Abstract

Background:

Cognitive operations including pre-attentive sensory processing are markedly impaired in patients with schizophrenia (SCZ) but evidence significant interindividual heterogeneity, which moderates treatment response with nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) agonists. Previous studies in healthy volunteers have shown baseline-dependency effects of the α7 nAChR agonist cytidine 5′-diphosphocholine (CDP-choline) administered alone and in combination with a nicotinic allosteric modulator (galantamine) on auditory deviance detection measured with the mismatch negativity (MMN) event-related potential (ERP).

Aim:

The objective of this pilot study was to assess the acute effect of this combined α7 nAChR-targeted treatment (CDP-choline/galantamine) on speech MMN in patients with SCZ (N = 24) stratified by baseline MMN responses into low, medium, and high baseline auditory deviance detection subgroups.

Methods:

Patients with a stable diagnosis of SCZ attended two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled and counter-balanced testing sessions where they received a placebo or a CDP-choline (500 mg) and galantamine (16 mg) treatment. MMN ERPs were recorded during the presentation of a fast multi-feature speech MMN paradigm including five speech deviants. Clinical measures were acquired before and after treatment administration.

Results:

While no main treatment effect was observed, CDP-choline/galantamine significantly increased MMN amplitudes to frequency, duration, and vowel speech deviants in low group individuals. Individuals with higher positive and negative symptom scale negative, general, and total scores expressed the greatest MMN amplitude improvement following CDP-choline/galantamine.

Conclusions:

These baseline-dependent nicotinic effects on early auditory information processing warrant different dosage and repeated administration assessments in patients with low baseline deviance detection levels.

Keywords: α7 nAChR, CDP-choline, galantamine, MMN, sensory memory

Introduction

The cholinergic system: A sensory/cognition target in schizophrenia

Sensory dysfunction in schizophrenia (SCZ) is directly associated with patients’ functional disability and has proven to be non-responsive to neuroleptics targeting dopamine receptors, despite these treatments’ effectiveness in alleviating positive clinical symptoms (Javitt and Freedman, 2015). Evidence associating pathophysiology of the cholinergic system, precisely α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR), with sensory and cognitive dysfunction in SCZ, further validates this receptor’s designation as a top pharmacological target by the measure and treatment research to improve cognition in schizophrenia (MATRICS) (Azzopardi et al., 2013; Braff, 2011; Jones et al., 2016; Mackowick et al., 2014). However, a gap remains in finding an effective cholinergic treatment and given increasing evidence that early “bottom-up” pre-attentive processes contribute to clinical, cognitive and functional symptoms in SCZ (Dondé et al., 2019a, 2019b; Koshiyama et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2017), sensory processes are considered a viable target in α7 drug development and treatment (Hashimoto, 2015; Olincy and Stevens, 2007; Smucny and Tregellas, 2017). Therefore, the general objective of this study was to examine the effect of a combined treatment, targeting the α7 nAChR, on measures of early auditory information processing in individuals with SCZ.

SCZ is a multigenic neurodevelopmental disorder with reported impairments in brain regions essential for sensory and cognitive functioning (Court et al., 1999; Freedman et al., 1995; Guan et al., 2000; Leonard and Freedman, 2006). The α7 nAChR and its coding gene (CHRNA7) have been associated with cognitive processing in learning, memory, and attention, and with pre-attentive sensory gating and deviance processing (Bertelsen et al., 2015; D’Souza and Markou, 2012; Leonard and Freedman, 2006; Mackowick et al., 2014; Ochoa and Lasalde-Dominicci, 2007; Sinkus et al., 2015; Young and Geyer, 2013). Despite the early success in preclinical trials and in early phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials, adjunctive treatment in SCZ with novel α7 nAChR agonists have been unsuccessful in larger phase 3 trials (Recio-Barbero et al., 2021). Contributing factors suggested to contribute to this lack of success include amongst others, a failure to: (a) focus on low agonist concentrations in order to offset the rapid desensitization of α7 nAChRs in response to high dose ligand binding (Tregellas and Wylie, 2019) and (b) exclude patients with relatively “normal” cognitive/sensory performance who are likely not to benefit from a pro-cognitive agent (Lewis et al., 2017; Terry and Callahan, 2020).

In parallel, positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) have been considered as an alternative approach increasing nAChR activity via orthosteric binding sites (Wallace and Bertrand, 2015). Hence, a synergistic strategy administering a selective α7 nAChR agonist, cytidine 5′-diphosphocholine (CDP-choline; a precursor and metabolite of acetylcholine), with a nAChR PAM, galantamine, was initially examined over 10 years ago (Deutsch et al., 2008a, 2008b, 2013) and recently with a novel electrophysiological biomarker-based baseline stratification approach which showed improved measures of auditory sensory gating, and auditory deviance detection deficits indexed in electroencephalography (EEG) derived P50 and mismatch negativity (MMN) event-related potentials (ERPs), respectively (Choueiry et al., 2019a, 2019b, 2020).

The MMN is typically elicited during the presentation of an “oddball” paradigm where a series of standard auditory stimuli (tones) are interrupted by a novel stimulus distinguished by a variation in tonal physical features, including frequency, intensity, duration, location, or even the omission of the sound. Auditory deviance detection measured with the MMN is thought to reflect early, pre-attentive processing, indexing the integrity of sensory “echoic” memory traces of the sound environment and prediction-error signaling mechanisms generating the MMN response (El Karoui et al., 2015; Javitt, 1996, 2000; Rosburg et al., 2005). This mature ERP is recognized as a biomarker and genomic endophenotype in SCZ following numerous replicability studies ascertaining robust attenuation of the MMN in SCZ (Näätänen and Kähkönen, 2009), and associations of lower MMN amplitudes with the severity of clinical features (i.e., hallucinations) and cognitive and social dysfunction in first-episode, and both medicated and non-medicated chronic SCZ (Näätänen et al., 2016). It has also been shown to predict conversion into psychosis in children at high-risk (Bodatsch et al., 2011; Perez et al., 2014). And most recently, treatment-related improvement in MMN measures was shown to be associated with improvements in clinical features (hallucinations; Francis et al., 2020) and attention and memory processing (Javitt et al., 2018). Thus, further reinforcing the implication of MMN as a translatable neural biomarker aiding in the development of novel therapeutic methods and pharmaceuticals in SCZ (Butler et al., 2012; Green et al., 2009; Nagai et al., 2013; Tada et al., 2019; Todd et al., 2013).

MMN modulation in schizophrenia

The MMN is thought to represent trial-by-trial encoding of prediction errors (i.e., where “deviant” does not match preceding “standard” template) which is likely dependent on N-methyl-d-aspertate receptor (NMDAR)-dependent plasticity at glutamatergic synapses (Harris et al., 1984; Wigström and Gustafsson, 1984). The NMDAR antagonist ketamine robustly reduces MMN amplitude across different deviant types including speech in humans (de La Salle et al., 2019; Rosburg and Kreitschmann-Andermahr, 2016). This effect is replicable in rats (Ehrlichman et al., 2008) and mice (Javitt, 1996) and in genetic models of NMDAR hypofunction (Light and Braff, 2005; Umbricht and Krljesb, 2005). Although the NMDA-targeted approach continues to evolve with the objective of finding an effective cognitive enhancement compound, recent evidence also suggests that nAChRs have the potential to modulate NMDA receptors and glutamatergic signaling in the CA1 hippocampal region (Bali et al., 2017, 2019).

The modulatory effect of the prototypical nAChR agonist nicotine on measures of MMN in earlier studies (Baldeweg et al., 2006; Dulude et al., 2010; Fisher et al., 2012a; Inami et al., 2005; Kohlhaas et al., 2015; Martin et al., 2009; Mathalon et al., 2014) was followed by CDP-choline-enhanced MMN amplitudes in healthy volunteers and SCZ patients with marked reductions in MMN amplitudes (Aidelbaum et al., 2021; Knott et al., 2015a). Galantamine alone has not yet been examined on sensory/sensorimotor functioning in SCZ. However, this PAM improved impaired cognitive functioning (Buchanan et al., 2008) and its combination with memantine (an NMDA receptor antagonist) was proposed to accentuate memantine’s improvement of sensorimotor gating in SCZ (Koola, 2018; Swerdlow et al., 2016).

Baseline-dependency effects

Significant clinical and cognitive heterogeneity in SCZ (Joyce and Roiser, 2007; Seaton et al., 1999) and a highly variable response in the treatment of SCZ (Stroup, 2007) have demonstrated the need for a meaningful subtyping schema (Ahmed et al., 2018), including sample stratification approaches (Takahashi, 2013) and the use of endophenotypes (Albus, 2012) to characterize subgroups of SCZ for more personalized intervention strategies (Malhotra, 2015). At the basic sensory level, findings of interindividual differences in early auditory processing indexed by the tone-matching task (TMT) were reflected by a bi-modal distribution of early auditory processing deficits, with SCZ patients exhibiting markedly impaired performance showing poorer cognitive performance and functional capacity (Dondé et al., 2017, 2019a) as well as greater cognitive benefits from auditory-training (Medalia et al., 2019) compared to patients with intact (TMT) performance. Interindividual differences in cognitive response to nAChR agonists are in part due to differences in baseline performance levels (Perkins, 1999) and parsing nicotinic effects on the basis of baseline levels of behavioral and electrophysiological markers has revealed subpopulations of responders and non-responders with regards to nicotine and CDP-choline effects on sensory gating (Knott et al., 2013, 2014a), MMN (Knott et al., 2014b, 2015a), P300 (Hyde et al., 2016), and cognition (Knott et al., 2015b) in healthy individuals and SCZ (Aidelbaum et al., 2021); antipsychotic treatment effects on sensory gating (Adler et al., 2004, 2005); and combined CDP-choline/galantamine treatment effects on sensory gating in healthy and SCZ participants (Choueiry et al., 2019a, 2019b) and deviance detection in healthy low-baseline amplitude groups (Choueiry et al., 2020).

Objectives and hypothesis

With respect to these recent findings, the specific objective of this preliminary pilot study was to assess the acute effect of a combined CDP-choline/galantamine treatment on auditory deviance detection assessed in patients with SCZ segregated by baseline MMN amplitude into low, medium, and high deviance detection subgroups. Although typically assessed in response to simple (tone) stimuli, MMNs will be examined in response to speech stimuli in an attempt to assess nicotinic-sensory processing relationships in a more clinically meaningful context, particularly in light of the impairments in speech and language functions observed in SCZ (Carrión et al., 2015; Revheim et al., 2014).

Relative to placebo, the combined acute administration of CDP-choline and galantamine was expected to improve speech deviance detection (increased MMN amplitudes) in SCZ individuals who express lower baseline detection (smaller MMN amplitudes). This corresponds to our previous outcomes in which showed improvements in deviance detection (larger MMNs) during a dose-response study of CDP-choline in more impaired SCZ (Aidelbaum et al., 2021) and healthy individuals (Knott et al., 2015a).

Clinical measures of positive, negative, and general symptoms were analyzed as an exploratory secondary objective as previous studies have shown an association between MMN measures and SCZ clinical ratings (Fisher et al., 2011, 2012b; Ghajar et al., 2018).

Materials and methods

Study participants

Twenty-six chronic SCZ patients were recruited from the Schizophrenia Outpatient Program at The Royal Ottawa Mental Health Centre. Eligible participants had a SCZ diagnosis based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, 4th Edition: DSM-IV, with a clinically stable status for a minimum of 90 days prior to study recruitment, assessed with the positive and negative symptom scale (PANSS; Kay et al., 1987). Recruited patients with SCZ were on a stable neuroleptic regimen for at least 4 weeks consisting of a one- or a combination of these treatments: aripiprazole, risperidone, flupentixol, haloperidol, paliperidone, levomepromazine, olanzapine, perphenazine, quetiapine, trifluoperazine, ziprasidone. Individuals taking clozapine were not selected to participate. Mixed findings have been previously reported for this treatment’s effect on cognition and electrophysiological measures of sensory gating (P50) and deviance detection (Sanchez-Morla et al., 2009; Su et al., 2012). Study exclusion factors included other DSM-IV disorders, medical illness, a recent (<6 months) head injury with loss of consciousness, and hearing impairment (as measured audiometrically). Individuals who participated in this study were assessed and showed normal laboratory and drug screen tests, normal weight, and normal hearing. All study procedures and participant recruitment, assessment, and testing, were in compliance with the Research Ethics Boards of The Royal Ottawa Mental Health Care Group and the University of Ottawa. Participants signed an informed consent form prior to undertaking any study procedure and received $100 following study completion. The final study sample of 24 participants consisted of 7 females and 17 males, with 8 non-smokers and 16 smokers, and a mean age of 44.5 years, SE ±2.06. One participant dropped out before study completion, and another participant’s data was discarded due to significant EEG recording artifacts. Non-smoking status relied on participant attestation that they had consumed less than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and had not used any tobacco products within the past year prior to study recruitment. Smokers had been smoking for an average of M = 24.3, SE ±2.0 years, consuming on average M = 16.6, SE ±1.9 cigarettes per day. Participants’ medications were all evaluated for anticholinergic impact. Each participant was allocated an anticholinergic cognitive burden score (Boustani et al., 2008) that was later examined for its relationship with CDP-choline/galantamine effects and for comparing subgroup differences amongst low group (LG), medium group (MG), and high group (HG) scores. First, each medication the participant is prescribed was given a score from 1 to 3 based on the anticholinergic cognitive burden score table which assigns a value of 1–3 to medications that exert a mild, moderate, and severe anticholinergic effect (Table 1 in Boustani et al. (2008); drugs that do not exert an anticholinergic effect were valued at 0). Second, the anticholinergic scores of the different drugs taken by the participant were added together to give the total anticholinergic cognitive burden score for each participant.

Table 1.

Demographics for LG (N = 8), MG (N = 8), and HG (N = 8) amplitude subgroups for each MMN deviant type separately. LG, MG, and HG were not significantly different for each demographic measure.

| Frequency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LG | MG | HG | Group analysis | |

| Age (mean ± SE) | 44.5 (2.77) | 47.4 (3.87) | 41.6 (4.12) | F(2, 23) = 0.626, p = 0.545 |

| Sex (F/M) | 2/6 | 4/4 | 1/7 | FET = 2.607, p = 0.402 |

| Smoking status (NS/S) | 3/5 | 3/5 | 2/6 | FET = 0.523, p = 1.0 |

| Intensity | ||||

| LG | MG | HG | Group analysis | |

| Age (mean ± SE) | 42.1 (3.65) | 48 (3.34) | 43.4 (3.84) | F(2, 23) = 0.732, p = 0.493 |

| Sex (F/M) | 2/6 | 3/5 | 2/6 | FET = 0.547, p = 1.00 |

| Smoking status (NS/S) | 3/5 | 2/6 | 3/5 | FET = 0.523, p = 1.0 |

| Duration | ||||

| LG | MG | HG | Group analysis | |

| Age (mean ± SE) | 46.6 (1.98) | 46.6 (3.95) | 40.2 (4.32) | F(2, 23) = 1.066, p = 0.362 |

| Sex (F/M) | 3/5 | 3/5 | 1/7 | FET = 1.667, p = 0.619 |

| Smoking status (NS/S) | 3/5 | 3/5 | 2/6 | FET = 0.523, p = 1.0 |

| Consonant | ||||

| LG | MG | HG | Group analysis | |

| Age (mean ± SE) | 47.1 (2.85) | 39.5 (2.46) | 46.9 (4.74) | F(2, 23) = 1.537, p = 0.238 |

| Sex (F/M) | 2/6 | 0/8 | 5/3 | FET = 7.212, p = 0.031 |

| Smoking status (NS/S) | 2/6 | 3/5 | 3/5 | FET = 0.523, p = 1.0 |

| Vowel | ||||

| LG | MG | HG | Group analysis | |

| Age (mean ± SE) | 44.4 (2.39) | 43.5 (3.49) | 45.6 (4.88) | F(2, 23) = 0.082, p = 0.921 |

| Sex (F/M) | 1/7 | 2/6 | 4/4 | FET = 2.607, p = 0.402 |

| Smoking status (NS/S) | 3/5 | 1/7 | 4/4 | FET = 2.582, p = 0.418 |

LG: Low group; MG: Medium group; HG: High group; FET: Fisher’s exact test score; F/M: female/male; NS/S: non-smokers/smokers.

Experimental design

A randomized, double-blinded, and counterbalanced design was employed to assess study volunteers during both a placebo treatment session and an active treatment (CDP-choline + galantamine) session. An equal number of participants started with the placebo as with the treatment session.

To examine the active CDP-choline/galantamine treatment effect within our stratification approach, for each deviant type separately, MMN amplitude measures from the baseline (placebo) treatment condition were used to subgroup the total sample of SCZ participants into low (LG), medium (MG), and high (HG) amplitude individuals. MMN amplitudes at midline frontal (Fz) were used to rank participants’ deviance detection with the first eight participants with the lowest MMN values comprising the LG, the next eight participants comprised the MG, and the eight remaining participants exhibiting the highest MMN amplitudes comprised the HG.

Treatment administration

Non-active placebo capsules (250 mg of cellulose) matched the active treatment capsules (2 × 250 mg capsules of CDP-choline and 1 × 250 mg capsule containing 16 mg of galantamine + 234 mg of cellulose) in shape, size, and colour. Participants ingested two (cellulose or CDP-choline-filled capsules) at study time 0 min and a single capsule (filled with cellulose or galantamine) 60 min later.

Experimental procedure

The two testing sessions started between 8:00 am and 11:30 am (starting time was maintained consistent for both sessions for each participant). Upon arrival at the laboratory, participants verbally confirmed abstinence from food, drugs (neuroleptics for treating SCZ were taken as usual), alcohol, caffeine, and tobacco. Smoking abstinence was further verified with a measurement of exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) that had to be lower than 3 ppm for non-smokers and less than the exhaled CO level at the screening session for smokers. Participants were then asked to orally consume two capsules consisting of either the placebo or active (CDP-choline) treatment (time 0 min). Participants were asked to remain seated and relaxed in a sound-attenuated chamber where they watched an emotionally neutral movie of their choice during the treatment absorption period. After 60 min later, the second placebo or active (galantamine) treatment was administered, and the absorption period continued for an additional 60 min. MMN paradigm presentation and recording began at peak CDP-choline/galantamine absorption time (120 min).

MMN paradigm

During the presentation of the fast multi-feature speech MMN paradigm, participants remained seated as they watched a silent video (The Blue Planet by BC, 2001).

Stimuli

Finnish-language consonant-vowel /te:/ and /pi:/ (F0: 101 Hz, syllable duration: 170 ms, and intensity: 70 dB (sound pressure level (SPL; Pakarinen et al., 2009)) stimuli were projected binaurally through noise-canceling headphones. Deviant stimuli differed from the standard in syllable frequency (FRE), intensity (INT), vowel duration (DUR), and a change of consonant (CON) or vowel (VOW). An 8% increase or decrease in intensity was applied to FRE deviants (F0 ±8%, 93/109 Hz, with an equal distribution between the higher and lower presentations). In comparison to standard stimuli, INT deviants varied in ±6 dB with an equal number of presentations of both quieter and louder deviants). DUR deviants were 70 ms shorter than the standard stimuli. The MMN paradigm was presented in four blocks. Two blocks used /te/ standard stimuli and presented /pe/ syllables as CON deviants and /ti/ syllables as VOW deviants. The other two blocks used /pi/ standard stimuli and presented /ti/ syllables as CONS deviants and /pe/ syllables as VOW deviants.

Presentation

In accordance with the optimum-1 MMN paradigm (Näätänen et al., 2004) presentation sequence recommendation, each of the four 5-min MMN blocks included 465 syllables (1860 stimuli in total) where every other syllable was a standard (p = 0.5), with one of the five deviant syllables (p = 0.1, for each deviant type) in between. Each block was initiated with five standard syllables. Syllable presentation was pseudo-randomized to ensure that every deviant type appeared once within the presentation of 10 successive stimuli and ensuring that the same deviant was not to be repeated consecutively after the standard following it. The presentation order of the standard /te:/ and /pi:/ sequence blocks were randomized amongst participants.

ERP recording and processing

Brain Vision Quickamp® (Brain Products GmbH, Munich, Germany) amplifier and Brain Vision Recorder® software were used to record EEG signals. The amplifier bandpass filter was set at 0.1–70 Hz with a 500 Hz continuous digitization. Based on the 10/10 international system (Jurcak et al., 2007), 30 Ag+/Ag+ Cl− electrodes were positioned at scalp sites: Fp1, Fp2, F3, F4, C3, C4, P3, P4, O1, O2, F7, F8, T7, T8, P7, P8, Fz, Cz, Pz, Oz, FC1, FC2, CP1, CP2, FC5, FC6, CP5, CP6, TP9, and TP10. Electrode impedance was kept below 5 kΏ throughout the recording session using a reference electrode placed on the nose and a ground electrode placed at the AFz site. Vertical and horizontal electro-oculographic activity were measured using electrodes placed on the supra- and sub-orbital ridges of the right eye and on the external canthus of both eyes, respectively.

Brain Vision Analyzer® (Brain Products GmbH, Munich, Germany) software was used for offline processing and analysis of EEG signals. Raw signals were processed in the following order using a 24 dB/octave digital filter initially with a low-high cutoff window of 1–20 Hz, followed with ocular-correction (Gratton et al., 1983), segmentation into 500 ms epochs (starting at 100 ms pre-stimulus onset), an automatic artifact rejection eliminating epochs showing voltages surpassing ±75 µV, and using the 100 ms pre-stimulus electrical activity a baseline-correction was applied. Epochs for each deviant and standard stimulus were averaged separately, and difference waveforms were derived by digital point-by-point subtraction of the standard waveform voltage values from the deviance waveform values.

The greatest negative peak occurring between 100 and 250 ms post-stimulus onset was used to quantify MMN peak amplitude and latency at frontal (Fz, F3, and F4) (Näätänen et al., 2004).

Clinical measures

The severity of positive symptoms (e.g., delusions, hallucinations, score ranges from 7 to 49) and negative symptoms (e.g., blunted affect, emotional withdrawal, ranging from 7 to 49) are highlighted by the positive and negative subscale scores, respectively. The general psychopathology subscale includes symptoms of anxiety, tension, and depression (ranging from 16 to 112), and the sum of all three subscales makes up the PANSS total score (M = 62.25, SE ±2.8) (Kay et al., 1987).

Adverse events

At the end of each testing session, participants were asked to rate the severity of symptoms experienced following treatment administration on a scale from 1 (no symptom at all) to 5 (severe symptom) on a checklist of physical and psychological adverse events associated with nicotinic cholinergic stimulation.

Vital signs

Participants’ heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure were measured before treatment administration (at time 0 min, before the administration of the first treatment) and at peak absorption time (~90 min) for safety purposes only.

Statistical analysis

Recorded MMN amplitude measures from the frontal (Fz) electrode site were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (SPSS; IBM Corporation, New York, NY, USA). MMN amplitudes to each of the deviant types (FRE, INT, DUR, CON, and VOW) were used separately (each deviant type as an independent measure) in all of the analysis presented.

The overall effect of the active CDP-choline/galantamine treatment on measures of MMN amplitudes for each deviant type (separately) in the full group sample was analyzed using separate repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with within-subject factors consisting of treatment (two levels, placebo treatment vs CDP-choline/galantamine treatment) at electrode scalp position Fz. Bonferroni-adjusted planned comparisons were followed-up for significant effects (p < 0.05), and Greenhouse–Geisser corrected.

The group stratification of LG, MG, and HG, was used as a between-subjects factor (three levels) in repeated measures ANOVAs for each deviant type separately with treatment (two levels: placebo, CDP-choline/galantamine) as within-subjects repeated measures factors. Significant Greenhouse–Geisser corrected effects (p < 0.05) were followed-up with Bonferroni-adjusted planned comparisons. As any group differences in treatment response may reflect a “regression to the mean” effect, similar ANOVAs were conducted with participants stratification using active treatment (i.e., not placebo) MMN scores.

Chlorpromazine equivalent (CPZ; mg/day) was assessed separately for each MMN deviant type (separately) using one-way ANOVAs to verify any LG, MG, and HG participants differences with respect to their current neuroleptic treatment and hence eliminate a potential association of deviance detection subgroup differences with current neuroleptic treatment differences.

Potential between-group differences were assessed using Fisher’s exact test analysis for gender (female/male) and smoking status (non-smoker/smoker), and one-way ANOVAs to assess age, PANSS scores, anticholinergic load (Chew et al., 2008; Salahudeen et al., 2015), and chlorpromazine equivalent score (Leucht et al., 2016). Spearman’s correlations were employed to examine relationships between treatment-induced MMN change (indexed by difference scores (CDP-choline/galantamine MMN amplitude minus placebo MMN amplitude)) and positive, negative, general, and total PANSS scores.

Results

Demographic and clinical measures

Twenty-four participants with SCZ were part of the final sample included in this study (Mage = 44.5 years, SE ±2.06) and consisted of 7 females and 17 males, 8 non-smokers and 16 smokers. Demographic data for baseline low (LG), medium (MG), and high (HG) amplitude responder subgroups for each deviant type are presented in Table 1. LG, MG, and HG subgroups were not statistically distinguished based on age, gender, or smoking status following one-way ANOVAs (for age) and Fisher’s test (for gender and smoking status) analysis. Also, ANOVAs and post hoc analyses confirmed that LG, MG, and HG individuals did not score differently on PANSS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean (±SE) anti-cholinergic load, chlorpromazine equivalent (mg/day), and psychometric scores for LG (N = 8), MG (N = 8), and HG (N = 8) amplitude subgroups for each MMN deviant type separately.

| LG | MG | HG | Group analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | ||||

| Anticholinergic load score | 3.50 (0.54) | 5.75 (1.25) | 4.38 (1.19) | F(2, 23) = 1.179, p = 0.051 |

| CPZ equivalent (mg/day) | 669 (149) | 728 (171) | 711 (188) | F(2, 23) = 0.320, p = 0.969 |

| PANSS total | 67.13 (4.28) | 55.5 (3.78) | 64.13 (5.85) | F(2, 23) = 1.634, p = 0.219 |

| PANSS positive | 16.88 (1.47) | 15.38 (1.07) | 16 (1.07) | F(2, 23) = 0.383, p = 0.686 |

| PANSS negative | 17.5 (1.64) | 13.5 (1.94) | 18.13 (1.46) | F(2, 23) = 2.209, p = 0.135 |

| PANSS general | 33.38 (2.16) | 26.5 (2.29) | 30 (4.58) | F(2, 23) = 1.149, p = 0.336 |

| Intensity | ||||

| Anticholinergic load score | 4.38 (0.653) | 6.25 (1.21) | 3.00 (1.00) | F(2, 23) = 2.771, p = 0.086 |

| CPZ equivalent (mg/day) | 681 (134) | 952 (203) | 476 (108) | F(2, 23) = 2.399, p = 0.115 |

| PANSS total | 62 (6.87) | 64.75 (4.07) | 60 (3.45) | F(2, 23) = 0.225, p = 0.8 |

| PANSS positive | 16.88 (1.39) | 17.13 (1.17) | 14.25 (0.75) | F(2, 23) = 1.961, p = 0.166 |

| PANSS negative | 16.88 (1.83) | 15.13 (1.59) | 17.13 (2.04) | F(2, 23) = 0.356, p = 0.705 |

| PANSS general | 28.88 (4.84) | 32.38 (2.63) | 28.63 (1.64) | F(2, 23) = 0.4, p = 0.675 |

| Duration | ||||

| Anticholinergic load score | 4.50 (1.27) | 4.13 (0.83) | 5.00 (1.13) | F(2, 23) = 0.161, p = 0.852 |

| CPZ equivalent (mg/day) | 606 (159) | 757 (152) | 746 (192) | F(2, 23) = 0.247, p = 0.783 |

| PANSS total | 59.5 (3.61) | 66.38 (4.83) | 60.88 (6.10) | F(2, 23) = 0.54, p = 0.591 |

| PANSS positive | 15.38 (1.0) | 18.13 (1.29) | 14.75 (1.01) | F(2, 23) = 2.626, p = 0.096 |

| PANSS negative | 15.25 (1.52) | 16.25 (2.04) | 17.63 (1.86) | F(2, 23) = 0.429, p = 0.657 |

| PANSS general | 29.5 (2.10) | 32 (2.62) | 28.38 (4.69) | F(2, 23) = 0.311, p = 0.736 |

| Consonant | ||||

| Anticholinergic load score | 3.88 (0.95) | 4.88 (0.97) | 4.88 (1.30) | F(2, 23) = 0.282, p = 0.757 |

| CPZ equivalent (mg/day) | 570 (111) | 834 (196) | 705 (178) | F(2, 23) = 0.635, p = 0.540 |

| PANSS total | 65.75 (3.92) | 61.88 (5.04) | 59.13 (5.78) | F(2, 23) = 0.448, p = 0.645 |

| PANSS positive | 17 (0.96) | 15.25 (1.48) | 16 (1.12) | F(2, 23) = 0.527, p = 0.598 |

| PANSS negative | 16.38 (2.01) | 16.63 (1.77) | 16.13 (1.78) | F(2, 23) = 0.018, p = 0.982 |

| PANSS general | 32.25 (2.03) | 30.63 (3.28) | 27 (4.16) | F(2, 23) = 0.674, p = 0.52 |

| Vowel | ||||

| Anticholinergic load score | 3.25 (0.56) | 4.50 (1.13) | 5.88 (1.25) | F(2, 23) = 1.642, p = 0.217 |

| CPZ equivalent (mg/day) | 670 (144) | 728 (208) | 711 (151) | F(2, 23) = 0.030, p = 0.971 |

| PANSS total | 70.63 (3.59) | 64.88 (3.18) | 51.25 (5.10) | F(2, 23) = 6.062, p = 0.008 |

| PANSS positive | 17.5 (1.22) | 15.63 (1.34) | 15.13 (0.93) | F(2, 23) = 1.132, p = 0.341 |

| PANSS negative | 18.75 (1.73) | 16.75 (1.51) | 13.63 (1.78) | F(2, 23) = 2.37, p = 0.118 |

| PANSS general | 35 (1.64) | 32.38 (2.29) | 22.5 (3.73) | F(2, 23) = 5.973, p = 0.009 |

Anticholinergic load score based on neuroleptics that are known to interact (i.e., congentin, risperidone, haloperidol, olanzapine, perphenazine, quetiapine, procyclidine, dimenhydrinate, bupropion, stelazine, ranitidine, hydrochlorothiazide, trihexyphenidyl, oxybutynin) with the cholinergic system (Chew et al., 2008; Salahudeen et al., 2015). CPZ equivalents (mg/day) were calculated according to Leucht et al. (2016). The positive, negative, and general scales are subscales from the PANSS.

MMN amplitude measures

Total group

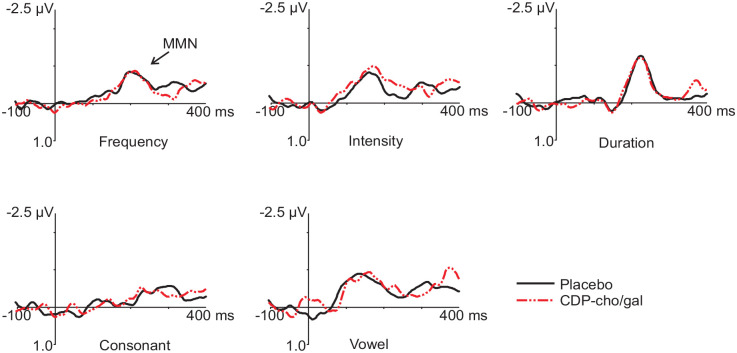

No main drug effect was observed in the total group sample for any of the MMN deviants. Grand averaged difference (deviant minus placebo) waveforms for each deviant type during placebo and CDP-choline/galantamine treatment conditions are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Frontal (Fz) ERP grand averaged difference waveforms (deviant minus standard) for the five deviants during placebo and CDP-choline/galantamine (CDP-cho/gal) conditions.

Group comparisons

No main drug effect was observed for any of the MMN deviants.

As expected, based on the study design, main group effects were observed for all deviant types portraying significant amplitude differences amongst LG, MG, and HG (Figure 2). Follow-up analyses revealed significantly smaller amplitudes for LG in comparison to HG for all deviants and significantly smaller amplitudes for LG in comparison to MG for INT and VOW deviants.

Figure 2.

Baseline (placebo) grand averaged frontal (Fz) difference waveforms (deviant minus standard) for the five deviants in the total sample and in LG (low), MG (medium), and HG (high) amplitude MMN subgroups. *p ⩽ 0.01.

Significant treatment × group interactions were observed for FRE (F(2, 21) = 9.72, p = 0.001, ), DUR (F(2, 21) = 11.19, p < 0.001, ), CON (F(2, 21) = 6.30, p = 0.07, ), and VOW (F(2, 21) = 10.24, p = 0.001, ) deviants only (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Frontal (Fz) grand averaged difference waveforms (deviant minus standard) for the five deviants in LG (low), MG (medium), and HG (high) participants during placebo and CDP-choline/galantamine (CDP-cho/gal) conditions. *p < 0.05.

Follow-up comparisons for FRE, DUR, and VOW deviants revealed that CDP-choline/galantamine (vs placebo) significantly increased MMN amplitudes in LG (pFRE = 0.005, ; pDUR = 0.003, ; pVOW = 0.004, ). The opposite effect was observed for HG with CDP-choline/galantamine for FRE, DUR, CON, and VOW showing smaller amplitudes in comparison to placebo (pFRE = 0.007, ; pDUR = 0.004, ; pCON = 0.010, ; pVOW = 0.006, ). No treatment effect was observed for MG for both these deviants.

Also, for FRE, DUR, CON, and VOW deviants, significant group differences were observed only under the placebo condition where significant smaller MMN amplitudes were recorded for the LG in comparison to MG (pFRE < 0.001, ; pDUR < 0.001, ; pCON = 0.012, ; pVOW < 0.001, ) and HG (pFRE < 0.001, ; pDUR = 0.001, ; pCON < 0.001, ; pVOW < 0.001, ), and for the MG in comparison to the HG (pFRE < 0.001, ; pDUR = 0.001, ; pCON < 0.001, ; pVOW < 0.001, ).

CDP-choline/galantamine-based subgrouping

There were no significant findings when subgrouping was based on amplitude scores from the active CDP-choline/galantamine session (vs placebo).

CDP-choline/galantamine treatment effect correlations

Treatment-induced amplitude changes were negatively correlated with placebo amplitudes at Fz and for all MMN deviants, indicating that greater CDP-choline/galantamine-mediated amplitude increases were observed in individuals with lower MMN generation at baseline (placebo). The opposite effect was observed in individuals with higher MMN generation at baseline.

PANSS—speech-related MMN relationships

CON amplitude treatment change scores correlated with PANSS total score (Spearman’s rho = −0.447, p = 0.028), and PANSS total negativity subscale score (Spearman’s rho = −0.414, p = 0.044). VOW amplitude treatment change scores negatively correlated with PANSS total score (Spearman’s rho = −0.522, p = 0.009), and with PANSS general subscale score (Spearman’s rho = −0.475, p = 0.019). These CDP-choline/galantamine-related improvements of MMN amplitudes to CON and VOW deviants indicate that greater amplitude increases were observed in individuals who expressed higher PANSS negative, positive, and total scores (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Scattergrams of treatment effect (T × Δ) amplitudes (treatment—placebo) for consonant at Fz (a, b), and vowel at Fz (c, d) correlation with PANSS total, negative, and general scores.

Adverse events

Participants’ self-reports of adverse events on a checklist of symptoms experienced were not significantly different during CDP-choline/galantamine treatment sessions in comparison to placebo. There were no reports of severe symptoms throughout the study.

Vital signs

Measures of systolic and diastolic blood pressure were not statistically different during the CDP-choline/galantamine treatment sessions in comparison to placebo. On that same note, heart rate measures taken pre- and post-treatment administration were also not significantly different during CDP-choline/galantamine treatment sessions in comparison to placebo.

Discussion

Summary of findings

This is the first examination of the acute and combined treatment of CDP-choline/galantamine on measures of deviance detection in patients with SCZ. The treatment did not show any effects in the full sample group while individuals demonstrating low deviance detection levels at baseline best responded to the treatment with significant enhancement of MMN amplitudes to FRE, DUR, and VOW deviants. These promising preliminary findings in patients with SCZ suggest that modulation of the nicotinic cholinergic system, the α7 nAChR specifically, differentially impacts early auditory processing in SCZ and may have the potential to benefit selectively those with impaired measures of deviance detection.

CDP-choline/galantamine-mediated modulation of deviance detection in SCZ

CDP-choline/galantamine treatment significantly increased deviance detection in LG individuals following FRE, DUR, and VOW deviants. However, in HG individuals, this active treatment diminished deviance detection following FRE, DUR, CON, and VOW deviants.

In general, the differential (baseline-dependent) effect of this combined CDP-choline/galantamine treatment is in line with our pilot study in healthy participants where increased amplitudes were observed to VOW deviants (Choueiry et al., 2020). In comparison, 2000 mg of CDP-choline alone induced larger MMN amplitude to DUR deviants (Aidelabum et al., 2021), while our results demonstrated an increase with 500 mg of CDP-choline in combination with galantamine (16 mg). Considering these findings, it would be reasonable to suggest that the α7 nicotinic system in chronic SCZ is not permanently disabled due to the neurodevelopmental impact of the illness.

Furthermore, improved quality of life and cognitive status were associated with long-term (2 years) treatment with CDP-choline in ischemic stroke patients (Alvarez-Sabín et al., 2016) and the combination of nicotine and galantamine was recently shown to benefit working memory in healthy individuals (Hahn et al., 2019). Hence, these latest findings urge the need to evaluate the sensory/cognitive effects of this CDP-choline/galantamine treatment strategy and their relationship to functional outcome indicators. Given that these present findings were obtained with speech MMN, this latter thrust is important as phonological language processing affects educational and occupational function (Carrión et al., 2015; Dondé et al., 2019a; Friedman et al., 2012; Revheim et al., 2006, 2014). Additional studies with this combined treatment should examine effects on more subtle linguistic deviants (e.g., variations in emotional or attitudinal prosody) that are linked to psychosocial functioning impairments that are often prognostic in SCZ (Javitt and Sweet, 2015; Revheim et al., 2014).

Recent findings bring forth the implication of nAChRs in MMN generation, in addition to its well documented moderation by glutamate and NMDA receptors (Javitt, 1996; Kantrowitz et al., 2018; Swerdlow et al., 2016; Tikhonravov et al., 2008), and highlighting the involvement of α7 nAChRs specifically in the CA1 hippocampal region (known for its role in learning and memory) where α7 nAChRs exerted modulatory effects on NMDA receptors (Askew and Metherate, 2016; Bali et al., 2017, 2019) and learning mechanisms (Broide and Leslie, 1999; Kantrowitz, 2018). These findings suggest a potential role for both these receptor systems in alleviating sensory/cognitive impairments in SCZ and other mental health disorders (Yang et al., 2017).

Relationship to patient symptoms

MMN change scores (CDP-choline/galantamine—placebo) for CON, and VOW deviants differentially correlated with PANSS total, negative, and general scores, revealing that individuals expressing higher PANSS scores showed greater improvements in deviance detection. This is in line with previous correlations of positive, general psychosis, and the hallucinating item of the PANSS with smaller DUR deviant amplitudes at frontal sites in SCZ (Fisher et al., 2011), while DUR deviant latency measures correlated with PANSS negative and general scores (Fisher et al., 2012b). Also, an 8-week CDP-choline add-on treatment to risperidone resulted in improved negative symptoms (PANSS) in patients with SCZ (Ghajar et al., 2018). These findings indicate that improvement in deviance detection measures by synergistic cholinergic stimulation, is significant for individuals with severe clinical ratings.

Baseline-dependent treatment effects

Improved deviance detection in LG and worsening in HG SCZ individuals following CDP-choline/galantamine replicate our findings in healthy participants (Choueiry et al., 2020), and extend previous reports of enhanced deviance detection in LG individuals with CDP-choline alone in healthy (Knott et al., 2015a) and SCZ (Aidelbaum et al., 2021) and with nicotine (Knott et al., 2014b; Smith et al., 2015). Full group effects have been reported with nicotine in healthy (Dulude et al., 2010; Inami et al., 2005), ketamine-induced SCZ model (Mathalon et al., 2014), and psychiatric populations (Baldeweg et al., 2006; Fisher et al., 2012a; Martin et al., 2009). Interindividual differences observed in response to pharmacological treatments may be the results of several factors, including genetic mutations (SCZ is recognized as a multigenic disease), the use of certain neuroleptics (which have been associated with cognitive modulation), and smoking status (Gilbert and Gilbert, 1995; Kupferschmidt et al., 2010; Li et al., 2009; Perkins, 1995, 2009; Poltavski and Petros, 2005). However, our analyses indicate that LG, MG, and HG individuals did not statistically differ on the basis of medications affecting the cholinergic system (i.e., anticholinergic load) or on the chlorpromazine equivalent. Baseline deviance detection level should be considered when conducting future pilot pharmacological studies as these findings suggest that treatment change scores (treatment—placebo) portrayed an inverted-U-type treatment response. Targeted neural therapy in combination with the targeting of individual patients (expected to benefit and respond to the given treatment/therapy) was recently highlighted as a possible synergistic method toward the achievement of personalized therapy (Fisher and Salisbury, 2019).

Limitations

Multiple strengths characterize this study, including the double-blind and randomized treatment administration, counterbalanced, and a crossover repeated measures design. Also, the assessment of female and male smokers and non-smokers is reflective of the SCZ population and permits the scientific validity and generalizability of our findings. Our analyses comparing smokers to non-smokers revealed no significant smoking-group differences for MMN amplitudes and latencies, deviating from previous reports showing that α7 agonists have evidenced precognitive effects in studies assessing only non-smoking participants, while negative results are typically shown when the study sample includes only smokers or a mixture of smokers and non-smokers (Tregellas and Wylie, 2019).

The relatively small sample size in the stratified amplitude groups could have limited the statistical power. Furthermore, the baseline stratification was conducted using the placebo session, which was later used for statistical analyses. Our blinded crossover counterbalanced design (with half of the group starting with placebo, while the other half with the active treatment) might have reduced potential regression to the mean effect. However, it would be best to employ a separate baseline session in future studies to eliminate this problem when segregating the full sample into low, medium, and high groups. In addition, it’s important to highlight that MMN is a mature and stable ERP and the protocol design accounts for any elements that may contribute to mean regressions or potential flukes in ERP recording. Participants were asked to abstain from consuming any substances that may impact their performance (i.e., stimulants and illicit drugs), testing sessions were scheduled at the same time of day, and the examiner, protocol, and steps were the same for each session. An initial baseline session will allow for the predesignation of lower sensory processing baseline individuals most likely to benefit from this treatment approach and will prevent treatment administration to individuals with higher sensory processing levels. Patients with lower baseline deviance detection should also be prioritized as the inclusion of patients with more efficient or intact deviance processing might underpower the results (Cotter et al., 2019). Furthermore, our stratification strategy may help explain the failure for AVL-3288 (a selective α7 type 1 PAM, previously shown to ameliorate cognition) to enhance cognitive measures in SCZ, as this study selected individuals with higher cognitive processing levels at baseline (Gee et al., 2017; Kantrowitz et al., 2020).

This was a pilot study employing a single dose level of CDP-choline/galantamine to SCZ. The positive findings support further examinations that assess different combination dose levels in order to define a dose-response curve. Also, a recent assessment of long-term cognitive enhancement therapies in patients with Alzheimer’s Disease reported time-mediated increasing effect only when acetylcholine esterase inhibitor (donepezil, rivastigmine, or galantamine) was combined with CDP-choline (vs exclusive acetylcholine esterase inhibitor administration) (Gareri et al., 2017). While PAMs marketed for use in humans are limited, galantamine may be criticized in the context of this study as it is not selective to α7 nAChRs. However, CDP-choline activates several neurotransmitter systems via α7 nAChR downstream signaling and following CDP-choline metabolism into cytidine and choline, which then can produce betaine which in turn activates S-adenosyl-l-methionine production, which is a serotonin precursor (Adibhatla et al., 2001). The CDP-choline/galantamine treatment results in complex pharmacodynamics benefiting several neurotransmitter systems despite the selective nature of CDP-choline, and while this is discussed as a limiting factor for the specificity of the treatment, the most successful neuroleptics today have the ability to modulate several receptor systems (Bertrand and Terry, 2018).

Conclusion

Measures of auditory deviance detection were improved following the administration of an acute dose of CDP-choline/galantamine in a subpopulation of patients with SCZ expressing lower deviance detection levels at baseline. The effectiveness of this combined cholinergic treatment needs to be further examined in the broad spectrum of the SCZ disorder (including neuroleptic-naïve patients). Furthermore, before progressing to larger scale clinical trial, additional dosage trials for each and combined treatment need to be conducted in SCZ to determine the optimal dose ranges, and these studies need to examine relationships between MMN improvement and changes in behavioral measures of early auditory (e.g., TMT) and cognitive (e.g., MATRICS battery) processes.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported in part by a grant to VK from the University of Ottawa Medical Research Fund (UMRF) and a Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) to JC.

ORCID iDs: Joëlle Choueiry  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3305-1029

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3305-1029

Derek Fisher  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2366-8225

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2366-8225

Verner Knott  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4969-3819

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4969-3819

References

- Adibhatla RM, Hatcher JF, Dempsey RJ. (2001) Effects of citicoline on phospholipid and glutathione levels in transient cerebral ischemia. Stroke 32: 2376–2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler LE, Cawthra EM, Donovan KA, et al. (2005) Improved P50 auditory gating with ondansetron in medicated schizophrenia patients. Am J Psychiatry 162: 386–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler LE, Olincy A, Cawthra EM, et al. (2004) Varied effects of atypical neuroleptics on P50 auditory gating in schizophrenia patients. Am J Psychiatry 161: 1822–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed AO, Strauss GP, Buchanan RW, et al. (2018) Schizophrenia heterogeneity revisited: Clinical, cognitive, and psychosocial correlates of statistically-derived negative symptoms subgroups. J Psychiatr Res 97: 8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aidelbaum R, Labelle A, Choueiry J, et al. (2021) The acute dose and baseline amplitude-dependent effects of CDP-choline on deviance detection (MMN) in chronic schizophrenia: A pilot study. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 30: 235–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albus M. (2012) Clinical courses of schizophrenia. Pharmacopsychiatry 45: S31–S35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Sabín J, Santamarina E, Maisterra O, et al. (2016) Long-term treatment with citicoline prevents cognitive decline and predicts a better quality of life after a first ischemic stroke. Int J Mol Sci 17: 390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askew CE, Metherate R. (2016) Synaptic interactions and inhibitory regulation in auditory cortex. Biol Psychol 116: 4–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzopardi E, Typlt M, Jenkins B, et al. (2013) Sensorimotor gating and spatial learning in α7-nicotinic receptor knockout mice. Genes Brain Behav 12: 414–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldeweg T, Wong D, Stephan KE. (2006) Nicotinic modulation of human auditory sensory memory: Evidence from mismatch negativity potentials. Int J Psychophysiol 59: 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bali ZK, Nagy LV, Budai D, et al. (2019) Facilitation and inhibition of firing activity and N-methyl-D-aspartate-evoked responses of CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cells by alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor selective compounds in vivo. Sci Rep 9: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bali ZK, Nagy LV, Hernádi I. (2017) Alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors play a predominant role in the cholinergic potentiation of N-methyl-D-aspartate evoked firing responses of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. Front Cell Neurosci 11: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertelsen B, Oranje B, Melchior L, et al. (2015) Association study of CHRNA7 promoter variants with sensory and sensorimotor gating in schizophrenia patients and healthy controls: A Danish case-control study. NeuroMol Med 17: 423–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand D, Terry AV. (2018) The wonderland of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biochem Pharmacol 151: 214–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodatsch M, Ruhrmann S, Wagner M, et al. (2011) Prediction of psychosis by mismatch negativity. Biol Psychiatry 69: 959–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boustani M, Campbell N, Munger S, et al. (2008) Impact of anticholinergics on the aging brain: A review and practical application. Aging Health 4: 311–320. [Google Scholar]

- Braff DL. (2011) Gating in schizophrenia: From genes to cognition (to real world function?). Biol Psychiatry 69: 395–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broide RS, Leslie FM. (1999) The α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in neuronal plasticity. Mol Neurobiol 20: 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan RW, Conley RR, Dickinson D, et al. (2008) Galantamine for the treatment of cognitive impairments in people with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 165: 82–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler PD, Chen Y, Ford JM, et al. (2012) Perceptual measurement in schizophrenia: Promising electrophysiology and neuroimaging paradigms from CNTRICS. Schizophr Bull 2012: 81–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrión RE, Cornblatt BA, McLaughlin D, et al. (2015) Contributions of early cortical processing and reading ability to functional status in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. Schizophr Res 164: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew ML, Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, et al. (2008) Anticholinergic activity of 107 medications commonly used by older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 56: 1333–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choueiry J, Blais CM, Shah D, et al. (2019. a) Combining CDP-choline and galantamine, an optimized α7 nicotinic strategy, to ameliorate sensory gating to speech stimuli in schizophrenia. Int J Psychophysiol 145: 70–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choueiry J, Blais CM, Shah D, et al. (2019. b) Combining CDP-choline and galantamine: Effects of a selective α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist strategy on P50 sensory gating of speech sounds in healthy volunteers. J Psychopharmacol 33: 688–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choueiry J, Blais CM, Shah D, et al. (2020) CDP-choline and galantamine, a personalized α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor targeted treatment for the modulation of speech MMN indexed deviance detection in healthy volunteers: A pilot study. Psychopharmacology 237: 3665–3687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter J, Barnett JH, Granger K. (2019) The use of cognitive screening in pharmacotherapy trials for cognitive impairment associated with schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry 10: 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Court J, Spurden D, Lloyd S, et al. (1999) Neuronal nicotinic receptors in dementia with Lewy bodies and schizophrenia: Alpha-bungarotoxin and nicotine binding in the thalamus. J Neurochem 73: 1590–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de La Salle S, Shah D, Choueiry J, et al. (2019) NMDA receptor antagonist effects on speech-related mismatch negativity and its underlying oscillatory and source activity in healthy humans. Front Pharmacol 10: 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch SI, Rosse RB, Schwartz BL, et al. (2008. a) Effects of CDP-choline and the combination of CDP-choline and galantamine differ in an animal model of schizophrenia: Development of a selective alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist strategy. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 18: 147–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch SI, Schwartz BL, Schooler NR, et al. (2008. b) First administration of cytidine diphosphocholine and galantamine in schizophrenia: A sustained alpha7 nicotinic agonist strategy. Clin Neuropharmacol 31: 34–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch SI, Schwartz BL, Schooler NR, et al. (2013) Targeting alpha-7 nicotinic neurotransmission in schizophrenia: A novel agonist strategy. Schizophr Res 148: 138–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dondé C, Luck D, Grot S, et al. (2017) Tone-matching ability in patients with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 181: 94–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dondé C, Martínez A, Kantrowitz JT, et al. (2019. a) Bimodal distribution of tone-matching deficits indicates discrete pathophysiological entities within the syndrome of schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry 9: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dondé C, Silipo G, Dias EC, et al. (2019. b) Hierarchical deficits in auditory information processing in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 206: 135–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza MS, Markou A. (2012) Schizophrenia and tobacco smoking comorbidity: NAChR agonists in the treatment of schizophrenia-associated cognitive deficits. Neuropharmacology 62: 1564–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulude L, Labelle A, Knott VJ. (2010) Acute nicotine alteration of sensory memory impairment in smokers with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 30: 541–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlichman RS, Maxwell CR, Majumdar S, et al. (2008) Deviance-elicited changes in event-related potentials are attenuated by ketamine in mice. J Cogn Neurosci 20: 1403–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Karoui I, King JR, Sitt J, et al. (2015) Event-related potential, time-frequency, and functional connectivity facets of local and global auditory novelty processing: An intracranial study in humans. Cereb Cortex 25: 4203–4212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher D, Grant B, Smith D, et al. (2011) Effects of auditory hallucinations on the mismatch negativity (MMN) in schizophrenia as measured by a modified ‘optimal’ multi-feature paradigm. Int J Psychophysiol 81: 245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DJ, Grant B, Smith DM, et al. (2012. a) Nicotine and the hallucinating brain: Effects on mismatch negativity (MMN) in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 196: 181–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DJ, Labelle A, Knott VJ. (2012. b) Alterations of mismatch negativity (MMN) in schizophrenia patients with auditory hallucinations experiencing acute exacerbation of illness. Schizophr Res 139: 237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DJ, Salisbury DF. (2019) The neurophysiology of schizophrenia: Current update and future directions. Int J Psychophysiol 145: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis AM, Knott VJ, Labelle A, et al. (2020) Interaction of background noise and auditory hallucinations on phonemic mismatch negativity (MMN) and P3a processing in schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry 11: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman R, Hall M, Adler LE, et al. (1995) Evidence in postmortem brain tissue for decreased numbers of hippocampal nicotinic receptors in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 38: 22–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman T, Sehatpour P, Dias E, et al. (2012) Differential relationships of mismatch negativity and visual P1 deficits to premorbid characteristics and functional outcome in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 71: 521–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gareri P, Castagna A, Cotroneo AM, et al. (2017) The citicholinage study: Citicoline plus cholinesterase inhibitors in aged patients affected with Alzheimer’s disease study. J Alzheimers Dis 56: 557–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee KW, Olincy A, Kanner R, et al. (2017) First in human trial of a type I positive allosteric modulator of alpha7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: Pharmacokinetics, safety, and evidence for neurocognitive effect of AVL-3288. J Psychopharmacol 31: 434–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghajar A, Gholamian F, Tabatabei-Motlagh M, et al. (2018) Citicoline (CDP-choline) add-on therapy to risperidone for treatment of negative symptoms in patients with stable schizophrenia: A double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial. Hum Psychopharmacol 33: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DG, Gilbert BO. (1995) Personality, psychopathology, and nicotine response as mediators of the genetics of smoking. Behav Genet 25: 133–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton G, Coles MG, Donchin E. (1983) A new method for off-line removal of ocular artifact. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 55(4): 468–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Butler PD, Chen Y, et al. (2009) Perception measurement in clinical trials of schizophrenia: Promising paradigms from CNTRICS. Schizophr Bull 35: 163–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan ZZ, Zhang X, Ravid R, et al. (2000) Decreased protein levels of nicotinic receptor subunits in the hippocampus and temporal cortex of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem 74: 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn B, Shrieves ME, Olmstead CK, et al. (2019) Evidence for positive allosteric modulation of cognitive-enhancing effects of nicotine in healthy human subjects. Psychopharmacology 237: 219–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris EW, Ganong AH, Cotman CW. (1984) Long-term potentiation in the hippocampus involves activation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. Brain Res 323: 132–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K. (2015) Targeting of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the treatment of schizophrenia and the use of auditory sensory gating as a translational biomarker. Curr Pharm Des 21: 3797–3806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde M, Choueiry J, Smith D, et al. (2016) Cholinergic modulation of auditory P3 event-related potentials as indexed by CHRNA4 and CHRNA7 genotype variation in healthy volunteers. Neurosci Lett 623: 36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inami R, Kirino E, Inoue R, et al. (2005) Transdermal nicotine administration enhances automatic auditory processing reflected by mismatch negativity. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 80: 453–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt D. (1996) Role of cortical N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in auditory sensory memory and mismatch negativity generation: Implications for schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 11962–11967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC. (2000) Intracortical mechanisms of mismatch negativity dysfunction in schizophrenia. Audiol Neurootol 5: 207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC, Freedman R. (2015) Sensory processing dysfunction in the personal experience and neuronal machinery of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 172: 17–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC, Lee M, Kantrowitz JT, et al. (2018) Mismatch negativity as a biomarker of theta band oscillatory dysfunction in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 191: 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC, Sweet RA. (2015) Auditory dysfunction in schizophrenia: Integrating clinical and basic features. Nat Rev Neurosci 16: 535–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LA, Hills PJ, Dick KM, et al. (2016) Cognitive mechanisms associated with auditory sensory gating. Brain Cogn 102: 33–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce EM, Roiser JP. (2007) Cognitive heterogeneity in schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry 20: 268–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurcak V, Tsuzuki D, Dan I. (2007) 10/20, 10/10, and 10/5 systems revisited: Their validity as relative head-surface-based positioning systems. Neuroimage 34: 1600–1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantrowitz JT. (2018) N-Methyl-D-aspartate-type glutamate receptor modulators and related medications for the enhancement of auditory system plasticity in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 207: 70–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantrowitz JT, Epstein ML, Lee M, et al. (2018) Improvement in mismatch negativity generation during D-serine treatment in schizophrenia: Correlation with symptoms. Schizophr Res 191: 70–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantrowitz JT, Javitt DC, Freedman R, et al. (2020) Double blind, two dose, randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over clinical trial of the positive allosteric modulator at the alpha7 nicotinic cholinergic receptor AVL-3288 in schizophrenia patients. Neuropsychopharmacology 45: 1339–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. (1987) The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 13: 261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott V, De La Salle S, Choueiry J, et al. (2015. b) Neurocognitive effects of acute choline supplementation in low, medium and high performer healthy volunteers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 131: 119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott V, Impey D, Philippe T, et al. (2014. b) Modulation of auditory deviance detection by acute nicotine is baseline and deviant dependent in healthy nonsmokers: A mismatch negativity study. Hum Psychopharmacol 29: 446–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott VJ, De La Salle S, Smith D, et al. (2013) Baseline dependency of nicotine’s sensory gating actions: Similarities and differences in low, medium and high P50 suppressors. J Psychopharmacol 27: 790–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott VJ, Impey D, Choueiry J, et al. (2015. a) An acute dose, randomized trial of the effects of CDP-choline on mismatch negativity (MMN) in healthy volunteers stratified by deviance detection level. Neuropsychiatr Electrophysiol 1: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Knott VJ, Smith D, de La Salle S, et al. (2014. a) CDP-choline: Effects of the procholine supplement on sensory gating and executive function in healthy volunteers stratified for low, medium and high P50 suppression. J Psychopharmacol 28: 1095–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlhaas KL, Robb HM, Roderwald VA, et al. (2015) Nicotinic modulation of auditory evoked potential electroencephalography in a rodent neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia. Biochem Pharmacol 97: 482–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koola MM. (2018) Attenuated mismatch negativity in attenuated psychosis syndrome predicts psychosis: Can galantamine-memantine combination prevent psychosis? Mol Neuropsychiatry 4: 71–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiyama D, Thomas ML, Miyakoshi M, et al. (2021) Hierarchical pathways from sensory processing to cognitive, clinical, and functional impairments in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 47: 373–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupferschmidt DA, Funk D, Erb S, et al. (2010) Age-related effects of acute nicotine on behavioural and neuronal measures of anxiety. Behav Brain Res 213: 288–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard S, Freedman R. (2006) Genetics of chromosome 15q13-q14 in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 60: 115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S, Samara M, Heres S, et al. (2016) Dose equivalents for antipsychotic drugs: The DDD method. Schizophr Bull 42: S90–S94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis AS, van Schalkwyk GI, Bloch MH. (2017) Alpha-7 nicotinic agonists for cognitive deficits in neuropsychiatric disorders: A translational meta-analysis of rodent and human studies. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 75: 45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Mead A, Bevins RA. (2009) Individual differences in responses to nicotine: Tracking changes from adolescence to adulthood. Acta Pharmacol Sin 30: 868–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light G, Braff D. (2005) Mismatch negativity deficits are associated with poor functioning in schizophrenia patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackowick KM, Barr MS, Wing VC, et al. (2014) Neurocognitive endophenotypes in schizophrenia: Modulation by nicotinic receptor systems. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 52: 79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra AK. (2015) Dissecting the heterogeneity of treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 41: 1224–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LF, Davalos DB, Kisley MA. (2009) Nicotine enhances automatic temporal processing as measured by the mismatch negativity waveform. Nicotine Tob Res 11: 698–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathalon DH, Ahn KH, Perry EB, et al. (2014) Effects of nicotine on the neurophysiological and behavioral effects of ketamine in humans. Front Psychiatry 5: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medalia A, Saperstein AM, Qian M, et al. (2019) Impact of baseline early auditory processing on response to cognitive remediation for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 208: 397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näätänen R, Kähkönen S. (2009) Central auditory dysfunction in schizophrenia as revealed by the mismatch negativity (MMN) and its magnetic equivalent MMNm: A review. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 12: 125–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näätänen R, Pakarinen S, Rinne T, et al. (2004) The mismatch negativity (MMN): Towards the optimal paradigm. Clin Neurophysiol 115: 140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näätänen R, Todd J, Schall U. (2016) Mismatch negativity (MMN) as biomarker predicting psychosis in clinically at-risk individuals. Biol Psychol 116: 36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai T, Tada M, Kirihara K, et al. (2013) Mismatch negativity as a ‘translatable’ brain marker toward early intervention for psychosis: A review. Front Psychiatry 4: 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa ELM, Lasalde-Dominicci J. (2007) Cognitive deficits in schizophrenia: Focus on neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and smoking. Cell Mol Neurobiol 27: 609–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olincy A, Stevens KE. (2007) Treating schizophrenia symptoms with an α7 nicotinic agonist, from mice to men. Biochem Pharmacol 74: 1192–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakarinen S, Lovio R, Huotilainen M, et al. (2009) Fast multi-feature paradigm for recording several mismatch negativities (MMNs) to phonetic and acoustic changes in speech sounds. Biol Psychol 82: 219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez VB, Woods SW, Roach BJ, et al. (2014) Automatic auditory processing deficits in schizophrenia and clinical high-risk patients: Forecasting psychosis risk with mismatch negativity. Biol Psychiatry 75: 459–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA. (1995) Individual variability in responses to nicotine. Behav Genet 25: 119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA. (1999) Baseline-dependency of nicotine affects: A review. Behav Pharmacol 10: 597–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA. (2009) Sex differences in nicotine reinforcement and reward: Influences on the persistence of tobacco smoking. In: Bevins RA, Caggiuls AR. (eds) Motivational Impact of Nicotine and Its Role in Tobacco Use. New York, NY: Springer, pp. 143–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poltavski DV, Petros T. (2005) Effects of transdermal nicotine on prose memory and attention in smokers and nonsmokers. Physiol Behav 83: 833–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recio-Barbero M, Segarra R, Zabala A, et al. (2021) Cognitive enhancers in schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of alpha-7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists for cognitive deficits and negative symptoms. Front Psychiatry 12: 310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revheim N, Butler PD, Schechter I, et al. (2006) Reading impairment and visual processing deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 87: 238–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revheim N, Corcoran C, Dias E, et al. (2014) Reading deficits in schizophrenia and individuals at high clinical risk: Relation to sensory function, course of illness, and psychosocial outcome. Am J Psychiatry 171: 949–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosburg T, Kreitschmann-Andermahr H. (2016) The effects of ketamine on the mismatch negativity (MMN) in humans: A meta-analysis. Clin Neurophysiol 127: 1387–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosburg T, Trautner P, Dietl T, et al. (2005) Subdural recordings of the mismatch negativity (MMN) in patients with focal epilepsy. Brain 128: 819–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salahudeen MS, Hilmer SN, Nishtala PS. (2015) Comparison of anticholinergic risk scales and associations with adverse health outcomes in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 63: 85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Morla EM, Santos JL, Aparicio A, et al. (2009) Antipsychotic effects on auditory sensory gating in schizophrenia patients. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 19: 905–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton BE, Allen DN, Goldstein G, et al. (1999) Relations between cognitive and symptom profile heterogeneity in schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis 187: 414–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinkus ML, Graw S, Freedman R, et al. (2015) The human CHRNA7 and CHRFAM7A genes: A review of the genetics, regulation, and function. Neuropharmacology 96: 274–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DM, Fisher D, Blier P, et al. (2015) The separate and combined effects of monoamine oxidase A inhibition and nicotine on the mismatch negativity event related potential. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 137: 44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smucny J, Tregellas JR. (2017) Targeting neuronal dysfunction in schizophrenia with nicotine: Evidence from neurophysiology to neuroimaging. J Psychopharmacol 31: 801–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup TS. (2007) Heterogeneity of treatment effects in schizophrenia. Am J Med 120: S26–S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su L, Cai Y, Wang L, et al. (2012) Various effects of antipsychotics on p50 sensory gating in Chinese schizophrenia patients: A meta-analysis. Psychiatr Danub 24: 44–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Bhakta S, Chou HH, et al. (2016) Memantine effects on sensorimotor gating and mismatch negativity in patients with chronic psychosis. Neuropsychopharmacology 41: 419–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada M, Kirihara K, Mizutani S, et al. (2019) Mismatch negativity (MMN) as a tool for translational investigations into early psychosis: A review. Int J Psychophysiol 145: 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S. (2013) Heterogeneity of schizophrenia: Genetic and symptomatic factors. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 162: 648–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry AV, Callahan PM. (2020) α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as therapeutic targets in schizophrenia: Update on animal and clinical studies and strategies for the future. Neuropharmacology 170: 108053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas ML, Green MF, Hellemann G, et al. (2017) Modeling deficits fom early auditory information processing to psychosocial functioning in schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry 74: 37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonravov D, Neuvonen T, Pertovaara A, et al. (2008) Effects of an NMDA-receptor antagonist MK-801 on an MMN-like response recorded in anaesthetized rats. Brain Res 1203: 97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd J, Harms L, Schall U, et al. (2013) Mismatch negativity: Translating the potential. Front Psychiatry 4: 171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tregellas JR, Wylie KP. (2019) Alpha7 nicotinic receptors as therapeutic targets in schizophrenia. Nicotine Tob Res 21: 349–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbricht D, Krljesb S. (2005) Mismatch negativity in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 76: 1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace TL, Bertrand D. (2015) Neuronal α7 nicotinic receptors as a target for the treatment of schizophrenia. Int Rev Neurobiol 124: 79–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigström H, Gustafsson B. (1984) A possible correlate of the postsynaptic condition for long-lasting potentiation in the guinea pig hippocampus in vitro. Neurosci Lett 44: 327–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T, Xiao T, Sun Q, et al. (2017) The current agonists and positive allosteric modulators of α7 nAChR for CNS indications in clinical trials. Acta Pharm Sin B 7: 611–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JW, Geyer MA. (2013) Evaluating the role of the alpha-7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in the pathophysiology and treatment of schizophrenia. Biochem Pharmacol 86: 1122–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]