Abstract

Decoding cellular processes requires visualization of the spatial distribution and dynamic interactions of biomolecules. It is therefore not surprising that innovations in imaging technologies have facilitated advances in biomedical research. The advent of super‐resolution imaging technologies has empowered biomedical researchers with the ability to answer long‐standing questions about cellular processes at an entirely new level. Fluorescent probes greatly enhance the specificity and resolution of super‐resolution imaging experiments. Here, we introduce key super‐resolution imaging technologies, with a brief discussion on single‐molecule localization microscopy (SMLM). We evaluate the chemistry and photochemical mechanisms of fluorescent probes employed in SMLM. This Review provides guidance on the identification and adoption of fluorescent probes in single molecule localization microscopy to inspire the design of next‐generation fluorescent probes amenable to single‐molecule imaging.

Keywords: Fluorescence, Photochemistry, Photoswitching, Sensors, Super-Resolution

Single molecule localization microscopy has revolutionized our ability to investigate cellular structures and processes at the nanometer scale. This Review discusses the photochemical mechanisms harnessed to develop small‐molecule probes that exhibit photoswitching properties necessary for application in imaging methods based on single‐molecule localization. Strategies to develop improved photoswitchable probes and future directions are also discussed.

1. Introduction

Fluorescence microscopy has been used for decades to study a range of biological targets and systems. [1] Although a powerful and widely adopted technology, fluorescence microscopy suffers from some key limitations. These include autofluorescence from endogenous biomolecules, poor depth penetration, and spatial‐resolution limitations imposed by the diffraction of the light. [1] The spatial resolution of standard fluorescence microscopy techniques is limited to roughly half the wavelength of the excitation light. [2] There have been multiple efforts to circumvent the interference from autofluorescence, such as near‐infrared and multiphoton imaging techniques, which have been reviewed elsewhere. [3]

The diffraction limit, first formulated in 1873 by Ernst Abbe, defines the inability of optical instrumentation to resolve two objects separated by a lateral distance less than approximately half the wavelength of the excitation light. [4] As a result of diffraction, the image of an arbitrarily small source of light observed using a lens‐based microscope is not a point but a point spread function (PSF). The PSF is usually an airy pattern, with a central peak approximately 200–300 nm in width, which results in a blurring of structures below this spatial scale. [5] This diffraction limit restricts the ability of optical microscopy techniques to resolve the subcellular organization of individual molecules smaller than this limit. This remained an enduring challenge until the late 1990s, when inventions in super‐resolution imaging techniques transformed the field of optical microscopy. [6] In this Review we first briefly discuss recent advances in the field of super‐resolution microscopy, with a particular focus on single molecule localization microscopy (SMLM). Following this, we outline key photophysical properties necessary for fluorescent probes in SMLM and evaluate the range of photochemical mechanisms that operate in fluorescent probes used in SMLM.

1.1. Super‐Resolution Imaging Techniques

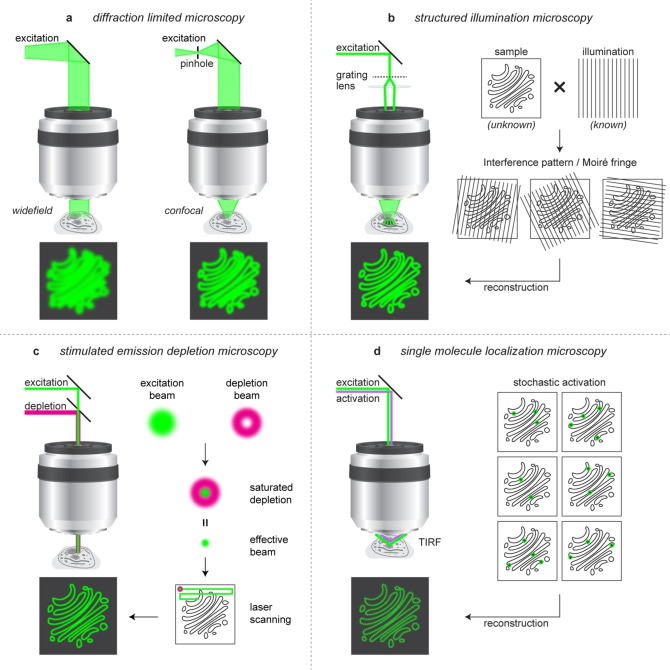

Super‐resolution microscopy (SRM) includes a range of imaging techniques that overcome the resolution limit posed by the diffraction of light. [7] SRM techniques achieve sub‐diffraction imaging by either modulating the excitation beam or by modulating or switching the fluorescence emission. [7] There are several ways of modulating excitation beams. For example, in structured illumination microscopy (SIM), the sample is illuminated with a beam having a known spatially structured pattern such as striped patterns (Figure 1b), multifocal spots, and random speckles. [8] The overlapping of the known excitation pattern with the spatial pattern of the sample produces a coarse interference pattern or moiré fringe. Translation and rotation of the excitation pattern generates a set of images with distinct moiré fringes. The combined image with the coarse pattern can be mathematically separated from the known illumination pattern, thereby resulting an image with a lateral resolution of about 100 nm. The improvement in the resolution with SIM is modest compared to other super‐resolution imaging techniques because the generation of the known illumination pattern requires diffraction‐limited optics. [7] However, SIM requires low laser powers, is compatible with conventional fluorophores and fluorescent proteins, and is widely used for live‐cell and high‐throughput imaging. [9] In addition to long acquisition times, which make the approach unsuitable for imaging rapid cellular events, the adoption of SIM has been slower than other SRM techniques due to the extensive mathematical processing of images which often require specialist knowledge. [10] Recently developed Hessian‐SIM affords imaging at 88 nm resolution, with a faster acquisition time. [11]

Figure 1.

Principles of conventional and super‐resolution microscopy techniques: a) widefield and confocal microscopy; b) structured illumination microscopy; c) stimulated emission depletion microscopy; d) single molecule localization microscopy.

The other group of techniques achieve nanoscale resolution by modulating the fluorescence emission of fluorophores and are classified into deterministic and stochastic approaches. [7] The deterministic approach is used in techniques such as stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy and ground‐state depletion (GSD) microscopy (Figure 1c). [12] Here, superior lateral resolution is achieved by optically modifying the PSF to reduce its effective diameter right at the illumination spot on the sample .[ 12a , 13 ] This is accomplished by surrounding a laser‐scanning focal excitation beam with a second, donut‐shaped depletion beam of longer‐wavelength and high intensity. The depletion beam saturates the fluorophores to a metastable dark state or ground state in STED and GSD, respectively, creating an excitation PSF that is effectively smaller than 200 nm to scan the region of interest on the sample. [6b] A lateral resolution of 40–60 nm is typically achieved using commercially available STED instruments. [14]

Stochastic approaches rely on creating transient spatial separation between fluorescent emitters, which enables the precise localization of single fluorophore molecules and are collectively termed single‐molecule localization microscopy (SMLM). [15] SMLM requires switchable fluorophores, which can be activated stochastically. In most cases, switching is typically induced by light and/or chemical activators and rely on diverse photochemical mechanisms, as described in Section 3.

1.1.1. Single Molecule Localization Microscopy

The unifying principle of SMLM techniques is that the spatial coordinates of individual fluorescent molecules can be precisely calculated if their emission PSFs do not overlap. [16] Although the emission PSF of fluorophores is diffraction‐limited, spatial separation >300 nm allows mathematical determination of the centroids of each PSF precisely in the nanometer scale. Overlaps between the emission PSFs of individual molecules can be avoided if only a sparse subset of the fluorescent molecules is emitting at any given time (Figure 1d). The most common method of achieving this separation is based on photoswitching, a phenomenon in which fluorescent molecules switch between an emissive (bright) or “ON” state and a non‐emissive (dark) or “OFF” state. [17] The switching probabilities of this otherwise stochastic event can be modulated by controlling the buffer system and/or sample illumination. Over the thousands of camera frames acquired, the majority of the fluorescent molecules will emit in at least one frame. The localizations, namely, the centroids of all the emission PSFs, are then consolidated to reconstruct the super‐resolution image.

Both photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM) and fluorescence PALM (fPALM) employ genetically modified photoactivatable fluorescent proteins that can be activated by UV illumination to achieve photoswitching between the on and off states. [18] Stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) [19] employs a pair of activator and reporter cyanine (Cy) dyes capable of reversibly photoswitching between on and off states. Direct STORM, or dSTORM, is an improved variant of STORM that eliminates the need for an activator for photoswitching, thereby enabling super‐resolution imaging with commercially available fluorophores which can photoswitch using specific excitation parameters and imaging buffers. [20] In addition to achieving a spatial resolution of about 20 nm, dSTORM also helps overcome the synthetic challenges of developing dye pairs for STORM. Another approach to avoid PSF overlap relies on fluorophores that switch between a freely diffusing state to an immobilized state which results from binding to a target. Techniques such as DNA‐point accumulation in nanoscale topography (DNA‐PAINT) and binding activated localization microscopy (BALM) fall under this category and have been extensively discussed elsewhere. [21] In addition to the crucial ability of fluorophores to switch between bright (emissive) and dark (non‐emissive) states, other fluorophore properties such as photon count, fluorophore stability, and duty cycle influence the localization precision of individual molecules as well as the resolution achieved. [22] A wide range of switchable fluorophores have been utilized for SMLM, including synthetic organic fluorophores and fluorescent proteins. Small‐molecule fluorophores are generally preferred over fluorescent proteins because they tend to have higher quantum yields and greater photostability.[ 22c , 23 ] Moreover, as a result of their size, fluorescent proteins (ca. 10 nm) give poorer resolution, as they will be further from the target to which they are bound.[ 6b , 24 ] This is known as linkage error. Linkage error is also a problem for antibody and nanobody labeling. [25] The modification of native proteins to introduce a fluorescent protein tag can also affect the form and function of the modified protein. [6b] Although beyond the scope of this Review, a range of fluorescent proteins have been developed for SMLM applications, including photoactivatable, photoswitchable, and photoconvertible fluorescent proteins, and have been extensively reviewed. [26] Here we give an overview of small organic fluorophores utilized in SMLM, with an emphasis on fluorophore properties and photochemical mechanisms.

2. Desirable Fluorophore Properties for SMLM

Diffraction‐limited fluorescence microscopy requires fluorophores which bind to, accumulate in, or otherwise interact with the target of interest. Fluorophores used in SMLM (PALM, dSTORM, etc.) must be able to be switched between an emissive (on) and a non‐emissive (off/dark) state. [20a] When selecting a photoswitching fluorophore for SMLM, not only must common photophysical properties such as excitation and emission wavelengths, extinction coefficient, and quantum yield be considered, properties such as dark‐state stability, photobleaching characteristics, photon count, and duty cycle have profound effects on image quality and, therefore, must be optimized.

2.1. Stability of the Dark State

The stability of a fluorophore's dark state is an important factor which dictates the suitability of a fluorophore for SMLM experiments. Having a more stable or longer‐lived dark state results in fewer molecules being in an emissive state at a given time, thus increasing the average separation between their PSFs. Following their excitation from the singlet ground state (S0) to the first excited state (S1), a proportion of fluorophores undergo intersystem crossing to enter the triplet state (T1, Figure 2a). A pathway by which the T1 state can be depopulated is by triplet–triplet energy transfer with molecular oxygen; however, this process generates singlet oxygen (1O2), which can then react with fluorophores. This results in irreversible fluorophore photobleaching (Figure 2a). [27] Photobleaching, therefore, is an undesirable process for SMLM.

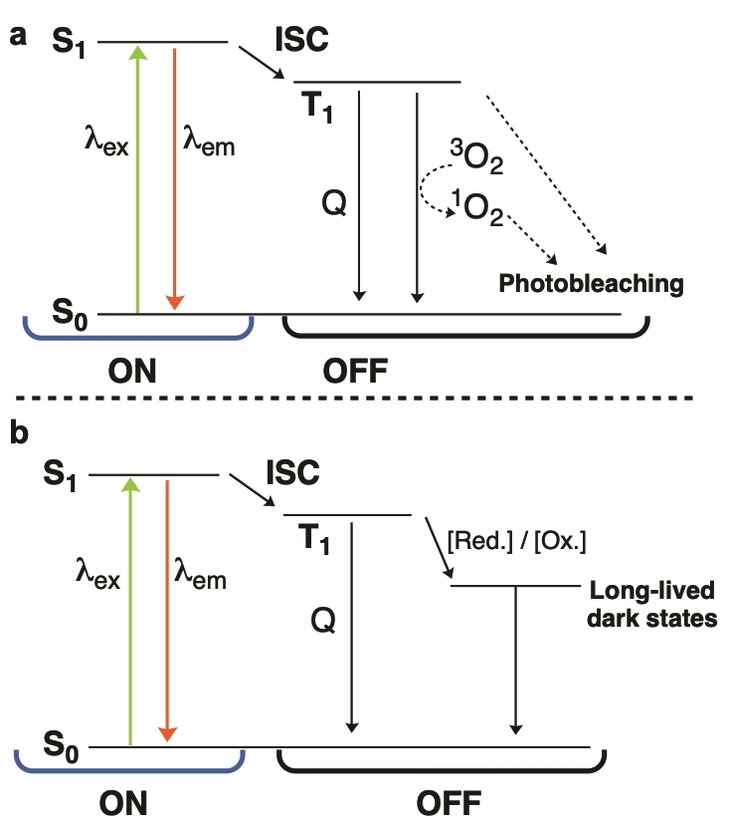

Figure 2.

Simplified Jablonski diagram representing processes to be considered for SMLM. For simplicity, neither vibrational levels nor possible additional dark states have been indicated. a) Schematic representation showing electronic transitions during normal fluorescence. In the ON‐state, fluorophores are excited from the ground state (S0) to the excited singlet state (S1). From S1, they may relax radiatively to S0 or undergo intersystem crossing to the dark triplet state (T1). The T1 state can be returned to S0 by triplet–triplet energy transfer with 3O2 to generate 1O2, thereby resulting in photobleaching. Triplet quenchers (Q) such as COT or Ni2+ prevent the generation of 1O2. b) Redox‐active buffers can be used to depopulate the T1 state to generate long‐lived dark states and ground state. Fluorophores then return to S0 through inverse redox reactions or UV light.

The T1 state is a dark state but is short‐lived and not suitable for SMLM. To extend the lifetime of the dark state, more stable electronic states can be accessed. [28] This involves redox‐active molecules that undergo photoinduced electron transfer with the T1 state of the fluorophores, functioning either as electron acceptors or electron donors and generating the fluorophore radical cation or radical anion respectively (Figure 2b). The radical ion intermediates may return to the ground state by inverse redox reactions, or on exposure to near‐UV radiation (back‐pumping). The specific mechanisms and states involved can vary greatly depending on the fluorophore and the conditions used and are, therefore, discussed in further detail in later sections. Current strategies to increase the photostability of fluorophores and optimize the photoswitching behavior for SMLM operate through a two‐pronged approach. The first is to minimize the available oxygen, which is commonly achieved by using oxygen‐scavenging systems such as glucose oxidase and catalase (GODCAT) or protocatechuic acid/protochatechuate‐3,4‐dioxygenase (PCA/PCD). [29] Triplet‐state quenchers, such as cyclooctatetraene (COT) and Ni2+, have been shown to reduce the lifetime of the T1 state by depopulating fluorophores from the T1 state to the S0, thus preventing oxygen‐mediated photobleaching. [30] The second is to efficiently depopulate the T1 state to long‐lived radical‐ion states, followed by regenerating the fluorophore ground state. This has been achieved with thiols such as cysteamine (MEA) and 2‐mercaptoethanol (βME) or with reducing and oxidizing systems (ROXS) such as methyl viologen and ascorbic acid. [28]

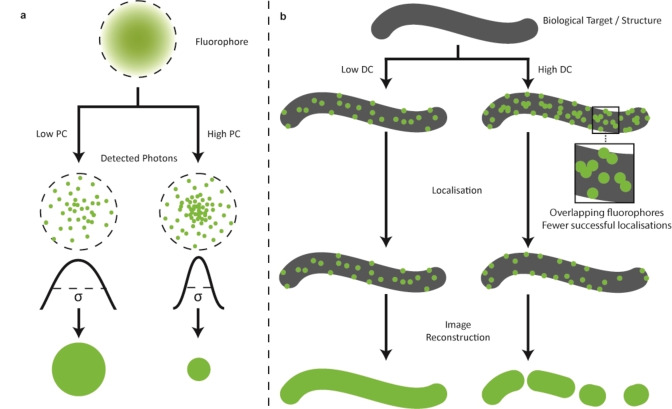

2.2. Photon Count

The photon count (PC) can be defined as the number of detected photons emitted by a single fluorophore molecule per localization. Since SMLM techniques rely on the localization of individual fluorophore molecules, a higher photon count gives a greater signal to noise ratio (S/N) and thus a higher localization precision. The relationship between PC (N) and the standard deviation of errors in estimated localizations (σ loc) is known as the Cramér‐Rao Lower Bound (CRLB) and can be described by Equation 1:[ 15 , 31 ]

| (1) |

where σ 0 is the standard deviation of the PSF, a is the pixel size of the camera, and b is the background intensity (noise). This equation can also be approximated by the simplified form shown in Equation 2:

| (2) |

Whichever form of the equation is used, as N increases, the error in the localization (σ loc) decreases. Since resolution is directly connected to σ loc, an increase in N improves the resolution of the image (Figure 3a). [31]

Figure 3.

The effects of fluorophore properties on SMLM image reconstruction. a) The effect of photon count (PC) on the point spread function (PSF) and thus localization error. A low photon count increases the width of the PSF, while a high PC decreases the width. b) The effect of duty cycle (DC) on fluorophore localization and final image. A low duty cycle increases the number of localizations in high density areas, which gives a more accurate representation of the target once the image is reconstructed.

Photon count is proportional to both the quantum yield (Φ) and extinction coefficient (ϵ) of a fluorophore, as shown in Equation 3; therefore an increase in either will result in an increased photon count and thus a higher localization precision.

| (3) |

2.3. Duty Cycle

The on‐off duty cycle (or simply “duty cycle”) describes the fraction of time in which a fluorophore is in its on state relative to its off state. As the duty cycle increases, the chance of multiple fluorophore molecules being activated in a diffraction‐limited area increases (Figure 3b). This results in a reduced spatial separation between emissive fluorophores and, therefore, fewer successful localizations. This has been demonstrated in the imaging of clathrin‐coated pits with both AlexaFluor 647 (AF647) and Cy5.5. [22c] Both fluorophores have similar photon counts (N≈6000), while Cy5.5 has a duty cycle approximately 6 times higher (0.0073) than that of AF647 (0.0012). The image obtained using Cy5.5 showed vastly fewer localizations and, therefore, less detail than the image obtained using AF647. Furthermore, depending on the filtering algorithm applied, a high duty cycle can also lead to ghost structures or blurring in regions with short spacings between structures or where structures overlap. [32] Both the duty cycle and the rate of photobleaching are directly affected by the stability of the dark state. Although it is important to consider the dark‐state stability, photobleaching characteristics, photon count, and duty cycle of fluorophores used in SMLM, to achieve successful imaging, it is equally important to consider the photochemical mechanisms that can be used to change, turn on, or reversibly switch the fluorescence of fluorophores.

3. Photochemical Mechanisms of Fluorophores Used in SMLM

The key property of fluorophores for use in SMLM is their ability to switch between bright and dark states. There are a range of mechanisms by which fluorophores achieve such switching. Processes such as photoconversion and uncaging are irreversible processes that result in a bathochromic shift or a fluorogenic response. These strategies can be used to minimize background fluorescence or improve spatial separation. Other processes are reversible and allow repeated switching between the on and off states. Irreversible processes are often used to improve the signal to noise ratio (S/N), either through bioorthogonal labeling or by reducing the total number of fluorophores in the off state. The following sections describe the main photochemical mechanisms (photoconversion, photo‐uncaging, photoswitching, and activator–reporter dyads (a subtype of photoswitching), with key examples of fluorophores for each. The photophysical properties of key probes used in SMLM are also summarized in Table S1 to assist readers.

3.1. Photoconversion

Photoconversion is a process wherein irradiation of a fluorophore with a specific wavelength of light results in a new molecule with altered photophysical properties. The photoconversion of fluorophores tends to cause hypsochromic shifts in the excitation and emission spectra and is, therefore, also termed photoblueing. The magnitude of the shift depends upon the extent of the structural changes in the fluorophore scaffold. Photoconversion was first observed in rhodamines, but has since been observed in various other classes of fluorophores such as triarylmethanes, BODIPY dyes, fluorescent proteins, cyanines, and coumarins. [33] Photoconversion typically presents as a confounding factor when conducting multicolor SMLM experiments, but photoconversion has itself recently been harnessed as a photoswitching technique for SMLM. [34]

The photoconversion mechanism depends on the class of fluorophore. Fluorophores that contain N‐alkyl substituents readily undergo N‐dealkylation (Figure 4a).[ 33a , 33b , 33f ] Although N‐dealkylation has only been observed in rhodamines (tetramethylrhodamine (TMR)), coumarins, and triarylmethanes (crystal violet (CV)), it is conceivable that dealkylation could occur in any fluorophore that contains an N‐alkyl substituent. This process has been shown to occur by oxidation of the excited fluorophore to give the amine radical cation, which after α‐deprotonation to give a radical at the α‐carbon atom, undergoes oxidation and subsequent fragmentation to reveal the N‐dealkylated product with loss of aldehyde. [35]

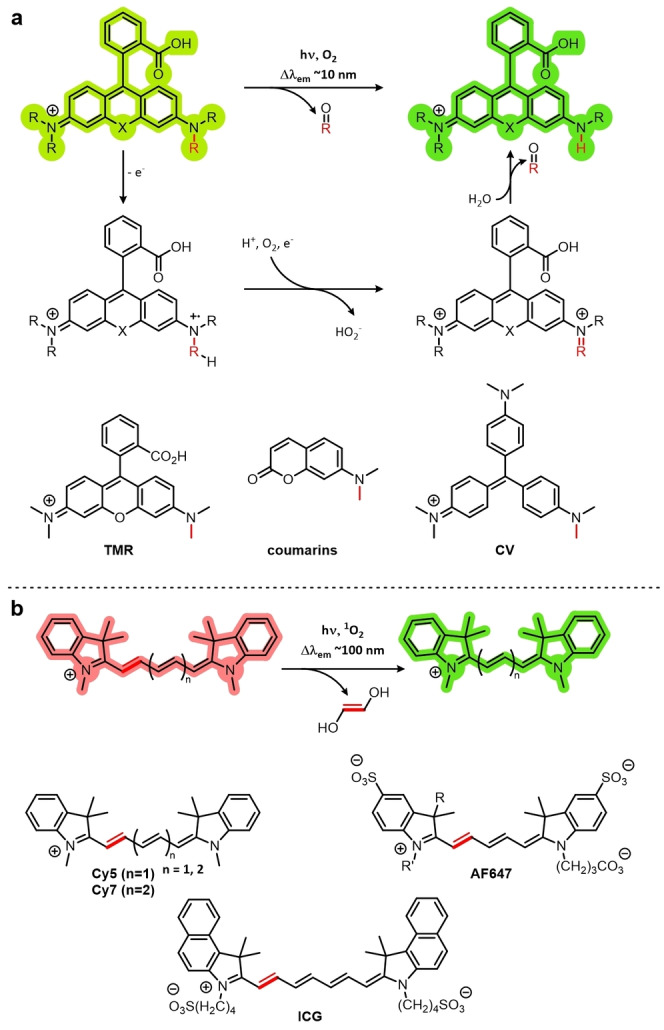

Figure 4.

The photoconversion mechanisms of fluorophores. a) Fluorophores containing an N‐alkyl substituent such as rhodamines (tetramethylrhodamine (TMR)), coumarins, and triarylmethanes (crystal violet (CV)) can undergo photocatalyzed dealkylation. b) Cyanines such as Cy5, Cy7, AlexaFluor 647 (AF647), and indocyanine green (ICG) can be photochemically truncated by the action of singlet oxygen.

N‐Dealkylation can be minimized by preventing either oxidation of the intermediate radical cation by the addition of strongly electron‐withdrawing alkyl groups, or by preventing deprotonation of the α‐carbon atom by the use of a quaternary center. [36] Deuteration of rhodamine N‐alkyl groups has also been shown to reduce the rate of oxidation, because of a primary kinetic isotope effect (direct mesolysis of the C−H/D bond). [35] Since N‐dealkylation products tend to show small (ca. 10–15 nm) hypsochromic shifts relative to their parent compounds, they are spectrally indistinguishable and, therefore, have not been used in SMLM applications.

Cyanines also exhibit photoblueing artifacts in super‐resolution microscopy. [33e] However, owing to the phototruncation mechanism, the hypsochromic shift in the emission wavelength is significantly larger (ca. 90–120 nm; Figure 4b). As reported recently, this is due to the decreased conjugation in the cyanine scaffold (Cy7, Cy5, AF647, Indocyanine Green (ICG)), brought about by the excision of an ethylene group mediated by singlet oxygen. [34] The authors also demonstrated the application of cyanine phototruncation in super‐resolution imaging, by using DNA‐PAINT to image microtubules with a resolution of about 17 nm, an improvement of about 10 nm compared to conventional DNA‐PAINT. Cyanine phototruncation has also been used in dSTORM imaging. [37]

3.2. Photo‐Uncaging

Photo‐uncaging involves the activation of a “caged” fluorophore by the release of a photolabile caging group. The use of photolabile groups to unmask other functionality has been used for almost 60 years, [38] but the potential for the use of caged fluorophores in biological studies was not realized until 1978, when o‐nitrobenzyl‐caged ATP was used as a unmetabolizable, photolyzable source of ATP. [39] The o‐nitrobenzyl caging group is still in use today, but there are now a range of other caging groups that have improved photophysical properties or which feature other useful functionalities, such as specific bioorthogonal labeling groups or improved biocompatibility, in which interaction with the target to be imaged uncages the molecule to elicit a turn‐on response. [40]

Three common ways in which caging groups keep their fluorophore in a dark state are: fluorescence quenching through Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET), through‐bond energy transfer (TBET) or intramolecular charge transfer (ICT); manipulation of chemical equilibria and electronics (fluoresceins and rhodamines); or by the photochemical disruption of conjugation. [41] Key examples of fluorophores that operate by each mechanism are summarized below.

Fluorescence quenching through energy transfer offers a versatile method of caging fluorophores. Tetrazines are commonly used for energy‐transfer quenching, and the high photoreactivity and bioorthogonality of these groups makes them suitable for super‐resolution imaging of biological processes. Tetrazines exhibit absorption maxima around 500–525 nm, [40a] which coincides with the emission ranges of many common fluorophores such as fluoresceins, rhodamines, BODIPYs, and some coumarin‐based fluorophores. This means that they can quench fluorescence by TBET and/or FRET. When irradiated with UV light, tetrazines decompose with the loss of hydrogen cyanide or nitriles (depending on the substitution pattern) and nitrogen gas. [42] This can be used to uncage tetrazine–fluorophore conjugates for PALM imaging to elicit a turn‐on response.

In addition to their role as energy‐transfer quenchers, tetrazines can act as labeling groups with high specificity. If an alkene or alkyne is incorporated into the target, tetrazine will participate in an inverse electron demand Diels–Alder (IEDDA) reaction, [43] both fixing the fluorophore to the target, while uncaging the fluorophore to induce a turn‐on response. [41a] This makes tetrazine‐caged fluorophores potentially useful in SMLM techniques by giving a high contrast between the background and the labeled structures of interest (S/N). As a consequence of their versatility, tetrazine‐caged probes have been used in a range of different super‐resolution microscopy techniques, with a range of fluorophores, and for many different biological targets. [44] One of the major disadvantages of tetrazines is that their synthesis involves the use of highly toxic and reactive anhydrous hydrazine, [44e] and although some tetrazine‐containing building blocks are commercially available, synthesis on a commercial scale is arguably more dangerous. Another downside to the use of tetrazine caging groups is their photocleavage requires UV light, which can cause phototoxicity. [45]

Another method for fluorophore caging is to take advantage of chemical equilibria. Spirolactonization occurs in fluorescein and rhodamine dyes, whereby the lactone/closed ring form is not fluorescent, but the open form is (Figure 5a). A classic application taking advantage of this equilibrium is the hydrolysis of fluorescein diacetate (FDA). FDA, unlike fluorescein, is cell‐permeable and does not fluoresce because of the presence of electron‐withdrawing acetate groups. When applied to living cells, estersases can hydrolyze the acetate groups of FDA to reveal fluorescein, thus making this a useful technique for assaying cell viability. [46] In the context of super‐resolution imaging, the caging groups should ideally be photolabile so that they can be removed in a controlled manner.

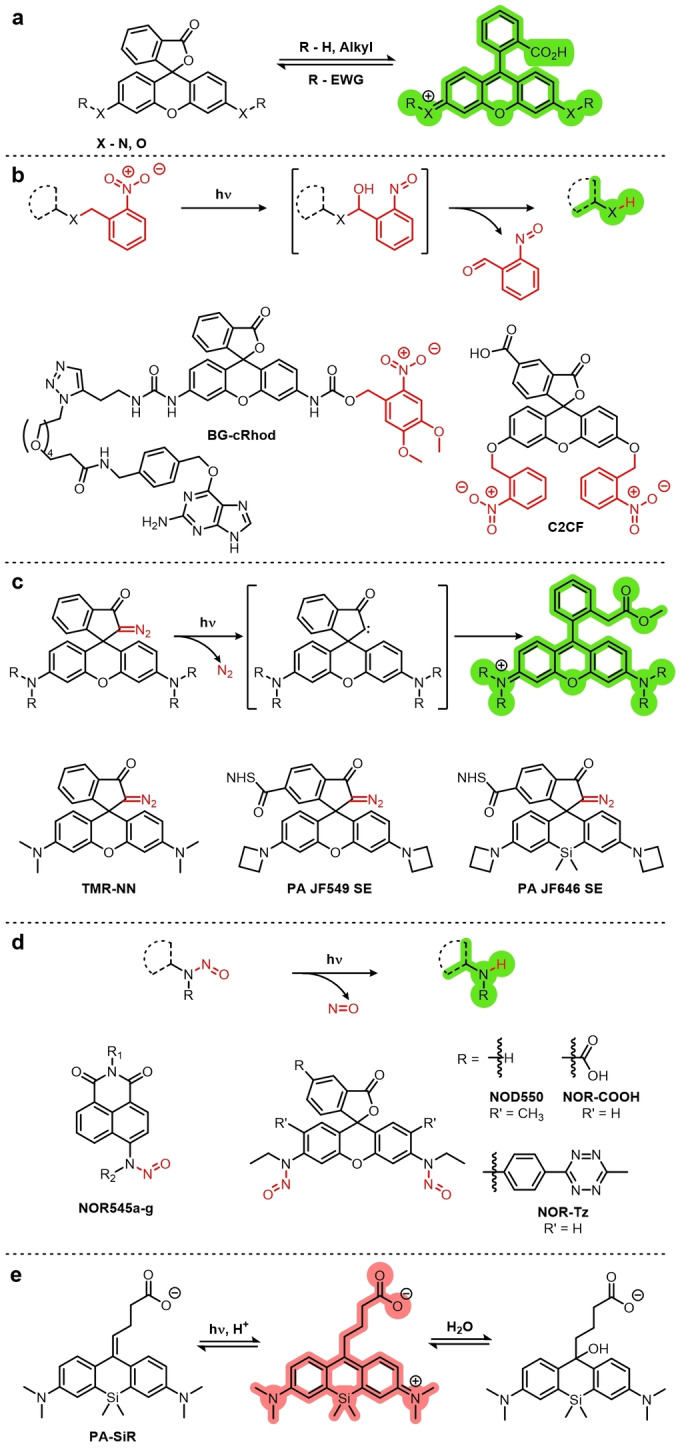

Figure 5.

Common caging groups and examples of fluorophores containing them. a) The spirolactonization equilibrium of fluoresceins (X=O) and rhodamines (X=N) gives the off (closed) and on (open) states of these fluorophores, which can be manipulated by the addition of caging groups. b) O‐Nitrobenzyl cages can be cleaved by UV light (ca. 300–360 nm) with the loss of O‐nitrosobenzaldehydes via a bicyclic intermediate. c) Rhodamines can be caged by replacement of the lactone/lactam with diazo groups, which are uncaged through a Wolff rearrangement on exposure to UV light. d) Nitrosamines readily undergo photolysis of the N−N bond with single photon excitation by UV light (365 nm). e) Photoactivation of PA‐SiR by protonation.

As is the case for FDA, fluoresceins and rhodamines are often caged at the 3′ and 6′ heteroatoms. The addition of an electron‐withdrawing group at these positions shifts the spirolactonization equilibrium to the closed ring form. o‐Nitrobenzyl groups are often chosen because of their photolability under UV light (ca. 300–360 nm; Figure 5b), which results in the formation of nitronate. [41b] The nitronate then undergoes decomposition via a hemiacetal intermediate to reveal the active fluorophore with the loss of o‐nitrosobenzaldehyde.[ 41b , 47 ] A classic example of a di‐o‐nitrobenzyl caged fluorophore is C2CF, while BG‐cRhod is a more recent mono‐caged rhodamine featuring a SNAP tag reactive moiety that has been used for PALM. [48]

o‐Nitrobenzyl cages are very hydrophobic, exhibiting undesirable properties such as poor aqueous solubility and aggregation, which can lead to aggregation‐induced quenching and a low labeling density. [49] It has also been shown that the labeling of proteins with hydrophobic small molecules can induce protein degradation. [50] In addition, these groups are photolabile when exposed to light with a wavelength of 775 nm, thus making them incompatible with STED imaging. [51] To alleviate these issues, a set of rhodamine‐based fluorophores featuring hydrophilic sulfonylated o‐nitrobenzyl caging groups was published recently by the Hell group. [52] These sulfonylated analogues showed improved aqueous solubility compared to traditional o‐nitrobenzyl caging groups and were resistant to two‐photon activation by high‐intensity STED light.

Caging groups can be installed at positions other than the 3′‐ and 6′‐positions. For example, replacement of the lactone/lactam heteroatom (O, N) with a carbon atom forces a closed ring conformation which will not undergo ring opening under normal conditions. A UV‐reactive α‐diazo group installed at this position can undergo uncaging through a Wolff rearrangement to elicit a turn‐on response (Figure 5c). The first example of a fluorophore utilizing the diazo cage is the diazo‐caged tetramethylrhodamine TMR‐NN. [40b] Diazo‐caged fluorophores have since seen a rise in popularity, with two of the JaneliaFluor dyes now available as photoactivatable diazo‐caged derivatives (PA JF549/SE, PA JF646/SE). [53]

O‐Nitrophenyl and diazo groups suffer from the same disadvantage as tetrazines in that their photocleavage requires the use of phototoxic UV light. A recent development which removes the need for UV light is the use of nitrosamine caging groups. The first nitroso‐caged fluorophore was the naphthalimide‐based NOR545, (Figure 5d). It can be activated by either single‐photon excitation at 365 nm or by two‐photon excitation at 740 nm, although the two‐photon activation results in lower fluorescence intensity. [54]

NOR545 was not used for super‐resolution microscopy, but this design was further developed to the rhodamine‐based nitroso‐caged fluorophore NOD550, which was used for PALM microscopy for the study of mitochondrial dynamics. [55] With two nitroso groups, NOD550 must be photoactivated using two different wavelengths of light, 375 nm and 525 nm. Interestingly, the 525 nm light necessary for the second photolysis was sufficient to excite and bleach the activated fluorophore. A subsequent study by the same group showed that the related fluorophores NOR‐COOH and NOR‐Tz could be both photoactivated and imaged using 525 nm light. [40c] In addition to avoiding damaging UV light, NOR‐COOH and NOR‐Tz enabled labeling, either by attachment to an antibody (NOR‐COOH) or through an IEDDA reaction with a cyclooctyne‐labeled glycan.

Another example of photoactivation is PA‐SiR; [56] rather than being activated by the removal of a caging group, it is activated by protonation upon irradiation with 340 nm light (Figure 5e). In aqueous solutions, PA‐SiR is also in equilibrium with another off form, generated by nucleophilic attack of water/hydroxide at the 9‐position. Although the resolution obtained with the use of PA‐SiR is not as good as with other fluorophores (ca. 38 nm), this is an interesting example of proton‐mediated photoactivation.

Recently, a caging‐group‐free xanthone‐based dye (Photoactivatable Xanthone (PaX)) was reported (Figure 6a). [22b] The dye takes advantage of the diradical triplet state of the ketone upon excitation by UV light. [57] By introducing a proximal alkene, the oxygen‐centered radical is able to undergo a 6‐endo‐trig radical cyclization. The product is an emissive, fully conjugated xanthene, analogous to the open form of fluorescein or rhodamine dyes. Various targeting groups were also appended to PaX, thereby allowing PALM imaging of mitochondria, lysosomes or Halo, and SNAP tag labeled proteins.

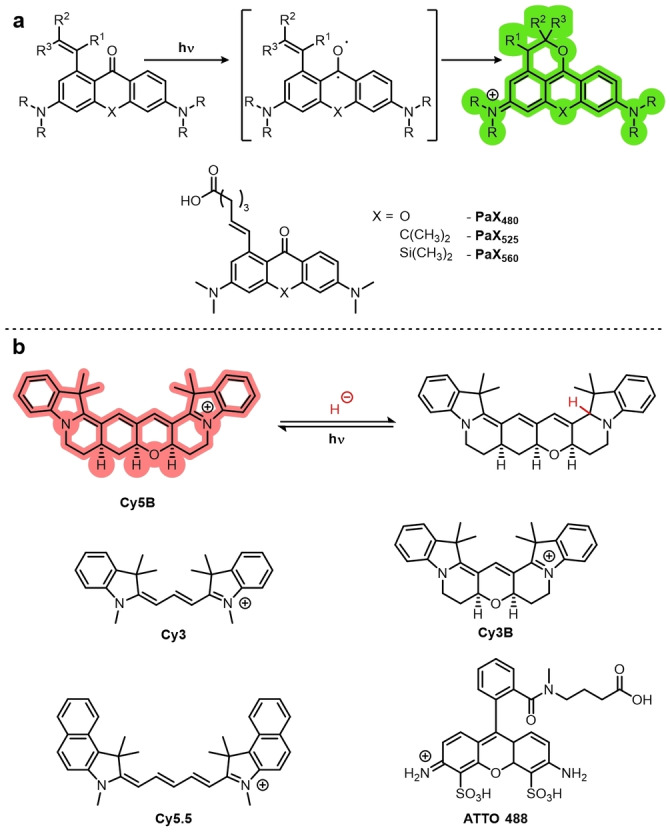

Figure 6.

Cage‐free photoactivatable fluorophores. a) Cage‐free PaX dyes undergo 6‐endo cyclizations via the triplet diradical to give an emissive product. b) Reductive caging of dyes allows photoactivation with UV light, and has been demonstrated with both cyanine‐ and rhodamine‐based dyes.

Fluorophores can also be caged by reduction. Fluorophores such as rhodamines and cyanines can be reduced using NaBH4 to give a non‐emissive leuco form. These leuco forms are photoactivatable with UV light and can be used for PALM imaging. Vaughan et al. demonstrated this with the cyanine‐based Cy3, Cy3B, Cy5.5, and AF647 and rhodamine‐based ATTO488 (Figure 6b). [58] A particularly interesting use of this strategy was the development of Cy5B, a rigid analogue of Cy5, featuring a fused ring system. [59] Cy5‐based dyes including AF647 generally feature favorable properties for SMLM, except that they have low quantum yields (ca. 0.3) as a result of multiple non‐emissive relaxation pathways, including cis‐trans isomerization.[ 22c , 60 ] Conformational restriction in Cy5B gives it significantly improved properties such as an approximately fourfold increase in quantum yield from 0.15 to 0.69 and fluorescence intensity which is not temperature dependent.

Cy5B also shows a red‐shift in λ ex (638→662 nm) and λ em (657→677 nm) relative to Cy5. Despite these favorable properties, Cy5B was found to not be photoswitchable under typical dSTORM conditions. [59] It was, however, photoactivatable after incubation in NaBH4‐containing buffer and was used for TRABI‐BP SMLM. Cy5B has since been used in PALM and shown to give significantly improved resolution (13.5 nm) compared to Cy5 (17.7 nm). [22a] These reductively caged and caging‐group‐free (PaX) strategies avoid the release potentially biologically active or toxic molecules into the sample.

3.3. Photoswitching

The previously mentioned strategies involve irreversible reactions initiated with irradiation. Photoswitchable fluorophores can be reversibly switched between a stable emissive state and a non‐emissive state. There are several ways in which a fluorophore can be photoswitched (Figure 7), which will be discussed in the following sections.

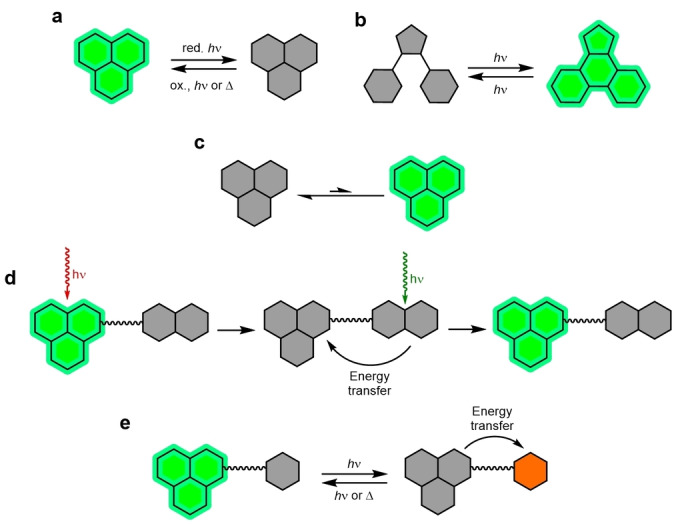

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of photoswitching mechanisms: a) Redox photoswitching of a discrete fluorophore. This requires the use of a reductant (red.) and irradiation (hν) or an oxidant (ox.). b) A photochromic fluorophore can be reversibly switched between an emissive and non‐emissive state by irradiation. c) A spontaneously blinking fluorophore that stochastically switches between a non‐emissive and emissive state. This does not require additives. d) An activator and reporter fluorophore dyad. Excitation switches the reporter to a dark state. Illumination with light within the absorbance of the activator restores the emissive state of the reporter. e) A photochromic quencher and reporter dyad. The quencher is reversibly switched between an activated quenching and non‐quenching form.

3.3.1. Photoswitchable Discrete Fluorophores

Several classes of fluorophores can inherently switch reversibly between emissive and non‐emissive states. This can be through redox‐mediated photoswitching (Figure 7a), photochromic switching (Figure 7b), or spontaneous stochastic blinking (Figure 7c). Many conventional commercially available fluorophores are capable of photoswitching when used under the correct conditions.[ 20a , 22d , 61 ] Several commercially available cyanine‐based probes such as DiI, DiD, and DiR membrane probes and MitoTracker Deep Red mitochondrial stain, as well as rhodamine‐derived MitoTracker Orange and MitoTracker Red and BODIPY‐based ER‐Tracker Red and LysoTracker Red exhibit photoswitching and have been used in STORM imaging. [62] Some classes of fluorophores are intrinsically capable of photoswitching or have modifications from the parent scaffold that allow this process. The mechanisms by which fluorophores photoswitch and the families of fluorophores used in SMLM are discussed below.

3.3.1.1. Cyanines

Cyanine derivatives were the first fluorophores discovered to be photoswitchable as single molecules and applied to super‐resolution imaging.[ 20a , 63 ] They remain the most widely studied class of photoswitching fluorophore. AF647, a sulfonated Cy5 derivative, is the most commonly used and one of the best‐performing photoswitching fluorophores. [22c]

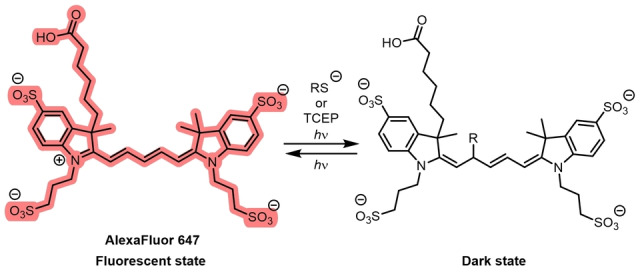

Single‐molecule fluorescence experiments showed Cy5 could be switched between a fluorescent and non‐fluorescent state by alternating the irradiation between 633 nm and 488 nm light. [63b] Cyanines typically require the use of a deoxygenated buffer containing BME or MEA to photoswitch. The formation of the dark state was shown to occur through the reversible nucleophilic addition of a thiolate (Figure 8).[ 28a , 28b ] This disrupts the conjugation and forms a nonfluorescent adduct. Cosa, Schnermann, and co‐workers used a combination of single‐molecule fluorescence, transient‐absorption spectroscopy, and computational modeling to propose that this process occurs through PET from the thiolate to the cyanine in the triplet excited state, followed by ISC in the resultant radical pair. The cyanine then either returns to the ground state by back electron transfer (BET) or the cyanine‐thiol adduct is formed. [28b] BET is the predominant pathway in Cy3. [28b] With βME used as the thiol reductant, mass‐spectrometry studies revealed that the difference in mass between Cy5 and the product after illumination corresponded exactly to the mass of βME. [28a] This process is very sensitive to the pH value; the thiol must be deprotonated.[ 28a , 28b ]

Figure 8.

The photoswitching mechanism of cyanines, exemplified with the Cy5 derivative AF647 and its non‐emissive adduct formed by reaction with a reductant.

Tris(2‐carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), and related phosphine species, have also been demonstrated to enable the photoswitching of cyanines by forming a covalent nonfluorescent adduct in a reaction that is reversible with UV irradiation. [64] This reaction also enabled super‐resolution imaging, but led to more rapid photobleaching than the reaction with thiolates. The TCEP system allowed improved two color‐imaging with Cy5 and Cy7, with a large improvement in the number of photons per switching event in Cy7 when compared to thiol reductants.[ 22c , 64 ] Cyanine dyes can also be switched to a dark state using ascorbic acid as a reductant. The mechanism involves the formation of a radical. [65] This has been demonstrated in deoxygenated buffer with various cyanine dyes including Cy5, Cy3B, and AF647. [66]

Photoisomerization of cyanines is a known pathway to dark states. This involves irradiation induced trans‐cis isomerization of the C=C bonds in the polymethine bridge, which disrupts the conjugated system. This has been proposed as a mechanism by which cyanine dyes can photoswitch. [67] This process takes place in the absence of reductants, forms a dark state, and is the major nonradiative pathway for structurally unconstrained cyanine dyes. However, in dSTORM conditions, the dark state has a lifetime of seconds, while the lifetime of the photoisomers, which are well characterized,[ 60 , 68 ] are much shorter—in the ms to μs range. Cyanine dyes with polymethine bridges of various lengths have good spectral resolution and can be used for multicolor confocal microscopy, and the same applies to SMLM with photoswitchable cyanines. Kylmchenko and co‐workers used Cy3, Cy3.5, Cy5, Cy5.5, Cy7, and Cy7.5 to generate a multicolored palette of membrane probes, MemBright, that they applied to STORM imaging. [69] In addition, AF647 can be easily conjugated to targeting ligands or sensing groups for use in fluorescent sensors that are compatible with SMLM imaging techniques. [70] The main disadvantage of AF647, and structurally related cyanines, is that sulfonated cyanines are not membrane‐permeable.

3.3.1.2. Rhodamines

Rhodamines are another class of fluorophore that are inherently photoswitchable. They can be directly photoswitched using chemical reductants and can also be designed to generate photochromic or spontaneously blinking fluorophores, by ring‐opening of the spirocycle. This versatility combined with superb photophysical properties make rhodamines a popular class of fluorophore for super‐resolution imaging.

3.3.1.2.1. Redox‐Mediated Photoswitching in Rhodamines

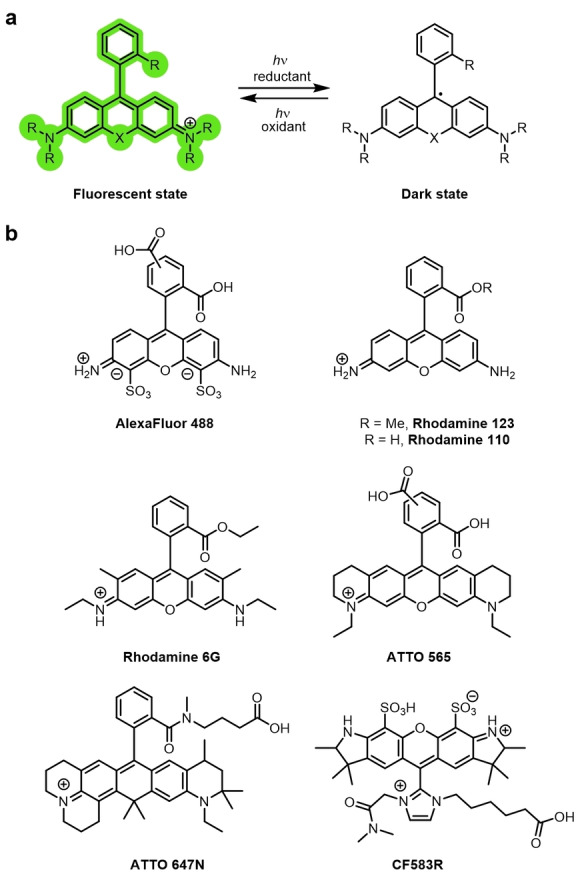

Many commercially available rhodamine dyes, for example, AF488, rhodamine 123, rhodamine 6G, ATTO 488, ATTO 565, and ATTO 647N exhibit photoswitching in deoxygenated buffers and reductive additives, analogous to cyanines (Figure 9a,b).[ 22c , 22d , 71 ] However, the non‐emissive state after photoswitching has been demonstrated to be a long‐lived radical.[ 71b , 72 ]

Figure 9.

a) The reduction of rhodamine to form a long‐lived non‐emissive radical. b) Examples of rhodamine dyes that photoswitch in this manner.

The lifetime of this radical can be several hours at room temperature in the presence of high concentrations of thiol reductant. [71b] This direct photoswitching requires intense laser irradiation to switch to the non‐emissive state. The non‐emissive radical species is formed by reduction of the triplet excited state by the thiol additive, or another reductant. [71b] Irradiation, typically with UV light, reverts the non‐emissive radical form to the fluorescent form, as will oxidation.

Rhodamines can also photoswitch in the presence of oxygen and within the intracellular environment. For example, rhodamine 110 and TMR, coupled to SNAP‐tag ligands were able to photoswitch in the presence of oxygen and with intracellular GSH as the reductant. This allowed them to be used in live‐cell dSTORM imaging experiments. [73] Xu and co‐workers reported rhodamine dyes where the phenyl ring was substituted with a charged imidazolium group, which stabilized the radical species. In addition to increasing the photoswitching propensity, this work demonstrated that these photoswitching mechanisms can be extended to green‐absorbing fluorophores. [74]

3.3.1.2.2. Photochromic Photoswitching in Rhodamines

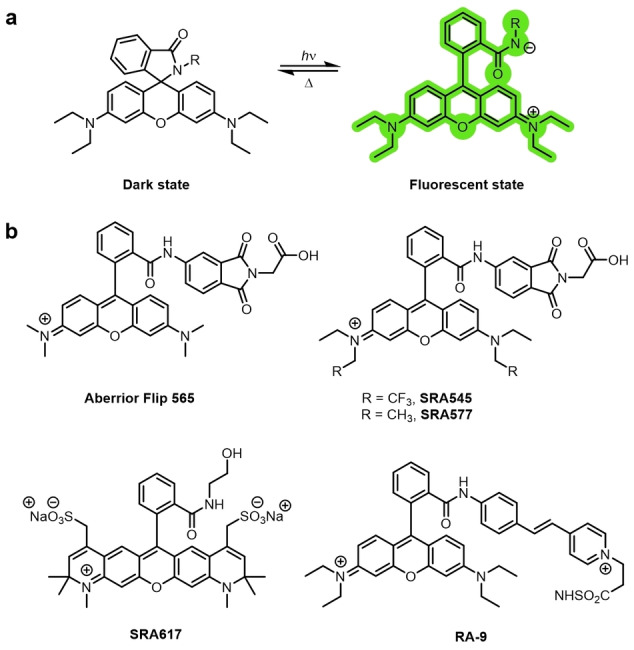

Another mechanism through which rhodamines can be photoswitched is by exploitation of spirocyclization. The closed spirolactone form is nonfluorescent, as the conjugation of the xanthene is disrupted. Upon ring opening, the strongly emissive conjugated system is restored (Figure 10a). [75] Ring opening is, therefore, fluorogenic: there is virtually no background fluorescence, as the ring‐closed spirolactam is non‐emissive and does not absorb in the visible region, with no overlap with the zwitterionic ring‐open form.

Figure 10.

a) Photochromic photoswitching rhodamine‐amides. b) Examples of photochromic rhodamine‐amides.

Spirolactonization is extremely dependent on the environment and pH value: the ring opening generates the emissive form in polar environments and at low pH values. Environment‐dependent ring opening results in fluorogenicity and is taken advantage of in live‐cell, no‐wash microscopy. In the parent rhodamine scaffold, the intramolecular nucleophile is a carboxy group, but this can be changed to alter the equilibrium between the open and closed forms. Rhodamine amides, which form a spirolactam, have found extensive use as fluorogenic sensors by exploiting the ring‐opening mechanism upon interaction with an analyte. [76] They are particularly useful analogues, as their photochromic behavior is well‐established. [77] Photoswitching between the closed spirolactam and open highly emissive form can be controlled. [78] Rhodamine amides are initially closed and excitation with UV light, or two‐photon excitation, [79] leads to ring opening. [80] Reversion to the closed isomer by nucleophilic attack of the amide nitrogen atom on the xanthene ring then occurs spontaneously in the ground state due to thermal relaxation, as this is the more thermodynamically stable conformer. However, as with carboxy‐rhodamines, this reaction is highly dependent on the environment.

The quantum yield of the ring‐opening reaction is low, [77a] but is sufficient for sparse populations of emissive molecules to be generated, which is beneficial for super‐resolution imaging. Aromatic groups at the spiroamide increased the efficiency of the light‐induced ring opening by stabilizing the charge and weakening the C−N bond.[ 78 , 79 ] The Aberrior‐FLIP dye Aberrior Flip 565 uses this mechanism (Figure 10b). The same modifications that have been made to the rhodamine scaffold to expand the range of emission wavelengths available can also be applied to design rhodamine spiroamides with various emissions. [81] This enables multicolor super‐resolution imaging using various rhodamine spiroamides.[ 81a , 82 ] For example, SRA545, SRA577, and SRA617 were used in three‐color imaging. Moerner and co‐workers, by extension of the conjugated system at the lactam nitrogen atom to generate RA‐9, lowered the energy of irradiation required for photoswitching from UV to visible light. [78]

A significant disadvantage of rhodamine amides is that they ring‐open under acidic conditions. Rhodamine amides cannot be used at acidic pH values of pH<5.5 as the equilibrium for the cyclization is pushed towards the open fluorescent isomer and they no longer photochromically switch. Installing a hydrogen‐bond donor that stabilizes the spirolactam has been demonstrated to make the rhodamine ring close even under acidic conditions, whilst shortening the time the rhodamine spends in the emissive state. [83] Extension of the “on‐time” of photochromic rhodamines by stabilizing the zwitterionic ring‐open form with a carboxy group resulted in a larger number of total collected photons before photobleaching. [84] Increasing the nucleophilicity of the amine that forms the spirolactam can be used to shift the equilibrium further towards the closed form. [85] This tunes the equilibrium constant of the intramolecular spirocyclization, pK cycl (the pH value where the open and closed forms are in equilibrium), and enhances the fluorogenicity and membrane permeability.

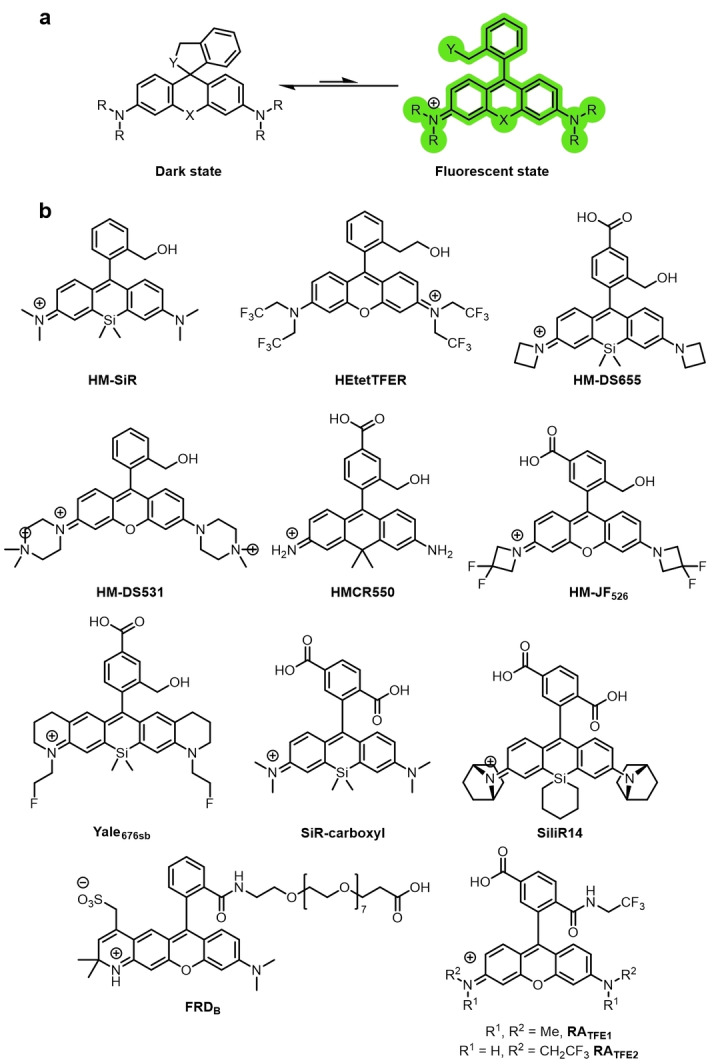

3.3.1.2.3. Spontaneous Switching in Rhodamines

For a spontaneously blinking rhodamine to be applicable for super‐resolution imaging, only a small subset of molecules can be in the ring‐open emissive form at physiological pH values (Figure 11a). [86] The pK cycl value must, therefore, be appropriate and the lifetime of the emissive form—namely, the time taken to revert from the open to the closed form—must be sufficiently short to ensure the majority of the molecules are in the non‐emissive state for SMLM imaging. Replacing the carboxy group by a hydroxymethyl group greatly increases the nucleophilicity. [87] This increased nucleophilicity shifts the equilibrium towards the closed spirocyclic form and can be exploited to design spontaneously blinking rhodamines.

Figure 11.

a) A spontaneously blinking rhodamine with an intramolecular nucleophile (Y) that switches between the stochastically temporarily formed ring‐open emissive form and the non‐emissive ring‐closed spirocycle. b) Examples of spontaneously blinking rhodamines used in super‐resolution imaging.

The first spontaneously blinking fluorophore HMSiR was reported by Urano and co‐workers (Figure 11b). [86] They investigated aminomethyl, mercaptomethyl, as well as hydroxymethyl groups on various rhodamine‐derived fluorophore scaffolds. The ring‐open lifetimes of the mercaptomethyl‐substituted rhodamines were too short, and the compounds remained in the ring‐closed colorless form at pH 2–11, due to the highly nucleophilic nature of the thiol groups. Similarly, the open‐form lifetimes of the aminomethyl derivatives were too short. As a result, the number of photons detected during the lifetime of the ring‐open emissive form were insufficient for SMLM experiments. The ring‐open forms of the rhodamines substituted with hydroxymethyl groups were long‐lived enough to detect sufficient photons for super‐resolution imaging. HMSiR was the first example of a spontaneously blinking fluorophore that blinks in the ground state in aqueous solution.

Spontaneously blinking fluorophores require no buffer additives, and they demonstrate instant blinking during SMLM imaging. The kinetics of the spontaneous blinking are controlled by the pH value of the buffer, according to the pK cycl value, and is unaffected by the intensity of the laser. HMSiR can achieve comparable spatiotemporal resolution with other probes that have been used in conventional SMLM imaging, but as a result of the spontaneity of the photoswitching, the laser power required is orders of magnitude less (40 W cm−2 compared to ca. 1000 W cm−2). [86] HMSiR has allowed minimally invasive single‐color super‐resolution imaging in live cells, [88] and even whole brain imaging of D. melanogaster. [89] Tetrazine‐functionalized analogues of HMSiR, f‐HM‐SiR, [90] and a structurally similar sb‐HD656 have been reported. [91] In both cases, the tetrazine enables biorthogonal click chemistry for site‐specific labeling, and quenches the fluorescence emission until the cycloaddition takes place. This results in fluorogenic fluorophores that also spontaneously blink upon labeling. A combination of photochromic Aberrior FLIP‐565 and spontaneously blinking f‐HM‐SiR has been used for 3D single‐cell multicolor super‐resolution microscopy. [92]

The first green emitting spontaneously blinking fluorophore was hydroxymethylrhodamine HEtetTFER (Figure 11b). [93] This allows for well‐resolved multicolor imaging using both HMSiR and HEtetTFER. However, HEtetTFER is not able to be used in live‐cell SMLM imaging, possibly because of unfavorable subcellular localization and poor membrane permeability. Liu and co‐workers identified that the calculated energy difference between the open zwitterion and the ring‐closed spirocycle linearly correlates with the measured pK cycl values. [94] The authors used this approach to synthesize HM‐DS655 and HM‐DS531 (Figure 11b). Both scaffolds displayed spontaneous blinking and excellent photostability, and HM‐DS655 was used in 3D‐STORM SMLM imaging experiments. [94] The positively charged HM‐DS531 displayed poor membrane permeability, which precluded its use in live‐cell imaging but was successfully employed for the super‐resolution imaging of polymers. [94]

Changes to the xanthene core of rhodamines or the substituents can alter the photoswitching behavior, as the electrophilicity of the xanthene core influences the pK cycl value. [95] Various modifications, where the bridging oxygen atom of the rhodamine scaffold is substituted, have increased the range of emission wavelengths available. [96] Several of these modifications have also been used to access spontaneously blinking fluorophores. Silicon‐bridged rhodamine analogues have lower pK cycl values than the corresponding O‐bridged rhodamines, as the LUMO is stabilized by the silicon atom. [97] This means spontaneous blinking is possible, even when the intramolecular nucleophile remains a carboxy group. [98] Silicon‐rhodamine (SiR‐carboxyl, Figure 11b) was used in super‐resolution imaging (STORM/GSDIM). [99] Iwanaga and co‐workers reported that changing the functionalization on the Si atom from dimethyl to a cyclic silanyl further increases the electrophilicity of the xanthene core. [98] This increases the likelihood of spirocyclization and results in a lower on/off ratio. They also further modified the rhodamine scaffold by changing the amino auxochrome groups to give a 7‐azabicyclo[2.2.1]heptane substituted analogue, SiliR14 (Figure 11b), which showed superior photostability and spontaneous blinking properties. Silanyl‐substituted fluorescein SiliF was also synthesized, which allowed the authors to perform dual‐color SMLM imaging. [98] Urano and co‐workers used a quantum‐chemical calculation and rational design approach to design and synthesize a carbon‐bridged rhodamine derivative HMCR550 that spontaneously blinks. [100] This method allows the blinking properties of a candidate fluorophore to be predicted, without the need to synthesize a variety of potential structures and obtain experimental measurements.

Modifications to the amino auxochromes can also modify the electrophilicity and hence the pK cycl value. Fluorination of the alkyl groups on the nitrogen atoms can increase the brightness and photostability of rhodamine derivatives. [101] 3,3‐Difluoroazetidine was incorporated into a HM‐rhodamine scaffold to afford the spontaneously blinking HM‐JF526 (Figure 11b). [102] Incorporation of a monofluorinated ethylamine in a rigidified tetrahydroquinoline rhodamine gave spontaneously blinking NIR Yale676sb (Figure 11b) with a high QY for a silicon rhodamine (Yale676sb 0.59; azetidine HM‐DS655 0.32). [103] The spectral separation was sufficient to allow multicolor imaging in parallel with HMSiR. Another analogue, Cal664sb, was reported but not used in imaging experiments, as the spectral overlap with HMSiR prevented two‐color imaging. [103]

However, because of the pH dependency of the spontaneous blinking, this category of rhodamines cannot be used in acidic intracellular organelles or compartments, akin to the rhodamine amides. Some rhodamine amide derivatives, as well as exhibiting photochromic photoswitching, have also been reported to spontaneously blink.[ 81b , 85 , 104 ] FRDB, RATFE (Figure 11b), and Abberior FLIP 565 (Figure 10) have all been demonstrated to show spontaneous blinking. Rhodamines can also be modified to blink upon intermolecular nucleophilic addition. Removal of the phenyl group results in a pyronine and the pyronine derivatives can blink upon nucleophilic addition of intracellular endogenous GSH (Figure 12a). [105]

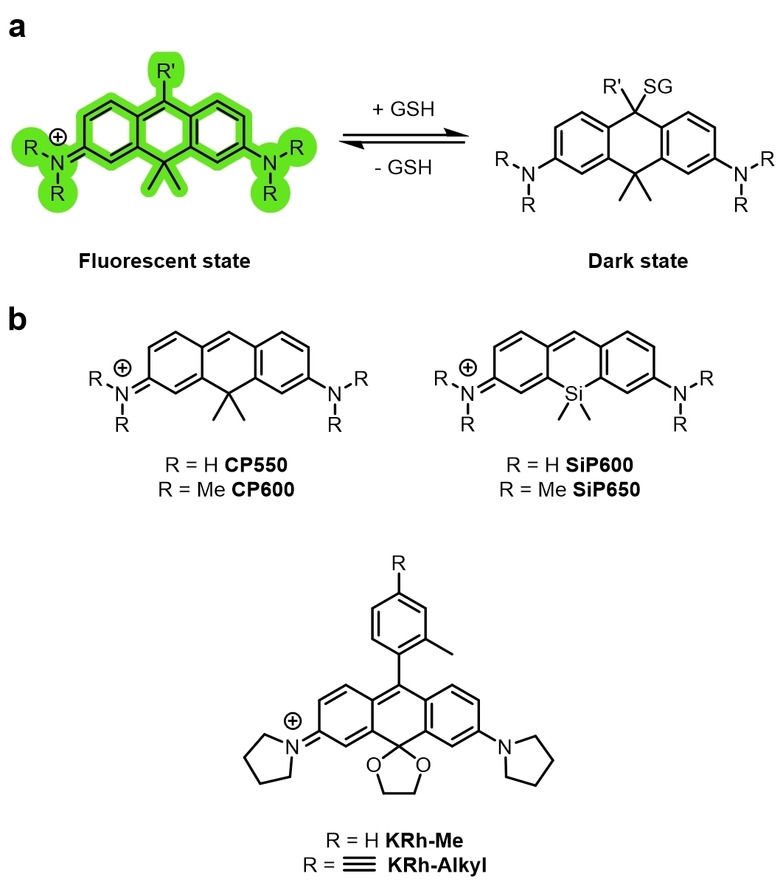

Figure 12.

a) A pyronine dye that spontaneously blinks as a result of the reversible intermolecular nucleophilic addition of GSH (or biological thiols) to form a nonfluorescent adduct. b) Examples of spontaneously blinking pyronine dyes used for super‐resolution imaging.

Carbon‐bridged CP550 and a silicon‐bridged SiP650 were designed with equilibrium constants between the fluorescent and GSH adduct dark states that allowed SMLM multicolor imaging. These dyes could be conjugated to the HaloTag ligand and used for specific target labeling. Inclusion of a cyclic ketal on the rhodamine core gave a NIR rhodamine KRh‐Me (Figure 12b) that was photoswitchable through nucleophilic addition at the same position. [106] A derivative with an alkyne KRh‐Alkyl (Figure 12b) was also synthesized to allow incorporation of targeting groups through CuAAC click reactions.

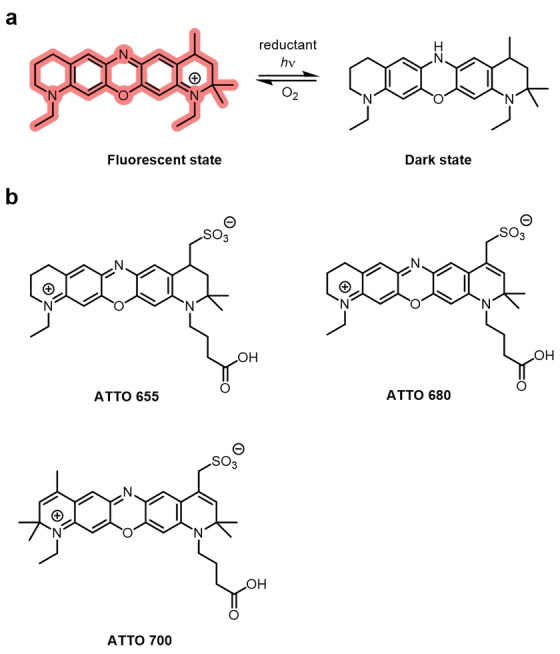

3.3.1.3. Oxazines

Oxazines, including the commercially available ATTO655, can photoswitch through an additional mechanism. The structure of the photoswitched dark species was shown to be the fully reduced and protonated oxazine (Figure 13). [107] Importantly, oxazines can photoswitch in the presence of oxygen with low concentrations of reductant and in live cells.[ 20b , 22d ] Oxazines are also often more photostable than other families of fluorophores in the presence of oxygen. They have a relatively high oxidation potential and low triplet‐state quantum yield, so are not efficiently oxidized by molecular oxygen, which results in decreased photobleaching. [108] The semireduced radical of ATTO655 is unlikely to be oxidized by molecular oxygen and, therefore, a second reduction to the fully reduced form is likely. [71b] The reduced state is thermally stable, persists in oxygen‐free environments, and molecular oxygen is a suitable oxidant to oxidize it back to the ground state. ATTO655 displays photoswitching with on and off times of milliseconds. [108] However, this is very sensitive to oxygen concentration and can be adjusted by variation of the reductant and oxidant. ATTO655 is capable of photoswitching over several thousand cycles before irreversible photobleaching takes place.

Figure 13.

Oxazine photoswitching and examples of fluorophores a) Schematic of photoswitching mechanism of oxazines. ATTO 655. The dark state is the fully reduced, protonated species which can be oxidized by molecular oxygen back to the fluorescent on‐state. b) Examples of oxazine dyes used in super‐resolution imaging.

Oxazines can display photoswitching in live cells, without exogenous reductants. For example, a targeted ATTO655 (Figure 13b), when conjugated to a histone ligand, was used for dSTORM imaging in live cells using endogenous reductants. [109] ATTO520, ATTO680, and ATTO700 (Figure 13b) are all oxazines that photoswitch in the same manner. [110] They can be used in multicolor super‐resolution imaging because of the spectral resolution.

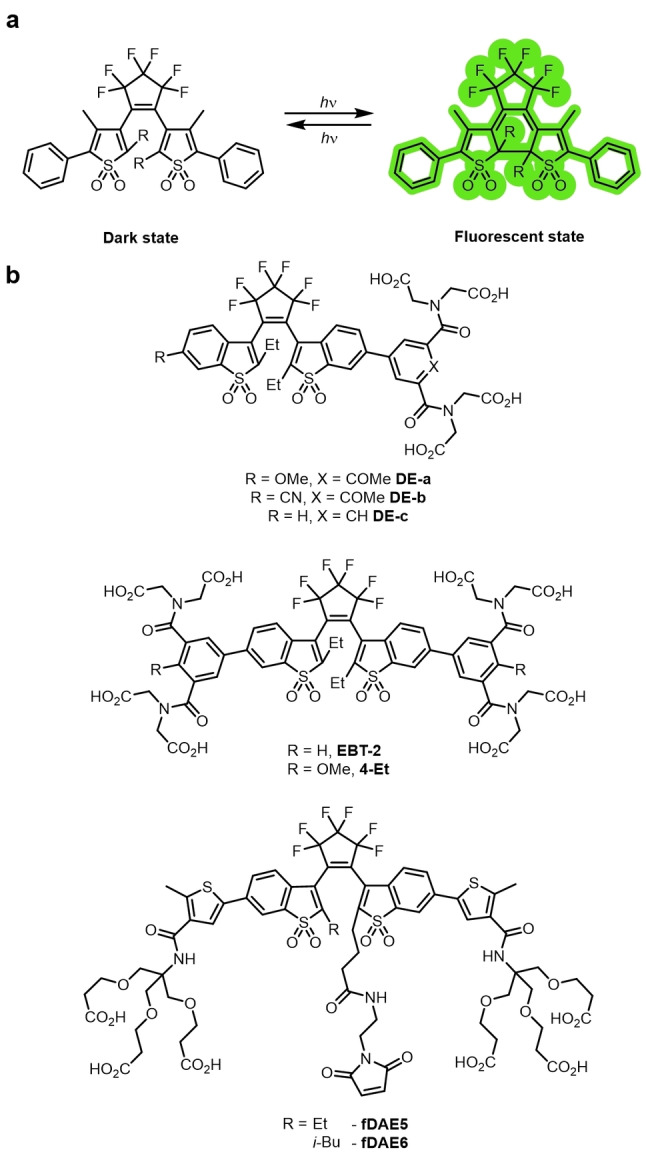

3.3.1.4. Diarylethenes

Diarylethenes have long been studied as photochromic molecular switches. [111] They exist as either an “open” or “closed” isomer. Excitation with UV light leads to the formation of the “closed” isomer. Irradiation of the “closed” isomer with visible light enables switching back to the “open” isomer. They are thermally irreversible photochromic compounds (Figure 14a). [112] Both forms are thermally stable (closed form t 1/2=4.7×105 years at 30 °C), [113] and their absorptions are well‐resolved. The open form displays no absorbance in the visible region. This means irradiation at two separate wavelengths will result in full conversion to each isomer. [114] Nonfluorescent diarylethenes are commonly utilized as organic photoswitches in data storage and sensing. [114] The reversible switching also has a very high resistance to fatigue: [115] 104 cycles of photoswitching are possible, [116] but this is usually much lower in aqueous solvents. The photoswitching process for diarylethenes is both well‐understood and easily controlled, which is not the case for many classes of photoswitchable fluorophores.

Figure 14.

a) The photochromic photoswitching mechanism of diarylethenes. The ring‐open isomer is converted into the ring‐closed isomer by irradiation and vice versa. Both isomers are thermally stable. b) Examples of diarylethene dyes used in super‐resolution imaging.

Fluorescent diarylethene derivatives, with the combination of photochromism and fluorescence switching in one molecule, are therefore attractive candidates for super‐resolution fluorophores. These are typically highly emissive in the “closed” isomer and non‐emissive in the “open” isomer. [117] Single‐molecule photoswitching of diarylethene established unequivocally that the fluorescence switching is through photochromism. [118] The fluorogenicity of this photochromic switching minimizes the background and allows diarylethene derivatives to be used for super‐resolution imaging. They also have large Stokes shifts (ca. 100 nm), which is rare for fluorophores employed in super‐resolution techniques. [119] The energy requirement for the photoswitching reaction is high, usually requiring UV irradiation. The groups of Hell and Irie have developed dyes that photoswitch with a single wavelength of visible light. [120] The incorporation of sulfones into the benzothiophene units both lowered the energy of photoswitching [120a] and increased the resistance to photo‐fatigue. [121]

The incorporation of handles for biorthogonal chemistry or bioconjugation to the diarylethene scaffolds can also be difficult, requiring lengthy bespoke syntheses. Studies by Hell and co‐workers have greatly enhanced the utility of this class of photoswitchable fluorophore for imaging. Firstly, they reported derivatives with carboxylate groups for biolabeling: DE‐a, DE‐b, DE‐C, EBT‐2, and 4‐Et (Figure 14b).[ 119 , 122 ] Bright orange and red emissive analogues fDAE5 and fDAE6 incorporated a maleimide for facile bioconjugation and could be photoswitched using low‐energy visible light (both a 532 nm and 561 nm laser were able to induce photoswitching). [120b] Nanobodies were conjugated to the dyes, and they were used for the super‐resolution imaging of vimentin filaments. These probes represent ideal candidates for use in MINFLUX (MINimal photon FLUX) nanoscopy. [123]

Diarylethene has been incorporated in the design of probes that are photoswitchable through aggregation induced emission (AIE). [124] Several AIE probes have been used for various super‐resolution imaging techniques, which is outside the scope of this Review, but have been reviewed thoroughly by Tang and co‐workers. [124]

3.3.1.5. Other Dye Families

In addition to the dye classes described above, other families of dyes have been shown to be photoswitchable. For example, BODIPYs have been used both as photoactivatable [125] and photoswitching probes.[ 61b , 62 ] A BODIPY with an electrophilic cyano‐acrylate group has been used for super‐resolution imaging by exploiting the stochastic reaction with intracellular nucleophiles to form a short‐lived fluorescent conjugate. [126] PicoGreen, a commercially available DNA probe, can photoswitch and has been used in live‐cell dSTORM imaging. [127] The mechanisms by which these probes photoswitch have not yet been elucidated.

3.3.2. Activator–Reporter Dyads

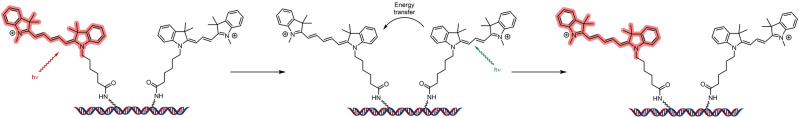

Activator–reporter dyads comprise of an activator chromophore, typically a fluorophore, in proximity to a reporter fluorophore (Figures 7d and 15). The reporter fluorophore is excitation‐saturated through continuous and intense laser irradiation, which drives the molecules to the dark state. The fluorophore is then switched back to the emissive state using irradiation that corresponds to the absorption (or excitation) of the activator chromophore in a transfer of energy (Figure 7d). Energy transfer for photoswitching requires distances of <3 nm. This distance dependency is much steeper than that observed in FRET. [128] The spectral overlap required for FRET is also not necessary, so activators with differing activation wavelengths can be used, allowing many combinations of activator–reporter pairs. Multiple pairs can be used in parallel, thereby enabling multicolor imaging by selective activation using various wavelengths of illumination. [129]

Figure 15.

Schematic representation of an activator–reporter dyad consisting of Cy3 (activator) and Cy5 (reporter) used in the seminal report of STORM imaging. [26]

In the first demonstration of activator–reporter photoswitching, Cy3 and Cy5 were conjugated to DNA and used as an activator–receptor dyad in STORM (Figure 15), where hundreds of photoswitching cycles could take place before photobleaching. [19] Multicolor imaging was made possible using this approach. Cy5, Cy5.5, or Cy7 were switched to a dark state by a red laser (657 nm). A short pulse from a green laser (532 nm) was used to reactivate the emissive state of the reporter cyanine; without a proximal Cy3 this reactivation was undetectable. [130] The Cy5 dark state, now known to be a Cy5‐thiol adduct, has a broadened absorption spectrum that allows overlap of the blue‐shifted emission from the activator fluorophore to recover the fluorescent form of the Cy5 reporter, likely through a combination of Förster and Dexter energy transfer mechanisms. [28b] By varying the activator absorbance through use of either AF405, Cy2, or Cy3, the reactivation of the reporter emission can be stimulated by light of λ=405 nm, 457 nm, or 532 nm with high specificity. [130] 3D STORM imaging was also first realized using activator–reporter dyads. [131]

Typically the activator and reporter would be proximal through conjugation to DNA[ 19 , 132 ] or antibodies.[ 130 , 131 , 133 ] Activator–reporter photoswitching is often used for immunofluorescence imaging. Cy3 and AF647 have been conjugated to ligands that bind to sites in proximity to enable photoswitching. [134] However, this still requires probabilistic proximity. Covalently linked activator–reporter dyads have been reported, which ensures they are in sufficient proximity for photoswitching to take place. [135] The resolution can be tuned by varying the number of acceptor fluorophores and, therefore, altering the ratio of activator to reporter. [132b] Photoswitches can be designed with various acceptor and reporter pairs. For example, oxazine‐based ATTO655 has also been used as a reporter fluorophore with Cy3 as the activator. [136] Rhodamine‐based JFX650 and JF549 have been reported in a system where the reporter JFX650 can be activated by irradiation of JF549. [137] Interestingly, this proximity‐assisted photoactivation (PAPA) does not have the same stringent proximity requirements of the cyanine‐based dyads and was active over a distance where FRET was undetectable.

Despite the seminal report of STORM, [19] activator–reporter dyads have significant drawbacks which have resulted in dSTORM becoming the more powerful and more widely adopted technique. [138] STORM requires the synthesis of the activator, reporter, a linker, and/or conjugation to a scaffold for appropriate spacing with an optimized ratio of activator to reporter. In dSTORM, conventional photoswitching probes can be utilized. [20b]

Multicolor STORM imaging, although possible, [130] is difficult. Activation errors occur as reporter fluorophores can be activated by the undesired activator, or directly unintentionally switched from the dark state by the excitation lasers. [139] The continuing development of photoswitching fluorophores with reliably controlled photoswitching and spectrally resolved excitation and emission wavelengths will be advantageous for multicolor dSTORM.

3.3.3. Photochromic Quencher–Reporter Dyads

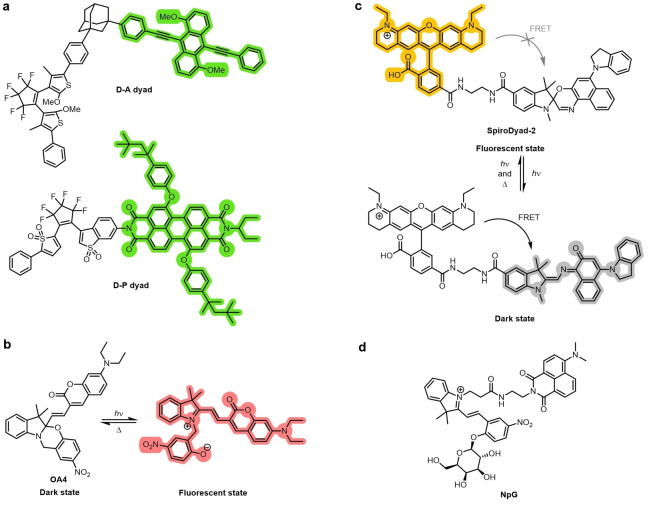

Photochromic quencher–reporter dyads are systems that consist of a photochromic unit and a fluorophore unit either covalently linked or in proximity (Figure 7e). They are analogous to activator–reporter dyads, but in place of an activator there is a photochromic quencher. The photochromic unit can be reversibly switched between an active quenching form and a deactivated non‐quenching form. Energy‐ or electron‐transfer processes are responsible for the quenching of the fluorophore unit. This strategy allows highly efficient and controllable photoswitching.

Photochromic diarylethenes are often used as the activatable quencher and are covalently linked to a fluorophore. The anthracene D‐A dyad and perylene D‐P dyad are two examples of such systems (Figure 16a).[ 118 , 140 ] Spiropyrans and spirooxazines are a class of spirocyclic compounds that have been studied as photochromic molecular switches. [141] Irradiation with near‐UV light generates the ring‐open isomer, which is emissive. [142] The ring‐closing reaction is then typically thermal. Their inherent photochromic behavior and ability to generate a switching dyad when coupled to a fluorophore has made them attractive scaffolds for the generation of analogues for super‐resolution imaging. Derivatives often exhibit weak fluorescence emission, [143] but can be covalently bonded to a fluorophore to make a fluorescent switch, as in OA4 (Figure 16b).[ 142a , 144 ] They can also be used as a photochromic quencher, operating by FRET, as in SpiroDyad‐2 (Figure 16c). [145] A spiropyran scaffold was used to develop the β‐galactosidase‐responsive sensor NpG (Figure 16d), which is used in STORM imaging in various cancer cell lines. [146] Acylhydrazones have also been reported in photochromic switches. [147] In combination with peptide targeting groups, this class of photochromic switch was used in dSTORM and PALM imaging of amyloid nanofibrils. [147]

Figure 16.

a) Photochromic diarylethene quencher dyads D‐A and D‐P. The fluorescence of the anthracene and perylene fluorophores is quenched when the diarylethene groups are switched to the closed isomer. b) The spiropyran photochromic dye OA‐4 containing a conjugated coumarin. c) Spirooxazine‐rhodamine dyad SpiroDyad‐2. Upon opening of the closed spirocycle to give the merocyanine, the fluorescence of the rhodamine group is quenched. d) Spiropyran‐naphthalimide‐based dye NpG. Upon reaction with β‐galactosidase, the photochromic switching of the spiropyran is restored.

4. Improving Fluorophores for SMLM

The ideal probe for live‐cell SMLM is controllably and reversibly photoswitched; has a completely non‐emissive off state (or fully spectrally resolvable) to ensure no background; has long‐wavelength excitation and emission; is bright, photostable, and cell permeable; and contains an appropriate handle for labeling.

Cyanines and rhodamines, with their extremely large extinction coefficients and high quantum efficiencies, are the scaffolds of choice and are widely used in bioimaging. Discoveries that increase the brightness and photostability of both these classes of fluorophore are pivotal to improving their performance in all kinds of fluorescence imaging, especially super‐resolution techniques. [148] The use of deuterated solvents, such as heavy water for fluorescence studies of oxazines [149] and cyanines, [150] has been shown to increase the quantum yield, which in turn increases the number of photons actually emitted at the single‐molecule level. The use of deuterated buffers for cell imaging is not a viable approach; however, the deuteration of fluorophores at the auxochrome or proximal sites has been shown to reduce the rate of photobleaching. [151]

Modification of the auxochrome groups is a synthetically feasible strategy to increasing brightness, particularly in rhodamine derivatives. A general method utilized to improve the brightness for multiple fluorophore families is to replace the auxochromes with azetidine. This small modification leads to greatly increased quantum yields, which improves the properties of the fluorophore for super‐resolution imaging.[ 95 , 152 ] This work has led to various amines being incorporated into rhodamine derivatives to increase brightness. For example, quaternary piperazine‐substituted derivatives displayed improved blinking and quantum yields, thus improving their performance in SMLM imaging. [153] Several other modifications have also been used to decrease intramolecular rotation to increase the brightness, by reducing nonradiative decay. Electron‐withdrawing fluorine atoms on the auxochrome improves photostability, increases quantum yield, and lowers the pK cycl value.[ 81c , 101 , 102 , 103 ]

For photoswitching dyes, the lifetime of the non‐emissive state should be long enough (duty cycle between 10−4 and 10−6) to ensure low numbers of fluorophores are in the emissive state simultaneously, thereby allowing them to be distinguished. Alternatively, the lifetime of the emissive state can be shortened. Increasing the photostability and reducing the propensity for photobleaching is paramount for improving dyes for super‐resolution imaging. Several methods have been used for this purpose. Modifications to the structure of the dye are the most common. Many of the structural modifications to the auxochromes mentioned in Section 3.3, including azetidine and fluorinated amines, increase the photostability as well as tune the emission properties. Adding electron‐withdrawing substituents can lower the LUMO energy and the energy of the triplet state. For example, fluorination of the fluorophore scaffold has been employed as a general strategy. Polyfluorination of the cyanine scaffold while greatly reducing the photobleaching also leads to a significant reduction in brightness. [154] Sulfonates or phosphonates have also been used but, due to the negative charge at physiological pH values, also reduces the membrane permeability. [155]

The non‐emissive state is often a reactive radical species; therefore, any stabilization of the non‐emissive state will reduce the likelihood of side reactions and improve the photostability. A major pathway for photobleaching proceeds via the triplet state. A long‐lived triplet state is desirable for photoswitching, but can increase the propensity for photobleaching. This will increase the frequency of sensitization of 3O2 to generate more 1O2. The reaction with 1O2 is a major photobleaching pathway. Removal of oxygen, usually by enzymatic scavenging, is a prerequisite for most SMLM fluorophores. Some dyes, such as ATTO 655, photoswitch well in the presence of oxygen. The further development of dyes that can tolerate the presence of oxygen will be advantageous.

Self‐healing dyes comprise a fluorophore and a photostabilizing group that can help prevent photobleaching by intramolecular interactions. [156] This is often achieved by attachment of a triplet state quencher, commonly cyclooctatetraene (COT), [157] by a covalent linker. This can greatly increase the photostability of cyanines. [158] Self‐healing dyes often perform less efficiently than the corresponding dye and additive in solution. [156] Synthetic tuning of the COT triplet state by inclusion of an amide can significantly improve the self‐healing performance of cyanine‐COT conjugates. [159] Although this strategy prolongs the duration of fluorescence before photobleaching, and can, therefore, improve performance in STED or SIM, it complicates experiments where photoswitching is required. There are limited examples of the application of cyanine‐COT conjugates in STORM imaging and none in live‐cell imaging. [160] Further research is required before the widespread application of such conjugates. Nitrophenylalanine and Trolox have been used in a similar fashion to greatly enhance the photostability but are also not appropriate for photoswitching techniques. [161] Kawai and co‐workers used COT with ATTO 647N to control blinking for imaging the single‐molecule dynamics of biomolecules. [162] Increasing the photostability can enable the number of switching cycles to be increased. This is also highly dependent on buffer composition; therefore, the buffer composition must be carefully optimized for redox‐dependent and redox‐independent photoswitching.

5. Summary and Outlook

A range of photochemical mechanisms, each with its advantages and limitations (Table 1), that enable theswitching of fluorophores between bright and dark states have been investigated. These along with new improvements in optics, breakthroughs in data analysis algorithms, and the use of artificial intelligence continue to push the lateral and axial resolution barriers in imaging. More importantly, existing small organic fluorophores and fluorescent proteins that offer some level of compatibility with distinct super‐resolution imaging methods have spurred the wider adoption of these technologies. However, a major limitation of SMLM techniques is reproducibility. The photoswitching mechanisms used are highly sensitive to the local environment, imaging conditions, and substrate being used. This demands careful consideration and thorough reporting of the acquisition and image‐analysis parameters. Other challenges with SMLM include susceptibility to image reconstruction artefacts (overlapping PSFs, hardware drift, and localization bias), difficulties in imaging thick samples or tissues, low throughput, and limited applicability to live‐cell imaging. Cells and tissue samples are typically fixed for SMLM experiments, nevertheless slow‐moving structures, such as focal adhesions, can be studied using live‐cell SMLM. High laser power is a prerequisite to ensure sufficient populations of fluorophore are switched to the non‐emissive state. This leads to increased photobleaching and cellular damage in live‐cell imaging. Photoswitchable dyes that can be switched with less intense laser power would be of benefit. Alternatives such as photochromic switching with long‐wavelength light and spontaneously blinking fluorophores that inherently do not require high laser intensity mitigate this. Dyes, where there is complete control over the switching between off and on states, are optimal as this gives control over the duty cycle Photochromic fluorophores where the emissive and non‐emissive states are thermally stable, with complete control over the switching process, would be ideal candidates to develop for SMLM applications. Mechanistic understanding of photochemical reactions that lead to the photoconversion of fluorophores is necessary to drive their application in super‐resolution imaging.[ 34 , 163 ] Furthermore, SMLM approaches are typically limited to a few colors, because of the small number of spectrally distinguishable fluorophores available.

Table 1.

Comparison of the photochemical mechanisms exploited in SMLM.

|

Photoswitching mechanism |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Photoconversion |

High S/N due to ca. 100 nm shift in λ em. Photoconversion achieved by visible light. Does not require specialized buffers. |

Photoconversion yield dictates the number of localizations. Overlapping emission spectra of parent and product fluorophores (dealkylation). Has only been used for SMLM with cyanine dyes. |

Only two examples of use in SMLM (dSTORM, DNA‐PAINT). Only cyanines have been successfully used for SMLM. |

|

| |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Photo‐uncaging |

Improves S/N due to fluorescence turn‐on. Tetrazines can also be used for biorthogonal labeling. |

Uncaging usually requires high‐energy UV light. Often releases bioactive by‐products. |

Generally used in conjunction with photoswitching fluorophores as a labeling strategy or to improve S/N. |

|

| |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Photoswitching |

Can be performed using relatively inexpensive, commercially available fluorophores. Fluorophores are easy to conjugate to biological targets. |

Ground‐state recovery is usually stimulated by UV light. Requires oxygen scavenging and thiol or ROXS buffer additives (except for oxazine‐based dyes). |

The most common method of achieving SMLM |

|

| |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Activator–Reporter Dyads |

As a consequence of energy transfer from the reporter, excitation can be performed at almost any wavelength (excitation, emission overlap not necessary). |

Fluorophores must be conjugated to a target (disruption of target properties/function) or covalently linked to each other (more synthetic steps). Reporter fluorophores can be unintentionally switched from the dark state by the excitation laser, or incorrect activator in multi color imaging. Requires <3 nm separation between activator and reporter (except for PAPA). |

Should ideally be no overlap between the reporter and activator emission spectra. |

|

| |||

|

|

|

|

|