Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the comprehensive prevalence of anxiety among postgraduates and estimate its changes with a meta‐analysis.

Method

Systematic retrieval to SAGE, ERIC, EBSCO, Wiley, ScienceDirect, ProQuest, PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science database was performed for quantitative studies on the prevalence of anxiety among graduate students published before November 22, 2022. The prevalence of anxiety synthesized with random‐effects model, and subgroup analysis was conducted by study characteristics (publication year, sampling method, and measurements) and subjects’ characteristics (gender, region, and educational level).

Result

Fifty studies were included in the meta‐analysis, totaling 39,668 graduate students. The result revealed that 34.8% of graduates suffered from the anxiety (95% CI: 29.5%–40.5%). Specifically, 19.1% (95% CI: 15.4%–23.5%) had mild anxiety, 15.1% (95% C: 11.6%–19.6%) had moderate anxiety, and 10.3% (95% CI: 7.2%–14.6%) had severe anxiety. And this prevalence showed a upward trend since 2005. Besides, master students suffered slightly less than doctoral students (29.2% vs. 34.3%), and female had similar anxiety to male (26.4% vs. 24.9%). Due to the COVID‐19, the prevalence of anxiety is higher after the pandemic than that before (any anxiety: 34.3% vs. 24.8%). Compared with other countries, students from Saudi Arabia, India, and Nepal were more vulnerable. The results of quality assessment showed that, 5 (10%) were in high quality, 21 (42%) were in moderate to high quality, 21 (42%) were in low to moderate quality, and 3 (6%) were in low quality. But, the studies with low quality tend to report a higher prevalence than that with high quality (40.3% vs. 13.0%), studies with nonrandom sampling tend to report a higher prevalence than that with random sampling (33.6% vs. 20.7%). Although we included the data collected based on the standard scales, there were higher heterogeneity among the measure (Q = 253.1, df = 12, p < .00).

Conclusion

More than one‐third postgraduates suffered from anxiety disorder, and this prevalence had a slight upward trend since 2005, school administrators, teachers and students should take joint actions to prevent mental disorder of graduates for deteriorating.

Keywords: anxiety disorder, graduate students, mental health, meta‐analysis, systematic review

Anxiety is the early manifestation of most psychological disorders, such as depression and obsessive‐compulsive disorder. Chronic environmental stress is main factor lead to anxiety, while stress among academics is alarmingly widespread, especially in postgraduate students, a group that typically faces high levels of job insecurity and unbalance between life and work. This study aimed toevaluate the comprehensive prevalence of anxiety among postgraduates and estimate its changes with a meta‐analysis.

1. INTRODUCTION

Anxiety, characterized as the continuous feelings of nervousness, trembling, together with fears, worries, and forebodings (Testa et al., 2013). In addition to intense feelings of fear or panic, people who suffered anxiety distress may experience other physical symptoms, such as fatigue, dizziness, headache, nausea, abdominal pain, palpitations, shortness of breath, and urinary incontinence (Eysenck et al., 2007; Moran, 2016). Anxiety is the early manifestation of most psychological disorders, such as depression and obsessive‐compulsive disorder (Marty & Segal, 2015). At worst, anxiety can even lead to suicide. While it took little attention in the general population, and often undetected and severely under‐treated (Kroenke et al., 2007). As WHO's report, 264 million of people living with anxiety disorders in the world, increased by 14.9% since 2005, ranked as the sixth‐largest contributor to nonfatal health loss globally and appear in the top 10 causes of Years Lived with Disability (YLD), in all WHO regions (WHO, 2017).

Chronic environmental stress is main factor lead to anxiety, while stress among academics is alarmingly widespread (Bozeman & Gaughan, 2011; Reevy & Deason, 2014), especially in postgraduate students (Kinman, 2001), a group that typically faces high levels of job insecurity and unbalance between life and work. As reported that, 85% of postgraduate students spent 41+ h a week on their postgraduate program, still, 74% of them were inability to finish studies in the set time, and 79% had uncertainty about their job and career prospects (Woolston, 2019), which evoked widely concern on the anxiety disorder among them.

Surprising but is expected, the anxiety in graduate students was six times than the general population (41% vs. 6%) (Evans et al., 2017). Numerous studies also explored the prevalence of anxiety disorder among them, while the observed prevalence of anxiety varied from 9.2% (Wang et al., 2018) to 86.0% (Garcia‐Williams et al., 2014), and the trajectory of the change remained unclear. A reliable estimation of anxiety prevalence of graduate students and its changes is essential to inform tailored efforts to prevent, identify, and treat mental distress, and to design a suitable public health policy.

2. OBJECTIVES

A comprehensive estimate of the anxiety prevalence and the change through the years is essential to inform targeted efforts to prevent and identify anxiety among graduate students. The present study systematically reviewed the publications on the anxiety disorder among graduate students to answer the following questions:

What is the prevalence of anxiety for graduate students?

How has the prevalence of anxiety changed through the year?

Is the prevalence of anxiety affected by the measure or sampling methods?

Is the prevalence of anxiety moderated by gender, education level, or region?

3. METHODS

This study was not preregistered.

3.1. Literature retrieve

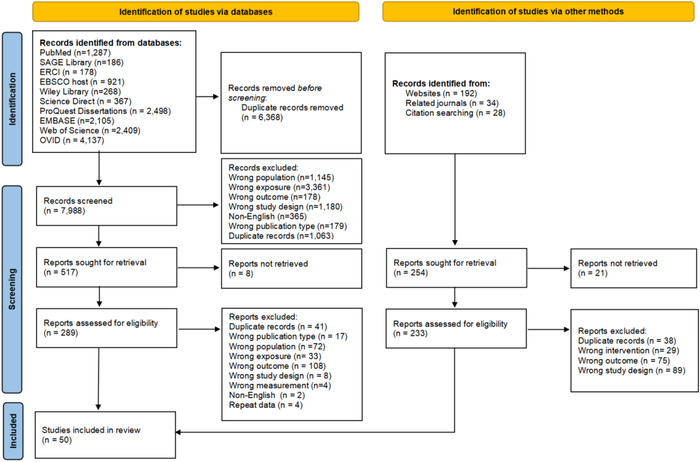

Systematic retrieval of the electronic database was performed, including SAGE, ERIC, EBSCO, Wiley, ScienceDirect, ProQuest, PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science database. The detail of search strings was displayed in Supplementary (see Table S1). We set no restrictions on the year of publication. Additionally, the reference lists of eligible studies and relevant review articles, as well as the related meta‐analysis on the mental health of graduate students were searched manually. The deadline for searching is up to November 22, 2022. The process of the retrieval and selection of primary studies was achieved by the first two authors, and any inconsistency was solved by the third author. The process of the literature search and the selection of articles was based on the PRISMA flow diagram (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of literature search and processing of records.

3.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included in the meta‐analysis, a primary study had to meet the following criteria: (a) the study population were healthy graduate students who aimed to pursue a master's or a doctoral degree, postgraduate‐training residents in medicine and other specializations were excluded; (b) the exposure was common anxiety, which measured by standardized instruments; the special anxiety such as social anxiety, death anxiety and performance anxiety were excluded; (c) the outcomes included the prevalence of anxiety symptom or can be referred from the paper; the studies missing total sample were excluded; (d) the studies used cross‐sectional design were included, experimental studies were excluded; (e) the article was published in English.

3.3. Information extraction and coding

Information extraction and coding included three parts: general information of study, the character of the sample and the outcomes. The general information of studies includes the title, author, the year of publication and collection; the character of the sample includes the information of sampling methods, sample size, the proportion of female, educational level, region; the outcomes includes methodological features (e.g., measurements, score system, score method, and standard for detection of anxiety) and effect size (prevalence of anxiety among graduate students). This progress conducted by the first two authors of the article and disagreements between coders were resolved by the third author.

3.4. Quality assessment

A modified version of the Newcastle‐Ottawa scale was used to assess the quality of studies included in meta‐analyses (Matcham et al., 2013). There are five domains: sampling method, sample size, participation rate, measurement tools, standards used to identify the anxiety disorder in the study (see Table S2 in supplement). Studies were rated as low quality (0–3 points), low to medium quality (4–6 points), medium to high quality (7–8 points), and high quality (9–10 points).

3.5. Data synthesis and analysis

Random‐effect model allowed to generalize findings from the included studies to a range of scenarios and larger population, a random‐effects meta‐analysis was performed in this review (Borenstein et al., 2009; Yaow et al., 2022). Q statistics and I 2 index were used to evaluate heterogeneity between studies. The I 2 index refers to the truly observed variation ratio (Borenstein et al., 2009), and 25%, 50%, and 75% of the I 2 respectively indicate low, medium, and high heterogeneity (Higgins & Thompson, 2002). Besides, “leave‐one‐out” method was adopted for sensitivity analysis to check for outliers that potentially influence the overall results (Cooper et al., 2009). Visual funnel plots and the “Fail‐safe N”method was conducted to evaluate potential publication bias. The fail‐safe N is the number of excluded studies with null results (i.e., zero effect sizes) that would be needed to bring their inclusion to lower the average effect size to a nonsignificant level (Rosenthal, 1979). Meta‐regression was used to identify the changes of anxiety prevalence, and stratified analysis in subgroups was used to explore the heterogeneity.

4. RESULTS

Fifty studies were included in the meta‐analysis. The data were collected from the United States (n = 19), the United Kingdom (n = 2), China (n = 15), India (n = 4), Australia (n = 1), Jordan (n = 1), Egypt (n = 1), Poland (n = 1), Croatia (n = 1), South Africa (n = 1), Nepal (n = 1), and Saudi Arabia (n = 1). The sample size ranged from 40 to 4477, totaling 39,668 graduate students. The proportion of females in each study ranged from 34.7% to 100%. The data were collected between 2005 and 2021, and 14 measures were used in primary studies. The details were shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Characters of primary studies included in the meta‐analysis

| Author, year | Year a | Sampling method | Sample | Female (%) | Age M (SD)/Rang | Level | Country | Measure | Score method | Criteria of identification | QA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abu Ruz et al. (2018) | NR | Nonrandom | 40 | NR | NR | Both | Jordan | HADS | 0–3 |

Mild: 8–10 Moderate: 11–14 Severe: 15–21 |

L‐M |

| Addonizio (2011) | 2010 | Nonrandom | 367 | 90.74% | 18–64 | Master | US | K10 | 1–5 |

Mild: 20–24 Moderate: 25–29 Severe: 30 and over |

M‐H |

| Ahuja and Kumar (2015) | 2013 | Nonrandom | 40 | 100.00% | 20–30 | Both | NR | HAM‐A | NR | NR | L |

| Aleena et al. (2020) | NR | Nonrandom | 400 | 50.00% | 23+ | Doctoral | China | DASS‐21 | 0–3 | NR | M‐H |

| Allen et al. (2022) | 2017 | Nonrandom | 2683 | 62.99% | 28/20–60 | Both | US | BAI | 0–3 |

Mild: 8–15 Moderate: 16–25 Severe: 26 and over |

M‐H |

| Almasri et al. (2022) | 2020 | Nonrandom | 308 | 45.13% | NR | Doctoral | US | GAD‐7 | NR | NR | L‐M |

| Al‐Shayea (2014) | 2013 | NR | 79 | 53.16% | 32/25–45 | Both | Saudi Arabia | DASS‐21 | 0–3 |

Mild: 8–9 Moderate: 10–14 Severe: 15–19 Extremely severe: 20 and over |

L‐M |

| Atkinson (2020) | 2019 | NR | 84 | 100.00% | NR | Both | Australia | DASS‐21 | 0–3 |

Mild: 8–9 Moderate: 10–14 Severe: 15–19 Extremely severe: 20 and over |

L‐M |

| Attia and Shata (2013) | 2013 | NR | 155 | 73.55% | 32.18(6.85)/ 22–52 | Both | Egypt | DASS‐21 | 0–3 | NR | L‐M |

| Balakrishnan et al. (2022) | 2020 | Nonrandom | 90 | 78.89% | 20–50 | Both | US | DASS‐21 | 0–3 |

Mild: 8–9 Moderate: 10–14 Severe: 15–19 Extremely severe: 20 and over |

L |

| Barreira et al. (2018) | 2017–2018 | Nonrandom | 510 | 34.71% | 20+ | Doctoral | US | GAD‐7 | 0–3 |

Mild: 5–9 Moderate: 10–14 Severe: 15 and over |

M‐H |

| Barton and Bulmer (2017) | 2010–2017 | Nonrandom | 4477 | 59.37% | 21+ | Both | US | PHQ‐9 | NR | NR | M‐H |

| Coakley et al. (2021) | 2020 | NR | 530 | NR | NR | Both | US | GAD‐7 | 0–3 |

Mild: 5–9 Moderate: 10–14 Severe: 15 and over |

M‐H |

| Cullinan et al. (2022) | 2018 | Nonrandom | 976 | NR | NR | Both | UK | DASS‐21 | 0–3 |

Mild to moderate: 8–14 Severe to extremely severe: 15 and over |

M‐H |

| Duan et al. (2022) | 2020–2021 | Nonrandom | 342 | NR | NR | Both | China | ZSAS | 1–4 |

Mild: 50–59 Moderate: 60–69 Severe: 70 and over |

M‐H |

| Eisenberg et al. (2007) | 2005 | Nonrandom | 1662 | 49.28% | 70% were 23–30 | Both | US | PHQ‐9 | NR | NR | L‐M |

| Ellison et al. (2020) | 2018 | NR | 59 | 81.36% | 25.48/23–36 | Doctoral | US | DASS‐21 | 0–3 | NR | L‐M |

| Evans et al. (2017) | NR | Nonrandom | 2279 | 70.38% | NR | 90% doctoral | 26 countries | GAD‐7 | NR | NR | L‐M |

| Fang et al. (2019) | 2018 | NR | 3669 | 57.62% | 22–28 | Master | China | GAD‐7 | NR | Positive symptom: 5 and over | L‐M |

| Garcia‐Williams et al. (2014) | 2010 and 2012 | Nonrandom | 301 | 77.08% | 27.98 (5.903)/18–63 | Both | US | PHQ‐9 | 0–3 | NR | L‐M |

| Ghogare et al. (2021) | 2020 | Nonrandom | 195 | 71.79% | 25–35 | Both | India | DASS‐21 | 0–3 |

Mild: 8–9 Moderate: 10–14 Severe: 15–19 Extremely severe: 20 and over |

L‐M |

| Hoying et al. (2020) | 2017–2018 | Nonrandom | 197 | NR | 24.5 (4.9) | Both | US | GAD‐7 | 0–3 |

Mild: 5–9 Moderate: 10–14 Severe: 15 and over |

L‐M |

| Jennifer et al. (2022) | 2020 | Nonrandom | 1916 | 85.80% | 20–45 | Both | US | DASS‐21 | NR | NR | L‐M |

| Jones‐White et al. (2022) | 2017–2018 | Random | 2582 | 55.46% | 18+ | Doctoral | US | GAD‐2 | 0–3 | Positive symptom: 3 and over | M‐H |

| Kowalczyk et al. (2021) | NR | NR | 528 | 55.49% | 26–30 | Doctoral | Poland | GHQ‐28 | 0–3 | Positive symptom: 28 and over | M‐H |

| Li et al. (2021) | 2020 | Random | 339 | 82.60% | 90% was 21–30 | Both | China | SCL‐90 | 1–5 | Positive symptom: subscale score over 2 | H |

| Liang et al. (2021) | 2020 | Nonrandom | 3137 | 78.29% | NR | Both | China | SAS | 1–4 |

Mild: 50–59 Moderate: 60–69 Severe: over 69 |

M‐H |

| Liu et al. (2019) | 2017 | Nonrandom | 325 | 60.31% | 31.1 (5.3)/ 23–47 | Doctoral | China | GAD‐7 | 0–3 |

Mild: 5–9 Moderate: 10–14 Severe: 15 and over |

M‐H |

| Liu et al. (2020) | 2017 | NR | 1625 | 54.15% | NR | Both | China | GAD‐7 | 0–3 | Positive symptom: 10 and over | M‐H |

| Madhan et al. (2012) | 2010 | Nonrandom | 330 | 44.85% | 26 (1.8)/ 24–34 | Master | India | DASS‐21 | 0–3 |

Mild: 8–9 Moderate: 10–14 Severe: 15–19 Extremely severe: 20 and over |

M‐H |

| Mazurek Melnyk et al. (2016) | 2014–2015 | Nonrandom | 91 | 65.93% | 25.43/21–51 | Both | US | GAD‐7 | 0–3 | NR | L |

| Milicev et al. (2021) | 2018–2019 | NR | 479 | 69.31% | 31.1 (9.1)/21–73 | Both | UK | GAD‐7 | 0–3 |

Mild: 5–9 Moderate: 10–14 Severe: 15 and over |

M‐H |

| Negi et al. (2019) | NR | NR | 76 | 50.00% | 21–35 | Both | India | DASS‐21 | 0–3 |

Mild: 8–9 Moderate: 10–14 Severe: 15–19 Extremely severe: 20 and over |

L‐M |

| Peng et al. (2022) | 2020–2021 | Nonrandom | 1410 | 73.48% | 23–26 | Both | China | GAD‐7 | 0–3 | Positive symptom: 10 and over | M‐H |

| Pervez et al. (2021) | 2019 and 2020 | NR | 113 | 49.56% | NR | Both | US | GAD‐7 | 0–3 |

Mild: 5–9 Moderate: 10–14 Severe: 15 and over |

L‐M |

| Ramadoss and Horn (2022) | 2021 | NR | 99 | 56.57% | NR | Doctoral | US | GAD‐2 | 0–3 | Positive symptom: 3 and over | L‐M |

| Rosenthal et al. (2021) | 2020 | NR | 222 | NR | 26–40 | Both | US | DASS‐21 | 0–3 | NR | L |

| Shadowen et al. (2019) | 2017 | Nonrandom | 344 | NR | NR | Both | US | BAI | 0–3 | Positive symptom: 19 and over | L‐M |

| Shete and Garkal (2015) | NR | NR | 50 | 66.00% | 23–34 | Both | India | DASS‐42 | 0–3 |

Mild: 8–9 Moderate: 10–14 Severe: 15–19 Extremely severe: 20 and over |

L |

| Talapko et al. (2021) | 2021 | Random | 370 | 84.32% | NR | Both | Croatia | DASS‐21 | 0–3 | NR | M‐H |

| Vuuren et al. (2021) | NR | NR | 108 | NR | NR | Both | South Africa | ZSAS | 0–3 |

Mild to moderate: 45–59 Severe: 60–74 Extremely severe: 75 and over |

L‐M |

| Wang et al. (2018) | 2017 | Random | 260 | 44.62% | NR | Both | China | SCL‐90 | 1–5 | Positive symptom: subscale score over 2 | H |

| Wang et al. (2020) | 2020 | Nonrandom | 375 | NR | NR | Master | China | GAD‐7 | 0–3 | Positive symptom: 5 and over | L‐M |

| Wu et al. (2022) | 2021 | NR | 1336 | 52.40% | 20+ | Both | China | ZSAS | 1–4 | Positive symptom: 50 and over | M‐H |

| Xiao et al. (2020) | 2020 | NR | 313 | NR | NR | Both | China | GAD‐7 | 0–3 |

Mild: 5–9 Moderate: 10–14 Severe: 15 and over |

M‐H |

| Yadav et al. (2021) | 2020 | Nonrandom | 409 | 83.13% | 22.10(2.928) | Both | Nepal | GAD‐7 | 0–3 |

Mild: 5–9 Moderate: 10–14 Severe: 15 and over |

M‐H |

| Zakeri et al. (2021) | 2020 | Nonrandom | 238 | 67.23% | NR | Doctoral | US | CCAPS‐62 | 0–4 |

Moderate: average sub scale‐score 1.22–1.89 Severe: average subscale score over 1.89 |

L‐M |

| Zhang et al. (2022) | 2021 | Random | 911 | 78.59% | NR | Both | China | ZSAS | 1–4 |

Mild: 50–59 Moderate: 60–69 Severe: 70 and over |

H |

| Zhou et al. (2018) | 2017 | Nonrandom | 1159 | 63.76% | NR | Both | China | SCL‐90 | 1–5 | Positive symptom: Subscale score over 2 | L‐M |

| Zhou et al. (2021) | 2020 | NR | 1080 | NR | NR | Both | China | GAD‐7 | 0–3 |

Mild: 5–9 Moderate: 10–14 Severe: 15 and over |

M‐H |

The end year of data collection.

NR: not report; QA: quality assessment; L: low quality (0–3 points); L‐M: low to medium quality (4–6 points); M‐H: medium to high quality (7–8 points); H: high quality (9–10 points); HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; K10: Kessler Psychological Distress Scale; HAM‐A: Hamilton Anxiety Scale; BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory; DASS: Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale; GAD‐7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7‐item; PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire; SAS: Self‐Rating Anxiety Scale; SCL‐90: Symptom Check List 90; CCAPS‐62: Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms; ZSAS: Zung's Self‐Rating Anxiety Scale; GHQ‐28: General Health Questionnaires.

4.1. Quality assessment

Quality assessment of primary studies including five domains: sampling method, sample size, participation rate, measurement method, and criteria for identifying the anxiety disorder. Five of 50 (10.0%) reports were in high quality, 21 (42%) were in moderate to high quality, 21 (42%) were in low to moderate quality, and 3 (6%) were in low quality (Table 1). We conducted a subgroup analysis based on the quality of included studies; the results showed that studies assessed with low quality reported higher prevalence of anxiety than that with high quality (any anxiety: 40.3% vs. 13.0%, Q = 11.7, df = 4, p = .01), and studies assessed with low to moderate quality reported higher prevalence of moderate and severe anxiety than that with high quality (moderate: 24.7% vs. 4.7%, Q = 59.8, df = 3, p < .00; severe: 15.1% vs. 1.4%, Q = 54.5, df = 3, p < .00).

4.2. Sensitivity analysis

With the method of leave‐one‐out method, we got 50 effect sizes of any anxiety, ranging from 32.8% to 36.0% (p < .00), 23 of mild anxiety, ranging from 18.8% to 20.2% (p < .00), 24 of moderate anxiety, ranging from 4.7% to 73.7% (p < .00), and 25 of severe anxiety, ranging from 0.9 % to 32.5% (p < .00). One study (Negi et al., 2019) was biased against the results of moderate anxiety, which was removed in the later analysis.

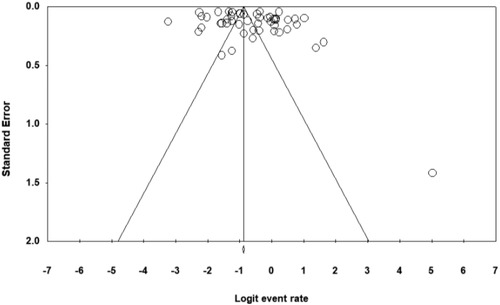

4.3. Publication bias

The funnel plots suggested that the studies were symmetrically distributed (Figure 2), and the fail‐safe number was larger than the recommended criteria (5K + 10, K means the number of studies included in meta‐analysis) in the prevalence of any anxiety (Nfs = 37,109 > 5K + 10 = 260), mild anxiety (Nfs = 13,409 > 5K + 10 = 125), moderate anxiety (Nfs = 14,744 > 5K + 10 = 125), and severe anxiety (Nfs = 16,514 > 5K + 10 = 135). These results showed that there was no potential publication bias.

FIGURE 2.

Funnel plot of anxiety prevalence among graduate students.

4.4. Prevalence of anxiety among graduate students

Fifty studies involved the any anxiety among graduate students with the prevalence ranging from 3.8% to 100.0%. Meta‐analytic pooling of the prevalence estimates of anxiety was 34.8% (N = 39,668; 95% CI: 29.5%−40.5%), with significant heterogeneity across studies (Q = 4683.1, p < .00; I 2= 98.9%). As shown in Table 2, 19.1% of them suffered mild anxiety (K = 23, N = 11,426; 95% CI: 15.4%−23.5%; Q = 513.3, p < .00; I 2= 95.7%), 15.1% moderate anxiety (K = 23, N = 10,720; 95% CI: 11.6%−19.6%;Q = 539.7, p < .00; I 2= 95.9%), and 10.3% severe anxiety (K = 25, N = 1850; 95% CI: 7.2%–14.6%; Q = 889.7, p < .00; I 2= 97.3%).

TABLE 2.

The results of subgroup analysis of anxiety prevalence among graduate students

| Any anxiety | Mild anxiety | Moderate anxiety | Severe anxiety | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K | Es | LL | UL | I 2 (%) | K | Es | LL | UL | I 2 (%) | K | Es | LL | UL | I 2 (%) | K | Es | LL | UL | I 2 (%) | |

| Quality of studies | Q = 11.704 ** | 98.95 | Q = 6.059 ** | 95.71 | Q = 69.674 ** | 95.92 | Q = 54.480 ** | 97.30 | ||||||||||||

| L | 5 | 0.403 | 0.233 | 0.600 | 92.88 | 3 | 0.093 | 0.014 | 0.419 | 94.22 | 3 | 0.176 | 0.083 | 0.335 | 83.00 | 3 | 0.093 | 0.060 | 0.141 | 13.09 |

| L‐H | 21 | 0.391 | 0.293 | 0.500 | 98.96 | 9 | 0.166 | 0.096 | 0.270 | 95.47 | 10 | 0.214 | 0.173 | 0.262 | 82.14 | 11 | 0.151 | 0.107 | 0.209 | 9.71 |

| M‐H | 21 | 0.341 | 0.268 | 0.423 | 99.19 | 10 | 0.226 | 0.176 | 0.286 | 96.31 | 9 | 0.113 | 0.069 | 0.180 | 97.34 | 10 | 0.087 | 0.045 | 0.160 | 98.36 |

| H | 3 | 0.130 | 0.066 | 0.241 | 94.60 | 1 | 0.159 | 0.137 | 0.184 | / | 1 | 0.047 | 0.035 | 0.063 | / | 1 | 0.014 | 0.008 | 0.024 | / |

| Sampling method | Q = 3.334 | 99.10 | Q = 3.087 | 96.43 | Q = 6.877 ** | 97.10 | Q = 0.004 | 98.36 | ||||||||||||

| Nonrandom | 27 | 0.336 | 0.264 | 0.416 | 99.17 | 12 | 0.206 | 0.155 | 0.269 | 96.90 | 12 | 0.133 | 0.090 | 0.192 | 97.10 | 13 | 0.083 | 0.047 | 0.143 | 98.34 |

| Random | 5 | 0.207 | 0.123 | 0.327 | 98.15 | 2 | 0.156 | 0.137 | 0.177 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.059 | 0.037 | 0.094 | 75.53 | 2 | 0.075 | 0.003 | 0.698 | 99.22 |

| Measure | Q = 528.159 ** | 98.95 | Q = 253.005 ** | 95.71 | Q = 207.174 ** | 95.92 | Q = 256.617 ** | 97.30 | ||||||||||||

| BAI | 2 | 0.200 | 0.149 | 0.262 | 82.72 | 0 | / | / | / | / | 0 | / | / | / | / | 0 | / | / | / | / |

| CCAPS‐62 | 1 | 0.496 | 0.433 | 0.559 | / | 0 | / | / | / | / | 1 | 0.252 | 0.201 | 0.311 | .00 | 1 | 0.244 | 0.193 | 0.302 | / |

| DASS‐21 | 13 | 0.558 | 0.483 | 0.631 | 95.06 | 12 | 0.147 | 0.103 | 0.206 | 95.00 | 10 | 0.194 | 0.155 | 0.241 | 87.64 | 12 | 0.184 | 0.142 | 0.236 | 93.39 |

| DASS‐42 | 1 | 0.800 | 0.667 | 0.889 | / | 1 | 0.360 | 0.240 | 0.501 | .00 | 1 | 0.320 | 0.206 | 0.460 | .00 | 1 | 0.120 | 0.055 | 0.242 | / |

| GAD‐2 | 2 | 0.305 | 0.163 | 0.496 | 93.53 | 0 | / | / | / | / | 0 | / | / | / | / | 0 | / | / | / | / |

| GAD‐7 | 16 | 0.353 | 0.269 | 0.448 | 98.93 | 6 | 0.318 | 0.298 | 0.339 | 1.83 | 6 | 0.138 | 0.102 | 0.184 | 85.75 | 6 | 0.077 | 0.041 | 0.138 | 93.41 |

| GHQ‐28 | 1 | 0.199 | 0.167 | 0.235 | / | 0 | / | / | / | / | 0 | / | / | / | / | 0 | / | / | / | / |

| HADS | 1 | 0.225 | 0.121 | 0.379 | / | 0 | / | / | / | / | 0 | / | / | / | / | 0 | / | / | / | / |

| HAM‐A | 1 | 0.175 | 0.086 | 0.324 | / | 1 | 0.025 | 0.004 | 0.157 | / | 1 | 0.130 | 0.056 | 0.273 | / | 1 | 0.025 | 0.004 | 0.157 | / |

| K10 | 1 | 0.518 | 0.467 | 0.568 | / | 0 | / | / | / | / | 0 | / | / | / | / | 0 | / | / | / | / |

| PHQ‐9 | 3 | 0.142 | 0.032 | 0.454 | 99.55 | 0 | / | / | / | / | 0 | / | / | / | / | 0 | / | / | / | / |

| SAS | 1 | 0.209 | 0.195 | 0.224 | / | 1 | 0.147 | 0.135 | 0.160 | / | 1 | 0.047 | 0.040 | 0.054 | 1 | 0.016 | 0.012 | 0.021 | / | |

| SCL‐90 | 3 | 0.111 | 0.097 | 0.126 | / | 0 | / | / | / | / | 0 | / | / | / | / | 0 | / | / | / | / |

| ZSAS | 4 | 0.248 | 0.197 | 0.307 | 88.33 | 2 | 0.153 | 0.135 | 0.175 | .00 | 3 | 0.078 | 0.018 | 0.282 | 97.36 | 3 | 0.022 | 0.006 | 0.075 | 88.21 |

| Education level | Q = 0.36 | 98.67 | Q =0 .038 | 88.31 | Q = 6.855 ** | 86.88 | Q =0 .053 | 95.35 | ||||||||||||

| Master | 9 | 0.292 | 0.180 | 0.437 | 99.01 | 2 | 0.237 | 0.212 | 0.263 | .00 | 1 | 0.261 | 0.216 | 0.311 | / | 6 | 0.135 | 0.068 | 0.252 | 47.71 |

| Doctoral | 14 | 0.343 | 0.252 | 0.447 | 98.25 | 5 | 0.229 | 0.160 | 0.315 | 91.75 | 5 | 0.165 | 0.121 | 0.220 | 83.82 | 6 | 0.135 | 0.068 | 0.252 | 96.47 |

| Gender | Q = 0.374 | 98.63 | Q = 0.031 | 86.07 | Q = 0.029 | 89.68 | Q = 0.131 | 91.78 | ||||||||||||

| female | 16 | 0.412 | 0.291 | 0.544 | 98.88 | 7 | 0.223 | 0.145 | 0.328 | 85.13 | 8 | 0.241 | 0.162 | 0.344 | 88.26 | 8 | 0.150 | 0.092 | 0.235 | 86.95 |

| male | 14 | 0.355 | 0.240 | 0.490 | 98.34 | 5 | 0.210 | 0.118 | 0.346 | 88.94 | 6 | 0.256 | 0.142 | 0.416 | 91.98 | 6 | 0.123 | 0.043 | 0.303 | 95.12 |

| Country | Q = 237.678 ** | 98.96 | Q = 6.069 ** | 95.87 | Q = 102.735 ** | 96.10 | Q = 98.458 ** | 97.40 | ||||||||||||

| Australia | 1 | 0.560 | 0.452 | 0.662 | / | 1 | 0.131 | 0.074 | 0.221 | / | 1 | 0.250 | 0.169 | 0.353 | / | 1 | 0.178 | 0.110 | 0.275 | / |

| China | 15 | 0.220 | 0.170 | 0.281 | 98.48 | 5 | 0.177 | 0.129 | 0.238 | 94.60 | 5 | 0.073 | 0.035 | 0.146 | 97.39 | 5 | 0.037 | 0.007 | 0.184 | 99.10 |

| Croatia | 1 | 0.532 | 0.481 | 0.583 | / | 1 | 0.149 | 0.116 | 0.189 | / | 1 | 0.076 | 0.053 | 0.108 | / | 1 | 0.307 | 0.262 | 0.356 | / |

| Egypt | 1 | 0.523 | 0.444 | 0.600 | / | 1 | 0.103 | 0.064 | 0.162 | / | 1 | 0.213 | 0.156 | 0.284 | / | 1 | 0.207 | 0.150 | 0.278 | / |

| India | 4 | 0.727 | 0.606 | 0.821 | 81.44 | 4 | 0.252 | 0.164 | 0.365 | 81.47 | 3 | 0.274 | 0.239 | 0.312 | .00 | 4 | 0.141 | 0.092 | 0.209 | 72.35 |

| Jordan | 1 | 0.225 | 0.121 | 0.379 | / | 0 | / | / | / | / | 0 | / | / | / | / | 0 | / | / | / | / |

| Nepal | 1 | 0.472 | 0.424 | 0.520 | / | 1 | 0.315 | 0.272 | 0.362 | / | 1 | 0.103 | 0.077 | 0.136 | / | 1 | 0.054 | 0.036 | 0.081 | / |

| Poland | 1 | 0.199 | 0.167 | 0.235 | / | 0 | / | / | / | / | 0 | / | / | / | / | 0 | / | / | / | / |

| Saudi Arabia | 1 | 0.835 | 0.737 | 0.902 | / | 1 | 0.367 | 0.269 | 0.478 | / | 1 | 0.342 | 0.246 | 0.453 | / | 1 | 0.126 | 0.069 | 0.219 | / |

| South Africa | 1 | 0.361 | 0.276 | 0.456 | / | 0 | / | / | / | / | 1 | 0.287 | 0.210 | 0.379 | / | 1 | 0.074 | 0.037 | 0.141 | / |

| UK | 2 | 0.396 | 0.371 | 0.421 | .00 | 1 | 0.240 | 0.214 | 0.268 | / | 0 | / | / | / | / | 1 | 0.151 | 0.130 | 0.174 | / |

| US | 19 | 0.351 | 0.252 | 0.466 | 99.29 | 7 | 0.181 | 0.099 | 0.306 | 97.92 | 8 | 0.161 | 0.130 | 0.198 | 82.99 | 8 | 0.128 | 0.079 | 0.201 | 96.04 |

| COVID‐19 | Q = 0.452 | 98.96 | Q = 1.210 | 95.86 | Q = 1.683 | 96.10 | Q = 1.033 | 97.34 | ||||||||||||

| before | 20 | 0.362 | 0.287 | 0.443 | 99.02 | 12 | 0.224 | 0.180 | 0.275 | 85.46 | 9 | 0.177 | 0.127 | 0.241 | 87.59 | 12 | 0.119 | 0.087 | 0.159 | 84.85 |

| after | 27 | 0.324 | 0.253 | 0.404 | 98.68 | 10 | 0.180 | 0.129 | 0.246 | 97.27 | 12 | 0.125 | 0.082 | 0.187 | 97.41 | 11 | 0.082 | 0.041 | 0.155 | 98.58 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

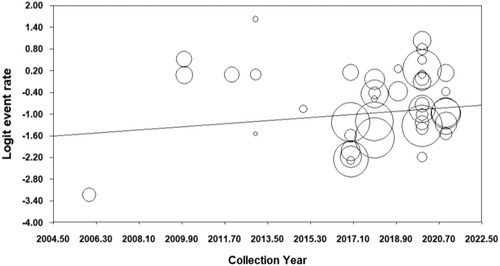

4.5. The trend of anxiety prevalence among graduate students

The data we included were collected between 2005 and 2021, crossed 17 years. The result of fixed‐effect meta‐regression analysis showed that the prevalence of anxiety increased slightly among postgraduates (β = .05, p < .00;Figure 3), especially in severe anxiety (β = .07, p < .00), but the prevalence of mild and moderate anxiety decreased significantly through the year (mild anxiety: β = –.07, p < .00; moderate anxiety: β = –.09, p < .00).

FIGURE 3.

The prevalence of any anxiety among graduates through the year.

To explore the effect of COVID‐19, we compared the prevalence of anxiety between before pandemic (before 202) and after (2020–2021) based on the data collection year. The results showed that there was no significant difference of the anxiety prevalence (any anxiety: 32.4% vs. 36.2%; Q = 0.45, df = 1, p = .50; mild anxiety: 22.4% vs. 18.0%; Q = 1.21, df = 1, p = .27; moderate anxiety: 21.5% vs. 12.5%; Q = 3.19, df = 1, p = .07; severe anxiety: 11.9% vs. 8.2%; Q = 1.03, df = 1, p = .31).

4.6. Prevalence of anxiety mediated by moderators

4.6.1. Study‐level characteristics

Sampling method . Five studies were collecting data with random sampling, 27 studies adopted convenience sampling method, and 18 studies did not report the sampling method. The results of subgroup analysis showed that the studies with nonrandom sampling reported a higher prevalence of moderate anxiety than that with random sampling (any anxiety: 33.6% vs. 2.7%; Q = 3.33, df = 1, p = .07; mild: 2.6% vs. 15.6%; Q = 3.09, df = 1, p = .08; moderate: 13.3% vs. 5.9%; Q = 6.88, df = 1, p = .01; severe: 8.3% vs. 7.5%; Q = 0.01, df = 1, p = .95).

Measures . Although we only included the studies using standardized instruments, the criteria for anxiety were various, which is a potential source of heterogeneity. The result of subgroup analysis showed indicated that DASS‐42 had a higher sensitivity of anxiety, especially for mild and moderate anxiety (any anxiety: 8.0%, Q = 528.2, df = 13, p < .00; mild: 36.0%, Q = 253.0, df = 5, p < .00; moderate: 32.0%, Q = 203.0, df = 6, p < .00); DASS‐21 had a higher sensitivity of severe anxiety than other measures (18.4%, Q = 256.6, df = 6, p < .00). While the results using GAD‐7 is closer to the results of meta‐analysis (any anxiety: 35.3% vs. 34.8%; mild: 31.8% vs. 19.1%; moderate: 13.8% vs. 15.1%; severe: 7.7% vs. 1.3%).

Gender . Sixteen studies compared the anxiety prevalence between female and male; the results of subgroup analysis showed that there was no evidence indicated the significant difference between them (any anxiety: 41.2% vs. 35.5%; Q = 0.37, p = .54; mild anxiety: 22.3% vs. 21.0%; Q = 0.03, p = .86; moderate anxiety: 24.1% vs. 25.6%; Q = 0.03, p = .86; severe anxiety: 15.0% vs. 12.3%; Q = 0.13, p = .72).

Education level . Nine studies reported the anxiety prevalence of master students, and 14 reported doctoral students. The results of subgroup analysis showed that master student suffered similar anxiety to doctoral students, and even higher moderate anxiety (any anxiety: 29.2% vs. 34.2%, Q = 0.36, p = .55; mild anxiety: 23.7% vs. 22.9%, Q = 0.04, p = .85; moderate anxiety: 26% vs. 16.5%, Q = 6.86, p = .01; severe: 14.7% vs. 13.5%, Q = 0.05, p = .82).

Country . The graduate students included in this meta‐analysis covered 12 countries, and the results of subgroup analysis showed that students from Saudi Arabia and India experienced most anxiety and students from China and the United States reported lowest anxiety than that from other countries. The details were shown in Table 2.

5. DISCUSSION

The present meta‐analysis estimated the population prevalence of anxiety disorder among graduate students. And the results indicated that 34.1% of them suffered from different degrees of anxiety. Of these samples included, 19.1% had mild anxiety, 15.1% moderate anxiety, and 1.3% had severe anxiety, which is significantly higher than college students (Ramón‐Arbués et al., 2020) and even higher than the medical student population (Quek et al., 2019). These results are consistent with the previous studies (Evans et al., 2017; Hoying et al., 2020), which revealed the high risk of anxiety disorder among postgraduate students. The factors of anxiety among graduate students are various and universal, such as employment prospects, inability to maintain work–life balance, inability to complete academic tasks on time, high academic competition, and long study period (Woolston, 2019).

Since 2005, countries around the world have recognized the seriousness of anxiety among graduate students and taken relevant measures (Lancet, 2015; Liu & Page, 2016; Mirza & Rahman, 2019), and the prevalence of mild and moderate anxiety decreased slightly. But the evidence suggested an increasing trend in any and severe anxiety; thus, we still need to keep going to prevent this from getting worse. Since the end of 2019, when COVID‐19 appeared, researchers indicated a significant increase of anxiety among among adults (Coley & Baum, 2021), but we found no obviously changing between before and after pandemic. It is mainly owing to the timely measures taken by school (Dempsey et al., 2022).

As the evidence quality, 84% of studies were in medium quality (including L‐M and M‐H), and the studies with low quality tended to reported a higher prevalence of anxiety, and studies with low to moderate quality reported higher prevalence of moderate and severe anxiety than that with high quality. All the studies (24, 48%) assessed into low quality or low to moderate quality adopted convenient sampling, and only two response rates in these studies were over 75% (Al‐Shayea, 2014; Negi et al., 2019). These factors may lead to an overestimate of anxiety prevalence; thus, it is essential to conduct a series high quality of primary in the following research.

We explored heterogeneity with study‐level characteristics and found that DASS‐42 had a higher sensitivity for anxiety, but compared to the results from the present meta‐analysis, the studies using GAD‐7 reported a representative result. Moreover, studies using nonrandom sampling reported an obvious higher prevalence of moderate anxiety than that using random sampling (13.3% vs. 5.9%). Convenience sample is drawn from a source that is conveniently accessible to researchers, but may not be representative of the population at large (Andrade, 2020). Majority (71.43%) studies included in the meta‐analysis were adopted convenience sampling, which may overestimate the prevalence of global graduate students. Thus, it is essential to conduct a large random sample survey from worldwide students in the further research.

Of note, we found that master students reported a similar prevalence of anxiety to doctoral students (29.2% vs. 34.3%), and even a higher prevalence of moderate anxiety (26% vs. 16.5%). Doctoral students always suffer with high pressure and stress; they have to keep a balance between life, work, and study in addition to academic pressure and employment pressure. According to the data from the Organization for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OCED) showed that the average share of younger adults with a tertiary degree has increased from 27% in 2000 to 48% in 2021 among 25‐ to 34‐years‐old (OCED., 2022), and the number of degree holders worldwide will reach 300 million by 2030 (OCED., 2013). This change of talent pool brings lots of pressure to master students, and they may lose their advantage from academic qualification in the job marketing in the future, which pushes them to pursue higher degree.

Besides, we found no obvious change of anxiety prevalence by gender; this was consistent with the previous studies on the mental health of graduate students. As the report from WHO indicated that more women are affected by mental illness than men (WHO, 2017), and based on the survey to 2279 graduate students across 26 countries, Evans et al. (2018) also presented that female suffered more major anxiety than male (43% vs. 34%) (Evans et al., 2018). But the results in the present review found no significant difference. One reason for this is that the source of anxiety in the graduate student population was similar.

In addition, students from Saudi Arabia and India experienced more anxiety than that from China and the United States. One reason is that 33 (66%) of the primary studies included were from China and the United States with 33,169 (83.6%) graduate students, resulting in unrepresentative data of other countries. Cross‐sectional studies with large samples from Saudi Arabia and India are required in the further research.

6. LIMITATIONS

The results of the present study showed that 34.8% of graduates suffered from anxiety, which indicated they were at the risk of mental health. While several limitations remained to consider these findings cautiously. First, although we considered different degree of anxiety symptom (e.g., mild, moderate and severe level), majority of participants were assessed through self‐report inventories rather than gold‐standard diagnostic clinical interviews for anxiety, which may lead to overestimate or underestimate the result. Meanwhile, we found a significant heterogeneity due to the different criteria for anxiety across these self‐rating scales. Second, majority of included studies adopted nonrandom sampling; as mentioned above, this may overestimate the prevalence of moderate anxiety. Lastly, the sample size from 36% studies was under 300, which means these data are not representative. Therefore, high‐quality studies with large sample are needed in the further research.

7. CONCLUSIONS

More than one‐third of graduate students are at the risk of anxiety distress, and this prevalence had a slightly upward since 2005. Although there was no obvious change after the COVID‐19 pandemic occurred, graduate schools should provide efficient program, such as psychological hotlines, mental health education, to prevent mental disorder of graduates for deteriorating. Teachers also need to improve their ability to identify the potential vulnerable students and take actions before their mental distress worse. Students are advised to seek the processional help when they feel depressed or anxious.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

TC and ZJZ conceived and drafted the study. TC and LYC analyzed, interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript, processed, and beautified the pictures and tables. ZJZ critically revised the manuscript. Ting Chi and Luying Cheng equally contributed to the work. All authors have approved the final draft of the manuscript.

ROLE OF FUNDING

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1002/brb3.2909.

INFORMED CONSENT STATEMENT

This project is considered a service evaluation not directly influencing patient care or safety, and therefore, ethics approval was not required. Consent will be requested from all study participants. The final result will be published and freely available.

Supporting information

Table S1. Search strategy and results (retrieval date: November 22, 2022).

Table S2. Items for quality assessment.

Chi, T. , Cheng, L. , & Zhang, Z. (2023). Global prevalence and trend of anxiety among graduate students: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Brain and Behavior, 13, e2909. 10.1002/brb3.2909

Ting Chi and Luying Cheng equally contributed to the work and share the first authorship.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- Abu Ruz, M. E. , Al‐Akash, H. Y. , & Jarrah, S. (2018). Persistent (anxiety and depression) affected academic achievement and absenteeism in nursing students. Open Nursing Journal, 12, 171–179. 10.2174/1874434601812010171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addonizio, F. P. (2011). Stress, coping, social support, and psychological distress among MSW students (PhD). Ann Arbor: University of South Carolina. Retrieved from https://queens.ezp1.qub.ac.uk/login?url= https://www.proquest.com/dissertations‐theses/stress‐coping‐social‐support‐psychological/docview/905163879/se‐2 ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global; Publicly Available Content Database database. (3481178) [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja, T. , & Kumar, A. (2015). Level of anxiety and depression among postgraduate psychology students. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 2(2), 1–7. 10.25215/0202.058 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aleena, S. M. , Ashraf, F. G. T. , Sujith, V. S. , Thomas, S. , Chakraborty, K. , & Deb, S. (2020). Psychological distress among doctoral scholars: Its association with perseverance and passion. Minerva Psichiatrica, 61(4), 143–152. 10.23736/S0391-1772.2.02074-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen, H. K. , Lilly, F. , Green, K. M. , Zanjani, F. , Vincent, K. B. , & Arria, A. M. (2022). Substance use and mental health problems among graduate students: Individual and program‐level correlates. Journal of American College Health, 70(1), 65–73. 10.1080/07448481.202.1725020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almasri, N. , Read, B. , & Vandeweerdt, C. (2022). Mental health and the PhD: Insights and implications for political science. PS‐Political Science & Politics, 55(2), 347–353. 10.1017/S1049096521001396 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al‐Shayea, E. I. (2014). Perceived depression, anxiety and stress among Saudi postgraduate orthodontic students: A multi‐institutional survey. Pakistan Oral & Dental Journal, 34(2), 296–303. Retrieved from https://applications.emro.who.int/imemrf/Pak_Oral_Dent_J/Pak_Oral_Dent_J_2014_34_2_296_303.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, C. (2020). The inconvenient truth about convenience and purposive samples. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 43(1), 86–88. 10.1177/0253717620977000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, S. R. (2020). Elevated psychological distress in undergraduate and graduate entry students entering first year medical school. PLoS ONE, 15(8),. 10.1371/journal.pone.0237008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attia, S. M. , & Shata, N. Z. (2013). Psychological assessment of postgraduate students in one of the academic institutions of Alexandria University, Egypt. Journal of High Institute of Public Health, 43(2), 127–135. 10.21608/JHIPH.2013.19999 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan, B. , Muthaiah, V. P. K. , Peters‐Brinkerhoff, C. , & Ganesan, M. (2022). Stress, anxiety, and depression in professional graduate students during COVID 19 pandemic. Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 10.1080/20590776.2022.2114341 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barreira, P. , Basilico, M. , & Bolotnyy, V. (2018). Graduate student mental health: Lessons from American economics departments . Retrieved from https://www.aeaweb.org/conference/2022/preliminary/paper/iYtb7Gns

- Barton, B. A. , & Bulmer, S. M. (2017). Correlates and predictors of depression and anxiety disorders in graduate students. Health Educator, 49(2), 17–26. Retrieved from https://queens.ezp1.qub.ac.uk/login?url= https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=jlh&AN=132912313&site=eds‐live&scope=site [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein, M. , Hedges, V. L. , Higgins, T. J. P. , & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Introduction to meta‐analysis. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Bozeman, B. , & Gaughan, M. (2011). Job satisfaction among university faculty: Individual, work and institutional determinants. Journal of Higher Education, 82(2), 154–186. [Google Scholar]

- Coakley, K. E. , Le, H. , Silva, S. R. , & Wilks, A. (2021). Anxiety is associated with appetitive traits in university students during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Nutrition Journal, 20(1). 10.1186/s12937-021-00701-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley, R. L. , & Baum, C. F. (2021). Trends in mental health symptoms, service use, and unmet need for services among U.S. adults through the first 9 months of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Transl Behav Med, 11(10), 1947–1956. 10.1093/tbm/ibab030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Cooper, H. , Hedges, V. , L, V. , & C, J. (2009). The handbook of research synthesis and meta‐analysis. New York: Russell Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Cullinan, J. , Walsh, S. , Flannery, D. , & Kennelly, B. (2022). A cross‐sectional analysis of psychological distress among higher education students in Ireland. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 18, 1–9. Online ahead of print. 10.1017/ipm.2022.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey, A. , Lanzieri, N. , Luce, V. , de Leon, C. , Malhotra, J. , & Heckman, A. (2022). Faculty respond to COVID‐19: Reflections‐on‐action in field education. Clinical Social Work Journal, 50(1), 11–21. 10.1007/s10615-021-00787-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan, H. , Gong, M. , Zhang, Q. , Huang, X. , & Wan, B. (2022). Research on sleep status, body mass index, anxiety and depression of college students during the post‐pandemic era in Wuhan, China. Journal of Affective Disorders, 301, 189–192. 10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, D. , Gollust, S. E. , Golberstein, E. , & Hefner, J. L. (2007). Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and suicidality among university students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77(4), 534–542. 10.1037/0002-9432.77.4.534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, J. , Mitchell, K. , Bogardus, J. , Hammerle, K. , Manara, C. , & Gleeson, P. (2020). Mental and physical health behaviors of doctor of physical therapy students. Journal of Physical Therapy Education, 34(3), 227–233. 10.1097/JTE.0000000000000141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, T. M. , Bira, L. , Beltran‐Gastelum, J. , Weiss, L. T. , & Vanderford, N. (2017). Mental health crisis in graduate education: The data and intervention strategies. The FASEB Journal, 31(S1), 75.757–75.757. 10.1096/fasebj.31.1_supplement.75.7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, T. M. , Bira, L. , Gastelum, J. B. , Weiss, L. T. , & Vanderford, N. L. (2018). Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nature Biotechnology, 36(3), 282–284. 10.1038/nbt.4089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck, M. W. , Derakshan, N. , Santos, R. , & Calvo, M. G. (2007). Anxiety and cognitive performance: Attentional control theory. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 7(2), 336–353. 10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J. , Wang, T. , Li, C. C. , Hu, X. P. , Ngai, E. , Seet, B. C. , Cheng, J. , Jiang, X. , & Jiang, X. (2019). Depression prevalence in postgraduate students and its association with gait abnormality. IEEE Access, 7, 174425–174437. 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2957179 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia‐Williams, A. G. , Moffitt, L. , & Kaslow, N. J. (2014). Mental health and suicidal behavior among graduate students. Academic Psychiatry, 38(5), 554–556. 10.1007/s40596-014-0041-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghogare, A. S. , Aloney, S. A. , Spoorthy, M. S. , Patil, P. S. , Ambad, R. S. , & Bele, A. W. (2021). A cross‐sectional online survey of relationship between the psychological impact of coronavirus disease 2019 and the resilience among postgraduate health sciences students from Maharashtra, India. International Journal of Academic Medicine, 7(2), 89–98. 10.4103/IJAM.IJAM_105_20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J. P. , & Thompson, S. G. (2002). Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 21(11), 1539–1558. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoying, J. , Melnyk, B. M. , Hutson, E. , & Tan, A. (2020). Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, stress, healthy beliefs, and lifestyle behaviors in First‐year graduate health sciences students. Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing, 17(1), 49–59. 10.1111/wvn.12415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennifer, B. , Erika, S. A. , Tracy, V. , & Brown, J. D. (2022). Stress, anxiety, depression, and perfectionism among graduate students in health sciences programs. Journal of Allied Health, 51(1), E15–E25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones‐White, D. R. , Soria, K. M. , Tower, E. K. B. , & Horner, O. G. (2022). Factors associated with anxiety and depression among U.S. doctoral students: Evidence from the gradSERU survey. Journal of American College Health: J of ACH, 70(8), 2433–2444. 10.1080/07448481.202.1865975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinman, G. (2001). Pressure points: A review of research on stressors and strains in UK academics. Educational Psychology, 21(4), 473–492. Retrieved from 10.1080/01443410120090849 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk, M. , Karbownik, M. S. , Kowalczyk, E. , Sienkiewicz, M. , & Talarowska, M. (2021). Mental health of PhD students at polish universities‐before the covid‐19 outbreak. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 12068. 10.3390/ijerph182212068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K. , Spitzer, R. L. , Williams, J. B. , Monahan, P. O. , & Löwe, B. (2007). Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Annals of Internal Medicine, 146(5), 317–325. 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancet . (2015). Reforming public and global health in Germany. Lancet, 385(9987), 2548. 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)61145-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. , Song, W. , Zhang, J. Y. , Lu, C. , Wang, Y. X. , Zheng, Y. X. , & Hao, W. N. (2021). Factors associated with mental health of graduate nursing students in China. Medicine, 100(3), e24247. 10.1097/MD.0000000000024247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z. , Kang, D. , Zhang, M. , Xia, Y. , & Zeng, Q. (2021). The impact of the covid‐19 pandemic on Chinese postgraduate students’ mental health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11542. 10.3390/ijerph182111542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. , Wang, L. , Qi, R. , Wang, W. , Jia, S. , Shang, D. , Shao, Y. , Yu, M. , Zhu, X. , Yan, S. , Chang, Q. , & Zhao, Y. (2019). Prevalence and associated factors of depression and anxiety among doctoral students: The mediating effect of mentoring relationships on the association between research self‐efficacy and depression/anxiety. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 12, 195–208. 10.2147/PRBM.S195131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. , & Page, A. (2016). Reforming mental health in China and India. Lancet, 388(10042), 314–316. 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)30373-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. K. , Xiao, S. Y. , Luo, D. , Zhang, J. H. , Qin, L. L. , & Yin, X. Q. (2020). Graduate students' emotional disorders and associated negative life events: A cross‐sectional study from Changsha, China. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 13, 1391–1401. 10.2147/RMHP.S236011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhan, B. , Rajpurohit, A. S. , & Gayathri, H. (2012). Mental health of postgraduate orthodontic students in India: A multi‐institution survey. Journal of Dental Education, 76(2), 200–209. 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2012.76.2.tb05247.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty, M. , & Segal, D. (2015). DSM‐5: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (pp. 965–970). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Matcham, F. , Rayner, L. , Steer, S. , & Hotopf, M. (2013). The prevalence of depression in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Rheumatology, 52(12), 2136–2148. 10.1093/rheumatology/ket169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek Melnyk, B. , Slevin, C. , Militello, L. , Hoying, J. , Teall, A. , & McGovern, C. (2016). Physical health, lifestyle beliefs and behaviors, and mental health of entering graduate health professional students: Evidence to support screening and early intervention. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 28(4), 204–211. 10.1002/2327-6924.12350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milicev, J. , McCann, M. , Simpson, S. A. , Biello, S. M. , & Gardani, M. (2021). Evaluating mental health and wellbeing of postgraduate researchers: Prevalence and contributing factors. Current Psychology, 10.1007/s12144-021-02309-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza, Z. , & Rahman, A. (2019). Mental health care in Pakistan boosted by the highest office. Lancet, 394(10216), 2239–2224. 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)32979-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran, T. P. (2016). Anxiety and working memory capacity: A meta‐analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 142(8), 831–864. 10.1037/bul0000051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negi, A. S. , Khanna, A. , & Aggarwal, R. (2019). Psychological health, stressors and coping mechanism of engineering students. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 24(4), 511–552. 10.1080/02673843.2019.1570856 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- OCED . (2013). OECD skills outlook 2013: first results from the survey of adult skills. Paris: OECD Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- OCED . (2022). To what level have adults studied? In Education at a glance 2022: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, P. , Yang, W. F. , Liu, Y. , Chen, S. , Wang, Y. , Yang, Q. , Wang, X. , Li, M. , Wang, Y. , Hao, Y. , He, L. , Wang, Q. , Zhang, J. , Ma, Y. , He, H. , Zhou, Y. , Long, J. , Qi, C. , Tang, Y. Y. , … Liu, T. (2022). High prevalence and risk factors of dropout intention among Chinese medical postgraduates. Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 27(1), 2058866. 10.1080/10872981.2022.2058866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pervez, A. , Brady, L. L. , Mullane, K. , Lo, K. D. , Bennett, A. A. , & Nelson, T. A. (2021). An empirical investigation of mental illness, impostor syndrome, and social support in management doctoral programs. Journal of Management Education, 45(1), 126–158. 10.1177/1052562920953195 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quek, T. T. , Tam, W. W. , Tran, B. X. , Zhang, M. , Zhang, Z. , Ho, C. S. , & Ho, R. C. (2019). The global prevalence of anxiety among medical students: A meta‐analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(15), 2735. 10.3390/ijerph16152735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadoss, D. , & Horn, J. P. (2022). Second climate survey of biomedical phd students in the time of covid. BioRxiv, 10.1101/2022.01.13.476194 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramón‐Arbués, E. , Gea‐Caballero, V. , Granada‐López, J. M. , Juárez‐Vela, R. , Pellicer‐García, B. , & Antón‐Solanas, I. (2020). The prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress and their associated factors in college students. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 17(19), 7001. 10.3390/ijerph17197001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reevy, G. M. , & Deason, G. (2014). Predictors of depression, stress, and anxiety among non‐tenure track faculty. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 701. 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, L. , Lee, S. , Jenkins, P. , Arbet, J. , Carrington, S. , Hoon, S. , Purcell, S. K. , & Nodine, P. (2021). A survey of mental health in graduate nursing students during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Nurse Educator, 46(4), 215–222. 10.1097/NNE.0000000000001013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, R. (1979). The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological bulletin, 86(3), 638–641. [Google Scholar]

- Shadowen, N. L. , Williamson, A. A. , Guerra, N. G. , Ammigan, R. , & Drexler, M. L. (2019). Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms among international students: Implications for university support offices. Journal of International Students, 9(1), 129–149. 10.32674/jis.v9i1.277 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shete, N. A. , & Garkal, K. D. (2015). A study of stress, anxiety, and depression among postgraduate medical students. CHRISMED Journal of Health and Research, 2(2), 119–123. 10.4103/2348-3334.153255 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Talapko, J. , Perić, I. , Vulić, P. , Pustijanac, E. , Jukić, M. , Bekić, S. , Meštrović, T. , & Škrlec, I. (2021). Mental health and physical activity in health‐related university students during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Healthcare, 9(7), 801. 10.3390/healthcare9070801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa, A. , Giannuzzi, R. , Sollazzo, F. , Petrongolo, L. , Bernardini, L. , & Daini, S. (2013). Psychiatric emergencies (part I): Psychiatric disorders causing organic symptoms. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, 17(Suppl 1), 55–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuuren, C. J. , Bodenstein, K. , & Oberholzer, M. (2021). Exploring the psychological well‐being of postgraduate accounting students at a South African university. South African Journal of Accounting Research, 35(3), 219–238. 10.1080/10291954.2021.1887440 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P. , Xiong, Z. , & Yang, H. (2018). Relationship of mental health, social support, and coping styles among graduate students: Evidence from Chinese universities. Iran J Public Health, 47, 689–697. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. , Chen, H. G. , Liu, L. , Liu, Y. , Zhang, N. , Sun, Z. H. , Lou, Q. , Ge, W. , Hu, B. , & Li, M. Q. (2020). Anxiety and sleep problems of college students during the outbreak of COVID‐19. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 588693. 10.3389/fpsyt.202.588693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates . Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254610/WHO‐MSD‐MER‐2017.2‐eng.pdf#:~:text=Common%20mental%20disorders%20refer%20to%20a%20range%20of,from%20depressive%20disorder%2C%20and%203.6%25%20from%20anxiety%20disorder

- Woolston, C. (2019). PhDs: The tortuous truth. Nature, 575, 403–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H. L. , Li, H. Y. , Li, X. X. , Su, W. J. , Tang, H. X. , Yang, J. , Deng, Z. , Xiao, L. , & Yang, L. X. (2022). Psychological health and sleep quality of medical graduates during the second wave of COVID‐19 pandemic in post‐epidemic era. Frontiers in Public Health, 1, 876298. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.876298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, H. , Wen, S. , Li, M. , Li, Z. , Fangbiao, T. , Wu, X. , Yu, Y. , Meng, H. , Vermund, S. H. , & Hu, Y. (2020). Social distancing among medical students during the 2019 coronavirus disease pandemic in China: Disease awareness, anxiety disorder, depression, and behavioral activities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 5047. 10.3390/ijerph17145047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, R. K. , Baral, S. , Khatri, E. , Pandey, S. , Pandeya, P. , Neupane, R. , Yadav, D. K. , Marahatta, S. B. , Kaphle, H. P. , Poudyal, J. K. , & Adhikari, C. (2021). Anxiety and depression among health sciences students in home quarantine during the COVID‐19 pandemic in selected provinces of Nepal. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 580561. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.580561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaow, C. Y. L. , Teoh, S. E. , Lim, W. S. , Wang, R. S. Q. , Han, M. X. , Pek, P. P. , Tan, B. Y. , Ong, M. E. H. , Ng, Q. X. , & Ho, A. F. W. (2022). Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and post‐traumatic stress disorder after cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Resuscitation, 170, 82–91. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakeri, M. M. D. , De La Cruz, A. P. , Wallace, D. P. , & Sansgiry, S. S. P. (2021). General anxiety, academic distress, and family distress among doctor of pharmacy students. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 85(10), 1031–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W. , Lu, X. , Kang, D. , & Quan, J. (2022). Impact of postgraduate student internships during the COVID‐19 pandemic in China. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 790640. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.790640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S. J. , Wang, L. L. , Qi, M. , Yang, X. J. , Gao, L. , Zhang, S. Y. , Zhang, L. G. , Yang, R. , & Chen, J. X. (2021). Depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation in Chinese university students during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 669833. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.669833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. C. , An, J. , Cheng, M. W. , Sheng, L. Y. , Rui, G. Q. , Mahefuzha, M. , & Yao, J. (2018). Confirmatory factor analysis of the beck anxiety inventory among Chinese postgraduates. Social Behavior and Personality, 46(8), 1245–1254. 10.2224/sbp.6923 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Search strategy and results (retrieval date: November 22, 2022).

Table S2. Items for quality assessment.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.