Abstract

Background & objectives:

Accurate and early diagnosis is imperial in the management of endometriosis, endometrioid carcinoma of ovary (ECO) and endometrioid endometrial cancer (EC), yet there are no definitive diagnostic methods available for these diseases. Therefore, the present study was aimed to evaluate the diagnostic potential of differentially expressed miRNAs in serum samples of women with endometriosis, ECO and EC to establish them as diagnostic biomarkers.

Methods:

Blood samples (5 ml) were obtained from 40 patients (n=10/study group) undergoing laparoscopy/laparotomy/hysterectomy. miRNA-rich RNA was extracted from the serum samples, and quantitative real-time (qRT)-PCR was performed to check the expression levels of miR-16, miR-99b, miR-20a, miR-145, miR-143 and miR-125a in all the samples. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was done to check the diagnostic potential.

Results:

In endometriosis, miR-16 was downregulated (P<0.05) whereas miR-99b, miR-125a, miR-143 and miR-145 were upregulated (P<0.05). In ECO group, downregulated expression of miR-16 and miR-125a (P<0.05) was observed, whereas miR-99b, miR-143 and miR-145 were upregulated (P<0.05). In endometrioid EC, miR-16, miR-99b, miR-125 and miR-145 were downregulated (P<0.05), whereas miR-143 was upregulated (P<0.05). ROC curve analysis showed that, for endometriosis, miR-99b, miR-125a, miR-143 and miR-145 served as diagnostic markers. miR-145 showed diagnostic power for ECO, and for endometrioid EC, miR-16, miR-99b, miR-125a and miR-145 showed diagnostic potential.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The present findings suggested that certain circulating miRNAs (miB99b, miR-16, miR-125a, miR-145) might act as indicators and discriminators of endometriosis and endometrioid subtypes of EC and ovarian cancer and might serve as potential biomarkers for early diagnosis and management of these debilitating diseases.

Keywords: Endometrioid carcinoma of ovary, endometrioid endometrial cancer, endometriosis, miRNA

MicroRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) are 19-22 nucleotide long small non-coding RNA molecules that can control post-transcriptional gene expression1. First discovered in 1993, miRNAs have been found to be important regulators of gene expression in a wide range of physiologic processes and pathologic conditions2,3. It is paramount to understand that miRNA expression is specific for tissue or cell type and 3’UTR region of a particular mRNA can bind to several miRNAs and also a single miRNA can target hundreds of mRNAs4. Therefore, differential regulation of miRNAs may alter a wide range of physiological processes5. MiRNAs emerge as ideal candidates for non-invasive biomarkers due to their tissue specificity, lower complexity and presence in diverse body fluids (plasma, serum, peritoneal fluid, etc.)6.

Various studies showed that the differential miRNA expressions were associated with several human diseases such as cancer, inflammatory diseases, benign or malignant diseases of human female reproductive tract including endometriosis (ED), endometrioid endometrial cancer (EC) and endometrioid carcinoma of ovary (ECO)7–11. Endometriosis is a commonly occurring gynaecological disease and resembles malignancies in many ways such as unrestrained growth, cell invasiveness, neo-angiogenesis and loss of apoptosis, and the chances of having endometrioid histological subtypes of ovarian cancer and EC increase in patients having endometriosis12,13.

The current gold standard for the diagnosis of endometriosis and associated endometrioid ovarian cancer and EC is surgical intervention to obtain biopsy for histological confirmation. Several efforts have been made to achieve a minimally invasive diagnosis with the help of blood biomarkers14.

In the present study, the differential miRNA expression was evaluated in serum samples of women with endometriosis, ECO and endometrioid EC to check the diagnostic potential of these miRNAs and to establish these as possible diagnostic biomarkers. Since miRNAs are stable in body fluids, these can act as biomarkers for early detection and timely management of these diseases, six microRNAs, i.e. miR-16, miR-20a, miR-125a, miR-143, miR-99b and miR-145 that are most commonly dysregulated in endometriosis, endometrioid EC and endometrioid ovarian cancer were selected. These are found to be important in pathophysiology of these three gynaecologic diseases by altering the expression of genes involved in inflammation, hypoxia, angiogenesis and cell proliferation14,15–17.

Material & Methods

Sample collection: The present study was carried out from November 2016 to December 2019 in the department of Zoology, Panjab University, Chandigarh. The study was approved by the Institution Ethics Committee and written informed consent was obtained from all the patients before recruitment. It was an exploratory study which included total number of 40 patients who underwent laparoscopy/laparotomy/hysterectomy for various gynaecological conditions such as pelvic pain, endometriosis, infertility, endometrial hyperplasia, ovarian tumours, fibroid and prolapse, etc. Patients were assigned to three groups after obtaining histopathological reports confirming histopathology for endometriosis (group I), endometrioid EC (group II) and endometrioid ovarian carcinoma (group III) and benign pathology (control). Each group comprised of 10 patients.

All the patients were abstained from food for at least 8 h before surgery. Blood samples (5 ml) were collected before anaesthesia in sterile tubes without any anticoagulant. Serum was separated and stored in sterile plastic tubes as 0.5 ml aliquots at −80°C. The baseline clinical characteristics of all the study groups are represented in Table I.

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of patients in all the study groups

| Clinical feature | Group I (ED) (n=10) | Group II (EC) (n=10) | Group III (ECO) (n=10) | Control group (n=10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr), Mean±SD (range) | 30.4±6.8 (23-39) | 55.3±15.53 (32-80) | 45.30±10.57 (27-62) | 47.5±4.43 (40-55) |

| Comorbidities n (%) | Nil | 1 (10) | 2 (20) | 1 (10) |

| Smoking | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Alcohol-intake | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Type of infertility n (%) | ||||

| 1° infertility | 6 (60) | 2 (20) | Nil | 1 (10) |

| 2° infertility | 3 (30) | Nil | 2 (20) | 2 (20) |

| Nulliparity | 1 (10) | Nil | Nil | Nil |

ED, endometriosis; EC, endometrioid endometrial cancer; ECO, endometrioid carcinoma of ovary

miRNA isolation and cDNA synthesis: Total RNA including miRNAs was extracted from all the serum samples by using miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit (Catalogue no. 217184, Qiagen India Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, India) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Spike-In Control (lyophilized C. elegans miR-39 miRNA mimic 10 pmol) (Catalogue no. 219610, Qiagen) was added during RNA isolation procedure for normalization of RNA yield and amplification. Total 10-12 μl of miRNA-enriched RNA was eluted in nuclease-free water. The quality and yield of RNA were determined with Nanodrop Spectrophotometer (My SPEC, serial #1200012, Thermo Fisher Scientific India). RNA 25 ng from each sample was reverse transcribed using miScript II RT Kit (Cat # 21816, Qiagen) as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative real-time PCR for serum miRNA expression: Serum miRNA expressions of previously selected miRNAs were analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) by miScript SYBR Green PCR Kit (Catalogue no. 218073, Qiagen) with specific forward and reverse primers for miR-16, miR-20a and U6 snRNA designed by Primer 3 Impressum software (http://primer3.ut.ee). For remaining miRNAs, specific forward primers were obtained from miScript Primer Assays, Qiagen India Pvt. Ltd., and universal reverse primer provided in the miScript SYBR Green PCR Kit (Table II). The PCR reaction mixture (10 µl) included: 1 µl of cDNA, 5 µl SYBR Green master mix (2x), 1 µl of each forward primer, 1 µl of universal reverse primer and 2 µl of nuclease-free water. The thermal cycling conditions for qRT-PCR included 15 min initial denaturation at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 15 sec, 55-57°C for 30 sec and 70°C for 30 sec. CT values and melting peak analysis were done. Expression of miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Spike-In Control (lyophilized C. elegans miR-39 miRNA mimic) and U6 snRNA was used as reference control to determine relative miRNA expression. Table II summarizes the primer sequences used in qRT-PCR.

Table II.

Primers sequences and their melting temperatures (Tm) used in quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

| MicroRNA | Tm (°C) | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| miR-16* | 57 | F 5’- CAGTGCCTTAGCAGCACGTA-3’ R5’- ACCTTACTTCAGCAGCACAGTT-3’ |

| miR-20a* | 57 | F5’- GTGTTTTGTAGCACTAAAGTGCTTATA-3’ R5’- GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT-3’ |

| U6 snRNA* | 57 | F5’- AAACTCAAGACAATGGTGATAATGG-3’ R5’- AGGAATACGCAGAAAGGTAGTCC-3’ |

| miR-99b-5p (MS00032165)# | 55 | F5’CACCCGUAGAACCGACCUUGCG |

| miR-125a-5p (MS00003423)# | 55 | F5’UCCCUGAGACCCUUUAACCUGUGA |

| miR-143-3p (MS00003514)# | 55 | F5’UGAGAUGAAGCACUGUAGCUC |

| miR-145-5p (MS00003528)# | 55 | F5’GUCCAGUUUUCCCAGGAAUCCCU |

| cel-miR-39-3p. Spike in control (217184)# | 55 | F5’UCACCGGGUGUAAAUCAGCUUG |

*Primers were synthesized using Primer 3 software, #Primers were commercially obtained from Qiagen India Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi

Statistical analysis: The data was analysed using SPSS software version 19.0 (IBM, New York, USA). All data were represented as mean±standard deviation or standard error as and when appropriate. Normality of the data was checked by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare the expression levels of serum miRNAs in all the disease groups compared to the control group. For pair-wise comparison between the groups, Kruskal-Wallis test was followed by a post hoc test with Bonferroni corrections. Diagnostic potential of serum miRNAs was analyzed by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, and sensitivity and specificity were calculated.

Results

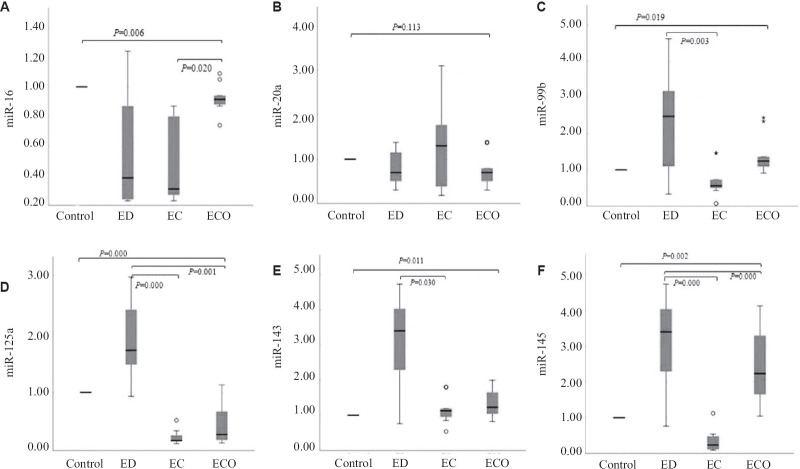

Expression of serum miRNAs in all the study groups: A significant downregulated expression of miR-16 (P<0.05) was observed in all the three disease groups as compared to the control group. miR-20a was downregulated in endometriosis and ECO while, upregulated in the EC study groups, but did not reach the significance. In the case of miR-99b, significantly increased expression levels (P<0.05) were observed in endometriosis and ECO whereas significantly downregulated expression (P<0.05) was observed in endometrioid EC compared to control group. miR-125a was significantly upregulated (P<0.001) in endometriosis whereas significantly downregulated in endometrioid EC and ECO (P<0.001) compared to controls. Significantly upregulated expression of miR-143 was observed in groups I-III (P<0.05) as compared to controls. miR-145 expression levels were significantly upregulated in endometriosis and ECO (P<0.05) groups and significantly downregulated in endometrioid EC (P<0.05) compared to control group. The expression levels of all serum miRNAs are represented in Fig. 1.

Fig 1.

Relative expression levels of serum miRNAs in women with ED, endometrioid EC and ECO as compared to control group. (A) miR-16, (B) miR-20a, (C) miR-99b, (D) miR-125a, (E) miR-143 and (F) miR-145. ED, endometriosis; EC, endometrial cancer; ECO, endometrioid carcinoma of ovary. Note: Data are represented as box plots. Here, the boxes represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, and a solid line within the box showing median value.

Target prediction of selected miRNAs: TargetScan (TargetScanHuman 7.2, https://www.targetscan.org/vert_72/), miRDB (MicroRNA target prediction database, https://mirdb.org/) and miRWalk 3.0 (http://mirwalk.umm.uni-heidelberg.de/) online tools were used to predict the target genes for previously selected miRNAs (i.e. miR-16, miR-20a, miR-99b, miR-125a, miR-143 and miR-145). For these miRNAs, several genes were predicted as a target, including genes that are known to be dysregulated in endometriosis as well as endometrioid histological subtypes of EC and ovarian cancer such as cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2), vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), HIF1A, TNF, MYC and TP53 (Table III).

Table III.

Some of the predicted targets of miRNAs differentially regulated in endometriosis and endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer by TargetScan, miRDB and miRWalk 3.0 programmes

| miRNA | Predicted targets |

|---|---|

| miR-16 | HIF1A, TNF, VEGFA |

| miR-20a | HIF1A, VEGFA, TNF, TP53, MYC |

| miR-99b | COX2, TP53 |

| miR-125a | VEGFA, TNF, MYC, TP53, COX2 |

| miR-143 | COX2, VEGFA, HIF1A, TNF |

| miR-145 | COX2, VEGFA, HIF1A, MYC |

COX2, cyclooxygenase2; HIF1A, hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha; MYC, myelocytomatosis; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; TP53, tumor protein P53 ; VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A

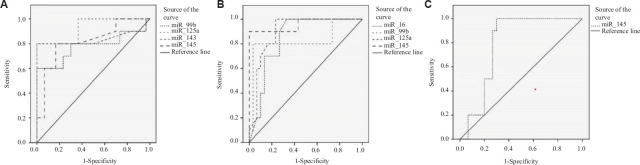

ROC curve analysis to assess the diagnostic potential of circulating miRNAs: For assessment of diagnostic values of these differentially expressed miRNAs in endometriosis, endometrioid EC and ECO, ROC curve analysis was performed. For endometriosis, miR-99b [area under the curve (AUC)=0.777, P=0.010], miR-125a (AUC=0.927, P=0.000), miR-143 (AUC=0.837, P=0.002) and miR-145 (AUC=0.817, P=0.003) were found to be the best predictors with good AUC (Fig. 2). For endometrioid EC, miR-16 (AUC=0.850, P=0.001), miR-99b (AUC=0.830, P=0.002), miR-125a (AUC=0.900, P=0.000) and miR-145 (AUC=0.957, P=0.000) were found to be the best predictors (Fig. 2) with good sensitivity and specificity, as represented in Table IV. For ECO, only one microRNA, i.e. miR-145 (AUC=0.790, P=0.007), was found to be the best predictor (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

ROC curves of different miRNAs in the serum of women with ED, endometrioid EC and ECO. (A) For endometriosis, miR-99b, miR-125a, miR-143 and miR-145 showed the highest AUC values of 0.777, 0.927, 0.837 and 0.817, respectively. (B) For endometrioid endometrial cancer, miR-16, miR-99b, miR-125a and miR-145 give the highest AUC values of 0.850, 0.830, 0.900 and 0.957, respectively. (C) For endometrioid ovarian cancer, miR-145 gives the highest AUC of 0.790. ED, endometriosis; EC, endometrial cancer; ECO, endometrioid carcinoma of ovary; ROC, Receiver operating characteristics; AUC, area under the curve

Table IV.

Area under curves for differentially regulated miRNAs in endometriosis, endometrioid endometrial cancer and endometrioid carcinoma of ovary study subjects

| miRNA | AUC | P | 95% CI | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Cut-off value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I (ED) | ||||||

| miR-99b | 0.777 | 0.010 | 0.584-0.989 | 80 | 70 | 1.09 |

| miR-125a | 0.927 | 0.000 | 0.827-1.026 | 80 | 100 | 1.30 |

| miR-143 | 0.837 | 0.002 | 0.628-1.046 | 80 | 100 | 2.14 |

| miR-145 | 0.817 | 0.003 | 0.656-0.978 | 83 | 83 | 2.14 |

| Group II (EC) | ||||||

| miR-16 | 0.850 | 0.001 | 0.733-0.967 | 90 | 73 | 0.835 |

| miR-99b | 0.830 | 0.002 | 0.645-1.015 | 80 | 96 | 0.805 |

| miR-125a | 0.900 | 0.000 | 0.805-0.995 | 90 | 77 | 0.430 |

| miR-145 | 0.957 | 0.000 | 0.872-1.041 | 90 | 100 | 0.650 |

| Group III (ECO) | ||||||

| miR-145 | 0.790 | 0.007 | 0.653-0.927 | 90 | 73 | 1.17 |

ED, endometriosis; EC, endometrioid endometrial cancer; ECO, endometrioid carcinoma of ovary; AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval

Discussion

In this study, the expression and diagnostic potential of circulating miR-16, miR-20a, miR-99b, miR-125a, miR-143 and miR-145 have been evaluated for endometriosis, endometrioid EC and ECO. miR-99b, miR-125a, miR-143 and miR-145 showed highest diagnostic potential for endometriosis. miR-16, miR-99b, miR-125a and miR-145 showed potential as serum biomarkers for endometrioid EC and miR-145 displayed good diagnostic power as a serum biomarker for ECO. By target analysis the target genes of the studied miRNAs was predicted and it was found that all these miRNAs target genes which are known to be dysregulated in all these three associated diseases, suggesting that these miRNAs may be suitable diagnostic candidates for these diseases.

Several mature miRNAs circulate in body fluids such as serum, and may serve as biomarkers for endometriosis as well as endometrioid histological subtype of EC and ovarian cancer7,10,11.

In the present study, expression of miR-16 was significantly downregulated in the serum of all the patients as compared to controls. Differential regulation of miR-16 has been previously reported in endometriosis as well as ECO10,18,19 which results in upregulation of its target genes such as COX2 and VEGFA known to be important players in inflammation and angiogenesis. ROC curve analysis showed that miR-16 had a diagnostic potential for endometrioid EC with AUC of 0.850 and displayed a sensitivity and specificity of 90 and 73 per cent, respectively, at the cut-off value of 0.835. Thus, miR-16 downregulation appears to be crucial in inducing hypoxia, inflammation and angiogenesis in endometrioid EC. As far as endometriosis and ECO are concerned more research would be required to find the diagnostic role of miR-16.

Previous studies showed that, miR-20a was considered to be a leading biomarker for endometriosis14,20. However, in the present study, miR-20a expression levels were not significantly altered in all three disease groups as compared to the control group. Serum expression levels of miR-99b were found to be significantly upregulated in patients with endometriosis as well as ECO group and also ROC curve analysis revealed that it had AUC of 0.777 (P=0.010) with 80 per cent sensitivity and 70 per cent specificity with a cut-off value of 1.09 for differentiating endometriosis from other study groups. In line with our results, Teague et al15 confirmed the upregulated expression of miR-99b in ectopic endometriotic cysts as compared to control eutopic endometrium. Hence, one can speculate that increased serum levels of miR-99b might act as an important diagnostic marker for endometriosis. miR-99b was significantly downregulated in the patients with endometrioid EC. This observation was similar as reported previously in some studies21,22.

An upregulated expression of miR-125a was observed in patients with endometriosis, whereas downregulated expression of this miRNA was found in patients with endometrioid EC and ovarian cancer as compared to control groups as has been reported earlier15,23,24 which suggested its role in ErbB (erythroblastic leukaemia viral oncogene homologue) signalling as well as in cell migration and invasion. Our results of ROC curve analysis revealed that miR-125a had a diagnostic potential for endometriosis as well as endometrioid EC which was in corroboration with previously reported studies25,26.

miR-143 and miR-145 were significantly upregulated in patients with endometriosis and ECO as compared to controls. Both miR-143 and miR-145 are the part of miR-143/145 cluster which is co-expressed usually in many types of cancers27. In endometriosis, both miR-143 and miR-145 were found upregulated in previous studies15,28 and play an important role in pathophysiology by targeting genes such as mitogen-activated protein kinase 7, Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homologue, junctional adhesion molecule A and plasminogen activator inhibitor 129.30. In endometrioid EC group, miR-143 was found to be significantly upregulated whereas miR-145 was found to be significantly downregulated. Previously, Zhang et al16 reported downregulated expression of miR-143 and miR-145 in endometrioid EC and DNA-methyltransferase 3 beta was found to be a potential target of these miRNAs. Furthermore, ROC curve analysis revealed that miR-145 has significant potential as a serum biomarker for endometrioid EC.

The present study had some limitations such as small sample size and lack of miRNA mediated gene regulation validation of differentially expressed serum miRNAs. The limiting factor for small sample size was endometrioid histological subtypes of ovarian cancer because of its rare prevalence and inclusion after histopathological confirmation. Despite these limitations, the present study provided significant lead to validate miRNAs as potential biomarkers for these three gynaecological disorders and future research would be required to confirm these findings in a large sample. In future, these miRNAs could be used as important therapeutic targets to generate new treatment strategies for these gynaecological disorders.

Footnotes

Financial support & sponsorship: The study was funded by the grant from University Grant Commission (UGC) CAS-II (F.4-28/2015(CAS-II)(SAP-II). The author (IS) received grant from the Department of Science and Technology (DST)-Science Engineer and Research Board (SERB) (ECR/2016/000359), New Delhi; author (PK) received UGC Junior Research Fellowship (22/06/2014(i) EU-V).

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs:Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iorio MV, Croce CM. MicroRNA dysregulation in cancer:Diagnostics, monitoring and therapeutics. A comprehensive review. EMBO Mol Med. 2012;4:143–59. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201100209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhayani MK, Calin GA, Lai SY. Functional relevance of miRNA sequences in human disease. Mutat Res. 2012;731:14–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Brien J, Hayder H, Zayed Y, Peng Overview of microRNA biogenesis, mechanisms of actions and circulation. Front Endocrinol. 2018;9:402. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilabert-Estelles J, Braza-Boils A, Ramon LA, Zorio E, Medina P, Espana F, et al. Role of microRNAs in gynecological pathology. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19:2406–13. doi: 10.2174/092986712800269362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ortiz-Quintero B. Cell-free microRNAs in blood and other body fluids, as cancer biomarkers. Cell Prolif. 2016;49:281–303. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montagnana M, Benati M, Danese E, Giudici S, Perfranceschi M, Ruzzenenete O, et al. Aberrant MicroRNA expression in patients with endometrial cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27:459–66. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiofalo B, Laganà AS, Vaiarelli A, La Rosa VL, Rossetti D, Palmara V, et al. Do miRNAs play a role in Fetal growth restriction?A fresh look to a busy corner. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:6073167. doi: 10.1155/2017/6073167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tahamtan A, Teymoori-Rad M, Nakstad B, Salimi V. Anti-inflammatory MicroRNAs and their potential for inflammatory diseases treatment. Front Immunol. 2018;1377;9 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vanhie A, OD, Peterse D, Beckers A, Cuéllar A, Fassbender A, et al. Plasma miRNAs as biomarkers for endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2019;34:1650–60. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen SN, Chang R, Lin LT, Chern CU, Tsai HW, Wen ZH, et al. MicroRNA in ovarian cancer:Biology, pathogenesis, and therapeutic opportunities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;1510;16 doi: 10.3390/ijerph16091510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bulun SE, Yilmaz BD, Sison C, Miyazaki K, Bernardi L, Liu S, et al. Endometriosis. Endocr Rev. 2019;40:1048–79. doi: 10.1210/er.2018-00242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krawczyk N, Banys-Paluchowski M, Schmidt D, Ulrich U, Fehm T. Endometriosis-associated malignancy. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2016;76:176–81. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1558239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moga MA, Bălan A, Dimienescu OG, Burtea V, Dragomir RM, Anastasiu CV. Circulating miRNAs as biomarkers for endometriosis and endometriosis-related ovarian cancer –An overview. J Clin Med. 2019;8:735. doi: 10.3390/jcm8050735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohlsson Teague EM, Van der Hoek KH, Van der Hoek MB, Perry N, Wagaarachchi P, Robertson SA, et al. MicroRNA-regulated pathways associated with endometriosis. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:265–75. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J, Sun Q, Zhang Z, Ge S, Han ZG, Chen WT. Loss of microRNA-143/145 disturbs cellular growth and apoptosis of human epithelial cancers by impairing the MDM2-p53 feedback loop. Oncogene. 2013;32:61–9. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang L, Yuan Z, Shi H, Bian Y, Guo R. miR-145 targets the SOX11 3'UTR to suppress endometrial cancer growth. Am J Cancer Res. 2017;7:2305–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, Ren R, Shao M, Lan J. MicroRNA-16 inhibits endometrial stromal cell migration and invasion through suppression of the inhibitor of nuclear factor-κB kinase subunit β/nuclear factor-κB pathway. Int J Mol Med. 2020;46:740–50. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2020.4620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saral MA, Tuncer SB, Odemis DA, Erdogan OS, Erciyas SK, Saip P, et al. New biomarkers in peripheral blood of patients with ovarian cancer:high expression levels of miR-16-5p, miR-17-5p, and miR-638. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2022;305:193–201. doi: 10.1007/s00404-021-06138-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jia SZ, Yang Y, Lang J, Sun P, Leng J. Plasma miR-17-5p, miR-20a and miR-22 are down-regulated in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:322–30. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torres A, Torres K, Pesci A, Ceccaroni M, Paszkowski T, Cassandrini P, et al. Deregulation of miR-100, miR-99a and miR-199b in tissues and plasma coexists with increased expression of mTOR kinase in endometrioid endometrial carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:369. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torres A, Torres K, Pesci A, Ceccaroni M, Paszkowski T, Cassandrini P, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of miRNA signatures in tissues and plasma of endometrioid endometrial carcinoma patients. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:1633–45. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Z, Guo X, Sun S, Lu C, Wang L. Serum miR-125b levels associated with epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) development and treatment responses. Bioengineered. 2020;11:311–7. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2020.1736755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cosar E, Mamillapalli R, Ersoy GS, Cho S, Seifer B, Taylor HS. Serum microRNAs as diagnostic markers of endometriosis:A comprehensive array-based analysis. Fertil Steril. 2016;106:402–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang J, Li G, Zhang K. MiR-125a regulates ovarian cancer proliferation and invasion by repressing GALNT14 expression. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;80:381–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2015.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee M, Kim EJ, Jeon MJ. MicroRNAs 125a and 125b inhibit ovarian cancer cells through post-transcriptional inactivation of EIF4EBP1. Oncotarget. 2016;7:8726–42. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harati-Sadegh M, Sargazi S, Saravani M, Sheervalilou R, Mirinejad S, Saravani R. Relationship between miR-143/145 cluster variations and cancer risk:proof from a Meta-analysis. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2021;40:578–91. doi: 10.1080/15257770.2021.1916030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng B, Xue X, Zhao Y, Chen J, Xu CY, Duan P. The differential expression of microRNA-143,145 in endometriosis. Iran J Reprod Med. 2014;12:555–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen X, Guo X, Zhang H, Xiang Y, Chen J, Yin Y, et al. Role of miR-143 targeting KRAS in colorectal tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2009;28:1385–92. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adammek M, Greve B, Kässens N, Schneider C, Brüggemann K, Schüring AN, et al. MicroRNA miR-145 inhibits proliferation, invasiveness, and stem cell phenotype of an in vitro endometriosis model by targeting multiple cytoskeletal elements and pluripotency factors. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:1346–55. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.11.055. e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]