Summary

Oral microbial communities assemble into complex spatial structures. The sophisticated physical and chemical signaling systems underlying the community enable their collective functional regulation as well as the ability to adapt by integrating environmental information. The combined output of community action, as shaped by both intra-community interactions and host and environmental variables, dictates homeostatic balance or dysbiotic disease, such as periodontitis and dental caries. Oral polymicrobial dysbiosis also exerts systemic effects that adversely affect comorbidities, in part due to ectopic colonization of oral pathobionts in extra-oral tissues. Here we review new and emerging concepts that explain the collective functional properties of oral polymicrobial communities and how these impact health and disease both locally and systemically.

In Brief

In oral polymicrobial communities, individual species are physically and metabolically integrated and their combined interaction with the host environment governs homeostatic balance or dysbiosis. Hajishengallis et al. discuss the spatial structuring of these communities, mechanisms underlying the community’s emergent functions and their impact on local and systemic health and disease.

Introduction

It is becoming increasingly apparent that microbial communities are the etiologic units in oral pathologies such as caries and periodontal disease. The emergent concept of community pathogenicity, or nososymbiocity, where the microbial community is more than the sum of its parts, has spurred interest in the mechanisms that underlie community properties. The picture has emerged of multidimensional interconnectivity within communities that operates under spatial and temporal constraints, and which can be sculpted by the host microenvironment. Community participants are physically and metabolically integrated through co-adhesion and the exchange of diffusible signaling molecules and metabolites (Hajishengallis and Lamont, 2016). Such interspecies interactions can either enhance or suppress colonization and pathogenicity depending on context, and examples of both outcomes are well-documented (Cheng et al., 2020; Hoare et al., 2021; Lamont et al., 2018). The totality of intra-community interactions and host-community interactions thus defines homeostatic or dysbiotic outcomes.

Successful colonizers of oral microbial communities integrate information not only from partner species but also from the host microenvironment. In fact, the ability of pathobiotic species to adapt to and/or exploit environmental changes, such as inflammation or the presence of dietary sugars, is a key factor for the dysbiotic transformation of communities that provoke periodontal disease and dental caries, respectively (Lamont et al., 2018). Moreover, an imbalanced interplay between the oral microbiome and the host immune response may have an impact above and beyond the local tissues. Indeed, oral microbial dysbiosis can causally link oral disease to extraoral comorbidities via induction of systemic inflammation or ectopic colonization of oral species in remote tissues (Dominy et al., 2019; Kitamoto et al., 2020; Li et al., 2022). In this review, we discuss the spatial structuring of oral polymicrobial communities, novel mechanisms that drive the community’s emergent functional properties and how these interact with the host both locally and systemically.

Spatial structure

The human mouth provides multiple habitats encompassing a variety of biotic and abiotic surfaces with different topographies for microbes to colonize and develop biofilm communities (Lamont et al., 2018; Mark Welch et al., 2019). Rather than a homogeneous mixture of different species randomly distributed on the surface, microbes within oral biofilms are arranged nonrandomly, forming spatially structured polymicrobial communities (Bowen et al., 2018; Wilbert et al., 2020). Furthermore, the resident microbes are incredibly diverse, harboring multiple species and even different kingdoms that are often enmeshed in an extracellular polymeric matrix that provides protection, cohesion, and scaffolding (Baker et al., 2017; Bowen et al., 2018; Mark Welch et al., 2020).

Molecular sequencing technologies and multi-omics approaches have advanced our understanding about the microbial communities of oral microbiomes (Divaris, 2019; Overmyer et al., 2021). While most of these approaches have provided significant advances, knowledge has been predominantly generated from disrupted, pooled samples collected at various sites. Conversely, multiple imaging modalities have revealed that the different microbial species residing in intact biofilms form unique spatial arrangements at various habitats across multiple-length scales (Kim et al., 2020; Mark Welch et al., 2016; Zijnge et al., 2010). Hence, microbial communities can be defined by microbiome composition (based on sequence read abundance over a range of taxonomy), function (the physiologic and metabolic interactions), and spatial structure (based on how microbes are physically associated to each other). Importantly, these communities are highly dynamic at spatial, temporal, and phylogenetic levels, which in turn modulates phenotypic diversity and functional activities (Ladau and Eloe-Fadrosh, 2019; Nadell et al., 2016).

This complex community organization is also termed biogeography, i.e., the spatial assembly, patterning, and distribution of microbes across different habitats and niches through time (Mark Welch et al., 2019). Recent reviews have provided in-depth information on the biogeography of the oral microbiome in the mouth, the diversity of interactions, and their potential impact in health and disease (Mark Welch et al., 2019). As an instructive example, we discuss the spatial arrangement and microbial positioning in supragingival biofilms associated with human tooth decay (dental caries) and how changes in spatial patterning at the micron scale may correlate with disease onset and severity.

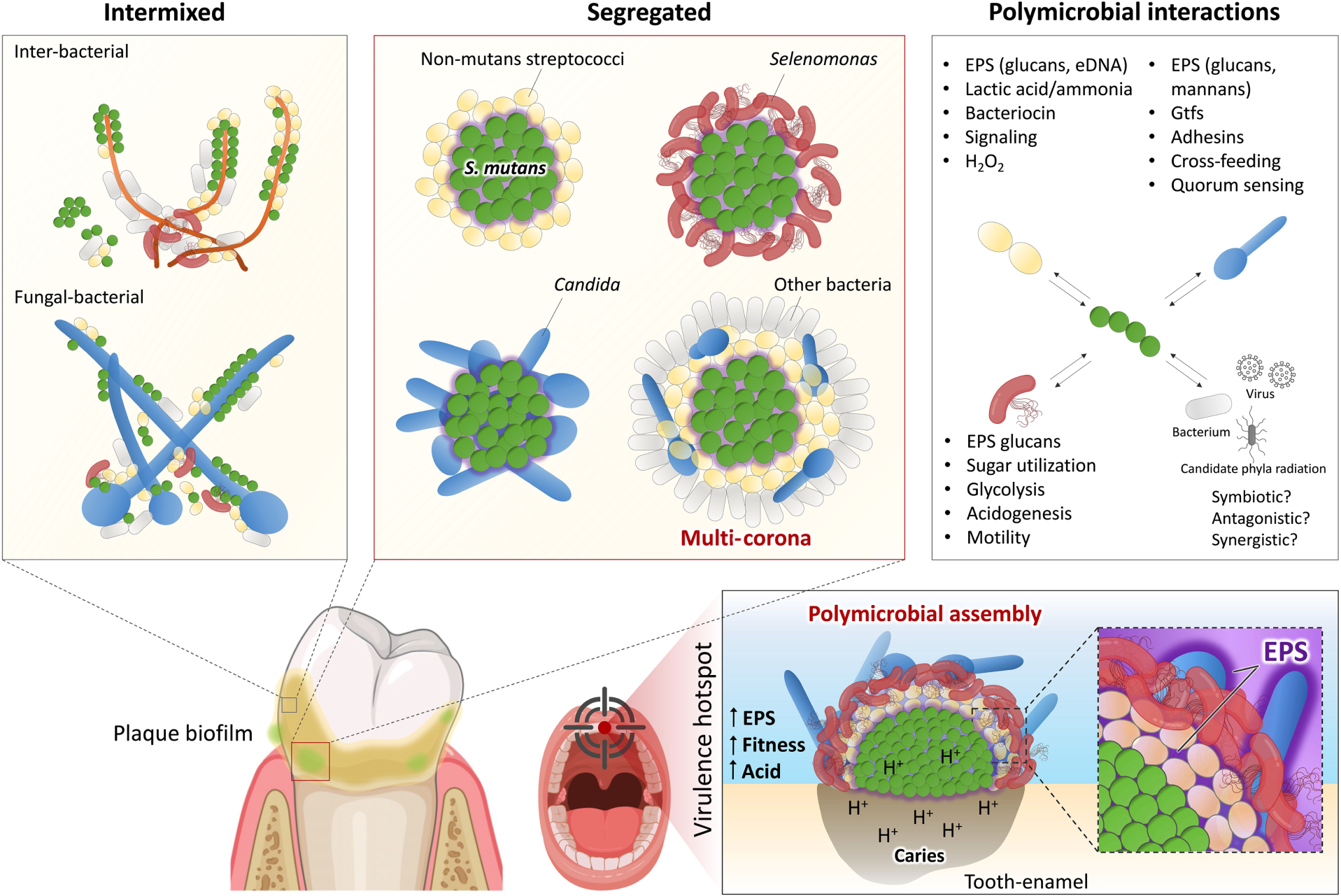

Spatial structure imaging has been extensively explored despite the technical challenges of analyzing undisturbed biofilm structure. High-resolution imaging techniques, from traditional FISH to CLASI- and HiPR-FISH, have revealed a multitude of interesting spatial patterning of diverse taxa, including bacterial-fungal co-assemblies, in human dental plaque and on the tongue dorsum (Kim and Koo, 2020; Mark Welch et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2020; Wilbert et al., 2020; Zijnge et al., 2010). Recent studies have explored the role of biogeography in virulence by assessing microbial positioning in undisturbed microbial communities on intact teeth (Kim et al., 2020) and functional microbiomes of plaque biofilms (Cho et al., 2022) from children with high levels of caries. Using multi-length scale imaging and computational analysis of the native biofilm structure, various spatial patterns, ranging from intertwined mixed-bacterial species and interkingdom clustering, to spatially segregated species forming multilayered spatial organizations, are observed (Figure 1). A distinctive 3D rotund-shaped architecture can be found associated with diseased samples. This structure is composed of multiple species precisely organized in a corona-like arrangement with an inner core harboring densely clustered Streptococcus mutans (a major cariogenic pathogen) surrounded by outer layers of other bacterial species in juxtaposition, forming a highly ordered spatial configuration (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The spatial structure (biogeography) of oral polymicrobial communities.

The oral microbiota harbors a multitude of bacterial, fungal, viral, and even ultrasmall organisms distributed across different biotic and abiotic niches present in the mouth environment. These diverse communities can be found intermixed forming a variety of co-adhered or clustered populations as well as segregated spatial patterns which are modulated by cooperative or competitive interactions among community members. Pathogenic microbes, such as Streptococcus mutans, form highly organized polymicrobial communities, in which precise biogeography dictates positioning at the infection site (supragingival) and promotes a disease-causing state (dental caries). Complex physical and chemical interactions with different species promote a multilayered, corona-like spatial arrangement formed by an inner core composed of S. mutans clusters surrounded by EPS glucans and outer layers of other oral microbes. This spatial structure enhances bacterial fitness and protection and creates a highly acidic microenvironment, leading to localized onset of dental caries. Precise positioning and polymicrobial arrangement can coordinate the disease process in situ to create virulence hotspots that could serve as therapeutic targets.

Insights into how such spatial structures form and their role in disease were provided by a multiparameter in situ analysis which showed that the rotund architecture created localized regions of highly acidic pH (<5.0) that precisely matched caries development on a human tooth-enamel surface, indicating that this highly ordered community is associated with the onset of the disease (Kim et al., 2020). Additional studies reveal that formation of the corona cell arrangement is an active process initiated by production of an extracellular polymeric matrix by S. mutans that directs the positioning of other bacteria by creating physical boundaries to assemble the virulent community. This spatial structuring also enhances antimicrobial tolerance while increasing aciduric fitness associated with the disease-causing state (Figure 1).

Further compositional analyses reveal a complex microbiota in association with S. mutans, including previously unrecognized bacterial species (e.g., Selenomonas sputigena, Prevotella salivae, Leptotrichia wadei) and even fungi (e.g., C. albicans), indicating interspecies and interkingdom interactions create a precise pathological niche. Surprisingly, a flagellated subgingival anaerobe (Selenomonas sputigena) appears to play a key role in this spatial structure, exacerbating supragingival biofilm virulence and causing severe caries in vivo (Cho et al., 2022). RNA-sequencing, metabolomics and microcalorimetry analyses reveal interspecies gene-gene interactions, cooperative sugar utilization, and upregulation of metabolic pathways (glycolysis, pyruvate fermentation and UDP-N-acetylglucosamine), resulting in enhanced acidogenesis, a hallmark of caries virulence. Multiscale imaging shows intriguing physical interactions whereby S. sputigena becomes trapped in the streptococcal exoglucan matrix, losing its motility but actively proliferating to build the corona-like arrangement that wraps the S. mutans inner core (Figure 1). Hence, a subgingival bacterium associated with periodontitis can modulate the spatial structure and pathogenicity of supragingival biofilms. These studies provide the initial framework for establishing a causal link between biogeography and disease, whereby the spatial microbiome arrangement and pathogen positioning in their native state may dictate the virulence potential in situ.

Interestingly, Candidate Phyla Radiation, ultra-small bacteria, have been isolated also from the oral cavity. Among them, Saccharibacteria (200–300 nm; formerly TM7) have been found attached to oral Actinobacteria, feeding off the host to cause cell death and lysis (McLean et al., 2020). Whether and how this parasitic interaction influences the community organization and its interplay with the mammalian host has only now started to be addressed (Naud et al., 2022).

Interspecies interactions

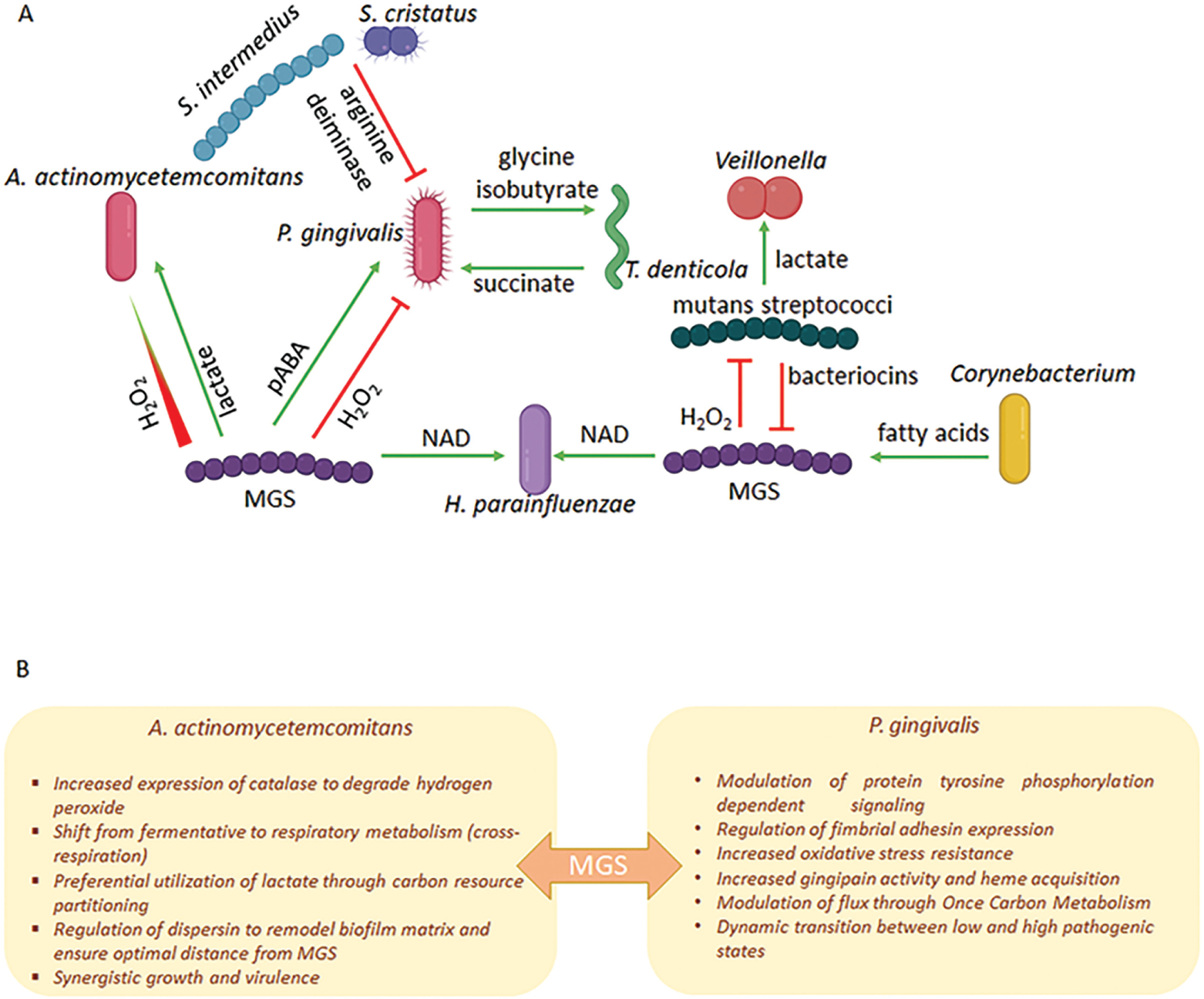

Polymicrobial synergy among the constituent organisms of spatially constrained communities may arise from multiple distinct interspecies interactions, such as provision of attachment sites, nutritional cross-feeding and processive degradation of complex substrates (Lamont et al., 2018). A wide range of metabolites are exchanged among oral bacteria and a selection of these are shown in Figure 2A. We will focus here on some illustrative examples (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. (A) Metabolic interactions among oral bacteria.

Green arrows represent a synergistic relationship whereby the metabolite increases the colonization, growth, or pathogenicity of a partner species. Red flat arrows represent a converse antagonistic relationship. The nature of the exchange may depend on a concentration gradient as depicted in the H2O2 interaction between Mitis Group Streptococci (MGS) and A. actinomycetemcomitans. MGS include the species S. gordonii, S. sanguinis, S. parasanguinis and S. mitis. (B) Outcomes of the interaction between MGS and A. actinomycetemcomitans or P. gingivalis.

Porphyromonas gingivalis and Streptococcus gordonii are synergistically pathogenic in animal models of periodontal disease (Daep et al., 2011; Kuboniwa et al., 2017). However, this seemingly straightforward outcome belies a more nuanced and dynamic interspecies interaction. Perception of S. gordonii metabolites, in particular para-amino benzoic acid (pABA), by P. gingivalis begins before the organisms are physically connected. pABA is an essential substrate of one carbon metabolism (OCM) and can enter or leave bacterial cells by passive diffusion. Exogenous pABA is salvaged by P. gingivalis resulting in downregulation of the endogenous pABA synthesis pathway (Kuboniwa et al., 2017). OCM is a complex network of biochemical reactions involving methyl group transfers, that mediates delivery of one-carbon units to anabolic pathways including biosynthesis of DNA, proteins, and lipids (Shetty and Varshney, 2021). Optimal OCM activity requires maintenance of a balance of carbon flux, and a range of compensatory mechanisms exist to regulate enzyme activity and maintain this balance when substrate concentrations vary (Troesch et al., 2016). In P. gingivalis, excess pABA inactivates a low-molecular-weight tyrosine phosphatase Ltp1, which is a component of phosphotyrosine signaling network (Jung et al., 2019). Ltp1 and a cognate tyrosine kinase, Ptk1, are a mutually interdependent axis of this network, and inhibition of Ltp1 disrupts information flow through the network. Among the substrates of phosphotyrosine signaling are the gingipain proteases, and tyrosine phosphorylation is required for gingipain processing and activity (Nowakowska et al., 2021). As amino acids are also essential substrates for OCM, a reduction in protease activity will reduce intracellular amino acid levels and slow OCM. Thus, while most likely primarily a mechanism to restrict amino acid availability and maintain one carbon balance, reduced gingipain activity will impact P. gingivalis pathogenicity as gingipains are key virulence factors. pABA can thus be considered as a brake on P. gingivalis-S. gordonii community pathogenicity, and indeed in the presence of exogenous pABA, alveolar bone loss induced by P. gingivalis in an animal model is impaired (Kuboniwa et al., 2017). This is a dynamic interaction however, and, following co-adhesion with P. gingivalis, there is transcriptional downregulation of PabC, a pABA synthesis enzyme in S. gordonii. Diminished pABA production releases the brake on pathogenicity and physically integrated P. gingivalis-S. gordonii communities become synergistically pathogenic (Kuboniwa et al., 2017).

Another streptococcal metabolite which can have a major impact on community properties is hydrogen peroxide, which is toxic to anaerobes such as P. gingivalis. Hence in oxygenated areas of oral biofilms, particularly on supragingival tooth surfaces, streptococci are antagonistic to P. gingivalis, and consequently often associated with gingival health. In addition to its inherent cellular toxicity, peroxide can operate as a signaling molecule (Redanz et al., 2018). In one well-documented system, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans responds to peroxide by activation of the OxyR transcriptional regulator which can increase levels of the ApiA surface protein associated with survival in vivo. OxyR also controls production of the KatA catalase, thus affording protection from hydrogen peroxide produced by both streptococci and neutrophils (Ramsey et al., 2011; Ramsey and Whiteley, 2009). Additionally, OxyR regulates synthesis of dispersin B (DspB), an enzyme that degrades the biofilm matrix and allows A. actinomycetemcomitans to maintain a ‘safe’ distance from streptococci where exposure to peroxide is minimized without impeding utilization of streptococcal lactate, a preferred carbon source (Stacy et al., 2014). The interaction has a reciprocal component as A. actinomycetemcomitans promotes community development by fine-tuning peroxide production from some streptococcal species through regulating expression of pyruvate oxidase (Duan et al., 2016). In response to the peroxide-mediated increase in bioavailability of oxygen, A. actinomycetemcomitans shifts from primarily fermentative to respiratory metabolism (Stacy et al., 2016), which enhances its growth and fitness in vivo. The collective outcome of these complex and dynamic interbacterial interactions is synergistic pathogenicity (Stacy et al., 2014).

In addition to its interspecies role with a periodontal pathogen, streptococcal peroxide signaling has a range of outputs relevant for both single species accumulation and interactions with other oral microbial inhabitants. Peroxide can bolster persistence of the producing species through inducing release of extracellular (e)DNA, a major constituent of extracellular polymeric substance and which can serve as a source for horizontal gene transfer (Itzek et al., 2011). Peroxide produced by some mitis group streptococci (MGS) antagonizes the growth of the cariogenic niche-competitor S. mutans (Cheng et al., 2020), which can affect their spatial arrangement (Kim et al., 2020). Interestingly, some streptococcal species mitigate this antagonism by releasing pyruvate which detoxifies peroxide (Cheng et al., 2020; Redanz et al., 2020). Considering that both peroxide and pyruvate release are subject to carbon catabolite repression, this is clearly a finely balanced system, likely only operational in specific contexts. Resistance to peroxide, however, may be a prerequisite for organisms that exist in close proximity to MGS. Haemophilus parainfluenzae, for example, possess a highly redundant, multifactorial peroxide resistance mechanism controlled by the OxyR transcriptional regulator (Perera et al., 2022). MGS provide NAD for H. parainfluenzae and also regulates carbon utilization, a benefit that may outweigh the cost of peroxide detoxification.

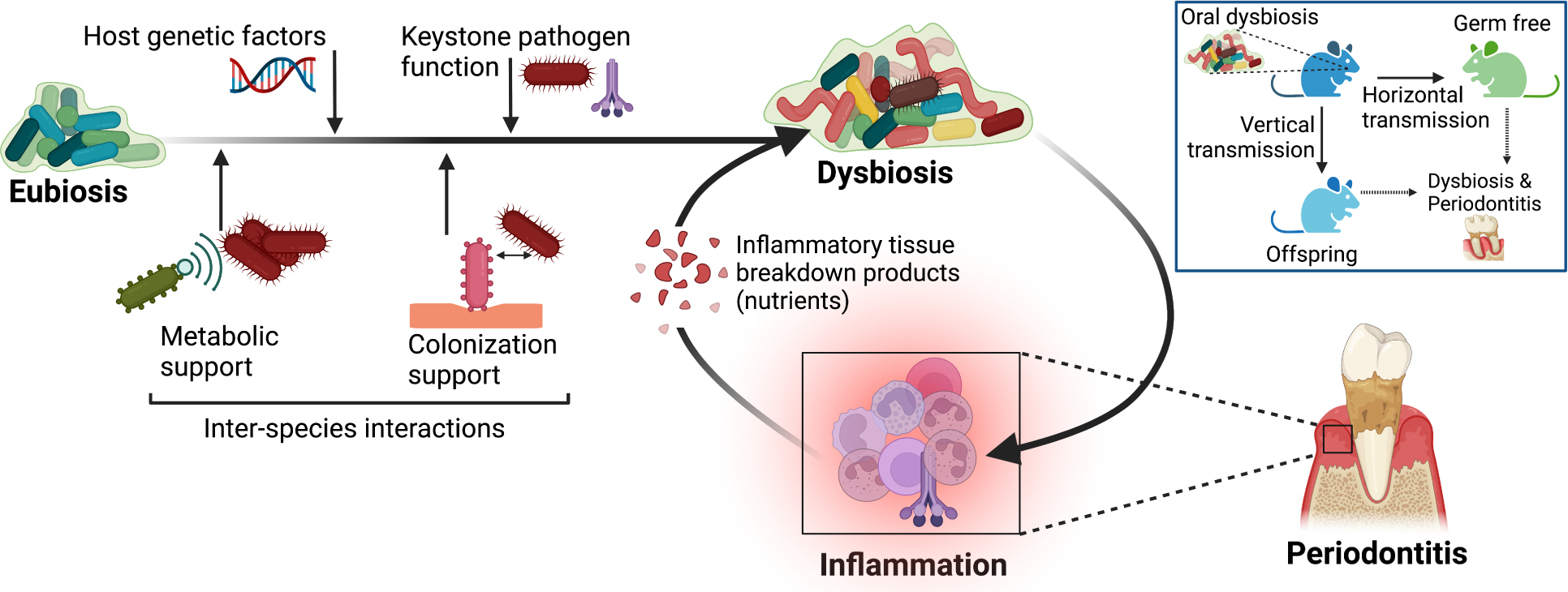

The dysbiosis-inflammation rachet

According to predictions of the polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis model, periodontitis is driven by reciprocally reinforced interactions between a polymicrobial dysbiotic community and an exaggerated host inflammatory response (Lamont et al., 2018) (Figure 3). Inflammation is a major ecological factor underlying the characteristic shift in the microbial population structure associated with periodontal disease progression. An inflammatory environment exerts selective pressure on the community organization, in part by providing nutrients derived from inflammatory tissue breakdown that favor the expansion of inflammophilic pathobionts (Lamont et al., 2018). However, whether the dysbiotic microbiome constitutes a direct cause of inflammatory pathology or is merely the consequence of a nutritionally favorable inflammatory environment has been formally addressed only recently through controlled microbiome transfer experiments. Based on earlier studies that the keystone pathogen P. gingivalis manipulates complement function to promote oral microbial dysbiosis (Hajishengallis et al., 2011; Maekawa et al., 2014), a recent investigation showed that the P. gingivalis-induced dysbiotic microbiome can be stably transferred to germ-free mice, which thereby develop periodontitis (Payne et al., 2019). The same study demonstrated that the P. gingivalis-induced dysbiotic microbiome can also be transmitted vertically from parents to their offspring, which exhibit significant bone loss relative to the offspring of periodontally healthy mice (Figure 3). Whereas antibiotic therapy reversed dysbiosis of the periodontal microbiome (with regard to both microbial load and community structure) in P. gingivalis-challenged mice, the dysbiotic state was readily restored upon termination of the treatment (Payne et al., 2019). Therefore, a dysbiotic microbiome is inherently resilient and is a transmissible cause of periodontal disease. Importantly, a dysbiotic microbiome is a prerequisite for the interleukin (IL)-23-dependent expansion of IL-17-secreting CD4+ T cells (Th17) cells, which drive inflammatory periodontal bone loss in both mice and humans (Dutzan et al., 2018).

Figure 3. The interconnection of dysbiosis with inflammation as a disease driver.

Periodontitis results from reciprocally reinforced interactions between a dysbiotic microbiome and the host inflammatory response (Lamont et al., 2018). A dysbiotic microbiome can be stably transferred from diseased mice both vertically (to their offspring) and horizontally (to germ-free mice) and initiate periodontal disease (Payne et al., 2019). Inflammation exacerbates and sustains dysbiosis by creating a nutritionally favorable environment (e.g., tissue breakdown products such as degraded collagen and heme-containing compounds), thus supporting the chronification of the disease. Besides inflammation, other factors that contribute to the transformation of a eubiotic (in balance with the host) microbial community to a dysbiotic one, include host genetic factors, interspecies interactions that promote the colonization and metabolic support of keystone and pathobiont species, and keystone pathogen functions, such as subversion of host immunity (Hashim et al., 2021; Hoare et al., 2021; Maekawa et al., 2014).

Evidence of whether dysbiosis can precede periodontitis in humans is challenging to obtain. A subgingival microbial dysbiosis index (SMDI) was recently developed based on machine learning analysis of published 16S microbiome data. SDMI could accurately discriminate between periodontal disease and health but also identified a subset of samples from healthy sites with relatively high SMDI (Chen et al., 2022). Given that apparently ‘clinically healthy’ sites are not necessarily free of on-going inflammatory activity, these might represent sites of dysbiosis progressing to disease or with increased risk of developing disease. In this regard, a metatranscriptomic study assessed longitudinal changes in progressing and nonprogressing subgingival tooth sites (i.e., with or without increasing pocket depth and clinical attachment loss). The analysis showed that oral microbial communities in progressing sites are metabolically distinct from those in nonprogressing sites and that the differences are detectable prior to disease progression. Specifically, the progressing sites displayed enrichment of functional signatures associated with pathogenesis, including oxidative stress response, amino acid transport, ferrous iron transport, lipid A biosynthesis, and cell motility (Yost et al., 2015). Whether these functional changes alter the spatial organization of the microbial communities in the diseased sites need further elucidation.

Whereas the species that expand during periodontitis have been thought of as inflammophilic pathobionts, i.e., they exploit the altered ecological conditions to flourish and exacerbate inflammatory tissue damage (Lamont et al., 2018), a recent study suggested that organisms thriving in dysbiosis may not necessarily be pathogenic (Chipashvili et al., 2021). Although the obligate epibionts Saccharibacteria are correlated with dysbiosis and their counts increase in periodontitis, these organisms were shown to attenuate the pathogenicity (and hence proinflammatory potential) of their host bacteria in an in vivo model of periodontitis (Chipashvili et al., 2021). This intriguing finding has created a conundrum in that Saccharibacteria depend on dysbiosis for their growth, yet their anti-inflammatory action antagonizes dysbiosis and their microbial hosts, while favoring the mammalian host.

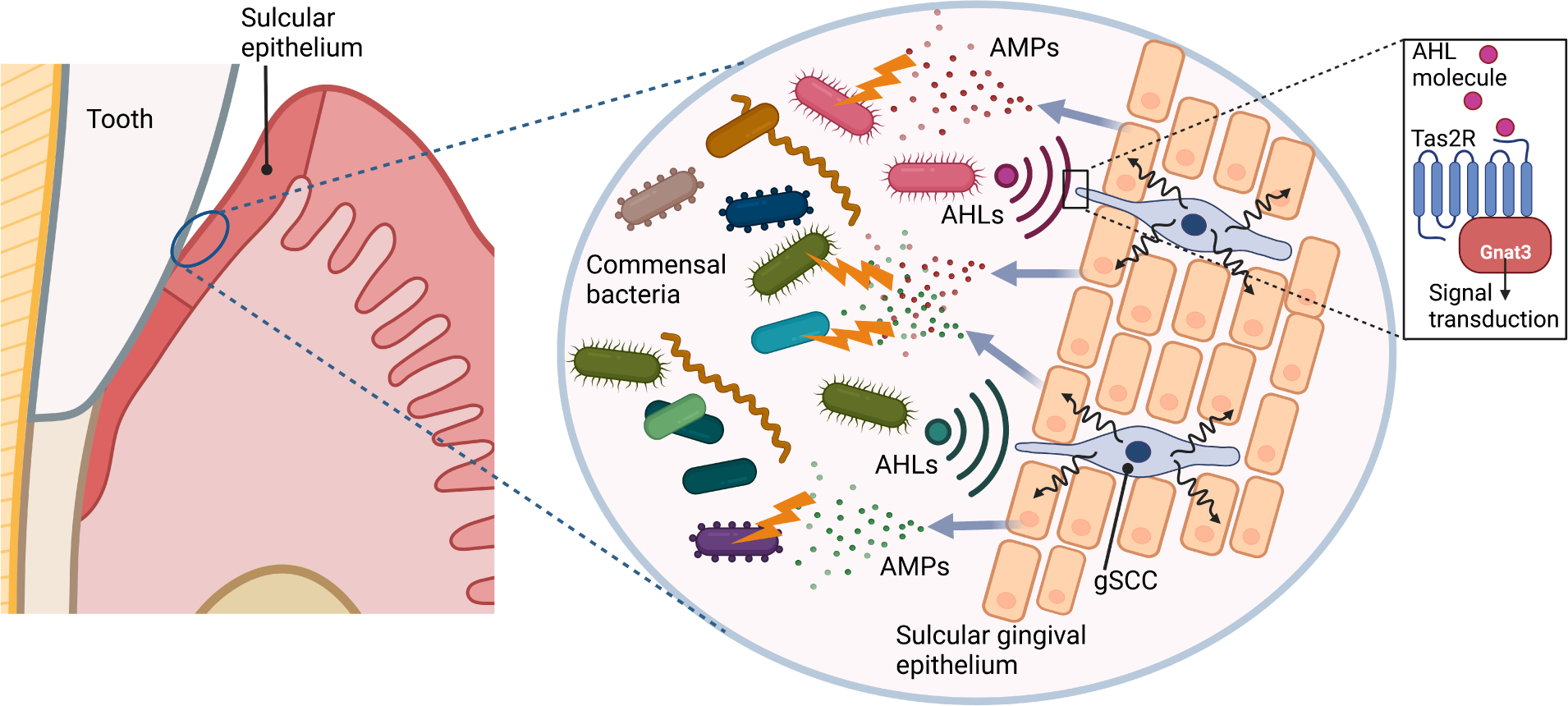

An unexpected player in the control of oral microbial dysbiosis was recently shown to be tastesignaling receptors that are expressed also on non-lingual epithelia. Gingival solitary chemosensory cells (gSCCs) in the sulcular and junctional epithelium use bitter taste receptors to detect bacterial metabolites (e.g., quorum-sensing acylated homoserine lactones), resulting in the release of antimicrobial peptides that regulate the oral microbiome both quantitatively and qualitatively (Zheng et al., 2019) (Figure 4). Genetic ablation of taste signaling molecules in this pathway, such as α-gustducin (Gnat3), or genetic absence of gSCCs in mice causes dysbiosis and increased periodontal inflammation and bone loss in both spontaneous and induced models of periodontitis (Zheng et al., 2019).

Figure 4. Gingival solitary chemosensory cells promote host-microbe homeostasis in the periodontium.

Gingival solitary chemosensory cells (gSCCs) express bitter taste receptors (Tas2r) and are present also in the sulcular and junctional epithelia, where they can detect quorum-sensing acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) molecules released from periodontal bacteria. Activation of Tas2r in gSCCs leads to the induction of antimicrobial proteins (AMPs). This activity is required for host-microbe homeostasis, since genetic ablation of a Tas2r-associated signaling component (α-gustducin; Gnat3) causes dysbiotic alterations to the indigenous microbiota and naturally occurring periodontal bone loss (Zheng et al., 2019).

Metabolic products, such as succinate, are elevated in human periodontitis through production by either host cells or members of the microbial community. In mice, elevation of succinate aggravated dysbiosis and inflammatory periodontal bone loss and these effects were reversed by genetic or pharmacological ablation of the succinate receptor-1 (Guo et al., 2022).

Consistent with the bidirectional relationship between the microbiome and the host response, the periodontal microbiome undergoes significant quantitative and qualitative changes in the absence of neutrophils from the periodontal tissue. Mice lacking the chemokine receptor CXCR2, hence defective in neutrophil recruitment, develop an altered periodontal microbiome and spontaneous inflammatory bone loss relative to wild-type (CXCR2+/+) littermate controls (Hashim et al., 2021). Interestingly, the altered oral microbiome of CXCR2−/− mice is not stable upon transfer to CXCR2+/+ germ-free mice and fails to transmit the disease phenotype of the donors to the recipients (Hashim et al., 2021). Thus, besides environmental factors, the immunogenetic background of the host can influence the composition and hence pathogenicity of the mouse oral microbiome, as seen with the human oral microbiome which is similarly dictated, in part, by host genetics (Gomez et al., 2017).

As mentioned above, periodontal inflammation fuels the expansion of pathobionts that feed off the ‘spoils’ of tissue destruction. A systemic inflammatory disease could, at least in principle, modulate the periodontal microbiome by elevating the inflammatory burden on the periodontal tissue (Figure 5). Accordingly, the oral microbiome of patients with a systemic disease (e.g., diabetes or rheumatoid arthritis) is distinct from that of healthy controls, being enriched in periodontitis-associated species (Teles et al., 2021). Overall, these developments reinforce the notion that periodontitis is driven by a self-sustained feed-forward loop between a dysbiotic microbiome and inflammation, consistent with the chronicity of the disease.

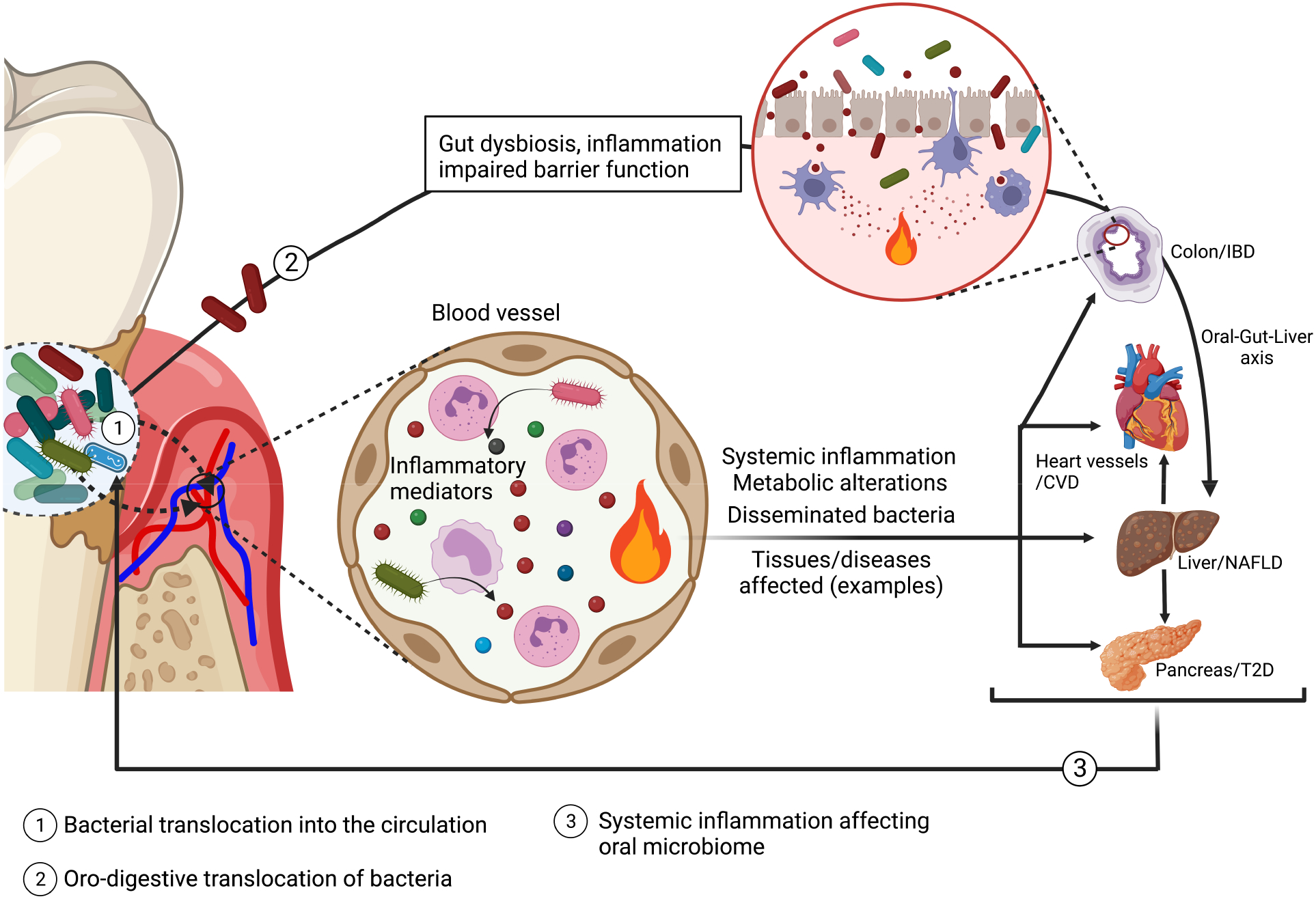

Figure 5. Oral microbiome and extra-oral inflammatory conditions.

In periodontal disease, the ulceration of periodontal pockets facilitates the translocation of bacteria into the circulation, leading to bacteremia (and potentially bacterial dissemination to systemic tissues), systemic inflammation and metabolic alterations, which can affect comorbid conditions, such as, cardiovascular disease (CVD), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and Type 2 diabetes (T2D). Oral pathobionts swallowed via the oro-digestive route can translocate to the colon, where they can aggravate inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in susceptible hosts, by activating local inflammatory responses, promoting dysbiosis and compromising barrier function (Kato et al., 2018; Kitamoto et al., 2020; Xing et al., 2022). This in turn may lead to endotoxemia, changes to the blood metabolome, and liver pathology (oral-gut-liver axis) (Imai et al., 2021; Xing et al., 2022; Yamazaki et al., 2021). Periodontitis-associated systemic comorbidities, in turn, increase the systemic inflammatory burden which can exacerbate microbial dysbiosis in the periodontium (Teles et al., 2021).

Oral pathobionts in extraoral diseases

In periodontitis, oral bacteria and their products can pass into the circulation via the ulcerated periodontal pocket epithelium. The resulting transient bacteremias can cause inflammatory, metabolic and functional complications (e.g., elevated inflammatory cytokines, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, endothelial dysfunction, alterations in bone marrow myelopoiesis), which may underlie the association of this oral disease with systemic comorbidities (Hajishengallis and Chavakis, 2021) (Figure 5). Periodontitis-associated bacteremias can be frequent, being caused not only by professional dental care such as probing and biofilm debridement but also by daily activities such as mastication and toothbrushing, and indeed approximately half of bloodborne bacteria species are of oral origin (Emery et al., 2021).

Bacteremias can also be caused by severe dental caries that leads to infection of the pulp, which is rich in blood vessels. In this regard, serotype k strains of S. mutans appear to cause infective endocarditis in patients with underlying heart disease (Abranches et al., 2018).

Bloodborne oral bacteria may infiltrate extra-oral tissues and organs. For instance, P. gingivalis DNA and its major virulence factors, the gingipain proteases, have been detected in the brain of Alzheimer disease (AD) patients and shown to correlate with markers of AD pathology (Dominy et al., 2019). Oral inoculation of aged mice with P. gingivalis resulted in brain infiltration with this organism causing neuroinflammation and increased levels of amyloid beta (Aβ) in a gingipain-dependent manner (Dominy et al., 2019). Using an amyloid precursor protein knock-in mouse model of AD, another study showed that orally inoculated P. gingivalis caused complement-dependent neuroinflammation, accelerated Aβ accumulation and aggravated behavioral and cognitive impairment. The presence of the pathogen in the brain of mice was inferred by detection of P. gingivalis-specific genes (hmuY and 16S rRNA) (Hao et al., 2022). Apparently, P. gingivalis can cross the blood-brain barrier and infiltrate the brain, although the mechanism is poorly understood. At least in vitro, secreted gingipains can degrade tight junction proteins and increase the permeability of human cerebral microvascular endothelial cells, thus potentially disrupting the blood-brain barrier and facilitating access of P. gingivalis to the brain (Nonaka et al., 2022).

Periodontal bacteria may also disseminate non-hematogenously via either the oro-pharyngeal or oro-digestive route. Oro-pharyngeal aspiration of bacteria is a major cause of pneumonia in immunocompromised or elderly individuals and the dysbiotic oral biofilm is considered a pathogen reservoir for respiratory infections and exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Mammen et al., 2020). Recent preclinical studies showed that, under certain conditions, oral organisms may ectopically colonize the gut, where they instigate inflammation, alter the local microbial composition and compromise gut barrier function; these alterations may not only exacerbate colitis in susceptible hosts, but may also promote endotoxemia and systemic inflammation (Kato et al., 2018; Kitamoto et al., 2020; Xing et al., 2022) (Figure 5). Moreover, in the context of obesity, high-fat diet-fed mice subjected to experimental periodontitis display dysbiosis in the intestine associated with increased purine degradation activity that leads to increased uric acid serum levels (Sato et al., 2021). Such gut dysbiosis-mediated systemic effects (endotoxemia and alterations to the serum metabolome) resulting from periodontitis are integral to the so-called oral-gut-liver axis, which can fuel hepatic inflammation and steatosis, thereby aggravating non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (Imai et al., 2021; Xing et al., 2022; Yamazaki et al., 2021) (Figure 5).

Although oral microbes are swallowed in great numbers daily, they are typically poor colonizers of the healthy gut due to colonization resistance by the resident microbiota. However, certain pathological conditions that disrupt gut homeostasis, such as inflammatory bowel disease, liver cirrhosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or colon cancer, facilitate intestinal colonization of oral bacteria (Chen et al., 2021; Schirmer et al., 2018; Yachida et al., 2019). Indeed, many highly abundant species associated with pediatric Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis (e.g., Fusobacteriaceae and Veillonellaceae) are derived from the oral cavity (Gevers et al., 2014; Schirmer et al., 2018). Consistently, ectopic colonization of the mouse intestine by oral pathobionts and consequent exacerbation of colitis required pre-existing intestinal inflammation or IL-10 deficiency, a condition that predisposes to increased susceptibility to colitis (Kitamoto et al., 2020). Mechanistically, ectopically colonized oral pathobionts aggravate colitis by inducing IL-1β release from intestinal macrophages and by activating Th17 cell responses (Kitamoto et al., 2020). Specifically, oral pathobiont-reactive Th17 cells that expand during experimental periodontitis migrate via the lymphatic circulation to the intestine, where they are activated by ectopically colonized oral bacteria upon antigen-presenting cell processing and presentation of specific antigens thereof (Kitamoto et al., 2020). Conversely, oral pathobiont-responsive Th17 cells of gut origin can migrate to the oral cavity where they aggravate experimental periodontitis (Nagao et al., 2022), lending support to the bidirectional association between periodontitis and colitis. This is a general concept underlying additional comorbidities. For instance, recent work in preclinical models showed that periodontitis-induced systemic inflammation exacerbated arthritis via maladaptive epigenetic alterations in bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors and, conversely, arthritis aggravated periodontitis through the same mechanism (Li et al., 2022). At least in the mouse host, the ability of a model oral pathobiont to colonize the inflamed gut involved adaptation for expression of distinct virulence genes from those required for oral colonization (Guo et al., 2022). Veillonella parvula, which is enriched in the gut of patients with inflammatory bowel disease, was shown to adapt in the setting of experimental colitis in mice by exploiting inflammation-derived nitrate; nitrate respiration, through the narGHJI operon, promotes its growth and hence ability for ectopic colonization of the gut (Rojas-Tapias et al., 2022).

The gut microbiota of patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) is enriched in bacterial species derived from the oral cavity (e.g., Fusobacterium nucleatum, Parvimonas micra, Peptostreptococcus stomatis, Peptostreptococcus anaerobius, and Solobacterium moorei), which are moreover suspected to contribute to CRC pathogenesis (Yachida et al., 2019). The metagenomic/epidemiological and experimental evidence is particularly strong for F. nucleatum, which was linked to CRC progression via different mechanisms; these include its ability to stimulate CRC cell proliferation and metastasis, promote a tumor-permissive immune microenvironment by recruiting myeloid-derived suppressor cells, and trigger immune checkpoints that inhibit the anti-tumor activity of cytotoxic lymphocytes (Alon-Maimon et al., 2022). Two important F. nucleatum virulence factors are the lectin Fap2, which confers tropism for CRC cells and activates the inhibitory immunoreceptor TIGIT, and the adhesin FadA, which stimulates CRC cell proliferation and the release of prometastatic chemokines (Alon-Maimon et al., 2022). More recent evidence indicates that F. nucleatum supports tumorigenesis also by increasing glucose metabolism in CRC cells via upregulation of long non-coding RNA enolase1-intronic transcript 1. This finding is consistent with the clinical correlation between F. nucleatum abundance and high glucose metabolism (18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake) in CRC patients (Hong et al., 2021). Whether F. nucleatum can also initiate tumorigenesis in CRC is uncertain, although it was shown to cause DNA double-strand breaks at least in oral cancer cells (Geng et al., 2019).

Ectopic gut relocation of oral species might also contribute to autoimmune pathology. The oral commensal Actinomyces massiliensis, which expresses an orthologue of the lupus autoantigen Ro60, can colonize the gut of systemic lupus erythematosus patients (Chen et al., 2021). Germ-free mice colonized with autoantigen Ro60 ortholog-expressing commensal bacteria developed glomerular immune complex deposits mimicking lupus nephritis (Greiling et al., 2018). Therefore, ectopic oral bacteria, such as A. massiliensis, might potentially initiate and sustain autoimmunity in susceptible individuals via cross-reactivity.

Therapeutic strategies

The interactions of complex polymicrobial communities with host and environmental factors (e.g., immunity and diet) that promote dysbiosis and nososymbiocity provide enormous challenges for therapeutic interventions. The multifaceted nature of community development, spatial structure, and pathogenesis, combined with drug tolerance mechanisms complicate treatment options, and conventional antimicrobial elimination has proved difficult, requiring effective multitargeted approaches (Koo et al., 2017). The presence of a fluid phase that can inactivate bioactive molecules and the difficulty of accessing different oral sites where the disease occurs, along with poor retention of topically delivered agents, pose additional challenges (Lamont et al., 2018). These unique hurdles, however, also offer opportunities for the development of innovative and effective therapies targeting these complex biological traits and protected oral sites to prevent or disrupt pathogenic communities. In-depth reviews have assessed current approaches, including antimicrobial rinses and host-modulation therapies (Arweiler, 2021; Golub and Lee, 2020; Hajishengallis et al., 2020). Novel approaches targeting the biofilm structure and microenvironment in caries and inflammatory responses in periodontitis have been recently investigated in humans.

A randomized crossover study shows that ferumoxytol iron oxide nanoparticles (FerIONP), an FDA-approved formulation for treating iron deficiency, exerts antibiofilm activity and suppresses tooth enamel decay when applied topically in an intraoral human disease model (Liu et al., 2021). Interestingly, FerIONP exhibits intrinsic catalytic (peroxidase-like) activity at acidic pH values and binds to biofilms (but poorly to oral tissues) following topical treatment. Further analysis indicates that FerIONP induces bacterial killing and EPS matrix degradation through in situ free-radical generation via the catalytic activation of hydrogen peroxide under cariogenic (acidic) conditions. This selective binding and pH-dependent activation inhibits biofilm formation and tooth enamel demineralization in the human mouth without affecting commensal bacteria or oral tissues. Neither adverse signs in the oral cavity nor systemic reactions were observed during treatment. As iron deficiency anemia is associated with severe dental caries, it opens the possibility to employ these FDA-approved nanoparticles for caries prevention tailored to high-risk patients, addressing both oral and systemic health conditions.

Implicit in the above-discussed feed-forward loop linking dysbiosis and inflammation via reciprocally reinforced interactions that drive periodontitis (Figure 3) is the notion that periodontitis could be controlled by targeting either dysbiosis or inflammation. In the latter regard, a promising treatment option is the use of a complement-targeted drug (AMY-101) which showed safety and efficacy in a recent double-blind and placebo-controlled phase 2a trial in patients with periodontal inflammation (Hasturk et al., 2021).

Conclusions and perspective

All life exists in context. The microbes of the oral cavity exist in complex, spatially distinct polymicrobial communities, in which information is exchanged among the constituents. The nature of the interface between these communities and the host has fundamentally altered our understanding of oral microbial pathogenicity. Classical notions of the importance of the presence/absence of individual species, or of a threshold number, have been replaced with the concept of nososymbiocity, whereby the collective properties of communities dictate their contribution to a homeostatic or dysbiotic relationship with the host. Notably, the spatial configuration of organisms is also a driver of nososymbiocity. These outputs are dynamic and communities can transition between states of high or low nososymbiocity as metabolic cues or spatial orientations develop. Targeting the structural organization or perturbing the dynamics of microbial community spatial configuration, or interfering with environmental factors (e.g., inflammation) that promote the dysbiotic transformation of the community, can advance treatment strategies. Also obsolete is the idea that the microbial strategy for resisting the immune response is based on concealment and evasion. Rather, successful periodontal colonizers manipulate and feed off the inflammatory reactions that can no longer exert control. The reach of oral microbes extends beyond the oral cavity as local dysbiotic immune responses can have systemic manifestations. Additionally, the skill sets that allow microorganisms to thrive in the continually inflamed oral tissues also facilitates hematogenous spread and colonization of remote sites. As our grasp of the intersection between oral microbes and the host increases, so too does the potential for intervention based on tipping the axis away from dysbiosis to restore a healthy state. Technological advances such as real-time microscopy-spectroscopy and spatial transcriptomics of biofilms at single-cell resolution (Dar et al., 2021; Shi et al., 2020) provide exciting opportunities to assess the function of structured communities and the creation of pathological niches in real time and space. It will also be interesting to elucidate how changes in global microbiome composition and activity caused by host diet or immunity affect the spatial structure of the polymicrobial community longitudinally across different sites, individuals, and length-scales. Further understanding of the interplay between biogeography and virulence, and how it coordinates the pathogenesis spatiotemporally may reveal unique ‘virulence hotspots’ as well as precise therapeutic targets.

Acknowledgements

Research in the authors’ laboratories is supported by NIH/NIDCR grants: DE028561, DE029436, DE026152 and DE031206 (to G.H.); DE025220 and DE025848 (to H.K); and DE011111, DE012505 DE023193, and DE031756 (to R.J.L). We thank Dr. Zhi Ren for creating Figure 1. All figures were created using Biorender.com. Due to space constraints, we regret that we could not cite all relevant studies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interests

GH is inventor of a patent that describes the use of complement inhibitors in periodontal disease (“Methods of Treating or Preventing Periodontitis and Diseases Associated with Periodontitis”; patent no. 10,668,135). H.K. is inventor of a patent titled “Iron Oxide Nanoparticles and Methods of Use Thereof” (patent no. 62,115,968). RJL is inventor of a patent titled “Bacterial Inhibitors” (patent no. 11,504,414).

References

- Abranches J, Zeng L, Kajfasz JK, Palmer SR, Chakraborty B, Wen ZT, Richards VP, Brady LJ, and Lemos JA (2018). Biology of Oral Streptococci. Microbiol Spectr 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alon-Maimon T, Mandelboim O, and Bachrach G (2022). Fusobacterium nucleatum and cancer. Periodontol 2000 89, 166–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arweiler NB (2021). Oral Mouth Rinses against Supragingival Biofilm and Gingival Inflammation. Monogr Oral Sci 29, 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JL, Bor B, Agnello M, Shi W, and He X (2017). Ecology of the Oral Microbiome: Beyond Bacteria. Trends Microbiol 25, 362–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen WH, Burne RA, Wu H, and Koo H (2018). Oral Biofilms: Pathogens, Matrix, and Polymicrobial Interactions in Microenvironments. Trends Microbiol 26, 229–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B. d., Jia X. m., Xu J. y., Zhao L. d., Ji J. y., Wu B. x., Ma Y, Li H, Zuo X. x., Pan W. y., et al. (2021). An Autoimmunogenic and Proinflammatory Profile Defined by the Gut Microbiota of Patients With Untreated Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthr Rheumatol 73, 232–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Marsh PD, and Al-Hebshi NN (2022). SMDI: An Index for Measuring Subgingival Microbial Dysbiosis. J Dent Res 101, 331–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X, Redanz S, Treerat P, Qin H, Choi D, Zhou X, Xu X, Merritt J, and Kreth J (2020). Magnesium-Dependent Promotion of H2O2 Production Increases Ecological Competitiveness of Oral Commensal Streptococci. J Dent Res 99, 847–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipashvili O, Utter DR, Bedree JK, Ma Y, Schulte F, Mascarin G, Alayyoubi Y, Chouhan D, Hardt M, Bidlack F, et al. (2021). Episymbiotic Saccharibacteria suppresses gingival inflammation and bone loss in mice through host bacterial modulation. Cell Host Microbe 29, 1649–1662.e1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Ren Z, Divaris K, Roach J, Lin B, Lin C, Azcarate-Peril A, Simancas-Pallares M, Shrestha P, Orlenko A, et al. (2022). Pathobiont-mediated spatial structuring enhances biofilm virulence in childhood oral disease. Research Square [ 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1748651/v1]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daep CA, Novak EA, Lamont RJ, and Demuth DR (2011). Structural dissection and in vivo effectiveness of a peptide inhibitor of Porphyromonas gingivalis adherence to Streptococcus gordonii. Infect Immun 79, 67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar D, Dar N, Cai L, and Newman DK (2021). Spatial transcriptomics of planktonic and sessile bacterial populations at single-cell resolution. Science 373, eabi4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divaris K (2019). Searching Deep and Wide: Advances in the Molecular Understanding of Dental Caries and Periodontal Disease. Adv Dent Res 30, 40–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominy SS, Lynch C, Ermini F, Benedyk M, Marczyk A, Konradi A, Nguyen M, Haditsch U, Raha D, Griffin C, et al. (2019). Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci Adv 5, eaau3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Scoffield JA, Zhou X, and Wu H (2016). Fine-tuned production of hydrogen peroxide promotes biofilm formation of Streptococcus parasanguinis by a pathogenic cohabitant Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. Environ Microbiol 18, 40023–44036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutzan N, Kajikawa T, Abusleme L, Greenwell-Wild T, Zuazo CE, Ikeuchi T, Brenchley L, Abe T, Hurabielle C, Martin D, et al. (2018). A dysbiotic microbiome triggers TH17 cells to mediate oral mucosal immunopathology in mice and humans. Sci Transl Med 10, eaat0797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery DC, Cerajewska TL, Seong J, Davies M, Paterson A, Allen-Birt SJ, and West NX (2021). Comparison of Blood Bacterial Communities in Periodontal Health and Periodontal Disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10, 577485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng F, Zhang Y, Lu Z, Zhang S, and Pan Y (2019). Fusobacterium nucleatum Caused DNA Damage and Promoted Cell Proliferation by the Ku70/p53 Pathway in Oral Cancer Cells. DNA Cell Biol 39, 144151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gevers D, Kugathasan S, Denson Lee A., Vázquez-Baeza Y, Van Treuren W, Ren B, Schwager E, Knights D, Song Se J., Yassour M, et al. (2014). The Treatment-Naive Microbiome in New-Onset Crohn’s Disease. Cell Host Microbe 15, 382–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub LM, and Lee HM (2020). Periodontal therapeutics: Current host-modulation agents and future directions. Periodontol 2000 82, 186–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez A, Espinoza JL, Harkins DM, Leong P, Saffery R, Bockmann M, Torralba M, Kuelbs C, Kodukula R, Inman J, et al. (2017). Host Genetic Control of the Oral Microbiome in Health and Disease. Cell Host Microbe 22, 269–278.e263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiling TM, Dehner C, Chen X, Hughes K, Iñiguez AJ, Boccitto M, Ruiz DZ, Renfroe SC, Vieira SM, Ruff WE, et al. (2018). Commensal orthologs of the human autoantigen Ro60 as triggers of autoimmunity in lupus. Sci Transl Med 10, eaan2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Kitamoto S, Caballero-Flores G, Watanabe D, Sugihara K, Núñez G, Alteri CJ, Inohara N, and Kamada N (2022). Site-specific adaptation mechanisms of an oral pathobiont in the oral and gut mucosae. bioRxiv, 2022.2001.2013.476151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, and Chavakis T (2021). Local and systemic mechanisms linking periodontal disease and inflammatory comorbidities. Nat Rev Immunol 21, 426–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Chavakis T, and Lambris JD (2020). Current understanding of periodontal disease pathogenesis and targets for host-modulation therapy. Periodontol 2000 84, 14–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, and Lamont RJ (2016). Dancing with the stars: How choreographed bacterial interactions dictate nososymbiocity and give rise to keystone pathogens, accessory pathogens, and pathobionts. Trends Microbiol 24, 477–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Liang S, Payne MA, Hashim A, Jotwani R, Eskan MA, McIntosh ML, Alsam A, Kirkwood KL, Lambris JD, et al. (2011). Low-abundance biofilm species orchestrates inflammatory periodontal disease through the commensal microbiota and complement. Cell Host Microbe 10, 497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao X, Li Z, Li W, Katz J, Michalek SM, Barnum SR, Pozzo-Miller L, Saito T, Saido TC, Wang Q, et al. (2022). Periodontal Infection Aggravates C1q-Mediated Microglial Activation and Synapse Pruning in Alzheimer’s Mice. Front Immunol 13, 816640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashim A, Alsam A, Payne MA, Aduse-Opoku J, Curtis MA, and Joseph S (2021). Loss of neutrophil homing to the periodontal tissues modulates the composition and disease potential of the oral microbiota. Infect Immun 89, e0030921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasturk H, Hajishengallis G, Forsyth Institute Center for, C., Translational Research, s., Lambris JD, Mastellos DC, and Yancopoulou D (2021). Phase IIa clinical trial of complement C3 inhibitor AMY101 in adults with periodontal inflammation. J Clin Invest 131, e152973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoare A, Wang H, Meethil A, Abusleme L, Hong B-Y, Moutsopoulos NM, Marsh PD, Hajishengallis G, and Diaz PI (2021). A cross-species interaction with a symbiotic commensal enables cell-density-dependent growth and in vivo virulence of an oral pathogen. ISME J 15, 1490–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J, Guo F, Lu SY, Shen C, Ma D, Zhang X, Xie Y, Yan T, Yu T, Sun T, et al. (2021). F. nucleatum targets lncRNA ENO1-IT1 to promote glycolysis and oncogenesis in colorectal cancer. Gut 70, 2123–2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai J, Kitamoto S, and Kamada N (2021). The pathogenic oral-gut-liver axis: new understandings and clinical implications. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 17, 727–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzek A, Zheng L, Chen Z, Merritt J, and Kreth J (2011). Hydrogen peroxide-dependent DNA release and transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in Streptococcus gordonii. J Bacteriol 193, 6912–6922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung YJ, Miller DP, Perpich JD, Fitzsimonds ZR, Shen D, Ohshima J, and Lamont RJ (2019). Porphyromonas gingivalis Tyrosine Phosphatase Php1 Promotes Community Development and Pathogenicity. mBio 10, e02004–02019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T, Yamazaki K, Nakajima M, Date Y, Kikuchi J, Hase K, Ohno H, Yamazaki K, and D’Orazio SEF (2018). Oral Administration of Porphyromonas gingivalis Alters the Gut Microbiome and Serum Metabolome. mSphere 3, e00460–00418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Barraza JP, Arthur RA, Hara A, Lewis K, Liu Y, Scisci EL, Hajishengallis E, Whiteley M, and Koo H (2020). Spatial mapping of polymicrobial communities reveals a precise biogeography associated with human dental caries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117, 12375–12386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, and Koo H (2020). Spatial Design of Polymicrobial Oral Biofilm in Its Native Disease State. J Dent Res 99, 597–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamoto S, Nagao-Kitamoto H, Jiao Y, Gillilland MG III, Hayashi A, Imai J, Sugihara K, Miyoshi M, Brazil JC, Kuffa P, et al. (2020). The Intermucosal Connection between the Mouth and Gut in Commensal Pathobiont-Driven Colitis. Cell 182, 447–462.e414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo H, Allan RN, Howlin RP, Stoodley P, and Hall-Stoodley L (2017). Targeting microbial biofilms: current and prospective therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol 15, 740–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuboniwa M, Houser JR, Hendrickson EL, Wang Q, Alghamdi SA, Sakanaka A, Miller DP, Hutcherson JA, Wang T, Beck DAC, et al. (2017). Metabolic crosstalk regulates Porphyromonas gingivalis colonization and virulence during oral polymicrobial infection. Nat Microbiol 2, 1493–1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladau J, and Eloe-Fadrosh EA (2019). Spatial, Temporal, and Phylogenetic Scales of Microbial Ecology. Trends Microbiol 27, 662–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont RJ, Koo H, and Hajishengallis G (2018). The oral microbiota: dynamic communities and host interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol 16, 745–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Wang H, Yu X, Saha G, Kalafati L, Ioannidis C, Mitroulis I, Netea MG, Chavakis T, and Hajishengallis G (2022). Maladaptive innate immune training of myelopoiesis links inflammatory comorbidities. Cell 185, 1709–1727.e1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Huang Y, Kim D, Ren Z, Oh MJ, Cormode DP, Hara AT, Zero DT, and Koo H (2021). Ferumoxytol Nanoparticles Target Biofilms Causing Tooth Decay in the Human Mouth. Nano Lett 21, 9442–9449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa T, Krauss JL, Abe T, Jotwani R, Triantafilou M, Triantafilou K, Hashim A, Hoch S, Curtis MA, Nussbaum G, et al. (2014). Porphyromonas gingivalis manipulates complement and TLR signaling to uncouple bacterial clearance from inflammation and promote dysbiosis. Cell Host Microbe 15, 768–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammen MJ, Scannapieco FA, and Sethi S (2020). Oral-lung microbiome interactions in lung diseases. Periodontol 2000 83, 234–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark Welch JL, Dewhirst FE, and Borisy GG (2019). Biogeography of the Oral Microbiome: The Site-Specialist Hypothesis. Annu Rev Microbiol 73, 335–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark Welch JL, Ramirez-Puebla ST, and Borisy GG (2020). Oral Microbiome Geography: Micron-Scale Habitat and Niche. Cell Host Microbe 28, 160–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark Welch JL, Rossetti BJ, Rieken CW, Dewhirst FE, and Borisy GG (2016). Biogeography of a human oral microbiome at the micron scale. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113, E791–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean JS, Bor B, Kerns KA, Liu Q, To TT, Solden L, Hendrickson EL, Wrighton K, Shi W, and He X (2020). Acquisition and Adaptation of Ultra-small Parasitic Reduced Genome Bacteria to Mammalian Hosts. Cell Rep 32, 107939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadell CD, Drescher K, and Foster KR (2016). Spatial structure, cooperation and competition in biofilms. Nat Rev Microbiol 14, 589–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao JI, Kishikawa S, Tanaka H, Toyonaga K, Narita Y, Negoro-Yasumatsu K, Tasaki S, AritaMorioka KI, Nakayama J, and Tanaka Y (2022). Pathobiont-responsive Th17 cells in gut-mouth axis provoke inflammatory oral disease and are modulated by intestinal microbiome. Cell Rep 40, 111314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naud S, Ibrahim A, Valles C, Maatouk M, Bittar F, Tidjani Alou M, and Raoult D (2022). Candidate Phyla Radiation, an Underappreciated Division of the Human Microbiome, and Its Impact on Health and Disease. Clin Microbiol Rev 35, e0014021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka S, Kadowaki T, and Nakanishi H (2022). Secreted gingipains from Porphyromonas gingivalis increase permeability in human cerebral microvascular endothelial cells through intracellular degradation of tight junction proteins. Neurochem Int 154, 105282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowska Z, Madej M, Grad S, Wang T, Hackett M, Miller DP, Lamont RJ, and Potempa J (2021). Phosphorylation of major Porphyromonas gingivalis virulence factors is crucial for their processing and secretion. Mol Oral Microbiol 36, 316–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overmyer KA, Rhoads TW, Merrill AE, Ye Z, Westphall MS, Acharya A, Shukla SK, and Coon JJ (2021). Proteomics, Lipidomics, Metabolomics, and 16S DNA Sequencing of Dental Plaque From Patients With Diabetes and Periodontal Disease. Mol Cell Proteomics 20, 100126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne MA, Hashim A, Alsam A, Joseph S, Aduse-Opoku J, Wade W, and Curtis MA (2019). Horizontal and Vertical Transfer of Oral Microbial Dysbiosis and Periodontal Disease. J Dent Res 98, 1503–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera D, McLean A, Morillo-Lopez V, Cloutier-Leblanc K, Almeida E, Cabana K, Mark Welch J, and Ramsey M (2022). Mechanisms underlying interactions between two abundant oral commensal bacteria. ISME J 16, 948–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey MM, Rumbaugh KP, and Whiteley M (2011). Metabolite cross-feeding enhances virulence in a model polymicrobial infection. PLoS Pathog 7, e1002012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey MM, and Whiteley M (2009). Polymicrobial interactions stimulate resistance to host innate immunity through metabolite perception. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 1578–1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redanz S, Cheng X, Giacaman RA, Pfeifer CS, Merritt J, and Kreth J (2018). Live and let die: Hydrogen peroxide production by the commensal flora and its role in maintaining a symbiotic microbiome. Mol Oral Microbiol 33, 337–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redanz S, Treerat P, Mu R, Redanz U, Zou Z, Koley D, Merritt J, and Kreth J (2020). Pyruvate secretion by oral streptococci modulates hydrogen peroxide dependent antagonism. ISME J 14, 1074–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Tapias DF, Brown EM, Temple ER, Onyekaba MA, Mohamed AMT, Duncan K, Schirmer M, Walker RL, Mayassi T, Pierce KA, et al. (2022). Inflammation-associated nitrate facilitates ectopic colonization of oral bacterium Veillonella parvula in the intestine. Nat Microbiol 7, 1673–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Yamazaki K, Kato T, Nakanishi Y, Tsuzuno T, Yokoji-Takeuchi M, Yamada-Hara M, Miura N, Okuda S, Ohno H, and Yamazaki K (2021). Obesity-Related Gut Microbiota Aggravates Alveolar Bone Destruction in Experimental Periodontitis through Elevation of Uric Acid. mBio 12, e0077121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirmer M, Denson L, Vlamakis H, Franzosa EA, Thomas S, Gotman NM, Rufo P, Baker SS, Sauer C, Markowitz J, et al. (2018). Compositional and Temporal Changes in the Gut Microbiome of Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Patients Are Linked to Disease Course. Cell Host Microbe 24, 600–610.e604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shetty S, and Varshney U (2021). Regulation of translation by one-carbon metabolism in bacteria and eukaryotic organelles. J Biol Chem 296, 100088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H, Shi Q, Grodner B, Lenz JS, Zipfel WR, Brito IL, and De Vlaminck I (2020). Highly multiplexed spatial mapping of microbial communities. Nature 588, 676–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy A, Everett J, Jorth P, Trivedi U, Rumbaugh KP, and Whiteley M (2014). Bacterial fight-and-flight responses enhance virulence in a polymicrobial infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, 7819–7824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy A, Fleming D, Lamont RJ, Rumbaugh KP, and Whiteley M (2016). A Commensal Bacterium Promotes Virulence of an Opportunistic Pathogen via Cross-Respiration. MBio 7, e00782–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teles F, Wang Y, Hajishengallis G, Hasturk H, and Marchesan JT (2021). Impact of systemic factors in shaping the periodontal microbiome. Periodontol 2000 85, 126–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troesch B, Weber P, and Mohajeri MH (2016). Potential Links between Impaired One-Carbon Metabolism Due to Polymorphisms, Inadequate B-Vitamin Status, and the Development of Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutrients 8, 803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilbert SA, Mark Welch JL, and Borisy GG (2020). Spatial Ecology of the Human Tongue Dorsum Microbiome. Cell Rep 30, 4003–4015.e4003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing T, Liu Y, Cheng H, Bai M, Chen J, Ji H, He M, and Chen K (2022). Ligature induced periodontitis in rats causes gut dysbiosis leading to hepatic injury through SCD1/AMPK signalling pathway. Life Sciences 288, 120162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yachida S, Mizutani S, Shiroma H, Shiba S, Nakajima T, Sakamoto T, Watanabe H, Masuda K, Nishimoto Y, Kubo M, et al. (2019). Metagenomic and metabolomic analyses reveal distinct stage-specific phenotypes of the gut microbiota in colorectal cancer. Nat Med 25, 968–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki K, Kato T, Tsuboi Y, Miyauchi E, Suda W, Sato K, Nakajima M, Yokoji-Takeuchi M, Yamada-Hara M, Tsuzuno T, et al. (2021). Oral Pathobiont-Induced Changes in Gut Microbiota Aggravate the Pathology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Mice. Front Immunol 12, 766170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost S, Duran-Pinedo AE, Teles R, Krishnan K, and Frias-Lopez J (2015). Functional signatures of oral dysbiosis during periodontitis progression revealed by microbial metatranscriptome analysis. Genome Med 7, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, Tizzano M, Redding K, He J, Peng X, Jiang P, Xu X, Zhou X, and Margolskee RF (2019). Gingival solitary chemosensory cells are immune sentinels for periodontitis. Nat Commun 10, 4496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zijnge V, van Leeuwen MB, Degener JE, Abbas F, Thurnheer T, Gmur R, and Harmsen HJ (2010). Oral biofilm architecture on natural teeth. PLoS One 5, e9321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]