster sampling | Face-to-face | > 75% | 1065 | Households | Magazines, Billboard, TV, Radio, Newspaper | Social Stigma | Information about HIV; Stories about PLWH; HIV talks/discussions |

| Kerr et al. | 2015, AIDS Patient Care STDS | USA | Experimental | Convenience & snowball | Audio computer assisted self-interviews | > 75% | 1613 | African American Households | TV, Radio, Culturally-tailored media intervention | Social Stigma |

Sexual-risk reduction intervention; Enhancing HIV knowledge; Development of skills to reduce risky behaviors and increase self-efficacy |

| Lapinski and Nwulu | 2008, Health communication | Nigeria | Quasi-experimental | Snowball | Face-to-face | > 75% | 100 | General population | Film | Social Stigma | A mediated intervention designed to reduce HIV-related stigma and risk perceptions |

| Li Li et al. | 2009, Journal of Psychology | China | Cross-sectional survey | Multistage random & stratified | Face-to-face | > 75% | 1101 | Food market workers | TV, Radio, Publications, Posters, Internet | Social Stigma | Exposure to HIV information through mass media |

| Rimal et al. | 2015, Journal of Communication | Nepal | Cross-sectional survey | Multistage | Face-to-face | > 75% | 13,845 | General population | TV, Radio, Newspapers | Social Stigma | General media exposure |

| O'Leary et al. | 2007, AIDS Education and Prevention | Botswana | Cross-sectional survey | Convenience | Face-to-face | > 75% | 419 | Viewers and nonviewers of the storyline | TV series | Social Stigma | Exposure to HIV-related TV series |

| Setiyawati and Meilani | 2020, Journal of Education and Learning | Indonesia | Quasi-experimental | Convenience | Face-to-face | > 75% | 100 | Students | Video clip | Social Stigma | Intervention by providing HIV information through video clips |

| Siregar et al. | 2019, Journal of Nursing and Health Services | Indonesia | Quasi-experimental | Convenience | Face-to-face | < 75% | 53 | Adolescents | Leaflets, Audio-visual media | Social Stigma |

Health promotion intervention with leaflets and audiovisual media |

| Aghaei, et.al. | 2020, Journal of Informatics in Medicine Unlocked | Iran | Cross-sectional survey | Multistage clustering | Face-to-face | > 75% | 315 | General population |

Print media, TV, Movies, Radio, Internet |

Social Stigma | Exposure to HIV information through media |

| Tianingrum | 2018, Linu Kesehat | Indonesia | Cross-sectional survey | Multistage clustering | Self-administered | < 75% | 785 | High school students | TV, Books, Posters/leaflets, Magazines, Newspapers, Internet | Social Stigma | Exposure to HIV information through media |

| Thaker et al. | 2018, Journal of Health Communications | India | Cross-sectional survey | Snowball | Face-to-face | > 75% | 225 | Men who have sex with men and transgender females |

Newspapers, TV programs, Movies |

Experienced stigma, Self-stigma, Normative stigma, Vicarious stigma, Media stigma |

Exposure to media stigma |

| Kingori et al. | 2017, AIMS Public Health | USA | Cross-sectional survey | Convenience | Face-to-face | > 75% | 200 | College students | Posters, Signs and Billboards, Brochures, Newspapers, Presentations, TV, Radio; Internet | Social Stigma | Exposure to HIV information through media |

| Fakolade et al. | 2009, Journal of Biosocial Science | Nigeria | Cross-sectional survey | Multistage cluster & random sampling | Face-to-face | > 75% | 31,692 | General population | Mass media campaigns | Social Stigma | Exposure to Mass media campaigns (viewer-ship, listenership, and frequency) |

| Dehghan et al. | 2020, Shiraz E-Medical Journal | Iran | Cross-sectional survey | Stratified and convenience | Self-administered | > 75% | 900 | General population | Radio, TV, Newspapers, Magazines | Social Stigma | HIV information through media |

The recent growing attention to the relationship of mass media with HIV-related stigma can be explained in multiple ways. First, it may be an indicator of the significant amount of information provided by the mass media in recent years to shape our beliefs, attitudes, and perceived norms [36, 37]. Second, it may illustrate the growing concerns of societies regarding the detrimental effects of diseases-related stigma and discrimination on people [38]. Third, from eight studies conducted in the last 5 years, seven studies addressed the impact of media on HIV-related stigma in developing countries, especially in Asia. This may indicate a shift in the approaches utilized by health policymakers and governments in developing countries with a greater HIV prevalence to employ mass media for reducing HIV-related stigma in society and address the health of vulnerable groups like PLWH. In this regard, the 2021 state of HIV stigma study reported that 56% of non-LGBTQ respondents said they are seeing more stories about PLWH in the media, up four points from 2020. UNAIDS also recently announced its intermediated 2025 targets in which incorporating laws and policies to improve access to HIV care and minimizing discrimination towards PLWH were the main themes of increasing the quality of care in PLWH.

According to UNAIDS data, discriminatory attitudes towards PLWH remain unacceptably high in all developing countries where surveys have been conducted [39]. Moreover, the transition of HIV prevention, especially in Asian countries due to lack of international funding, requires a change toward more governmental strategies to address the HIV epidemic [40]. Given the dominancy of state media such as national TV and radio in many developing countries [41] and the access of nearly all populations to these media, more use of mass media to combat HIV-related stigma in developing countries can justify, to some extent, the heterogeneity in systematic review results (see Table 1) in terms of study’ time and setting (country).

Among the different types of populations that have been covered, the general population has been examined in nearly half of studies (9 out of 19). As HIV-related social stigma can adversely impact many aspects of PLWH life including their access to healthcare, well-being, social support, etc., studies with the general population are needed to reflect the social aspects of HIV-related stigma. Young women [22], African American and Latino men [42], households [25, 43], workers [44], students [45, 46], adolescents [47], and LGBT communities [48] were other groups that have been investigated. While social stigma is an important type of HIV stigma addressed by many studies, other types, like internalized stigma, are not fully addressed. Only one study [48] investigated different types of HIV-related stigma among men who have sex with men (MSM) as a population vulnerable to HIV indicating an urgent need for more research on the on non-social types of HIV-related stigma in vulnerable populations in the danger of HIV and how mass media could impact these stigmas. Depending on the study design and population type, the sample size of these studies ranged from 53 in a quasi-experimental study on adolescents [47] to 204,343 individuals in a cross-sectional survey on general population [26].

Regarding the study design, most of the reviewed studies (14 out of 19 studies) were conducted through cross-sectional surveys. Considering the limitation of the cross-sectional study design in not establishing a true cause and effect relationship, more experimental or longitudinal studies are needed to explore the impact of mass media on HIV-related stigma reduction. A study [49] utilized data from a longitudinal survey and one study utilized data of two cross-sectional surveys at two timepoints [50] (see Table 1). Also, three intervention studies [45, 47, 51] utilized various quasi-experimental methods. Only Kerr et al. [43] employed a randomized controlled trial approach (experimental) to study the results of a mass media intervention and its impact on HIV-related stigma. The face-to-face interview was the primary approach to collecting data. However, two studies [52, 53] utilized self-administered surveys and Kerr et al. [43] used Audio computer assisted self-interviews. Regarding methodological quality, 17 out of 19 studies have a quality higher than 75% based on the STROBE scale [29].

In terms of mass media forms covered by reviewed studies, as expected, TV, Radio, and newspapers were among the major mass media considering their accessibility to many populations and their significant influence on adjusting social beliefs and attitudes toward PLWH. However, in the four mass media interventions (see Table 1), video clips and films were frequently used media for interventions. The lack of large scale mass media interventions to address HIV-related stigma could be partly due to the numerous social, cultural, and individual factors that interfere with the influence of mass media interventions and make them complex and non-effective in many cases. As stated by LaCroix et al. [54], mass media exposure could be related to personal characteristics such as gender, income, age, and relationship status, which make it hard to accurately evaluate the results of studies that only focus on media exposure. Also, factors such as social or political climate, public policy changes, and everyday events can influence HIV/AIDS-related behaviors leading to mixed results [54]. In this regard, a systematic review of the effectiveness of mass communication programs to alter HIV/AIDS-related behaviors in developing countries showed that for most of their studied outcomes, no statistically significant impact of mass media programs was found. Also, the effect sizes were usually small to moderate among those with statistically significant results [55].

Most studies investigating the interaction between mass media and HIV-related stigma were not interventional studies. They only explored the relationship between general media exposure or exposure to HIV information through media with HIV-related stigma. Four intervention studies that evaluated the effect of media on HIV-related stigma utilized different approaches, including a culturally-tailored sexual-risk reduction intervention by increasing HIV knowledge and skills to reduce risky behaviors [43], a mediated intervention through a film to reduce HIV-related stigma and risk perceptions [51], providing HIV information through video clips [45], and a health promotion intervention with leaflets and audiovisual media [47].

Meta-analysis Results

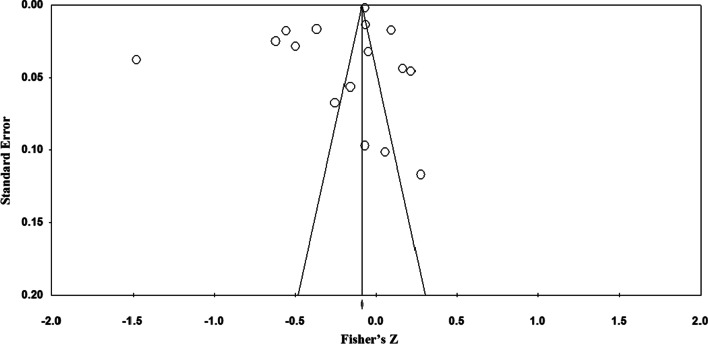

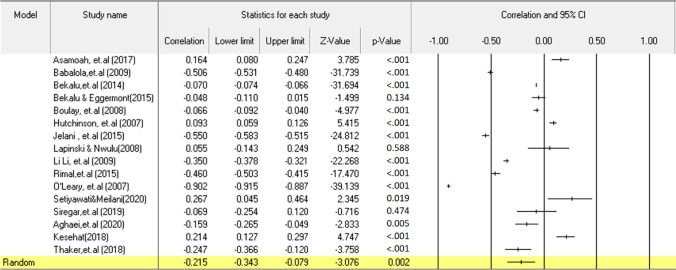

Statistical heterogeneity of studies was substantial (I2 = 0.99, Q = 3292.565; P < 0.001). The funnel plot indicates that there is no significant publication bias between studies (see Fig. 2). Egger's test also ascertained no significant publication bias (t = 1.50; P > 0.05). This test reveals that the relationship between media and stigma can vary in terms of the characteristics of studies. Therefore, utilizing moderating variables is essential to figure out the variance and place of these differences. Eleven studies found media was associated with stigma reduction [21, 23, 24, 26, 43, 44, 47–49, 56, 57] and five found media was associated with increased stigma [22, 25, 45, 51, 53] (see Table 2). However, most of the reported effect sizes were near zero which led to the mean for media effect (effects of random composition) on stigma equal to − 0.215 (see Fig. 3). As much as this estimated value is in the confidence range, we can say that the effect of media on reducing stigma is confirmed. The resulting pointed estimation (− 0.215) based on the Cohn criterion shows that although the impact of media on HIV-related stigma is statistically significant, it is in the moderate-to-low range.

Fig. 2.

Funnel plot of standard error by event rate shows no significant publication bias. Each circle shows a study

Table 2.

Basic statistics for studies in the meta-analysis

| Study | Country | Number of HIV cases | Effect size (r) | Lower limit | Upper limit | Z-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asamoah et al. (2017) | Ghana | 340,000 | 0.164 | 0.080 | 0.247 | 3.785 | < 0.001 |

| Babalola et al. (2009) | Nigeria | 1,800,000 | − 0.506 | − 0.531 | − 0.480 | − 31.739 | < 0.001 |

| Bekalu et al. (2014) | Sub-Saharan | 23.1million | − 0.070 | − 0.074 | − 0.066 | − 31.694 | < 0.001 |

| Bekalu and Eggermont (2015) | Ethiopia | 670,000 | − 0.048 | − 0.110 | 0.015 | − 1.499 | 0.134 |

| Boulay et al. (2008) | Ghana | 340,000 | − 0.066 | − 0.092 | − 0.040 | − 4.997 | < 0.001 |

| Hutchinson et al. (2007) | Botswana | 380,000 | 0.093 | 0.059 | 0.126 | 5.415 | < 0.001 |

| Kerr et al. (2015) | USA | 1,200,000 | − 0.550 | − 0.583 | − 0.515 | − 24.812 | < 0.001 |

| Lapinski and Nwulu (2008) | Nigeria | 1,800,000 | 0.055 | − 0.143 | 0.249 | 0.542 | 0.588 |

| Li Li et al. (2009) | China | 861,000 | − 0.350 | − 0.378 | − 0.321 | − 22.268 | < 0.001 |

| Rimal et al. (2015) | Nepal | 30,000 | − 0.460 | − 0.503 | − 0.415 | − 17.470 | < 0.001 |

| O’Leary et al. (2007) | Botswana | 380,000 | − 0.902 | − 0.915 | − 0.887 | − 39.139 | < 0.001 |

| Setiyawati and Meilani (2020) | Indonesia | 640,000 | 0.267 | 0.045 | 0.464 | 2.345 | 0.019 |

| Siregar et al. (2019) | Indonesia | 640,000 | − 0.069 | − 0.254 | 0.120 | − 0.716 | 0.474 |

| Aghaei et al. (2020) | Iran | 59,000 | − 0.159 | − 0.265 | − 0.049 | − 2.883 | 0.005 |

| Tianingrum (2018) | Indonesia | 640,000 | 0.214 | 0.127 | 0.297 | 4.747 | < 0.001 |

| Thaker et al. (2018) | India | 2,349,000 | − 0.247 | 0.366 | − 0.120 | − 3.758 | < 0.001 |

| N | Heterogeneity test | I2 | Egger’s test | Effect size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-value | Q Cochrane | p-value | t-value | r | p-value | ||

| 16 | < 0.001 | 3292.565 | 99.544 | 0.121 | 1.646 | − 0.215 | 0.002 |

Fig. 3.

The statistics and Forest plot of each study. Each study is shown by the point estimate of the prevalence (p) and 95% confidence interval for the p (lines)

Moderating Roles of the Country, Study Time (Year), and HIV Prevalence

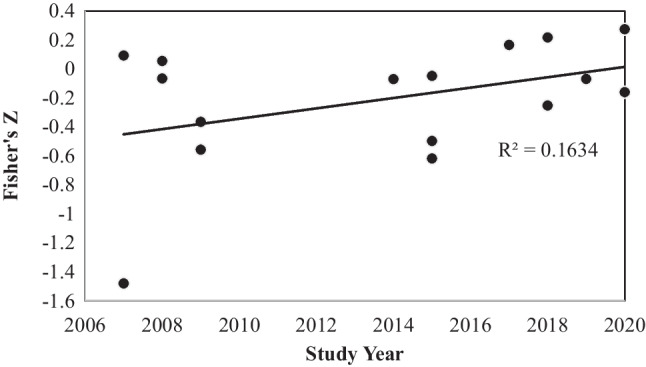

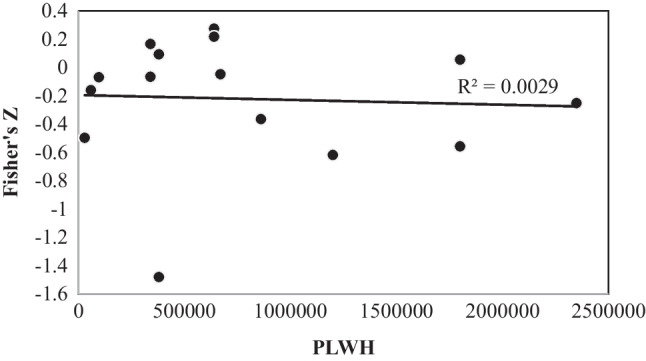

The meta-analytic results by considering countries as moderating variables showed Botswana, followed by the USA and China, has the highest impact of mass media on reducing HIV-related stigma (see Table 3). According to the meta-regression results, we can argue that the time that studies were conducted (1990–2020) has a moderate to weak effect (R2 = 0.16) on the relationship between the mass media and stigma (see Figs. 4, 5). Moreover, the upward slope of the meta-regression graph suggests an increase in the impact of the mass media on reducing the HIV-related stigma over time. Results also suggest that there is no moderating role for the number of PLWH on the relationship between the mass media and HIV-related stigma (see Fig. 5).

Table 3.

Relationship between mass media and HIV-related stigma in terms of the country

| Location | Effect size (r) | Lower limit | Upper limit | Z-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Africa | 0.011 | − 0.148 | 0.169 | 0.131 | 0.896 |

| Botswana | − 0.902 | − 0.915 | − 0.887 | − 39.139 | < 0.001 |

| China | − 0.350 | − 0.378 | − 0.321 | − 22.268 | < 0.001 |

| Ethiopia | − 0.048 | − 0.110 | 0.015 | − 1.499 | 0.134 |

| Ghana | 0.046 | − 0.179 | 0.267 | 0.398 | 0.691 |

| India | − 0.247 | − 0.366 | − 0.120 | − 3.758 | < 0.001 |

| Indonesia | − 0.069 | − 0.254 | 0.120 | − 0.716 | 0.474 |

| Iran | − 0.159 | − 0.265 | − 0.049 | − 2.833 | 0.005 |

| Nepal | 0.460- | − 0.503 | − 0.415 | 17.470- | < 0.001 |

| Nigeria | − 0.254 | − 0.696 | 0.328 | − 0.847 | 0.397 |

| USA | − 0.550 | − 0.583 | − 0.515 | − 24.812 | < 0.001 |

Fig. 4.

Regression of studies’ time (year) on Fisher’s Z. Each circle shows a study

Fig. 5.

Regression of people living with HIV (PLWH) in each country on Fisher’s Z. Each circle shows a study conducted in a country

Discussion

This study examines the impact of exposure to mass media such as radio, TV, newspapers, and movies on HIV/AIDS stigma. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative studies addressing this relationship. Systematic review results showed considerable heterogeneity in the studied populations and the need for more interventional and longitudinal studies on this subject. Results also indicated the lack of research on internalized stigma and the impact of mass media on them. Results suggest a higher interest in utilizing mass media by governments to reduce HIV-related stigma in developing countries with greater HIV prevalence. The meta-analysis results showed that, on Cohen's measure, the acquired effect size (− 0.215) of media on HIV-related stigma is on a medium to low scale. This result agrees with previous studies showing the significant but moderate influence of mass media exposure on reducing HIV-related stigma [21]. However, as shown in our meta-analytic results, the beneficial influence of mass media on HIV-related stigma reduction is not the same for all studied contexts, and six studies even report a harmful effect of mass media on HIV-related stigma. Regarding the bidirectional role of mass media in strengthening or weakening the process of HIV/AIDS stigmatization, Goepfert et al. [58] showed that even portraying sensitive moments in movies that have potentially stigmatizing content can affect stereotypes and negative emotions. Moreover, as mass media create moral panics, in some cases, they could portray PLWH as “folk devils” and contribute to their stigmatization [21]. Moral panic explains a scenario where a condition or individual will be considered a threat to societal values and interests. In this situation, mass media try to “make sense” of the problem and portray it stereotypically by discussing the moral meanings of risk and excessive attention to anxieties about pollution and contagion [21].

Furthermore, heterogeneity analysis of studies revealed the key role of moderator variables in understanding this impact. Heterogeneity in effect size for different studies can originate from many factors. Thus, we selected the HIV prevalence, country, and study year as the moderating variables. Our results showed that media were most effective in reducing stigma in Botswana, followed by USA and China in terms of the country. In the potential impact of the country variable on the mass media-HIV stigma relationship, the cultural context could play an important role. Culture is a dynamic process that portrays the way of life of a group of people and can include their life experiences and innovations of individuals. Botswana has seen a fast socioeconomic development since the 1970s [59].

The Botswana government has instituted several initiatives, such as decentralization and integration of services to enhance the physical and mental health of the population. Botswana culture is rich in values, institutions, and practices that can be further developed and integrated with the Western healthcare system currently dominating their healthcare system [59]. As the mass media play an essential role in delivering health messages in Western healthcare systems, in countries like Botswana that use the Western healthcare system similar to the United States, we expect a higher impact of mass media on HIV-related behaviors and stigma. We also have demonstrated how the underdeveloped role of the mass media in HIV-related debates in some developing societies like Iran could diminish its impact on reducing HIV stigma [21]. However, given the relatively small number of countries covered here, further studies would be recommended.

Moreover, the meta-regression analysis showed that the study's time (year) variable could weakly moderate the relationship between mass media and stigma (see Fig. 4). As time went on, the mass media became more effective in reducing stigma. Therefore, we can argue that as time passes, people's exposure to media will increase, and the more exposure to mass media, the greater the knowledge transmitted to the audience through the media. In this regard, we previously [21] showed a lower HIV-related stigma following increased HIV-related knowledge through media exposure. A similar finding was observed in a study investigating the effect of a health promotion intervention using pamphlets and audio-visual on adolescents' knowledge and attitudes toward the risk of HIV/AIDS [45].

This study showed that audio-visual media are more effective in increasing adolescents' knowledge and attitudes toward HIV/AIDS risk than pocketbook. Earlier studies also reported mass media as an important source of HIV/AIDS information that decreases stigmatizing behaviors [60, 61]. Thus, more interactions between health policymakers, governmental organizations, and mass media companies are needed to promote HIV/AIDS messages to vulnerable individuals experiencing HIV/AIDS stigma. In this regard, as suggested by Asamoah et al. (2017), Singhal and Rogers (1999), and Xiao et al. (2015), health messages are more effective through high-impact mass media, particularly radio and television, that can successfully change health behaviors even in people with low literacy and can communicate sensitive health messages to the individuals with HIV/AIDS stigmatizing behaviors [22, 60, 61]. Moreover, since HIV/AIDS is a global issue affecting many countries and requires national, regional, and supra-regional cooperation and coordination, a proper understanding of the patterns of globalization can help us in the policymaking for mass media to combat HIV-related stigma. Alignment of national and local media with global media can ease persuading the audience to stop the HIV stigma. We summarized some of the do’s and don’ts for mass media based on the review of available studies which can be used to inform future policies and programs in mass media (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Do's and don'ts for mass media

| Do's |

• Make programs with a rich content of HIV-related information to increase HIV knowledge • Provide culturally tailored health messages • Alignment of national and local media with global media • More interactions with health policymakers and governmental organizations regarding HIV-related policies • Focus on health messages through high-impact mass media like TV and radio • More brochures and audio-visual media |

| Don'ts |

• Do not portray sensitive moments that have potentially stigmatizing content • Do not prioritize their economic or politic interests over health-related issues • Do not present people living with HIV as patients |

One of the main challenges in evaluating the impact of mass media on HIV stigma is the limitation of available studies in measuring mass media impact. Most reviewed studies considered mass media exposure as their independent variable (see Table 1). Measuring general mass media exposure cannot capture all aspects of mass media and its impact on HIV-related stigma. While some studies partly addressed this limitation by measuring exposure to HIV-related programs, the variety of HIV programs and their content makes it challenging to determine what content or program is effective and what is not. Thus, more longitudinal and intervention studies on mass media stigma reduction programs with predesigned content need to be conducted for accurate evaluation. Moreover, there is an inconsistency between studies regarding the impact of mass media on HIV-related stigma (see Table 1). As discussed before, some level of this inconsistency originates from the context-dependent effect of mass media on HIV-related stigma. However, errors in the sampling and limitations of available studies could also contribute to this inconsistency. For example, the studied population type and intervention types might be biased.

Our study also has some potential limitations. First, estimates of effect size obtained in this study should be interpreted cautiously. High I2 statistics in the outcomes indicate a large proportion of the total variation in effect sizes due to between-study variation rather than sampling error. Thus, we utilized a random effect model for meta-analysis in this study. We also explored different sources of heterogeneity. Second, in this study, while we included 16 quantitative studies measuring the impact of mass media on HIV stigma in the meta-analysis, a higher number of studies may increase the accuracy of meta-analysis results.

Although, in this study, we didn’t include social media in our review of mass media studies considering the significant differences between social media and traditional mass media like TV, Radio, and print media, social media, provides a new framework for HIV vulnerable groups to communicate and can be used in media intervention studies. For example, MSM (men who have sex with men), a sexual and gender minority group with a high risk of HIV, are increasingly using social media to seek their social and sexual partners [62]. As shown by PEW Research Center, while 58% of the general people used social media platforms in 2013, the social media use was 80% for LGBT adults [63]. Also, social media do not have typical limitations of other mass media like control by governments (power) or limited to a specific country or culture, and measurement of the impact of HIV media programs on people is more accessible and less costly. Thus, social media can compensate for the lack of studies on HIV vulnerable groups and non-social HIV-related stigma by facilitating more media intervention programs among HIV vulnerable groups to reduce their stigma. However, although we are in the digital age, mass media strategies are still beneficial for reducing HIV-related stigma. Mass media is still the most accessible way for health communication and social marketing in resource-restrained settings, especially in developing countries; it represents some authority (either from the government or from the health professions); it is kind of material-based, papers, brochures, and other printed materials can be saved, shared, and read again and again, and it can cover different audiences based on their age and preferences.

In summary, by systematically reviewing and meta-analyzing the quantitative studies exploring mass media effects on HIV-related stigma, we showed that there is a modest and context-specific impact of mass media on the reduction of HIV-related stigma. We showed that different study contexts in terms of study time and country can impact the relationship between mass media and HIV-related stigma. We also revealed a lack knowledge on the current literature about the effectiveness of various mass media programs on HIV-related stigma especially among PLWH due to the limited large-scale studies exploring mass media interventions as well as research on the relationship between mass media and non-social types of HIV-related stigma among PLWH and vulnerable groups at risk of HIV infection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: AA; methodology: AA, AS, AK; formal analysis and investigation: AA, AS, AK, SQ, XL; writing—original draft preparation: AA, AK, AS; writing—review and editing: SQ, XL; supervision: SQ, XL.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Research Involving Human and Animals Rights

Not applicable.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sweileh WM. Bibliometric analysis of literature in AIDS-related stigma and discrimination. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9(4):617–628. doi: 10.1093/tbm/iby072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lupton D. Archetypes of infection: people with HIV/AIDS in the Australian Press in the Mid 1990s. Sociol Health Illn. 2008;21(1):37–53. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.t01-1-00141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahajan AP, Sayles JN, Patel VA, Remien RH, Sawires SR, Ortiz DJ, et al. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS. 2008;22(Suppl 2):S67–79. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000327438.13291.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Churcher S. Stigma related to HIV and AIDS as a barrier to accessing health care in Thailand: a review of recent literature. WHO South-East Asia J Public Health. 2013;2(1):12. doi: 10.4103/2224-3151.115829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tavakol M, Nikayin D. Stigmatization, doctor–patient relationship, and curing HIV/AIDS patients. J Bioeth. 2012;2(5):11–43. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parvin S, Eslamian A. The lived experience of social relations in women living with HIV. Women Dev Polit. 2014 doi: 10.22059/jwdp.2014.52356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turan JM, Nyblade L. HIV-related stigma as a barrier to achievement of global PMTCT and maternal health goals: a review of the evidence. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(7):2528–2539. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0446-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stangl AL, Lloyd JK, Brady LM, Holland CE, Baral S. A systematic review of interventions to reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination from 2002 to 2013: how far have we come? J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18734. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.3.18734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, Psaros C, Weiser SD, Bangsberg DR, et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18640. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.3.18640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.SeyedAlinaghi S, Paydary K, Afsar Kazerooni P, Hosseini M, Sedaghat A, Emamzadeh-Fard S, et al. Evaluation of stigma index among people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in six cities in Iran. Thrita J Med Sci. 2013;2(2):69–75. doi: 10.5812/thrita.11801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Amico KR, Copenhaver MM. HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: a test of the HIV stigma framework. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(5):1785–1795. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0437-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Touriño R, Acosta F, Giráldez A, Álvarez J, González J, Abelleira C, et al. Suicidal risk, hopelessness and depression in patients with schizophrenia and internalized stigma. Actas espanolas de psiquiatria. 2018;1(46):33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rice WS, Crockett KB, Mugavero MJ, Raper JL, Atkins GC, Turan B. Association between internalized HIV-related stigma and HIV care visit adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;76(5):482–487. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahlui M, Azahar N, Bulgiba A, Zaki R, Oche OM, Adekunjo FO, et al. HIV/AIDS related stigma and discrimination against PLWHA in Nigerian population. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0143749. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalichman S, Katner H, Banas E, Kalichman M. Population density and aids-related stigma in large-urban, small-urban, and rural communities of the Southeastern USA. Prev Sci. 2017;18(5):517–525. doi: 10.1007/s11121-017-0761-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karamouzian M, Mirzazadeh A, Rawat A, Shokoohi M, Haghdoost AA, Sedaghat A, et al. Injection drug use among female sex workers in Iran: findings from a nationwide bio-behavioural survey. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;44:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karamouzian M, Mirzazadeh A, Shokoohi M, Khajehkazemi R, Sedaghat A, Haghdoost AA, et al. Lifetime abortion of female sex workers in Iran: findings of a National Bio-Behavioural Survey in 2010. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(11):e0166042. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rueda S, Mitra S, Chen S, Gogolishvili D, Globerman J, Chambers L, et al. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: a series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e011453. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Comité consultatif sur les attitudes envers les PVVIH. Beaulieu M, Adrien A, Potvin L, Dassa C. Stigmatizing attitudes towards people living with HIV/AIDS: validation of a measurement scale. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1246. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Budhwani H, Hearld KR, Hasbun J, Charow R, Rosario S, Tillotson L, et al. Transgender female sex workers’ HIV knowledge, experienced stigma, and condom use in the Dominican Republic. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(11):e0186457. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aghaei A, Mohraz M, Shamshirband S. Effects of media, interpersonal communication and religious attitudes on HIV-related stigma in Tehran, Iran. Inf Med Unlocked. 2020;18:100291. doi: 10.1016/j.imu.2020.100291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asamoah CK, Asamoah BO, Agardh A. A generation at risk: a cross-sectional study on HIV/AIDS knowledge, exposure to mass media, and stigmatizing behaviors among young women aged 15–24 years in Ghana. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1331538. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1331538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Babalola S, Fatusi A, Anyanti J. Media saturation, communication exposure and HIV stigma in Nigeria. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(8):1513–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bekalu MA, Eggermont S. Socioeconomic and socioecological determinants of AIDS stigma and the mediating role of AIDS knowledge and media use. J Commun Healthc. 2015;8(4):316–324. doi: 10.1179/1753807615Y.0000000019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hutchinson PL, Mahlalela X, Yukich J. Mass media, stigma, and disclosure of HIV test results: multilevel analysis in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. AIDS Educ Prev. 2007;19(6):489–510. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.6.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bekalu MA, Eggermont S, Ramanadhan S, Viswanath K. Effect of media use on HIV-related stigma in sub-Saharan Africa: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(6):e100467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bresnahan M, Zhu Y, Hooper A, Hipple S, Savoie L. The negative health effects of anti-Asian stigma in the U.S. during COVID-19. Stigma and Health. 2022; No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified.

- 28.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335(7624):806–808. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin L. Comparison of four heterogeneity measures for meta-analysis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26(1):376–384. doi: 10.1111/jep.13159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Migliavaca CB, Stein C, Colpani V, Barker TH, Ziegelmann PK, Munn Z, et al. Meta-analysis of prevalence: I2 statistic and how to deal with heterogeneity. Res Synth Methods. 2022;13(3):363–367. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sedgwick P, Marston L. How to read a funnel plot in a meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;16(351):h4718. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin L, Chu H, Murad MH, Hong C, Qu Z, Cole SR, et al. Empirical comparison of publication bias tests in meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(8):1260–1267. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4425-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin L, Chu H. Quantifying publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2018;74(3):785–794. doi: 10.1111/biom.12817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Biostat. CMA2. 14 North Dean Street Englewood, NJ 07631 USA; 2006.

- 36.Fishman JM, Casarett D. Mass media and medicine: when the most trusted media mislead. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(3):291–293. doi: 10.4065/81.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fung A, Lau A. The Role of the Mass Media in Health Care. In 2020. p. 67–79.

- 38.Villa S, Jaramillo E, Mangioni D, Bandera A, Gori A, Raviglione MC. Stigma at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(11):1450–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hakawi A, Mokhbat J. The current challenges affecting the quality of care of HIV/AIDS in the Middle East: perspectives from local experts and future directions. J Infect Public Health. 2022;15(12):1508–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2022.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ren X, Xu J, Cheng F. Transition of HIV prevention in three Southeast Asian countries: challenges and responses to the withdrawal of the Global Fund funding. Glob Health J. 2021;5(4):194–197. doi: 10.1016/j.glohj.2021.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hallin DC, Mancini P, editors. Comparing Media Systems Beyond the Western World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011. (Communication, Society and Politics). https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/comparing-media-systems-beyond-the-western-world/1DBEDE293709F5588E53C3CC7CBCDB50

- 42.Garrett N, Norman E, Leask K, Naicker N, Asari V, Majola N, et al. Acceptability of early antiretroviral therapy among South African women. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(3):1018–1024. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kerr JC, Valois RF, DiClemente RJ, Carey MP, Stanton B, Romer D, et al. The effects of a mass media HIV-risk reduction strategy on HIV-related stigma and knowledge among African American adolescents. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29(3):150–156. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li L, Liang L, Lin C, Wu Z, Wen Y. Individual attitudes and perceived social norms: reports on HIV/AIDS-related stigma among service providers in China. Int J Psychol. 2009;44(6):443–450. doi: 10.1080/00207590802644774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Setiyawati N, Meilani N. The effectiveness of videos and pocket books on the level of knowledge and attitudes towards stigma people with HIV/AIDS. EduLearn. 2020;14(4):489–494. doi: 10.11591/edulearn.v14i4.15751. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kingori C, Adwoa Nkansah M, Haile Z, Darlington KA, Basta T. Factors associated with HIV related stigma among college students in the Midwest. AIMS Public Health. 2017;4(4):347–363. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2017.4.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siregar Y, Rochadi K, Lubis N. The effect of health promotion using leaflets and audio-visual on improving knowledge and attitude toward the danger of HIV/AIDS among adolescents. IJNHS. 2019;2(3):172–179. doi: 10.35654/ijnhs.v2i3.213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thaker J, Dutta M, Nair V, Rao VP. The interplay between stigma, collective efficacy, and advocacy communication among men who have sex with men and transgender females. J Health Commun. 2018;23(7):614–623. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2018.1499833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boulay M, Tweedie I, Fiagbey E. The effectiveness of a national communication campaign using religious leaders to reduce HIV-related stigma in Ghana. Afr J AIDS Res. 2008;7(1):133–141. doi: 10.2989/AJAR.2008.7.1.13.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fakolade R, Adebayo SB, Anyanti J, Ankomah A. The impact of exposure to mass media campaigns and social support on levels and trends of HIV-related stigma and discrimination in Nigeria: tools for enhancing effective HIV prevention programs. J Biosoc Sci. 2010;42(3):395–407. doi: 10.1017/S0021932009990538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lapinski MK, Nwulu P. Can a short film impact HIV-related risk and stigma perceptions? Results from an experiment in Abuja, Nigeria. Health Commun. 2008;23(5):403–412. doi: 10.1080/10410230802342093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dehghan M, Mokhtarabadi S, Tavakoli F, Iranpour A, RafieiRad AA, Nasiri N, et al. HIV-related knowledge and stigma among the general population in the Southeast of Iran. Shiraz e Med J. 2020;21(7):0–0. doi: 10.5812/semj.96311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tianingrum NA. The effect of information exposure on HIV-AIDS stigma in high school students (in Bahasa) J Ilmu Kesehat. 2018;6(1):51–59. [Google Scholar]

- 54.LaCroix JM, Snyder LB, Huedo-Medina TB, Johnson BT. Effectiveness of mass media interventions for HIV prevention, 1986–2013: a meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;15(66 Suppl 3):S329–340. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bertrand JT, O’Reilly K, Denison J, Anhang R, Sweat M. Systematic review of the effectiveness of mass communication programs to change HIV/AIDS-related behaviors in developing countries. Health Educ Res. 2006;21(4):567–597. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rimal RN, Chung AH, Dhungana N. Media as educator, media as disruptor: conceptualizing the role of social context in media effects: media as educator, media as disruptor. J Commun. 2015;65(5):863–887. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.O’Leary A, Kennedy M, Pappas-DeLuca KA, Nkete M, Beck V, Galavotti C. Association between exposure to an HIV story line in the bold and the beautiful and HIV-related stigma in Botswana. AIDS Educ Prev. 2007;19(3):209–217. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.3.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goepfert NC, Conrad von Heydendorff S, Dreßing H, Bailer J. Effects of stigmatizing media coverage on stigma measures, self-esteem, and affectivity in persons with depression—an experimental controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):138. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2123-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sabone MB. The promotion of mental health through cultural values, institutions, and practices: a reflection on some aspects of botswana culture. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2009;30(12):777–787. doi: 10.3109/01612840903263579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Singhal A, Rogers EM. Entertainment-education: a communication strategy for social change. Mahwah: Erlbaum Associates; 1999. 265 p. (LEA’s communication series).

- 61.Xiao Z, Li X, Lin D, Tam CC. Mass media and HIV/AIDS prevention among female sex workers in Beijing, China. J Health Commun. 2015;20(9):1095–1106. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1018575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Young SD, Szekeres G, Coates T. The relationship between online social networking and sexual risk behaviors among men who have sex with men (MSM) PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e62271. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pew Research Center . A survey of LGBT Americans. Washington: Pew Research Center; 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.