Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

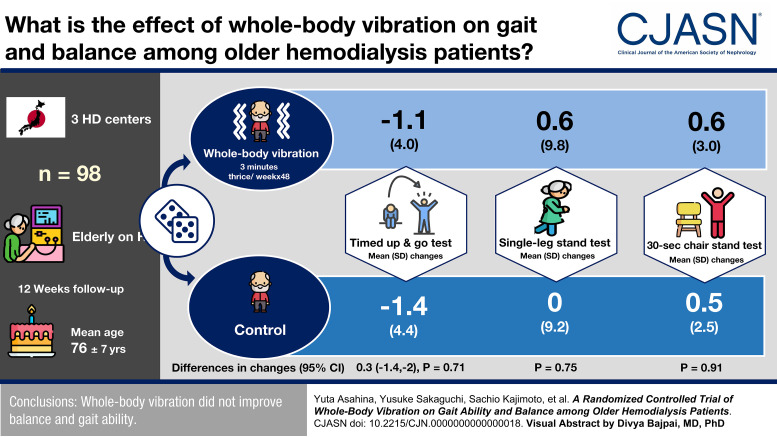

Gait abnormality is a serious problem among hemodialysis patients. Whole-body vibration is a simple exercise that induces sustained muscular contractions through mechanical vibrations. This training improved gait ability in older adults. We aimed to investigate the effect of whole-body vibration on balance and gait ability in older hemodialysis patients.

Methods

We conducted a 12-week, open-label, multicenter, randomized controlled trial of 98 hemodialysis patients, who were aged ≥65 years, from three dialysis centers in Japan. Those who had difficulty walking alone or dementia were excluded. Patients were randomly allocated to the whole-body vibration group or control group. The training was performed for 3 minutes thrice a week on dialysis days. The primary outcome was the Timed Up and Go test. The secondary outcomes were the single-leg stand test and 30-second chair stand test.

Results

The mean (SD) age of the participants was 76 (7) years. The mean (SD) Timed Up and Go test was 12.0 (6.6) and 11.8 (7.0) seconds in the whole-body vibration and control groups, respectively. During the 12-week study period, 6 (12%) of 49 patients in the whole-body vibration group and 3 (6%) of 49 patients in the control group dropped out. In the whole-body vibration group, 42 (86% of the randomly allocated patients) completed the training according to the protocol. The mean (SD) changes in the Timed Up and Go test were −1.1 (4.0) and −1.4 (4.4) seconds in the whole-body vibration and control groups, respectively (change, 0.3 seconds in the whole-body vibration group; 95% confidence interval, −1.4 to 2.0; P=0.71). The changes in the single-leg stand test and 30-second chair stand test did not differ significantly between groups. There were no musculoskeletal adverse events directly related to this training.

Conclusions

Whole-body vibration did not improve balance and gait ability.

Clinical Trial registry name and registration number:

Effect of Whole Body Vibration on Walking Performance in Elderly Hemodialysis Patients NCT04774731.

Introduction

Physical disability is highly prevalent among patients undergoing hemodialysis and progresses rapidly when compared with that in healthy individuals.1,2 Gait abnormality is particularly a major health problem for these patients, diminishing quality of life and increasing the risk of hospitalization and death.3–5 Furthermore, gait abnormality contributes to a higher risk of falls.6–8 Indeed, the incident rate of falls among hemodialysis patients is 1.18–1.60 per patient-year,9–11 which is much higher than that in the general older population (≥65 years), at approximately 0.67 per person-year.12 Serious fall injuries, such as fractures and brain injury, increase after dialysis initiation,13 which can lead to loss of independence. The fear of falling may further compromise physical function. While at least one third of falls among dialysis patients are accompanied by loss of balance,14 strategies to improve postural balance in these patients have not yet been established.

Previous intervention studies that addressed the gait ability of hemodialysis patients are limited because of the small sample size, poor quality of study design and reports, and difficulty in generalization and accessibility (e.g., exercise provided by nurse case management or supervised by qualified physical therapists).15–17 Recently, two well-designed randomized trials, EXCITE and IHOPE, tested the efficacy of physical exercise on walking capacity.18,19 In EXCITE, a personalized, low-intensity, and home-based walking program supervised by a specialized rehabilitation team showed a significant increase in 6-minute walking distance. By contrast, intradialytic cycle ergometer training did not improve walking performance in IHOPE. Notably, the attrition rates in the intervention groups of these trials were considerably high (31% in EXCITE and 41% in IHOPE), although the participants were relatively young (average age, 54–64 years). Further studies are needed to explore a training method that can be easily implemented in older dialysis patients.

Whole-body vibration is a simple exercise in which individuals are exposed to mechanical oscillations while standing on a vibrating platform. Whole-body vibration-induced mechanical vibrations elicit sustained muscular contractions, possibly through tonic vibration reflex via activation of muscle spindles.20,21 Whole-body vibration has become increasingly popular as a rehabilitation modality for older adults, as it improves postural balance22 and muscle strength23 and may reduce the risk of falls.24 A meta-analysis of randomized trials among older adults showed an improvement in gait speed and balance after whole-body vibration.25 More recently, Wadsworth and Lark26 confirmed the safety and efficacy of low-level whole-body vibration for improving gait speed and dynamic balance among very old and frail individuals. Unfortunately, among hemodialysis patients, whole-body vibration has been studied only in small, preliminary studies.27–29

The aim of this randomized trial was to investigate the feasibility of whole-body vibration and its effect on balance and gait ability among older hemodialysis patients.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This was a 12-week, open-label, multicenter, randomized controlled trial investigating whether whole-body vibration improves gait ability and balance in hemodialysis patients. We enrolled patients from three dialysis centers in Osaka, Japan, between April 2021 and March 2022. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Osaka University Hospital (approval no. 20337). This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04774731) on March 1, 2021.

Patients aged ≥65 years who received thrice weekly in-center maintenance hemodialysis were eligible to participate in this study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) difficulty walking alone, (2) dementia that could hinder participation in the training, (3) a history of leg fracture in the previous 1 year of randomization, or (4) a history of total hip replacement. We did not exclude patients who used walking aids as long as they could walk alone.

Randomization

Eligible patients were randomly assigned to the whole-body vibration or control groups in a 1:1 ratio. Randomization was performed centrally using a computer-generated random number list with a permuted block size of four and was appropriately concealed from participants and investigators. The randomization procedure was conducted by one of the investigators at Osaka University who was blinded to the participants' information and was not involved in study enrollment.

Intervention

Participants who were randomly allocated to the whole-body vibration group underwent whole-body vibration using a side-alternating vibration platform Galileo S35 (Novotec GmbH, Pforzheim, Germany) for 12 weeks. The training was conducted at the dialysis centers thrice weekly on dialysis days before the initiation of dialysis therapy without specialized training staff or nurses. In each training session, the participants stood on the platform for 3 minutes with bent knees. They were instructed to take off their shoes and hold a handrail while training. The vibration frequency was 18 Hz during the first week and was increased by 2 Hz/wk to a maximum of 26 Hz. The participants chose an amplitude within the range of 2.0–3.0 mm on the basis of their comfort level. We directly monitored the adherence and safety of training throughout the study period. Musculoskeletal adverse events were recorded although whole-body vibration was expected to be a safe exercise for older individuals.26 Patients randomly allocated to the control group received the standard care.

Outcome Measures

Physical performance tests were conducted at baseline and at the end of the study period (week 12) before the initiation of dialysis session. The tests at week 12 were performed on the next dialysis day after the last training session.

We used a cloud-based wearable application, Moff Band (Moff, Inc., Tokyo, Japan), for the measurement of the physical performance tests.30 This device is equipped with built-in gyro sensors and accelerometers, which enable fully automated measurements by detecting postural changes and body movements. The researchers who were blinded to the study allocation instructed the participants on how to use the device and supervised the implementation of the physical performance tests, but they did not measure the time.

Primary Outcome: Timed Up and Go Test

The Timed Up and Go test is widely used to assess functional mobility, balance, lower limb strength, and gait speed. Participants were instructed to sit on a chair, stand, walk to the 3-m mark as quickly as possible, walk back to the chair, and sit down again. The time from standing up to sitting down was automatically measured using the Moff Band that was placed around the thigh. The test was conducted twice, and the best time was recorded.31,32

Secondary Outcomes

Single-Leg Stand Test

The single-leg stand test is a simple and frequently used test to assess static balance that has shown good reproducibility and inter-rater reliability.33–35 Participants were instructed to stand unassisted on one leg for as long as possible with their eyes open. The time until the raised foot touched the floor was automatically measured using the Moff Band. The test was conducted twice for each leg, and the best time of the four measurements was recorded.33

Thirty-Second Chair Stand Test

The 30-second chair stand test is a valid test to evaluate the leg strength and endurance of older adults with a high test–retest reliability.36 Participants were instructed to sit on a chair with crossed arms, rise to a full standing position, and then return to a seated position. The number of times participants could take a full standing position in 30 seconds was automatically measured by the Moff Band. This test was conducted only once.

Statistical Analysis

We estimated that a sample size of 90 patients would provide a power of 80% at a two-sided α error level of 0.05 to detect a between-group difference in the change in the Timed Up and Go test of 1.0 second with a SD of 1.5 seconds. This effect size of 1.0 second was determined based on a previous randomized trial of older women showing a reduced risk of fall by balance training that decreased the Timed Up and Go test by 0.68 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.10 to 1.27) seconds.37 Assuming a dropout rate of 10%, we planned to enroll 100 participants. Interim analysis was not performed.

The primary analysis was performed based on the intention-to-treat principle, which included all randomly allocated patients. The missing data for the second physical performance tests were imputed based on the median values of the control group. We used a difference-in-changes approach to analyze the average treatment effect of the whole-body vibration on the intervention group, in which the coefficient of the interaction term between time and study groups was estimated using a linear regression model.

We conducted two additional analyses. First, an on-treatment analysis was performed, in which patients who discontinued whole-body vibration during the study period were excluded. Second, in the intention-to-treat analysis, the missing data for the second physical performance tests were imputed based on the median values of the whole-body vibration group.

All P values were two-sided. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using StataIC 17 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Figure 1 presents a flow diagram of this study. Among the 122 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 24 refused to participate. A total of 98 patients were randomly allocated to the whole-body vibration (n=49) and control groups (n=49). The baseline characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1. Overall, the mean (SD) age was 76 (7) years; 45% had diabetes mellitus, and 50% had cardiovascular comorbidities. There were no substantial differences between the two study groups in any baseline characteristics, except for a slightly higher male prevalence in the whole-body vibration group.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study. AV, arteriovenous.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants in a multicenter randomized controlled trial investigating whether whole-body vibration improves gait ability and balance in hemodialysis patients

| Baseline Characteristics | Total, n=98 | Control Group, n=49 | Whole-Body Vibration Group, n=49 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 76 (7) | 77 (7) | 75 (6) |

| Male, n (%) | 55 (56) | 24 (49) | 31 (63) |

| BMI | 20.8 (3.3) | 20.5 (2.8) | 21.2 (3.6) |

| Dialysis vintage, yr | 5 [3, 10] | 5 [3, 8] | 5 [3, 12] |

| Serum albumin, g/dl | 3.7 (0.3) | 3.7 (0.3) | 3.8 (0.3) |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 9.1 (2.4) | 8.8 (2.2) | 9.4 (2.4) |

| Serum calcium, mg/dl | 8.4 (0.7) | 8.4 (0.8) | 8.4 (0.6) |

| Serum phosphate, mg/dl | 5.0 (1.2) | 5.0 (1.0) | 5.0 (1.4) |

| Alkaline phosphatase, U/L | 191 [94, 262] | 175 [98, 228] | 203 [94, 302] |

| Intact PTH, pg/ml | 140 [96, 179] | 130 [82, 184] | 152 [117, 176] |

| C-reactive protein, mg/dl | 0.10 [0.05, 0.31] | 0.12 [0.06, 0.33] | 0.09 [0.05, 0.19] |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 11.2 (1.1) | 11.2 (1.3) | 11.3 (0.9) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 44 (45) | 22 (45) | 22 (45) |

| Cardiovascular comorbidities, n (%) | 49 (50) | 26 (53) | 23 (47) |

| Peripheral artery disease, n (%) | 10 (10) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) |

Data are presented as the mean (SD), median [25th, 75th percentile], or number (%). Cardiovascular comorbidities included chronic heart failure, coronary artery disease, stroke, peripheral artery disease, aortic disease, and valvular disease. BMI, body mass index; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

During the 12-week study period, six (12%) of 49 patients in the whole-body vibration group and three (6%) of 49 patients in the control group dropped out and did not undergo the second physical performance tests. The reasons for dropout in the whole-body vibration group were deemed unrelated to the implementation of this training. Of the 43 patients in the whole-body vibration group who underwent the second physical performance tests, one patient discontinued the training during the study period because of preexisting low back pain. The remaining 42 patients (86% of those randomly allocated to the whole-body vibration group) completed all training sessions during the 12-week study period as per the protocol. No musculoskeletal adverse events were reported in these patients.

Primary Outcome

The results of the physical performance tests are shown in Table 2. The mean (SD) change in the Timed Up and Go test was −1.1 (4.0) and −1.4 (4.4) seconds in the whole-body vibration and control groups, respectively. The difference-in-changes analysis showed that the effect of whole-body vibration on the Timed Up and Go test was not significant (change, 0.3 seconds in the whole-body vibration group; 95% CI, −1.4 to 2.0; P=0.71).

Table 2.

Results of physical performance tests—intention-to-treat analysis

| Group Name | Primary Outcome | Secondary Outcomes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timed Up and Go Test | Single-Leg Stand Test | 30-s Chair Stand Test | |||||||

| Baseline | Week 12 | Changea | Baseline | Week 12 | Changea | Baseline | Week 12 | Changea | |

| Control group (n=49) | 11.8 (7.0) | 10.4 (4.1) | −1.4 (4.4) | 12.1 (19.6) | 12.1 (22.6) | 0 (9.2) | 10.7 (4.5) | 11.2 (4.2) | 0.5 (2.5) |

| Whole-body vibration group (n=49) | 12.0 (6.6) | 10.9 (5.4) | −1.1 (4.0) | 9.6 (15.0) | 10.2 (17.2) | 0.6 (9.8) | 10.4 (4.8) | 11.0 (5.2) | 0.6 (3.0) |

| Difference-in-changes (95% confidence interval) | — | — | 0.3 (−1.4 to 2.0) | — | — | 0.6 (−3.2 to 4.4) | — | — | 0.1 (−1.0 to 1.2) |

| P valueb | — | — | 0.71 | — | — | 0.75 | — | — | 0.91 |

Data presented as mean (SD). Missing data for each outcome at week 12 were imputed according to the median value of the control group.

Changes from baseline to week 12.

P values for difference-in-changes.

Secondary Outcomes

The mean (SD) change in the single-leg stand test was 0.6 (9.8) and 0 (9.2) seconds in the whole-body vibration and control groups, respectively. The difference-in-changes was not significant (change, 0.6 seconds in the whole-body vibration group; 95% CI, −3.2 to 4.4; P=0.75).

The mean (SD) change in 30-second chair stand test was 0.6 (3.0) and 0.5 (2.5) in the whole-body vibration and control groups, respectively. The difference-in-changes was not significant (change, 0.1 in the whole-body vibration group; 95% CI, −1.0 to 1.2; P=0.91).

Additional Analyses

In the on-treatment analyses, whole-body vibration did not significantly improve the physical performance tests (Supplemental Table 1). When missing values for the outcome measures were imputed using the median value of the whole-body vibration group, the results of the intention-to-treat analysis were not substantially altered (Supplemental Table 2).

Discussion

In this open-label, multicenter, randomized controlled trial, we found that whole-body vibration was well tolerated in older hemodialysis patients. The dropout rates were similar between the whole-body vibration and control groups, and nearly 90% of the patients in the whole-body vibration group adhered to the 12-week training protocol without experiencing any serious adverse events. However, whole-body vibration did not improve gait ability and balance, as assessed by the physical performance tests.

The primary outcome, the Timed Up and Go test, was not significantly improved by whole-body vibration. The Timed Up and Go test predominantly reflects lower limb muscle strength.38 A previous meta-analysis of 37 randomized trials in older adults suggested that whole-body vibration is likely to improve muscle strength in a “No-Go” subgroup (in need of care because of severe functional limitations).23 The functional ability of our patients was mostly preserved because the inclusion criteria designated that they regularly attended outpatient dialysis centers and could walk alone. This may explain why whole-body vibration failed to improve the Timed Up and Go test in our study. The same explanation may be applicable to the neutral result of the 30-second chair stand test score, which is also related to lower limb muscle strength, especially that of the quadriceps.39 In other words, the intensity of whole-body vibration in our study may not have been sufficient to increase muscle strength. Indeed, previous pilot studies of hemodialysis patients have reported that higher vibration frequencies (35–50 Hz) and larger amplitude (4–10 mm) than those in our study improved the 60-second sit-to-stand test and knee extensor muscle strength, although these studies were limited by the small sample size or nonrandomized study design.27–29

Whole-body vibration is known to improve balance ability in the general older population.22 In our study, however, we did not observe a significant improvement in the single-leg stand test, which is one of the most frequently used tests to assess postural balance. This discrepancy may be explained by the different study populations. In addition, training intensity and duration might be suboptimal. Although there are few studies examining the efficacy of balance training in hemodialysis patients, Frih et al.40 reported that a 24-week program with balance training (30 min/session) four times a week on nondialysis days improved the postural balance of hemodialysis patients when included in a usual endurance-resistance training monitored by professional physiotherapists. Further studies are warranted to explore whether more intense training with whole-body vibration could improve balance ability in hemodialysis patients.

There are several potential reasons for the high adherence to whole-body vibration observed in this study. First, the training was performed on dialysis days at dialysis centers without sparing time on nondialysis days. Thus, this type of training probably does not require a high degree of active participation. Second, whole-body vibration can be easily implemented by patients themselves, without involvement or supervision of specialized staff. Finally, whole-body vibration is passive training where patients only stand on a vibrating platform for a short period of time. For older and frail patients, active endurance exercise is often difficult and demanding, which results in reluctance to continue such training. Passive training, such as whole-body vibration, has thus been considered suitable for older patients.41,42 However, it should be noted that the intervention duration in our study (12 weeks) was shorter than that of EXCITE and IHOPE (6 months and 1 year, respectively).18,19 Therefore, further studies are warranted to evaluate longer-term adherence to whole-body vibration among older hemodialysis patients.

It is of clinical importance to develop fall prevention strategies for older hemodialysis patients. Unfortunately, our study did not show an improvement in the three physical performance tests, although this does not necessarily mean that whole-body vibration is useless for fall prevention. It should be recognized that, other than gait abnormality, there are multiple risk factors for falls such as cognitive and visual impairments, medications, postural hypotension, frailty, and urinary incontinence. Therefore, multifactorial management with various interventions will be mandatory for effective fall prevention.43

This study had several limitations. First, the study design was open label. To avoid measurement arbitrariness, we utilized the cloud-based application to automatically measure the physical performance tests. Second, the intervention duration was relatively short; thus, the long-term efficacy and adherence to whole-body vibration are uncertain. Third, the sample size was not so large. Fourth, because this study was conducted among older individuals in Japan, the generalizability of our findings to younger populations and different ethnic groups is unknown. Finally, our patients may have had relatively preserved physical function because we excluded those who had difficulty walking alone and those with dementia. Therefore, the adherence and tolerability of whole-body vibration among frail dialysis patients should be investigated.

In conclusion, whole-body vibration was well tolerated by older hemodialysis patients, which was implemented with high adherence. We observed no musculoskeletal adverse events directly related to this training. However, this training did not improve balance and gait ability. Future studies are warranted to determine the efficacy and adherence of longer and more intense whole-body vibration training for hemodialysis patients.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Y.A. and Y.S. contributed equally to this work.

See related Patient Voice, “Gait and Balance in People Undergoing Long-Term Hemodialysis,” and editorial, “Improving Physical Functioning for People on Long-Term Dialysis: What Does the Evidence Show?” on pages 1–2 and 5–7, respectively.

Disclosures

Y. Isaka reports research funding from Chugai Pharma Co., Ltd., Kirin Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; advisory or leadership roles for Chugai Pharma Co., Ltd. and Kirin Co., Ltd.; and speakers bureau for Astellas Pharma, Inc., AstraZeneca plc, Kirin Co., Ltd., Kissei Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. N. Kashihara reports consultancy agreements with AstraZeneca, Kyowa Kirin, and Novartis; research funding from Astellas, Daiichi-Sankyo, Otsuka, and Takeda; honoraria from Astellas, Daiichi-Sankyo, Otsuka, and Takeda; advisory or leadership roles for AstraZeneca, Kyowa Kirin, and Novartis; and other interests or relationships with Japan Kidney Association and Japanese Society of Nephrology. Y. Sakaguchi reports research funding from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., FUSO Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd., Kissei Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Kyowa Kirin Co., Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Terumo Co., Ltd., and Torii Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical, Co., Ltd., Fuso, Kyowa Kirin Co., Ltd., and Torii Pharmaceutical, Co., Ltd. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Osaka Kidney Foundation (OKF21-0002, 22-0002) and the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Health Labor Sciences Research Grant (20CA2039).

Authors Contributions

Y. Asahina, Y. Isaka, and Y. Sakaguchi conceptualized the study; Y. Asahina and Y. Sakaguchi were responsible for data curation and formal analysis; Y. Asahina, K. Hattori, Y. Isaka, J.-Y. Kaimori, T. Oka, and Y. Sakaguchi investigated the study; Y. Asahina and Y. Sakaguchi were responsible for the methodology; Y. Isaka and N. Kashihara provided funding acquisition; Y. Isaka and N. Kashihara were responsible for project administration; Y. Isaka, J.-Y. Kaimori, N. Kashihara, and T. Oka were responsible for supervision; Y. Asahina and Y. Sakaguchi wrote the original draft; Y. Sakaguchi validated the study; and K. Hattori, Y. Isaka, J.-Y. Kaimori, S. Kajimoto, N. Kashihara, T. Oka, and Y. Sakaguchi reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Data Sharing Statement

Individual de-identified data will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://links.lww.com/CJN/B78.

Supplemental Table 1. Results of physical performance tests—on-treatment analysis.

Supplemental Table 2. Results of physical performance tests—additional analysis for the intention-to-treat analysis.

References

- 1.Kim JC Shapiro BB Zhang M, et al. Daily physical activity and physical function in adult maintenance hemodialysis patients. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2014;5(3):209-220. doi: 10.1007/s13539-014-0131-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Loon I Hamaker ME Boereboom FTJ, et al. A closer look at the trajectory of physical functioning in chronic hemodialysis. Age Ageing. 2017;46(4):594-599. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afx006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kutner NG, Zhang R, Huang Y, Painter P. Gait speed and mortality, hospitalization, and functional status change among hemodialysis patients: a US Renal Data System special study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(2):297-304. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kittiskulnam P, Chertow GM, Carrero JJ, Delgado C, Kaysen GA, Johansen KL. Sarcopenia and its individual criteria are associated, in part, with mortality among patients on hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2017;92(1):238-247. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.01.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erken E Ozelsancak R Sahin S, et al. The effect of hemodialysis on balance measurements and risk of fall. Int Urol Nephrol. 2016;48(10):1705-1711. doi: 10.1007/s11255-016-1388-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tran J, Ayers E, Verghese J, Abramowitz MK. Gait abnormalities and the risk of falls in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(7):983-993. doi: 10.2215/CJN.13871118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zanotto T Mercer TH van der Linden ML, et al. Association of postural balance and falls in adult patients receiving haemodialysis: a prospective cohort study. Gait Posture. 2020;82:110-117. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2020.08.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perez-Gurbindo I, Maria Alvarez-Mendez A, Perez-Garcia R, Cobo PA, Carrere MTA. Factors associated with falls in hemodialysis patients: a case-control study. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2021;29:e3505. doi: 10.1590/1518-8345.5300.3505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desmet C, Beguin C, Swine C, Jadoul M; Universite Catholique de Louvain Collaborative Group. Falls in hemodialysis patients: prospective study of incidence, risk factors, and complications. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45(1):148-153. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook WL Tomlinson G Donaldson M, et al. Falls and fall-related injuries in older dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(6):1197-1204. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01650506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.López-Soto PJ De Giorgi A Senno E, et al. Renal disease and accidental falls: a review of published evidence. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16(1):176. doi: 10.1186/s12882-015-0173-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergen G, Stevens MR, Burns ER. Falls and fall injuries among adults aged ≥65 years—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(37):993-998. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6537a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plantinga LC, Patzer RE, Franch HA, Bowling CB. Serious fall injuries before and after initiation of hemodialysis among older ESRD patients in the United States: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(1):76-83. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zanotto T Mercer TH van der Linden ML, et al. The relative importance of frailty, physical and cardiovascular function as exercise-modifiable predictors of falls in haemodialysis patients: a prospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-01759-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zemp DD, Giannini O, Quadri P, de Bruin ED. Gait characteristics of CKD patients: a systematic review. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s12882-019-1270-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heiwe S, Jacobson SH. Exercise training in adults with CKD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(3):383-393. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yabe H, Kono K, Yamaguchi T, Ishikawa Y, Yamaguchi Y, Azekura H. Effects of intradialytic exercise for advanced-age patients undergoing hemodialysis: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0257918. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manfredini F Mallamaci F D'Arrigo G, et al. Exercise in patients on dialysis: a multicenter, randomized clinical trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(4):1259-1268. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016030378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeong JH Biruete A Tomayko EJ, et al. Results from the randomized controlled IHOPE trial suggest no effects of oral protein supplementation and exercise training on physical function in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2019;96(3):777-786. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2019.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cardinale M, Wakeling J. Whole body vibration exercise: are vibrations good for you? Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(9):585-589. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2005.016857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crewther B, Cronin J, Keogh J. Gravitational forces and whole body vibration: implications for prescription of vibratory stimulation. Phys Ther Sport. 2004;5(1):37-43. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rogan S Taeymans J Radlinger L, et al. Effects of whole-body vibration on postural control in elderly: an update of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;73:95-112. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2017.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogan S de Bruin ED Radlinger L, et al. Effects of whole-body vibration on proxies of muscle strength in old adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis on the role of physical capacity level. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act. 2015;12(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s11556-015-0158-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jepsen DB, Thomsen K, Hansen S, Jorgensen NR, Masud T, Ryg J. Effect of whole-body vibration exercise in preventing falls and fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e018342. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fischer M Vialleron T Laffaye G, et al. Long-term effects of whole-body vibration on human gait: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol. 2019;10:627. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wadsworth D, Lark S. Effects of whole-body vibration training on the physical function of the frail elderly: an open, randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101(7):1111-1119. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2020.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fuzari HKB de Andrade AD Cerqueira MS, et al.. Whole body vibration to attenuate reduction of explosive force in chronic kidney disease patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Exerc Rehabil. 2018;14(5):883-890. doi: 10.12965/jer.1836282.141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fuzari HK Dornelas de Andrade A A Rodrigues M, et al. Whole body vibration improves maximum voluntary isometric contraction of knee extensors in patients with chronic kidney disease: a randomized controlled trial. Physiother Theor Pract. 2019;35(5):409-418. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2018.1443537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doyle A, Chalmers K, Chinn DJ, McNeill F, Dall N, Grant CH. The utility of whole body vibration exercise in haemodialysis patients: a pilot study. Clin Kidney J. 2017;10(6):822-829. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfx046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abo M Suzuki T Kawaji H, et al. A comparison of motion analysis between an optical motion capture system and a wearable device-based motion capture system by using acceleration and gyro sensors. Article in Japanese. Tokyo Jikeikai Med J. 2018;133:95-105. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rockwood K, Awalt E, Carver D, MacKnight C. Feasibility and measurement properties of the functional reach and the Timed Up and Go tests in the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(2):M70-M73. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.2.m70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brooks D, Davis AM, Naglie G. Validity of 3 physical performance measures in inpatient geriatric rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(1):105-110. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.08.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Springer BA, Marin R, Cyhan T, Roberts H, Gill NW. Normative values for the unipedal stance test with eyes open and closed. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2007;30(1):8-15. doi: 10.1519/00139143-200704000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolinsky FD, Miller DK, Andresen EM, Malmstrom TK, Miller JP. Reproducibility of physical performance and physiologic assessments. J Aging Health. 2005;17(2):111-124. doi: 10.1177/0898264304272784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giorgetti MM, Harris BA, Jette A. Reliability of clinical balance outcome measures in the elderly. Physiother Res Int. 1998;3(4):274-283. doi: 10.1002/pri.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones CJ, Rikli RE, Beam WC. A 30-s chair-stand test as a measure of lower body strength in community-residing older adults. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1999;70(2):113-119. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1999.10608028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El-Khoury F, Cassou B, Latouche A, Aegerter P, Charles MA, Dargent-Molina P. Effectiveness of two year balance training programme on prevention of fall induced injuries in at risk women aged 75–85 living in community: Ossébo randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2015;351:h3830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coelho-Junior HJ, Rodrigues B, de Oliveira Gonçalves I, Asano RY, Uchida MC, Marzetti E. The physical capabilities underlying timed “Up and Go” test are time-dependent in community-dwelling older women. Exp Gerontol. 2018;104:138-146. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2018.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lord SR, Murray SM, Chapman K, Munro B, Tiedemann A. Sit-to-stand performance depends on sensation, speed, balance, and psychological status in addition to strength in older people. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(8):M539-M543. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.8.m539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frih B Mkacher W Jaafar H, et al. Specific balance training included in an endurance-resistance exercise program improves postural balance in elderly patients undergoing haemodialysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(7):784-790. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1276971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takahashi T, Takeshima N, Rogers NL, Rogers ME, Islam MM. Passive and active exercises are similarly effective in elderly nursing home residents. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27(9):2895-2900. doi: 10.1589/jpts.27.2895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heesterbeek M, Van der Zee EA, van Heuvelen MJG. Passive exercise to improve quality of life, activities of daily living, care burden and cognitive functioning in institutionalized older adults with dementia—a randomized controlled trial study protocol. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):182. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0874-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ganz DA, Latham NK. Fall prevention in community-dwelling older adults. Reply. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(26):2581-2582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2005662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Individual de-identified data will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.