Abstract

Introduction and Objectives

The Acute Cystitis Symptom Score (ACSS) is a patient self‐reporting questionnaire for clinical diagnostics and patient‐reported outcome (PRO), which may assess the symptoms and the effect on the quality of life in women with acute cystitis (AC). The current study aimed to create a validated Spanish version of the ACSS questionnaire.

Material and Methods

The process of linguistic validation of the Spanish version of the ACSS consisted of the independent forward and backward translations, revision and reconciliation, and cognitive assessment. Clinical evaluation of the study version of the ACSS was carried out in clinics in Spain and Latin America. Statistical tests included the calculation of Cronbach's α, split‐half reliability, specificity, sensitivity, diagnostic odds ratio, positive and negative likelihood ratio, and area under the receiver‐operating characteristic curve (AUC).

Results

The study was performed on 132 patients [age (mean;SD) 45.0;17.8 years] with AC and 55 controls (44.5;12.2 years). Cronbach's α of the ACSS was 0.86, and the split‐half reliability was 0.82. The summary scores of the ACSS domains were significantly higher in patients than in controls, 16.0 and 2.0 (p < 0.001), respectively. The predefined cut‐off point of ≥6 for a summary score of the “Typical” domain resulted in a specificity of 83.6% and a sensitivity of 99.2% for the Spanish version of the ACSS. AUC was 0.91 [0.85; 0.97].

Conclusions

The validated Spanish ACSS questionnaire evaluates the symptoms and clinical outcomes of patients with AC. It can be used as a patient's self‐diagnosis of AC, as a PRO measure tool, and help to rule out other pathologies in patients with voiding syndrome.

Keywords: acute cystitis, patient‐reported outcome (PRO), questionnaire, urinary tract infection (UTI), women

1. INTRODUCTION

Urinary tract infections (UTI) are one of the most common infections among women and are a leading cause of care‐seeking in the facilities of primary medical care and urology. 1 UTI diagnosis is based on lower urinary tract symptoms, including dysuria, frequency, and urgency with the absence of vaginal discharge. 2 According to the clinical practice guidelines on the management of urological infections, such as the European Association of Urology (EAU) or the American Urological Association, a reliable diagnosis of UTI can be made based on the medical history and the presence of typical lower urinary tract symptoms. 2 , 3 The urine culture is now only recommended in cases with atypical symptoms, in pregnant women, or those who do not respond to empirical antimicrobial treatment. 4 , 5 Treatment should be prescribed according to symptoms reported by the patients. However, the symptoms typical of UTI may also be present in other noninfectious urological disorders such as the overactive bladder, urinary stones, or painful bladder syndrome. 6 , 7 Therefore, in addition to assessing the presence of typical symptoms, their severity must be considered.

The Acute Cystitis Symptoms Score (ACSS) was developed to assess the symptoms and the effect on the quality of life in women with uncomplicated acute cystitis (AC). It was initially developed in Uzbek and Russian languages, then translated further to other languages to be used in several studies; it has proven its high diagnostic values. 8 , 9 , 10 The ACSS assesses the severity of symptoms and their impact on QoL, making it possible to differentiate AC from other urogenital disorders that usually present with similar symptoms, in addition to allowing the response to treatment to be monitored. 9 , 10 , 11

We aimed to validate the ACSS, a self‐reporting questionnaire to assess symptoms of UTI–AC and differential diagnosis in the Spanish language for its clinical use in daily practice and clinical and epidemiological studies.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design

The current study was designed as a prospective, observational cohort study in women with symptoms and a laboratory result consistent with AC. The study included data from Spain, Colombia, and Peru. The patients were treated and controlled according to the EAU clinical guidelines. 2 The control group included women with no suspicion of UTI who were evaluated at the clinic for another reason or who came as companions for other patients. Translated and linguistically validated version of the ACSS was taken as a tool for the symptomatic evaluation of study respondents.

2.2. ACSS as a study tool

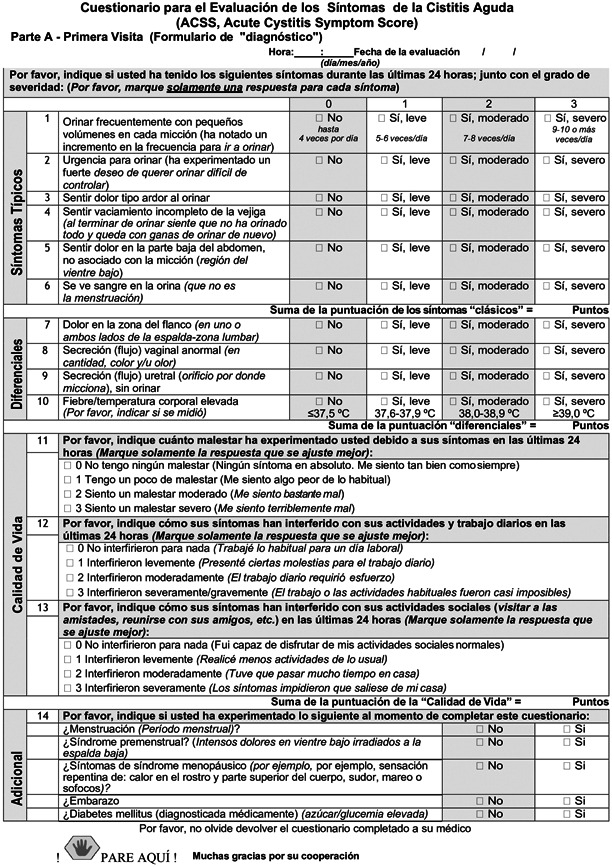

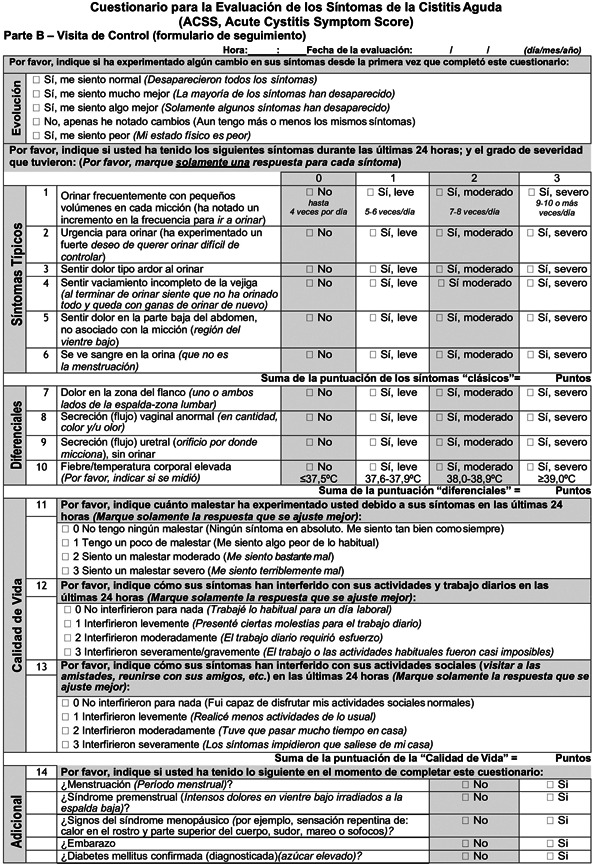

The ACSS is a patient self‐reporting questionnaire consisting of two parts: diagnostic Part A and follow‐up Part B. Each part contains 18 items, allocated to four domains: six items on typical symptoms of AC (“Typical” domain), four items for differential diagnosis (“Differential” domain), three items on quality of life (“QoL” domain), and five items on additional conditions that may affect therapy (“Additional” domain”).

Each item of the first three domains (“Typical”, “Differential” and “QoL”) is fitted with a 4‐point Likert‐type scale for assessing the severity of each symptom ranging from 0 (no symptom or discomfort) to 3 (severe symptom or discomfort). The “Additional” domain contains dichotomous “yes/no” questions. Furthermore, Part B includes an additional “Dynamics” domain formed by a question about the general evolution and changes in symptoms (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Spanish version of Acute Cystitis Symptoms Score

The translations of the ACSS into Spanish were carried out from the original Russian and the validated US American English versions of the ACSS questionnaire. The linguistic and clinical validation of the Spanish ACSS included four phases:

Phase 1: ACCS questionnaire was translated from original Russian and American English to Spanish by translators with Spanish as their mother language.

Phase 2: The four urologists from Spain and Latin America reviewed the English and Spanish translations and established a consensus form. This consensus form then was translated back to Russian by a translator with the mother language Russian and to US American English by a translator with the mother language American English, to check and exclude any relevant change in the meaning. This consensus version was then used, for all countries with Spanish as a primary language, for the cognitive assessment process.

Phase 3: Twenty females with a mean age of 37 (15) years old [mean (standard deviation)] and different educational levels and 20 healthcare professionals evaluated the ACSS questionnaire cognitively. After minor updates in the text and design based on their comments, the linguistically validated Spanish ACSS version was established. In addition, the ACSS Spanish version was then adapted after interviewing Spanish native speakers from both Spain and Central and South America. The final version of the ACSS in Spanish used in this study is presented in Figure 1 (including ACSS Spanish Part A/Part B).

Phase 4: Clinical evaluation performed by women with an episode of AC (patients) and female subjects without symptoms with suspicion of UTI (controls) from Spain, Colombia, and Peru.

2.3. Study population

Female respondents older than 18 years of age whose native language was Spanish and with a clinical and microbiological diagnosis of AC were invited to participate in the study from January 2020 to December 2021. Women with suspected acute pyelonephritis or severe sepsis, those who had received antibiotic treatment in the 2 weeks before the study, or who received treatment with medications (such as nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs) that could affect the severity of the symptoms were excluded from the selection of patients. We also excluded respondents who recently underwent invasive manipulation of the urinary tract, who had chronic diseases such as mental disorders and disability to read, understand and answer the questions properly, and those women who declined to participate in the study. The control group included women with no suspicion of UTI who were admitted to the clinic for another reason or who came as companions for other patients.

Both patients with AC and controls, at the initial visit, were given Part A of the ACSS questionnaire on paper and were asked to complete it themselves. In turn, they were provided with a Report‐Case Report Form (CRF) to record their demographic data, the reason for the medical visit, if they learned Spanish as their first language‐mother tongue, their educational level, and if they had previously suffered from symptoms of uncomplicated urinary tract infection. In the case of patients with AC, they were asked to complete part B of the ACSS questionnaire at the control visit (Test of cure), which was performed 3–15 days after the first visit. The evaluated patients were identified by a number. The study findings were stored in a computerized manner following the data protection law of the area. The physicians kept a list of personal identification of the patients (assigned numbers and names of the corresponding patients) to allow the identification of the records. Only the center researcher had access to this list and the data collected from each participant in the study's CRF was identified with a code, in such a way that the information collected was dissociated. The researcher stored the patient's data and password‐protected it to prevent third‐party access. The data from the questionnaires were recorded in electronic format using a specially designed software, e‐USQOLAT.

2.3.1. Clinical and microbiological considerations

Following the EAU guidelines on urological infections, the diagnosis of AC was made by the treating physician based on the clinical history and the typical clinical symptoms of patients referred to the clinic. All patients with a clinical diagnosis of AC underwent urinalysis and urine culture, obtaining a urine sample collected in the middle of urination. UTI–AC is defined microbiologically, according to the recommendations of the Infectious Disease Society of America, by the presence of ≥105 CFU (colony‐forming units)/ml of a bacterial species isolated in a urine culture. 12 , 13 In patients with the typical symptoms of UTI, a cut‐off point of ≥103 CFU/ml was also accepted. 2 , 14 Women clinically diagnosed with AC based on symptoms and with a positive urine leukocyte esterase test but without significant bacteriuria of ≥103 CFU/ml in urine culture were not excluded from the study, as there is evidence that AC can occur with a low bacterial count. 15 The results of urine analysis were usually evaluated in the midstream as the number of cells in a chamber's cell (high power field [HPF]). Dipstick urinalysis is convenient, but false‐positive and false‐negative results can occur. According to publications, the normal reference value for women is 0–5 white blood cells/HPF. However, it can vary depending on regulatory issues, equipment, local guidelines, clinical protocols. 16 , 17 , 18

2.4. Data analysis

A minimum sample size of 100 women was calculated. Two study groups were established with a 2:1 ratio of patients (individuals with AC) and controls (individuals without AC). The descriptive and comparative analyses of the responses to the ACSS items were performed for both groups. Psychometric characteristics of the ACSS were tested using coefficients of Cronbach's α and split‐half reliability. The diagnostic characteristics were tested using specificity, sensitivity, diagnostic odds ratio, positive and negative likelihood ratio, area under the receiver‐operating characteristic curve (AUC) diagnostic accuracy, and risk ratio. Average point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to present the results of the tests. The analysis was also carried out with a predefined cut‐off point of ≥6 by the summary score of the “Typical” domain. The normality of distributions was tested visually, using histograms and Q–Q plots and mathematically using Shapiro–Wilk's test. None of the variables of the ACSS have a normal distribution (see figures in Supporting Information).

To present the results, we used frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. The averages of the numerical values and their dispersion are presented according to their type: means and standard deviations or 95% CIs for the continuous variables and as median and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for the categorical variables.

Comparative analysis was performed using Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney's test for the categorical variables and using two‐sided Student's t‐test with the Welch correction in cases of inequality of variances for the continuous variables. Statistical significance was set at a p value of 0.05. Statistical analysis was carried out using the IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 23.0 (IBM Co.).

2.4.1. Ethical approval

This noninterventional study was carried out according to the rules of good clinical practice (GCP) defined by the International Council for Harmonization and following local regulations and standards of operational processes for clinical investigations and documentation management. The study was also conducted in compliance with Spanish regulations: Biomedical Research Law of July 3, 2007. The study will also follow the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and the rules of GCP (ICH/135/95). The Ethics Committee of our center approved the study Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre in Madrid, Spain (no. of approval letter 19/026 on February 26, 2019), which endorsed its performance in the rest of the centers. All patients had signed the consent.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study population

The ACSS was evaluated in 187 women, of whom 132 were diagnosed with AC and 55 formed the control group. The study was performed on 132 patients [age (mean;SD) (45.0;17.8)] and 55 controls (44.5;12.2). The homogeneity of demographic characteristics, additional conditions such as menstruation, premenstrual syndrome, pregnancy, menopause, diabetes mellitus, and risk factors for infection according to the ORENUC (European Association of Urology's classification system for UTIs) classification were summarized in Table 1. There is a higher percentage of control high college or postgraduate education (71.4%) compared to cases (53.1%). The homogeneity and differences between demographics and comorbidities for patients from America and Spain are shown in Table 2. The final Spanish version of the ACSS used for the clinical validation is given in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and comorbidities for patients and controls

| Parameter | Total cohort | Patients | Controls | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number, n (%) | 187 (100.0) | 132 (70.6%) | 55 (29.4) | n.a. |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 44.92 (16.58) | 45.07 (17.84) | 44.56 (12.21) | 0.850 |

| Sexually active, n (%) | 141 (78.3) | 99 (78.0) | 42 (79.2) | 0.848 |

| Level of education | 0.027 | |||

| Grade school, n (%) | 18 (10.3) | 18 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| High school, n (%) | 55 (31.4) | 41 (32.5) | 14 (28.6) | |

| College, n (%) | 85 (48.6) | 56 (44.4) | 29 (59.2) | |

| Postgraduate, n (%) | 17 (9.7) | 11 (8.7) | 6 (12.2) | |

| Number of missed patients | 12 | 6 | 6 | |

| Cases with or without risk factors for UTI according to the ORENUC system | 0.039 | |||

| Cases with no known risk factors for UTI (O), n (%) | 95 (56.9) | 62 (55.1) | 33 (68.8) | |

| Risk of recurrent UTIs but without risk of a more severe outcome (R), n (%) | 37 (22.2) | 33 (27.7) | 4 (8.3) | |

| Extraurogenital risk factors (E), n (%) | 31 (18.6) | 22 (18.5) | 9 (18.8) | |

| Relevant nephropathic diseases (N), n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Urologic resolvable risk factors (U), n (%) | 4 (2.4) | 2 (1.7) | 2 (4.2) | |

| Permanent external urinary catheter and unresolved urologic risk factors (C), n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Number of missed patients | 20 | 13 | 7 | |

| Additional characteristics following Cai's nomogram | ||||

| Number of sexual partners within the last year | 0.362 | |||

| No sexual partner, n (%) | 33 (19.1) | 26 (21.5) | 7 (13.5) | |

| One sexual partner, n (%) | 117 (67.6) | 77 (63.6) | 40 (76.9) | |

| Two sexual partners, n (%) | 16 (9.2) | 12 (9.9) | 4 (7.7) | |

| More than two sexual partners, n (%) | 7 (4.0) | 6 (5.0) | 1 (1.9) | |

| Number of missed patients | 14 | 11 | 3 | |

| Bowel function | 0.488 | |||

| Normal bowel function, n (%) | 74 (71.8) | 54 (69.2) | 20 (80.0) | |

| Predisposed to constipation, n (%) | 27 (26.2) | 22 (28.2) | 5 (20.0) | |

| Predisposed to diarrhea, n (%) | 2 (1.9) | 2 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Number of missed patients | 84 | 54 | 30 | |

| Hormonal status at the time of visit | 0.487 | |||

| Premenopausal, n (%) | 64 (62.1) | 47 (60.3) | 17 (68.0) | |

| Postmenopausal, n (%) | 103 (37.9) | 31 (39.7) | 8 (32.0) | |

| Number of missed patients | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Additional characteristics following ACSS's “Additional” domain | ||||

| Cases with menstruations at baseline, n (%) | 14 (7.5) | 12 (9.1) | 2 (3.6) | 0.213 |

| Cases with premenstrual symptoms, n (%) | 31 (16.6) | 20 (15.1) | 11 (20.0) | 0.172 |

| Cases with symptoms of menopause, n (%) | 39 (37.9) | 31 (39.7) | 8 (32.0) | 0.487 |

| Cases with pregnancy, n (%) | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.8) | 0.189 |

| Cases with diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 12 (6.4) | 9 (6.9) | 3 (5.4) | 0.192 |

Abbreviations: ACSS, Acute Cystitis Symptom Score; LATAM, Latin America; n.a., not available; ORENUC, European Association of Urology's classification system for UTIs; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Table 2.

Demographics and comorbidities for patients from LATAM and Spain

| Parameter | Total patients | LATAM patients | Spain patients | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number, n (%) | 132 | 50 (37.9) | 82 (62.1) | n.a. |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 45.07 (17.84) | 47.44 (17.01) | 43.62 (18.28) | 0.235 |

| Sexually active, n (%) | 99 (78.0) | 38 (77.6) | 61 (78.2) | 0.931 |

| Level of education | 0.018 | |||

| Grade school, n (%) | 18 (14.3) | 6 (12.2) | 12 (15.6) | |

| High school, n (%) | 41 (32.5) | 9 (18.4) | 32 (41.6) | |

| College, n (%) | 56 (44.4) | 27 (55.1) | 29 (37,7) | |

| Postgraduate, n (%) | 11 (8.7) | 7 (14.35) | 4 (5.2) | |

| Number of missed patients | 6 | 1 | 5 | |

| Cases with or without risk factors for UTI according to the ORENUC system | <0.001 | |||

| Cases with no known risk factors for UTI (O), n (%) | 62 (55.1) | 13 (29.5) | 49 (65.3) | |

| Risk of recurrent UTIs but without risk of a more severe outcome (R), n (%) | 33 (27.7) | 11 (25.0) | 22 (29.3) | |

| Extraurogenital risk factors (E), n (%) | 22 (18.5) | 20 (45.5) | 2 (2.7) | |

| Relevant nephropathic diseases (N), n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Urologic resolvable risk factors (U), n (%) | 2 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.7) | |

| Permanent external urinary catheter and unresolved urologic risk factors (C), n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Number of missed patients | 13 | 6 | 7 | |

| Additional characteristics following Cai's nomogram | ||||

| Number of sexual partners within the last year | 0.008 | |||

| No sexual partner, n (%) | 26 (21.5) | 10 (23.3) | 16 (20.5) | |

| One sexual partner, n (%) | 77 (63.6) | 33 (76.7) | 44 (56.4) | |

| Two sexual partners, n (%) | 12 (9.9) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (15.4) | |

| More than two sexual partners, n (%) | 6 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (7.7) | |

| Number of missed patients | 11 | 7 | 4 | |

| Additional characteristics following ACSS's “Additional” domain | ||||

| Cases with menstruations at baseline, n (%) | 12 (9.1) | 5 (10.0) | 7 (8.5) | |

| Cases with premenstrual symptoms, n (%) | 20 (15.1) | 6 (12.0) | 14 (16.8) | |

| Cases with symptoms of menopause, n (%) | 35 (26.5) | 5 (10.0) | 30 (36.6) | |

| Cases with pregnancy, n (%) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Cases with diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 9 (6.9) | 8 (16.0) | 1 (1.2) |

Abbreviations: ACSS, Acute Cystitis Symptom Score; LATAM, Latin America; ORENUC, European Association of Urology's classification system for UTIs; n.a., not available; UTI, urinary tract infection.

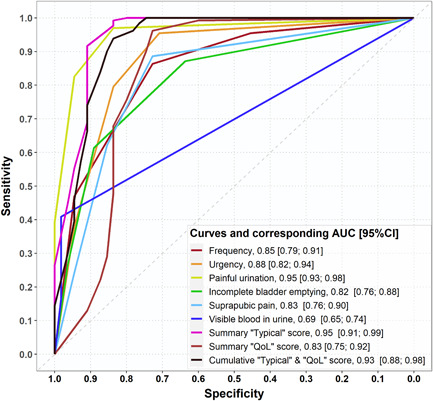

Cronbach's α of the ACSS was 0.86 and the split‐half reliability was 0.82. Using a sum score of ≥6 for typical symptoms, a specificity of 83.6%, and a sensitivity of 99.2% for the Spanish version of the ACSS. AUC was 0.91 [0.85; 0.97] [95% CI]. (Curves and corresponding AUC for variables included in ACSS were shown in Figure 2.)

Figure 2.

Curves and corresponding area under the receiver‐operating characteristic curve for variables including in ACSS. ACSS, Acute Cystitis Symptom Score; AUC, area under the receiver‐operating characteristic curve; CI, confidence interval.

Table 3a and 3b show the summary of scores of the patients and controls for each item of the domains “Typical,” “Differential,” and “QoL” of the ACSS questionnaire at baseline visit. The median punctuation in “Typical” score was 11.0 (9.0–13.0) [median (IQR)] in patients and 2.0 (0.0–6.5) in controls (p < 0.001). However, there was not a significant difference between patients and controls at baseline visit regarding the summary score of differential symptoms 1.0 (0.0–2.0) and 0.0 (0.0–1.5) (p = 0.381): The total score of ACSS for patients and controls was 16.0 (13.0–19.0) and 2.0 (0.0–6.5) (p < 0.001), respectively. The results for each symptom are reported in Table 4. When the results were stratified according to patients from Spain and Latin America, no differences were found in the typical, differential, and QoL symptoms. If the symptoms are analyzed individually, higher scores were found for frequency, hematuria in Spain, and incomplete bladder empty in Latin America (LATAM). Higher values in the impact of ITU–AC are reported in patients from LATAM (Table 5).

Table 3a.

Summary scores of ACSS questionnaire for each item of the domains “Typical Symptoms,” “Differential,” and “QoL” for cases and controls at baseline visit [median (IQR)]

| Parameter | Controls | Total patients | p Value | Patients (LATAM) | Patients (Spain) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summary scores of the domains of the ACSS | ||||||

| Summary “Typical” score at baseline visit, median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 11.0 (9.0–13.0) | <0.001 | 11.0 (9.0–12.0) | 11.0 (9.0–13.0) | 0.470 |

| Summary “Differential” score at baseline visit, median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0–1.5) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 0.0381 | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 0.417 |

| Summary “QoL” score at baseline visit, median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0–2.5) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | <0.001 | 6.0 (5.0–8.25) | 5.0 (3.0–6.0) | <0.001 |

| Summary score of the entire ACSS, median (IQR) | 2.0 (0.0–6.5) | 16.0 (13.0–19.0) | <0.001 | 19.0 (15.0–22.25) | 17.0 (14.0–20.0) | 0.092 |

Abbreviations: ACSS, Acute Cystitis Symptoms Score; IQR, interquartile range; LATAM, Latin America; QoL, quality of life.

Table 3b.

Scores of ACSS questionnaire for each item of the domains “Typical Symptoms,” “Differential,” and “QoL” for cases and controls at baseline visit [median (IQR)]

| Parameter | Controls | Total patients | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Summary scores of the domains of the ACSS | |||

| Frequency | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | <0.001 |

| Urgency | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | <0.001 |

| Painful micturition | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | <0.001 |

| Incomplete bladder emptying | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | <0.001 |

| Suprapubic pain | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | <0.001 |

| Visible hematuria | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–2.0) | <0.001 |

| Flank pain | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.5 (0.0–1.0) | 0.201 |

| Abnormal vaginal discharge | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.161 |

| Urethral discharge | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.263 |

| Fever | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.011 |

| General discomfort | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 2.0 (1.0–2.5) | <0.001 |

| Impact on daily activities/work | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | <0.001 |

| Impact on social activities | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | <0.001 |

| Summary “Typical” score at baseline visit | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 11.0 (9.0–13.0) | <0.001 |

| Summary “Differential” score at baseline visit | 0.0 (0.0–1.5) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 0.381 |

| Summary “QoL” score at baseline visit | 0.0 (0.0–2.5) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | <0.001 |

| Summary score of the entire ACSS | 2.0 (0.0–6.5) | 16.0 (13.0–19.0) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: ACSS, Acute Cystitis Symptoms Score; IQR, interquartile range; QoL, quality of life.

Table 4.

ACSS questionnaire scores for each item of the domains “Typical Symptoms,” “Differential,” and “QoL” for cases and controls

| Severity (Likert scale) | Controls, N (%) | Patients, N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | ||

| 0 (no) | 25 (45.5) | 6 (4.5) |

| 1 (mild) | 15 (27.3) | 12 (9.1) |

| 2 (moderate) | 12 (21.8) | 52 (39.4) |

| 3 (severe) | 3 (5.5) | 62 (47.0) |

| Urgency | ||

| 0 (no) | 39 (70.9) | 6 (4.5) |

| 1 (mild) | 7 (12.0) | 21 (15.9) |

| 2 (moderate) | 6 (10.9) | 55 (41.7) |

| 3 (severe) | 3 (5.5) | 50 (37.9) |

| Painful micturition | ||

| 0 (no) | 46 (83.6) | 4 (3.0) |

| 1 (mild) | 6 (10.9) | 19 (14.4) |

| 2 (moderate) | 3 (5.5) | 57 (43.2) |

| 3 (severe) | 0 (0.0) | 52 (39.4) |

| Incomplete bladder emptying | ||

| 0 (no) | 35 (63.6) | 17 (12.9) |

| 1 (mild) | 14 (25.5) | 34 (25.8) |

| 2 (moderate) | 4 (7.3) | 46 (34.8) |

| 3 (severe) | 2 (3.6) | 35 (26.5) |

| Suprapubic pain | ||

| 0 (no) | 44 (72.7) | 15 (11.4) |

| 1 (mild) | 7 (12.7) | 35 (26.5) |

| 2 (moderate) | 5 (9.1) | 50 (37.9) |

| 3 (severe) | 3 (5.5) | 32 (24.3) |

| Visible hematuria | ||

| 0 (no) | 54 (98.2) | 78 (59.1) |

| 1 (mild) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (12.1) |

| 2 (moderate) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (12.1) |

| 3 (severe) | 1 (1.8) | 22 (16.7) |

| Flank pain | ||

| 0 (no) | 32 (58.2) | 66 (50.0) |

| 1 (mild) | 14 (25.5) | 34 (25.8) |

| 2 (moderate) | 7 (12.7) | 19 (14.4) |

| 3 (severe) | 2 (3.6) | 13 (9.8) |

| Abnormal vaginal discharge | ||

| 0 (no) | 45 (81.8) | 96 (72.7) |

| 1 (mild) | 7 (12.7) | 21 (15.9) |

| 2 (moderate) | 3 (5.5) | 11 (8.3) |

| 3 (severe) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.0) |

| Urethral discharge | ||

| 0 (no) | 52 (94.5) | 118 (89.4) |

| 1 (mild) | 2 (3.6) | 9 (6.8) |

| 2 (moderate) | 1 (1.8) | 3 (2.3) |

| 3 (severe) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.5) |

| Fever | ||

| 0 (no) | 54 (98.2) | 113 (85.6) |

| 1 (mild) | 1 (1.8) | 13 (9.8) |

| 2 (moderate) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (3.8) |

| 3 (severe) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) |

| General discomfort | ||

| 0 (no) | 35 (63.6) | 1 (0.8) |

| 1 (mild) | 11 (20.0) | 35 (26.7) |

| 2 (moderate) | 3 (5.5) | 62 (47.3) |

| 3 (severe) | 6 (10.9) | 33 (25.2) |

| Impact on daily activities/work | ||

| 0 (no) | 38 (69.1) | 7 (5.3) |

| 1 (mild) | 6 (10.9) | 42 (32.1) |

| 2 (moderate) | 4 (7.3) | 56 (42,7) |

| 3 (severe) | 7 (12.7) | 26 (19.8) |

| Impact on social activities | ||

| 0 (no) | 42 (76.4) | 13 (9.9) |

| 1 (mild) | 2 (5.5) | 46 (35.1) |

| 2 (moderate) | 3 (5.5) | 43 (32.8) |

| 3 (severe) | 7 (12.7) | 29 (22.1) |

Abbreviations: ACSS, Acute Cystitis Symptoms Score; QoL, quality of life.

Table 5.

ACSS questionnaire scores for each item of the domains “Typical Symptoms,” “Differential,” and “QoL” for cases with AC at the first visit (diagnostics), and differences between patients from Spain and Latin America

| Severity (Likert scale) | Patients Spain, N (%) | Patients LATAM, N (%) | Total patients, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | |||

| 0 (no) | 2 (2.4) | 4 (8.0) | 6 (4.5) |

| 1 (mild) | 1 (1.2) | 11 (22.0) | 12 (9.1) |

| 2 (moderate) | 36 (43.9) | 16 (32.0) | 52 (39.4) |

| 3 (severe) | 43 (52.4) | 19 (38.0) | 62 (47.0) |

| Urgency | |||

| 0 (no) | 1 (1.2) | 5 (10.0) | 6 (4.5) |

| 1 (mild) | 15 (18.3) | 6 (12.0) | 21 (15.9) |

| 2 (moderate) | 37 (45.1) | 18 (36.0) | 55 (41.7) |

| 3 (severe) | 29 (35.4) | 21 (42.0) | 50 (37.9) |

| Painful micturition | |||

| 0 (no) | 3 (3.7) | 1 (2.0) | 4 (3.0) |

| 1 (mild) | 12 (14.6) | 7 (14.0) | 19 (14.4) |

| 2 (moderate) | 36 (43.9) | 21 (42.0) | 57 (43.2) |

| 3 (severe) | 31 (37.8) | 21 (42.0) | 52 (39.4) |

| Incomplete bladder emptying | |||

| 0 (no) | 11 (13.4) | 6 (12.0) | 17 (12.9) |

| 1 (mild) | 27 (32.9) | 7 (14.0) | 34 (25.8) |

| 2 (moderate) | 28 (34.1) | 18 (36.0) | 46 (34.8) |

| 3 (severe) | 16 (19.5) | 19 (38.0) | 35 (26.5) |

| Suprapubic pain | |||

| 0 (no) | 5 (6.1) | 10 (20.0) | 15 (11.4) |

| 1 (mild) | 21 (25.6) | 14 (28.0) | 35 (26.5) |

| 2 (moderate) | 33 (40.2) | 17 (34.0) | 50 (37.9) |

| 3 (severe) | 23 (28.0) | 9 (18.0) | 32 (24.3) |

| Visible hematuria | |||

| 0 (no) | 52 (63.4) | 26 (52.0) | 78 (59.1) |

| 1 (mild) | 6 (7.3) | 10 (20.0) | 16 (12.1) |

| 2 (moderate) | 7 (8.5) | 9 (18.0) | 16 (12.1) |

| 3 (severe) | 17 (20.7) | 5 (10.0) | 22 (16.7) |

| Flank pain | |||

| 0 (no) | 43 (52.4) | 23 (46.0) | 66 (50.0) |

| 1 (mild) | 25 (30.5) | 9 (18.0) | 34 (25.8) |

| 2 (moderate) | 8 (9.8) | 11 (22.0) | 19 (14.4) |

| 3 (severe) | 6 (7.3) | 7 (14.0) | 13 (9.8) |

| Abnormal vaginal discharge | |||

| 0 (no) | 61 (74.4) | 35 (70.0) | 96 (72.7) |

| 1 (mild) | 11 (13.4) | 10 (20.0) | 21 (15.9) |

| 2 (moderate) | 6 (7.3) | 5 (10.0) | 11 (8.3) |

| 3 (severe) | 4 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.0) |

| Urethral discharge | |||

| 0 (no) | 72 (87.8) | 46 (92.0) | 118 (89.4) |

| 1 (mild) | 5 (6.1) | 4 (8.0) | 9 (6.8) |

| 2 (moderate) | 3 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.3) |

| 3 (severe) | 2 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.5) |

| Fever | |||

| 0 (no) | 84 (85.4) | 43 (86.0) | 113 (85.6) |

| 1 (mild) | 8 (9.8) | 5 (10.0) | 13 (9.8) |

| 2 (moderate) | 3 (3.7) | 2 (4.0) | 5 (3.8) |

| 3 (severe) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) |

| General discomfort | |||

| 0 (no) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (0.8) |

| 1 (mild) | 27 (33.3) | 8 (16.0) | 35 (26.7) |

| 2 (moderate) | 42 (51.9) | 20 (40.0) | 62 (47.3) |

| 3 (severe) | 12 (14.8) | 21 (42.0) | 33 (25.2) |

| Impact on daily activities/work | |||

| 0 (no) | 5 (6.2) | 2 (4.0) | 7 (5.3) |

| 1 (mild) | 33 (40.7) | 9 (18.0) | 42 (32.1) |

| 2 (moderate) | 36 (44.4) | 20 (40.0) | 56 (42,7) |

| 3 (severe) | 7 (8.6) | 19 (38.0) | 26 (19.8) |

| Impact on social activities | |||

| 0 (no) | 10 (12.3) | 3 (6.0) | 13 (9.9) |

| 1 (mild) | 32 (39.5) | 14 (28.0) | 46 (35.1) |

| 2 (moderate) | 29 (35.8) | 14 (28.0) | 43 (32.8) |

| 3 (severe) | 10 (12.3) | 19 (38.0) | 29 (22.1) |

Abbreviations: ACSS, Acute Cystitis Symptoms Score; QoL, quality of life; LATAM, Latin America.

ACSS values change from the test performed during the AC and the posttreatment evaluation. The median score of the “Typical” domain decreased significantly when comparing the pre‐ and posttreatment scores (11.0 and 1.0, respectively). The mean score for the “QoL” domain also showed a significant improvement between the initial visit (5.0) and the follow‐up visit (0.0) (Tables 6 and 7).

Table 6.

Summary scores of ACSS questionnaire for each item of the domains “Typical Symptoms,” “Differential,” and “QoL” for cases at the moment of UTI–AC and posttreatment [median (IQR)]

| Parameter | Acute cystitis | Posttreatment | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Summary scores of the domains of the ACSS | |||

| Summary “Typical” score at baseline visit, median (IQR) | 11.0 (9.0–13.0) | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | <0.001 |

| Summary “Differential” score at baseline visit, median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | <0.001 |

| Summary “QoL” score at baseline visit, median (IQR) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.5) | <0.001 |

| Summary score of the entire ACSS, median (IQR) | 16.0 (13.0–19.0) | 2.0 (0.0–5.25) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: ACSS, Acute Cystitis Symptoms Score; IQR, interquartile range; QoL, quality of life; UTI–AC, urinary tract infection–acute cystitis.

Table 7.

ACSS questionnaire scores for each item of the domains “Typical Symptoms,” “Differential,” and “QoL” for cases at the moment of UTI–AC and posttreatment

| Severity (Likert scale) | Acute cystitis, N (%) | Posttreatment, N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | ||

| 0 (no) | 6 (4.5) | 60 (44.5) |

| 1 (mild) | 12 (9.1) | 38 (34.5) |

| 2 (moderate) | 52 (39.4) | 11 (10.0) |

| 3 (severe) | 62 (47.0) | 1 (0.9) |

| Urgency | ||

| 0 (no) | 6 (4.5) | 74 (67.3) |

| 1 (mild) | 21 (15.9) | 26 (23.6) |

| 2 (moderate) | 55 (41.7) | 7 (6.4) |

| 3 (severe) | 50 (37.9) | 3 (2.7) |

| Painful micturition | ||

| 0 (no) | 4 (3.0) | 84 (76.4) |

| 1 (mild) | 19 (14.4) | 16 (16.4) |

| 2 (moderate) | 57 (43.2) | 6 (5.5) |

| 3 (severe) | 52 (39.4) | 2 (1.8) |

| Incomplete bladder emptying | ||

| 0 (no) | 17 (12.9) | 80 (72.7) |

| 1 (mild) | 34 (25.8) | 23 (20.9) |

| 2 (moderate) | 46 (34.8) | 4 (3.6) |

| 3 (severe) | 35 (26.5) | 3 (2.7) |

| Suprapubic pain | ||

| 0 (no) | 15 (11.4) | 82 (74.5) |

| 1 (mild) | 35 (26.5) | 25 (22.7) |

| 2 (moderate) | 50 (37.9) | 2 (1.8) |

| 3 (severe) | 32 (24.3) | 1 (0.9) |

| Visible hematuria | ||

| 0 (no) | 78 (59.1) | 105 (96.3) |

| 1 (mild) | 16 (12.1) | 4 (3.7) |

| 2 (moderate) | 16 (12.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| 3 (severe) | 22 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Flank pain | ||

| 0 (no) | 66 (50.0) | 93 (84.5) |

| 1 (mild) | 34 (25.8) | 14 (12.7) |

| 2 (moderate) | 19 (14.4) | 2 (1.8) |

| 3 (severe) | 13 (9.8) | 1 (0.9) |

| Abnormal vaginal discharge | ||

| 0 (no) | 96 (72.7) | 97 (88.2) |

| 1 (mild) | 21 (15.9) | 10 (9.1) |

| 2 (moderate) | 11 (8.3) | 2 (1.8) |

| 3 (severe) | 4 (3.0) | 1 (0.9) |

| Urethral discharge | ||

| 0 (no) | 118 (89.4) | 106 (96.4) |

| 1 (mild) | 9 (6.8) | 3 (2.7) |

| 2 (moderate) | 3 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| 3 (severe) | 2 (1.5) | 21 (0.8) |

| Fever | ||

| 0 (no) | 113 (85.6) | 109 (99.1) |

| 1 (mild) | 13 (9.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| 2 (moderate) | 5 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| 3 (severe) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.9) |

| General discomfort | ||

| 0 (no) | 1 (0.8) | 75 (68.8) |

| 1 (mild) | 35 (26.7) | 31 (28.4) |

| 2 (moderate) | 62 (47.3) | 3 (2.8) |

| 3 (severe) | 33 (25.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Impact on daily activities/work | ||

| 0 (no) | 7 (5.3) | 83 (76.1) |

| 1 (mild) | 42 (32.1) | 20 (18.33) |

| 2 (moderate) | 56 (42,7) | 6 (5.5) |

| 3 (severe) | 26 (19.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Impact on social activities | ||

| 0 (no) | 13 (9.9) | 85 (78.0) |

| 1 (mild) | 46 (35.1) | 17 (15.6) |

| 2 (moderate) | 43 (32.8) | 7 (6.4) |

| 3 (severe) | 29 (22.1) | 0 (0.0) |

Abbreviations: ACSS, Acute Cystitis Symptoms Score; QoL, quality of life; UTI–AC, urinary tract infection–acute cystitis.

3.2. Results of the laboratory investigations

A total of 111 positive urine cultures were obtained in patients with AC. Escherichia coli was the most common among the isolated pathogens, presenting in 93 urine cultures (83.8%), followed by Proteus spp. in 8 (7.2%) and Klebsiella pneumoniae in 6 cases (5.4%).

4. DISCUSSION

UTIs and AC episodes have a high prevalence in the population. Moreover, an antibiotic prescription must be made before microbiological results are available. 2 , 19 Therefore, an adequate clinical diagnosis and knowledge of microbiological patterns are of paramount importance. The traditional microbiological criteria for UTI diagnosis are defined by the presence of ≥105 CFU/ml. Many authors, however, describe the same symptoms in women with lower bacterial counts and even negative cultures. 14 , 20 , 21 Stamm et al. 14 showed that the criterion of ≥105 CFU/ml had high specificity (0.99) but very low sensitivity (0.51), which would mean that only 51% of women with UTIs could be correctly identified. In 22% of urine cultures performed in women with typical AC symptoms, no bacterial growth was obtained. As UTI must be diagnosed by clinical findings, it seems reasonable to affirm that the diagnosis of AC based on the presence of symptoms takes on greater importance than the result of urine culture. Therefore, routine urine cultures in women with typical symptoms of AC are not recommended as a routine tool. 2 , 22 In this context, Alidjanov et al. developed and validated the ACSS questionnaire for the diagnosis of AC. 8 , 9 , 10 , 23 Two other questionnaires to evaluate UTIs were previously developed, the “UTI Symptoms Assessment” (UTISA) and the “Activity Impairment Assessment” (AIA). The UTISA questionnaire assesses the severity of symptoms in low UTI, while the AIA questionnaire measures the deterioration of activity experienced in women with AC. 24 , 25 However, the aim of the UTISA and AIA questionnaires was not to develop the tool for the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of AC. Therefore, statistical data such as sensitivity, specificity, and discriminative ability was not described in detail. The ACSS has been developed and validated taking these parameters into account. In addition to assessing the severity of symptoms, it includes questions to differentiate AC from other pathologies that may present with similar symptoms (“Differential” domain), for conditions that may affect therapy (“Additional” domain), and to assess the treatment efficacy (“Dynamics” domain of the follow‐up Part B). These distinctive characteristics are its main advantages over other questionnaires, allowing it to add greater precision and utility for epidemiological studies. 8 , 9 , 10 In the original Uzbek and Russian versions of the ACSS, Alidjanov et al. 8 , 10 found that a total score of 6 in the domain “Typical Symptoms” was the optimal cut‐off point to predict AC with a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 90%. The Italian ACSS version, for example, showed a sensitivity of 92.5% and a specificity of 97.8%, with a total score of ≥6 and higher for the domain “Typical Symptoms.” 26 This version in Spanish has proven to be useful for diagnosing AC in women, finding statistically significant differences between patients and controls for all the questions in the domains “Typical Symptoms,” “Differential,” and “QoL”, except for the differential items of “Flank pain” and “fever.” Moreover, we found very good results of internal consistency and in the comparison between visits for the “Differential” domain.

Symptom severity scoring is necessary, not only for diagnosis but also for assessing response to treatment and “clinical cure.” A recent study by Alidjanov et al. 27 concludes that the ACSS has the potential to be used as a measurement instrument in the outcome of treatment, evaluating the domains “Typical,” “QoL,” and “Dynamics” in a combined way. In our study, the mean score of the “Typical” domain decreased significantly when comparing the pre‐ and posttreatment scores (11.0 and 1.0, respectively). The mean score for the “QoL” domain also showed a significant improvement between the initial visit (5.0) and the follow‐up visit (0.0).

The study shows some limitations and strengths. One of the strengths is that the study was carried out in a multicenter manner, including patients from Spain (n = 82) and South America (n = 50). Although some differences between both groups of patients, these differences seem minor and, in our opinion, do not affect the validity of the ACSS evaluation. One limitation is that the selection of patients may not be representative of the general population of women with AC. It can limit the power to reflect the interpretability of the scale. However, it does not affect the external validity of the results obtained. To select a representative population, patients included were collected from a primary care and urology setting. Another limitation may be the subjective response when using a self‐administered questionnaire due to individual interpretation of the questions asked. To minimize this possible limitation, the ACSS was not only forward‐translated but also backward‐translated from English to Spanish; a cognitive assessment procedure included 20 women with Spanish as their mother language and of different ages and educational levels. Another limitation may be that there is a higher percentage of control high college or postgraduate education in comparison with cases. To avoid cognitive limitation, before evaluating to questionnaire in cases and control 20 females with different educational levels evaluated the ACSS questionnaire cognitively and it was the definitive version was established based on their comments. Furthermore, the ACSS questionnaire has been evaluated in several languages including women with different education levels. 11 , 26 , 27

Moreover, in addition to the accepted and applied routine translation process from either the source or another valid version of the medical questionnaire, our process included both the original AND valid master versions of the ACSS, resulting in backward‐cross‐translation.

A third limitation may be seen with the differential diagnosis of other entities with similar symptoms to those reported by patients with UTIs, such as overactive bladder, urinary stones, interstitial cystitis, or obstructive cystocele. To minimize this task, AC was confirmed with urinalysis and urine culture. In the current study, the cutoff value of ACSS by the summary score of the “Typical” domain ≥6 was not sufficient to make an exact distinction between the symptoms of AC and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) caused by other reasons in about 7%–17% of cases. However, this proportion was comparable to the reported results of routine and enhanced urinalyses. 28 , 29 , 30 The subanalysis of control with punctuation higher than the cutoff value showed that overactive bladder and other entities might offer similar punctuations as patients with AC. A measure to improve the accuracy of ACSS to distinguish AC from other conditions could be reached with the individualized analysis of each item, which could be complicated in the clinical routine and has, therefore, a prioritized research interest. For routine clinical practice, we can so far propose to use the ACSS in combination with urinalysis and medical history. Uncomplicated cystitis usually begins acutely within a few days, whereas LUTS caused by different reasons have a much longer history.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The validated Spanish version of the ACSS questionnaire is a reliable, valid, and easy‐to‐use questionnaire that can evaluate the symptoms and clinical outcomes of patients with AC. It can be used as a patient's self‐diagnosis of AC, as a PRO measure tool, and help to rule out other pathologies in patients with voiding syndrome.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting information.

Medina‐Polo J, Arrébola‐Pajares A, Corrales‐Riveros JG, et al. Validation of the Spanish Acute Cystitis Symptoms Score (ACSS) in native Spanish‐speaking women of Europe and Latin America. Neurourol Urodyn. 2023;42:263‐281. 10.1002/nau.25079

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data from the questionnaires were recorded in electronic format using a specially designed software, e‐USQOLAT. http://www.ACSS.world. The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alós JI. Epidemiology and etiology of urinary tract infections in the community. antimicrobial susceptibility of the main pathogens and clinical significance of resistance. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2005;23(suppl 4):3‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bonkat GC, Bartoleti R, Bruyère F, et al. EAU Guidelines on Urological Infections. EAU Guidelines Office; 2022. http://uroweb.org/guideline/urological-infections/ [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anger J, Lee U, Lenore Ackerman A. Recurrent Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections in Women: AUA/CUA/SUFU Guideline. American Urological Association (AUA); 2019. https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/recurrent-uti [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alidjanov JF, Naber KG, Abdufattaev UA, Pilatz A, Wagenlehner FM. Reliability of symptom‐based diagnosis of uncomplicated cystitis. Urol Int. 2019;102:83‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alidjanov JF, Naber KG, Pilatz A, et al. Evaluation of the draft guidelines proposed by EMA and FDA for the clinical diagnosis of acute uncomplicated cystitis in women. World J Urol. 2020;38:63‐72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Castro‐Diaz D, Cardozo L, Chapple CR, et al. Urgency and pain in patients with overactive bladder and bladder pain syndrome. What are the differences? Int J Clin Pract. 2014;68:356‐362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sun Y, Harlow BL. The association of vulvar pain and urological urgency and frequency: findings from a community‐based case‐control study. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:1871‐1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alidjanov JF, Abdufattaev UA, Makhsudov SA, et al. New self‐reporting questionnaire to assess urinary tract infections and differential diagnosis: acute cystitis symptom score. Urol Int. 2014;92:230‐236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alidjanov JF, Abdufattaev UA, Makhsudov SA, et al. The acute cystitis symptom score for patient‐reported outcome assessment. Urol Int. 2016;97:402‐409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alidjanov J, Naber K, Abdufattaev U, Pilatz A, Wagenlehner F. Reevaluation of the acute cystitis symptom score, a self‐reporting questionnaire. Part II. Patient‐reported Outcome Assessment. Antibiotics. 2018;7:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alidjanov JF, Naber KG, Pilatz A, Wagenlehner FM. Validation of the American English Acute Cystitis Symptom Score. Antibiotics. 2020;9:929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. European Medicines Agency. Guideline on the evaluation of medicinal products indicated for treatment of bacterial infections, EMA/844951/2018, Rev.3. European Medicines Agency; 2018:20. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/draft-guideline-evaluation-medicinal-products-indicated-treatment-bacterial-infections-revision-3_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13. US Food Drug Administration Center for Drugs Evaluation Research. Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections: Developing Drugs for Treatment. Guidance for Industry. US Food Drug Administration Center for Drugs Evaluation Research; 2019. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/uncomplicated-urinary-tract-infections-developing-drugs-treatment-guidance-industry [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stamm WE, Counts GW, Running KR, Fihn S, Turck M, Holmes KK. Diagnosis of coliform infection in acutely dysuric women. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:1393‐1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nicolle LE. Catheter associated urinary tract infections. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2014;3:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cai T, Lanzafame P, Caciagli P, et al. Role of increasing leukocyturia for detecting the transition from asymptomatic bacteriuria to symptomatic infection in women with recurrent urinary tract infections: a new tool for improving antibiotic stewardship. Int J Urol. 2018;25:800‐806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Memişoğulları R, Yüksel H, Yıldırım HA, Yavuz Ö. Performance characteristics of dipstick and microscopic urinalysis for diagnosis of urinary tract infection. Eur J Gen Med. 2010;7(2):174‐178. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Simerville JA, Maxted WC, Pahira JJ. Urinalysis: a comprehensive review. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:1153‐1162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Prieto L, Esteban M, Salinas J, et al. Consensus document of the Spanish Urological Association on the management of uncomplicated recurrent urinary tract infections. Actas Urol Esp. 2015;39(6):339‐348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hooton TM, Roberts PL, Cox ME, Stapleton AE. Voided midstream urine culture and acute cystitis in premenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1883‐1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heytens S, De Sutter A, De Backer D, Verschraegen G, Christiaens T. Cystitis: symptomatology in women with suspected uncomplicated urinary tract infection. J Women's Health. 2011;20(20):1117‐1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wagenlehner FME, Naber KG. Treatment of bacterial urinary tract infections: presence and future. Eur Urol. 2006;49:235‐244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alidjanov JF, Naber KG, Pilatz A, Wagenlehner FM, are copyright holders of the ACSS. http://www.ACSS.world

- 24. Clayson D, Wild D, Doll H, Keating K, Gondek K. Validation of a patient‐administered questionnaire to measure the severity and bothersomeness of lower urinary tract symptoms in uncomplicated urinary tract infection (UTI): the UTI Symptom Assessment questionnaire. BJU Int. 2005;96:350‐359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wild DJ, Clayson DJ, Keating K, Gondek K. Validation of a patient‐administered questionnaire to measure the activity impairment experienced by women with uncomplicated urinary tract infection: the Activity Impairment Assessment (AIA). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Di Vico T, Morganti R, Cai T, et al. Acute Cystitis Symptom Score (ACSS): clinical validation of the Italian version. Antibiotics. 2020;9(3):104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alidjanov JF, Naber KG, Pilatz A, et al. Additional assessment of Acute Cystitis Symptom Score questionnaire for patient‐reported outcome measure in female patients with acute uncomplicated cystitis: part II. World J Urol. 2020;38:1977‐1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shang YJ, Wang QQ, Zhang JR, et al. Systematic review and meta‐analysis of flow cytometry in urinary tract infection screening. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;424:90‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Berger RE. Urinary tract infection in the users of depot–medroxyprogesterone acetate. J Urol. 2005;174(3):941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Holm A, Cordoba G, Sørensen TM, et al. Clinical accuracy of point‐of‐care urine culture in general practice. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2017;35(2):170‐177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information.

Data Availability Statement

The data from the questionnaires were recorded in electronic format using a specially designed software, e‐USQOLAT. http://www.ACSS.world. The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.