Abstract

Death receptor 5 (DR5) is an apoptosis-inducing membrane receptor that mediates cell death in several life-threatening conditions. There is a crucial need for the discovery of DR5 antagonists for the therapeutic intervention of conditions in which the overactivation of DR5 underlies the pathophysiology. DR5 activation mediates cell death in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and neurodegenerative processes including amyloid-beta (Aβ) accumulation, spinal cord injury (SCI), and brain ischemia. In the current work, we used fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) to monitor the conformational dynamics of DR5 that mediate death signaling. We used a time-resolved FRET screening platform to screen the Selleck library of 2863 U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved compounds. The high-throughput screen (HTS) identified 13 compounds that modulated the FRET between DR5 monomers beyond 5 median absolute deviations (MADs) from the DMSO controls. Of these 13 compounds, indirubin was identified to specifically inhibit tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced caspase-8 activity without modulating DR5 surface expression or TRAIL binding. Indirubin inhibited Fas-associated death domain (FADD) oligomerization and increased cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein (c-FLIP) expression; both are molecular mechanisms involved in inhibiting the DR5 signaling cascade. This study has elucidated previously unknown properties of indirubin that make it a promising candidate for therapeutic investigation of diseases in which overactivation of DR5 underlies pathology.

Keywords: death receptor 5, TRAIL, high-throughput screening, indirubin, alkaloid

Introduction

Death receptor 5 (DR5) is an apoptosis-inducing membrane receptor that is part of the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) super family.1 Binding of its native ligand, tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), leads to the activation of caspase-8 and subsequent cell death. While DR5 agonists have been a primary focus in the development of cancer therapeutics,2 the therapeutic relevance of DR5 antagonists has recently gained traction with more research showing a role of this pathway in disease and injury.

TRAIL-induced apoptosis via DR5 mediates neuronal loss in neurodegenerative processes related to amyloid-beta (Aβ) accumulation,3,4 spinal cord injury (SCI),5 and brain ischemia.6 Aβ accumulation contributes to the formation of plaques that are found in the brains of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients, and is associated with neurotoxicity and the progression of disease symptoms.7–10 The contribution of DR5 to AD was initially demonstrated in a study which showed that treatment of SH-SY5Y cells with Aβ resulted in increased TRAIL and DR5 expression, and subsequent cell death.4 This study further demonstrated that Aβ-induced neurotoxicity could be inhibited by sequestering TRAIL using a TRAIL-neutralizing antibody.4 Because TRAIL plays an important role in immune surveillance, researchers took an alternative approach to investigate the role of the TRAIL pathway in Aβ-induced neurotoxicity. In a follow-up study, researchers showed that the blockade of DR5 with an anti-DR5 antibody completely prevented Aβ-induced death in both the SH-SY5Y neuronal cell line and primary cortical neurons,3 highlighting the relevance of DR5 antagonists in neurodegenerative diseases.

The relevance of the DR5 pathway in SCI was established in a study which showed that the expression of TRAIL and DR5, and downstream caspase-8 activity, was significantly increased in mice that have undergone SCI. Treatment of these mice with a TRAIL neutralizing antibody resulted in the improvement of motor activity, and reduced expression of caspase-8, TRAIL, and other pro-apoptotic cytokines.5 The upregulation of TRAIL and DR5 is also present in the postischemic brain of adult rats.6 Neutralization of this pathway prevents tissue damage and results in significant functional improvement.6 In non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), an increase in free fatty acids (FFAs) in the liver induces an increase in DR5 expression in hepatocytes, underlying the increased sensitivity to TRAIL in steatotic hepatocytes.11–13 Altogether, these findings indicate a clear role of the TRAIL-DR5 pathway in several debilitating conditions, and encourage the discovery of DR5 antagonists for the pharmacological intervention of AD, trauma, stroke, and NAFLD.

In order to identify small-molecule modulators of DR5 signaling, we have followed a similar approach to our previously established fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based biosensor for TNFR1, a receptor within the same superfamily.14,15 DR5 signaling is initiated upon the binding of trimeric TRAIL to the extracellular domain of the receptor. Binding of TRAIL to DR5 has been shown to induce the formation of a higher order oligomeric network comprised of a “dimer-of-trimers”.16 Upon this rearrangement, DR5 undergoes a conformational change that we previously showed involves a scissor-like opening of the transmembrane (TM) region, leading to the opening of the intracellular domain and subsequent activation of the receptor.17 A complex convolution of oligomerization and associated conformational dynamics of receptor opening/closing can be detected as a change in FRET (either an increase or decrease), which reflects a distance change between fluorophores. By fusing green fluorescent protein (GFP) and red fluorescent protein (RFP) to the TM domain of separate DR5 monomers absent the intracellular domain (Figure 1A), we have designed a biosensor that provides a lifetime readout (used to calculate FRET) corresponding to conformational dynamics of the DR5 TM domains (Figure 1B). Because receptor conformation is important for activation, we were able to successfully implement this biosensor in a high-throughput screen (HTS) to detect molecules that modulate DR5 conformation, and subsequently, the downstream signaling.

Figure 1.

DR5 biosensor design. (A) Schematic of GFP or RFP-fused DR5ΔCD construct. (B) Lifetime measurements and corresponding FRET efficiency of donor (DR5ΔCD/GFP)—in the presence and absence of acceptor molecule (DR5ΔCD/RFP) (n = 16).

Abbreviations: DR5, death receptor 5; FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer.

In the current work, the biosensor was first optimized for increased throughput to accommodate screening against the Selleck library of 2863 FDA-approved compounds. HTS identified 5 compounds that decreased, and 8 compounds that increased, the biosensor lifetime beyond 5 median absolute deviations (MADs) from the untreated conditions. Of these compounds, indirubin specifically inhibited TRAIL-induced caspase-8 activity in a dose-dependent manner. The cytotoxicity of indirubin was assayed in Jurkat cells. Indirubin was not cytotoxic to Jurkat cells at concentrations of 200 μM and below. DR5 surface expression and TRAIL binding was assayed in Jurkat cells using flow cytometry. Indirubin did not modulate DR5 surface expression or TRAIL binding, which is important for maintaining physiological homeostasis of these immune proteins. Indirubin decreased FADD oligomerization and increased c-FLIP expression, which are both molecular mechanisms involved in the inhibition of DR5-mediated caspase-8 activity. These results suggest that indirubin is a promising compound for the therapeutic intervention of neurodegenerative disorders and NAFLD via inhibition of DR5.

Results and Discussion

Discovery of Small Molecules That Modulate DR5 Dynamics: HTS of Selleck Library

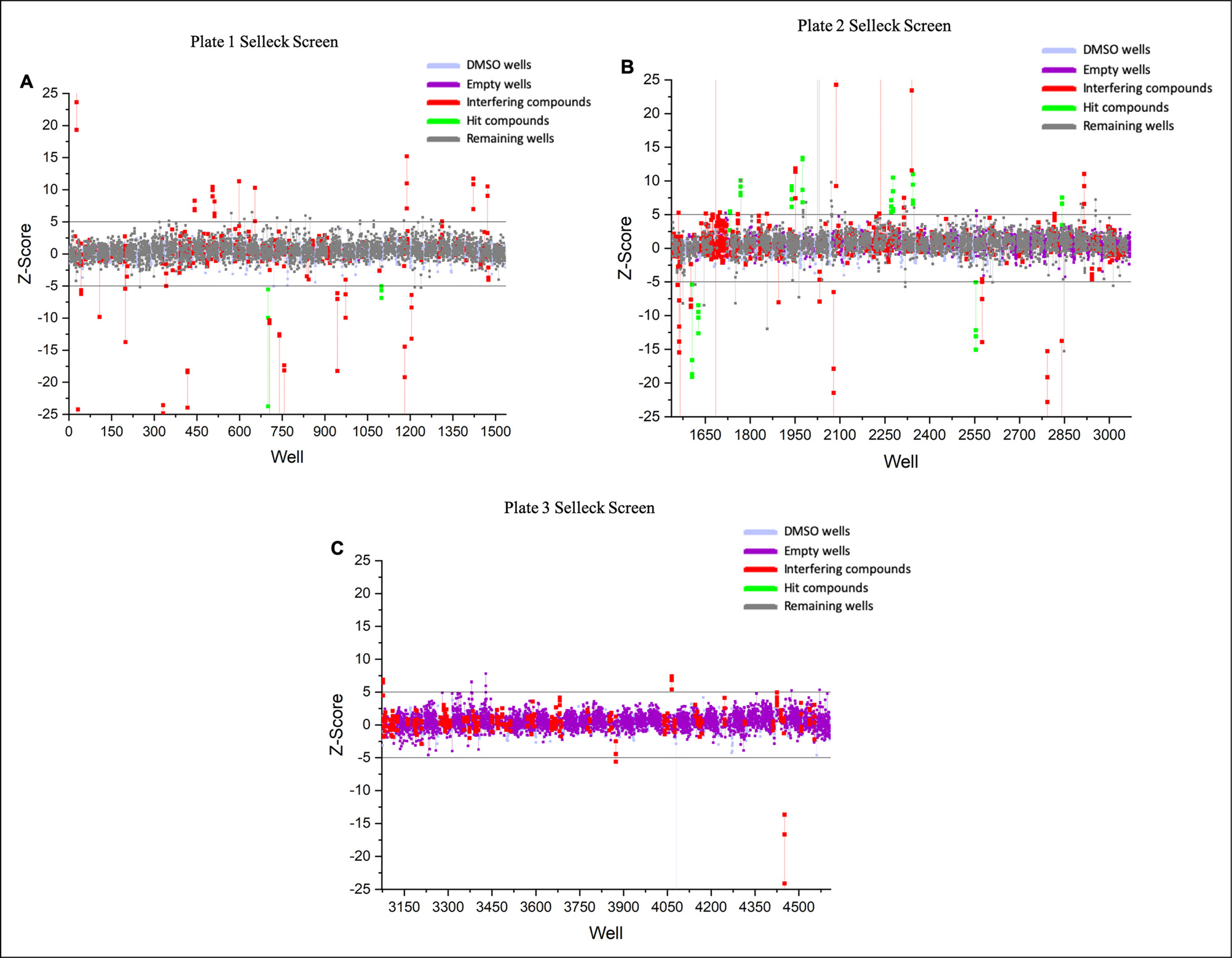

HTS of the Selleck library was performed to identify compounds that modulate DR5 dynamics using the DR5 biosensor. On the day of screening, the DR5 biosensor FRET efficiency was validated using a fluorescence lifetime plate reader (FLTPR), provided by Photonic Pharma LLC (Minneapolis, MN).18 Next, cells expressing the biosensor were dispensed into drug plates and incubated with the compounds (10 μM) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) controls for 2 h at room temperature. Lifetime measurements were then acquired using the FLTPR. A single-exponential fit was used to determine the lifetime from cells expressing the DR5-GFP donor-only control or the DR5-GFP-RFP FRET biosensor . Spectral readings were used to flag potential false positives due to interference from intrinsically fluorescent compounds.19 From the Selleck library of compounds distributed over 3 1536 well microplates (Figure 1A,B,C), 13 reproducible hits were identified from the screens (Figure 2). Out of the 13 hits, 8 increased and 5 decreased the lifetime beyond 5 MADs from the median of the DMSO wells (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Selleck screen results. (A) Plate 1. (B) Plate 2. and (C) Plate 3. Screen results are shown in representative Z-score format. Z-score is the number of median absolute deviations (MADs) from the median of the DMSO wells. Hits are defined as those with a Z-score of ± 5 for 3 replicate screens. Each replicate is shown as a single circle and all replicates for a single well are connected with a vertical line. DMSO wells: DMSO treated; Empty wells: No treatment; Interfering compounds: Compounds flagged as fluorescent based on similarity index; Hit compounds: Compounds with triplicate Z-scores beyond 5 MADs of DMSO; Remaining wells: Contained compounds that were not flagged as hits or interfering.

Table 1.

Z-Scores of Hits From Selleck Screen.

| Compound number | Compound name | Average Z-score |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 700 | Indirubin | −13.07 |

| 1099 | Rifampin | −5.86 |

| 1606 | Dracohodin perchlorate | −14.95 |

| 1627 | CP21R7 | −10.23 |

| 1733 | Auranofin | 4.70 |

| 1768 | Saikosaponin D | 8.83 |

| 1939 | Escin | 7.82 |

| 1975 | Pyrrolidine | 10.53 |

| 2271 | Troglitazone | 6.01 |

| 2277 | Olodaterol HCl | 7.57 |

| 2344 | Saikosaponin A | 8.53 |

| 2554 | Sapropterin diHCl | −11.35 |

| 2842 | Triclocarban | 6.05 |

Hits From the Selleck Screen Inhibit Caspase-8 Activation.

Jurkat cells, in the presence and absence of TRAIL, were treated with a titration of each hit in order to determine the effects of the compounds on basal and TRAIL-induced caspase-8 activity. Four hits were able to inhibit caspase-8 activity, however, indirubin was the only compound to specifically inhibit TRAIL-induced caspase-8 activation in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3). The other 3 compounds, saikosaponin D, saikosaponin A, and escin, decreased caspase-8 activity below basal levels, suggesting that they are inhibiting caspase-8 in a TRAIL-independent manner (Supplementary Figure 2). While this work highlights indirubin, the other 3 compounds were also interrogated, and the data is included in the Supplemental Material of this article.

Figure 3.

Indirubin inhibits tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced caspase-8 activity (n = 3). Blue curve = dose response of drug in the presence of 0.1 μg/mL TRAIL. Pink curve = dose response of drug in the absence of TRAIL. Half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values calculated in GraphPad PRISM.

Cytotoxicity of Indirubin to Jurkat Cells.

The cytotoxicity of indirubin was assayed in Jurkat cells. Jurkat cells were plated on day 1, treated with drugs on day 2, and cytotoxicity was assayed on day 3 using the CytoTox-Glo kit (Promega). Indirubin resulted in no significant cell death over the range of drug treatment from 0 to 200 μM (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cytotoxicity of indirubin in Jurkat cells (n = 3). Cytotoxicity of indirubin, assayed using CytoTox-Glo (Promega), displayed no toxicity to Jurkat cells over the range of concentration from 0 to 200 μM. One-way ANOVA performed in PRISM resulted in no significant decrease in cell viability over the titration of indirubin from 0 to 200 μM.

Effect of Indirubin on TRAIL Binding.

It is important to determine whether indirubin interferes with TRAIL binding to DR5, to provide insight on how this drug could modulate physiological levels of TRAIL. Drugs that prevent TRAIL from binding could increase the pool of free TRAIL in the body, and vice versa. This could interfere with the body’s immune surveillance and may cause adverse side effects. It is also important to verify that the decrease in caspase-8 observed in Figure 3 is not coming from an increase in TRAIL binding. The binding of TRAIL in the presence of indirubin was assayed in Jurkat cells at the IC50 of indirubin as determined by the functional assay in Figure 3. Indirubin did not modulate TRAIL binding at its IC50 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Indirubin’s effect on TRAIL binding to Jurkat cells (n = 3). FL4A is the channel through which the fluorescence signal corresponding to TRAIL binding is measured. FL4A fold change is quantified by comparing the median signal intensity on the FL4A gated channel of the treated to untreated cell samples. Data are normalized to the DMSO control to show the change in the FL4A signal for TRAIL binding to cells in the presence of drug. One-way ANOVA performed in GraphPad PRISM.

Abbreviations: TRAIL, tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand; ns, nonsignificant.

Effect of Indirubin on DR5 Expression.

In Figure 6, the effect of indirubin on the surface expression of DR5 was analyzed using flow cytometry on Jurkat cells. It is important to assay for changes in DR5 surface expression because drugs which modulate levels of DR5 surface expression could interfere with the body’s native immune response and death signaling pathways. It is also important to verify that the decrease in caspase-8 observed in Figure 3 is not coming from a decrease in DR5 surface expression. DR5 expression was assayed in Jurkat cells treated with indirubin at its IC50 as determined by the functional assay in Figure 3. Figure 6 shows that indirubin did not modulate DR5 surface expression at its IC50.

Figure 6.

Effect of indirubin on DR5 expression in Jurkat cells. FL4A channel represents the fluorescence signal corresponding to the detection of DR5 surface expression. FL4A fold change is quantified by comparing the median signal intensity on the FL4A gated channel of the treated to untreated cell samples. Data are normalized to the DMSO control to show the fold change in FL4A signal for DR5 expression in the presence of drug. One-way anova performed in GraphPad PRISM.

Abbreviation: DR-5, death receptor 5; ns, nonsignificant.

Effect of Indirubin on Death-Inducing Signaling Complex (DISC) Associated Proteins FADD and c-FLIP.

The effect of indirubin on FADD and c-FLIP expression was interrogated using western blot (Figure 7). Previous research has shown that FADD self-association is crucial for the formation of a competent DISC.20,21 C-FLIP is an inhibitor of apoptosis protein that can compete with procaspase-8 to bind to the death effector domain (DED) of FADD, and inhibit apoptosis.22,23 High expression of c-FLIP has been shown to result in the inhibition of caspase-8 activity whereas downregulation of c-FLIP can relieve caspase-8 suppression and promote apoptosis.22–28 Treatment of Jurkat cells with indirubin at its IC50 displayed a decrease in FADD oligomerization (Figure 7A,C) and an increase in c-FLIP expression (Figure 7B,C). Thus, we propose that by inhibiting FADD oligomerization and increasing c-FLIP expression, indirubin inhibits the formation of an active death signaling complex.

Figure 7.

FADD and c-FLIP western blot analysis. Western blots probing for (A) FADD and (B) c-FLIP in the lysate of Jurkat cells treated with saikosaponin D and indirubin. (C) Quantification of band intensities was done using ImageJ.

Conclusions

This work has identified a small molecule, indirubin, that inhibits TRAIL-induced apoptosis via DR5 with an IC50 of 11.36 ± 3.86 μM. Dose-response data show that the effect of indirubin on Jurkat cells in the presence of TRAIL results in an inhibition of the TRAIL-induced caspase-8 activity down to the basal level of the cells (Figure 3). Although TRAIL can induce caspase-8 activity via DR4, DR4 mRNA and expression is undetectable in Jurkat cells as evidenced by previous studies.29 Because indirubin was identified via a DR5-specific HTS and it inhibits TRAIL-induced caspase-8 activity in a DR4-absent cell line, our results support that the ability of indirubin to inhibit TRAIL-induced caspase-8 activity is DR5-mediated. Indirubin was not cytotoxic from 0 to 200 μM (Figure 4), which is very encouraging of a positive safety profile at its IC50 of 11.36 μM (Figure 3). Indirubin had no effect on TRAIL binding (Figure 5) or DR5 expression (Figure 6) at its IC50, which is important for mitigating off-targets effects due to alteration of immune protein expression. While previous researchers have shown that indirubin derivatives lead to increased surface expression of DR5, these experiments were done on different cell lines, the majority of which are TRAIL resistant, and the derivatives’ effects were attributed to the upregulation of pro-apoptotic BAX and p53, both of which are absent in Jurkat cells.30,31 Thus, the observed effect could be cell dependent and should be further investigated in follow-up studies.

The novelty of the current work warrants further investigation of indirubin’s potential as a multifunctional drug for the treatment of DR5-mediated diseases. Indirubin treatment of Jurkat cells resulted in a decrease of FADD oligomerization and increase in c-FLIP expression (Figure 7). These molecular mechanisms are well-known to inhibit caspase-8 activity. Thus, our work shows that indirubin inhibits TRAIL-induced caspase-8 activity by interrupting the DR5 signaling pathway. While more work is needed to investigate whether indirubin binds to DR5 and whether there is any overlap with other TRAIL pathways, our results set the stage for future research into the therapeutic potential of indirubin to inhibit overactive death receptor-mediated disease states.

Altogether, these results point to indirubin as a promising candidate for further therapeutic investigation because its mechanism of action was specific to TRAIL, it was noncytotoxic, and it did not modulate TRAIL binding or DR5 expression. Indirubin has an established history of medicinal use in humans. It is the active ingredient of Danggui Longhui Wan, a mixture of plants that has been used in traditional Chinese medicine for over 4 millenia.32 Indirubin has been extensively studied for its anti-inflammatory,33 anti-cancer,34 anti-angiogenic,35 and neuroprotective effects.36 However, the ability of indirubin to inhibit TRAIL-induced DR5 activation is a novel finding. Support for the therapeutic potential of indirubin in AD has been previously demonstrated in a different context. Indirubins are potent inhibitors of GSK-3 and CDK5, which are responsible for most of the abnormal hyperphosphorylation of tau in AD.37 A derivative of indirubin, indirubin-3′-monoxime, has been shown to inhibit tau phosphorylation in vitro and in vivo at AD-specific sites.37 This derivative has also rescued Aβ pathology in a mouse model of AD.38 Thus, indirubins are promising compounds that should be further investigated for the treatment of AD based on previous work, and the results in the current work, which encourage further investigation of indirubin’s potential to inhibit Aβ-induced neurotoxicity via DR5, along with its therapeutic potential for stroke, trauma, and NAFLD.

Experimental

Cell Cultures and Reagents

HEK293 cells were cultured in phenol red-free Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (Gibco) supplemented with 2 mM L-Glutamine (Invitrogen). Jurkat cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 with HEPES, sodium pyruvate, and L-glutamine (ATCC). All media was supplemented with heat-inactivated 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin (HyClone). Mammalian cell cultures were maintained in an incubator with 5% CO2 (Forma Series II Water Jacket CO2 Incubator: Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37 °C.

Biosensor Design and Transfection

TagRFP and EGFP plasmids were a gift from David D. Thomas. DNA encoding DR5ΔCD (1–240) was inserted at the N-terminus of the TagRFP and EGFP vectors using standard cloning techniques, as described previously.39 Plasmid backbone shown in Supplementary Figure 6. To prevent the dimerization and aggregation of EGFP, alanine 206 was mutated to lysine (A206K).40 HEK293 cells were plated in a 10 cm plate on day 1 in order to reach a confluence of approximately 70% on day 2. On day 2, the 70% confluent HEK293 cells were co-transfected with DR5ΔCD-GFP and DR5ΔCD-RFP plasmids at a 1:6 ratio for a final mass of 17.5 ug (2.5 ug donor:15 ug acceptor) DNA using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen). Donor-only (DR5ΔCD-GFP) was transfected at 2.5 ug. After 24 h, transfection was confirmed using EVOS fluorescence microscopy (Life Technologies) to visualize fluorescence expression. Once fluorescence is confirmed at the 24 hr time point, cells can be lifted and plated in multi-well plates for screening/optimization.

Optimization of Biosensor into 1536-Well Plate Format

In order to accomodate larger library screening, the biosensor was optimized from 384- to 1536- well format. After confirming fluorescence expression, HEK293 cells expressing the biosensor were harvested from the 10 cm plates by incubating for 2 to 4 min with TrypLE (Invitrogen), washed 3 times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and filtered using 70 μm cell strainers (BD Falcon). The cell solution was then counted using an automated cell counter (Denovix) and diluted into a range of concentrations 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2, 2.5, and 3 million cells/mL. Each cell solution was dispensed (5 μL/well) into 1536-well flat bottom polypropylene black plates, selected for their low autofluorescence and low inter-well cross talk (Greiner Bio-One), by a Multidrop Combi Reagent Dispenser (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The conditions were interrogated to determine which cell density resulted in the optimal signal response within the bounds of the FLTPR. Optimal signal setting was determined as that which gave a readout above the autofluorescence of untransfected cells and within a filter setting of the instrument that allows enough of a window to detect signal modulation due to changes in biosensor lifetime readout under drug treatment.

Tool Compound Validation

HEK293 cells expressing the biosensor at the optimized concentration (2 million cells/mL) were plated into black 1536-well nontreated well plates (Corning) containing a titration of tool compounds identified from a previous screen using this biosensor (Rutaecarpine, Nimesulide, and 6-methyl-2-(phenylethynyl) pyridine hydrochloride [MPEP HCl]).41 HEK293 cells expressing the donor-only were plated at the same concentration without drugs. The cells were incubated in the plates with/without drugs for 2 h prior to reading. GFP fluorescence was excited with a 473-nm microchip laser, and emission was filtered with 488-nm long-pass and 517/20-nm band-pass filters. Time-resolved fluorescence waveforms for each well were fit to single-exponential decays using least squares minimization global analysis software (Fluorescence Innovations, Inc.) to give donor lifetime and donor–acceptor lifetime .

Selleck Library Screening

The Selleck library, containing 2863 FDA-approved compounds, was purchased from Selleck Chemicals. Selleck compounds were formatted across 3 1536-well plates at 5 nL per well (10 μM final concentration/well). Plates were sealed and stored at −20 °C until use. On the day of screening, drug plates were equilibrated to room temperature. HEK293 cells expressing the biosensor and donor-only reference plasmid were harvested from the 10 cm plates by incubating for 2–4 min with TrypLE (Invitrogen), washed 3 times with PBS, filtered using 70 μm cell strainers (BD Falcon), and resuspended in PBS at a concentration of 2 million cells/mL. Next, cells were dispensed (5 μL/well) into the 1536-well Selleck drug plates (Corning) by a Multidrop Combi Reagent Dispenser (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and allowed to incubate for 2 h at room temperature before readings were acquired using the FLTPR.15,42,43 Donor lifetime in the presence and absence of acceptor was measured using the FLTPR. GFP fluorescence was excited with a 473-nm microchip laser, and emission was filtered with 488-nm long-pass and 517/20-nm band-pass filters. Time-resolved fluorescence waveforms for each well were fit to single-exponential decays using least squares minimization global analysis software (Fluorescence Innovations, Inc.) to give donor lifetime and donor–acceptor lifetime . FRET efficiency (E) was then calculated based on equation (1).

| (1) |

Data Analysis

Cells expressing the biosensor were dispensed into all wells of the drug plates containing either DMSO only (DMSO well), drug in DMSO (drug well), or nothing (empty well). The lifetime of all wells within the plates were acquired using the FLTPR 2 h post-incubation. The data analysis was done per pin of the cell dispenser to account for any variations, or to identify potential issues in pin dispensing via the CV per pin. To analyze the data, the median lifetime of the DMSO wells was determined first, giving a median lifetime of the biosensor. The difference between the lifetime of each DMSO well and the median DMSO well lifetime was calculated. The median of this difference was determined over all DMSO wells, and that median value was multiplied by a factor of 1.48 to give the value of one MAD. The value of 1.48 is a constant determined by statistical theoreticians that when multiplied by the median deviation, gives a value that is asymptotically equivalent to a standard deviation method as applied to normal distributions.44 Subsequently, the median DMSO well lifetime was subtracted from the lifetime of each drug well. This value was then divided by the value of one MAD, to give the total number of MADs from the median, ie, the Z-score (equation 2). If the Z-score was above or below 5, this indicated that the well contained a hit that modulated the lifetime of the biosensor beyond 5 MADs.

| (2) |

where is the lifetime of a specific drug well, is the median DMSO lifetime, and is the lifetime of a specific DMSO well. Plate 1 of the Selleck library was screened in triplicate and plates 2 and 3 were screened 4 times. The following screens were performed on separate days:

Plates 1, 2, and 3;

Triplicate of plate 2;

Triplicate of plate 3;

And duplicate of plate 1

Hits were identified as the compounds that gave a Z-score of +/− 5 among all 3 replicates of plate 1, and 3 out of 4 replicates for plates 2 and 3.

Purification of Flag-tag TRAIL

BL21 bacterial cells containing TRAIL expression vector were grown in 10 mL LB culture overnight for ~16 h at 37 °C while shaking at 225 rpm. One liter of LB-antibiotic culture was inoculated with 10 mL of overnight culture and allowed to grow at 37 °C while shaking at 225 rpm. The 1L culture was induced with 1 mL of 1 M Isopropyl β- d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at an optical density (OD) of 0.5 to 0.6. After IPTG addition, the incubator temperature was lowered to 18 ° C, and culture was left to grow overnight while shaking at 225 rpm. The following day, the bacterial culture was pelleted and then lysed in 15 mL of native lysis buffer (Abcam) and sonicated post-incubation with lysis buffer. The solution was centrifuged at 14,000g for 20 min at 4 °C. The lysate (supernatant) then underwent a flag-tag purification protocol to purify the flag-tagged TRAIL protein. Protein presence was confirmed using Western blot detection of flag-antibody (Cell Signaling, cat#:14793). Protein concentration was determined using Pierce bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA) colorimetric assay.

Determination of Effective Doses of DR5 hit Compounds Using Caspase-8 Assay.

To determine the IC50 of DR5 hits, Jurkat cells were seeded in 96-well white opaque plates at 12,500 cells/well and incubated for 24 h. Cells were then treated with DR5 SELLECK hits (0.001–200 μM), and incubated for an additional 24 h. An equal volume of Caspase-Glo 8 reagent (Promega) was added to each well, and the luminescence was measured after 30 min using a Cytation 3 Cell Imaging Multi-Mode Reader luminometer (BioTek). To test the effects of drugs in combination with TRAIL, Jurkat cells were seeded in 96-well white opaque plates at 12,500 cells/well and incubated for 24 h. Cells were then treated with DR5 SELLECK hits (0.01–400 μM) and DMSO controls, incubated for 2 h, and then treated with purified flag-tag TRAIL (0.1 μg/mL), followed by 24 h of incubationprior to data collection using the same method. Optimization of these experiments is further described in Supplementary Figure 1.

Determination of Drug Toxicity Limit on JURKAT Cells.

Jurkat cells were seeded in 96-well white opaque plates at 12,500 cells/well and incubated for 24 h. Cells were then treated with DR5 hits in a dose dependent manner (0.001–200 μM) with DMSO-only controls and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. After incubation, CytoTox-Glo (Promega) cytotoxicity assay reagent was added to sample wells and incubated for 20 min at room temperature on an orbital shaker. The first luminescence reading was measured using a Cytation3 Cell Imaging Multi-Mode Reader luminometer (BioTek). Next, lysis reagent was added, followed by incubation for 20 min at room temperature on an orbital shaker, and luminescence was measured again using a Cytation 3 Cell Imaging Multi-Mode Reader luminometer. Cell viability was calculated following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Effect of Hit Compounds on TRAIL Binding

Jurkat cells were harvested from 10 cm dishes and washed with PBS 3 times by centrifugation for 5 minutes at 200g. Cells were then counted and diluted to a concentration of 2.5e5 cells/mL in PBS prior to incubation with flag-tagged TRAIL (0.1 μg/mL) +/− the DR5 hits at their respective IC50 concentrations for 2 h on ice. After incubation, cells were washed 2 times with PBS to remove unbound TRAIL. Next, cells were labeled with rabbit anti-flag antibody (Cell Signaling 14793), followed by AF647-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Abcam ab150075). Cells were then analyzed using BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer and quantified using Accuri C6 software. Ten-thousand counts were used per each sample analysis. AF647 channel was used to screen for cells which were positive for the secondary antibody, representing the cells with surface bound TRAIL. Initial gating was done on cells only to gate out cells which were not positive for AF647. The median signal intensity of the AF647 channel was then obtained for each sample and the intensity in the presence of drug was compared to that without drug in order to determine changes in TRAIL binding.

Effect of Hit Compounds on DR5 Expression

Jurkat cells were harvested from 10 cm dishes and washed with PBS 3 times by centrifugation for 5 minutes at 200g. Cells were then counted and diluted to a concentration of 2.5e5 cells/mL in PBS prior to incubation with the DR5 hits at their respective IC50 concentrations for 2 h on ice. After incubation, cells were washed 2 times with PBS and labeled with human DR5 antibody (Ebioscience DJR2-2 4-9909-82) followed by AF647-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (Abcam ab150115). Cells were then analyzed using BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer and quantified using Accuri C6 software. Ten-thousand counts were used per each sample analysis. AF647 channel was used to screen for cells which were positive for the secondary antibody, representing the cells which displayed surface expressed DR5. Initial gating was done on cells only to gate out cells which were not positive for AF647. The median signal intensity of the AF647 channel was then obtained for each sample and the intensity in the presence of drug was compared to that without drug in order to determine changes in DR5 surface expression.

Effect of Hit Compounds on c-FLIP and FADD

Jurkat cells were plated into a T25 flask at 1.25e5 cells/mL on day 1. On day 2, approximately 24 h later, the cells were treated with hit compounds at their respective IC50s, leaving 1 flask as the untreated cell control. This density was chosen by using a doubling time of ~24 hours for Jurkat cells, in order to estimate ~ 2.5e5 cells/mL on day 2 (treatment day), which is equivalent to the conditions for treatment during the caspase-8 functional assay. On day 3, 24 h postdrug treatment, the cells were spun down and washed 3 times in PBS at 200g for 5 min. Cells were lysed in 50 μL of native lysis buffer (Abcam) with Proteoguard EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Takara) and incubated on ice for 1 h. After incubation, the cells were spun down for 10 min at 15,000g in a table-top centrifuge at 4 °C to harvest lysate. The final protein concentration was determined using Pierce BCA kit. Lysate loading conditions were optimized per protein of interest. 5 μg of lysate was loaded for FADD analysis and 20 μg was loaded for c-FLIP analysis on 4% to 20% polyacrylamide gels. Western blot analysis was completed using human FADD antibody (#2782 Cell Signaling) and c-FLIP antibody (#3210 Cell Signaling) to determine the effects of drugs on these key proteins involved in DISC recruitment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The first author would like to thank Dr Nagamani Vunnam, Dr Samantha Yuen, and Dr Robyn Rebbeck for the continuous support, mentorship, and training on this project. The progress made here would not be possible without their intellect, talent, and kindness.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and National Institutes of Health (grant numbers R01HL139065 and R35GM131814)

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval is not applicable for this article.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Statement of Informed Consent

There are no human subjects in this article and informed consent is not applicable.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Merino D, Lalaoui N, Morizot A, Schneider P, Solary E, Micheau O. Differential inhibition of TRAIL-mediated DR5-DISC formation by decoy receptors 1 and 2. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(19):7046–7055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deng D, Shah K. TRAIL of hope meeting resistance in cancer. Trends Cancer. 2020;6(12):989–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uberti D, Ferrari-Toninelli G, Bonini SA, et al. Blockade of the tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis inducing ligand death receptor DR5 prevents beta-amyloid neurotoxicity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32(4):872–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantarella G, Uberti D, Carsana T, Lombardo G, Bernardini R, Memo M. Neutralization of TRAIL death pathway protects human neuronal cell line from beta-amyloid toxicity. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10(1):134–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cantarella G, Di Benedetto G, Scollo M, et al. Neutralization of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand reduces spinal cord injury damage in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(6):1302–1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cantarella G, Pignataro G, Di Benedetto G, et al. Ischemic tolerance modulates TRAIL expression and its receptors and generates a neuroprotected phenotype. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5(7):1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy P, LeVine H. Alzheimer’s disease and the β-amyloid peptide. J Alzheimer’s Disease. 2010;19(1):331–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giraldo E, Lloret A, Fuchsberger R, Vina J. AB And tau toxicities in Alzheimer’s are linked via oxidative stress-induced p38 activation: protective role of vitamin E. Redox Biol. 2014;2:873–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheignon C, Tomas M, Bonnefont-Rousselot D, Faller P, Hureau C, Collin F. Oxidative stress and the amyloid beta peptide in Alzheimer’s disease. Redox Biol. 2018;14:450–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sardar Sinha M, Ansell-Schultz A, Civitelli L, et al. Alzheimer’s disease pathology propagation by exosomes containing toxic amyloid-beta oligomers. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136(1):41–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malhi H, Barreyro F, Isomoto H, Bronk S, Gores G. Free fatty acids sensitise hepatocytes to TRAIL mediated cytotoxicity. Gut. 2007;56(8):1124–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cazanave SC, Mott JL, Bronk SF, et al. Death receptor 5 signaling promotes hepatocyte lipoapoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(45):39336039348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akazawa Y, Nakao K. To die or not to die: death signaling in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53(8):893–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lo CH, Schaaf TM, Grant BD, et al. Noncompetitive inhibitors of TNFR1 probe conformational activation states. Sci Signal. 2019;12(592):eaav5637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lo CH, Vunnam N, Lewis AK, et al. An innovative high-throughput screening approach for discovery of small molecules that inhibit TNF receptors. SLAS Discov. 2017;22(8):950–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valley CC, Lewis AK, Mudaliar DJ, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) induces death receptor 5 networks that are highly organized. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(25):2126521278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vunnam N, Campbell-Bezat C, Lewis A, Sachs J. Death receptor 5 activation is energetically coupled to opening of the transmembrane domain dimer. Biophys J. 2017;113(2):381–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bunch TA, Guhathakurta P, Lepak VC, et al. Cardiac myosin-binding protein C interaction with actin is inhibited by compounds identified in a high-throughput fluorescence lifetime screen. J Biol Chem. 2021;297(1):100840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schaaf TM, Peterson KC, Grant BD, et al. High-Throughput spectral and lifetime-based FRET screening in living cells to identify small-molecule effectors of SERCA. SLAS Discov. 2017;22(3):262–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sandu C, Morisawa G, Wegorzewska I, et al. FADD self-association is required for stable interaction with an activated death receptor. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13(12):2052–2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh N, Hassan A, Bose K. Molecular basis of death effector domain chain assembly and its role in caspase-8 activation. FASEB J. 2016;30(1):186–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang Y, Yang X, Xu T, et al. Overcoming resistance to TRAIL-induced apoptosis in solid tumor cells by simultaneously targeting death receptors, c-FLIP and IAPs. Int J Oncol. 2016;49(1):153–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hillert LK, Ivanisenko NV, Espe J, et al. Long and short isoforms of c-FLIP act as control checkpoints of DED filament assembly. Oncogene. 2020;39(8):1756–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang P, Zhang J, Bellail A, et al. Inhibition of RIP and c-FLIP enhances TRAIL-induced apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. Cellular Signaling. 2007;19(11):2237–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nazim U, Yin H, Park S. Downregulation of c-FLIP and upregulation of DR-5 by cantharidin sensitizes TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in prostate cancer cells via autophagy flux. Int J Mol Med. 2020;46(1):280–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haag C, Stadel D, Zhou S, et al. Identification of c-FLIP(L) and c-FLIP(S) as critical regulators of death receptor-induced apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. Gut. 2011;60(2):225–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu YJ, Lin YC, Lee JC, et al. CCT327 Enhances TRAIL-induced apoptosis through the induction of death receptors and downregulation of cell survival proteins in TRAIL-resistant human leukemia cells. Oncol Rep. 2014;32(3):1257–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sophonnithiprasert T, Nilwarangkoon S, Nakamura Y, Watanapokasin R. Goniothalamin enhances TRAIL-induced apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells through DR5 upregulation and cFLIP downregulation. Int J Oncol. 2015;47(6):2188–2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Artykov AA, Yagolovich AV, Dolgikh DA, et al. Death receptors DR4 and DR5 undergo spontaneous and ligand-mediated endocytosis and recycling regardless of the sensitivity of cancer cells to TRAIL. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:820069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi J, Shen HM. Critical role of bid and bax in indirubin-3′-monoxime-induced apoptosis in human cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75(9):1729–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karpinich NO, Tafani M, Schneider T, Russo MA, Farber JL. The course of etoposide-induced apoptosis in Jurkat cells lacking p53 and Bax. J Cell Physiol. 2006;208(1):55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoessel R, Leclerc S, Endicott JA, et al. Indirubin, the active constituent of a Chinese antileukaemia medicine, inhibits cyclin-dependent kinases. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1(1):60–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lai JL, Liu YH, Liu C, et al. Indirubin inhibits LPS-induced inflammation via TLR4 abrogation mediated by the NF-kB and MAPK signaling pathways. Inflammation. 2017;40(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen L, Wang J, Wu J, Zheng Q, Hu J. Indirubin suppresses ovarian cancer cell viabilities through the STAT3 signaling pathway. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2018;12:3335–3342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alex D, Lam IK, Lin Z, Lee SM. Indirubin shows anti-angiogenic activity in an in vivo zebrafish model and an in vitro HUVEC model. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;131(2):242–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y, Hoi PM, Chan JY, Lee SM. New perspective on the dual functions of indirubins in cancer therapy and neuroprotection. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2014;14(9):1213–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leclerc S, Garnier M, Hoessel R, et al. Indirubins inhibit glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta and CDK5/p25, two protein kinases involved in abnormal tau phosphorylation in Alzheimer’s disease. A property common to most cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(1):251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ding Y, Qiao A, Fan GH. Indirubin-3′-monoxime rescues spatial memory deficits and attenuates beta-amyloid-associated neuropathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;39(2):156–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vunnam N, Grant BD, Thomas D, Sachs J. Soluble extracellular domain of death receptor 5 inhibits TRAIL-induced apoptosis by disrupting receptor receptor interactions. Under review at Nature Scientific Reports. 2017;429(19):2943–2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Von Stetten D, Noirclerc-Savoye M, Goedhart J, Gadella TW, Royant A. Structure of a fluorescent protein from Aequorea Victoria bearing the obligate-monomer mutation A206K. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2012;68(Pt 8):878–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vunnam N, Young MC, Lo CH, Thomas D, Sachs JN. Live-cell high-throughput screening platform for the discovery of small molecule modulators of death receptor 5 signaling. Submitted 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vunnam N, Lo CH, Grant BD, Thomas DD, Sachs JN. Soluble extracellular domain of death receptor 5 inhibits TRAIL-induced apoptosis by disrupting receptor-receptor interactions. J Mol Biol. 2017;429(19):2943–2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gruber SJ, Cornea RL, Li J, et al. Discovery of enzyme modulators via high-throughput time-resolved FRET in living cells. J Biomol Screen. 2014;19(2):215–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rousseeuw PJ, Crous C. Alternatives to the median absolute deviation. J Am Stat Assoc. 1993;88(424):1273–1283. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.