Abstract

Objectives

The SARS-CoV-2 Alpha variant was associated with increased transmission relative to other variants present at the time of its emergence and several studies have shown an association between Alpha variant infection and increased hospitalisation and 28-day mortality. However, none have addressed the impact on maximum severity of illness in the general population classified by the level of respiratory support required, or death. We aimed to do this.

Methods

In this retrospective multi-centre clinical cohort sub-study of the COG-UK consortium, 1475 samples from Scottish hospitalised and community cases collected between 1st November 2020 and 30th January 2021 were sequenced. We matched sequence data to clinical outcomes as the Alpha variant became dominant in Scotland and modelled the association between Alpha variant infection and severe disease using a 4-point scale of maximum severity by 28 days: 1. no respiratory support, 2. supplemental oxygen, 3. ventilation and 4. death.

Results

Our cumulative generalised linear mixed model analyses found evidence (cumulative odds ratio: 1.40, 95% CI: 1.02, 1.93) of a positive association between increased clinical severity and lineage (Alpha variant versus pre-Alpha variants).

Conclusions

The Alpha variant was associated with more severe clinical disease in the Scottish population than co-circulating lineages.

Introduction

The Alpha variant of SARS-CoV-2 (Pango lineage B.1.1.7) was first identified in the UK in September 2020 and was subsequently reported in 183 countries [1]. It is defined by 21 genomic mutations or deletions, including 8 characteristic changes within the spike gene (S1 Table) [2]. These are associated with increased ACE-2 receptor binding affinity and innate and adaptive immune evasion [3–6] compared to preceding lineages. The Alpha variant, the first variant of concern (VOC), was estimated to be 50–100% more transmissible than other lineages present at the time of its emergence [7], explaining the transient dominance of this lineage globally.

The presence of a spike gene deletion (Δ69–70) results in spike-gene target failure (SGTF) in real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) diagnostic assays and provided a useful proxy for the presence of the Alpha variant for epidemiological analysis during this time period [2]. Four large community analyses showed a positive association between the presence of SGTF and 28-day mortality, with hazard ratios of 1.55 (CI 1.39–1.72), 1.64 (CI 1.32–2.04), 1.67 (CI 1.34–2.09) and 1.73 (CI 1.41–2.13) [8–10]. Both SGTF (hazard ratios of 1.52 (CI 1.47–1.57), 1.62 (CI 1.48–1.78)) [11, 12] and confirmed Alpha variant infection (hazard ratios of 1.34 (CI 1.07–1.66) and 1.61 (CI 1.28–2.03) [12, 13] were associated with an increased risk of hospitalisation in community cases, and a smaller study of hospitalised patients found a greater risk of hypoxia at admission in those with confirmed Alpha variant infection [14]. In contrast, other smaller analyses of hospitalised patients found no association between confirmed Alpha variant infection and increased clinical severity based on a variety of indices [15–17]. Limited data are available on the full clinical course of disease with the Alpha variant in relation to co-circulating variants.

Understanding the clinical pattern of disease with new variants of concern is important for several reasons. Firstly, if a variant is more pathogenic than previous variants, this has implications for considering public health restrictions and the optimal functioning of health care systems. Secondly, large numbers of low- and middle-income countries still have less than 50% of their populations having been vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 [18]. A better understanding of a variant with increased severity is important in modelling the impact of unmitigated infection in these settings. A clear understanding of the behaviour of the Alpha variant, which emerged as a dominant variant in Scotland in the winter of 2020/21, is needed as a baseline to compare the clinical phenotype of variants of concern that have subsequently emerged. Post-Alpha variants, such as Omicron (B.1.1.529), have been shown to be able to evade vaccine-induced immunity and therefore have the potential to spread even in immunised populations [19], so a historical understanding of severity remains important, as it seems unlikely that SARS-CoV-2 infections will be brought under control in the near future.

We aimed to quantify the clinical features and rate of spread of Alpha variant infections in Scotland in a comprehensive national dataset. We used whole genome sequencing data to analyse patient presentations between 1st November 2020 and 30th January 2021 as the variant emerged in Scotland and used cumulative generalised additive models to compare 28-day maximum clinical severity for the Alpha variant against co-circulating lineages.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and approvals

We included all Scottish COG-UK pillar 1 samples sequenced at the MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research (CVR) and the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh (RIE) between 1st November 2020 and 30th January 2021. These samples derived from both hospitalised patients (59%) and community testing (41%).

Residual nucleic acid extracts derived from the nose-throat swabs of SARS-CoV-2 positive individuals whose diagnostic samples were submitted to the West of Scotland Specialist Virology Centre and Edinburgh Royal Infirmary Virus laboratory and were sequenced following ethical approvals from the West of Scotland Biorepository (16/WS/0207NHS) and the Lothian Biorepository (10/S1402/33). These samples were sequenced without consent following HTA legislation on consent exemption. Use of Scottish anonymised clinical data linked to virus genomic data without informed consent was granted by the Caldicott guardian for each site and by the Scottish Public Benefit and Privacy Panel (PBPP) for Health and Social Care (2122–0130).

Sequencing and bioinformatics

Sequencing was performed as part of the COG-UK consortium using amplicon-based next generation sequencing [20, 21]. Sequence alignment, lineage assignment and tree generation were performed using the COG-UK data pipeline (https://github.com/COG-UK/datapipe) and phylogenetic pipeline (https://github.com/cov-ert/phylopipe) with pangolin lineage assignment (https://github.com/cov-lineages/pangolin) [22]. Lineage assignments were performed on 18/03/2021 and phylogenetic analysis was performed using the COG-UK tree generated on 25/02/2021. Estimates of growth rates of major lineages in Scotland were calculated from time-resolved phylogenies for lineages B.1.1.7 (Alpha), B.177 and the sub-clades B.177.5, B.177.8, and another minor B.177 sub-clade (W.4). The estimates were carried out utilising sequences from November 2020 –March 2021 in BEAST (Bayesian Evolutionary Analysis by Sampling Trees) with an exponential growth rate population model, strict molecular clock model and TN93 with four gamma rate distribution categories. Each lineage was randomly subsampled to a maximum of 5 sequences per epiweek (resulting in 52 to 103 sequences per subsample, depending on the lineage), and 10 subsamples replicates analysed per lineage in a joint exponential growth rate population model.

Clinical data

Core demographic data (age, sex, partial postcode) were collected via linkage to electronic patient records at the 7 of 14 scottish health boards (covering 78% of the scottish population) for which we had clinical data access approval, and a full retrospective review of case notes was undertaken. Collected data included residence in a care home; occupation in care home or healthcare setting; admission to hospital; date of admission, discharge and/or death and maximum clinical severity at 28 days sample collection date via a 4-point ordinal scale (1. No respiratory support; 2. Supplemental low flow oxygen; 3. Invasive ventilation, non-invasive ventilation or high-flow nasal canula (IV/NIV/HFNO); 4. Death) as previously used in Volz et al 2020 and Thomson et al 2021 [23, 24].

Where available, PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) cycle threshold (Ct) and the PCR testing platform were recorded. Nosocomial COVID-19 was defined as a first positive PCR occurring greater than 48 hours following admission to hospital, individuals meeting this criterion were excluded from the study. Discharge status was followed up until 15th April 2021 for the hospital stay analysis. For the co-morbidity sub-analysis, delegated research ethics approval was granted for linkage to National Health Service (NHS) patient data by the Local Privacy and Advisory Committee at NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde. Cohorts and de-identified linked data were prepared by the West of Scotland Safe Haven at NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde.

Severity analyses

Four level severity data was analysed using cumulative (per the definition of Bürkner and Vuorre (2019)) generalised additive mixed models (GAMMs) with logit links, specifically, following Volz et al (2020) [23, 25]. We analysed three subsets of the data: 1. the full dataset, 2. the dataset excluding care home patients, and 3. exclusively the hospitalised population. Further details regarding these analyses are provided in S1 Appendix.

Ct analysis

Ct value was compared between Alpha variant and pre-Alpha variant infections for those patients where the TaqPath assay (Applied Biosystems) was used. This platform was used exclusively for this analysis because different platforms output systematically different Ct values, and this was the most frequently used in our dataset (n = 154, Alpha = 38, pre-Alpha = 116). We used a generalised additive model with a Gaussian error structure and identity link, and the same covariates used as in the severity analysis to model the Ct value. The model was fitted using the brms (v. 2.14.4) R package [26]. The presented model had no divergent transitions and effective sample sizes of over 200 for all parameters. The intercept of the model was given a t-distribution (location = 20, scale = 10, df = 3) prior, the fixed effect coefficients were given normal (mean = 0, standard deviation = 5) priors, random effects and spline standard deviations were given exponential (mean = 5) priors.

Hospital length of stay analysis

Hospital length of stay was compared for Alpha variant and pre-Alpha variant patients while controlling for age and sex using a Fine and Gray model competing risks regression using the crr function in the cmprsk (v. 2.2–10) R package [27, 28]. Nosocomial infections were excluded. In total, this analysis had 521 cases (Alpha = 187, pre-Alpha = 334), of which 4 were censored; 352 patients were discharged from hospital and 165 died.

Results

Emergence of the Alpha variant in Scotland

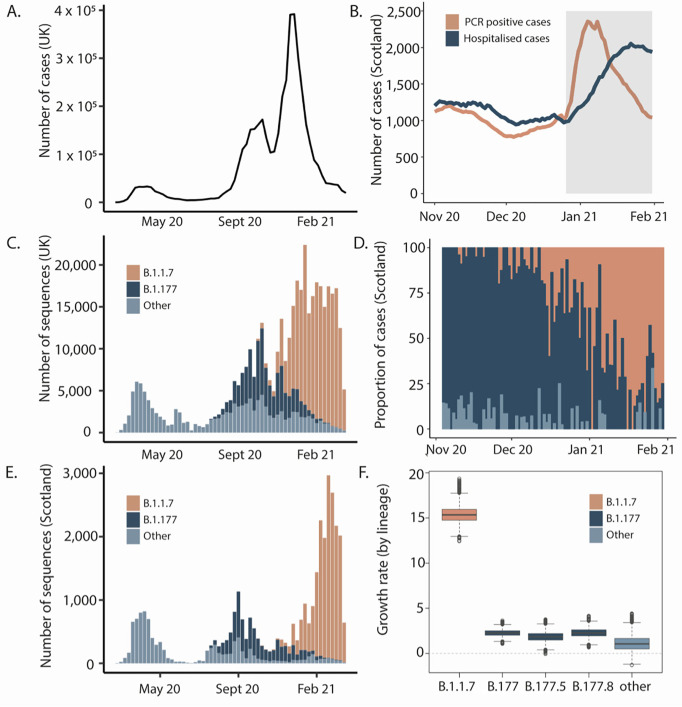

Between 01/11/2020 and 31/01/2021 1863 samples from individuals tested in pillar 1 facilities in Scotland underwent whole genome sequencing for SARS-CoV-2. Of these, 1475 (79%) could be linked to patient records from participating scottish health boards, and were included in the analysis. The contribution of patients infected with the Alpha variant increased over the course of the study, in line with dissemination across the UK during the study period (Fig 1A and 1B). At the time of data collection, two peaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection had occurred in the UK: the first (wave 1) in March 2020 [15] and the second in summer 2020 [29], both in association with hundreds of importations following travel to Central Europe [30]. The second peak incorporated two variant waves (waves 2 and 3), initially of B.1.177 (Fig 1C) and then B.1.1.7/Alpha, radiating from the South of England (Fig 1E). This Alpha variant “takeover” (Fig 1D) corresponded to a five-fold increase in growth rate on an epidemiological scale relative to pre-Alpha lineages (Fig 1F).

Fig 1. Introduction and growth of the Alpha variant (lineage B.1.1.7) in the UK, 2020/21.

A) Waves of SARS-CoV-2 confirmed cases in the UK. B) Seven-day rolling average of daily PCR positive cases (orange) and total number of patients hospitalised (dark blue) with COVID-19 in Scotland during the study period. Grey shaded area represents the period of lockdown beginning 26/12/2020. C) Variants in the UK. D) Proportion of cases by lineage in the clinical severity cohort. E) Variants in Scotland showing three distinct waves in winter and early spring 2020, summer 2020 and autumn/winter, attributed to the shifts from B1 and other variants (light blue) to B.1.177 (dark blue) and then B.1.1.7/Alpha (orange). Waves one and two closely mirror the broader UK situation as they are linked to both continental European and introductions from England. Wave three has a single origin in Kent so Scotland lags England in numbers of cases. F) Estimates of growth rates of major lineages in Scotland from time-resolved phylogenies. Estimates were carried out on a subsample of the named lineages using sequences from Scotland only from November 2020-March 2021 using BEAST and an exponential growth effective population size model.

Demographics of the clinical cohort

The age of the clinical cohort ranged from 0–105 years, (mean 66.8 years) and was slightly lower in the Alpha group (65.6 years vs. 67.2 years). Overall, 59.1% were female; this preponderance occurred in both subgroups and was higher in the Alpha subgroup (60.4% vs 58.6%). In the full cohort, 3.0% were care-home workers and 10.4% were NHS healthcare workers. 5.5% and 5.8% of those infected with the Alpha variant were care-home and other healthcare workers respectively, compared with 2.2% and 12.0% of those infected with pre-Alpha lineages. 12.9% of those in the Alpha subgroup were care-home residents, compared with 21.7% in pre-Alpha. There was also a difference in the proportion of cases admitted to Intensive Care Units: 6.3% of the Alpha group compared with 3.4% for pre-Alpha. Full details of the demographic data of the cohort can be found in Table 1 and full lineage assignments can be found in S2 Table.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of Scottish patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 by lineage.

| Overall Group (n = 1475) | B.1.1.7 (Alpha) (n = 364) | Other (Pre-Alpha) (n = 1111) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 66.8±20.8 | 65.6±20.6 | 67.2±20.8 | |||

| Range | 0–105 | 0–105 | 0–100 | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 604 | 40.9% | 144 | 39.6% | 460 | 41.4% |

| Female | 871 | 59.1% | 220 | 60.4% | 651 | 58.6% |

| Admitted to hospital | ||||||

| Yes | 876 | 59.4% | 238 | 65.4% | 638 | 57.4% |

| No | 599 | 40.6% | 126 | 34.6% | 473 | 42.6% |

| Care home worker | ||||||

| Yes | 44 | 3.0% | 20 | 5.5% | 24 | 2.2% |

| No | 1305 | 88.5% | 305 | 83.8% | 1000 | 90.0% |

| Unknown | 126 | 8.5% | 39 | 10.7% | 87 | 7.8% |

| Non-care home healthcare worker | ||||||

| Yes | 154 | 10.4% | 21 | 5.8% | 133 | 12.0% |

| No | 1193 | 80.9% | 305 | 83.8% | 888 | 79.9% |

| Unknown | 128 | 8.7% | 38 | 10.4% | 90 | 8.1% |

| Nursing home resident | ||||||

| Yes | 288 | 19.5% | 47 | 12.9% | 241 | 21.7% |

| No | 1187 | 80.5% | 317 | 87.1% | 870 | 78.3% |

| Unknown | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Diagnosis >48 hours post-admission | ||||||

| Yes | 346 | 23.5% | 46 | 12.6% | 300 | 27.0% |

| No | 1040 | 70.5% | 289 | 79.4% | 751 | 67.6% |

| Unknown | 89 | 6.0% | 29 | 8.0% | 60 | 5.4% |

| Travel outside Scotland | ||||||

| Yes | 1 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.1% |

| No | 317 | 21.5% | 20 | 5.5% | 297 | 26.7% |

| Unknown | 1157 | 78.4% | 302 | 94.5% | 813 | 73.2% |

| Immunosuppressed | ||||||

| Yes | 42 | 2.9% | 4 | 1.1% | 38 | 3.4% |

| No | 474 | 31.1% | 60 | 16.5% | 414 | 37.3% |

| Unknown | 959 | 65.0% | 300 | 82.4% | 659 | 59.3% |

| Visited Intensive Care Unit? | ||||||

| Yes | 61 | 4.1% | 23 | 6.3% | 38 | 3.4% |

| No | 1413 | 95.8% | 341 | 93.7% | 1072 | 96.5% |

| Unknown | 1 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.1% |

| Patient alive/deceased? | ||||||

| Alive | 1115 | 75.6% | 273 | 75.0% | 842 | 75.8% |

| Deceased | 360 | 24.4% | 91 | 25.0% | 269 | 24.2% |

Clinical severity analysis

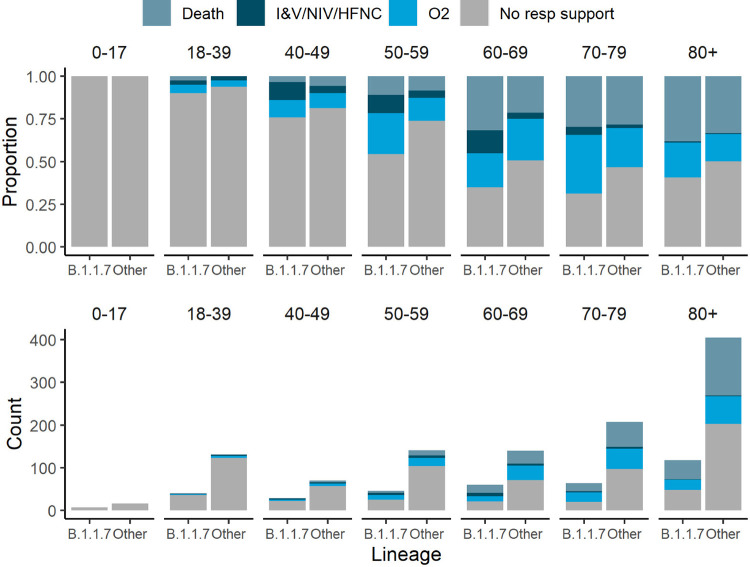

Within the clinical severity cohort there were 364 Alpha cases, 1030 B.1.177 cases, and 81 cases due to one of 19 other pre-Alpha lineages (Fig 2), of which 185 Alpha cases (51%) and 440 pre-Alpha cases (38%) received oxygen or died. Consistent with previous research comparing mortality and hospitalisation in SGTF detected by PCR versus absence of SGTF, we found that Alpha variant viruses were associated with more severe disease on average than those from other lineages circulating during the same time period. In the full dataset, we observed a positive association with severity (posterior median cumulative odds ratio: 1.40, 95% CI: 1.02–1.93). In both the subsets, excluding care-home patients or limiting to hospitalised patients only, the mean estimate of the increase in severity of the Alpha variant was smaller, and the variance in the posterior distribution higher likely due to the smaller sample sizes. Given this uncertainty, we cannot determine whether the association of the Alpha variant with severity in the populations corresponding to these subsets is the same as that in the population described by the full dataset, but in all cases, the most likely direction of the effect is positive. Comorbidity data were not available for the full dataset, a sub-analysis on those cases where it could be linked indicated that comorbidities did not substantially affect relative severity estimates (S3 Appendix). Model estimates from severity models from all subsets can be found in S3–S5 Tables.

Fig 2. Comparison of disease severity between the Alpha variant (B.1.1.7) and other lineages.

Clinical severity was measured on a four-level ordinal scale based on the level of respiratory support received for 1454 patients stratified by age group; death, invasive or non-invasive ventilatory support including high flow nasal cannulae (IV/NIV/HFNC), supplemental oxygen delivered by low flow mask devices or nasal cannulae, and no respiratory support.

Bernoulli models looking at sequential severity categories provided weak evidence that the proportional odds assumption of the cumulative logistic model was violated. The odds ratios for the no oxygen versus low flow oxygen, and low flow oxygen versus IV/NIV/HFNC were similar to those estimated under the cumulative model (posterior median odds ratio for no oxygen versus low flow oxygen: 1.77, CI: 1.12–2.80; posterior median odds ratio for low flow oxygen versus IV/NIV/HFNC: 1.26, CI: 0.43–3.67) but with correspondingly higher posterior variances given the smaller sample size. The odds ratios for the IV/NIV/HFNC versus death model suggested that the preponderance of evidence was in favour of Alpha infection associated with lower risk of death, conditional on having received IV, NIV or HFNC (posterior median odds ratio: 0.64, CI: 0.22–1.90). However, the credible intervals here are wide, given the sample size, and do include the estimated global effect. A similar but more extreme effect was observed for the effect of biological sex, with male sex being associated with more severe outcomes for the first two sequential category models (posterior median odds ratio for no oxygen versus low flow oxygen: 1.32, CI: 0.96–1.80; posterior median odds ratio for low flow oxygen versus IV/NIV/HFNC: 3.10, CI: 1.37–7.08), but withless severe outcomes for the last (posterior odds ratio for IV/NIV/HFNC vs death: 0.62, CI: 0.19–099). Given other research on the topic has consistently identified male sex as a risk factor, this potentially indicates the existence of an important unmeasured confounder only relevant for those requiring invasive ventilation, non-invasive ventilation or high flow nasal cannula oxygen.

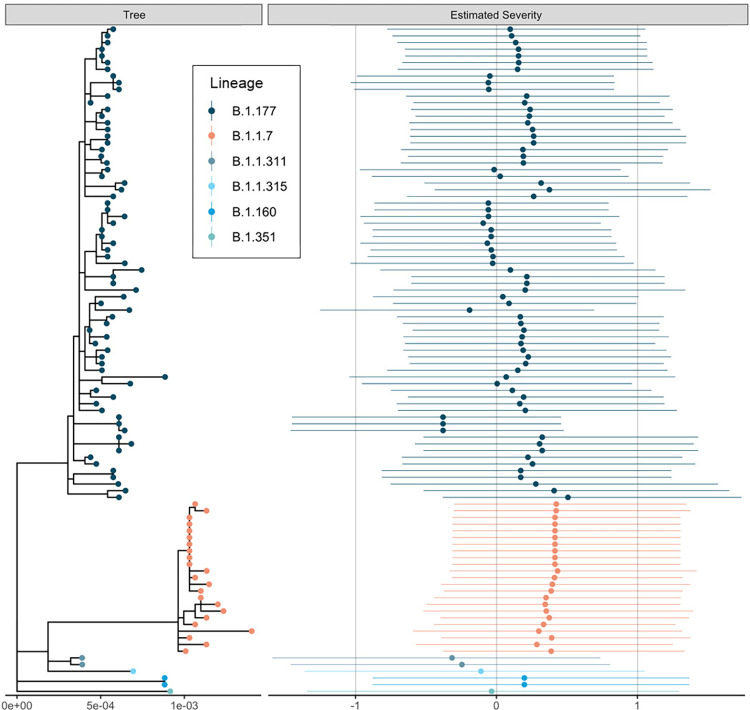

Estimates of the severity across the phylogeny are visible in Fig 3; see S2 Appendix for more discussion of this analysis. An analysis including comorbidities for the subset of patients where they were available implied that the inclusion of comorbidities had no impact on the results obtained, see S1 and S3 Appendices.

Fig 3. The estimated maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree and a measure of estimated severities of infection.

Estimated severities for each viral isolate are means and 95% credible intervals of the linear predictor change under infection with that viral genotype from the phylogenetic random effect in the cumulative severity model under a Brownian motion model of evolution. This model constrains genetically identical isolates to have identical effects, so changes should be interpreted across the phylogeny rather than between closely related isolates which necessarily have similar estimated severities. The dataset was downsampled to 100 random samples for this figure to aid readability. Figure was generated using ggtree [31].

We also found that the Alpha variant was associated with lower Ct values than infection with pre-Alpha variants (posterior median Ct change: -2.46, 95% CI: -4.22 - -0.70) as previously observed [8]. Model estimates for all parameters can be found in S6 Table.

We found no evidence that the Alpha variant was associated with longer hospital stays after controlling for age and sex (HR: -0.02; 95% CI: -0.23–0.20; p = 0.89).

Discussion

In this analysis of hospitalised and community patients with Alpha variant and pre-Alpha variant SARS-CoV-2 infection, carried out as the Alpha variant became dominant in Scotland, we provide evidence of increased clinical severity associated with this variant at this time, after adjusting for age, sex, geography and calendar time, as well as testing for sensitivity to number of comorbidities. This was observed across all adult age groups, incorporating the spectrum of COVID-19 disease; from no requirement for supportive care, to supplemental oxygen requirement, the need for invasive or non-invasive ventilation, and to death. This analysis is the first to assess the full clinical severity spectrum of confirmed Alpha variant infection in both community and hospitalised cases in relation to other prevalent lineages circulating during the same time period.

Our study supports the community testing analyses that have reported an increased 28-day mortality associated with SGTF as a proxy for Alpha variant status [8–10]. Smaller studies found no effect of lineage on various measures of severity [15–17], but these were studies of patients already admitted to hospital and therefore would not pick up the granular detail of increasing disease severity resulting in a need for increasing levels of respiratory support and consequently admission to hospital.

The association between higher viral load, higher transmission and lineage may reflect changes in the biology of the virus; for example, the Alpha variant asparagine (N) to tyrosine (Y) mutation at position 501 of the spike protein receptor binding domain (RBD) was associated with an increase in binding affinity to the human ACE2 receptor [32]. In addition, a deletion at position 69–70 may have increased virus infectivity [33]. The P681H mutation found at the furin cleavage site is associated with more efficient furin cleavage, enhancing cell entry [34]. An alternative explanation for the higher viral loads observed in Alpha variant infection may be that clinical presentation occurs earlier in the illness. Further modelling, animal experiments and studies in healthy volunteers may help to unravel the mechanisms behind this phenomenon.

Our data indicate an association between the Alpha variant and an increased risk of requiring supplemental oxygen and ventilation compared to per-Alpha variants. These two factors are critical determinants of healthcare capacity during a period of high incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and this illustrates the importance for countries, in particular those with less robust health care systems and lower vaccination rates of factoring the requirement for supportive treatment into models of clinical severity and pandemic response decision planning for future SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. This granular analysis of disease severity based on genomic confirmation of diagnosis should be used as a baseline study for clinical severity analysis of the inevitable future variants of concern.

There are some limitations to our study. Our dataset is drawn from first-line local NHS diagnostic (Pillar 1) testing which over-represents patients presenting for hospital care (59%) while those sampled in the community represented 41% of the dataset. The effect of working in the healthcare sector on severity, driven by systematically different exposures faced by frontline caregivers, could not be adjusted for, due to incompleteness of the data regarding this variable. Further, the analysis dataset employed a non-standardised approach to sampling across the study period as sequencing was carried out both as systematic randomised national surveillance and sampling following outbreaks of interest. Additionally, we did not have information about the vaccination status of the individuals in the study. However, our inability to adjust for this variable is not likely to have had a great impact on our conclusions, as, at the time of the study, the vaccination campaign had recently begun, with only over 75 year olds and high-risk groups eligible. Finally, the cumulative model used and the usage of a single (not location varying) spine for the effect of time in this analysis assumes a homogenous application of therapeutic intervention across the population. Despite these limitations, our results remain consistent with previous work on the mortality of Alpha, and this study provides new information regarding differences in infection severity.

In summary, the Alpha variant was found to be associated with a rapid increase in COVID-19 cases in Scotland in the winter of 2020/21, and an increased risk of severe infection requiring supportive care. This has implications for planning for future variant driven waves of infection, especially in countries with low vaccine uptake or if variants evolve with significant vaccine-escape. Our study has shown the value of the collection of higher resolution patient outcome data linked to genetic sequences when looking for clinically relevant differences between viral variants.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all NHS staff that looked after patients during the COVID-19 pandemic in Scotland. The authors would like to acknowledge that this work uses data provided by patients and collected by the National Health Service (NHS) as part of their care and support. The authors would also like to acknowledge the work of the West of Scotland Safe Haven team in supporting extractions and linkage to de-identified NHS patient datasets. The authors would also like to acknowledge the work of the COG-UK consortium whose members are listed below:

Dr Samuel C Robson PhD 13, 84, Dr Thomas R Connor PhD 11, 74, Prof Nicholas J Loman PhD 43, Dr Tanya Golubchik PhD 5, Dr Rocio T Martinez Nunez PhD 46, Dr David Bonsall PhD 5, Prof Andrew Rambaut DPhil 104, Dr Luke B Snell MSc, MBBS 12, Rich Livett MSc 116, Dr Catherine Ludden PhD 20, 70, Dr Sally Corden PhD 74, Dr Eleni Nastouli FRCPath 96, 95, 30, Dr Gaia Nebbia PhD, FRCPath 12, Ian Johnston BSc 116, Prof Katrina Lythgoe PhD 5, Dr M. Estee Torok FRCP 19, 20, Prof Ian G Goodfellow PhD 24, Dr Jacqui A Prieto PhD 97, 82, Dr Kordo Saeed MD, FRCPath 97, 83, Dr David K Jackson PhD 116, Dr Catherine Houlihan PhD 96, 94, Dr Dan Frampton PhD 94, 95, Dr William L Hamilton PhD 19, Dr Adam A Witney PhD 41, Dr Giselda Bucca PhD 101, Dr Cassie F Pope PhD40, 41, Dr Catherine Moore PhD 74, Prof Emma C Thomson PhD, FRCP 53, Dr Teresa Cutino-Moguel PhD 2, Dr Ewan M Harrison PhD 116, 102, Prof Colin P Smith PhD 101, Fiona Rogan BSc 77, Shaun M Beckwith MSc 6, Abigail Murray Degree 6, Dawn Singleton HNC 6, Dr Kirstine Eastick PhD, FRCPath 37, Dr Liz A Sheridan PhD 98, Paul Randell MSc, PgD 99, Dr Leigh M Jackson PhD 105, Dr Cristina V Ariani PhD 116, Dr Sónia Gonçalves PhD 116, Dr Derek J Fairley PhD 3, 77, Prof Matthew W Loose PhD 18, Joanne Watkins MSc 74, Dr Samuel Moses MD 25, 106, Dr Sam Nicholls PhD 43, Dr Matthew Bull PhD 74, Dr Roberto Amato PhD 116, Prof Darren L Smith PhD 36, 65, 66, Prof David M Aanensen PhD 14, 116, Dr Jeffrey C Barrett PhD 116, Dr Beatrix Kele PhD 2, Dr Dinesh Aggarwal MRCP20, 116, 70, Dr James G Shepherd MBCHB, MRCP 53, Dr Martin D Curran PhD 71, Dr Surendra Parmar PhD 71, Dr Matthew D Parker PhD 109, Dr Catryn Williams PhD 74, Dr Sharon Glaysher PhD 68, Dr Anthony P Underwood PhD 14, 116, Dr Matthew Bashton PhD 36, 65, Dr Nicole Pacchiarini PhD 74, Dr Katie F Loveson PhD 84, Matthew Byott MSc 95, 96, Dr Alessandro M Carabelli PhD 20, Dr Kate E Templeton PhD 56, 104, Prof Sharon J Peacock PhD 20, 70*, Dr Thushan I de Silva PhD 109, Dr Dennis Wang PhD 109, Dr Cordelia F Langford PhD 116, John Sillitoe BEng 116, Prof Rory N Gunson PhD, FRCPath 55, Dr Simon Cottrell PhD 74, Dr Justin O’Grady PhD 75, 103, Prof Dominic Kwiatkowski PhD 116, 108, Dr Patrick J Lillie PhD, FRCP 37, Dr Nicholas Cortes MBCHB 33, Dr Nathan Moore MBCHB 33, Dr Claire Thomas DPhil 33, Phillipa J Burns MSc, DipRCPath 37, Dr Tabitha W Mahungu FRCPath 80, Steven Liggett BSc 86, Angela H Beckett MSc 13, 81, Prof Matthew TG Holden PhD 73, Dr Lisa J Levett PhD 34, Dr Husam Osman PhD 70, 35, Dr Mohammed O Hassan-Ibrahim PhD, FRCPath 99, Dr David A Simpson PhD 77, Dr Meera Chand PhD 72, Prof Ravi K Gupta PhD 102, Prof Alistair C Darby PhD 107, Prof Steve Paterson PhD 107, Prof Oliver G Pybus DPhil 23, Dr Erik M Volz PhD 39, Prof Daniela de Angelis PhD 52, Prof David L Robertson PhD 53, Dr Andrew J Page PhD 75, Dr Inigo Martincorena PhD 116, Dr Louise Aigrain PhD 116, Dr Andrew R Bassett PhD 116, Dr Nick Wong DPhil, MRCP, FRCPath 50, Dr Yusri Taha MD, PhD 89, Michelle J Erkiert BA 99, Dr Michael H Spencer Chapman MBBS 116, 102, Dr Rebecca Dewar PhD 56, Martin P McHugh MSc 56, 111, Siddharth Mookerjee MPH 38, 57, Stephen Aplin 97, Matthew Harvey 97, Thea Sass 97, Dr Helen Umpleby FRCP 97, Helen Wheeler 97, Dr James P McKenna PhD 3, Dr Ben Warne MRCP 9, Joshua F Taylor MSc 22, Yasmin Chaudhry BSc 24, Rhys Izuagbe 24, Dr Aminu S Jahun PhD 24, Dr Gregory R Young PhD 36, 65, Dr Claire McMurray PhD 43, Dr Clare M McCann PhD 65, 66, Dr Andrew Nelson PhD 65, 66, Scott Elliott 68, Hannah Lowe MSc 25, Dr Anna Price PhD 11, Matthew R Crown BSc 65, Dr Sara Rey PhD 74, Dr Sunando Roy PhD 96, Dr Ben Temperton PhD 105, Dr Sharif Shaaban PhD 73, Dr Andrew R Hesketh PhD 101, Dr Kenneth G Laing PhD41, Dr Irene M Monahan PhD 41, Dr Judith Heaney PhD 95, 96, 34, Dr Emanuela Pelosi FRCPath 97, Siona Silviera MSc 97, Dr Eleri Wilson-Davies MD, FRCPath 97, Dr Helen Fryer PhD 5, Dr Helen Adams PhD 4, Dr Louis du Plessis PhD 23, Dr Rob Johnson PhD 39, Dr William T Harvey PhD 53, 42, Dr Joseph Hughes PhD 53, Dr Richard J Orton PhD 53, Dr Lewis G Spurgin PhD 59, Dr Yann Bourgeois PhD 81, Dr Chris Ruis PhD 102, Áine O’Toole MSc 104, Marina Gourtovaia MSc 116, Dr Theo Sanderson PhD 116, Dr Christophe Fraser PhD 5, Dr Jonathan Edgeworth PhD, FRCPath 12, Prof Judith Breuer MD 96, 29, Dr Stephen L Michell PhD 105, Prof John A Todd PhD 115, Michaela John BSc 10, Dr David Buck PhD 115, Dr Kavitha Gajee MBBS, FRCPath 37, Dr Gemma L Kay PhD 75, David Heyburn 74, Dr Themoula Charalampous PhD 12, 46, Adela Alcolea-Medina 32, 112, Katie Kitchman BSc 37, Prof Alan McNally PhD 43, 93, David T Pritchard MSc, CSci 50, Dr Samir Dervisevic FRCPath 58, Dr Peter Muir PhD 70, Dr Esther Robinson PhD 70, 35, Dr Barry B Vipond PhD 70, Newara A Ramadan MSc, CSci, FIBMS 78, Dr Christopher Jeanes MBBS 90, Danni Weldon BSc 116, Jana Catalan MSc 118, Neil Jones MSc 118, Dr Ana da Silva Filipe PhD 53, Dr Chris Williams MBBS 74, Marc Fuchs BSc 77, Dr Julia Miskelly PhD 77, Dr Aaron R Jeffries PhD 105, Karen Oliver BSc 116, Dr Naomi R Park PhD 116, Amy Ash BSc 1, Cherian Koshy MSc, CSci, FIBMS 1, Magdalena Barrow 7, Dr Sarah L Buchan PhD 7, Dr Anna Mantzouratou PhD 7, Dr Gemma Clark PhD 15, Dr Christopher W Holmes PhD 16, Sharon Campbell MSc 17, Thomas Davis MSc 21, Ngee Keong Tan MSc 22, Dr Julianne R Brown PhD 29, Dr Kathryn A Harris PhD 29, 2, Stephen P Kidd MSc 33, Dr Paul R Grant PhD 34, Dr Li Xu-McCrae PhD 35, Dr Alison Cox PhD 38, 63, Pinglawathee Madona 38, 63, Dr Marcus Pond PhD 38, 63, Dr Paul A Randell MBBCh 38, 63, Karen T Withell FIBMS 48, Cheryl Williams MSc 51, Dr Clive Graham MD 60, Rebecca Denton-Smith BSc 62, Emma Swindells BSc 62, Robyn Turnbull BSc 62, Dr Tim J Sloan PhD 67, Dr Andrew Bosworth PhD 70, 35, Stephanie Hutchings 70, Hannah M Pymont MSc 70, Dr Anna Casey PhD 76, Dr Liz Ratcliffe PhD 76, Dr Christopher R Jones PhD 79, 105, Dr Bridget A Knight PhD 79, 105, Dr Tanzina Haque PhD, FRCPath 80, Dr Jennifer Hart MRCP 80, Dr Dianne Irish-Tavares FRCPath 80, Eric Witele MSc 80, Craig Mower BA 86, Louisa K Watson DipHE 86, Jennifer Collins BSc 89, Gary Eltringham BSc 89, Dorian Crudgington 98, Ben Macklin 98, Prof Miren Iturriza-Gomara PhD 107, Dr Anita O Lucaci PhD 107, Dr Patrick C McClure PhD 113, Matthew Carlile BSc 18, Dr Nadine Holmes PhD 18, Dr Christopher Moore PhD 18, Dr Nathaniel Storey PhD 29, Dr Stefan Rooke PhD 73, Dr Gonzalo Yebra PhD 73, Dr Noel Craine DPhil 74, Malorie Perry MSc 74, Dr Nabil-Fareed Alikhan PhD 75, Dr Stephen Bridgett PhD 77, Kate F Cook MScR 84, Christopher Fearn MSc 84, Dr Salman Goudarzi PhD 84, Prof Ronan A Lyons MD 88, Dr Thomas Williams MD 104, Dr Sam T Haldenby PhD 107, Jillian Durham BSc 116, Dr Steven Leonard PhD 116, Robert M Davies MA (Cantab) 116, Dr Rahul Batra MD 12, Beth Blane BSc 20, Dr Moira J Spyer PhD 30, 95, 96, Perminder Smith MSc 32, 112, Mehmet Yavus 85, 109, Dr Rachel J Williams PhD 96, Dr Adhyana IK Mahanama MD 97, Dr Buddhini Samaraweera MD 97, Sophia T Girgis MSc 102, Samantha E Hansford CSci 109, Dr Angie Green PhD 115, Dr Charlotte Beaver PhD 116, Katherine L Bellis 116, 102, Matthew J Dorman 116, Sally Kay 116, Liam Prestwood 116, Dr Shavanthi Rajatileka PhD 116, Dr Joshua Quick PhD 43, Radoslaw Poplawski BSc 43, Dr Nicola Reynolds PhD 8, Andrew Mack MPhil 11, Dr Arthur Morriss PhD 11, Thomas Whalley BSc 11, Bindi Patel BSc 12, Dr Iliana Georgana PhD 24, Dr Myra Hosmillo PhD 24, Malte L Pinckert MPhil 24, Dr Joanne Stockton PhD 43, Dr John H Henderson PhD 65, Amy Hollis HND 65, Dr William Stanley PhD 65, Dr Wen C Yew PhD 65, Dr Richard Myers PhD 72, Dr Alicia Thornton PhD 72, Alexander Adams BSc 74, Tara Annett BSc 74, Dr Hibo Asad PhD 74, Alec Birchley MSc 74, Jason Coombes BSc 74, Johnathan M Evans MSc 74, Laia Fina 74, Bree Gatica-Wilcox MPhil 74, Lauren Gilbert 74, Lee Graham BSc 74, Jessica Hey BSc 74, Ember Hilvers MPH 74, Sophie Jones MSc 74, Hannah Jones 74, Sara Kumziene-Summerhayes MSc 74, Dr Caoimhe McKerr PhD 74, Jessica Powell BSc 74, Georgia Pugh 74, Sarah Taylor 74, Alexander J Trotter MRes 75, Charlotte A Williams BSc 96, Leanne M Kermack MSc 102, Benjamin H Foulkes MSc 109, Marta Gallis MSc 109, Hailey R Hornsby MSc 109, Stavroula F Louka MSc 109, Dr Manoj Pohare PhD 109, Paige Wolverson MSc 109, Peijun Zhang MSc 109, George MacIntyre-Cockett BSc 115, Amy Trebes MSc 115, Dr Robin J Moll PhD 116, Lynne Ferguson MSc 117, Dr Emily J Goldstein PhD 117, Dr Alasdair Maclean PhD 117, Dr Rachael Tomb PhD 117, Dr Igor Starinskij MSc, MRCP 53, Laura Thomson BSc 5, Joel Southgate MSc 11, 74, Dr Moritz UG Kraemer DPhil 23, Dr Jayna Raghwani PhD 23, Dr Alex E Zarebski PhD 23, Olivia Boyd MSc 39, Lily Geidelberg MSc 39, Dr Chris J Illingworth PhD 52, Dr Chris Jackson PhD 52, Dr David Pascall PhD 52, Dr Sreenu Vattipally PhD 53, Timothy M Freeman MPhil 109, Dr Sharon N Hsu PhD 109, Dr Benjamin B Lindsey MRCP 109, Dr Keith James PhD 116, Kevin Lewis 116, Gerry Tonkin-Hill 116, Dr Jaime M Tovar-Corona PhD 116, MacGregor Cox MSci 20, Dr Khalil Abudahab PhD 14, 116, Mirko Menegazzo 14, Ben EW Taylor MEng 14, 116, Dr Corin A Yeats PhD 14, Afrida Mukaddas BTech 53, Derek W Wright MSc 53, Dr Leonardo de Oliveira Martins PhD 75, Dr Rachel Colquhoun DPhil 104, Verity Hill 104, Dr Ben Jackson PhD 104, Dr JT McCrone PhD 104, Dr Nathan Medd PhD 104, Dr Emily Scher PhD 104, Jon-Paul Keatley 116, Dr Tanya Curran PhD 3, Dr Sian Morgan FRCPath 10, Prof Patrick Maxwell PhD 20, Prof Ken Smith PhD 20, Dr Sahar Eldirdiri MBBS, MSc, FRCPath 21, Anita Kenyon MSc 21, Prof Alison H Holmes MD 38, 57, Dr James R Price PhD 38, 57, Dr Tim Wyatt PhD 69, Dr Alison E Mather PhD 75, Dr Timofey Skvortsov PhD 77, Prof John A Hartley PhD 96, Prof Martyn Guest PhD 11, Dr Christine Kitchen PhD 11, Dr Ian Merrick PhD 11, Robert Munn BSc 11, Dr Beatrice Bertolusso Degree 33, Dr Jessica Lynch MBCHB 33, Dr Gabrielle Vernet MBBS 33, Stuart Kirk MSc 34, Dr Elizabeth Wastnedge MD 56, Dr Rachael Stanley PhD 58, Giles Idle 64, Dr Declan T Bradley PhD 69, 77, Nicholas F Killough MSc 69, Dr Jennifer Poyner MD 79, Matilde Mori BSc 110, Owen Jones BSc 11, Victoria Wright BSc 18, Ellena Brooks MA 20, Carol M Churcher BSc 20, Dr Laia Delgado Callico PhD 20, Mireille Fragakis HND 20, Dr Katerina Galai PhD 20, 70, Dr Andrew Jermy PhD 20, Sarah Judges BA 20, Anna Markov BSc 20, Georgina M McManus BSc 20, Kim S Smith 20, Peter M D Thomas-McEwen MSc 20, Dr Elaine Westwick PhD 20, Dr Stephen W Attwood PhD 23, Dr Frances Bolt PhD 38, 57, Dr Alisha Davies PhD 74, Elen De Lacy MPH 74, Fatima Downing 74, Sue Edwards 74, Lizzie Meadows MA 75, Sarah Jeremiah MSc 97, Dr Nikki Smith PhD 109, Luke Foulser 116, Amita Patel BSc 12, Dr Louise Berry PhD 15, Dr Tim Boswell PhD 15, Dr Vicki M Fleming PhD 15, Dr Hannah C Howson-Wells PhD 15, Dr Amelia Joseph PhD 15, Manjinder Khakh 15, Dr Michelle M Lister PhD 15, Paul W Bird MSc, MRes 16, Karlie Fallon 16, Thomas Helmer 16, Dr Claire L McMurray PhD 16, Mina Odedra BSc 16, Jessica Shaw BSc 16, Dr Julian W Tang PhD 16, Nicholas J Willford MSc 16, Victoria Blakey BSc 17, Dr Veena Raviprakash MD 17, Nicola Sheriff BSc 17, Lesley-Anne Williams BSc 17, Theresa Feltwell MSc 20, Dr Luke Bedford PhD 26, Dr James S Cargill PhD 27, Warwick Hughes MSc 27, Dr Jonathan Moore MD 28, Susanne Stonehouse BSc 28, Laura Atkinson MSc 29, Jack CD Lee MSc 29, Dr Divya Shah PhD 29, Natasha Ohemeng-Kumi MSc 32, 112, John Ramble MSc 32, 112, Jasveen Sehmi MSc 32, 112, Dr Rebecca Williams BMBS 33, Wendy Chatterton MSc 34, Monika Pusok MSc 34, William Everson MSc 37, Anibolina Castigador IBMS HCPC 44, Emily Macnaughton FRCPath 44, Dr Kate El Bouzidi MRCP 45, Dr Temi Lampejo FRCPath 45, Dr Malur Sudhanva FRCPath 45, Cassie Breen BSc 47, Dr Graciela Sluga MD, MSc 48, Dr Shazaad SY Ahmad MSc 49, 70, Dr Ryan P George PhD 49, Dr Nicholas W Machin MSc 49, 70, Debbie Binns BSc 50, Victoria James BSc 50, Dr Rachel Blacow MBCHB 55, Dr Lindsay Coupland PhD 58, Dr Louise Smith PhD 59, Dr Edward Barton MD 60, Debra Padgett BSc 60, Garren Scott BSc 60, Dr Aidan Cross MBCHB 61, Dr Mariyam Mirfenderesky FRCPath 61, Jane Greenaway MSc 62, Kevin Cole 64, Phillip Clarke 67, Nichola Duckworth 67, Sarah Walsh 67, Kelly Bicknell 68, Robert Impey MSc 68, Dr Sarah Wyllie PhD 68, Richard Hopes 70, Dr Chloe Bishop PhD 72, Dr Vicki Chalker PhD 72, Dr Ian Harrison PhD 72, Laura Gifford MSc 74, Dr Zoltan Molnar PhD 77, Dr Cressida Auckland FRCPath 79, Dr Cariad Evans PhD 85, 109, Dr Kate Johnson PhD 85, 109, Dr David G Partridge FRCP, FRCPath 85, 109, Dr Mohammad Raza PhD 85, 109, Paul Baker MD 86, Prof Stephen Bonner PhD 86, Sarah Essex 86, Leanne J Murray 86, Andrew I Lawton MSc 87, Dr Shirelle Burton-Fanning MD 89, Dr Brendan AI Payne MD 89, Dr Sheila Waugh MD 89, Andrea N Gomes MSc 91, Maimuna Kimuli MSc 91, Darren R Murray MSc 91, Paula Ashfield MSc 92, Dr Donald Dobie MBCHB 92, Dr Fiona Ashford PhD 93, Dr Angus Best PhD 93, Dr Liam Crawford PhD 93, Dr Nicola Cumley PhD 93, Dr Megan Mayhew PhD 93, Dr Oliver Megram PhD 93, Dr Jeremy Mirza PhD 93, Dr Emma Moles-Garcia PhD 93, Dr Benita Percival PhD 93, Megan Driscoll BSc 96, Leah Ensell BSc 96, Dr Helen L Lowe PhD 96, Laurentiu Maftei BSc 96, Matteo Mondani MSc 96, Nicola J Chaloner BSc 99, Benjamin J Cogger BSc 99, Lisa J Easton MSc 99, Hannah Huckson BSc 99, Jonathan Lewis MSc, PgD, FIBMS 99, Sarah Lowdon BSc 99, Cassandra S Malone MSc 99, Florence Munemo BSc 99, Manasa Mutingwende MSc 99, Roberto Nicodemi BSc 99, Olga Podplomyk FD 99, Thomas Somassa BSc 99, Dr Andrew Beggs PhD 100, Dr Alex Richter PhD 100, Claire Cormie 102, Joana Dias MSc 102, Sally Forrest BSc 102, Dr Ellen E Higginson PhD 102, Mailis Maes MPhil 102, Jamie Young BSc 102, Dr Rose K Davidson PhD 103, Kathryn A Jackson MSc 107, Dr Alexander J Keeley MRCP 109, Prof Jonathan Ball PhD 113, Timothy Byaruhanga MSc 113, Dr Joseph G Chappell PhD 113, Jayasree Dey MSc 113, Jack D Hill MSc 113, Emily J Park MSc 113, Arezou Fanaie MSc 114, Rachel A Hilson MSc 114, Geraldine Yaze MSc 114, Stephanie Lo 116, Safiah Afifi BSc 10, Robert Beer BSc 10, Joshua Maksimovic FD 10, Kathryn McCluggage Masters 10, Karla Spellman FD 10, Catherine Bresner BSc 11, William Fuller BSc 11, Dr Angela Marchbank BSc 11, Trudy Workman HNC 11, Dr Ekaterina Shelest PhD 13, 81, Dr Johnny Debebe PhD 18, Dr Fei Sang PhD 18, Dr Sarah Francois PhD 23, Bernardo Gutierrez MSc 23, Dr Tetyana I Vasylyeva DPhil 23, Dr Flavia Flaviani PhD 31, Dr Manon Ragonnet-Cronin PhD 39, Dr Katherine L Smollett PhD 42, Alice Broos BSc 53, Daniel Mair BSc 53, Jenna Nichols BSc 53, Dr Kyriaki Nomikou PhD 53, Dr Lily Tong PhD 53, Ioulia Tsatsani MSc 53, Prof Sarah O’Brien PhD 54, Prof Steven Rushton PhD 54, Dr Roy Sanderson PhD 54, Dr Jon Perkins MBCHB 55, Seb Cotton MSc 56, Abbie Gallagher BSc 56, Dr Elias Allara MD, PhD 70, 102, Clare Pearson MSc 70, 102, Dr David Bibby PhD 72, Dr Gavin Dabrera PhD 72, Dr Nicholas Ellaby PhD 72, Dr Eileen Gallagher PhD 72, Dr Jonathan Hubb PhD 72, Dr Angie Lackenby PhD 72, Dr David Lee PhD 72, Nikos Manesis 72, Dr Tamyo Mbisa PhD 72, Dr Steven Platt PhD 72, Katherine A Twohig 72, Dr Mari Morgan PhD 74, Alp Aydin MSci 75, David J Baker BEng 75, Dr Ebenezer Foster-Nyarko PhD 75, Dr Sophie J Prosolek PhD 75, Steven Rudder 75, Chris Baxter BSc 77, Sílvia F Carvalho MSc 77, Dr Deborah Lavin PhD 77, Dr Arun Mariappan PhD 77, Dr Clara Radulescu PhD 77, Dr Aditi Singh PhD 77, Miao Tang MD 77, Helen Morcrette BSc 79, Nadua Bayzid BSc 96, Marius Cotic MSc 96, Dr Carlos E Balcazar PhD 104, Dr Michael D Gallagher PhD 104, Dr Daniel Maloney PhD 104, Thomas D Stanton BSc 104, Dr Kathleen A Williamson PhD 104, Dr Robin Manley PhD 105, Michelle L Michelsen BSc 105, Dr Christine M Sambles PhD 105, Dr David J Studholme PhD 105, Joanna Warwick-Dugdale BSc 105, Richard Eccles MSc 107, Matthew Gemmell MSc 107, Dr Richard Gregory PhD 107, Dr Margaret Hughes PhD 107, Charlotte Nelson MSc 107, Dr Lucille Rainbow PhD 107, Dr Edith E Vamos PhD 107, Hermione J Webster BSc 107, Dr Mark Whitehead PhD 107, Claudia Wierzbicki BSc 107, Dr Adrienn Angyal PhD 109, Dr Luke R Green PhD 109, Dr Max Whiteley PhD 109, Emma Betteridge BSc 116, Dr Iraad F Bronner PhD 116, Ben W Farr BSc 116, Scott Goodwin MSc 116, Dr Stefanie V Lensing PhD 116, Shane A McCarthy 116, 102, Dr Michael A Quail PhD 116, Diana Rajan MSc 116, Dr Nicholas M Redshaw PhD 116, Carol Scott 116, Lesley Shirley MSc 116, Scott AJ Thurston BSc 116, Dr Will Rowe PhD43, Amy Gaskin MSc 74, Dr Thanh Le-Viet PhD 75, James Bonfield BSc 116, Jennifier Liddle 116 and Andrew Whitwham BSc 116

1 Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospitals NHS Trust, 2 Barts Health NHS Trust, 3 Belfast Health & Social Care Trust, 4 Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board, 5 Big Data Institute, Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, 6 Blackpool Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, 7 Bournemouth University, 8 Cambridge Stem Cell Institute, University of Cambridge, 9 Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, 10 Cardiff and Vale University Health Board, 11 Cardiff University, 12 Centre for Clinical Infection and Diagnostics Research, Department of Infectious Diseases, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, 13 Centre for Enzyme Innovation, University of Portsmouth, 14 Centre for Genomic Pathogen Surveillance, University of Oxford, 15 Clinical Microbiology Department, Queens Medical Centre, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, 16 Clinical Microbiology, University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust, 17 County Durham and Darlington NHS Foundation Trust, 18 Deep Seq, School of Life Sciences, Queens Medical Centre, University of Nottingham, 19 Department of Infectious Diseases and Microbiology, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, 20 Department of Medicine, University of Cambridge, 21 Department of Microbiology, Kettering General Hospital, 22 Department of Microbiology, South West London Pathology, 23 Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, 24 Division of Virology, Department of Pathology, University of Cambridge, 25 East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust, 26 East Suffolk and North Essex NHS Foundation Trust, 27 East Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust, 28 Gateshead Health NHS Foundation Trust, 29 Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust, 30 Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health (GOS ICH), University College London (UCL), 31 Guy’s and St. Thomas’ Biomedical Research Centre, 32 Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, 33 Hampshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, 34 Health Services Laboratories, 35 Heartlands Hospital, Birmingham, 36 Hub for Biotechnology in the Built Environment, Northumbria University, 37 Hull University Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, 38 Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, 39 Imperial College London, 40 Infection Care Group, St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, 41 Institute for Infection and Immunity, St George’s University of London, 42 Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health & Comparative Medicine, 43 Institute of Microbiology and Infection, University of Birmingham, 44 Isle of Wight NHS Trust, 45 King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, 46 King’s College London, 47 Liverpool Clinical Laboratories, 48 Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust, 49 Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, 50 Microbiology Department, Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust, 51 Microbiology, Royal Oldham Hospital, 52 MRC Biostatistics Unit, University of Cambridge, 53 MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research, 54 Newcastle University, 55 NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, 56 NHS Lothian, 57 NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in HCAI and AMR, Imperial College London, 58 Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, 59 Norfolk County Council, 60 North Cumbria Integrated Care NHS Foundation Trust, 61 North Middlesex University Hospital NHS Trust, 62 North Tees and Hartlepool NHS Foundation Trust, 63 North West London Pathology, 64 Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, 65 Northumbria University, 66 NU-OMICS, Northumbria University, 67 Path Links, Northern Lincolnshire and Goole NHS Foundation Trust, 68 Portsmouth Hospitals University NHS Trust, 69 Public Health Agency, Northern Ireland, 70 Public Health England, 71 Public Health England, Cambridge, 72 Public Health England, Colindale, 73 Public Health Scotland, 74 Public Health Wales, 75 Quadram Institute Bioscience, 76 Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham, 77 Queen’s University Belfast, 78 Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals, 79 Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust, 80 Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, 81 School of Biological Sciences, University of Portsmouth, 82 School of Health Sciences, University of Southampton, 83 School of Medicine, University of Southampton, 84 School of Pharmacy & Biomedical Sciences, University of Portsmouth, 85 Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, 86 South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, 87 Southwest Pathology Services, 88 Swansea University, 89 The Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, 90 The Queen Elizabeth Hospital King’s Lynn NHS Foundation Trust, 91 The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, 92 The Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust, 93 Turnkey Laboratory, University of Birmingham, 94 University College London Division of Infection and Immunity, 95 University College London Hospital Advanced Pathogen Diagnostics Unit, 96 University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, 97 University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, 98 University Hospitals Dorset NHS Foundation Trust, 99 University Hospitals Sussex NHS Foundation Trust, 100 University of Birmingham, 101 University of Brighton, 102 University of Cambridge, 103 University of East Anglia, 104 University of Edinburgh, 105 University of Exeter, 106 University of Kent, 107 University of Liverpool, 108 University of Oxford, 109 University of Sheffield, 110 University of Southampton, 111 University of St Andrews, 112 Viapath, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, and King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, 113 Virology, School of Life Sciences, Queens Medical Centre, University of Nottingham, 114 Watford General Hospital, 115 Wellcome Centre for Human Genetics, Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, 116 Wellcome Sanger Institute, 117 West of Scotland Specialist Virology Centre, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, 118 Whittington Health NHS Trust

*Consortium lead–email: sjp97@medschl.cam.ac.uk

Data Availability

Data cannot be shared publicly due to ethical constraints on data sharing because it contains sensitive patient data. As such, full data cannot be removed from the NHS GG&C SafeHaven, a trusted research environment without appropriate permissions. Aggregated data are available in the supplementary materials. The Safe Haven can be contacted for data access requests safehaven@ggc.scot.nhs.uk.

Funding Statement

COG-UK is supported by funding from the Medical Research Council (MRC) part of UK Research & Innovation (UKRI), the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) and Genome Research Limited, operating as the Wellcome Sanger Institute. Funding was also provided by UKRI through the JUNIPER consortium (MR/V038613/1). Sequencing, bioinformatics and statistical support was funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC) core awards for the MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research (MC UU 1201412) and MRC Biostatistics Unit (MC UU 00002/11). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Global Report B.1.1.7. PANGO Lineages 2023; January 31. Accessed 07/02/2023. Published online (https://cov-lineages.org/global_report_B.1.1.7.html)

- 2.Investigation of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in England, Technical briefing 6. London, UK. Public Health England (PHE), 13 February 2021 (https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/961299/Variants_of_Concern_VOC_Technical_Briefing_6_England-1.pdf)

- 3.Rees-Spear C, Muir L, Griffith SA, et al. The effect of spike mutations on SARS-CoV-2 neutralisation. Cell Reports 2021;34(12):108890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen X, Tang H, McDanal C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variant B.1.1.7 is susceptible to neutralizing antibodies elicited by ancestral spike vaccines. Cell Host & Microbe 2021;29(4):529–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Z, Schmidt F, Weisblum Y, et al. mRNA vaccine-elicited antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and circulating variants. Nature 2021;592:616–622. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03324-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thorne LG, Bouhaddou M, Reuschl AK, et al. Evolution of enhanced innate immune evasion by SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2022;602:487–495. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04352-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Volz E, Mishra S, Chand M, et al. Assessing transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Nature 2021;593:266–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03470-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies NG, Jarvis CI, CMMID COVID-19 Working Group, et al. Increased mortality in community-tested cases of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7. Nature 2021;593:270–274. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03426-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Challen R, Brooks-Pollock E, Read J, Dyson L, Tsaneva-Atanasova K, Danon L. Risk of mortality in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern 202012/1: matched cohort study. BMJ 2021;372:579. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grint DJ, Wing K., Williamson E, et al. Case fatality risk of the SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern B.1.1.7 in England, 16 November to 5 February. Euro Surveill 2021;26(11):2100256. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.11.2100256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nyberg T, Twohig KA, Harris RJ, et al. Risk of hospital admission for patients with SARS-CoV-2 variant B.1.1.7: cohort analysis. BMJ 2021;373:1412 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grint DJ, Wing K, Houlihan C, et al. Severity of Severe Acute Respiratory System Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Alpha Variant (B.1.1.7) in England. Clin Infect Dis 2021;ciab754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dabrera G, Allen H, Zaidi A, et al. Assessment of mortality and hospital admissions associated with confirmed infection with SARS-CoV-2 Alpha variant: a matched cohort and time-to-event analysis, England, October to December 2020. Euro Surveill 2022; 27(20):2100377. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.20.2100377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snell LB, Wang W, Alcolea-Medina A, et al. Descriptive comparison of admission characteristics between pandemic waves and multivariable analysis of the association of the Alpha variant (B.1.1.7 lineage) of SARS-CoV-2 with disease severity in inner London. BMJ Open 2022;12:e055474. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frampton D, Rampling T, Cross A, et al. Genomic characteristics and clinical effect of the emergent SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 lineage in London, UK: a whole-genome sequencing and hospital-based cohort study. Lancet Infectious Diseases 2021;21:1246–1256. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00170-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ong SWX, Chiew CJ, Ang LW, et al. Clinical and Virological Features of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Variants of Concern: A Retrospective Cohort Study Comparing B.1.1.7 (Alpha), B.1.351 (Beta), and B.1.617.2 (Delta). Clin Infect Dis 2021;ciab721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stirrup O, Boshier F, Venturini C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 is associated with greater disease severity among hospitalised women but not men: multicentre cohort study. BMJ Open Resp Res 2021;8:e001029. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2021-001029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Understanding vaccine progress. Accessed 07/02/2023. Published online (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/vaccines/international)

- 19.Willett BJ, Grove J, MacLean OA, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron is an immune escape variant with an altered cell entry pathway. Nat Microbiol 2022;7:1161–1179. doi: 10.1038/s41564-022-01143-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.da Silva Filipe A, Shepherd JG, Williams T, et al. Genomic epidemiology reveals multiple introductions of SARS-CoV-2 from mainland Europe into Scotland. Nat Microbiol 2021;6:112–122. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-00838-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The COVID-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) consortium. An integrated national scale SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance network. Lancet Microbe 2020;1(3):e99–e100. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30054-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Data Pipeline. COG-UK Consortium March 18 2021. (https://githubmemory.com/repo/COG-UK/grapevine_nextflow#pipeline-overview)

- 23.Volz E, Hill V, McCrone JT, et al. Evaluating the Effects of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Mutation D614G on Transmissibility and Pathogenicity. Cell 2021;184(1):64–75.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomson EC, Rosen LE, Shepherd JG, et al. Circulating SARS-CoV-2 spike N439K variants maintain fitness while evading antibody-mediated immunity. Cell 2021;184(5):1171–1187.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bürkner P-C, Vuorre M. Ordinal Regression Models in Psychology: A Tutorial. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science 2019;2(1):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bürkner P-C. Brms: An R Package for Bayesian Multilevel Models using Stan. Journal of Statistical Software 2017;80:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1999;94(446):496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gray B. cmprsk: Subdistribution Analysis of Competing Risks. R Project; 2020. (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=cmprsk) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hodcroft EB, Zuber M, Nadeau S, et al. Spread of a SARS-CoV-2 variant through Europe in the summer of 2020. Nature 2021;595:707–712. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03677-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lycett SA, Hughes J, McHugh MP, et al. Epidemic waves of COVID-19 in Scotland: a genomic perspective on the impact of the introduction and relaxation of lockdown on SARS-CoV-2. MedRxiv 2021:2021.01.08.20248677. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu G, Smith DK, Zhu H, et al. ggtree: an r package for visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees with their covariates and other associated data. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2016;8(1): 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ali F, Kasry A, Amin M. The new SARS-CoV-2 strain shows a stronger binding affinity to ACE2 due to N501Y mutant. Medicine in Drug Discovery 2021;10:100086. doi: 10.1016/j.medidd.2021.100086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kemp SA, Collier DA, Datir RP, et al. SARS-CoV-2 evolution during treatment of chronic infection. Nature 2021;592:277–282. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03291-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown JC, Goldhill DH, Zhou J, et al. Increased transmission of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 (VOC 2020212/01) is not accounted for by a replicative advantage in primary airway cells or antibody escape. BioRxiv 2021:2021.02.24.432576. [Google Scholar]