Abstract

Brandy, produced by the distillation of wine, is highly consumed in Cameroon, most of which is imported, whereas this region harnesses a vast diversity of fruits, which could be exploited in producing wines and spirits. These fruits have interesting health virtues and are prone to rapid postharvest losses. This study is aimed at producing brandy from a combination of pineapple (Ananas comosus), watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) and guava (Psidium guajava), with an objective to optimize the ratio of fruit pulps and fermentation time in order to produce wine, then brandy of acceptable taste and flavor. A D-optimal 3-component, 1-factor experimental design was used to obtain the best wine formulation to be distilled. The factors retained were: the volumes of Pineapple (A), watermelon (B) and guava (C) and the fermentation time (D) was considered as a process factor. Based on the experimental design using Design Expert 11 software, 24 wine samples were formulated. After statistical analyses, the pH, alcohol content and viscosity were considered for mathematical modeling due to their significant impacts during fermentation (pH and viscosity) and distillation (alcohol content).

Optimization for wine production gave a fruit formulation of 69, 19 and 12% of pineapple, watermelon and guava respectively, with a fermentation time of 11 days. Distillation of this wine gave an ethanol output of 72%, from which two distinct Brandy was obtained: one (E1) in which dilution was done with clarified wine, and the second (E2) with distilled water and a roasted bark of Cupressus sempervirens (cypress) added to it. After six weeks of aging at ambient temperature, physicochemical characteristics showed a vitamin C content of 100 and 80 mg/L, polyphenols content of 22.77 and 42.77 mqGAE/100 g, and a titratable acidity of 1.42 and 0.45 meq.g of tartaric acid respectively for E1 and E2. After sensory analysis, brandy sample E1 was preferred.

Keywords: Brandy, Wine, Fermentation, Pineapple, Watermelon, Guava, Distillation, Spirits

1. Introduction

Agriculture plays a major role in the Cameroon economy [1]. The fruit and vegetable sector contribute greatly through exportation of its raw and transformed products. Epidemiological studies showed a positive correlation between a fruit and vegetable rich diet and reduced occurrence of degenerative diseases comprising cardiovascular diseases, certain types of cancer, aging and others [[2], [3], [4], [5]].

Pineapple is one of the most cultivated fruits to the tune of about 352,000 tons per annum [6], with about 52 000 tons being exported each year and a significant percentage of postharvest losses being recorded. Watermelon, whose annual production has risen to more than 83 000 tons, cannot be readily exported because of its highly perishable nature, with over 40% of the production lost. Guava, whose production in Cameroon is estimated at 6000 tons per annum [6], though not produced on a large commercial scale, is also a victim of postharvest losses.

Transformation of these fruits is being carried out as a means to reduce postharvest losses. Among the transformed products are dried fruits and fruit juices that are either intended for sale in the national territory or exported.

With the enormous importation rates of wines and spirits into Cameroon [7], it would be convenient if these fruits could be exploited locally for their production. In the large group of spirits, “Brandy”, an alcoholic beverage obtained from distilling various fermented products such as wines [8,9], can be distinguished. The consumption of brandy has been linked with therapeutic properties, boosting its prominence among alcoholic drinks [10]. Brandy has been appreciated for its elegant aroma and taste. These features are based on several components whose role in the development of brandy flavor is highly related to the type/variety of fruit, among other factors. Though much work has been documented for grape brandy, very few efforts have been made towards utilizing fruits other than grapes [11]. Indeed, if wines can be produced from the fruits mentioned above, further use in spirit production can be envisaged. In addition, these fruits, especially guava, have properties similar to that of grapes [12], the principal fruit used in brandy production.

In order to encourage local transformation and hence reduce postharvest losses of local fruits, this study aims at exploiting the technological potential of Ananas comosus (pineapple), Citrullus lanatus (watermelon), and Psidium guajava (guava) in the production of “brandy”. The principal objective being to optimize the ratio of fruit pulps and fermentation time in order to produce wine, then brandy of acceptable taste and flavor. Such exploitation could limit the importation of similar foreign products and hence serves as a booster to the local economy.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Raw materials

The main biological materials used were pineapples, watermelon, and guava that were bought in the Ngaoundere main market. The bark of Cupressus sempervirens was also collected specifically in the Bini-Dang locality of Ngaoundere.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Production process of wine and fruit brandy samples

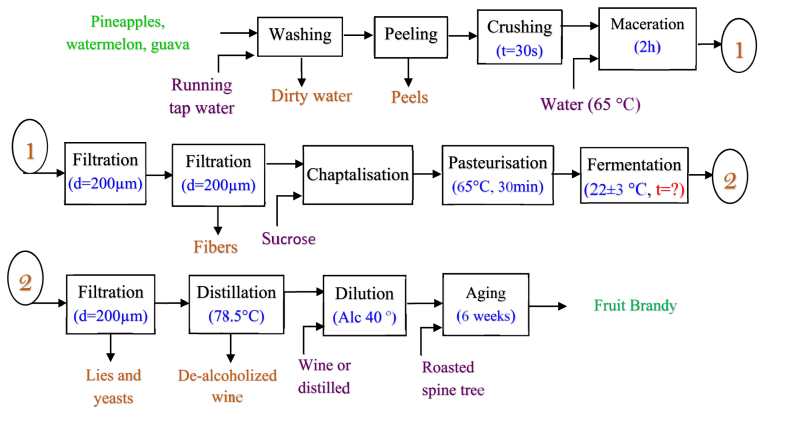

The fruit brandy was produced in two stages: formulation of the best wine sample from a combination of the different fruits then distillation and re-dilution to obtain the fruit brandy. Fig. 1 presents the process diagram elaborated for the production of the fruit brandy.

Fig. 1.

Process diagram elaborated for the production of Fruit Brandy.

The fruits were sorted, and whole matured ripe fruits were used. They were washed with running tap water and then peeled. For the watermelon, the seeds were removed. The fruits were then crushed in a blender (marked SINCO) to reduce the particle size and facilitate extraction. A given volume of water at 65 °C was added to fixed quantities of each fruit mixture per the experimental design. The diluted mixture was agitated manually every 30 min for 2 h to ensure maximum diffusion of soluble fruit content in the solvent fraction. The solution was then passed through a 200 μm sieve to retain fibers in the potential must. Chaptalization was done by adding sucrose to rectify (increase) the total soluble solids (Brix) in the musts. The musts were then pasteurized at 65 °C for 30 min.

Inoculation was carried out by adding 5 g/L of Saccharomyces cerevisiae into each must sample and allow for fermentation at ambient temperature (22 ± 3 °C) for 3–12 days per the experimental design. At the end of the fermentation of specific samples, filtration (d = 200 μm) was carried out to separate the young wine from lies and yeasts. The wine samples were characterized and process parameters were optimized per the degree of significance, to obtain the best wine sample for distillation.

Distillation was carried out to concentrate aroma and separate alcohol from water; water has a boiling point of 100 °C and ethanol of 78.5 °C. A simple distillation dispositive was set up and ethanol was separated from the fermented must. After that, dilution of the distillate was done either by adding non-distilled clarified wine or distilled water, considering the desired alcoholic content of 40°. In the sample diluted with distilled water, a roasted (200 °C for 5 min) bark of Cupressus sempervirens (cypress) was introduced into the young brandy. Maturation or aging was carried out for six weeks at 20 °C.

2.2.2. Physico-chemical analyses on wine and fruit brandy samples

The dry matter and water content of the different fruit samples were determined by the AOAC 925.10 [13] method.

2.2.2.1. Determination of vitamin C

Vitamin C was determined by the iodine titration method as described by Helmenstine [14]. Iodine, in the form of triiodide, oxidizes vitamin C (ascorbic acid) to form dehydroascorbic acid.

| C6H8O6 + I3− + H2O → C6H6O6 + 3I− + 2H+ |

When all vitamin C in the solution has been oxidized, excess iodine and triiodide will react with starch to form a blue-black complex, marking the endpoint of the titration.

A 1% starch indicator solution was prepared by adding 0.5 g of soluble starch in 50 mL of distilled water at 90 °C. The solution was well mixed to enable the complete dissolution of the starch.

Iodine solution was prepared by dissolving 5 g of potassium iodide (KI) and 0.268 g of potassium iodate (KIO3) in 200 mL of distilled water. After that, 30 mL of 3 M sulfuric acid was added. It was then diluted with distilled water to a final volume of 500 mL.

Vitamin C standard solution was prepared by dissolving 0.25 g of Vitamin C in 100 mL of distilled water. After complete dissolution, dilution was completed to 250 mL with distilled water.

The vitamin C content of the standard solution was determined using 25 mL added in a clean 250 mL conical flask and about 10 drops of the 1% starch solution added to it. The resulting solution was titrated with iodine until the endpoint and the mean volume of iodine used was noted. A similar procedure was carried out for the wine samples.

The vitamin C content was calculated as the ratio of the volume of iodine used for the standard solution compared to wine samples.

2.2.2.2. Titratable acidity

The total titratable acidity was determined by the AFNOR [15] method using 0.1 N NaOH in the presence of phenolphthalein.

In a conical flask, 5 mL of each sample was introduced, and a few drops of phenolphthalein indicator was added. The sample was titrated with a 0.1 N NaOH solution until a persistent pink coloration was obtained. The volume of NaOH used, VNaOH, was noted in mL.

The total titratable acidity was calculated using Eq. (1):

| (1) |

TA = Total titratable acidity, N = concentration of NaOH, V = volume of NaOH used, T = volume sample.

2.2.2.3. Polyphenol content

The phenolic compounds were extracted using 70% ethanol, then determined by the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent [16] method, specifically adapted for wine as described by Lamuela‐Raventós [17].

Wine samples were previously diluted 1:5 with distilled water and placed in a volumetric flask. To prepare a 5000 mg/L mother solution, 50 mg of standard gallic acid was added in a 10 mL volumetric flask and dissolved in 2 mL of methanol, and the volume was completed with distilled water. From the mother solution, 1 mL was added to a 50 mL volumetric flask, and the volume was completed with distilled water. A standard curve was prepared with 1, 2, 3, 8, 12, and 24 mg/L and distilled water was used as blank. The calibration standard curve was obtained by adding 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 72 μL of 100 ppm gallic acid to a final volume of 208 μL with distilled water. For the wine samples, 24 μL were mixed with 184 μL of distilled water in a thermos-microtiter 96‐well plate (TM Roskilde), adding 12 μL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and 30 μL of sodium carbonate (200 g/L). The mixtures were incubated for 1 h at ambient temperature in the dark. After the reaction period, 50 μL of distilled water was added, and absorbance was read at 765 nm.

The results were expressed as milligram equivalent of gallic acid in 100 g of dry product from Eq. (2) obtained from the gallic acid standard curve.

| Optical density = aQ + b | (2) |

Q: the amount of phenolic compounds; a, b constants to be determined.

2.2.2.4. Reducing sugars

The method described by Alejandro et al. [18] for the determination of reducing sugar content was modified and used. In a 100 mL flask, 1 g of DNS was weighed and dissolved in 20 mL of 10% NaOH. Then 30 g of Na and K double tartrate were weighed and dissolved in 50 mL of distilled water. The two solutions were mixed and made up to 100 mL with distilled water.

A standard solution, S1, of maltose with a concentration of 2 mg/mL was prepared by mixing 0.2 g of maltose in 100 mL of distilled water. The standard solutions S2, S3, S4, and S5, of concentrations 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 1.5 mg/mL, were prepared by diluting solution S1. Using standard solutions S1, S2, S3, S4, and S5 of maltose, the calibration range was prepared, and the assay of the samples was carried out as indicated. The amount of reducing sugars in each test portion was determined by referring to the regression equation calibration curve as in Eq. (2).

2.2.2.5. Color

The Standard Reference Method (SRM) is a system created by the American Society for Brewing Chemists (ASBC) to specify the color of beer [19]. The SRM is determined by measuring the absorbance of beer at 430 nm. A similar method is available in EBC (European Brewery Convention). The color was calculated thus:

ASBC: color = absorbance at 430 nm × 12.7 × d

EBC: absorbance at 430 nm × 25 × d

With d = dilution factor.

2.2.2.6. Total soluble solids (Brix)

Total soluble solid was measured using an optical refractometer (HI-96801 Refractometer; Hanna Instruments). After calibrating with distilled water, a few drops of the sample were poured onto the prism in the center of the sample stage, then the READ key was pressed, and the result was given on the display board.

2.2.2.7. Alcoholic strength

The alcoholic strength or Gay-Lussac degree is the proportion of alcohol, precisely ethanol, contained in an alcoholic beverage. It was measured using an optical alcoholmeter (Dp1402 Automatic Wine Alcohol Meter Refractometer; Sino tester), which worked after being calibrated by displaying the value of the alcoholic degree on the scale present at the level of the lens.

2.2.2.8. Density

The density measurement is based on the determination of the mass of a tested sample placed in a pycnometer of known volume at a given temperature. A 25 mL pycnometer was filled to the brim with a well-homogenized sample, and a cover was placed to adjust the volume. With the mass (M0) of the empty pycnometer and cover known, the mass (M1) of the filled pycnometer was measured, and the density of each sample was calculated using Eq. (3):

| (3) |

With M0: mass of empty pycnometer (g), M1: mass of pycnometer filled with sample (g), V: volume of pycnometer (mL).

2.2.2.9. Viscosity

Viscosity was measured by determining the tangential force required to move particles through the sample at a specific deformation rate. The viscometer (Rotatif NDJ-5S) acted by rotating a disc (rod) immersed in the sample to be analyzed and measured its resistance at a given velocity. Rod design and measurement principles are governed by ISO 2555 and ISO 1652. All rods were made of AISI 316 stainless steel.

After calibrating the viscometer, a beaker containing the sample was placed below the rod immerse it partially. The velocity was adjusted (60 RPM), and the test started. The viscosity was read directly on the LCD in milliPascal seconds (mPa.s) when there was no longer any variation.

2.2.2.10. Distillation yield [20]

The distillation yield considers the Gray-Lussac degree alcoholic strength of the starting wine and that of the distillate. It was calculated using Eq. (4).

| (4) |

M = mass of ethanol after the distillation

M0 = masse of ethanol in the wine sample before distillation

Where

and

Vd: volume of distilate; Vm: volume of wine; TAV alcoholic strength in volume; ρ ethanol = 0.7890 kg/L.

2.2.3. Modeling and optimization

A D-optimal 3-component, 1-factor experimental design was used to obtain the best wine formulation to be distilled. The factors retained were: the volumes of Pineapple (A), watermelon (B), and guava (C) and the fermentation time (D) was taken as a process factor. Indeed, time was a major factor for the fermentation, allowing a better yield over a given interval. The different fruits’ volumes would allow for obtaining the best constituents of the must.

The dependent variables (responses) chosen were: pH, total soluble solids, vitamin C, titratable acidity, polyphenol content, reducing sugars, color, alcoholic degree, density and viscosity.

The Design Expert 11 software was used to generate the experimental matrix with coded values as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The Experimental Matrix with coded values as generated by Design Expert 11.

| Trials | Pineapple | Watermelon | Guava | Fermentation time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.500015 | 0.499985 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | −1 |

| 3 | 0.174622 | 0.677197 | 0.148181 | −0.5 |

| 4 | 0.491177 | 0 | 0.508823 | 1 |

| 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | −1 |

| 9 | 0.498809 | 0 | 0.501191 | 0 |

| 10 | 0.497486 | 0.502514 | 0 | −1 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 1 | −1 |

| 12 | 0.010813 | 0.488126 | 0.501061 | 0 |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 14 | 0 | 0.505447 | 0.494553 | −1 |

| 15 | 0.500015 | 0.499985 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | 0.498212 | 0.501788 | 0 | 1 |

| 17 | 0.498809 | 0 | 0.501191 | 0 |

| 18 | 0.665269 | 0.168483 | 0.166248 | 0.5 |

| 19 | 0.0106 | 0.497633 | 0.491766 | 1 |

| 20 | 0.16102 | 0.671805 | 0.167175 | 0.5 |

| 21 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 22 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 23 | 0.497497 | 0.0128354 | 0.489667 | −1 |

| 24 | 0.010813 | 0.488126 | 0.501061 | 0 |

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine each factor's influence and the degree of significance of each of these effects. It then examined the statistical significance of each effect by comparing the squared mean against an estimate of the experimental error. The significance of each factor was determined by Fisher's test representing the significance of each controlled variable on the examined model. The regression equations were also subjected to Fisher's test to determine the regression coefficient R2.

In addition, the calculations were performed with Design Expert 11 software. The accepted confidence level was (1 − α) ≥ 0.9.

2.2.4. Sensory analysis

In order to choose the best brandy sample, a hedonic test was carried out by panelists consisting essentially of brandy consumers. All participants gave their consent and their responses were personal. The analysis was focused on factors such as: color, flavor, alcoholic degree, taste and general acceptability. The degrees of appreciation ranged from very unpleasant for a score of 1 to extremely pleasant for a score of 9. The data obtained at the end of this analysis were analyzed using XLSTAT software.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characteristics of raw materials

3.1.1. Physico-chemical characteristics of the fruits

Fruit composition is decisive for its use as it defines the fruit's intrinsic properties and technological potentials. Table 2 presents the physico-chemical characteristics of pineapple, watermelon, and guava.

Table 2.

Physico-Chemical Characteristics of the fruits.

| Characteristics | Pineapple | Watermelon | Guava |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Soluble Solids (Brix) | 12.8 ± 0.0 | 6.5 ± 0.3 | 12.0 ± 0.1 |

| Reducing Sugar (mg/mL) | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 6.4 ± 0.6 | 8.4 ± 0.6 |

| Total Polyphenols (mqGAE/100 g) | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 125. ±2 |

| Vitamin C (mg/L) | 25 ± 5 | 8.3 ± 0.0 | 110.0 ± 0.8 |

| Titratable acidity (meq.g citric acid/100 g) | 13 ± 3 | 9.0 ± 0.1 | 55 ± 13 |

| Dry matter (g/100 g) | 10.1 ± 0.3 | 11.0 ± 0.7 | 19.2 ± 0.5 |

The total soluble solids of pineapple (Cayenne variety) was 12.8 Brix, which is similar to that obtained by Azonkpini et al. [21]. This value is similar to that of guava and twice that of watermelon. However, guava has more reducing sugars than the other two fruits containing 8.4 ± 0.6 mg/mL. Indeed, the total soluble solids and the reducing sugars of these fruits are of paramount importance because these sugars will be converted to alcohol by yeasts during fermentation [22].

Among the three fruits, guava has the greatest vitamin C content (110.0 ± 0.8 mg/L) though lower than the 228 mg/L obtained by Tensaout and Gaoua [23]. Vitamin C is an antioxidant that plays an important role in fermentation. Indeed, it would prevent the oxidation of other molecules present in the medium during fermentation and reduce yeast stress caused by dehydration [24]. Just like vitamin C, polyphenols are also antioxidants. They are found in large quantities in guava (125 mqGAE/100 g) than in watermelon and pineapple. They are responsible for the color of the fruits and also the color of the product resulting from fermentation [25].

During fermentation, organic acids contribute to product quality [26]. The titratable acidity content of pineapple is 13.13 meq.g of citric acid, lower than the 55 meq.g of citric acid of guava, whose value is within the range shown in the works of INPI [27].

The dry matter of pineapple and watermelon were relatively low (10.07 and 10.95 g/100 g, respectively) similar to the Vulgaris species [28]; that of guava is higher, 19.15 g/100 g, a value similar to that of Soatsara [29]. Dry matter influences fermentation because it determines a plant's ability to ferment. The lower the dry matter content, the lower the pH will have to drop to inhibit bacteria [30]), hence the need for blending to provide an appropriate environment for fermentation.

3.1.2. Physico-chemical characteristics of Cupressus sempervirens tree bark

The physico-chemical analysis carried out included reducing sugar content, total polyphenols, dry matter content, and water content. The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Cupressus sempervirens tree bark.

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Reducing sugars (mg/mL) | 7.5 ± 0.0 |

| Total Polyphenols (mgGAE/100 g) | 9 ± 1 |

| Dry Matter (g/100 g) | 88.2 ± 0.2 |

| Water content (%) | 11.8 ± 0.2 |

The polyphenol content is quite high in the essence of cypress. The relatively high quantities of these antioxidants in this bark are important to health and would enrich the antioxidant level of any product it could be added to Ref. [25]. The reducing sugar content was 7.5 mg/mL. These sugars are important because they are essential for the proper functioning of the body and would soften the taste of the product containing this essence [31]. Cypress contains an essential oil rich in alpha-pinene, which plays a stimulating role for the mucin glands.

3.2. Modeling of factors impacting the physicochemical characteristics of wine samples

Table 4 presents the mean results of the distilled wine's physicochemical analysis. The parameters considered were pH, total soluble solids, TSS (Brix), color (EBC), vitamin C (mg/L), titratable acidity (meq.g of tartaric acid), polyphenols (mqGAE/100 g), alcoholic degree, reducing sugars (mg/mL), density (g/mL) and viscosity (mPa.s). The pH, alcohol content and viscosity were considered for mathematical modeling due to their variation during fermentation (pH and viscosity) and distillation (alcoholic content). The different factors studied: A = Pineapple; B= Watermelon; C = Guava; D = fermentation time.

Table 4.

Physico-chemical characteristics of wines to be distilled.

| Wine samples | pH | TSS | Vit. C | TA | Polyphenols | Sugars | Color | Alcohol | Density | Viscosity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.42 | 14.63 | 15.68 | 0.34 | 44.25 | 13.87 | 66.17 | 6.00 | 1.03 | 6.16 |

| 2 | 3.50 | 12.26 | 19.60 | 0.50 | 38.17 | 11.64 | 10.15 | 7.13 | 1.01 | 5.50 |

| 3 | 3.34 | 12.3 | 11.76 | 0.46 | 42.37 | 12.64 | 12.12 | 6.95 | 1.01 | 5.83 |

| 4 | 3.32 | 15.13 | 90.19 | 0.46 | 58.17 | 15.27 | 93.80 | 5.16 | 1.02 | 7.33 |

| 5 | 3.32 | 14.23 | 58.82 | 0.45 | 33.49 | 12.72 | 15.15 | 5.82 | 1.02 | 6.99 |

| 6 | 3.45 | 16.5 | 58.82 | 0.49 | 35.94 | 13.34 | 6.77 | 4.45 | 1.03 | 6.66 |

| 7 | 3.47 | 8.56 | 19.60 | 0.43 | 27.95 | 3.66 | 28.65 | 9.20 | 0.99 | 5.50 |

| 8 | 3.31 | 9.46 | 11.76 | 0.50 | 31.25 | 2.85 | 48.82 | 9.26 | 0.98 | 6.66 |

| 9 | 3.39 | 7.63 | 9.80 | 0.47 | 27.86 | 0.63 | 21.40 | 9.62 | 0.98 | 7.33 |

| 10 | 3.30 | 13.10 | 56.86 | 0.59 | 53.89 | 8.91 | 104.70 | 6.53 | 1.00 | 11.50 |

| 11 | 3.44 | 11.5 | 47.05 | 0.61 | 26.12 | 6.56 | 61.75 | 8.55 | 0.99 | 6.00 |

| 12 | 3.31 | 9.60 | 39.21 | 0.52 | 29.69 | 4.20 | 93.55 | 8.91 | 0.98 | 8.00 |

| 13 | 3.28 | 8.06 | 11.76 | 0.48 | 29.07 | 0.96 | 65.52 | 9.38 | 0.97 | 5.50 |

| 14 | 3.39 | 9.03 | 47.05 | 0.55 | 22.55 | 3.69 | 54.02 | 9.26 | 0.99 | 8.50 |

| 15 | 3.25 | 8.00 | 11.76 | 0.56 | 33.98 | 0.73 | 10.25 | 9.50 | 0.97 | 7.16 |

| 16 | 3.29 | 9.53 | 47.05 | 0.52 | 25.01 | 5.05 | 89.90 | 8.73 | 0.99 | 6.50 |

| 17 | 3.35 | 7.73 | 27.45 | 0.54 | 30.59 | 0.72 | 20.30 | 9.32 | 0.97 | 6.33 |

| 18 | 3.38 | 6.90 | 23.52 | 0.47 | 20.05 | 0.00 | 61.55 | 8.85 | 0.97 | 6.00 |

| 19 | 3.38 | 7.43 | 66.66 | 0.62 | 19.07 | 0.35 | 115.67 | 9.50 | 0.98 | 9.16 |

| 20 | 3.36 | 7.50 | 11.76 | 0.46 | 24.11 | 0.43 | 12.37 | 9.68 | 0.97 | 5.50 |

| 21 | 3.28 | 7.70 | 78.43 | 0.62 | 48.40 | 4.47 | 135.85 | 7.42 | 0.99 | 13.82 |

| 22 | 3.25 | 7.66 | 15.68 | 0.52 | 27.06 | 0.49 | 19.725 | 9.50 | 0.97 | 6.00 |

| 23 | 3.27 | 8.13 | 54.90 | 0.56 | 26.97 | 1.60 | 120.37 | 9.62 | 0.97 | 7.50 |

| 24 | 3.22 | 7.33 | 19.60 | 0.48 | 31.16 | 0.18 | 16.57 | 8.97 | 0.98 | 5.166 |

3.2.1. Impact of factors on pH during fermentation

The pH is a determining factor for proper fermentation evolution as it inhibits mesophilic bacteria's proliferation at values lesser than 4.5 [[32], [33], [34]].

The mathematical model of the evolution of this response is presented in Eq. (5):

| (5) |

A = Pineapple, B=Watermelon, C = Guava, D = Fermentation time.

Equation (5): Mathematical model for the evolution of pH during wine fermentation.

This model has a coefficient of determination, R2 of 0.9156 and an adjusted R2 of 0.8059. The two being close shows that the model is valid for pH follow-up.

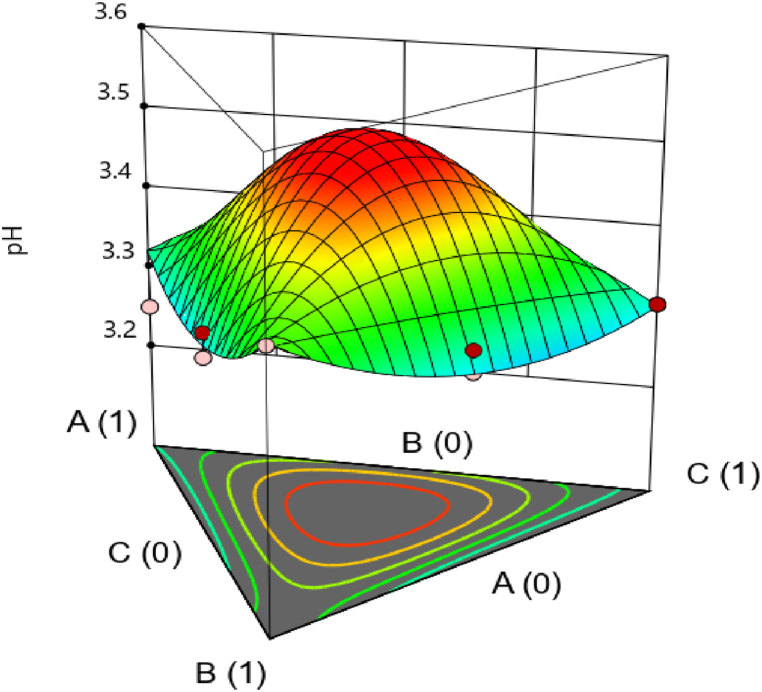

Before fermentation, the pH increases as the amount of pineapple increases, but watermelon increases the pH very little, unlike pineapple, which contains more sugar (Fig. 2). The same is true for guava, which helps to increase the pH due to its high dry matter content. This behavior is justified by the amount of sugar which minimizes the amount of acids. The interaction of the three fruits (Fig. 3) increases the pH. The more the fruit is advanced in its maturation stage, the higher its pH; on the other hand, the acidity decreases [35]. Since organic acids are synthesized, a drop in pH is observed as fermentation time is prolonged (Fig. 4) [26]. Indeed, during alcoholic fermentation, the pH of the must is in perpetual change as the organic acids consumed or produced undergo dissociation, releasing hydrogen ions in the fermentation medium, thereby influencing the pH (fall). Some hydrogen ions present in the fermentation medium come from the assimilation of nitrogen sources, in particular ammonium ions, and also from some amino acids, thus, contributing to the drop in pH by the assimilation of positively charged amino acids [26].

Fig. 2.

Effect of pineapple and watermelon concentrations and time on pH.

Fig. 3.

Interactive effect of pineapple, watermelon and guava on pH.

Fig. 4.

Variation of pH as a function of fermentation duration.

Table 5 presents the coefficient of factors and interactions and their impact on pH.

Table 5.

Analysis of Variance for pH follow-up.

| Terms | Coefficient | Level of Significance |

|---|---|---|

| A | +3.32 | |

| B | +3.40 | |

| C | +3.30 | 0.0164 |

| AB | −0.2457 | 0.0012 |

| AC | +0.3857 | 0.0001 |

| AD | −0.1394 | 0.0243 |

| BC | −0.2340 | 0.2414 |

| BD | −0.0290 | 0.4120 |

| CD | −0.0200 | 0.0027 |

| ABC | +5.24 | 0.1875 |

| ABD | +0.1619 | 0.0683 |

| ACD | +0.2418 | 0.9771 |

| BCD | +0.0034 | 0.0690 |

| ABCD | −5.04 |

AC and ABC interactions with significant levels of 0.0012 and 0.0027, respectively, have a positive influence; that is, they contribute to pH increase. The AB, AD and BC interactions with significant levels of 0.0164, 0.0001 and 0.0243, respectively negatively impact the pH and favor its decrease.

3.2.2. Impact of factors on alcoholic content during fermentation

The purpose of alcoholic fermentation is to transform, through the action of yeast, sugar in the medium into alcohol, principally ethanol, which is the main component of wine after water.

The mathematical model translating this response is expressed by Eq. (6), and the analysis of variance is shown in Table 6.

| (6) |

Table 6.

Analysis of Variance for Alcohol content follow-up.

| Terms | Coefficient | Level of significance |

|---|---|---|

| A | +9.44 | |

| B | +9.66 | |

| C | +6.58 | 0.6855 |

| AB | −1.12 | 0.2501 |

| AC | +3.35 | 0.0901 |

| AD | +0.9499 | 0.3503 |

| BC | +2.68 | 0.0100 |

| BD | +1.74 | 0.0449 |

| CD | +1.19 | 0.5798 |

| ABD | −1.33 | 0.0515 |

| ACD | +5.61 | 0.7286 |

| BCD | +0.8373 | 0.1359 |

| AD2 | −1.40 | 0.0659 |

| BD2 | −1.81 | 0.7495 |

| CD2 | −0.2727 | 0.5571 |

| ABD2 | +2.19 | 0.2672 |

| ACD2 | −4.32 | 0.9556 |

| BCD2 | −0.2059 |

This model has a coefficient of determination, R2 of 0.9546 and an adjusted R2 of 0.8261; the two being very close, validates the model for the follow-up of the alcohol evolution.

Equation (6): Mathematical model for the evolution of the alcoholic content during the fermentation of wines.

The result of this transformation (sugar to ethanol) leads to an increase in ethyl alcohol in the medium with a longer fermentation time (Fig. 5) [36]. An increase in the alcohol level with the proportions of watermelon would be justified by the fact that it is such an easily fermentable material (due to its low dry matter content), although watermelon contains less sugars compared to the other fruits. With the fermentation time the alcohol content increases even more, as it is the main product of fermentation [36]. This behavior shows that the BD interaction (Fig. 6) influences the production of alcohol. On the other hand, guava, despite its high sugar content, portrayed a low alcohol production. This behavior could be due to the fruit's high viscosity and pectin content. Hence, the interaction CD (Fig. 7) has a negative impact on the evolution of alcohol content (decrease). The quantity of alcohol increases with an increase in pineapple (A). Pineapple is a fruit that tends to ferment during its degradation; therefore, coupled with its high total soluble sugars, it can produce much more alcohol during fermentation. Indeed, the pineapple juice obtained by pressing the fruit is a relatively rich and easily fermentable substrate [37]. Also, the longer the fermentation time, the higher the alcoholic content, as explained by the BD and CD interactions with 0.0100 and 0.0449 levels of significance, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Variation of alcoholic degree as a function of fermentation duration.

Fig. 6.

Effect of watermelon and guava concentrations and time on alcohol.

Fig. 7.

Effect of pineapple and guava concentrations and time on alcohol.

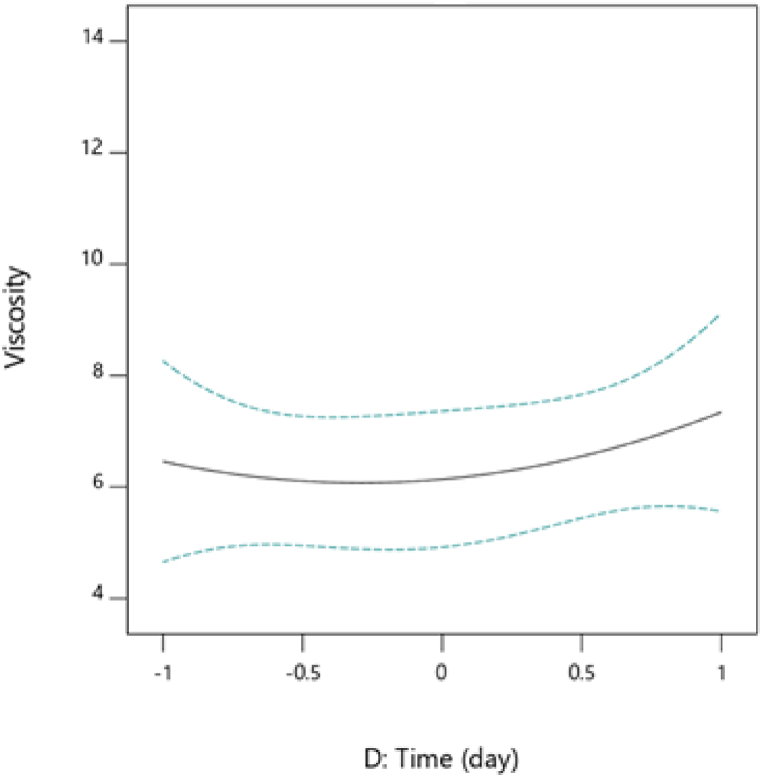

3.2.3. Impact of factors on viscosity

Viscosity is an important criterion in enology as it impacts clarification operations. The mathematical model for the evolution of this response is represented by Eq. (7), and the analysis of variance is shown in Table 7.

| (7) |

Table 7.

Analysis of Variance for Viscosity follow-up.

| Terms | Coefficient | Level of significance |

|---|---|---|

| A | +7.23 | |

| B | +7.19 | |

| C | +11.56 | 0.2297 |

| AB | −5.05 | 0.0604 |

| AC | −8.72 | 0.7968 |

| AD | −0.1819 | 0.0575 |

| BC | −8.92 | 0.6711 |

| BD | −0.3006 | 0.0031 |

| CD | +3.23 | 0.6497 |

| ABD | +1.56 | 0.7266 |

| ACD | −1.22 | 0.2123 |

| BCD | −4.61 | 0.1565 |

| AD2 | −1.89 | 0.2794 |

| BD2 | −1.38 | 0.4371 |

| CD2 | −0.9745 | 0.2650 |

| ABD2 | +6.22 | 0.1508 |

| ACD2 | +8.34 | 0.3634 |

| BCD2 | +5.00 |

Equation (7): Evolution of viscosity during fermentation of wine samples.

This model has a determination coefficient (R2) of 0.9408 and an adjusted R2 of 0.7732; the two being closed validate the model for the follow-up of viscosity.

An increase in viscosity observed with fermentation time (Fig. 8) would partly be due to an increase in alcohol [38]. Indeed, the yeast population present would influence the viscosity thus facilitating its increase. Viscosity is caused by friction between particles as they slide past one another. The viscosity increases with guava (Fig. 9), which could be explained by the sugar content of this fruit and the high presence of pectin in its composition. In fact, sugar reduces the freedom of movement of particles, thereby promoting an increase in viscosity. On the other hand, given the amount of sugar in watermelon, there is a decrease in viscosity with these two fruits. The interaction of the two fruits therefore, contributes in increasing the viscosity of the mixture.

Fig. 8.

Variation of viscosity as a function of fermentation duration.

Fig. 9.

Variation of viscosity as a function of watermelon and guava concentrations.

3.3. Optimization

Using the D-Optimal model, a specification was defined concerning all the dependent variables. The pH, total soluble solids, reducing sugars, and viscosity were minimized, while polyphenols, titratable acidity and alcohol were maximized. This led to a fruit formulation of 69%, 19% and 12% of pineapple, watermelon and guava, respectively, with a fermentation time of 11 days.

3.4. Brandy production from optimal wine sample

3.4.1. Distillation output

A simple distillation unit was set up to separate the alcohol from the optimal wine sample. From a 10 L wine sample at 11 °GL, the volume of distillate (ethanol) obtained was 1 L at 75 °GL giving a distillation yield of 72%.

3.4.2. Physico-chemical characteristics of brandy

After distillation, two brandy samples were formulated: one (E1) diluted with clarified optimal wine, and the second (E2) diluted with distilled water and a roasted bark of Cupressus sempervirens was added to it. The alcoholic content of both samples was fixed at 40°. Both samples were allowed to age for six weeks and then subjected to physico-chemical analyses, the summary of which is shown in Table 8:

Table 8.

Physico-chemical characteristics of brandy.

| Parameters | Brandy (with wine) | Brandy (with distilled water + tree bark) |

|---|---|---|

| Reducing sugars (mg/mL) | 21 ± 2 | 11.1 ± 0.0 |

| Polyphenols (mgGAE/100 mL) | 23 ± 2 | 43 ± 2 |

| Titratable acidity (meq.g tartaric acid/mL) | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.2 |

| Vitamin C (mg/L) | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 80 ± 2 |

| Color (EBC) | 10.0 ± 0.2 | 52.5 ± 0.7 |

Brandy obtained through dilution with wine had more vitamin C, reducing sugars, and a higher rate of organic acids than that diluted with distilled water.

The sample obtained by dilution with distilled water and matured with roasted bark of cypress was richer in polyphenols, similar to spirits aged in wooden barrels. During maturation, the constituents of the wood gradually dissolve in ethanol, thus influencing the taste, flavor and color [39] of the brandy. During the roasting process of the cypress, there is a breakdown of tannins; during aging, the oxygen molecules are further absorbed, oxidizing the dissolved phenolic compounds. The polyphenols found in brandy result from complex chemical processes [39] during roasting and aging.

It also confirms from these analyses that adding roasted cypress brings vitamin C (80 mg/L) to the brandy. In fact, studies on the composition of cypress and other conifers by Raal et al. [40] showed that this tree contains vitamin C in its needles and bark. However, the brandy sample obtained by dilution with wine was richer in vitamin C or l-ascorbic acid, synthesized during fermentation by d-glucose yeasts. Vitamin C, a powerful antioxidant, has a higher potential than polyphenols [39]. This brandy has a higher titratable acidity due to the synthesis of organic acids during fermentation [26]. Polyphenols, vitamin C and organic acids are antioxidants that play an important role in health [39], providing brandy with good therapeutic properties.

3.5. Sensory analysis

A total of 30 panelists of an average age of 40, all of whom were usual brandy consumers, were given the products (E1 and E2) for analysis. A 7-scale hedonic test was carried out based on the color, brightness, aroma, taste, astringency, flavor and overall appreciation. The results obtained are illustrated in Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

Average variation in sensory attributes.

Visually, sample E2 had a better appearance for brightness and color. On the other hand, sample E1 was appreciated to have a better taste (for its fruitiness) and presented a less pronounced astringency. On the aromatic level, the two samples were equally appreciated since they had precise aroma sources. The general appreciation is the average of all the descriptors, combining the preferences of the consumers. Of the two samples submitted for analysis, sample E1 was most appreciated. This behavior implies that consumers appreciated brandy that still has the aromas of the fruits, while having a high alcohol content.

3.5.1. Limitations of the study

The experimental design adopted for the best wine formulation consisted of three material factors (the volumes of Pineapple, watermelon and guava respectively) and a process factor (fermentation time). Other factors could have been considered, such as fermentation temperature, the quantity of yeast inoculated and sugar concentration before fermentation. This could have made the design complicated to handle with so many experiments.

The roasting operation of the Cupressus sempervirens tree bark was not optimized. Optimization concerning particle size, roasting temperature and time could have influenced the characteristics of the roasted product. Also, the aging process of the young brandy has to be studied concerning wine: spine tree ratio, aging temperature and duration. These could be carried out to give the brandy a specific and well defined character.

4. Conclusion

A blend of the nectars of Ananas comosus (pineapple), Citrullus lanatus (watermelon) and Psidium guajava (69:19:12) was achieved and an appropriate fermentation duration (11 days) for the formulation of the best wine sample and eventual brandy obtained through distillation, dilution and aging. Brandy sample obtained through dilution with fruit wine and aged with roasted spine bark was generally accepted through a hedonic consumer test. Consuming such natural products in an appropriate quantity could contribute to health as it is rich in antioxidants (polyphenols and vitamin C). These fruits can be exploited for their technological and functional properties. In addition to reducing postharvest losses, their exploitation will trigger massive cultivation and improve local farmers’ economies.

This study could be extended to other tropical fruits in the region.

Author contribution statement

Agwanande Ambindei Wilson; Kekel Emiliene: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Ngwasiri Pride Ndasi: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Nso Emmanuel Jong: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Banque des Etats de l'Afrique Centrale (BEAC) direction de la recherche; 2017. Dépenses publiques et croissance agricole au Cameroun; p. p2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ordovas J.M., Kaput J., Corella D. Nutrition in the genomics era: cardiovascular disease risk and the Mediterranean diet. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007;51(10):1293–1299. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu R.H. Dietary bioactive compounds and their health implications. J. Food Sci. 2013;78(s1):A18–A25. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xavier A.A., Perez-Galvez A. Carotenoids as a source of antioxidants in the diet. Subcell. Biochem. 2016;79:359–375. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-39126-7_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaparapu J., Pragada P.M., Geddada M.N.R. In: Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals Bioactive Components, Formulations and Innovations 241 – 260. Egbuna C., Dable-Tupas G., editors. Springer Nature Switzerland AG; 2020. Fruits and vegetables and its nutritional benefits. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ministère de l'Agriculture et du Développement Rural (MINADER) Direction des Enquêtes et Statistiques Agricoles; 2018. AGRI-STAT Cameroun. Annuaire des Statistiques du Secteur Agricole Campagnes 2017; p. 188. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institut National de la Statistique (INS) Bureau des Enquêtes; 2020. Importations des boissons alcooliques. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epsein B.S. Reaktion Books Ltd, 33 Great Sutton Street; London, UK: 2014. Brandy: A Global History; p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hauchard D. 2020. Les Spiritueux, Technologie en boulangerie pâtisserie; p. 9p. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park S.Y., Lee S.J. The health benefits of Jeju Gamgyul (Citrus unshiu Marc.) brandy and wine. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2017;5(2):110–115. doi: 10.12691/jfnr-5-2-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhiman A., Attri S. In: Handbook of Enology: Principles, Practices and Recent Innovations Volume III. Joshi V.K., editor. Asiatech Publisher, INC.; New Delhi: 2011. Production of brandy; p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- 12.ANSES (Agence Nationale de Sécurité de l'Alimentation, de l'Environnement et du Travail) 2017. Table de composition nutritionnelle des aliments (Ciqual) [Google Scholar]

- 13.AOAC (Association of Analytical Chemist) In: Official Method of Analysis 925.10. fifteenth ed. Helrich Kenneth., editor. Wilson Boulevard; Arlington, Virginia 22201 USA: 1990. p. 2200. (Suite 400). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helmenstine A.M. Vitamin C determination by iodine titration. Thought. 2019;Aug. 27:2020. thoughtco.com/vitamin-c-determination-by-iodine-titration-606322 [Google Scholar]

- 15.AFNOR . fourth ed. La Defense; Paris: 1993. Recueils of French Standards, Quality Control of Food Products, Milk and Milk Products, Physicochemical Analyzes. Afnor-Dgccrf; p. 562. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marigo G. On one fractioning methods and estimations of phenolic compounds in vegetables. Analysis. 1973;2:106–110. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamuela-Raventós R.M. In: Measurement of Antioxidant Activity and Capacity, Recent Trends and Applications. Apak R., Capanoglu E., Shahidi F., editors. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 111 River Street; Hoboken, USA: 2018. Folin–Ciocalteu method for the measurement of total phenolic content and antioxidant capacity; pp. 107–155. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alejandro H.L., Daniel A., Sánchez F., Zenaida Z.S., Itzel G.B., Tzvetanka D.D., Alma X.A.A. Quantification of reducing sugars based on the qualitative technique of benedict. ACS Omega. 2020;5(50):32403–32410. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c04467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeLange A.J. The standard reference method of beer color specification as the basis for a new method of beer color reporting. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2008;66(3):143–150. doi: 10.1094/ASBCJ-2008-0707-01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raherimandimby R. Mémoire de fin d’étude soutenu le 17 mars 2004. 2003. Conception d’une cuve de fermentation-Etude comparative de la fermentation et de la distillation de canne à sucre, ananas et litchi. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azonkpini S., Chougourou C.D., Aboudou K., Hedible L., Soumanou M.M. Evaluation de la qualité de l’ananas (Ananas comosus (L.) Merr.) de cinq itinéraires techniques de production dans la Commune d'Allada au Bénin. Rev. Int. Sci. Appl. 2019;2(1):48–61. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herrero M., Cuesta I., García L.A., Díaz M. Changes in organic acids during Malolactic fermentation at different temperatures in yeast-fermented apple juice. J. Inst. Brew. 1999;105:191–196. doi: 10.1002/j.2050-0416.1999.tb00019.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tensaout F., Gaoua A. Caractéristiques chimiques et propriétés antioxydantes de la goyave. Psidium guajava (mémoire) 2018;57:11–12. [Google Scholar]

- 24.França M.B., Panek A.D. Oxidative stress and its effects during dehydration. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2007;146(4):621–631. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hassan R., Mohammad H.F., Reza K. Polyphenols and their benefits: a review. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017;20(sup2):1700–1741. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2017.1354017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akin H. Evolution du pH pendant la fermentation alcoolique de moûts de raisins : modélisation et interprétation métabolique. Thèse soutenue en. 2008;2008:4–10. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Institut National de la Propriété Industrielle (INPI) Procédé de fabrication de jus de fruits, jus de fruits correspondant au pur jus de goyave. Journal officiel de l’office européen des brevets. 2013:280. n°12/82. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jing-Wang P., Yue S., Huijuan Z., Xingxing D., Yubin W., Yue M., Xiaoyan Z., Chao Z. Characterization and Comparison of unfermented and fermented seed-watermelon juice. J. Food Qual. 2018;2018:9. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soatsara Y. Contribution à la valorisation des fruits et légumes : Cas du chutney de Goyave et du chutney de Carotte. Ecole supérieure polytechnique d’Antananarivo. 2013:6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sylvestre M. Université du Québec à Montréal; 2011. Facteurs qui influencent la cinétique de fermentation chez la fléole des près (Phileum pratense L.) pp. 80–123. Mémoire présenté en janvier 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Biguzzi C. L’amélioration de la qualité nutritionnelle est-elle compatible avec le maintien de la qualité sensorielle ? L’exemple des biscuits. thèse rédigée et soutenue le 15 février. 2013;98:5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun C.Q., O'Connor C.J., Turner S.J., Lewis G.D., Stanley R.A., Roberton A.M. The effect of pH on the inhibition of bacterial growth by physiological concentrations of butyric acid: implications for neonates fed on suckled milk. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1998;113(2):117–131. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(98)00025-8. PMID : 9717513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Isnawati, Trimulyono G. Temperature range and degree of acidity growth of isolate of indigenous bacteria on fermented feed “fermege”. J. Phys. Conf. 2018;953 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim C., Wilkins K., Bowers M., Wynn C., Ndegwa E. Influence of pH and temperature on growth characteristics of leading foodborne pathogens in a laboratory medium and select food beverages. Austin Food Sci. 2018;3(1):1031. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delroise A. CIRAD FLHOR La Reunion Pole agroalimentaire; 2003. Caractérisation de la qualité et étude du potentiel de maturation de la mangue (Mangifera indica L. Lirfa) en fonction de son stade de récolte; p. 76. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ribéreau-Gayon P., Glories Y., Maujean A., Dubourdieu D. 2006. Handbook of Enology: the Chemistry of Wine Stabilization and Treatments; p. 58. volume 2, second ed. [Google Scholar]

- 37.CTA Côte d'Ivoire : fermentation alcoolique du Jus d'Ananas. Spore. 1986;3 280 (14-52) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nurgel C., Pickering G. Contribution of glycerol, ethanol and sugar to the perception of viscosity and density elicited by model white wines. J. Texture Study. 2005;36:303–323. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanaka Y. Positional variations of polyphenols in different compounds. Res. Support. 2010;119(4):391–404. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raal F., Alawi A., Omar M., Wafa O. Cardiovascular risk factor burden in Africa and the Middle East across country income categories. Arch. Publ. Health. 2018;76(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s13690-018-0257-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.