Abstract

Background

Gynecological cancers are the most lethal malignancies among females, most of which are associated with gene mutations. Few studies have compared the differences in the genomic landscape among various types of gynecological cancers. In this study, we evaluated the diversity of mutations in different gynecological cancers.

Methods

A total of 184 patients with gynecological cancer, including ovarian, cervical, fallopian tube, and endometrial cancer, were included. Next-generation sequencing was performed to detect the mutations and tumor mutational burden (TMB). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analyses were also conducted.

Results

We found that 94.57% of patients had at least one mutation, among which single nucleotide variants, insertions and InDels were in the majority. TP53, PIK3CA, PTEN, KRAS, BRCA1, BRCA2, ARID1A, KMT2C, FGFR2, and FGFR3 were the top 10 most frequently mutated genes. Patients with ovarian cancer tended to have higher frequencies of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, and the frequency of germline BRCA1 mutations (18/24, 75.00%) was higher than that of BRCA2 (11/19, 57.89%). A new mutation hotspot in BRCA2 (I770) was firstly discovered among Chinese patients with gynecological cancer. Patients with TP53, PIK3CA, PTEN, and FGFR3 mutations had significantly higher TMB values than those with wild-type genes. A significant cross was discovered between the enriched KEGG pathways of gynecological and breast cancers. GO enrichment revealed that the mutated genes were crucial for the cell cycle, neuronal apoptosis, and DNA repair.

Conclusion

Various gynecological cancer types share similarities and differences both in clinical characterization and genomic mutations. Taken together with the results of TMB and enriched pathways, this study provided useful information on the molecular mechanism underlying gynecological cancers and the development of targeted drugs and precision medicine.

Keywords: gynecological cancer, next-generation sequencing, TMB, BRCA1, BRCA2, FGFR3

1. Introduction

Ovarian (OC), cervical (CC), and endometrial cancer (EC) are the most common gynecological cancers in the female reproductive system (1, 2). OC is the most lethal gynecological malignancy in developed countries (3), with a 5-year survival rate of ~47% (4). Since ovaries are relatively small and located deep in the pelvic cavity, up to 59% of OCs are only detected at advanced stages, with a low survival rate (5). Epithelial ovarian carcinoma (EOC) accounts for the majority of OCs and can be divided into serous, endometrioid, clear cell, and mucinous carcinoma, amongst others. Serous carcinomas constitute about 75% of EOCs and are further divided into low-grade and high-grade serous carcinomas (LGSC and HGSC) depending on their histological differences (6). CC is the fourth most common cancer among females, affecting approximately 600,000 women annually (7). Although screening programs and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines have helped reduce its incidence (8), approximately 310,000 patients with CC die annually (9). CC tends to develop at a younger age (10, 11); however, older patients also often have dismal prognoses (12, 13). EC, which is second only to CC in terms of the incidence of reproductive system cancers, ranks seventh among the most prevalent malignancies among females (14–16). EC can be divided into two types: type I estrogen-dependent EC (EEC) and type II non-estrogen-dependent EC (NEEC) (17). The proportion of patients with EEC is higher, and they are often younger and present with hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and infertility (18). NEEC has higher rates of metastasis and recurrence, poorer prognoses, and is more common among older women (19, 20). Fallopian tube cancer (FTC), which originates in the salpingeal mucosa (21), exhibits clinical behaviors similar to that of OC (22). But mutated fallopian tube epithelial cells were reported to form malignant tumors with a shorter latency and higher penetrance than that of ovarian surface epithelium. Although FTC is a relatively rare gynecological cancer, its incidence increased 4.19-fold from 2001 to 2014 (23).

Cancers are genetic diseases. Gene mutations alter the structure or function of related and encoded proteins, resulting in excessive/persistent stimulation signals for cell growth and transformation. With the development of molecular biology, the use of genetic testing to determine mutations in related tumors has become a topic of interest. Targeted drugs for specific genes and mutations are effective ways to treat cancer. Approximately 10 to 15% of OC are reported to be hereditary, and patients with OC are carriers of germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 (24). BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations increase the lifetime risk of peritoneal malignancies and FTC (25, 26). In 2014, olaparib, the first poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitor, was approved for the treatment of BRCA-mutated OC (27). PPP2R1A and TP53 mutations are dramatically higher in patients with advanced-stage EC (19). PIK3CA, KMT2C, and KMT2D are the most frequently mutated genes in CC (28).

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is a high-throughput sequencing technology that plays a vital role in cancer research (29). NGS can identify genomic alterations occurring in any region of a target gene, detect one mutated copy among thousands of wild-type copies, and elucidate many types of mutational landscapes of tumors. NGS has become an important aspect of accurate tumor diagnosis and treatment and has a variety of uses, such as tumor-targeted therapy-related driver gene detection, analysis of drug resistance mechanisms, tumor metastasis and prognosis assessment, and molecular diagnostics. In this study, we investigated 184 patients with gynecological malignancies using NGS and created a genomic landscape to show the diversity among different gynecological cancers, providing useful information for future clinical treatment.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients and sampling

A total of 184 patients diagnosed with gynecological cancers at Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine between January 2020 and June 2022 were enrolled in this study. All included patients gave their informed consent. The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee of the Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine. Tissue samples were collected during surgical procedures and were subjected to NGS alongside paired blood samples. Patient information was acquired from medical records. Pathology diagnosis including the tumor site, pathological type, tumor differentiation grade, as well as Federation of International of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (FIGO) grade, were reviewed by two expert pathologists from the pathology department.

2.2. DNA extraction

Imprint cytology was performed to evaluate tumor purity before DNA extraction. Briefly, freshly cut surfaces of tissue specimens were gently pressed to glass slides. Then the slides was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) after fixing with 95% of ethyl alcohol for 5–6 s. If the percentage of tumor cells was higher than 15%, the specimen was considered qualified for subsequent extraction and sequencing. Genomic DNA was extracted from fresh tumor tissue using the TIANamp Genomic DNA Kit (TIANGEN, China). Genomic DNA from peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) was extracted using a TGuide S32 Magnetic Blood Genomic DNA Kit (TIANGEN, China). The concentration of DNA was measured using a Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher, USA), whereas the DNA quality was assessed using an Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer (Agilent, USA). All extractions and assays were conducted according to the manufacturers’ instructions supplied in the respective kits used in this study.

2.3. Library preparation and sequencing

Genomic DNA extracted from each tumor or PBL sample was sheared with Covaris LE220 to a length of 200 bp, and fragmented DNA was used to construct a library using the KAPA Hyper Preparation Kit (Kapa Biosystems, USA). Target regions were captured using the HyperCap Target Enrichment Kit (Roche, Switzerland). The customized panel used in the capture process includes 543 genes (30), which are tumor-related major genes, and spans around a 1.67 MB genomic region of the human genome ( Supplemental Table 1 ; Genecast Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Bioinformatic analyses of these 543 genes were carried out at a College of American Pathologists (CAP)-certified laboratory (Genecast Biotechnology). Hybridization and washing were conducted according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The captured library was sequenced on the instrument of Illumina Novaseq 6000, which produces paired-end reads with the length of each end as 150bp, according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Clean sequenced reads were mapped to the human reference genome (hg19) using BWA (v0.7.17) (31). VarDict (version 1.5.1) was used to call single nucleotide variant (SNV) mutations (32), whereas compound heterozygous mutations were merged using FreeBayes (version 1.2.0) (33). After annotation using ANNOVAR (2015 Jun17) (34), somatic mutations were selected based on the following standards: (i) located in intergenic/intronic regions; (ii) synonymous SNVs; (iii) allele frequency ≥ 0.002 in Exome Aggregation Consortum (ExAC) and genome aggregation database (gnomAD) (35, 36); (iv) allele frequency <0.05 in the tumor sample/allele frequency <0.01 in the plasma sample; (v) strand bias mutations in the reads; (vi) support reads <5; (vii) depth <30.

2.4. Tumor mutational burden calculation

Primarily, dynamic nonsynonymous mutations in the coding regions were selected for the following analysis of TMB, while driver gene mutations and germline alterations in the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism database (dbSNP) were removed. We filtered SNV mutations in all samples according to the following rules: (i) not splicing or exonic; (ii) depth <100 X/allele frequency <0.05; (iii) allele frequency ≥ 0.002 in the ExAC and gnomAD; and (iv) strand bias mutations in the reads. After quantification of the number of somatic nonsynonymous SNVs, the value was extrapolated to the whole exome using a validated algorithm (37). TMB, measured in mutations per Mb, was then calculated after obtaining absolute mutation counts against the mutation spots of the normal samples using the following formula:

2.5. Gene ontology and Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes pathway enrichment analyses

GO functional enrichment and KEGG pathway analyses were performed using DAVID tools (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/). For GO analysis, contigs were categorized, and their molecular functions, cellular components, and biological processes were statistically analyzed.

2.6. Protein interaction

Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING, version 11.0, https://string‐db.org) was used to analyze functional interactions with a confidence of 0.7. “Ovarian cancer,” “cervical cancer,” “fallopian tube cancer,” and “endometrial cancer” were used as keywords in Chilibot (http://www.chilibot.net/) to analyze the interaction between genes and different gynecological cancers, excluding abstract co-occurrence relationships.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented as the median (interquartile range; IQR) for continuous variables, and as numbers (percentages) for categorical data. All data were analyzed using SPSS version 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric tests were conducted for comparisons between groups. Pearson’s Chi-square test was used for categorical variables. The Benjamini–Hochberg procedure was conducted to derive significance for enrichment tests. Spearman’s correlation coefficients with a two-tailed p value were determined for correlation analyses; p < 0.05 indicated significance. Data are visualized in graphs produced using GraphPad Prism version 8.0 and R software version 4.0.5.

3. Results

3.1. The clinical features of the analyzed cohort

Among the 184 patients, 140 had OC, 12 had CC, 8 had FTC, and 24 had EC. Clinicopathological characteristics are presented in Table 1 . The median age at diagnosis was 60 (50–67) years old.

Table 1.

Clinical characterization of the population in this study.

| OC | CC | FTC | EC | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 140) | (n = 12) | (n = 8) | (n = 24) | ||

| Age at diagnosis | p=0.008 | ||||

| Median | 61 (51-67) | 48 (39-60) | 67 (61-70) | 57 (46-63) | |

| ≥ 55 years | 91 (65.00%) | 3 (25.00%) | 7 (87.50%) | 14 (58.33%) | |

| Menopausal status | p=0.206 | ||||

| Pre-menopausal | 35 (25.00%) | 5 (41.67%) | 0 (0.00%) | 7 (29.17%) | |

| Post-menopausal | 105 (75.00%) | 7 (58.33%) | 8 (100.00%) | 17 (70.83%) | |

| Tumor size | p=0.01 | ||||

| Median | 5.0 (2.5-8.5) | 3.1 (1.6-4.8) | 3.4 (1.5-4.4) | 4.0 (2.0-5.9) | |

| ≥5 cm | 75 (53.57%) | 3 (25.00%) | 1 (12.50%) | 8 (33.33%) | |

| Metastasis | p=0.027 | ||||

| Node | 23 (16.43%) | 1 (8.33%) | 0 (0.00%) | 4 (16.67%) | |

| Organ | 9 (6.43%) | 2 (16.67%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (4.17%) | |

| Both | 73 (51.14%) | 4 (33.33%) | 8 (100.00%) | 7 (29.17%) | |

| None | 35 (25.00%) | 5 (41.67%) | 0 (0.00%) | 12 (50.00%) | |

| FIGO stage | p=0.000 | ||||

| I-II | 39 (27.86%) | 9 (75.00%) | 3 (37.50%) | 16 (66.67%) | |

| III-IV | 101 (71.14%) | 3 (25.00%) | 5 (62.50%) | 8 (33.33%) | |

| Personal history | |||||

| Breast cancer | 8 (5.71%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | |

| Thyroid cancer | 2 (1.43%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | |

| Hematologic tumor | 2 (1.43%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | |

| Renal cancer | 1 (0.71%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | |

| Liver cancer | 1 (0.71%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | |

| Colon cancer | 1 (0.71%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | |

| Family history | |||||

| Thyroid cancer | 1 (0.71%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | |

| Lung cancer | 1 (0.71%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | |

OC, ovarian cancer; CC, cervical cancer; EC, endometrial cancer; FTC, fallopian tube cancer; FIGO, Federation of International of Gynecologists and Obstetricians.

Patients with CC were younger at diagnosis, especially compared with those with OC and FTC. No significant differences were observed in menopausal status. Patients with OC had larger tumors, found at more advanced stages, while patients with CC and EC were diagnosed at earlier stages (p < 0.05). Metastasis occurred at both at node and organs in all patients with FTC. Patients with OC tended to have personal/family histories of cancer, especially breast cancer. Further analysis was performed among patients with OC according to their pathological types ( Supplementary Table 2 ).

3.2. Gynecological cancers exhibit various genomic landscapes

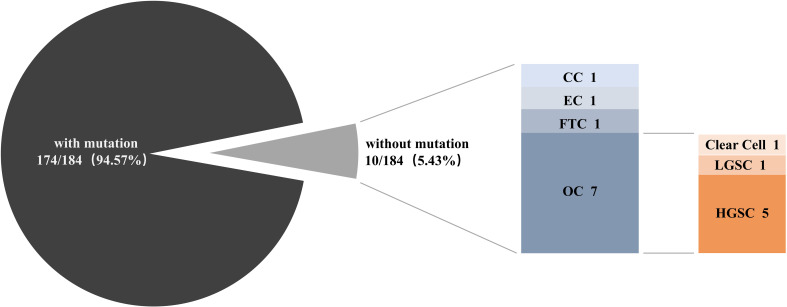

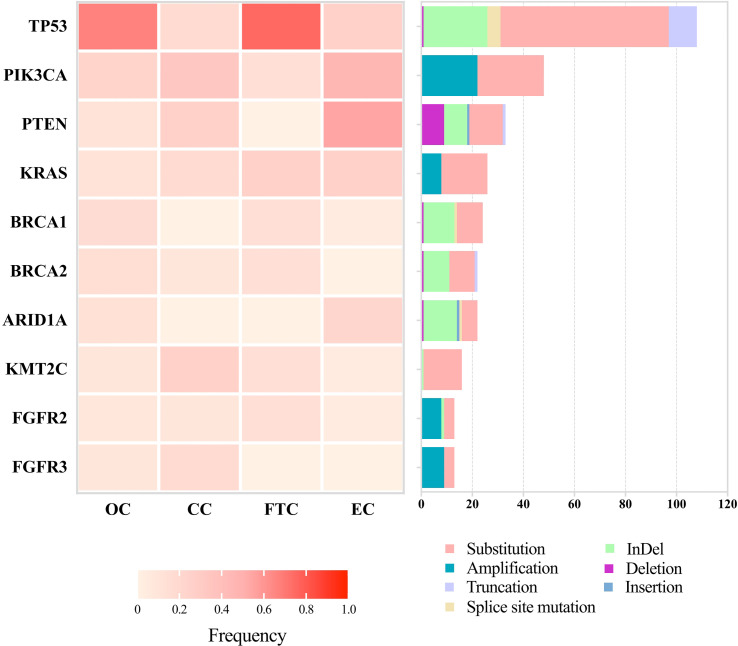

Patient DNA from tumor tissues and matched peripheral blood were used for NGS. We detected 529 SNVs, 132 insertions and InDels, 36 truncations, 111 gene amplifications, 36 gene deletions, and 17 splice site mutations. Of all our patients, 94.57% (174/184) had at least one mutation ( Figure 1 ). The top 10 most frequently altered genes in patients with gynecological cancer are presented in Figure 2 . Patients with OC and FTC had higher frequencies of TP53 mutations, while patients with EC showed more PTEN alterations. Changes in KMT2C and FGFR3 were more frequent among patients with CC than in the other three types.

Figure 1.

The proportion of patients with and without mutations. Next-generation sequencing was performed among 184 gynecological cancer patients to detect genomic alterations. OC, ovarian cancer; CC, cervical cancer; EC, endometrial cancer; FTC, fallopian tube cancer; LGSC, low-grade serous cancer; HGSC, high-grade serous cancer.

Figure 2.

Landscapes of the top 10 most frequently mutated genes among 184 patients with gynecological cancer. Next-generation sequencing was performed to detect mutations. Frequencies of mutated genes are listed on the left, and mutation types are shown on the right, with annotation bars at the bottom. OC, ovarian cancer; CC, cervical cancer; EC, endometrial cancer; FTC, fallopian tube cancer.

Furthermore, different mutation types were uncovered among different genes. TP53 showed obvious alterations in SNVs and InDels. PIK3CA and PTEN revealed higher frequencies of copy number variations. BRCA1 and BRCA2 had similar patterns with slight differences, such as splice site mutations in BRCA1 and insertions in BRCA2. R273 and V173 in TP53, H1047 and E542 in PIK3CA, R183 in PPP2R1A, and G12 in KRAS were hotspots of mutations among these patients (data not shown). The top 10 most frequently altered genes among patients with OC were the same as those in all 184 patients, but in an order with slight changes ( Supplementary Figure 1 ).

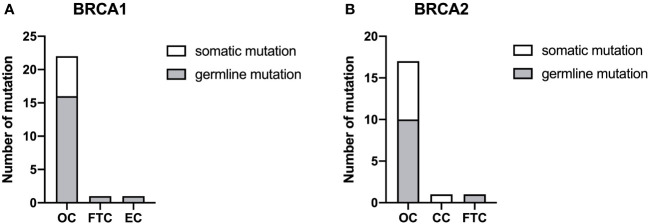

3.3. Analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations

In total, 24 and 19 mutations were discovered in BRCA1 and BRCA2, respectively, most of which were found in patients with OC ( Figure 3 ). Two patients with OC (HGSC and endometrioid carcinoma, respectively) carried both BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations simultaneously. No BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations were found in patients with CC. The proportion of germline mutations was higher than somatic mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Moreover, the frequency of germline BRCA1 mutations (18/24, 75.00%) was higher than that of BRCA2 mutations (11/19, 57.89%). HGSC accounted for the majority of germline mutations in both BRCA1 and BRCA2 in patients with OC ( Supplementary Figure 2 ). BRCA2 mutation c.2307delT p.I770Ffs*2 was the hotspot firstly reported here among Chinese patients with gynecological cancer.

Figure 3.

The proportion of BRCA1 (A) and BRCA2 (B) mutations. Somatic and germline mutations were respectively detected by next-generation sequencing among the different types of gynecological cancer. OC, ovarian cancer; CC, cervical cancer; EC, endometrial cancer; FTC, fallopian tube cancer.

3.4. TMB analysis

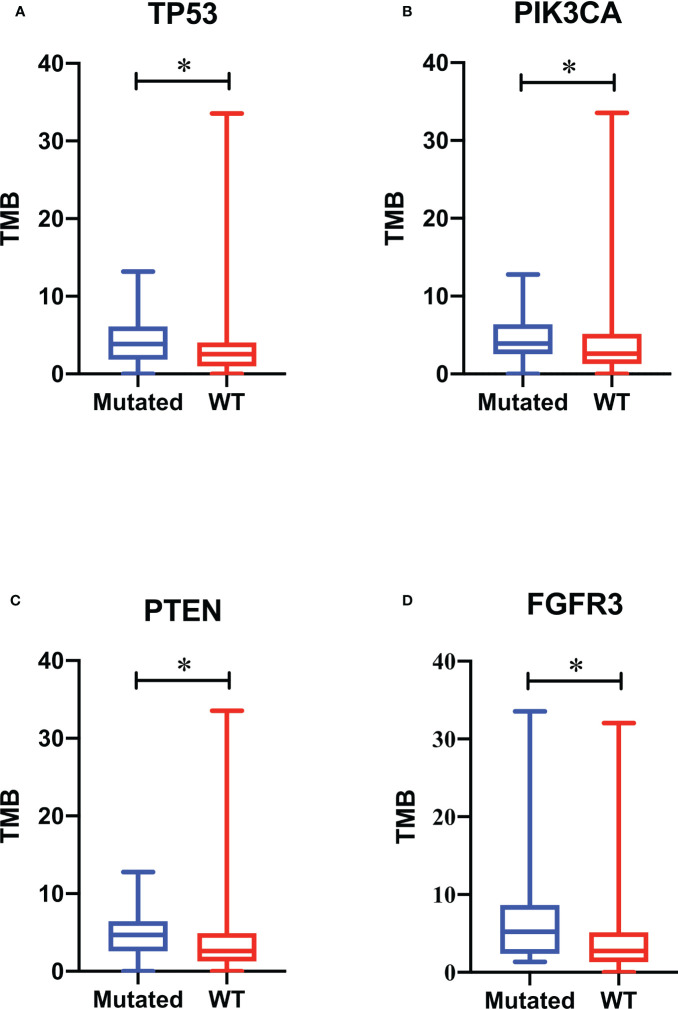

TMB range in this study spanned 0 to 192.35. To improve the accuracy, the data from one patient with endometrioid OC with statistical outliers (TMB = 192.35) was removed. The median TMB for all remaining patients was 2.94 (1.34–5.17). We ranked the TMB values from the lowest to highest and classified them into low, moderate, and high categories using quantiles ≤ 25%, 25–75%, and ≥75%, respectively. The ratio for TMB-low, TMB-moderate, and TMB-high was 32.79% (60/183), 54.64% (100/183), and 12.57% (23/183), respectively. No difference was observed between the median of the four gynecological cancer types (p = 0.200, Table 2 ); however, patients with EC tended to have a higher ratio of TMB-high values. Further analysis of TMB among patients with OC is shown in Supplementary Table 3 . No correlation was observed between TMB and age, tumor size, menopausal status, metastasis, or FIGO stage (data not shown). Further, we analyzed the association between TMB and the top 10 most frequently changed genes in Figure 2 . Compared with the wild-type, significant differences were discovered in the median of TMBs among patients with TP53, PIK3CA, PTEN, and FGFR3 mutations (p < 0.05, Figure 4 ).

Table 2.

Tumor mutational burden of the population in this study.

| OC | CC | FTC | EC | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 139) | (n = 12) | (n = 8) | (n = 24) | ||

| Median | 2.94 (1.30-5.17) | 2.10 (0.00-6.02) | 2.76 (1.91-4.19) | 3.85 (2.56-7.44) | p=0.200 |

| Low | 50 (35.97%) | 6 (50.00%) | 2 (25.00%) | 2 (8.33%) | |

| Moderate | 74 (53.24%) | 4 (33.33%) | 6 (75.00%) | 16 (66.67%) | |

| High | 15 (10.79%) | 2 (16.67%) | 0 (0.00%) | 6 (25.00%) |

OC, ovarian cancer; CC, cervical cancer; EC, endometrial cancer; FTC, fallopian tube cancer.

Figure 4.

Association of gene mutations with tumor mutational burden (TMB). TMB values of patients with TP53 (A), PIK3CA (B), PTEN (C), and FGFR3 (D) mutations are respectively compared with those of patients with wild-type genes. A box plot was used to show the minimum, maximum, median, and interquartile range of the TMB values. The blue box represents patients with mutations, and the red box represents patients with wild-type genes. * p < 0.05.

3.5. Enrichment analysis and protein interaction

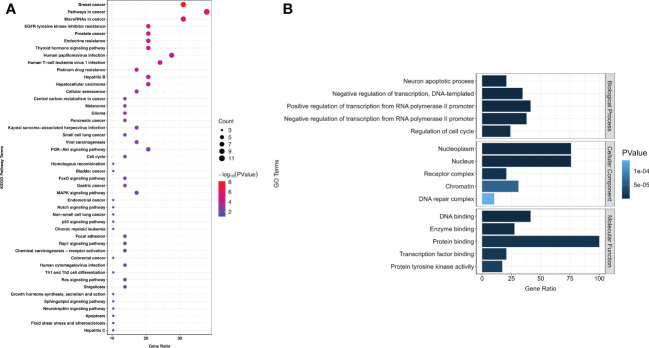

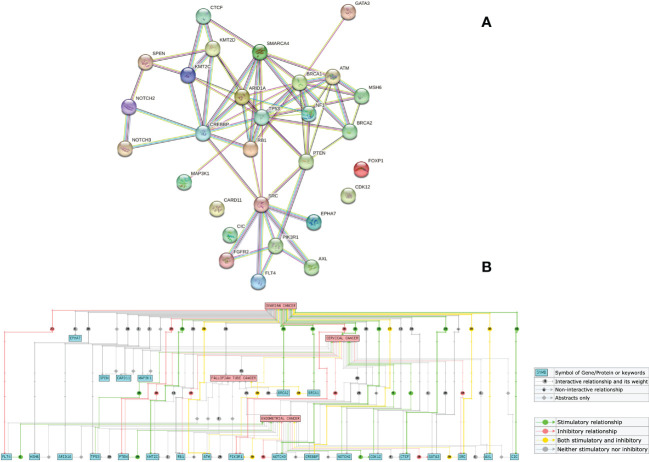

In this cohort, 529 SNVs and 132 insertions and InDels were detected, which accounted for the majority of mutations (661/861, 76.77%). Therefore, we performed an overlap analysis of the SNVs- and insertions and InDels-associated 29 genes. The KEGG and GO analyses of these genes are shown in Figure 5 . A significant cross was discovered between the enriched pathways of gynecological and breast cancers ( Figure 5A ). Enrichment also revealed potential resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors, endocrine, and platinum drugs. The top five enriched GO terms in biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions are listed according to their p values ( Figure 5B ). Results showed that the mutated genes were crucial for neuronal apoptosis and DNA repair, as well as normal cell cycle. Protein interaction analysis identified TP53 as a crucial protein in the network ( Figure 6A ). SRC, RB1, CREBBP, ARID1A, SMARCA4, BRCA1, and ATM also contributed significantly to the interaction net. Chilibot analysis showed that most of these mutated genes had stimulatory or inhibitory relationships with different gynecological cancers ( Figure 6B ).

Figure 5.

KEGG (A) and GO (B) enrichment among 184 patients with gynecological cancer. Next-generation sequencing was performed to detect mutations. Overlap of SNVs- and insertions and InDels-associated 29 genes was conducted for KEGG and GO enrichment. The size of each dot in KEGG enrichment indicates the number of genes included. The bigger the dot, the more genes are involved in the pathway. The top five GO enrichments are listed according to their p values.

Figure 6.

Interaction between mutated genes. Overlap analysis of SNVs- and insertions and InDels-associated 29 genes were performed on STRING (A) and Chilibot (B). A confidence of 0.7 was used to analyze functional interactions on the STRING website. “Ovarian cancer”, “cervical cancer”, “fallopian tube cancer”, and “endometrial cancer” were used as keywords on Chilibot to analyze the interaction between genes and different gynecological cancers, excluding abstract co-occurrence relationships.

4. Discussion

Gynecological cancers are among the most common malignancies with significant morbidity and mortality, primarily classified into five major types according to the organ affected (38, 39). In this retrospective study, we investigated 184 Chinese patients with gynecological cancer using NGS. Patients with OC, CC, EC, and FTC shared similarities but also varied both in clinical characterization and genomic landscape. It is worth noting that our research also has some limitations. Firstly, consistent with their clinical incidence, the numbers of patients with CC, EC, and FTC were limited in this study. Therefore, the relevant statistical results among patients with OC were more informative. Secondly, no overall survival data are provided at this time since the most recent patient enrolled was in June 2022. Therefore, this study may provide preliminary information for the clinical features and mutations of different types of gynecological tumors, and offer new ideas for future clinical treatment and targeted drug development.

It was reported that women with hereditary breast cancer have a 30–50% chance of developing OC (40). All the patients with a family and personal history of cancer in this study were diagnosed with OC, especially those with breast cancer. Our KEGG enrichment results also showed a significant cross between gynecological cancers and breast cancer ( Figure 5A ). Therefore, for persons with family history, especially with breast cancer history, it is crucial they undergo gynecological tumor gene screening as early as possible.

NGS technology gives us an opportunity to rapidly sequence multiple genes simultaneously and discover relevant mutations to guide treatment, which is beneficial in the field of precision or personalized medicine (41). TP53, the most frequently mutated gene in OC and FTC in our study ( Figure 2 ), was reported in 1979 as the earliest gene to be associated with gynecological cancer (42). Consistently, an analysis from The Cancer Genome Atlas demonstrated that 96% HGSC was characterized by TP53 mutation (43). KMT2C and FGFR3 mutations had higher frequencies among the patients with CC in our study ( Figure 2 ), of which FGFR3-TACC3 fusion was recently reported to be a potential molecular mechanism for inducing small cell cervical carcinoma (44). PTEN overexpression was suggested to promote morular differentiation in EC (45), but our results showed that PTEN deletion also played an important role ( Figure 2 ). SNV was the most common mutation in our study, followed by insertions and InDels. A combination of these mutation-associated genes and the top 10 most frequent mutations will constitute the potential multi-gene panel to screen gynecological cancers.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations are related to the DNA double-strand break repair process, which is also demonstrated in the GO enrichment result ( Figure 5B ). The process will not proceed normally when these two genes mutate, and the upstream codon will be converted to a stop codon and thus affect the protein formation (40). BRCA gene mutations are also indicators for PARP inhibitor (43, 46) and chemotherapy treatment (47). To the best of our knowledge, the mutation hotspot in BRCA2 (I770) discovered in our study is the first reported among Chinese patients with gynecological cancer (48–50). Patients with BRCA2 mutations have a better prognosis than those with BRCA1 mutations (51).

Comprehensive understanding of factors associated with genomic instability is crucial for improving our knowledge of carcinogenesis. TMB is defined as the total number of somatic coding mutations, base substitutions, and insertion–deletion errors per million bases (52). Recently, researchers have identified the crucial role of TMB in response to immunotherapy and patient prognosis (53, 54). Higher TMB is associated with higher-grade, advanced clinical stage, and immunosuppressive phenotypes (55). According to our results, patients with EC ( Table 2 ) and mucinous carcinoma ( Supplementary Table 3 ) tended to have a higher ratio of TMB-high values. Zhu et al. also documented that the TMB of mucinous tumors in their study was higher than that of HGSC and LGSC (56). However, limited by the sample sizes in our study, more patient data in a larger cohort will be collected to verify this conclusion. A TMB value ≥75% level is usually defined as TMB-high (57), and there were 23 (12.57%) patients with TMB-high in this study. Pre-menopause was found to contribute significantly to higher TMB values among these 23 patients (p < 0.05, data not shown). Genomic alterations are also documented to be associated with TMB. In this study, besides the most frequently altered genes TP53, PKI3CA, and PTEN, patients with FGFR3 mutations also tended to have higher TMB values than those with wild-type genes ( Figure 4 ). Erdafitinib has been approved for patients with urothelial carcinomas with select FGFR3 mutations (58). Therefore, FGFR3 may also become a potential target for patients with gynecological cancers.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our study elucidated the distinct genomic landscapes of various types of gynecological cancers. Taken together with the results of TMB and enriched pathways, this study preliminarily sheds light on the molecular mechanisms of gynecological cancers, and the information gained may contribute to the development of targeted drugs and clinical treatment in precision medicine. Further large-scale and multi-center studies will be performed to validate our findings.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material . Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of the Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

CJ and LL contributed to study conception and design. HL and WF performed surgeries and enrollment of patients. CJ and YL conducted patient recruitment, data collection and sequencing. ZP and GC performed bioinformatics analysis. CJ and YL drafted the manuscript. WF and LL revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients who gave their consent to present data in this study, as well as the investigators and research staff.

Funding Statement

The study is supported by Shanghai “Rising Stars of Medical Talents” youth clinical laboratory practitioner program (SHWRS(2020)_87).

Conflict of interest

ZP is an employee of Genecast Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Wuxi, China.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2023.1143876/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1. Wang N, Yang Y, Jin D, Zhang Z, Shen K, Yang J, et al. PARP inhibitor resistance in breast and gynecological cancer: Resistance mechanisms and combination therapy strategies. Front Pharmacol (2022) 13:967633. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.967633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Suszynska M, Klonowska K, Jasinska AJ, Kozlowski P. Large-Scale meta-analysis of mutations identified in panels of breast/ovarian cancer-related genes - providing evidence of cancer predisposition genes. Gynecol Oncol (2019) 153(2):452–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Caro AA, Deschoemaeker S, Allonsius L, Coosemans A, Laoui D. Dendritic cell vaccines: A promising approach in the fight against ovarian cancer. Cancers (Basel) (2022) 14(16):4037. doi: 10.3390/cancers14164037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chelariu-Raicu A, Coleman RL. Breast cancer (BRCA) gene testing in ovarian cancer. Chin Clin Oncol (2020) 9(5):63. doi: 10.21037/cco-20-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. American Cancer Society- Cancer Facts and Figures . (2019). Available at: https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2019.html.

- 6. Lalwani N, Prasad SR, Vikram R, Shanbhogue AK, Huettner PC, Fasih N. Histologic, molecular, and cytogenetic features of ovarian cancers: Implications for diagnosis and treatment. Radiographics (2011) 31(3):625–46. doi: 10.1148/rg.313105066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin (2022) 72(1):7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wen H, Guo QH, Zhou XL, Wu XH, Li J. Genomic profiling of Chinese cervical cancer patients reveals prevalence of DNA damage repair gene alterations and related hypoxia feature. Front Oncol (2022) 11:792003. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.792003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maluf FC, Dal Molin GZ, de Melo AC, Paulino E, Racy D, Ferrigno R, et al. Recommendations for the prevention, screening, diagnosis, staging, and management of cervical cancer in areas with limited resources: Report from the international gynecological cancer society consensus meeting. Front Oncol (2022) 12:928560. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.928560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin (2021) 71(1):7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fidler MM, Gupta S, Soerjomataram I, Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality among young adults aged 20-39 years worldwide in 2012: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol (2017) 18(12):1579–89. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30677-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cohen PA, Jhingran A, Oaknin A, Denny L. Cervical cancer. Lancet (2019) 393(10167):169–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32470-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Davies-Oliveira JC, Round T, Crosbie EJ. Cervical screening: The evolving landscape. Br J Gen Pract (2022) 72(721):364–65. doi: 10.3399/bjgp22X720197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li Y, Feng J, Zhao C, Meng L, Shi S, Liu K, et al. A new strategy in molecular typing: the accuracy of an NGS panel for the molecular classification of endometrial cancers. Ann Transl Med (2022) 10(16):870. doi: 10.21037/atm-22-3446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin (2021) 71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kasius JC, Pijnenborg JMA, Lindemann K, Forsse D, van Zwol J, Kristensen GB, et al. Risk stratification of endometrial cancer patients: FIGO stage, biomarkers and molecular classification. Cancers (Basel) (2021) 13:5848. doi: 10.3390/cancers13225848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Urick ME, Bell DW. Clinical actionability of molecular targets in endometrial cancer. Nat Rev Cancer (2019) 19:510–21. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0177-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Clarfield L, Diamond L, Jacobson M. Risk-reducing options for high-grade serous gynecologic malignancy in BRCA1/2. Curr Oncol (2022) 29(3):2132–40. doi: 10.3390/curroncol29030172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hong JH, Cho HW, Ouh YT, Lee JK, Chun Y, Gim JA. Genomic landscape of advanced endometrial cancer analyzed by targeted next-generation sequencing and the cancer genome atlas (TCGA) dataset. J Gynecol Oncol (2022) 33(3):e29. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2022.33.e29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Feng W, Jia N, Jiao H, Chen J, Chen Y, Zhang Y, et al. Circulating tumor DNA as a prognostic marker in high-risk endometrial cancer. J Transl Med (2021) 19(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s12967-021-02722-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stasenko M, Fillipova O, Tew WP. Fallopian tube carcinoma. J Oncol Pract (2019) 15(7):375–82. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maeda M, Hisa T, Matsuzaki S, Ohe S, Nagata S, Lee M, et al. Primary fallopian tube carcinoma presenting with a massive inguinal tumor: A case report and literature review. Medicina (Kaunas) (2022) 58(5):581. doi: 10.3390/medicina58050581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lõhmussaar K, Kopper O, Korving J, Begthel H, Vreuls CPH, van Es JH, et al. Assessing the origin of high-grade serous ovarian cancer using CRISPR-modification of mouse organoids. Nat Commun (2020) 11(1):2660. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16432-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liao CI, Chow S, Chen LM, Kapp DS, Mann A, Chan JK. Trends in the incidence of serous fallopian tube, ovarian, and peritoneal cancer in the US. Gynecol Oncol (2018) 149(2):318–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Choi MC, Bae JS, Jung SG, Park H, Joo WD, Song SH, et al. Prevalence of germline BRCA mutations among women with carcinoma of the peritoneum or fallopian tube. J Gynecol Oncol (2018) 29(4):e43. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2018.29.e43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shah S, Cheung A, Kutka M, Sheriff M, Boussios S. Epithelial ovarian cancer: Providing evidence of predisposition genes. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2022) 19(13):8113. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19138113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vicus D, Finch A, Cass I, Rosen B, Murphy J, Fan I, et al. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 germ line mutations among women with carcinoma of the fallopian tube. Gynecol Oncol (2010) 118(3):299–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Poveda A, Floquet A, Ledermann JA, Asher R, Penson RT, Oza AM, et al. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a final analysis of a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol (2021) 22(5):620–31. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00073-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu J, Li Z, Lu T, Pan J, Li L, Song Y, et al. Genomic landscape, immune characteristics and prognostic mutation signature of cervical cancer in China. BMC Med Genomics (2022) 15(1):231. doi: 10.1186/s12920-022-01376-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Imyanitov E, Sokolenko A. Integrative genomic tests in clinical oncology. Int J Mol Sci (2022) 23(21):13129. doi: 10.3390/ijms232113129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jiang T, Jiang L, Dong X, Gu K, Pan Y, Shi Q, et al. Utilization of circulating cell-free DNA profiling to guide first-line chemotherapy in advanced lung squamous cell carcinoma. Theranostics (2021) 11(1):257–67. doi: 10.7150/thno.51243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv preprint; (2013). doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1303.3997 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lai Z, Markovets A, Ahdesmaki M, Chapman B, Hofmann O, McEwen R, et al. VarDict: a novel and versatile variant caller for next-generation sequencing in cancer research. Nucleic Acids Res (2016) 44(11):e108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Garrison E, Marth G. Haplotype-based variant detection from short-read sequencing. arXiv preprint; (2012). doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1207.3907 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res (2010) 38(16):e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Karczewski KJ, Weisburd B, Thomas B, Solomonson M, Ruderfer DM, Kavanagh D, et al. The ExAC browser: Displaying reference data information from over 60 000 exomes. Nucleic Acids Res (2017) 45(D1):D840–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Karczewski KJ Francioli L. The genome aggregation database (gnomAD). MacArthur Lab (2017). Available at: https://macarthurlab.org/2017/02/27/the-genome-aggregation-database-gnomad/ [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chalmers ZR, Connelly CF, Fabrizio D, Gay L, Ali SM, Ennis R, et al. Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med (2017) 9(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0424-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Daoud T, Sardana S, Stanietzky N, Klekers AR, Bhosale P, Morani AC. Recent imaging updates and advances in gynecologic malignancies. Cancers (Basel) (2022) 14(22):5528. doi: 10.3390/cancers14225528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Therachiyil L, Anand A, Azmi A, Bhat A, Korashy HM, Uddin S. Role of RAS signaling in ovarian cancer. F1000Res (2022) 11:1253. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.126337.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xie C, Luo J, He Y, Jiang L, Zhong L, Shi Y. BRCA2 gene mutation in cancer. Med (Baltimore) (2022) 101(45):e31705. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000031705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Johansen EL, Thusgaard CF, Thomassen M, Boonen SE, Jochumsen KM. Germline pathogenic variants associated with ovarian cancer: A historical overview. Gynecol Oncol Rep (2022) 44:101105. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2022.101105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kanchi KL, Johnson KJ, Lu C, McLellan MD, Leiserson MD, Wendl MC, et al. Integrated analysis of germline and somatic variants in ovarian cancer. Nat Commun (2014) 5:3156. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature (2011) 474(7353):609–15. doi: 10.1038/nature10166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang X, Jia W, Wang M, Liu J, Zhou X, Liang Z, et al. Human papillomavirus integration perspective in small cell cervical carcinoma. Nat Commun (2022) 13(1):5968. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-33359-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yokoi A, Minami M, Hashimura M, Oguri Y, Matsumoto T, Hasegawa Y, et al. PTEN overexpression and nuclear β-catenin stabilization promote morular differentiation through induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell-like properties in endometrial carcinoma. Cell Commun Signal (2022) 20(1):181. doi: 10.1186/s12964-022-00999-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Li N, Liu Q, Tian Y, Wu L. Overview of fuzuloparib in the treatment of ovarian cancer: Background and future perspective. J Gynecol Oncol (2022) 33(6):e86. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2022.33.e86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vencken PMLH, Kriege M, Hoogwerf D, Beugelink S, van der Burg MEL, Hooning MJ, et al. Chemosensitivity and outcome of BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated ovarian cancer patients after first-line chemotherapy compared with sporadic ovarian cancer patients. Ann Oncol (2011) 22(6):1346–52. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kwong A, Shin VY, Ma ES, Chan CT, Ford JM, Kurian AW, et al. Screening for founder and recurrent BRCA mutations in Hong Kong and US Chinese populations. Hong Kong Med J (2018) 24 Suppl 3(3):4–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. de Juan Jiménez I, García Casado Z, Palanca Suela S, Esteban Cardeñosa E, López Guerrero JA, Segura Huerta Á, et al. Novel and recurrent BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations in early onset and familial breast and ovarian cancer detected in the program of genetic counseling in cancer of valencian community (eastern Spain). Relationship Family phenotypes Mutat prevalence Fam Cancer (2013) 12(4):767–77. doi: 10.1007/s10689-013-9622-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhang Y, Wu H, Yu Z, Li L, Zhang J, Liang X, et al. Germline variants profiling of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in Chinese hakka breast and ovarian cancer patients. BMC Cancer (2022) 22(1):842. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-09943-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bolton KL, Chenevix-Trench G, Goh C, Sadetzki S, Ramus SJ, Karlan BY, et al. Association between BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and survival in women with invasive epithelial ovarian cancer. JAMA (2012) 307(4):382–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hu-Lieskovan S, Bhaumik S, Dhodapkar K, Grivel JJB, Gupta S, Hanks BA, et al. SITC cancer immunotherapy resource document: A compass in the land of biomarker discovery. J Immunother Cancer (2020) 8(2):e000705. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yarchoan M, Hopkins A, Jaffee EM. Tumor mutational burden and response rate to PD-1 inhibition. N Engl J Med (2017) 377(25):2500–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1713444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Samstein RM, Lee CH, Shoushtari AN, Hellmann MD, Shen R, Janjigian YY, et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat Genet (2019) 51(2):202–6. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0312-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wang H, Liu J, Yang J, Wang Z, Zhang Z, Peng J, et al. A novel tumor mutational burden-based risk model predicts prognosis and correlates with immune infiltration in ovarian cancer. Front Immunol (2022) 13:943389. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.943389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhu S, Zhang C, Cao D, Bai J, Yu S, Chen J, et al. Genomic and TCR profiling data reveal the distinct molecular traits in epithelial ovarian cancer histotypes. Oncogene (2022) 41(22):3093–103. doi: 10.1038/s41388-022-02277-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jiang T, Chen J, Xu X, Cheng Y, Chen G, Pan Y, et al. On-treatment blood TMB as predictors for camrelizumab plus chemotherapy in advanced lung squamous cell carcinoma: Biomarker analysis of a phase III trial. Mol Cancer (2022) 21(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01479-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Huang RSP, Haberberger J, Harries L, Severson E, Duncan DL, Ferguson NL, et al. Clinicopathologic and genomic characterization of PD-L1 positive urothelial carcinomas. Oncologist (2021) 26(5):375–82. doi: 10.1002/onco.13753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material . Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.