This cohort study investigates how changes in the incidence of retinopathy of prematurity have varied across subpopulations and locations in the US from 2003 to 2019.

Key Points

Question

How have changes in the incidence of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) varied across subpopulations and locations in the US between 2003 and 2019?

Findings

In this cohort study of 125 212 ROP discharges from over 23 million births, there was an 86% increase in ROP incidence found among the at-risk population. Incidence was persistently higher with a relatively greater increase in newborns who were database-reported as Black race, born in lower-income households, or born in the South or Midwest.

Meaning

This study found that ROP incidence nearly doubled in the US over the past 2 decades, particularly in traditionally underserved populations.

Abstract

Importance

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is a potentially blinding retinal disease with poorly defined epidemiology. Understanding of which infants are most at risk for developing ROP may foster targeted detection and prevention efforts.

Objective

To identify changes in ROP incidence in the US from 2003 to 2019.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective database cohort study used the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Kids’ Inpatient Databases. These nationwide databases are produced every 3 years, include data from over 4000 hospitals, and are designed to generate national estimates of health care trends in the US. Participants included pediatric newborns at risk for ROP development between 2003 and 2019. Data were analyzed from September 30, 2021, to January 13, 2022.

Exposures

Premature or low-birth-weight infants with relevant International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision or Tenth Revision codes were considered ROP candidates. Infants with ROP were identified using relevant codes.

Main Outcomes and Measures

ROP incidence in selected subpopulations (based on database-reported race and ethnicity, sex, location, income) was measured. To determine whether incidences varied across time or subpopulations, χ2 tests of independence were used.

Results

This study included 125 212 ROP discharges (64 715 male infants [51.7%]) from 23 187 683 births. The proportion of premature infants diagnosed with ROP increased from 4.4% (11 720 of 265 650) in 2003 to 8.1% (27 160 of 336 117) in 2019. Premature infants from the lowest median household income quartile had the greatest proportional increase of ROP diagnoses from 4.9% (3244 of 66 871) to 9.0% (9386 of 104 235; P < .001). Premature Black infants experienced the largest increase from 5.8% (2124 of 36 476) to 11.6% (7430 of 63 925; P < .001) relative to other groups (2.71%; 95% CI, 2.56%-2.87%; P < .001). Hispanic infants experienced the second largest increase from 4.6% (1796 of 39 106) to 8.2% (4675 of 57 298; P < .001) relative to other groups (−0.16%; 95% CI, −0.29% to −0.03%; P = .02). The Southern US experienced the greatest proportional growth of ROP diagnoses, increasing from 3.7% (3930 of 106 772) to 8.3% (11 952 of 144 013; P < .001) relative to other groups (1.61%; 95% CI, 1.51%-1.71%; P < .001). ROP diagnoses proportionally increased in urban areas and decreased in rural areas.

Conclusions and Relevance

This cohort study found that ROP incidence among premature infants increased from 2003 to 2019, especially among Black and Hispanic infants. Infants from the lowest-income areas persistently had the highest proportional incidence of ROP, and all regions experienced a significant increase in ROP incidence with the most drastic changes occurring in the South. These trends suggest that ROP is a growing problem in the US and may be disproportionately affecting historically marginalized groups.

Introduction

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is an eye disorder primarily affecting premature and low-birth-weight infants that can lead to lifelong vision impairment and blindness. ROP occurs due to abnormal development of retinal blood vessels and is a major worldwide cause of childhood blindness.1 Laser photocoagulation is considered the criterion standard treatment for ROP, showing improved outcomes over cryotherapy, and early detection and treatment are vital to optimizing clinical outcomes.2 Previous literature described 3 different ROP epidemics. The first 2 occurred in industrialized countries starting in the 1940s and 1970s, and a third occurred in lower-income countries in the 1990s.3,4 Unmonitored supplemental oxygen, neonatal care advancements, and higher premature infant survival rates have all contributed to increased ROP incidence. Recent studies have shown that ROP incidence in the US continues to rise and that another ROP epidemic may be forthcoming.5,6 To investigate these trends, we used a large database to elucidate longitudinal, population-level changes in the incidence of ROP in the US.7

The National Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Kids’ Inpatient Databases (KIDs) from 2003 to 2019 were used to analyze ROP incidence in the US across database-reported sexes, racial groups, income groups, and geographic regions. Temporal changes in incidence as well as disparities across various subpopulations were identified.

Methods

Data Source

All data for this cohort study was derived from KIDs. These nationwide databases are produced every 3 years as part of the HCUP. KIDs are the largest pediatric (age <21 years) inpatient care databases in the US and are designed to generate national estimates of health care trends. Each version contains clinical and nonclinical information for an estimated 7 million pediatric hospitalizations from over 4000 US hospitals. We examined all KIDs produced between 2003 and 2019 (the most recent version available). These include data from years 2003, 2006, 2009, 2012, 2016, and 2019. Production of KIDs was delayed from 2015 to 2016 due to a transition from International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) and Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes. The HCUP-KID database conforms to the definition of a limited data set, which does not require institutional review board approval. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

Patient Selection and Classification

Patient informed consent was not obtained as this study was completed using a publicly available, government-produced limited data set. All data are deidentified, and no attempts to identify individual patients were made. Newborn patients were identified from KIDs using relevant ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnosis codes (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Newborn infants who also had codes designating low birth weight (≤1500 g) or premature birth (≤36 weeks’ gestational age) were considered ROP candidates.

Separately, patients with ROP younger than 1 year were identified directly from KIDs using relevant ICD codes (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). These codes include all cases of ROP, regardless of stage or involvement of 1 eye or both. Patients with ROP were not drawn directly from the ROP candidate pool as this could potentially underestimate ROP incidence due to multiple factors. First, in a billing database like KID, newborns are likely to have missing codes relating to birth weight or birth week because these codes do not influence reimbursement; patients are more likely to have a code for ROP, which does influence reimbursement. Second, KIDs track hospitalizations, not patients; patients with ROP not diagnosed during their birth hospitalization would therefore be missed.

Key Populations

Key subpopulations were created based on database-reported race and ethnicity, income, sex, region, and metropolitan status. The study used KIDs racial and ethnic categories, which include Asian/Pacific Islander, Black, Hispanic, Native American, White, and other (includes biracial individuals or individuals of an unlisted race). Median household income (MHI) quartile of a patient’s zip code was used as a proxy variable for patient income. The MHI quartile estimates are updated annually by HCUP with first quartile being the lowest income and fourth quartile being the highest. The first through fourth quartiles for 2003 were $1 to $35 999, $36 000 to $44 999, $45 000 to $59 999, and $60 000 or more, respectively. The first through fourth quartiles for 2019 were $1 to $47 999, $48 000 to $60 999, $61 000 to $81 999, and $82 000 or more, respectively. There were 2 considered sexes: male and female. Region was defined in accordance with the US Census Bureau (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West); each region was divided into rural and urban areas based on the Core Based Statistical Area (CBSA) type determined by the United States Office of Management and Budget. Hospitals were considered urban if located in counties classified as CBSA metropolitan type or rural if located in counties classified as CBSA micropolitan or noncore type.

Statistical Analysis

For each subpopulation, incidences among ROP candidates and all newborn births were calculated. To determine whether incidences varied by year or across subpopulations, χ2 tests of independence were used. Two-sample proportion testing was used to compare incidence changes from 2003 to 2019 for each subpopulation relative to other groups. Unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) were calculated using univariate analysis to determine associations between demographic risk factors and ROP incidence. All data were weighted in accordance with KID policy. KID requires that researchers use their database-provided weights, which allow one to accurately generate national estimates from a sample.8 These values effectively adjust the importance of individual data points to more accurately represent the national population. SPSS software, version 28.0 (IBM Corp) and Excel 2016 (Microsoft Inc) were used to conduct statistical analyses. All P values were 2-sided but not adjusted for multiple analyses, and a P value < .05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed from September 30, 2021, to January 13, 2022.

Results

Descriptive Statistics of Patient Demographics

Pooled demographics of all newborn infants, ROP candidates, and patients with ROP from 2003 to 2019 are provided in the Table. Across the 16 years included in this study, 23 187 683 newborn infants were identified. The annual number of newborn infants either stayed constant or decreased slightly from 2003 to 2019. Of the newborn births, 1.9 million infants were considered ROP candidates due to either being born prematurely or having a low birth weight. The number of ROP candidates born each year stayed relatively constant from 2003 to 2019.

Table. Demographics of Patients, Premature Infants, and Newborn Infants With Retinopathy of Prematurity (ROP; 2003-2019)a.

| Population | Count (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Candidates | All newborns | |

| Total | 125 212 | 1 881 098 | 23 187 683 |

| Database-reported sex | |||

| Male | 64 715 (51.7) | 995 012 (52.9) | 9 989 233 (43.1) |

| Female | 60 474 (48.3) | 884 979 (47.0) | |

| Missing | 23 (0) | 1107 (0.1) | 3 661 375 (15.8) |

| Database-reported race | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 4103 (3.3) | 70 703 (3.8) | 997 741 (4.3) |

| Black | 30 193 (24.1) | 311 326 (16.6) | 2 693 336 (11.6) |

| Hispanic | 20 714 (16.5) | 305 148 (16.2) | 4 197 483 (18.1) |

| Native American | 681 (0.5) | 12 550 (0.7) | 140 543 (0.6) |

| White | 45 570 (36.4) | 786 967 (41.8) | 10 004 734 (43.1) |

| Otherb | 8370 (6.7) | 99 731 (5.3) | 1 235 929 (5.3) |

| Missing | 15 581 (12.4) | 294 672 (15.7) | 3 917 916 (16.9) |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | |||

| Urban | 18 943 (15.1) | 281 632 (15.0) | 3 558 351 (15.3) |

| Rural | 303 (0.2) | 13 216 (0.7) | 250 262 (1.1) |

| Midwest | |||

| Urban | 26 276 (21.0) | 357 321 (19.0) | 4 056 653 (17.5) |

| Rural | 1315 (1.0) | 48 301 (2.6) | 896 373 (3.9) |

| South | |||

| Urban | 52 593 (42.0) | 696 818 (37.0) | 7 691 874 (33.2) |

| Rural | 1588 (1.3) | 74 806 (4.0) | 1 211 549 (5.2) |

| West | |||

| Urban | 23 885 (19.1) | 386 397 (20.5) | 5 050 200 (21.8) |

| Rural | 309 (0.2) | 22 607 (1.2) | 472 420 (2.0) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) |

| MHI quartile for patient zip codec | |||

| 1st | 40 809 (32.6) | 548 520 (29.2) | 5 265 330 (22.7) |

| 2nd | 30 818 (24.6) | 372 737 (19.8) | 4 824 015 (20.8) |

| 3rd | 28 618 (22.9) | 366 824 (19.5) | 4 806 479 (20.7) |

| 4th | 22 937 (18.3) | 334 426 (17.8) | 4 371 764 (18.9) |

| Missing | 2031 (1.6) | 258 592 (13.7) | 3 920 095 (16.9) |

| Data on birth weight and birth week | |||

| Not missing | 108 858 (86.9) | 1 881 098 (100)d | 3 064 937 (13.2)e |

| Missing | 16 354 (13.1) | 0 (0)d | 20 122 746 (86.8) |

Abbreviation: MHI, median household income.

Percentages are rounded to nearest tenth; therefore, cumulative total may not equal 100%.

Other race and ethnicity includes biracial individuals or individuals of an unlisted race.

The first through fourth MHI quartiles for each year analyzed are as follows: 2003: $1 to $35 999, $36 000 to $44 999, $45 000 to $59 999, $60 000 or more; 2006: $1 to $37 999, $38 000 to $46 999, $47 000 to $61 999, $62 000 or more; 2009: $1 to $39 999, $40 000 to $49 999, $50 000 to $65 999, $66 000 or more; 2012: $1 to $38 999, $39 000 to $47 999, $48 000 to $62 999, $63 000 or more; 2016: $1 to $42 999, $43 000 to $53 999, $54 000 to $70 999, $71 000 or more; and 2019: $1 to $47 999, $48 000 to $60 999, $61 000 to $81 999, $82 000 or more.

To qualify as an ROP candidate, patients must have had qualifying data either on birth weight or birth week. Therefore, there were 0 ROP candidates with missing data on both birth weight and birth week.

A total of 61.4% of newborns (1 881 098) with any data on birth weight and birth week were classified as ROP candidates.

A total of 125 212 ROP discharges (64 715 male infants [51.7%]; 60 474 female infants [48.3%]) were identified. Infants from the following KIDs race and ethnicity categories were identified: 4103 Asian/Pacific Islander (3.3%), 30 193 Black (24.1%), 20 714 Hispanic (16.5%), 681 Native American (0.5%), 45 570 White (36.4%), and 8370 other (6.7%). A total of 52 593 patients with ROP (42.0%) were located in the urban South, whereas 18 943 (15.1%) were located in the urban Northeast. Across all geographic areas, the majority of patients with ROP were from urban hospitals. One-third of all patients with ROP (40 809 [32.6%]) were born to parents living in areas with the lowest MHI quartile, whereas 22 937 (18.3%) were born to parents living in areas with the highest MHI quartile.

Univariate analysis showed that infants with ROP were more likely to be female (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.03-1.07), Black (OR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.70-1.74) or Hispanic (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.03-1.07), or live in the urban South (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.20-1.23) or urban Midwest (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.16-1.20) (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). They were also more likely to be from zip codes associated with lower MHIs. Infants with ROP had lower odds of being born in the West and of being Asian/Pacific Islander or Native American.

Overall Incidence of ROP From 2003 to 2019

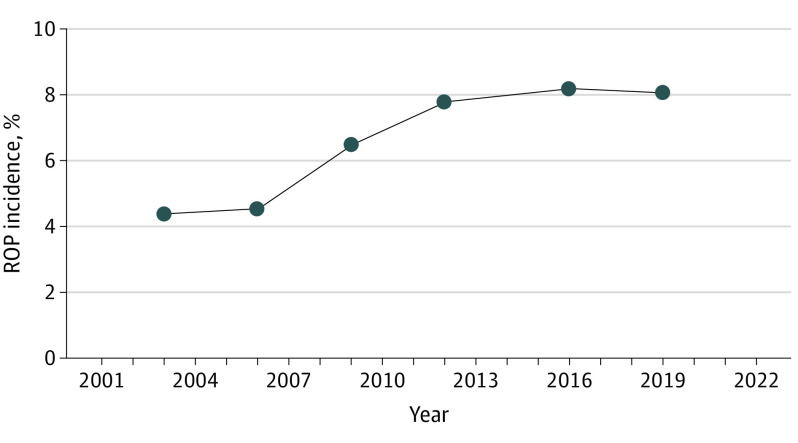

The incidence of ROP among all newborn births increased significantly from 0.3% (11 720 of 3 930 094) in 2003 to 0.76% (27 160 of 3 588 465) in 2019, representing a 139% relative increase in ROP incidence (P < .001). ROP incidence among ROP candidates also increased significantly from 4.4% (11 720 of 265 650) in 2003 to 8.1% (27 160 of 336 117) in 2019, which represented an 86% relative increase (P < .001). ROP incidence experienced its fastest growth between 2006 and 2012 with incidence peaking at 8.2% (26 978 of 329 001) in 2016. From 2016 to 2019, growth of ROP incidence plateaued (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Retinopathy of Prematurity (ROP) Incidence Between 2003 and 2019.

ROP incidence increased from 4.4% in 2003 to 8.1% in 2019, an 86% change increase. Incidence increased most rapidly between 2006 and 2012.

Incidence of ROP Across Races and Ethnicities

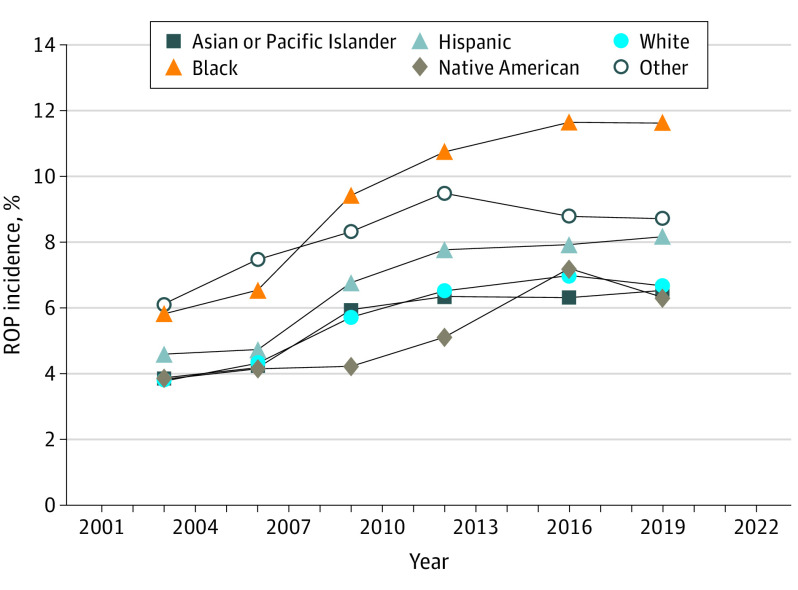

ROP incidence increased across all races and ethnicities between 2003 and 2019 (Figure 2). In most years, individuals classified as Black, Hispanic, or other had higher ROP incidences than those classified as Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American, or White. ROP incidence among Black ROP candidates doubled from 5.8% (2124 of 36 476) in 2003 to 11.6% (7430 of 63 925) in 2019 (P < .001). A total of 7430 of 488 612 Black newborn births (1.5%) were diagnosed with ROP in 2019. Incidence increase among Black infants was 2.71% greater (95% CI, 2.56%-2.87%; P < .001) than among the pooled incidence of Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, Native American, White, and other race infants. Hispanic infants experienced an increase from 4.6% (1796 of 39 106) to 8.2% (4675 of 57 298; P < .001), and White infants experienced an increase in ROP incidence from 3.8% (3904 of 103 432) in 2003 to 6.7% (9572 of 143 236) in 2019 (P < .001), with both changes representing approximately 77% relative increases in ROP incidence. Incidence increase over time among White and Hispanic infants was 1.33% lower (95% CI, −1.43% to −1.23%; P < .001) and 0.16% lower (95% CI, −0.29% to −0.03%; P = .02) than among the pooled incidence of Asian/Pacific Islander, Black, Hispanic, Native American, and other race infants and Asian/Pacific Islander, Black, Native American, White, and other race infants, respectively. Incidence among the Asian/Pacific Islander population increased during the same period from 3.9% (260 of 6708) to 6.5% (994 of 15 207) relative to other groups (−1.09%; 95% CI, −1.30% to −0.87%; P < .001), whereas Native American infants experienced a similar increase from 3.8% (34 of 889) to 6.3% (172 of 2714) relative to other groups (−1.20%; 95% CI, −1.71% to −0.69%; P < .001).

Figure 2. Retinopathy of Prematurity (ROP) Incidence Across Races and Ethnicities Between 2003 and 2019.

ROP incidence increased across all races and ethnicities between 2003 and 2019. ROP incidence was persistently highest among Black ROP candidates relative to other races and ethnicities, doubling from 5.8% in 2003 to 11.6% in 2019.

Incidence of ROP Across Geographic Regions

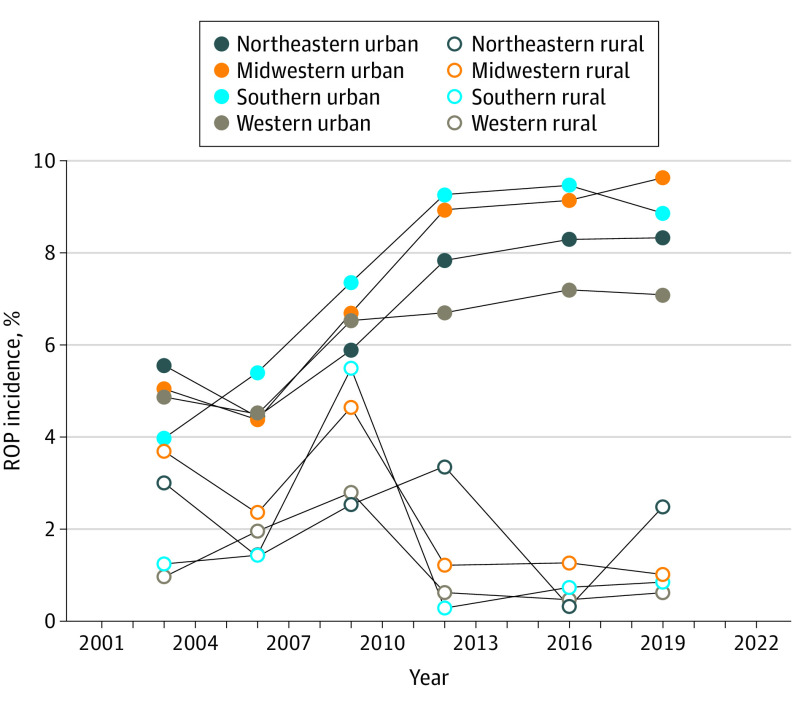

From 2003 to 2019, ROP incidence increased in all geographic regions (Figure 3). ROP incidence among ROP candidates in the South increased from 3.7% (3930 of 106 772) to 8.3% (119 952 of 144 013), representing a relative 125% increase (P < .001). Incidence in the South increased by 1.61% (95% CI, 1.51%-1.71%; P < .001) more compared with increases seen by other regions. Among all Southern newborn births, ROP incidence increased 210% between 2003 and 2019. ROP incidence in the Midwest increased from 4.9% (2920 of 59 892) to 8.9% (6191 of 69 810), which was an 82% relative increase in ROP (P < .001) relative to other groups (0.40%; 95% CI, 0.28%-0.52%; P < .001). ROP incidence in the Northeast increased by 51% between 2003 and 2019 from 5.4% (2174 of 40 283) to 8.2% (2696 of 58 703) relative to other groups (−1.07%; 95% CI, −1.19% to −0.95%; P < .001). The West experienced a similar relative increase from 4.6% (2696 of 58 703) to 6.8% (4869 of 71 429) relative to other groups (−1.84%; 95% CI, −1.94% to −1.74%; P < .001).

Figure 3. Retinopathy of Prematurity (ROP) Incidence Across Geographic Region Between 2003 and 2019.

ROP incidence increased in all geographic regions between 2003 and 2019, with Southern urban areas experiencing the largest relative increase (123%).

ROP incidence increased in all urban regions and decreased in rural ones between 2003 and 2019. In Northeastern, Midwestern, Southern, and Western urban regions, ROP incidence relatively increased by 50%, 91%, 123%, and 46%, respectively. In the corresponding rural regions, ROP incidence relatively decreased by 18%, 73%, 32%, and 36%, respectively.

Incidence of ROP Across Median Household Income Quartiles Based on Zip Codes

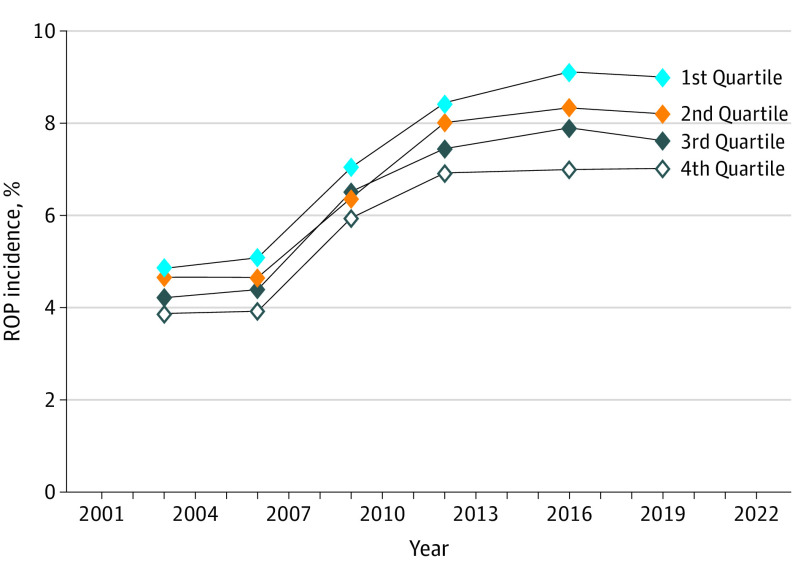

Between 2003 and 2019, ROP incidence increased in all MHI quartiles (Figure 4). Patients from the lowest MHI quartile experienced an 86% relative increase in ROP incidence between 2003 to 2019 from 4.9% (3244 of 66 871) to 9.0% (9386 of 104 235; P < .001). This represents a 0.73% (95% CI, 0.62%-0.84%; P < .001) increase in incidence relative to those of other MHI quartiles. Among all newborn births, this represents a 180% relative increase in ROP incidence. Those in the second-lowest MHI quartile experienced an increase in ROP incidence from 4.6% (3010 of 64 811) to 8.2% (6755 of 82 196; P < .001) relative to other groups (−0.15%; 95% CI, −0.26% to −0.04%; P = .007). Those in the second-highest MHI quartile and the highest MHI quartile both experienced 81% relative increases in ROP incidence from 4.2% (2780 of 66 045) to 7.6% (6161 of 80 847) and 3.9% (2441 of 63 267) to 7.0% (4620 of 65 825), respectively (both, P < .001). Incidence increases in the second-highest MHI quartile and the highest MHI quartile were respectively lower by 0.36% (95% CI, −0.47% to −0.25%; P < .001) and 0.61% (95% CI, −0.72% to −0.50%; P < .001) compared with those of other quartiles.

Figure 4. Retinopathy of Prematurity (ROP) Incidence Across Median Household Income (MHI) Quartile Based on Zip Codes Between 2003 and 2019.

ROP incidence increased in all MHI quartiles between 2003 and 2019, disproportionately affecting those born to parents residing in the lowest income quartile areas.

Incidence of ROP Across Sexes

ROP incidence among female infants increased from 4.6% (5760 of 125 163) to 8.3% (13 112 of 158 041), representing an 80% relative increase (eFigure in Supplement 1). ROP incidence among male infants increased from 4.2% (5955 of 140 365) to 7.9% (14 041 of 177 868), representing an 86% relative increase. Incidence increase among male infants was 0.04% (95% CI, −0.14% to 0.05%; P = .38) lower than among female infants.

Discussion

This cohort study presents an updated characterization of the epidemiology of ROP in the US. Examination of more than 125 000 patients with ROP from over 23 million births revealed that ROP incidence nearly doubled over the past 2 decades, which is consistent with prior predictions.5,6 Although the growth rate of ROP seems to have plateaued and even decreased slightly in the past few years, the overall increased incidence over the time period studied is apparent.

There are multiple potential explanations for this finding including higher survival rates of extremely low-birth-weight infants due to advances in neonatological care.9,10 Low birth weight and early gestational age are associated with a greater risk of developing ROP.11,12 The number of preterm births fluctuated but trended upward, which may also contribute to an increase in the absolute number of patients with ROP. Total number of births fluctuated but trended downward in our study period suggesting it was an unlikely driver of the observed increase.

Increased ROP incidence may also be due to improved screening guidelines that were established around the study period. In 1997, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended ROP screening for infants with gestational age younger than 28 weeks or with birth weight lower than 1500 g.13 Updated guidelines in 2006 and 2013 expanded the population for whom screening was recommended and may have partially contributed to the observed increase in ROP incidence over the studied years.5 However, this probably does not fully account for the observed ROP increase as our study followed inclusion criteria even more inclusive than the most recent/restrictive guidelines for identifying ROP candidates. This methodology ensures that almost all possible ROP candidates who would undergo screening were captured in our study cohort, even prior to guideline changes, thereby supporting a true increase in ROP incidence.

In addition to an overall increase in ROP incidence, some subpopulations seem to have been disproportionately affected. These disparities appear to be persistent, if not growing over time, for those of certain races, incomes, and geographic areas. Consistent with a prior KID analysis, Black and Hispanic patients were found to be significantly more likely to develop ROP than infants of other races.5 Black infants, especially, had higher incidences in every studied year than other infants. They also had the greatest relative increase in ROP during the study period. These findings correlate with well-known racial and ethnic disparities in our health care system, which often associate racial minority groups with poorer access to care, worse health outcomes, and higher health care costs.14

Babies born to parents in lower income quartiles persistently had higher incidences of ROP than those in higher quartiles, with differences that did not diminish with time. These findings also support previous small studies that found higher incidences of ROP in lower-income areas and can potentially be explained by decreased access to prenatal care and insufficient maternal nutrition.15 International comparisons corroborate this income disparity association, as ROP incidences have increased exponentially in lower-income countries compared with higher-income ones.3,16 These observations may be due to lower awareness of ROP, poorer screening capabilities due to limited staff and equipment, and greater variation in infant weight and term status in lower-income countries; these phenomena could also be occurring within lower-income regions in the US.

Given known health disparities of people living in rural and/or underserved areas, it is important to consider access to ROP screening and ophthalmologic care for at-risk infants in those areas.17 Regardless of region, the burden of ROP seems to have shifted from rural hospitals to urban ones, although this trend could also be explained by poorer screening in rural areas. People living in rural and low-income areas usually need to travel significantly farther to access ROP clinical trial sites, which often represent care centers.18 Access to both the expertise and resources necessary for ROP screening and treatment is not equitably distributed across the US, and populations facing greater barriers to care are also often the groups likely to be most affected by ROP. Although telemedicine may improve access to care for vulnerable patient populations, its applications still mostly pertain to screening.19 If patients with ROP require treatment, they would still be subject to travel burdens for care.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. The included data are limited to what is available in the KID database, which does not capture information outside of the hospital setting. Because KID tracks individual discharges instead of patients, it is possible that a single ROP newborn could be hospitalized multiple times and be counted as multiple records. Additionally, the aggregated incidence data do not account for potential confounders; it is possible that observed differences in incidences across certain subpopulations may be secondary to other differences between groups. Finally, all databases are subject to missing data, which may influence results. For example, 86.8% of all newborns in our cohort were missing birth weight and birth week codes. However, these likely represent full-term babies who do not affect our estimations of either ROP candidates or ROP patients. First, birth weight and birth week codes do not typically factor into reimbursement whereas an ROP code does; therefore, it would be unlikely for billers to input additional codes unless they were supporting an ROP code. Second, the majority (61.4%) of newborns with any data on weight and week were considered ROP candidates. Obviously, the true preterm rate is significantly lower than 61.4%, suggesting that actual ROP candidates are indeed captured within this subset. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated an actual preterm birth rate of approximately 10% in 2019; assuming this rate, one would expect approximately 2.3 million preterm births of our sample of 23 million newborns. We classify 1.9 million births as preterm, or ROP candidates, suggesting capture of approximately 83% of all preterm births using weight and week codes.20 Although omission of some ROP candidates and patients with ROP due to missing codes is likely and represents a challenge shared by essentially all database studies, we believe that the majority of ROP candidates and patients with ROP have been captured in this largest-to-date characterization of ROP epidemiology in the US.

Despite limitations, our findings were significant as they suggest that the burden of ROP is increasing and resting disproportionately on historically marginalized populations. Vision loss represents a significant financial and quality-of-life burden that can exacerbate differences in health outcomes of these populations.21 Future work should focus on understanding the root cause of these discrepancies, which may include factors such as access to and quality of prenatal and ROP care. Improved screening methods that incorporate ancillary imaging modalities and telemedicine may improve ROP detection and management, and continued study is warranted.

Conclusions

In this cohort study, we found that the overall incidence of ROP among premature infants nearly doubled from 2003 to 2019. This rise in ROP has substantial medical and economic consequences for multiple stakeholders in the US health care system including patients, physicians, and policy makers. In addition to detrimental effects on morbidity and mortality, ROP is costly. One study found that low-birth-weight infants with ROP incurred 16% greater expenditures than those without ROP over the first 6 months of life.22 Additionally, growing demand for ROP care may place a heavy strain on limited health care professionals and resources. This study also identified concerning racial, socioeconomic, and geographical disparities in infants who were Black or Hispanic, had lower income, or were from the South or Midwest and may be more significantly affected by the increase in ROP incidence. Although causation cannot be determined from this database study, these trends emphasize that ROP is a growing problem in the US and may be disproportionately affecting certain subpopulations.

eTable 1. ICD-9 and ICD-10 Codes for Patient Selection

eTable 2. Demographic Risk Factors for ROP Incidence (2003-2019)

eFigure. ROP Incidence Across Sexes Between 2003 to 2019

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Hartnett ME, Penn JS. Mechanisms and management of retinopathy of prematurity. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(26):2515-2526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark D, Mandal K. Treatment of retinopathy of prematurity. Early Hum Dev. 2008;84(2):95-99. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2007.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilbert C. Retinopathy of prematurity: a global perspective of the epidemics, population of babies at risk and implications for control. Early Hum Dev. 2008;84(2):77-82. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2007.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert C, Malik ANJ, Nahar N, et al. Epidemiology of ROP update—Africa is the new frontier. Semin Perinatol. 2019;43(6):317-322. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2019.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ludwig CA, Chen TA, Hernandez-Boussard T, Moshfeghi AA, Moshfeghi DM. The epidemiology of retinopathy of prematurity in the US. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2017;48(7):553-562. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20170630-06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tasman W. Retinopathy of prematurity: do we still have a problem?—the Charles L. Schepens lecture. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(8):1083-1086. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weng CY, Kim JE. When the N is 65 million—the rise of database research. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139(8):855-856. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2021.1853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . Producing national HCUP estimates—kids’ inpatient database (KID). Published December 13, 2018. Accessed January 27, 2023. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/tech_assist/nationalestimates/508_course/508course_2018.jsp#kid

- 9.Brumbaugh JE, Hansen NI, Bell EF, et al. ; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Outcomes of extremely preterm infants with birth weight less than 400 g. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(5):434-445. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Younge N, Goldstein RF, Bann CM, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Survival and neurodevelopmental outcomes among periviable infants. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):617-628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1605566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaber R, Sorour OA, Sharaf AF, Saad HA. Incidence and risk factors for retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) in biggest neonatal intensive care unit in Itay El-Baroud city, Behera Province, Egypt. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:3467-3471. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S324614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lundgren P, Kistner A, Andersson EM, et al. Low birth weight is a risk factor for severe retinopathy of prematurity depending on gestational age. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109460. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SK, Normand C, McMillan D, Ohlsson A, Vincer M, Lyons C; Canadian Neonatal Network . Evidence for changing guidelines for routine screening for retinopathy of prematurity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(3):387-395. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.3.387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453-1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charles JB, Ganthier R Jr, Appiah AP. Incidence and characteristics of retinopathy of prematurity in a low-income inner-city population. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(1):14-17. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(91)32350-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vinekar A, Dogra M, Azad RV, Gilbert C, Gopal L, Trese M. The changing scenario of retinopathy of prematurity in middle- and low-income countries: unique solutions for unique problems. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;67(6):717-719. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_496_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coughlin SS, Clary C, Johnson JA, et al. Continuing challenges in rural health in the USS. J Environ Health Sci. 2019;5(2):90-92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soares RR, Cai LZ, Bowe T, et al. Geographic access disparities to clinical trials in retinopathy of prematurity in the US. Retina. 2021;41(11):2253-2260. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000003218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brady CJ, D’Amico S, Campbell JP. Telemedicine for retinopathy of prematurity. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26(4):556-564. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK. Births in the United States, 2021. Accessed February 10, 2023. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/119632

- 21.Rahi JS, Cable N; British Childhood Visual Impairment Study Group . Severe visual impairment and blindness in children in the UK. Lancet. 2003;362(9393):1359-1365. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14631-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beam AL, Fried I, Palmer N, et al. Estimates of healthcare spending for preterm and low-birth-weight infants in a commercially insured population: 2008-2016. J Perinatol. 2020;40(7):1091-1099. doi: 10.1038/s41372-020-0635-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. ICD-9 and ICD-10 Codes for Patient Selection

eTable 2. Demographic Risk Factors for ROP Incidence (2003-2019)

eFigure. ROP Incidence Across Sexes Between 2003 to 2019

Data Sharing Statement