Abstract

Background:

Research has extensively examined family members’ grief prior to the death of an individual with a life-limiting illness but several inconsistencies in its conceptualization of related constructs, yet significant conceptualization issues exist.

Aim:

This study aimed to identify and characterize studies published on family members grief before the death of an individual with a life-limiting illness, and propose definitions based on past studies in order to initiate conceptual clarity.

Design:

A mixed-method systematic review utilized six databases and was last conducted July 10, 2021. The search strategy was developed using Medical Subject Headings. This study was prospectively registered on PROSPERO (CRD42020166254).

Results:

134 full-text articles met inclusion criteria. This review revealed across studies a wide variation in terminology, conceptualization, and characterization of grief before the death. More than 18 terms and 30 definitions have been used. In many cases, the same term (e.g., anticipatory grief) was defined differently across studies.

Conclusions:

We found grief occurring before the death of a person with a life-limiting illness, which we termed pre-death grief, is comprised of two distinct constructs: anticipatory grief and illness-related grief. Anticipatory grief is future-oriented and is characterized by separation distress and worry about a future without the person with the life-limiting illness being physically present. Illness-related grief is present-oriented and is characterized by grief over current and ongoing losses experienced during the illness trajectory. These definitions provide the field with uniform constructs to advance the study of grief before the death of an individual with a life-limiting illness.

Keywords: Palliative care, Grief, Family, Caregivers, Terminally ill

Most deaths worldwide are attributed to a chronic or life-limiting illness1. In response to continued improvements in medicine, including advancements in early detection of medical conditions, the length of time between diagnosis and death has increased. While the increase in life expectancy for individuals living with a life-limiting illness may have notable benefits, there are also negative consequences for the patient2, 3 and their family members 4, 5. For example, increasing data trends indicate that family members are likely to experience some level of grief before the person with a life-limiting illness dies6,7. The extent to which a family member experiences grief prior to a death occurring has been found to predict long-term functioning in bereavement, including developing depression8 or prolonged grief disorder9, 10. However, our current understanding of grief experiences in family members prior to the death is hampered by the lack of a universal definition, the use of multiple terms, and inconsistent operationalization of constructs. By gaining a comprehensive understanding of the literature examining grief in family members before the death, researchers will be better equipped to understand what constitutes normative and non-normative experiences of grief before the death, and to identify key intervention targets that may decrease family members’ risk for and experience of debilitating psychological symptoms both in the short- and long-term. Therefore, the current systematic review aimed to identify and characterize the studies published on grief before a death for family members5 and propose definitions grounded in extant research for the types of grief that can occur before a death.

There has been an abundant amount of research examining family members’ grief prior to the death of an individual with a life-limiting illness. The earliest documented definition of this form of grief came from Lindemann11, who described it as a grief process that begins when family members are provided advance warning of a patient’s impending death. In her work on this topic, Rando then12 defined it as a “reaction to the impending loss of a terminally ill loved one and to all other past and present losses related to the illness, in addition to the mourning and all other psychosocial processes stimulated by these losses” (p. 24). The most prominent and well-known term to describe this experience is anticipatory grief, but a recent review of articles examining anticipatory grief found ten different definitions used within studies13. In this review, Coelho and Barbosa13 concluded that, when examining grief before the death, there are conceptualization issues, thereby limiting the ability to make comparisons of findings across studies. This is problematic for many reasons, as it hinders the potential advancement of the field in differentiating typical grief from more impairing grief before the death.

Further complicating the picture is the sheer number of terms used to describe grief before death; a concept analysis by Lindauer and Harvath14 found that there were more than 20 terms other than anticipatory grief used in the literature between 2000 and 2013. The authors compared three terms found to be the most utilized in the literature: anticipatory grief, pre-death grief, and chronic sorrow.14 They noted that one conceptual difference between anticipatory grief, pre-death grief, and chronic sorrow was the likely amount of time the person with life-limiting illness had left to live. While this effort to distinguish terms is useful, further clarity is needed for several reasons. First, determining a patient’s prognosis is notoriously challenging15, and so defining grief before death based on prognosis would be correspondingly difficult. This concept analysis set important groundwork for the current review by identifying 20 different terms (see Appendix A) to examine grief before the death, but they only compared the three most used terms to exclusively provide a definition for pre-death grief.

Given these limitations and an increase in studies since 20147, there is a need for an updated and systematic understanding of the full body of literature that comprehensively examines terms used to describe family members’ grief before the death of an individual with a life-limiting illness. Thus, the present systematic review was undertaken to increase conceptual clarity on this grief experience and develop a consistent definition. To advance the field and allow for direct comparison between studies, a consistent definition is crucial. Additionally, the use of a uniform definition could provide clearer benchmarks of what constitutes debilitating grief before a death in order to appropriately develop and tailor interventions.

Methods

This systemic review aimed to (1) identify and characterize the studies published on family member grief before a death of an individual with life-limiting illness, and (2) propose a definition for such grief that has conceptual clarity and precision and is grounded in past research.

Systematic Review Design

This mixed-method systematic review and protocol were prospectively registered on PROSPERO on January 1, 2020 (Registration Number: CRD42020166254). This study used a phenomenological approach in which we integrated findings of primary quantitative and qualitative studies to build a network of related concepts that together provide a comprehensive understanding of grief before the death of a person with a life-limiting illness.

Search Strategy and Data Sources

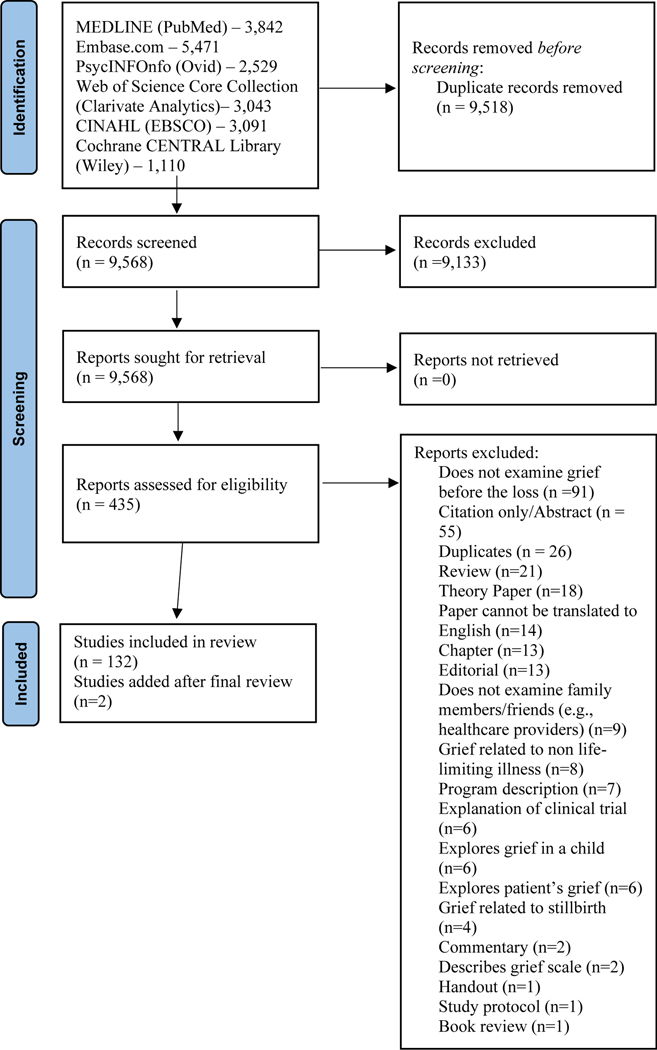

Procedures were conducted and reported according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines 16. Six databases were selected: PubMed (via National Library of Medicine’s PubMed.gov), Embase (via Elsevier’s Embase.com), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials / Cochrane CENTRAL (via Wiley’s Cochrane Library), PsycINFO (via Ovid), Web of Science Core Collection (via Clarivate Analytics), and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (via EBSCO). Concepts were combined with the Boolean AND operator, and the Cochrane Handbook filter was used to exclude animal-only studies 17. A second research informationist performed a Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS), and edits were implemented 18. For a complete strategy, see the accompanying PubMed search displayed in Appendix B. The six databases were comprehensively searched on February 24, 2020. The first author (JS) later conducted two updates (April 1, 2021; July 10, 2021) and searched the six databases to identify if any new articles should be added to the review that were published after February 24, 2020. Results were entered as Research Information System files (i.e., standardized tag format) in Covidence, a web-based software platform for systematic review development 19.

Selection Strategy

Studies were considered eligible for inclusion if they evaluated family members’ or friend’s grief related to an individual currently living with a life-limiting illness. Studies that evaluated grief after the death had occurred or did not explicitly measure or refer to grief or examined grief related to non-life limiting illness (e.g., diabetes) were excluded.

Screening Process

After duplicates were removed, abstracts were reviewed by two independent reviewers for initial eligibility. Articles were considered for full-text review if both reviewers agreed they met inclusion criteria. When there was disagreement between two reviewers, discrepancies were discussed with the first and second authors. All studies that met criteria for full-text evaluation were then independently reviewed by two reviewers and disagreements between reviewers were discussed with the first and second author. A standardized template was developed to extract pre-specified information from the final set of included articles. For each article, a reviewer completed the coding template to extract the pre-determined information from each article.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

After studies were selected, they were individually entered by the authors into an Excel table for data extraction. Authors were instructed to indicate title, authors, whether the study was qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods, design of the study, whether prospective or retrospective, purpose of the study, sample details (mean age, gender, race/ethnicity, relationship to patient/deceased, disease status), key qualitative and quantitative findings, term used to describe grief (e.g., anticipatory grief), and implications related to defining the term. The first author (JS) organized the studies by the grief term used and conducted a thematic synthesis of the definitions used within the terms. To interpret the results, a thematic synthesis was performed. The synthesis began with ‘line-by-line’ coding of the included articles (n=132), which were put into categories (i.e., term used; definition used; measure used). These were then aggregated by term used.

Results

A total of 9,568 records were reviewed. A final set of 132 full-text articles underwent qualitative synthesis (see Figure 1 for PRISMA). Two studies 7,20 were added from the review of the databases on April 1, 2021 and another on July 10, 2021. Therefore, 134 full-text articles underwent thematic synthesis (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

The studies were predominantly quantitative (N=77; 57.46%). Thirty-three (23.88%) were qualitative and 24 (17.91%) used mixed methods. Most of the studies were prospective (N=110; 82.09%). Twenty (14.93%) were retrospective and four (3.00%) included both prospective and retrospective analyses.

Participants in these studies primarily endorsed their family member was diagnosed with dementia (N=51; 38.1%) or cancer (N=39; 29.1%) broadly. When examining the prognosis of the individual with the life-limiting illness, most studies stated that they had “late-stage dementia” or “advanced cancer.” For the studies that provided the relationship to the person with the life-limiting illness, 58.0% were adult children, 28.1% were spouses/partners, and 13.9% were other relatives/friends (e.g., parents).

There were 18 different terms used to describe grief in family members of individuals who have a life-limiting illness. The terms used were anticipatory grief (N=34), pre-death grief (N=18), grief (N=12), pre-loss grief (N=6), caregiver grief (N=5), grief in caregivers (N=4), and anticipatory mourning (N=4). Nineteen studies used multiple terms throughout a single article. There were also 10 other terms that were each used only once in separate studies. Due to the large number of articles in this systematic review, we limited our in-text analysis to articles where the term (e.g., pre-death grief) was used in more than one article. Therefore, we did not analyze these 10 studies. However, they are described in Table 1. Also, there were two studies that described grief in family members of individuals who have a life-limiting illness but did not use a specific term to describe their experience.

Table 1.

Articles Examining Family Members’ Grief Prior to the Death of Individuals with a Life-limiting Illness

| Author et al. (Year) | Methods | Field | Purpose of Study | Illness Context | Sample characteristics | AG/Pre-loss measure or Qualitative interview questions | Term used | Definition of pre-grief term |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams & Sanders (2004) [71] | Mixed | Neurology | Examine the self-reported losses, grief reactions, and depressive symptoms among caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease or other progressive dementia | AD, other known disease, not known disease | n = 99 M = 59.07 (14.55) f: 69; m: 30 |

Qual interview guide | Grief | Not defined |

| Al-Gamal et al. (2009) 103 | Quant | Oncology | Develop a modified version of MM-CGI for the assessment of AG among Jordanian parents of children with cancer (the MM-CGI Childhood Cancer) | Cancer | n = 140 Mmothers = 34.4 (6.93), Mfathers = 39.5(8.62) Fnewly: 57; mnewly: 13; f6–12: 42; m6–12: 28 |

MM-CGI-CC | AG | AG is the process of mourning, coping, interaction, planning and psychological reorganization that are stimulated and are in response to the impending loss of a loved one and the recognition of associated losses in the past, present and future |

| Albinsson & Strang (2003) 34 | Qual | Neurology | Examine issues relevant to family members caring for patients with dementia | Dementia | n = 20 M = not provided, Age range = 44–80 f: 12; m: 8 |

Qual interview guide | AG | Not defined |

| Anngela-Cole et al. (2011) 91 | Qual | Oncology | Investigate stress, AM, and cultural-practices among family caregivers different cultural groups | Terminal cancer | n = 56 M = 57.9, SD = not provided f: 51; m: 5 |

Qual interview guide | AM | AM is time-limited: the uncertainty surrounding the amount of time a loved one has left often creates a more concentrated and heightened grieving experience pre-death, as opposed to post-death |

| Areia et al. (2019) 35 | Quant | Oncology | Assess the prevalence of psychological morbidity in family caregivers of persons with terminal cancer | Terminal cancer | n = 112 M = 44.45 (15.32) f: 92; m: 20 |

MM-CG-SF | AG | Not defined |

| Benefield et al. 45 | Quant | Nursing | Examine AG experienced by parents when they are informed their critically ill infant must be transferred to a center for special care | Critically ill newborns | n = 202 (101 mother-father pairs) Mmaternal = 25, Mpaternal = not reported f: 50%; m: 50% |

Measure designed by authors, name not mentioned, included ‘7 key items from the study of Kennell’ which were considered to represent a measure of AG expressed after transfer of their baby. | AG | AG as the reaction felt before the actual loss of a loved object assumed a different meaning in this context, since the actual loss never occurred; instead defined by these seven items: feelings of sadness, loss of appetite, inability to sleep, increased irritability, preoccupation thinking about the baby, thinking one had done something to cause the baby’s problem (guilt), and feelings of anger |

| Benfield (1976) 104 | Quant | Nursing | Compare the AG responses of mothers and fathers neonatal ICU experiences over time | Neonatal ICU recipients | n = 70 (35 couples) Mmaternal = 28.6, SD = not provided, Mpaternal = 30, SD = not provided f: 35; m: 35 |

AGS | AG | AG is operationally defined by the items on the included scale: feelings of sadness, anger, difficulty sleeping, change in appetite, preoccupation thinking or dreaming about the baby, irritability, and guilt |

| Beng et al. (2013) 105 | Qual | Nursing | Explore the experiences of informal caregivers of patients in Malaysian palliative care | Palliative care recipients | n = 15 M = not provided f: 10; m: 5 |

Semi-structured questions | AG | Grief reaction that occurs before an impending loss |

| Bielek (2008) 92 | Qual | Oncology | Understand the lived experience of parents who have lost a child to cancer | Cancer, mostly leukemia or lymphoma | n = 8 (4 couples) M = not provided w: 4, m: 4 |

Qual interview guide | AM | The act of mourning when facing a loss whether it is sudden or prolonged |

| Bonanno et al. (2002) 106 | Qant | Psychology | Examine whether bereaved individuals exhibit different patterns of distress following the loss of a spouse | Unspecified | n = 205 M = 72, SD = not provided f: 87.8%; m: 12.2% |

16 items derived from the Bereavement Index, the Present Feelings About Loss Scale and the TRIG. | Chronic grief | Not defined |

| Bouchal et al. (2015) 107 | Qual | Oncology | Explore the retrospective experiences of AG in eight families of people with cancer | Cancer | n = 8 M = not provided |

Qual interview guide | AG, AM | Grief is a reaction to separation, and in the case of AG, it is a reaction to the threat of death rather than death itself |

| Breen et al. (2019) [59] | Quant | Palliative Medicine | Examine PDG as a predictor for outcomes among bereaved caregivers and non-caregivers | Mixed, mostly cancer (check this) | ncaregivers = 38, nmatchedcomparison = 32 M = not reported fcaregivers: 68.4%; mcaregivers: 26.3%; missingcaregivers: 5.3%; fcomparison: 68.8%; mcomparison: 31.3%; missingcomparison: 0% |

HGRC; PG-12 | PDG | Not defined |

| Broom et al. (2019) 108 | Qual | Oncology | Explore caregiving as a social practice that occurs across dying and bereavement | Cancer | n = 15 M = not provided, Age range = 40–80 w: 10; m: 5 |

Qual interview guide | None | Not defined |

| Burke et al. (2015) 36 | Quant | Palliative Medicine | Explore risk factors for AG in a sample of family members preparing for the death of their veteran family member | Varied, mostly cancer (check this) | n = 57 M = 56.11 (12.97) f: 42; m: 15 |

AGS- with “dementia” replaced to “life-threatening illness” | AG | The process associated with grieving the loss of loved ones in advance of their inevitable death |

| Burke et al. (2019) 109 | Quant | Palliative Medicine | Examine the grieving experience of survivors of veterans and to determine risk factors for PLG distress | Palliative care recipients | n = 35 M = 58.64 (13.25) f: 27; m: 13 |

AGS- with “dementia” replaced to “life-threatening illness” | AG | Not defined |

| Butler et al. (2005) 110 | Quant | Oncology | Explore associations between residual, current, and anticipatory stressors in partners of women with metastatic breast cancer, pre and post-loss | Recurrent breast cancer | n = 50 M = 56.5 (11.3) f: 1; m: 49 |

Anticipation of Loss Inventory | AG, Anticipated loss | Partners’ feelings about the possible impact of losing their wife/partner |

| Carr et al. (2001) 111 | Quant | Psychology | Examine if older adults’ psychological adjustment to spousal death varies based on the death context | Unspecified | n = 210 Mfemales = 69.43 (6.99), Mmales = 73.46 (5.92) f: 151; m: 59 |

Bereavement Index; Present Feelings about Loss; TRIG | Grief during the pre death period | Not defined |

| Carter et al. (2012) 97 | Mixed | Neurology | Examine caregiver grief in Parkinson’s disease across the three domains of the MM-CGI Short Form | Parkinson’s disease | n = 74 M = 69.2 (8.2) f: 28%; m: 72% |

MM-CGI; What would you say is the biggest barrier you have faced as a caregiver? | PDG, CG | PDG is defined by the MM-CGI: personal sacrifice and burden (i.e., losses of time, freedom, sleep, health), worry and felt isolation (i.e., loss of personal connection to others and worries about the future) and heartfelt sadness and longing (i.e., emotional response to loss of relationship) |

| Chan et al. (2017) 73 | Quant | Neurology | Validate the C-MMCGI-SF among Hong Kong Chinese caregivers of people with dementia | Dementia | n = 120 M = 55.46 (14.89) f: 80; m: 40 |

C-MM-CGI | Grief | The authors discuss diverging opinions for AG in caregivers of PWD: some use AG, the the anticipation of the impending death of family members while others suggest that the grief experienced by these caregivers should include broader physical and emotional reactions in response to various losses |

| Chan et al. (2019) 112 | Quant | Neurology | Evaluate the validity and utility of MM-CGI dimensions in a multiethnic Asian population | Dementia | n = 394 M = 53 (10.7) f: 236; m: 158 |

C-MM-CGI | PDG, CG | Emotive responses as caregivers mourn for the psychological and physical changes in PWD; grief comprise factors unique to caring for PWD (i.e., communication challenges, asynchronous loss, and an ambiguous disease trajectory leading to worry and uncertainty about the future) |

| Chapman & Pepler (1998) 113 | Quant | Oncology | Examine the relationships among AG in family members of people with terminal cancer | Terminal cancer | n = 61 M = 48 (18.3) f: 37; m: 24 |

NDGEI | AG | AG is grief occurring before death |

| Cheng et al. (2019) 114 | Quant | Neurology | Validate CGQ assessing two dimensions of PDG | AD | n = 173 f: 73%; m: 27% |

CGQ | PDG | Sense of loss, such as the eroded personal qualities of the care recipients and the loss of intimacy and companionship, across all stages of dementia |

| Chentsova-Dutton et al. (2002) 115 | Quant | Palliative Medicine | Compare the emotional adjustment and grief intensity of bereaved spouses and adult children caregivers’ pre-loss throughout one-year post-loss | Terminal chronic illness and hospice care recipients | ncaregivers = 48, ncontrols= 36 Mcaregivers = 63, SD = not provided, Mcontrols = 56, SD = not provided fcaregivers: 83%; mcaregivers: 17%; fcontrols: 75%: mcontrols: 25% |

TRIG | None | Not defined |

| Cheung et al. (2018) 44 | Quant | Neurology | Compare AG levels between spousal and adult children caregivers’ of people at earlier or later stages of dementia; to explore the associations with AG | Dementia | n = 108 M = 62.9 (12.6) f: 85; m: 23 |

MM-CG-SF | AG | PDG is a feeling in response to compound serial losses in the dementia process |

| Clayton et al. (1973) 46 | Quant | Psychology Palliative Medicine | Examine the symptoms of bereavement during the terminal illness of the spouses of widows and widowers | Terminal illness | n = 81 M = 61, SD = not provided |

Were provided symptoms (e.g., depressed mood; crying) but no scale identified | AG | The reaction seen in people (usually primary relative) coping with the expected death of someone close |

| Clukey (1997) 116 | Qual | Palliative Medicine Nursing | Retrospectively explore the AG experience of caregivers of family members with terminal illness | Cancer, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Hepatitis C | n=22 M = 53, SD = not provided f: 18; m: 4 |

Qual interview guide | AG | State of transition usually initiated by either the diagnosis of a terminal illness or the prognosis from a physician that no further medical intervention will cure the dying person. |

| Clukey (2003) 90 | Qual | Retrospectively explore AM for family members who had not used hospice or had minimal hospice services | Cancer, stroke, old age (check old age) | n = 9 M = 52.2, SD = not provided, Age range = 36–68 f: 7, m: 2 |

Qual interview guide | AM | AM is a dynamic set of processes that involve emotional and cognitive transitions made in response to an expected loss | |

| Clukey (2008) 116 | Qual | Palliative Medicine; Nursing | Explore the retrospective perceptions of the AM experience of caregivers who had not received hospice services | Dying patients who did not receive hospice care (check this) | n = 9 M = not provided, Age range = 36–68 |

Qual interview guide | AG, AM | AM involves a dynamic set of processes that include emotional and cognitive transitions made in response to an expected loss |

| Coelho et al., (2016) 74 | Quant | Palliative Medicine | Identify the mediators of CG in caregivers | Cancer, cardiovascular disease | n = 64 M = 58.2, SD = not provided f: 82.8%; m: 17.2% |

Modified Bereavement Risk Questionnaire | Grief | Not defined |

| Coelho et al. (2017) 13 | Quant | Oncology | Validate a Portuguese version of the PG–12 | Cancer | n = 94 M = 52.02 (12.87) f: 78.8%; m: 21.3 |

PG-12 | AG, PDG, PLG | Personal losses (i.e., restrictions of autonomy and suppression of their own needs), relational losses (i.e., deprivation of intimacy and reciprocity with the patient) causing intense feelings of grief while the relative is still physically present |

| Coelho et al. (2019) 21 | Qual | Oncology | Qualitatively explore the experience of family caregivers of patients with terminal cancer related to AG in the context of EOL caregiving | Cancer | n = 26 M = not provided, Age Range = 27–78 f: 23, m: 3 |

Qual interview guide | AG | AG is expectations and emotions associated with the fear of losing their significant other |

| Coelho et al. (2021) 20 | Quant | Oncology | Examine the evolution of PGD symptoms and the predictive role of the caregiving-related factors in the FCs’ grieving trajectory from pre- to post-death | Cancer | n=156 M=51.78 (13.29) f: 127; m: 29 |

PG-12 | PDG | Not defined |

| Collins et al. (1993) 23 | Qual | Neurology | Describe family caregiver experiences of loss and grief pre and post-death of PWD | AD, other progressive dementia | ntotal = 350, npostbereaved = 87 M = 66 (11) f: 79%; m: 21% |

Open-ended questions | AG | AG is a psychological response initiated by a person’s growing awareness of the impending loss of a loved one and the associated losses in the past, present, and future |

| Collins et al. (2016) 37 | Qual | Palliative Medicine | Explore the experiences of parents who are providing care for a child with a life-limiting condition in Australia | Life-limiting condition | n = 14 M = 40, SD = not provided f: 12; m: 2 |

Semi-structured interviews | AG | Not defined |

| D’antonio (2014) 117 | Quant | Oncology | Examine AG and AM, comparing the terms and examining both terms within the case study | Cancer | n = 1 M = 72, SD = N/A f: 0, m: 1 |

AGS | AG | Mourning is a process whereby one tries to cope with loss and the ensuing grief |

| DeCaporale et al. (2013) 24 | Quant | Palliative Medicine | Examine grief reactions in current spousal and adult-children caregivers and in-home respite utilization over 3 months | Cognitive and physical conditions | n = 72 M = 69.8, SD = not provided f: 20.1%; m: 79.9% |

MM-CGI-SF-Heartfelt Sadness and Longing Subscale | AG | AG is the process of mourning, coping, interaction, planning and psychological reorganization’ that occurs as a result of the impending loss of a loved one |

| Dempsey et al. (2020) 118 | Qual | Neurology | Explore the experience of carers who provide EOL care for a person with late-stage dementia at home | Late stage dementia | n = 23 M = not provided f: 70%; m: 30% |

Qual interview guide | Dementia grief | An experience of questioning the self and their own sanity, struggle to care and burden of care |

| Dighe et al. (2008) 38 | Qual | Oncology | Identify concerns of parents of children with advanced, incurable cancers, and to elicit their attitudes toward revealing the diagnosis and prognosis to the sick child | Advance cancer | n = 31 M = not provided |

Qual interview guide | AG | Not defined |

| Dillon (2016) 54 | Quant | Neurology | Examine how adult-child caregivers for parents with dementia experience depression and AG | Dementia | n = 3 M = 55.16, SD = not provided f: 42; m: 8 |

MM-CGI | AG | AG can be defined as the experience of grief prior to the physical death of a person |

| Dionne-Odom et al. (2016) 119 | Quant | Oncology | Test the effect of palliative care telehealth support on bereaved family caregivers | Cancer | n = 44 M = 61.6 (10.1) f: 37; m: 7 |

PG-12 | Grief | Pathological grief over the past-month measured pre-death |

| Duggleby et al. (2013) 120 | Mixed | Oncology | Evaluate the Living with Hope Program in rural women caregivers of persons with advanced cancer | Cancer | n = 36 M = 59 (11.6) f: 36; m: 0 |

NDRGEI; Questions were part of the Living with Hope Program in the form of a hope directed journaling activity entitled “Stories of the Present” | Grief, Loss | Grief that is not associated with the death of a person (e.g., existential concerns, depression, tension and guilt, physical distress) |

| Duke (1998) 39 | Qual | Palliative Medicine | Explore AG through a Heideggerian phenomenological approach | Terminal malignant disease (cancer? check) | n = 4 M = not provided |

Qual interview guide | AG | Not defined |

| Elliott & Dale (2007) 121 | Qual | Oncology | Illustrate the impact of AG on people with learning disabilities through three case studies | Cancer | n = 3 M = not provided |

Questions unspecified | AG | Provides an overview of various definitions in literature: the emotional experience a person might have prior to losing someone of significance to him or her |

| Evans (2009) 122 | Qual | Oncology | Explore the experience of AG and cancer among individuals living with cancer, their primary caregivers, and their families | Cancer | n = 22 M = not provided |

Qual interview guide | AG | AG is a profound emotional response to impending, irreversible loss, which may be experienced by both dying people and their loved ones |

| Ford et al. (2013) 123 | Mixed | Neurology | Examine the lived experience of three wives caring for husbands with dementia | Dementia | n = 3 M = not provided f: 3; m: 0 |

Qual interview guide | Psychosocial death | Irreversible mental deterioration, unlike physical death that is not a terminal event |

| Fowler et al. (2013) 25 | Quant | Neurology | Measure involvement in medical decision making and if AG is associated with problem-solving in family caregivers of older adults with cognitive impairment | Dementia | n = 73 M = 64.9 (11.28) f: 78.1%; m: 21.9% |

AGS | AG | AG is the process of experiencing the phases of normal bereavement in advance of the loss of a loved one |

| Francis et al. (2015) 124 | Mixed | Oncology | Explore the medical compared to the social perspective of grief and depression | Cancer | n = 199 M = 54.8, SD = not provided f: 81.4%; m: 18.6% |

BEQ | Grief | A normative emotional response to loss; extreme sadness appropriate to the situation |

| Frank (2008) 125 | Mixed | Neurology | Explore links between AG for family caregivers of PWD | Dementia | n = 415 M = 60.5, SD = not provided |

MM-CGI | AG, AM | AG comprises past, present, and future losses; AM is “leaving without saying goodbye,” where the person is still psychologically present although physically absent. In the second form, the person remains physically present but psychologically absent (i.e., “the goodbye without leaving”) |

| Fronzaglia (2009) 55 | Quant | Neurology | Examine the relationship between AG and satisfaction with life in rural Alzheimer’s caregivers | AD | n = 74 M = 65.49, SD = not provided f: 73.6%; m: 26.4% |

MM-CGI | AG | Grief that occurs in recognition of the fact that the person is going to die |

| Garand et al. (2012) 126 | Quant | Neurology | Examine differences of AG between family caregivers of persons with a new diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and associations with AG | MCI, AD | n = 73 M = 64.88 (11.27) f: 57; m: 16 |

AGS | AG | AG refers to the process of experiencing the phases of normal bereavement in advance of the loss of a significant person |

| Giannone-Tyler (2016) 32 | Qual | Oncology | Understand the lived experiences of elderly women grieving the death of their husbands | Cancer | n = 4 M = not provided, Age range = 67–78 f: 4; m: 0 |

Qual interview guide | PDG | The grief process that a person experiences before a loss actually occurs giving advance warning of impending death and helping to mitigate grief reactions once death has occurred |

| Gilliland & Fleming (1998) 127 | Quant | Palliative Medicine; Nursing; Oncology; Neurology | Assess the influence of a number of factors on AG and conventional grief reactions | Terminal illness unspecified (check this) | n = 93 Mpalliative = 62, Mchroniccare = 68.58, Mcontrol = 55.29 wpalliative: 63.3%; mpalliative: 36.7%; wchronic: 53.3%; mchronic: 46.7% |

Grief Experience Inventory | AG | Grief before the loss of someone with a chronic illness |

| Givens et al. (2011) 8 | Quant | Neurology | Describe pre-loss and post-loss grief symptoms among family members of nursing home residents with advanced dementia, and to identify predictors of post-loss grief | Dementia | n = 123 M = 59.6 (10.6) f: 75; m: 48 |

PG-12 | PLG | Not defined |

| Glick et al. (2018) 48 | Quant | Nursing; Psychology | Evaluate AG in the ICU setting | Unspecified | n = 50 M = 55.5 SD = not provided f: 72%; m: 28% |

AGS | AG | AG is the experience of grief before the death of a mourned individual |

| Guerrero (2012) 88 | Quant | Neurology | Investigate the relationship between frontal systems behavioral functioning and the experience of grief and burden on spousal caregivers of persons with frontotemporal lobar degeneration | Frontotemporal lobar degeneration | n = 76 M = not provided w: 91.2%; m: 8.8% |

MMCGI-SF | CG | Grief prior to death of the care recipient; caregiver grief is comprised of sadness and longing, worry and felt isolation, and personal sacrifice and burden |

| Gunnarsson & Ohlen (2006) 128 | Qual | Oncology | Retrospectively explore meaning(s) of spouses’ grief before their partners’ death after being admitted to a palliative home care team | Advanced cancer | n = 12 M = not provided w: 75%; m: 25% |

Qual interview guide | AG | Grief before the loss |

| Hampe (1975) 129 | Qual | Nursing | Examine if spouses caring for their terminally ill partners can recognize their own needs and nurses who help them | Terminal illness unspecified | n = 27 M = not provided f: 42.7%; m: 57.3% |

Qual interview guide | AG, Grief | AG is before the actual loss of a valued mate; dependent upon the spouse’s awareness of the impending loss |

| Hicken et al. (2017) 40 | Mixed | Neurology | Test the efficacy of the “Supporting Caregivers of Rural Veterans Electronically” program | Check this | n = 229 M = 70.16, SD = not provided f: 92.6%; m: 7.4% |

MM-CGI-SF | AG | Not defined |

| Higgs et al. (2016) 33 | Qual | Nursing; Palliative Medicine | Examine parents’ perspectives of having a child with Spinal Muscular Atrophy type 1, from diagnosis to bereavement | Spinal muscular atrophy | n=13 M = not provided f: 7; m: 6 |

Questions unspecified | AG | Grief experienced in anticipation of a loss that has yet to occur |

| Hill et al. (1988) 130 | Quant | Psychology | Examine the role of anticipatory bereavement in the adjustment to widowhood in older women | Unspecified, patients had died within the last 2–4 weeks | n = 95 M = 66.5, SD = not provided f: 95, m: 0 |

TRIG | Anticipatory bereavement | Grief reaction before the actual death |

| Hinton (1994) 75 | Mixed | Oncology | Evaluate the circumstances of location of death and quality of life in both relatives and patients | Terminal cancer | n = 77 M = 60 (14) w: 34; m: 43 |

No grief measure reported | Grief | Not defined |

| Hisamatsu et al. (2020) 131 | Qual | Oncology | Follow spouses of patients with palliative chemotherapy discontinuation until bereavement in Japan | Cancer | n = 13 M = not reported w: 1; m: 1 |

Qual interview guide | AG | AG of the family caregivers may be a highly stressful experience; their experiences during the patient’s battle with cancer affect them even after bereavement and have the potential to facilitate appropriate grief work |

| Holley & Mast (2009) 132 | Quant | Neurology | Understand which aspects of the caregiving situation may lead to greater levels of AG | Dementia | n = 80 M = 60.53 (12.66) w: 73.8%; m: 26.2% |

MM-CGI | AG | AG is a multifaceted concept that encompasses emotional reactions to the impending loss of a loved one and associated losses in the past, present, and future |

| Holley & Mast (2010) 26 | Quant | Neurology | Investigate AG in dementia caregivers; examine correlates of caregiver grief; and relationship between AG and caregiver burden | Dementia | n = 80 M = 60.53 (12.36) f: 59; m: 21 |

AGS; MM-CGI | AG | AG is the psychological experience occurring from the point of recognition and acceptance of the impending death until the time of death |

| Holm et al. (2019) 64 | Quant | Palliative Medicine | Evaluate the psychometric properties of AGS in a sample of family caregivers in palliative care | Palliative care recipients | n = 270 M = 61.0(14) w: 184; m: 86 |

AGS | AG | Grief, which is the psychological physiological response to a person’s death, before said close person’s death |

| Holm et al. (2019) 61 | Quant | Palliative Medicine | Investigate associations between PDG and post-death grief and potential moderators | Advanced illness | n = 128 M = 62 (13.2) f: 66.4%; m: 33.6% |

AGS | PDG | Grief that might begin long before the actual death; in some cases already starts when they receive information about a diagnosis of incurable illness, while others continue to invest in the patient’s recovery; grief before an expected death has been associated with characteristics similar to those often observed after the death: emotional distress, frustration, hope, and ambivalence; PDG aso differs from post-death grief because it involves losing a person who is still physically present |

| Holm et al. (2019) 133 | Quant | Palliative Medicine | Investigate longitudinal variations in grief, symptoms of anxiety and depression, and self-rated health | Palliative care recipients, mostly cancer | n = 117 M = 62(13.1) w: 75; m: 42 |

AGS | PDG | Referred to as the experience before death |

| Hovland (2018) 134 | Qual | Neurology | Explore the EOL and PDG experiences for bereaved family caregivers of older adults with dementia | Dementia | n = 36 M = 64, SD = not provided f: 81%; m: 19% |

Qual interview guide | PDG | A reaction to perceived losses throughout the caregiving process and in anticipation of the death |

| Hudson et al. (2011) 81 | Quant | Oncology | Examine the psychological and social profile of family caregivers on commencement of receiving palliative care services | Cancer, non-cancer | n= 301 M = 56.52 (13.89) f: 220; m: 79 |

PG-12 | PLG | Grief is a process involving some elements of “loss,” which starts before the bereavement and can be onerous |

| Jain et al. (2019) 69 | Quant | Neurology | Identify the clinical relationship between grief, depression and mindfulness and identify neural predictors of symptomatology and improvement | Dementia | n = 23 M = 60 (11) f: 21; m: 2 |

MM-CGI-SF | PDG | PDG are reactions that may occur prior to death when observing and caring for a loved one afflicted with a serious illness such as dementia |

| Johansson & Grimby (2012) 50 | Quant | Oncology | Explore the feelings and expressions of AG | Cancer | n = 49 M = 56.9 (17.4) |

AGS | AG, Preparatory grief | AG is prolonged and occurs even before a person dies; compared to conventional grief, AG has been associated with higher intensities of anger, loss of emotional control, and atypical grief |

| Johansson et al. (2013) 135 | Mixed | NeurologyOncology | Compare reactions on the AG scale of relatives of PWD with relatives of cancer patients | Dementia, cancer | n = 102 Mdimentia = 62.3 (13.3), Mcancer = 56.9 (17.4) Fdementia: 53; mdementia: 53; fcancer: 49; mcancer: 49 |

AGS; Semi-structured questions | AG | AG, compared to grief after death, is associated with higher intensities of anger, loss of emotional control, and atypical grief; and despite the experience of AG, the grief after the death of a loved one is not likely to be lessened |

| Kiely et al. (2008) 62 | Quant | Neurology | Identify factors associated PDG symptoms among health care proxies of nursing home residents with advanced dementia | Dementia | n = 315 M = 59.9 (11.5) f: 63%; m: 27% |

PG-12 | PDG | PDG is the loss experienced by family members of dementia patients before their actual death; multiple losses, sometimes referred to as “triple grief”: first they grieve loss of the patients’ personhood before their actual bodily death, next experience loss at the time of nursing home admission, finally loss when the patient ultimately dies |

| Kilty et al. (2019) 136 | Qual | Neurology | Explore the experience of family caregivers of persons with young-onset dementia and use of support services | Dementia | n = 6 M = 55, SD = not provided f: 3; m: 3 |

Semi-structured interview; questions not reported | AG, Ambiguous loss | Loss that can occur when a family member remains physically present, but because of the dementia process, the caregiver experiences reduced connection and support from the person with dementia over time; a complex concept with grief experienced in anticipation of future loss of a loved one |

| Kobiske et al. (2019) 70 | Quant | Neurology | Examine the moderating effects on the relationship between PDG and perceived stress among young-onset dementia caregivers | Dementia | n = 104 M = 104 f: 68; m: 36 |

MM-CGI-SF | PDG | Losses experienced by a caregiver |

| Lai et al. (2017) 137 | Quant | Oncology | Investigate the course of psychological symptoms, emotional and social abilities in caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients from 1 months before loss to 14 months after | Cancer | n = 60 M = 75 (11) f: 43; m: 17 |

PG-12 | AG | AG is a reaction that occurs in the caregiver before an impending loss; a psychological mechanism characterised by emotional stress, intense pre-occupation with the dying, longing for his/her former personality, loneliness, fearfulness, irritability, anger and social withdrawal |

| Lane (2007) 51 | Quant | Unspecified | Explore the potential predictors of AG | Unspecified | n = 70 M = 54.7 (12.7) f: 63; m: 7 |

AGS | AG | AG is any grief occurring prior to a loss, as distinguished from the grief that occurs at or after a loss |

| Li et al. (2019) 94 | Quant | Neurology | Evaluate the Mandarin version of the MM-CGI-SF; grief of family caregivers of patients with dementia; and predictors of grief | Dementia | n = 91 M = 52.19 (14.35) f: 65.9%; m: 34.1% |

MM-CGI-SF | Grief in caregivers | Grief in dementia caregivers defined as “true grief,” which can reflect the qualities and intensities of caregivers’ grief after the dementia patient dies; includes various physical and emotional reactions due to various losses of the dementia patients |

| Liew (2016) 65 | Quant | Neurology | Explore the prevelance of pre-death grief in a multi-ethnic Asian population using the MM-CGI | Dementia | n = 72 M = 50.9 (11.6) f: 58.3%; m: 41.7% |

MM-CGI | PDG | PDG is the emotional response as dementia family caregivers mourn for the psychologically absent patient and anticipate impending losses |

| Liew & Yap (2020) 86 | Quant | Neurology | Develop a briefer scale than the MM-CGI-SF, while still capturing the essence of caregiver grief | Dementia | n = 394 M = 53(10.7) f: 236; m: 158 |

MM-CGI; MM-CGI-SF | CG | The experience of grief and loss in dementia caregiving, characterized by multiple losses within the context of caregiving, including the anticipation of future losses related to physical death of the PWD and the ambiguous loss of the PWD who is physically present but increasingly disconnected from the caregiver |

| Liew et al. (2018) 67 | Quant | Neurology | Determine differences in the risk factors of PDG and caregiver burden | Dementia | n = 394 M = 53 (10.7) f: 256; m: 138 |

MM-CGI | PDG | Emotional, cognitive, and behavioral responses to the multiple losses in caregiving; include ambiguous loss due to increasing disconnectedness from the PWD who is physically present but psychologically absent; and the anticipation of future losses relating to the physical death of the person |

| Liew et al. (2018) 85 | Quant | Neurology | Produce a Mandarin-Chinese version of MM-CGI and evaluate its psychometric properties | Dementia | n = 394 M = 53 (10.7) f:236; m: 131 |

MM-CGI | PDG | PDG is the caregivers’ responses to perceived losses in the pre-death context; anticipation of future loss related to the physical death of PWD; and the mourning of present loss related to the psychological death of PWD, whereby they are still physically present but emotionally disconnected |

| Liew et al. (2019) 66 | Quant | Neurology | Compare the effects of baseline grief and burden on caregiver depression at baseline and 2.5 years later | Dementia | n = 131 M = 53.1 (11.0) f: 58.3%; m: 41.7% |

MM-CGI | CG | For caregivers of PWD, bereavement that is before the physical death; multiple losses within the context of caregiving, including the ambiguous loss of the person with dementia who is physically present but becomes increasingly disconnected from the caregiver |

| Liew et al. (2019) 84 | Quant | Neurology | Construct screening tool based on factors associated with caregiver grief to identify those at greater risk of high grief | Dementia | n = 300 M = 52.1 (11) f: 60%; m: 40% |

MM-CGI | CG | Loss and grief are experienced by caregivers of PWD; ambiguous loss of PWD even when they are still alive; and anticipation of future loss related to their physical death |

| Lou et al. (2015) 138 | Qual | Oncology | Retrospectively explore maternal experiences of anticipatory loss of families of a child with advanced cancers | Brain cancer (previously tumor check this) | n = 10 M = 42, SD = not provided |

Qual interview guide | Anticipated loss | Anticipated loss as the family’s realization of the meaning of the disease and the process of facing the loss of their child in the future |

| MacCourt et al. (2017) 95 | Mixed | Neurology | Determine the effect of a grief management coaching intervention for caregivers of individuals with dementia | Dementia | n = 200 M = 64.4, SD = not provided f: 79%; m:21% |

MM-CGI | Grief in caregivers | Not defined |

| Marwit & Kaye (2006) 96 | Quant | Neurology | Investigate the properties of MM-CGI-SF for caregivers of patients with acquired brain injury | Brain injury | n = 28 M = 55.22 (14.25) f: 25; m: 5 |

MM-CGI-SF | Grief in caregivers | Not defined |

| Marwit & Meuser (2002) 87 | Mixed | Neurology | Develop an instrument for the assessment of grief in caregivers of persons with AD | Dementia | n = 166 Madultchild = 51.81 (8.05), Mspouse = 71.47 (8.93) fadultchild: 73; madultchild: 10; fspouse: 62; mspouse: 21 |

MM-CGI | CG | Complicated grief as divided into AG reactions and bereavement; pre- and post-death grief, are unique phenomena from each other and other psychiatric diagnoses |

| Marwit & Meuser (2005) 139 | Quant | Neurology | Derive a short-form of the existing MM-CGI and establish preliminary reliability and validity | Dementia | n = 292 M = not provided, f: 76.4%; m: 23.6% |

AGS; MM-CGI-SF | PDG, CG | Grief before death |

| Marwit et al. (2008) 68 | Quant | Oncology | Examine the MM-CGI psychometric and validity properties in caregivers of persons with cancer | Cancer | n = 75 M = 52.8 (12.8) f: 69.3%; m: 30.7% |

MM-CGI | PDG | Grief within the emotional reactions of ‘pre-death’ loss among caregivers of people with chronic/debilitating and life-threatening conditions, including dementia, where a series of cognitive, emotional, and social losses precede death; caregiver grief is considered a unique affect, similar to bereavement, discriminable from depression and anxiety, and associated negatively with caregiver health, social relations, and post-death bereavement |

| McLennon et al. (2014) 140 | Qual | Neurology | Understand African-American caregivers PDG experiences; to assess the validity of items on the MM-CGI-SF | Dementia | n = 19 M = 60 (13.5) f: 16, m: 3 |

MM-CGI-SF | PDG | PDG experienced by AD caregivers is similar to AG, grief in anticipation of death to come; developed from deep feelings of loss and sadness experienced by caregivers as they watch the gradual deterioration of the personality and memory of their loved one into “dependent shadows of their former selves”, also referred to as “psychosocial death” |

| McRae (2005) 141 | Qual | Neurology | Examine the phenomenological experience of daughters-in-law caring for a parent-in-law with dementia | Dementia | n = 11 M = 50, SD = not provided f: 11; m: 0 |

Qual interview guide | AG | The experience of current losses or the anticipation of loss and grief |

| Meichsner & Wilz (2018) 142 | Quant | Neurology | Examine if a cognitive-behavioral intervention increases caregivers’ coping with PDG | Dementia | n = 273 M = 64.20 (11.04) f: 80.6%; m: 19.4% |

Caregiver Grief Scale | PDG | PDG is defined as the ‘emotional and physical response to the perceived losses in a valued care recipient’ |

| Meichsner et al. (2019) 143 | Qual | Neurology | Illustrate how dementia caregivers experience loss and PDG, and examine how therapists respond to this grief | Dementia | n = 273 M = not provided |

Questions unspecified | PDG | Emotional and physical response to the perceived losses in a valued care recipient |

| Meuser & Marwit (2001) 41 | Mixed | Neurology | Develop a stage-sensitive, caregiver-specific model of grief for a measure of dementia caregiver grief | Dementia | n = 87 MAdultchild = 51.6 (9.6), Mspouse= 71.8 (9) w: 20; m: 67 |

AGS; MFG | AG | Not defined |

| Mulligan (2011) 60 | Quant | Neurology | Identify areas of overlap and disjunction between the PG-12 and the MM-CGI-SF | Dementia | n = 202 M = 67.67 (11.52) f: 148; m: 54 |

MM-CGI-SF; PG-12 | PDG | Symptoms include yearning for the family member to be healthy again and feeling shocked about the person’s illness |

| Nanni et al. (2014) 144 | Quant | Oncology | Examine the relationship between pre and post-loss criteria for CG and the validity of ICG for Italian caregivers | Cancer | n = 60 M = 60.3 (12.08) f: 75%; m: 25% |

ICG-PL | Pre-loss caregiver grief | A syndrome characterized by emotional, behavioral and cognitive symptoms (e.g. yearning, searching, detachment, numbness, bitterness, emptiness, and lost sense of trust and control) named as: complicated grief, then traumatic grief, and, more recently, prolonged grief |

| Neyshabouri et al. (2018) 56 | Quant | Oncology | Compare AG of mothers of children diagnosed with cancer within the previous month to those diagnosed 6–12 months earlier | Cancer | n = 70 M1month = 32.27, M6–12month = 33.12 f: 100%; m: 0% |

MM-CGI | AG | An active process of being sad that occur prior to actual loss |

| Nielsen et al. (2016) 82 | Quant | PsychologyPalliative Medicine | Describe PLG and other relevant outcomes in caregivers to terminally ill patients | Terminal illness | n = 3560 M = 61.2, SD = not provided f: 66.6%; m: 29.4% |

PG-13 | PLG | Not Defined |

| Nielsen et al. (2017) 83 | Quant | Oncology | Investigate whether severe preloss grief and depressive symptoms, caregiver burden, preparedness for death, communication about dying, and socioeconomic factors predict CG and postloss depressive symptoms | Cancer | n = 3635, 38% bereaved w/in 6mo, of these 88% completed T2 M = 62 f: 70%; m: 30% |

PG-12 | PLG | Not defined |

| Nielsen et al. (2017) 9 | Quant | Oncology | Explore associations between severe PLG symptoms in caregivers and modifiable factors | Cancer | n = 2865 M = 61, SD = not reported f: 69%; m: 31% |

PG-12 | AG, PLG | PLG and AG as grief symptoms in caregivers before death have been; can be described as a grief reaction due to multiple losses during end-of-life caregiving |

| Olson (2014) 145 | Qual | Oncology | Explore cancer carers’ experiences of loss with Australian carers of a spouse with cancer | Cancer | n = 32 Age range = 30–89 f: 14; m: 18 |

Qual interview guide | AG, Indefinite loss | AG experienced at the end of a patient’s life; AG occurs when the emotions related to loss arise a substantial time before the person stops breathing |

| Ott et al. (2007) 93 | Quant | Neurology | Describe the grief experience of spouses and adult children of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias | Dementia | n = 201 M = 64.07 (13.88) f: 80.6%; m: 19.4% |

MM-CGI-SF | Grief in caregivers | Grief as the reaction to the perception of loss with normative symptoms including yearning, sadness, anger, guilt, regret, anxiety, loneliness, fatigue, shock, numbness, positive feelings, and a variety of physical symptoms that are unique to the individual |

| Ott et al. (2010) 80 | Quant | Neurology | Determine if the Easing the Way intervention is feasible for caregivers of spouses with dementia | Dementia | n = 23 M = 73.5, SD = not provided f: 75%; m: 25% |

MMCGI-SF | Grief | Increased sadness and longing, worry and isolation, and personal sacrifice burden |

| Park et al. (2018) 146 | Quant | Neurology | Examine the relationships among burnout, depressive symptoms, social support, and psychological wellbeing in caregivers of PWD | Dementia | n = 606 M = 60.5 (10.6) f: 88.9%; m: 10.6% |

MM-CGI | AG, CG | An emotional reaction to actual or perceived losses among caregivers marked by increased sadness and longing, worry and isolation, and personal burden; in caregivers, grief starts with early signs of dementia in the family member and continues through the stages of dementia; AG is defined as anticipation of the loss of a family member |

| Ponder & Pomeroy (1996) 42 | Quant | Neurology | Provide evidence of the intensity, nature and persistence of AG among caregivers of PWD | Dementia | n = 100 M = 56.6, SD = not provided f: 83 m: 17 |

GEI-Loss Despair Scale; Stage of Grief Inventory; self-developed scale | AG | Not defined |

| Pote (2017) 98 | Quant | Neurology | Understand the effect of perceived closeness and attachment styles of spousal caregivers of individuals with dementia | Dementia | n = 90 M = not reported f: 66; m: 24 |

MMCGI-SF | AG | AG is the process whereby individuals mourn the approaching death of a loved one, particularly through the physical and cognitive decline that plagues individuals who are at a terminal stage in life |

| Pote & Wright (2018) 57 | Quant | Neurology | Evaluate AG as a moderator for marriage and life satisfaction in spousal caregivers of dementia patients | Dementia | n = 90 M = 63, SD = not provided f: 66; m: 24 |

MM-CGI-SF | AG | AG is a process that many informal caregivers go through and involves a series of losses that stem from their loved one’s progression of cognitive and physical decline |

| Prigerson et al. (2019) 43 | Mixed | Nursing; Psychology | Investigate effects of the EMPOWER intervention for surrogate decision-makers of critically ill ICU patients | Critically ill ICU patients | n = 60 | FOLLOS; PG-12 | AG | Not defined |

| Rankin (2011) 59 | Quant | Oncology | Examine how coping styles influence seeking social support for carers of persons with cancer | Cancer | n = 103 M = 49.57 (12.43) f: 68; m: 35 |

WOC | PDG | Grief experienced by caregivers prior to the death of the patient in response to the many losses that accompany the cancer diagnosis of a loved ones |

| Rider (1994) 52 | Quant | PsychologyPalliative Medicine | Examine the effects of ambiguity of loss and type of relationship on AG in family caregivers of chronically ill patients | Terminal illness | n = 53 M = 46.4, SD = not provided f: 86.8%; m: 13.2% |

AGS-CIV; RAGC; TRIG-CIV1 | AG | A multifaceted process occurring over time, involving physical, cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and social reactions or tasks in response to the death of a loved one; efforts at coping with and resolving the loss are part of this grief process; also called post-death grief |

| Riley et al. (2013) 147 | Quant | Neurology | Develop a measure on spousal carers’ perception of their relationship as “continuous” | Dementia | nstudy1 = 51, nstudy2 = 84 Mstudy1 = 73 (7.6), Mstudy2 = 71.6 (7.8) fstudy1: 23, mstudy1: 28; fstudy2: 58, mstudy2: 26 |

Birmingham Relationship Continuity Measure | Relationship continuity, Negative emotions related to the relationship | Feelings of loss and negative emotions related to whether the spouse experiences the relationship as essentially changed and radically different relationship |

| Rini & Loriz (2007) 89 | Qual | Nursing; Palliative Medicine | Describe the role of AM in parents who recently experienced the death of a hospitalized child | Mixed cause of death (check this) | n = 11 M = not provided f: 9; m: 2 |

Qual interview guide | AM | AM is the process of emotional preparatory experience leading up to the time of death, formerly termed AG; AM describes not only the process of grief but other processes as well; AM encompasses seven operations according to Rando (2001): grief and mourning, coping, interaction, psychosocial reorganization, planning, balancing of conflicting demands, and facilitation of an appropriate death |

| Romero et al. (2014) 71 | Quant | Neurology | Identify predictors of higher levels of grief in bereaved caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s prior to death | AD | n = 66 M = 64.3, SD = not provided f: 88%; m: 22% |

MMCGI-SF | PDG | PDG results from losses in the quality of the original relationship, roles, well-being, intimacy, health status, social interaction, communication, and opportunities to resolve issues from the past |

| Ross & Dagley (2009) 27 | Quant | Neurology | Explore the reliability of the MM-CGI and AG as a multi-cultural phenomenon among caregivers of patients with dementia | Dementia and cardiac patients | n = 176 M = not provided f: 45.5%; m: 54.5% |

MM-CGI-SF | AG | Grief process of individuals who are losing someone slowly, expectedly, and many times, in stages |

| Saldinger & Cain (2004) 148 | Qual | Oncology | Explore the extent to which spouses take advantage of their partner’s terminal illness for cognitive, emotional, practical, and interpersonal accommodation to impending death | Cancer | n = 30 M = not provided |

Qual interview guide | AG | Cognitive, emotional, practical, and interpersonal accommodation to impending death. |

| Sanders et al. (2008) 77 | Mixed | Neurology | Describe the experience of spouses and adult children who are caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. | AD and dementia | n = 44 M = 65.18, SD = not provided f: 86%; m :14% |

MM-CGI-SF | Grief | The reaction to the perception of loss |

| Singer et al. (2021) 7 | Quant | Neurology; Oncology | Examine changes in PLG among individuals whose family member has a life-limiting illness | Cancer, dementia | nbaseline = 138, n1month = 61 M = 62.81 (14.41) f: 70.8%; m: 29.2% |

PG-12 | PLG | The impending loss of their loved one or the loss of their pre-diagnosis relationship or the loss of their pre-diagnosis relationship with the loved one (e.g.. yearning for the individuals to be as they were before the illness) |

| Stajduhar et al. (2010) 76 | Mixed | Oncology | Understand why some family caregivers cope better than others even under similar caregiving demands | Cancer | n = 14 Msample1= 63, Age rangesample2= 46–57 fsample1: 73.7%; msample1: 26.3%; fsample2: 92.9%; msample2: 7.1% |

Questions unspecified | Grief | Not defined |

| Swensen et al. (1992) 28 | Mixed | Oncology | Examine the relationship between married couples when one of the spouses is dying of terminal illness | Various cancers, others unspecified, healthy controls | nexperimental = 114, ncontrol = 100 Mexperimental = 58.6, SD = not provided, Mcontrol = 58.4, SD = not provided |

The Marriage Problems Scale; The Scale of Feelings and Behavior of Love | AG | In AG, spouses can move closer behaviorally or socially, while starting to move away intra-psychically |

| Theut et al. (1991) 29 | Quant | Neurology | Assess the validity and reliability of the AGS scale in documenting AG in carers of spouses of patients with dementia | Dementia | n = 27 M = 68.1, SD = not provided f: 100%; m: 0% |

AGS | AG | The process of slowly experiencing the phases of normal post-death grief in the face of a potential loss of a significant person |

| Tomarken et al. (2006) 149 | Mixed | Oncology | Examine differences in caregiver age groups and potential risk factors for CG pre-death | Cancer | n = 248 M = 52 (13.67) f: 73%; m: 27% |

Pre-ICG | Complicated grief pre-death | Complicated grief pre-loss is an AG reaction prior death; unique phenomena from post-death grief with different psychiatric diagnoses |

| Toyama & Honda (2017) 30 | Qual | Oncology | Examine the influence of a narrative approach AG in family caregivers of patients with terminal illness | Terminal illness | n = 10 M = not provided f: 80%; m: 20% |

Narrative approach | AG | The grief reaction that occurs in anticipation of an impending loss |

| van Doorn et al. (1998) 150 | Quant | Psychology Palliative Medicine |

Test pre-loss effects of having a security-enhancing marriage on traumatic grief and depressive symptoms among caregivers of terminally ill spouses | Cancer, AD, stroke, heart-related problems, “other” serious illness | n = 59 M = 66.2 (9.1) |

HRSD; ITG-pre-loss | Depressive symptoms, Traumatic grief | Certain symptoms of grief (e.g., yearning, searching, preoccupation with thoughts of the deceased, avoidance of reminders of the deceased) that predict impaired global functioning, such as poor sleep, sad mood, and low self-esteem at 18 months post-loss |

| Waldrop (2007) 78 | Mixed | Palliative Medicine | Explore grief during a terminal illness and after the care recipient’s death | Patients in hospice care | n = 30 M = 64.1, SD = not provided f: 77%; m: 23% |

TRIG; BSI | Grief | The multifaceted response to death and losses of all kinds, including emotional (i.e., affective), psychological (i.e., cognitive and behavioral), social, and physical reactions |

| Walker & Pomeroy 151 | Quant | Neurology | Measure levels of and distinguish AG and depression in caregivers of patients with dementia | Dementia | n = 100 M = 56.6, SD = not provided f: 83; m: 17 |

GEI-Loss Despair Scale | AG | AG as the “funeral that never ends”; grieving for losses that have already occurred and are currently occurring (e.g., altered relationship or lifestyle; dreams for the future that will not be realized; loss of companionship, security, economic certainty) |

| Walker & Pomeroy(1996) 152 | Quant | Neurology | Examine AG and its impact on the current functioning of caregivers | AD and other dementias | n = 100 M = 56.6, SD = not provided f: 83%; m: 17% |

Stage of Grief Inventory; Grief Experience Inventory | AG | AG for caregivers caring for persons with a chronic debilitating illness such as Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, grieve for losses that have already occurred and those that are occurring. Such losses may include a relationship and lifestyle that have been altered, dreams for the future that will never be realized, companionship, security, and economic certainty, in addition to the actual presence of the loved one. |

| Warchol-Biedermann et al. (2014) 79 | Mixed | Neurology | Evaluate the MM-CGI for Polish family caregivers and determinants of grief in carers of Alzheimer’s disease patients | AD | n = 151 M = 58.9, SD = not provided f: 63%; m: 37% |

MM-CGI | Grief | Psychological (emotional, cognitive, functional and behavioral responses) response to a loss such as a death |

| Welch (1982) 153 | Quant | Oncology | Investigate AG in family members of adult cancer patients | Cancer | n = 41 M = 44, SD = not provided f: 25; m: 16 |

12-item Faschingbauer’s Texas Inventory of Grief. | AG, Unresolved grief | AG as cyclical periods of mental anguish and feelings of loss that begin at the time of initial diagnosis of a malignancy, in expectation of the deprivation of a significant relationship and social role through the expected death of a loved one. |

| Wong & Chan (2007) 154 | Qual | Oncology | Understand the experiences of Chinese family members of terminally ill patients during the EOL | Cancer | nfcg = 19, nhealthcareprofessionals = 14 M = not provided, Age range = 18–60 f: 80%; m: 20% |

Qual interview guide | Grief | Not defined |

| York (2017) 58 | Quant | Neurology | Assess AG and relationship status along with other outcomes | AD | n = 66 M = not provided |

CSI; MMCGI; MSPSS | AG | A model that is comparable to grief, but it anticipates the forthcoming loss of a family member to previously experienced losses from an incurable disease |

| Zamanzadeh et al. (2013) 53 | Quant | Nursing; Palliative Medicine | Evaluate AG reactions among fathers with hospitalized premature infants | Unspecified | n = 120 M = 31.8, SD = not provided f: 0%; m: 100% |

AGS-Farci | AG | A type of grief that happens before the actual loss |

| Zordan et al. (2019) 155 | Quant | Oncology | Prospectively evaluate the prevalence and long-term predictors of PGD in bereaved cancer caregivers | Cancer | nsample1 = 246, nsample2 = 55 Msample1 = 56.4 (13.93), Msample2 = 57.8 (12.40) fsample1: 175; msample1: 70; fsample2: 45; msample2: 10 |

PG-12 | Preloss prolonged grief | Grief related to the illness rather than the death of the person being cared for (i.e., “avoiding reminders of the diagnosis/prognosis” rather than “avoiding reminders of the death”) |

Note. Qual= Qualitaitive. Quant= Quantiative. AD=Alzheimer’s Disease. MM-CGI: Marwit-Meuser Caregiver Grief Inventory. AG=Anticipatory Grief. MM-CGI CC= Marwit-Meuser Caregiver Grief Inventory Childhood Cancer. AM=Anticipatory Mourning. MM-CGI-SF= Marwit-Meuser Caregiver Grief Inventory Short Version. ICU=Intensive Care Unit. M=Mean. SD=Standard Deviation. TRIG=The Texas Inventory of Grief. PDG=Pre-Death Grief. HGRC=Hogan Grief Scale. PG-12=Prolonged Grief. AGS=Anticipatory Grief Scale. PLG=Pre-loss grief. C-MMCGI-SF=Chinese Marwit-Meuser Caregiver Grief Inventory Short Version. PWD= psychological well-being. NDGEI=Non-death Version of the Grief Experience Inventory. CGQ=Caregiver Grief Questionnaire. EOL=End of Life. FC=Family caregivers. AGS=Anticipatory Grief Scale. BEQ=Bereavement Experience Questionnaire. MCI=Mild Cognitive Impairment. MFG=Many Faces of Grief Questionnaire. ICG=Inventory of Complicated Grief. ICG-PL=Pre-death Inventory of Complicated Grief. EMPOWER=Enhancing & Mobilizing the POtential for Wellness & Emotional Resilience. FOLLOS=Fears of Losing Loved Ones Scale. WOC=Ways of Coping Questionnaire. AGS-CIV=Anticipatory Grief Scale, Chronic Illness Version. TRIG-CIV1=Texas Revised Inventory of Grief Chronic Illness Version. RAGC=Rando Anticipatory Grief Checklist. BSI=Brief Symptom Inventory. CSI=Caregiver Strain Index. MSPSS=Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support.

In addition to varied terms used to characterize grief in family members of individuals with life-limiting illness, studies used 19 different scales to measure grief. The most prominent were the Marwit-Meuser-Caregiver Grief Inventory (n=28), the Anticipatory Grief Scale (n=18), and the Prolonged Grief-12 (n=13).

Anticipatory Grief

There were 54 studies identified that used anticipatory grief to describe family members’ grief while a person with a life-limiting illness was alive. However, the definitions used for anticipatory grief differed drastically (see Table 1), and many studies used the term anticipatory grief but failed to define it. For example, one study 21 stated that anticipatory grief includes emotions associated with the fear of losing their significant other, whereas another study 22 stated anticipatory grief is a profound emotional response to impending, irreversible loss that is experienced by a family member. Overall, the first definition is related to worry about life without the person with the life limiting illness (e.g., what am I going to do when they pass away). However, the other study22 appears to define anticipatory grief as a feeling of loss following diagnosis of the life limiting illness (e.g., I feel I have already lost the person). Nine studies 23–31 used Rando’s12 definition of anticipatory grief and two 32,33 used Lindemann’s 11 definition of anticipatory grief. Ten studies34–43 used the term anticipatory grief, but did not define it beyond using a measure conceptualized as measuring anticipatory grief. Finally, there was one study44 that defined anticipatory grief as being an emotional response that is specific to a dementia (i.e., “a specific feeling of pre-death grief in response to compound serial losses in the dementia process;” p. 1).

Of the studies that used anticipatory grief, 16 were qualitative. The remaining 38 quantitative studies used a variety of measures, with five studies using author-generated questions that had not been psychometrically validated21,22,28,45,46. The studies using anticipatory grief were mostly conducted with family members of patients with dementia (N=17) or cancer (N=15). Lastly, of the studies that used the term anticipatory grief, the Anticipatory Grief Scale was the most used measure (14 studies; 25,29,36,41,45,47–53). The Marwit-Meuser-Caregiver Grief Inventory 26,27,54–58 and Marwit-Meuser-Caregiver Grief Inventory- Short Form 24,35,40,44 was used in 11 studies.

Pre-death grief

There were 18 studies identified that used pre-death grief to describe grief experienced by family members of a person with a life-limiting illness. Almost all 18 studies differed in their definitions of pre-death grief. For example, Rankin and colleagues 59 defined pre-death grief as grief experienced by family members prior to the death of the patient in response to losses that accompany the diagnosis of a family member, whereas Mulligan 60 defined pre-death grief as yearning for the family member to be healthy again and feeling shocked about the person’s illness. One study 61 used Lindemann’s definition 11. Another study 62 framed grief as a spectrum, which they termed “triple grief” (i.e., grieving the loss of the patients’ personhood, the family’s experience of loss at the time of hospice admission, and the loss when the person dies). Two studies 20,63,64 used the term pre-death grief but did not define it.

Most studies that used pre-death grief were quantitative (N=16) and the remainder were qualitative (N=2). The studies that used the term pre-death grief were mostly with family members of dementia (N=12) and cancer patients (N=3). The remaining studies included family members of individuals with other types of life-limiting illnesses, a mixed sample, or did not specify the illness. Of the 15 quantitative studies, most studies used the Marwit-Meuser-Caregiver Grief Inventory (n=4; 65–68,68, the Marwit-Meuser-Caregiver Grief Inventory- Short Form (n=4; 60,69–71), or the Prolonged Grief-12 (n=4; 20,60,62,63). Two of the studies used multiple measures 60,63.

Grief

Twelve studies used the term, grief, to describe family members’ grief while a person with a life-limiting illness was still alive. Five 72–76 of these studies did not provide a definition of the term. The six studies that used grief differed in their definition of the construct. One study 77 defined grief as the reaction to the perceived loss following the diagnosis of a life-limiting illness. However, another study77 defined it as a “multifaceted caregiver response” (p. 198) to death and losses of all kinds associated with the illness, including grief related to “social” death and intellectual deterioration of a person with some form of dementia.

Most of the studies that used the term, grief, to describe the experience of grief before the death used mixed methods (N=7). Four were quantitative, and one qualitative. Studies were predominantly conducted with family members of cancer (N=5) and dementia (N=4) patients. Two of the studies used the Marwit-Meuser-Caregiver Grief Inventory72,79 and three used the Marwit-Meuser-Caregiver Grief Inventory- Short Form 73,77,80.

Pre-Loss Grief

There were six studies identified that used pre-loss grief to describe family members’ grief while a person with a life-limiting illness was still alive 7–9,81–83. There were two studies 7,81 that defined pre-loss grief, whereas the remaining four studies 8,9,82,83 did not define the construct. Hudson and colleagues 81 defined pre-loss grief as follows: “Grief is a process involving some elements of ‘loss,’ which starts before the bereavement and can be onerous” (p.523). Singer and colleagues 7 similarly used pre-loss grief as more of an umbrella term, defining it as either family members’ grief related to the impending loss of their loved one and/or the loss of components of the relationship with the loved one that existed pre-diagnosis.

All studies that used pre-loss grief were quantitative. Most of the pre-loss grief studies included a mixed sample with respect to illness type. Only one study 8 focused on a single specific illness (i.e., family members of individuals with a dementia). All the studies used the Prolonged Grief-12 to measure pre-loss grief.

Caregiver Grief

There were five studies identified that used the term, caregiver grief, to describe family members’ grief while a person with a life-limiting illness is still alive. Three of the articles were led by the same first author and described caregiver grief as anticipation of future losses related to physical death of a person with dementia 84–86. Marwit and Meuser 87 discussed caregiver grief as a stage-determined, internally consistent construct that is measurable but did not provide an explicit definition. Guerrero 88 defined caregiver grief as feelings of grief, including sadness, longing, worry, felt isolation, personal sacrifice, and burden prior to the death of the care recipient.

Most of the studies that used caregiver grief were quantitative studies (n=4), and one used mixed methods. The studies using the term caregiver grief were predominately conducted with family members of dementia patients and one study included family members of individuals with frontotemporal lobar degeneration. All five studies used some form of the Marwit-Meuser-Caregiver Grief Inventory.

Anticipatory Mourning

There were four studies that used the term, anticipatory mourning, to describe family members’ grief while a person with a life-limiting illness is still alive. Each of the four studies differed in their definition. One study 89 used Rando’s 12 definition. Clukey 90 described anticipatory mourning as a set of dynamic processes involving emotional and cognitive transitions made in response to an expected loss. Angela-Cole 91 defined anticipatory mourning as uncertainty surrounding the amount of time a person with a life-limiting illness has left, which creates a heightened grieving experience before the person dies. Bielek and colleagues 92 defined anticipatory mourning as the act of mourning when facing a loss, whether it is sudden or prolonged. All the studies using anticipatory mourning were qualitative. Two studies 91,92 recruited participants whose family members had “terminal cancer” and two included family members of individuals with any “terminal illness.”

Grief in Caregivers

Four studies used the term, grief in caregivers, to describe family member’s grief while a person with a life-limiting illness is still alive. Two studies 93,94 offered definitions of grief in caregivers, whereas two studies did not define the construct 95,96. Ott and colleagues (2007) 93 used Rando’s 12 definition. Li and colleagues 94 defined grief in caregivers as various physical and emotional reactions due to the various losses associated with dementia.

Three of the four studies were quantitative, and the other study used a mixed design. Three of the studies enrolled family members of dementia patients, and one study enrolled family members who had an acquired brain injury. One of the studies used the Marwit-Meuser-Caregiver Grief Inventory 95, and three used the Marwit-Meuser-Caregiver Grief Inventory- Short Form 93,93,94

Multiple Terms Used

There were 19 studies that used multiple terms (e.g., anticipatory grief and pre-loss grief) within a single article to describe family members’ grief experiences. In all cases, each of the terms were used interchangeably with the same definition applied. For example, Carter and colleagues 97 used pre-death grief, caregiver grief, and grief interchangeably. This study applied the same definition for each of these terms. All three constructs were characterized as involving personal sacrifice and burden, worry and feelings of isolation, and heartfelt sadness and longing, which are key subscales in the Marwit-Meuser-Caregiver Grief Inventory.

Discussion