Abstract

Patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models, in which tumor tissues from patients are implanted into immunocompromised or humanized mice, have shown superiority in recapitulating the characteristics of cancer, such as the spatial structure of cancer and the intratumor heterogeneity of cancer. Moreover, PDX models retain the genomic features of patients across different stages, subtypes, and diversified treatment backgrounds. Optimized PDX engraftment procedures and modern technologies such as multi-omics and deep learning have enabled a more comprehensive depiction of the PDX molecular landscape and boosted the utilization of PDX models. These irreplaceable advantages make PDX models an ideal choice in cancer treatment studies, such as preclinical trials of novel drugs, validating novel drug combinations, screening drug-sensitive patients, and exploring drug resistance mechanisms. In this review, we gave an overview of the history of PDX models and the process of PDX model establishment. Subsequently, the review presents the strengths and weaknesses of PDX models and highlights the integration of novel technologies in PDX model research. Finally, we delineated the broad application of PDX models in chemotherapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and other novel therapies.

Subject terms: Cancer models, Cancer therapy

Introduction

In the realm of cancer treatment, the advent of targeted therapies and immunotherapies has greatly enriched the arsenal against cancer and provided patients with better therapeutic outcomes and milder side effects. Nonetheless, many problems have restrained improvement in the prognosis of cancer patients. First, only a small proportion of cancer patients benefit from the drugs. Therefore, robust biomarkers are necessary to accurately select the patients who will respond to or resist these therapies. However, current biomarkers and signatures are insufficient to reflect the genuine cancer status, let alone classify the patients accurately.1 Besides, the patients who respond to these therapies must deal with resistance and cancer recurrence.2 They need guidance regarding the choice of next-line therapies, which relies on the dynamic detection of the cancer status.3 Moreover, the remaining cancer patients are in urgent need of new pharmaceuticals. Although numerous prospective drugs against cancer have been developed and shown promising therapeutic efficacy in vitro, only a few of them have been proven safe and effective in the context of complex in vivo experiments.4 These problems are largely due to the lack of research tools to reveal the genuine status of cancer in real-world patients.

Oncogenesis is a dynamic process that results from many intertwined factors. During cancer progression, genetic and epigenetic aberrations lead to distinct genomic landscapes among patients, and different treatments further fuel genomic evolution and remodeling.5 Moreover, intratumor spatial and temporal heterogeneity added complexity to cancer, which refers to the diverse cancer cell phenotypes and different states of cancer cells within a single patient caused by cancer evolution and anti-cancer treatment selection.6 Besides, cancer spatial architecture is shaped by the interaction among different cell components and tissue structures, such as vascular distribution. Grasping these fundamental characteristics and recapitulating such evolutionary characteristics of human cancer is the critical prerequisite for cancer models to accurately reflect the response cancer and tackle the cancer treatment challenges.

Accordingly, animal models such as genome-edited mouse models, patient-derived organoids, and patient-derived xenografts (PDX) have been used to study cancer biology and capture the cancer landscape.7 Genetically engineered mice (GEM) models and GEM-derived allografts are suitable for studying the role of specific genes in cancer initiation and development. However, such models cannot reflect diverse driver mutations and extensive genomic alterations observed in human cancer. Chemical carcinogen-induced mouse models are time-honored models that serve as a tool to study cancer etiology and cancer biology. However, these models induce unpredictable cancer landscapes that are hard to repeat, let alone the effects of different dosing protocols and animal strains. Besides, in the animal-derived cancer models mentioned above, their interspecies inconsistency with human cancer leads to underlying distinct protein functions and oncogenesis mechanisms. Therefore, human cancer originated models are more reliable for studying therapies that rely on complex intracellular pathways and intercellular interactions. Human cancer cell lines and cell line-derived xenografts have been widely used because of their consistency, availability, and cost-effectiveness. Besides, the 3D culture of in vitro cancer cell lines partly mimics the in vivo structure of cancer, such as the different morphological and biological features of different cell layers. However, they only represent the cancers with specific gene aberration under a settled genomic background. Besides, these models lack tumor heterogeneity and fall short of recapitulating tumor architecture. Consequently, the drug response of these models seldom represents the authentic response of patients, and their consistency with clinical trials in drug response is limited.8

To faithfully reflect the landscape of human cancer, advanced preclinical models have been exploited. Microfluidic models facilitate the development of tumor-on-chip, a type of in vitro platform that accurately emulates various properties in the cancer microenvironment, such as the changes of glucose or oxygen availability at different positions in tumor structure. Such platforms enable researchers to manipulate many factors that may affect cancer growth and explore the effect of these factors on cancer.9 Although tumor-on-chip can emulate more and more components in the cancer microenvironment, such as microvascular structure,10 their consistency with cancer patients has not undergone rigorous examination. Besides, limited by technology support, tumor-on-chip has a long way to go before it gets popularized in cancer research centers worldwide. Comparatively, models that utilize samples derived from cancer patients remain the most plausible and accessible choice in reflecting genuine cancer structure. Patient-derived organoids (PDO), which are cultured from cancer cells from patients, serve as a cost-effective tool to retain cancer information. Thanks to technical support such as 3D co-culture assays, researchers seek to recapitulate cancer cell-stromal interactions in PDO models.11 However, in vitro models are not ideal for novel therapy testing because they cannot reflect many in vivo properties, such as pharmacokinetics performance, when it comes to preclinical drug testing. The PDX models are established by transplanting fresh tumor tissue resected from human cancer into mice.12 Comparatively, the PDX model excels in reflecting the characteristics of cancer and simulates tumor progression and evolution in human patients. The PDX model produces the most convincing preclinical results and is considered one of the most promising models to handle the conundrum troubling clinicians, such as identifying prognosis biomarkers, exploring the effect of intratumor heterogeneity on tumor progression, and evaluating new drugs.13

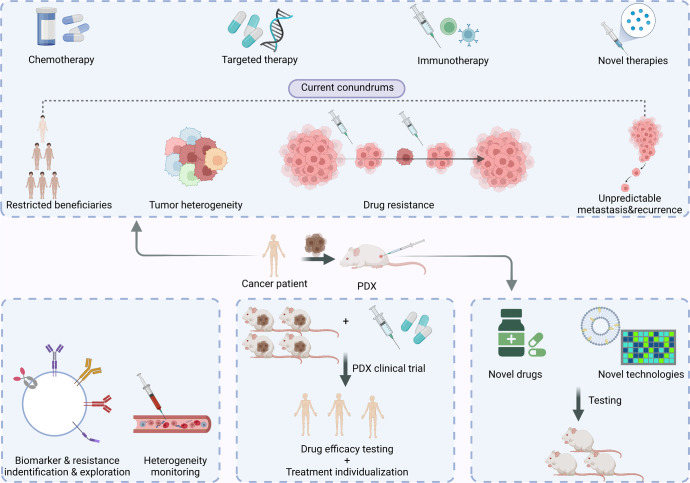

In this review, we delineated the establishment process of PDX models and the advantages and inadequacies of PDX models. Furthermore, we summarized how the current technologies boost the application of PDX models (Fig. 1). Finally, we focused on the role of PDX in studying chemotherapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, as well as other novel treatments against cancer. PDX models can tackle various problems, such as testing the efficacy of novel drugs, screening drug-sensitive and drug-resistant patients, and exploring drug-resistance mechanisms. This work reviews the crucial role of PDXs in the study of cancer and sheds light on the future application of PDX models in developing therapeutics against cancer.

Fig. 1.

PDX in the new era of cancer treatment. This figure shows the current conundrums of cancer treatment including restricted beneficiaries, tumor heterogeneity, drug resistance as well as tumor metastasis and recurrence, and shows the versatile functions of PDX in developing therapeutics against cancer

A brief history of PDX models

PDX models have gone through a history of “rediscovery”. The first reported patient-derived xenograft that accorded to the definition of PDX models could be traced back to 1969 when Rygaard and Povlsen removed colon adenocarcinoma from a patient and planted the tumor fragments into nude mice.14 Later, researchers proved that when treated with chemotherapies, PDX models showed comparable responses as their counterpart patients.15 Even though discussion about the techniques of PDX model construction persisted, the unsatisfying transplantation rate of PDX models limited their application. Moreover, because researchers lacked anti-cancer drug choices back then, the function of the PDX model was confined to predicting the drug efficacy for the patient it was derived from. In contrast, more and more cancer types had in vitro cultured human cancer cell lines. Because of their consistency, cost-effectiveness, and accessibility, cell line-derived xenograft models became and have remained the workhorse of evaluating novel anti-cancer compounds.

Nonetheless, researchers gradually realized the inadequacy of cancer cell lines in studying anti-cancer drug efficacy. In 2001, Johnson et al. reported that the consistency of drug response between cell-lined derived models and clinical trials was far from satisfying.8 The high attrition rate in pharmaceutical industries has raised dissatisfaction.16 In the meantime, researchers reported similar responses to chemotherapy in corresponding patients and PDX models.17 Moreover, researchers started to use histopathology and PCR-based technologies to validate the conformity of patients and PDX models. In 2006, Manuel Hidalgo’s group established a pancreatic PDX platform for drug screening and biomarker discovery, which was one of the pioneers.18 In the 2010s, the optimization of PDX establishment technologies and the popularization of sequencing technologies have boosted the resurgence of PDX models. A colorectal cancer PDX platform was utilized to identify HER-2 inhibitors to treat cetuximab-resistant patients, which is the paradigm to show the role of PDX models in targeted therapy.19 In 2015, Clohessy et al. developed the concept of “mouse hospital”, which refers to in vivo drug testing in models that recapitulate different cancer subtypes before heading into clinical trials.20 Although they mainly referred to GEM models when bringing up the concept, PDX models gradually gained wide acceptance in drug testing henceforth. In 2016, Gao established about 1000 PDX models and tested drug responses on them following clinical trial design, which is a paradigm of the patient derived clinical trial (PCT).13 The wide application of sequencing further validated the genomic consistency between patients and PDX models and facilitated preclinical studies of targeted therapies in PDX models. From then on, more and more platforms validated that PDX models recapitulated the cancer landscape faithfully. Therefore, in the era of immunotherapy and targeted therapy, PDX models have been widely used in preclinical drug tests. Instead of merely serving as the “avatar” of their corresponding donors, they can guide clinical decisions by predicting the molecule signatures that signify sensitivity to the drugs. A timeline highlighting the recent progress of PDX models is summarized in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The brief timeline of milestones in PDX study

PDX models: strengths and weaknesses

PDX is currently the most effective preclinical model for phenocopying cancer intratumor heterogeneity, preserving intrinsic tumor architectures, and studying drug response and resistance. Current PDX models have been applied to a wide variety of cancer types (Table 1).

Table 1.

PDX models and biobanks of different cancer types

| Reference | Cancer type (cancer subtype) | Sample number (success rate) | Factors contributing to successful PDX engraftment | Relationship between successful engraftment and patient prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hu et al.242 | Hepatocellular carcinoma (N/A) | 103 (40.6%) | Lack of encapsulation, poor tumor differentiation, large size, and overexpression of cancer stem cell biomarkers | Independent predictor for overall survival and post-resection tumor recurrence |

| Shin et al.243 | Ovarian cancer (serous, clear, endometrioid, mucinous, MMMT, brenner) | 61 (47%) | Tumor grade, inflammation- and immune-response-related genes | Faster PDX growth rate associated with poor prognosis of ovarian cancer and cervical cancer patients |

| Cervical and vaginal cancer (squamous, adeno) | 29 (64%) | |||

| Uterine cancer (endometrioid, serous, clear, carcinosarcoma) | 18 (56%) | |||

| Pham et al.244 | Pancreatic cancers (ductal adenocarcinoma, mucinous adenocarcinoma, squamous, solid pseudopapillary, etc.) | 118 (59%) | N/A | N/A |

| Duodenal cancers (N/A) | 25 (86%) | |||

| Biliary ductal cancers (N/A) | 17 (35%) | |||

| Kawashima et al.245 | Acute myeloid leukemia (M0-M6, AML with MRC, tAML from MPN) | 105 (66%) | N/A | Lower event-free survival rate and poor responses to chemotherapy. |

| Moy et al.246 | Esophagogastric cancer (diffuse, mixed, intestinal) | 98 (N/A) | Metastases, stage IV disease, HER2 expression, intestinal subtype | N/A |

| Jung et al.28 | Lung squamous cell carcinoma (N/A) | 82 (59%) | Tumor engraftment failure was correlated with the preoperative chemotherapy initiation. | Poor overall survival or relapse free survival. |

| Cybula et al.247 | High-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (N/A) | 33 (77%) | N/A | Early tumor recurrence. |

| Peille et al.248 | Gastric adenocarcinoma (Intestinal, Diffuse, Mixed) | 27 (27%) | Intestinal subtype | N/A |

| Ryu et al.249 | Breast cancer (HR + /HER2-, HR + /HER2 + , HR-/HER2 + and triple-negative breast cancer) | 20 (17.5%) | Advanced cancer stages | Poor disease-free survival, overall survival, and chemotherapy resistance |

| Jo et al.250 | Lung cancer (small cell lung cancer, non-small-cell lung cancer) | 55 (22%) | N/A | Chemotherapy-resistance |

| Xu et al.251 | Liver cancer (hepatocellular cancer, metastatic liver cancer) | 20 (38.5%) | TNM stage, lymph node metastasis, peripheral blood CA19-9 level, tumor size. | Poor median overall survival in hepatocellular cancer. |

| Wu et al.252 | Malignant pleural mesothelioma (epithelioid, sarcomatoid, biphasic) | 20 (40%) | N/A | Poor survival. |

| Bonazzi et al.175 | Endometrial cancer (carcinosarcoma, endometrioid, mixed endometrioid, and clear cell, etc.) | 18 (33%) | N/A | Shorter disease specific survival. |

| Strüder et al.253 | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (N/A) | 16 (29%) | Engraftment rate was lower and growth delayed for endoscopic biopsies. | N/A |

| Kamili et al.254 | Neuroblastoma | 9 (64%) | Orthotopic inoculation | Poor outcome |

| Miyamoto et al.255 | Cervical cancer (Adenocarcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma) | 11 (50%) | Large tumor size, high serum squamous cell carcinoma antigen and carbohydrate antigen 125 levels, and advanced FIGO stages. | Clinically poor prognoses |

| Schütte et al.173 | Colorectal cancer (N/A) | 59 (60%) | N/A | N/A |

| Tanaka et al.256 | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B- acute lymphoblastic leukemia, T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia) | 57 (93.3%) | N/A | N/A |

| Tew et al.257 | Central nervous system metastasis (Adenocarcinoma, Squamous cell carcinoma, Invasive ductal carcinoma, etc.) | 39 (84.8%) | N/A | N/A |

| Chapuy et al.258 | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (activated B-cell (ABC)-type tumors, germinal B-cell type tumors, and plasmablastic lymphoma) | 9 (32%) | N/A | N/A |

| Baschnagel et al.259 | Small cell lung cancer brain metastases (Adenocarcinoma, sarcomatoid carcinoma) | 9 (64%) | N/A | N/A |

| Elst et al.260 | Advanced penile cancer (Usual, warty-basaloid, sarcomatoid) | 11 (61%) | N/A | N/A |

| Lilja-Fischer et al.261 | Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (N/A) | 12 (35%) | N/A | N/A |

| Zhang et al.262 | B-cell lymphoma (Mantle cell lymphoma, Burkitt’s lymphoma, Follicular lymphoma, Marginal zone lymphoma, etc.) | 16 (N/A) | N/A | N/A |

| Chamberlain et al.263 | Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (N/A) | 1 (N/A) | N/A | N/A |

| Lin et al.264 | Dedifferentiated endometrial carcinoma (N/A) | 1 (N/A) | N/A | N/A |

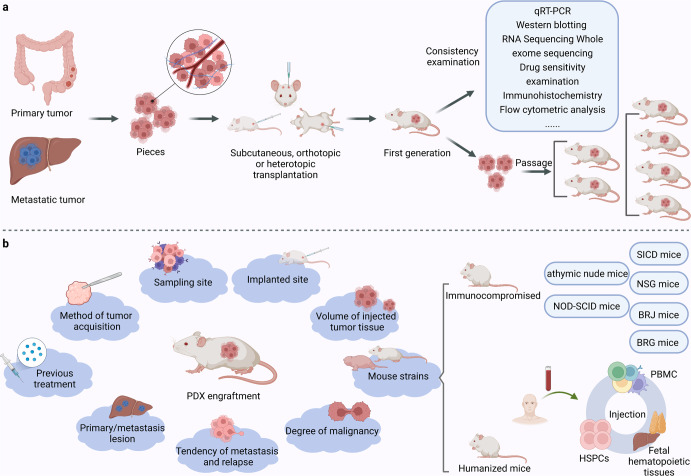

PDX establishment

To establish PDX models, primary or metastatic tumors are cut into pieces and transplanted with maintained tissue structures. The tumor pieces can be implanted subcutaneously, orthotopically, or heterotopically into the intracapsular fat pad, the anterior compartment of the eye, or under the renal capsule12,21 (Fig. 3). Different tumor types take different duration to establish PDX, ranging from a few days to several months. Generally, when the tumor reaches 1-2cm3 (first generation), it could be cut off, segmented, and reimplanted for passage. Moreover, the time of PDX establishment gradually stabilizes at 40–50 days with passages.21,22 To avoid tumor engraftment rejection in mouse models, conventional PDX models are typically created using immunocompromised mice, such as athymic nude mice, severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice, non-obese diabetic-severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD-SCID) mice, NOD-SCID-/IL2λ-receptor null (NSG) mice, BALB/cRag2 null/ IL2λ-receptor null (BRG) mice and Rag-2 null/Jak3 null (BRJ) mice.22,23 Different mouse strains have various degrees of immunosuppression, and they are thus endowed with different engraftment rates, which are higher in more immunocompromised mice (BRG/BRJ > NSG > NOD/SCID > SCID > nude).12,22,24

Fig. 3.

The establishment of PDX. a Showing the establishment process of PDX. b Showing the factors affecting the engraftment rate and the categories of PDX mice

PDX engraftment is affected by a series of factors. Katsiampoura et al. discovered that the method of tumor acquisition, previous treatment, and sampling site could influence the process of establishing a PDX25 (Fig. 3). Besides, the origin of the donor’s tumor cells, such as the primary lesion or metastasis, can affect the success rate.26,27 In a study of establishing lung cancer PDX models, researchers discovered that the engraftment rate hinged on the chemotherapy history of the patients.28 A study established a liver cancer PDX platform and discovered that NSG mice with partial hepatectomy before engraftment had better engraftment ability.29 In acute lymphoblastic leukemia PDX models, Richter et al. discovered that the leukemic cell subtypes could determine the site preference and growth speed of xenografts.30 The more aggressive high-grade and ER-negative breast cancers were found to have a higher engraftment rate.31 Furthermore, the engraftment of the residual tumor after neoadjuvant chemotherapy may identify a subgroup of patients with a higher risk of recurrence.32 Interestingly, the proportion of stroma in the tumor graft also affected the engraftment rate. Scarce stroma could lead to alimentary deficiency after tumor implantation.33 Besides, technical details during the transplantation process, such as the volume of injected tumor tissue, the implanted site, and the mouse strains, would contribute to the success rate.12,33 Despite many factors reported, the optimized protocol is still under debate and may change along with different cancer types.

In addition to the intrinsic components of the tumor microenvironment (TME), tumor-immune interaction is also implicated in cancer patient survival and tumor behaviors, which cannot be restored in general PDX. To this end, PDX with functional human immune systems could be a powerful tool for in vivo tumor immunology and immunotherapy research. Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), or fetal hematopoietic tissues are resources for engraftment34 (Fig. 3). In irradiated NSG or BRG mice, human hematopoietic stem cell engraftment could lead to the development of T cells, B cells, myeloid dendritic cells, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells.35–37 Engraftment of human fetal liver and thymus tissue under the renal capsule of NOD-SCID mice also generated adaptive and innate immune responses.38 Engraftment of human PBMCs is readily available but has some remaining limitations, mainly due to the xenoreactivity of the human cells against mouse antigens. However, relatively high engraftment has been performed in BRG mice.39,40 Highly immunodeficient mice engrafted with functional human immune systems (more than 25% human CD45 + cells in the peripheral blood) and patient-derived tumor fragments are named humanized PDX.41–43

An ideal preclinical model should fully capture and maintain all the characteristics of the parental tumor and reconstruct the real tumor-immune interaction to enable in-depth insight into tumor evolution and be a silver bullet for precise drug research. Existing PDX models have shown satisfactory performance but still need to improve in several respects.

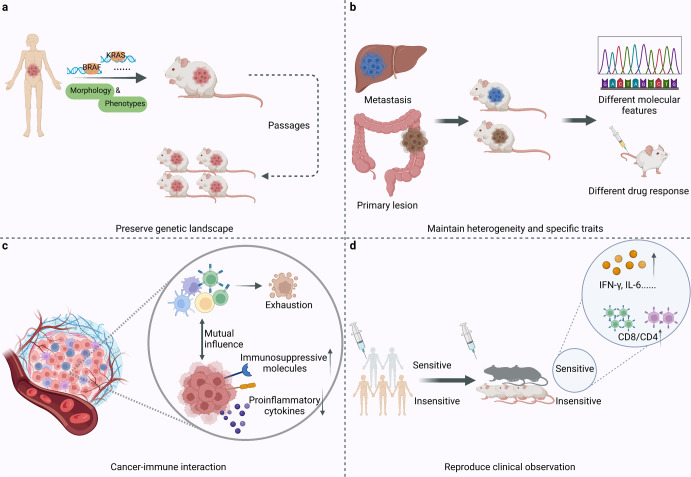

Recapitulating parental characteristics and simulating actual tumor-immune interaction

Many studies have demonstrated that PDX could preserve the histopathology and genetic landscape of the parental tumor, and the clonal compositions in PDX paralleled the genetic heterogeneity.17,44–46 Orthotopic transplantation of glioblastoma (GBM) could retain the key phenotypes, molecular characteristics, and the similar morphology and invasion pattern.47 Mutation frequencies of commonly mutated genes in cancer, including KRAS, BRAF, TP53, PIK3CA, CTNNB1, and EGFR, were consistent with clinical data in PDX models.25,48 Zhao et al. treated patients and PDX models separately with a novel KRAS G12C inhibitor to assess the emergent genetic alteration after treatment, which was similar in both groups.49 PDX models can also recognize cancer subtypes based on molecular characteristics. In the context of breast cancer PDX models, Georgopoulou et al. identified 13 cellular phenotypes of breast cancer by single-cell mass cytometry. The phenotypes determined in treatment-naïve models can predict the response to anti-cancer therapies such as chemotherapies and targeted kinase inhibitors. Moreover, mass cytometry uncovered that in a single PDX model, cells with different oncogene signaling showed different responses to targeted therapies.50 Besides, the well-acknowledged consensus molecular subtypes (CMS) of colorectal cancer (CRC) have been recapitulated in PDX models.51 PDX could maintain high genomic stability through at least the first 10 passages, ensuring a long enough experiment window52 (Fig. 4). PDX models can also recapitulate the features of infection-related cancers. For instance, a hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) PDX model cohort in China recapitulates HBV core antigen expression.53

Fig. 4.

The advantages of PDX over other models. a PDX could preserve the genetic landscape, morphology and phenotype of the parental tumor. b PDX could maintain tumor heterogeneity and specific traits of metastases. c The realization of cancer-immune interaction in humanized PDX: human immune system tends to be educated by tumor and exhibits an exhausted status over time, and tumors maintain evolution and heterogeneity to survive with upregulated immunosuppressive molecules and decreased production of human pro-inflammatory cytokines. d PDX could reproduce the drug response observed in patients

PDX models maintain genetic profiles and intratumor heterogeneity, making them powerful tools for studying the different states among different regions in the primary lesion and metastases.45 For instance, Braekeveldt et al. dissected a neuroblastoma tumor from a patient and separately implanted ten tumor fragments into ten mice. Interestingly, the xenografts showed growth speed difference and transcription difference, and patient subtypes identified according to the gene clusters of these PDX models showed distinct prognoses.54 Wang et al. established PDX models from CRC liver metastasis and confirmed the fidelity to recapitulate the properties of their parental tumors. Despite the overall similarity, several mutations were only observed in the metastases, which may indicate the trigger of distant metastasis.46 Dahlmann et al. established PDX models from CRC peritoneal metastasis and characterized their molecular features and responses to targeted therapies.55 Cho et al. established PDX models from CRC primary lesions and metastases and compared their responses to drugs. They discovered that metastasis-derived PDX models respond to targeted therapies differently, possibly resulting from subclonal mutations acquired during tumor metastasis.56 Moreover, to replicate the spatial heterogeneity, Zhang et al. transplanted metastatic tumor tissue orthotopically into the same organ as the transplantation site, and the further drug efficacy test reflected the drug response of metastasis more faithfully.57

In addition, PDX models present an unprecedented chance to study the cancer-immune interaction in animal models. The vascular structure and antigen presentation machinery in PDX models were conserved to ensure T cell homing to the tumor and effective antigen recognition.58 Besides, PDX models retained MHC peptidome similarity through subsequent passages.59 A mutual influence relationship exists between tumors and the human immune system in clinical practice. Tumors maintain evolution and heterogeneity to survive, and immune cells are partially exhausted by tumor education. The same pattern is observed in humanized PDX. The human immune system tends to be educated by tumor. It exhibits an exhausted status over time, especially in cytotoxic immune cells and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) rather than peripheral T cells.60 Cancer cells acquired lymphocytes’ membrane immune regulatory proteins such as CTLA-4 via trogocytosis.61 Meanwhile, changes in tumor gene expression occur, which are reflected by upregulated immunosuppressive molecules and decreased production of human pro-inflammatory cytokines.62 This simulation of tumor-immune interaction in the human body allows researchers to understand better the mechanisms of tumor evolution, which was previously confined by the lack of clinical biopsies from various stages before time. One difficulty, however, is that human immune cells are not permanent in PDX because of the lack of genes encoding the cytokines necessary for human immune cells. To tackle this problem, Duy Tri Le, et al. transplanted a fresh, undisrupted piece of solid tumor into mice and obtained TIL-derived PDX.63 This unique PDX based on TIL in tumors does not require in vitro cell expansion and cytokine maintenance to achieve long-term immune system reconstitution. Graft versus host disease (GvHD) is another challenge that recognizes and attacks murine tissue as a foreign body, shortening the experimental window and impeding immunotherapy research. Correspondingly, many studies have generated specific PDX models with deficient MHC to eliminate GvHD.64–66

In addition to maintaining genomic heterogeneity, translational PDX models are supposed to reproduce the drug response observed in patients. A combination immunotherapy of nivolumab and ipilimumab significantly increased IFN-γ and IL-6 production and decreased the CD4/CD8 ratio in the PDX model, resulting in an immunoreactive TME as expected and clinically observed60 (Fig. 4). A plethora of studies reported the uniformity of treatment outcomes in PDX and the respective clinical data, consistent with its good mimicry of the parental tumor.67,68 A neoadjuvant therapy combining of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and radiotherapy had a concordant therapeutic effect in CRC patients and PDX.69 Several large-scale PDX clinical trials investigated drug responses and resistance mechanisms, and their findings confirmed the reproducibility and clinical translatability of PDX,13,48,70 indicating that PDX could retain therapeutic accuracy and is a functional clinically relevant model.44 Clinical trials aiming to determine the reliability of PDX for precision treatment, explore the mechanisms of resistance, or achieve other research objectives are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

PDX related clinical trials

| Cancer type | PDX type | Objective | Trial design | Phase | Current status | NCT number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) | − | Determine the reliability of PDX for treatment response for individual TNBC patient | Create PDX mouse models with tissues collected pre- and post- neoadjuvant treatment | − | Completed | NCT02247037 |

| Breast cancer | − | Explore the mechanisms of high recurrence after neoadjuvant therapy | Generate PDX and organoids from breast cancer patients with residual disease after neoadjuvant therapy | − | Recruiting | NCT04703244 |

| Metastatic TNBC (mTNBC) | Mini-PDX | Investigate the efficacy of guided treatment based on Mini-PDX in mTNBC patients | Personalized treatment guided by mini-PDX and RNA sequencing | II | Recruiting | NCT04745975 |

| Bladder cancer, Gastric cancer, Liver cancer, Lung cancer | − | Develop and characterize over 200 PDXs of different cancers and across different races | Tumor tissue samples of patients diagnosed with bladder cancer, lung cancer, gastric cancer or liver cancer were collected to establish PDXs | − | Recruiting | NCT04410302 |

| Sarcoma | Nude mice | Develop a platform of PDX for soft tissue sarcomas | Establish sarcoma PDX and treat with radiotherapy and chemotherapy for translational research | − | Recruiting | NCT02910895 |

| Prostate cancer | Mini-PDX | Guide treatment for patients resistant to abiraterone, enzalutamide or other new second-generation anti-androgenic drugs | Use the Second-generation sequencing and Mini-PDX to make personalized treatment and explore the clinical consistency | − | Recruiting | NCT03786848 |

| Gastric cancer | zebrafish PDX | Evaluate the consistency of PDX for predicting therapeutic effect | Observe the response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patient and corresponding PDX | − | Not yet recruiting | NCT05616533 |

| Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) | − | Generate a biobank of PDX representing the different subgroups of HNSCC | Establish PDX with primary and recurrent tumor tissues, explore new biomarkers, novel therapy and drug resistance | − | Recruiting | NCT02572778 |

| Breast Cancer | − | Establish a PDX platform of ER + , HER2- breast cancer | Develop novel treatment strategies and dissect signaling pathways underlying drug sensitivity and resistance | − | Completed | NCT02752893 |

| Osteosarcoma | − | Provide patients with individualized treatment options with the help of PDX | Molecular profiling and in vivo drug testing | − | Not yet recruiting | NCT03358628 |

| Metastatic solid tumors | Chick embryos | Use novel PDX platform to guide hyper-personalized medicine | Evaluate anti-tumor effects by ultrasound imaging and histology | − | Recruiting | NCT04602702 |

| Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (mNSCLC) | Humanized CD34 PDX | Comparison of clinical response and in-vivo anti-tumor response | Patients and corresponding PDXs expressing PD-L1 after failure of platinum-based combination chemotherapy will be treated with Pembrolizumab | IV | Recruiting | NCT03134456 |

| Relapsedmantle cell lymphoma | − | Determine the feasibility of guiding personalized treatment by PDX | Patients that respond to previous treatment but experience relapse or disease progression receive treatment based on the results of the PDX | Early I | Recruiting | NCT03219047 |

| Colorectal cancer, High-grade serous ovarian cancer, TNBC | − | Evaluate the utility of PDX as predictor to direct the use of chemo- and targeted therapies | Molecular profiling & in vivo drug testing in PDX and organoid cultures | − | Recruiting | NCT02732860 |

| Breast Cancer | Nude mice | Develop PDX from tumor samples from surgical specimens of patients | Genetic analysis will be performed in patients who got a successful PDX | − | Recruiting | NCT04133077 |

| Pancreatic cancer | Mini-PDX | Provide precision diagnosis and treatment for different stages of cancer patients | Generate Mini-PDX and explore the best medicine by RNA sequencing and drug sensitivity test. | − | Recruiting | NCT04373928 |

| HNSCC | − | Develop a biobank of HNSCC PDX and guide chemotherapy | Genomic sequencing and drug sensitivity testing | − | Completed | NCT02752932 |

| Urogenital cancer | Chick embryos | Test PDX efficiency and guide individualized treatment | Give certain medicines to PDX and determine the potentiality of each drug | − | Completed | NCT03551457 |

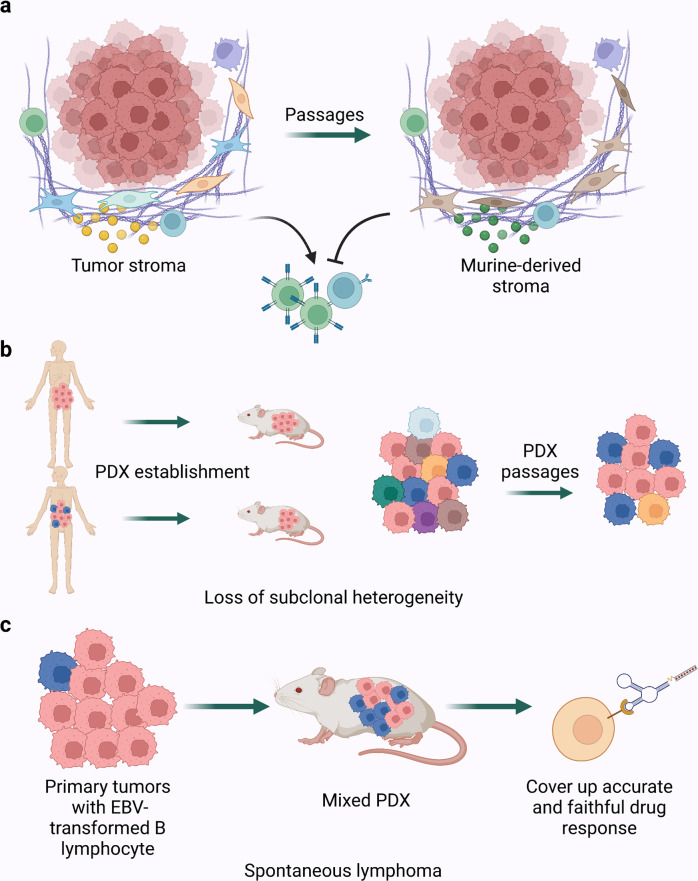

Declining fidelity and limited representation of tumor subcluster

The tumor microenvironment represents the complexity of the tumor and its surrounding components, including the extracellular matrix (ECM), stromal cells (endothelial cells, pericytes, carcinoma-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), pro-inflammatory cells), immune cells, and secreted factors.71 TME provides structural support and has a massive impact on tumor development by mediating signal transduction and cell migration.72 Preserving TME from the donor tumor is the premise for studying tumor behavior in vivo. Studies have shown that PDX models retain principal peculiarities such as tissue structure, subtle microscopic details, and biological behaviors.12,19,52 However, after two to five passages, tumor stroma is almost entirely replaced by murine-derived ECM and stromal cells, among which the most predominant member, CAFs, take the fastest replacement efficiency. Even so, Arnaud Blomme et al. conducted a comparative metabolic analysis between parental tumors and corresponding PDXs. They found that metabolic profiles of both tumor cells and stromal cells remained stable for at least four passages, while the replacement occurred at the second passage.73 This study indicated that replacing human stroma was an acceptable drawback at the early stage of PDX research. Nevertheless, it causes trouble for the study time window and brings uncertainty for various kinds of research. Considering the critical role of CAFs in the modulation of TME, co-implantation of matched human CAFs and tumor fragments along with PDX passage may help alleviate this problem. Besides, due to species specificity, murine-derived cytokines and chemokines fail to maintain the functions of immune cells in humanized PDX. Murine IL-2 has a low activation effect on human T cells, as does murine IL-15 on NK cells.74,75 It hinders immune cell activation and tumor-immune interaction without human cytokine and chemokine secretion71,76 (Fig. 5). While periodic injections of IL-15 could maintain NK cell viability,77 more advanced strategies, such as genetically modified mice expressing human cytokines or growth factors, would preserve the immune microenvironment to the utmost. Anthony Rongvaux and colleagues knocked in four genes encoding human macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), interleukin-3 (IL-3), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and thrombopoietin (TPO) to their respective mouse loci to support the development of human innate immune cells, including monocytes/macrophages and NK cells, which resembled the infiltration patterns in human tumors.78 Meraz et al. developed humanized PDX from fresh cord blood CD34 + stem cells, which reconstituted an human innate and adaptive immune system with less time and replicated human response to anti-PD-1.41 An updated study introduced human thymus engineering derived from inducible pluripotent stem cells to generate diverse human T cell populations in humanized mice.79 This novel technology may leapfrog the troubles in the scarce resources of transplanted tissues and the experimental ethics. Looking at stroma replacement another way, the composition and proportion of stromal cells could make a difference to the subtype classification of tumors, especially in CRC, thereby influencing the treatment choice. CMS4, the molecular subtype with the worst prognosis in CRC, has long been thought to have the property of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, which was now found to attribute mostly to stromal cells rather than tumor cells themselves.80,81 It reminds us that deciphering tumor cell-specific peculiarities with less stroma influence may reduce the heterogeneity of detection results to a certain extent and bring some new ideas to tumor subtype classification in clinical practice. Claudio Isella and colleagues assessed tumor intrinsic transcriptional features through human-specific expression profiling of CRC PDX and proposed CRC intrinsic gene signatures (CRIS) that exclude stroma-derived genes. Compared to CMS, CRIS more accurately reflects intrinsic tumor characteristics to stratify CRC populations and provides a better spatial and temporal classification of CRC. In addition, there is little overlap between CRIS and CMS, providing a better insight into CRC heterogeneity when used together.82

Fig. 5.

The weaknesses existing in current PDX models. a Tumor stroma tends to be replaced by murine-derived ECM and stromal cells after several passages, which hinders immune cell activation without human cytokine secretion. b Loss of subclones heterogeneity during the establishment and passage of PDX. c PDX mice have a relatively high risk of spontaneous lymphoma which could cover up accurate results due to the distinct drug sensitivities between lymphoma and other tumors

As mentioned above, PDX is regarded as the optimal model for describing tumor landscape. However, studies revealed that PDX underrepresented the subclonal heterogeneity, which may be critical for drug screening, while most clonal mutations could be preserved.83 This may be due to the sampling bias caused by spatial heterogeneity, different capacity to engraft and proliferate once injected, or tumor evolution and selection during PDX passages. In GBM PDX, although common molecular drivers were captured at frequencies comparable with the primary tumor, some alterations were gained or lost as if it were a process of clonal selection.47 Moreover, as GBM PDX passages increased, accelerated cell growth and increased malignancy were observed.84 Later-passage PDX models showed reduced similarity with primary tumors in DNA-based copy number profiles.85 These observations indicate that utilizing PDX with fewer passages could do better for fidelity. As for presenting the subtype heterogeneity of CRC patients, the four CMS subtypes displayed various engraftment rates and passage rates in PDX, among which CMS1 and CMS4 showed significant advantages. Given the potential subtype-specific drug sensitivity, it may skew the results of drug screening research.86,87 In addition, microsatellite instable (MSI) tumors carrying germline mutations easily retained their histological features compared to those with MLH1 promoter hypermethylation.88 Regarding intratumor heterogeneity, subclones may have different chances to keep going in PDX passages. Mixed or spindle cell uveal melanoma was characterized as epithelioid uveal melanoma in PDX, which indicates that these tumor cells were more likely to survive and grow in PDX.33,89 By comparing the gene signature of cancer cell subtypes between the biopsy from patients and the PDX models of small-cell lung cancer (SCLC), Lissa et al. uncovered that SCLC PDX models had a significantly higher proportion of neuroendocrine cells compared to that of the biopsy.90 This ill-recapitulation of intratumor heterogeneity and tumor differentiation may result from clonal selection under experimental processing or tumor evolution due to TME instability. These studies remind us that tumor heterogeneity might not be fully reflected during the establishment and passage of PDX (Fig. 5). Considering the effect of some subclones with specific biological peculiarities or drug resistance, studies such as those regarding targeted therapy could fall victim to unexpected bias. Considering that tumor heterogeneity is not only an autologous characteristic but also regulated by TME, the replacement of tumor stroma in PDX and the unstable immune system in humanized PDX may contribute mainly to the underrepresented intratumor heterogeneity through passages. Therefore, the reconstitution and monitoring of tumor stroma and the functional human immune system are essential to better maintain the tumor heterogeneity in PDX and better serve translational medicine.

Besides, the selection of mouse strains partly determines the recapitulation of cancer. The characteristics of immune system components, the engraftment rate reported by previous studies, the tendency to develop metastasis, and the susceptibility to different diseases are all key points to better match the research objectives.22,91 PDX mice have a relatively high risk of spontaneous lymphoma (Fig. 5). The EBV-transformed B lymphocyte in primary tumors often outgrew xenotransplantation soon after in CRC and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) PDX, especially in NSG mice.92 Moreover, a mixed PDX was formed after several passages, which could obstruct accurate and faithful clinical research due to the distinct drug sensitivities between lymphoma and other tumors. Since these lymphocytes generally expressed CD45, researchers proposed that sorting cells in advance could yield pure tumor cells for xenotransplantation. However, the dissociation of cells would destroy the original structure of the tumor and have a significant influence on PDX engraftment. Ovarian cancer PDX also developed unintended lymphoma frequently. Rituximab, which suppresses human lymphoproliferation, could reduce the incidence of lymphoma in subsequent PDX passages.93 However, the problem persisted: the effects of these interventions on tumor grafts were still undetermined. It hence highlights the need for a rigorous strategy for the detecting tumors and subsequent passages.

Novel support technologies for the PDX model

Improving the efficiency of PDX establishment

PDX establishment has been time-consuming and sometimes cannot serve as drug selection guidance for the donor on time. To speed up the process, Zhang et al. developed MiniPDX, which improved the implantation procedure and shortened the period for the in vivo drug response assay.94 In a study to establish pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma PDX models, the authors resected the PDX tissues incompletely after growing them to a certain volume and allowed the remains to grow continuously, which turned out to grow significantly faster than the original passage.95 Besides, establishing and maintaining a PDX biobank requires a daunting amount of effort, which makes it hard to perform long-term or large-scale drug screening. Accordingly, researchers generated cancer cell lines96,97 and organoids98,99 from PDXs, which were proved to retain the characteristics of the original PDX models100 and have similar drug responses with the original PDX models in different cancer types, such as bladder cancer101 and melanoma.102

Because of the relatively long cycle and high cost of establishing mouse PDX models, researchers started looking for alternative species to serve as more efficient preclinical platforms. Zebrafish xenograft models have become a great alternative, as they support short-cycle, large-scale ex vivo assays at a low cost.103 Almstedt et al. established zebrafish tumor xenografts (ZTX) using glioblastoma cell cultures derived from patients and evaluated their growth longitudinally employing neural network analysis. They discovered that compared to the corresponding mouse PDX models, zebrafish models showed similar growth, invasion, and survival tendencies.104 In non-small cell lung cancer, Ali et al. implanted PDX tissues into zebrafish embryos and generated drug responses like mouse PDX models and the patients. Moreover, ZTX models recapitulated the invasive characteristics of the tissues and can be used to predict lymph node metastasis.105 In another study, Pizon et al. used chick chorioallantoic membrane to generate breast cancer PDX models, which showed a positive correlation with the primary tumor in terms of aggressiveness and proliferation.106

Establishment of PDX biobanks

To facilitate the preclinical test of novel cancer treatments on PDX models, the U.S. and Europe have separately established two multi-center pan-cancer PDX consortiums, PDXNet107 and EurOPDX.108 A major challenge of multi-center PDX collection is to guarantee consistency among the PDXs from different centers. The PDXNet treated pre-validated PDX models from different centers with temozolomide, and they discovered that the PDXs from each center had the predicted response to the drug.109 To facilitate the management of PDX models among different centers and guarantee the quality and accessibility of the PDX models, Meehan et al. presented PDX-MI, which stands for “PDX models minimal information standard”. PDX-MI includes information regarding four aspects: clinical features, model creation, model quality assurance, and study of the model.110 Besides the consortium-led PDX biobanks, many organizations provide PDX model platforms with genomic data.111 When testing the function of novel drugs, researchers can pick out PDX models from the biobanks according to cancer types or molecular features (Table 3). As the PDX transplantation technologies become mature and the sequencing technologies accessible, researchers can tailor specialized PDX biobanks to capture the various molecular features of patients across different cancer stages, molecular subtypes, and anatomic sites. As for colorectal cancer, Mullins et al. established a PDX biobank from 149 patients with different staging, clinicopathological, and molecular features.112 Corso et al. established a PDX biobank of gastric cancer, which highlighted the MSI signature.113 To make these models more accessible, Conte et al. established the PDX Finder to help extract the characteristics of these PDX models.114

Table 3.

PDX biobanks

| Affiliation | Reference/website | Number of PDX cases | Cancer type |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCI Patient-Derived Models Repository | Patient-Derived Models Repository (PDMR) (cancer.gov) | Over 1000 | Pan-cancer |

| Princess Marget Living Biobank | Princess Margaret Living Biobank | UHN (uhnresearch.ca) | Over 850 | Pan-cancer |

| The Center for Patient Derived Models at Dana Farber Cancer Institute | Center for Patient Derived Models (CPDM) - Dana-Farber Cancer Institute | Boston, MA | Over 700 | Pan-cancer |

| Candiolo Cancer Institute | Home | Istituto di Candiolo - FPO - IRCCS | Over 700 | Gastric cancer and colorectal cancer |

| Charles River Laboratories | Patient-Derived Xenograft: PDX Models | Charles River (criver.com) | Over 450 | Pan-cancer |

| Washington University in St. Louis | PDXdb: Washington University PDX Development and Trial Center | PDXdb (wustl.edu) | Over 300 | Pan-cancer |

| Pediatric Preclinical In Vivo Testing Consortium | Pediatric Preclinical In Vivo Testing Consortium (PIVOT) – Advancing treatment options for children with cancer (preclinicalpivot.org) | Over 250 | Pediatric tumors |

| St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital | Home | Childhood Solid Tumor Network (CSTN) Data Portal | St. Jude Cloud (stjude.cloud) | Over 150 | Pediatric solid tumors |

| Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology | Home - VHIO | Over 70 | Breast carcinoma, pancreas cancer, colorectal cancer |

| Luxembourg Institute of Health | PRECISION-PDX »Luxembourg Institute of Health (lih.lu) | Over 40 | Glioma |

| J-PDX | 265 | Over 290 | Pan-cancer |

Dynamic detection of patient status

PDX cannot fully copy the cancer microenvironment in the human body because of many innate factors, such as the surrounding murine-derived stromal cells and the lack of a fully equipped immune system. Besides, each PDX model can only reflect the status of cancer at one single stage. When a patient undergoes several lines of treatment, real-time detection is necessary to reveal the change in tumor characteristics. The detection of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and circulating tumor cells (CTC) derived from liquid biopsies has been proven as an effective non-invasive method to capture the properties of cancer. Yaegashi et al. validated that if choosing the mutation targets correctly, ctDNA monitoring is sufficient to reflect the tumor burden.115 Cayrefourcq et al. examined the gene expression profiles of CTC lines from a patient with metastatic colon cancer, and they identified the gene dysregulations that lead to drug resistance.116 Therefore, in the context of “co-clinical trials” of PDXs and patients, researchers can collect more comprehensive data with patients’ non-invasive liquid biopsy results as complements. To investigate acquired resistance against targeted therapy, Russo et al. conducted a co-clinical trial and did NGS analysis on gDNA from PDX and ctDNA collected during treatment.117 Moreover, CTC-derived xenografts (CDX) can assist clinicians in identifying the genomic and transcriptomic features of metastatic cancer cells and guiding the treatment against late-stage cancer.118 Faugeroux et al. established a CDX model in the context of prostate cancer and identified that a subclone with TP53 loss triggers cancer metastasis, facilitating the drug screening for patients.119

Functional genomics and PDX models

Functional genomics approaches such as the short hairpin RNA (shRNA) library and the CRISPR screen have enabled researchers to identify novel drug targets in cancer, which has been extensively applied in vitro. However, due to the lack of interaction with other cells, such experiments cannot accurately reflect cancer cell status. Therefore, when combined with PDX models, functional genomics approaches can fully uncover cancer cell vulnerabilities in the context of other cell components in the cancer microenvironment.120,121 Using CRISPR-Cas screening technologies, Lin et al. identified several targets against acute myeloid leukemia in PDX models.122 Hulton et al. developed a Cas9 lentiviral vector that can directly target PDX cancer cells in vivo, which significantly facilitates the gene programming of PDX models and the in vivo detection of potential druggable candidates.123 Similarly, Wirth et al. developed a chemotherapy-resistant acute lymphoblastic leukemia PDX model and conducted in vivo CRISPR/Cas9 dropout screens to determine the genes that cancer cells depend on. They identified BCL2 and successfully recovered the tumor sensitivity toward chemotherapy.124 Interestingly, Carlet et al. used Cre-ERT2 inducible RNAi to mimic anti-cancer therapy and silence genes in PDX models, which combined the properties of the Cre-loxP system and RNAi techniques.125 A DNA barcode sequence is a type of unique sequence which can track the exact cells or components that carry it.126 Researchers have loaded DNA barcodes and drugs in nanoparticles and injected them into tumor-bearing mice, which helped identify the exact drugs that most efficiently kill cancer cells.127

Multi-omics and PDX models

Recent studies have emphasized the role of epigenetic changes in cancer drug resistance, which makes it necessary to detect gene modification events alongside gene expression. Multi-omics studies consist of genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, a thriving field providing researchers with much more data than ever before. Combining PDXs with technologies such as next-generation sequencing, transcriptome sequencing, and mass spectrometry (MS) can track the change in cancer cell status from different levels as they receive different treatments. Roche et al. compared the transcriptomics of primary tumor samples and PDX samples, and they showed consistency in the gene changes connected to cancer growth and proliferation.128 Moreover, the transcriptome can reflect the interaction among different components of cancer, such as the signaling transduction process between cancer cells and stromal cells.129 Mirhadi et al. conducted proteome analysis on a cohort of 137 NSCLC PDX models and identified different proteome subtypes with distinct outcomes and candidate targets.130 A study conducted metabolomic profiling in the context of PDX models of PDAC. It established a metabolic signature that significantly correlated with the prognosis of PDAC patients and aligned with the PDAC transcriptomic phenotypes.131 As demonstrated above, getting hold of the genome, transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome from the PDX cohort would provide numerous information that can guide personalized medicine. Moreover, the omics study’s ‘resolution ratio’ has progressed from bulk to single-cell analysis.132 Dimitrov-Markov et al. created PDX models of metastatic PDAC and sequenced single-cell RNA from circulating tumor cells. They found that the CTCs are highly metastatic and different from the matched primary and metastatic tumors.133 In another study, Mori et al. established PDX models of breast cancer that initially resided in the same breast tumors but had distinct responses to estrogen.134 Grosselin et al. conducted ChIP-seq at single-cell resolution to observe the chromatin landscapes of breast cancer xenografts and revealed intratumor heterogeneity at the chromatin level. They discovered that loss of chromatin marks H3K27me3, a transcriptional repressor against genes that contribute to drug resistance, was detected not only in resistant cells but also in a group of cells resident in drug-sensitive tumors.135 Still, researchers are developing updates on these technologies to solve new problems. The multiregional sequencing approach (MRA) collects DNA samples from multiple regions in one tumor and conducts NGS analysis to study intratumor heterogeneity. Sato et al. integrated MRA and PDX and detected the dynamic change of the subclonal architecture of CRC.136 Species-specific RNA sequencing has been applied to PDX models to distinguish the transcriptional signature originating from murine stromal cells and explore the crosstalk between cancer cells and stromal cells.81 Shared peptide allocation (SPA), a novel protein quantification method based on MS data, is designed to distinguish the unique and mutual peptides in the sample mixed with human cancer tissues and mouse tissues.137 The epigenome landscape reflects the epigenetic alterations of genes, which occur more frequently and diversely than genetic mutations and also reflect gene functions. DNA methylation is another common epigenetic modification form, and Tomar et al. analyzed the DNA methylome in ovarian cancer PDX models and determined the relationship between gene methylation and prognosis.138 The assay for Transposase Accessible Chromatin with high-throughput sequencing (ATAC-seq) identifies open chromatin regions that participate in cellular activity. ATAC-seq profile coupled with whole exome sequencing probes the active chromatin site as a potential druggable target.139 Interestingly, to study drug resistance in preclinical models, Tedesco et al. developed an integrated technology named scGET-seq that probes genomic and epigenomic sequences concomitantly at the single-cell level.140 Moreover, based on the unspliced and spliced mRNA abundance data from single-cell RNA sequencing, RNA velocity can be calculated to show the dynamic changes of the transcriptome and reflect how cancer cells go through different states.141 Based on mass spectrometry, the development of cytometry with time-of-flight (CyTOF) analysis supports high-throughput analysis of cell phenotypes.50 Meanwhile, phosphoproteomics can capture phosphoproteins, one of the most important post-translational modifications, and help to expose details about the protein status.142

Despite the large amount of data from the multi-omics study, it is still difficult to link the behavior of specific cancer cells to cancer progression. As mentioned above, DNA barcodes can track cellular behaviors at the single-cell level. Therefore, barcoded cancer cells can uncover the proliferation and metastasis tendency at a single-cell level, thus connecting cellular behavior with single-cell mRNA sequencing and revealing the cellular basis of intratumor heterogeneity.143

Massive data analysis and PDX model

Robust data analysis tools facilitate the application of the PDX platform. CancerCellNet uses machine learning algorithms to assess the transcriptional fidelity of PDX models to natural tumors.144 Specially designed for PDX platforms, DRAP is a data analysis software designed that processes data separately according to different PDX preclinical trial designs.145 As mentioned above, one of the most important missions of PDX models is to identify reliable biomarkers of drug response based on pharmacogenomic datasets, that is, the pharmacologic and high-throughput sequencing profiles of PDX. Several computational platforms have been constructed to analyze preclinical pharmacogenomic data and identify robust biomarkers that predict patient drug response and prognosis.146,147 Machine learning is a revolutionary technology that has been widely used in the field of translational medicine. The neural network of machine learning can achieve diversified tasks based on massive data. PDX drug discovery datasets and those from cell lines and patients provide a platform with adequate data, and researchers have accomplished various tasks using this platform. Based on the multi-omics dataset in PDX studies, artificial intelligence is widely exploited to predict a patient’s response to treatment. Jiang et al. proposed that drug molecular and cellular targets, drug responses, and adverse reactions are closely intertwined. Hence, they developed DrugOrchestra, a deep learning framework that integrates the abovementioned tasks and predicts the potency of novel compounds according to their molecular structure. Besides, machine learning strategies such as transfer learning148,149 and few-shot learning150 can also address the challenge of translating the preclinical data into clinical contexts and transferring the predictors from preclinical models to human cancer applications.

Imaging systems and PDX model

Many studies sought to test the commonalities between xenografts and tumors in the human body from the perspective of radiomics. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) helps to extract diverse information from PDX models. Tiwari et al. optimized MRS in a determined sequence to compare the production of 2-hydroxyglutarate between the PDX models and patients, which proved the similar IDH metabolism between PDX models and parental tumors.151 In the context of sarcoma PDX models, Jardim-Perassi et al. integrated the data of multiparametric MRI and histology into deep learning models to predict hypoxia and the response to hypoxia-activated prodrugs.152 Roy et al. extracted 48 features such as noise, resolution, and tumor volume from the MRI results of triple-negative breast cancer PDX models and discussed how the factors affect the radiomic analysis.153 Following this study, they further identified 64 robust features and used machine learning to select several strong biomarkers that constituted signatures that can be used to predict prognosis.154

Besides, integrating imaging technologies and PDX models contributes to the study of medicine uptake and distribution in a non-invasive manner. Using micro-computed tomography (µCT) imaging on PDX models, Moss et al. clarified that the density of vessels supporting pericytes is critical to liposome accumulation and distribution.155 In another study, Russel et al. used a radiotracer named 18F-FAC, which has a similar structure to gemcitabine, to track gemcitabine uptake in pancreatic cancer PDX models. Such a surrogate helps to determine drug uptake in patients conveniently.156 Interestingly, Almstedt et al. tagged the patient-derived GBM cells with green fluorescent protein (GFP), implanted them in zebrafish embryos, and observed their growth by light-sheet imaging. In this manner, they realized real-time observation of cancer initiation and development.104

Similarly, other practical techniques, such as in vivo imaging systems, need thorough validation before they are used on patients, and the PDX model is an ideal preclinical model. In the context of ovarian carcinoma, CD24 is highly expressed. Kleinmanns et al. conjugated an anti-CD24 antibody with Alexa Fluor 750 and used the antibody to provide real-time feedback on surgeries of metastatic ovarian carcinoma PDX models157; while binding an anti-CD24 antibody with Alexa Fluor 680 enabled monitoring the therapeutic efficacy of carboplatin-paclitaxel against ovarian cancer in the xenografts.158 Fonnes et al. established an orthotopic PDX model of endometrial carcinoma in another study. They utilized fluorescence-binding antibodies against epithelial cell adhesion molecules to track cancer’s development and anti-cancer treatment efficacy successfully.159

Application of PDX model in cancer therapy

Because of the PDX model’s fidelity to replicate patient diversity and the PDX model’s diversity to reflect diversified patients and real-world scenarios, the PDX model has been widely employed in exploring the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics,160 therapeutic effects, and drug resistance mechanisms of current treatments against cancer.161 This part delineates the application of PDX in the field of cancer treatment, including chemotherapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and other novel therapies.

PDX model in chemotherapy research

Chemotherapy is the most classical antitumor drug and clinically verified repeatedly in various cancers. However, chemotherapy resistance is the leading cause of tumor-related death worldwide. Moreover, there is a lack of appropriate methods to evaluate chemosensitivity to guide first-line chemotherapy. The PDX model has much to do with the selection and improvement of chemotherapy, including detecting sensitivity, exploring resistance-associated characteristics, and providing a suitable platform to test novel drugs and delivery methods.

Exploring chemosensitivity and resistance-related targets for personalized treatment

Clinicians have established a series of standards for chemotherapy selections. However, when faced with several drugs to choose from and inter-tumor heterogeneity among patients, inappropriate selection may not maximize patient benefit. With the help of PDX, researchers could test drug sensitivity at an individual level beforehand. Studies revealed that PDX-guided chemotherapy significantly upregulated overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) compared with standard treatment of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin in gallbladder cancer patients.162 Moreover, for tumors responsive to polychemotherapy, such as triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), using PDX to test the antitumor activity of a single drug and combination therapy is of great significance to guide individualized treatment with minimum toxicity.

PDX is also a practical tool to excavate targets for drug resistance and test combined drugs afterward. Researchers detected constitutive phosphorylation of spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) in infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia PDX, the combination of SYK inhibitor and chemotherapy could significantly enhance therapeutic efficacy.163 Nonetheless, they also found RAS-mediated resistance to SYK inhibition, which indicates the complexity of the whole genome picture and emphasizes the importance of personalized detection and treatment. Li et al. established chemo-resistant and chemo-sensitive ovarian cancer PDX models with paclitaxel and carboplatin.164 Through whole exome and RNA sequencing, they screened out the most resistance-related gene HLADPA1 and validated its association with resistance to initial chemotherapy in TCGA datasets. This research method was closely related to clinical practice and provided an entry point for in-depth research.

Developing and testing novel drugs and delivery methods

Conventional chemotherapy usually acts through DNA damage, which could be evaded by tumor cell-induced cellular dormancy. Meanwhile, other factors, such as the tumor extracellular matrix, drug bioavailability, and the effect of targeting, all affect the efficacy of chemotherapy. It is an effective and convincing way to modify and detect these influencing factors by the PDX model.

Researchers invented a small molecule inhibitor called phendione that induced a DNA damage response without causing DNA breaks or allowing cellular dormancy.165 This inhibitor significantly suppressed tumor growth in BRAFV600E- and NRASQ61R-driven melanoma PDX, indicating a novel way to combat chemotherapy resistance and proposing a new idea of targeted chemotherapy. Some tumors, such as appendiceal mucinous carcinoma peritonei (MCP), exhibited an inadequate response to chemotherapy due to the protective effect of abundant extracellular mucus, which impeded drug delivery. Researchers developed a combination of bromelain and N-acetylcysteine to achieve mucolysis and significantly enhanced the chemotherapeutic effect in MCP PDX.166 Moreover, boosting the bioavailability of drugs by chemical modification is essential to improve the efficacy of chemotherapy. Modified gemcitabine, termed 4-N-stearoylGem, strongly inhibited tumor growth in pancreatic cancer PDX and surprisingly showed an antiangiogenic effect by reducing vascular endothelial growth factor receptors expression.167 Combining some novel delivery systems and technologies also showed a promising future for chemotherapy. In bladder cancer PDX, the nano-sized drug delivery system poly (OEGMA)-PTX@Ce6 (NPs@Ce6) combined with chemo-photodynamic therapy markedly improved tumor targeting and suppressed tumor growth up to 98%. In addition, this combined therapy was versatile and went beyond the functions of conventional chemotherapy, with the ability to upregulate oxidative phosphorylation and reactive oxygen species generation, and downregulate tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis signals.168

PDX model in targeted therapy research

Despite discovering novel targets and developing novel target therapies, many cancers respond poorly to the targeted therapies, even with several drugs combined. Researchers constantly reveal novel mutations contributing to the resistance to targeted therapies.169 Moreover, intratumor heterogeneity restrains the therapeutic effect of these therapies, and cancer cells become liable to mutate under the pressure of targeted therapy, which further intensifies cancer heterogeneity.170 Therefore, the ensuing targeted strategies may have distinct effects on different cancer cell subclones, facilitating drug-resistant subclones outgrowth and an overall poor response.171 The PDX model presents the molecular characteristics and the complexity of the cancer landscape, which helps to give authentic feedback when treated with targeted therapies. The combination of next-generation sequencing, immunohistochemistry, and in situ hybridization captures the histopathological and molecular signatures and guides target therapy for the patients represented by PDX models.172 PDX models have aided in developing numerous targeted therapies for various cancer types (Table 4). This section discusses four scenarios in which the PDX models have advantages compared to traditional models.

Table 4.

PDX model in targeted therapy research

| Reference | Drug name | Drug administration method | Gene target | Cancer type | Application scenario |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schueler et al.266 | Gefitinib | Oral gavage | EGFR | NSCLC | Drug resistance mechanism study |

| Zhang et al.267 | ASK120067 | Oral gavage | EGFR | NSCLC | Novel drug validation |

| Chew et al.268 | AZD4547, BLU9931 | oral gavage | FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR4 | breast cancer | Therapeutic target identification |

| Krytska et al.269 | crizotinib | Intraperitoneal Injections | ALK | Neuroblastoma | Drug combination validation |

| Shattuck-Brandt et al.270 | KRT-232 | oral gavage | MDM2 | Metastatic Melanoma | Therapeutic target identification |

| Kinsey et al.271 | trametinib | oral gavage | MEK | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | Drug combination validation |

| Coussy et al.272 | BYL-719; | oral gavage | PI3K | PIK3CA-mutated metaplastic breast cancer | Drug combination validation |

| selumetinib | oral gavage | MEK | |||

| Coussy et al.181 | BAY80-6946; | N/A | PI3K p110α subunit | enzalutamide-resistant luminal androgen receptor triple-negative breast cancer | Therapeutic target identification |

| PF-04691502; | mTOR and PI3K | ||||

| AZD2014 | mTORC1 and mTORC2 | ||||

| Hsu et al.273 | MLN0128 | oral gavage |

dual mTOR complex HER 2 |

HR + /HER2 + Breast Cancer | Drug combination validation |

| trastuzumab | intraperitoneal injection | ||||

| Harris et al.274 | pertuzumab/trastuzumab | oral gavage | HER2 | Ovarian cancer | Drug combination validation |

| Hashimoto et al.275 | U3-1402 | intravenous | HER3 | HER3 positive cancer | Novel drug validation |

| Reddy et al.276 | Pan-HER | Intraperitoneal injection | Pan-HER antibody mixture against EGFR, HER2, and HER3 | TNBC | Drug combination validation |

| Odintsov et al.277 | GSK2849330 | intraperitoneal injection | HER3 | NRG1-rearranged lung adenocarcinoma | Drug combination validation |

| Chen et al.278 | compound 36 l | Intraperitoneal injection | KRAS‒PDEδ | pancreatic tumor | Novel drug preclinical validation |

| Barrette et al.279 | Verteporfin | Intraperitoneal injection | YAP-TEAD | Glioblastoma | Novel drug preclinical validation |

| Hemming et al.280 | YKL-5–124 | Intraperitoneal injection | CDK7 | Leiomyosarcoma | Therapeutic target identification |

| Gebreyohannes et al.193 | Avapritinib | Oral gavage | Mutated KIT | Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors | Novel drug preclinical validation |

| Karalis et al.281 | Lenvatinib | Oral gavage | Multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Gastric cancer | Novel drug preclinical validation |

| Dankner et al.282 | Dabrafenib, encorafenib | Oral gavage | BRAF | Class II BRAF mutant melanoma | Drug combination validation |

| Trametinib and binimetinib | Oral gavage | MEK | |||

| Knudsen et al.283 | Palbociclib | Oral gavage | CDK4/6 | Pancreatic cancer | Drug combination validation |

| Trametinib | Oral gavage | MEK | |||

| Zhao et al.189 | Neratinib | Oral gavage | Neratinib with CDK4/6, mTOR, and MEK inhibitors for the treatment of HER2 + cancer. | Pan-cancer | Drug combination validation |

| Yao et al.48 | Cetuximab | Intraperitoneal injection | EGFR | Colorectal Cancer | Drug combination validation |

| LSN3074753 | Oral gavage | RAF | |||

| Gymnopoulos et al.284 | TR1801-ADC | Intravenous injection | CMet | Pan-cancer | Novel drug preclinical validation |

| Vaisitti et al.285 | VLS-101 | Intravenous injection | ROR1 | Richter syndrome | Novel drug preclinical validation |

| Haikala et al.233 | HER3-DXd | Intravenous injection | HER3 | EGFR mutant non-small cell lung cancer | Novel drug preclinical validation |

Screening drug sensitivity patients

Numerous PDX biobanks worldwide collect cancer across the diverse genomic and transcriptomic background. Therefore, when a novel therapy is developed, these platforms are an ideal tool for performing preclinical screening to identify signatures and biomarkers that serve as criteria to recognize patients who can benefit from the therapy. The Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research established a PCT that followed the “one animal per model per treatment’ design and tested the response to 62 treatment strategies.13 Schütte et al. generated a preclinical platform to test the drug sensitivity of clinical drugs and used multi-omics data to identify new biomarkers to predict drug responses.173 Lindner et al. performed protein analysis on CRC PDX models and established fourteen markers distinguishing cetuximab-sensitive tumors from cetuximab-resistant tumors.174 Bonazzi et al. established different subtypes of endometrial cancer. Treating them with the PARP inhibitor talazoparib revealed that the molecular subtype with a high copy number is sensitive to the PARP inhibitor.175 The mTOR pathway is essential for gastric cancer (GC), but the mTOR inhibitor everolimus is not universally effective in treating gastric cancer. Fukamachi et al. derived cancer cell lines from diffuse-type GC PDX models and discovered they are sensitive to everolimus. Further, they found that the GC cells from PDX belong to cluster II of diffuse-type GC in clinical practice, which is characterized by chromosomally unstable (CIN) or MSI.176 Similarly, PDX trials can identify patients with specific mutations that lead them to resist paticular target therapy. Kemper et al. established a PDX trial from melanoma metastases and identified the BRAFV600E kinase domain as a resistance mechanism. Then they validated the efficacy of the pan-RAF dimerization inhibitor to eliminate this subclone.177 In high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSC), suppression of RAD51C leads to defective homologous recombination and marks sensitivity to PARP inhibitors. Nesic et al. established RAD51C promoter methylation PDX models and discovered that while homozygous RAD51C methylation indicates PARP inhibitor sensitivity, a single copy of unmethylated RAD51C causes drug resistance.178

Moreover, establishing PDX models for patient subtypes resistant to current treatment options helps to investigate new therapies. Many researchers have exploited the drugs selected in PDX models on patients and tested their efficacy.179 Afatinib, a TKI targeting HER2 and EGFR, outstood the drug sensitivity test in a PDX model derived from a CRC patient resistant to multiple lines of treatment; the patient used afatinib subsequently and achieved progression-free survival for three months.180 Coussy et al. used PDX models to study the therapeutic choices for patients with luminal androgen receptor triple-negative breast cancer resistant to enzalutamide and discovered significant enrichment in PIK3CA and AKT1 mutations. Consequently, mTOR and PI3K inhibitors are proven effective for these patients.181 Metastatic colorectal cancer patients with KRAS and BRAF mutations have poor prognoses. Therefore, Area et al. established PDX models for them and examined the vulnerability to the PARP inhibitor olaparib and the chemotherapy drug oxaliplatin. They discovered that a subset of PDX models is deficient in HR, and they are sensitive to olaparib, and such response is positively correlated with oxaliplatin vulnerability. As oxaliplatin is a common choice for such patients, this study provides a rationale for sequential treatment with oxaliplatin and olaparib.182 With the aid of whole exome sequencing and transcriptome sequencing, PDX cohorts would facilitate the identification of biomarkers that can predict the drug sensitivity of patients.

Exploring mechanisms of therapeutic effect and drug resistance

Compared to normal mouse xenograft models, PDX models can be generated with tumor cells from patients who undergo resistance to certain therapies, which makes them better models for studying the mechanisms of cancer drug resistance to existing therapies and facilitating the development of novel therapeutic targets. Utilizing establishing PDX models from drug-resistant patients, researchers identified mutation sites such as MET that led to cetuximab resistance.183 Silic-Benussi et al. revealed that, in the context of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), mTOR pathway activation led to drug resistance to glucocorticoid because of an insufficient level of ROS. When treating with the mTOR inhibitor everolimus in the T-ALL PDX model, they observed an increased level of ROS accompanied by a decreased capacity of ROS scavenging and significant therapeutic effects.184 Zhang et al. treated a KRAS G13D mutant CRC PDX model with cetuximab and detected the expression level changes of different genes, thereby determining potential genes contributing to acquired resistance.185 Another study investigated the mechanism of EGFR inhibitor resistance and discovered that the remaining tumor cells after EGFR treatment have high HER-2 and HER-3 activity. Subsequently, pan-EGFR antibodies significantly reduced the residual disease.186 To test the effect and mechanisms of EGFR-TKI on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), Liu et al. treated ESCC PDX models with afatinib and examined the underlying mechanism. They discovered that afatinib exerts its function by suppressing EGFR downstream pathways and inducing cell apoptosis. Besides, aberrant phosphorylation of Src family kinases (SFKs) leads to resistance to afatinib, and the combination of EGFR and SFK inhibitors can overcome the afatinib resistance.187 Li et al. established three PDX models to explore the drug resistance mechanism of a pediatric BRAFV600E-mutant brain tumor against MEK inhibitor trametinib. They found that the decoupling of TORC1 signaling, originally a downstream pathway of MEK, led to resistance to trametinib; moreover, the combination of a TORC1 inhibitor and trametinib postponed the development of trametinib resistance.188

Developing novel targeted drugs and exploring drug combinations