Abstract

Objective

The incidence of headaches with blood stasis syndrome has increased. Herein, we used scientific, statistical methods to explore the medication rules of Chinese herbal medicines (CHMs) to treat headaches with blood stasis syndrome and provide a scientific and reliable theoretical basis for clinical treatment.

Methods

First, we retrieved studies related to CHMs used to treat headaches with blood stasis syndrome from the VIP, CNKI, Wanfang, and PubMed databases. We used Excel 2013 to establish a database and SPSS Modeler 18.0 and SPSS 25.0 to conduct frequency, association rule, and cluster analyses.

Results

Based on the screening criteria, we retrieved 126 CHM prescriptions for headaches with blood stasis syndrome involving 149 herbs. The top three high-frequency herbs were Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong), Angelica Sinensis Radix (Danggui), and Carthami Flos (Honghua). Blood-activating and stasis-eliminating herbs were the most frequently used herb efficacy categories. The liver meridian represented the most frequently used herb meridian tropism. The properties and taste of herbs were mainly warm and bitter, respectively. We obtained 21 association rules and five new clusters. The Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) and Angelica Sinensis Radix (Danggui) herb pair had the strongest correlation.

Conclusion

We analyzed published CHM prescriptions for headaches with blood stasis syndrome and eliminated factors that did not reach an agreement, such as herb dosage. We used different data mining and analysis methods to ensure that the method and process were scientific and the conclusion was reliable, comprising a valuable reference for selecting herbs for the clinical treatment of headaches with blood stasis syndrome. The Xuefu Zhuyu Decoction (XFZYD) was the primary CHM prescription for headaches with blood stasis syndrome. Xiaoyao San (XYS) and Buyang Huanwu Decoction (BYHWD) might also be clinical references for treatment selection. Meridian-inducing and insect herbs might be used according to syndromes.

Keywords: Headache, Blood stasis syndrome, Chinese herbal medicine, Medication rule, Data mining

1. Introduction

Headache is a common clinical and spontaneous symptom that manifests as overall or localized swelling and pain of the head. Often it may also be accompanied by nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and visual disturbances [1]. Headache occurs predominantly in patients aged 20–40 years [2]. The Global Burden of Disease 2017 showed that headache is the second most common disease and one of the top four major causes of chronic disease [3]. However, the pathogenesis of headaches from a Western medical perspective is unclear. In the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition (ICHD-3) [4], the International Headache Society (IHS) divides primary headache into four categories: migraine, tension-type headache, trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias, and other primary headache disorders. Tension-type is the most common headache. Recently, the trigeminal vascular theory has received extensive attention in describing the pathogenesis of migraine. Typically, neurotransmitters at the ends of trigeminal afferent fibers, such as calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), substance P, and neurokinin A (NKA), act on intracranial and extracranial vessels, causing vascular dilation and leading to headaches [5,6]. Tension-type headaches are associated with peripheral sensitization, cranial muscle tenderness, abnormal muscle activity, abnormal pain modulation of the central nervous system, and disturbances in the metabolism of cytokines and inflammatory mediators [7]. However, due to the unclear pathogenesis, pain relief is usually the primary goal of Western medicine in the treatment of headaches. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as Aspirin and Ibuprofen, are the first nonspecific choice, while Triptans are the first specific choice [8]. Although these drugs are effective for pain relief, they have common side effects, such as neurological and gastrointestinal adverse effects, stroke, and risk of bleeding [9,10]. In addition, the lack of headache treatment management may lead to the overuse of pain medications [11].

Blood stasis (Xueyu in Chinese) is defined as poor circulation or stagnation of blood flow and the formation of bruises [12]. This concept does not refer to a specific disease but a symptom diagnosed in the traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). The main clinical features of blood stasis are fixed pain (worse at night), subcutaneous hematoma or purpura, and cyanosis of the face and lips [13]. The concept of headaches with blood stasis syndrome was first proposed by Qingren Wang from the Qing Dynasty in the Corrections on the Errors of Medical Works [14]. In this definition, abnormal blood flow can lead to headaches with blood stasis syndrome because of problems such as Qi and blood deficiency, Qi stagnation, cold coagulation, turbid phlegm, and toxic heat [15]. From modern medical and clinical studies, the pathological basis of headaches with blood stasis syndrome comprises dysfunctional micro-circulation related to irregular hemorheology, hemodynamics, and scar tissue formation [13,16,17]. Hence, the main treatment principle should be to activate the blood and remove blood stasis.

Nowadays, TCM doctors have different views on how to treat headaches with blood stasis syndrome. For example, some experts believe that wind herbs should be used more frequently based on blood-activating and stasis-eliminating properties [18,19]. In contrast, others believe that the therapeutic principles of clearing heat, external drainage, and regulating Qi are equally important as activating blood circulation and resolving blood stasis [20]. Therefore, statistical methods are essential to explore the rules of CHMs for headaches with blood stasis syndrome.

Data mining is an information processing technique widely used to obtain rules from big data, including frequency statistics, cluster analysis, and association rules, which reflect mapping relationships between multidimensional data [21]. Data mining for clinical prevention and treatment in TCM could help explore previous findings, discover potential rules, and guide future clinical practice.

After reviewing various studies, we found that the current research on headaches with blood stasis syndrome only comprises clinical observations and case reports, lacking systematic analysis and rule summaries. Therefore, it is crucial to explore and summarize the appropriate medication rules through scientific and rigorous statistical methods, which is the main goal and strength of our current study. In this study, we used data mining from the relevant literature over the past 20 years to explore the success of CHM in the treatment of blood stasis headache and to provide a practical and effective theoretical basis for clinical treatment.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data collection

We searched three Chinese databases (VIP, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and Wanfang data) and one English database (PubMed) from January 1st, 2000, to May 1st, 2021. We restricted the language to English or Chinese. The search strategy and keywords are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy for literature on CHM in headaches with blood stasis syndrome.

| Search Strategy | Keywords Content |

|---|---|

| A.Search strategy to locate “headache” | 1 headache |

| 2 headache disorders | |

| 3 primary headache | |

| 4 migraine | |

| 5 tension-type headache | |

| 6 trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias | |

| 7 cephalalgias | |

| B.Search strategy to locate “blood stasis” | 8 blood stasis |

| 9 stasis of blood |

* This search strategy was used in all databases.

2.2. Selection criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) using CHM prescription for the treatment of blood stasis type headache. Participants should be diagnosed with primary headaches according to the ICHD-3 [4] and blood stasis syndrome symptoms following the diagnosis and therapeutic effect criteria for internal diseases and syndromes of TCM [22]. Studies should contain at least one of the four outcomes: pain intensity, duration, frequency, and recurrence of headaches, with clear and good results.

2.2.2. Exclusion criteria

We excluded case reports, animal experiments, retrospective studies, literature reviews, and systematic reviews. Additionally, we excluded studies without specific CHM compositions or that used CHM treatment only as a control group, as well as studies without better outcomes with CHM treatment.

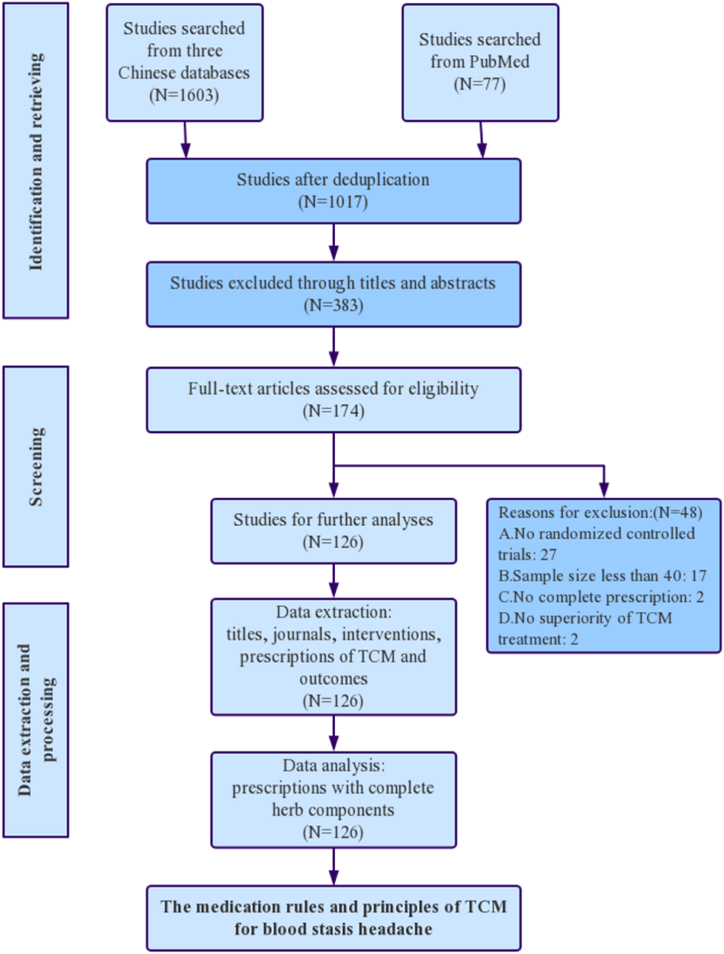

2.3. Screening process

After reading the titles and abstracts, H. Yang identified the non-repetitive literature and excluded irrelated studies, such as case reports, animal experiments, retrospective studies, literature reviews, and systematic reviews. Then, G. Liu read the full text of the remaining studies and conducted the secondary screening. In this section, 27 non-RCTs, 17 studies with sample sizes <40, 2 studies without full prescriptions, and 2 studies without TCM treatment superiority were excluded. Finally, Z. Zhang, G. Liu, and H. Yang checked the documents that met the above screening criteria. Differences in the literature selection process were resolved through joint discussion. Finally, we selected 126 herbal prescriptions. The screening process is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Screening process.

2.4. Data processing

2.4.1. Data normalization

Since many synonyms were available for TCM herbs, we unified and normalized them before statistical analyses. The standards for TCM herb name normalization were verified in the 2020 edition of The Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China [23] and The Dictionary of Chinese Herbal Medicine [24]. We analyzed CHM prescriptions without considering different herbal doses because of the difficulty of unifying and standardizing herbal doses.

2.4.2. Statistical analyses

We used Microsoft Excel 2017 (Microsoft Excel, RRID: SCR_016137) to establish a database to record literature names and sources, interventions, and CHM prescriptions with herb compositions and efficacy results. Then, we analyzed the frequency, properties, tastes, meridian tropisms, and drugs.

Association rule analysis is a data mining approach commonly used in clinical medicine. It inferred the probability of related diseases and random events by using frequent associations between combinations of variables [25]. Here, we used support, confidence, and lift as indicators to measure the strength of associations. Support comprised the probability of the simultaneous occurrence of two items. Confidence comprehended the probability of occurrence of the last item under the former item. The lift reflected the correlation between A and B. For lift >1, the higher the value, the stronger the positive correlation. In contrast, for lift <1, the lower the value, the stronger the negative correlation. A lift = 1 indicates no association. We used SPSS Modeler 18.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, RRID: SCR_019096) to analyze the association rules of herbs.

Systematic cluster analysis is an exploratory approach without established standards during classification. It automatically classifies the sample data and provides new data clusters. Specific cluster sets are further analyzed by observing the characteristics of each kind of data. Cluster analysis has been previously used for data mining in TCM, mainly to determine the compatibility law between drugs and identify the combination rules of different CHM prescriptions [26]. Here, we conducted a systematic cluster analysis of herbs using SPSS 25.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, RRID: SCR_019096).

3. Results

3.1. Frequency analysis

After literature search and collection, we obtained 1680 studies and included 126 after screening according to the above criteria. Among the included studies, 11,511 cases and 126 prescriptions, including 149 herbs, were reported. The cumulative herb frequency was 1610. Among the 149 herbs, 23 (15.44%) herbs presented a frequency ≥20, classified as high-frequency, comprising 62.11% of the cumulative frequency (Table 2). Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) was the most frequent herb (111 times - 88.1%) for headaches with blood stasis syndrome. Angelicae Sinensis Radix (Danggui), Carthami Flos (Honghua), Persicae Semen (Taoren), and Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Chishao) were also frequently used (frequency >50%).

Table 2.

High-frequency herbs used to treat headaches with blood stasis syndrome.

| No. | Herb | Properties | Tastes | Meridian Tropisms | Frequency | aProportion/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) | Warm | Pungent | Liver/Gallbladder/Pericardium | 111 | 88.10 |

| 2 | Angelicae Sinensis Radix (Danggui) | Warm | Pungent/Sweet | Liver/Heart/Spleen | 73 | 57.94 |

| 3 | Carthami Flos (Honghua) | Warm | Pungent | Heart/Liver | 69 | 54.76 |

| 4 | Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Chishao) | Cold | Bitter | Liver | 66 | 52.38 |

| 5 | Persicae Semen (Taoren) | Mild | Bitter/Sweet | Heart/Liver/Large intestine | 63 | 50.00 |

| 6 | Bupleuri Radix (Chaihu) | Cold | Pungent/Bitter | Liver/Gallbladder/Lung | 52 | 41.27 |

| 7 | Angelicae Dahuricae Radix (Baizhi) | Warm | Pungent | Stomach/Large intestine/Lung | 51 | 40.48 |

| 8 | Glycyrrhizae Radix Et Rhizoma (Gancao) | Mild | Sweet | Heart/Lung/Spleen/Stomach | 50 | 39.68 |

| 9 | Scorpio (Quanxie) | Mild | Pungent | Liver | 49 | 38.89 |

| 10 | Scolopendra (Wugong) | Warm | Pungent | Liver | 41 | 32.54 |

| 11 | Astragali Radix (Huangqi) | Warm | Sweet | Lung/Spleen | 39 | 30.95 |

| 12 | Puerariae Lobatae Radix (Gegen) | Cool | Pungent/Sweet | Spleen/Stomach/Lung | 36 | 28.57 |

| 13 | Gastrodiae Rhizoma (Tianma) | Mild | Sweet | Liver | 33 | 26.19 |

| 14 | Paeoniae Radix Alba (Baishao) | Cold | Bitter/Sour | Liver/Spleen | 32 | 25.40 |

| 15 | Asari Radix Et Rhizoma (Xixin) | Warm | Pungent | Heart/Lung/Kidney | 32 | 25.40 |

| 16 | Notopterygii Rhizoma Et Radix (Qianghuo) | Warm | Pungent/Bitter | Bladder/Kidney | 31 | 24.60 |

| 17 | Pheretima (Dilong) | Cold | Salty | Liver/Spleen/Bladder | 28 | 22.22 |

| 18 | Viticis Fructus (Manjingzi) | Cold | Pungent/Bitter | Bladder/Liver/Stomach | 28 | 22.22 |

| 19 | Corydalis Rhizoma (Yanhusuo) | Warm | Pungent/Bitter | Liver/Spleen | 27 | 21.43 |

| 20 | Salviae Miltiorrhizae Radix Et Rhizoma (Danshen) | Cold | Bitter | Heart/Liver | 26 | 20.63 |

| 21 | Ligustici Rhizoma Et Radix (Gaoben) | Warm | Pungent | Bladder | 22 | 17.46 |

| 22 | Achyranthis Bidentatae Radix (Niuxi) | Mild | Bitter/Sweet/Sour | Liver/Kidney | 21 | 16.67 |

| 23 | Uncariae Ramulus Cum Uncis (Gouteng) | Cool | Sweet | Liver/Pericardium | 20 | 15.87 |

The proportion refers to the percentage of a herb's frequency in the total frequency of all herbs.

3.2. Properties, tastes, and meridian tropisms

The total frequency of herb properties was 149. Warm herbs were used 61 times (40.94%), followed by cold [44 times (29.53%)] and mild [34 times (22.82%)] herbs. Cool and hot herbs were rarely used (Fig. 2a). The total frequency of herb tastes was 239. Bitter herbs were used 74 times (30.96%), comprising the highest frequency, followed by pungent [71 times (29.71%)] and sweet [62 times (25.94%)] herbs (Fig. 2b). The total frequency of herb meridian tropisms was 363, with the liver meridian as the most frequent [82 times (22.59%)]. Herbs were also frequently used in the lung, spleen, stomach, heart, and kidney meridians (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

a. Herb properties of CHMs for headaches with blood.

b. Herb tastes of CHMs for headaches with blood.

c. Herb meridian tropisms of CHMs for headaches with blood stasis syndrome.

3.3. Herb categories analysis

CHMs have different curative effects when used in diverse combinations. Accordingly, they can be divided based on their characteristic curative effects [27]. The total frequency and proportions of each herbal category are presented in Fig. 3. Blood-activating and stasis-eliminating herbs were the most frequently used [372 times - 23.11% of the total (1610 times)], followed by exterior-relieving (344 times; 21.37%), deficiency-tonifying (290 times; 18.01%), and liver-wind calming (218 times; 13.54%) herbs.

Fig. 3.

Categories frequency for CHMs for headaches with blood stasis syndrome.

3.4. Association rule analysis and network display

We applied the Apriori algorithm to conduct the association rule analysis on the 149 herbs. We obtained 21 herb association rules with support ≥30%, confidence ≥90%, and lift >1. The support ≥30% means that the occurrence probability of the former and the last item at the same time must be ≥ 30%. The confidence ≥90% indicates that the occurrence probability of the last item under the former item must be ≥ 90%. The lift >1 means that the association rules are positively correlated. Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) and Angelicae Sinensis Radix (Danggui) had the strongest association (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association rules of CHMs for headaches with blood stasis syndrome.

| No. | Former item | Latter item | Support/% | Confidence/% | Lift |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) | Angelicae Sinensis Radix (Danggui) | 57.94 | 94.52 | 1.07 |

| 2 | Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) | Carthami Flos (Honghua) | 53.17 | 97.01 | 1.10 |

| 3 | Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) | Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Chishao) | 52.38 | 90.91 | 1.03 |

| 4 | Carthami Flos (Honghua) | Persicae Semen (Taoren) | 50.00 | 92.06 | 1.73 |

| 5 | Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) | Persicae Semen (Taoren) | 50.00 | 93.65 | 1.06 |

| 6 | Carthami Flos (Honghua) | Persicae Semen (Taoren) and Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) | 46.83 | 94.92 | 1.78 |

| 7 | Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) | Persicae Semen (Taoren) and Carthami Flos (Honghua) | 46.03 | 96.55 | 1.10 |

| 8 | Persicae Semen (Taoren) | Carthami Flos (Honghua) and Angelicae Sinensis Radix (Danggui) | 41.27 | 92.31 | 1.85 |

| 9 | Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) | Carthami Flos (Honghua) and Angelicae Sinensis Radix (Danggui) | 41.27 | 96.15 | 1.09 |

| 10 | Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) | Bupleuri Radix (Chaihu) | 40.48 | 94.12 | 1.07 |

| 11 | Persicae Semen (Taoren) | Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Chishao) and Carthami Flos (Honghua) | 40.48 | 92.16 | 1.84 |

| 12 | Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) | Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Chishao) and Carthami Flos (Honghua) | 40.48 | 98.04 | 1.11 |

| 13 | Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) | Glycyrrhizae Radix Et Rhizoma (Gancao) | 39.68 | 98.00 | 1.11 |

| 14 | Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) | Angelicae Dahuricae Radix (Baizhi) | 39.68 | 98.00 | 1.11 |

| 15 | Carthami Flos (Honghua) | Persicae Semen (Taoren) and Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Chishao) | 38.89 | 95.92 | 1.80 |

| 16 | Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) | Persicae Semen (Taoren) and Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Chishao) | 38.89 | 95.92 | 1.09 |

| 17 | Carthami Flos (Honghua) | Persicae Semen (Taoren) and Angelicae Sinensis Radix (Danggui) | 38.89 | 97.96 | 1.84 |

| 18 | Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) | Persicae Semen (Taoren) and Angelicae Sinensis Radix (Danggui) | 38.89 | 95.92 | 1.09 |

| 19 | Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) | Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Chishao) and Angelicae Sinensis Radix (Danggui) | 36.51 | 95.65 | 1.09 |

| 20 | Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) | Scolopendra (Wugong) | 32.54 | 90.24 | 1.02 |

| 21 | Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) | Astragali Radix (Huangqi) | 30.95 | 92.31 | 1.05 |

Furthermore, we used SPSS Modeler 18.0 to generate a network diagram of association rules. In the network diagram, the thicker the lines, the stronger the correlation between herbs, whereas the thinner the lines, the weaker the correlation. We detected strong correlations for Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) and Angelicae Sinensis Radix (Danggui); Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) and Carthami Flos (Honghua); Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Chishao) and Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong); Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) and Persicae Semen (Taoren); Carthami Flos (Honghua) and Persicae Semen (Taoren). These results suggested that Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong), Angelicae Sinensis Radix (Danggui), Carthami Flos (Honghua), Persicae Semen (Taoren), and Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Chishao) were the most important CHMs to treat headaches with blood stasis syndrome (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Network diagram of CHMs for headaches with blood stasis syndrome.

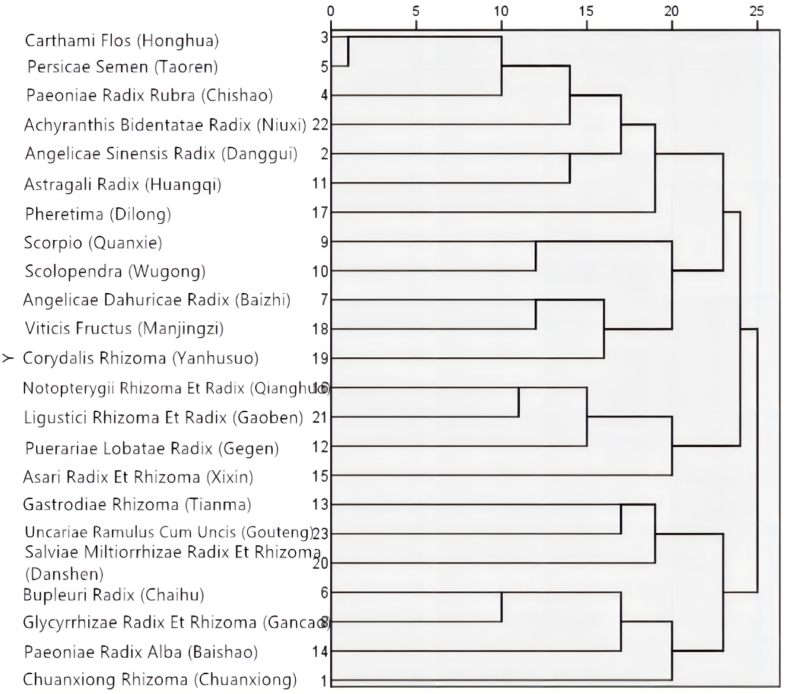

3.5. Cluster analysis

Furthermore, we selected the 23 herbs used more than 20 times and conducted systematic cluster analysis with SPSS 25.0. This approach can indicate the compatibility and combination rules of different CHMs [26]. Herein, five new clusters were referenced for treatment (Fig. 5). Cluster 1 included Carthami Flos (Honghua), Persicae Semen (Taoren), Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Chishao), Achyranthis Bidentatae Radix (Niuxi), Angelicae Sinensis Radix (Danggui), Astragali Radix (Huangqi), and Pheretima (Dilong). Cluster 2 comprised Scorpio (Quanxie), Scolopendra (Wugong), Angelicae Dahuricae Radix (Baizhi), Viticis Fructus (Manjingzi), and Corydalis Rhizoma (Yanhusuo). Cluster 3 contained Notopterygii Rhizoma Et Radix (Qianghuo), Ligustici Rhizoma Et Radix (Gaoben), Puerariae Lobatae Radix (Gegen), and Asari Radix Et Rhizoma (Xixin). Cluster 4 included Gastrodiae Rhizoma (Tianma), Uncariae Ramulus Cum Uncis (Gouteng), and Salviae Miltiorrhizae Radix Et Rhizoma (Danshen). Cluster 5 comprised Bupleuri Radix (Chaihu), Glycyrrhizae Radix Et Rhizoma (Gancao), Paeoniae Radix Alba (Baishao), and Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong).

Fig. 5.

Tree diagram from cluster analysis of CHMs for headaches with blood stasis syndrome.

The herbs in cluster 1 represent the Buyang Huanwu Decoction (BYHWD) and the Xuefu Zhuyu Decoction (XFZYD). Herbs in clusters 2 and 4 are related to wind and pain-relieving effects. Meanwhile, cluster 3 included pungent exterior-relieving herbs with meridian-inducing effects. Finally, herbs in cluster 5 represent Xiaoyao San (XYS).

4. Discussion

Various studies have confirmed that herbs have been widely used in the treatment of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, and they have the effects of promoting blood circulation and anti-thrombotic, Qi-regulating, pain-relieving, blood-tonifying, and Qi-tonifying. The effective effects of the first eight HF herbs in the article also validate the results of previous studies. Why are they effective? Their active ingredients and related mechanisms are shown in Appendix A (Online Supplementary Appendix). We found that warm and cold herbs were the most frequently used with a predominantly bitter, spicy, and sweet taste. In TCM theory, herbs are summarized by four properties and five tastes, and ancient TCM books put forward the idea of selecting herbs based on their properties [28]. Additionally, molecular network-level studies have shown that bitter herbs can affect the cell cycle, blood circulation, and other processes. In contrast, cold herbs promote vasoconstriction and coagulation, while warm herbs regulate platelet activation, improve blood circulation and relieve pain [29]. Among high-frequency herbs, pungent, such as Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong), and sweet, such as Angelicae Sinensis Radix (Danggui), herbs might be used to treat headaches with blood stasis syndrome through the above effects.

In the frequency analysis of meridian tropisms, we found that the liver meridian herbs were the most frequently used. Many modern physicians treat headaches using the liver meridian [30,31]. In Chinese medicine, liver meridian herbs can treat blood stasis and are effective in treating pathological factors such as qi stagnation, blood deficiency, and liver depression. Our study found that the first six high-frequency herbs belong to the liver meridian, which is consistent with the meridian tropical frequency analysis. Category frequency analysis shows that blood-activating herbs are most commonly used to treat blood stasis type headaches. In addition, there are various herbs that assist blood stasis evidence headaches. Exterior-relieving herbs have analgesic effects [32] and can be used as specific headache-guiding medical herbs [33]. Deficiency-tonifying herbs play a tonic role without damaging health. Liver-wind calming herbs can treat insomnia, dreaminess, and anxiousness caused by recurrent headaches. Additionally, the insects in this category have strong analgesic effects [34] and are commonly used for intractable headaches [35]. The cooperation of these four herb categories was evident and complementary, leading to better therapeutic effects.

The association rule analysis showed that Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) and Angelicae Sinensis Radix (Danggui) (Table 3 - NO.1) had the highest support degree. We found a strong correlation between Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) and Carthami Flos (Honghua) (Table 3 - NO.2); Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) and Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Chishao) (Table 3 - NO.3); Carthami Flos (Honghua) and Persicae Semen (Taoren) (Table 3 - NO.4); and Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) and Persicae Semen (Taoren) (Table 3 - NO.5). Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) and Angelicae Sinensis Radix (Danggui) (Table 3 - NO.1) are a common clinical herb pair. Their combination, Xiongzhi San, first appeared in the Song Dynasty and has been developed into various Chinese medicine patents [36]. Additionally, their extract can significantly improve the rheology and coagulation function of acute blood stasis rats [37]. The combination of Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong) and Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Chishao) is significantly more efficient than each herb alone [38], improving hemorheology and myocardial ischemia and protecting the brain and nerves (Table 3-NO.3), which demonstrates their complementarity [39]. Carthami Flos (Honghua) and Persicae Semen (Taoren) (Table 3-NO.4) can promote blood circulation and treat blood stasis [40]. Hence, combining these two herbs can eliminate blood stasis while benefiting blood circulation, amplifying the removal of blood stasis [41]. Besides, since these herbs can be foods or medicines, they are widely used and highly accepted [42].

In the cluster analysis, Cluster 1 includes BYHWD, which is commonly used in the treatment of post-stroke conditions, such as Qi deficiency and blood stasis syndrome. Modern pharmacological studies have shown that BYHWD can improve hemorheology and reperfusion injury and has anti-thrombosis, anti-atherosclerosis, and anti-cerebral ischemia effects [43]. Also, BYHWD has therapeutic effects on cerebrovascular diseases through multiple pathways and targets [44] and can treat headaches [45]. For example, Zhang showed that BYHWD could relieve headache symptoms by regulating endothelin (ET) and CGRP [46]. However, Astragali Radix (Huangqi) has the largest dose in BYHWD, while the dose of blood-activating herbs is smaller. According to the association rule analysis, the correlation between Astragali Radix (Huangqi) and other high-frequency herbs and herb couples was not strong. Moreover, the combination of Carthami Flos (Honghua), Persicae Semen (Taoren), Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Chishao), and Angelicae Sinensis Radix (Danggui), all from XFZYD, indicated that Astragali Radix (Huangqi) compatibility was not preferred. Additionally, BYHWD takes a long time to take effect [47]. Since headache is a recurrent disease, patients generally comply poorly with long-term medications. Thus, it is challenging to achieve the best therapeutic effects using BYHWD. In summary, BYHWD can be used as a reference for the clinical treatment of headaches with blood stasis syndrome or long-term intractable headaches, but it might not be the best choice for common headaches with blood stasis syndrome.

Cluster 2 herbs reflect the TCM view of treating symptoms and underlying causes. Given the etiology and pathogenesis of headaches with blood stasis syndrome, wind herbs, and analgesics can timely relieve pain symptoms. For example, Scorpio (Quanxie) and Scolopendra (Wugong) are liver-wind calming herbs and have good efficacy in treating headaches [48]. Ngelicae Dahuricae Radix (Baizhi) and Viticis Fructus (Manjingzi) have exterior-relieving effects, suitable for head and face diseases, with evident pain-relieving effects [49]. Corydalis Rhizoma (Yanhusuo) can promote blood circulation, regulate the Qi, and have other analgesic effects. The composition of cluster 3 suggested that specific herbs for headaches can be selected for different pain locations. Herbs with a pungent taste have better effects and might be preferred in clinical practice. In addition, modern physicians emphasize applying specific herbs to treat headaches [50,51].

Herbs in cluster 5 composed the XYS prescription. They mainly belong to the liver meridian and can smooth the liver and resolve depression. This prescription has soothing effects on irritability, anxiety, depression [52,53], and other harmful emotions caused by liver Qi-stagnation. Thus, XYS is also often used in gynecological menstruation. Moreover, XYS has good effects on clinical headache treatments [[54], [55], [56]]. Modern pharmacology studies have shown that XYS and similar prescriptions play an antidepressant role by regulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, intervening in the inflammatory reaction process, affecting autophagy, and alleviating neuronal apoptosis [57]. These results suggest that more XYS prescriptions can be used to treat patients with a bad mood due to recurrent headaches.

Based on the frequency, association rule, and cluster analyses, Angelicae Sinensis Radix (Danggui), Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong), Carthami Flos (Honghua), Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Chishao), and Persicae Semen (Taoren) were frequently used to treat headaches with blood stasis syndrome. Cluster 1 and the association rules in Table 3-NO.1 to NO.9 were strongly correlated to these five herbs. Their combination is the base of XFZYD, playing an important role in treating headaches with blood stasis syndrome. XFZYD originated from the Qing Dynasty and is mainly used to treat symptoms such as headaches with blood stasis syndrome and angina pectoris. XFZYD has presented good efficacy in headaches with blood stasis syndrome [58,59] and provides significant relief from vascular headaches caused by blood stasis and associated symptoms, such as irritability, insomnia, dreaminess, tiredness, and palpitation [60]. XFZYD is also widely used in the cardiovascular, blood, and cerebrovascular systems [61]. It inhibits the proliferation of cardiac interstitial fibroblasts, the necrosis, and apoptosis of myocardial cells, have anti-atherosclerosis effects and induce endothelial cell proliferation and angiogenesis. The use of XFZYD is consistent with the TCM viewpoint.

Herein, we analyzed published CHMs for headaches with blood stasis syndrome and excluded conflicting factors, such as herb dosage. We combined data mining and analysis methods to provide scientifically reliable results and a reference for selecting herbs to treat headaches with blood stasis syndrome. However, our current study also has some limitations. First, most studies were from Chinese databases, and diagnoses relied on subjective factors. Hence, it is difficult to verify the valid authenticity of the selected literature. Meanwhile, we included only RCTs on CHMs with definite curative effects. We excluded studies on CHMs without definite efficacy or statistical significance between the CHM treatment and control groups. Besides, there was a certain degree of bias in the prescription screening. We did not systematically evaluate the medication rules for safety and effectiveness, and more RCTs are needed to verify them in the future.

5. Conclusion

In summary, we provided a reasonable reference for selecting CHMs for headaches with blood stasis syndrome. The preferred prescription comprised the combination of Angelica Sinensis Radix (Danggui), Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong), Carthami Flos (Honghua), Persicae Semen (Taoren), Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Chishao), Bupleuri Radix (Chaihu), Achyranthis Bidentatae Radix (Niuxi), and Glycyrrhizae Radix Et Rhizoma (Gancao). This prescription is based on XFZYD, which might be used as the first reference in the clinic. XYS and BYHWD herbs might also be used, and meridian-inducing and insect herbs can enhance the efficacy or treat the concomitant syndrome. However, the effectiveness and safety of these prescriptions or herbs should be rigorously verified by RCTs or systematic reviews in the future.

Author contribution statement

Guanghui Liu; Huiting Yang: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Li Bai; Yang Wang; Enlong Wang; Xiuye Sun; Hongyuan Zhang; Li Zhou; Zhe Zhang: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This work was supported by Key Technologies Research and Development Program [2018YFC1707407].

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conlifict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ran An, Qian Li, Ting-ting Li, Wen-jun Zhang, Liang Mao, Juan Liu, Xing-an Liu, Guang-yi Luan, Shi Zhang, and Yang Li (Department of Neurology, Affiliated Hospital of Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine) for contributions in the experimental design.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14996.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Jia J., Chen S. eighth ed. People's Medical Publishing House(PMPH); Beijing, China: 2018. Neurology; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Straube A., Andreou A. Primary headaches during lifespan. J. Headache Pain. 2019 Apr 8;20(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-0985-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018 Nov 10;392(10159):1789–1858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The international classification of headache disorders. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1–211. doi: 10.1177/0333102417738202. 3rd edition. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang X. Advances in pathogenesis of migraine and its treatment strategy. J. Neurol. Neuror. 2019;15(2):80–88. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Messlinger K., Fischer M.J., Lennerz J.K. Neuropeptide effects in the trigeminal system: pathophysiology and clinical relevance in migraine. Keio J. Med. 2011;60(3):82–89. doi: 10.2302/kjm.60.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun Y., Yao G., Yu T., et al. Research progress on mechanism of tension-type headache. China Med. Herald. 2019;16(3):37–39+48. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahriman A., Zhu S. Migraine and tension-type headache. Semin. Neurol. 2018;38(6):608–618. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1673683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li S., Li Y., Liu R., et al. Chinese Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of migraine. Chin. J. Prev. Med. 2011;17(2):65–86. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashina M., Buse D.C., Ashina H., et al. Migraine: integrated approaches to clinical management and emerging treatments. Lancet. 2021;397(10283):1505–1518. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32342-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eller M., Cheng S. Migraine management: an update for the 2020s. Int. Med. J. 2022;52(7):1123–1128. doi: 10.1111/imj.15843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen K.J. Blood stasis syndrome and its treatment with activating blood circulation to remove blood stasis therapy. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2012;18(12):891–896. doi: 10.1007/s11655-012-1291-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi T.Y., Jun J.H., Lee J.A., et al. Expert opinions on the concept of blood stasis in China: an interview study. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2016;22(11):823–831. doi: 10.1007/s11655-014-1983-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Y., Wang F. Mechanism and therapy on phlegm and static blood syndrome of migraine. China J. Tradit. Chinese Med. Pharm. 2007;(2):81–83. [Google Scholar]

- 15.China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences . China Traditional Chinese Medicine Publishing House; Beijing, China: 2011. Guidelines for Evidence-Based Clinical Practice of Traditional Chinese Medicine: Internal Diseases; pp. 213–220. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li W., Guo H., Wang X. Relationship between endogenous hydrogen sulfide and blood stasis syndrome based on the Qi-blood theory of Chinese medicine. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2013;19(09):701–705. doi: 10.1007/s11655-013-1567-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mi Y., Guo S., Cheng H., et al. Pharmacokinetic comparative study of tetramethylpyrazine and ferulic acid and their compatibility with different concentration of gastrodin and gastrodigenin on blood-stasis migraine model by blood-brain microdialysis method. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020;177 doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2019.112885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu Z., Wu H. Analysis of discrimination and treatment of tension-type headache. J. Shandong Univ. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2009;33(3):190–191. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Q., Wang Q. The effect of wind medicine in blood stasis headache. Jiangsu J. Tradit. Chinese Med. 2020;52(3):78–80. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu S., Yang Z., Wang X., et al. Chief physician Yang Zhihong's experience in treating headache. Western J. Tradit. Chinese Med. 2021;34(5):42–45. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao J. The common prescription patterns based on the hierarchical clustering of herb-pairs efficacies. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/6373270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Criteria of diagnosis and therapeutic effect of internal diseases and syndromes in traditionaI Chinese medicine (ZY/T001.1-94) J. Liaoning Univ. Tradit. Chinese Med. 2016;18(10):165. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Pharmacopoeia Commission . China Medical Science and Technology Press; Beijing, China: 2020. Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China: 2020 Edition. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nanjing University Of Chinese Medicine . Shanghai Science and Technology Press; Shanghai, China: 2006. The Dictionary of Chinese Herbal Medicine. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang H., Xie Y., Ni J., et al. Association rule analysis for validating interrelationships of combined medication of compound kushen injection in treating colon carcinoma: a hospital information system-based real-world study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/4579801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xia P., Gao K., Xie J., et al. Data mining-based analysis of Chinese medicinal herb formulae in chronic kidney disease treatment. Evid Based Compl. Alternat Med. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/9719872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang M., Luo J., Yang Q., et al. Research on the medication rules of Chinese herbal formulas on treatment of threatened abortion. Compl. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2021;43 doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2021.101371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li K., Zhang R. Discussion on Zhang Zhongjing's using of stasis-dissolving herbs. Tradit. Chinese Med. Res. 2017;30(9):8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li J., Wu D., Hou N., et al. Nature-effect relationship research of cold and warm medicinal properties of traditional Chinese medicine for promoting blood circulation and removing blood stasis based on nature combination. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 2019;44(2):212–217. doi: 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20180903.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ning Y., Ren Y., Zhang Y., et al. Zou Yihuai's experience for migraine. Liaoning J. Tradit. Chinese Med. 2017;44(5):928–929. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang L., Guo W., Sheng L. Discussion of the nine methods in regulating liver in the treatment of hemicrania. China J. Tradit. Chinese Med. Pharm. 2015;30(6):2002–2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhong G. tenth ed. People's Medical Publishing House(PMPH); Beijing, China: 2016. Chinese Material Medica; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang C., Lv G., Liu Q. The origin of meridian guiding herbs and its clinical application in the treatment of headache. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2013;54(16):1374–1376. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Z., Qu Q., Wu J., et al. Professor Wu Yu's experience in treatment of cancer pain. Liaoning J. Tradit. Chinese Med. 2021;48(1):38–40. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang L., Liu G., Wang A., et al. Discussion of the insects herbs in the treatment of intractable headache. Chinese J. Int. Med. Cardio-Cerebrovascular Disease. 2020;18(4):696–697. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou H., Huang H., Zhang J., et al. Research advances of Chuanxiong rhizoma - Angelicae Sinensis Radix herb pairs. Chin. Tradit. Pat. Med. 2015;37(1):184–188. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Z., Wang S. Effects of Angelica combined with Chuanxiong on hemorheology and coagulation function in acute blood rats. Modern J. Int. Tradit. Chinese and Western Med. 2014;17:1833–1835. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu J., Song J., Zeng J. Effect of Foshousan on the hemorheology in rat. Chin. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2009;29(5):356–358. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yuan R., Shi W., Xin Q., et al. Progress on rhizoma chuanxiong-radix Paeoniae Rubra herb pair. Global Tradit. Chinese Med. 2019;12(5):808–811. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang K., Zeng L., Ge A., et al. A network pharmacology approach to explore the molecular mechanism of taoren-honghua pair on syndrome of blood stasis. Modernizat. Tradit. Chinese Med. Materia Medica-World Sci. Technol. 2018;20(12):2208–2216. [Google Scholar]

- 41.You Z., Wen L. Herb pair for Gynecopathies(Ⅱ) China J. Basic Med. Tradit. Chinese Med. 2004;(5):24–26. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li J., Cheng J. Study of edible drug on TCM syndrome of qi deficiency and blood stasis and qi stagnation and blood stasis. J. Liaoning Univ. Tradit. Chinese Med. 2017;3:104–107. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang W., Li R. Research progress on the mechanism of Buyang Huanwu tang. Chinese J. Integ. Med. Cardio-Cerebrovascular Disease. 2008;(5):574–576. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fei H., Jiang B., Zhang Y., et al. Research progress of mechanism of Buyang Huanwu tang in brain. Inf. Tradit. Chinese Med. 2015;32(1):125–127. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou G. Acupuncture combined with Buyang Huanwu Decoction in treating migraine randomized parallel control study. J. Pract. Tradit. Chinese Internal Med. 2018;32(6):58–61. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang H., Zhang S. Influence of Buyang Huanwu decoction on endothelin and calcitonin gene-related peptide in patients with migraine. Chin. J. Exp. Tradit. Med. Formulae. 2013;19(2):311–314. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou X., Luo Y., Li J., et al. Research status of Buyang Huanwu decoction in the prevention and treatment of ischemic stroke. The Chinese J. Clinical Pharm. 2022;38(9):1011–1015. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu Z., Li J., Peng W., et al. Effect of animal medicines for "extinguishing wind to arrest convulsions" on central nervous system diseases. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 2018;43(6):1086–1092. doi: 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20171113.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fu G., Lu Y., Zhang Y., et al. Selection principles and analysis of common prescriptions in clinical practice guidelines of traditional Chinese medicine - case example of migraine. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 2020;45(21):5103–5109. doi: 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20200713.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shi J., Zhang J. Ma Yunzhi's experience in treating headaches with internal injury. Acta Chinese Med. 2019;34(4):749–753. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiang C., Zhou D., Zhang Q., et al. Therapeutic characteristics of CHEN Da-shun in treating tension-type headache. China J. Tradit. Chinese Med. Pharm. 2017;32(7):3012–3015. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ding F., Wu J., Liu C., et al. Effect of xiaoyaosan on colon morphology and intestinal permeability in rats with chronic unpredictable mild stress. Front. Pharmacol. 2020;11:1069. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.01069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu X., Wei F., Liu H., et al. Integrating hippocampal metabolomics and network pharmacology deciphers the antidepressant mechanisms of Xiaoyaosan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021;268 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Song Z. Efficacy observation on angioneurotic headache treated with meridian guiding herbs combined with Xiaoyao San. Shandong J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2015;34(7):517–518. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang H., Huang T., Peng L., et al. Curative effect of Xiaoyao Powder combined with auricular plaster therapy for liver depression type of dizziness and headache. Liaoning Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2016;43(8):1733–1735. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hui X., Liu Y., Jiang B., et al. Five medical cases of applying modified Xiaoyao Powder by TCM master DUAN Fu-jin. China J. Tradit. Chinese Med. Pharm. 2018;4:1380–1382. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li C., Liu Y., Wei P., et al. Research progress on antidepressant pathway and active ingredients of Xiaoyaosan and its analogous prescriptions. Chin. J. Exp. Tradit. Med. Formulae. 2020;6:243–250. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Deng J. Modified Xuefu Zhuyu Decoction in treating 80 cases of chronic headache. Sichuan J. Tradit. Chinese Med. 2002;(8):42–43. [Google Scholar]

- 59.He Y., Qu S., Hu X. Experience in treating headache with Xuefu Zhuyu tang. J. Basic Chinese Med. 2015;21(9):1187. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jin Y. Research progress on pharmacological action and clinical application of Xuefu Zhuyu Capsule. Pharm. Clinics of Chinese Materia Med. 2010;4:73–75. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu J., Chen X. Research progress on modern pharmacology of Xuefu Zhuyu tang. Chin. Tradit. Pat. Med. 2013;5:1054–1058. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.