ABSTRACT

Fungicide applications in agriculture and medicine can promote the evolution of resistant, pathogenic fungi, which is a growing problem for disease management in both settings. Nonpathogenic mycobiota are also exposed to fungicides, may become tolerant, and could turn into agricultural or medical problems, for example, due to climate change or in immunocompromised individuals. However, quantitative data about fungicide sensitivity of environmental fungi is mostly lacking. Aureobasidium species are widely distributed and frequently isolated yeast-like fungi. One species, A. pullulans, is used as a biocontrol agent, but is also encountered in clinical samples, regularly. Here, we compared 16 clinical and 30 agricultural Aureobasidium isolates based on whole-genome data and by sensitivity testing with the 3 fungicides captan, cyprodinil, and difenoconazole. Our phylogenetic analyses determined that 7 of the 16 clinical isolates did not belong to the species A. pullulans. These isolates clustered with other Aureobasidium species, including A. melanogenum, a recently separated species that expresses virulence traits that are mostly lacking in A. pullulans. Interestingly, the clinical Aureobasidium isolates were significantly more fungicide sensitive than many isolates from agricultural samples, which implies selection for fungicide tolerance of non-target fungi in agricultural ecosystems.

IMPORTANCE Environmental microbiota are regularly found in clinical samples and can cause disease, in particular, in immunocompromised individuals. Organisms of the genus Aureobasidium belonging to this group are highly abundant, and some species are even described as pathogens. Many A. pullulans isolates from agricultural samples are tolerant to different fungicides, and it seems inevitable that such strains will eventually appear in the clinics. Selection for fungicide tolerance would be particularly worrisome for species A. melanogenum, which is also found in the environment and exhibits virulence traits. Based on our observation and the strains tested here, clinical Aureobasidium isolates are still fungicide sensitive. We, therefore, suggest monitoring fungicide sensitivity in species, such as A. pullulans and A. melanogenum, and to consider the development of fungicide tolerance in the evaluation process of fungicides.

KEYWORDS: Aureobasidium, fungicide resistance

OBSERVATION

Antifungal compounds are widely applied in agricultural and clinical settings to control fungal diseases. However, fungicide applications in the field or clinics are not specifically targeted to the pathogens but hit all mycobiota equally. We could even argue that fungicide applications predominantly affect non-target organisms, since pathogenic species usually comprise only a small proportion of the total mycobiome. The extensive use of antifungals, thus, poses strong selection pressure on target and non-target populations of fungi, and can lead to the development of resistance in both groups (1–3). Aureobasidium pullulans is an extremotolerant, yeast-like fungus that is highly abundant in most habitats (4, 5). Since it is one of the most frequently isolated fungal species, it is also regularly found in clinical samples, even though it likely does not cause disease in humans (6, 7). As we have shown previously, some agricultural A. pullulans isolates are highly tolerant to the antifungal agents captan (CPN), cyprodinil (CYP), and difenoconazole (DFN), which are commonly used in agriculture (8). CPN belongs to the phthalimide group of fungicides, which have been reported to act on thiol groups, and pose a low risk for resistance development (9, 10). CYP is an anilinopyrimidine that inhibits the biosynthesis of sulfur-containing amino acids and their precursors (e.g., methionine, cysteine, cystathionine, and homocysteine) (11). DFN is an azole, which is a broad-spectrum fungicide that is widely used in agriculture and clinics (12). Compounds of this class target, the cytochrome P450 enzyme lanosterol 14-α-demethylase (coded for by the ERG11 or CYP51A gene), and resistance to azoles is widespread and well documented (13, 14).

We have previously described highly fungicide tolerant A. pullulans isolates from agricultural samples (8), but it was not clear if this low sensitivity is a general characteristic of this species, or has been selected for by repeated fungicide exposure, which would represent a largely neglected and unintended side effect of fungicide use. To better understand fungicide sensitivity in A. pullulans, 16 clinical isolates were obtained from Swiss hospitals or the Westerdijk fungal culture collection (Table S1). Genome analyses and sensitivity assays were used to compare these strains with 30 isolates from agricultural soil and plant samples (from apple orchards that were not treated with fungicides) (8).

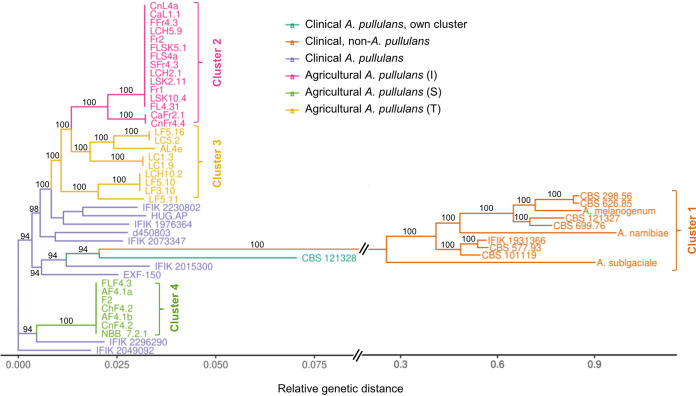

Based on our phylogenetic analysis, most isolates exhibited short relative distances to each other or were almost identical (Fig. 1). Only cluster 1, comprised of reference species and 7 of our strains (i.e., CBS 626.85, CBS 298.56, CBS 699.76, CBS 121327, CBS 101119, CBS 577.93, and IFIK 1931366), showed a large relative distance to all other isolates. Interestingly, these 7 isolates all originated from clinical samples and clustered together with the non-A. pullulans reference strains A. melanogenum, A. namibiae, and A. subglaciale. Due to the large genetic distance between these non-A. pullulans isolates (cluster 1) and all other isolates, a subsequent hierarchical clustering was performed with only the A. pullulans sequences. Based on this analysis, 3 clusters with exclusively agricultural isolates were defined. These 3 clusters (2, 3, and 4 in Fig. 1) corresponded to the previously reported groupings based on fungicide sensitivity (e.g., intermediate [I], tolerant [T], or sensitive [S] isolates, respectively) (8). In contrast, the clinical A. pullulans isolates showed larger genetic distances with lower bootstrap support (<90), and did not all form a single clade. The clinical isolate CBS 121328 differed the most from the other A. pullulans isolates and formed its own cluster, but was an order of magnitude less divergent than the non-A. pullulans cluster 1 isolates. Since none of the clinical isolates fell into one of the well-resolved clusters of agricultural isolates, a nonagricultural pool of A. pullulans was likely the source of these isolates that were encountered in the clinics.

FIG 1.

SNP-based phylogeny of 46 Aureobasidium strains from agricultural and clinical samples. Many clinical Aureobasidium isolates cluster more closely with other Aureobasidium species than with A. pullulans. As references, the analysis included 5 genomes of the 4 Aureobasidium species A. pullulans (NBB 7.2.1 and EXF-150), A. namibiae (EXF-3398), A. melanogenum (CBS 110374), and A. subglaciale (EXF-2481) (7, 15). The x axis represents the relative distances between the taxa. The x axis is discontinuous, as is indicated by the double line to fit the taxa of the genetically distant cluster 1. The numbers of the branches indicate bootstrap values of 100 bootstrap replicates and values <90 are not shown.

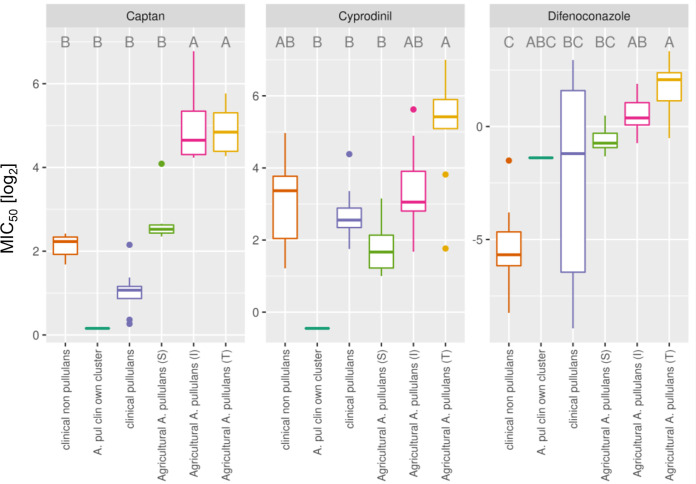

To determine if fungicide sensitivity also correlated with genetic difference in this larger collection of isolates, and based on whole-genome data, the MIC50 values for CAN, CYP, and DFN were determined for all Aureobasidium isolates (Fig. 2). Overall, the cluster type (i.e., clinical A. pullulans, clinical non-A. pullulans, agricultural sensitive, agricultural intermediate, and agricultural tolerant) had a significant effect on the MIC50 values for all 3 fungicides (Padj ≤ 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis-Test, see gitlab repository at the link below). Based on these experiments, the clinical isolates exhibited comparable MIC50 values as the sensitive, agricultural isolates for all 3 fungicides (blue and green box plots) (Fig. 2). The MIC50 values for these clinical and sensitive, agricultural A. pullulans isolates were significantly lower than those for the tolerant agricultural isolates for all 3 fungicides (Padj ≤ 0.05, Dunn’s-Test). These results indicated that the tolerant phenotype of the agricultural A. pullulans was not a general property of the species, but likely selected for by the fungicide applications in agriculture.

FIG 2.

Clinical Aureobasidium isolates are more sensitive to captan, cyprodinil, and difenoconazole than many agricultural isolates. Boxplot of the MIC50 values (log2) for each group of isolates derived from the phylogenetic tree and for the 3 fungicides captan (CAN), cyprodinil (CYP), and difenoconazole (DFN). For 2 isolates that were not controlled at the maximum CYP concentration, 128 μg/mL (the highest concentration tested) was set as the MIC50 value. Different letters indicate statistical significance based on the Dunn’s-Test (Padj ≤ 0.05).

In summary, all clinical Aureobasidium isolates, even those not belonging to the species A. pullulans, were sensitive to the fungicides tested here, and significantly more sensitive than many agricultural isolates. Consequently, the patients carrying these strains must have acquired them from populations of sensitive Aureobasidium stains and likely not from agricultural environments. The observation that many agricultural A. pullulans isolates were tolerant to the fungicides tested here, supports the conclusion that agricultural fungicide applications can select for tolerance in non-target fungi. Selection for fungicide tolerance would be particularly worrisome for the clinically relevant species A. melanogenum. This species is also found in the environment, but is known to exhibit virulence traits, such as growth at 37°C, siderophore production, or hemolytic activity that are mostly lacking in A. pullulans (6, 7). However, the A. melanogenum isolates tested here mostly exhibited high fungicide sensitivity. Overall, these results highlight that antifungal interventions affect the entire mycobiome, and can cause population shifts in non-target fungi due to the selection of tolerant genotypes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

All strains used or generated during this study are listed in Table S1. A total of 30 environmental A. pullulans strains have been characterized in the past (8). Further, 16 clinical Aureobasidium strains have been obtained from Swiss hospitals or the Westerdijk fungal culture collection (Table S1). All isolates were maintained on potato dextrose agar ([PDA]; Difco; Chemie Brunschwig AG) at 22°C.

Genome sequencing.

Genomic DNA was extracted as previously described (15), and whole-genome sequencing (150 bp paired end reads) was performed at BGI Genomics. The reference isolate A. pullulans NBB 7.2.1 was originally isolated from a soil sample and characterized by genome, transcriptome, and secretome analyses (15, 16). For phylogenetic analysis, the genomes of A. pullulans EXF-150, A. melanogenum CBS 110374, A. namibiae EXF-3398, and A. subglaciale EXF-2481 were included (7) (all available at https://mycocosm.jgi.doe.gov). De novo genome assembly was performed with SPAdes by using the default options (17). A phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary (PHaME) analysis was carried out according to the developer’s instructions (18). The genetic distances calculated by PHaME were used to delineate 6 clusters, and to generate a phylogenetic tree using the RaxML method. The control files and R documentation for reproducing the analysis are all available at https://github.com/Luknaegeli/Apul_clinical, and sequencing reads have been deposited at NCBI in the bioproject PRJNA897728, under the accession number SAMN31580265 for the agricultural, and SAMN31634356 for the clinical isolates.

Sensitivity testing.

The microbroth sensitivity assays of 16 clinical isolates (Table S1) to CYP, CPN, DFN, and their subsequent MIC50 causing reduction in growth to 50% values were determined as previously reported (8). Each growth experiment was repeated at least 3 times.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Lena Dändliker for help with experimental work and DNA extractions, and numerous colleagues at Agroscope for helpful discussions during the preparation of this manuscript. The work was supported by Agroscope, the Swiss Expert Committee for Biosafety (SECB) of the Swiss Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN), and the grant 31003A_175665/1 from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) to FMF.

We declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Florian M. Freimoser, Email: florian.freimoser@agroscope.admin.ch.

Damian J. Krysan, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics

REFERENCES

- 1.Fisher MC, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Berman J, Bicanic T, Bignell EM, Bowyer P, Bromley M, Brüggemann R, Garber G, Cornely OA, Gurr SJ, Harrison TS, Kuijper E, Rhodes J, Sheppard DC, Warris A, White PL, Xu J, Zwaan B, Verweij PE. 2022. Tackling the emerging threat of antifungal resistance to human health. Nat Rev Microbiol 20:557–571. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00720-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gow NAR, Johnson C, Berman J, Coste AT, Cuomo CA, Perlin DS, Bicanic T, Harrison TS, Wiederhold N, Bromley M, Chiller T, Edgar K. 2022. The importance of antimicrobial resistance in medical mycology. Nat Commun 13:5352. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32249-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kang SE, Sumabat LG, Melie T, Mangum B, Momany M, Brewer MT. 2022. Evidence for the agricultural origin of resistance to multiple antimicrobials in Aspergillus fumigatus, a fungal pathogen of humans. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 12:jkab427. doi: 10.1093/g3journal/jkab427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gostincar C, Muggia L, Grube M. 2012. Polyextremotolerant black fungi: oligotrophism, adaptive potential, and a link to lichen symbioses. Front Microbiol 3:390. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gostincar C, Turk M, Zajc J, Gunde-Cimerman N. 2019. Fifty Aureobasidium pullulans genomes. Environ Microbiol 21:3638–3652. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Černoša A, Sun X, Gostinčar C, Fang C, Gunde-Cimerman N, Song Z. 2021. Virulence traits and population genomics of the black yeast Aureobasidium melanogenum. JoF 7:665. doi: 10.3390/jof7080665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gostincar C, Ohm RA, Kogej T, Sonjak S, Turk M, Zajc J, Zalar P, Grube M, Sun H, Han J, Sharma A, Chiniquy J, Ngan CY, Lipzen A, Barry K, Grigoriev IV, Gunde-Cimerman N. 2014. Genome sequencing of four Aureobasidium pullulans varieties: biotechnological potential, stress tolerance, and description of new species. BMC Genomics 15:549. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magoye E, Hilber-Bodmer M, Pfister M, Freimoser FM. 2020. Unconventional yeasts are tolerant to common antifungals, and Aureobasidium pullulans has low baseline sensitivity to captan, cyprodinil, and difenoconazole. Antibiotics 9:602. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9090602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernard BK, Gordon EB. 2000. An evaluation of the common mechanism approach to the food quality protection act: captan and four related fungicides, a practical example. Int J Toxicol 19:43–61. doi: 10.1080/109158100225033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brent KJ, Hollomon DW. 2007. Fungicide resistance: the assessment of risk. Fungicide Resistance Action Committee, Vero Beach, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fritz R, Lanen C, Colas V, Leroux P. 1997. Inhibition of methionine biosynthesis in Botrytis cinerea by the anilinopyrimidine fungicide pyrimethanil. Pestic Sci 49:40–46. doi:. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heusinkveld HJ, Molendijk J, van den Berg M, Westerink RHS. 2013. Azole fungicides disturb intracellular Ca2+ in an additive manner in dopaminergic PC12 cells. Toxicol Sci 134:374–381. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monk BC, Sagatova AA, Hosseini P, Ruma YN, Wilson RK, Keniya MV. 2020. Fungal Lanosterol 14α-demethylase: a target for next-generation antifungal design. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom 1868:140206. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2019.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snelders E, van der Lee HAL, Kuijpers J, Rijs AJMM, Varga J, Samson RA, Mellado E, Donders ART, Melchers WJG, Verweij PE. 2008. Emergence of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus and spread of a single resistance mechanism. PLoS Med 5:e219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rueda-Mejia MP, Nägeli L, Lutz S, Hayes RD, Varadarajan AR, Grigoriev IV, Ahrens CH, Freimoser FM. 2021. Genome, transcriptome and secretome analyses of the antagonistic, yeast-like fungus Aureobasidium pullulans to identify potential biocontrol genes. Microb Cell 8:184–202. doi: 10.15698/mic2021.08.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hilber-Bodmer M, Schmid M, Ahrens CH, Freimoser FM. 2017. Competition assays and physiological experiments of soil and phyllosphere yeasts identify Candida subhashii as a novel antagonist of filamentous fungi. BMC Microbiol 17:4. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0908-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prjibelski A, Antipov D, Meleshko D, Lapidus A, Korobeynikov A. 2020. Using SPAdes de novo assembler. Curr Protocols Bioinf 70:e102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shakya M, Ahmed SA, Davenport KW, Flynn MC, Lo C-C, Chain PSG. 2020. Standardized phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analysis applied to species across the microbial tree of life. Sci Rep 10:1723. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58356-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material. Download spectrum.05299-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 0.2 MB (218.2KB, pdf)