Abstract

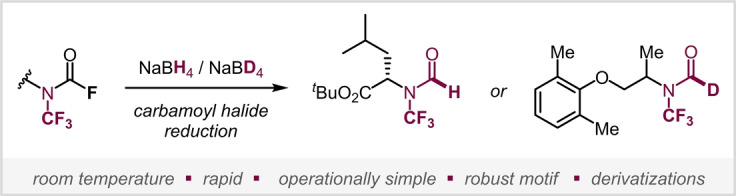

The departure into unknown chemical space is essential for the discovery of new properties and function. We herein report the first synthetic access to N‐trifluoromethylated formamides. The method involves the reduction of bench‐stable NCF3 carbamoyl fluorides and is characterized by operational simplicity and mildness, tolerating a broad range of functional groups as well as stereocenters. The newly made N−CF3 formamide motif proved to be highly robust and compatible with diverse chemical transformations, underscoring its potential as building block in complex functional molecules.

Keywords: Fluorine, N−CF3 Formamide, Reduction

The first synthetic access to N‐trifluoromethylated formamides is reported. The method involves the reduction of bench‐stable N−CF3 carbamoyl fluorides. In contrast to e.g. N−Me formamides, the newly made N−CF3 formamides do not show rotamers at room temperature. Moreover, they are highly robust and compatible with diverse chemical transformations.

The exploration of unknown chemical space is considered key to reach the next frontier of innovative materials, pharmaceuticals or agrochemicals. [1] To this end, the molecular editing of crucial functional groups to currently unknown structural motifs is expected to result in novel properties and function. [2] A widely pursued modification of organic molecules is the introduction of fluorine or fluorine‐containing groups, which allows to modulate the molecules’ physicochemical properties such as solubility, lipophilicity, basicity, electrophilicity and metabolic stability. [3] In this context, a functionality that could so far not be edited to a N‐trifluoromethylated analogue, is the formamide motif (i.e. R2N−COH).

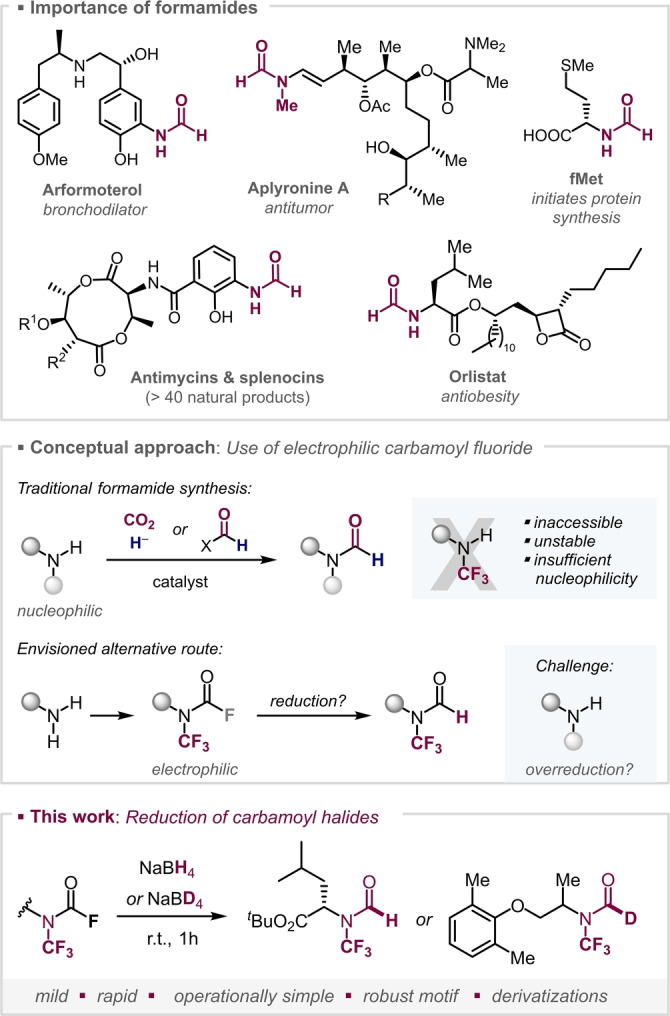

Aside from their uses as organocatalysts, [4] protecting groups [5] or as synthetic precursors (e.g. in heterocycle syntheses), [6] formamides are important motifs in various drugs and biologically active molecules (Figure 1, top). Representative examples are the drug Arformoterol, [7] used to fight asthma and COPD, Aplyronine A [8] as potent antitumor compound, the anti‐obesity drugs Lipstatin [9] and Orlistat, [10] as well as the natural product class of antimycins. The latter represent over 40 natural products, which all share the 3‐formamidosalicylate unit, and have biological functions running from antifungal to anticancer and anti‐inflammatory activity. [11] Systematic studies revealed that an increased conformational flexibility of the formyl unit can be associated with higher activity.[ 12 , 13 ] As such, a modification of the formyl unit that lowers the N‐lone pair availability and hence the rotational barrier could be greatly enabling. We envisioned that N‐trifluoromethylation could potentially achieve this feat. In addition, such a modification should also increase the overall metabolic stability [14] and lipophilicity. [15] Our computational study of the antimycin core (R1=COMe, R2=Me, see Supporting Information for details) suggested that trifluoromethylation of the N−H would lead to an increased acidity of the phenolic OH group of almost one pK a unit (from 9.9 to 9.0) and slight reduction in barrier to rotation of >1 kcal mol−1 (c.f. the N−H congener). This increased flexibility is more pronounced when compared to the N−Me analogue, with barriers lowered by over 5 kcal mol−1, [16] and mirrors our previous experimental NMR studies with amides. [17] However, despite the growing accessibility of N−CF3 compounds,[ 14 , 17 , 18 ] the corresponding N−CF3 formamides are not accessible with the existing synthetic repertoire and are hence unknown.

Figure 1.

Importance of formamides, synthesis and challenges.

Traditionally, methods for the synthesis of formamides use primary or secondary amines as the starting material, relying upon their inherent nucleophilicity to engage an electrophilic formyl unit. [19] However, the direct translation of this concept to N−CF3 variants will not likely be a general solution to this synthetic problem due to the lack of accessibility (and stability) of secondary N−CF3 amines[ 18i , 20 ] as well as their attenuated nucleophilicity (Figure 1, middle).

With a goal to develop a straightforward, efficient and general method to construct N−CF3 formamides, we turned our attention to N−CF3 carbamoyl fluorides, which are bench‐stable and easily accessible from primary amines, [17] and investigated the possibility of an F→H exchange. The substitution of fluoride by nucleophilic hydride would offer the most convenient approach. However, this process is so far unknown (also for carbamoyl halides not carrying a CF3), [21] which might be due to challenges relating to overreduction. Indeed, the reduction of formamides to the corresponding amine with NaBH4 is known. [22] This reactivity could be aggravated by the withdrawing effect of fluorine. Despite the lack of procedures to reduce carbamoyl halides in general, we nevertheless set out to study the reactivity of the corresponding N−CF3 carbamoyl fluorides with hydrides.

Using a solvent mixture of DCM/MeOH (1 : 1) with NaBH4 in our initial experiments indicated the formation of undesired N−CF3 methylcarbamate along with encouraging traces of the desired N−CF3 formamide. We suspected that at room temperature MeOH consumes NaBH4 [23] and forms alkoxyboron species which are known to perform transesterification. [24] To disfavour this undesired side‐process, we turned to the sterically more demanding (and less nucleophilic) tertiary alcohol t AmOH. Pleasingly, using a mixture of DCM/ t AmOH (1 : 1), reaction of a benzylic N−CF3 carbamoyl fluoride with NaBH4 gave the desired N−CF3 formamide 1 in 80 % yield in 1 h at room temperature as the exclusive product (see Scheme 1).

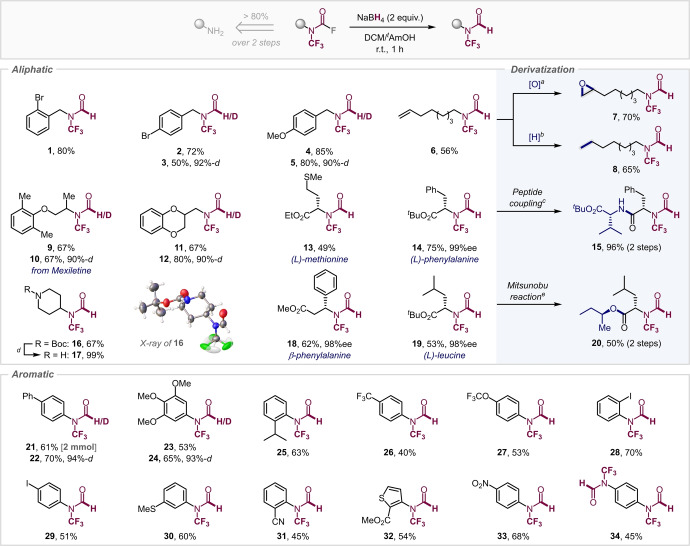

Scheme 1.

Scope of N−CF3 reduction. [25] Reaction conditions: N−CF3 carbamoyl fluoride (1 equiv), NaBH4 (2 equiv), DCM/ t AmOH (1 : 1) [0.2 M] at r.t. for 1–2 h. a) m‐CPBA (1 equiv), DCM, 0° C to r.t., 16 h; b) H2 (1 atm), Pd/C (10 mol %), MeOH, r.t., 24 h; c) step 1: TFA, DCM, r.t., 16 h; step 2: HBTU, DIPEA, H‐Val‐O t Bu⋅HCl, DCM, r.t., 16 h (yield over 2 steps); d) TFA (excess), CHCl3, r.t., 5 h; e) step 1: TFA, DCM, r.t., 16 h; step 2: PPh3 (1 equiv), DIAD (1 equiv), (R)‐butan‐2‐ol (1 equiv), THF, r.t., 16 h (yield over 2 steps).

With this encouraging result in hand, we subsequently explored the wider scope (Scheme 1). Pleasingly, our method proved to be applicable to a variety of aryl and alkyl substrates. Both, electron‐donating and electron‐withdrawing functional groups were tolerated under these conditions, including valuable halogens (1, 2, 28, 29), medicinally‐ and agrochemically‐relevant trifluoromethyl and trifluoromethoxy groups (26, 27), methoxy (23) as well as heterocycles (11, 32). Pleasingly, potentially reducible functionalities, such as ester (13, 14, 18, 19, 32), nitrile (31), nitro (33) or alkene (6) remained fully untouched.

We were able to extend the exchange to synthesize deutero isotopologues via introduction of deuteride (3, 5, 10, 12, 22, 24) in high efficiency, offering potentially increased metabolic stability as well as a tracer in metabolic studies. [26]

Moreover, our method unlocked access to the N−CF3 formamide derivatives of both α‐ and β‐amino acids (14, 18, 19), including the N−CF3 analogue of the important fMet (13), which has been linked to human immune response and late‐onset diseases. [27] Notably, our mild conditions allowed for full conservation of the stereochemical integrity of the employed amino acids.

With a view to exploring the chemical robustness of the newly accessed N−CF3 formamides, we examined their compatibility to downstream diversification. Pleasingly, the N−CF3 formamide motif proved to be highly robust, tolerating the diversification under high temperature, basic, acidic, oxidative, transition‐metal‐catalyzed or light‐activated photo‐redox conditions (see Scheme 1, right & Scheme 2, left). The pendant alkene in 6 (Scheme 1) could be oxidized (by m‐CPBA) to epoxide 7 as well as reduced by Pd/C under an H2 atmosphere to 8. Additionally, deprotection of the Boc‐group proceeded smoothly with 14, followed by peptide coupling to give 15. It is worth noting that formylated peptides are of importance in bacterial activation of nociceptors. [28] Pleasingly, the N−CF3 formyl leucine underwent successful alcohol substitution under Mitsunobu conditions to give 20, which resembles the final step of the synthesis of the anti‐obesity drug Orlistat (and further underscores the possibility to implement the novel N−CF3 motif in drug molecules). [29] Similarly, Pd‐catalyzed cross‐coupling methodology proved to be equally compatible: powerful Pd‐catalyzed Buchwald–Hartwig amidation [30] (35), Sonogashira alkynylation (36), borylation (37) and carbonylation [31] (38) were readily performed (see Scheme 2, left). Using PdI dimer catalysis [32] enabled C−Br selective cross‐coupling with excess organozincate to 39 without consumption of the N−CF3 formamide motif. Finally, we were also able to perform an etherification with diacetone galactose to form 40 under Ni/photoredox conditions. [33] Collectively, these transformations clearly demonstrate the exquisite robustness of the novel N−CF3 formamide motif as well as its potential as building block in functional molecules for medicinal, agrochemical or material sciences. [34]

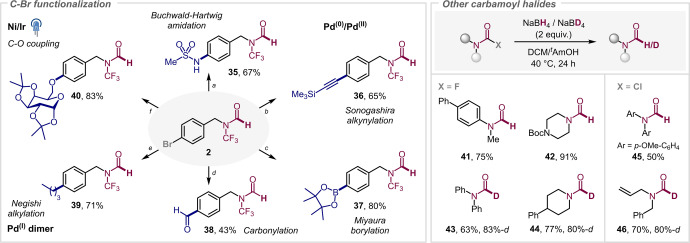

Scheme 2.

Functionalization of the products (left) and extension of the method (right). a) MeSO2NH2 (1.2 equiv), [Pd(allyl)Cl]2 (1 mol %), t BuXPhos (4 mol %), K2CO3 (2 equiv), 2‐Me‐THF, 80° C, 16 h; b) trimethylsilylacetylene (1.3 equiv), Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 (5 mol %), PPh3 (10 mol %) and CuI (1.5 equiv) Et3N (2.8 equiv), DMF, 80° C, 16 h; c) B2pin2 (1.1 equiv), KOAc (3 equiv), Pd(dppf)⋅CH2Cl2 (3 mol %), DMF; d) Chamber 1: Pd(dba)2 (10 mol %), PCy3 (10 mol %), KHCO2 (2 equiv), TBAI (0.3 equiv), butyronitrile, 100° C, 14 h. Chamber 2: Pd[COD]Cl2 (10 mol %), P t Bu3 (10 mol %), 9‐methylfluorene‐9‐carbonyl chloride (COgen) (0.4 mmol), Cy2NMe (2 equiv), butyronitrile, 100° C, 14 h; e) n BuMgCl (2 M Et2O, 2 equiv), ZnCl2 (1 M in THF, 0.22 mmol) and LiCl (2.5 M in THF, 0.22 mmol), PdI (2.5 mol %), r.t., 20 min; f) quinuclidine (0.1 equiv), Ir[dF(CF3)ppy]2(dtbbpy)PF6 (1 mol %), NiCl2⋅DME (5 mol %), dtbbpy (5 mol %) 1,2,3,4‐di‐O‐isopropylidene‐D‐galactopyranose (1.5 equiv) K2CO3 (1 equiv), MeCN, blue LED, r.t., 24 h.

Finally, we set out to examine whether our method potentially also extends to formamides that do not contain the N−CF3 substituent, as there is currently no straightforward reduction of carbamoyl halides known. We were able to reduce several N,N′‐disubstituted carbamoyl fluorides (41–44) and chlorides (45, 46) (Scheme 2, right). Aryl and alkyl carbamoyl halides were amenable to this protocol, although extended reaction times and slightly elevated reaction temperatures were required to reach full conversion. Deuteration was also feasible, which offers an alternative approach to the synthesis of d1 ‐formyl compounds, circumventing the need for high pressure of CO2 gas as commonly employed in formylations. [35]

To gain insight on the conformational flexibility, we performed variable temperature NMR studies on compounds 21 and 41 (i.e. biphenyl N−CF3 formamide versus its N−Me analogue). These studies confirm the anticipated greater flexibility of the N−CF3 formamide. While the N−Me compound 41 showed a second rotamer up to 75° C, consistent with literature reports, [13a] the corresponding N−CF3 analogue does not even show a second rotamer at room temperature. Only upon cooling, a second rotamer becomes slightly visible from 15° C, and clearly visible at 5° C as judged by 1H NMR and 19F NMR spectroscopic analyses (see Supporting Information for additional information).

In summary, we have developed a mild and operationally simple approach to unlock the first synthetic access to N−CF3 formamides via straightforward reduction of readily accessible and bench‐stable N−CF3 carbamoyl fluorides with NaBH4 (or NaBD4 to access the deutero isotopologues). The method is characterized by simplicity, rapid speed (1 h at r.t.), tolerating a wide range of functional groups, including α‐ and β‐amino acids scaffolds under full conservation of stereochemical integrity. We showed that the method also extends more generally to carbamoyl halides not carrying the N−CF3 unit, for which there is—to date—also no straightforward reduction known. The newly made N−CF3 formyl motif proved to be highly robust, tolerating a wide range of synthetic manipulations under oxidative, reductive, basic or acidic conditions and including light‐ and/or transition metal‐assisted processes. Given the prevalence of the formamide motif in therapeutic drugs as well as numerous other functional molecules, we anticipate widespread interest and application of the presented method to tailor properties and unleash new function.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

We thank the European Research Council (ERC‐637993) for funding. Calculations were performed with computing resources granted by JARA‐HPC from RWTH Aachen University under project “jara0091”. We thank Dr. Theresa Sperger (RWTH Aachen) for X‐ray crystallographic analyses. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

F. G. Zivkovic, C. D.-T. Nielsen, F. Schoenebeck, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202213829; Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202213829.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.

References

- 1.P. Ball, “Navigating chemical space”, can be found under https://www.chemistryworld.com/features/navigating-chemical-space/8983.article, 2015.

- 2.

- 2a. Schiesser S., Cox R. J., Czechtizky W., Future Med. Chem. 2021, 13, 941–944; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Campos K. R., Coleman P. J., Alvarez J. C., Dreher S. D., Garbaccio R. M., Terrett N. K., Tillyer R. D., Truppo M. D., Parmee E. R., Science 2019, 363, eaat0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a. Champagne P. A., Desroches J., Hamel J.-D., Vandamme M., Paquin J.-F., Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9073–9174; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3b. Isanbor C., O'Hagan D., J. Fluorine Chem. 2006, 127, 303–319; [Google Scholar]

- 3c. Meanwell N. A., J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5822–5880; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3d. Müller K., Faeh C., Diederich F., Science 2007, 317, 1881–1886; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3e. Purser S., Moore P. R., Swallow S., Gouverneur V., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 320–330; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3f. Tomashenko O. A., Grushin V. V., Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 4475–4521; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3g. Zimmer L. E., Sparr C., Gilmour R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 11860–11871; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2011, 123, 12062–12074; [Google Scholar]

- 3h. Tlili A., Toulgoat F., Billard T., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 11726–11735; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 11900–11909. [Google Scholar]

- 4.For reviews, see:

- 4a. Ramos L. M., Rodrigues M. O., Neto B. A. D., Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 7260–7269; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4b. de Graaff C., Ruijter E., Orru R. V. A., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3969–4009. Selected examples: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4c. Wen Y., Xiong Y., Chang L., Huang J., Liu X., Feng X., J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 7715–7719; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4d. Jagtap S. B., Tsogoeva S. B., Chem. Commun. 2006, 4747–4749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.

- 5a. Wuts P. G. M. in Greene's Protective Groups in Organic Synthesis, (Ed.: Wuts P. G. M.), Wiley, Hoboken, 2014, pp. 895–1193; [Google Scholar]

- 5b. Sheehan J. C., Yang D.-D. H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958, 80, 1154–1158. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Formamides provide facile access to isonitriles, which serve as important reactants in multicomponent Passerini and Ugi reactions and beyond:

- 6a. Ugi R. M. I., Angew. Chem. 1958, 70, 702–703; [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Lygin A. V., de Meijere A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 9094–9124; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2010, 122, 9280–9311; [Google Scholar]

- 6c. Luo J., Chen G.-S., Chen S.-J., Li Z.-D., Liu Y.-L., Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 6598–6619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vardanyan R., Hruby V. in Synthesis of Best-Seller Drugs (Eds.: Vardanyan R., Hruby V.), Academic Press, Boston, 2016, pp. 357–381. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yamada K., Ojika M., Ishigaki T., Yoshida Y., Ekimoto H., Arakawa M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 11020–11021. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kumar P., Dubey K. K., RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 86954–86966. [Google Scholar]

- 10.

- 10a. Ma G., Zancanella M., Oyola Y., Richardson R. D., Smith J. W., Romo D., Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 4497–4500; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10b. Hett R., Fang Q. K., Gao Y., Wald S. A., Senanayake C. H., Org. Process Res. Dev. 1998, 2, 96–99. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu J., Zhu X., Kim S. J., Zhang W., Nat. Prod. Rep. 2016, 33, 1146–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.

- 12a. Huang L.-s., Cobessi D., Tung E. Y., Berry E. A., J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 351, 573–597; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12b. Miyoshi H., Tokutake N., Imaeda Y., Akagi T., Iwamura H., Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1995, 1229, 149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.For studies on the rotamer distribution of formamides, see:

- 13a. Bourn A. J. R., Gillies D. G., Randall E. W., Tetrahedron 1966, 22, 1825–1829; [Google Scholar]

- 13b. Meng G., Zhang J., Szostak M., Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 12746–12783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clayden J., Nature 2019, 573, 37–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Our calculations of the logP values of N−CF3 antimycin versus its N−H analogue gave: logP of N−H antimycin 2.8 (in wet octanol) and 2.4 (in dry octanol) and for N−CF3 antimycin analogue 3.7 (in wet octanol) and 3.3 (in dry octanol); calculated with COSMOtherm (F. Eckert, A. Klamt, COSMOtherm, Version C2.1, Release 01.11; COSMOlogic GmbH & Co. KG, Germany, 2010). See also:

- 15a. Leo A., Jow P. Y. C., Silipo C., Hansch C., J. Med. Chem. 1975, 18, 865–868; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15b. Hansch C., Leo A., Taft R. W., Chem. Rev. 1991, 91, 165–195. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Our calculations of the rotational barriers of N−CF3 antimycin versus its N−Me analogue gave: 16.8 kcal mol−1 and 15.7 kcal mol−1 for N−CF3 analogue and 21.9 kcal mol−1 and 23.2 kcal mol−1 for N−Me analogue.

- 17. Scattolin T., Bouayad-Gervais S., Schoenebeck F., Nature 2019, 573, 102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.

- 18a. Schiesser S., Chepliaka H., Kollback J., Quennesson T., Czechtizky W., Cox R. J., J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 13076–13089; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18b. Milcent T., Crousse B., C. R. Chim. 2018, 21, 771–781; [Google Scholar]

- 18c. Bouayad-Gervais S., Nielsen C. D. T., Turksoy A., Sperger T., Deckers K., Schoenebeck F., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 6100–6106; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18d. Turksoy A., Bouayad-Gervais S., Schoenebeck F., Chem. Eur. J. 2022, 28, e202201435; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18e. Nielsen C. D.-T., Zivkovic F. G., Schoenebeck F., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 13029–13033; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18f. Bouayad-Gervais S., Scattolin T., Schoenebeck F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 11908–11912; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 12006–12010; [Google Scholar]

- 18g. Scattolin T., Deckers K., Schoenebeck F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 221–224; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 227–230; [Google Scholar]

- 18h. Zhang R. Z., Huang W., Zhang R. X., Xu C., Wang M., Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 2393–2398; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18i. Liu S., Huang Y., Wang J., Qing F.-L., Xu X.-H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 1962–1970; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18j. Zhang R. Z., Zhang R. X., Wang S., Xu C., Guan W., Wang M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202110749; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202110749; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18k. Cao T., Retailleau P., Milcent T., Crousse B., Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 10351–10354; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18l. Liu J., Parker M. F. L., Wang S., Flavell R. R., Toste F. D., Wilson D. M., Chem 2021, 7, 2245–2255; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18m. Schneider L. N., Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 10973–10978; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18n. Zhang Z., He J., Zhu L., Xiao H., Fang Y., Li C., Chin. J. Chem. 2020, 38, 924–928; [Google Scholar]

- 18o. Motornov V., Markos A., Beier P., Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 3258–3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.For reviews on utilizing CO2 as a formylating agent, see:

- 19a. Hulla M., Dyson P. J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 1002–1017; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 1014–1029; [Google Scholar]

- 19b. Nasrollahzadeh M., Motahharifar N., Sajjadi M., Aghbolagh A. M., Shokouhimehr M., Varma R. S., Green Chem. 2019, 21, 5144–5167; [Google Scholar]

- 19c. Liu X.-F., Li X.-Y., Qiao C., He L.-N., Synlett 2018, 29, 548–555; [Google Scholar]

- 19d. Tlili A., Blondiaux E., Frogneux X., Cantat T., Green Chem. 2015, 17, 157–168. For select examples empolying alternative formylating agents, see: [Google Scholar]

- 19e. Chapman R. S. L., Lawrence R., Williams J. M. J., Bull S. D., Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 4908–4911; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19f. Dine T. M. E., Evans D., Rouden J., Blanchet J., Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 5894–5898; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19g. Ortega N., Richter C., Glorius F., Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 1776–1779; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19h. Suchý M., Elmehriki A. A. H., Hudson R. H. E., Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 3952–3955; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19i. Federsel C., Boddien A., Jackstell R., Jennerjahn R., Dyson P. J., Scopelliti R., Laurenczy G., Beller M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 9777–9780; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2010, 122, 9971–9974. [Google Scholar]

- 20.

- 20a. Umemoto T., Adachi K., Ishihara S., J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 6905–6917; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20b. van der Werf A., Hribersek M., Selander N., Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 2374–2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.For an isolated example it was shown that SmI2 allows the formal reduction of a carbamoyl halide, not via halide/hydride exchange but instead arising from a protic quench of a carbamoyl anion. See: Souppe J., Namy J. L., Kagan H. B., Tetrahedron Lett. 1984, 25, 2869–2872. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Uranga J. G., Gopakumar A., Pfister T., Imanzade G., Lombardo L., Gastelu G., Züttel A., Dyson P. J., Sustainable Energy Fuels 2020, 4, 1773–1779. [Google Scholar]

- 23.

- 23a. Schlesinger H. I., Brown H. C., Finholt A. E., Gilbreath J. R., Hoekstra H. R., Hyde E. K., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1953, 75, 215–219; [Google Scholar]

- 23b. Davis R. E., Gottbrath J. A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1962, 84, 895–898. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Padhi S. K., Chadha A., Synlett 2003, 2003, 0639–0642. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deposition Number 2204804 (for 16) contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by the joint Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe Access Structures service.

- 26. Pirali T., Serafini M., Cargnin S., Genazzani A. A., J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 5276–5297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee C.-S., Kim D., Hwang C.-S., Mol. Cells 2022, 45, 109–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chiu I. M., Nature 2013, 501, 52–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu X., Wang Y., O'Doherty G. A., Asian J. Org. Chem. 2015, 4, 994–1009. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rosen B. R., Ruble J. C., Beauchamp T. J., Navarro A., Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 2564–2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Korsager S., Taaning R. H., Lindhardt A. T., Skrydstrup T., J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 6112–6120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.

- 32a. Kalvet I., Sperger T., Scattolin T., Magnin G., Schoenebeck F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 7078–7082; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 7184–7188; [Google Scholar]

- 32b. Keaveney S. T., Kundu G., Schoenebeck F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 12573–12577; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 12753–12757. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Terrett J. A., Cuthbertson J. D., Shurtleff V. W., MacMillan D. W. C., Nature 2015, 524, 330–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Our preliminary investigations to activate and derivatize the N−CF3 formamide C−H bond, e.g. with photoinduced decatungstate catalysis, so far led to fully recovery of unreacted starting material. This lack of reactivity further underscores the superb stability of this new motif.

- 35. Zou Q., Long G., Zhao T., Hu X., Green Chem. 2020, 22, 1134–1138. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.