Abstract

This observational descriptive study that was carried out with the objective of exploring the contribution of the local pharmaceutical industry to the Saudi drug security. Using a drug formulary provided from the Saudi Food and Drug Authority, containing all registered pharmaceutical products available in Saudi Arabia, we extracted information about drug class, drug type, country and place of manufacturing, shelf-life and price. Results showed that the majority of drugs in the market are manufactured in Europe (43.86%), followed by Saudi Arabia (22.55%), China and India (20.47%), Americas (10.24%), and other nations (2.61%). Most of the manufactured drugs were prescription drugs (90.62%). In this work, the local pharmaceutical industry with the highest percentage of contribution to local drug security was Pharmaceutical Solution Industries (PSI), representing the 5% of the items available in the Saudi market. The second highest percentage was 4% by TABUK Pharmaceutical Manufacturing CO., followed by SPIMACO (3%), JAMJOOM pharmaceutical company (2%), Riyadh pharma (2%), and Jazeera pharmaceutical industries (2%). In addition, results from this study provide information about the most essential pharmaceutical products that needs to be nationally manufactured or increased in production in order to rise the contribution of local pharmaceutical industries in Saudi drug security. Unfortunately, the small contribution of the Saudi pharmaceutical industry in local drug security increases the burden on the Kingdom's annual budget due to the over-reliance on international pharmaceuticals.

Keywords: Pharmaceutical manufacturing, Drug security, Drug administration, Drug Classification

1. Introduction

The pharmaceutical industry is a multi-billion-dollar global industry that has a significant economic impact and plays a major role in human health and wellbeing. Indeed, pharmaceutical industries seek to develop and improve products to increase the quality of human life (Taylor, 2015). They are engaged in the discovery, manufacturing, and marketing of drugs, vaccines, biologics, and medical devices (Liang & Yuan, 2020). Nowadays, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) spends around 20% of the total health expenditure on pharmaceuticals. The development of chronic diseases and the high expense of producing medications like vaccines, antibiotics, and anticancer therapies are the main factors contributing to this rise (Assad, 2007, Vasisht et al., 2016, Tawfik et al., 2022). An important challenge for any pharmaceutical company is to sustain a continuous manufacture of pharmaceuticals to meet all health needs. For that, almost every country seeks to localize the drug ingredients and their manufacturing on its land (Jaberidoost et al., 2013, Alrasheedy, 2020). In the KSA, more than 40 registered pharmaceutical industries cover only 20–25% of the total pharmaceutical consumption of dispensed medicines (Assad, 2007, Vasisht et al., 2016, Tawfik et al., 2022).

Over the years, humans obtained their medicines from the nature, beginning with using crude herbs, then using the different herbal preparations, which later escalated to the pharmaceutical industry revolution era (Verma and Singh, 2008, Al-Aqeel et al., 2010). At this time, humans are able to obtain their medicine through more complex and sophisticated pharmaceutical manufacturing, providing different products and dosage forms (Alzahrani and Harris, 2021). The pharmaceutical sector uses a variety of procedures, including those for medication development, production, and marketing. Without a question, the pharmaceutical business is a fundamental pillar of any healthcare system and plays a crucial role in assisting patients and communities (Vasisht et al., 2016, Alsaddique, 2017). With the increasing prevalence diseases and health conditions among the KSA population, the country has established the largest pharmaceutical market in the Arab region (Alruthia et al., 2018). Recently, drug spending in the KSA has risen by an average of 20% of the total health expenditures. The prevalence of chronic diseases and the risk factors linked to them, as well as the high cost of producing therapies like vaccinations, antibiotics, and cancer treatments, are blamed for this rise (Assad, 2007, Vasisht et al., 2016, Alzahrani and Harris, 2021).

From 14 billion Saudi Riyal (SAR) in 2012 to 28 billion SAR in 2016 and 40 billion SAR in 2023, the size of the KSA pharmaceutical market is anticipated to increase. The Kingdom's annual budget may be considered to be burdened by this market size. By the end of 2021, it is anticipated that the Kingdom will sell more drugs than 30 billion SARs annually, making up about 25% of all medication sales in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) areas (The Report, 2018). As of 2022, the KSA government pays healthcare costs for almost all Saudis. Medication costs represents almost 44% of the total cost value of the healthcare process in the KSA (Tawfik et al., 2022). Despite the large local pharmaceutical market, the KSA still relies on international pharmaceutical markets, importing approximately 70% of its medication products from Europe, China, India, and USA combined. Only about 30% of the total KSA pharmaceuticals market are produced locally, with a small portion of branded drug production (Alrasheedy, 2020, Alzahrani and Harris, 2021). Previous studies suggest that the number of registered pharmaceutical industries in the KSA exceeds 40, yet only cover 20–25% of the Kingdom’s consumption of dispensed medicines. One of the most vital challenges in the pharmaceutical industry and healthcare system is to maintain the continuous supply of the different pharmaceutical products to meet the increasing demand (Festa et al., 2022).

As in many countries around the world, one of the major problem areas in the KSA healthcare system is the shortage in continuous pharmaceutical supply chain. Alruthia and colleagues defined the root causes for medication shortage in the KSA (Alruthia et al., 2018). These included low profit margins for some necessary medications, poor management of the medication supply chain, a lack of government drug shortage detection, a lack of government policy that kept up with changes in the pharmaceutical market, weak and ineffective local businesses that couldn't compete with other imported pharmaceutical products (Alkhenizan, 2014, Sultana, 2016). Local drug security can be defined as a measurement that is used to ensure that the quality of drug production is safe and with great efficacy level, and is produced according to the local regulatory agency such as Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA) standards, securing that production is covering almost all the therapeutic categories of medication like vaccines and chemotherapeutic agents (Shukar et al., 2021). Global drug security is used to define the product using the global regulatory guidelines (Finelli and Narasimhan, 2020, Hotez et al., 2021, Shafiq et al., 2021). Indeed, localizing our pharmaceutical industry is a must due to having a constant growth in the patient population and increase the need for healthcare services, especially for people with persistent illnesses like Alzheimer‘s, Dementia, and MS (Shukar et al., 2021). Indeed, the importance of localizing pharmaceutical industries in Saudi Arabia lies in many aspects, which we can extract from several advantages, first, to achieve drug security in KSA. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the localization and local manufacture of medicine to achieve self-sufficiency, which has a direct impact on the side of national security and medicine. On the other hand, reliance on imported pharmaceuticals to secure medicines entails many risks associated with global crises, which may affect the pharmaceutical supply in these crises. Second, the increasing demand for medicine, especially with what the Kingdom is going through during this pandemic (COVID 19), as well as the expansion of health services, the continuous increase in the population, the development of cities and the increase in the number of hospitals, health centers and private pharmacies. Third, the expansion of the production base and the diversification of sources of income. Fourth, to be able to increase the percentage of the industrial sector in the non-oil of Saudi Arabia, and also to be able to achieve the vision of expanding production through various development plans. Fifth, the localization of the pharmaceutical industry does not depend on pharmaceutical production only, while there will be several fields related to it, for example marketing, selling and exporting through various and multiple outlets, which will provide more job opportunities in the field of pharmacy for our graduating students (Rahman and Salam, 2021, Sarkis et al., 2021). Due to widespread medication use and insufficient local drug manufacturing, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused severe disruptions in global supply chains in many industries, including the pharmaceutical industry, putting many people's lives in danger. As a result, access to medications and the pharmaceutical supply chain have become problematic globally (Al-Jazairi et al., 2011, Khan et al., 2016). Expanding the level of limitation of the drug manufacturing in KSA is fundamental to safeguard the country's medical care framework and upgrade the Kingdom's readiness for arising episodes of past COVID-19 (Shuman et al., 2020, Badreldin and Atallah, 2021). Due to the fierce competition for medications globally, relying too heavily on importing international drugs to make up for drug shortages rather than producing them locally can seriously jeopardize the drug supply chain. By localizing pharmaceutical manufacturing, however, it is possible to provide drugs in the right quantity and at reasonable costs while reducing the likelihood of supply disruptions during times of crisis (Badreldin and Atallah, 2021). The Saudi Industrial Development Fund is crucial in ensuring that the industrial sector realizes the Kingdom's vision and substantially boosts the country's overall economy. Financial support encourages pharmaceutical companies and research institutes to coordinate a plan for successful drug innovations to enhance the localization of drug makers in the Kingdom and achieve drug security. The industrial fund for pharmaceutical industries can support the pharmaceutical industries at all levels, as the fund has supported industries to deal with the impact of the COVID 19 pandemic (Webb et al., 2022). Through 2030 vision, The National Transformation Program (NTP), KSA looks forward to increase the overall health care outcomes to meet the needs and prevent such shortage and provide a continuous pharmaceutical supply chain. To achieve this goal, 2030 vision is aiming to raise such local medicine production to 40% minimum. With the vision of 2030 and its short objectives specified in the NTP, a significant improvement is booked to happen towards endlessly prescriptions created locally (The Report, 2018). The NTP recognizes the creation and improvement of drugs as an essential objective that features the expansion in the local rate in the area to 40% relatively soon, and the Ministry of Health is the fundamental exhibition pointer for this (The Report, 2018). By considering these aspects, the pharmaceutical industries will be developed enormously in the KSA in next decades.

This study aimed to explore the contribution of localized pharmaceutical industries in KSA drug security. We also aimed to describe the distribution of local pharmaceuticals in the KSA, based on drug type, drug class, prescription requirement, place of manufacturing, and price. Furthermore, we compared these drug characteristics between locally and internationally manufactured medicines that are available in the Saudi market.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study setting and design

The current descriptive retrospective study was conducted at College of Pharmacy, Al-Maarefa University, KSA. Data were retrieved from SFDA drug formulary, which contained all the registered drug items in the Saudi market, including both locally manufactured and imported drugs. The lists represented drugs available from 2010 to 2019. This document contained 9457 items of registered pharmaceuticals.

2.2. Study measures

From the SFDA lists we collected information about the generic and trade name of the drug, the registration number, the year of registration, the drug class, the generic drug type, the concentration of the drug, the price of the drug in Saudi Riyals (SAR), and the name and place of manufacturing company, the pharmaceutical form, the method of use, and also the size, size unit, and type of packaging. The method of disbursement (whether it is a prescription or over the counter drug), and product control were also collected.

2.3. Statistical analysis

We calculated frequencies of the drug characteristics, for which we present counts and percentages. We also calculated the means and standard deviations (sd) for shelf-life and medication costs. Furthermore, we compared the characteristics of the drugs by region of manufacturing (nationally vs. internationally) using chi-square tests and student t-tests. The p level of < 0.05 was used to test for statistical significance. Data were analyzed using “SPSS (IBM. SPSS statistics for Windows. Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM; 2012)”.

2.4. Ethical considerations

Al Maarefa University's Institutional Review Board (IRB) provided the ethical approval.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Contribution of Saudi pharmaceutical companies in Saudi Arabia in local drug security

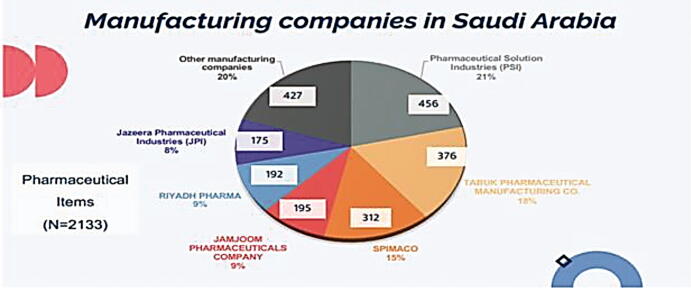

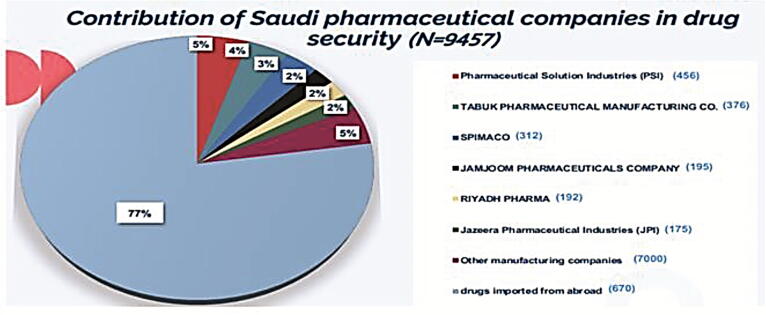

Fig. 1 illustrates the percentages of pharmaceutical items manufactured by each Saudi pharmaceutical company (N = 2133). In this work, the highest percentage of pharmaceutical items was manufactured by Pharmaceutical Solution Industries (PSI) representing 21% of Saudi manufactured pharmaceutical items, followed by TABUK Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Co. (18%), SPIMACO (15%), JAMJOOM pharmaceutical company (9%), Riyadh pharma (9%), Jazeera Pharmaceutical Industries (JPI) (8%), and 20% by remaining manufacturers. Fig. 2 illustrates the contribution of Saudi pharmaceutical companies in Saudi Arabia in local drug security (N = 9457). In this work, the local pharmaceutical industry with the highest percentage of contribution to local drug security was PSI, representing 5% of Saudi manufactured pharmaceutical items followed by TABUK Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Co. (4%), SPIMACO (3%), JAMJOOM Pharmaceutical company (2%), Riyadh pharma (2%), JPI (2%), and remaining 82% items were imported.

Fig. 1.

Saudi pharmaceutical companies in Saudi Arabia.

Fig. 2.

Contribution of Saudi pharmaceutical companies in drug security.

3.2. Cities in the Kingdom in which drug manufacturing is conducted

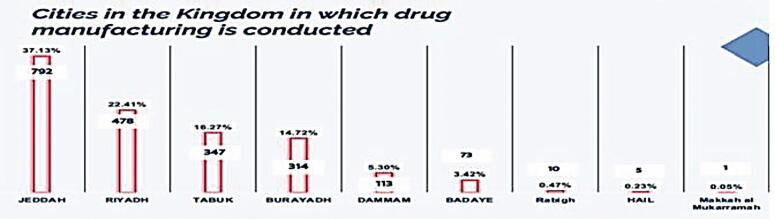

Fig. 3 illustrates the cities in the Kingdom in which manufacturing is conducted. In this section, we have discovered the percentage of cities in the Kingdom in which the local drug manufacturing is conducted. From the data we analyzed, it was observed the highest percentage of Saudi pharmaceutical companies where found in Jeddah (37.13%) followed by Riyadh (22.41%), Tabuk (16.27%), Buraydah (14.72%), Dammam (5.3%), Badaye (3.42%), Rabigh (0.47%), Hail (0.23%), and Makkah (0.05%).

Fig. 3.

Cities in the Kingdom in which drug manufacturing is conducted.

3.3. Characteristics of registered pharmaceutical products available in SFDA formulary

Table 1 describes the characteristics of all the registered pharmaceutical products in Saudi Arabia according to the SFDA formulary. Most of the registered products are generic and new chemical entity (NCE) drugs, where biological drugs and radiopharmaceuticals represent only 7.16% and 0.02%, respectively (N = 9457). Also, it is found that over the counter medications represent 10.9% of all registered items, and the total controlled drugs registered in SFDA is found to be 2.64% of all products. Saudi pharmaceutical companies are manufacturing 2133 pharmaceutical products. It composes 22.55% of drugs sold in the Saudi pharmaceutical market. When each country is looked at individually as a percentage of contribution to the Saudi market, the contribution from Saudi pharmaceutical companies is not enough to reach the local drug security. The highest percentage of contribution from a single country is from Saudi Arabia (22.55%), followed by Germany (8.48%), and Jordan (8.48%). Furthermore, among Arab nations that import drugs to the Saudi market, the most frequent were Jordan (8.48%), followed by the United Arab Emirates (4.48%), and Egypt (1.83%). Among countries outside the Arab nations, the most frequent were imported from Germany (8.48%), followed by the United States (7.45%), France (5.18%), the United Kingdom (4.97%) and Switzerland (4.58%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of registered pharmaceutical products available in FDA formulary.

| Characteristics | N = 9457 Count (%) |

|---|---|

| Drug type | |

| Biological | 677 (7.16%) |

| Generic | 5386 (56.98%) |

| Health | 4 (0.04%) |

| NCE | 3383 (35.79%) |

| Radiopharmaceutical | 2 (0.02%) |

| Legal status | |

| Over-the-counter | 1031 (10.90%) |

| Prescription | 8426 (89.10%) |

| Product control | |

| Controlled | 250 (2.64%) |

| Uncontrolled | 9207 (97.36%) |

| Country of manufacturing | |

| Arab Nations | |

| Saudi Arabia | 2133 (22.55%) |

| Jordan | 802 (8.48%) |

| United Arab Emirates | 424 (4.48%) |

| Egypt | 173 (1.83%) |

| Kuwait | 71 (0.75%) |

| Lebanon | 19 (0.20%) |

| Oman | 98 (1.04%) |

| Qatar | 81 (0.86%) |

| Syria | 20 (0.21%) |

| Tunisia | 15 (0.16%) |

| Yemen | 13 (0.14%) |

| Morocco | 11 (0.12%) |

| Other nations* | 5597 (59.18%) |

| The Americas | 968 (10.24%) |

| Europe | 4148 (43.86%) |

| Africa | 201 (2.13%) |

| Oceania | 2 (0.02%) |

| Australia | 69 (0.73%) |

| Asia | 1936 (20.47%) |

We have also determined the percentages of imported pharmaceutical items from each continent. The highest percentage of international drugs were imported from Europe, representing 43.86% of all imported items, followed by Asia (20.47%), Americas (10.24%), Africa (2.13%), Australia (0.73%) and Oceania (0.02%) of all imported pharmaceutical products.

3.4. Comparing the characteristics of national pharmaceutical products to medicine from abroad

In our country, experts are concerned that the nation relies far too much on medicine from abroad. In this study, we used the SFDA drug formulary to analyze all the registered pharmaceutical products to estimate the type of drugs, dosage forms, route of administrations, and packaging products, Saudi pharmaceutical companies focused on their production. The same analysis was done for pharmaceutical items from abroad. This was done to explain the small percentage of Saudi pharmaceutical companies to contribute to the local drug security. To achieve this objective, we have compared the count of drugs manufactured in Saudi Arabia (N = 2133) to those manufactured abroad (N = 7324) in each drug classification. Table 2 describes the comparison of drug type, legal status, product control, shelf life, and public prices of locally and internationally manufactured drugs. After analyzing the data, it was found that only 6 biological drugs are manufactured in Saudi Arabia which composed 0.33% of the total Saudi manufactured drugs (N = 2133). In fact, the number of biological drugs imported from abroad are 670 drugs and the p-value showed a significant difference between these groups (p < 0.0001). Also, the data showed that two radiopharmaceuticals are imported from other countries while the Saudi pharmaceutical companies are not manufacturing any radiopharmaceuticals (p < 0.0001). Moreover, 6643 chemical drugs are imported from abroad and only 2127 chemical drugs are manufactured in Saudi Arabia. Furthermore, OTC medications manufactured in Saudi Arabia are found to be 200 drugs representing 9.38% of the total local drugs, where the OTC medications imported from outside the country were 831 representing 11.35% of total imported drugs (p = 0.01). Also, we have counted the Saudi manufactured controlled drugs which was found to be 47 drugs representing 2.2% of total Saudi drugs. On the other hand, 203 controlled drugs were imported from outside the country representing 2.77% of imported drugs (p = 0.15). The average shelf life of Saudi manufactured drugs and imported drugs where calculated and found to be 30.35 and 31.7 months, respectively (p < 0.0001). In addition, the average public price of Saudi manufactured drugs and imported drugs was calculated in SAR and found to be 77.08 and 714 SAR, respectively. A significant difference was shown between these two groups (p < 0.0001). The total price of drugs manufactured in Saudi Arabia was SAR 164,411.57, while the total price for drugs manufactured internationally was SAR 5,229,880.92. This explains the heavy burden on the Kingdom's annual budget as a result of the overdependence on medicine from abroad.

Table 2.

Characteristics of locally and internationally pharmaceutical products available in FDA formulary (p-values were calculated by comparing the categorical estimates between the two groups using a chi-square test, and comparing the mean for shelf-life and public price of drug between the two groups using independent t-test).

| Characteristics | Locally manufactured N = 2133 Count (%) |

Internationally manufactured N = 7324 Count (%) |

p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug type | |||

| Biological | 6 (0.33%) | 670 (9.15%) | |

| Generic | 1905 (89.31%) | 3481 (47.56%) | |

| Health | 0 | 4 (0.05%) | <0.0001 |

| NCE | 221 (10.36%) | 3162 (43.20%) | |

| Radiopharmaceutical | 0 | 2 (0.03%) | |

| Legal status | |||

| Over-the-counter | 200 (9.38%) | 831 (11.35%) | 0.01 |

| Prescription | 1933 (90.62%) | 6493 (88.65%) | |

| Product control | |||

| Controlled | 47 (2.20%) | 203 (2.77%) | 0.15 |

| Uncontrolled | 2086 (97.80%) | 7121 (97.23%) | |

| Shelf-life in months, mean (sd) | 30.35 (9.45) | 31.70 (9.36) | <0.0001 |

| Public price for drug in SAR, mean (SD)** | 77.08 (282.5) | 714 (3650.5) | <0.0001 |

3.5. Comparing pharmacological classes of local pharmaceutical products to pharmacological classes of medicine from abroad

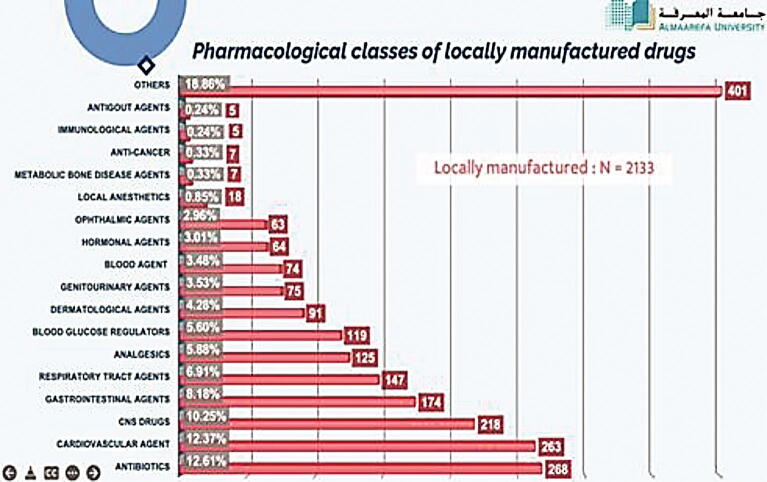

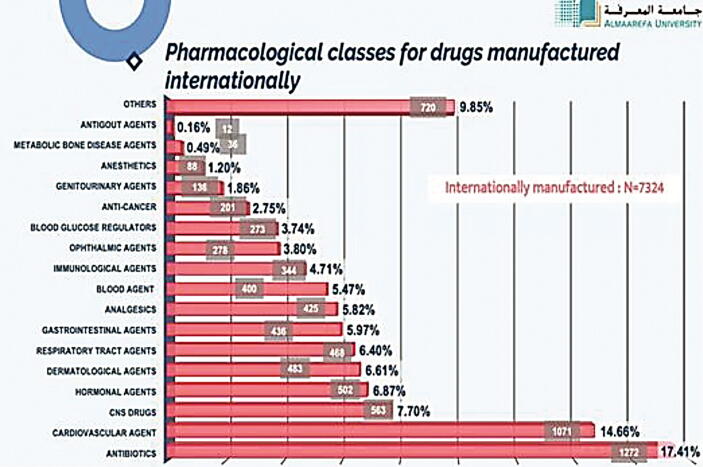

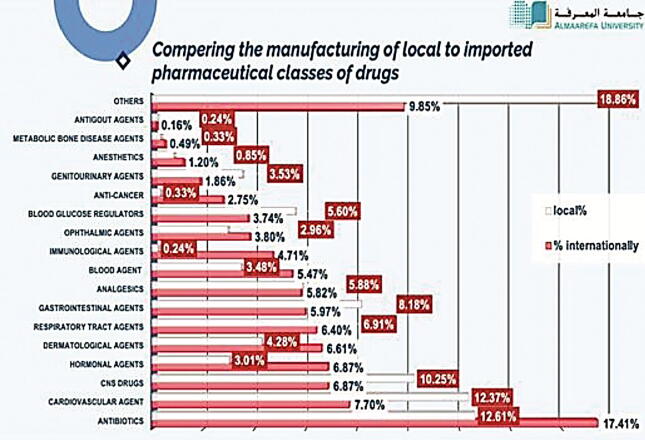

In this part, we have analyzed all the pharmacological classes of registered drugs using SFDA drug formulary. This was done to estimate what pharmacological classes Saudi pharmaceutical companies focused on their production, and as well, the most pharmacological classes that are imported from abroad. The results obtained from this work will give to us clear vision on the most pharmacological classes needed to be manufactured in Saudi Arabia to encourage Saudi pharmaceutical companies to fulfill the local needs and increase their contribution in Saudi drug security. Table 3 demonstrate the percentage of each pharmacological class of drugs manufactured in the Kingdom (N = 2133). It is found that the highest percentage of manufacturing is for antibiotics, representing 12.61% of locally manufactured drugs (Fig. 4), followed by cardiovascular drugs (12.37%), CNS drugs (10.25%), gastrointestinal drugs (8.18%), respiratory tract agents (6.91%), analgesics (5.88%), blood glucose regulators (5.60%), dermatological agents (4.28%), genitourinary agents (3.53%), blood agents (3.48%), hormonal agents (3.01%), ophthalmic agents (2.96%), local anesthetics (0.85%), metabolic bone disease agents (0.33%), anticancer agents (0.33%), immunological agents (0.24%), antigout agents (0.24%), and others (18.86%). Moreover, we have determined the percentages of pharmacological classes of drugs imported from abroad (N = 7324) (Table 4). Table 5 presents the comparative data of manufacturing of locally manufactured pharmacological classes of drugs with those of internationally manufactured. We have estimated that antibiotics have the highest percentage of imported drugs (11.76%) followed by dermatological agents, cardiovascular agents, and analgesics which composes 6.59%, 5.98% and 5.97% of total imported drugs (Fig. 5, Fig. 6).

Table 3.

Pharmacological classes of locally manufactured drugs.

| Pharmacological classes of locally manufactured drugs | % |

|---|---|

| Antibiotics | 12.61% |

| Cardiovascular agent | 12.37% |

| CNS drugs | 10.25% |

| Gastrointestinal agents | 8.18% |

| Respiratory tract agents | 6.91% |

| Analgesics | 5.88% |

| Blood glucose regulators | 5.60% |

| Dermatological agents | 4.28% |

| Genitourinary agents | 3.53% |

| Blood agent | 3.48% |

| Hormonal Agents | 3.01% |

| Ophthalmic agents | 2.96% |

| Local anesthetics | 0.85% |

| Metabolic bone disease agents | 0.33% |

| Anti-cancer | 0.33% |

| Immunological agents | 0.24% |

| Antigout agents | 0.24% |

| Others | 18.86% |

Fig. 4.

Pharmacological classes of locally manufactured drugs.

Table 4.

Pharmacological classes of drugs imported from abroad.

| Pharmacological classes for drugs manufactured internationally | % |

|---|---|

| Antibiotics | 11.76% |

| Dermatological Agents | 6.59% |

| Cardiovascular agents | 5.98% |

| Analgesics | 5.97% |

| Gastrointestinal Agents | 5.65% |

| Blood products | 5.45% |

| Respiratory tract agents | 5.41% |

| Electrolytes/minerals/vitamins | 5.05% |

| Antidiabetic agents | 4.72% |

| Immune agent | 4.70% |

| Ophthalmic agent | 3.66% |

| Hormonal agents | 3.55% |

| Antipsychotics | 3.04% |

| Antihistamines | 2.51% |

| Dyslipidemics | 1.45% |

| Anesthetics, sedatives, hypnotics | 1.35% |

| Antifungals | 1.31% |

| Anti-inflammatories, glucocorticoids | 1.28% |

| Genitourinary agents | 1.23% |

| Antidepressants | 1.16% |

| Antivirals | 1% |

| Anticonvulsants | 0.96% |

| Antiparkinson agents | 0.81% |

| Anthelmintics, antiprotozoals | 0.52% |

| Antidementia | 0.41% |

| Antithyroid agents | 0.14% |

| Others | 14.35% |

Table 5.

Comparing the manufacturing of local to imported pharmaceutical classes of drugs.

| Pharma class for drugs manufactured internationally | Internationally | Internationally (%) | Local | Local (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics | 1272 | 17.41 | 268 | 12.61 |

| Cardiovascular agent | 1071 | 7.70 | 263 | 12.37 |

| CNS drugs | 563 | 6.87 | 218 | 10.25 |

| Hormonal agents | 502 | 6.87 | 64 | 3.01 |

| Dermatological agents | 483 | 6.61 | 91 | 4.28 |

| Respiratory tract agents | 468 | 6.40 | 147 | 6.91 |

| Gastrointestinal agents | 436 | 5.97 | 174 | 8.18 |

| Analgesics | 425 | 5.82 | 125 | 5.88 |

| Blood agent | 400 | 5.47 | 74 | 3.48 |

| Immunological agents | 344 | 4.71 | 5 | 0.24 |

| Ophthalmic agents | 278 | 3.80 | 63 | 2.96 |

| Blood glucose regulators | 273 | 3.74 | 119 | 5.60 |

| Anti-cancer | 201 | 2.75 | 7 | 0.33 |

| Genitourinary agents | 136 | 1.86 | 75 | 3.53 |

| Anesthetics | 88 | 1.20 | 18 | 0.85 |

| Metabolic bone disease Agents | 36 | 0.49 | 7 | 0.33 |

| Antigout agents | 12 | 0.16 | 5 | 0.24% |

| Others | 720 | 9.85 | 401 | 18.86% |

Fig. 5.

Pharmacological classes of drugs imported from abroad.

Fig. 6.

Comparing the manufacturing of local to imported pharmaceutical classes of drugs.

Since KSA government is paying all health care costs for almost all the Saudis, Saudi Arabia's healthcare expenditure has increased to US$46.66 billion in 2020 (Rahman & Salam, 2021). Results obtained from showed that there are many drug classes are not manufactured by our local companies and needed to be imported from other countries to fulfill the needs of our community.

Definitely, Saudi pharmaceutical companies must consider manufacturing these drugs and increase our local drug security and lower healthcare expenditure in the Kingdom. In Saudi Arabia, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, heart diseases, and asthma are reported as the common chronic diseases and with this results and distributions of pharmacological classes we not covering the need (Almezaal et al., 2021).

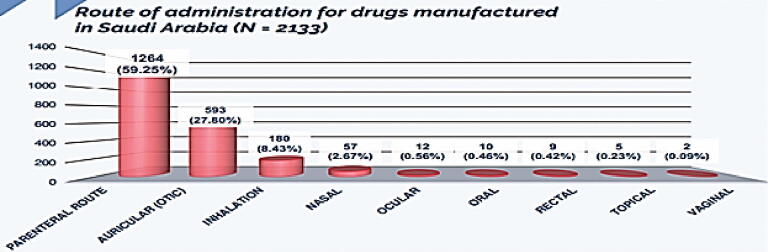

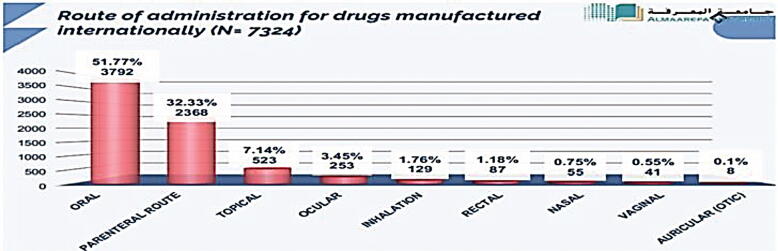

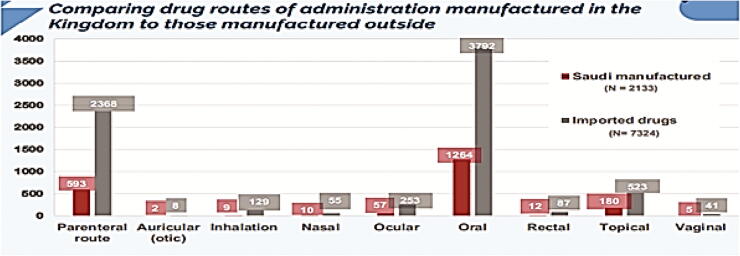

3.6. Comparing the drug route of administrations of local pharmaceutical products to drug route of administrations of medicine from abroad

In this part, we have analyzed all the registered drug route of administration using SFDA drug formulary. This was done to estimate what drug route of administrations, Saudi pharmaceutical companies focused on their production, as well, the most drug route of administrations that are imported from abroad. The results obtained from this work will give to us clear vision on the most route of administration needed to be manufactured in Saudi Arabia to encourage Saudi pharmaceutical companies to fulfill the local needs and increase their contribution in Saudi drug security. Fig. 7 illustrates the percentage of each drug route of administration manufactured in the Kingdom (N = 2133). Results showed that parenteral route of administration (intramuscular, intravenous, subcutaneous, and hemodialysis) was the highest in local pharmaceutical production representing 59.25% of total local production followed by auricular route (27.80%), inhalation (8.43%), nasal (2.67%), ocular (0.56%), oral (0.46%), rectal (0.42%), topical (0.23%), and vaginal (0.09%). In addition, we measured the percentage of drug route of administration imported from abroad (N = 7324) (Fig. 8). Results obtained from this work showed that oral route was the highest drug route of administration imported from abroad representing 51.77% of total imported drugs followed by parenteral route (32.33%), topical (7.14%), ocular (3.45%), inhalation (1.76%), rectal (1.18%), nasal (0.75%), vaginal (0.55%), and auricular (0.1%). Furthermore, we have compared the count of route of administration of pharmaceutical products manufactured in Saudi Arabia (N = 2133) to those imported from abroad (N = 7324). Results are shown in Fig. 9. Results from Fig. 9 indicated that all the drug route of administrations are imported from abroad in very large quantities when compared to the drug route of administration manufactured by Saudi pharmaceutical companies. This result explains the small percentage of contribution by Saudi manufacturers in local drug security. Unfortunately, this small contribution makes a large additional burden on the Kingdom's annual budget as a result of the overdependence on medicine from abroad.

Fig. 7.

Route of administration for drugs manufactured in Saudi Arabia (N = 2133).

Fig. 8.

Route of administration for drugs manufactured internationally (N = 7324).

Fig. 9.

Comparing drug routes of administration manufactured in the Kingdom to those manufactured outside.

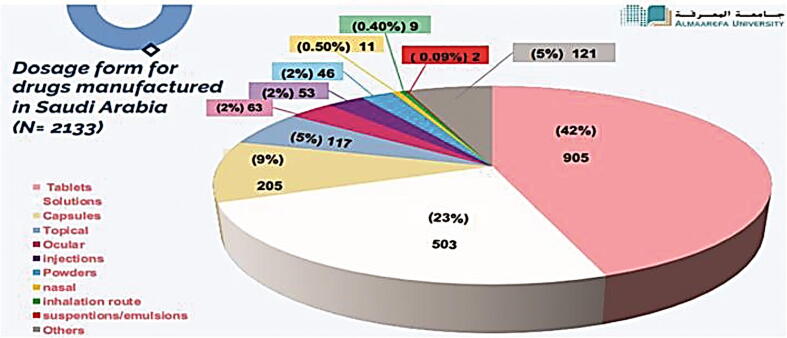

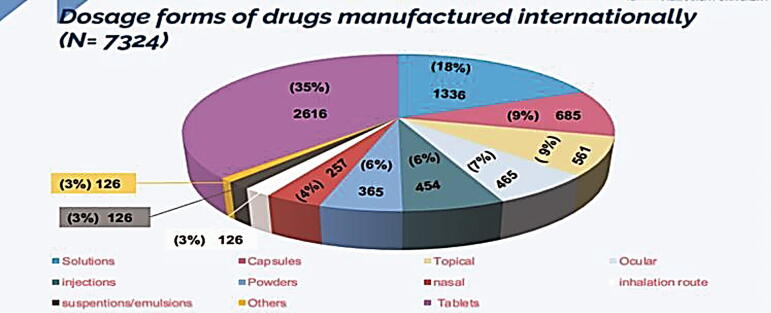

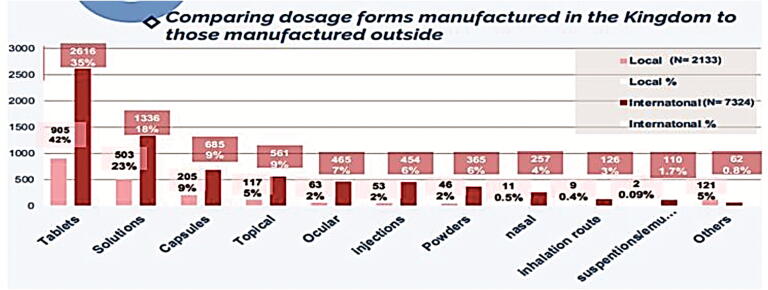

3.7. Comparing dosage forms of local pharmaceutical products to dosage forms of medicine from abroad

In this part, we have analyzed all the registered dosage forms using SFDA drug formulary. This was done to estimate what dosage forms Saudi pharmaceutical companies focused on their production, and as well, the most dosage forms that are imported from abroad. The results obtained from this work will give to us clear vision on the most dosage forms needed to be manufactured in Saudi Arabia to encourage Saudi pharmaceutical companies to fulfill the local needs and increase their contribution in Saudi drug security.

Fig. 10 demonstrates the percentage of each dosage form manufactured in the Kingdom (N = 2133). Tablets were found to be the highest percentage composing 42.4% of all local drug production followed by solutions (injection, infusion, peritoneal dialysis, etc.) (15.56%), syrups (9.61%), capsules (9.23%), creams (3.52%), and others (19.68%). Indeed, the aforementioned findings demonstrate that Saudi pharmaceutical firms are well-equipped to develop generics in traditional dosage forms like tablets and capsules but are unable to do so for non-conventional forms including inhalers, biologicals, and plasma-derived products. Additionally, we have measured each dosage form imported from abroad (Fig. 11). In this work, we have discovered that the highest percentage of imported drugs were tablets (35%) followed by solutions (18.24%), injections (9.35%), capsules (7.65%), powders/granules (6.34%), and others (23.42%). Furthermore, we have compared the count of dosage forms of pharmaceutical products manufactured in Saudi Arabia (N = 2133) to those imported from abroad (N = 7324). Results are shown in Fig. 12. Results from Fig. 12 indicated that all dosage forms are imported from abroad in very large quantities when compared to the dosage forms manufactured by Saudi pharmaceutical companies. This result explains the small percentage of contribution by Saudi manufacturers in local drug security. Unfortunately, this small contribution makes a large additional burden on the Kingdom's annual budget as a result of the overdependence on medicine from abroad.

Fig. 10.

Dosage form for drugs manufactured in Saudi Arabia (N = 2133).

Fig. 11.

Dosage forms of drugs manufactured internationally (N = 7324).

Fig. 12.

Comparing dosage forms manufactured in the Kingdom to those manufactured outside.

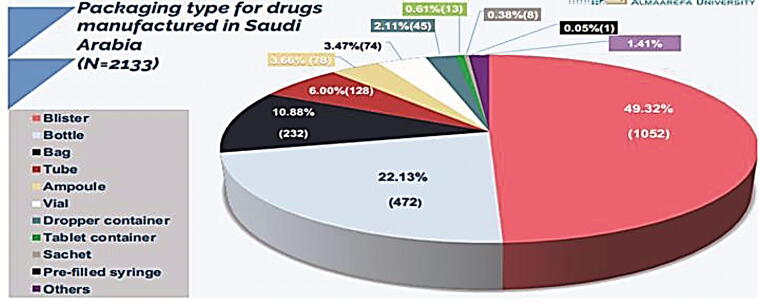

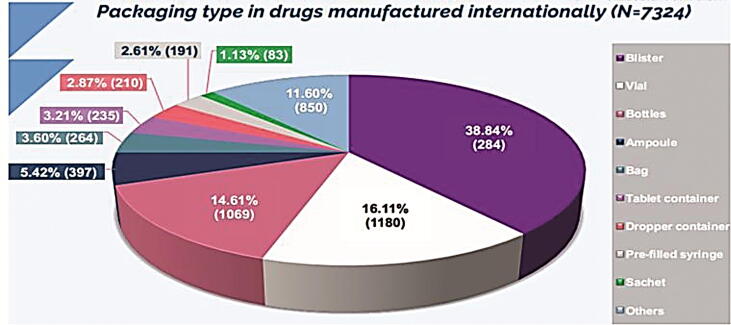

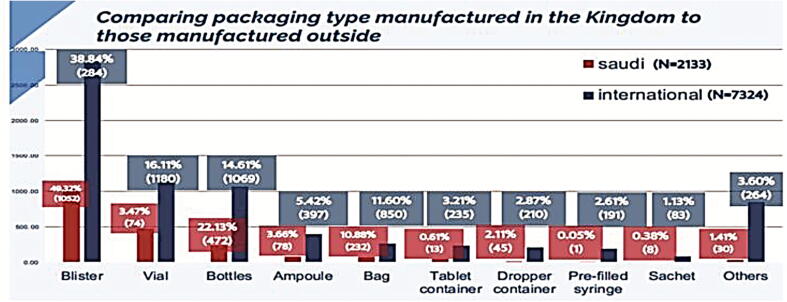

3.8. Comparing packaging type of local pharmaceutical products to dosage forms of medicine from abroad

In this part, we have analyzed all packaging types of registered drugs using SFDA drug formulary. This was done to estimate what packaging types Saudi pharmaceutical companies focused on their production, and as well, the most packaging types that are imported from abroad. The results obtained from this work will give to us clear vision on the most packaging types needed to be manufactured in Saudi Arabia to encourage Saudi pharmaceutical companies to fulfill the local needs and increase their contribution in Saudi drug security. In this work, we have estimated the percentage of each packaging type manufactured in the Kingdom (N = 2133). As seen in Fig. 13, manufacturing of blisters showed the highest percentage (49.32%) followed by bottles (22.13%), bags (10.88%), tubes (6%), ampoules (3.66%), vials (3.47%), dropper containers (2.11%), and others (2.43%) of total local packaging types. Moreover, we have determined the percentages of packaging types imported from abroad (N = 7324) (Fig. 14). We have estimated that blisters have the highest percentage of imported packaging types (38.84%) followed by vials (16.11%), bottles (14.61%), ampoules (5.42%), and others (25.02%) of total internationally packaging items. Furthermore, we have compared the count of packaging items of pharmaceutical products manufactured in Saudi Arabia (N = 2133) to those imported from abroad (N = 7324). Results are shown in Fig. 15. Results from Fig. 15 indicated that all packaging items are imported from abroad in very large quantities when compared to those manufactured by Saudi pharmaceutical companies. This result explains the small percentage of contribution by Saudi manufacturers in local drug security. Unfortunately, this small contribution makes a large additional burden on the Kingdom's annual budget as a result of the overdependence on medicine from abroad. In 2016, the 2030 vision of the KSA raised with ambitious goals towards developing the Kingdom and its nation. However, despite the growth in Saudi pharmaceutical market, previous studies showed that the number of local pharmaceutical industries in KSA exceeds 40, covering only 22.5% of the Kingdom’s consumption of dispensed medicines. This study is undertaken to support 2030 ambitious vision. Therefore, we aimed to explore the contribution of localized pharmaceutical industries in Saudi drug security as well as the distribution of local pharmaceuticals in our country. To achieve the goal of this study, we have analyzed all the registered drugs, solutions, and packaging items using SFDA drug formulary. This was done to estimate what are the pharmaceutical products Saudi pharmaceutical companies focused on their production, and as well, the most pharmaceutical products that are imported from abroad. Findings of this project has explained the small percentage of contribution by Saudi manufacturers in local drug security. Unfortunately, this small contribution makes a large additional burden on the Kingdom's annual budget as a result of the overdependence on medicine from abroad. The results obtained from this study has provided information about the most pharmaceutical products that needs to be locally manufactured or increase their production in the kingdom to rise the contribution of local pharmaceutical industries in Saudi drug security and fulfill the needs of our community. In fact, the two primary issues that will need to be addressed to get rid of medicine importation into the Saudi market are the lack of pharmaceutical research and development (R&D) and the excessive outpatient drug spending. In reality, funding medication development and production could help to reduce the country's excessive reliance on imports of pharmaceuticals (Alzahrani and Harris, 2021). The establishment of numerous contract development and manufacturing organizations (CDMOs) in numerous industrial locations, which may provide extensive offices from drug development to drug manufacture, is another strategy to promote local drug production (Huang, 2022). This reassignment of administrations would hasten the Kingdom's ability to adapt and localize the manufacture of pharmaceuticals (Rahman and Salam, 2021). The government, pharmaceutical businesses, and other relevant stakeholders should encourage localizing medication and pharmaceutical item production since it will be essential for drug security and the healthcare system ( Rahman and Salam, 2021, Huang, 2022). Consequently, to reach drug security in Saudi Arabia, we propose the following, working on benefiting from the elements available in Saudi Arabia associated with the localization of the pharmaceutical industry like capital, energy and great potentials, giving the pharmaceutical research and development process more attention through collaboration between Saudi pharmaceutical companies and research centers and increasing spending on them, more effort in qualifying national personnel specialized in pharmacy, the importance of moving towards manufacturing of innovative and vital medicines, and medicines that are used in the treatment of stubborn diseases.

Fig. 13.

Packaging type for drugs manufactured in Saudi Arabia (N = 2133).

Fig. 14.

Packaging type in drugs manufactured internationally (N = 7324).

Fig. 15.

Comparing packaging type manufactured in the Kingdom to those manufactured outside.

According to 2030 vision, the local drug manufacture will be facilitated by government support, reduction in import medicines, increasing academic-industry collaboration, gearing up of local companies, encouragement by regulatory agencies, and providing incentives for local manufacturing. These factors will encourage the global and local companies for local manufacturing.

The steady state increase in patient population, significant reduction in imported medicines, the adaptations of the next generation therapies such as gene/stem cell therapies, the vaccine development, development of advanced materials and development of pharmaceuticals using novel technologies such as 3-D printing, artificial intelligence, and machine learning will be the future perspectives of the pharmaceutical industries in the KSA (Rantanen and Khinast, 2015, Damiati, 2020, Webb et al., 2022, Wollensack et al., 2022).

4. Conclusion

With the increasing prevalence of many diseases among Saudi Arabia population, KSA is the largest pharmaceutical market in that region. However, despite the growth in Saudi pharmaceutical market, 40 local pharmaceutical industries that have product register in SFDA are covering only 22.5% of the Kingdom’s consumption of dispensed medicines. This study has explored the contribution of localized pharmaceutical industries in Saudi drug security as well as the distribution of local pharmaceuticals in our country. Unfortunately, the small contribution of Saudi pharmaceutical companies in local drug security makes a large additional burden on the Kingdom's annual budget as a result of the overdependence on medicine from abroad. This study was undertaken to support 2030 ambitious vision through encouraging the contribution of local pharmaceutical industries in Saudi drug security to fulfill the needs of our community. The data provided in this study will help to increase the local drug manufacturing in the Kingdom and hence reduce the burden of the Kingdom in importing the medicines from abroad.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

“Authors are thankful to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2023R146), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for supporting this work”. “Authors are also thankful to AlMaarefa University for their generous support”.

References

- Al-Aqeel S.A., Al-Salloum H.F., Abanmy N.O., Al-Shamrani A.A. Undispensed prescriptions due to drug unavailability at a teaching hospital in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Health Res. 2010;3:213–216. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jazairi A.S., Al-Qadheeb N.S., Ajlan A. Pharmacoeconomic analysis in Saudi Arabia: an overdue agenda item for action. Ann. Saudi Med. 2011;31:335–341. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.83201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkhenizan A. The pharmacoeconomic picture in Saudi Arabia. Exp. Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2014;14:483–490. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2014.908712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almezaal E.A.M., Elsayed E.A.H., Javed N.B., Chandramohan S., Al-Mohaithef M. Chronic disease patients' satisfaction with primary health-care services provided by the second health cluster in Riyadh. Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Health Sci. 2021;10:185–190. [Google Scholar]

- Alrasheedy A.A. Pharmaceutical pricing policy in Saudi Arabia: findings and implications. GaBI J. 2020;9:14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Alruthia Y.S., Alwhaibi M., Alotaibi M.F., Asiri S.A., Alghamdi B.M., Almuaythir G.S., Alsharif W.R., Alrasheed H.H., Alswayeh Y.A., Alotaibi A.J., et al. Drug shortages in Saudi Arabia: Root causes and recommendations. Saudi Pharm. J. 2018;26:947–951. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2018.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsaddique A. Future of the pharmaceutical industry in the GCC countries. Integr. Mol. Med. 2017;4:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Alzahrani R., Harris E. Biopharmaceutical revolution in Saudi Arabia: progress and development. J. Pharmaceut. Innov. 2021;16:110–123. [Google Scholar]

- Assad S.W. The rise of consumerism in Saudi Arabian society. Int. J. Comm. Manag. 2007;17:73–104. [Google Scholar]

- Badreldin H.A., Atallah B. Global drug shortages due to COVID-19: impact on patient care and mitigation strategies. Philos. Phenomenol. Res. Soc. Admmin. Pharm. 2021;17:1946–1949. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damiati S.A. Digital pharmaceutical sciences. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2020;21:E206. doi: 10.1208/s12249-020-01747-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festa G., Kolte A., Carli M.R., Rossi M. Envisioning the challenges of the pharmaceutical sector in the Indian health-care industry: a scenario analysis. J. Business Ind. Market. 2022;37:1662–1674. [Google Scholar]

- Finelli L.A., Narasimhan V. Leading a digital transformation in the pharmaceutical industry: Reimagining the way we work in global drug development. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020;108:756–761. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotez P.J., Batista C., Amor Y.B., Ergonul O., Figueroa J.P., Gilbert S., Gursel M., Hassanain M., Kang G., Kaslow D.C., et al. Global public health security and justice for vaccines and therapeutics in the COVID-19 pandemic. EClin. Med. 2021;39:E10153. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P. The pharmaceutical industry and the future of drug development. Int. J. Res. Dev. Pharm. Life Sci. 2022;8:E1000122. [Google Scholar]

- Jaberidoost M., Nikfar S., Abdollahiasl A., Dinarvand R. Pharmaceutical supply chain risks: a systematic review. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2013;21:E69. doi: 10.1186/2008-2231-21-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan T.M., Emeka P., Suleiman A.K., Alnutafy F.S., Aljadhey H. Pharmaceutical pricing policies and procedures in Saudi Arabia: a narrative review. Ther. Innov. Reg. Sci. 2016;50:236–240. doi: 10.1177/2168479015609648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang R., Yuan Z. 30th European Symposium on Computer Aided Process Engineering. 2020. Computer aided chemical engineering. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman R., Salam M.A. Policy discourses: Shifting the burden of healthcare from the state to the market in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Inquiry. 2021;58 doi: 10.1177/00469580211017655. E469580211017655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen J., Khinast J. The future of pharmaceutical manufacturing sciences. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015;104:3612–3638. doi: 10.1002/jps.24594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkis M., Bernardi A., Shah N., Papathanasiou M.M. Emerging challenges and opportunities in pharmaceutical manufacturing and distribution. Processes. 2021;9:E457. [Google Scholar]

- Shafiq N., Pandey A.K., Malhotra S., Holmes A., Mendelson M., Malpani R., Balasegaram M., Charani E. Shortage of essential antimicrobials: a major challenge to global health security. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6:E006961. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukar S., Zahoor F., Hayat K., Saeed A., Gillani A.H., Omer S., Hu S., Babar Z.U., Fang Y., Yang C. Drug shortage: Causes, impact, and mitigation strategies. Front. Pharmacol. 2021;12:E693426. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.693426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuman A.G., Fox E.R., Unguru Y. COVID-19 and drug shortages: a call to action. J. Manag. Care Special. Pharm. 2020;26:945–947. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2020.26.8.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultana J. Future prospects and barriers of pharmaceutical industries in Bangladesh. Bangladesh Pharm. J. 2016;19:53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Tawfik E.A., Tawfik A.F., Alajmi A.M., Badr M.Y., Al-jedai A., Almozain N.H., Bukhary H.A., Halwani A.A., Al Awadh S.A., Alshamsan A., Babhair S., Almalik A.M. Localizing pharmaceuticals manufacturing and its impact on drug security in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm. J. 2022;30:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2021.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D. In: Pharmaceuticals in the environment. Hester R.E., Harrison R.M., editors. Royal Society of Chemistry, England; UK.: 2015. The pharmaceutical industry and the future of drug development; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- The Report, 2018. Saudi Arabia increases domestic pharmaceuticals production. Health & Life Sciences chapter of The Report: Saudi Arabia. (Accessed on 15 October 2022). https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/reports/saudi-arabia/2018-report/health-life-ciences.

- Vasisht K., Sharma N., Karan M. Current perspective in the international trade of medicinal plants material: an update. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2016;22:4288–4336. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666160607070736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma S., Singh S.P. Current and future status of herbal medicines. Vet. World. 2008;1:347–350. [Google Scholar]

- Webb C., Ip S., Bathula N.V., Popava P., Soriano S.K.V., Ly H.H., Eryilmaz B., Huu V.A.N., Broadhead R., Rabel M., et al. Current status and future perspectives on MRNA drug manufacturing. Mol. Pharm. 2022;19:1047–1058. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.2c00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollensack L., Budzinski K., Backmann J. Defossilization of pharmaceutical manufacturing. Curr. Opin. Green Sus. Chem. 2022;33:E100586. [Google Scholar]