INTRODUCTION

Violence and aggression are common in mental health facilities, sometimes with grave consequences[1] warrant the formation of a guideline that addresses these issues.

The combination of extrinsic and intrinsic factors along with the context and setting of violence makes the task of its prevention and management a complex phenomenon. The intrinsic components mainly consisted of personality features, current serious mental stress, and difficulty in managing anger. On the other hand, extrinsic factors are more diverse and depend not only upon the physical and social context where violence and aggression happen but also on the aggressor’s attitude, victim’s characteristics, health professional’s training and experience, and perceived risk of danger.[2]

DEFINITIONS OF VIOLENCE AND AGGRESSION

Violence and aggression can be defined as a set of activities that may lead to harm to other persons. It can be expressed in actions or words, but the physical damage remains and the purpose is clear.[2]

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Aggression by patients in psychiatric wards may be a common occurrence. Studies show that 18%-25% of hospitalized patients exhibit violent behavior while in the ward.[3] High occurrence of aggression particularly verbal aggression is also reported by Emergency staff.[4]

The association of mental conditions with violence and aggression

Contrary to the popular public view that recognized the link between mental health problems (especially serious mental health problems such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia) and violence, the literature on this fact varies and shows mixed results.

People with mental health problems are more likely to become victims of violence than perpetrators, and most people do not engage in violence at all.[5] However, a consensus has emerged among researchers that a small fraction of patients have a relationship between mental health issues and violence.

Persons with organic brain dysfunction (post-traumatic, posthead injury, and seizure disorder particularly temporal lobe seizures) tend to exhibit violent and aggressive behaviour.

The Epidemiological Catchment area study[6] reported a 7.3% of lifetime prevalence of violence within the population who is free from psychiatric issues. On the other hand, the lifetime prevalence of violence was more than double (16.1%) in persons with schizophrenia or major affective disorders and 35% and 43.6% in those with substance use disorders and substance use disorder with comorbid mental health issues, respectively.

An association of violence was noticed, in different meta-analyses with Mood disorders, schizophrenia, and other psychosis.[7-9] A huge number of varieties were recognized with an odds ratio between 1 and 7 for schizophrenia in males and between 4 and 27 for females. For bipolar disorder, the odds ratio extended from 2 to 9. Be that as it may, for both disorders a comorbid substance-use disorder expanded the odds ratio up to 3-fold.

In the early 20th century, researchers recognized a set of symptoms called threat/control-over-ride symptoms that seemed to be associated with the risk of violence.[10] Threat/control-over-ride symptoms are delusional symptoms that make an individual feel like he is under threat and under the control of external forces.

Personal impact of violence and aggression against self and others

Staff within the hospital

A fraction of the injuries that happen to staff occur while trying to intervene in fights between patients, but staff may also receive injuries by unpredictable assaults made by patients who respond to their psychiatric symptoms or by confrontation while stopping patients from leaving the ward.[11] Sometimes staff also have to physically intercede to halt patients from harming themselves or attempting to take off to the ward, which may lead to aggression.

Individual consequences

Patients who carry on violence are likely to encounter more accommodation difficulties, diminished social relations, and social support and be more disconnected. As a result, violence can be dangerous for those involved and have a negative impact on quality of life.

Relatives, Carers, and Social networks

Family members, carers, and close contacts of patients are more likely to be injured when there is a risk of violence exists. On the other hand, in case the patient is living freely, relatives may pull back and stop supporting and visiting him if they frequently face aggressive and abusive behaviour.

In hospitals, staff blames a person’s illness as the source of hostility, while patients blame illness, interpersonal problems, and the environment equally as sources of aggression.[12]

This staff awareness is critical to understanding how staff responds to incidents of violence and the postincident support needed to effectively manage the impact on themselves and patients.[13]

Demographic and premorbid factors

Histories of aggression, schizophrenia, and recent illicit drug use are associated with aggression while inconclusive evidence for age, gender, and h/o conduct disorder. Causes of aggressive and violent behavior listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Causes of aggressive and violent behavior

| Medical causes | Psychiatric causes |

|---|---|

| Hypoxia, Hypercarbia, Lung Diseases | Acute Schizophrenic Excitement |

| Disturbed Blood Glucose Levels | Bipolar Disorder- Acute Mania |

| Malnutrition | Depression-Suicidal Behaviour |

| Drug effects and withdrawals - amphetamine, steroids, alcohol, prescribed medications, and drug interactions | Substance abuse disorder (Acute intoxication/withdrawal syndrome) Alcohol/opium/opiates/cannabis and other substances |

| Cerebral Conditions such as - Stroke, Seizure, Infections, Space Occupying Lesions, and Trauma | Acute Situational Reaction/ATPD |

| Infections - Systemic Sepsis, Urine Tract Infection in the elderly | Survivors of Sexual Assault |

| Metabolic and Electrolytic Disturbances | Borderline/Antisocial Personality Disorder/Conduct Disorder |

| Organ Failure - Liver or Renal Failure |

RISK FACTORS FOR AGGRESSION AND VIOLENCE

Risk factors are characteristics of the patient or their environment and care that make them more likely to behave aggressively.

Two types of risk factors:

-

Static risk factors:

Historical and remain unchanged

Example: Age, sex, family background, and childhood abuse.[14]

-

Dynamic risk factors:

Are changeable and hence there is an opportunity for intervention.

Examples: Presenting symptoms, alcohol and illicit substance consumption, and compliance issue with treatment.[14]

Risk assessment involves identifying risk factors and assessing the likelihood and nature of adverse outcomes. On the other hand, risk management involves methodologies to prevent these negative results from happening or to limit their effect. Some researchers believed that static factors were better suited to assess risk over the long term and dynamic factors for assessing the risk of violence in the short term.[14]

VIOLENCE ANDAGGRESSION RISK ASSESSMENT AND PREDICTION

Predicting events that are imminent or perceived as imminent is not a trivial task. But, in acute clinical scenarios, it is difficult to perform comprehensive assessments that comprise history and physical and mental status examination in patients with a risk of violence and aggression. Different methods of risk assessment and tool were listed in Tables 2 and 3 respectively.

Table 2.

Broadly there are three methods to assess risk

| Unstructured clinical assessments | Actuarial risk assessment | Structured clinical judgments |

|---|---|---|

| Past history of Violence and Aggression The effect of mental and physical health issues Personality and Substance use disorders Social and cultural components.[2] | Utilize quantifiable predictors based on research; to estimate a quantifiable value for the outcome in question. The main area of focus would be the likelihood of violence or assaultive behaviour happening within a short time period.[2] | It includes both the clinical appraisal approach and the actuarial methods. Risk factors identified from an extensive literature review will be assessed by raters using a variety of clinical sources.[2] |

Table 3.

Various violence-related risk assessment tools

| Broset Violence Checklist (BVC)[15] | This is a pen-and-paper based 6-point scale with a total rating score range from ‘0-6’. Each of the six components is scored for its presence (1) or absence (0). Cutoff is equal to or >2 It assesses: Threats- physical or verbal, irritability, confusion, vociferous behaviour, and attack on an object. |

| Classification of Violence Risk (COVR)[16] | Interactive and computer-based. Assess the risk of inpatient psychiatric patients committing violence against others. The software generates a report showing the patient’s risk of violence (violence likelihood ranges from 1% to 76%)., with an enumeration of risk factors that the program took into consideration for the risk estimation |

| Dynamic Appraisal of Situational Aggression (DASA)[17] | It is a seven-item pen and paper-based scale with scores ranging from ‘0-7’. Cutoff is equal to or greater than 2. Behaviour assessed: sensitivity to a perceived provocation, anger on denial the of request, irritability, impulsive behaviour, negative attitudes, verbal threat, and reluctance to follow directions. |

| Historical Clinical and Risk Management - 20 items (HCR-20)[18] | 20-item scale Include ten historical factors, five clinical factors, and five dynamic risk management factors. Scored on a 3-point scale (0-2), with higher scores reflecting the presence of risk factors. |

| Modified overt aggression scale (MOAS)[19] | Measure verbal and physical aggression of people with intellectual disabilities in the community. It is suitable for assessing the effectiveness of interventions aimed at controlling aggressive-challenging behavior in this group. |

| Nursing Observed Illness Intensity Scale (NOIIS)[20] | Behavioral improvement and symptom reduction can be measured more objectively. Completed by an experienced nurse on duty at the end of each shift, based on observations and patient interactions. Can also be used to track patient progress, response to treatment changes, and discharge eligibility. This scale can be used for clinical studies of treatment outcomes. |

| Psychopathy Checklist Revised (PCL-R)[21] | The PCL was designed to use for legal offenders. There are 20 points, each scored on a 3-point ordinal scale (0-2) based on information gathered from the offender’s institutional record. This instrument capture idea about the offender’s interpersonal relationships, education, occupation, family life, marital status, current and past offenses, drug, and alcohol use, and health problems. |

| Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability (START)[22] | It consists of 20 items. Scoring ranges from ‘0-2’ (0=no relevant strengths/vulnerabilities; 1=some relevant strengths/vulnerabilities; and 2=definite strengths/vulnerabilities. Assess dynamic risk factors for seven adverse outcomes: violence, self-harm, suicide, substance misuse, victimization, self-neglect and unauthorized leave. No ‘cut-off’ scores are provided. |

| The Violence Risk Appraisal Guide-Revised (VRAG-R)[23] | It is an actuarial risk assessment instrument that contains 12 items. It is appropriate for males who are 18 years old or more and have committed serious, violent, or sexual offenses. The instrument scores based on clinical records rather than interviews and provides a numerical risk estimate. |

Various places where violence risk may be present

Institutional facilities: includes large and small hospitals, nursing homes, long-term care facilities, inpatient/outpatient care facilities, small clinics, and community health facilities.

Fieldwork settings: healthcare or social workers who sometimes need to make home visits.

Use safety measures in all settings to prevent violence and aggression.[24]

MANAGEMENT OF AGGRESSION AND VIOLENCE

Management of aggressive and violent behavior will depend upon the sensorium and orientation of the patient at the time of the presentation. If the patient is disoriented/delirious then the management would be as per the guidelines of a delirious patient.[25] If he/she is well oriented and has clear sensorium then management will be as follows.

Verbal de-escalation

Restrictive interventions

-

Pharmacological management

-

VERBAL DE-ESCALATION

Process of verbal de-escalation describe in Table 4

-

RESTRICTIVE INTERVENTION

Modifications as per the environment

Personal and institutional alarms to be fixed in easily accessible site.

-

Table 4.

Verbal De-escalation

| Three step approach | Domains of De-Escalation | Descalation in the Emergency setting |

|---|---|---|

| The patient is verbally involved. collaborative partnership is established. The patient verbally de-escalates from excitement.[26] | Respect personal space. Do not be provocative. Communicate verbally. Be brief. Be aware of desires and emotions. Listen carefully to the patient. Agree or agree to disagree. Laydown law. Set clear boundaries. Provide choice and optimism. Debrief patients and staff.[26] | Physical spaces should be designed for safety. Appropriate training of staff to deal with agitated patients. Use objective instruments to assess agitation. Physicians should monitor themselves and feel safe when approaching the patient.[26] |

Common restrictive interventions include

A. Physical Restraint

As per section 97 of the Mental Health Care Act 2017, physical restraint should only be used when there is imminent and immediate harm to the person concerned or to others and it should be authorized by a psychiatrist in charge.

Salient points to be considered as per the mental health act 2017 for physical restraint:

Physical restraint should not be used longer than necessary.

Treating psychiatrist or medical officer should be responsible for ensuring the method and nature of the restraint, its justification, and appropriate record.

The nominated representative should be informed if restraint is prolonged beyond 24 hours.

It should not be used as a punishment method or counter to staff shortage.

A person should be placed under restraint at a place where he can cause no harm to him or others and be under regular supervision by medical personnel.

All instances should be reported to the mental health board on monthly basis.

For further reference, a reader can use specific restraint guidelines for mental health services in India by Raveesh et al.[27]

Techniques used for Physical restraint

Approach 1

For physical restrain, patient should be lying down on the bed. Both upper and lower extremities should be tied with soft clothes or bandages.

Constant monitoring of patients during mechanical restraint is a must.

If constant monitoring is not possible, the patient has to be visually observed for at least 15 minutes of restraint time and should be within eyesight. And keep watch at every 10–15 minutes for the remaining hours.

Approach 2

In the prone position, both arm and legs should be joint to the bedside.

It should be done with cotton bandage.[2]

This will allow some free movement of patient during restrain.

Physical restraint techniques should be modified as per the patient’s condition and physical health.[2]

B. Seclusion

Seclusion is not permitted in India as per the existing Mental Health Care Act 2017. However, in western guidelines, seclusion is reported as one of the techniques.

It is ‘the involuntary imprisonment of an individual in a room from which the individual is physically avoided from moving out. Patients were watched each 10 to 15 minutes through a window within the door.[2]

One randomized controlled trial[28] reported a low level of evidence that suggests a minimal restrictive care (seclusion) is as effective as a more prohibitive pathway (mechanical restraint).

Three reviews[29-31] reported that although staff believes restrictive measures to be a necessary step, this was also associated with the feeling of regret, trauma, and concern about the therapeutic relationship.

Advisable Laboratory Investigations

As soon as the patient is cooperative or sedated by pharmacological management, the following investigations may be done to rule out comorbid organic conditions or for the planning of pharmacological management.

Full Blood Count

Liver Function Test

Kidney Function Test

Blood Glucose level

Electrocardiogram

Electrolytes

Urinary drug screening

Brain scan (optional, after clinical judgment)

3. PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT

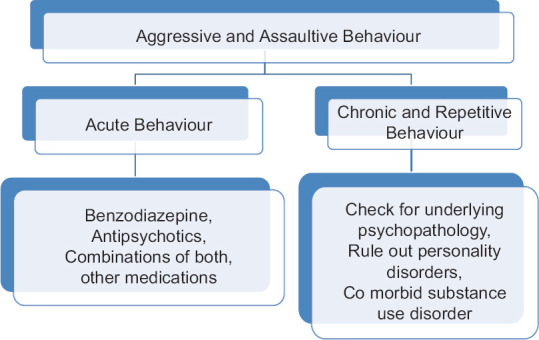

Every individual with aggressive and assaultive behaviour presented with a different set of issues. There is a lack of good scientific literature in the area of medical management in the acute setting for aggressive and assaultive behaviour. Pharmacological management of aggressive and assaultive behaviour should be considered only when other methods of management failed or respond inadequately.[32] Selection of pharmacological treatment for aggressive and assaultive agitation should be based on underlying etiological issues and psychiatric diagnosis. See the overview of pharmacological management of aggression and assaultive behaviour in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Outline of pharmacological management of aggressive and violent behaviour

Psychiatric reasons for the presentation of acute aggressive behavior are due to psychotic illnesses like schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, substance-related issues, conduct disorder, intermittent explosive disorder, and personality problems. Certain patient-related and medication-related factors should be kept in mind before planning an effective management plan.[33] Factors to be considered in the pharmacological management of aggressive and violent behaviour shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Factors to be considered in the pharmacological management of aggressive and violent behaviour[33,35]

| Patient-related factors |

| Age: Appropriate consideration to be given in case of old age and children |

| Sex: Gender-related issues in the side effect profile should be kept in mind. |

| Comorbid medical disorder: Liver and Renal function status should be assessed. |

| Comorbid psychiatric disorder: The patient should offer dose optimization in ongoing medication. |

| Substance use disorder: drug interactions with substance use and consideration for over sedation. |

| Collateral history: Input about physical health and current and past difficulties. |

| Patient preference and past response: help to guide about potential effects and side effects. |

| Physical health of the patient and current vital parameters: help in selecting medication based on current risks and benefits. |

| Medication-related factors |

| Cocurrent medication: risk of over-sedation should be kept in mind. |

| Drug interaction: particularly vigilant when a combination of medication use. |

| Side effects: Respiratory depression and cardiac conduction problems are major life-threatening problems always kept in mind. |

A mainstay for pharmacological treatment of aggressive and assaultive behaviour lies in rapid tranquilization in the short term. Search for psychopathology and/or medical reasons and appropriate management of it should be the next step of action.[2]

Presentation of such assaultive and aggressive behaviour is also varied in different settings like community, acute and emergency department, psychiatric inpatient setting, or medical setting. The definition of rapid tranquillization is subject to debate. The major goal of treatment is to archive calmness without oversedation of the patient and rapid control of acutely disturbed behaviour.[2,34] However, in the case of acute behavioural disturbance, level of sedation is required to a much deeper extent.

The Recent NICE guideline defines rapid tranquilization specific to the parental route, particularly by intramuscular and in the rare case intravenous route. Although this guideline also highlights the use of oral preparations before parental.[2] The general principles of pharmacological management of aggressive and violent behaviour listed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Principles of pharmacological management of aggressive and violent behaviour

| Individual management plan for the patient. |

| Reduce the suffering of the patient. |

| Providing a safe environment for others. |

| Produce calming effects, but avoid over-sedation. |

| Acute control of behavior and reduces the risk of involving stakeholders. |

| Pharmacological management should be the last option. |

| Avoid combination of medicine and high cumulative dose. |

| Consideration should be given to the patient physical health before considering treatment options. |

Management of acute aggressive and violent behaviour

No agent preferred over the other. The use of medication is based on various factors as mentioned in Table 5. Use of oral medication must be encouraged before any form of parenteral medicine.

But it may depend on the severity of the acute presentation, availability of resources, and patient cooperation.

Also, single medication use should be always preferred over a combination of medicines. Summary of some major studies with different medication combinations and their outcome listed in Table 7. A combination of more than one agent leads to develop unnecessary side effects and negative patient experience. The patient’s age and hepatic and renal function also consider before prescribing any agent.

Table 7.

| Comparison Arms | Outcome |

|---|---|

| IM Midazolam 7.5-15 mg v/s | Midazolam was more sedating [TREC 1] |

| IM Haloperidol 5-10 mg + Promethazine 50 mg | |

| IM Lorazepam v/s IM Haloperidol 10 mg + Promethazine25-50 mg | Combination was more effective [TRAC 2] |

| IM Haloperidol 5-10 mg v/s IM Haloperidol 5-10 mg + Promethazine 50 mg | Combination was more effective and tolerable [TRAC 3] |

| IM Olanzapine 10 mg v/s IM Haloperidol 10 mg + Promethazine25-50 mg | Olanzapine was as effective as another arm in the short term. But the effect did not last for a longer time. [TRAC 4] |

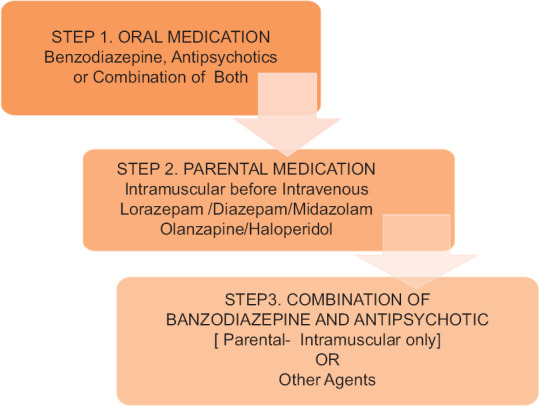

A stepwise approach should be considered as shown in the following path [Figure 2] for acute management of aggressive and assaultive behaviour.[2]

Figure 2.

Stepwise approach for acute management of aggressive and assaultive behaviour

Oral and inhaled treatment

Research supported the early use of oral medication due to the good efficacy of medications in controlling assaultive and violent behaviour. Patients with mild to moderate levels of agitation may show cooperation in taking oral medication. Benzodiazepines and antipsychotics have been used primarily to treat aggression and violent behavior.[2,36]

Benzodiazepine acts through the GABA receptors and it has anxiolytic, hypnotic, and anticonvulsant properties.[33]

Oral benzodiazepine is available in various formulations like melt –in mouth, oral disintegrated molecule, and buccal preparations. Oral Lorazepam, diazepam, and midazolam were used extensively in the past for controlling violent behaviour. Oral benzodiazepine is relatively safe and less associated with respiratory depression compared to its parental preparations.

Both first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics were used due to their brain-calming effect. Oral mouth-dissolving preparations of Olanzapine, Risperidone (both mouth dissolving and solution base preparation), Haloperidol, and Quetiapine have been used for a long time.[33] Sublingual Asenapine has also shown its effectiveness in managing acute behavioural changes.[33] Recently FDA approved inhaled form of Loxapine for the management of acute violent behaviour associated with schizophrenia and bipolar.[37] But the availability of bronchodilator medication should be ensured due to its serious adverse effect of bronchospasm. Commonly used medication and their adverse reactions are given in Table 8.

Table 8.

Various medication options available for rapid tranquilization, their dosage and maximum dose in 24 h and waiting interval[33,36,38]

| Route of administration | Drugs Dosage | Onset of action | Max dose in 24 h | Waiting interval | Special point |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | Lorazepam 1-2 mg | 20-30 min | 12 mg | 2 h | Oversedation, Amnesia, Respiratory depression, Paradoxical reaction |

| Risperidone 1-2 mg | 1 h | 6 mg | 1 h | EPS, Hypotension | |

| Olanzapine 5-10 mg | 2-6 h | 20 mg | 2-4 h | Hypotension, Over-sedation | |

| Haloperidol 5 mg | 30-60 min | 20 mg | 6 h | EPS, Hypotension QT prolongation | |

| Parenteral - Intramuscular | Lorazepam 2-4 mg | 15-20 min | 4 mg | 1 h | Oversedation, Amnesia, Respiratory depression, Paradoxical reaction |

| Olanzapine 2.5-10 mg | 15-45 min | - | - | EPS, Hypotension, over sedation | |

| Promethazine 25-50 | 30 min | 100 mg | 30 min | Excessive sedation | |

| Haloperidol 2.5-10 | 30 min | 30 mg | 30 min | EPS, Hypotension QT prolongation | |

| Lorazepam and haloperidol 2 mg+5 mg | 30 min | 15 mg/4 mg | 1 h | Oversedation, EPS, Hypotension QT prolongation | |

| Haloperidol and promethazine 5 mg+25 mg | 30 min | 30 mg/ 100 mg | 30 min | Hypotension, oversedation, EPS | |

| Intravascular | Lorazepam 1-4 mg | 1-5 min | 10 mg | 15 min | Oversedation, Amnesia, Respiratory depression, Paradoxical reaction |

| Midazolam 2.5-10 mg | 5 min | - | 10-15 min | hypotension, Amnesia, Respiratory depression, Paradoxical reaction | |

| Diazepam 10 mg | 1-5 min | 40 mg | 30 min | Oversedation, Amnesia, Respiratory depression, Paradoxical reaction | |

| Anesthetic agents. Ketamine | Should be given under strict medical intensive setup |

Parenteral treatment

Intramuscular preparations of Olanzapine, Haloperidol, Aripiprazole, Lorazepam, and Diazepam have been used for a long. Research has not shown the parental route has any advantage over the oral route in treatment efficacy but the onset of action is rapid with the parental route. A large observational study shows IM Olanzapine is more effective than all other second-generation antipsychotics.

The combination of IM midazolam and IM haloperidol is more effective than IM haloperidol alone.[2] NICE recommends intramuscular lorazepam should always try before haloperidol in case of insufficient information to guide the choice of medication.[2] Partial response to intramuscular lorazepam NICE recommends repeated doses of lorazepam based on considering risks and benefits. But in case of the partial response of intramuscular haloperidol addition of intramuscular promethazine should be tried.[2] Avoid the use of a combination of olanzapine intramuscular preparation with an intramuscular benzodiazepine in case of alcohol use.[38] ECG must be carried out before haloperidol because of the risk of QT prolongation.[2,38] The intravenous route is no longer advised as an initial choice for rapid tranquillization.[2,38]

Intravenous midazolam is more closely associated with respiratory depression. Flumazenil should have been kept handy whenever the intravenous injection of benzodiazepine is given.[38] Medication to be consider in various psychological conditions [Table 9] and consideration in case of the special populations mention in Table 10.

Table 9.

| Psychological and Medical conditions | Medication to be considered |

|---|---|

| Mood Disorder | Antipsychotics preferred over Benzodiazepine |

| Schizophrenia and Delusional Disorder | Antipsychotics preferred over Benzodiazepine |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder | Benzodiazepine |

| Substance Abuse Disorder- CNS depressant | Antipsychotics preferred over Benzodiazepine |

| CNS stimulant and alcohol withdrawal | Benzodiazepine |

| Delirium (Non-alcohol withdrawal) | Treat the underlying cause and antipsychotic only if necessary |

| Delirium (Alcohol withdrawal) | Benzodiazepine |

| Pregnancy | Antipsychotics |

| Dementia- BPSD | Low-dose antipsychotic only if necessary, considering risk and benefits |

Table 10.

| Children and Adolescents | Start with the lowest possible dose |

| Adjust dose according to age and weight | |

| Parental Lorazepam preferred over antipsychotics | |

| Use of benzodiazepine associated with | |

| paradoxical reaction and dis-inhibition | |

| More to prone side effects of antipsychotics | |

| Monitor Physical Health and Emotions of young person | |

| NICE - Recommends only intramuscular | |

| Lorazepam | |

| Older Adults | Start with the lowest possible dose |

| Use of benzodiazepine associated with | |

| paradoxical reaction and dis-inhibition | |

| More prone to side effects | |

| Physical Restrain | Prepared for complication |

| Risk assessment | |

| Observe within eyesight | |

| Substance Misuse | No agent superior to other |

| Consideration of IM Lorazepam | |

| Avoid Lorazepam in case of alcohol intoxication |

Management of agitation in emergency and consultation liaison specific should refer to specific guidelines by Raveesh et al.[43]

Monitoring in case of rapid tranquillization

Monitoring of sedation with appropriate tools and rating scales like the Ramsay scale, Richmond Agitation Sedation scale, and Sedation Assessment Tool should be carried out and postsedation documentation about the incident and trying to find out the cause for such behaviour is also an important part in the management of patients.[2] If possible, provide one-to-one nursing and eyesight observation for better management of the condition. Continuous monitoring of vital signs is as mentioned follows [Table 11].

Table 11.

Physical health monitoring in case of rapid tranquillization

| Physical and Clinical parameters | Interval |

|---|---|

| Pulse | Every 2 h |

| Blood pressure | |

| Temperature | Every 6 h |

| Respiratory rate | Constant |

| Oxygen saturation | Every 30 min |

| Clinical examination and check for oversedation | Before every dose |

Frequent monitoring of vitals every 15-20 min should be ideally carried out for high-risk patients.[2] One should also need to be watchful for acute side effects of antipsychotic medicines like Acute Dystonia, Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome, Acute Confusional State, Hypotension, Irregular Heart rates, and Respiratory Depression due to benzodiazepine.[38,44] Also staff should be trained in providing basic life-saving resuscitation and use of flumazenil in case of severe respiratory depression. Further investigations are required before giving a repeating dosage of medications and rule-out medical causes and medical comorbidities. If the patient is calm and cooperative for mental status examination, then an attempt should be made for the same.

Uncooperative violent and aggressive patient at home

For emergencies, medical treatment for mental illness may be provided by a registered medical practitioner to a person with mental illness either at a health establishment or in the community with the informed consent of a nominated representative. A nominated representative should be available at the time of evaluation. An emergency is to be considered and needs immediate intervention to prevent:

Death or irreversible harm to the health of a person;

Person inflicting serious harm to himself or to others; and

Person causing serious damage to property belonging to himself or to others where such behavior is believed to flow directly from the person’s mental illness.

For the purpose of treatment, only the situations mentioned above can be considered.

Emergency treatment duration is to be considered up to 72 hours from the initial evaluation by a registered medical practitioner/psychiatrist.

Emergency treatment includes transportation of a person with mental illness to the nearest mental healthcare establishment for assessment and management

If management at home is not possible or unaffordable relatives or caregivers of such patients should approach the nearest police station for escorting him/her to the nearest psychiatric care facility for management.

Management of chronic aggressive and assaultive behaviour

In some cases, aggressive and assaultive behaviour may persist for a longer duration. The use of specific medication should be required to control future behaviour. Use of a particular medication is based on consideration of clinical features and mechanism of action of the medication. Since no medication has been approved for this specific indication.[45]

The clinician must have to consider other groups of medication apart from antipsychotics and benzodiazepine (i.e., mood stabilizing antiepileptics, antidepressants).

The clinician should also try to diagnose underlying psychopathology in-depth and consider substance misuse and personality-related problems in the case of chronic aggressive behaviour. Prolonged use of antipsychotics in the elderly population should be considered against the risks and benefits.[45]

Workplace violence in psychiatry

Victims of workplace violence subsequently may develop psychological trauma, work avoidance, guilt feeling, powerlessness, and changes in relationships.

A follow-up program for addressing these abovementioned responses may be needed that includes counseling, critical incident stress debriefing, an employee-assistance program, and support groups.[24]

Safety and health training

All staff members should be trained in de-escalation techniques. Training can improve knowledge about hazards and safety measures.

Patient, client, and setting-related risk factors include

Working directly and alone with a person having a history of violence, substance abuse, gang membership, and possession of arms.

Faulty design of working place that may impede safe escape.

A deficit in means of emergency communication.

Transporting patients.

Working in a criminal neighborhood.[24]

Organizational risk factors

Poor staff training and policies, understaffing, inadequate security, overcrowded patients, and unrestricted movement in hospitals are the organizational risk factors.[24]

Training of health workers to reduce risk and violence

The topics for training may include a policy for violence prevention and documentation, possible risk factors, warning signs, diffusing anger and methods of dealing with hostile patients, safety devices and safe rooms, a response action plan, and self and staff defense.[24]

Appropriate training of supervisors to recognize dangerous situations so that they can avoid putting staff in such risky situations.

SUMMARY

Aggressive and assaultive behavior is a complex issue and is dealt with effectively with an appropriate management plan. Environmental modification and the safety of another person and the patient should be our priorities. Nonpharmacological methods should be the choice of initial response in case of such acute behavioral disturbance. A pharmacological approach should be used only in case of failure of other strategies. Extensive monitoring of physical health and trying to find out underlying psychopathological issues should be important aspects of care. Certain points like the definition of treatment end points, proper assessment instrument for response measurement, and issues related to consent and library of patients required further research in this area.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bourn J, Maxfield A, Terry A, Taylor K. A Safer Place to Work:Protecting NHS Hospital and Ambulance Staff from Violence and Aggression. London: National Audit Organization; 2003. [Last accessed on 2022 Nov 22]. p. 21. Part 3. Available from:https://www.nao.org.uk . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Violence and aggression:Short-term management in mental health, health and community settings. NICE guideline. 2015. [Last accessed on 2022 Dec 14]. Available from:https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng10 .

- 3.Muthuvenkatachalam S, Gupta S. Understanding aggressive and violent behavior in psychiatric patients. Indian J Psy Nsg. 2013;5:42–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gates DM, Ross CS, McQueen L. Violence against emergency department workers. J Emerg Med. 2006;31:331–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pettit B, Greenhead S, Khalifeh H, Drennan V, Hart TC, Hogg J, et al. At Risk, Yet Dismissed:The Criminal Victimisation of People with Mental Health Problems. London: MIND; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swanson JW. Mental disorder, substance abuse, and community violence:An epidemiological approach. In: Monahan J, Steadman H, editors. Violence and Mental Disorder:Developments in Risk Assessment. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1994. pp. 101–36. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Douglas KS, Guy LS, Hart SD. Psychosis as a risk factor for violence to others:A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:679. doi: 10.1037/a0016311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fazel S, Gulati G, Linsell L, Geddes JR, Grann M. Schizophrenia and violence:Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000120. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed. 1000120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fazel S, Lichtenstein P, Grann M, Goodwin GM, Långström N. Bipolar disorder and violent crime:new evidence from population-based longitudinal studies and systematic review. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:931–8. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Link BG, Stueve A. Psychotic symptoms and the violent/illegal behavior of mental patients compared to community controls. Violence and mental disorder:Developments in Risk Assessment. Report, NCJRS library. 1994. [Last accessed on 2022 Sep 25]. pp. 137–59. Available from:https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/psychotic-symptoms-and-violentillegal-behavior-mental-patients .

- 11.Nicholls TL, Brink J, Greaves C, Lussier P, Verdun-Jones S. Forensic psychiatric inpatients and aggression:An exploration of incidence, prevalence, severity, and interventions by gender. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2009;32:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ilkiw-Lavalle O, Grenyer BF. Differences between patient and staff perceptions of aggression in mental health units. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:389–93. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paterson B, McKenna K, Bowie V. A charter for trainers in the prevention and management of workplace violence in mental health settings. J Ment Health Training Educ Pract. 2014;9:101–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Douglas KS, Skeem JL. Violence risk assessment:Getting specific about being dynamic. Psychol Public Policy Law. 2005;11:347. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almvik R, Woods P, Rasmussen K. The Brøset Violence Checklist sensitivity, specificity, and interrater reliability. J Interpers Violence. 2000;15:1284–96. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monahan J, Steadman HJ, Appelbaum PS, Grisso T, Mulvey EP, Roth LH, et al. The classification of violence risk. Behav Sci Law. 2006;24:721–30. doi: 10.1002/bsl.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogloff JR, Daffern M. The dynamic appraisal of situational aggression:an instrument to assess risk for imminent aggression in psychiatric inpatients. Behav Sci Law. 2006;24:799–813. doi: 10.1002/bsl.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Douglas K, Hart S, Webster C, Belfrage H, Guy L, Wilson C. Historical-clinical-risk management-20, Version 3 (HCR-20 V3):Development and overview. Int J Forensic Ment Health. 2014;13:93–108. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorgi P, Ratey JJ, Knoedler DW, Markert RJ, Reichman M. Rating aggression in the clinical setting:A retrospective adaptation of the Overt Aggression Scale:Preliminary results. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1991;3:S52–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowers L, Brennan G, Ransom S, Winship G, Theodoridou C. The nursing observed illness intensity scale (NOIIS) J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18:28–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hare RD. Manual for the Hare Psychopathy Checklist –Revised. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Multi-Health Systems Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Webster CD, Nicholls TL, Martin ML, Desmarais SL, Brink J. Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability (START):The case for a new structured professional judgment scheme. Behav Sci Law. 2006;24:747–66. doi: 10.1002/bsl.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gregório Hertz P, Eher R, Etzler S, Rettenberger M. Cross-validation of the revised version of the violence risk appraisal guide (VRAG-R) in a sample of individuals convicted of sexual offenses. Sex Abuse. 2021;33:63–87. doi: 10.1177/1079063219841901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guidelines for Preventing Workplace Violence for Healthcare and Social Service Workers. U. S. Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration. OSHA 3148-06R. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grover S, Avasthi A. Clinical practice guidelines for management of delirium in Elderly. Indian J Psychiatry. 2018;60:329–40. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.224473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richmond JS, Berlin JS, Fishkind AB, Holloman GH, Jr, Zeller SL, Wilson MP, et al. Verbal De-escalation of the agitated patient:Consensus statement of the American Association for emergency psychiatry project BETA De-escalation workgroup. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13:17–25. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raveesh BN, Lepping P. Restraint guidelines for mental health services in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:S698–705. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_106_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huf G, Coutinho E, Adam C. Physical restraints versus seclusion room for management of people with acute aggression or agitation due to psychotic illness (TREC-SAVE):A randomized trial. Psychol Med. 2012;42:2265–73. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stewart D, Bowers L, Simpson A, Ryan C, Tziggili M. Manual restraint of adult psychiatric inpatients:A literature review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2009;16:749–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Der Merwe M, Bowers L, Jones J, Simpson A, Haglund K. Locked doors in acute inpatient psychiatry:A literature review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2009;16:293–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Happell B, Harrow A. Nurses'attitudes to the use of seclusion:A review of the literature. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2010;19:162–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2010.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerson R, Malas N, Feuer V, Silver GH, Prasad R, Mroczkowski MM. Best practices for evaluation and treatment of agitated children and adolescents (BETA) in the emergency department:Consensus statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20:409. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2019.1.41344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baldaçara L, Ismael F, Leite V, Pereira LA, Dos Santos RM, Gomes Júnior VP, et al. Brazilian guidelines for the management of psychomotor agitation. Part 2. Pharmacological approach. Braz J Psychiatry. 2019;41:324–35. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2018-0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patel MX, Sethi FN, Barnes TR, Dix R, Dratcu L, Fox B, et al. Joint BAP NAPICU evidence-based consensus guidelines for the clinical management of acute disturbance:De-escalation and rapid tranquillisation. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32:601–40. doi: 10.1177/0269881118776738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Searles Quick VB, Herbst ED, Kalapatapu RK. Which emergent medication should i give next?Repeated use of emergent medications to treat acute agitation. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:750686. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.750686. doi:10.3389/fpsyt. 2021.750686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson MP, Pepper D, Currier GW, Holloman GH, Jr, Feifel D. The psychopharmacology of agitation:Consensus statement of the American Association for emergency psychiatry project BETA psychopharmacology workgroup. Western J Emerg Med. 2012;13:26–34. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeller SL, Citrome L. Managing agitation associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in the emergency setting West J Emerg Med. 2016;17:165–72. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2015.12.28763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.David T, Thomas B, Allen Y. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry. 14th ed. UK: Willey Blackwell; pp. 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- 39.TREC Collaborative Group. Rapid tranquillisation for agitated patients in emergency psychiatric rooms:A randomised trial of midazolam versus haloperidol plus promethazine. BMJ. 2003;327:708–13. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7417.708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alexander J, Tharyan P, Adams C, John T, Mol C, Philip J. Rapid tranquillisation of violent or agitated patients in a psychiatric emergency setting. Pragmatic randomised trial of intramuscular lorazepam v. haloperidol plus promethazine. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:63–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huf G, Coutinho ES, Adams CE TREC Collaborative Group. Rapid tranquillisation in psychiatric emergency settings in Brazil:Pragmatic randomised controlled trial of intramuscular haloperidol versus intramuscular haloperidol plus promethazine. BMJ. 2007;335:869. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39339.448819.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raveendran NS, Tharyan P, Alexander J, Adams CE TREC-India II Collaborative Group. Rapid tranquillisation in psychiatric emergency settings in India:Pragmatic randomised controlled trial of intramuscular olanzapine versus intramuscular haloperidol plus promethazine. BMJ. 2007;335:865. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39341.608519.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raveesh BN, Munoli RN, Gowda GS. Assessment and management of agitation in consultation-liaison psychiatry. Indian J Psychiatry. 2022;64:S484–98. doi: 10.4103/indianjpsychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_22_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marder SR. A review of agitation in mental illness:Treatment guidelines and current therapies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 10):13–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simnon R, Tardiff K. Textbook of Violence assessment and management. 1st ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc; pp. 400–4. [Google Scholar]