Abstract

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection/disease has been repeatedly reported in patients treated with immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and most commonly involves patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) immune-related adverse events (irAEs). In the current study, we present a patient with melanoma who developed CMV gastritis during treatment with pembrolizumab in the absence of irAEs and without previous or current immunosuppression. Moreover, we review the literature regarding CMV infection/disease in patients treated with ICIs for solid malignancies. We present the currently available data on the pathogenesis, clinical characteristics, endoscopic findings, and histologic features and highlight the potential differences among cases complicating R/R irAEs versus those occurring in patients who are immunosuppression naive. Finally, we discuss the currently available data regarding potential useful diagnostic tools as well as the management of these patients.

Keywords: cytomegalovirus, immune-checkpoint inhibitors, immune-related adverse events, immune-related colitis, review

Herein, we present a case of CMV gastritis in a melanoma patient treated with pembrolizumab without previous or current use of immunosuppressants and review the literature for CMV infection/disease in patients with solid malignancies under treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have been approved for the treatment of a variety of solid and hematological malignancies [1]. They target immune checkpoint molecules that are present on the surface of T cells, macrophages, and tumor cells and regulate their activity. Inhibition of these molecules results in immune system activation against tumor cells [2]. However, the modulation of immune response may trigger the development of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) affecting several organs. Management varies according to the affected organ and the severity of the toxicity, and it often requires the administration of systemic immunosuppressants [3].

There is a growing interest regarding the interplay between ICI use and infection risk. Del Castillo et al [4] reported an overall incidence of serious infections of 7.3%. However, the risk of serious infection was 13.5% in patients who received corticosteroids or infliximab and only 2% in those who did not.

Human cytomegalovirus (CMV) seroprevalence ranges from 45% to 100%, depending on age, socioeconomic factors, geography, and race [5]. Cytomegalovirus has developed mechanisms, such as latency, which facilitate the evasion from the host's immune system and subsequent dissemination, and is also able to reactivate to escape in situations threatening its survival [6]. In the clinical setting, the risk of reactivation depends on the level of T-cell immunity impairment and is particularly high in severely immunocompromised patients [7]. Given that ICIs enhance effector T-cell function, their use is not expected to increase the risk for CMV reactivation. Indeed, Tay et al [8] reported a cumulative incidence of CMV DNAemia and/or disease in ICI-treated patients with hematologic and solid malignancies of 0.3%. All cases of CMV disease in patients with solid malignancies complicated irAEs that required high-dose corticosteroids and other immunomodulatory drugs [8]. In contrast, cases of CMV reactivation in patients not previously treated with immunosuppressants are rare. In this study, we report a case of CMV gastritis complicating Helicobacter pylori gastritis in a patient with melanoma treated with pembrolizumab, without previous use of immunosuppressive treatment. In addition, we provide a comprehensive review of the published literature on CMV infections in patients treated with ICIs.

CASE PRESENTATION

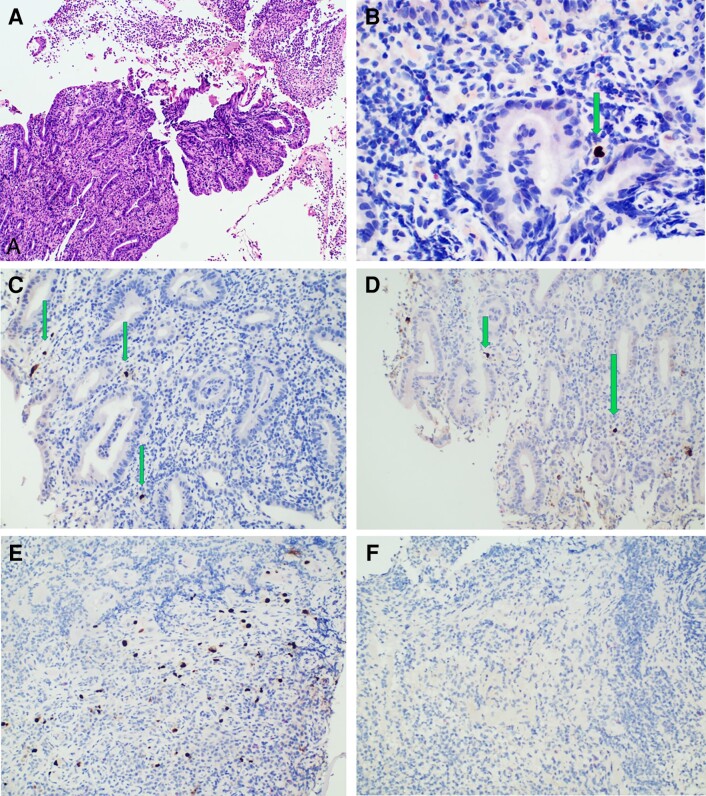

A 71-year-old female of European ancestry with a medical history of atrial fibrillation was diagnosed with a mucosal melanoma of the right maxillary sinus with lung and liver metastases [9]. Molecular analysis showed BRAF-wild type; therefore, she was started on pembrolizumab at 200 mg every 3 weeks and achieved partial response after cycle 20. During the 26th cycle, she reported epigastric pain and nausea. Physical examination was normal except for tenderness in the epigastrium. Blood tests revealed iron deficiency anemia; hemoglobin was 9.5 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume was 74 femtoliters, and ferritin was 5.3 ng/mL (normal range, 30–400 ng/mL). Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed mucosal erosions and ulcerations in the lesser curvature and pyloric antrum. Histology demonstrated multiple lesions of acute corrosive purulent H pylori gastritis of moderate severity, with score 1 lymphocyte aggregations according to Isaacson consistent with phlegmonous gastritis (Figure 1A). Despite the severity of pathology findings, an abdominal computed tomography (CT) demonstrated normal stomach morphology. She was therefore treated with a standard oral quadruple eradication regimen. Her symptoms rapidly resolved, and immunotherapy was resumed 4 weeks after gastritis treatment was completed. Four weeks after immunotherapy resumption, her symptoms relapsed. Follow-up EGD revealed inflammatory appearance of the pyloric antrum. Histology revealed the presence of abundant H pylori bacteria (grade >3) and phlegmonous gastritis. The severity of the lesions raised the suspicion of an additional infectious agent. Indeed, immunohistochemistry (IHC) demonstrated numerous CMV inclusions in capillary endothelial cells (Figure 1C). In addition, IHC for CMV was performed retrospectively in the first biopsy sample and identified rare CMV+ cells (Figure 1B). Α plasma quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for CMV-deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was negative, and serology demonstrated a CMV-immunoglobulin (Ig)G titer of 475 IU/mL (negative <10 IU/mL) and a CMV-IgM titer of 0.23 IU/mL (negative <0.7). The patient received intravenous ganciclovir (5 mg/kg twice daily) for 6 days, followed by valganciclovir (900 mg twice daily) for 15 days and oral salvage therapy for H pylori. Her symptoms resolved and secondary prophylaxis with valganciclovir 450 mg twice daily was introduced. Pembrolizumab was reinitiated after 5 weeks of antiviral treatment. The patient received 2 courses of pembrolizumab and thereafter reported mild epigastric pain. A third EGD was performed, which demonstrated inflammatory appearance of the antrum and duodenum. Helicobacter pylori infection was eradicated and IHC revealed few CMV+ cells (Figure 1D). Given that the underlying malignancy was in complete remission at recent CT restaging, permanent discontinuation of immunotherapy was decided. Two weeks later the symptoms resolved and an EGD performed 2 months later showed lesion persistence, whereas IHC revealed the presence of multiple CMV+ cells in one biopsy specimen and absence in another (Figure 1E and F). Three months later an EGD showed mild chronic gastritis, with absence of CMV+ cells on IHC, and prophylactic valganciclovir was discontinued. It should be noted that hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain was negative for cytopathic changes in all samples.

Figure 1.

Histological examination images of our patient. (A) Fibropurulent material and gastric mucosa with acute inflammation suggestive of phlegmonous gastritis, initial biopsy (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×100). (B) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for cytomegalovirus (CMV) was performed retrospectively at the initial biopsy specimen (anti-CMV CCH2 + DDG9, Dako Omnis; Agilent). A CMV+ nuclei was identified (IHC, ×200). (C) Several positive nuclei for CMV on second biopsy, which was performed 3 months later (IHC, ×200). (D) Positive nuclei for CMV in third biopsy, performed 4 months later (IHC, ×200); cytoplasmic staining was not evaluated. (E and F) A fourth esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed 2 months later, and IHC on multiple biopsy specimens revealed the presence of multiple CMV+ cells in one biopsy specimen (E) and absence in another (F).

Patient Consent Statement

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Laikon Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the case report.

DISCUSSION

We searched PubMed for articles with the combinations of the terms “cytomegalovirus”, “nivolumab”, “pembrolizumab”, “ipilimumab”, “immune-related adverse event”, and “immune checkpoint inhibitor”. We included cases with adequate information regarding presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and outcome. We identified 16 cases (including the case reported here), which are summarized in Table 1 [10–23].

Table 1.

Published Cases of CMV Infection/Disease in Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for Solid Malignancies

| Author, Year | Age, Sex | Cancer Type | ICI | Previous Systemic Therapy | CMV Infection/Disease | Reason for CMV Testing | Previous Immunosuppression-Reason | Treatment of CMV Disease -Duration |

Immunosuppression Modification | Cancer Treatment | Outcome of CMV Infection/Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uslu, 2015 [10] | 55, M | Melanoma | Iplimumab | N | Hepatitis | Transaminasemia | Prednisone Infliximab - ir-colitis |

Ganciclovir 5 mg/kg × 3 -6 weeks |

Tapered | Discontinued | Resolved |

| Lankes, 2016 [11] | 32, M | Melanoma | Ipilimumab/ nivolumab |

N | Colitis | R/R ir-colitis | Prednisolone Infliximab - ir-colitis |

Ganciclovir 5 mg/kg × 2, valganciclovir 900 mg × 2, escalation to ganciclovir, foscarnet 90 mg/kg × 2 -total of 10 weeks |

Tapered | Discontinued | Improved GI symptoms at 1-year follow up |

| Lu, 2018 [12] | 66 F |

Urothelial cancer | Pembrolizumab | Gemcitabine/ Cisplatin, atezolizumab |

Concurrent CMV- and ir-gastritis | Gastritis | NA | Ganciclovir 2.5 mg/kg × 2 -5 d |

NA | Withheld (NR if resumed) |

Asymptomatic after 5 d of antiviral treatment |

| Gueguen, 2018 [13] | 70 M |

Melanoma | Pembrolizumab | N | Colitis | Grade 4 ir-colitis | Mycophenolic acid, corticosteroids, (cyclosporine discontinued upon pembrolizumab initiation) -Kidney transplantation |

Ganciclovir, valganciclovir -NR |

Reduction of corticosteroids | Resumed | Resolved but relapse of diarrhea and DNAemia after ICI resumption |

| Van Turenhout, 2019 [14] |

73 F |

Melanoma | Ipilimumab/ nivolumab |

N | Colitis | R/R colitis | Prednisolone - ir-colitis |

Ganciclovir 5 mg/kg × 2 for 4 wks, valganciclovir 900 mg daily -total NR |

Initially decreased, increased due to worsening of colitis with fewer CMV-positive cells | NR | Resolved |

| Van Turenhout, 2019 [14] |

54 F |

Lung adenocarcinoma | Nivolumab | N | Colitis | R/R Colitis | Prednisolone, infliximab -ir-colitis |

Not administered |

Tacrolimus initiation | NR | Resolved with IST modifications |

| Harris, 2020 [15] | 66 M |

Melanoma | Nivolumab | N | Colitis | R/R Colitis | Prednisone, budesonide -ir-colitis |

Valganciclovir -1 mo |

Tapered | NR | Resolved at 2 mo follow up |

| Hulo, 2020 [16] | 35 F |

Colon cancer | Ipilimumab/ nivolumab |

N | Gastritis | ir-gastritis | Corticosteroids -ir-gastritis |

Ganciclovir 5 mg/kg × 1 for 3 d, valganciclovir 900 mg × 2 for 7 d, valganciclovir 900 mg × 1 for 7 d -total of 17 d |

Tapered | Nivolumab maintenance | Resolved |

| Furuta, 2020 [17] | 77 M |

Melanoma | Ipilimumab | Nivolumab | Colitis | Worsening of grade 2 ir-colitis | Methylprednisolone -Grade 2 ir-colitis |

Ganciclovir 5 mg/kg × 2 -40 d |

Tapered | NR | Resolved |

| Kim, 2020 [18] | 43 F |

Melanoma | Pembrolizumab | N | Gastritis | Gastritis | NA | Ganciclovir 5 mg/kg × 2 -3 wks |

(Before receipt of pathology report the patient received dexamethasone 10 mg daily for 3 d) |

Resumed after 3 wks of antiviral treatment | Resolved |

| Villanueva, 2020 [19] | 67 F |

Urothelial cancer | Pembrolizumab | Cisplatin/ gemcitabine, atezolizumab |

Gastritis | Gastritis | NA | Ganciclovir -NR |

NA | Resumed after 3 mo | Resolved |

| Badran, 2021 [20] | 63 M |

Squamous cell carcinoma | Pembrolizumab | N | Pneumonitis | R/R grade 4 ir-pneumonitis | Prednisone Mycophenolate mofetil -Grade 4 ir-pneumonitis |

Ganciclovir -until death |

Tapered | Discontinued | Died after 5 wks |

| Kadokawa, 2021 [21] | 58 M |

Lung adenocarcinoma | Durvalumab | Cisplatin/ vinorelbine |

Colitis | R/R grade 3 ir-colitis | Prednisolone Infliximab -Grade 3 ir-colitis |

Ganciclovir 5 mg/kg × 2 for 50 d and then 2.5 mg/kg × 2 |

Tapered | NR | Resolved |

| Smibert, 2021 [22] | 59 F |

Head and neck caner |

Pembrolizumab/carboplatin/ flouorouracil |

Chemoradiation (cisplatin) | CMV pseudotumor | Progressively enlarging painless oral cavity mass at the prior operative site of disease | NA | Ganciclovir 5 mg/kg × 2 for 4 wks, valganciclovir 900 mg × 2 for 4 wks, prednisolone 25 mg × 1 PO for 5 d, resection of the residual tumor |

NA | NR | Resolved |

| Nguyen, 2022 [23] | 55 M |

Renal cancer | Nivolumab | N | CMV gastritis | Refractory ir-gastritis | Steroids, Infliximab -ir-gastritis |

Ganciclovir -5 wks (self-discontinued) |

Tapered | NR | Resolved |

| Current report, 2022 | 71 F |

Melanoma | Pembrolizumab | N | HP gastritis and CMV gastritis | HP-refractory gastritis | NA | Ganciclovir 5 mg/kg twice daily for 6 d, Valganciclovir 900 mg twice daily for 15 d, valganciclovir 450 mg twice daily for 27 wks `-total of 30 wks |

NA | Resumed after 5 wks but ultimately discontinued | Resolved |

Abbreviations: d, day; GI, gastrointestinal; HP, Helicobacter pylori; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; IST, immunosuppressive treatment; ir, immune-related; F, female; M, male; mo, months; N, none; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported; R/R, relapsed/refractory; wks, weeks.

Incidence, Risk Factors, and Clinical Presentation of Cytomegalovirus Infections in Patients Treated With Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitors

The exact incidence of CMV reactivation among patients treated with ICIs is unknown but is considered low. As already mentioned, Tay et al [8] reported a low cumulative incidence (0.3%) of CMV diagnosis in patients treated with ICIs. In patients with solid malignancies, CMV colitis complicated 3.8% of patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) immune-related colitis (IRC) [8]. Among 41 cases of IRC, Franklin et al [24] detected CMV reactivation in 5 patients with refractory to steroids and infliximab IRC.

The present study comprises case reports; therefore, no safe conclusions regarding the incidence and risk factors nor solid recommendations for CMV disease can be made. However, some useful observations emerge. Ten CMV cases (62.5%) followed R/R irAEs. Eleven patients had previous and/or current receipt of immunosuppression: 7 of 11 (64%) presented with CMV colitis; 2 presented with CMV gastritis; 1 presented with CMV pneumonitis; and 1 presented with hepatitis. The remaining 5 of 16 cases (including the case presented here) developed CMV disease without a history of immunosuppressive treatment: 4 had CMV gastritis, and 1 had CMV pseudotumor of the left lower jaw. In 3 of them, CMV disease developed either concurrently with an irAE [12] or at sites of a previous inflammation (current report and [22]). Fifteen patients underwent a biopsy of the affected organ and in 14 of 15, cytopathic changes consistent with CMV disease were identified on histology. In 2 patients, diagnosis was supported by CMV-DNAemia combined with histologic findings indicative of viral hepatitis [10] and CMV-PCR on bronchoalveolar lavage [20], respectively.

Pathogenesis of Cytomegalovirus Reactivation in Patients Treated With Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitors

Inflammation is considered a key driver of CMV reactivation, which occurs in response to inflammation-associated signaling [25]. Tumor necrosis factor promotes major immediate early (MIE) gene expression, which is required for lytic infection [26]. In individuals who are immunocompromised, immune function loss further allows the virus to replicate uncontrollably, leading to viremia and disease [25]. Moreover, CMV is characterized by tropism to inflamed tissue. Indeed, CMV infection has a high prevalence in patients with severe acute inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and is even more frequent in patients with steroid-refractory disease [27]. During active IBD, local expression of proinflammatory proteins may ultimately stimulate the recruitment of latently CMV-infected immune cells and their differentiation in permissive cells that support active replication [28]. Furthermore, CMV-infected endothelial cells activate T cells and may further drive proinflammatory responses [28, 29].

It is interesting to note that, in patients with R/R irAEs reviewed in this study, CMV disease occurred in the organ primarily affected by the irAE, with the exception of 1 patient with CMV hepatitis after high-dose steroid treatment for IRC. However, this patient had transaminasemia at baseline, indicative of a pre-existing liver inflammation (attributed to liver metastases) [10]. Because it occurs in IBD, tissue inflammation in the context of a severe irAE could potentially be the driver of CMV reactivation, further aggravated by the use of immunosuppression. During IRC, proinflammatory pathways are enhanced, whereas anti-inflammatory pathways are inhibited. These phenomena promote neutrophil infiltration and disruption of the epithelial barrier, leading ultimately to interaction between the gut microbiome and immune cells [30]. Multi-Epitope-Ligand-Cartography (MELC) analyses in colon biopsy specimens from a patient with CMV colitis and steroid-refractory IRC showed (1) a gradual increase in the number of natural killer cells and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein-4 positive cells and (2) a shift in the distribution of B cells, CD8+ T cells, memory T cells, and CD45+ T cells within the tissue [11]. Moreover, differences in gene expression of multiple markers were shown between the 2 time points (before and during CMV), signifying a potential role of these markers in CMV reactivation [11]. Nevertheless, further research is needed to understand the mechanisms underlying CMV reactivation in patients with irAEs after ICI use.

Concurrent CMV and H pylori gastritis is rare and has been reported in children with Menetrier's disease [31], in whom eradication of H pylori led to endoscopic and clinical improvement. The occurrence of CMV reactivation at sites of inflammation in patients treated with ICIs but without previous or concurrent immunosuppression further highlights the role of local inflammation in CMV reactivation but also suggests a potential role for dysregulated inflammation attributed to the use of ICIs. It has been shown that ICIs may boost virus-specific T-cell activity [32]. Programmed cell death protein (PD)-1+ T cells infiltrating areas with cytopathic effect and reactivating virus, as well as extensive areas of PD-L1 staining, were noted in a patient with a CMV pseudotumor. Smibert et al proposed that localized trauma (because of tumor resection) triggered increased viral shedding. Subsequently, the addition of ICI led to the restoration of virus-specific T cells and an exaggerated inflammatory response to CMV antigens, leading to an immune reconstitution inflammatory-like syndrome [22]. The severity of pathology findings in our patient, despite the low numbers of identified CMV+ cells, is consistent with the above mechanism.

Diagnosis of Cytomegalovirus Disease in Patients Treated With Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitors

The definition of CMV end-organ disease requires the presence of appropriate clinical symptoms and/or signs together with documentation of CMV in tissue from the affected organ [33]. Because the majority of CMV cases occur in ICI-treated patients with R/R irAEs, one problem is to differentiate between CMV infection and disease not to mention assessing the severity of CMV disease. This problem is illustrated in patients with CMV-positive ulcerative colitis [34, 35].

No specific endoscopic findings were observed in the present study (Table 2). However, endoscopy with new or worsening lesions in patients with previously diagnosed irAEs should raise the suspicion of CMV disease [11, 16, 17, 21]. Moreover, CMV disease should be suspected in cases of gastritis in immunosuppression-naive patients.

Table 2.

Endoscopic Findings, Histology and Laboratory Tests of Patients With CMV Infection/Disease Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for Solid Malignancies

| Author, Year | Endoscopy Upon irAE Diagnosis | Histology Upon irAE Diagnosis | CMV Testing When irAE Was Diagnosed | Endoscopy Upon CMV Infection Diagnosis | Histology Upon CMV Infection Diagnosis | CMV Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uslu, 2015 [10] |

Inflammation of descending and sigmoid colon, with active bleeding and denuded mucosa |

Infiltration of LP with PMN/LYM, PC, crypt abscesses, mucosal ulceration |

−Colon sample IHC (−) -Stool culture (−) |

NA | Few lobular spotty hepatocyte necrosis demarcated by mononuclear infiltrates and macrophages | −CMV IgM (+) IgG(+) -Blood PCR-CMV > 81 000 copies/mL -Liver biopsy consistent with viral hepatitis |

| Lankes, 2016 [11] |

Erythematous, granulomatous and oedematous mucosal inflammation of rectosigmoid colon, mucosal vulnerability | Prominent PC-rich inflammatory infiltrates in LP, crypt abscess formation | ND | Grainy white pattern suggesting an overlapped infectious origin | Crypt epithelium showing regenerative changes with large intranuclear inclusions, LP contained mixed infiltrates with prominent dilated capillaries | −Blood PCR-CMV at 140 000 copies/mL -Colon sample IHC (+) and PCR-CMV at 20 000 copies/100 000 cells |

| Lu, 2018 [12] |

NA | NA | NA | Diffuse severely erythematous mucosa with bleeding on contact involving entire stomach and diffuse nodular, inflamed and ulcerated mucosa in the gastric antrum with narrowing of the pyloric channel | Marked LP mononuclear infiltration, lymphoid aggregates, crypt Apoptosis/dropout, apoptotic abscesses, crypt epithelial infiltration with LYM and PMN, focal erosion, ulceration. Oxyntic glands significantly lost and residual glands with regenerative and hyperplastic changes |

−Gastric tissue IHC and routine stain with presence of CMV infected cells -Blood PCR-CMV <100 copies/mL |

| Gueguen, 2019 [13] |

ND | ND | ND | Severe pancolitis | fibroedematous mucous membrane remodeling | −Βlood PCR-CMVat 67 200 IU/mL -Colon sample IHC (+) |

| Van Turenhout, 2019 [14] |

Mild, nonulcerative, nonspecific colitis of entire colon |

Increased LP cellularity and active cryptitis and crypt abscesses | Colon sample IHC (−), performed retrospectively | Severe nonspecific ulcerative colitis | Much more pronounced inflammation and many enlarged atypical cells with viral changes | −Colon sample IHC: the highest count in a single HPF was 120 CMV (+) cells -Fecal sample PCR-CMV (+) -Blood PCR-CMV (after 1 wk) at 42.000 copies/mL |

| Van Turenhout, 2019 [14] |

Mild proctitis with miliary erosions up to 20 cm from the anal verge |

Increased LP cellularity and cryptitis. Minimal patchy increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes | Stool CMV culture (−) Colon sample IHC for CMV (−) performed retrospectively |

Erosive and ulcerative colitis of the left colon (proximal border not seen) | Severe active inflammation, but now with signs of chronicity |

−Colon sample IHC: the highest count in a single HPF was 24 CMV (+) cells -Serum PCR-CMV at 356 copies/mL |

| Harris, 2020 [15] |

ND | ND | ND | Mild erythema and localized punctuate ulcerations | An “owl's eye” inclusion body | −Colon biopsy inclusion bodies (+) -PCR-CMV at 631 IU/mL |

| Hulo, 2020 [16] |

Erythema with large detached shreds of gastric mucosa |

Findings indicative of ulcerative lymphocytic gastritis | Gastric sample IHC (−) | Coexistence of some healing lesions and microulcerative pangastritis | Lymphocytic gastritis | −Colon biopsy CMV cells (+) -Blood PCR-CMV at 2825 IU/mL |

| Furuta, 2020 [17] |

Coarse mucosa that was easily bleeding and contained purulence and erosions |

NR | Blood CMV antigen (−) | Multiple punched-out ulcers in the descending colon. Remission of ir-colitis in the sigmoid colon and rectum |

Crypt abscesses and LYM and PC infiltration | −Colon sample IHC (+) -Blood CMV antigen (−) |

| Kim, 2020 [18] |

NA | NA | NA | Diffuse oozing, hemorrhagic, edematous, exfoliative mucosa in gastric wall and several erosions in duodenum | Inflamed granulation tissue and necrotic detritus | Gastric sample IHC (+) |

| Villanueva, 2020 [19] |

NA | NA | NA | Diffuse severely erythematous mucosa with bleeding on contact in the entire examined stomach |

Severe chronic active gastritis with ulceration. Lymphoplasmacytic inflammation, LP PMN inflammation, intraepithelial lymphocytosis, crypt apoptosis and necrosis. Atrophy of oxyntic glands |

−Gastric sample IHC (+) -Serum PCR-CMV <100 copies/mL |

| Badran, 2021 [20] |

ND | ND | ND | Bronchoscopy | NA | −BAL PCR-CMV (+) -Serum IgM CMV (+) |

| Kadokawa, 2021 [21] |

Erosions and friability | … | … | Worsening of mucosal erosion and friability after transient improvement | NR | −Colon biopsy CMV cells (+) |

| Smibert, 2021 [22] |

NA | NA | NA | NA | Ulcerated granulation tissue and without evidence of malignancy | −Lesion sample IHC for CMV (+) -Immunostains for other Herpesviruses (−) Blood PCR-CMV (−) |

| Nguyen, 2022 [23] |

Diffuse erythematous and friable mucosa, mucosal sloughing of entire stomach | LP infiltration with inflammatory cells and erosive mucosa | Gaastric IHC (−) | Diffuse severe inflammation with adherent blood, erosions, erythema, friability, granularity, confluent ulcerations of entire stomach | Severe granulations and ulceration | −Gastric sample H&E and IHC (+), -Serum PCR-CMV at 3.457 IU/mL |

| Current report, 2022 |

Ulcerations and erosive spots of lesser curvature and pyloric antrum mucosa | Multiple lesions of acute corrosive purulent HP gastritis of moderate severity and activity | IHC performed retrospectively, revealed a CMV+ cell | Erythematous and inflammatory appearance of the pyloric antrum | Presence of abundant HP bacteria (grade > 3) | −Gastric tissue IHC (+) -Plasma CMV-DNA (−) |

Abbreviations: BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; CMV, cytomegalovirus; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin stain; HP, Helicobacter pylori; HPF, high-powered field; IHC, immunohistochemistry; Ig, immunoglobulin; irAE, immune-related adverse events; LP, lamina propria; LYM, lymphocyte; NA, not applicable; ND, not determined; NR, not reported; PC, plasma cell; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PMN, polymorphonuclear leukocyte.

The demonstration of cytopathic changes in tissue samples of the affected organ by conventional H&E stain is considered the “gold standard” for the diagnosis of CMV disease in patients with IBD [36], although its sensitivity ranges from 10% to 87% [37]. Immunohistochemistry increases the sensitivity, but the clinical significance of its routine use has been questioned [38]. In the context of an irAE, there are no clearly defined histologic findings to discriminate between CMV infection and disease. Nguyen et al [39] stratified patients with IBD into having “high-grade CMV infection” and having “low-grade CMV infection” based on CMV detection on H&E and IHC or IHC alone; antiviral treatment improved outcomes only in patients with CMV detection on H&E (44% vs 83%). The density of CMV-infected cells may also be relevant. Beswick et al [36] proposed a cutoff of ≥5 inclusion bodies per biopsy (by H&E or IHC) to guide decision making in cases of IBD. Similarly, van Turenhout et al [14] suggested that antivirals should be started in steroid-refractory cases with >50 CMV-positive cells on IHC, or in patients with a relatively low number of CMV-positive cells on IHC accompanied by a high viral load in serum. We should emphasize that the above criteria were only described for patients with previous R/R irAEs under immunosuppressive treatment. In the remaining cases, as in the case presented here, the demonstration of CMV in tissue samples along with the presence of relevant symptoms and macroscopic lesions upon endoscopy and absence of an alternative diagnosis is probably sufficient to diagnose CMV disease. Our patient had concurrent H pylori infection; however, she was symptomatic even after eradication of H pylori. We cannot rule out that our patient had immune-related gastritis and concurrent CMV infection rather than disease. However, she improved without administration of corticosteroids. The above observations favor the diagnosis of CMV gastritis.

Quantitative PCR for the detection of CMV DNA in the blood or serum was used in 11 of 16 patients. Higher viral loads (defined as >1000 IU/mL or >1000 copies/mL) were reported in 6 of 11 (54%) patients. All of these cases had steroid-refractory irAEs [10, 11, 13, 14, 16, 17]. Therefore, viral load could facilitate the diagnosis in patients with R/R irAEs. Moreover, it might be useful for monitoring treatment response. Tissue quantitative PCR for CMV-DNA in the mucosal lesion may be useful. It has been suggested that in IBD, it can assist the differentiation between CMV colitis and infection [40].

Multiple biopsies from different sites may be needed to diagnose CMV disease because the density of CMV+ cells among different biopsy specimens varies [14]. Indeed, in our patient, different biopsy specimens taken during the 4th EGD provided different IHC results. The recommended number of biopsies for patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease is 11 and 16, respectively [41]. Moreover, biopsies taken from the ulcer base or edge may be more appropriate compared with uninvolved mucosa, as in IBD [42]. Currently available data is insufficient to determine the adequate number of specimens for diagnosis of CMV disease in patients treated with ICI and whether this number should be different depending on the affected organ.

Treatment of Cytomegalovirus Infection/Disease in Patients Treated With Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitors

In general, first-line treatment of CMV disease consists of intravenous ganciclovir, but both regimen selection and treatment duration should be individualized. Almost all patients with CMV disease while on treatment with ICIs received antiviral therapy (15 of 16, 94%). However, as previously mentioned, in some cases CMV detection may represent infection rather than end-organ disease. In the absence of clearly defined criteria, we suggest that antiviral treatment should be given to all immunosuppression-naive patients as well as to patients with R/R irAEs who present with high blood and/or serum viral load and/or ≥50 infected cells by IHC per biopsy (as proposed by van Turenhout et al [14]) or ≥5 inclusion bodies per biopsy (as proposed for IBD [36]). Caution is required because a negative single biopsy sample or a sample with fewer CMV-infected cells may be inadequate to exclude the diagnosis of CMV disease and multiple biopsy samples may be needed.

Reduction of immunosuppressive treatment, when feasible, is strongly suggested for patients with CMV disease. Among patients treated with immunosuppressants, 10 of 11 patients were managed with antiviral therapy along with decrease of immunosuppressants. It is interesting to note that 1 patient with IRC and CMV disease did not improve until immunosuppression was intensified [14]. Therefore, upon lack of improvement, persistence of the underlying irAE should be considered and treated accordingly [14].

Permanent discontinuation of immunotherapy upon CMV disease diagnosis was reported only in patients with CMV disease superimposing irAEs. Τhe decision was probably driven by the severity of the irAE rather than the CMV disease itself, given that currently available guidelines recommend discontinuation in severe irAEs. Resumption of ICI was reported in 2 such patients and resulted in relapse of diarrhea and CMV DNAemia in one of them [13]. In the second patient, the regimen was changed from ipilimumab/nivolumab to pembrolizumab maintenance [16].

The management of CMV disease in immunosuppression-naive patients is challenging. Immune-checkpoint inhibitor administration was temporarily discontinued in all 5 such cases reviewed here. Resumption was reported in 3 of 5 patients and resulted in symptom relapse only in our patient. It is interesting to note that treatment resumption was decided on the basis of resolution of symptoms of CMV disease; however, this alone might be insufficient to guide management. Additional assessment with endoscopy before ICI reinitiation may be needed to minimize the risk of CMV disease relapse.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study comprises case reports; therefore, it does not allow for the estimation of the incidence of CMV infection/disease and may also reflect publication biases. However, some useful conclusions can be drawn. Cytomegalovirus infection and/or disease in patients treated with ICIs occurs mostly in patients treated with immunosuppressants for irAEs and less commonly in immunosuppression-naive patients. In immunosuppressed patients, inflammation due to an irAE may trigger localized CMV reactivation, which is left uncontrolled due to the use of immunosuppressants. In immunosuppression-naive patients, ICI use may induce an exaggerated inflammatory response to CMV reactivation. The demonstration of CMV on histology is probably sufficient for the diagnosis of CMV disease, in the absence of an alternative etiology of the clinical syndrome. Relapsed and/or refractory irAEs should raise the suspicion of CMV infection or disease. In such patients, the proposed criteria for density of CMV-infected cells as well as viral load may be helpful in the distinction between CMV infection and disease. Cytomegalovirus should also be included in the differential diagnosis of ICI-treated, immunosuppression-naive patients who present with gastritis. Finally, although sufficient data are lacking, and given the potential catastrophic consequences of CMV disease if left untreated, we believe that antiviral treatment should be strongly encouraged, with the exception, probably, of a subgroup of patients with R/R irAEs in whom the probability of CMV disease is very low.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions. AA contributed to data acquisition and analysis and conceptualized and wrote the manuscript. MS, PD, DCZ, and JH critically reviewed the manuscript. CV, PA, and PK contributed to data acquisition. HG contributed to data analysis and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the submitted version.

Contributor Information

Amalia Anastasopoulou, First Department of Internal Medicine, Laikon General Hospital, Medical School of National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece.

Michael Samarkos, First Department of Internal Medicine, Laikon General Hospital, Medical School of National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece.

Panagiotis Diamantopoulos, First Department of Internal Medicine, Laikon General Hospital, Medical School of National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece.

Christina Vourlakou, Department of Pathology, Evaggelismos Hospital, Athens, Greece.

Dimitrios C Ziogas, First Department of Internal Medicine, Laikon General Hospital, Medical School of National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece.

Pantelis Avramopoulos, First Department of Internal Medicine, Laikon General Hospital, Medical School of National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece.

Panagiotis Kouzis, First Department of Internal Medicine, Laikon General Hospital, Medical School of National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece.

John Haanen, Division of Medical Oncology, Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Helen Gogas, First Department of Internal Medicine, Laikon General Hospital, Medical School of National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece.

References

- 1. Robert C. A decade of immune-checkpoint inhibitors in cancer therapy. Nat Commun 2020; 11:3801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ramsay AG. Immune checkpoint blockade immunotherapy to activate anti-tumour T-cell immunity. Br J Haematol 2013; 162:313–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schneider BJ, Naidoo J, Santomasso BD, et al. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: ASCO guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2021; 39:4073–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Del Castillo M, Romero FA, Arguello E, et al. The spectrum of serious infections among patients receiving immune checkpoint blockade for the treatment of melanoma. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63:1490–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cannon MJ, Schmid DS, Hyde TB. Review of cytomegalovirus seroprevalence and demographic characteristics associated with infection. Rev Med Virol 2010; 20:202–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Forte E, Zhang Z, Thorp EB, Hummel M. Cytomegalovirus latency and reactivation: an intricate interplay with the host immune response. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020; 10:130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Styczynski J. Who is the patient at risk of CMV recurrence: a review of the current scientific evidence with a focus on hematopoietic cell transplantation. Infect Dis Ther 2018; 7:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tay KH, Slavin MA, Thursky KA, et al. Cytomegalovirus DNAemia and disease: current-era epidemiology, clinical characteristics and outcomes in cancer patients other than allogeneic hematopoietic transplantation. Intern Med J 2022; 52:1759–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Amin MB, Greence FL, Edge SB. The eighth edition AJCC cancer staging manual: continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; 67:93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Uslu U, Agaimy A, Hundorfean G, et al. Autoimmune colitis and subsequent CMV-induced hepatitis after treatment with ipilimumab. J Immunother 2015; 38:212–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lankes K, Hundorfean G, Harrer T, et al. Anti-TNF-refractory colitis after checkpoint inhibitor therapy: possible role of CMV-mediated immunopathogenesis. Oncoimmunology 2016; 5:e1128611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lu J, Firpi-Morell RJ, Dang LH, et al. An unusual case of gastritis in one patient receiving PD-1 blocking therapy: coexisting immune-related gastritis and cytomegaloviral infection. Gastroenterology Res 2018; 11:383–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gueguen J, Bailly E, Machet L, et al. CMV disease and colitis in a kidney transplanted patient under pembrolizumab. Eur J Cancer 2019; 109:172–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Turenhout ST, Berghuis M, Snaebjornsson P, et al. Cytomegalovirus in steroid-refractory immune checkpoint inhibition-related colitis. J Thorac Oncol 2020; 15:e15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harris KB, Funchain P, Baggott BB. CMV coinfection in treatment refractory immune checkpoint inhibitor colitis. BMJ Case Rep 2020; 13:e233519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hulo P, Touchefeu Y, Cauchin E, et al. Acute ulceronecrotic gastritis with cytomegalovirus reactivation: uncommon toxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors in microsatellite instability-high metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2020; 19:e183–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Furuta Y, Miyamoto H, Naoe H, et al. Cytomegalovirus enterocolitis in a patient with refractory immune-related colitis. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2020; 14:103–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim H, Ha SY, Kim J, et al. Severe cytomegalovirus gastritis after pembrolizumab in a patient with melanoma. Curr Oncol 2020; 27:e436–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Villanueva F, Yuan C, Drane W, et al. Cancer treatment response to checkpoint inhibitors is associated with cytomegalovirus infection. Cureus 2020; 12:e6670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Badran O, Ouryvaev A, Baturov V, Shai A. Cytomegalovirus pneumonia complicating immune checkpoint inhibitors-induced pneumonitis: a case report. Mol Clin Oncol 2021; 14:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kadokawa Y, Takagi M, Yoshida T, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab for steroid-resistant immune-related adverse events: a retrospective study. Mol Clin Oncol 2021; 14:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smibert OC, Allison CC, Doerflinger M, et al. Pseudotumor presentation of CMV disease: diagnostic dilemma and association with immunomodulating therapy. Transpl Infect Dis 2021; 23:e13531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nguyen AH, Sagvand BT, Hwang DG, et al. Isolated gastritis secondary to immune checkpoint inhibitors complicated by superimposed cytomegalovirus infection. ACG Case Rep J 2022; 9:e00747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Franklin C, Rooms I, Fiedler M, et al. Cytomegalovirus reactivation in patients with refractory checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis. Eur J Cancer 2017; 86:248–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Griffiths P, Reeves M. Pathogenesis of human cytomegalovirus in the immunocompromised host. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021; 19:759–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fietze E, Prosch S, Reinke P, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in transplant recipients. The role of tumor necrosis factor. Transplantation 1994; 58:675–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Criscuoli V, Casa A, Orlando A, et al. Severe acute colitis associated with CMV: a prevalence study. Dig Liver Dis 2004; 36:818–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hommes DW, Sterringa G, van Deventer SJ, et al. The pathogenicity of cytomegalovirus in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and evidence-based recommendations for future research. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2004; 10:245–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Waldman WJ, Adams PW, Orosz CG, Sedmak DD. T lymphocyte activation by cytomegalovirus-infected, allogeneic cultured human endothelial cells. Transplantation 1992; 54:887–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Westdorp H, Sweep MWD, Gorris MAJ, et al. Mechanisms of immune checkpoint inhibitor-mediated colitis. Front Immunol 2021; 12:768957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yoo Y, Lee Y, Lee YM, Choe YH. Co-infection with cytomegalovirus and Helicobacter pylori in a child with Menetrier's disease. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr 2013; 16:123–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Johnson DB, McDonnell WJ, Gonzalez-Ericsson PI, et al. A case report of clonal EBV-like memory CD4(+) T cell activation in fatal checkpoint inhibitor-induced encephalitis. Nat Med 2019; 25:1243–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ljungman P, Boeckh M, Hirsch HH, et al. Definitions of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in transplant patients for use in clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64:87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Delvincourt M, Lopez A, Pillet S, et al. The impact of cytomegalovirus reactivation and its treatment on the course of inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39:712–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim YS, Kim YH, Kim JS, et al. The prevalence and efficacy of ganciclovir on steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis with cytomegalovirus infection: a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Gastroenterol 2012; 46:51–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Beswick L, Ye B, van Langenberg DR. Toward an algorithm for the diagnosis and management of CMV in patients with colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016; 22:2966–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kandiel A, Lashner B. Cytomegalovirus colitis complicating inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101:2857–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Solomon IH, Hornick JL, Laga AC. Immunohistochemistry is rarely justified for the diagnosis of viral infections. Am J Clin Pathol 2017; 147:96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nguyen M, Bradford K, Zhang X, Shih DQ. Cytomegalovirus reactivation in ulcerative colitis patients. Ulcers 2011; 2011:282507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ciccocioppo R, Racca F, Paolucci S, et al. Human cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus infection in inflammatory bowel disease: need for mucosal viral load measurement. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21:1915–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McCurdy JD, Jones A, Enders FT, et al. A model for identifying cytomegalovirus in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13:131–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zidar N, Ferkolj I, Tepes K, et al. Diagnosing cytomegalovirus in patients with inflammatory bowel disease–by immunohistochemistry or polymerase chain reaction? Virchows Arch 2015; 466:533–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]