Abstract

Background and Objective

Self-medication (SM) has significantly increased worldwide in the past decades, which may have detrimental health consequences including antimicrobial resistance, adverse drug reactions, drug-drug interaction, and dependency. Although several studies have evaluated the extent of SM, such studies are still limited in Jordan. The aim of this study was to explore sources of SM information, attitudes toward SM and the practice of SM and its associated factors.

Methods

The data of this cross-sectional study was collected between February and July 2022. A validated questionnaire was distributed to patients attending pharmacies from different locations in Jordan. The survey evaluated sources of information and attitudes toward SM, extent of SM practice, and attitudes towards SM, symptoms that the participants treat with SM and those that usually requires medical doctor consolation, followed by questions about the classes of medications mostly used for SM and the reasons for SM.

Results and Discussion

The study enrolled 695 Jordanian adults. The most reported indications for SM included headache (86.9 %), flu (76.4 %), and fever (69.6 %). The most common causes for SM included previous knowledge about the diseases and its treatments (84.2 %), and full knowledge of the medicine to be purchased (55.2 %). Results of the ordinal regression showed that physician counseling frequency was positively and significantly associated with “not being on chronic medication” (p-value = 0.001), and having a positive SM attitude level (p-value = 0.019), while negatively correlated with being in medical field (p-value < 0.001), having no children (p-value = 0.009), and relaying on non-scientific sources to obtain information for SM (p-value = 0.014). The frequency of SM practice was positively associated with being in medical field (p-value < 0.001, having no insurance (p-value < 0.001), and relaying on nonscientific sources (p-value = 0.017). Lastly, having a positive SM attitude level (p-value < 0.001) and not being on chronic medications (p-value = 0.007) were associated with decreased SM practice.

Conclusion

The study participants demonstrated increased SM practice due to the wrong perceptions toward SM and the reliance on non-scientific source of information about SM practice.

Keywords: Self-Medication, Source of information, Attitude, Practice, Side effects

1. Introduction

Self-medication (SM) is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Pharmaceutical Federation as the process by which a person chooses and employs medications to treat signs, symptoms, or minor health issues that one has independently identified as such (Dutta et al., 2017). It can also be defined as a component of self-care which include the use of medication for the treatment of self-recognized ailments without a prescription from a healthcare provider such as sharing medication with family members, or using leftover medication (Mathias et al., 2020).

The prevalence of SM has significantly increased globally in the past decades (Behzadifar et al., 2020). SM practice varies greatly between different societies. For example, a study reported that 71 % of men and 82 % of women used SM at least once in the past six months in the United States of America (Hong et al., 2005). Another study reported that only 27 % of the study sample used SM to manage pain in Spain (Bassols et al., 2002). In the Middle East region, a study found that 40.4 % of the general population used antibiotics without medication (Nusair et al., 2021), while a study conducted in Kuwait found that 92 % of the adolescents used SM (Abahussain et al., 2005). According to Elayeh et al., this phenomenon particularly increased during the COVID-19 pandemic (Elayeh et al., 2021).

Although SM may have some advantages such as time and money saving, providing quick relief, and treating minor illnesses, it may cause adverse drug reactions, use of inappropriate medicines, wrong dosage, incorrect diagnosis, polypharmacy, drug resistance, delay in finding appropriate care, increased risk of drug abuse and dependency and drug-drug interactions (Baral and Dahal, 2019, Mamo et al., 2018).

Over the counter (OTC) medications are effective and safe for SM, but using them inappropriately owing to ignorance of their adverse effects and drug combinations can have serious consequences, especially for vulnerable populations like children, the elderly, pregnant women, and breastfeeding mothers (Chouhan and Prasad, 2016).

The most reported reasons for SM in previous literature include prior sickness, sufficient knowledge about the condition, financial or economic issues that prevent consulting a doctor, lack of time, and easy availability of drugs, especially in developing nations.(Abdi et al., 2018). Other significant factors that affect SM include patient dissatisfaction with the healthcare provider, and medicine costs (Chouhan and Prasad, 2016). The most common conditions that may lead to SM use are pain, headache, cold and flu, fever, psychological diseases, skin problems, and viral and bacterial infections (Alkhawaldeh and Khraisat, 2020).

SM may include prescription medicines (particularly in developing countries), OTC drugs, minerals, vitamins, and herbal products (Tripković et al., 2018). The most common categories of drugs used in SM are analgesics, antibiotics, oral contraceptives, antacids, and oral hypoglycemic agents (Sado et al., 2017).

Several studies have evaluated the extent of SM; however, such studies remain limited in the Middle East and Jordan. The aim of the current study was to explore sources of SM information, attitudes toward SM and the practice of SM and its associated factors.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study site and subjects

The questionnaire of the present cross-sectional study was distributed to customers attending several pharmacies in different locations in Jordan including the capital Amman, Irbid, Zarqa and Salt in the period from February through July 2022. The inclusion criteria included being 18 or older, resident in Jordan and agreed to participate in the study. Eligible participants were asked to sign an informed consent form. Ethical approval was obtained from the ethical committee at Al-Zaytoonah University where the first author is affiliated (Ref #:9/13/2021–2022).

2.2. Sample size calculation

A convenient sampling method was used for participant’s enrollment. Sample size calculation was based on Krejcie and Morgan method for nonspecific population size (Krejcie and Morgan, 1970). The required number of participants for this study was calculated at 95 % confidence interval and 5 % confidence level and was equal to 385 participants.

2.3. The study instrument

The study questionnaire was developed after conducting a thorough literature review (Banerjee and Bhadury, 2012, Biswas et al., 2014, Grigoryan et al., 2008, Lv et al., 2014, Sambakunsi et al., 2019, Tuyishimire et al., 2019). The demographic part of the questionnaire collected information including age, gender, education level, medical field education/experience, marital status, health insurance, having children and their number. The source of information about SM was classified into scientific or non-scientific sources. The participant would be included in the non-scientific group if they selected at least one of the non-scientific sources, which included previous knowledge, friends, or internet. On the other hand, the participant would be included in the scientific group if they only selected scientific sources which included pharmacist inside the pharmacy or medical platforms. The attitude towards SM was evaluated based on the answers of participants in the attitude items. The score ranged from 1 point for “strongly agree” to 5 points for “strongly disagree” in the attitude items except for “Self-medication is harmless”, “Self-medication is accepted by medical doctors”, “Self-medication decreases the burden on the medical doctors” and “Self-medication is more cost effective than approaching a health care professional”, where reverse scoring was used. Higher attitude scores indicated a more negative attitude towards SM. The practice of SM and doctor consultation were evaluated using the questions: “Do you consult a doctor before using any medication?”, and “Do you go directly to the pharmacy and order medications on your own (without consulting a medical doctor or pharmacist)?” with answer scale ranging from “never” to “always”. The following section included questions about symptoms that most often the participants treat with SM, and those that usually requires medical doctor consolation, followed by questions about the medication classes mostly used for SM by the participants and lastly the reasons for SM practice. The study instrument (in English and Arabic) is available in the appendices A1 and A2.

2.4. Instrument validity

The content validity of the questionnaire was confirmed by an expert panel. The questionnaire was translated from English to Arabic, which is the official language in Jordan, and then back translated by different translators and both versions were similar. Face validity was conducted by distributing the Arabic version of the questionnaire to 30 participants in a pilot study to assess the clarity of the questionnaire, and no modifications were required. Data of the pilot study were not included in the final analysis. Further analysis was conducted to evaluate the internal consistency and structure validity of the only latent variable composed in the present study, which was the attitude towards self-medication. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test result for the attitude items was 0.88 and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant χ 2 (66) = 3880.33, p < 0.01 which confirms the suitability of the data for factor analysis. Communalities produced by EFA were all above 0.35, therefore, all the 12 items were retained in the EFA. Parallel analysis and scree plots (Fig. 1) suggested that a two-factor model is the most suitable model for the study data. The two-factor model included disadvantages of SM (factor 1) and advantages of SM (factor 2). The lowest communality and factor loading of the items included in the model were 0.35 and 0.55 respectively, for the item “Self-Medication is acceptable by medical doctors” l (Table 2). Cronbach’s alpha the factors disadvantages of SM and advantages of SM were 0.91 and 0.72, while the Cronbach’s alpha for the complete attitude scale 0.82 indicating good internal consistency.

Fig. 1.

Scree plots of the attitude scale.

Table 2.

Attitudes toward SM.

| Strongly agree n (%) | Agree n (%) | Neutral n (%) | Disagree n (%) |

Strongly disagree n (%) |

Median (25–75) |

Communalities | Factor loadings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-medication is harmless*# | 57 (8.3 %) | 276 (40.3 %) | 40 (5.8 %) | 258 (37.7 %) | 54 (7.9 %) | 3 (2–4) | 0.46 | 0.65 |

| Self-medication is accepted by medical doctors*# | 44 (6.4 %) | 106 (15.5 %) | 49 (7.2 %) | 447 (65.3 %) | 39 (5.7 %) | 2 (2–3) | 0.35 | 0.56 |

| Self-medication can increase the risk for drug side effects^ | 176 (25.7 %) | 302 (44.1 %) | 56 (8.2 %) | 94 (13.7 %) | 57 (8.3 %) | 2 (1–3) | 0.58 | 0.76 |

| Self-medication can worsen your health status^ | 182 (26.6 %) | 300 (43.8 %) | 40 (5.8 %) | 108 (15.8 %) | 55 (8.0 %) | 2 (1–3) | 0.68 | 0.82 |

| Subsequent to self-medication failure, management of the health condition is more difficult^ | 172 (25.1 %) | 297 (43.4 %) | 51 (7.4 %) | 95 (13.9 %) | 70 (10.2 %) | 2 (1–3) | 0.64 | 0.80 |

| Self-medication can lead to higher rates of hospital admission^ | 169 (24.7 %) | 295 (43.1 %) | 42 (6.1 %) | 118 (17.2 %) | 61 (8.9 %) | 2 (2–4) | 0.70 | 0.83 |

| Self-medication can delay the diagnosis of several diseases which may lead to worsening of health outcomes^ | 223 (32.6 %) | 291 (42.5 %) | 58 (8.5 %) | 60 (8.8 %) | 53 (7.7 %) | 2 (1–2.5) | 0.69 | 0.83 |

| Self-medication by antibiotics can lead to higher bacterial resistance^ | 275 (40.1 %) | 284 (41.5 %) | 38 (5.5 %) | 50 (7.3 %) | 38 (5.5 %) | 2 (1–2) | 0.62 |

0.79 |

| Self-medication decreases the burden on the medical doctors*# | 92 (13.4 %) | 263 (38.4 %) | 41 (6.0 %) | 236 (34.5 %) | 53 (7.7 %) | 4 (2–4) | 0.52 | 0.71 |

| Self-medication is more cost effective than approaching a health care professional*# | 173 (25.3 %) | 313 (45.7 %) | 46 (6.7 %) | 110 (16.1 %) | 43 (6.3 %) | 4 (3–5) | 0.50 | 0.68 |

| Self-medication can affect the chronic medications that you use^ | 217 (31.7 %) | 291 (42.5 %) | 58 (8.5 %) | 60 (8.8 %) | 59 (8.6 %) | 2 (1–3) | 0.54 | 0.73 |

| Self-medication can lead to higher rates of drug-drug interactions^ | 266 (38.8 %) | 265 (38.7 %) | 42 (6.1 %) | 57 (8.3 %) | 55 (8.0 %) | 2 (1–2) | 0.61 | 0.78 |

| Attitude score | 29 (25–36) | |||||||

*Reverse coding was used. # items of the factor “advantages of SM”. ^ items included in the “disadvantages of SM”.

2.5. Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 26. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were expressed as medians and quartiles or means (SD). Two ordinal regression models were constructed to evaluate variables associated with participants’ frequency of SM, and frequency of consulting a medical doctor before taking a medication. Independent variables included in the two models were: age, sex, marital status, having children, education level, income level, work/educated in medical field, attitudes score towards SM, health insurance, taking chronic medication, and source of information about SM (scientific/non-scientific).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic characteristics of the participants

The study included 685 participants. Most of the participants were 18–29 years old (43.4 %), most of the participants were females (66.0 %), more than half of the respondents were married (54.5 %), and the majority had a bachelor’s degree (49.1 %). Moreover, more than half of the participants work or study in a nonmedical field, and most of the respondents had an average income of<500 JD (55.5 %). Furthermore, most of the participants were covered by health insurance and did not have any children (61.5 % and 50.4 %, respectively), as for the participants who have children, most of them have 3 children or more (30.1 %). Demographic characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants.

| Frequency (%) N = 685 |

||

|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–29 | 297 (43.4 %) |

| 30–39 | 218 (31.8 %) | |

| 40–49 | 120 (17.5 %) | |

| 50–59 | 40 (5.8 %) | |

| 60 or older | 10 (1.5 %) | |

| Sex | Female | 452 (66.0 %) |

| Male | 233 (34.0 %) | |

| Marital status | Married | 373 (54.5 %) |

| Other | 312 (45.5 %) | |

| Educational level | High school or less | 114 (16.6 %) |

| University student/institute | 51 (7.4 %) | |

| Diploma | 67 (9.8 %) | |

| Bachelor | 336 (49.1 %) | |

| Master | 83 (12.1 %) | |

| PhD | 34 (5.0 %) | |

| Field of work or study | Medical filed | 305 (44.5 %) |

| Non-medical field | 380 (55.5 %) | |

| Average income | <500JDs | 380 (55.5 %) |

| 500–1000 JDs | 197 (28.8 %) | |

| More than 1000 JDs | 108 (15.8 %) | |

| Covered by health insurance? | No | 264 (38.5 %) |

| Yes | 421 (61.5 %) | |

| Do you have children? | No | 345 (50.4 %) |

| Yes | 340 (49.6 %) | |

| How many children do you have? | One | 86 (23.6 %) |

| Two | 84 (23.0 %) | |

| Three | 85 (23.3 %) | |

| More than 3 | 110 (30.1 %) | |

3.2. Information source about SM

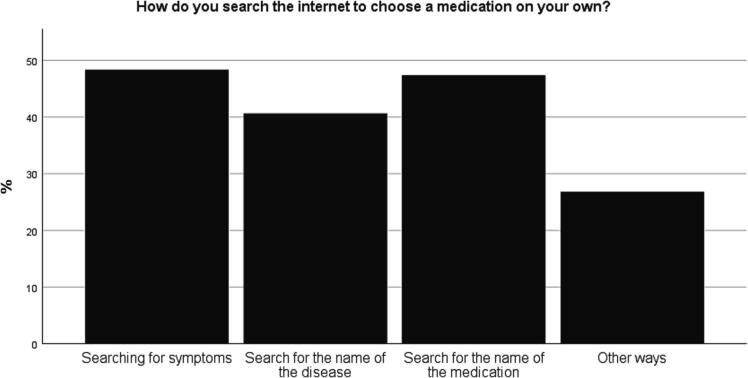

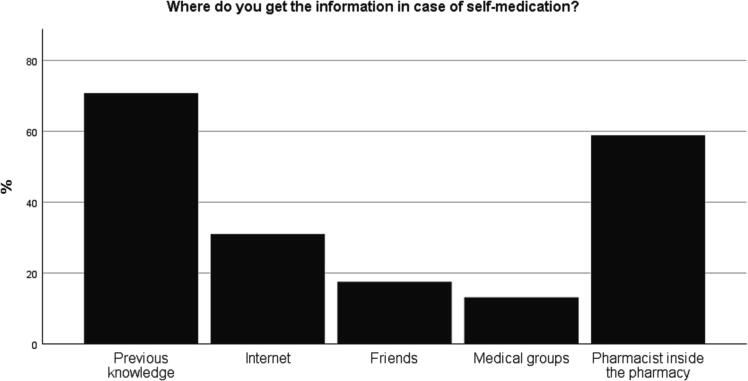

Most of the participants had previous knowledge about SM (70.8 %). As shown in Fig. 2, most of the participants obtained information about SM by asking the pharmacist inside the pharmacy (58.8 %) and by searching the internet (30.9 %), Most of the participants who searched the internet in order to choose a medication on their own, for the symptoms and the name of the medication (48.3 % and 47.3 %), followed by searching for the name of the disease (40.6 %) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Categories used to search the internet to choose a medication on their own.

Fig. 2.

Information Sources about SM.

3.3. Attitude towards SM

The median for the attitude score was 29 (quartiles = 25–36) out of a maximum possible score of 60, which reflects an average attitude toward the SM medication with an area for improvement in several items. As shown in Table 2, the highest median for the advantages of SM items was reported for “Self-medication is more cost-effective than approaching a health care professional” a median of 4 (quartiles = 3–5), “Self-medication decreases the burden on medical doctors” a median of 4 (quartiles = 2–4), and the item “Self-medication is harmless” median of 3 (quartiles = 2–4). The lowest median for the disadvantages of SM was reported for the items “Self-medication with antibiotics can lead to higher bacterial resistance”, “Self-medication can lead to higher rates of drug-drug interactions” a median of 2 (quartiles = 1–2), and “Self-medication can delay the diagnosis of several diseases which may lead to worsening of health outcomes” a median of 2 (quartiles = 1–2.5).

3.4. SM practices of the participants

Table 3 shows that most of the participants responded sometimes to the questions “Do you consult a doctor before using any medication?” and “Do you go directly to the pharmacy and order medications on your own?” (28.9 % and 32.1 %, respectively). Nearly a quarter of the participants (25.7 %) reported that they always consult a doctor before taking a medication, and only 20.5 % of the participants reported that they never go directly to the pharmacy and order medications on their own. Almost half of the participants used non-chronic medication more than twice in the last 6 months (48.2 %). Moreover, most of the participants did not think that SM is better than consulting a health care professional when the medication is for them and not for their children or anyone else (78.4 %).

Table 3.

SM practices of the participants.

| Frequency (%) or Mean (±SD) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Do you consult a doctor before using any medication? |

Always | 176 (25.7 %) |

| Most of the time | 149 (21.8 %) | |

| Sometimes | 198 (28.9 %) | |

| Rarely | 37 (5.4 %) | |

| Never | 125 (18.2 %) | |

| Do you go directly to the pharmacy and order medications on your own without consulting a medical doctor or pharmacist? | Never | 140 (20.4 %) |

| Rarely | 42 (6.1 %) | |

| Sometimes | 220 (32.1 %) | |

| Most of the time | 173 (25.3 %) | |

| Always | 110 (16.1 %) | |

| During the past 6 months, how many times did you need to use nonchronic medications? | Never | 156 (22.8 %) |

| Once | 95 (13.9 %) | |

| Twice | 104 (15.2 %) | |

| More than 2 | 330 (48.2 %) | |

| I think that self-medication is better than consulting a health care professional when the medication is for me and not for my children or anyone else | No | 537 (78.4 %) |

| Yes | 148 (21.6 %) | |

The most consumed medications in SM were analgesics (89.8 %) and decongestants (59.4 %), followed by allergy medications (35.9 %). While the least consumed medications were sedatives (1.6 %), sleep disturbances, 1.8 %, and weight loss medications (4.1 %). The average number of medication classes used in SM was 2.84 (±1.27). (Table A1 in the supplementary material).

3.5. Reported symptoms that lead to SM and causes for resorting to SM

Most participants consulted a doctor when they had symptoms of diabetes, hypertension, or mental disorders (95.3 %, 94.5 %, and 90.4 %, respectively). While most of the participants self-medicated when they had symptoms such as headache, flu, or fever (86.9 %, 76.4 %, and 69.9 %, respectively) (Table A2 in the supplementary material). The most reported causes for SM were “Previous knowledge about the disease and its treatment” and “Full knowledge of the medication to be purchased” (84.2 %; n = 577 and 55.2 %; n = 378, respectively), followed by “The disease is simple and does not require a doctor's consultation” (n = 361; 52.7 %). While the least reported reasons for SM were “Lack of trust in doctors and specialists” (n = 61; 8.9 %) and “Financially unable to go to a doctor” (n = 112; 16.4 %), followed by “Reading from the internet about the disease and medication” (n = 119; 17.4 %). Reading about medications’ side effect (n = 157; 22.9 %) as well as saving time/effort (n = 205; 29.9 %) were among other reasons for SM practice (Table A3 in the supplemenatry material).

3.6. Variables associated with SM level

Ordinal regression was conducted to evaluate the variables associated with SM frequency, as evaluated by “Do you go directly to the pharmacy and order medications on your own (without consulting a medical doctor or pharmacist)?” with responses ranging from never to always. Variables that significantly increased the frequency of SM practice included being in medical field (Coefficient estimate = 1.060; 95 %CI: 0.736–1.384; p-value < 0.001), having no health insurance (Coefficient estimate = 0.612; 95 %CI: 0.309–0.915; p-value < 0.001), and relaying on nonscientific sources (Coefficient estimate = 0.447; 95 %CI: 0.079– 0.816; p-value = 0.017). While the variables that decreased the frequency of SM practice included having a positive SM attitude level (Coefficient estimate = -0.519; 95 %CI: −0.801 – −0.238; p-value < 0.001) and not being on chronic medications (Coefficient estimate = -0.465; 95 %CI −0.804 – −0.125; p-value = 0.007) Table 4.

Table 4.

Variables associated with the frequencies of Self-Medication and doctor counseling.

| Frequency of doctor counseling | Frequency of Self-Medication | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | p-value | 95 % Confidence Interval | Estimate | p-value | 95 % Confidence Interval | ||||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| Age |

18–29 | −0.579 | 0.343 | −1.778 | 0.619 | 0.097 | 0.873 | −1.094 | 1.288 |

| 30–39 | −0.633 | 0.291 | −1.809 | 0.542 | 0.305 | 0.608 | −0.861 | 1.472 | |

| 40–49 | −0.708 | 0.246 | −1.906 | 0.489 | 0.678 | 0.263 | −0.510 | 1.867 | |

| 50–59 | −0.299 | 0.649 | −1.587 | 0.988 | 0.396 | 0.544 | −0.883 | 1.674 | |

| 60 or older (Ref) | 0a | . | . | . | 0a | . | . | . | |

| Sex | Female | 0.157 | 0.310 | −0.146 | 0.461 | −0.128 | 0.412 | −0.434 | 0.178 |

| Male (Ref) | 0a | . | . | . | 0a | . | . | . | |

| Marital Status | Married | −0.361 | 0.116 | −0.811 | 0.090 | −0.280 | 0.224 | −0.730 | 0.171 |

| Other (Ref) | 0a | . | . | . | 0a | . | . | . | |

| Education | High school or less | −0.504 | 0.204 | −1.281 | −0.274 | −0.017 | 0.966 | −0.798 | 0.764 |

| University student/institute | −0.136 | 0.752 | −0.981 | 0.709 |

0.465 | 0.284 | −0.385 | 1.315 | |

| Diploma | 0.026 | 0.949 | −0.776 | 0.829 | −0.607 | 0.142 | −1.416 | 0.202 | |

| Bachelor | −0.224 | 0.520 | −0.907 | 0.459 | 0.207 | 0.553 | −0.478 | 0.893 | |

| Master | −0.250 | 0.510 | −0.992 | 0.493 | 0.668 | 0.080 | −0.079 | 1.415 | |

| PhD (Ref) | 0a | . | . | . | 0a | . | . | . | |

| Field of work | Medical filed | −0.680 | <0.001 | −0.997 | −0.364 | 1.060 | <0.001 | 0.736 | 1.384 |

| Non-medical field (Ref) | 0a | . | . | . | 0a | . | . | . | |

| Income level | <500JDs | 0.111 | 0.641 | −0.355 | 0.577 | 0.134 | 0.575 | −0.335 | 0.604 |

| 500–1000 JDs | −0.065 | 0.778 | −0.515 | 0.386 | 0.077 | 0.738 | −0.376 | 0.531 | |

| More than 1000 JDs (Ref) | 0a | . | . | . | 0a | . | . | . | |

| Health insurance | No | −0.247 | 0.104 | −0.545 | 0.051 | 0.612 | <0.001 | 0.309 | 0.915 |

| Yes (Ref) | 0a | . | . | . | 0a | . | . | . | |

| Have children | No | −0.623 | 0.009 | −1.092 | −0.154 | -0.044 | 0.853 | −0.514 | 0.425 |

| Yes (Ref) | 0a | . | . | . | 0a | . | . | . | |

| Medication for me | No | 0.072 | 0.673 | −0.262 | 0.406 | -0.298 | 0.084 | −0.636 | 0.040 |

| Yes (Ref) |

0a | . | . | . | 0a | . | . | . | |

| Information source | Non-Scientific source | −0.459 | 0.014 | −0.825 |

−0.092 | 0.447 | 0.017 | 0.079 | 0.816 |

| Scientific source (Ref) | 0a | . | . | . | 0a | . | . | . | |

| Attitude | Low | 0.476 | 0.001 | 0.197 | 0.755 | −0.519 | <0.001 | −0.801 | −0.238 |

| High (Ref) | 0a | . | . | . | 0a | . | . | . | |

| Chronic medication | No | 0.404 | 0.019 | 0.067 | 0.740 | −0.465 | 0.007 | −0.804 | −0.125 |

| Yes (Ref) | 0a | . | . | . | 0a | . | . | . | |

3.7. Variables associated with frequency of doctor consultation

Ordinal regression was conducted to evaluate variables associated with doctors’ consultation frequency, as evaluated by (Do you consult a doctor before using any medication?) with responses ranging from never to always. Variables that significantly increased the frequency of consulting doctors included not being on chronic medications (Coefficient estimate = 0.476; 95 %CI: 0.197– 0.755; p-value = 0.001) and having a positive SM attitude level (Coefficient estimate = 0.404; 95 %CI: 0.067– 0.740; p-value = 0.019). The variables that decreased the frequency of consulting doctors included being in medical field (Coefficient estimate = -0.680; 95 %CI: −0.997 – −0.364; p-value < 0.001), having no children (Coefficient estimate = -0.623; 95 %CI −1.092 – −0.154; p-value = 0.009) and relaying on non-scientific sources (Coefficient estimate = -0.459;95 %CI −0.825 – −0.092; p-value = 0.014) Table 4.

4. Discussion

SM has been associated with many negative consequences including inappropriate drug use, incorrect dosage, adverse drug reactions, drug interactions, delay in seeking medical advice, and risk for drug dependence or abuse (Ruiz, 2010). SM is widely practiced across several developing and developed countries worldwide (Abay and Amelo, 2010, Abdi et al., 2018, Araia et al., 2019, Mitsi et al., 2005). Nevertheless, little is known about individuals’ practice and attitudes towards SM and the associated factors, which was the aim of the current study.

The practice of SM in this study was high, with only half of the participants “always/most of the times” consulted a doctor before using any medication and 41.4 % of the participants reported that they “always/most of times” go directly to the pharmacy and order medications on their own without consulting a medical doctor or pharmacist, which is comparable with previously published study in Brazil study (Pereira et al., 2012). An earlier study reported that almost 96 % of the mothers surveyed used medications for their children without consulting a health worker (Katumbo et al., 2020). Moreover, the majority of the current study participants ordered medication from the pharmacy on their own. Nearly 72.5 % of the students participated in a study conducted in Rwanda used community pharmacy for antibiotics SM (Tuyishimire et al., 2019). Another study conducted on college students reported that 69.3 % of the participants used a pharmacy or a drug shop as a source for SM practice in Eritrea (Araia et al., 2019). An Egyptian study found that medications purchased from private pharmacies were the most used sources of SM reported by the study participants (Ghazawy et al., 2017).

Almost half of the current study participants reported using non-chronic medications twice or more during the last six months (48.2 %). Most of the participants surveyed in studies conducted in Ethiopia (Kifle et al., 2021) and India (Balamurugan and Ganesh, 2011) practiced SM more than three times in their lifetime. Another study conducted in Iran reported that the frequency of SM use ranged from one to thirty-five times per three months among the study participants (Shokrzadeh et al., 2019). Although the majority of the current study participants disagreed on SM is better than consulting a healthcare professional when the medication is prescribed for them and not for their children or anyone else, most of them self-medicated with analgesics (89.8 %) and decongestants (59.4 %). Similar results were reported in earlier studies (Adama et al., 2021, Campos et al., 2021, Gutema et al., 2011, James et al., 2006, Kumar et al., 2015, Malak and Moh’d AbuKamel, 2019, Oliveira et al., 2018, Shokrzadeh et al., 2019). Besides, most of the participants in the present study preferred SM to doctor consultation when they had symptoms of headache, flu, or fever, however, they would rather consult a doctor if they had symptoms of diabetes, hypertension, or mental disorders. A study conducted in Rwanda reported that nearly half of the participants who practiced SM used antibiotics for treating conditions such as common cold, fever, or cough (Tuyishimire et al., 2019). Headache, common cold and cough were also reported as the most common symptoms for SM practice in another study (Gutema et al., 2011). Other studies conducted in Ethiopia (Kifle et al., 2021) and India (Balamurugan and Ganesh, 2011) reported that headache and fever were the most common complaints to practice SM. Another Indian study found that common cold and fever were the most common symptoms for which SM was practiced (Kumar et al., 2015).

When asked about the reasons for SM, 84.2 % of the current study participants indicated that previous knowledge about the disease and its treatment made them practicing SM. Having sufficient medical knowledge was also recognized as a reason for SM among the participants enrolled in several other studies (Abdi et al., 2018, Alam et al., 2015, Badiger et al., 2012, Ehigiator et al., 2013, Kumar et al., 2013, Sajith et al., 2017). Increased knowledge about the medication to be purchased was also recognized among the most common reasons for SM in the present study (55.2 %), which is similar to the results reported in other studies conducted in Iran (Janatolmakan et al., 2022), India (Kumar et al., 2013, Shah et al., 2018), and Eritrea (Araia et al., 2019). In a study conducted in Bahrain, first-year medical students reported that medical knowledge increased their caution about SM and many of them would prefer to seek a prescription (James et al., 2006). Consistent with earlier research finding (Abeje et al., 2015, Aburuz et al., 2012, Beyene and Beza, 2018, Mumtaz et al., 2011), the current study participants reported that having a simple disease, which does not require physician consultation, was another reason for SM practice. These findings highlight the need for the development of public health educational programs that aim at increasing public awareness about SM and its associated risks in order to make SM practice safe and useful.

Many participants reported that they resort to SM to safe efforts, money, and time, it was previously reported ordering medications directly from the pharmacy without prescription was the most common source of SM in a study conducted in India (Balamurugan and Ganesh, 2011). Easier accessibility to community pharmacies to obtain medications in a relatively shorter time, without having to pay for a consultation in a clinic or a health center may be the reason behind SM practice, highlighting the need for healthcare professionals to advice pharmacy costumers to not use any medication without first consulting a doctor or a pharmacist or any other healthcare professional to prevent any negative impact associated with this practice.

Most of the present study participants obtained information about SM through their previous knowledge (70.8 %), followed by asking a pharmacist inside a pharmacy (58.8 %) and searching the internet (30.9 %). Comparable results were reported in an Eritrean study, where more than half of the participants enrolled reported that their academic knowledge was the source of information about medications used for SM, while only 2.6 % of them used the internet as an information source for SM (Araia et al., 2019). Moreover, a study conducted in western India reported that over 90 % of the participants from rural or urban areas chose pharmacy shops as a source of information for SM (Limaye et al., 2018). Pharmacist was also among the main sources of drug information for SM identified by university students surveyed in a Jordanian study (Malak and Moh’d AbuKamel, 2019). Similar results were also found in studies conducted in India (Balamurugan and Ganesh, 2011, Kumar et al., 2013), Egypt (Ghazawy et al., 2017), Sudan (Isameldin et al., 2020), and Iran (Shokrzadeh et al., 2019). Nowadays, with the availability of large amount of information about all fields including medical area, the accessibility to such information has become very easy, where a simple search on Google® or other website can yield a variety of information about different diseases and their treatments. In the current study, searching for symptoms, name of the medication, and name of the disease were the three most common ways by which participants searched the internet in order to choose a medication on their own. This finding raises concerns about SM threats including incorrect self-diagnosis, inappropriate drug use, drug interaction, and many others, given the increased advertising of pharmaceutical products on the internet (Burak and Damico, 2000). Since pharmacists play an important role in dispensing practice, it puts them in a critical position to increase patients’ awareness about the risk of SM and the use of medications for treating various symptoms or conditions without consulting a doctor simply by reading about it on the internet, knowing that nothing can guarantee the accuracy of the information regarding the treatment of certain diseases without doctor’s consultation.

The current study's participants showed a negative attitude towards SM, which was lower than that reported in other studies conducted in Jordan (Malak and Moh’d AbuKamel, 2019), Bahrain (James et al., 2006), India (Kayalvizhi and Senapathi, 2011), Ethiopia (Abay and Amelo, 2010), and Eritrea (Araia et al., 2019). Around 71 % of the participants in our study believed that SM is more cost-effective than approaching health care professional. A study conducted in Sudan reported that 50 % of the participants did not seek doctor’s consultation because of the high cost (Isameldin et al., 2020). Another Indian study found that many healthcare workers participated in the study agreed that SM saves consultation fees (Hanumaiah and Manjunath, 2018). Furthermore, nearly half of the current study participants thought that SM is harmless and reduced the burden on medical doctors. Most of the participants enrolled in an Indian study also agreed that SM is entirely safe (Hanumaiah and Manjunath, 2018). On the other hand, “being more careful when using self-medication” had the highest score in all attitude statements in a previous Jordanian study conducted among university students (Malak and Moh’d AbuKamel, 2019). Caution about SM was also perceived by most medical students surveyed in a Bahraini study (James et al., 2006). A study conducted in Pakistan reported that over 80 % of the participating students knew that SM can be harmful and there is a necessity of consulting a doctor before receiving any new medication (Zafar et al., 2008). These findings suggest that the increased healthcare costs and lack of knowledge and awareness about the potential harm from SM could play a role in driving the public toward approaching SM instead of doctor’s consultation in order to seek help about their medical problems. Therefore, healthcare authorities should provide less time-consuming and more cost-effective clinical services, as well as conducting various public health educational programs to raise public awareness about SM and reduce its associated risks.

Regression analysis results revealed that being in medical field significantly increased SM practice and reduced doctors’ consultation in the current study. This outcome was amply demonstrated by numerous research that revealed a substantial prevalence of SM among healthcare personnel (Babatunde et al., 2016, Mohammed et al., 2021, Simegn et al., 2020). According to a recent review, SM appears to be widely recognized among both physicians and medical students as a way to improve work performance. This raises serious concerns about the professional integrity of medicine and the possibility that the public trust in the field could be weakened because of inappropriate SM (Montgomery et al., 2011).

Consistent with earlier research findings (Pagán et al., 2006; Widayati et al., 2011), having no health insurance was associated with increased SM practice in the present study.

Relying on nonscientific sources to obtain information about SM was another factor that was significantly associated with increased SM practice and reduced doctors’ consultation in the current study. Participants who acquire information about SM from non-scientific sources may be less aware of the potential negative consequences associated with SM than those who obtain information from scientific sources, which may explain the increased SM practice and the less doctors’ consultation when compared with their counterparts. This finding emphasizes the importance of raising public knowledge of the risks that SM poses to this community.

Positive attitude towards SM and not being on chronic medications were significantly associated with reduced practice of SM and higher frequency of doctors’ consultation in the present study. A study conducted in Iran reported that incorrect attitude about the safety of SM was significantly associated with SM practice in senior medical students (MacIntosh et al., 2009). Another study conducted in Portugal showed that negative attitude towards SM was a significant predictor of the adoption of such practice among the Portuguese university students (Alves et al., 2020). Regarding chronic medications use and SM practice, consistent results were reported in an earlier study which found that patients with chronic illnesses were less likely to self-medicate than their peers (Chergaoui et al., 2022). Patients who are on chronic medications may be more concerned about the use of medications due to the information obtained from their regular medical follow up, in addition to previous experiences, when compared with those who do not use medications chronically. This may lead chronically ill patients to prefer consulting a doctor rather than self-medicate, subsequently reducing their practice of SM. Furthermore, this study found that having no children was significantly associated with lower doctors’ consultation before medications use. In comparison, more than two thirds of the mothers participated in an Egyptian study self-medicated their children without doctor’s consultation regarding common health problems such as cough, vomiting, diarrhea, and fever (El Sheshtawy et al., 2020). These findings point to the significance of educating parents about SM and the risks it poses to them and their children if used incorrectly, as well as the importance of seeking medical advice before using any medication.

5. Strengths and limitations

The current study recruited participants attending pharmacies from different locations across Jordan, which increases the confidence in the presentation of the study sample to the general Jordanian population. The present study did not only focus on SM with one class of medication such as antibiotics, it also evaluated participants’ information sources, attitudes, and SM practices. However, data of the present study was collected using self-reporting methodology, social desirability and/or recall bias may influence participants’ responses. Nevertheless, the high internal consistency of the attitude score and the high prevalence of SM reported in the current study increase the confidence of the study findings.

6. Conclusion

The present study demonstrated increased SM practice due to the wrong perceptions toward SM and the reliance on non-scientific source of information about SM practice, which could lead to several adverse consequences including incorrect use, incorrect dosage, adverse drug reactions, and dependency. Efforts should be applied to increase awareness about SM disadvantages and promote better health care practices. Moreover, strict laws should be imposed to limit the access of the general population to prescription medications.

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethical committee of Al-Zaytoonah University of Jordan.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the Zenodo repository: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7213577.

Participants consent statement

All participants in the present study signed an informed consent form.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources.

Not Applicable.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2023.01.015.

Contributor Information

Walid Al-Qerem, Email: waleed.qirim@zuj.ed.jo.

Afnan Bargooth, Email: afnanbarghooth2@gmail.com.

Anan Jarab, Email: anan.jarab@aau.ac.ae.

Amal Akour, Email: aakour@uaeu.ac.ae.

Shrouq Abu Heshmeh, Email: srabuheshmeh19@ph.just.edu.jo.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Abahussain E., Matowe L.K., Nicholls P.J. Self-Reported medication use among adolescents in Kuwait. Medical Principles Pract. 2005;14:161–164. doi: 10.1159/000084633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abay S.M., Amelo W. Assessment of self-medication practices among medical, pharmacy, and health science students in Gondar University, Ethiopia. J. Young Pharm. 2010;2:306. doi: 10.4103/0975-1483.66798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdi A., Faraji A., Dehghan F., Khatony A. Prevalence of self-medication practice among health sciences students in Kermanshah, Iran. BMC Pharmacol.. Toxicol. 2018;19 doi: 10.1186/S40360-018-0231-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abeje G., Admasie C., Wasie B. Factors associated with self medication practice among pregnant mothers attending antenatal care at governmental health centers in Bahir Dar city administration, Northwest Ethiopia, a cross sectional study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2015;20:276. doi: 10.11604/PAMJ.2015.20.276.4243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aburuz S., Al-Ghazawi M., Snyder A. Pharmaceutical care in a community-based practice setting in Jordan: where are we now with our attitudes and perceived barriers? Int J Pharm Pract. 2012;20:71–79. doi: 10.1111/J.2042-7174.2011.00164.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adama S., Wallace L.J., Arthur J., Kwakye S., Adongo P.B. Self-medication practices of pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in northern Ghana: An analytical cross-sectional study. Afr. J. Reprod. Health. 2021;25:89–98. doi: 10.29063/ajrh2021/v25i4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam N., Saffoon N., Uddin R. Self-medication among medical and pharmacy students in Bangladesh. BMC. Res. Notes. 2015;8 doi: 10.1186/S13104-015-1737-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkhawaldeh, A., Khraisat, O., 2020. Assessment of Self-Medication Use among University Students. https://doi.org/10.15640/ijn.v7n1a1.

- Alves, R.F., Precioso, J., Becoña, E., 2020. Knowledge, attitudes and practice of self-medication among university students in Portugal: A cross-sectional study. 38, 50–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1455072520965017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Araia Z.Z., Gebregziabher N.K., Mesfun A.B. Self medication practice and associated factors among students of Asmara College of Health Sciences, Eritrea: a cross sectional study. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2019;12 doi: 10.1186/S40545-019-0165-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babatunde O.A., Fadare J.O., Ojo O.J., Durowade K.A., Atoyebi O.A., Ajayi P.O., Olaniyan T. Self-medication among health workers in a tertiary institution in South-West Nigeria. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2016:24. doi: 10.11604/PAMJ.2016.24.312.8146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badiger S., Kundapur R., Jain A., Kumar A., Pattanshetty S., Thakolkaran N., Bhat N., Ullal N. Self-medication patterns among medical students in South India. Australasian Medical Journal. 2012;5:217–220. doi: 10.4066/AMJ.2012.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balamurugan, E., Ganesh, K.S., 2011. Prevalence and Pattern of Self Medication use in coastal regions of South India. BJMP 4.

- Banerjee I., Bhadury T. Self-medication practice among undergraduate medical students in a tertiary care medical college, West Bengal. J. Postgrad. Med. 2012;58:127–131. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.97175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baral, K., Dahal, M., 2019. Self-medication : Prevalence among Undergraduates in Kathmandu Valley. https://doi.org/10.9734/JAMPS/2019/v21i130122.

- Bassols A., Bosch F., Baños J.E. How does the general population treat their pain? A survey in Catalonia, Spain. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23:318–328. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(01)00415-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behzadifar M., Behzadifar M., Aryankhesal A., Ravaghi H., Baradaran H.R., Sajadi H.S., Khaksarian M., Bragazzi N.L. Prevalence of self-medication in university students: systematic review and meta-analysis. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2020;26:846–857. doi: 10.26719/EMHJ.20.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyene K.G.M., Beza S.W. Self-medication practice and associated factors among pregnant women in Addis Ababa. Ethiopia. Trop Med Health. 2018;46 doi: 10.1186/S41182-018-0091-Z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas M., Roy M.N., Manik M.I.N., Hossain M.S., Tapu S.T.A., Moniruzzaman M., Sultana S. Self medicated antibiotics in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional health survey conducted in the Rajshahi City. BMC Public Health. 2014;14 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burak L.J., Damico A. College students’ use of widely advertised medications. J. Am. Coll. Health Assoc. 2000;49:118–121. doi: 10.1080/07448480009596293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos E., Espírito-Santo M., Nascimento T.T., Martins D., Rangel L., Vianna M., Vianna D. Self-medication habits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Pub. Health. 2021;31 doi: 10.1093/EURPUB/CKAB120.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chergaoui S., Changuiti O., Marfak A., Saad E., Hilali A., Youlyouz Marfak I. Modern drug self-medication and associated factors among pregnant women at Settat city, Morocco. Front. Pharmacol. 2022;13:2870. doi: 10.3389/FPHAR.2022.812060/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouhan, K., Prasad, S.B., 2016. Self-medication and their consequences: a challenge to health professional.

- de Oliveira S.B.V., Barroso S.C.C., Bicalho M.A.C., Reis A.M.M. Profile of drugs used for self-medication by elderly attended at a referral center. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2018;16:eAO4372. doi: 10.31744/EINSTEIN_JOURNAL/2018AO4372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, R., Raja, D., Anuradha, R., Dcruze, L., Jain, T., Sivaprakasam, P., 2017. Self-medication practices versus health of the community Self-medication practices versus health of the community. 10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20173169. [DOI]

- Ehigiator O., Azodo C.C., Ehizele A.O., Ezeja E.B., Ehigiator L., Madukwe I.U. Self-medication practices among dental, midwifery and nursing students. Eur. J. Gen. Dent. 2013;2:54–57. doi: 10.4103/2278-9626.106813. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El Sheshtawy O.M., Arafa N.M., Deyab B.A. Self-Medication practices among mothers having children under five-years. Egyptian J. Health Care. 2020;11:383–399. doi: 10.21608/EJHC.2020.132995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elayeh E., Akour A., Haddadin R.N. Prevalence and predictors of self-medication drugs to prevent or treat COVID-19: Experience from a Middle Eastern country. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021;75 doi: 10.1111/IJCP.14860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghazawy E.R., Hassan E.E., Mohamed E.S., Emam S.A. Self-Medication among Adults in Minia, Egypt: a cross sectional community-based study. Health N Hav. 2017;9:883–895. doi: 10.4236/HEALTH.2017.96063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoryan L., Burgerhof J.G.M., Degener J.E., Deschepper R., Lundborg C.S., Monnet D.L., Scicluna E.A., Birkin J., Haaijer-Ruskamp F.M. Determinants of self-medication with antibiotics in Europe: the impact of beliefs, country wealth and the healthcare system. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008;61:1172–1179. doi: 10.1093/JAC/DKN054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutema G.B., Gadisa D.A., Kidanemariam Z.A., Berhe D.F., Berhe A.H., Hadera M.G., Hailu G.S., Abrha N.G., Yarlagadda R., Dagne A.W. Self-medication practices among health sciences students: the case of mekelle university. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2011;1:183–189. [Google Scholar]

- Hanumaiah V., Manjunath H. Study of knowledge, attitude and practice of self medication among health care workers at MC Gann Teaching District hospital of Shivamogga, India. Int. J. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. 2018;7:1174. doi: 10.18203/2319-2003.IJBCP20182102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S.H., Spadaro D., West D., Tak S.H. Patient valuation of pharmacist services for self care with OTC medications. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2005;30:193–199. doi: 10.1111/J.1365-2710.2005.00625.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isameldin E., Saeed A.A., Mousnad M.A. Self-medication Practice among patients living in Soba-Sudan. Health Primary Care. 2020;4 doi: 10.15761/HPC.1000179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- James H., Handu S.S., al Khaja, Otoom S., Sequeira R.P. Evaluation of the knowledge, attitude and practice of self-medication among first-year medical students. Med. Princ. Pract. 2006;15:270–275. doi: 10.1159/000092989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janatolmakan M., Abdi A., Andayeshgar B., Soroush A., Khatony A. The reasons for self-medication from the perspective of Iranian nursing students: a qualitative study. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2022;2022 doi: 10.1155/2022/2960768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katumbo A.M., Tshiningi T.S., Sinanduku J.S., Mudisu L.K., Mwadi P.M., Mukuku O., Luboya O.N., Malonga F.K. The practice of self-medication in children by their mothers in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo. J. Adv. Pediatrics Child Health. 2020;3:027–031. doi: 10.29328/JOURNAL.JAPCH.1001014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kayalvizhi S., Senapathi R. Evaluation of the perception, attitude and practice of self medication among business students in 3 select cities, South India | Semantic Scholar. Int. J. Enterprise Innovation Manage. Studies. 2011;1:40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kifle Z.D., Mekuria A.B., Anteneh D.A., Enyew E.F. Self-medication Practice and Associated Factors among Private Health Sciences Students in Gondar Town, North West Ethiopia. A Cross-sectional Study. Inquiry (United States) 2021;58 doi: 10.1177/00469580211005188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krejcie R., Morgan D. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970;30:607–610. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N., Kanchan T., Unnikrishnan B., Rekha T., Mithra P. Perceptions and Practices of Self-Medication among Medical Students in Coastal South India. Population Health and Preventive Medicine. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V., Mangal A., Yadav G., Raut D., Singh S. Prevalence and pattern of self-medication practices in an urban area of Delhi, India. Medical Journal of Dr. D.Y. Patil University. 2015;8:16–20. doi: 10.4103/0975-2870.148828. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Limaye D., Limaye V., Fortwengel G., Krause G. Self-medication practices in urban and rural areas of western India: a cross sectional study. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health. 2018;5:2672. doi: 10.18203/2394-6040.IJCMPH20182596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lv B., Zhou Z., Xu G., Yang D., Wu L., Shen Q., Jiang M., Wang X., Zhao G., Yang S., Fang Y. Knowledge, attitudes and practices concerning self-medication with antibiotics among university students in western China. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2014;19:769–779. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacIntosh C., Weiser C., Wassimi A., Reddick J., Scovis N., Guy M., Boesen K. Attitudes toward and factors affecting implementation of medication therapy management services by community pharmacists. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2009;49:26–30. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2009.07122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malak M.Z., Moh’d AbuKamel A. Self-medication practices among university students in Jordan. Malaysian J. Medicine Health Sci. 2019;15:112–119. [Google Scholar]

- Mamo S., Ayele Y., Dechasa M. Self-Medication practices among community of Harar City and its surroundings, Eastern Ethiopia. J. Pharm. (Cairo) 2018;2018:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2018/2757108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathias, E.G., Anjalin, D., Prabhu, S., 2020. Self-Medication Practices among the Adolescent Population of South Karnataka, India 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mitsi G., Jelastopulu E., Basiaris H., Skoutelis A., Gogos C. Patterns of antibiotic use among adults and parents in the community: a questionnaire-based survey in a Greek urban population. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2005;25:439–443. doi: 10.1016/J.IJANTIMICAG.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed S.A., Tsega G., Hailu A.D. Self-medication practice and associated factors among health care professionals at debre markos comprehensive specialized hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2021;13:19–28. doi: 10.2147/DHPS.S290662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery A.J., Bradley C., Rochfort A., Panagopoulou E. A review of self-medication in physicians and medical students. Occup. Med. (Chic Ill) 2011;61:490–497. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqr098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumtaz Y., Jahangeer S.M.A., Mujtaba T., Zafar S., Adnan S. Self medication among university students of Karachi. J. Liaquat Univ. Medical Health Sci. 2011;10:102–105. [Google Scholar]

- Nusair M.B., Al-azzam S., Alhamad H., Momani M.Y. The prevalence and patterns of self-medication with antibiotics in Jordan: a community-based study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021;75 doi: 10.1111/IJCP.13665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagán J.A., Ross S., Yau J., Polsky D. Self-medication and health insurance coverage in Mexico. Health Policy. 2006;75:170–177. doi: 10.1016/J.HEALTHPOL.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira C.M., Alves V.F., Gasparetto P.F., Carneiro D.S., de Carvalho D.D.G.R., Valoz F.E.F. Self-medication in health students from two Brazilian universities. RSBO. 2012;9:361–367. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz M. Risks of self-medication practices. Curr. Drug Saf. 2010;5:315–323. doi: 10.2174/157488610792245966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sado E., Kassahun E., Bayisa G., Gebre M., Tadesse A., Mosisa B. Epidemiology of self – medication with modern medicines among health care professionals in Nekemte town, western Ethiopia. BMC. Res. Notes. 2017;1–5 doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2865-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajith M., Suresh S.M., Roy N.T., Pawar, Dr.A., Self-Medication practices among health care professional students in a tertiary care hospital, Pune. Open Public Health J. 2017;10:63–68. doi: 10.2174/1874944501710010063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sambakunsi C.S., Småbrekke L., Varga C.A., Solomon V., Mponda J.S. Knowledge, attitudes and practices related to self-medication with antimicrobials in Lilongwe, Malawi. Malawi Medical J. 2019;31:225. doi: 10.4314/MMJ.V31I4.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah H., Patel R., Nayak S., Patel H., Sharma D. A questionnaire-based cross-sectional study on self-medication practices among undergraduate medical students of GMERS Medical College, Valsad, Gujarat. Int. J. Med. Sci. Public Health. 2018;1 doi: 10.5455/IJMSPH.2018.0101324012018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shokrzadeh M., Hoseinpoor R., Jafari D., Jalilian J., Shayeste Y. Self-Medication practice and associated factors among adults in Gorgan, North of Iran. Iranian J. Health Sci. 2019;7:29–38. doi: 10.18502/JHS.V7I2.1062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simegn W., Dagnew B., Dagne H. Self-Medication practice and associated factors among health professionals at the University of Gondar comprehensive specialized hospital: a cross-sectional study. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:2539. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S257667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripković K., Nešković A., Janković J., Odalović M. Predictors of self – medication in Serbian adult population : cross – sectional study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s11096-018-0624-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuyishimire J., Okoya F., Adebayo A.Y., Humura F., Lucero-Prisno D.E. Assessment of self-medication practices with antibiotics among undergraduate university students in Rwanda. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2019;33 doi: 10.11604/PAMJ.2019.33.307.18139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widayati A., Suryawati S., De Crespigny C., Hiller J.E. Self medication with antibiotics in Yogyakarta City Indonesia: A cross sectional population-based survey. BMC. Res. Notes. 2011;4:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-491/TABLES/4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafar S.N., Syed R., Waqar S., Zubairi A.J., Vaqar T., Shaikh M., Yousaf W., Shahid S., Saleem S. Self-medication amongst university students of Karachi: prevalence, knowledge and attitudes. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2008;58:214–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the Zenodo repository: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7213577.