Abstract

Background: Previous research has shown an association between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and secondary mental health problems in youth with prenatal substance exposure (PSE), but the association between ACEs and neurodevelopmental disorders is less clear. Methods: This longitudinal register-based cohort study investigated relationships between health at birth, ACEs (out-of-home care (OHC) and maternal adversities), and neurodevelopmental disorders among youth with PSE (alcohol/drugs, n = 615) and matched unexposed controls (n = 1787). Hospital medical records and register data were merged and analysed using Cox regression models. Results: Conduct and emotional disorders (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems ICD-10, F90–F94) were more common among the exposed than the controls but only when the exposed and controls with no OHC were compared. The difference appeared in hyperkinetic disorders (ADHD, F90), mixed disorders of conduct and emotions (F92) and emotional disorders with onset specific to childhood (F93). Among the exposed and controls with OHC, over 40% had received an F90–F94 diagnosis. Regarding specific developmental disorders (F80–F83, e.g., impairments in speech and language and scholastic skills) the moderate difference between the exposed and controls attenuated after adjustment for OHC. Again, the rates were highest among the exposed with OHC and the controls with OHC. OHC and maternal risks were interrelated and, together with male sex and low birth weight, were associated with neurodevelopmental disorders both among the exposed and controls and decreased the difference between them. Conclusions: A strong association between ACEs and neurodevelopmental disorders was found. Brain research is needed to examine whether ACEs worsen neurodevelopmental outcomes caused by PSE.

Keywords: adverse childhood experiences, FASD, neurodevelopmental disorders, prenatal substance exposure, youth

The developing brain is highly sensitive and responsive to environmental exposures during the prenatal and early postnatal periods (Miguel et al., 2019). Maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy is a major prenatal environmental risk and can impair the normal development of the foetus resulting in a cluster of behavioural, neurocognitive and physical abnormalities diagnosed as Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) (Popova et al., 2016; Riley et al., 2011). The use of illicit drugs may have similar neurodevelopmental consequences (Ross et al., 2015) but research is inconsistent (Irner, 2012; Lambert & Bauer, 2012).

Maturation of the brain continues throughout childhood and adolescence, and environmental factors play a crucial role in the maturation of the brain regions responsible for higher cognitive functioning (Johnson et al., 2016; Miguel et al., 2019; Noble et al., 2012). Severe stress caused by recurrent traumatic experiences, especially in early life during the rapid development of the brain, can cause enduring brain dysfunction (Anda et al., 2006; Fox et al., 2010; Noble et al., 2012). Limbic regions, such as the amygdala and hippocampus, are particularly affected (Miguel et al., 2019; Tottenham et al., 2010) as well as the anterior cingulate cortex (Noble et al., 2012). The amygdala has a central role in social-emotional processing, the hippocampus in memory functions and the anterior cingulate cortex in cognitive control and self-regulation (Noble et al., 2012). Poor caregiving and institutional rearing, even in the best circumstances, may have long-term effects on the neurobiological development associated with socioemotional behaviours (De Bellis & Zisk, 2014; Miguel et al., 2019; Tottenham et al., 2010).

Because of possible teratogenic central nervous system (CNS) effects of alcohol and drugs, affected children are prone to additional mental and behavioural disorders (Irner, 2012; Streissguth et al., 1996). Studies on prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) have shown an association between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and disabilities referred to as secondary, such as mental health problems, disrupted school experience and alcohol/drug problems (Easey et al., 2019; Popova et al., 2016; Streissguth et al., 1996, 2004). However, based on brain research (Miguel et al., 2019; Tottenham et al., 2010), it is possible to assume that ACEs may also increase neurodevelopmental disorders, manifesting especially in cognitive control, self-regulation and memory functions. According to a review by Alberry et al. (2021), a stressful environment in early life may worsen the neurodevelopmental outcomes of prenatal alcohol exposure through epigenetic changes.

The relationship between PAE, ACEs and neurodevelopmental disorders has not been well studied (Alberry et al., 2021; Koponen et al., 2009; Kambeitz et al., 2019; Price et al., 2017). The few existing studies suggest that ACEs may increase the likelihood of neurodevelopmental problems appearing in attention, memory, intelligence, language development and behaviour (Koponen, 2006; Koponen et al., 2009, 2013; Coggins et al., 2007; Henry et al., 2007; Hyter, 2012; Kambeitz et al., 2019). Studies on prenatal drug exposure have focused more systematically on environmental risk factors. These studies conclude that environmental factors largely moderate or even overshadow the effects of prenatal drug exposure on children's and adolescents’ cognitive and emotional development (Ackerman et al., 2010; Buckingham-Howes et al., 2013; Irner, 2012; Lambert & Bauer, 2012; Minnes et al., 2011; Schempf, 2007).

This longitudinal register-based cohort study investigated associations between prenatal substance exposure (PSE, alcohol/drugs), ACEs and diagnosed neurodevelopmental disorders. First, the prevalence of specific developmental disorders (F80–F83) and conduct and emotional disorders (F90–F94) was compared between youth with PSE (n = 615) aged 15–24 years and matched unexposed controls (n = 1787). Second, the relationships between PSE, health at birth (birth weight, exposure to smoking), ACEs (out-of-home care (OHC) and maternal adversities), and F80–F83 and F90–F94 diagnoses were investigated. The classification of diseases is based on the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10, version 2016). The studied disease categories include disorders in speech and language, scholastic skills, motor function, ADHD, and conduct and emotional disorders, which have been strongly associated with PAE in particular (Mattson et al., 2019).

Our hypothesis was that diagnosed neurodevelopmental disorders are more common among the exposed than the controls, and that ACEs are associated with an increased risk of these disorders in both groups. ACEs are associated particularly with diagnoses that reflect difficulties in cognitive control and self-regulation of emotion and behaviour.

Methods

Data collection

Exposed youths were born in 1992–2001 to mothers with a significant substance abuse problem (alcohol and/or drugs) identified by public health maternity clinic nurses in the Helsinki metropolitan area and referred to three special tertiary care antenatal clinics at Helsinki University Hospital (HUS) for antenatal follow-up and counselling. Identification was based on the test score (≥ 8) on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), detected drug abuse or nonmedical use of a central nervous system medication or opioid treatment and evaluation of the mother's life situation. The pregnancy follow-up at antenatal clinics included visits scheduled every 2–4 weeks according to individual need, with intensified support by the experienced multidisciplinary addiction treatment team and easy access to addiction treatment and/or psychiatric care services (Kahila et al., 2010; Sarkola et al., 2007). At each visit, substance use (i.e., alcohol, cannabis, amphetamine, heroin, buprenorphine, and other drugs) was monitored with voluntary urine toxicology screenings, conventional blood tests reflecting alcohol consumption, i.e., carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT), haemoglobin-acetaldehyde adducts, mean cell volume (MCV), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), and self-reports (Sarkola et al., 2000). A majority of children were exposed to alcohol or alcohol and drugs.

Matched unexposed controls were collected from the Medical Birth Register among women with no evidence of maternal substance abuse in any of the national health and social welfare registers at the time of the offspring's birth. The matching criteria were as follows: same maternal age, parity and number of foetuses and same month of birth and delivery hospital of the child. Mothers’ mean age at the time of the child's birth was 27 years (SD 6.5, range 15–45 years). Matching was done for maternal characteristics and therefore children were not matched by sex. The proportion of boys in the cohort corresponds with the proportion of new-borns in Finland (51.1%, Statistics Finland, 2019).

The present study is the second follow-up of the cohort (Sarkola et al., 2007). For the first follow-up, from birth up to the age of 5–15 years, hospital medical records of substance-abusing mothers and their children were reviewed and linked with register data from multiple mandatory national health and social welfare registers. Similar register data from the national registers were gathered for each mother–child control dyad. In the present second follow-up, the data collected for the first follow-up were used and new data up to the age of 15–24 years were collected.

The unique identification number assigned to each Finnish citizen at birth or immigration was used to link the data, and after linkage the identification numbers were concealed and replaced with study numbers. The first follow-up of the cohort included 638 exposed and 1914 unexposed mother–child dyads. The present second follow-up included 615 exposed and 1787 unexposed mother–child dyads after exclusions (missing/nondisclosed ID information, died in infancy, incorrect birth year). The data collection process and registers are described in detail in Koponen et al. (2020b).

Ethics

The study was approved by the local ethical committee of HUS (Dnro 333/E8/02) and all register organisations which provided data. No study subjects were contacted. All register linkages were performed by a statistical authority (Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, THL) and the data were analysed anonymously by researchers with research permission provided by the register keepers. According to Finnish law, informed consent is not required in register studies when study subjects are not contacted.

Variables and register sources

The variables used in the present study are listed below. These include variables on childhood adversities considered important for children's neurocognitive and emotional development (Miguel et al., 2019; Shonkoff et al., 2009).

Outcome variables.

Primary diagnosis for a neurodevelopmental disorder: Specific developmental disorders (ICD-10 F80–F83 and conduct and emotional disorders F90–F94)

At least one inpatient episode (public and private hospitals, 1992–2016) or outpatient hospital visit (public hospitals, 1998–2016) with International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems ICD-10 codes F80–F83 and F90–F94 (1996–2016) and the corresponding ICD-9 codes (1992–1995) based on the Hospital Discharge Register (1992–1993) and Care Register for Health Care (1994–2016).

Youths’ demographic background factors

Sex (male, female): Medical Birth Register.

Mortality (no, yes; date of death): Cause of Death Register.

Native language (Finnish, Swedish, other): Population Information System.

Marital status (married, unmarried: single/divorced/widowed): Population Information System.

Completed secondary education (no, yes): Education Register.

Prenatal substance exposure (alcohol/drugs)

FASD (no, yes): FAS, FAE (Foetal Alcohol Effects), ARND (Alcohol Related Neurobehavioral Disorder), ARBD (Alcohol Related Birth Defect): Register of Congenital Malformations. At least one inpatient episode or outpatient hospital visit with ICD-9 code 760.71 or ICD-10 code Q86.0. FAS (Foetal Alcohol Syndrome): Hospital Discharge Register or Care Register for Health Care.

Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) (no, yes): Medical records from the HAL clinics, Medical Birth Register, and Hospital Discharge Register or Care Register for Health Care including inpatient episodes and outpatient hospital visits with ICD-9 code 7795 or ICD-10 code P96.1.

Maternal smoking during pregnancy

Exposure to mother's daily smoking (no exposure or mother stopped smoking after the first trimester, mother smoked throughout pregnancy): Medical Birth Register.

New-born health

Gestational weeks at delivery (< 37 weeks, ≥ 37 weeks): Medical Birth Register.

Apgar score at one minute (0–6, 7–10): Medical Birth Register.

Birth weight (< 2500 g, ≥ 2500 g; median): Medical Birth Register.

Birth height (median): Medical Birth Register.

Adverse childhood experiences:

Out-of-home care (no OHC, at least one episode; age at first episode). Information on OHC during 1992–2016 is based on the Child Welfare Register. In the Finnish child welfare system, outpatient support is always offered first and OHC is only indicated if outpatient support has failed (Child Welfare Act, 2007). OHC ends at the age of 18 years, but extended aftercare services were available for OHC youth until the age of 24 years at the time of the study.

Mother's life situation at delivery

Age: Medical Birth Register (< 25 years, ≥ 25 years).

Marital status (married, unmarried: single/divorced/widowed): Medical Birth Register.

Socioeconomic status (high (self-employed/lower-level employee/upper-level employee), low (manual worker/student/pensioner/other)): Medical Birth Register.

Maternal risk factors

Diagnosed mental or behavioural disorder: At least one outpatient visit or inpatient episode with a primary diagnosis for mental or behavioural disorder: ICD-9 codes (1987–1995) 290 and 293–319, and ICD-10 codes (1996–2016) F00–F09 and F20–F99 based on the Hospital Discharge Register or the Care Register for Health Care.

Diagnosed substance abuse: At least one outpatient visit or inpatient episode with a primary or a secondary diagnosis or external cause for alcohol and/or drug-related abuse: ICD-9 (1987–1995) codes: 291–292, 303–305, 3570, 4255, 5353, 5710, 5711–5713, 6483, 6555, 9650, and 9696–9697 and ICD-10 (1996–2016) codes E24.4, F10–F16, F18–F19, G31.2, G40.5, G40.51, G40.52, G62.1, G72.1, I42.6, K29.2, K70, K85.2, K86, O35.4–O35.5, P04.4, R78.0–R78.5, T40, T43.6, T50.2–T50.3, T51, Z71.4, Z72.1–Z72.2, X45, and X69 based on the Hospital Discharge Register or the Care Register for Health Care.

Mortality (no, yes; date of death): Cause of Death Register.

Criminal record (no sentence, at least one sentence during 1985–2018): Criminal Records Register.

Social assistance (no long-term social assistance, long-term social assistance (10–12 months during a one-year period in 2002–2016)): Register of Social Assistance. Social assistance is the last-resort financial assistance for individuals and families in order to guarantee a minimum standard of living.

Statistical analysis

Data from hospital medical records and nine registers were merged for this longitudinal register-based matched cohort study. Data analysis was guided by the fact that a majority (64%) of the exposed youth had been in OHC compared with a minority (8%) of the unexposed control group. Previous studies have shown a strong association between OHC, especially institutional care, and mental health problems (e.g., van IJzendoorn et al., 2020). Therefore, in the first step of the analysis, the prevalence of specific developmental disorders (F80–F83) and conduct and emotional disorders (F90–F94) was analysed separately according to exposure status and OHC status by using Pearson chi2 tests and Fisher's exact test.

In the next step of the analysis, bivariate associations between OHC, other childhood adversities and specific developmental disorders and conduct and emotional disorders were analysed separately among the exposed and controls in order to see whether predictors of these disorders are similar in both groups. In the final hierarchical multivariable models, the exposure status and all childhood adversities were added step by step. Cox regression modelling was used in univariate and multivariable analyses with the longitudinal data. The follow-up started from birth and lasted until the first F80–F83 diagnosis or the first F90–F94 diagnosis, death or the end of the follow-up in 2016. The time of the first incidence of maternal risk factors (e.g., child's age at the mother's first mental or behavioural disorder diagnosis) was taken into account in the analyses. The cut-off points were before birth and/or before school age (< 7 years), as appropriate. Crude and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Variables to the multivariable Cox regression models were chosen on a theoretical and statistical basis. Spearman correlations between study variables were explored prior to multivariable analyses to check multicollinearity. Due to moderate or strong correlations between exposure status and maternal risk factors (0.244–0.675, p < 0.001), a sum score of five maternal risk factors (mental or behavioural disorder, diagnosed substance abuse problem, death, long-term social assistance, criminal record) was created to address the multicollinearity. Child and maternal age were not included in the multivariable Cox regression models as the groups were matched by these factors. IBM SPSS statistics (version 28.0) was used.

Results

Sample description

About half of the 615 exposed (49.3%) and 1787 controls (51.7%) were male, 59.5% were 18–24 years old in 2016 (range 15–24 years), a majority had Finnish as their native language (exposed 95.9%, controls 86.2%), and 17.9% of the exposed and 23.4% of the controls had completed secondary education. In both groups, 1% had died during the follow-up, and less than 2% were married. Of the exposed, 7.5% (n = 46) had a FASD continuum diagnosis and 8.1% (n = 50) had a history of NAS diagnosis. Compared with the unexposed controls, the exposed were more often exposed to daily maternal smoking throughout pregnancy (75.3%/18.9%, p < 0.001) and were more likely to have had a birth weight less than 2500 g (12.5%/6.7%, p < 0.001) and birth height below the median (60.0%/39.4%, p < 0.001). No differences between the exposed and controls were found in gestational age at delivery or 1-min Apgar scores. Of the exposed, 63.9% had been in OHC at least once (controls 8.2%, p < 0.001) and 91.9% had at least one maternal risk factor (controls 27.8%, p < 0.001), (Koponen et al., 2020a). The median age of the first diagnosis of specific developmental disorders (F80–F83) was 6.4 years (interquartile range IQR 5.3–9.6) among the exposed and 6.4 years (IQR 5.2–9.8) among the controls. The median age of diagnosis of conduct and emotional problems (F90–F94) was 10.2 years (IQR 7.8–12.8) among the exposed and 10.7 years (IQR 8.2–13.9) among the controls.

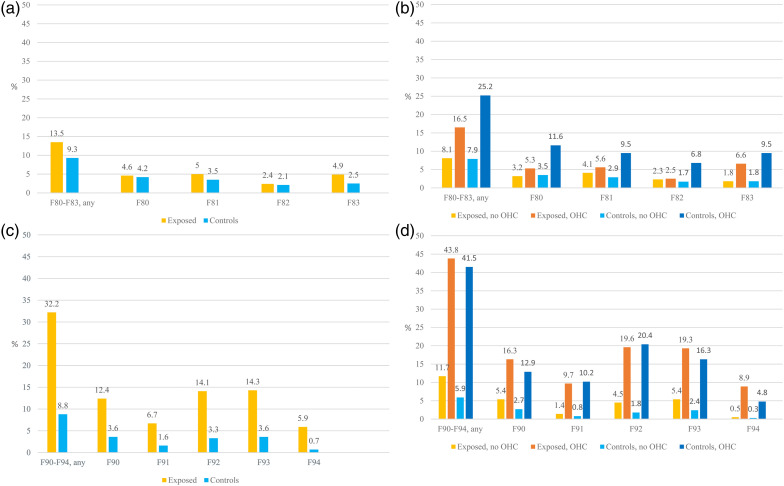

Neurodevelopmental disorders among youth with prenatal substance exposure and unexposed controls, and separately stratified for OHC

Figure 1(a) to (d) and Table 1 show that the overall proportion of specific developmental disorders (F80–F83) was somewhat higher, and the proportion of conduct and emotional disorders (F90–F94) almost four times higher among the exposed than the controls. However, when the results were analysed by the combined effects of PSE and OHC, the picture was more complicated. The first point noticed was that the rates of neurodevelopmental disorders were much higher among youth with OHC regardless of their substance exposure status. Second, the differences between the exposed and controls were seen mostly between the exposed without OHC and the controls without OHC.

Figure 1.

(a) Specific developmental disorders (F80–F83) among the exposed and controls (%). (b) Specific developmental disorders (F80–F83) among the exposed and controls with and without out-of-home care (OHC) (%). F80–F83 Specific developmental disorders, F80 Specific developmental disorders of speech and language, F81 Specific developmental disorders of scholastic skills, F82 Specific developmental disorder of motor function, F83 Mixed specific developmental disorders. (c) Conduct and emotional disorders (F90–F94) among the exposed and controls (%). (d) Conduct and emotional disorders (F90–F94) among the exposed and controls with and without OHC (%). F90–F94 Conduct and emotional disorders, F90 Hyperkinetic disorders (ADHD), F91 Conduct disorders, F92 Mixed disorders of conduct and emotions, F93 Emotional disorders with onset specific to childhood, and F94 Disorders of social functioning with onset specific to childhood and adolescence.

Table 1.

Diagnosed neurodevelopmental disorders among the exposed and controls and separately in different out-of-home care (OHC) groups, %.

| Exposed, all n = 615 % (n) |

Controls, all n = 1787 % (n) |

p-value between all exposed and controls |

Exposed, no OHC n = 222 % (n) |

Controls, no OHC n = 1640 % (n) |

p-value between exposed and controls with no OHC | Exposed, OHC n = 393 % (n) |

Controls, OHC n = 147 % (n) |

p-value between exposed and controls with at least one OHC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

F80–F83 Specific developmental

disorders Yes |

13.5 (83) |

9.3 (166) |

0.003 |

8.1 (18) |

7.9 (129) |

0.900 |

16.5 (65) |

25.2 (37) |

0.023 |

| F80 Specific developmental disorders of speech and

language Yes |

4.6 (28) |

4.2 (75) |

0.707 |

3.2 (7) |

3.5 (58) |

0.770 |

5.3 (21) |

11.6 (17) |

0.012 |

| F81 Specific developmental disorders of scholastic

skills Yes |

5.0 (31) |

3.5 (62) |

0.082 |

4.1 (9) |

2.9 (48) |

0.360 |

5.6 (22) |

9.5 (14) |

0.104 |

| F82 Specific developmental disorder of motor

function Yes |

2.4 (15) |

2.1 (38) |

0.649 |

2.3 (5) |

1.7 (28) |

0.564 |

2.5 (10) |

6.8 (10) |

0.020 |

| F83 Mixed specific developmental disorders Yes |

4.9 (30) |

2.5 (44) |

0.003 |

1.8 (4) |

1.8 (30) |

0.618 |

6.6 (26) |

9.5 (14) |

0.251 |

| F90–F94 Conduct and emotional disorders |

32.2 (198) |

8.8 (158) |

< 0.001

|

11.7 (26) |

5.9 (97) |

0.001 |

43.8 (172) |

41.5 (61) |

0.636 |

| F90 Hyperkinetic disorders (ADHD) Yes |

12.4 (76) |

3.6 (64) |

< 0.001 |

5.4 (12) |

2.7 (45) |

0.031 |

16.3 (64) |

12.9 (19) |

0.335 |

| F91 Conduct disorders Yes |

6.7 (41) |

1.6 (28) |

< 0.001 |

1.4 (3) |

0.8 (13) |

0.296 |

9.7 (38) |

10.2 (15) |

0.852 |

| F92 Mixed disorders of conduct and emotions Yes |

14.1 (87) |

3.3 (59) |

< 0.001 |

4.5 (10) |

1.8 (29) |

0.008 |

19.6 (77) |

20.4 (30) |

0.832 |

| F93 Emotional disorders with onset specific to

childhood Yes |

14.3 (88) |

3.6 (64) |

< 0.001 |

5.4 (12) |

2.4 (40) |

0.012 |

19.3 (76) |

16.3 (24) |

0.423 |

| F94 Disorders of social functioning with onset specific to

childhood and adolescence Yes |

5.9 (36) |

0.7 (12) |

< 0.001 |

0.5 (1) |

0.3 (5) |

0.534 |

8.9 (35) |

4.8 (7) |

0.110 |

Note. Bold values denote statistical significance.

Comparison between youth with and without OHC separately in the exposed and control groups.

Specific developmental disorders (F80–F83) were twice as common among the exposed with OHC (16.5%) compared with the exposed with no OHC (8.1%, p = 0.003). Regarding the subcategories, a significant difference was seen in mixed specific developmental disorders (F83, p = 0.008) but not in the proportion of speech and language (F80), scholastic skills (F81) or motor function (F82) disorders. Similarly, F80–F83 diagnoses were more common among the controls with OHC (25.2%) than the controls with no OHC (7.9%, p < 0.001), and the differences were clear in all subcategories (p < 0.001) (Table 1, Figure 1(a) and (b)).

Conduct and emotional disorders (F90–F94) were almost four times more common among the exposed with OHC (43.8%) than the exposed with no OHC (11.7%, p < 0.001). The clear difference (p < 0.001) was seen in all subcategories: hyperkinetic disorders (ADHD, F90), conduct disorders (F91), mixed disorders of conduct and emotions (F92), emotional disorders with onset specific to childhood (F93) and disorders of social functioning (F94). Among the controls, F90–F94 diagnoses were seven times more common among those for OHC (41.5%) than those with no OHC (5.9%, p < 0.001), and the differences in all subcategories were significant (p < 0.001) (Table 1, Figure 1(c) and (d)).

Comparison between exposed and controls stratified for OHC.

Regarding the main and subcategories of specific developmental disorders (F80–F83), no significant differences were found between the exposed without OHC (8.1%) and the controls without OHC (7.9%). Among the youth with OHC, F80–F83 diagnoses were more common among the controls (25.2%) than the exposed (16.5%, p = 0.023) mainly due to the higher proportion of disorders of speech and language (F80) and motor function (F82) (Table 1, Figure 1(a) and (b)).

Conduct and emotional disorders (F90–F94) were two times more common among the exposed without OHC (11.7%) compared with the controls without OHC (5.9%, p = 0.001) mainly due to the higher proportion of hyperkinetic disorders (ADHD, F90), mixed disorders of conduct and emotions (F92) and emotional disorders with onset specific to childhood (F93). No differences were found between the exposed with OHC and controls with OHC. In both groups, over 40% had an F90–F94 diagnosis (Table 1, Figure 1(c) and (d)).

Bivariate associations between childhood adversities and neurodevelopmental disorders

Specific developmental disorders (F80–F83).

Among the exposed, F80–F83 diagnoses were associated with low birth weight, OHC, maternal long-term social assistance and a sum of maternal risk factors. In addition, F80–F83 diagnoses were more common among the exposed with a diagnosed FASD than those who were undiagnosed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate associations between childhood adversity, disorders of psychological development (F80–F83) and behavioural and emotional disorders with onset in childhood and adolescence (F90–F94) among the exposed and unexposed controls. Follow-up from birth to early adulthood, Cox regression hazard model, N = 2402.

| F80–F83 | F90–F94 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposed, n =

615 HR (95% CI) |

p-value | Controls, n =

1787 HR (95% CI) |

p-value | Exposed, n =

615 HR (95% CI) |

p-value | Controls, n =

1787 HR (95% CI) |

p-value | |

| Sex and health in infancy | ||||||||

| FASD No Yes |

1 2.64 (1.49–4.70) |

0.001 |

1 1.60 (1.02–2.52) |

0.042 | ||||

| Sex Female Male |

1 1.52 (0.98–2.36) |

0.059 |

1 2.75 (1.95–3.89) |

< 0.001 |

1 1.65 (1.24–2.19) |

< 0.001 |

1 1.74 (1.26–2.41) |

< 0.001 |

| Birth weight ≥ 2500 g < 2500 g |

1 2.98 (1.85–4.83) |

< 0.001 |

1 2.32 (1.47–3.66) |

0.001 |

1 1.53 (1.05–2.24) |

0.027 |

1 1.01 (0.53–1.92) |

0.972 |

| Mother smoked throughout

pregnancy No Yes |

1 0.96 (0.59–1.58) |

0.875 |

1 0.93 (0.63–1.38) |

0.709 |

1 0.94 (0.68–1.30) |

0.710 |

1 1.99 (1.42–2.79) |

< 0.001 |

| Mother's sociodemographic characteristics at delivery | ||||||||

| Mother's age ≥ 25 years < 25 years |

1 0.76 (0.48–1.20) |

0.234 |

1 1.27 (0.94–1.73) |

0.124 |

1 1.25 (0.94–1.66) |

0.126 |

1 2.29 (1.67–3.13) |

< 0.001 |

| Mother's marital status Married Not married |

1 0.79 (0.48–1.31) |

0.368 |

1 1.17 (0.86–1.60) |

0.309 |

1 1.45 (0.99–2.12) |

0.060 |

1 1.89 (1.37–2.59) |

< 0.001 |

| Socioeconomic status Higher Lower |

1 0.76 (0.48–1.22) |

0.257 |

1.44 (1.06–1.97) |

0.022 |

1 1.22 (0.88–1.68) |

0.229 |

1 2.01 (1.44–2.80) |

< 0.001 |

| Maternal risk factors | ||||||||

| Mother's mental or behavioural disorder (excl. substance

abuse) No Yes |

1 1.14 (0.74–1.76) |

0.541 |

1 1.88 (1.34–2.63) |

< 0.001 |

1 1.09 (0.83–1.44) |

0.543 |

1 2.59 (1.87–3.59) |

< 0.001 |

| Mother's first mental or behavioural disorder No diagnosis Before birth After birth |

1 1.25 (0.74–2.11) 1.06 (0.63–1.78) |

0.411 0.823 |

1 2.19 (1.02–4.69) 1.83 (1.28–2.62) |

0.044 < 0.001 |

1 0.93 (0.64–1.34) 1.23 (0.89–1.69) |

0.687 0.204 |

1 3.85 (2.01–7.37) 2.42 (1.70–3.43) |

< 0.001 <0.001 |

| Child's age at mother's first mental or behavioural

disorder No diagnosis < 7 years ≥ 7 years |

1 1.02 (0.64–1.64) 1.55 (0.84–2.87) |

0.928 0.158 |

1 2.19 (1.44–3.35) 1.59 (1.00–2.53) |

< 0.001 0.050 |

1 1.04 (0.77–1.41) 1.25 (0.82–1.91) |

0.791 0.298 |

1 2.92 (1.94–4.41) 2.30 (1.50–3.54) |

< 0.001 < 0.001 |

| Mother's substance abuse problem (all substance abuse

related diagnoses) No Yes |

1 1.67 (0.99–2.81) |

0.055 |

1 2.31 (1.42–3.77) |

0.001 |

1 1.48 (1.07–2.04) |

0.018 |

1 3.54 (2.29–5.47) |

< 0.001 |

| Child's age at mother's first substance abuse problem

(as a primary diagnosis) No diagnosis < 7 years ≥ 7 years |

1 1.51 (0.94–2.42) 1.99 (1.04–3.82) |

0.091 0.038 |

1 1.88 (0.70–5.06) 2.96 (1.51–5.79) |

0.214 0.002 |

1 1.21 (0.90–1.62) 1.35 (0.87–2.12) |

0.220 0.185 |

1 4.32 (2.12–8.80) 2.38 (1.11–5.08) |

< 0.001 0.025 |

| Mother's criminal record No Yes |

1 1.56 (0.86–2.82) |

0.141 |

1 1.42 (0.35–5.74) |

0.620 |

1 1.23 (0.81–1.87) |

0.341 |

1 3.60 (1.33–9.70) |

0.012 |

| Child's age at mother's first criminal record No criminal record Before birth After birth |

1 1.40 (0.70–2.81) 2.09 (0.76–5.73) |

0.340 0.151 |

1 0.74 (0.10–5.29) 17.85 (2.49–128.06) |

0.765 0.004 |

1 0.89 (0.53–1.52) 2.77 (1.46–5.25) |

0.677 0.002 |

1 2.72 (0.87–8.54) 97.89 (13.07–733.35) |

0.086 0.001 |

| Mother's long-term social

assistance No Yes |

1 2.10 (1.16–3.80) |

0.014 |

1 1.97 (1.39–2.79) |

< 0.001 |

1 1.84 (1.28–2.64) |

< 0.001 |

1 3.18 (2.29–4.42) |

< 0.001 |

| Mother's death No Yes |

1 1.17 (0.62–2.20) |

0.637 |

1 0.05 (0.00–108.66) |

0.443 |

1 0.61 (0.37–1.02) |

0.058 |

1 0.49 (0.00–120.09) |

0.449 |

| Sum of maternal risk

factors 0 1 2–5 |

1 5.00 (0.65–38.42) 8.79 (1.22–63.26) |

0.122 0.031 |

1 1.75 (1.22–2.52) 2.58 (1.70–3.91) |

0.003 < 0.001 |

1 3.25 (1.28–8.26) 4.23 (1.73–10.29) |

0.013 0.002 |

1 2.46 (1.70–3.57) 4.49 (3.04–6.64) |

< 0.001 < 0.001 |

| Out-of-home care | ||||||||

| No OHC At least once in OHC |

1 2.05 (1.21–3.45) |

0.007 | 1 3.44 (2.39–4.96) |

< 0.001 | 1 4.37 (2.89–6.61) |

< 0.001 | 1 8.55 (6.20–11.78) |

< 0.001 |

| Age at first OHC No placement < 7 years ≥ 7 years |

1 2.09 (1.22–3.58) 1.92 (0.97–3.81) |

0.007 0.062 |

1 5.48 (3.35–8.98) 2.54 (1.57–4.12) |

< 0.001 < 0.001 |

1 4.49 (2.95–6.84) 4.02 (2.44–6.60) |

< 0.001 < 0.001 |

1 8.86 (5.47–14.34) 8.40 (5.83–12.12) |

< 0.001 < 0.001 |

Note. HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; FASD = Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder; OHC = out-of-home care.

Among the controls, male sex, low birth weight, OHC and maternal adversities related to low socioeconomic status, mental and behavioural disorders, diagnosed substance abuse after delivery, long-term social assistance and a sum of maternal risk factors were all associated with F80–F83 diagnoses (Table 2).

The association between maternal adversities and F80–F83 diagnoses was stronger among the controls than the exposed, which may be due to the strong correlation between substance exposure and maternal adversities. The exposure status correlated strongly with the sum of maternal risk factors (0.638), mother's diagnosed substance abuse (0.675) and smoking (0.523), and moderately with mother's marital status (0.346) and mental and behavioural disorders (0.330). Moreover, OHC correlated strongly with the sum of maternal risk factors (0.594) and exposure status (0.582) (Appendix 1).

Conduct and emotional disorders (F90–F94).

Among the exposed, F90–F94 diagnoses were associated with being male, low birth weight, OHC and maternal adversities related to diagnosed substance abuse, long-term social assistance and a sum of maternal risk factors. In addition, diagnosed FASD was associated with a higher rate of F90–F94 diagnoses (Table 2).

Among the controls, F90–F94 diagnoses were associated with male sex, OHC, and maternal adversities: daily smoking throughout pregnancy, young age, being unmarried and low socioeconomic status at delivery, mental or behavioural disorders, diagnosed substance abuse after the delivery, long-term social assistance, criminality and a sum of maternal risk factors (Table 2).

Similarly to F80–F83 diagnoses, associations between maternal adversities and F90–F94 diagnoses were stronger among the controls than the exposed. In addition, the correlation between exposure status and F90–F94 diagnoses was stronger (0.287) than the correlation between exposure status and F80–F83 diagnoses (0.060) (Appendix 1).

Multivariable associations between prenatal substance exposure, childhood adversities and neurodevelopmental disorders

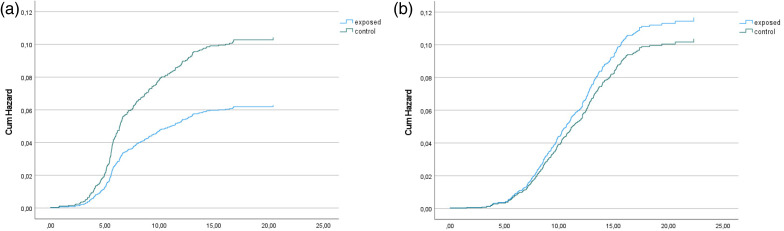

In the final Cox regression models, the main risk factors (based on results from Table 2 and on theoretical importance) of F80–F83 and F90–F94 diagnoses were added to the models. The difference between the exposed and controls in F80–F83 diagnoses was attenuated following the inclusion of maternal adversities and OHC in the analyses. Male sex, low birth weight, a sum of maternal risks and OHC were associated with F80–F83 diagnoses (Table 3, Figure 2(a)).

Table 3.

Association between childhood adversities and F80–F83 diagnoses from birth to early adulthood. Cox regression hazard models, N = 2402.

| Model 1 HR (95% CI) |

Model 2 HR (95% CI) |

Model 3 HR (95% CI) |

Model 4 HR (95% CI) |

Model 5 HR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure Controls Exposed |

1 1.47 (1.13–1.92) ** |

1 1.45 (1.06–1.99) * |

1 1.35 (0.96–1.90) |

1 0.74 (0.51–1.09) |

1 0.60 (0.41–0.90) * |

| Sex Female Male |

1 2.27 (1.74–2.97) *** |

1 2.26 (1.71–3.00) *** |

1 2.25 (1.70–2.98) *** |

1 2.23 (1.68–2.95) *** |

|

| Birth weight ≥ 2500 g < 2500 g |

1 2.74 (1.97–3.80) *** |

1 2.75 (1.95–3.88) *** |

1 2.77 (1.96–3.90) *** |

1 2.57 (1.82–3.62) *** |

|

| Exposure to smoking No Yes |

1 0.92 (0.68–1.25) |

1 0.85 (0.62–1.18) |

1 0.72 (0.52–0.99) |

1 0.67 (0.48–0.93) |

|

| Mother's socioeconomic status at

delivery High Low |

1 1.24 (0.95–1.63) |

1 1.08 (0.83–1.43) |

1 1.05 (0.80–1.38) |

||

| Mother's marital status at

delivery Married Not married |

1 1.05 (0.79–1.41) |

1 0.97 (0.73–1.30) |

1 0.94 (0.71–1.26) |

||

| Number of maternal risk

factors 0 1 2–5 |

1 1.98 (1.38–2.83) *** 3.37 (2.27–5.01) *** |

1 1.76 (1.22–2.54) ** 2.37 (1.53–3.69) *** |

|||

| Out-of-home care (OHC) No Yes |

1 2.23 (1.53–3.25) *** |

Note. HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval.

*p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

Figure 2.

(a) Hazard function for F80–F83 diagnoses among the exposed and controls after adjustment for covariates (sex, birth weight, exposure to smoking, mother's socioeconomic status, mother's marital status, sum of maternal risk factors and out-of-home care). Follow-up from birth until the first F80–F83 diagnosis, death or the end of the follow-up in 2016. (b) Hazard function for F90–F94 diagnoses among the exposed and controls after adjustment for covariates (sex, birth weight, exposure to smoking, mother's socioeconomic status, mother's marital status, sum of maternal risk factors and out-of-home care). Follow-up from birth until the first F90–F94 diagnosis, death or the end of the follow-up in 2016.

The difference between the exposed and controls in F90–F94 diagnoses diminished after adding maternal risk factors and especially OHC into the final model. F90–F94 diagnoses were associated with male sex, unmarried mother and low socioeconomic status at delivery, a sum of maternal risks and OHC. After adjustments of other independent variables, youths with OHC had a five times higher risk of conduct and emotional disorders than youths without OHC (HR = 5.10, 95% CI 3.71–7.01, p < 0.001) (Table 4, Figure 2(b)).

Table 4.

Association between childhood adversities and F90–F94 diagnoses from birth to early adulthood. Cox regression hazard models, N = 2402.

| Model 1 HR (95% CI) |

Model 2 HR (95% CI) |

Model 3 HR (95% CI) |

Model 4 HR (95% CI) |

Model 5 HR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure Controls Exposed |

1 4.18 (3.39–5.16) *** |

1 3.53 (2.74–4.56) *** |

1 2.88 (2.19–3.79) *** |

1 1.63 (1.20–2.22) ** |

1 1.13 (0.82–1.54) |

| Sex Female Male |

|

1 1.72 (1.39–2.13) *** |

1 1.64 (1.31–2.06) *** |

1 1.64 (1.31–2.06) *** |

1 1.66 (1.32–2.08)*** |

| Birth weight ≥ 2500 g < 2500 g |

|

1 1.39 (1.01–1.93)* |

1 1.56 (1.11–2.18)** |

1 1.53 (1.09–2.14)* |

1 1.34 (0.96–1.87) |

| Exposure to smoking No Yes |

|

1 1.35 (1.05–1.74)* |

1 1.28 (0.98–1.68) |

1 1.10 (0.84–1.43) |

1 0.89 (0.68–1.17) |

| Mother's socioeconomic status at

delivery High Low |

1 1.50 (1.18–1.91)*** |

1 1.37 (1.08–1.74)** |

1 1.28 (1.01–1.63)* |

||

| Mother's marital status at

delivery Married Not married |

1 1.46 (1.12–1.91)** |

1 1.38 (1.06–1.79)* |

1 1.34 (1.03–1.74)* |

||

| Number of maternal risk

factors 0 1 2–5 |

1 2.23 (1.58–3.15)*** 3.45 (2.42–4.92) *** |

1 1.67 (1.17–2.40) ** 1.65 (1.11–2.44) * |

|||

| Out-of-home care No Yes |

1 5.10 (3.71–7.01) *** |

Note. HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval.

*p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

Discussion

This study investigated the prevalence of neurodevelopmental disorders among youth with PSE in comparison to unexposed matched controls and environmental adversities associated with these disorders. The limitation of many previous studies has been the lack of a control group enabling the researchers to adjust for the effect of OHC and other ACEs. The present longitudinal study was able to fill this gap. The results showed that neurodevelopmental disorders were in general more common among exposed youth, but the magnitude of difference between the exposed and controls varied in different disorder categories and according to their OHC status and other childhood adversities.

Conduct and emotional disorders (F90–F94) were more common among the exposed than specific developmental disorders (F80–F83). This result is in line with previous studies, which show a high prevalence of emotional and behavioural dysregulation among children and youth with substance exposure (Irner, 2012; Popova et al., 2016; Weyrauch et al., 2017). The proportion of F90–F94 diagnoses was higher compared with the controls but only when the exposed without OHC were compared with the controls without OHC. The difference was seen in hyperkinetic disorders (ADHD, F90), mixed disorders of conduct and emotions (F92) and emotional disorders with onset specific to childhood (F93). All diagnoses in the F90–F94 category were as common among the controls with OHC as the exposed with OHC.

Regarding specific developmental disorders (F80–F83), the moderate difference between the exposed and controls attenuated when the results were stratified for OHC. Again, the rates were highest among the exposed with OHC and controls with OHC. Surprisingly, the controls with OHC were even more often diagnosed with deficits in speech and language development (F80) and motor function (F82) compared with the exposed with OHC. Many previous studies have found a higher prevalence of language and motor dysfunctions among the exposed (Irner, 2012; Mattson et al., 2019; Price et al., 2017; Riley et al., 2011). Language abilities are closely related to socioeconomic status, the linguistic environment and parent–child interaction (Noble et al., 2012; Pace et al., 2017), which may explain the difference between the results from the present study and previous studies.

Multivariable analyses showed that OHC and maternal risk factors, which were interrelated, were strongly associated with an increased risk of specific developmental disorders (F80–F83) and even more strongly with conduct and emotional disorders (F90–F94) among both the exposed and controls. The relationship between the mother's marital and socioeconomic status with neurodevelopmental disorders was weaker. Low birth weight and male sex were additional risk factors. Children who had ended up with OHC had the highest number of ACEs and the exposed also had poorer health at birth compared with those with no OHC as we have previously reported in Koponen et al. (2020a). The results reflect the mothers’ difficult life situations, difficulties in taking care of their children, and regarding the mothers of the exposed, also heavy maternal substance abuse during pregnancy.

The onset of disorders included in the F80–F83 and F90–F94 diagnosis categories (ICD-10) is in childhood, and these disorders are strongly related to the biological maturation of the central nervous system. ACEs causing severe stress and prolonged institutional rearing have detrimental consequences on the biological stress systems and the development of brain areas responsible for cognitive control, self-regulation and memory (De Bellis & Zisk, 2014; Miguel et al., 2019; Noble et al., 2012; Tottenham et al., 2010; van IJzendoorn et al., 2020). The results are in line with the view of Alberry et al. (2021) that a stressful postnatal environment may worsen the outcomes of PAE. In addition, Fisher et al. (2011) have shown that early adversities have an equal effect to PSE in the onset and growth of behaviour dysregulation during adolescence.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include the large sample size, matched control group, longitudinal design, the high-quality register data without response and recalling bias or subject loss (Aro et al., 1990; Gissler & Haukka, 2004; Sund, 2012) and the possibility to investigate the combined effect of PSE and many ACEs, which is in contrast to prior studies in the field (Pei et al., 2011; Price et al., 2017; Shonkoff et al., 2009). In Finland, publicly funded healthcare assures health services to all pregnant women, of whom almost all (99.7%) attend these services (Kahila et al., 2010). In addition, free-of-charge child and school health services increase the possibility that every child and adolescent is referred to special care when problems arise, providing validity to the present study.

As the exposed cohort represents only 0.4% of all children born in the Helsinki metropolitan area in 1992–2001, the study includes only the most severe spectrum of maternal substance abuse (Kahila et al., 2010). Moreover, registered diagnoses of mental and behavioural disorders from specialised care in hospitals may reflect more severe cases. Diagnoses from primary care were not included because they were not available for the complete study period.

As in all studies on prenatal substance exposure (Behnke et al., 2013), detailed information on the type, timing and amount of exposure is limited, despite regular substance use monitoring during the antenatal follow-up, and the results are likely to reflect the combined effect of alcohol and drugs. Further, the unexposed control group may include light alcohol use during pregnancy not seeking medical attention and, thus, not included in the mandatory health and social welfare registries. However, it is unlikely that maternal substance use during pregnancy could explain the higher rate of neurodevelopmental disorders among the controls with OHC compared with the exposed with no OHC. In addition, the range of childhood adversities is limited and information on fathers and on the quality of life in foster/adoptive care is lacking. Finally, despite the longitudinal design and analysis of the timing of ACEs, we are able to show only association, not causality, between ACEs and neurodevelopmental disorders.

Conclusion

This study is one of the first to show the strong association between OHC, other ACEs, and neurodevelopmental disorders typically related to prenatal substance exposure, especially alcohol exposure, such as disorders of attention, conduct and emotional functioning. By securing a safe and predictable caregiving environment for children with PSE, it is possible to prevent further risks caused by the environment and offer the best possible life to exposed children despite their disabilities caused by PSE. Every effort to support the caregiving abilities of mothers with difficult life situations should be made in health and social care. More research including brain research is needed to explore the combined effect of central nervous dysfunction present at birth and adverse experiences during childhood and adolescence.

Appendix 1. Spearman correlations between study variables, N = 2402

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Exposure status, ref control | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 2. | F80–F83, ref no | .060** | |||||||||||||

| 3. | F90–F94, ref no | .287** | .258** | ||||||||||||

| 4. | Sex, ref woman | −.021 | .120** | .085** | |||||||||||

| 5. | Birth weight, ref > 2500 g | .092** | .117** | .055** | −.020 | ||||||||||

| 6. | Mother's smoking, ref no | .523** | .026 | .195** | −.008 | .082** | |||||||||

| 7. | Socioeconomic status, ref high | .199** | .036 | .128** | −.001 | −.037 | .187** | ||||||||

| 8. | Marital status, ref married | .346** | .030 | .177** | .000 | .049* | .353** | .194** | |||||||

| 9. | Mother's mental or behavioural disorder, ref no | .330** | .078** | .171** | −.002 | .004 | .249** | .126** | .221 | ||||||

| 10. | Mother's diagnosed substance abuse, ref no | .675** | .098** | .275** | −.010 | .083** | .449** | .149** | .284** | .441** | |||||

| 11. | Mother's criminal record, ref no | .244** | .048* | .107** | .017 | .018 | .161** | .070** | .090** | .138** | .200** | ||||

| 12. | Mother's long-term social assistance, ref no | .552** | .113** | .281** | .005 | .054** | .418** | .273** | .272** | .367** | .518** | .245** | |||

| 13. | Mother's death, ref no | .257** | .017 | .023 | −.031 | .092** | .164** | .021 | .068** | .110** | .248** | −.036 | .143** | ||

| 14. | Sum of maternal risks, ref = 0 risks | .638** | .128** | .307** | −.009 | .064** | .467** | .264** | .321** | .718** | .717** | .266** | .789** | .255** | |

| 15. | OHC, ref no | .582** | .151** | .429** | .005 | .071** | .436** | .191** | .278** | .334** | .562** | .242** | .569** | .239** | .594** |

Note. OHC = out-of-home care.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01 or <0.001.

Footnotes

Availability of data and material: The data are not publicly available due to data confidentiality. The authors do not have permission to share the data, but similar data can be applied for from Findata, the Finnish Social and Health Data Permit Authority: https://findata.fi/en/.

Consent to participate: According to Finnish law, informed consent is not required in register studies when study subjects are not contacted.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval: The study has been approved by the local ethical committee of HUS (Dnro 333/E8/02). All register organisations have approved the use of their register data.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Samfundet Folkhälsan i svenska Finland rf., Juho Vainio Foundation, Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation, and Medicinska Understödsföreningen Liv och Hälsa rf.

ORCID iD: Anne M. Koponen https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2644-9095

Contributor Information

Anne M. Koponen, Folkhälsan Research Center; and University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

Niina-Maria Nissinen, Tampere University, Tampere, Finland.

Mika Gissler, Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, Helsinki, Finland; University of Turku, Turku, Finland; Academic Primary Health Care Centre, Stockholm, Sweden; and Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Ilona Autti-Rämö, Children’s Hospital, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland.

Hanna Kahila, Helsinki University Central Hospital, Helsinki, Finland.

Taisto Sarkola, Children’s Hospital, University of Helsinki; Helsinki University Hospital, Helsinki, Finland; and Minerva Foundation Institute for Medical Research, Helsinki, Finland.

References

- Ackerman J. P., Riggins T., Black M. M. (2010). A review of the effects of prenatal cocaine exposure among school-aged children. Pediatrics, 125(3), 554–565. 10.1542/peds.2009-0637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberry B., Laufer B. I., Chater-Diehl E., Singh S. M. (2021). Epigenetic impacts of early life stress in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders shape the neurodevelopmental continuum. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 14, 1–17. 10.3389/fnmol.2021.671891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda R. F., Felitti V. J., Bremner J. D., Walker J. D., Whitfield C. H., Perry B. D., Dube S. R., Giles W. H. (2006). The enduring effectsof abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. European Archives of Psychiatry & Clinical Neuroscience, 256(3), 174–186. 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aro S., Koskinen R., Keskimäki I. (1990). Reliability of hospital discharge data concerning diagnosis, treatments and accidents. Duodecim; Lääketieteellinen Aikakauskirja, 106(21), 1443–1450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke M., Smith V. C., & Committee on Substance Abuse. (2013). Prenatal substance abuse: Short-and long-term effects on the exposed fetus. Pediatrics, 131(3), e1009–e1024. 10.1542/peds.2012-3931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham-Howes S., Berger S. S., Scaletti L. A., Black M. M. (2013). Systematic review of prenatal cocaine exposure and adolescent development. Pediatrics, 131(6), e1917–e1936. 10.1542/peds.2012-0945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child Welfare Act. (2007). Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Finland, Act. No. 417/2007 . https://www.finlex.fi/en/laki/kaannokset/2007/en20070417_20131292.pdf

- Coggins T. E., Timler G. R., Olswang L. B. (2007). A state of double jeopardy: Impact of prenatal alcohol exposure and adverse environments on the social communicative abilities of school-age children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 38(2), 117–127. 10.1044/0161-1461(2007/012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis M. D., Zisk A. (2014). The biological effects of childhood trauma. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23(2), 85–222. 10.1016/j.chc.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easey K. E., Dyer M. L., Timpson N. J., Munafò M. R. (2019). Prenatal alcohol exposure and offspring mental health: A systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 197, 344–353. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher P. A., Lester B. M., DeGarmo D. S., Lagasse L. L., Lin H., Shankaran S., Bada H. S., Bauer C. R., Hammond J., Whitaker T., Higgins R. (2011). The combined effects of prenatal drug exposure and early adversity on neurobehavioral disinhibition in childhood and adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 23(3), 777–788. 10.1017/S0954579411000290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox S. E., Levitt P., Nelson C. A. I. I. I. (2010). How the timing and quality of early experiences influence the development of brain architecture. Child Development, 81(1), 28–40. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01380.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gissler M., Haukka J. (2004). Finnish health and social welfare registers in epidemiological research. Norsk Epidemiologi, 14(1), 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Henry J., Sloane M., Black-Pond C. (2007). Neurobiology and neurodevelopmental impact of childhood traumatic stress and prenatal alcohol exposure. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 38(2), 99–108. 10.1044/0161-1461(2007/010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyter Y. D. (2012). Complex trauma and prenatal alcohol exposure: Clinical implications. Perspectives on School-Based Issues, 13(2), 32–42. 10.1044/sbi13.2.32 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Irner T. B. (2012). Substance exposure in utero and developmental consequences in adolescence: A systematic review. Child Neuropsychology, 18(6), 521–549. 10.1080/09297049.2011.628309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S. B., Riis J. L., Noble K. G. (2016). State of the art review: Poverty and the developing brain. Pediatrics, 137(4), Article e20153075. 10.1542/peds.2015-3075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.04.014. Kahila, H., Gissler, M., Sarkola, T., Autti-Rämö, I. & Halmesmäki, E. (2010). Maternal welfare, morbidity and mortality 6-15 years after a pregnancy complicated by alcohol and substance abuse: A register-based case-control follow-up study of 524 women. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 111(3), 215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambeitz C., Klug M. G., Greenmyer J., Popova S., Burd L. (2019). Association of adverse childhood experiences and neurodevelopmental disorders in people with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) and non-FASD controls. BMC Pediatrics, 19(1), 1–9. 10.1186/s12887-019-1878-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/23507 Koponen, A. (2006). Sikiöaikana päihteille altistuneiden lasten kasvuympäristö ja kehitys. [Life of children exposed to alcohol or drugs in utero]. Doctoral dissertation, Faculty of Social Sciences, Department of Social Research, University of Helsinki, Finland. [Google Scholar]

- Koponen, A. M., Kalland, M. & Autti-Rämö, I. (2009). Caregiving environment and socio-emotional development of foster-placed FASD-children. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar]

- Koponen, A. M., Kalland, M., Autti-Rämö, I., Laamanen, R. & Suominen, S. (2013). Socio-emotional development of children with Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders in long-term foster family care: A qualitative study. Nordic Social Work Research, 3(1), 38–58. [Google Scholar]

- doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100625. https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S2352827320302627?token=BE28635D6814F880393986A562BB4FDF8A0362F626618AAEBF3092C4C7E7C0E00391903491F0EEF50C8F707F9F95FD4A Koponen, A. M., Nissinen, N-M., Gissler, M., Autti-Rämö, I., Sarkola, T. & Kahila, H. (2020a). Prenatal substance exposure, adverse childhood experiences and diagnosed mental and behavioral disorders - a longitudinal register-based matched cohort study in Finland. SSM Population Health, 11, 100625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- doi: 10.1177/1455072519885719. Koponen, A. M., Nissinen, N-M., Gissler, M., Sarkola, T., Autti-Rämö, I. & Kahila, H. (2020b). Cohort profile: ADEF Helsinki - a longitudinal register-based study on exposure to alcohol and drugs during fetal life. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 37(1). First published: December 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert B. L., Bauer C. R. (2012). Developmental and behavioral consequences of prenatal cocaine exposure: A review. Journal of Perinatology, 32(11), 819–828. 10.1038/jp.2012.90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson S. N., Bernes G. A., Doyle L. R. (2019). Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: A review of the neurobehavioral deficits associated with prenatal alcohol exposure. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 43(6), 1046–1062. 10.1111/acer.14040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel P. M., Pereira L. O., Silveira P. P., Meaney M. J. (2019). Early environmental influences on the development of children’s brain structure and function. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 61(10), 1127–1133. 10.1111/dmcn.14182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnes S., Lang A., Singer L. (2011). Prenatal tobacco, marijuana, stimulant, and opiate exposure: Outcomes and practice implications. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 6(1), 57–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble K. G., Houston S. M., Kan E., Sowell E. R. (2012). Neural correlates of socioeconomic status in the developing human brain. Developmental Science, 15(4), 516–527. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2012.01147.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace A., Luo R., Hirsh-Pasek K., Golinkoff R. M. (2017). Identifying pathways between socioeconomic status and language development. Annual Review of Linguistics, 3(1), 285–308. 10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011516-034226 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pei J., Denys K., Hughes J., Rasmussen C. (2011). Mental health issues in fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Journal of Mental Health, 20(5), 473–483. 10.3109/09638237.2011.577113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popova S., Lange S., Shield K., Mihic A., Chudley A. E., Mukherjee R. A., Bekmuradov D., Rehm J. (2016). Comorbidity of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 387(10022), 978–987. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01345-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price A., Cook P. A., Norgate S., Mukherjee R. (2017). Prenatal alcohol exposure and traumatic childhood experiences: A systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 80, 89–98. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley E. P., Infante M. A., Warren K. R. (2011). Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: An overview. Neuropsychology Review, 21(2), 73–80. 10.1007/s11065-011-9166-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross E. J., Graham D. L., Money K. M., Stanwood G. D. (2015). Developmental consequences of fetal exposure to drugs: What we know and what we still must learn. Neuropsychopharmacology, 40(1), 61–87. 10.1038/npp.2014.147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkola, T., Eriksson, C. P., Niemelä, O., Sillanaukee, P. & Halmesmäki, E. (2000). Mean cell volume and gamma-glutamyl transferase are superior to carbohydrate-deficient transferrin and hemoglobin-acetaldehyde adducts in the follow-up of pregnant women with alcohol abuse. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 79(5), 359–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00474.x. Sarkola, T., Kahila, H., Gissler, M. & Halmesmäki, E. (2007). Risk factors for out-of-home custody child care among families with alcohol and substance abuse problems. Acta Paediatrica, 96(11), 1571–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schempf A. H. (2007). Illicit drug use and neonatal outcomes: A critical review. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 62(11), 749–757. 10.1097/01.ogx.0000286562.31774.76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff J. P., Boyce W. T., McEwen B. S. (2009). Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: Building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. JAMA, 301(21), 2252–2259. 10.1001/jama.2009.754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Finland. (2019). Väestötieteen perusteet [Introduction to population demographics]. https://tilastokoulu.stat.fi/verkkokoulu_v2.xql?course_id=tkoulu_vaesto&lesson_id=5&subject_id=3&page_type=sisalto

- Streissguth A. P., Barr H. M., Kogan J., Bookstein F. L. (1996). Understanding the occurrence of secondary disabilities in clients with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) and fetal alcohol effects (FAE) (Final report). University of Washington School of Medicine.

- Streissguth A. P., Bookstein F. L., Barr H. M., Sampson P. D., O’Malley K., Young J. K. (2004). Risk factors for adverse life outcomes in fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol effects. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 25(4), 228–238. 10.1097/00004703-200408000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sund R. (2012). Quality of the Finnish hospital discharge register: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 40(6), 505–515. 10.1177/1403494812456637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottenham N., Hare T. A., Quinn B. T., McCarry T. W., Nurse M., Gilhooly T., Millner A., Galvan A., Davidson M. C., Eigsti I.-M., Thomas K. M., Freed P. J., Booma E. S., Gunnar M. R., Altemus M., Aronson J., Casey B. J. (2010). Prolonged institutional rearing is associated with atypically large amygdala volume and difficulties in emotion regulation. Developmental Science, 13(1), 46–61. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00852.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van IJzendoorn M. H., Bakermans-Kranenburg M. J., Duschinsky R., Fox N. A., Goldman P. S., Gunnar M. R., Johnson D. E., Nelson C. A., Reijman S., Skinner G. C. M., Zeanah C. H., Sonuga-Barke E. J. S. (2020). Institutionalisation and deinstitutionalisation of children 1: A systematic and integrative review of evidence regarding effects on development. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(8), 703–720. 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30399-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyrauch D., Schwartz M., Hart B., Klug M. G., Burd L. (2017). Comorbid mental disorders in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 38(4), 283–291. 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]