ABSTRACT

The formation of hyphae is a key virulence attribute of Candida albicans as they are required for adhesion to and invasion of host cells, and ultimately deep-tissue dissemination. Hyphae also secrete the peptide toxin candidalysin, which is crucial for destruction of host cell membranes. The peptide is derived from a precursor protein encoded by the gene ECE1 which is strongly induced during hyphal growth. Previous studies revealed a very complex regulation of this gene involving several transcription factors. However, the promoter of the gene is still not characterized. Here, we present a functional analysis of the intergenic region upstream of the ECE1 gene. Rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE)-PCR was performed to identify the 5′ untranslated region, which has a size of 49 bp regardless of the hyphae-inducing condition. By using green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter constructs we further defined a minimal promoter length of 1,500 bp which was verified by RT-qPCR. Finally, we identified the TATA element required for the expression of the gene. It is located 106 to 109 bp upstream of the ECE1 start codon. Our results illustrate that despite a very short 5′ UTR, a relatively long promoter is required to secure ECE1 transcription, indicating a complex regulatory machinery tightly controlling the expression of the gene.

IMPORTANCE In recent years it was shown that secretion of the toxic peptide candidalysin from hyphae of the major human fungal pathogen Candida albicans contributes heavily to its virulence. The peptide is derived from a precursor protein which is encoded by the ECE1 gene whose transcription is known to be closely associated with formation of hyphae. Here, we used a GFP reporter system to determine the length of the ECE1 promoter and were able to show that it has a minimal size of 1,500 bp. Surprisingly, the gene has a very short 5′ UTR of only 49 bp. In accordance with this, the TATA element required for transcription is located 106 to 109 bp upstream of the start codon. This indicates that ECE1 expression is controlled by a very long promoter allowing a complex network of transcription factors to contribute to the gene’s regulation.

KEYWORDS: Candida albicans, ECE1, promoters

INTRODUCTION

Candidalysin is a cytolytic peptide toxin secreted from hyphae of the opportunistic human fungal pathogen Candida albicans (1). Initially, it was observed that the peptide causes necrotic damage of infected human epithelial cells (1–3), a process which is required for consequent translocation through intestinal barriers (4). Based on these initial findings it was later discovered that candidalysin influences a variety of immunoregulatory mechanisms, including the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome (5, 6), neutrophil recruitment (7, 8), and release of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-17, IL-36, IL-1-α, IL-1-β, and IL-8 (9, 10). In infected oral epithelial cells, it also triggers the phosphorylation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and activation of the Eph2-EGFR signaling pathway (11, 12). In addition, candidalysin can induce alarmin and antimicrobial peptide release in epithelial cells (13).

Aside from these distinct effects in the interaction between fungal and immune cells, candidalysin participates in more complex relations between the host and C. albicans. Recent works revealed its contributions to the development of allergic airway disease (14) and alcoholic hepatitis (15). The colonization of the gut by C. albicans is controlled by the adaptive immune system (16), yet this interplay also includes a modulation of Th17 cell response by the fungus also present in other host niches (17). Particularly, candidalysin seems to contribute to the establishment of C. albicans commensalism in the gut (18). Further, candidalysin can also be neutralized by serum albumin (19). This peptide is derived from a precursor protein encoded by the C. albicans ECE1 gene, which is heavily processed in a Kex2/Kex1-dependent manner, resulting in several peptides of which only candidalysin seems to act as a toxic peptide (1, 20–22). Orthologs of this gene are only found in C. dubliniensis and C. tropicalis which are the closest relatives of C. albicans, but no other members of the CTG clade (20).

ECE1 mRNA is the most abundant one in C. albicans hyphae but is hardly found in yeast cells (23). In the past, several transcription factors were identified which contributed to the complex regulation of the gene in response to different environmental stimuli. Most of these regulators were also shown to be involved in the control of fungal morphology, underlining the tight link between yeast-to-hypha transition and ECE1 regulation (23–30). The gene also belongs to the small group of core filamentation response (CFR) genes which are always induced during hyphal growth, independent from the hyphae-inducing stimulus (23). Seven of these CFR genes are characterized by large 5′ intergenic regions (IR) of 2,000 bp and more (23). These extended intergenic regions might be suggestive of complex regulatory mechanisms for those genes, which are often linked to fungal morphology and virulence (31, 32). So far, for all but one gene (ALS3) the exact length of the promoters is unknown (33). Long upstream intergenic regions can contribute to fine-tuning of the transcriptional and translational control in C. albicans, which was previously shown for UME6. Here, the large 5′ untranslated region (5′ UTR) can inhibit translation of the mRNA (34). It is likely that these long intergenic regions upstream of the CFR genes are likewise linked to their transcriptional control. As seen in the current assembly 22 of the C. albicans genome, not only CFR genes are characterized by such long upstream regions but also morphology-associated transcriptional regulator genes like AHR1, BRG1, EFG1, and NRG1 (35).

Here, we present a functional analysis of the 5′-intergenic region of the C. albicans ECE1 gene. Via green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter constructs we defined a minimal promoter required for full-level expression of ECE1. Further we utilized 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE)-PCR to identify the length of the 5′ UTR and located the central TATA regulatory element.

RESULTS

Defining the 5′ intergenic region of ECE1.

ECE1 is located on chromosome 4. The current assembly of the of the C. albicans genome shows three small open reading frames (ORFs) upstream of ECE1. All of them have a size of approximately 500 bp and are annotated as C4_03480C (588 bp), C4_03490C (525 bp), and C4_03500C (552 bp). A gene with verified function, HWP2, is located upstream of them (Fig. 1 A). There is currently no predicted or experimentally verified function for any of the three small. As a basic transcription was described for all of them, they might have a yet unknown biological relevance (31). According to these annotations, we defined the 5′ intergenic region of ECE1 as the distance between the start codon of the gene and the stop codon of C4_03480C/orf.19.3375, resulting in a size of 3,197 bp (Fig. 1A). This putative promoter region contains allele-specific sequence differences. The first 1,000 bp upstream of the ECE1 start codon are identical, while most of the differences can be detected between 1,000 and 2,000 bp upstream of ATG (Fig. 1B). Here, the identity between the two alleles is only 96.8%. The region between 2,000 and 3,197 bp upstream of the start codon shares 98.2% identity (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

Features of the C. albicans ECE1 gene locus. (A) Location of ECE1 and its neighboring genes on chromosome 4 of C. albicans SC5314 according to the Candida Genome Database. (B) Comparison of the 5′ intergenic region (IR) of ECE1 alleles A and B. Identities between both sequences are shown.

The size of the 5′ untranslated region is independent from the hyphal growth stimulus.

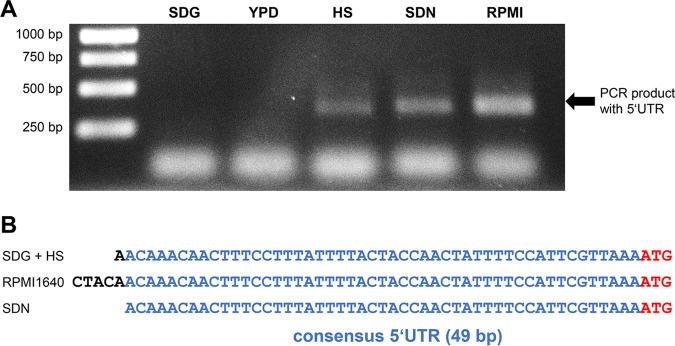

RNA-seq data from previous studies and this work revealed a short size of approximately 50 bp for the ECE1 5′ UTR (35, 36). We used 5′ RACE-PCR to verify these observations and analyze the length of the 5′ UTR under three different hyphae-inducing conditions: (i) transfer from SDG minimal medium to SDG with 10% human serum; (ii) transfer from SDG medium to SD medium with N-acetylglucosamine as carbon source instead of glucose; and (iii) transfer from yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) to RPMI 1640 medium. The 5′ RACE-PCR was performed after 60 min of incubation. A PCR product corresponding to the 5′ UTR was neither observed in YPD nor synthetically defined glucose medium (SDG) medium, which was expected as C. albicans exclusively grows in yeast form in both media (Fig. 2). A 5′ UTR could be detected in all three hyphae-inducing media with a consistent size. The consensus 5′ UTR was 49 bp (Fig. 2). This verified the length of the ECE1 5′ UTR as short and independent from the environmental stimulus that triggers filamentation.

FIG 2.

Determination of the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of the ECE1 mRNA. 5′ RACE-PCR was performed with RNA from yeast-promoting media (YPD and SDG) and hyphae-inducing media (SDG + human serum [HS], SDN and RPMI). (A) PCR fragments after separation on an 1% agarose gel. These fragments contain the 5′ UTR. (B) PCR fragments from hyphae-inducing conditions were sequenced and aligned. The consensus 5′ UTR sequence is shown in blue; the start codon of ECE1 is marked in red.

Identification of the promoter length with a GFP reporter system.

Next, we wanted to identify the actual length of the ECE1 promoter in the 5′ intergenic region and the minimal sequence length required for full-level expression. For this purpose, we established a GFP reporter system. At first, truncated versions of the 5′ intergenic region upstream of the ECE1 starting codon with the sizes 500 bp, 1,000 bp, 1,500 bp, 2,000 bp, 2,500 bp, and 3,000 bp were fused to GFP. Sequences of the truncated ECE1 5′ IR versions were identical to the allele A of the ECE1 gene locus. The resulting constructs were integrated into the transcriptionally neutral NEUT5L locus of wild-type strain SC5314. The mutants were then monitored for GFP signals upon hyphae-induction. No GFP signal was observed for strains carrying the pECE1500-GFP and the pECE11000-GFP constructs after 1 or 2 h of hyphal growth (Fig. 3). For constructs with 1,500 bp 5′ IR or longer, we noticed GFP fluorescence after 1 and 2 h of hyphae induction (Fig. 3). Therefore, we concluded that GFP expression required at least 1,500 bp of the 5′ intergenic region, while only the first 1,000 bp are insufficient to elicit expression.

FIG 3.

Characterization of the ECE1 promoter with a GFP reporter system. Truncated versions of the 5′ intergenic region of ECE1 were fused to GFP as indicated. The resulting GFP reporter strains were grown in SDG medium with 10% human serum for 1 and 2 h prior to microscopy. Pictures were taken from the DIC and GFP channel. Scale bar: 10 μm.

According to these observations, the region between 1,000 and 1,500 bp upstream of the ECE1 start codon appears crucial for full expression of the gene. To further specify this, we next designed ECE1 promoter-GFP constructs of 1,100-, 1,200-, 1,300-, and 1,400-bp length (Fig. 4A). Surprisingly, no GFP fluorescence was detected in strains which carried these constructs. Only after 2 h, faint GFP signals were visible in some but not all cells (Fig. 4A). These observations were verified by RT-qPCR results, where GFP under the control of less than 1,500 bp of the 5′ intergenic region had decreased expression compared to the pECE11500 construct (Fig. 4B). Taken together, we defined 1,500 bp as the minimal length of the ECE1 promoter.

FIG 4.

A minimal promoter length of 1,500 bp is required for ECE1 transcription. The 5′ IR of ECE1 of the indicated length between 1,100 and 1,400 bp was fused to GFP. (A) Cells of the indicated strains were grown in SDG medium with 10% human serum for 1 and 2 h prior to microscopy. Pictures were taken from the DIC and the GFP channel. Scale bar: 10 μm. (B) GFP expression measured by RT-qPCR from total RNA of cells carrying the indicated constructs. Strains were incubated in SDG medium with 10% human serum for 1 h. GFP expression is shown relative to GFP expression under the ADH1 promoter in a strain cultured in the same condition. Asterisks mark significant differences in gene expression (P ≤ 0.05 in a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test).

Identification of the TATA box required for the activation of ECE1 expression.

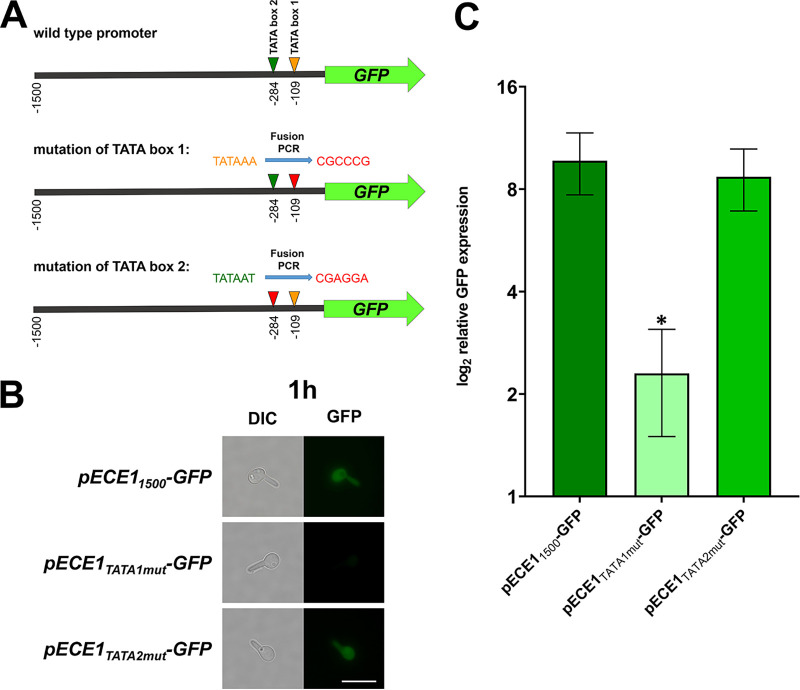

The previous experiments in this study showed that the minimal length of the ECE1 promoter is 1,500 bp and the size of the consensus 5′ UTR is 49 bp. Within this range, we found two TATA elements which are the most likely candidates for ECE1 activation. The first element was found 109 bp and the second element 284 bp upstream of the starting codon (Fig. 5A). To study the influence of both TATA elements on ECE1 transcription we used PCR-based site directed mutagenesis within the pECE1-GFP construct, resulting in a loss of the TATA elements in the respective promoters (Fig. 5A).

FIG 5.

Identification of the TATA element required for ECE1 transcription. (A) The promoter of ECE1 contains two TATA elements which might be required for transcription of the gene. They are marked by triangles. Both TATA elements were replaced by non-TATA sequences by fusion PCR. The resulting promoter constructs were then cloned into the GFP reporter system and integrated into C. albicans SC5314. (B) The resulting mutants were grown for 1 h in SDG with 10% human serum at 37°C prior to fluorescence microscopy. Pictures from the GFP and the DIC channels as well as an overlay of both channels are shown. Scale bar: 10 μm. (C) Total RNA was isolated at the same time points and used for RT-qPCR. GFP expression was normalized against GFP under the control of the ADH1 promoter. The log2 values of the relative gene expression are displayed. Asterisks mark significant differences in gene expression (P ≤ 0.05 in a two-tailed, unpaired Student's t test).

After initiation of hyphal growth, the GFP reporter strain with the nonmutated minimal ECE1 promoter showed a bright fluorescence signal (Fig. 5B). The mutation of the first TATA element resulted in a complete loss of GFP fluorescence (Fig. 5B), while the mutation of the second TATA element resulted in less intense GFP signal compared to the wild-type promoter (Fig. 5B). Via RT-qPCR, we confirmed the significantly lower GFP expression due to mutation of the first TATA element (Fig. 5C). However, GFP expression was not significantly different from the wild-type promoter when the second TATA element was mutated (Fig. 5C).

DISCUSSION

Unusual long upstream intergenic regions are commonly found in C. albicans genes involved in processes such as adhesion, hyphal morphogenesis, biofilm formation, or white-opaque switching. They often correlate with 5′ UTRs of more than 500 bp (31, 32). These 5′ UTRs are sometimes involved in the regulatory postranscriptional regulatory mechanisms, as shown for the transcription factor gene UME6 (34). During yeast growth, translational efficiency was found to be suppressed through this secondary structure within the 5′ UTR. Once this region was deleted, protein levels of Ume6 increased, but abundance of the according mRNA remained the same (34). Therefore, one could speculate that long 5′ intergenic regions of the virulence-related and hyphae-associated CFR genes contribute to their complex expression regulation.

Thus, we were interested if a similar mechanism contributes to the regulation of the ECE1 gene. Its 5′ IR has a size of 3,197 bp which is well above the average size of IR found in the C. albicans genome (23, 31). However, in sharp contrast the 5′ UTR of ECE1 is notably small. In accordance with previous works, we identified a consensus size of 49 bp in three different filament-inducing media (31, 37). This is well below the mean length of C. albicans 5′ UTRs which is 88 bp (32). Fittingly, we identified an essential TATA element, located 109 bp upstream of the start codon. This distance is within a range that is normal for yeasts (38). Loss of function mutations of this element lead to absent fluorescence in a GFP reporter system, indicating that this TATA box is central for activation of the ECE1 transcription. Yet, the potential role of the second, more upstream TATA element is not fully clear, as the results of the GFP reporter strains and RT-qPCR validation were ambiguous (Fig. 5). The role of the TATA elements might be different under other hyphae-inducing or environmental conditions. However, as the 5′ UTR size is almost identical for hyphae induction by serum, neutral pH, and N-acetylglucosamine, we propose that the -109 TATA element is the essential one for ECE1 transcription.

Based on our GFP reporter experiments with truncated versions of the 5′ intergenic region of ECE1, we verified that the minimal size for full-level expression is 1,500 bp and likely represents the core promoter. With this size, the minimal ECE1 promoter is considerably longer than the average C. albicans promoter, which has a mean length of 623 bp (39).

Surprisingly, we observed no fluorescence for promoter constructs with less than 1,500 bp, indicating that a critical region must be located between 1,400 and 1,500 bp upstream of the start codon. Such critical regions were also identified for ALS3 and HWP1, two other CFR genes (33, 40, 41). In both cases, the regions required for gene activation under hyphal growth conditions are located more than 1,000 bp upstream of the start codon, similar to ECE1 (33, 41). It was already speculated for ALS3 that the more distant activation regions might contribute to an enhanced expression of the gene while an activation region closer to the TATA box is required for basic transcription (33).

An obvious explanation of the nature of the critical element located between 1,400 and 1,500 bp of the 5′ IR of ECE1 could be transcription factor binding sites, required for gene induction upon hyphae-induction. Putative binding sites of transcriptional regulators were previously mapped to the 5′ IR of ECE1 (30). According to this mapping, the minimal promoter of ECE1 contains putative binding sites for the transcription factors Ahr1, Bcr1, Brg1, Efg1, Fkh2, Mcm1, Ndt80, Nrg1, and Ume6 (30). However, physical evidence for binding was so far only provided for Ahr1 (30). Interestingly, none of these regulators putatively bind to the region between 1,400 and 1,500 bp upstream of the start codon. Thus, potential binding events and the identity of the regulatory proteins remain elusive.

We previously showed that Tup1 is essential for efficient repression and activation of ECE1 (30). So far, localization of the Tup1 binding to the ECE1 promoter is unknown. It is also unclear if there is a direct binding of this factor or one mediated by cofactors like Nrg1. The restriction of the minimal promoter might ease future experiments as they can focus on this region to analyze the physical binding of transcriptional regulators.

According to the current assembly of the C. albicans genome, most of the other CFR genes possess 5′ IRs of more than 2,000 bp (35). Interestingly, the genome analysis by Bruno et al. (31) indicated that the size of the 5′ UTRs of ALS3, HWP1, and IHD1 was also only around 50 bp, similar to the 5′ UTR of ECE1. It might be that these virulence-associated genes spare the possibility of 5′ UTR-mediated regulation. Considering their central functions, high and quick expression in response to environmental stimuli might be ensured in a manner of an all or nothing expression. Future experiments will elucidate if ECE1 and CFR genes are indeed primarily transcriptionally regulated and if posttranslational mechanisms contribute to their abundance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. albicans strains, growth conditions, and media.

In this study, we used the wild-type strain SC5314 (36) or derivates of it. All strains are listed in Table 1. They were routinely grown in YPD (20 g/L glucose, 10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L casein peptone) or SDG (20 g/L glucose, 6.7 g/L yeast nitrogen base without amino acids) medium at 37°C. For solid medium, 20 g/L agar were added. Hyphal growth was induced by the addition of 10% human serum (Sigma-Aldrich) to SDG medium.

TABLE 1.

C. albicans strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| SC5314 | Wild type | (37) |

| pADH1-GFP | SC5314, ADH1/adh1::GFP-SAT1 | (42) |

| pECE1-GFP | SC5314, ECE1/ece1::GFP-SAT1 | (1) |

| pECE1500-GFP | SC5314, NEUT5L/neut5l::pECE1500-GFP-SAT1 | This work |

| pECE11000-GFP | SC5314, NEUT5L/neut5l::pECE11000-GFP-SAT1 | This work |

| pECE11500-GFP | SC5314, NEUT5L/neut5l::pECE11500-GFP-SAT1 | This work |

| pECE12000-GFP | SC5314, NEUT5L/neut5l::pECE12000-GFP-SAT1 | This work |

| pECE12500-GFP | SC5314, NEUT5L/neut5l::pECE12500-GFP-SAT1 | This work |

| pECE13000-GFP | SC5314, NEUT5L/neut5l::pECE13000-GFP-SAT1 | This work |

| pECE11100-GFP | SC5314, NEUT5L/neut5l::pECE11100-GFP-SAT1 | This work |

| pECE11200-GFP | SC5314, NEUT5L/neut5l::pECE11200-GFP-SAT1 | This work |

| pECE11300-GFP | SC5314, NEUT5L/neut5l::pECE11300-GFP-SAT1 | This work |

| pECE11400-GFP | SC5314, NEUT5L/neut5l::pECE11400-GFP-SAT1 | This work |

| pECE1T1mut-GFP | SC5314, NEUT5L/neut5l::pECE1T1mut-GFP-SAT1 | This work |

| pECE1T2mut-GFP | SC5314, NEUT5L/neut5l::pECE1T2mut-GFP-SAT1 | This work |

Construction of plasmids for the pECE1-GFP reporter system.

Bluescript pSK (Agilent Technologies; Table 2) was used as a template for all constructed plasmids. At first, the C. albicans ACT1 terminator was amplified from genomic C. albicans SC5314 DNA with the oligonucleotide primers 5′CaACT1term-EcoRI and 3′CaACT1term-SpeI (Table 3). The terminator was then cloned into pSK via EcoRI/SpeI. Second, C. albicans optimized GFP was amplified from pSK-CaGFP (42) with primers 5′GFP-XhoI and 3′GFP-EcoRV and then cloned into pSK with the CaACT1 terminator. In a third step, the CaSAT1 gene, including the CaACT1 promoter, CaSAT1 ORF and CaURA3 terminator, was excised from pSK-CaGFP with NotI and then cloned into NotI-restricted pSK with CaACT1 terminator and GFP. In a next step, the 5′ homology region to the NEUT5L locus was amplified with primers 5′NEUfwd-ApaI and 5′NEUrev-ANP-XhoI. The latter oligonucleotide contained additional restriction sites for AscI and NarI. The resulting PCR fragment was cloned via ApaI and XhoI into ApaI/XhoI-restricted pSK with GFP, CaACT1 terminator and SAT1. The 3′ homology region of NEUT5L was then amplified with primers 3′NEUfwd-SacII and 3’′NEUT5L-SacI-PacI and then cloned via SacII/SacI into SacII/SacI-restricted pSK with the other fragments. Finally, the first 500 bp upstream of the ECE1 start codon were amplified with oligonucleotide primers 5′ECE1prom500-AscI and 3′ECE1prom-XhoI. The amplified 500-bp fragment was then cloned into pSK-GFP-SAT1 with NEUT5L homology regions via AscI/XhoI. The resulting plasmid was then called pSK-pECE1500-GFP-SAT1 (Table 2). All other plasmids with the truncated versions of the C. albicans ECE1 promoter were derived from this plasmid by replacing the 500-bp fragment against PCR products of 3′ECE1prom-XhoI and 5′ECE1promX-AscI primers. X stands for the respective sizes of the promoter fragments. Cloning was performed by using the AscI and XhoI restriction sites. All constructed plasmids are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Features | Source |

|---|---|---|

| pSK bluescript | Bluescript plasmid with AmpR | Agilent |

| pSK-pECE1500-GFP-SAT1 | pSK, pECE1500 fused to GFP, SAT1 as selection marker, and homology regions for integration into CaNEUT5L locus | This work |

| pSK-pECE11000-GFP-SAT1 | pSK, pECE11000 fused to GFP, SAT1 as selection marker, and homology regions for integration into CaNEUT5L locus | This work |

| pSK-pECE11500-GFP-SAT1 | pSK, pECE11500 fused to GFP, SAT1 as selection marker, and homology regions for integration into CaNEUT5L locus | This work |

| pSK-pECE12000-GFP-SAT1 | pSK, pECE12000 fused to GFP, SAT1 as selection marker, and homology regions for integration into CaNEUT5L locus | This work |

| pSK-pECE12500-GFP-SAT1 | pSK, pECE12500 fused to GFP, SAT1 as selection marker, and homology regions for integration into CaNEUT5L locus | This work |

| pSK-pECE13000-GFP-SAT1 | pSK, pECE13000 fused to GFP, SAT1 as selection marker, and homology regions for integration into CaNEUT5L locus | This work |

| pSK-pECE1T1Mut-GFP-SAT1 | pSK, pECE11500 with mutated TATA box 1 (−109), fused to GFP, SAT1 as selection marker, and homology regions for integration into CaNEUT5L locus | This work |

| pSK-pECE1T2Mut-GFP-SAT1 | pSK, pECE11500 with mutated TATA box 2 (−284), fused to GFP, SAT1 as selection marker, and homology regions for integration into CaNEUT5L locus | This work |

TABLE 3.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Name | Sequence in 5′ to 3′ directiona |

|---|---|

| 5′GFP-XhoI | AGCTctcgagATGAGTAAGGGAGAAGAACTTTTCACTGGA |

| 3'GFP-EcoRV | AGCTgatatcTTATTTGTATAGTTCATCCATGCCATGTGT |

| 5′CaACT1term-EcoRI | AGCTgaattcGAGTGAAATTCTGGAAATCTGGAAATCT |

| 3'CaACT1term-SpeI | AGCTactagtTAGATTATGGTCGACATTTTATGATGGAAT |

| 5′NEUfwd-ApaI | ACTGgggcccGTAATTGTAGTAAGAATGACAAGTATCAG |

| 5'NEUrev-ANP-XhoI | ACTGctcgagttaattaaggcgccggcgcgccGGAAGGACGATGAAGGAGAGAAAG |

| 3′NEUfwd-SacII | ACTGccgcggTAAACAAGTGGTATTCAAGCACAATTC |

| 3'NEUT5L-SacIPacI | GCTGgagctcttaattaaTAACCCACTGAATTCTACATCGAAC |

| 3'ECE1prom-XhoI | TCATctcgagTTTAACGAATGGAAAATAGTTGGTAGTAAAATAAAGG |

| 5′ECE1prom500-AscI | TTCCggcgcgccGTCATTTGTAGGATTTTCAGCAGAACA |

| 5′ECE1prom1000-AscI | TTCCggcgcgccAGCGAAACATTTTTTTTTTTCAACGGCTC |

| 5′ECE1prom1500-AscI | TTCCggcgcgccACCCTAGTAATTATATGAAACATGCCCA |

| 5′ECE1prom2000-AscI | TTCCggcgcgccAACATTAACGACGCAAAATACAAACTTGGT |

| 5′ECE1prom2500-AscI | TTCCggcgcgccGTAAGCATTTTGGAGTAATACCATAGTTG |

| 5′ECE1prom3000-AscI | TTCCggcgcgccGCAAATAGAATTGTTCTATTGCTTAGCTTTAG |

| R1-CaACT1 | TCAGACCAGCTGATTTAGGTTTG |

| R2-CaACT1 | GTGAACAATGGATGGACCAG |

| R1-CaECE1 | ATCGAAAATGCCAAGAGAG |

| R2-CaECE1 | AGCATTTTCAATACCGACAG |

| R1-CaGFP | CTGAAGTCAAGTTTGAAGGTGATAC |

| R2-CaGFP | GCAGATTGTGTGGACAAGTAATG |

| GFP veri rev | TGATCTGGGTATCTCGCAAAGCAT |

Lowercase: restriction sites.

Construction of plasmids for TATA element mutations.

For the identification of the TATA element required for transcription of ECE1, we have used fusion PCRs to construct pECE1-GFP reporter cassettes carrying loss of function mutations in either TATA box 1 or 2. We have used the pSK-pECE11500-GFP plasmid as a template to amplify a promoter construct which is suitable for GFP expression.

For TATA box 1, which is located 109 bp upstream of the ECE1 start codon, we first amplified a 128-bp PCR product with primers pECE1 TATA1fwd and 3′ECE1prom-XhoI. Second, primers 5′ECE1prom1500-AscI and pECE1-TATA1 rev were used to amplify a 1,433-bp PCR product. Primers pECE1-TATA1fwd and pECE1-TATA1rev provide a 24-bp overlap which would introduce a loss of function mutation from TATAAA to CGCCCG of the TATA box 1. The overlap was used for the following fusion PCR to construct a 1,500-bp promoter construct without TATA box 1. Both primary PCR products were used as a template for fusion PCR with the primers 5′ECE1prom1500-AscI and 3′ECE1prom-XhoI to amplify a 1,536-bp product.

Mutation of TATA box 2 was performed in the same way. It is located 284 bp upstream of the ECE1 start codon and we first amplified a 302-bp PCR product with primers pECE1-TATA2fwd and 3′ECE1prom-XhoI. A second PCR product of 1258 bp was then amplified with the primers 5′ECE1prom1500-AscI and pECE1-TATA2 rev. Primers pECE1-TATA2fwd and pECE1-TATA2rev provide a 24-bp overlap which would introduce a mutation from TATAAT to CGAGGA at the site of TATA box 1. Both PCR products containing this overlap were then used as a template for fusion PCR with the primers 5′ECE1prom1500-AscI and 3′ECE1prom-XhoI.

The fusion PCR products containing either the TATA box 1 or the TATA box 2 mutations were finally restricted with AscI and XhoI and cloned into an AscI/XhoI digested pECE1500-GFP plasmid. The integration of the mutated TATA box was verified by Sanger sequencing (LGC Genomics, Berlin, Germany).

Construction of C. albicans strains.

The transformation cassettes were excised from the pECE1-GFP plasmids with ApaI/PacI. The fragments were then transformed into C. albicans SC5314 by using the established lithium acetate method (43). Integration of the transformation cassettes into the NEUT5L locus was verified by colony PCR. Oligonucleotide primers used for colony PCRs can be found in Table 3.

Gene expression analysis.

For the analysis of GFP expression, we have used selected C. albicans strains carrying GFP under the control of either the ADH1 promoter or different versions of the ECE1 promoter. They were first grown in SDG medium overnight at 37°C. From these precultures, 1 × 106 cells/mL were diluted into fresh SDG medium (prewarmed at 37°C) which contained 10% human serum if required. Cells were then grown for 1 or 2 h at 37°C. Afterwards, total RNA was isolated from the harvested cells as previously described (29). Quantitative RT PCR was performed using the Luna universal one-step RT-qPCR kit (New England Biolabs) on a QTower3 (Analytik Jena) with 100 ng/μL RNA. Gene expression of GFP under the control of the truncated ECE1 promoter constructs was normalized against GFP under the control of the ADH1 promoter. Calculation was done using the ΔΔCt method (44). Expression data from biological triplicates were compared with a two-tailed, unpaired Student's t test and only differences with a P value of ≤0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

RACE-PCR.

The size of the 5′ untranslated region of ECE1 mRNA was determined via 5′ RACE-PCR. For this, we have used the 5′ RACE-PCR kit (Life Technologies, Darmstadt) and gene-specific primers for ECE1 (Table 3). RACE-PCRs were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. 1 × 106 cells/mL of C. albicans SC5314 were grown in different yeast- or hyphae-inducing media for 1 h at 37°C. Afterwards total RNA was isolated as described above. A total of 2.5 μg of total RNA isolate were used for the initial cDNA synthesis. PCRs of the nested amplification rounds 1 and 2 were performed using the Q5 High Fidelity 2X master mix (New England Biolabs). Oligonucleotide primer GSP3 contains a XhoI restriction site for the subsequent cloning of the final PCR product into pSK plasmid, allowing Sanger sequencing of the PCR product and identification of the 5′ UTR sequence.

Fluorescence microscopy.

Fluorescence microscopy was performed with a Nikon Eclipse Ni microscope (Nikon, Germany). Differential interference contrast (DIC) illumination time was 200 ms and for the GFP channel it was 2,000 ms. The same illumination times were used for all samples to guarantee comparable GFP signals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) through the TRR 124 FungiNet “Pathogenic fungi and their human host: Networks of Interaction,” DFG project number 210879364, projects C3 (O.K.) and C2 (S.V.); and the German Ministry for Education and Science (BMBF 03Z2JN21 to O. K. and BMBF 03Z22JN11 to S. V.).

Conceptualization, O.K. and R.M.; Methodology, E.G. and N.T.; Formal Analysis, E.G., N.T., and R.M.; Investigation, E.G., N.T., S.H., and A.K.; Resources, S.V.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, E.G., N.T., and R.M.; Writing – Review & Editing, S.V., O.K., and R.M.; Funding Acquisition, S.V. and O.K.

Contributor Information

Ronny Martin, Email: ronny.martin@uni-wuerzburg.de.

Rebecca S. Shapiro, University of Guelph

REFERENCES

- 1.Moyes DL, Wilson D, Richardson JP, Mogavero S, Tang SX, Wernecke J, Höfs S, Gratacap RL, Robbins J, Runglall M, Murciano C, Blagojevic M, Thavaraj S, Förster TM, Hebecker B, Kasper L, Vizcay G, Iancu SI, Kichik N, Häder A, Kurzai O, Luo T, Krüger T, Kniemeyer O, Cota E, Bader O, Wheeler RT, Gutsmann T, Hube B, Naglik JR. 2016. Candidalysin is a fungal peptide toxin critical for mucosal infection. Nature 532:64–68. doi: 10.1038/nature17625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blagojevic M, Camilli G, Maxson M, Hube B, Moyes DL, Richardson JP, Naglik JR. 2021. Candidalysin triggers epithelial cellular stresses that induce necrotic death. Cell Microbiol 23:e13371. doi: 10.1111/cmi.13371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mogavero S, Sauer FM, Brunke S, Allert S, Schulz D, Wisgott S, Jablonowski N, Elshafee O, Krüger T, Kniemeyer O, Brakhage AA, Naglik JR, Dolk E, Hube B. 2021. Candidalysin delivery to the invasion pocket is critical for host epithelial damage induced by Candida albicans. Cell Microbiol 23:e13378. doi: 10.1111/cmi.13378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allert S, Forster TM, Svensson CM, Richardson JP, Pawlik T, Hebecker B, Rudolphi S, Juraschitz M, Schaller M, Blagojevic M, et al. 2018. Candida albicans-induced epithelial damage mediates translocation through intestinal barriers. mBio 9. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00915-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kasper L, König A, Koenig P-A, Gresnigt MS, Westman J, Drummond RA, Lionakis MS, Groß O, Ruland J, Naglik JR, Hube B. 2018. The fungal peptide toxin Candidalysin activates the NLRP3 inflammasome and causes cytolysis in mononuclear phagocytes. Nat Commun 9:4260. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06607-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogiers O, Frising UC, Kucharikova S, Jabra-Rizk MA, van Loo G, Van Dijck P, Wullaert A. 2019. Candidalysin Crucially Contributes to Nlrp3 Inflammasome Activation by Candida albicans Hyphae. mBio 10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02221-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drummond RA, Swamydas M, Oikonomou V, Zhai B, Dambuza IM, Schaefer BC, Bohrer AC, Mayer-Barber KD, Lira SA, Iwakura Y, Filler SG, Brown GD, Hube B, Naglik JR, Hohl TM, Lionakis MS. 2019. CARD9(+) microglia promote antifungal immunity via IL-1beta- and CXCL1-mediated neutrophil recruitment. Nat Immunol 20:559–570. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0377-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swidergall M, Khalaji M, Solis NV, Moyes DL, Drummond RA, Hube B, Lionakis MS, Murdoch C, Filler SG, Naglik JR. 2019. Candidalysin is required for neutrophil recruitment and virulence during systemic Candida albicans infection. J Infect Dis 220:1477–1488. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verma AH, Richardson JP, Zhou C, Coleman BM, Moyes DL, Ho J, Huppler AR, Ramani K, McGeachy MJ, Mufazalov IA, et al. 2017. Oral epithelial cells orchestrate innate type 17 responses to Candida albicans through the virulence factor candidalysin. Sci Immunol 2. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aam8834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richardson JP, Willems HME, Moyes DL, Shoaie S, Barker KS, Tan SL, Palmer GE, Hube B, Naglik JR, Peters BM. 2018. Candidalysin drives epithelial signaling, neutrophil recruitment, and immunopathology at the vaginal mucosa. Infect Immun 86. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00645-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ho J, Yang X, Nikou S-A, Kichik N, Donkin A, Ponde NO, Richardson JP, Gratacap RL, Archambault LS, Zwirner CP, Murciano C, Henley-Smith R, Thavaraj S, Tynan CJ, Gaffen SL, Hube B, Wheeler RT, Moyes DL, Naglik JR. 2019. Candidalysin activates innate epithelial immune responses via epidermal growth factor receptor. Nat Commun 10:2297. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09915-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swidergall M, Solis NV, Millet N, Huang MY, Lin J, Phan QT, Lazarus MD, Wang Z, Yeaman MR, Mitchell AP, Filler SG. 2021. Activation of EphA2-EGFR signaling in oral epithelial cells by Candida albicans virulence factors. PLoS Pathog 17:e1009221. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho J, Wickramasinghe DN, Nikou SA, Hube B, Richardson JP, Naglik JR. 2020. Candidalysin is a potent trigger of alarmin and antimicrobial peptide release in epithelial cells. Cells 9. doi: 10.3390/cells9030699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu Y, Zeng Z, Guo Y, Song L, Weatherhead JE, Huang X, Zeng Y, Bimler L, Chang C-Y, Knight JM, Valladolid C, Sun H, Cruz MA, Hube B, Naglik JR, Luong AU, Kheradmand F, Corry DB. 2021. Candida albicans elicits protective allergic responses via platelet mediated T helper 2 and T helper 17 cell polarization. Immunity 54:2595–2610.e2597. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu H, Duan Y, Lang S, Jiang L, Wang Y, Llorente C, Liu J, Mogavero S, Bosques-Padilla F, Abraldes JG, Vargas V, Tu XM, Yang L, Hou X, Hube B, Stärkel P, Schnabl B. 2020. The Candida albicans exotoxin candidalysin promotes alcohol-associated liver disease. J Hepatol 72:391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ost KS, O'Meara TR, Stephens WZ, Chiaro T, Zhou H, Penman J, Bell R, Catanzaro JR, Song D, Singh S, Call DH, Hwang-Wong E, Hanson KE, Valentine JF, Christensen KA, O'Connell RM, Cormack B, Ibrahim AS, Palm NW, Noble SM, Round JL. 2021. Adaptive immunity induces mutualism between commensal eukaryotes. Nature 596:114–118. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03722-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bacher P, Hohnstein T, Beerbaum E, Röcker M, Blango MG, Kaufmann S, Röhmel J, Eschenhagen P, Grehn C, Seidel K, Rickerts V, Lozza L, Stervbo U, Nienen M, Babel N, Milleck J, Assenmacher M, Cornely OA, Ziegler M, Wisplinghoff H, Heine G, Worm M, Siegmund B, Maul J, Creutz P, Tabeling C, Ruwwe-Glösenkamp C, Sander LE, Knosalla C, Brunke S, Hube B, Kniemeyer O, Brakhage AA, Schwarz C, Scheffold A. 2019. Human anti-fungal Th17 immunity and pathology rely on cross-reactivity against Candida albicans. Cell 176:1340–1355.e1315. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li XV, Leonardi I, Putzel GG, Semon A, Fiers WD, Kusakabe T, Lin W-Y, Gao IH, Doron I, Gutierrez-Guerrero A, DeCelie MB, Carriche GM, Mesko M, Yang C, Naglik JR, Hube B, Scherl EJ, Iliev ID. 2022. Immune regulation by fungal strain diversity in inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 603:672–678. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04502-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Austermeier S, Pekmezović M, Porschitz P, Lee S, Kichik N, Moyes DL, Ho J, Kotowicz NK, Naglik JR, Hube B, Gresnigt MS. 2021. Albumin neutralizes hydrophobic toxins and modulates Candida albicans pathogenicity. mBio 12:e0053121. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00531-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richardson JP, Brown R, Kichik N, Lee S, Priest E, Mogavero S, Maufrais C, Wickramasinghe DN, Tsavou A, Kotowicz NK, et al. 2022. Candidalysins are a new family of cytolytic fungal peptide toxins. mBio e0351021. doi: 10.1128/mbio.03510-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bader O, Krauke Y, Hube B. 2008. Processing of predicted substrates of fungal Kex2 proteinases from Candida albicans, C. glabrata, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Pichia pastoris. BMC Microbiol 8:116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richardson JP, Mogavero S, Moyes DL, Blagojevic M, Kruger T, Verma AH, Coleman BM, De La Cruz Diaz J, Schulz D, Ponde NO, et al. 2018. Processing of Candida albicans Ece1p is critical for candidalysin maturation and fungal virulence. mBio 9. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02178-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin R, Albrecht-Eckardt D, Brunke S, Hube B, Hunniger K, Kurzai O. 2013. A core filamentation response network in Candida albicans is restricted to eight genes. PLoS One 8:e58613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murad AM, Leng P, Straffon M, Wishart J, Macaskill S, MacCallum D, Schnell N, Talibi D, Marechal D, Tekaia F, d'Enfert C, Gaillardin C, Odds FC, Brown AJ. 2001. NRG1 represses yeast-hypha morphogenesis and hypha-specific gene expression in Candida albicans. EMBO J 20:4742–4752. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braun BR, Kadosh D, Johnson AD. 2001. NRG1, a repressor of filamentous growth in C.albicans, is down-regulated during filament induction. EMBO J 20:4753–4761. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doedt T, Krishnamurthy S, Bockmuhl DP, Tebarth B, Stempel C, Russell CL, Brown AJ, Ernst JF. 2004. APSES proteins regulate morphogenesis and metabolism in Candida albicans. Mol Biol Cell 15:3167–3180. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e03-11-0782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kadosh D, Johnson AD. 2005. Induction of the Candida albicans filamentous growth program by relief of transcriptional repression: a genome-wide analysis. Mol Biol Cell 16:2903–2912. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e05-01-0073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carlisle PL, Banerjee M, Lazzell A, Monteagudo C, Lopez-Ribot JL, Kadosh D. 2009. Expression levels of a filament-specific transcriptional regulator are sufficient to determine Candida albicans morphology and virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:599–604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804061106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin R, Moran GP, Jacobsen ID, Heyken A, Domey J, Sullivan DJ, Kurzai O, Hube B. 2011. The Candida albicans-specific gene EED1 encodes a key regulator of hyphal extension. PLoS One 6:e18394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruben S, Garbe E, Mogavero S, Albrecht-Eckardt D, Hellwig D, Hader A, Kruger T, Gerth K, Jacobsen ID, Elshafee O, et al. 2020. Ahr1 and Tup1 contribute to the transcriptional control of virulence-associated genes in Candida albicans. mBio 11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00206-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bruno VM, Wang Z, Marjani SL, Euskirchen GM, Martin J, Sherlock G, Snyder M. 2010. Comprehensive annotation of the transcriptome of the human fungal pathogen Candida albicans using RNA-seq. Genome Res 20:1451–1458. doi: 10.1101/gr.109553.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sellam A, Hogues H, Askew C, Tebbji F, van Het Hoog M, Lavoie H, Kumamoto CA, Whiteway M, Nantel A. 2010. Experimental annotation of the human pathogen Candida albicans coding and noncoding transcribed regions using high-resolution tiling arrays. Genome Biol 11:R71. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-7-r71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Argimón S, Wishart JA, Leng R, Macaskill S, Mavor A, Alexandris T, Nicholls S, Knight AW, Enjalbert B, Walmsley R, Odds FC, Gow NAR, Brown AJP. 2007. Developmental regulation of an adhesin gene during cellular morphogenesis in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell 6:682–692. doi: 10.1128/EC.00340-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Childers DS, Mundodi V, Banerjee M, Kadosh D. 2014. A 5' UTR-mediated translational efficiency mechanism inhibits the Candida albicans morphological transition. Mol Microbiol 92:570–585. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skrzypek MS, Binkley J, Binkley G, Miyasato SR, Simison M, Sherlock G. 2017. The Candida Genome Database (CGD): incorporation of Assembly 22, systematic identifiers and visualization of high throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 45:D592–D596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gillum AM, Tsay EY, Kirsch DR. 1984. Isolation of the Candida albicans gene for orotidine-5'-phosphate decarboxylase by complementation of S. cerevisiae ura3 and E. coli pyrF mutations. Mol Gen Genet 198:179–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00328721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grumaz C, Lorenz S, Stevens P, Lindemann E, Schock U, Retey J, Rupp S, Sohn K. 2013. Species and condition specific adaptation of the transcriptional landscapes in Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis. BMC Genomics 14:212. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Struhl K. 1989. Molecular mechanisms of transcriptional regulation in yeast. Annu Rev Biochem 58:1051–1077. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.005155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zordan RE, Miller MG, Galgoczy DJ, Tuch BB, Johnson AD. 2007. Interlocking transcriptional feedback loops control white-opaque switching in Candida albicans. PLoS Biol 5:e256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim S, Wolyniak MJ, Staab JF, Sundstrom P. 2007. A 368-base-pair cis-acting HWP1 promoter region, HCR, of Candida albicans confers hypha-specific gene regulation and binds architectural transcription factors Nhp6 and Gcf1p. Eukaryot Cell 6:693–709. doi: 10.1128/EC.00341-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim S, Nguyen QB, Wolyniak MJ, Frechette G, Lehman CR, Fox BK, Sundstrom P. 2018. Release of transcriptional repression through the HCR promoter region confers uniform expression of HWP1 on surfaces of Candida albicans germ tubes. PLoS One 13:e0192260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hünniger K, Lehnert T, Bieber K, Martin R, Figge MT, Kurzai O. 2014. A virtual infection model quantifies innate effector mechanisms and Candida albicans immune escape in human blood. PLoS Comput Biol 10:e1003479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walther A, Wendland J. 2003. An improved transformation protocol for the human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Curr Genet 42:339–343. doi: 10.1007/s00294-002-0349-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pfaffl MW. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]