This article is the fifth in our series on sexual wellbeing and its core components. Together, these brief papers aim to provide a foundation of knowledge, which clinicians can draw upon when assessing sexual functioning. The present article is the first to focus on factors that may negatively impact sexual wellbeing and contribute to sexual dysfunction. Specifically, it examines psychosocial factors, which, along with neurophysiological factors, that will be considered separately in a future QuiP, often contribute to sexual problems.

We begin by outlining foundational principles regarding the psychological factors that can lead to sexual dysfunction in any individual, and then build on this with further information that pertains specifically to individuals with mental illness.

1. SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION

It is important to note that whilst DSM lists a number of formal sexual disorders, these are not common in routine in clinical practice and not easily assessed. Instead, in clinical assessments involving mental health it is far more useful to describe any sexual dysfunction that causes significant distress in terms of the actual symptoms the person is experiencing (e.g., loss of libido, erectile dysfunction, difficulty achieving orgasm). In addition, it is critical to bear in mind that sexual experiences are inherently psychological and subject to the attachment of personal meaning. These then guide our expectations of what our sexual experiences should entail.

Although we have mentioned the importance of assessing sexual wellbeing previously, it is important to note that sexual dysfunction is surprisingly common. Indeed, it verges on being the norm with an estimated 45% of all couples experiencing some form of sexual dysfunction at some time or another. 1

The most common sexual dysfunction reported by females is low sexual desire (33.4%), followed by inhibited orgasm (24.1%), whereas in males the most common problem is premature ejaculation (28.5%) followed by performance anxiety (17%). 2 However, it is also very common for most individuals experiencing sexual dysfunction to feel as though they are among a rare minority experiencing such difficulties. This is because even though the topic of sex seems to be ubiquitous, sexual problems or difficulties are seldom discussed, and may not be disclosed even within a medical context.

2. PSYCHOLOGICAL COMPONENTS OF SEXUAL FUNCTIONING

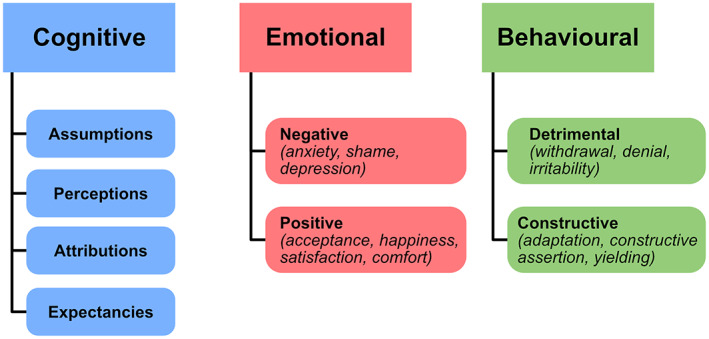

When examining the psychological components that can contribute to sexual dysfunction, the cognitive‐behavioural‐emotional (CBE) model serves as a useful framework. This is often utilized in cognitive behavioural therapeutic settings to address various kinds of sexual dysfunction. The CBE model posits that psychological components comprise cognitive, behavioural and emotional domains, which when disrupted can contribute to sexual dysfunction (see Figure 1). These domains are further divided into sub‐components that interact with one another and when disturbed can contribute to the development and maintenance of sexual dysfunction.

FIGURE 1.

The CBE Model. This model adapted from Metz et al., 2018, 3 is based on an earlier version for use in couples. It posits that the psychological components of sexual function (and dysfunction) emerge from cognitive, behavioural and emotional domains. Although originally developed for use in couples, the CBE model can be usefully applied to explain the psychological factors that contribute to sexual dysfunction in individuals.

Considering cognitive schemas, these play a significant role in sexual wellbeing, and when negative thinking takes hold, it can impair sexual functioning. For example, following a negative sexual experience (e.g., erectile dysfunction, inhibited orgasm, pain), it is possible to develop a ‘negative expectancy’, which in turn may lead to performance anxiety. If then, in this context, performance is again poor, this reinforces and further entrenches the initial negative cognitions. Other cognitive factors that can play a role include unrealistic standards for sexual experience, which is increasingly common because of widespread exposure to pornography, and ‘spectatoring’ wherein an individual self‐consciously monitors and evaluates their experience rather than focusing on the sensation of the experience itself. Both of these factors can be addressed with psychoeducation.

Typically, it is cognitive factors such as these that are amongst the primary factors that have triggered and maintained sexual dysfunction. For example, if a woman has an assumption that women should always orgasm during sex, but this then does not occur on a few occasions in her experiences, she may develop negative attributions regarding the cause, such as ‘I am flawed, … something is wrong with me, … something is wrong with my relationship’. This can then lead to feelings of anxiety, frustration, embarrassment, and even shame. In addition, she may develop negative expectancies regarding sex, resulting in avoidance and withdrawal from sexual activities. Thus, a cycle is created and perpetuated, and this can result in what then seems to be a sustained loss of sexual interest, increased anxiety, and depression.

The above example demonstrates how sexual dysfunction can be deconstructed into its psychological constituents and traced back to contributing factors, which can then be systematically addressed.

3. SEXUAL FUNCTIONING WITHIN PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

The importance of sexual functioning in patients with psychiatric disorders has been discussed previously in this series, and more broadly is recognised as an important domain to assess for overall functioning. Thus, identifying potential psychological factors that may be contributing to sexual dysfunction is important, as it may provide an explanation for the problems the person is experiencing, and perhaps also identify an amenable target for interventions. In addition, as sexual functioning serves as a key indicator of overall functioning, especially in those with mental illnesses where it can serve as an indicator of recovery, addressing any psychological factors that may be contributing to sexual dysfunction is important.

It should be noted at this juncture, that sexual dysfunction and the psychological and physiological factors that can contribute to sexual dysfunction, are all interconnected and thus there is a significant degree of overlap and co‐occurrence between these components. Hence, our separation is purely pragmatic, and in practice, the two sets of factors should be considered jointly. For example, depression and anxiety often co‐occur with physical health conditions such as obesity, 4 and any one of a number of individual factors related to these conditions can cause, or be caused by, sexual dysfunction. In reality, a combination of factors is likely to have contributed to these problems and many of these will have a bidirectional causal relationship between sexual dysfunction and mental health. Thus, taking a holistic approach when assessing sexual functioning is critical.

4. GENERAL PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTORS THAT CONTRIBUTE TO SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION

When assessing psychological factors that can contribute to sexual dysfunction, it is important to bear in mind that these factors are not necessarily and specifically related to sexual dysfunction per se, but that they can negatively impact functioning more generally. Thus, the psychological factors that need to be assessed during a routine psychiatric assessment remain largely the same. In addition, it is their potential impact on the domain of sexual functioning that needs to be given further consideration. Note, this is alongside their impact on other domains of functioning such as an individual's occupation, and relationships (discussed in previous Quip—‘Assessing sexual dysfunction in clinical practice’).

To exemplify the bidirectional relationship between sexual functioning and psychological factors, consider the observation that healthy sexual functioning usually alleviates stress, but that sexual dysfunction can also lead to psychological problems. Thus, many mental illnesses are associated with dysfunction across a variety of sexual domains. Further, once stress has produced sexual dysfunction, this can itself lead to further stress exacerbating the problems the individual is already experiencing.

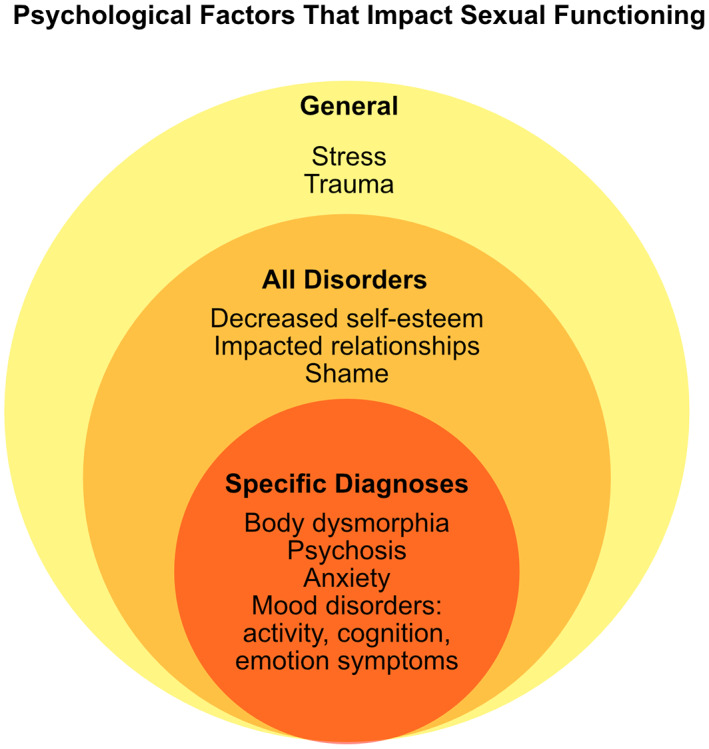

Trauma, is another significant psychological factor which is increasingly assessed in routine clinical practice. This encompasses various forms of childhood abuse and neglect (sexual, physical, and emotional) and traumatic events experienced in adulthood (see Figure 2). The impact of trauma on domains of functioning (education, occupation, social) is also often assessed in clinical practice; however, its impact on sexual functioning is seldom explored, if at all. It is therefore important to note that trauma can significantly compromise sexual functioning, regardless of the nature and timing of the trauma. In other words, the trauma does not necessarily have to be sexual in nature or have occurred during a critical developmental period for it to have an effect on sexual functioning in an individual. For example, sexual dysfunction is a known symptom in combat veterans with PTSD, 5 and therefore, the contribution of trauma to sexual dysfunction should be considered broadly as possible and explored as a potential target for interventions.

FIGURE 2.

Psychological factors that can impact sexual functioning. This schematic shows the psychological factors which may be present in the general population (yellow), in individuals with any psychiatric disorder (orange), and those that are present in specific disorders (red) such as eating disorders, psychotic disorders, anxiety disorders and mood disorders.

5. PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTORS WITHIN PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

As pointed out earlier, mental illnesses impact a number of key psychological domains that can negatively impact sexual functioning. The most common mental illnesses, such as depression and anxiety, which often co‐occur and occur alongside other disorders, entail a number of overlapping symptoms which negatively impact sexual functioning and wellbeing.

For example, the symptoms of depression can be captured across 3 domains namely, activity, cognition, and emotion (for further detailed explanation, see The ACE Model*). In the domain of activity, the symptoms of fatigue, increased or decreased sleep and weight/appetite, can all impact sexual functioning due to a lack of energy, or impact self‐esteem due to changes in weight that alter self‐image and confidence. In the domain of cognition, impaired attention and concentration and psychomotor changes can interfere with sexual functioning by limiting mental engagement and preventing psychological arousal and stimulation. Finally, symptoms within the domain of emotion, such as anhedonia, feelings of guilt or worthlessness and depressed mood can all reduce or eliminate libido, which is essential for healthy sexual functioning.

A common bedfellow of depression is anxiety, which when excessive can manifest as a disorder. Several symptoms of anxiety disorders overlap with those of depression, and therefore it is not surprising that anxiety can impair sexual functioning. As mentioned above, difficulties in concentration, disturbances in sleep and fatigue can all diminish sexual desire and the ability to engage in sexual behaviours and practices. Furthermore, generalized anxiety may extend to more specific anxiety regarding sexual functioning and performance, and can also cause erectile dysfunction, and anorgasmia in women.

Aside from such specific psychiatric disorders, there are some general symptoms that occur in many mental illnesses and can have a significant impact on sexual functioning, regardless of diagnosis. For example, lowered self‐esteem that stems from having a mental illness along with the stigma and shame that this may confer, can significantly threaten the integrity of one's sense of self. Understandably then, this can constrain the individual's ability to engage in sexual behaviours and practices even solo activities—especially if libido is also diminished or lost altogether. In this way, having a mental illness places an additional strain on romantic relationships and interferes with intimacy, all of which makes it difficult to form and sustain relationships.

6. CONCLUSION

In this brief piece, the psychological factors that can lead to sexual dysfunction in any individual have been outlined, and then building on this, the additional psychological factors that occur within the context of psychiatric disorders have been explored. Importantly, many of these factors are already typically assessed in routine clinical practice, however their impact on sexual function is often overlooked. Furthermore, many of these psychological factors are not necessarily specific to any particular diagnosis, therefore it is important to bear these in mind in all patients. Finally, this relationship is bidirectional, and thus when assessing sexual dysfunction, it is equally important to examine its potential psychological sequelae.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

G.S.M. has received a grant or research support from the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Rotary Health, NSW Health, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, Ramsay Research and Teaching Fund, Elsevier, AstraZeneca, Janssen‐Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka and Servier, and has been a consultant for AstraZeneca, Janssen‐Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka and Servier. E.B. declares no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Sydney, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Sydney agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Endnote

Published in Bipolar Disorders, Vol. 20, 2018.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the united StatesPrevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281(6):537‐544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Laumann EO, Gagnon JH, Michael RT, Michaels S. The Social Organization of Sexuality: Sexual Practices in the United States. University of Chicago Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Metz ME, Epstein NB, McCarthy B. Cognitive‐Behavioral Therapy for Sexual Dysfunction. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Esfahani SB, Pal S. Obesity, mental health, and sexual dysfunction: a critical review. Health Psychology Open. 2018;5(2):2055102918786867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brotto L, Atallah S, Johnson‐Agbakwu C, et al. Psychological and interpersonal dimensions of sexual function and dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2016;13(4):538‐571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.