Abstract

Objective

This study was conducted to explore frontline nurses’ experiences of the impact of COVID 19 pandemic and suggestions for improvement in the healthcare system, policy and practice in the future.

Method

A qualitative descriptive design was used. Frontline nurses who were involved in providing care to patients affected with COVID 19 in four designated COVID units from the Eastern, Southern and Western regions of India were interviewed during January to July 2021. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed manually by researchers from each region and thematically analysed.

Result

Twenty-six frontline nurses aged between 22 and 37 years with a range of 1–14 years of work experience following a Diploma or Bachelor's degree in Nursing and Midwifery and working in the COVID units of selected regions in India participated in the study. Three key themes emerged: ‘Physical, emotional and social health - an inevitable impact of the pandemic’ described effects of the pandemic on nurses' health and wellbeing; ‘Adapting to the uncertainties’ narrated how nurses accommodated to the uncertainties during the pandemic; and ‘An agenda for the future - suggestions for improvement’ emphasised on practical strategies for the future.

Conclusion

The inevitability of the pandemic had an influence at a personal, professional, and social level with learning for the future. The findings of this study have implications for healthcare system and facilities by enhancing resources, supportive environment for staffs to cope with the challenges imposed by the crisis and ongoing training to manage life threatening emergencies in the future.

Keywords: Frontline nurses, COVID 19 global pandemic, Qualitative, Experience, Views, Perspectives, Suggestions

1. Introduction

Nurses as frontline healthcare workers play a unique, crucial and multidimensional role as care providers, educators, researchers and leaders contributing to the workforce ensuring team integrity and demonstrating leadership skills.1 Nurses worldwide describe their role as challenging with rising complexities in healthcare settings.2 The COVID 19 pandemic has been an inevitable challenge for all frontline workers who worked as ‘warriors’ during this global crisis.3

Lack of adequate and appropriate information about COVID-19, unpredictable tasks and challenging practices, limited or lack of support, and stress were a few of many challenges introduced by the pandemic4 with marked inconsistencies in provision of care in some sectors.5 Staff shortages and lack of availability of beds were ongoing issues6 leading to staff burnout necessitating the urgent need to prepare nurses and the healthcare system to face potential challenges.7

Many nurses experienced the impact of the pandemic in their personal and professional lives,8 and even many sacrificed their lives.9 While it was difficult for the public to cope with the pandemic with fear and uncertainty,10 it was challenging for frontline nurses to cope with their own physical and emotional health, work pressure, family and social relationships.3 Multiple studies have been conducted3 , 4 , 6 , 7 more new studies are needed to understand the extent to which the ongoing pandemic had affected their personal, professional, and social life and their suggestions on ways to improve and advance the healthcare system to cope with similar challenges in the future. India was intensely affected with the pandemic with a rising death toll of over 525, 000 deaths until July 2022. India being a large country the infrastructure and system of practice varied from one region to the others. Previous similar studies from India have highlighted on healthcare workers'9 and nurses'11 experience during the pandemic. Beyond this, it is now time to highlight on the wider context from frontline nurses' experiences, and address the concerns raised, and recommendations made by the frontline nurses who played an active role in the most crucial time during the pandemic. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore a wider perspective and experiences of frontline nurses during the COVID 19 pandemic working in selected COVID units in multiple regions in India.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

A qualitative descriptive study design was used to get an insight into nurses’ experiences and perspectives. Qualitative descriptive studies allow flexibility in methods while optimising collection of rich data and allowing for an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon of interest12 and staying connected to the realities associated with personal experiences of participants and individual perspectives.13

2.2. Setting and participants

The four study settings (one from the Easter region. One from the western region and two from the Southern regions in India) were approx. 1150 bedded designated COVID units within the tertiary care hospitals that facilitated provision of care to over 190,000 patients affected with COVID until December 2021. A total of 730 nurses worked as frontline healthcare providers in these four units whose primary role was to provide care to patients affected with COVID.

Following ethical approval from the research ethics committees of the selected hospitals, nurses working in the four major COVID hospitals in the Eastern, Western and Southern regions in India were recruited and interviewed for the study during January to July 2021, the second wave of the pandemic.

2.3. Data collection and analysis

The study information was shared with all eligible nurses in the selected COVID units. Nurses who were willing to participate were invited to sign and return the study consent form directly to the researcher, and a date/time was mutually agreed for the interview.

Semi structured one-to-one interviews were conducted using an interview guide (Supplementary table 1) via telephone due to ongoing COVID-19 restrictions. The average duration of the interviews were 30 min. Interview data were audio recorded and transcribed (manually). To ensure confidentiality and anonymity participants’ names were replaced with a code. Interviews were conducted with participants until no new knowledge (data saturation) was achieved.

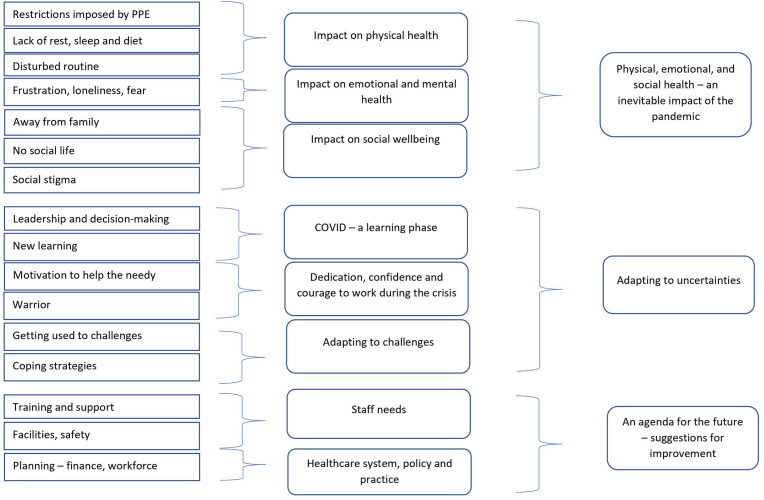

Each researcher actively engaged in the data followed by regular and extensive discussions with the lead author and the team to enhance credibility. To ensure dependability data collected from each region were independently coded by individual researchers from the respective region. The lead author independently coded five randomly selected transcripts (one from Eastern region, and two each from Western and Southern Region). There were no disagreements in coding. The lead author had experience of conducting qualitative research and thematic analysis of qualitative data in her previous studies and guided the team in the process of coding. Following all the coding, the team met to discuss and agree to the final codes, derive categories and themes, and ensure that the findings reflected the participants' voice comprehensively.14 Each participant was offered a copy of the transcript to check and confirm accuracy of their interview data to improve rigour through member checking. To ensure confirmability a decision trail was maintained15 through team meetings and discussions on field work and stepwise coding, categorising and deriving the final themes. The sample coding framework presented in Fig. 1 is an example of how individual codes derived from interview data (for example, lack of rest, sleep, diet, frustration, social stigma) were grouped together meaningfully to derive the final themes (For example, impact of the pandemic on nurses’ physical, emotional and social health).

Fig. 1.

Codes, categories and theme.

Data were managed using NVivo© version 11 and analysed thematically using Braun and Clarke's16 thematic analysis framework involving the six steps: (1) familiarising with data through transcribing, reading and re-reading the transcripts; (2) generating and identifying initial of codes; (3) searching for themes through merging of the codes into meaningful categories; (4) reviewing themes to generate a thematic analysis map; (5) refining the themes and (6) producing the report.

3. Results

Twenty-six frontline female (n = 24) and male (n = 2) staff nurses aged between 22 and 37 years with a Diploma or Bachelor's degree in Nursing and Midwifery and range of work experience ((up to 5 years (n = 14), >5–10 years (n = 7) and >10 years (n = 5)) working in the COVID units of the selected regions (Eastern Region (ER (n = 7), Western Region (WR) (n = 8) and Southern region (SR) (n = 11)) in India participated in the study. Table 1 presents the demographic details of the study participants. Three key themes emerged and presented using quotations to describe each theme.

Table 1.

Demographic details of participants.

| Sl. No. | Participant | Age in years | Gender (Female (F)/Male (M)) | Qualification | Years of experience in the current role at the time of data collection | Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ER 1 | 23 | F | Diploma in Nursing and Midwifery | 1 | Staff nurse |

| 2 | ER 2 | 22 | F | Diploma in Nursing and Midwifery | 1 | Staff nurse |

| 3 | ER 3 | 31 | F | Diploma in Nursing and Midwifery | 4 | Staff nurse |

| 4 | ER 4 | 24 | F | Diploma in Nursing and Midwifery | 1 | Staff nurse |

| 5 | ER 5 | 25 | F | Diploma in Nursing and Midwifery | 3 | Staff nurse |

| 6 | ER 6 | 22 | F | Diploma in Nursing and Midwifery | 1 | Staff nurse |

| 7 | ER 7 | 23 | F | Diploma in Nursing and Midwifery | 1 | Staff nurse |

| 8 | WR 1 | 28 | F | Bachelor of degree in Nursing and Midwifery | 3.5 | Staff nurse |

| 9 | WR 2 | 27 | F | Bachelor of degree in Nursing and Midwifery | 3 | Staff nurse |

| 10 | WR 3 | 26 | F | Bachelor of degree in Nursing and Midwifery | 4 | Staff nurse |

| 11 | WR 4 | 29 | F | Bachelor of degree in Nursing and Midwifery | 6 | Staff nurse |

| 12 | WR 5 | 25 | F | Bachelor of degree in Nursing and Midwifery | 2 | Staff nurse |

| 13 | WR 6 | 24 | F | Bachelor of degree in Nursing and Midwifery | 2 | Staff nurse |

| 14 | WR 7 | 25 | F | Bachelor of degree in Nursing and Midwifery | 2 | Staff nurse |

| 15 | WR 8 | 24 | F | Bachelor of degree in Nursing and Midwifery | 2 | Staff nurse |

| 16 | SR 1 | 34 | F | Bachelor of degree in Nursing and Midwifery | 13 | Staff nurse |

| 17 | SR 2 | 34 | F | Bachelor of degree in Nursing and Midwifery | 13 | Staff nurse |

| 18 | SR 3 | 35 | F | Bachelor of degree in Nursing and Midwifery | 13 | Staff nurse |

| 19 | SR 4 | 37 | F | Bachelor of degree in Nursing and Midwifery | 14 | Staff nurse |

| 20 | SR 5 | 30 | F | Bachelor of degree in Nursing and Midwifery | 8 | Staff nurse |

| 21 | SR 6 | 30 | F | Bachelor of degree in Nursing and Midwifery | 7 | Staff nurse |

| 22 | SR 7 | 31 | F | Bachelor of degree in Nursing and Midwifery | 9 | Staff nurse |

| 23 | SR 8 | 28 | M | Bachelor of degree in Nursing and Midwifery | 6 | Staff nurse |

| 24 | SR 9 | 29 | M | Bachelor of degree in Nursing and Midwifery | 8 | Staff nurse |

| 25 | SR 10 | 28 | F | Bachelor of degree in Nursing and Midwifery | 7 | Staff nurse |

| 26 | SR 11 | 34 | F | Bachelor of degree in Nursing and Midwifery | 13 | Staff nurse |

ER – Eastern Region, WR – Western Region and SR – Southern Region.

3.1. Theme 1 physical, emotional and social health - an inevitable impact of the pandemic

This theme highlighted on the impact of the pandemic on nurses’ physical health (for example, eating, drinking, rest and sleep), emotional health (for example, being away from family, coping with challenges) and social health (for example, stigma and fear around spread of the virus, lack of social life).

Lack of adequate rest and sleep, ongoing duty rosters with limited or no breaks, over exhaustion, dehydration, delayed voiding due to restrictions and time constraints imposed by changing from and into personal protective equipment (PPE) and change in eating and drinking routines had a direct impact on nurses’ physical health.

“I have over sweating, [have] skin allergies because of gloving, don’t have time to drink water and have to control urination and fear after completing my shift, and seeing lots of death. I have a disturbed sleep pattern.” (SR 9)

Being away from family was an emotional time while coping with the other challenges imposed by the pandemic.

“There was no scope to visit family and spend time. … [for] one year I have not visited my family.” (ER 1)

“We … could not hold [our] children … after COVID duty.” (SR 9)

Childcare was a challenge. While a few nurses explained how they managed it well with the help of their immediate family, others explained their struggle and how their children suffered with lack of childcare options.

“It depends on family support … but when no one is available for support … we have to take care of our children …” (SR 1)

The impact of the pandemic on social life was attributed to social stigma and fear among public associated with COVID. Phone and video calls were the only means of staying in touch with family and friends. Many expressed their ‘guilt’ for not being around with the family when they were needed to be there.

“I missed going out, having food outside, hanging around with friends, and even events in my family. I lost my grandfather … but … I could not step out to even witness his last rites. That guilt is always there with me, that I couldn’t be with him … when he needed my presence.” (WR 1)

“… my neighbours asked my parents to show negative [COVID] report for coming to village.” (ER 1)

Being away from immediate family was a ‘depressing’ time for many nurses. Nurses also narrated the emotional time their family went through during the pandemic.

“… I would feel depressed for not being able to go … home after duty. My father used to miss me a lot … My family members were very anxious about me. Socialising was only through medium [phone] … it was very difficult to cope. But gradually I got used to it.” (WR 3)

While the pandemic had a direct impact on nurses’ physical, emotional and social health and wellbeing, many expressed how it made them realise the value of family, friends and social life.

“… As a covid warrior I got much more realisation about the social and professional life.” (WR 5)

For many nurses it was the first time to experience such a crisis and inevitable death and dying. Many described the pandemic as a ‘new experience’ and a ‘blessing’.

It was … first time that we all were facing such disaster … a new and different experience … However, there was a positive aspect … I feel, we were … blessed to be chosen to work in this pandemic. It gave us lot of opportunities to shoulder responsibility and perform task with our own decision-making ability … it challenged us to prove our ability.” (WR 2).

This theme described the inevitability of the impact of the pandemic on nurses’ physical, emotional and social health and wellbeing.

3.2. Theme 2 adapting to the uncertainties

This theme described the uncertainties during the pandemic and how nurses coped with and adapted to the unpredictable situations while working as a frontline staff.

The circumstances around the COVID-19 pandemic were unexpected and unpredictable. Nurses believed the best way to work around it was ‘to go with the flow’. Although some nurses had personal reasons and obligations to work as a frontline staff during the pandemic, such as financial commitments, others volunteered to work to serve the needy. Everyone ‘adapted’ to the situation to their best.

“It was a very difficult time … Sometimes … I felt like I should leave and go back … home. But … I pushed myself and being honest with the profession, I understand that working in this situation is my primary responsibility. (WR 4)

Staff described being ‘habituated’ to the changing circumstances and new challenges. Although challenging, the pandemic was described as a ‘teacher’. It taught the value of family, social life, and freedom. Working during a pandemic fighting against a deadly virus and saving lives was described as ‘an opportunity’ that gave many the ‘confidence’ and ‘courage’ to deal with similar circumstances in the future. Comparing to pre-COVID working experience, nurses described that being a front-line healthcare worker during a global pandemic was a ‘golden opportunity’ and a ‘valuable’ experience.

“If I compare both times, I feel, covid times have been my greatest teacher. It has not only given me new learning experience, but has created decision-making, leadership quality and financial stability. I have a wider perspective about society. My life has … changed after COVID … I feel I have gained maturity … I have learnt promptness and compassion. (WR 1)

A few nurses described themselves as ‘warriors’ and narrated that the pandemic made them a ‘brave person and ‘confident’ to work in challenging circumstances.

“I felt … like a ‘warrior’. My … only aim is to help and protect COVID patients. I missed … my family … [but] COVID duty made me a brave person.” (SR 2)

Although many staffs were fearful in the initial days of the pandemic, the ‘acquaintance’ with the pandemic and ‘self-motivation’ to serve for the needy helped them to overcome their fear.

“Initially it was difficult to get adjusted … But as time went on, we got adjusted … [and] … gained great experience … We worked [with] … [and] motive ….” (WR 5)

Over the time nurses felt prepared to face uncertainties. Wearing PPE, working with staff shortages, and being rostered to work despite lack of sleep and rest became part of the routine.

“Challenging to wear [PPE] for 8 hours. No drinks, no toilet in between was very upsetting initially. Gradually we became habituated to that.” (ER 6)

Prayers, meditation, sharing each other's feelings and being there to support each other at these unpredictable circumstances were some of the coping strategies adapted by nurses to cope with the crisis.

“We did receive good support … everyone was sensitive towards … each other … my colleagues and roommates had become my great support.” (WR 2)

This theme narrated nurses’ experiences of how they adapted to the uncertain situations through their motivation to help the needy and coping strategies to overcome the challenges imposed by the pandemic.

3.3. Theme 3 an agenda for the future - suggestions for improvement

This theme presents nurses’ views on practical ways of managing similar crises in the future.

A few suggestions were made for improvement in the healthcare system, policy and practice in the future. Attention to staffs' needs and improvement in staffing were described as being important to ensure safety of patients' and nurses’ physical and mental health.

“Appointing/ recruiting more staff … in each shift … will help all.” (SR 1)

Along with manpower resources, nurses suggested the need to pay attention to physical and infrastructural improvements within each health sector.

“Planning … by means of adequate bed availability, oxygen supply, testing kits, [and] medicines can help to curb them.” (WR 6)

The crisis affected all other general and specialty services in most sectors. General health and other treatment facilities were neglected while focusing care for patients affected with COVID. To overcome this, nurses suggested the need for dedicated COVID units and to be prepared with a workforce to face similar crisis in the future.

“The cases are increasing, so there has to be more thoughts on creating more beds and facilities for accommodating these cases … Due to covid other illnesses are neglected … special consideration for … mental health and geriatric health has to be taken into account … government should focus on having dedicated COVID facilities … [to] ensure that the normal functioning of hospital is not hampered.” (WR 3)

Political influence had imposed inconsistencies in the provision of healthcare services equally for all COVID affected population and healthcare providers. There was discrimination around supply of masks, medications, and facilities. Nurses urged the need for the Government to pay attention to avoid any political influence in provision of health care facilities. These inconsistencies had created frustration among nurses and were demotivating factors. Nurses highlighted the importance of creating a conducive and supportive environment for all frontline nurses with a goal to create a motivated and confident workforce to face similar challenges in the future.

“There should be no more trial and error business … Its high time we start using the definitive steps and gain control over this situation. There should be less discrimination and less political interference in the functioning of the COVID centers.” (WR 2)

This theme highlighted on practical ways for healthcare organisations and policy makers to improve the healthcare system and practice to face similar challenges in the future.

4. Discussion

This study highlighted on three key themes from nurses' experiences: ‘Physical, emotional and social health - an inevitable impact of the pandemic’ which described how the pandemic had an impact on nurses' health and wellbeing; ‘Adapting to the uncertainties’ which narrated nurses' ways of coping and adapting to the unpredictable circumstances arising from the pandemic; and ‘An agenda for the future - suggestions for improvement’ highlighting on nurses' recommendations on practical strategies for improvement in the future.

The generalised impact of the pandemic was experienced by every country and healthcare system. The key role of frontline nurses was crucial in fighting against the pandemic. The pandemic had inevitably impacted nurses' physical, emotional and social health and wellbeing. Issues around lack of rest and sleep, use of PPE, the limitations imposed on using toilets while using PPEs, skipping meals and breaks, and working short staffed were similar to other studies.3 , 17 Similar to other parts of the world, dealing with death and dying, coping with the additional challenges imposed by the pandemic while being away from family and friends, and lack of socialisation were inevitable and had impacted on nurses' emotional and social health and wellbeing.3 , 18 , 19 Like most other countries, the COVID related stigma had restricted nurses from meeting their own family, friends, and neighbours.4 , 20, 21, 22 Although overwhelming, nurses learned the value of social life during the pandemic when they were deprived of meeting family and friends.4 However, nurses continued to work through their self-motivation and dedication, and demonstrated an eagerness to learn more.3 Some called themselves as ‘warriors’ and expressed a sense of responsibility to stay dedicated to their role.8 , 11 Frontline nurses' job during the pandemic involved facing the inevitability of deaths, emergencies, decision-making, showing leadership qualities, while coping with own physical and emotional health.3 Despite all the challenges, nurses narrated COVID pandemic as being a ‘teacher’ and a ‘learning opportunity’ that taught them the real value of being a frontline worker.3

Inconsistencies in healthcare provision in supply of better protective masks, PPE, other facilities and timely supply of medications and overall, a shortage of resources were among the other experiences similar among frontline nurses across all countries.5 , 6 Nurses described these experiences as ‘frustrating’ due to the political influence and favourism within the health sector. Minimising/eliminating these inconsistencies in provision of facilities was a frequent suggestion from all nurses. Participants urged attention of policy makers to provide every staff and health sector with equal opportunities and facilities and psychological and emotional support to feel motivated and empowered to face the uncertainties and challenges in the future. Increased organisational support has been associated with reduced level of anxiety among nurses during the pandemic23 suggesting the importance to pay attention to the voice from the frontline. Similar to previous literature, practical measures were suggested by all participants in the study to manage the pandemic and similar disasters in the future by paying attention to staffs and their needs, ultimately helping their physical and emotional health and wellbeing.3 , 4 Having dedicated COVID units, appointing more frontline nurses, improving physical facilities such as number of beds, and oxygen supply were a few suggestions. While nurses described as being motivated and dedicated to work under the unpredictable circumstances and save lives, they believed having the facilities to work in an environment with less stress and more support will help fight against the current and ongoing pandemic more effectively and efficiently. Although limited to the voices of frontline nurses, similar studies in the past among other healthcare workers9 , 24 , 25 has produced similar findings. Furthermore, this study provides a deep insight into the extent of the pandemic through nurses' voice and the value of addressing the issues raised and taking necessary action to be prepared to face similar challenges in the future.

Although limited to nurses' experiences, a wider perspective of nurses working in dedicated COVID units from three regions of India adds value and strength to the findings of this study. A deep insight into nurses’ experiences is an essential step in understanding measures to strengthen the future workforce in similar circumstances which will help manage it efficiently and effectively. Findings of this study may help inform future nursing practice, education and policy making to shape and strengthen the response to similar crisis in the future or outbreak of global infectious diseases. Future research can focus on long term impact of the pandemic on all healthcare staffs and effectiveness of interventions on infrastructural improvements.

5. Conclusion

This study highlighted on the impact of the pandemic on nurses' physical, emotional, social health and wellbeing including their motivation to adapt to the uncertainties around the pandemic and suggestions for improvements in the future. Frontline nurses had a crucial role in fighting against the pandemic while trying to learn from it and overcome challenges in their personal and professional lives imposed by the pandemic. This highlights the importance of nurses’ experiences in fighting against the pandemic during the crisis and similar crisis in the future.

Sources of funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author statement

Sunita Panda – Conceptualisation, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - original draft, Supervision, Project administration. Manjubala Dash - Conceptualisation, Methodology, Acquisition of data, Data curation, Writing – review and editing. Rajalaxmi Mishra - Conceptualisation, Methodology, Acquisition of data, Data curation, Writing – review and editing. Shilpa A Shettigar – Conceptualisation, Methodology, Acquisition of data, Data curation, Writing – review and editing. Delphina Mahesh Gurav – Conceptualisation, Methodology, Acquisition of data, Data curation, Writing – review and editing. Sathiya Kuppan – Conceptualisation, Methodology, Acquisition of data, Data curation, Writing – review and editing. Santhoshkumari Mohan - Methodology, Acquisition of data, Writing – review and editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the participants for their contribution to the data and authorities from the individual study sites for their help in seeking ethical committee approvals.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2023.101298.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Stewart D., Burton E., Catton H., Fokeladeh H.S., Parish C. 1201. 2021. International Council of Nurses (ICN), 3, Place Jean–Marteau. (Geneva, Switzerland) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Figueroa C.A., Harrison R., Chauhan A., Meyer L. Priorities and challenges for health leadership and workforce management globally: a rapid review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;239(19):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4080-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu H., Stjernsward S., Glasdam S. Psychosocial experiences of frontline nurses working in hospital-based settings during the COVID-19 pandemic - a qualitative systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances. 2021;3:1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnsa.2021.100037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joo J.Y., Liu M.F. Nurses' barriers to caring for patients with COVID-19: a qualitative systematic review. Int Nurs Rev. 2021;68(2):202–213. doi: 10.1111/inr.12648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheung A.T.M., Parent B. Mistrust and inconsistency during COVID-19: considerations for resource allocation guidelines that prioritise healthcare workers. J Med Ethics. 2021;47:73–77. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2020-106801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thobaity A.A., Alshammari F. Nurses on the frontline against the COVID-19 pandemic: an integrative review. Dubai Med J. 2020;3:87–92. doi: 10.1159/000509361. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galanis P., Vraka I., Fragkou D., Bilali A., Kaitelidou D. Nurses' burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(8):1–17. doi: 10.1111/jan.14839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thrysoee L., Dyrehave C., Christensen H.M., Jensen N.B., Nielsen D.S. Hospital nurses' experiences of and perspectives on the impact COVID-19 had on their professional and everyday life—a qualitative interview study. Nursing Open. 2022;9:189–198. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chakma T., Thomas B.E., Kohli S., et al. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in India & their perceptions on the way forward - a qualitative study. Indian J Med Res. 2021;153(5&6):637–648. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.ijmr_2204_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quadros S., Garg S., Ranjan R., Vijayasarathi G., Mamun M.A. Fear of COVID 19 infection across different Cohorts: a scoping review. Front Psychiatr. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.708430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salina S., Leena K.C. Experiences of registered nurses in the care of COVID-19 patients: a phenomenological study. J. Health Allied Sci. 2021;12(2):139–144. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1736276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim H., Sefcik J.S., Bradway C. Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: a systematic review. Res Nurs Health. 2017;40(1):23–42. doi: 10.1002/nur.21768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandelowski M. Focus on research methods. Whatever happened to qualitative descriptive? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cronin P., Coughlan M., Smith V. Sage Inc; London: 2015. Understanding Nursing and Healthcare Research. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Streubert H., Carpenter D. fifth ed. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; Philedelphia: 2011. Qualitative Research in Nursing: Advancing the Humanistic Imperative. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akkuş Y., Karacan Y., Güney R., Kurt B. Experiences of nurses working with COVID-19 patients: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2021;(00):1–15. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aksoy Y., Koçak V. Psychological effects of nurses and midwives due to COVID-19 outbreak: the case of Turkey. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2020;34:427–433. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2020.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alharbi J., Jackson D., Usher K. The potential for COVID-19 to contribute to compassion fatigue in critical care nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(15–16):2762–2764. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Q., Liang M., Yamin L., et al. Correspondence Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;7(4):19–20. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun N., Wei L., Shi S., et al. A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. Am. J. Infect. 2020;48:592–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie J., Tong Z., Guan X., Du B., Qiu H., Slutsky A. Critical care crisis and some recommendations during the COVID - 19 epidemic in China. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(5):837–840. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05979-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Labrague L., De los Santos J.A.A. COVID-19 anxiety among front-line nurses: predictive role of organisational support, personal resilience and social support. J Nurs Manag. 2020;28(7):1653–1661. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Almaghrabi R.H., Alfaradi H., Al Hebshi W.A., Albaadani M.M. Healthcare workers experience in dealing with Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Saudi Med J. 2020;41(6):657–660. doi: 10.15537/smj.2020.6.25101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grailey K., Lound A., Brett S. Lived experiences of healthcare workers on the front line during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative interview study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.