Abstract

Introduction

Stroke is a severe complication of sickle cell anemia (SCA), with devastating sequelae. Transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasonography predicts stroke risk, but implementing TCD screening with suitable treatment for primary stroke prevention in low-resource environments remains challenging. SPHERE (NCT03948867) is a prospective phase 2 open-label hydroxyurea trial for SCA in Tanzania.

Methods

After formal training and certification, local personnel screened children 2–16 years old; those with conditional (170–199 cm/s) or abnormal (≥200 cm/s) time-averaged mean velocities (TAMVs) received hydroxyurea at 20 mg/kg/day with dose escalation to maximum tolerated dose (MTD). The primary study endpoint is change in TAMV after 12 months of hydroxyurea; secondary endpoints include SCA-related clinical events, splenic volume and function, renal function, infections, hydroxyurea pharmacokinetics, and genetic modifiers.

Results

Between April 2019 and April 2020, 202 children (average 6.8 ± 3.5 years, 53% female) enrolled and underwent TCD screening; 196 were deemed eligible by DNA testing. Most had numerous previous hospitalizations and transfusions, with low baseline hemoglobin (7.7 ± 1.1 g/dL) and %HbF (9.3 ± 5.4%). Palpable splenomegaly was present at enrollment in 49 (25%); average sonographic splenic volume was 103 mL (range 8–1,045 mL). TCD screening identified 22% conditional and 2% abnormal velocities, with hydroxyurea treatment initiated in 96% (45/47) eligible children.

Conclusion

SPHERE has built local capacity with high-quality research infrastructure and TCD screening for SCA in Tanzania. Fully enrolled participants have a high prevalence of elevated baseline TCD velocities and splenomegaly. SPHERE will prospectively determine the benefits of hydroxyurea at MTD for primary stroke prevention, anticipating expanded access to hydroxyurea treatment across Tanzania.

Keywords: Sickle cell anemia, Hydroxyurea, Stroke, Sub-Saharan Africa, Transcranial Doppler

Introduction

Sickle cell anemia (SCA) is an inherited hematological disorder characterized by chronic hemolytic anemia, recurrent acute vaso-occlusive events, cumulative multisystem organ damage, and premature death [1]. Stroke is a common and catastrophic event for children with SCA. In Jamaica, 7.8% of children with SCA developed clinical stroke by 14 years old [2]. In the US Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease, 11% of children with HbSS had a stroke by 20 years of age with the greatest risk between ages 2–5 years when overall incidence reaches 0.75 per 100 patient-years [3]. Before the introduction of disease-modifying therapy with blood transfusions or hydroxyurea, stroke recurrence was common [4] and often caused disability and death [5].

Stroke risk is one of the few predictable aspects of SCA disease management, as the velocity of cerebral arterial blood flow can be measured noninvasively with transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasonography to assess the risk of developing primary stroke [6]. Children with elevated TCD velocities have a higher risk of stroke and can be prescribed more aggressive treatment to decrease the risk of a future neurological event. Particularly for children with abnormal TCD velocities (≥200 cm/s), regular transfusions decrease stroke risk by improving anemia and replacing endogenous sickle erythrocytes with healthy erythrocytes [7]. The use of systematic TCD screening and transfusion prophylaxis has drastically lowered the incidence of first stroke in high-income countries [8].

SCA is most common in sub-Saharan Africa [9] where mortality is extremely high [10], and the consequences of stroke are more severe [11, 12]. Blood supply and transfusion services in Africa are currently inadequate to support a safe and effective chronic transfusion program for SCA [13, 14]. Hydroxyurea is an attractive alternative for both primary and secondary stroke preventions. The NOHARM and REACH trials have documented the benefits of hydroxyurea at maximum tolerated dose (MTD) for children with SCA living in Africa [15, 16], and recently the NOHARM MTD trial was halted prematurely when a higher dose of ∼30 mg/kg/day was superior to a lower fixed dose of ∼20 mg/kg/day without increased toxicity [17]. Challenges remain, however, about the most practical approach for implementing an integrated TCD screening and treatment program in Africa, specifically for primary stroke prevention.

Stroke Prevention with Hydroxyurea Enabled through Research and Education (SPHERE, ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03948867) is a prospective, phase 2 open-label dose escalation trial of hydroxyurea to evaluate the feasibility and benefits of hydroxyurea escalated to MTD for primary stroke prevention in children with SCA living in Tanzania, while also enhancing local research capacity. We now describe the study design and baseline enrollment characteristics of SPHERE, which will determine the efficacy of hydroxyurea in this setting.

Materials and Methods

Clinical Performance Site

SPHERE is conducted at Bugando Medical Centre (BMC), a 900-bed referral and teaching hospital in northwest Tanzania, on the shores of Lake Victoria. Mwanza is the second largest urban center in Tanzania with approximately 1 million people in Mwanza city and 3 million people in the Mwanza region. As one of five national referral hospitals, BMC provides tertiary care for 16 million people. Northwest Tanzania has the highest prevalence of SCA in the country, recently measured at 1.2% of all births [18].

BMC houses the only sickle cell clinic for the entire catchment area, which operates 2 days per week and cares for >700 children with SCA. Children are seen for routine visits approximately every 1–3 months depending on severity of disease. Families are provided an insecticide-treated bed net and patients are prescribed daily penicillin prophylaxis and folic acid supplementation. The national vaccine program includes Haemophilus influenza type b and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines. Per recently published national guidelines [19], hydroxyurea is now recommended for all children with sickle cell disease, but few families can afford the medication. Blood transfusions are available for severe anemia, but chronic scheduled transfusion programs are not feasible due to a limited blood supply.

Capacity Building

A group of potential TCD examiners was invited to attend a 2-day in-person training educational seminar reviewing TCD theory and standards, along with a practical hands-on workshop where participants learned to obtain high-quality TCD measurements. This was followed by ongoing remote training. Practice exams performed locally were reviewed by an outside expert TCD examiner prior to certification. Each prospective TCD examiner was required to submit at least 20 high-quality exams before achieving formal certification. Principals of TCD techniques, common errors, and best practices were reviewed during a regular teleconference, and an annual in-person refresher workshop was conducted.

Patient Population

Children with SCA 2.0–16.0 years of age, attending the BMC clinic with a parent or guardian, were invited to join the SPHERE trial. Patients were not enrolled until 2 weeks had elapsed since any recent febrile illness, hospitalization, or blood transfusion. Enrolled participants with elevated TCD velocities, either conditional (170–199 cm/s) or abnormal (≥200 cm/s), were prescribed hydroxyurea therapy unless they had a medical condition making hydroxyurea ill-advised (e.g., malignancy, uncontrolled infection, pregnancy). Children with normal TCD velocities (<170 cm/s) will be rescreened after 12 and 24 months, to document further TCD conversions and allow more children to receive hydroxyurea treatment.

Sample Size

The sample size was calculated to detect a mean decrease in TCD velocity of 15 cm/s with a standard deviation of 30 cm/s. It was determined that 36 evaluable subjects would provide 90% power to detect this decrease from baseline to month 12 from a one-sided t test with 0.05 level of significance. To allow for dropout, the study aimed to enroll approximately 200 children in the screening phase so that approximately 40 would be eligible for hydroxyurea therapy.

Data Collection

Baseline data included demographic characteristics, comprehensive clinical history and physical examination, immunization history, concomitant medications, and laboratory results. The clinical history was self-reported by the parent. For each participant, Z-scores were calculated for height-for-age and weight-for-height using published WHO growth metrics [20]. Data were entered into an Internet-based Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCapTM) database [21, 22]. Primary source documents were uploaded into REDCapTM to allow remote study monitoring.

Study Treatment

Hydroxyurea is initiated at 20 mg/kg/day, averaged over the course of a week in the form of available 500 mg capsules, using an online dosing calculator. Laboratory values are checked monthly, and hydroxyurea is escalated every 8 weeks to achieve mild myelosuppression, when the following escalation laboratory criteria are met: absolute neutrophil count (ANC) >4.0 × 109/L, Hb >6.5 g/dL, absolute reticulocyte count (ARC) >150 × 109/L, and platelets >150 × 109/L. The MTD is determined when consistent mild myelosuppression is achieved on 2 consecutive visits, with a maximum dose of 35 mg/kg/day. Children return every 3 months after reaching a stable MTD dose for a medication refill. Hydroxyurea treatment is temporarily suspended if any of the following dose-limiting toxicities occur: ANC <1.0 × 109/L; Hb <4.0 g/dL; Hb <6.0 g/dL with an ARC <100 × 109/L; ARC <80 × 109/L with Hb <7.0 g/dL; or platelets <80 × 109/L. If the toxicity resolves within 2 weeks, the same dose is restarted. If it persists beyond 2 weeks, hydroxyurea is restarted at a lower dose after the toxicity resolves, as previously described [15, 16].

Endpoints

The primary study endpoint is the change in TCD velocities from enrollment until 12 months of hydroxyurea treatment. Secondary endpoints include SCA-related clinical events; changes in splenic volume and function; change in renal function; incidence of infection, especially malaria; hydroxyurea pharmacokinetics; and genetic modifiers of disease including pharmacogenomics.

Safety

All serious adverse events and clinical adverse events, Grade 2 or above, are recorded for children receiving hydroxyurea study treatment. Those with normal enrollment TCD examinations are rescreened at 12 months and 24 months, and all neurological events and serious adverse events are recorded. A Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB) that includes clinicians and researchers in Tanzania with expertise in SCA, hydroxyurea treatment, biostatistics, and global health research was formed and reviews the data every 6 months.

Laboratory

Automated complete (full) blood counts are performed using a commercial hematology analyzer (DH76; Dymind Biotech, Shenzhen, China), while ARCs are calculated by microscopy with vital staining. Quantitative measurement of fetal hemoglobin (%HbF) is performed locally using HPLC (SmartLife PolyLC, Columbia, MD, USA) and calculated as a percent of total HbF + HbS present. At baseline, whole blood was collected on FTA cards (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) and stored at −80°C until further analysis.

TCD and Splenic Ultrasound

The maximum time-averaged mean velocity (TAMV) is measured by TCD ultrasonography in each of the major intracerebral arterial segments as performed in the STOP protocol [23] using a 2-MHz nonimaging Sonara/tek instrument. Each exam is centrally reviewed and scored by an expert TCD specialist blinded to all clinical and laboratory data, as previously described [24]. The TCD exam is considered adequate if velocities can be measured in all three major vessels in at least one hemisphere. Spleen size is measured using a GE Logiq V5 Expert ultrasound with 3.5 MHz curvilinear probe. With the participant in the supine position, the maximum distance in the longitudinal (cranio-caudal), anterior-posterior, and transverse dimensions is recorded. Spleen volume is calculated using the formula for an ellipsoid shape: longitudinal length × anterior-posterior depth × transverse width × 0.523 [25].

Genetic Modifiers

FTA cards were kept frozen until transport to CCHMC, where DNA-based studies were performed to (1) confirm the diagnosis of SCA; (2) identify concomitant glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency; and (3) document the presence of alpha thalassemia trait. Genomic DNA was prepared from FTA cards using the InstaGene Matrix protocol (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) [26]. As previously described, the diagnosis of SCA was determined using a customized TaqMan probe designed for the HbS rs334 polymorphism; the G6PD A− variant was identified using three commercially available TaqMan probe sets; and detection of 3.7 kb α-globin gene deletional (−α3.7) thalassemia trait was performed using a copy-number variant TaqMan assay with custom TaqMan probes [27].

Results

Enrollment

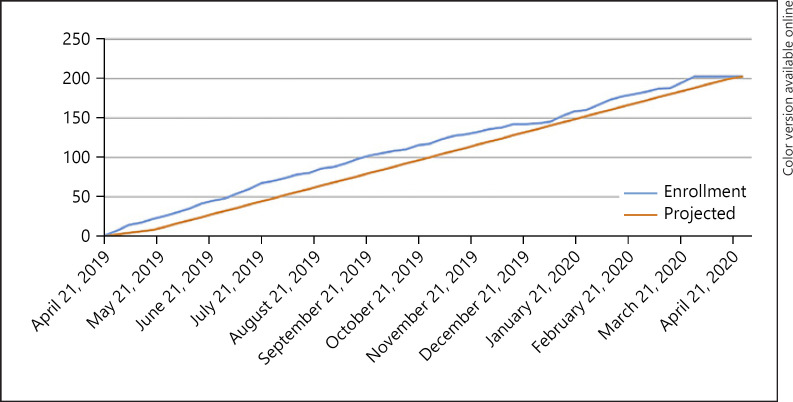

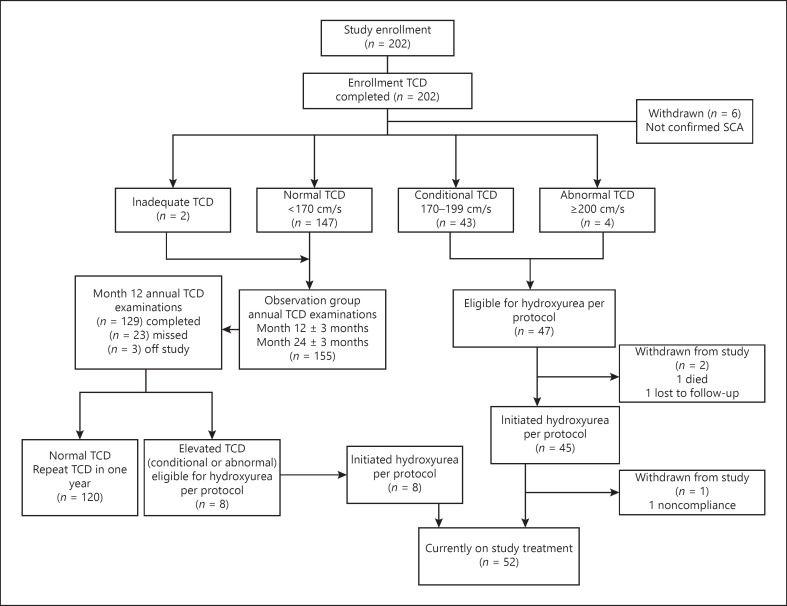

Enrollment occurred briskly, and 202 children underwent TCD screening, slightly exceeding the projected enrollment pace and goal (shown in Fig. 1). A total of 196 had confirmed SCA (HbSS), continued in the trial, and are included in this analysis. Figure 2 illustrates a CONSORT diagram of the study enrollment and current status of the participants.

Fig. 1.

SPHERE performed 202 screening transcranial Doppler ultrasound exams over the course of 12 months, exceeding the proposed enrollment timeline.

Fig. 2.

SPHERE enrollment CONSORT diagram. SPHERE aimed to enroll about 200 children. TCD, transcranial Doppler ultrasound.

Enrollment Characteristics

The average age (mean ± SD) at enrollment was 6.8 ± 3.5 years, and 53% were female (Table 1). Overall, the children were small and undernourished: the mean weight-for-height was −1.03 ± 1.19 for all participants and slightly lower in children with elevated TCD velocities (−1.31 ± 0.94) than normal velocities (−0.94 ± 1.25), p = 0.066. Most had previous dactylitis (77%), painful vaso-occlusive episode (93%), and malaria (88%). Previous splenic sequestration was common (35%), but only 1 (0.5%) had undergone surgical splenectomy at the time of enrollment. The majority (68%) had received at least one previous transfusion, and 31% of the children had over 5 previous hospitalizations. None of the enrolled participants had previous history of stroke, and only 7 (4%) of the children had previously used hydroxyurea.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of children with SCA enrolled in SPHERE

| All participants1 | Normal TCD | Elevated TCD | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 196 | 149 | 47 | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age at enrollment, mean±SD, years | 6.8±3.5 | 6.9±3.6 | 6.3±3.2 | 0.288 |

| Male, N (%) | 93 (47) | 71 (48) | 22 (47) | |

| Female, N (%) | 103 (53) | 78 (52) | 25 (53) | 1.000 |

| Intake physical examination | ||||

| Height, cm | 111.5±18.5 | 112.0±19.3 | 110.1±15.8 | 0.553 |

| Weight, kg | 18.6±6.6 | 19.0±6.7 | 17.6±6.2 | 0.213 |

| Splenectomy, N (%) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Spleen palpable, N (%) | 49 (25) | 36 (24) | 13 (28) | 0.772 |

| Spleen palpable ≥5 cm, N (%) | 32 (16) | 23 (15) | 9 (19) | 0.146 |

| Oxygen saturation (%), mean±SD | 93.0±4.3 | 94.0±3.9 | 91.7±5.0 | 0.001 |

| Enlarged tonsillar tissue, N (%) | 149 (74) | 108 (73) | 41 (87) | 0.130 |

| Growth parameters, Z-score | ||||

| Weight-for-height | –1.08±1.36 | –1.01±1.46 | –1.31±0.94 | 0.066 |

| Height-for-age | –1.35±1.10 | –1.43±1.10 | –1.11±1.09 | 0.082 |

| Past medical history, N (%) | ||||

| Vaso-occlusive painful event | 182 (93) | 137 (92) | 45 (96) | 0.465 |

| Dactylitis | 150 (77) | 118 (79) | 32 (68) | 0.108 |

| Malaria | 173 (88) | 132 (89) | 41 (87) | 0.415 |

| Acute chest syndrome/pneumonia | 70 (36) | 53 (36) | 17 (36) | 1.000 |

| Splenic sequestration | 68 (35) | 54 (36) | 14 (30) | 0.708 |

| Previous stroke | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Bacteremia/sepsis | 73 (37) | 60 (40) | 13 (28) | 0.262 |

| Transfusion | 135 (69) | 100 (67) | 35 (74) | 0.372 |

| Past hydroxyurea use | 7 (4) | 6 (4) | 1 (2) | 1.000 |

| Lifetime hospitalizations, N (%) | ||||

| ≤5 hospitalizations | 135 (69) | 105 (70) | 30 (64) | 0.602 |

| 6–10 hospitalizations | 30 (15) | 21 (14) | 9 (19) | |

| >10 hospitalizations | 31 (16) | 23 (15) | 8 (17) | |

| Baseline parameters, mean±SD | ||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 7.7±1.1 | 7.9±1.1 | 7.1±1.0 | <0.001 |

| MCV, fL | 78±10 | 79±10 | 82±9 | 0.037 |

| Fetal hemoglobin, % | 9.3±5.4 | 9.6±5.7 | 8.5±4.0 | 0.251 |

| ARC, ×103/L | 566±243 | 558±241 | 594±249 | 0.364 |

| WBC count, ×109/L | 14.5±5.4 | 14.2±5.8 | 15.3±3.7 | 0.251 |

| ANC, ×109/L | 5.5±2.3 | 5.4±2.3 | 5.9±2.3 | 0.172 |

| Platelets, ×109/L | 379±164 | 378±162 | 382±173 | 0.899 |

| ALT, U/L | 21±16 | 20±15 | 23±18 | 0.355 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.22±0.12 | 0.23±0.11 | 0.19±0.12 | 0.013 |

| TCD velocities, mean±SD | ||||

| TAMV, cm/s | 149±25 | 138±18 | 182±12 | <0.001 |

A total of 202 children were enrolled, but 6 were withdrawn following confirmatory diagnostic testing. MCV, mean corpuscular volume; WBC, white blood cell; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; ALT, alanine transferase.

Baseline laboratory results were in the expected ranges for children with SCA who are not receiving disease-modifying therapy. Hemolytic anemia was documented with a low hemoglobin concentration and compensatory reticulocytosis, as well as the expected leukocytosis (Table 1). The average baseline HbF was 9.3 ± 5.4%. Comparing children with elevated TCD velocities to those with normal TCD velocities, the average hemoglobin concentration was lower (7.1 vs. 7.9 g/dL, p < 0.001) as was the oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry (91.7% vs. 94.0%, p < 0.01), but other laboratory parameters were similar between the two groups (Table 1).

TCD Velocities

TCD examinations were performed in all children at enrollment, and only 2 participants (1%) had inadequate exams. Among the 194 adequate exams, the average maximum TAMV was 149 ± 25 cm/s with 76% normal, 22% conditional, and 2% abnormal velocities. Participants with an elevated TCD velocity were slightly younger than those with normal velocities (6.3 vs. 6.9 years), but this difference was not statistically significant. For those with elevated TCD velocities, the average TAMV was 182 cm/s, compared to 138 cm/s for the normal cohort (Table 1).

Splenic Measurements

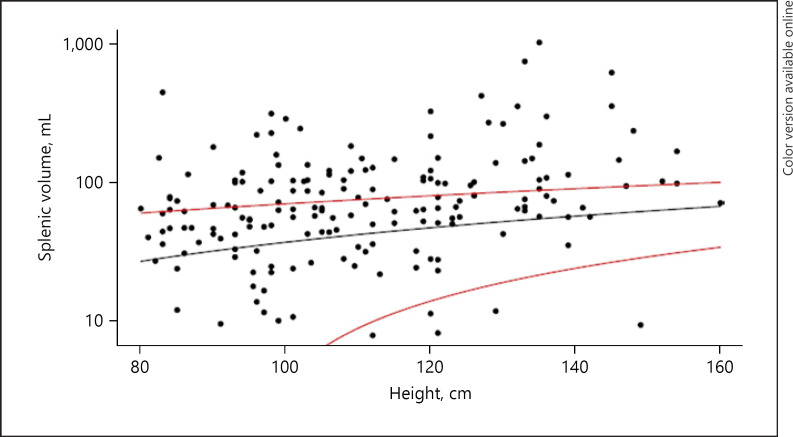

Baseline assessment by physical examination revealed a palpable spleen in 49 children (25%), and over half of these (32/49) were ≥5 cm below the costal margin (Table 2). Larger spleen size by palpation correlated with a history of splenic sequestration, and a lower baseline hemoglobin, but not with age. Baseline abdominal ultrasonography documented splenic tissue in 177 children (90%), with an average splenic volume of 103 ± 124 mL (range 8–1,045 mL). The splenic volume correlated with the amount of palpable splenic tissue (p < 0.001). Splenic volume also correlated with participant height, history of splenic sequestration, lower hemoglobin concentration, lower platelet count, and fewer copies of the alpha globin gene. Almost half (39%) of participants had splenic volumes that were above the 95th percentile for height (shown in Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Associations between palpable splenomegaly and baseline clinical and laboratory parameters

| Palpable splenomegaly | None | 1.0–4.9 cm | 5.0–9.9 cm | ≥10 cm | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 148 | 16 | 28 | 4 | |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age at enrollment, mean±SD, years | 6.9±3.5 | 5.7±3.2 | 6.6±3.5 | 7.3±3.7 | 0.559 |

| Male, N (%) | 71 (48) | 7 (44) | 12 (43) | 3 (75) | |

| Female, N (%) | 77 (52) | 9 (56) | 16 (57) | 1 (25) | 0.701 |

| Baseline examination, mean±SD | |||||

| Height, cm | 112.5±18.5 | 105.3±19.2 | 109.5±18.0 | 116.0±10.8 | 0.438 |

| Weight, kg | 18.9±6.7 | 16.8±6.7 | 17.9±6.2 | 19.6±7.7 | 0.589 |

| O2 saturation, % | 93.0±4.5 | 93.3±3.3 | 95.4±3.3 | 96.0±2.9 | 0.029 |

| Medical history, N (%) | |||||

| Painful event | 135 (93) | 16 (100) | 27 (100) | 4 (100) | 0.423 |

| Dactylitis | 114 (78) | 11 (69) | 23 (82) | 2 (50) | 0.357 |

| Malaria | 132 (91) | 14 (88) | 25 (93) | 2 (50) | 0.094 |

| Acute chest syndrome | 51 (35) | 4 (25) | 14 (50) | 1 (25) | 0.350 |

| Splenic sequestration | 39 (31) | 4 (40) | 21 (84) | 4 (100) | <0.001 |

| Previous stroke | |||||

| Bacteremia/sepsis | 55 (43) | 4 (33) | 13 (54) | 1 (33) | 0.640 |

| Transfusion | 98 (66) | 9 (56) | 24 (86) | 4 (100) | 0.060 |

| Hydroxyurea use | 4 (3) | 1 (6) | 2 (7) | 0.341 | |

| Lifetime hospitalizations, N (%) | |||||

| ≤5 hospitalizations | 104 (70) | 13 (81) | 17 (61) | 1 (25) | 0.019 |

| 6–10 hospitalizations | 24 (16) | 1 (6) | 4 (14) | 1 (25) | |

| >10 hospitalizations | 20 (14) | 2 (13) | 7 (25) | 2 (50) | |

| Laboratory parameters, mean±SD | |||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 7.8±1.1 | 7.8±0.7 | 7.3±1.2 | 5.4±0.8 | <0.001 |

| MCV, fL | 79.5±10.2 | 78.1±9.8 | 81.4±10.4 | 84.1±10.4 | 0.590 |

| Fetal hemoglobin, % | 9.2±5.4 | 11.7±5.8 | 8.6±5.0 | 10.4±5.9 | 0.280 |

| ARC, ×103/L | 537±223 | 734±250 | 599±282 | 760±349 | 0.005 |

| WBC, ×109/L | 14.1±4.4 | 15.1±3.9 | 16.8±9.1 | 10.7±5.7 | 0.046 |

| ANC, ×109/L | 5.4±2.3 | 6.2±2.3 | 6.1±2.2 | 5.0±3.6 | 0.266 |

| Platelets, ×109/L | 404±164 | 318±107 | 317±152 | 119±45 | <0.001 |

| ALT, U/L | 21±15 | 16±6 | 22±23 | 28±9 | 0.412 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.2±0.1 | 0.3±0.1 | 0.2±0.1 | 0.2±0.1 | 0.318 |

| Spleen volume, mL | |||||

| Mean±SD | 71.5±55.9 | 118.5±78.9 | 173.7±148.2 | 589.2±382.4 | <0.001 |

| Median | 57.7 | 97.8 | 110.5 | 540.6 | <0.001 |

| IQR (25%, 75%) | (35.7, 91.0) | (66.0, 137.1) | (83.7, 221.7) | (297.1, 832.6) | |

| TCD velocity, mean±SD | |||||

| TAMV, cm/s | 149±25 | 147±26 | 146±28 | 167±18 | 0.472 |

Fig. 3.

Correlation of splenic volume and body length for children enrolled in SPHERE. Black line = correlation in SPHERE study. Red lines = 95% confidence interval for a normal population of children without sickle cell disease living in a high-income country [24].

Genetic Modifiers

Six children were found to be ineligible after DNA testing confirmed sickle cell trait. All of the other children were confirmed to have HbSS, and specifically none had heterozygous beta thalassemia trait that is present in East Africa [28]. Alpha thalassemia trait was common with half of the study participants having either 1 gene deletion (38%) or 2 gene deletions (12%). G6PD deficiency (A− variant) was present in 15% of boys, while 27% of girls were heterozygous and 5% of girls were homozygous for this mutation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence of α-thalassemia and G6PD deficiency observed in SPHERE participants

| Genotype | Clinical effect | Observation | Hydroxyurea | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α thalassemia, N (%) | n = 149 | n = 47 | ||

| 5 copies, αα/ααα | 1-gene duplication, unaffected | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.133 |

| 4 copies, αα/αα | 0-gene deletion, unaffected | 64 (43) | 29 (62) | |

| 3 copies, αα/–α3.7 | 1-gene deletion, silent carrier | 60 (40) | 14 (30) | |

| 2 copies, -α3.7/-α3.7 | 2-gene deletion, trait | 20 (13) | 3 (6) | |

| Indeterminate | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | ||

| No sample tested | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | ||

| G6PD deficiency, N (%) | ||||

| Males (n = 93) | n = 71 | n = 22 | 0.737 | |

| B or A+ | Unaffected male | 59 (83) | 18 (82) | |

| A– | Affected male | 10 (14) | 4 (18) | |

| Indeterminate | ||||

| No result | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.233 | |

| Females (n = 103) | n = 78 | n = 25 | ||

| BB, BA+, A+A+ | Homozygous wild type, unaffected | 54 (69) | 13 (52) | |

| BA–, A+A– | Heterozygous A– variant, carrier | 19 (24) | 9 (36) | |

| A–A– | Homozygous A– variant, affected | 3 (4) | 2 (8) | |

| Indeterminate | 1 (1) | 1 (4) | ||

| No sample tested | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Treatment Initiation

Of 47 children eligible for hydroxyurea for elevated TCD velocities, 45 successfully initiated treatment. Two children were not treated; 1 withdrew due to distance from the clinic, and 1 developed acute splenic sequestration and died before initiating study treatment (shown in Fig. 2). The starting dose was 20.2 ± 1.4 mg/kg/day (range 17.1–22.4 mg/kg/day).

Discussion/Conclusion

We describe the study design and baseline data for the prospective SPHERE trial, which has fully enrolled a large cohort of Tanzanian children with SCA. With investment in local infrastructure and families who are eager to participate, the trial enrolled ahead of schedule (Fig. 1). Using well-trained and formally certified local examiners, the children underwent baseline TCD screening that identified a high proportion (24%) with either conditional (22%) or abnormal (2%) TCD velocities. These data document a higher prevalence of elevated TCD velocities, compared to earlier US-based studies that identified 10–17% of untreated children with high risk for primary stroke [6, 29, 30]. In addition, we found lower mean hemoglobin concentration, oxygen saturation, serum creatinine, and mean corpuscular volume in children with elevated TCD velocities, confirming that previously identified markers of disease severity correlate with elevated TCD velocities in the sub-Saharan African context. This higher overall prevalence of elevated TCD velocities in our Tanzanian cohort is similar to the prevalence of elevated TCD velocities documented among children with SCA in East Africa [24], West Africa [31], and the Caribbean [32, 33]. Whether this higher prevalence reflects biological, genetic, or environmental differences is unclear, but highlights the need for reliable TCD screening to prevent pediatric stroke. Particularly in low-resource countries where medical rehabilitative services are limited and the socioeconomic impact of stroke is high, an effective TCD screening program with direct linkage to disease-modifying therapy is an essential part of care for children with SCA.

For children in the USA with SCA and elevated TCD velocities, an impressive decrease in clinical neurovascular complications using chronic transfusions was first proven over 20 years ago [7], but this approach has been extremely challenging to implement in low- and middle-income countries within sub-Saharan Africa. First, there are difficulties in establishing a robust TCD screening program, beginning with the costs of instrumentation and the need for a formal training and certification process. Issues related to a safe and adequate blood supply are also formidable, since demand outstrips the supply necessary to support population needs, even before estimating the blood needed to adequately provide chronic transfusion therapy for children with SCA [34]. Even with an adequate supply, however, blood banking practices with full cross-matching and extended red cell typing are typically unavailable even at major referral centers [35]. Erythrocyte alloimmunization is not uncommon from sporadic transfusions in sub-Saharan Africa [36], and regularly scheduled transfusions for stroke prevention will likely increase the incidence of alloimmunization and complicate future care [37]. Blood is only screened for four pathogens: HIV, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and syphilis. Finally, repeated simple transfusions will inevitably lead to iron overload, which carries additional morbidity.

A suitable alternative to transfusions for stroke prevention is oral hydroxyurea, which modifies red cell and vascular physiology through multiple mechanisms [38]. The stimulation of fetal hemoglobin production and consequent inhibition of polymerization and hemolysis enable greater red cell survival, higher hemoglobin, and greater oxygen delivery to the tissues including the brain. The reduction in circulating leukocytes, free heme, and reactive oxygen species, along with greater bioavailability of nitric oxide, decrease the chronic inflammatory state that contributes to development and progression of vasculopathy. US-based studies have shown that hydroxyurea when escalated to achieve mild myelosuppression reduces TCD velocities [29] and maintains the reduction achieved by chronic transfusion in children receiving transfusions for primary stroke prevention [39]. A recent publication from Jamaica also documented the reduction in elevated TCD velocities from hydroxyurea at MTD [40].

The NOHARM MTD trial in Uganda demonstrated the feasibility and superiority of escalating hydroxyurea to MTD at ∼30 mg/kg/day, compared to fixed dose at ∼20 mg/kg/day, for decreasing complications of SCA [17]. Despite a report suggesting that moderate fixed dose hydroxyurea can reduce primary stroke rates [41], children with elevated TCD velocities are an especially high-risk group who could derive particular benefit from dose escalation to MTD if it can reasonably be accomplished, especially at referral centers in Africa where TCD screening becomes established. Access to and interpretation of laboratory monitoring, and medication titration using fixed pill sizes (usually 500 mg capsules) may be challenging. In the SPHERE trial, we are facilitating dosing adjustments using an online calculator that incorporates current laboratory values and weight, plus the previously prescribed dose, to avoid dosing errors and ensure that doses are held or reduced when hematological toxicities are observed. The dosing calculator also averages the weight-based dose over the course of a week so that a weekly number of capsules can be prescribed for children who take less than one pill per day. In SPHERE, clinical and laboratory monitoring becomes less frequent after a child has achieved a stable, optimized dose.

We observed a high 25% prevalence of baseline palpable splenomegaly in the SPHERE cohort, with half of these spleens ≥5 cm below the left costal margin. Palpation of the spleen is a relatively imprecise technique for detection of splenomegaly with low sensitivity [42], so in SPHERE we have included sonographic measurement of the spleen in 3 dimensions to calculate splenic volumes more accurately. The calculated volumes did correlate with palpated size. Larger size by palpation and greater volume by ultrasound were associated with lower hemoglobin concentration and platelet count, as well as an association with history of splenic sequestration. Volume by ultrasound revealed a correlation with height, age, and alpha thalassemia status that was not apparent when compared to palpable spleen size. Few previous studies adequately describe an appropriate control population for splenic size in SCA, since they were conducted in a different setting [25], focused on another specific disease [43], included restricted ages [44], or reported only one splenic dimension [45]. These SPHERE data therefore provide a useful reference range for spleen size and volumes in a large pediatric cohort with SCA living in sub-Saharan Africa.

For children with SCA living in the USA, the usual pattern of recurrent vaso-occlusion and tissue infarction leads to functional asplenia and eventual fibrotic involution [4, 46]. In sub-Saharan Africa, however, splenomegaly is a common problem due to parasites such as malaria and schistosomiasis that influence the size and function of the spleen. Palpable splenomegaly is relatively common in young children with SCA [47] and can persist into the third and fourth decades of life [48]. A report that spleen sizes decreased after treatment with proguanil suggested that chronic asymptomatic malaria parasitemia may be due to the spleen harboring malaria [49], but a later study showed no relationship between splenic size, malaria, or proguanil use [50]. For children enrolled in SPHERE, the causes of baseline splenomegaly, functional status of the enlarged spleens, and relationships to parasitic infections are currently under investigation.

As the treatment phase of the SPHERE trial continues, the relationship between splenomegaly and hydroxyurea therapy in sub-Saharan Africa will be followed closely, as the REACH cohort has reported an increased prevalence of palpable splenomegaly over time in association with hydroxyurea escalated to MTD [51]. This relationship and its effects need further elucidation, as the findings have implications for widespread prescription of hydroxyurea for SCA across Africa. SPHERE participants with initial normal TCD exams will also provide contemporary comparison data about the longitudinal effects of hydroxyurea on spleen size and function, and evaluation of splenic filtrative function will improve our understanding of its physiological effects.

In summary, children with SCA in Tanzania have an elevated risk for primary stroke and many have splenomegaly. Fully enrolled, SPHERE has built local clinical capacity with high-quality research infrastructure and TCD screening, and will prospectively determine the benefits of hydroxyurea at MTD for primary stroke prevention and its effects on splenomegaly, as access to hydroxyurea continues to expand access across Tanzania.

Statement of Ethics

The SPHERE trial is approved locally by the Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences (CUHAS) and Bugando Medical Centre (BMC) Combined Research Ethics Committee, approval number CREC/302/2018, nationally by the Tanzanian National Institute for Medical Research's (NIMR) National Health Research Ethics Committee (NatHREC), approval number NIMR/HQ/R.8a/Vol. IX/2952, and the Tanzanian Medicines and Medical Devices Authority (TMDA), approval number TFDA0018/CTR/0016/06, and also by the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) Institutional Review Board, approval number 2018-5483. Written informed consent was obtained from the parent/guardian of each child. Assent was obtained from children ≥10 years old.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Russell E. Ware is a consultant for Nova Laboratories; receives research donations from Bristol Myers Squibb, Addmedica, and Hemex Health; and chairs Data and Safety Monitoring Boards for Novartis and Editas. Susan E. Stuber is a consultant for the American Society of Hematology Research Collaboration. None of these disclosures is relevant to the results and conclusions of the SPHERE trial. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding Sources

Luke R. Smart receives support from a training grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K23 HL153763) and an American Society of Hematology Research Training Award for Fellows. Emmanuela E. Ambrose is supported through an American Society of Hematology Global Research Award.

Author Contributions

Janet Adams, Thad A. Howard, Maria Nakafeero, Sara M. O'Hara, and Primrose Songoro assisted with data collection and review, and critically read, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript. Emmanuela E. Ambrose, Luke R. Smart, and Russell E. Ware conceptualized and designed the trial, analyzed the data, wrote the manuscript, and critically read, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript. Georgina Balyorugulu, Mwesige Charles, Protas Komba, Kathryn E. McElhinney, Jodie Odame, and Idd Shabani assisted with data collection, and critically read, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript.. Adam Lane and Teresa S. Latham analyzed the data, wrote the manuscript, and critically read, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript. Abel N. Makubi critically read, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript. Susan E. Stuber designed the trial and critically read, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Requests for de-identified data may be directed to the corresponding author and must include an IRB-approved proposal. The data that support the findings of this publication are not publicly available due to the ongoing nature of the clinical trial and the need for approval from the Tanzanian national regulatory board. De-identified data will be made available following approval by an internal review committee and execution of a data-sharing agreement between all parties.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients and families of those children with sickle cell anemia who have participated in the study, as well as the pediatrics department and nursing staff, especially Chausiku Paschal.

Clinical Trial Registration: NCT03948867.

Luke R. Smart and Emmanuela E. Ambrose contributed equally.

Funding Statement

Luke R. Smart receives support from a training grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K23 HL153763) and an American Society of Hematology Research Training Award for Fellows. Emmanuela E. Ambrose is supported through an American Society of Hematology Global Research Award.

References

- 1.Ware RE, de Montalembert M, Tshilolo L, Abboud MR. Sickle cell disease. Lancet. 2017;390((10091)):311–323. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balkaran B, Char G, Morris JS, Thomas PW, Serjeant BE, Serjeant GR. Stroke in a cohort of patients with homozygous sickle cell disease. J Pediatr. 1992;120((3)):360–366. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80897-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohene-Frempong K, Weiner SJ, Sleeper LA, Miller ST, Embury S, Moohr JW, et al. Cerebrovascular accidents in sickle cell disease: rates and risk factors. Blood. 1998;91((1)):288–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powars D, Wilson B, Imbus C, Pegelow C, Allen J. The natural history of stroke in sickle cell disease. Am J Med. 1978;65((3)):461–471. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90772-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leikin SL, Gallagher D, Kinney TR, Sloane D, Klug P, Rida W. Immunodeficiency virus infection, adolescents, and the Institutional Review Board. Pediatrics. 1989;10((6)):500–505. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(89)90012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams R, McKie V, Nichols F, Carl E, Zhang DL, McKie K, et al. The use of transcranial ultrasonography to predict stroke in sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 1992;326((9)):605–610. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202273260905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams RJ, McKie VC, Hsu L, Files B, Vichinsky E, Pegelow C, et al. Prevention of a first stroke by transfusions in children with sickle cell anemia and abnormal results on transcranial Doppler ultrasonography. N Engl J Med. 1998;339((1)):5–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807023390102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enninful-Eghan H, Moore RH, Ichord R, Smith-Whitley K, Kwiatkowski JL. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography and prophylactic transfusion program is effective in preventing overt stroke in children with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr. 2010;157((3)):479–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piel FB, Patil AP, Howes RE, Nyangiri OA, Gething PW, Dewi M, et al. Global epidemiology of sickle haemoglobin in neonates: a contemporary geostatistical model-based map and population estimates. Lancet. 2013;381((9861)):142–151. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61229-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grosse SD, Odame I, Atrash HK, Amendah DD, Piel FB, Williams TN. Sickle cell disease in Africa: a neglected cause of early childhood mortality. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41((6 Suppl 4)):S398–405. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdullahi SU, DeBaun MR, Jordan LC, Rodeghier M, Galadanci NA. Stroke recurrence in nigerian children with sickle cell disease: evidence for a secondary stroke prevention trial. Pediatr Neurol. 2019;95:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2019.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matuja SS, Munseri P, Khanbhai K. The burden and outcomes of stroke in young adults at a tertiary hospital in Tanzania: a comparison with older adults. BMC Neurol. 2020;20((1)):206. doi: 10.1186/s12883-020-01793-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhabangi A, Dzik WH, Idro R, John CC, Butler EK, Spijker R, et al. Blood use in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of current data. Transfusion. 2019;59((7)):2446–2454. doi: 10.1111/trf.15280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization . Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2017. Global status report on blood safety and availability 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Opoka RO, Ndugwa CM, Latham TS, Lane A, Hume HA, Kasirye P, et al. Novel use Of Hydroxyurea in an African Region with Malaria (NOHARM): a trial for children with sickle cell anemia. Blood. 2017;130((24)):2585–2593. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-06-788935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tshilolo L, Tomlinson G, Williams TN, Santos B, Olupot-Olupot P, Lane A, et al. Hydroxyurea for children with sickle cell anemia in Sub-Saharan Africa. N Engl J Med. 2019;380((2)):121–131. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1813598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.John CC, Opoka RO, Latham TS, Hume HA, Nabaggala C, Kasirye P, et al. Hydroxyurea dose escalation for sickle cell anemia in Sub-Saharan Africa. N Engl J Med. 2020;382((26)):2524–2533. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2000146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ambrose EE, Smart LR, Charles M, Hernandez AG, Latham T, Hokororo A, et al. Surveillance for sickle cell disease, United Republic of Tanzania. Bull World Health Organ. 2020;98((12)):859–868. doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.253583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sickle cell disease clinical management guidelines. 1st ed. Dodoma: United Republic of Tanzania; 2020. Ministry of health community development, gender, elderly and children; p. p. 47. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization . Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; Child growth standards [Internet] [cited 2022 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.who.int/tools/child-growth-standards. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42((2)):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O'Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams RJ, McKie VC, Brambilla D, Carl E, Gallagher D, Nichols FT, et al. Stroke prevention trial in sickle cell anemia. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19((1)):110–129. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(97)00099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Opoka RO, Hume HA, Latham TS, Lane A, Williams O, Tymon J, et al. Hydroxyurea to lower transcranial Doppler velocities and prevent primary stroke: the Uganda NOHARM sickle cell anemia cohort. Haematologica. 2020;105((6)):e272–e275. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.231407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dittrich M, Milde S, Dinkel E, Baumann W, Weitzel D. Sonographic biometry of liver and spleen size in childhood. Pediatr Radiol. 1983;13((4)):206–211. doi: 10.1007/BF00973157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaefer BA, Kiyaga C, Howard TA, Ndeezi G, Hernandez AG, Ssewanyana I, et al. Hemoglobin variants identified in the Uganda Sickle Surveillance Study. Blood Adv. 2016;1((1)):93–100. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2016000950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGann PT, Williams AM, Ellis G, McElhinney KE, Romano L, Woodall J, et al. Prevalence of inherited blood disorders and associations with malaria and anemia in Malawian children. Blood Adv. 2018;2((21)):3035–3044. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018023069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macharia AW, Mochamah G, Uyoga S, Ndila CM, Nyutu G, Tendwa M, et al. β-Thalassemia pathogenic variants in a cohort of children from the East African coast. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2020;8((7)):e1294. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zimmerman SA, Schultz WH, Burgett S, Mortier NA, Ware RE. Hydroxyurea therapy lowers transcranial Doppler flow velocities in children with sickle cell anemia. Blood. 2007;110((3)):1043–1047. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-057893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hankins JS, Fortner GL, McCarville MB, Smeltzer MP, Wang WC, Li CS, et al. The natural history of conditional transcranial Doppler flow velocities in children with sickle cell anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2008;142((1)):94–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lagunju IA, Labaeka A, Ibeh JN, Orimadegun AE, Brown BJ, Sodeinde OO. Transcranial doppler screening in Nigerian children with sickle cell disease: a 10-year longitudinal study on the SPPIBA cohort. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68((4)):e28906. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sánchez LM, Nieves RM, Latham T, Stuber S, Luden JR, Urcuyo GS, et al. Building capacity to reduce stroke in children with sickle cell anemia in the Dominican Republic: the SACRED trial. Blood Adv. 2018;2((Suppl 1)):50–53. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018GS110818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rankine-Mullings AE, Morrison-Levy N, Soares D, Aldred K, King L, Ali S, et al. Transcranial Doppler velocity among Jamaican children with sickle cell anaemia: determining the significance of haematological values and nutrition. Br J Haematol. 2018;181((2)):242–251. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts N, James S, Delaney M, Fitzmaurice C. The global need and availability of blood products: a modelling study. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6((12)):e606–15. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chou ST, Alsawas M, Fasano RM, Field JJ, Hendrickson JE, Howard J, et al. American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for sickle cell disease: transfusion support. Blood Adv. 2020;4((2)):327–355. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019001143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ngoma AM, Mutombo PB, Ikeda K, Nollet KE, Natukunda B, Ohto H. Red blood cell alloimmunization in transfused patients in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transfus Apher Sci. 2016;54((2)):296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vichinsky EP, Luban NL, Wright E, Olivieri N, Driscoll C, Pegelow CH, et al. Prospective RBC phenotype matching in a stroke-prevention trial in sickle cell anemia: a multicenter transfusion trial. Transfusion. 2001;41((9)):1086–1092. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2001.41091086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ware RE. How I use hydroxyurea to treat young patients with sickle cell anemia. Blood. 2010;115((26)):5300–5311. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-146852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ware RE, Davis BR, Schultz WH, Brown RC, Aygun B, Sarnaik S, et al. Hydroxycarbamide versus chronic transfusion for maintenance of transcranial doppler flow velocities in children with sickle cell anaemia-TCD With Transfusions Changing to Hydroxyurea (TWiTCH): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2016;387((10019)):661–670. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01041-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rankine-Mullings A, Reid M, Soares D, Taylor-Bryan C, Wisdom-Phipps M, Aldred K, et al. Hydroxycarbamide treatment reduces transcranial doppler velocity in the absence of transfusion support in children with sickle cell anaemia, elevated transcranial doppler velocity, and cerebral vasculopathy: the EXTEND trial. Br J Haematol. 2021;195((4)):612–620. doi: 10.1111/bjh.17698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Galadanci NA, Abdullahi SU, Ali Abubakar S, Wudil Jibir B, Aminu H, Tijjani A, et al. Moderate fixed-dose hydroxyurea for primary prevention of strokes in Nigerian children with sickle cell disease: final results of the SPIN trial. Am J Hematol. 2020;95((9)):E247–E250. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grover SA, Barkun AN, Sackett DL. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have splenomegaly? JAMA. 1993;270((18)):2218–2221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kotlyar S, Nteziyaremye J, Olupot-Olupot P, Akech SO, Moore CL, Maitland K. Spleen volume and clinical disease manifestations of severe plasmodium falciparum malaria in African children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2014;108((5)):283–289. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/tru040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eze CU, Agwu KK, Ezeasor DN, Ochie K, Aronu AE, Agwuna KK, et al. Sonographic biometry of spleen among school age children in Nsukka, Southeast, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2013;13((2)):384–392. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v13i2.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kebede T, Admassie D. Spleen length in childhood with ultrasound normal based on age at Tikur Anbessa Hospital. Ethiop Med J. 2009;47((1)):49–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diggs LW. Siderofibrosis of the spleen in sickle cell anemia. JAMA. 1935;104((7)):538–541. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adekile AD, McKie KM, Adeodu OO, Sulzer AJ, Liu JS, McKie VC, et al. Spleen in sickle cell anemia: comparative studies of Nigerian and U.S. patients. Am J Hematol. 1993;42((3)):316–321. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830420313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abjah UM, Aken'Ova YA. Levels of malaria specific immunoglobulin G in Nigerian sickle cell disease patients with and without splenomegaly. Niger J Med. 2003;12((1)):32–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adekile AD, Adeodu OO, Jeje AA, Odesanmi WO. Persistent gross splenomegaly in Nigerian patients with sickle cell anaemia: relationship to malaria. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1988;8((2)):103–107. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1988.11748549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sadarangani M, Makani J, Komba AN, Ajala-Agbo T, Newton CR, Marsh K, et al. An observational study of children with sickle cell disease in Kilifi, Kenya. Br J Haematol. 2009;146((6)):675–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07771.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tshilolo L, Tomlinson GA, McGann PT, Latham TS, Olupot-Olupot P, Santos B, et al. Splenomegaly in children with sickle cell anemia receiving hydroxyurea in sub-Saharan Africa. Blood. 2019;134((Suppl 1)):993. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Requests for de-identified data may be directed to the corresponding author and must include an IRB-approved proposal. The data that support the findings of this publication are not publicly available due to the ongoing nature of the clinical trial and the need for approval from the Tanzanian national regulatory board. De-identified data will be made available following approval by an internal review committee and execution of a data-sharing agreement between all parties.