Abstract

Many researchers have questioned the ability of biota to adapt to rapid anthropogenic environmental shifts. Here, we synthesize emerging genomic evidence for rapid insect evolution in response to human pressure. These new data reveal diverse genomic mechanisms (single locus, polygenic, structural shifts; introgression) underpinning rapid adaptive responses to a variety of anthropogenic selective pressures. While the effects of some human impacts (e.g. pollution; pesticides) have been previously documented, here we highlight startling new evidence for rapid evolutionary responses to additional anthropogenic processes such as deforestation. These recent findings indicate that diverse insect assemblages can indeed respond dynamically to major anthropogenic evolutionary challenges. Our synthesis also emphasizes the critical roles of genomic architecture, standing variation and gene flow in maintaining future adaptive potential. Broadly, it is clear that genomic approaches are essential for predicting, monitoring and responding to ongoing anthropogenic biodiversity shifts in a fast‐changing world.

Keywords: adaptive potential, climatic shifts, deforestation, ecosystem change, genomic architecture, human‐driven evolution, standing genetic variation

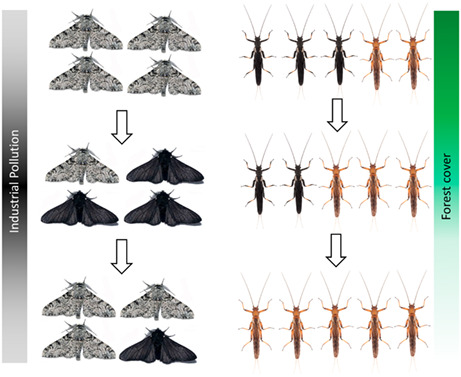

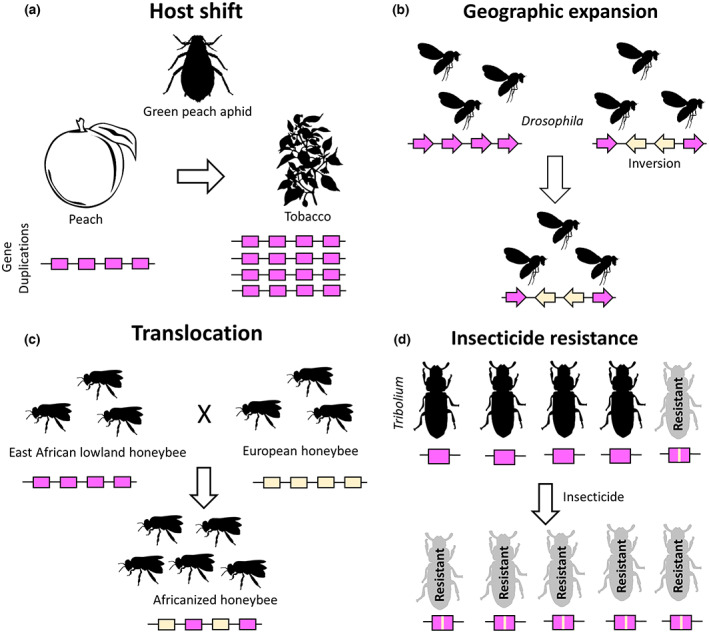

The extent to which wild populations can adapt to anthropogenic environmental change remains largely unknown. In this review, we synthesize emerging genomic evidence for rapid insect evolution in response to human pressure. In addition to exploring the genomic mechanisms underpinning adaptation in well‐known systems (e.g. colour shifts in response to pollution in peppered moths; left) we highlight startling new evidence for rapid evolutionary responses to additional anthropogenic processes (e.g. colour shifts in response to deforestation in stoneflies; right).

1. INTRODUCTION

Under the fast‐changing conditions of the Anthropocene (Lewis & Maslin, 2015), many species lacking phenotypic plasticity must adapt, disperse or else potentially face extinction (Berg et al., 2010; Halsch et al., 2021). However, the extent to which wild populations may be able to adapt to their rapidly shifting environments remains an outstanding question for much of the planet's biodiversity (Catullo et al., 2019; Hendry et al., 2017; McGill et al., 2015; Sih et al., 2011). For instance, while recent temporal surveys appear to indicate that diverse insect assemblages are suffering substantial declines across many regions of the globe (e.g. Baranov et al., 2020; Hallmann et al., 2017; Thomas et al., 2019; Wagner, 2020, but see van Klink et al., 2022), relatively little is known about their adaptive capacity (see Table 1 for glossary of terms). This dearth of knowledge is particularly concerning given that insects comprise such a vast proportion of the earth's biodiversity (Stork, 2018).

TABLE 1.

Glossary of terms

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Adaptive potential | The capacity of a population to respond to changing selection pressures |

| Adaptive shift | An evolutionary change in a population due to natural selection. |

| Convergent evolution | The independent evolution of similar phenotypes in unrelated lineages, typically via distinct genetic mutations |

| De novo mutation | A new mutation in the genome that was not inherited from a parent |

| Genomic architecture | The arrangement of functional elements (e.g. genes and regulatory regions) in the genome |

| Genomic islands of differentiation | Small regions of the genome that are tightly associated with adaptation, and resistant to gene flow |

| Inversion | A structural variant that involves a segment of a chromosome breaking off and reattaching in the reverse direction |

| Parallel evolution | The independent evolution of similar traits in related lineages |

| Polygenic | A trait controlled by two or more genes |

| Reverse evolution | The reacquisition of a phenotypic trait by a population or species after it has been lost |

| Standing genetic variation | Pre‐existing genetic variation within a population |

| Structural variation | Major variations in chromosomal structure, including deletions, duplications, insertions, and inversions |

| Transposable element | A ‘mobile’ sequence of DNA that can move to different locations within a genome |

Prior to the molecular revolution, our understanding of evolution in wild populations rested heavily on phenotypic analyses of a handful of well‐studied species (e.g. Cain & Sheppard, 1954; Clarke et al., 1985; Daday, 1954; Kettlewell, 1973). By contrast, the recent application of genomic approaches is now enabling researchers to revisit long‐standing hypotheses of human‐driven adaptive shifts (e.g. Van't Hof et al., 2016). Building on classic phenotypic studies, recent genomic analyses are now beginning to illuminate new cases of rapid insect adaptation in response to large‐scale human impacts such as deforestation, translocation and climate change.

While numerous researchers have questioned the adaptive capability of natural populations (Davis et al., 2005; Nogués‐Bravo et al., 2018), recent genomic studies are revealing startling evidence for rapid adaptation over ecologically relevant timeframes in response to global change issues such as deforestation and translocation. Here we synthesize genomic insights emerging from diverse systems, including genetic studies of both ‘natural’ and ‘pest’ insect populations, to highlight strong evidence for rapid evolution in response to human pressure. In particular, we highlight emerging evidence of rapid evolution in response to deforestation and other previously little‐studied anthropogenic pressures, focussing particularly on the most recent studies. While it is not our intention to provide an exhaustive review of the myriad studies of insect evolution, we point interested readers to several helpful recent reviews (e.g. Garnas, 2018; Hoffmann, 2017; Pélissié et al., 2018).

2. JUMPING GENES AND ADAPTIVE RESPONSES TO POLLUTION

The classic case of shifting frequencies of British peppered‐moth (Biston betularia) phenotypes (Clarke et al., 1985; Cook & Saccheri, 2013; Kettlewell, 1973) during the industrial revolution continues to represent the most widely‐known example of anthropogenic evolution (Figure 1). A recent genomic analysis concluded that the black phenotype which emerged in the mid 19th century (in response to industrial pollution) is underpinned by a transposable element inserted in the intron of the gene cortex (Van't Hof et al., 2016). Statistical analysis of recombined haplotypes suggests that this insertion occurred around 1820 (Van't Hof et al., 2016), consistent with historical records which indicate melanic moths were first identified in 1848 (Kettlewell, 1973). This research thus provides a novel example of the increasingly recognized role of jumping genes in mediating rapid adaptive shifts in wild insect populations (Gilbert et al., 2021; Schrader et al., 2014; Woronik et al., 2019).

FIGURE 1.

Human‐driven shifts in insect colouration. The recently‐evolved melanic morph of the peppered moth Biston, controlled by a transposable element in the intron of cortex (van't Hof et al., 2016), was selectively favoured by industrial pollution (Kettlewell, 1973), but has since declined in frequency (Clarke et al., 1985). Dark morphs of New Zealand Zelandoperla, underpinned by a mutation in the insect melanism gene ebony (Foster et al., 2022), mimic the noxious, forest‐dwelling stonefly Austroperla (Foster, McCulloch, & Waters, 2021; McLellan, 1997, 1999). We hypothesize that anthropogenic deforestation has driven widespread reductions in both the abundance of Austroperla and the frequency of melanic Zelandoperla mimics (see Foster et al., 2022).

Ideally, studies inferring evolutionary change in response to anthropogenic environmental gradients should be replicated, either geographically (within species) or phylogenetically (across species) (Johnson et al., 2018; Majerus, 1998; Santangelo et al., 2018), to help account for potential alternative non‐adaptive explanations such as drift. In the case of moths, similar phenotypic shifts linked to pollution have been observed in more than 100 additional species across Britain (Kettlewell, 1973), with recent research suggesting that mutations in the cortex gene may underpin melanism in at least two of these species (Van't Hof et al., 2019). However, linkage analysis indicates the mutation causing melanism in these two species likely arose prior to the industrial revolution, suggesting the rapid phenotypic shifts in these species were the result of selection on standing genetic variation, rather than via more recent de novo mutations (Van't Hof et al., 2019). These results illustrate how seemingly similar phenotypic shifts may be underpinned by distinct genomic mechanisms.

3. ADAPTING TO DEFORESTATION

Globally, deforestation has led to the fragmentation of countless natural populations (Alberti, 2015; Hanski et al., 2007; Karlsson & Van Dyck, 2005), and thus represents a highly replicated natural experiment (Vitousek et al., 1997). Remarkably little is known, however, about the evolutionary impacts of this forest loss (Foster, McCulloch, Ingram, et al., 2021; Willi & Hoffmann, 2012). Polymorphic taxa provide ideal models for testing the role of widespread deforestation in driving rapid and repeated evolutionary change in wild populations. Here we highlight new evidence emerging from comparative analyses of polymorphic insects in New Zealand, which together reveal the dramatic evolutionary effects of deforestation.

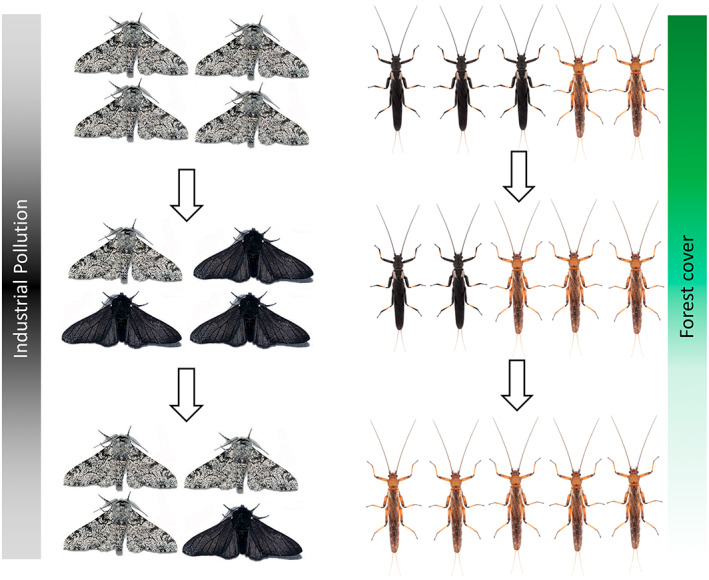

Recent analyses of New Zealand stonefly (Plecoptera) populations have revealed sharp clines in flight loss with increasing elevation, typically delineated by the alpine treeline (Figure 2; Foster, McCulloch, Ingram, et al., 2021; McCulloch, Foster, Dutoit, et al., 2019; McCulloch, Foster, Ingram, et al., 2019). These data support Darwin's long‐standing hypothesis that insects in wind‐exposed ‘insular’ habitats evolve flight loss to maintain local recruitment (Darwin, 1859, see also Leihy & Chown, 2020). These findings echo montane flight loss events detected across many regions of the globe (e.g. Hendrickx et al., 2015; Suzuki et al., 2019). In the case of Zelandoperla, genomic analyses have revealed genome‐wide divergence among alpine/lowland ecotype pairs across different mountain ranges, with this divergence potentially underpinned by mutations in the developmental supergene doublesex (McCulloch et al., 2021). By contrast, full‐winged and wing‐reduced ecotype pairs in some heavily deforested subalpine regions of New Zealand show no such genome‐wide divergence (Figure 2), implying that wing reduction has evolved only in recent centuries (Foster, McCulloch, Ingram, et al., 2021), likely in response to anthropogenic deforestation soon after human arrival 750 years ago (McWethy et al., 2010). These data highlight the potential for rapid insect evolution in response to environmental shifts over ecologically relevant timeframes. Future genomic analyses promise to shed additional light on the parallel versus convergent origins of wing reduction across these recently deforested subalpine regions, and the potential capacity for reacquisition of flight in reforested regions.

FIGURE 2.

Anthropogenic shifts in elevational wing‐reduction clines in subalpine Zelandoperla stoneflies. While flight loss is a widespread adaptation to New Zealand's alpine conditions (e.g. western South Island; a), recent deforestation has selected for flightless ecotypes also in many subalpine habitats (yellow; b, c) (McCulloch et al., 2021; McCulloch, Foster, Dutoit, et al., 2019). Wing reduction clines are consistently linked to the alpine treeline (Foster, McCulloch, Ingram, et al., 2021), but occur at lower elevations in recently deforested regions (b), suggesting shifts in ecotype distribution in response to exposure (see also Darwin, 1859; Leihy & Chown, 2020). While flighted and flightless lineages in alpine regions show genome‐wide divergence predating human impacts (a, b), the absence of such ecotype divergence in recently deforested subalpine habitats (c) suggests that flight loss in these regions is entirely anthropogenic (Foster, McCulloch, Ingram, et al., 2021; McCulloch et al., 2021).

In addition to the increased fragmentation and exposure experienced by populations in deforested habitats (see above), associated shifts in community composition are predicted to alter the evolutionary dynamics of surviving taxa. This possibility is highlighted by a melanic polymorphism in Zelandoperla stoneflies (Figure 1) that underpins Batesian mimicry of an unrelated, noxious stonefly Austroperla (Foster et al., 2022; McLellan, 1997, 1999). Specifically, melanic mimics of the aposematic ‘model’ have high frequencies in forested habitats of southern New Zealand where Austroperla is abundant (Foster et al., 2022), but low frequencies in deforested habitats (where Austroperla is rare; Nyström et al., 2003). Genomic analyses reveal that this colour‐polymorphism variation is controlled by the well‐known insect melanism gene ebony (Wittkopp et al., 2002), and is likely maintained by frequency‐dependent selection linked to variation in model abundance (Foster et al., 2022). Given the context of recent deforestation in New Zealand (McWethy et al., 2010), this system may thus present an evolutionary parallel to the peppered moth (Kettlewell, 1973; Van't Hof et al., 2016, 2019) as a ‘textbook case’ of rapid human‐driven evolution in insect melanism (Figure 1).

4. ADAPTING TO CLIMATIC SHIFTS

Under rapid anthropogenic climate change, numerous insect populations will be forced to shift or adapt (Halsch et al., 2021). Indeed, climate change has already caused significant distributional shifts across a range of insect species (Parmesan, 2006; Sánchez‐Guillén et al., 2013), which in some cases has resulted in rapid adaptation (Sánchez‐Guillén et al., 2016). For example, the recent climate‐induced range expansion of the blue‐tailed damselfly across Sweden has led to significant physiological shifts in populations at the leading edge of the range expansion (Lancaster et al., 2015, 2016). Recent genomic analyses indicate that these shifts may be linked to positive selection on heat shock proteins, which are typically involved in coping with thermal stress (Dudaniec et al., 2018).

Migration represents a key adaptation facilitating response to environmental change, and anthropogenic pressures are thus expected to select for shifts in dispersal and migratory behaviour in numerous insect taxa. Along these lines, recent genomic analyses have revealed substantial genetic components underpinning intraspecific variation in insect dispersal and migratory behaviour (e.g. Li et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2014). In the case of monarch butterflies, for instance, genome‐wide scans have revealed numerous candidate loci potentially associated with migratory differentiation (Merlin et al., 2020; Zhan et al., 2014). Ideally, temporal genomic analyses are required to test for human‐driven shifts in genotypes at these dispersal loci.

Similar climate‐induced elevational range shifts have been detected in a range of insect species (McCain & Garfinkel, 2021). However, in the case of many geographically restricted alpine lineages, there are few if any options for dispersal, meaning that species that cannot adapt to warming temperatures are likely to face extinction (Giersch et al., 2017; Hotaling et al., 2017; Kinzner et al., 2019). However, such climatic shifts also have potential to drive rapid adaptive change and genetic restructuring of surviving upland insect lineages (Shah et al., 2020).

Climate change may also drive dramatic shifts in insect phenology (Forrest, 2016). Phytophagous insects may be particularly impacted, as environmental shifts often alter the growing seasons of their host plants (Hamann et al., 2021). Such climate‐induced phenological shifts are believed to have a strong genetic basis (Bradshaw & Holzapfel, 2001; van Asch et al., 2007, 2013), although the precise genomic mechanisms underpinning some of these changes have yet to be identified. Crucially, recent analyses of environmental clines are starting to uncover the genomic architecture underpinning climate‐induced differences in diapause timing across a range of insect species (Marshall et al., 2020). In some cases, differentiation in diapause timing appears to be primarily controlled by only a few loci of large effect (Kozak et al., 2019; Paolucci et al., 2016), while in other cases, shifts in phenology appear to be polygenic, involving numerous loci with additive effects (Pruisscher et al., 2018). Future temporal genomic studies (e.g. involving insect samples collected across several decades) will allow researchers to better understand the capacity of insects to undergo rapid phenological shifts in response to global climatic change.

5. ADAPTING TO NEW ECOSYSTEMS

Insect lineages anthropogenically introduced into new regions and ecosystems are typically exposed to novel selective regimes, and hence often show strong genomic signatures of rapid evolutionary change. Such anthropogenic processes are particularly highlighted by emerging data regarding repeated loss of song in cricket lineages following their translocation to Hawaii (Pascoal et al., 2014, 2020; Zuk et al., 2006). These ‘silent’ lineages have evolved in response to novel parasitic threats in the species' introduced range, with newly emerged ‘flatwing’ mutations reaching fixation in 20 or fewer generations (Rayner et al., 2019). Genomic analyses indicate that ‘flatwing’ mutations cause extensive genome‐wide effects on embryonic gene expression, leading to male crickets expressing feminized chemical hormones (Pascoal et al., 2020). Intriguingly, recent analyses indicate that convergent evolutionary processes underpin these rapid phenotypic shifts across independent island populations (Zhang et al., 2021).

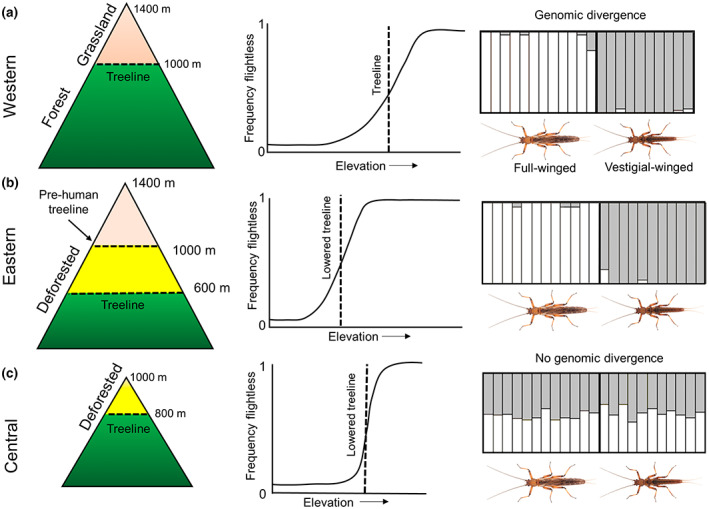

The recent emergence of ‘Africanized’ honeybees (Figure 3) across the Americas likewise emphasizes the rapid rate at which anthropogenically introduced populations can evolve. These behaviourally distinctive bee lineages emerged as a result of the accidental release of an African subspecies in Brazil in 1965, and resultant hybridization with local European‐derived populations (Whitfield et al., 2006). The admixed lineages subsequently spread rapidly across the Americas, evolving several traits apparently underpinning their success, including increased aggression, elevated reproductive rates, higher tolerances to pesticides, and lower susceptibility to Varroa mites (Calfee et al., 2020). Molecular analyses have linked these distinctive adaptations to multiple regions of the genome (Zayed & Whitfield, 2008), with strong selection for genes of African ancestry in some portions of the genome, and for European markers in others (Calfee et al., 2020). Notably, particularly strong selection is evident in a large, gene‐rich region implicated in reproductive traits and foraging behaviours of worker bees (Nelson et al., 2017), and in the gene AmDOP3 gene, which is implicated in hygiene behaviours (Mikheyev et al., 2015).

FIGURE 3.

Diverse cases of human‐driven evolutionary change in insect populations are underpinned by a variety of biological and genomic causes. (a) Recent evolution of tobacco‐feeding aphid lineages was underpinned by gene duplications leading to overexpression of cytochrome P450 genes required for nicotine detoxification (Bass et al., 2013; Singh et al., 2020). (b) Range extension of Drosophila lineages has been facilitated by inversion polymorphisms that maintain coadapted loci, facilitating rapid adaptation to novel conditions (Kapun et al., 2016; Rane et al., 2015). (c) Admixed ‘Africanized’ bees spread rapidly across the Americas, with rapid behavioural shifts apparently facilitated by the diverse genetic backgrounds provided by hybridization between parental African and European lineages (Calfee et al., 2020). (d) Overuse of insecticides leads to the rapid development of insecticide‐resistant populations, underpinned by single point mutations in key metabolic genes (e.g. Schlipalius et al., 2012).

Intriguingly, the subsequent introduction of ‘Africanized’ bees to Puerto Rico in 1994 resulted in further rapid evolution. Within 12 generations, the introduced lineages had undergone drastic reversals in aggression (e.g. ‘gentle Africanized’ honeybees; Rivera‐Marchand et al., 2012). Recent studies indicate that these rapid behavioural shifts are correlated with strong genomic signatures of selection across multiple distinct loci and regions (Avalos et al., 2017), illustrating how admixture can fuel adaptive shifts by providing diverse genetic backgrounds for selection. Behavioural shifts have also been detected in invasive ant populations in the USA, with evidence of positive selection on genes controlling neurological functions and caste determination (Privman et al., 2018). These studies illustrate the strong selective pressure on sociobiological traits in invasive social insects (Privman et al., 2018).

Evidence of local adaptation has similarly been reported for invasive populations of small hive beetles that parasitize bee nests worldwide (Liu et al., 2021), melon fly (Dupuis et al., 2018), and invasive Drosophila populations in Hawaii (Koch et al., 2020). In each of these cases, adaptive signatures have been found across the genome, further illustrating how responses to sudden changes in selection regimes can be polygenic. The detection of phenotypic and/or genetic clines in widespread Drosophila lineages also illustrate the role of natural selection across many regions, and extensive genomic data are now shedding new light on the rapid evolution of this diversity (Adrion et al., 2015). In some cases, such clines have evolved within decades of establishment of Drosophila taxa in new regions (e.g. Hoffmann & Weeks, 2007; Telonis‐Scott et al., 2011). In many cases, this adaptation to climatic conditions is apparently underpinned by inversion polymorphisms (Rane et al., 2015, Kapun et al., 2016; Figure 3). Such inversions may be key in facilitating local adaptation, as they are resistant to recombination, and thus prevent the breakup of favourable genomically linked gene complexes (Wellenreuther & Bernatchez, 2018).

Invasive insects can also potentially drive rapid evolutionary shifts in native insects, by increasing competition, or by altering community structure (Fortuna et al., 2022). Similarly, invasive plants can lead to host‐shifts, and associated adaptation (Bush, 1969, Carroll et al., 1997; see below). Introductions of new pest and weed species continue at unprecedented rates (Seebens et al., 2017), and thus it is crucial that future genomic studies examine the evolutionary responses of native taxa to such invasive lineages.

6. ADAPTING TO NEW HOST PLANTS

Adaptation to novel host plants has long been considered a key driver of insect diversification (Nosil, 2007; Walsh, 1861). It is becoming increasingly evident that adaptation following host shifts can occur over ecological time‐scales (Forbes et al., 2017), and studies are now beginning to uncover the genomic basis of this rapid adaptation (e.g. Hood et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2020). One iconic example of rapid adaptation to new host plants is the shift of apple maggot (Rhagoletis pomonella) from its native hawthorn to the introduced domesticated apple fewer than 200 years ago (Bush, 1969). This shift has resulted in significant changes in diapause timing—with apple feeding Rhagoletis flies eclosing about a month earlier than those feeding on hawthorn—and has led to the development of partially reproductively isolated host races (Hood et al., 2020; Inskeep et al., 2021). Recent studies indicate that the changes in diapause timing are driven by selection on standing genetic variation across the entire genome (Doellman et al., 2019; Dowle et al., 2020).

Laboratory experiments suggest that the genetic changes associated with host plant adaptation may be largely predictable, with independently derived experimental Rhagolestis colonies fed on apples displaying parallel genomic shifts (Egan et al., 2015). Parallel genomic shifts have likewise been observed in Melissa Blue butterflies that have independently colonised alfalfa in different parts of North America (Chaturvedi et al., 2018). Most of the mutations associated with these shifts were on the Z chromosome, suggesting a disproportionate role of sex chromosomes in the adaptation of this species (Chaturvedi et al., 2018).

Another well studied example of rapid adaptation is the evolution a tobacco‐feeding host race of the green peach aphid, which evolved during the 16th century after tobacco was introduced to the Old World (Bass et al., 2013; Figure 3). The tobacco‐feeding host race overexpresses a number of cytochrome P450 genes, resulting in increased expression of the enzyme that detoxifies nicotine (Bass et al., 2013; Puinean et al., 2010). These overexpressed genes are genomically closely linked—suggesting they may be co‐regulated—with recent analyses demonstrating that a large region of the genome containing these genes has been extensively duplicated in the tobacco‐feeding host race (Singh et al., 2020; Figure 3).

7. EVOLUTION OF INSECTICIDE RESISTANCE

Perhaps the best‐studied example of anthropogenic evolution in insects involves the development of insecticide resistance (Ffrench‐Constant, 2013; Hawkins et al., 2019; Liu, 2015). As pesticides apply extremely strong selection pressures, insecticide resistance can evolve rapidly (e.g. within a few years of initial exposure; Gassmann et al., 2014), and the frequencies of resistant lineages can increase significantly within only a few generations (Clements et al., 2017).

Pesticide resistance often stems from a single mutation of large effect (Schlipalius et al., 2012), whereas in some cases resistance can have a polygenic basis (Fournier‐Level et al., 2019). Recent research suggests that a range of different genomic mechanisms can underpin insecticide resistance (Hawkins et al., 2019). Although resistance is most typically caused by single point mutations (e.g. Schlipalius et al., 2012), there is growing evidence that deletions (e.g. Baxter et al., 2011), gene duplications (e.g. Riveron et al., 2013), and inversions (e.g. Ayala et al., 2014) can all play significant roles in its evolution, with a wide variety of genomic mechanisms implicated (Bass et al., 2014; Liu, 2015).

Mutations underpinning resistance typically evolve after the introduction of the pesticide (Hawkins et al., 2019), with multiple independent de novo mutations sometimes facilitating repeated evolution of resistance within single species (Schlipalius et al., 2012). By contrast, in some cases resistance can evolve via repeated selection on ancestral standing genetic variation that predates pesticide application (Troczka et al., 2012). For instance, recent genomic scans of the Colorado Potato beetle demonstrate that pesticide resistance has evolved independently from standing variation across different agricultural regions, often involving similar genetic pathways, but distinct genes in different areas (Pélissié et al., 2022). Insecticide resistance may also evolve through adaptive introgression (Clarkson et al., 2014; Hawkins et al., 2019). As a case in point, Anopheles coluzzii mosquitoes inherited a genomic island of differentiation that includes a number of insecticide resistance genes through hybridization with Anopheles gambiae (Norris et al., 2015).

8. GENOMIC ARCHITECTURE OF ANTHROPOGENIC EVOLUTION: PREDICTING FUTURE ADAPTIVE POTENTIAL

What are the key genomic determinants of adaptive potential? Characterising the genomic bases of rapid adaptive shifts represents a key challenge for predicting future adaptive capacity in wild populations. Recent data increasingly highlight the role of standing variation as an enabler of such repeated and predictable evolutionary shifts (Pélissié et al., 2022). Indeed, genomic architecture in many cases can essentially ‘pre‐adapt’ populations for future change by allowing for the maintenance of standing variation underpinning distinct ecotypes at co‐adapted loci (e.g. ‘precast bricks’; Ayala et al., 2010; Love et al., 2016; Mérot et al., 2018; Wellenreuther & Bernatchez, 2018).

A variety of genomic mechanism may potentially facilitate rapid adaptive shifts. For instance, several recent examples of rapid insect adaptation involve the insertion/deletion of mobile genetic elements (e.g. Gilbert et al., 2021; Van't Hof et al., 2016; Woronik et al., 2019). Such straightforward and fast‐acting genetic mechanisms seem ideally suited for facilitating flexible and rapid evolutionary change. Intriguingly, a few recent studies of anthropogenic evolution point to the rapid accumulation of independent de novo shifts in distinct populations (Zhang et al., 2021), sometimes involving multiple parts of the genome, with diverse loci implicated (e.g. Doellman et al., 2019; Dowle et al., 2020).

While genomic data are transforming our appreciation of anthropogenic evolution, crucial questions remain regarding the potential ‘reversibility’ of such evolutionary shifts, and the downstream implications of anthropogenic change. While some categories of evolutionary reversal have previously been considered essentially impossible (Dollo, 1893; Trueman et al., 2004), researchers are increasingly questioning this assumption (e.g. Bank & Bradler, 2022). In this regard, the roles of genetic architecture in preserving adaptive capacity, and of gene flow in spreading adaptive alleles among lineages, may be particularly important (e.g. Waters & McCulloch, 2021). Indeed, in cases where standing variation represents a major source of adaptive potential, and gene flow among populations is high (e.g. Waters & McCulloch, 2021), there should be considerable capacity for future reversals of recent evolutionary shifts (e.g. declines in insect melanism with decreasing pollution; Clarke et al., 1985, or increased frequencies of insect melanism/flight in response to reforestation; Foster, McCulloch, Ingram, et al., 2021, Foster et al., 2022). Alternatively, when gene flow among populations is low, and selection/drift have reduced standing variation (e.g. complete loss of ancestral phenotypes/genotypes; Zhang et al., 2021), there may be limited opportunities for such future adaptation. Indeed, in some cases anthropogenic evolution (e.g. flight loss; Foster, McCulloch, Ingram, et al., 2021) may lead to population isolation, decreased effective population size and an increase in extinction risk (Waters et al., 2020). In the case of recently silenced crickets (Zhang et al., 2021), for instance, anti‐parasite adaptations for immediate fitness may potentially lead to reduced reproductive success and heightened risks of population extinction in the longer term.

9. CONCLUSIONS

Many researchers have questioned the ability of natural populations to adapt in the face of fast‐changing environmental conditions. Here, we highlight abundant new evidence for rapid adaptation in response to multiple anthropogenic pressures. These emerging data reveal diverse genomic mechanisms (single locus, polygenic, structural shifts; introgression) underpinning rapid adaptive responses to myriad human‐driven selective gradients. In addition to previous studies of the evolutionary effects of pollution and pesticides, recent genomic data reveal dramatic adaptive responses to translocation, climate change and even deforestation—a globally pervasive but previously little‐studied driver of insect evolution. These new emerging data thus highlight the need to better understand the evolutionary effects of broader ranges of anthropogenic pressures. Our synthesis emphasizes the key roles of genomic architecture, standing variation and gene flow in maintaining adaptive potential and pre‐empting future evolutionary challenges. Knowledge of such genomic diversity is essential for understanding and predicting ongoing anthropogenic evolutionary change in a fast‐changing world.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This research was supported by Marsden contract UOO2016 (Royal Society of New Zealand). Open access publishing facilitated by University of Otago, as part of the Wiley ‐ University of Otago agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

McCulloch, G. A. , & Waters, J. M. (2023). Rapid adaptation in a fast‐changing world: Emerging insights from insect genomics. Global Change Biology, 29, 943–954. 10.1111/gcb.16512

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- Adrion, J. R. , Hahn, M. W. , & Cooper, B. S. (2015). Revisiting classic clines in Drosophila melanogaster in the age of genomics. Trends in Genetics, 31, 434–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, M. (2015). Eco‐evolutionary dynamics in an urbanizing planet. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 30, 114–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avalos, A. , Pan, H. , Li, C. , Acevedo‐Gonzalez, J. P. , Rendon, G. , Fields, C. J. , Brown, P. J. , Giray, T. , Robinson, G. E. , & Hudson, M. E. (2017). A soft selective sweep during rapid evolution of gentle behaviour in an Africanized honeybee. Nature Communications, 8, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala, D. , Fontaine, M. C. , Cohuet, A. , Fontenille, D. , Vitalis, R. , & Simard, F. (2010). Chromosomal inversions, natural selection and adaptation in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus . Molecular Biology and Evolution, 28, 745–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala, D. , Ullastres, A. , & González, J. (2014). Adaptation through chromosomal inversions in anopheles . Frontiers in Genetics, 5, 129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bank, S. , & Bradler, S. (2022). A second view on the evolution of flight in stick and leaf insects (Phasmatodea). BMC Ecology and Evolution, 22, 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranov, V. , Jourdan, J. , Pilotto, F. , Wagner, R. , & Haase, P. (2020). Complex and nonlinear climate‐driven changes in freshwater insect communities over 42 years. Conservation Biology, 34, 1241–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass, C. , Puinean, A. M. , Zimmer, C. T. , Denholm, I. , Field, L. M. , Foster, S. P. , Gutbrod, O. , Nauen, R. , Slater, R. , & Williamson, M. S. (2014). The evolution of insecticide resistance in the peach potato aphid, Myzus persicae . Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 51, 41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass, C. , Zimmer, C. T. , Riveron, J. M. , Wilding, C. S. , Wondji, C. S. , Kaussmann, M. , Field, L. M. , Williamson, M. S. , & Nauen, R. (2013). Gene amplification and microsatellite polymorphism underlie a recent insect host shift. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110, 19460–19465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, S. W. , Badenes‐Pérez, F. R. , Morrison, A. , Vogel, H. , Crickmore, N. , Kain, W. , Wang, P. , Heckel, D. G. , & Jiggins, C. D. (2011). Parallel evolution of bacillus thuringiensis toxin resistance in Lepidoptera. Genetics, 189, 675–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg, M. P. , Kiers, E. T. , Driessen, G. , Van Der Heijden, M. , Kooi, B. W. , Kuenen, F. , Liefting, M. , Verhoef, H. A. , & Ellers, J. (2010). Adapt or disperse: Understanding species persistence in a changing world. Global Change Biology, 16, 587–598. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, W. E. , & Holzapfel, C. M. (2001). Genetic shift in photoperiodic response correlated with global warming. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 98, 14509–14511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush, G. L. (1969). Sympatric host race formation and speciation in frugivorous flies of the genus Rhagoletis (Diptera, Tephritidae). Evolution, 23, 237–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain, A. J. , & Sheppard, P. M. (1954). Natural selection in Cepaea . Genetics, 39, 89–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calfee, E. , Agra, M. N. , Palacio, M. A. , Ramírez, S. R. , & Coop, G. (2020). Selection and hybridization shaped the rapid spread of African honey bee ancestry in the Americas. PLoS Genetics, 16, e1009038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, S. P. , Dingle, H. , & Klassen, S. P. (1997). Genetic differentiation of fitness‐associated traits among rapidly evolving populations of the soapberry bug. Evolution, 51, 1182–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catullo, R. A. , Llewelyn, J. , Phillips, B. L. , & Moritz, C. C. (2019). The potential for rapid evolution under anthropogenic climate change. Current Biology, 29, R996–R1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi, S. , Lucas, L. K. , Nice, C. C. , Fordyce, J. A. , Forister, M. L. , & Gompert, Z. (2018). The predictability of genomic changes underlying a recent host shift in Melissa blue butterflies. Molecular Ecology, 27, 2651–2666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, C. A. , Mani, G. , & Wynne, G. (1985). Evolution in reverse: Clean air and the peppered moth. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 26, 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, C. S. , Weetman, D. , Essandoh, J. , Yawson, A. E. , Maslen, G. , Manske, M. , Field, S. G. , Webster, M. , Antão, T. , & MacInnis, B. (2014). Adaptive introgression between anopheles sibling species eliminates a major genomic Island but not reproductive isolation. Nature Communications, 5, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements, J. , Schoville, S. , Clements, N. , Chapman, S. , & Groves, R. L. (2017). Temporal patterns of imidacloprid resistance throughout a growing season in Leptinotarsa decemlineata populations. Pest Management Science, 73, 641–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook, L. , & Saccheri, I. (2013). The peppered moth and industrial melanism: Evolution of a natural selection case study. Heredity, 110, 207–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daday, H. (1954). Gene frequencies in wild populations of Trifolium repens . Heredity, 8, 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, C. (1859). On the origin of the species by natural selection. John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M. B. , Shaw, R. G. , & Etterson, J. R. (2005). Evolutionary responses to changing climate. Ecology, 86, 1704–1714. [Google Scholar]

- Doellman, M. M. , Egan, S. P. , Ragland, G. J. , Meyers, P. J. , Hood, G. R. , Powell, T. H. , Lazorchak, P. , Hahn, D. A. , Berlocher, S. H. , & Nosil, P. (2019). Standing geographic variation in eclosion time and the genomics of host race formation in Rhagoletis pomonella fruit flies. Ecology and Evolution, 9, 393–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollo, L. (1893). The laws of evolution. Bulletin de la Société belge de géologie, de paléontologie et d'hydrologie, 7, 164–166. [Google Scholar]

- Dowle, E. J. , Powell, T. H. , Doellman, M. M. , Meyers, P. J. , Calvert, M. B. , Walden, K. K. , Robertson, H. M. , Berlocher, S. H. , Feder, J. L. , & Hahn, D. A. (2020). Genome‐wide variation and transcriptional changes in diverse developmental processes underlie the rapid evolution of seasonal adaptation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117, 23960–23969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudaniec, R. Y. , Yong, C. J. , Lancaster, L. T. , Svensson, E. I. , & Hansson, B. (2018). Signatures of local adaptation along environmental gradients in a range‐expanding damselfly (Ischnura elegans). Molecular Ecology, 27, 2576–2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis, J. R. , Sim, S. B. , San Jose, M. , Leblanc, L. , Hoassain, M. A. , Rubinoff, D. , & Geib, S. M. (2018). Population genomics and comparisons of selective signatures in two invasions of melon fly, Bactrocera cucurbitae (Diptera: Tephritidae). Biological Invasions, 20, 1211–1228. [Google Scholar]

- Egan, S. P. , Ragland, G. J. , Assour, L. , Powell, T. H. , Hood, G. R. , Emrich, S. , Nosil, P. , & Feder, J. L. (2015). Experimental evidence of genome‐wide impact of ecological selection during early stages of speciation‐with‐gene‐flow. Ecology Letters, 18, 817–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ffrench‐Constant, R. H. (2013). The molecular genetics of insecticide resistance. Genetics, 194, 807–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, A. A. , Devine, S. N. , Hippee, A. C. , Tvedte, E. S. , Ward, A. K. , Widmayer, H. A. , & Wilson, C. J. (2017). Revisiting the particular role of host shifts in initiating insect speciation. Evolution, 71, 1126–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest, J. R. (2016). Complex responses of insect phenology to climate change. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 17, 49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortuna, T. M. , Le Gall, P. , Mezdour, S. , & Calatayud, P.‐A. (2022). Impact of invasive insects on native insect communities. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 51, 100904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster, B. J. , McCulloch, G. A. , Foster, Y. , Kroos, G. C. , & Waters, J. M. (2022). Ebony underpins Batesian mimicry polymorphism in melanic insects. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2022.06.13.495778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster, B. J. , McCulloch, G. A. , Ingram, T. , Vogel, M. , & Waters, J. M. (2021). Anthropogenic evolution in an insect wing polymorphism following widespread deforestation. Biology Letters, 17, 20210069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster, B. J. , McCulloch, G. A. , & Waters, J. M. (2021). Evidence for aposematism in a southern hemisphere stonefly family (Plecoptera: Austroperlidae). Austral Entomology, 60, 267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier‐Level, A. , Good, R. T. , Wilcox, S. A. , Rane, R. V. , Schiffer, M. , Chen, W. , Battlay, P. , Perry, T. , Batterham, P. , & Hoffmann, A. A. (2019). The spread of resistance to imidacloprid is restricted by thermotolerance in natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster . Nature Ecology and Evolution, 3, 647–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnas, J. R. (2018). Rapid evolution of insects to global environmental change: Conceptual issues and empirical gaps. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 29, 93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassmann, A. J. , Petzold‐Maxwell, J. L. , Clifton, E. H. , Dunbar, M. W. , Hoffmann, A. M. , Ingber, D. A. , & Keweshan, R. S. (2014). Field‐evolved resistance by western corn rootworm to multiple bacillus thuringiensis toxins in transgenic maize. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111, 5141–5146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giersch, J. J. , Hotaling, S. , Kovach, R. P. , Jones, L. A. , & Muhlfeld, C. C. (2017). Climate‐induced glacier and snow loss imperils alpine stream insects. Global Change Biology, 23, 2577–2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, C. , Peccoud, J. , & Cordaux, R. (2021). Transposable elements and the evolution of insects. Annual Review of Entomology, 66, 355–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallmann, C. A. , Sorg, M. , Jongejans, E. , Siepel, H. , Hofland, N. , Schwan, H. , Stenmans, W. , Müller, A. , Sumser, H. , & Hörren, T. (2017). More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas. PLoS ONE, 12, e0185809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halsch, C. A. , Shapiro, A. M. , Fordyce, J. A. , Nice, C. C. , Thorne, J. H. , Waetjen, D. P. , & Forister, M. L. (2021). Insects and recent climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118, e2002543117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann, E. , Blevins, C. , Franks, S. J. , Jameel, M. I. , & Anderson, J. T. (2021). Climate change alters plant–herbivore interactions. New Phytologist, 229, 1894–1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanski, I. , Koivulehto, H. , Cameron, A. , & Rahagalala, P. (2007). Deforestation and apparent extinctions of endemic forest beetles in Madagascar. Biology Letters, 3, 344–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, N. J. , Bass, C. , Dixon, A. , & Neve, P. (2019). The evolutionary origins of pesticide resistance. Biological Reviews, 94, 135–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickx, F. , Backeljau, T. , Dekoninck, W. , Van Belleghem, S. M. , Vandomme, V. , & Vangestel, C. (2015). Persistent inter‐ and intraspecific gene exchange within a parallel radiation of caterpillar hunter beetles (Calosoma sp.) from the Galápagos. Molecular Ecology, 24, 3107–3121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendry, A. P. , Gotanda, K. M. , & Svensson, E. I. (2017). Human influences on evolution, and the ecological and societal consequences. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372, 1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, A. A. (2017). Rapid adaptation of invertebrate pests to climatic stress? Current Opinion in Insect Science, 21, 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, A. A. , & Weeks, A. R. (2007). Climatic selection on genes and traits after a 100 year‐old invasion: A critical look at the temperate‐tropical clines in Drosophila melanogaster from eastern Australia. Genetica, 129, 133–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood, G. R. , Powell, T. H. , Doellman, M. M. , Sim, S. B. , Glover, M. , Yee, W. L. , Goughnour, R. B. , Mattsson, M. , Schwarz, D. , & Feder, J. L. (2020). Rapid and repeatable host plant shifts drive reproductive isolation following a recent human‐mediated introduction of the apple maggot fly, Rhagoletis pomonella . Evolution, 74, 156–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotaling, S. , Finn, D. S. , Joseph Giersch, J. , Weisrock, D. W. , & Jacobsen, D. (2017). Climate change and alpine stream biology: Progress, challenges, and opportunities for the future. Biological Reviews, 92, 2024–2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inskeep, K. A. , Doellman, M. M. , Powell, T. H. , Berlocher, S. H. , Seifert, N. R. , Hood, G. R. , Ragland, G. J. , Meyers, P. J. , & Feder, J. L. (2021). Divergent diapause life history timing drives both allochronic speciation and reticulate hybridization in an adaptive radiation of Rhagoletis flies. Molecular Ecology, 31, 4031–4049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M. T. , Prashad, C. M. , Lavoignat, M. , & Saini, H. S. (2018). Contrasting the effects of natural selection, genetic drift and gene flow on urban evolution in white clover (Trifolium repens). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 285, 20181019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapun, M. , Fabian, D. K. , Goudet, J. , & Flatt, T. (2016). Genomic evidence for adaptive inversion clines in Drosophila melanogaster . Molecular Biology and Evolution, 33, 1317–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, B. , & Van Dyck, H. (2005). Does habitat fragmentation affect temperature‐related life‐history traits? A laboratory test with a woodland butterfly. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 272, 1257–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettlewell, B. (1973). The evolution of melanism: The study of a recurring necessity. Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kinzner, M.‐C. , Gamisch, A. , Hoffmann, A. A. , Seifert, B. , Haider, M. , Arthofer, W. , Schlick‐Steiner, B. C. , & Steiner, F. M. (2019). Major range loss predicted from lack of heat adaptability in an alpine Drosophila species. Science of the Total Environment, 695, 133753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch, J. B. , Dupuis, J. R. , Jardeleza, M.‐K. , Ouedraogo, N. , Geib, S. M. , Follett, P. A. , & Price, D. K. (2020). Population genomic and phenotype diversity of invasive Drosophila suzukii in Hawai‘i. Biological Invasions, 22, 1753–1770. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, G. M. , Wadsworth, C. B. , Kahne, S. C. , Bogdanowicz, S. M. , Harrison, R. G. , Coates, B. S. , & Dopman, E. B. (2019). Genomic basis of circannual rhythm in the european corn borer moth. Current Biology, 29, 3501–3509.e3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, L. T. , Dudaniec, R. Y. , Chauhan, P. , Wellenreuther, M. , Svensson, E. I. , & Hansson, B. (2016). Gene expression under thermal stress varies across a geographical range expansion front. Molecular Ecology, 25, 1141–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, L. T. , Dudaniec, R. Y. , Hansson, B. , & Svensson, E. I. (2015). Latitudinal shift in thermal niche breadth results from thermal release during a climate‐mediated range expansion. Journal of Biogeography, 42, 1953–1963. [Google Scholar]

- Leihy, R. I. , & Chown, S. L. (2020). Wind plays a major but not exclusive role in the prevalence of insect flight loss on remote islands. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 287, 20202121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, S. L. , & Maslin, M. A. (2015). Defining the anthropocene. Nature, 519, 171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, F. , Zhao, X. , Li, M. , He, K. , Huang, C. , Zhou, Y. , Li, Z. , & Walters, J. R. (2019). Insect genomes: Progress and challenges. Insect Molecular Biology, 28, 739–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N. (2015). Insecticide iesistance in mosquitoes: Impact, mechanisms, and research directions. Annual Review of Entomology, 60, 537–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. , Henkel, J. , Beaurepaire, A. , Evans, J. D. , Neumann, P. , & Huang, Q. (2021). Comparative genomics suggests local adaptations in the invasive small hive beetle. Ecology and Evolution, 11, 15780–15791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love, R. R. , Steele, A. M. , Coulibaly, M. B. , Traore, S. F. , Emrich, S. J. , Fontaine, M. C. , & Besansky, N. J. (2016). Chromosomal inversions and ecotypic differentiation in Anopheles gambiae: The perspective from whole‐genome sequencing. Molecular Ecology, 25, 5889–5906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majerus, M. E. N. (1998). Melanism: Evolution in action. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, K. E. , Gotthard, K. , & Williams, C. M. (2020). Evolutionary impacts of winter climate change on insects. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 41, 54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCain, C. M. , & Garfinkel, C. F. (2021). Climate change and elevational range shifts in insects. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 47, 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch, G. A. , Foster, B. J. , Dutoit, L. , Harrop, T. W. R. , Guhlin, J. , Dearden, P. K. , & Waters, J. M. (2021). Genomics reveals widespread ecological speciation in flightless insects. Systematic Biology, 70, 863–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch, G. A. , Foster, B. J. , Dutoit, L. , Ingram, T. , Hay, E. , Veale, A. J. , Dearden, P. K. , & Waters, J. M. (2019). Ecological gradients drive insect wing loss and speciation: The role of the alpine treeline. Molecular Ecology, 28, 3141–3150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch, G. A. , Foster, B. J. , Ingram, T. , & Waters, J. M. (2019). Insect wing loss is tightly linked to the treeline: Evidence from a diverse stonefly assemblage. Ecography, 42, 811–813. [Google Scholar]

- McGill, B. J. , Dornelas, M. , Gotelli, N. J. , & Magurran, A. E. (2015). Fifteen forms of biodiversity trend in the Anthropocene. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 30, 104–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan, I. D. (1997). Austroperla cyrene Newman (Plecoptera: Austroperlidae). Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 27, 271–278. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan, I. D. (1999). A revision of Zelandoperla Tillyard (Plecoptera: Gripopterygidae: Zelandoperlinae). New Zealand Journal of Zoology, 26, 199–219. [Google Scholar]

- McWethy, D. B. , Whitlock, C. , Wilmshurst, J. M. , McGlone, M. S. , Fromont, M. , Li, X. , Dieffenbacher‐Krall, A. , Hobbs, W. O. , Fritz, S. C. , & Cook, E. R. (2010). Rapid landscape transformation in South Island, New Zealand, following initial Polynesian settlement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107, 21343–21348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlin, C. , Liams, S. E. , & Lugena, A. B. (2020). Monarch butterfly migration moving into the genetic era. Trends in Genetics, 36, 689–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mérot, C. , Berdan, E. L. , Babin, C. , Normandeau, E. , Wellenreuther, M. , & Bernatchez, L. (2018). Intercontinental karyotype‐environment parallelism supports a role for a chromosomal inversion in local adaptation in a seaweed fly. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 285, 20180519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikheyev, A. S. , Tin, M. M. , Arora, J. , & Seeley, T. D. (2015). Museum samples reveal rapid evolution by wild honey bees exposed to a novel parasite. Nature Communications, 6, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, R. M. , Wallberg, A. , Simões, Z. L. P. , Lawson, D. J. , & Webster, M. T. (2017). Genomewide analysis of admixture and adaptation in the Africanized honeybee. Molecular Ecology, 26, 3603–3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogués‐Bravo, D. , Rodríguez‐Sánchez, F. , Orsini, L. , de Boer, E. , Jansson, R. , Morlon, H. , Fordham, D. A. , & Jackson, S. T. (2018). Cracking the code of biodiversity responses to past climate change. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 33, 765–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris, L. C. , Main, B. J. , Lee, Y. , Collier, T. C. , Fofana, A. , Cornel, A. J. , & Lanzaro, G. C. (2015). Adaptive introgression in an African malaria mosquito coincident with the increased usage of insecticide‐treated bed nets. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112, 815–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosil, P. (2007). Divergent host plant adaptation and reproductive isolation between ecotypes of Timema cristinae walking sticks. The American Naturalist, 169, 151–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyström, P. , McIntosh, A. R. , & Winterbourn, M. J. (2003). Top‐down and bottom‐up processes in grassland and forested streams. Oecologia, 136, 596–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolucci, S. , Salis, L. , Vermeulen, C. J. , Beukeboom, L. W. , & van de Zande, L. (2016). QTL analysis of the photoperiodic response and clinal distribution of period alleles in Nasonia vitripennis . Molecular Ecology, 25, 4805–4817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmesan, C. (2006). Ecological and evolutionary responses to recent climate change. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 37, 637–669. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoal, S. , Cezard, T. , Eik‐Nes, A. , Gharbi, K. , Majewska, J. , Payne, E. , Ritchie, M. G. , Zuk, M. , & Bailey, N. W. (2014). Rapid convergent evolution in wild crickets. Current Biology, 24, 1369–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoal, S. , Risse, J. E. , Zhang, X. , Blaxter, M. , Cezard, T. , Challis, R. J. , Gharbi, K. , Hunt, J. , Kumar, S. , Langan, E. , Liu, X. , Rayner, J. G. , Ritchie, M. G. , Snoek, B. L. , Trivedi, U. , & Bailey, N. W. (2020). Field cricket genome reveals the footprint of recent, abrupt adaptation in the wild. Evolution Letters, 4, 19–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pélissié, B. , Chen, Y. H. , Cohen, Z. P. , Crossley, M. S. , Hawthorne, D. J. , Izzo, V. , & Schoville, S. D. (2022). Genome resequencing reveals rapid, repeated evolution in the Colorado potato beetle. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 39, msac016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pélissié, B. , Crossley, M. S. , Cohen, Z. P. , & Schoville, S. D. (2018). Rapid evolution in insect pests: The importance of space and time in population genomics studies. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 26, 8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Privman, E. , Cohen, P. , Cohanim, A. B. , Riba‐Grognuz, O. , Shoemaker, D. , & Keller, L. (2018). Positive selection on sociobiological traits in invasive fire ants. Molecular Ecology, 27, 3116–3130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruisscher, P. , Nylin, S. , Gotthard, K. , & Wheat, C. W. (2018). Genetic variation underlying local adaptation of diapause induction along a cline in a butterfly. Molecular Ecology, 27, 3613–3626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puinean, A. M. , Foster, S. P. , Oliphant, L. , Denholm, I. , Field, L. M. , Millar, N. S. , Williamson, M. S. , & Bass, C. (2010). Amplification of a cytochrome P450 gene is associated with resistance to neonicotinoid insecticides in the aphid Myzus persicae . PLoS Genetics, 6, e1000999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rane, R. V. , Rako, L. , Kapun, M. , Lee, S. F. , & Hoffmann, A. A. (2015). Genomic evidence for role of inversion 3 RP of Drosophila melanogaster in facilitating climate change adaptation. Molecular Ecology, 24, 2423–2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner, J. , Aldridge, S. , Montealegre‐Z, F. , & Bailey, N. W. (2019). A silent orchestra: Convergent song loss in Hawaiian crickets is repeated, morphologically varied, and widespread. Ecology, 100, e02694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera‐Marchand, B. , Oskay, D. , & Giray, T. (2012). Gentle Africanized bees on an oceanic Island. Evolutionary Applications, 5, 746–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riveron, J. M. , Irving, H. , Ndula, M. , Barnes, K. G. , Ibrahim, S. S. , Paine, M. J. , & Wondji, C. S. (2013). Directionally selected cytochrome P450 alleles are driving the spread of pyrethroid resistance in the major malaria vector Anopheles funestus . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110, 252–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez‐Guillén, R. A. , Córdoba‐Aguilar, A. , Hansson, B. , Ott, J. , & Wellenreuther, M. (2016). Evolutionary consequences of climate‐induced range shifts in insects. Biological Reviews, 91, 1050–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez‐Guillén, R. A. , Muñoz, J. , Rodríguez‐Tapia, G. , Feria Arroyo, T. P. , & Córdoba‐Aguilar, A. (2013). Climate‐induced range shifts and possible hybridisation consequences in insects. PLoS ONE, 8, e80531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo, J. S. , Johnson, M. T. , & Ness, R. W. (2018). Modern spandrels: The roles of genetic drift, gene flow and natural selection in the evolution of parallel clines. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 285, 20180230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlipalius, D. I. , Valmas, N. , Tuck, A. G. , Jagadeesan, R. , Ma, L. , Kaur, R. , Goldinger, A. , Anderson, C. , Kuang, J. , & Zuryn, S. (2012). A core metabolic enzyme mediates resistance to phosphine gas. Science, 338, 807–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader, L. , Kim, J. W. , Ence, D. , Zimin, A. , Klein, A. , Wyschetzki, K. , Weichselgartner, T. , Kemena, C. , Stökl, J. , & Schultner, E. (2014). Transposable element islands facilitate adaptation to novel environments in an invasive species. Nature Communications, 5, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seebens, H. , Blackburn, T. M. , Dyer, E. E. , Genovesi, P. , Hulme, P. E. , Jeschke, J. M. , Pagad, S. , Pyšek, P. , Winter, M. , Arianoutsou, M. , Bacher, S. , Blasius, B. , Brundu, G. , Capinha, C. , Celesti‐Grapow, L. , Dawson, W. , Dullinger, S. , Fuentes, N. , Jäger, H. , … Essl, F. (2017). No saturation in the accumulation of alien species worldwide. Nature Communications, 8, 14435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah, A. A. , Dillon, M. E. , Hotaling, S. , & Woods, H. A. (2020). High elevation insect communities face shifting ecological and evolutionary landscapes. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 41, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sih, A. , Ferrari, M. C. , & Harris, D. J. (2011). Evolution and behavioural responses to human‐induced rapid environmental change. Evolutionary Applications, 4, 367–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K. S. , Troczka, B. J. , Duarte, A. , Balabanidou, V. , Trissi, N. , Carabajal Paladino, L. Z. , Nguyen, P. , Zimmer, C. T. , Papapostolou, K. M. , & Randall, E. (2020). The genetic architecture of a host shift: An adaptive walk protected an aphid and its endosymbiont from plant chemical defenses. Science Advances, 6, eaba1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stork, N. E. (2018). How many species of insects and other terrestrial arthropods are there on earth? Annual Review of Entomology, 63, 31–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, T. , Suzuki, N. , & Tojo, K. (2019). Parallel evolution of an alpine type ecomorph in a scorpionfly: Independent adaptation to high‐altitude environments in multiple mountain locations. Molecular Ecology, 28, 3225–3240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telonis‐Scott, M. , Hoffmann, A. A. , & Sgro, C. M. (2011). The molecular genetics of clinal variation: A case study of ebony and thoracic trident pigmentation in Drosophila melanogaster from eastern Australia. Molecular Ecology, 20, 2100–2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, C. D. , Jones, T. H. , & Hartley, S. E. (2019). “Insectageddon”: A call for more robust data and rigorous analyses. Global Change Biology, 25, 1891–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troczka, B. , Zimmer, C. T. , Elias, J. , Schorn, C. , Bass, C. , Davies, T. E. , Field, L. M. , Williamson, M. S. , Slater, R. , & Nauen, R. (2012). Resistance to diamide insecticides in diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) is associated with a mutation in the membrane‐spanning domain of the ryanodine receptor. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 42, 873–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trueman, J. W. H. , Pfeil, B. E. , Kelchner, S. A. , & Yeates, D. K. (2004). Did stick insects really regain their wings? Systematic Entomology, 29, 138–139. [Google Scholar]

- van Asch, M. , Salis, L. , Holleman, L. J. M. , van Lith, B. , & Visser, M. E. (2013). Evolutionary response of the egg hatching date of a herbivorous insect under climate change. Nature Climate Change, 3, 244–248. [Google Scholar]

- van Asch, M. , Van Tienderen, P. H. , Holleman, L. J. M. , & Visser, M. E. (2007). Predicting adaptation of phenology in response to climate change, an insect herbivore example. Global Change Biology, 13, 1596–1604. [Google Scholar]

- van Klink, R. , Bowler, D. E. , Gongalsky, K. B. , & Chase, J. M. (2022). Long‐term abundance trends of insect taxa are only weakly correlated. Biology Letters, 18, 20210554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van't Hof, A. E. , Campagne, P. , Rigden, D. J. , Yung, C. J. , Lingley, J. , Quail, M. A. , Hall, N. , Darby, A. C. , & Saccheri, I. J. (2016). The industrial melanism mutation in British peppered moths is a transposable element. Nature, 534, 102–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van't Hof, A. E. , Reynolds, L. A. , Yung, C. J. , Cook, L. M. , & Saccheri, I. J. (2019). Genetic convergence of industrial melanism in three geometrid moths. Biology Letters, 15, 20190582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitousek, P. M. , Mooney, H. A. , Lubchenco, J. , & Melillo, J. M. (1997). Human domination of Earth's ecosystems. Science, 277, 494–499. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, D. L. (2020). Insect declines in the Anthropocene. Annual Review of Entomology, 65, 457–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, B. D. (1861). On phytophagic varieties and phytophagic species. Kessinger Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. , Fang, X. , Yang, P. , Jiang, X. , Jiang, F. , Zhao, D. , Li, B. , Cui, F. , Wei, J. , & Ma, C. (2014). The locust genome provides insight into swarm formation and long‐distance flight. Nature Communications, 5, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters, J. M. , Emerson, B. C. , Arribas, P. , & McCulloch, G. A. (2020). Dispersal reduction: Causes, genomic mechanisms, and evolutionary consequences. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 35, 512–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters, J. M. , & McCulloch, G. A. (2021). Reinventing the wheel? Reassessing the roles of gene flow, sorting and convergence in repeated evolution. Molecular Ecology, 30, 4162–4172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellenreuther, M. , & Bernatchez, L. (2018). Eco‐evolutionary genomics of chromosomal inversions. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 33, 427–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield, C. W. , Behura, S. K. , Berlocher, S. H. , Clark, A. G. , Johnston, J. S. , Sheppard, W. S. , Smith, D. R. , Suarez, A. V. , Weaver, D. , & Tsutsui, N. D. (2006). Thrice out of Africa: Ancient and recent expansions of the honey bee, Apis mellifera . Science, 314, 642–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willi, Y. , & Hoffmann, A. A. (2012). Microgeographic adaptation linked to forest fragmentation and habitat quality in the tropical fruit fly drosophila birchii . Oikos, 121, 1627–1637. [Google Scholar]

- Wittkopp, P. J. , True, J. R. , & Carroll, S. B. (2002). Reciprocal functions of the drosophila yellow and ebony proteins in the development and evolution of pigment patterns. Development, 129, 1849–1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woronik, A. , Tunström, K. , Perry, M. W. , Neethiraj, R. , Stefanescu, C. , Celorio‐Mancera, M. d. l. P. , Brattström, O. , Hill, J. , Lehmann, P. , & Käkelä, R. (2019). A transposable element insertion is associated with an alternative life history strategy. Nature Communications, 10, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayed, A. , & Whitfield, C. W. (2008). A genome‐wide signature of positive selection in ancient and recent invasive expansions of the honey bee Apis mellifera . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105, 3421–3426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, S. , Zhang, W. , Niitepold, K. , Hsu, J. , Haeger, J. F. , Zalucki, M. P. , Altizer, S. , De Roode, J. C. , Reppert, S. M. , & Kronforst, M. R. (2014). The genetics of monarch butterfly migration and warning colouration. Nature, 514, 317–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. , Rayner, J. G. , Blaxter, M. , & Bailey, N. W. (2021). Rapid parallel adaptation despite gene flow in silent crickets. Nature Communications, 12, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuk, M. , Rotenberry, J. T. , & Tinghitella, R. M. (2006). Silent night: Adaptive disappearance of a sexual signal in a parasitized population of field crickets. Biology Letters, 2, 521–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.