Abstract

Lithium has been used as a treatment for bipolar disorder for over half a century, but there has thus far been no clinical differentiation made between the two naturally occurring stable isotopes (6Li and 7Li). While the natural lithium salts commonly used in treatments are composed of a mixture of these two stable isotopes (approximately 7.59% 6Li and 92.41% 7Li), some preliminary research indicates the above two stable isotopes of lithium may have differential effects on rat behaviour and neurophysiology. Here, we evaluate whether lithium isotopes may have distinct effects on HT22 neuronal cell viability, GSK-3-β phosphorylation in HT22 cells, and GSK-3-β kinase activity. We report no significant difference in lithium isotope toxicity on HT22 cells, nor in GSK-3-β phosphorylation, nor in GSK-3-β kinase activity between the two isotopes of lithium.

Keywords: 6Li, 7Li, Lithium isotopes, GSK-3-β, HT22, Neuronal cells, Quantum mechanisms

Highlights

-

•

Lithium isotopes do not have distinct toxic effects on HT22 neuronal cells.

-

•

Lithium isotopes do not differentially affect GSK-3-β S9 phosphorylation in HT22 cells.

-

•

Lithium isotopes do not differentially reduce GSK-3-β kinase activity.

1. Introduction

Lithium (Li+) is found in nature and is present in small quantities in the natural diets of humans and non-human animals [1]. Despite being present in only tiny amounts, lithium has been linked to human health and neural physiology. There are reports that lithium intake may promote general health in mammalian physiology, with arguments having even been put forward that lithium constitutes an essential micronutrient [2,3]. There is no consensus on optimum lithium ingestion level, but some authors recommend a provisional daily intake of 14.3 μg/kg body weight [4]. Used since the mid 20th century as a treatment for bipolar disorder, natural lithium consists of two stable isotopes of approximately 7.59% 6Li and 92.41% 7Li [5]. So far, the two lithium isotopes that constitute prescribed natural abundance lithium treatments have not been considered as separate medications, but there is some evidence to suggest these two isotopes possibly exert distinct effects on neuronal physiology.

Studies conducted decades ago reported that lithium isotopes appear to have a differential effect on mouse and rat physiology. For example, the median lethal dose (LD50) of 6Li was found to be 13 meq/kg while the LD50 of 7Li was 16 meq/kg in mice [6], though this finding was not confirmed in later research [7]. An early work found the general activity level of 6Li-treated rats to be 50% lower than 7Li- treated rats for a same dosage [8]. That study also reported 6Li concentrations were increased by 25% compared to 7Li in rat erythrocytes, suggesting that the erythrocyte has the capability of distinguishing between the two isotopes [8]. Interestingly, a later study designed to more directly test the difference of the two isotopes on animal behaviour found that 6Li-treated rat mothers were observed to groom and nurse their pups much more than 7Li-treated mothers [9]. Another work, also from the mid 1980s, found that neurons in the rat cerebral cortex sustain 50% higher 6Li concentration than 7Li when an equal dose of each is administered, possibly due to different uptake efficiencies [10].

At the more microscopic cellular and molecular level, lithium also displays a variety of puzzling attributes. Lithium has no known dedicated transporters to cross the cell membrane, but both voltage-gated and non-voltage-gated Na+ channels show approximately equal permeability to Li+ as they do to Na+, thus allowing unregulated passage of Li+ into the cell [11,12]. While there is no known dedicated molecular binding sites for lithium, it is documented that Li+ can compete with Mg2+ in many important biochemical mechanisms [12]. For example, the biologically active form of ATP is complexed with magnesium: Mg2+ forms ionic bonds with the oxygen atoms at either the α and β phosphates or at the β and γ phosphates of the ATP molecule [13]. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations and solid state nuclear magnetic resonance studies show that Li+ can compete with Mg2+ in the ATP-Mg complex as well as at the metal-binding sites of various enzymes [12,14,15]. The DFT calculations indicate that the local atomic arrangement (“shape”) of each enzyme binding site itself influences whether Li+ competes effectively with Mg2+. This is the leading hypothesis as to how Li+ can directly inhibit some enzymes, but not others [15]. In short, Li+ acts as a direct competitive inhibitor of many Mg2+-dependant enzymes [12,16].

One the most prominent enzymes known to be directly inhibited by Li+ is GSK-3-β. GSK-3-β is a regulatory kinase of over 100 different known proteins and is extremely important for cell metabolism and development, particularly through the canonical β-catenin pathway [17,18]. These downstream effects include changes in gene expression affecting cell survival [17,18]. GSK-3-β dysfunction has also been found to be implicated in many diseases including Alzheimer’s Disease [19], type-2 diabetes [20], bipolar disorder [21] as well as some forms of cancer [22]. GSK-3-β seems to be both directly and indirectly inhibited by Li+. Directly, through the interaction of Li+ in the ATP-Mg complex mentioned above and, indirectly, through an increase of phosphorylation of the serine 9 (S9) inhibitory site on GSK-3-β by upstream kinases [23]. Most of these studies used the natural abundance ratio of lithium isotopes, so whether these effects could be attributed to only one isotope is unclear. More recently, lithium has started to attract attention from an entirely different perspective. Specifically, it has been suggested that the two lithium isotopes may have different effects on a quantum mechanical mechanism involving the formation of calcium-phosphate clusters, known as Posner clusters (e.g. through the posited entanglement of phosphorous nuclear spin), and proposed to play a role in neuronal activities [24,25]. Yet another hypothesis suggests that the nuclear spin of the two lithium isotopes may modulate hyperactivity through a radical pair mechanism involving entangled electron spins [26]. At this time, no direct experimental evidence supporting either of these hypotheses has been reported.

The aforementioned effects of lithium on animal physiology, when considered with the possibility of distinct isotope effects, present an obvious and intriguing question as to whether there are significant differences between the actions of lithium isotopes in humans. The latter is especially so when considering the commonplace use of lithium as a medicine in clinical settings. However, the inherent complexities of lithium-isotope phenomena at the human and animal level motivated us to consider simpler systems focused on three initial narrow scope questions. Specifically, we investigated whether lithium isotopes may affect HT22 mouse neuron-derived cell viability, GSK-3-β phosphorylation in HT22 neuron-derived cells, and GSK-3-β kinase activity. The HT22 mouse hippocampal-derived cell model has been used extensively in western blotting and neurotoxicology studies and is quite fast growing, providing a convenient model for this initial foray into lithium isotope effects. We report that, when comparing 6Li-enriched lithium salts (95% 6Li and 5% 7Li) with natural lithium salts (7.6% 6Li and 92.4% 7Li), there are no significant differences in HT22 viability, GSK-3-β phosphorylation and GSK-3-β kinase activity.

2. Materials and methods

Cell culture. HT22 cells are a mouse-derived immortalized secondary cell line subcloned from the HT7 line. HT22 cells were cultured in full growth media [DMEM and HAM's F12 (1:1) (Fisher #SH20361), 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin] at 37 C, 5% CO2 and passaged every 48 h using 0.25% trypsin/0.1% EDTA in a 1:10 dilution.

Cell viability assay [27]. Each lithium isotope-dominant salt was dissolved in ultrapure water at a concentration of 200 mM to create a stock solution. This stock solution was sterile-filtered with a 0.2 μM filter and pH balanced to match the cell media (7.4) using HCl to ensure the lithium carbonate did not upset the physiological pH of the media. These stock lithium isotope solutions were used for both the cell viability assay and western blot. The cells were plated at 8,000 cells/well in a 96-well plate and grown in full growth media for 24 h to 60% confluency. The media in half of the wells was then changed to just DMEM [DMEM and HAM's F12 (1:1) (Fisher #SH20361] and the other half of the wells were changed to neurobasal media containing 5 mM N2 supplement and 5 mM l-glutamine for 24 h. The cells were then immediately treated with lithium isotopes ranging from 8 mM to 32 mM for 24 h. The 6Li-dominant isotope sample contained 95% 6Li2CO3 and 5% 7Li2CO3. The 7Li-dominant isotope sample contained 92% 7Li2CO3 and 8% 6Li2CO3 – the natural 7Li/6Li relative abundance. After 24 h of lithium isotope treatment, the media was removed and changed to phenol-free DMEM/F12 (1:1) with 10% MTT solution. The cells were incubated for 2.5 h at 37C to metabolize the MTT. The cells and formazan crystals were then solubilized with a solution of 90% IPA, 10% Triton X-100, and 0.1 M HCl and the absorbance of each well at 570 nm and 690 nm was determined by spectroscopy. The 690 nm signal was subtracted from the 570 nm signal to account for unmetabolized MTT. All treatment groups were normalized to control and expressed as a ratio of survivability.

ADP-Glo assay by Promega© [28]. The ADP-glow assay was used to quantify the activity of GSK-3-β by ADP-producing enzymatic reaction. The GSK-3-β was diluted in Promega’s ‘reaction buffer A’ to a concentration of 2 ng/mL in a 0.6 mL microcentrifuge tube. The GSK substrate was diluted in ‘reaction buffer A’ to 0.2 mg/mL with 125 mM ATP in a second 0.6 mL microcentrifuge tube. The lithium isotopes, 6Li-dominant and 7Li-dominant, were each diluted to 1.25 mM, 2.5 mM, 5 mM, 10 mM, 20 mM, 40 mM and 80 mM in kinase ‘reaction buffer A’ in 0.6 mL microcentrifuge tubes 3–14 with the pH being adjusted with HCl to remain 7.5 as directed by Promega©. 1 μL of each of the lithium isotope solutions was added to the wells of a 384-well plate, then 2 μL of GSK-3-β solution was added and finally, 2 μL of substrate/ATP mix was added. After 1 h of reaction time at room temperature (as directed by Promega© protocols), the reaction was stopped by the addition of 5 μL of ADP-Glo reagent to each well and left to incubate at room temperature for 40 min. After incubation, 10 mL of “kinase detection reagent” was added and, after 30 min, a microplate reader was used to measure the resulting luminescence. These timepoints were performed as directed by Promega© protocols and resulted in good signal detection [29].

Western blot [30]. The HT22 cells were seeded into a 6-well plate at 160,000 cells/well. After 24 h in full growth media to approximately 40% confluency, the media was changed to neurobasal media containing 5 mM N2 supplement and 5 mM l-glutamine for 24 h. After treatment with lithium isotopes in neurobasal media for another 24 h, the cells were washed with PBS and lysis buffer was added [20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5,150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 30 mM sodium pyrophosphate,1 mM betaglycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate (Na3VO4), 1% triton and 1% Halt Protease and phosphatase inhibitor (Thermo)]. The cell lysates were scraped off the well and homogenized using fine-gauge syringes, then centrifuged at 14,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C. Prior to SDS-PAGE, total protein levels in the samples were measured using a BCA protein assay (Thermofisher Scientific, USA). Samples were heated for 5 min at 90 °C in 3x loading buffer (240 mM Tris-HCl at pH 6.8, 6% w/v SDS, 30% v/v glycerol, 0.02% w/v bromophenol blue, 50 mM DTT, and 5% v/v β-mercaptoethanol) and 15 μg total protein was then loaded into polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were separated in electrophoresis buffer (25 mM Tris base, 190 mM glycine, 3.5 mM sodium dodecyl sulfate), followed by transfer of proteins to a nitrocellulose membrane by electroblotting with transfer buffer (25 mM Tris base, 190 mM glycine, 20% v/v methanol). Membranes were blocked with either 5% non-fat milk (totGSK-3-β and β-actin) or 5% bovine serum albumin (pGSK-3-β) in Tris-buffered saline (20 mM Tris base, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.6) plus 0.1% Tween (TBS-T) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with primary antibody added to blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were washed three times with TBS-T, and then incubated with a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) in blocking buffer for 1 h at room temperature. After this, membranes were washed three additional times with TBS-T. Chemiluminescent substrate (Luminata Crescendo - Millipore) was used to visualise proteins on a Kodak 4000 MM Pro Imaging Station. The images used for analyses were taken from the linear range of exposures, and densitometry was performed using Kodak Molecular Imaging software. The three analyzed proteins were: totGSK-3-β, pGSK-3-β, and β-actin.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Direct Inhibition of GSK-3-β by lithium isotopes

We found no significant difference between the effects of lithium isotopes on GSK-3-β activity at any of the concentrations considered, and the differences between half-maximal inhibition concentrations (IC50s) of 6.883 mM for 6Li and 6.342 mM for 7Li are not statistically significant (Fig. 1). Fig. 1 indicates lithium concentration-dependant inhibition for both curves and correlates well with the known values of lithium inhibition of GSK-3-β [31]. However, these IC50 values are higher than expected in a physiological environment – this is likely explained by higher concentrations of Mg2+ used in our assay [31]. The ADP-Glo assay by Promega© calls for a Mg2+ concentration of 20 mM, while the total amount of magnesium in most animal cells is estimated to be in the range 17–20 mM. Approximately 5 mM is bound to cytosolic ATP, phosphonucleotides in general, and phosphometabolites [32]. Free Mg2+ in cells is estimated to be between 0.5 and 1 mM, with neuronal concentrations around 0.66 mM [33]. Because the Li+ inhibition of GSK-3-β is competitive with Mg2+, it depends on the concentration of free Mg2+ – an increased amount of Mg2+ would result in a decreased inhibitory effect of Li+ and vice-versa [34]. This may limit the direct pertinence of our results when comparing to experimental settings and conditions with physiological levels of magnesium.

Fig. 1.

Direct Inhibition of GSK-3-B by Lithium Isotopes. Data presented as mean + standard error of the mean (SEM) of 5 replicates (N = 5). The x-axis indicates molarity of the Li+ ion (either 6Li or 7Li). The data were fitted to a sigmoidal dose-response curve using Graphpad Prism© and the 6Li R2 = 0.7190 and the 7Li R2 = 0.7052. The half maximal inhibition (IC50) for the 6Li curve was calculated to be 6.883 mM and the IC50 for the 7Li curve was calculated to be 6.342 mM by Graphpad Prism©. The dotted lines surrounding the curves are the 95% confidence intervals. Significant inhibition begins at approximately 4 mM for both curves, however, no significant difference between the lithium isotopes at any concentration was observed, nor any significant difference between the calculated half-maximal inhibition concentrations (IC50s).

3.2. HT22 cell viability as a result of Li+ isotope treatment

To study the effect of Li isotopes on cell viability, we first compared HT22 cells grown in two control media: DMEM and neurobasal. HT22 cells in DMEM and neurobasal medium were either left as negative control (no lithium added) or treated with 6Li or 7Li isotopes. Comparison of the control groups (Fig. 2) indicates that there is no excitotoxicity caused by neurobasal media compared to DMEM. In fact, lithium-free neurobasal has significantly greater cell viability than just lithium-free DMEM (indicated by *). With lithium added, there is no significant lithium toxicity observed in either the DMEM or neurobasal groups, even as the lithium concentration increases. Thus, we conclude that neither lithium isotopes are toxic to HT22 cells up to 32 mM, and there is no detectable difference between the isotopes.

Fig. 2.

HT22 Viability as a Result of Lithium Isotope Treatment in DMEM and Neurobasal Media. Data presented as mean + SEM (N = 5, two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) * = p < 0.05). Data represents the simultaneous comparison of HT22 cell viability when treated with lithium isotopes in DMEM and neurobasal media. A significant increase in viability was found in control cells treated with neurobasal media when compared with control DMEM. No significant toxicity was found on HT22 cells when treated with lithium isotopes from 8 mM to 32 mM in either DMEM or neurobasal media.

The effect of natural lithium salts on cell viability was previously studied in other cultured cell lines, with reported results quite variable and which include a combination of direct toxicity and/or reduced cell growth. For example, in the human oligodendrocyte-derived MO3.13 cell line, lithium causes no significant toxicity below 100 mM [35]. In contrast, lithium concentrations as low as 2 mM inhibit the growth of the human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells [36]. Previously, it had been reported that in HT22 cells, lithium can in fact be protective against acrolein-induced toxicity at concentrations of 3–10 mM [37]. Our results demonstrate that lithium alone does not show any toxic effect in HT22 cells at concentrations up to 32 mM. We thus believe that HT22 cells can be safely used in future studies with lithium natural salt and lithium isotopes in this concentration range.

3.3. GSK-3-β (S9) phosphorylation as a result of Li isotope treatment

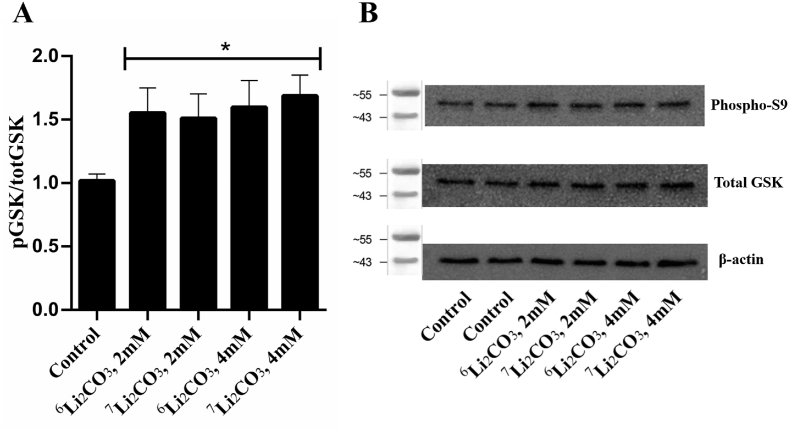

The significant ∼1.5-fold increase in phosphorylation of the S9 site between control and all the lithium-treated groups, as depicted in Fig. 3A, was as expected [[38], [39], [40]]. However, we found no significant difference between any of the lithium-treated groups. Thus, we conclude that there is no difference between lithium isotopes 6Li and 7Li as they both increase the phosphorylation of GSK-3-β at the S9 site by comparable amounts (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

GSK-3-β (S9) Phosphorylation as a Result of Li Isotope Treatment. HT22 cells were treated with 2 or 4 mM Li2CO3 containing each isotope for 24 h. After treatment, cell lysates were processed as described and evaluated via Western blot for phosphorylation of GSK-3-β at S9. All signals were normalized by β-actin, total GSK-3-β was not affected by lithium treatment. Welch’s unequal variance t-tests were calculated between all treatment groups. No significant differences in phosphorylation of S9 between the lithium isotopes were found, however a significant increase (* = p < 0.05) in phosphorylation was found in all lithium-treated groups when each were compared to the control groups. Data in panel A represents eight 6-well plates (N = 8) presented as mean + SEM. Representative blots for β-actin, phospho-S9 and total GSK-3-β are shown in panel B. Repeats are shown in Appendix A.

The S9 site on GSK-3-β is phosphorylated by upstream kinase cascades that include lithium-affected kinases such as AKT (PKB) [41], PKA [42], PI3-K [43], and PKC [44]. The literature indicates that the binding sites of each enzyme are variable enough to determine whether Li+ can effectively compete with Mg2+, which explains how lithium can directly inhibit some enzymes but not others [45]. The lack of isotopic effect on the phosphorylation of the S9 site could indicate that there is no isotopic effect at play, or it could indicate that this chosen site is regulated by too many kinases for a unidirectional isotopic effect across all upstream kinases to be detected. Phosphorylation of the S9 site is well known to result in inhibited GSK-3-β kinase activity, but this is not the only phosphorylation site that controls the activity of GSK-3-β, and the overall activity of GSK-3-β may not be entirely assigned to the phosphorylation of the S9 site [46]. For example, phosphorylation of tyrosine 216 (Y216) can increase GSK-3-β activation [46]. In fact, some research even suggests that the overall activity level of GSK-3-β in vivo is more accurately correlated with phosphorylation of Y216 than S9 [46]. Since the total activity of GSK-3-β is controlled by more than just the phosphorylation of S9, the characterization of the Y216 site would be a natural next step to help elucidate the activity level of GSK-3-β in response to lithium isotopes. Future research on the Y216 site phosphorylation, when combined with the data presented here, could help answer whether the total activity of GSK-3-β is altered differentially by lithium isotopes in the HT22 neuronal cell.

4. Conclusions

We tested the effect of lithium isotopes (6Li and 7Li) on HT22 cell viability, GSK-3-β phosphorylation, and GSK-3-β kinase activity. We found that neither lithium isotope is toxic to HT22 cells up to 32 mM and both lithium isotopes increase the GSK-3-β phosphorylation at the S9 site at 4 mM and 8 mM but with no significant difference between isotopes. We also found no significant difference between the effects of lithium isotopes on GSK-3-β kinase activity within lithium concentrations used from 0.25 mM to 16 mM. While the results of this study on HT-22 cells indicate no significant difference between the two lithium isotopes, alternatives to the rapidly-growing and resilient HT22 cell model, such as primary rodent neurons or iPSC neurons, could exhibit greater sensitivity to any possible lithium isotope effects and may be a promising research direction to pursue.

CRedIT statement of contributions

James D. Livingstone: Methodology, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – editing. Michel J.P. Gingras: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, visualization, writing – editing. Zoya Leonenko: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, writing – editing. Michael A. Beazely: Conceptualization, supervision, resources, visualization, writing – editing. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. John Mielke for his contribution to discussions and Dr. Morgan Robinson for his insight and technical support regarding this project.

Funding sources

Natural Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) grants to ZL and MB, New Frontier in Research Fund (NFRF) grant to ZL and MG, Transformative Quantum Technologies (TQT) seed grant (University of Waterloo) to MG and ZL.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing or conflicting interests that could have influenced the work presented in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrep.2023.101461.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Turekian K.K., Wedepohl K.H. Distribution of the elements in some major units of the earth's crust. Bull. Geol. Soc. Am. 1961;72:175–192. doi: 10.1130/0016-7606. (1961)72[175:DOTEIS]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schrauzer G.N. Lithium: occurrence, dietary intakes, nutritional essentiality. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2002;21:14–21. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2002.10719188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pickett E.E., O’Dell B.L. Evidence for dietary essentiality of lithium in the rat. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 1992;34:299–319. doi: 10.1007/BF02783685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szklarska D., Rzymski P. Is lithium a micronutrient? From biological activity and epidemiological observation to food fortification. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2019;189:18–27. doi: 10.1007/s12011-018-1455-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Svec H.J., Anderson A.R., Jr. The absolute abundance of the lithium isotopes in natural sources. Geochem. Cosmochim. Acta. 1965;29:633–641. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(65)90060-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexander G.J., Lieberman K.W., Stokes P. Differential lethality of lithium isotopes in mice. Biol. Psychiatr. 1980;15:469–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parthasarathy R., Eisenberg F. Lack of differential lethality of lithium isotopes in mice. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1984;435:463–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1984.tb13853.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lieberman K.W., Alexander G.J., Stokes P. Dissimilar effects of lithium isotopes on motility in rats. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 1979;10:933–935. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(79)90070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sechzer J.A., Lieberman K.W., Alexander G.J., Weidman D., Stokes P.E. Aberrant parenting and delayed offspring development in rats exposed to lithium. Biol. Psychiatr. 1986;21:1258–1266. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(86)90308-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherman W.R., Munsell L.Y., Wong Y.H. Differential uptake of lithium isotopes by rat cerebral cortex and its effect on inositol phosphate metabolism. J. Neurochem. 1984;42:880–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb02765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richelson E. Lithium ion entry through the sodium channel of cultured mouse neuroblastoma cells: a biochemical study. Science. 1977;196:1001–1002. doi: 10.1126/science.860126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jakobsson E., Argüello-Miranda O., Chiu S.W., Fazal Z., Kruczek J., Nunez-Corrales S., Pandit S., Pritchet L. Towards a unified understanding of lithium action in basic biology and its significance for applied biology. J. Membr. Biol. 2017;250:587–604. doi: 10.1007/s00232-017-9998-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holm N.G. The significance of Mg in prebiotic geochemistry. Geobiology. 2012;10:269–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2012.00323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haimovich A., Goldbourt A. How does the mood stabilizer lithium bind ATP, the energy currency of the cell: insights from solid-state NMR. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1864;2020:1. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2019.129456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dudev T., Grauffel C., Lim C. How native and alien metal cations bind ATP: implications for lithium as a therapeutic agent. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–10. doi: 10.1038/srep42377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birch N.J. Lithium and magnesium-dependent enzymes. Lancet. 1974;304:965–966. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(74)91187-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Machado-Vieira R., Manji H.K., Zarate C.A. The role of lithium in the treatment of bipolar disorder: convergent evidence for neurotrophic effects as a unifying hypothesis. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11:92–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00714.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sutherland C. What are the bona fide GSK3 substrates? Int. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2011 doi: 10.4061/2011/505607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hooper C., Killick R., Lovestone S. The GSK3 hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurochem. 2008;104:1433–1439. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacAulay K., Woodgett J.R. Targeting glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) in the treatment of Type 2 diabetes. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2008;12:1265–1274. doi: 10.1517/14728222.12.10.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jope R., Roh M.-S. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) in psychiatric diseases and therapeutic interventions. Curr. Drug Targets. 2012;7:1421–1434. doi: 10.2174/1389450110607011421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Domoto T., Pyko I.V., Furuta T., Miyashita K., Uehara M., Shimasaki T., Nakada M., Minamoto T. Glycogen synthase kinase-3β is a pivotal mediator of cancer invasion and resistance to therapy. Cancer Sci. 2016;107:1363–1372. doi: 10.1111/cas.13028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jope R.S. Lithium and GSK-3: one inhibitor, two inhibitory actions, multiple outcomes. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2003;24:441–443. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00206-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fisher M.P.A. Quantum cognition: the possibility of processing with nuclear spins in the brain. Ann. Phys. 2015;362:593–602. doi: 10.1016/j.aop.2015.08.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weingarten C.P., Doraiswamy P.M., Fisher M.P.A. A new spin on neural processing: quantum cognition. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016;10:541. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zadeh-Haghighi H., Simon C. Entangled radicals may explain lithium effects on hyperactivity. Sci. Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-91388-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riss T.L., Moravec R.A., Niles A.L., Duellman S., Benink H.A., Worzella T.J., Minor L. Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; 2004. Cell Viability Assays. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zegzouti H., Zdanovskaia M., Hsiao K., Goueli S.A. ADP-Glo: a bioluminescent and homogeneous adp monitoring assay for Kinases. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2009;7:560–572. doi: 10.1089/adt.2009.0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vidugiriene J., Zegzouti H., Vidugiris G., Goueli S.A. ADP-GloTM kinase assay application notes SER-THR KINASE SERIES: GSK3β GSK3β kinase assay ADP-GloTM kinase assay. 1995. www.promega.com/tbs/tm313/tm313.html

- 30.Mahmood T., Yang P.C. Western blot: technique, theory, and trouble shooting. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2012;4:429–434. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.100998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryves W.J., Harwood A.J. Lithium inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3 by competition for magnesium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;280:720–725. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scarpa A., Brinley F.J. Federation Proceedings; 1981. In Situ Measurements of Free Cytosolic Magnesium Ions. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Romani A., Scarpa A. Regulation of cell magnesium. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1992;298:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90086-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ryves W.J., Harwood A.J. Lithium inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3 by competition for magnesium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;280:720–725. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Del Grosso A., Antonini S., Angella L., Tonazzini I., Signore G., Cecchini M. Lithium improves cell viability in psychosine-treated MO3.13 human oligodendrocyte cell line via autophagy activation. J. Neurosci. Res. 2016;94:1246–1260. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allagui M.S., Vincent C., El feki A., Gaubin Y., Croute F. Lithium toxicity and expression of stress-related genes or proteins in A549 cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Res. 2007;1773:1107–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang Y., Qin J., Chen M., Chao X., Chen Z., Ramassamy C., Pi R., Jin M. Lithium prevents acrolein-induced neurotoxicity in HT22 mouse hippocampal Cells. Neurochem. Res. 2014;39:677–684. doi: 10.1007/s11064-014-1252-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monaco S.A., Ferguson B.R., Gao W.J. Lithium inhibits GSK3β and augments GluN2A receptor expression in the prefrontal cortex. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018;12:16. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Sousa R.T., Zanetti M.V., Talib L.L., Serpa M.H., Chaim T.M., Carvalho A.F., Brunoni A.R., Busatto G.F., Gattaz W.F., Machado-Vieira R. Lithium increases platelet serine-9 phosphorylated GSK-3β levels in drug-free bipolar disorder during depressive episodes. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015;62:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hallcher L.M., Sherman W.R. The effects of lithium ion and other agents on the activity of myo-inositol-1-phosphatase from bovine brain. J. Biol. Chem. 1980;255:10896–10901. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9258(19)70391-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cross D.A.E., Alessi D.R., Cohen P., Andjelkovich M., Hemmings B.A. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature. 1995;378:785–789. doi: 10.1038/378785a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fang X., Yu S.X., Lu Y., Bast R.C., Woodgett J.R., Mills G.B. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000. Phosphorylation and inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 by protein kinase A; pp. 11960–11965. 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou X., Wang H., Burg M.B., Ferraris J.D. Inhibitory phosphorylation of GSK-3β by AKT, PKA, and PI3K contributes to high NaCl-induced activation of the transcription factor NFAT5 (TonEBP/OREBP) Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2013;304:F908–F917. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00591.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goode N., Hughes K., Woodgett J.R., Parker P.J. Differential regulation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β by protein kinase C isotypes. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:16878–16882. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9258(18)41866-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dudev T., Lim C. Competition between Li+ and Mg2+ in metalloproteins. Implications for lithium therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:9506–9515. doi: 10.1021/ja201985s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krishnankutty A., Kimura T., Saito T., Aoyagi K., Asada A., Takahashi S.I., Ando K., Ohara-Imaizumi M., Ishiguro K., Hisanaga S.I. In vivo regulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β activity in neurons and brains. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:8602. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09239-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.