Abstract

In the last decade, the use of sustainability reporting as a tool for communicating and reporting on the performance of sustainability objectives by companies has led to a growing awareness of its value and development in the corporate world. Therefore, exploring this phenomenon for a better understanding and identifying its characteristic elements is important. This study aims to systematically review the literature to establish the distinctive elements of sustainability reporting and provide a complete theoretical framework that allows the classification of the drivers that are crucial for adopting sustainability reporting. Through the analysis, we describe the characteristic elements of sustainability reporting in a homogeneous and concise summary. The drivers that result, may prove useful not only in the context of non-financial reporting but also in encouraging adequate economic-business reflections that may inspire new research trajectories for scholars in this field.

Keywords: Legitimacy theory, Stakeholder theory, Institutional theory, Non-financial information, Sustainability reporting, Institutional drivers

1. Introduction

Over the last decade, scholars have become increasingly aware about the relevance of sustainability reporting in the corporate sector and international organisations. Particularly, global initiatives have brought this heterogeneous issue to the forefront [1]. Changes in the form of new reporting requirements have been introduced by various laws, regulations, standards, guidelines and codes. The disclosure of such information—both mandatory and voluntary—is a common practise of companies [2]. However, the definitions’ heterogeneity in the corporate context and the topic’s international significance - whereby the evolution of the corporate system and its ability to develop a long-term value for the company considering the economic, social, and environmental performances is characterised [1] - suggest an exigency for further investigating the topic. Therefore, building a theoretical framework from the extant literature is a prerequisite for understanding the concept of value creation through sustainability reporting in the context of the company system in the third millennium. The business system’s complexity is ever-increasing owing to complicated business dynamics and scientific and technological progress. A complicated problem arises out of multiple fragments that are difficult to code. Henceforth, decoding these multiple fragments, which can lead to a simpler solution for complicated phenomena, is recommended. Similarly, disorder and uncertainty in business systems can be attributed to multiple interdependent parts; it is deduced that complexity is a daily challenge for managers and companies.

The paper is structured as follows: in the subsequent section, the theoretical background and research objective are presented, while the methodology used is described in section 3. Further, section 4 presents the results of the systematic literature review, and section 5 provides a discussion of the results; section 6 elucidates the present study’s conclusions.

2. Background

The topic of ''sustainability reporting'' is experiencing considerable interest at a scientific level. Recent years have seen a growth in the adoption of SR both in response to stakeholders interested in social and environmental performance and to investors who rely on this type of non-financial data as an indicator of underlying business risks and likely future financial performance. Previous studies have provided a series of theoretical constructs to analyse the role of SR in the company—both from strategic and operational perspectives. The main theories driving the SR are theory of legitimacy [3,4], theory of stakeholders [5], and institutional theory [[6], [7], [8], [9]], alongside other theories.

Moreover, the existing literature on disclosure in a heterogeneous and fragmented manner indicates that some internal factors, such as the size of the company [4,[10], [11], [12], [13]], the sector to which they belong [14], and the CDA [[15], [16], [17]]; and some external factors, such as the legal, economic, financial and cultural systems of the country of origin, potentially influence the nature and extent of disclosure [[18], [19], [20], [21]].

The systematic analysis of the literature was conducted with the aim of developing a unitary and compact understanding of the concept of Sustainability Reporting (SR) in the multi-theory context, presenting the drivers of adoption of sustainability reporting. The present study focuses on corporate sustainability since 2010, as it represents the benchmark for corporate best practices and marks the fusion of theoretical references with practical solutions and implications (IIRC, 2010). This study allows to present a complete and timely overview of the factors influencing the adoption of SR to overcome the fragmented literature and allows to trace the areas of intervention and their evolution.

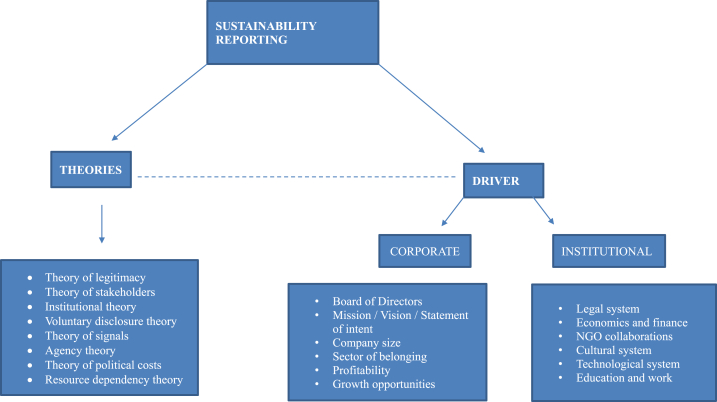

Fig. 1 highlights the key points derived from the systematic literature review. Sustainability reporting includes a multi-theoretical base of reference from which to define corporate and institutional drivers.

Fig. 1.

Drivers of SR. Source: Original material from the author.

3. Methods

To accomplish the study’s objective, we adopted a systematic literature review—a rigorous and well-planned analysis, wherein specific research questions are answered through identification, selection, and critical evaluation of the results of the studies shortlisted from the extant literature [22]. This study’s objective is creating a comprehensive collection of studies through a systematic procedure. A data extraction module was designed to obtain the necessary information on the characteristics and findings of the studies included in this research. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, which are considered a useful compass for systematic reviews, were followed. The studies were selected based on author-year, title, research objective, theoretical framework, research methodology, results, and future implications [23].

The research was divided into two phases indicated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Research phases.

| PHASE 1 SCREENING FOR DATASET PREPARATION | Scopus database |

|---|---|

| PHASE 2 OF THE SAMPLE’S ANALYSIS | A) Collection for quote |

| B) Collection by titles and abstracts | |

| C) Full text collection |

Source: Original material from the author.

3.1. Phase 1 screening for dataset preparation

The Scopus database was consulted to collect the relevant studies. Scopus is among the most popular search engines, as it features usability, interdisciplinary variety, and an interface that makes it easy for the user to find updated and expertly curated related results [24].

Table 2 presents the inclusion criteria followed during the screening of the dataset (keywords, Boolean operators, document type, subject area, language). The search string was set as follows.

Table 2.

Inclusion criteria for the dataset preparation.

| keywords | ‘Integrated’, ‘Non-financial’, ‘Sustainability’, ‘Reporting’, ‘Company’ | These keywords were selected after in-depth review of the scientific articles published on the subject. Particular attention was paid to the term ‘non-financial’, proposed with the orthographic sign ‘-’ as it is semantically correct and used in the scientific context. |

|---|---|---|

| BOOLEAN OPERATORS | ‘And’, ‘Or’ | Both operators were employed as they linked the conditions together. Specifically, ‘And’ was used where results should have matched with all the specified keywords, while ‘Or’ was used where results were supposed to match with one of the specified keywords. |

| DOCUMENT TYPE | Article | |

| SUBJECT AREAS | Business, Management, and Accounting | Appropriate subject area in relation to the topic under study. |

| LANGUAGE | English | |

| TIME PERIOD | January 01, 2010–04/22/2022 | 2010 is the marking year for the creation and establishment of the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) to promote and disseminate the new sustainability reporting system. |

Source: Original material from the author.

((integrated) OR (non-financial) OR (sustainability) AND (reporting) AND (company))

On completion of Phase 1, 994 records were derived. These were further submitted to Phase 2 of the sample’s analysis.

Furthermore, a word cloud representing the geographical distribution of the exact keywords, as identified through the Scopus search engine, is presented in Fig. 2. It displays a detailed correspondence concerning the topic and possesses the potential to delimit the results even more meticulously.

Fig. 2.

Word cloud representation of the exact keywords. Source: Original material from the author.

3.2. Phase 2 Sample’s analysis

In Phase 2, the extracted data samples were further shortlisted based on the following modes of collection: A) collection for quote, B) collection by titles and abstracts, C) full text collection.

-

(A)

Collection for quote

In this sub-phase, the articles were shortlisted through a manual review process wherein the duplicates were identified and excluded from the sample. Additionally, the relevance of articles with more citations was considered an inclusion criterion. To identify the relevance of the articles with more citations, classification criteria based on the Likert scale model approach were developed, as presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Likert scale model on citations.

| Likert scale | Citations | Number of Articles | Percentage of Articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highly relevant | 301 and above | 6 | 0.6% |

| Relevant | 201 to 300 | 6 | 0.6% |

| Somewhat relevant | 101 to 200 | 42 | 4.3% |

| Not very relevant | 51 to 100 | 93 | 9.5% |

| Not relevant | 0 to 50 | 846 | 85% |

| Total | 993 | 100% |

Source: Original material from the author.

This model was appropriate for the present research to refine the congruity of the same to a qualitative sample of articles that could confirm the propositions and/or assertions (items) on the specific topic. The Likert scale model [25] requires the collection of several statements on the subject under analysis, thus making it possible to measure variables of varying intensity with homogeneous contents to the research question. In this study, these were the extracted citations divided into homogeneous classes.

At the end of this process, the articles that fell into the classes of citations as highly relevant, relevant and somewhat relevant were considered and a total of 54 articles were selected from this activity. These articles were downloaded and read by a study group comprising three people knowledgeable about the topic.

-

(B)

Collection by titles and abstracts

Simultaneously, the study group read the titles and abstracts, and after several meetings and discussions, the members reached a concordant result. At this stage, the exclusion criteria concern the abstracts. Those abstracts whose topics were not consistent with the aims of this research were excluded from further analysis. This agreement reduced the sample to 41 articles, from which the information required for a critical analysis of the topic was extracted.

-

(C)

Full text collection

Based on the same methodology and exclusion criteria, the working group read the articles in-depth, further refining the sample to 24 articles eligible for the next data extraction phase. Fig. 3 presents the workflow of the phases and sub-phases using the PRISMA Statement Flowchart technique. It is useful for graphically representing the selection process and reflecting the progress in the identification, selection, evaluation, and synthesis of studies [23].

Fig. 3.

PRISMA statement flowchart.

4. Results

4.1. Review of the main theories

The conceptual framework developed in this study includes various theories explaining the theme of non-financial reporting. Cormier et al. [26] proposed that sustainability reporting practices are a rather complex phenomenon that cannot be explained with a single theory [1]. Hence, it is essential to present a complete excursus of these theories for determining the drivers through subsequent analysis. The theories presented are legitimacy theory, stakeholder theory, institutional theory, voluntary disclosure theory, signal theory, agency theory, political cost theory, and resource dependence theory.

Legitimacy theory is based on the paradigm of the ‘social contract’ existing between the company and the society [3,4]. If a company wants to continue its activity, it must be perceived as legitimate by the surrounding companies. A company only achieves legitimacy if it acts within a system of norms and values in such a way that it not only behaves as expected, but also informs the other companies about its actions. Therefore, when companies fail to meet public expectations and requirements, they are exposed to greater pressure, which is accompanied by a higher level of public scrutiny and monitoring, posing a further risk to legitimacy [27]. Consequently, companies with lower environmental performance come under greater public pressure. Hence, they voluntarily and selectively disclose information to reduce the negative effect on the legitimacy and their reputation due to poor performance. In this context, the development of SR is an essential risk-management tool to improve social perception and a mechanism to maintain and protect legitimacy by meeting society’s expectations regarding the firm’s commitments [27]. This theory is placed in a broader context than socio-political theories, which suggest that corporate reporting issues should be investigated considering the political, social, and institutional framework wherein activities occur [27].

Legitimacy theory can be linked to stakeholder theory, which argues that organisations should create wealth for all the participants (stakeholders) affected by the objectives and business processes. This is in contrast with the traditional financial model, which is based on value creation exclusively for the shareholder [28]. Therefore, informing stakeholders about the economic, social and environmental impacts of the company’s performance is necessary; stakeholders are implicitly obliged to correct the company’s behaviour [5].

Legitimacy theory works in two directions. On the one hand, it addresses the dynamic and complex relationship existing between the company and the surrounding environment. On the other hand, it evaluates the abilities of the companies to balance the heterogeneous needs of various stakeholders [4,29]. Sustainability reporting is fundamental. As it presents a broader report of corporate performance rather than the classic corporate statements; thereby, it can satisfy the information needs of the various stakeholders [28].

Along similar lines, institutional theory integrates both legitimacy and stakeholder theory to understand how organisations recognise and cope with the dynamic social and institutional pressures and the expectations for maintaining legitimacy [4,30]. According to institutional theory, organisations are economic entities that operate in an environment that contains institutions that influence their behaviour and expectations [[6], [7], [8], [9]]. Consequently, organisations need to interact with the environment such that they acquire legitimacy, resources, and stability to improve their survival prospects. The integration and inclusion of the ‘institution’ factor leads to sustainability reporting, which is used as a tool to indicate that the company remains within the acceptable boundaries of the business [4].

Considering the importance of the ‘institution’ factor, institutional theory includes a fundamental dimension known as ‘ISOMORPHISM’—that is, the adaptation of an institutional practice by an organisation [4,31]—and it is believed to promote the companies’ stability, endowing them with greater power and institutional legitimacy [9]. Isomorphism can be classified into the following three types: coercive, mimetic, and normative [4,32]. Coercive isomorphism refers to the process whereby various organisations modify their institutional practices due to the pressure exerted by the stakeholders. In this context, companies use sustainability reporting as a tool to address the economic, social, environmental, and ethical values and concerns of those stakeholders who have the greatest power over the company. The mimetic isomorphism occurs when—to face uncertain situations—an organisation spontaneously begins imitating other organisations in the same sector that they naturally believe to be successful. In this context, sustainability reporting acts as a tool for companies to improve their processes, avoid the risk of losing legitimacy, and maintain or improve their competitive advantage [4,33]. The final isomorphic process is a normative isomorphism related to the pressure of norms to adopt certain institutional practises and meet professional expectations. In this scenario, sustainability reporting can influence the need to provide information to stakeholders [4,32].

Considering that adopting and implementing sustainability reporting is a process involving a great deal of information, voluntary disclosure theory suggests that companies should be ready to disclose information and reduce information asymmetries voluntarily, but only if the benefits outweigh the costs and if the increase in reputation reduces the capital cost [27,34,35]. Furthermore, based on this theory, companies with better environmental performance will probably be more inclined to disseminate objective, verifiable, and authentic information precisely to demonstrate credibility; conversely, companies with lower environmental performance will provide ambiguous and unverifiable information [27]. Similarly, according to signal theory, companies are inclined to provide additional information as a signal to reduce information asymmetries, cater to stakeholder expectations, optimise financing costs, and increase enterprise value [10,36]. A company’s sustainability information can be considered asymmetric information when extracting credible information on sustainability aspects is difficult for parties outside the company. Companies can reduce information asymmetries by proactively reporting their sustainability initiatives [37]. Agency theory addresses the problem of contrasting interests between owner and manager, highlighting how this can trigger conflicts by interfering with the proper functioning of the company [5]. This discrepancy between the actors increases agency costs; therefore, sustainability reporting plays a significant role in reducing this asymmetry [13]. According to the political cost theory paradigm, organisations disclose information voluntarily to reduce political costs (taxes, fees, etc.), and to obtain benefits such as concessions or subsidies [10]. Finally, theory of dependence on resources assumes that companies, not being self-sufficient, must draw on resources in their respective context; then, relationships and societies with other actors are analysed, evaluating their contributions based on the extent to which they facilitate the maximisation of its performance [5,38,39].

4.2. Drivers of SR

Synthesising the theoretical framework allows the identification and classification of the main drivers as described in the literature on the subject. In particular, this study proposes a classification of drivers that distinguishes between ‘institutional drivers’ and ‘entrepreneurial drivers’. Institutional drivers refer to a set of external drivers related to the specific institutional environment in the organisation’s country of origin [40]. Corporate drivers refer to the characteristics that are directly related to the company [10]. Table 4 presents the classification of drivers according to their respective characteristics.

Table 4.

Drivers of sustainability reporting.

| BUSINESS DRIVERS | INSTITUTIONAL DRIVERS |

|---|---|

| - Board of Directors | - Legal system |

| - Mission/Vision/Statement of Intent | - Economics and finance |

| - Company size | - NGO Collaborations |

| - Sector of belonging | - Cultural system |

| - Profitability | - Technological system |

| - Growth opportunity | - Education and work |

Source: Original material from the author.

4.2.1. Business drivers

4.2.1.1. Board of directors

The link between corporate governance and sustainability has been thoroughly discussed in the literature by Amran et al. [15], Fernandez-Feijoo et al. [16], Frias-Aceituno et al. [2], and Fuente et al. [17]. The administration representing the governing body of the company has the task of protecting the stakeholders’ interests by possibly reducing opportunistic behaviour. Therefore, corporate governance mechanisms are important for corporate social responsibility practises, and they promote the development of long-term competitive advantage [2]. Several variables related to governance are discussed in the literature—namely, size, independence, and composition.

-

•

Dimension of the board of directors

The literature is not unanimous on the relevance of the dimension of board of directors for disseminating sustainability-related information [17,41]. The studies by Frias-Aceituno et al. [2] and Fuente et al. [17] found that boards of larger companies face critical questions. Considering the complexity of disclosure, a consistent number of board members with the right experience and background to deal with the issues while ensuring better oversight is needed. Consequently, the amount of information provided will be positively affected, indicating a positive correlation between board size and reporting. This is in line with the guidelines of the Global Reporting Initiative, as a larger number of board members provides the opportunity to bring in different viewpoints and experiences. However, Amran et al. [15] and Lakhal [42] reported that no significant relationship exists between board size and sustainability reporting. This could be justified by the fact that the effectiveness of the board itself compensates for that of the reporting. Once the strategies have positive resolutions, fewer efforts must be invested into disclosure practices.

-

•

Independence of the board of directors

The literature regarding the relationship between independence and reporting is inconsistent. Some scholars believe that an independent board is a fundamental resource as it exerts control over managers’ opportunistic behaviour [2,43,44]. The presence of independent executive directors is positively correlated with responsible behaviour and guarantees transparency. They want to preserve their respective reputations and, therefore, act as a control mechanism and focus on the satisfaction of all interested parties by responding to societal demands. These considerations result in the company acting more responsibly and transparently and disclosing more authentic information, which creates a positive correlation between board independence and the production of sustainability reporting in accordance with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) guidelines [17]. However, Amran et al. [15] and Frias-Aceituno et al. [2] did not find a significant relationship between the two variables, as it is likely that the influence of board members on reporting is limited as they are more involved in day-to-day decision making.

-

•

Composition of the board of directors

The literature refers to diversity when discussing—that is, the heterogeneous characteristics of the members of the board in relation to training, interests, and above all, nationality and gender [17]. Academic research has addressed the issue of diversity especially in terms of ‘gender’, as it has been reported that women are more oriented towards the quality of life, social issues, and women-related problems—possibly because they are less self-centred at the economic level and often tend to step into the roles of wives and mothers in the professional environment [2,45], by effectively solving problems and promoting relationships [17]. Conversely, men are more oriented towards material success and income [28]. The consequence of this consideration is a positive relationship between gender diversity and corporate reporting [2,15,46]. However, Fernandez-Feijoo et al. (2014b), in an analysis of corporate social responsibility (CSR) reports recorded by different countries in the GRI between 2008 and 2010, indicated that the positive impact was achieved at the reporting level when companies had at least three women on the board. These findings were also supported by an empirical study by Amran et al. [15], in which they observed companies with fewer than three women on the board of directors. The results did not indicate such an association, demonstrating that the relevance of female orientation occurs with a minimum of three women.

-

•

Activities of the board of directors

Another important aspect of the board is the frequency of its meetings. The literature seems rather fragmented, as there are two schools of thought regarding the impact of board activity on reporting. On the one hand, it is believed that an excessive number of meetings indicates ineffectiveness and that board members’ authority is exceeded, which would negatively impact the company [2,17]. On the other hand, Lipton and Lorsch [47], Frias-Aceituno et al. [2] and Fuente et al. [17] believed and empirically proved that an active board is more effective, as numerous meetings indicate greater and better management control. Companies that exercise the supervisory function more effectively also tend to reduce information asymmetry.

-

•

CSR committees

Another relevant variable concerning the effectiveness of the board of directors is the establishment of committees within it. On this aspect, the literature unanimously agrees that establishing committees, in general, is a positive element. If we consider the numerous activities that the board must deal with, delegating some tasks allows it to improve its efficiency [17]. In the area of sustainability, the positive effect is even more evident. A CSR committee is perceived as a resource for a company, as experience and knowledge promote responsible management as a strategy and spur the organisation to implement this strategy by managing risks and demonstrating CSR commitment to stakeholders [17,48]. Accordingly, a positive correlation exists between the presence of a CSR committee and quality (GRI guidelines) of reporting.

4.2.1.2. Vision/mission/mission statement

Another driving force related to reporting is the vision or mission, which is linked to the CSR values and statement of purpose. Integrating the CSR values into the vision or mission is a sustainable resource management strategy that supports their legitimacy and is anchored in a mission statement. The latter is important as it provides guidance for action and serves as a basis for all aspects of the decision-making process. Companies that frame a statement of purpose and have CSR-related goals and missions are more likely to disclose their activities and publish more reports [4], thus ensuring a positive association with sustainability reporting [15].

4.2.1.3. Company size

Several studies have analysed the impact of firm size on sustainability reporting—including Amran and Haniffa [4], Frias-Aceituno et al. [10], Lock and Seele [11], Ehnert et al. [12], and Kuzey and Uyar [13]—highlighting a positive relationship between company size and reporting.

Larger companies’ business characteristics considerably differ from those of smaller ones—particularly, a greater exposure to capital markets, which significantly impacts disclosure [10]. The activities of large companies affect various stakeholders, and due to the mimetic isomorphism of institutional theory, numerous organisations tend to imitate the practices of competitors to retain their market share [4].

Moreover, they rely on external funding, which increases agency costs; reporting is used as a tool to reduce these costs, limit information asymmetries, and enable greater competitive market access. As larger companies are more visible in the market and more concerned with their public image, they are forced to increase the level of disclosure [10]. As they are also subject to greater public scrutiny, they require more resources (legitimacy theory) [40] and face greater pressure from stakeholders [13].

4.2.1.4. Sector of belonging

According to institutional theory, mimetic isomorphism suggests that companies operating in the same sector will adopt similar strategies and practices for information disclosure. In particular, they are inspired by those perceived as more effective [4]. However, not all sectors behave equally. Companies belonging to environmentally sensitive sectors are required to disclose environmental aspects, as they are more likely to harm the environment and are, therefore, subject to stricter regulations. Companies that produce goods rather than services are more likely to disclose because they are likely to exhibit greater environmental impacts and use the external guarantee of their reports to increase their credibility and strengthen their legitimacy [13]. Fernandez-Feijoo [14] reported that reporting by companies belonging to certain sectors having greater stakeholder pressure is different and, notably, consistent with the sector the company belongs to.

4.2.1.5. Profitability

The relationship between profitability and sustainability disclosure is considerably complex, as there are no clear conclusions yet. Major disclosure theories suggest that the two are positively related. According to agency theory, managers of profitable companies use disclosure to gain personal advantage, such as ensuring the stability of their positions and increasing their level of remunerations [10]. From the perspective of reporting theory, profitability can be considered an indicator of the quality of the investments; when high returns are achieved, there is a greater incentive to disclose information, thus reducing the risk of attracting negative views from the market. Profitable companies would publish information to distinguish themselves from less successful ones, to raise capital at the lowest possible cost, and to avoid a reduction in their share price [10]. According to political cost theory, companies voluntarily disclose information when high returns are achieved to justify their profits [10].

From the perspective of stakeholder theory, interest groups claim the resources of the company. In the process, they are expected to adopt appropriate corporate behaviour, such as consideration for the environment and an interest in developing fair working relationships. In cases wherein the company does not act with social responsibility, the resulting costs could become significant, leading to a financial burden that can reduce profits. Conversely, if companies adopt socially responsible policies, they are more profitable, and socially responsible investments will provide an incentive for companies to increase investment in CSR programs [5,49]. Resource availability theory argues that the most evident and explicit connection between sustainability and profitability reporting practices can be established on the basis of economic resources’ availability [13].

Despite the consistency of the theoretical arguments, the results are not convergent at the empirical level. Rodriguez-Fernandez [5] indicated that the social is profitable and the profitable is social, thereby creating a vicious circle. Additionally, Surroca et al. [50] found a positive reciprocal relationship between profitability and sustainability disclosure. Frias-Aceituno et al. [10] and Kuzey and Uyar [13] suggested that a weak relationship exists between the two, as the most profitable companies tend to devote most of their resources to developing sustainability reporting and improving their public actions. Therefore, profitability does not exhibit such a strong influence.

4.2.1.6. Growth opportunity

According to agency’s theory, companies with greater growth opportunities will disclose more information to reduce costs and to limit the information asymmetry, which can negatively impact the company as it causes lower trust levels among the operating subjects [10]. In light of legitimacy theory, growth opportunities encourage businesses to sustainable practices and strategies, and reporting is legitimately used in such operations [13]. Based on the theoretical framework, assumedly, a positive correlation exists between growth opportunities and the production of the sustainability report; however, no statistically significant correlation was found.

4.2.2. Institutional drivers

4.2.2.1. Legal system

Institutional theory suggests that firms are part of complex contexts wherein there is coercive and normative pressure—namely, a legal system that dictates the ‘rules of the game’ [9,51]. Specifically, regarding sustainability, the country of origin and its political system is decisive as it impacts adoption [18,19], extension [20,41,[52], [53], [54]], and the quality of sustainability reporting [20,55]. As companies are deeply rooted in the political system of their country of origin, assumedly, they adopt the main characteristics of the political system to which they belong [19], consequently influencing their sustainability goals and performance [20]. Hence, analysing the legal system’s effect on the adoption of sustainability reporting is necessary.

La Porta et al. [56] claimed that the type of organisation can be identified by distinguishing between common law and civil law [57]. In civil law systems, the company is considered an important part of society, and they are expected to look beyond the simple achievement of profit towards the needs of all the stakeholders [9,40]. The goal is reducing information asymmetry and enlightening the stakeholders to ensure that they can evaluate the company’s performance [19,[58], [59], [60]]. On the contrary, in common law systems, the focus is on the shareholders, who are considered the main stakeholders and important players in influencing the decision-making process [9,61]. The primary objective is creating value for shareholders and maximise revenues. Therefore, the published information is primarily financial [19,40]. The classification of legal families is closely related to the different forms of capitalism, wherein a distinction is made between liberal market economies (LME) and coordinated market economies (CME). From this, it can be deduced that liberal economies are common law countries, while coordinated countries are civil law countries. In LMEs, corporate behaviour is associated with a form of government that is oriented towards ‘shareholder value’. By contrast, CMEs are less dependent on shareholders and are predominantly oriented towards stakeholders. To meet their requirements, they will, therefore, disseminate information other than financial information [12].

Given these considerations, the literature [9,19,20,40] has provided evidence that companies located in civil law countries with a stakeholder orientation exhibit a higher interest in publishing social and environmental reports, as well as adopting an external guarantee [40]. They aim to meet the needs of a larger group of stakeholders and are subject to more pressure from the membership system [20]. By contrast, companies in common law countries place a weaker emphasis on social issues, have a shareholder orientation, and, thus, will not be inclined to publish sustainability reports.

Another aspect highlighted by the literature in the legal field concerns the level of rigidity with which the rules are followed. Companies in countries wherein the legislation is extremely strictly followed will be directed to produce elaborative reports as the control systems are highly precise and meticulous in the face of pressure from the stakeholders. These findings contribute to institutional theory by demonstrating how external pressures influences organisations in their decisions to disclose information [9]. Moreover, in countries that support high levels of investor protection, fulfilling shareholders’ needs is essential. Consequently, sustainability information is traditionally less valued and summarised in traditional annual reports [19].

On the contrary, in countries emphasizing social needs, strong employment protection prevails, which is synonymous with attention to CSR and, consequently, the adoption of sustainability reporting. Based on these considerations, the literature suggests that companies in a country with strict investor protection laws are less likely to publish sustainability reports than companies in a country with strict labour protection laws. However, Jensen and Berg [19] and Rosati and Faria [20] refuted this hypothesis in empirical analyses through several considerations. First, according to Jensen and Berg’s [19] study, reporting was not driven by the market; hence, a stand-alone report would likely not attract stakeholder attention. Instead, an insertion into the typical annual report would be perceived. Additionally, Rosati and Faria [20] reported that companies most inclined to disclosing non-financial information were in countries with weaker OSH laws. This could put significant pressure on companies, which, in turn, forces them to be more proactive in voluntarily reporting on their labour practises and sustainable behaviour.

4.2.2.2. Economics and finance

-

•

Financial system

Financial systems can broadly be distinguished into primarily market-based and primarily bank-based economies, depending on their relation to market coordination. In bank-based economies, there is less market coordination, and banks are the main providers of financing, and also play the intermediary role between companies and investors. Considering their fundamental role, banks have direct access to the various data of the company, and they can monitor its performance [19]. Therefore, organisations are less motivated to disclose information to the public [20]. In market-based economies, market coordination is high, and companies are financially dependent on stakeholders rather than bank capital [19]. In this context, to promote and reach all stakeholders, companies are highly motivated to disclose both financial information and sustainability performance to shareholders [20]. These considerations amount to the hypothesis that companies in highly market-oriented countries are more likely to publish sustainability reports. However, Rosati and Faria [20] revealed that companies reporting on sustainable development goals are more likely to be located in countries with a lower market orientation, especially in banking countries. This finding may reflect banks’ growing commitment to helping organisations improve their sustainability performance and highlights their motivating role in promoting sustainable development.

-

•

Concentration of ownership

Additionally, studies by Jensen and Berg [19] and Rosati and Faria [20] found that the extent of ownership concentration in a company influences the form of sustainability reporting. In particular, companies disclose more information when they are located in countries with lower ownership concentration. This is because dominant owners do not rely on published information as they can obtain the desired information directly from the company and, therefore, have no interest in publishing additional or foreign reports.

-

•

Economical progress

The economic system is a relevant driver in sustainability reporting [19,62]. Jensen and Berg [19] and Fasan et al. [63] reported that countries with higher levels of economic development have more resources to invest in sustainability, as well as receive more public pressure; consequently, they would be inclined to disclose more information.

-

•

Economic freedom

Another important element is economic freedom, which, in interaction with other factors (culture), can positively impact the country’s sustainability performance [20,64]. It raises the level of sustainability reporting [19,63] by reducing incidents of corruption and thus encouraging companies to be more responsible.

4.2.2.3. Non-governmental organisation (NGO) collaborations

A further driver in the form of associations and collaborations with NGOs can influence sustainability reporting due to regulatory isomorphism [4]. Whereas companies perceive greater control and monitoring of their behaviour from an environmental perspective, ensuring the presence of NGOs is a mechanism to mobilise the activism of citizens, who consequently intensify the pressure on companies, especially on those creating environmental damage, thus increasing precise disclosure [65].

4.2.2.4. Cultural system

The cultural aspect of a country is fundamental to the extent that companies are perceived as integral and responsible parts of society. In some countries, national corporate responsibility limits the economic and financial aspects, whereas, in others, it also extends to cover social and environmental aspects [19]. Accordingly, this impacts the likelihood of companies acting more consciously and responsibly to disseminate genuine information on various issues, and to create a positive link between companies and the country by publishing sustainability reports [20].

Furthermore, the social development of a country can also play an important role in the environmental dimension [20,66]. Sustainable development comprises the following two aspects: human development and civic engagement. Both are closely related to sustainability issues, as they are positively correlated with economic growth [20,67], low corruption [20,68] and female labour force participation rates [20,21]. It is likely that organisations based in countries with high levels of human development and civic engagement will disclose additional information.

Another important factor concerns the national culture variable, whose impact is fundamental in CSR dissemination practices [28]. Hofstede et al. [69] proposed five specific cultural traits to highlight differences between countries and identify the relationship between a country's culture and reporting—namely, individualism vs. collectivism, masculinity vs. femininity, power distance, uncertainty and long-term orientation.

-

•

Individualism/collectivism

The individualism/collectivism dimension refers to the predominance of individual values over group values [28]. Thus, while members of an individualistic society take care of themselves and their families, citizens in a collectivistic society act with a view of taking responsibility for society as a whole [20,[70], [71], [72]]. García-Sánchez et al. [28] empirically analysed a sample of 1590 societies in 20 different countries. They found that in more individualistic cultures, members are less likely to engage with society, including issues of common good, sustainability and, ultimately, reporting.

-

•

Masculinity-femininity

The element of masculinity/femininity can be defined in terms of the presence and role women play in society. Men are traditionally oriented towards material and economic success, while women are more concerned about the quality of life [28].

-

•

Power distance

Power distance refers to the degree of hierarchy in society. A large power distance indicates that positions are vertically hierarchically stratified with different levels of power, and this implies less transparency and less meritocratic systems [20]. Individuals at lower levels have less power and even less interest in sustainability issues; in this context, only those positioned at the highest levels make decisions about sharing information with stakeholders. The greater the distance between levels, the more difficult it is to implement sustainability; however, the empirical study by García-Sánchez et al. [28]—on a sample of 1590 companies—demonstrated that this does not seem to be a predominant factor in the adoption of sustainability reporting.

-

•

Uncertainty

The uncertainty dimension occurs in unstructured situations when reality is both unfavourable and unknown. By ‘unstructured situations’, Hofstede [73] meant situations that are ‘new, unknown, surprising or different from usual’. Firms with a lower propensity to change and innovate have greater difficulty adapting to new sustainability demands and practises [20,74]. Consequently, the literature hypothesises that the relationship between uncertainty and sustainability is associated with more negative reporting [[74], [75], [76]]; however, no empirical evidence has yet been found to justify this hypothesis.

-

•

Long-term orientation

Long-term orientation involves a strong tendency to save and invest in thrift, and perseverance. On the contrary, parties with short-term orientation lack the propensity to save for the future. Instead, they aim to achieve immediate results. Since sustainability is a long-term goal, studies have hypothesised that long-term orientation is probably positively correlated with the stakeholder perspective and promoting social disclosure and sustainability reporting [28].

4.2.2.5. Technological system

Regarding the technology driver, the literature is not uniform. Several authors assume that companies in countries with high levels of technology and innovation, which have more financial resources and knowledge, are more likely to invest in sustainability and reporting [19,77,78]. Rosati and Faria [20] and Halkos and Skouloudis [79] reported in their studies that technology was not an important differentiating variable, as they did not find large differences in reporting purposes.

4.2.2.6. Education and work system

Another factor mentioned in the literature in relation to the institutional environment is the aspect of education and work. Several studies have found that individuals with higher levels of education are more CSR-oriented [19, 80]. This could be attributable to the fact that they are more aware and better informed. If this phenomenon is extended to the national level, the educational level and even investment in research or academic knowledge should be positively associated with sustainability and, consequently, with reporting. However, regarding the labour aspect, these vary by country. The presence of trade unions is an important element indicating that the country is interested in involving workers in decision-making and making progress. As the reports reflect the company and its values, they are more important in countries with a higher proportion of trade unions [20].

5. Discussion

The study intended to detect the existence and, consequently, evaluate the multi-theoretical framework of SR in the corporate system to understand the factors characterizing an optimal adoption to provide an overall perspective with respect to a fragmented literature. Moreover, the relevance of this study also lies in the significant sample of scientific papers carefully selected from a semantic perspective for an important period. The results of the analysis, that is a broad and complete picture of the observed drivers, bring out some interesting considerations emerged.

First, SR plays a central role in developing the ability to make internal and external stakeholders understand Company information. The sample of articles selected allowed us to cluster and highlight the so-called institutional and corporate categories. This division made it possible to draw a clear and comprehensive picture of both the internal and specific characteristics of business organisations and the elements of the environmental system. As mentioned above, SR, as a fundamental tool of reporting and communication, guarantees the satisfaction of stakeholders’ information needs and the maintenance of legitimacy in the institutional environment wherein the company finds itself [3,4,9,28].

Second, the amount of information that characterises institutional and corporate drivers can positively influence the effectiveness of internal and external communication for sustainability purposes. This particularity demonstrates that the value of information (both financial and non-financial) could encompass a large amount of data, as greater awareness and knowledge of internal and external dynamics leads to a shared value of information to predict measurable goals as well as flexible strategic changes. Moreover, this consideration highlights the strong dichotomy between the legal frame of reference and effective application of SR in the corporate sphere. Amran et al. [15], Fasan et al. [63], and Rosati and Faria [20] noted that adopting SR does not necessarily improve the quality of the information that it contains.

Although these results allow for a clear and complete picture of the SR drivers to be drawn, an empirical analysis is needed to better understand the value perceived by internal and external stakeholders of the individual factors. Such an analysis could make it possible to test the individual SR drivers’ responsiveness and effectiveness.

From a qualitative perspective, another line of research can examine the area of the SR quality, which is much discussed in the literature in the light of the distinction with the assumption of the SR, highlighting the factors that correspond to a higher or lower quality of the SR.

6. Conclusions

Our research demonstrates that in the last decade, the scientific community has been strongly interested in studying sustainability from different perspectives. This need is attributable to the interest of companies to increasingly address sustainability issues as part of their business strategies, which leads them to consider stakeholder relations as strategic. This consideration has been confirmed by the need to present a truthful, transparent, and factual image of the company to the economic system with which they interact. This phenomenon, though taken for granted, necessarily relates to the innovations introduced at the international level in the field of sustainable reporting and the consequent development of information that can be derived from standardised, harmonised and interpretable reporting systems. To this end, we found that SR is the link between financial and non-financial information and is the most appropriate tool for improving the company's internal and external communication on elements of an environmental, social, and ethical nature that were previously difficult to identify with traditional reporting systems. This study aimed at presenting a complete picture of the theories that form the basis of the SR that allowed the identification of the drivers influencing the adoption of the SR.

Clearly, the paradigm shift depends on the correct interpretation of the drivers necessary to anchor SR; this study underpins the division into ‘entrepreneurial drivers’ and ‘institutional drivers’. Accordingly, ‘entrepreneurial drivers’ are necessary to represent the concept of business continuity in the context of organisational characteristics. Simultaneously, ‘institutional drivers’ are necessary to verify the reliability of enterprises in relation to the context in which they operate. Classifying the drivers that emerged from the study enabled the definition of implementation gaps in using SR per the usual schemes of sustainability reporting, thus highlighting the diversity of drivers influencing adoption.

The study sheds light on the theoretical and practical implications that SR offers in terms of the research pathways defined by scholars in recent academic work.

From a theoretical point of view, the results obtained extend the line of research on the SR, focusing on the incentive factors of its adoption. Scholars agree that the SR has bidirectional approach. On the one hand, it sheds light on the complex relationship between corporate dynamics and the environment; on the other hand, it assesses the ability of companies to balance the heterogeneous needs of different stakeholders. Owing to its versatility, SR is essential to lend value to both internal and external relationships within the company, in terms of a broader concept of company performance than exclusive reporting. In this way, SR can satisfy stakeholders’ different information needs and is a tool of corporate legitimacy.

Notably, considering these developments, the current reporting processes will lay the foundation for the future paradigm shift in applying SR in the corporate system. Knowing the critical elements will enable the development of a novel perspective on the approach to corporate reporting that is more in line with the new ways of sustainability. Clearly, all elements useful for overcoming the limitations of corporate culture must be demonstrated in the reference context to fully understand SR’s effectiveness compared to traditional reporting models.

However, since any systematic review is inherently an interpretive process, it must be recognized as limited in the sense that there is no way to check other alternative interpretations of the reviewed articles. In addition, the search and analysis included articles published in English. In this sense, the author acknowledges that there may be other relevant articles in non-English journals which could have been lost. In addition, drivers affecting SR adoption without reference to SR quality were presented. Given the debate that the literature highlights on the arbitrary use of IR as a mere ‘boxes to tick’, future research can investigate the aspect of the quality of IR in relation to the phenomenon of ‘greenwashing’.

Future research can include testing the identified influencing factors in corporate contexts, thus allowing materiality tests to be conducted to clarify the use of IR as a certification tool for substantive rather than symbolic sustainability.

Author contribution statement

Marco Benvenuto: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Chiara Aufiero: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analysed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Carmine Viola: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analysed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Data availability statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.

Declaration of interest’s statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Marco Benvenuto, Email: marco.benvenuto@unisalento.it.

Chiara Aufiero, Email: chiara.aufiero@unisalento.it.

Carmine Viola, Email: carmine.viola@unisalento.it.

References

- 1.Kuzey C., Uyar A. 2017. Determinants of Sustainability Reporting and its Impact on Firm Value: Evidence from the Emerging Market of Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frías-Aceituno J.V., Rodríguez-Ariza L., Garcia-Sanchez I.M. The role of the board in the dissemination of integrated corporate social reporting. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag., vol. 20(4), pages 219-233, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deegan C., Rankin M., Tobin J. An examination of the corporate social and environmental disclosure of BHP from 1983–1997. Accounting. Audit. Accountabil. J. 2002;15(2):312–343. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amran A., Haniffa R. Evidence in development of sustainability reporting: a case of a developing country. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2011;20(3):141–156. doi: 10.1002/bse.672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez-Fernandez M. 2015. Social Responsibility and Financial Performance: the Role of Good Corporate Governance. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roe M.J. A political theory of American corporate finance. Columbia Law Rev. 1991;91:10e67. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roe M.J. Princeton University Press; NJ/Princeton: 1994. Strong Managers, Weak Owners: the Political Roots of American Corporate Finance. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell J.L. Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007;32(3):946e967. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frías-Aceituno J.V., Rodríguez-Ariza L., García-Sánchez I.M. Is integrated reporting determined by a country’s legal system? An exploratory study. J. Clean. Prod. 2013;44:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frías-Aceituno J.V., Rodríguez-Ariza L., Garcia-Sánchez I.M. Explanatory factors of integrated sustainability and financial reporting. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2012;23(1):56–72. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lock I., Seele P. The credibility of CSR (corporate social responsibility) reports in Europe. Evidence from a quantitative content analysis in 11 countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2016;122:186–200. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehnert I., Parsa S., Roper I., Wagner M., Muller-Camen M. Reporting on sustainability and HRM: a comparative study of sustainability reporting practices by the world’s largest companies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016;27(1):88–108. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez-Feijoo B., Romero S., Ruiz S. Effect of stakeholders' pressure on transparency of sustainability reports within the GRI framework. J. Bus. Ethics. 2014;122:53–63. doi: 10.1007/s10551-013-1748-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amran A., Lee S.P., Devi S.S. The influence of governance structure and strategic corporate social responsibility toward sustainability reporting quality. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2014;23:217–235. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez-Feijoo B., Romero S., Ruiz-Blanco S. Women on boards: do they affect sustainability reporting? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014;21(6):351–364. doi: 10.1002/csr.1329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuente J.A., García-Sánchez I.M., Lozano M.B. The role of the board of directors in the adoption of GRI guidelines for the disclosure of CSR information. J. Clean. Prod. 2017;141:737–750. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.09.155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buhr N., Freedman M. Culture, institutional factors and differences in environmental disclosure between Canada and the United States. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2001;12:293e322. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen J.C., Berg N. Determinants of traditional sustainability reporting versus integrated reporting. An institutionalist approach. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2012;21(5):299–316. doi: 10.1002/bse.740. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosati F., Faria L.G.D. Addressing the SDGs in sustainability reports: the relationship with institutional factors. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;215:1312–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naidu S. Does human development influence women's labor force participation rate? Evidences from the Fiji islands. Soc. Indicat. Res. 2016;127:1067e1084. doi: 10.1007/s11205-015-1000-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moher D., Shamseer L., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati M., Petticrew M. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372(71) doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burnham J. Scopus database: a review. Biomed. Digit Libr. 2006;3:1. doi: 10.1186/1742-5581-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Likert R. Technique for the measure of attitudes. Arch. Psychol. 1932;22(140):55. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cormier D., Magnan M., Van Velthoven B. Environmental disclosure quality in large German companies: economic incentives, public pressures or institutional conditions? Eur. Account. Rev. 2005;14(1):3e39. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braam G.J.M., Uit De Weerd L., Hauck M., Huijbregts M.A.J. Determinants of corporate environmental reporting: the importance of environmental performance and assurance. J. Clean. Prod. 2016;129:724–734. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.03.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.García-Sánchez I.M., Rodríguez-Ariza L., Frías-Aceituno J.V. The cultural system and integrated reporting. Int. Bus. Rev. 2013;22(5):828–838. doi: 10.1016/j.ibusrev.2013.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gray R.H., Owen D.L., Adams C.A. Prentice-Hall; Hemel Hempstead, UK: 1996. Accounting and Accountability: Changes and Challenges in Corporate Social and Environmental Reporting. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deegan C., Unerman J. European edn. McGraw-Hill; Maidenhead, UK: 2006. Financial Accounting Theory. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dillard J., Rigsby J., Goodman C. The making and remaking of organization context, duality and the institutionalization process. Account Audit. Account. J. 2004;17(4):506–542. [Google Scholar]

- 31.DiMaggio P.J., Powell W.W. The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983;48:146–160. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Unerman J., Bennett M. Increased stakeholder dialogue and the internet: towards greater corporate accountability or reinforcing capitalist hegemony? Account. Org. Soc. 2004;29(7):685–707. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verrecchia R.E. Discretionary disclosure. J. Account. 1983;5 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Healy P.M., Palepu K.G. Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: a review of the empirical disclosure literature. J. Account. And with. 2001;31(1):405e440. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baiman S., Verrecchia R. The relation among capital markets, financial disclosure, production efficiency, and insider trading. J. Account. Spring. 1996:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hahn R., Reimsbach D., Kotzian P., Feder M., Weißenberger B.E. Legitimation strategies as valuable signals in nonfinancial reporting? Effects on investor decision-making. Bus. Soc. 2021;60(4) doi: 10.1177/0007650319872495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfeffer J. Size, composition and function of hospital boards of directors: a study of organization-environment linkage. Adm. Sci. Q. 1973;18(3):349–364. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfeffer J., Salancik G.R. Harper and Row; New York: 1978. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kolk A., Perego P. Determinants of the adoption of sustainability assurance statements: an international investigation. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2010;19(3):182–198. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1284589 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prado-Lorenzo J.M., García-Sanchez I.M. The role of the board of directors in disseminating relevant information on greenhouse gases. J. Bus. Ethics. 2010;97:391e424. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lakhal F. Voluntary earnings disclosures and corporate governance: evidence from France. Rev. Account. Finance. 2005;4(3):64–85. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fama E.F., Jensen M.C. Separation of ownership and control. J. Law Econ. 1983;27:301–325. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agrawal A., Knoeber C. Firm performance and mechanisms to control agency problems between managers and shareholders. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 1996;31:377–397. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Betz M., O'Connel L., Shepard J.M. Gender differences in proclivity for unethical behavior. J. Bus. Ethics. 1989;8:321–324. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adams R.B., Ferreira D. 2004. Gender Diversity in the Boardroom. ECGI. Finance Working Paper (57) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lipton M., Lorsch J.W. A modest proposal for improved corporate governance. Bus. Lawyer. 1992;48(1):59–77. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fernandez J.L., Luna Sotorrio L.L., Baraibar Díez E. The relation between corporate governance and corporate social behavior: a structural equation model analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011;18(2):91e101. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pava M.L. Why corporations should not abandon social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics. 2008;83(4):805–812. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Surroca J., Tribo J.A., Waddock S. Corporate responsibility and financial performance: the role of intangible resources. Strat. Manag. J. 2010;31:463–490. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campbell J.L. Institutional analysis and the paradox of corporate social responsibility. Am. Behav. Sci. 2006;49(7):925e938. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen S., Bouvain P. Is corporate responsibility converging? a comparison of corporate responsibility reporting in the USA, UK, Australia, and Germany. J. Bus. Ethics. 2009;87:299e317. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fortanier F., Kolk A., Pinkse J. Harmonization in CSR reporting: MNEs and global CSR standards. Manag. Int. Rev. 2011;51:665e696. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hahn R., Kühnen M. Determinants of sustainability reporting: a review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research. J. Clean. Prod. 2013;59:5e21. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vormedal I.H., Ruud A. Sustainability reporting in Norway - an assessment of performance in the context of legal demands and socio-political drivers. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2009;18:207e222. [Google Scholar]

- 55.La Porta R., Lopez-de- Silanes F., Shleifer A., Vishny R. Legal determinants of external finance. J. Finance. 1997;52:1131e1150. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berle A.A., Means G.C. Macmillan; New York: 1932. The Modern Corporation and Private Property. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jensen M.C., Meckling W.H. Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976;3:305–360. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ball R., Kothari S.P., Robin A. The effect of international institutional factors on properties of accounting earnings. J. Account. Econ. 2000;29:1–51. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Prado-Lorenzo J., Rodríguez-Domínguez L., Gallego-Alvarez I., García-Sanchez I.M. Factors influencing the disclosure of greenhouse gas emissions in companies world-wide. Manag. Decis. 2009;47:1133e1157. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Neumayer E., Perkins R. What explains the uneven take-up of ISO 14001 at the global level? A panel-data analysis. Environ. Plann. 2004;36:823–839. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fasan M., Marcon C., Mio C. In: Integrated Reporting: a New Accounting Disclosure. Mio C., editor. 2016. Institutional determinants of IR disclosure quality; p. 181e203. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roy A., Goll I. Predictors of various facets of sustainability of nations: the role of cultural and economic factors. Int. Bus. Rev. 2014;23:849e861. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marquis C., Toffel M.W., Zhou Y. Scrutiny, norms, and selective disclosure: a global study of greenwashing. Organ. Sci. 2016;27(2) doi: 10.1287/orsc.2015.1039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Salim E. In: Managing the Transition to a Low-Carbon Economy: Perspectives, Policies, and Practices from Asia. Anbumozhi V., Kawai M., Lohani B.N., editors. Asian Development Bank Institute; Tokyo, Japan: 2015. Pro-growth, pro-job, pro-poor, pro-environment; p. 391. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Albassam B. The relationship between governance and economic growth during times of crisis. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2013;2:1e18. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sims R.L., Gong B., Ruppel C.P. A contingency theory of corruption: the effect of human development and national culture. Soc. Sci. J. 2012;49:90e97. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hofstede G., Hofstede G.J., Minkov M. 2010. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fernandez-Feijoo B., Romera S., Ruiz S. Does board gender composition affect corporate social responsibility reporting? Int. J. Business - ness Social Sci. 2012;3:31e39. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Park H., Russell C., Lee J. National culture and environmental sustainability: a cross-national analysis. J. Econ. Finance. 2007;31:104e121. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Williams G., Zinkin J. The effect of culture on consumers' willingness to punish irresponsible corporate behavior: applying Hofstede's typology to the punishment aspect of corporate social responsibility. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2008;17:210e226. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hofstede G. Sage Publications; London (UK): 2001. Culture's Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ringov D., Zollo M. Corporate responsibility from a socio-institutional perspective: the impact of national culture on corporate social performance. Corp. Govern. 2007;7:476e485. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Husted B. Culture and ecology: a cross-national study of the determinants of environmental sustainability. Manag. Int. Rev. 2005;45:349e371. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vachon S. International operations and sustainable development: should national culture matter? Sustain. Dev. 2010;18:350e361. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bansal P. Evolving sustainably: a longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strat. Manag. J. 2005;26 [Google Scholar]

- 76.McWilliams A., Siegel D. Corporate social responsibility: a theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001;26:117e127. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Halkos G., Skouloudis A. Corporate social responsibility and innovative capacity: intersection in a macro-level perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2018;182:291–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kelley S.W., Donnelly J.H., Skinner S.J. Customer participation in service production and delivery. J. Retailing. 1990;63:315e335. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.