Abstract

Rationale:

We performed a scoping review of informatics core literature about medical practice variation (MPV) as an agile summary of the subject in our field.

Materials and methods:

The Ovid integrated database was searched between 1946 and 2022 to identify MPV studies published in major informatics journals and conference proceedings. Two reviewers performed relevance screening, with assistance from another independent reviewer for adjudication. The included articles were then thematically analyzed and summarized through discussion among all three reviewers.

Results:

A total of 43 articles were included and went through the thematic analysis. About half (n = 21) of the included articles were published in conference proceedings. Five articles reported the effect of MPV on patient outcomes. The variation of interest was most frequently in treatment decisions. In terms of the role informatics played (multiple roles allowed), 39 (90.7%) articles pertained to detection of MPV, 5 were about prevention of MPV and 4 about learning from MPV.

Discussion:

MPV remains a critical issue in health care, yet most informatics research has been focused on simple tasks such as automating the detection of MPV and assessing compliance to decision-support systems, and less focused on addressing the causes of variation or supporting learning from variation.

Conclusion:

Our scoping review found that informatics studies have focused on detecting of MPV, especially variability in treatments and deviation from practice guidelines. Technological advances should promote more informatics research focused on explaining and learning from MPV.

Keywords: Professional practice gaps, Guideline adherence, Clinical practice patterns, Medical informatics, Review

1. Introduction

Clinical practice is rife with variation – when a specific clinical task, e.g., the prescription of prophylactic antibiotics prior to urological procedures, is performed differently across providers, regions, or times. Variation is a more general term that accounts for different ways (unwarranted or legitimate) a clinical task can be performed, while deviation refers to noncompliance with a recommended best practice and thus can be semantically covered under variation. Both the variation and deviation, which we jointly describe as medical practice variation (MPV), could imply low- or high-quality care: Unwarranted MPVs can reduce effectiveness and safety and contribute to health disparities [1,2]. Conversely, some MPVs represent individualized care that accommodates specific preferences or needs, i.e., they reflect high quality patient-centered care [3] and sometimes the empirical know-hows [4,5].

The auditing of unwarranted MPV has been a core interest to the field of health services research (HSR). This line of research can date back to four decades ago when Jack Wennberg initiated a series of studies to examine MPVs that were not linked to the individual disease conditions of concern but to other arbitrary variables such as geography. MPV research in HSR has emphasized the importance of analyzing healthcare data from its inception, as manifested by deliverables such as the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care [6] and the Wennberg International Collaborative’s Data Statement [7]. In addition to the emphasis on data, HSR is also aligned with the informatics discipline in addressing MPV through shared decision-making and learning health systems [8]. Provided the similarity, it appears that informatics is not distinguishable from HSR in MPV research – yet the notion of MPV is not as well recognized in the informatics community. To investigate the nuances, an essential start would be summarizing what informatics studies have been conducted on MPV, especially searching whether the informatics research has targeted beyond the HSR’s core interest in auditing unwarranted MPV.

Thus, we set out to survey the research on MPV published in core informatics journals and conference proceedings to identify the representative topics, gaps, and opportunities. This focused strategy reflects our intent to scope how the informatics discipline has been “explicitly” addressing MPV, in which the synonyms of MPV were literally referred to as a theme in the title, abstract, or keywords. We chose a scoping review approach because it aligns exactly with our goal of mapping the key concepts and gaps in the field.

2. Background and significance

Medical practice involves reasoning and decision-making that are affected by interlaced factors from the patient, clinician, and environment – all contributing to potential variation [9]. Disease-specific clinical practice guidelines (CPG), often designed to reduce unwarranted variation, fall short of their goal in the care of patients with multiple chronic conditions in which their application can lead to harm due to disease-disease, drug-drug, and drug-disease interactions. In the care of these patients, variation then results from the variability in clinicians’ judgments based on their beliefs, instincts, or even incentives [10]. In 1995, Holzemer and Reilly [11] formally introduced MPV to the informatics community along with a summary of the methodological challenges and valuable advice. In a viewpoint article, Bakken [12] proposed medical informatics as an essential solution for reducing unintended MPV and promoting evidence-based practice. A more recent literature review in 2016 by Arts, Voncken, Medlock et al. [13] focused on intentional nonadherence to CPG. Other than these articles, there has not been any assessment of the progress of MPV as a subject within the core informatics literature. Health services research is the other discipline more established in terms of conducting MPV research over several decades [14,15]. Medical informatics and health services research have evolved in parallel and increasingly demonstrate shared interests [16]. Without attempting to compare the two disciplines, we expect that a survey of informatics research in MPV would contribute to a continuing dialogue across these different but convergent research communities. Unlike previous work, our scoping review has featured summaries of the clinical tasks in which MPV occurred and the roles that informatics played in addressing MPV.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Bibliography search

The scoping review targeted studies about MPV in major informatics journals or proceedings that were in the English language and published up to the time when the search was performed (March 14, 2022). A senior librarian (LJP) devised the search strategy shown in Table 1. The Ovid integrated database was searched, which covered: EBM Reviews – Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (until January 2022), EBM Reviews – Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (since 2005), Embase (since 1974), Ovid MEDLINE and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily (since 1946). An additional set of articles were obtained from the authors’ collection and from colleagues.

Table 1.

Search strategy for MPV research in informatics journals or conference proceedings.

| Step | Query | Hits |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 1 | (guideline* or protocol* or recommendation* or “best practice”).ti,ab,hw,kw. | 3,526,178 |

| 2 | ((provider* or clinician* or physician* or doctor* or nurse* or practice or practitioner*) adj5 (deviation* or variation* or divergenc* or discrepanc* or “non-complian*” or noncomplian* or “non-adheren*” or nonadheren*)).ti,ab,hw, kw. | 31,772 |

| 3 | 1 and 2 | 11,768 |

| 4 | informatics.jw. | 93,903 |

| 5 | artificial intelligence in medicine.jn. | 3586 |

| 6 | “methods of information in medicine”.jn. | 6185 |

| 7 | “journal of medical internet research”.jn. | 14,384 |

| 8 | amia.jw. | 11,856 |

| 9 | 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 | 129,585 |

| 10 | 3 and 9 | 116 |

| 11 | Limit 10 to English language | 116 |

| 12 | Remove duplicates from 11 | 62 |

Abbreviations: ti – title, ab – abstract, hw – word in the subject heading or publication type, kw – keywords provided by authors, jw – word in the journal name, jn – full journal name, and adj5 – conjunction operator that requires the clauses before and after it must occur within 5 words, in any order.

See Appendix A for the full list of journals and proceedings covered in step 9.

3.2. Inclusion screening

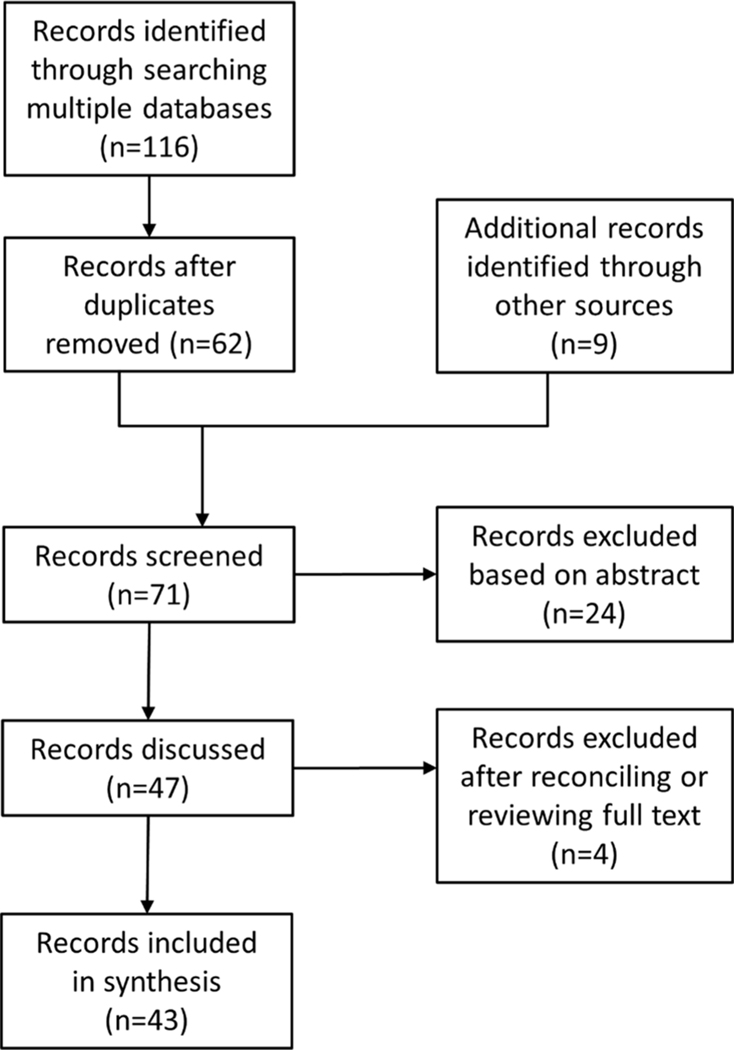

Given that the search strategy already limited to informatics publication sources, the primary screening criterion was whether each candidate article pertained to MPV. Two reviewers (SS and JWF) independently reviewed the article abstracts. All disagreements and requests to review in full text (by either reviewer) were retrieved and further adjudicated by involving another reviewer (SM). All three reviewers discussed and examined the full texts as needed to reach a consensus set for the thematic analysis and synthesis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Article screening process and the intermediate counts.

3.3. Content analysis and synthesis

The metadata (e.g., publication year and journal title) was directly recorded from the database search results. As part of the first-round screening, the two reviewers (SS and JWF) also assigned topic labels to the included articles when feasible. Based on the initial labeling, all three reviewers discussed and derived a set of pertinent aspects to annotate for the synthesis. The last author (JWF) then performed the annotation on the final included articles. The extracted attributes and themes were iteratively refined via group discussions. All the authors contributed to framing the interpretation and presentation of the results.

A fulfilled checklist of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [17] is available in Appendix B. As a recommended practice, we used the checklist in reporting the results to enhance transparency and reproducibility (e.g., sharing the exact search strategy and source databases).

4. Results

4.1. The included articles and metadata statistics

The database search identified 62 distinct articles, with 9 additional ones obtained from authors’ files or referred by colleagues, of which 43 articles were included into the final synthesis. Most eligible studies were from the US (n = 21; Table 2), and almost half (n = 21, 49%) were published in conference proceedings (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Source countries where the studies were conducted.

| Country of study | Count |

|---|---|

|

| |

| USA | 21 |

| France | 7 |

| Italy | 5 |

| Netherlands | 4 |

| Sweden | 1 |

| Spain | 1 |

| UK | 1 |

| South Korea | 1 |

| China | 1 |

| New Zealand | 1 |

| Sum | 43 |

Fig. 2.

Journal or conference of the publication (N = 43). AMIA: Proceedings of the AMIA Annual Symposium, Medinfo: Proceedings of the Medinfo (Studies in Health Technology & Informatics), IJMI: International Journal of Medical Informatics, JBI: Journal of Biomedical Informatics, MIDM: BMC Medical Informatics & Decision Making, JAMIA: Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, IPC: Informatics in Primary Care, PNAS: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, ACI: Applied Clinical Informatics, MIIM: Medical Informatics & the Internet in Medicine, JMIR: Journal of Medical Internet Research.

4.2. Attributes of the reported studies

4.2.1. Clinical conditions

Among the final 43 included studies, 11 (25.6%) dealt with multiple clinical conditions, 7 (16.3%) did not specify the clinical condition, and each remaining study involved one condition. Breast cancer was the most frequent condition (5 studies), of which 4 were published from the French OncoDoc2 project. All the remaining conditions were covered by only one or two studies, including trauma, pressure ulcer, type 2 diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, and soft tissue sarcoma. Notably, only 5 (11.6%) of the articles reported the effect of MPV on patient outcomes.

4.2.2. Clinical tasks

Treatment variation, e.g., varying prescription patterns, was the most studied (n = 24) clinical task in MPV (Fig. 3). The second and third most frequent clinical tasks pertained to variation in care pathways (n = 6) and the use of diagnostic tests (n = 5).

Fig. 3.

Clinical tasks involved in the informatics MPV studies. Note that one study can deal with multiple clinical tasks; see Appendix C for the exact clinical task(s) that each study covered. N/A = not applicable.

4.2.3. Study size

The sample sizes of the studies are summarized in Table 3. Note that the unit of sample size may vary, e.g., a study might investigate some MPV based on a cohort of patients or providers. There were 6 studies that did not report the study size due to the nature of being a conceptual model or review article. Besides, 3 studies used the number of clinical “decisions” made (i.e., variation across the decisions), so we were unable to obtain the exact numbers of clinicians and patients involved. For those with reported numbers of patients or providers, we see a wide range from a single digit to hundreds of millions.

Table 3.

Sample sizes of the included informatics MPV studies.

| Sample size reporting unit | Number of studies | Median study size (range) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Not reported | 6 | Not reported |

| Patient | 22 | 371.5 (1–250 million) |

| Provider | 12 | 77 (16–808020) |

| Decision | 3 | 1624 (199–1889) |

4.2.4. Roles of informatics

In Fig. 4, we can see that 39 out of the 43 informatics studies dealt with the detection of MPV (i.e., showing that variation exists), followed in frequency by characterizing (identifying associated contexts, n = 29) and explaining (asserting causal relations with specific variables, n = 11) the variation. Only 5 studies were about the development of informatics solutions to prevent MPV, and 4 studies sought to exploit (learn from) the detected MPV, e.g., apply data mining to derive new CPG rules based on real-world practice [18]. We did not assign any role of informatics for the three review articles.

Fig. 4.

Roles that informatics played in studying MPV. Note that in one study informatics can serve multiple roles; see Appendix C for details. N/A = not applicable.

4.3. Thematic analysis

We organized the 43 articles into five themes and several sub-themes (Table 4), each elaborated in the following subsections.

Table 4.

The derived themes and sub-themes.

| Theme | Sub-themes |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Conceptual modeling or methodology design | (1.a) Algorithm development [19–24] (1.b) HL7 message analysis [25] (1.c) Clarity of CGP language use [26] |

| CDSS implementation and evaluation | (2.a) Action research [27] (2.b) Implementation trial [28–32] (2.c) Analysis of adherence to recommendations [33–36] (2.d) User satisfaction analysis [37] |

| Characterizing practice patterns | (3.a) Specialty bias [38] (3.b) Simulated patients [39,40] (3.c) Knowledge discovery by machine learning [18,41,42] (3.d) Field study [43,44] (3.e) Visual analytics [45,46] (3.f) Telemedicine [47,48] (3.g) Clinical documentation [49] |

| Literature review and synthesis | (4.a) Reasons for intended MPV [13] (4.b) Advice for CDSS implementation [50] (4.c) Advice for MPV research in informatics [11] |

| Retrospective auditing of compliance with CPG | (5.a) Machine-assisted chart review [51–53] (5.b) Factors associated with CPG noncompliance [54–58] |

1. Conceptual modeling or methodology design

1.a). Algorithm development:

Metfessel [22] conceived a guideline compliance scoring system that takes claims data as input and scores a clinician’s level of compliance with CPG. The system relies on a knowledge base with disease-specific criteria and features a design of penalizing systematic, recurrent noncompliance heavier than sporadic incidents. Advani, Lo, and Shahar [20] proposed a guideline representation language, Asbru, which allows modeling guideline rules and their underlying justifications. A critiquing algorithm was designed to work with Asbru in assessing compliance, where a deviant action may be deemed acceptable if the clinician entered a justification aligned with the guideline rule. In a subsequent study, Advani, Goldstein, and Musen [19] further enhanced the Asbru-based solution by incorporating fuzzy measures into the compliance scoring. The adaptive approach considered uncertainty in the guideline evidence and allowed customization to a specific patient population. Muro, Larburu, Bouaud et al. [23] proposed an experience-based CDSS framework, in which a noncompliant practice can be promoted as a new recommendation if it consistently yields good outcomes. The learning process also captures the relevant patient attributes on which a clinician’s know-how is based. With a focus on measuring adherence to clinical pathways (guideline-recommended sequence of actions), van de Klundert, Gorissen, and Zeemering [24] devised a dynamic programming approach to calculating the degree of alignment between the actual sequence of activities a patient received versus the recommended sequence. Tackling a more complicated setting where clinical pathways need to consider stage-wise recommendations corresponding to disease progression, Li, Liu, Zhang et al. [21] used a hidden Markov model to first identify the most probable underlying stage of each activity in a patient’s care trajectory and then determine whether it is guideline- compliant per that specific context.

1.b). HL7 message analysis:

Konrad, Tulu, and Lawley [25] proposed the use of Health Level Seven (HL7) messages as a ubiquitous and timely data source for monitoring MPV. Their solution featured extraction of patient outcomes also from the HL7 messages to present meaningful feedback.

1.c). Clarity of CPG language use:

Codish & Shiffman [26] proposed a conceptual model to define and categorize ambiguity and vagueness in CPG language. The goal was to facilitate solutions that enhance the clarity with which guidelines are written and therefore reduce practice variation caused by divergent interpretation.

2. CDSS implementation and evaluation

2.a). Action research:

de Lusignan, Singleton, and Wells [27] applied action research [59] methods (workshops, questionnaires, and clinical audit) to evaluate the implementation of an anticoagulation CDSS in primary care. Practice variation was characterized, and the participating nurses indicated that stressful tension frequently arose when their judgment disagreed with the system recommendation.

2.b). Implementation trial:

Several trials were conducted to implement and assess how CDSS may reduce MPV in primary care (Bindels, Hasman, Kester et al. [28]; Martens, van der Weijden, Severens et al. [29]; Séroussi, Falcoff, Sauquet et al. [32]) or in clinical specialties (Panzarasa, Quaglini, Micieli et al. [30]; Séroussi, Bouaud, Gligorov et al. [31]). In general, the results showed the systems to be beneficial.

2.c). Analysis of adherence to recommendations:

Balas, Li, Spencer et al. [34] implemented a knowledge-based system to monitor MPV such as overutilization of procedures. Agrawal & Mayo-Smith [33] showed overall high compliance rates to CDSS reminders at the Veterans Affairs, but the compliance varied widely depending on the clinicians or specific guidelines. Beeler, Orav, Seger et al. [35] quantified the rates of overriding CDSS prescription warnings and found variation across the providers and topic domains. Sward, Orme Jr., Sorenson et al. [36] investigated the reasons that nurses declined CDSS reminders and identified issues related to applicability or usability.

2.d). User satisfaction analysis:

Quaglini, Grandi, Baiardi et al. [37] evaluated nurses’ satisfaction in using a CDSS for pressure ulcer prevention. The users acknowledged improvement in planning and documentation but complained about the rigid patient risk assessment and task completion requirements imposed by the system.

3. Characterizing practice patterns

3.a). Specialty bias:

Hashem, Chi, and Friedman [38] demonstrated that MPV could be rooted in clinician’s training. Through think-aloud analysis and general linear modeling, they found the clinicians tend to “pull” diagnosis decisions toward their own specialties.

3.b). Simulated patients:

Parry, Parry, and Pattison [40] created a set of simulated clinical cases and presented to obstetricians for eliciting their decision rules on whether to administer induced labor or not. When applied to a real obstetrics cohort, they found the variance of induction rate ranged widely. Using simulated cases with different background conditions (e.g., hypertension on beta-receptor antagonist), Ellervall, Brehmer, Knutsson et al. [39] surveyed general dentists’ confidence in administering antibiotic prophylaxis. Overall, the subjects exhibited high confidence in their decisions, but interestingly the clarity of different guidelines was not correlated with the level of confidence.

3.c). Knowledge discovery by machine learning:

Sboner and Aliferis [41] used support vector machine to model diagnosis decision-making in dermatology, followed by regression tree induction for deriving explainable rules. The methods revealed MPV across the physicians and occasionally against CPG. Toussi, Lamy, Le Toumelin et al. [18] applied the C5.0 decision tree algorithm to induce empirical prescription rules from EHR, specifically for circumstances not covered by CPG recommendations. They found that sometimes the physicians’ knowledge was ahead of extant guidelines. Noshad, Rose, and Chen [42] developed a graphical process mining method to identify practice patterns from EHR event log data. Their method can summarize the common care pathways and measure the variability of individual pathways against the majority.

3.d). Field study:

Kahol, Vankipuram, Patel et al. [43,44] conducted field observation to record the clinicians’ sequential activities at a trauma center. By comparing to a recommended protocol, the MPV demonstrated not only unwarranted errors but also some innovations that reflected sensible judgment especially by more experienced clinical staff.

3.e). Visual analytics:

Hripcsak, Ryan, Duke et al. [45] implemented a sunburst chart approach to visualizing the differential treatment pathways aggregated over millions of patients in the Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics (OHDSI) network. Rosenberg, Fucile, White et al. [46] applied t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) to visualize the prescription patterns using Medicare Part D claims data and reported substantial variation across specialties and regions.

3.f). Telemedicine:

Liu, Edson, Gianforcaro et al. [47] applied multivariate analysis that revealed physician- and encounter-specific characteristics associated with varying prescription behaviors widely across virtual care providers. Schweiberger, Hoberman, Iagnemma et al. [48] conducted a retrospective analysis to understand the telemedicine utilization in pediatrics during the COVID-19 pandemic. They used EHR data from a large pediatric primary care network and summarized the variation across different providers regarding the utilization rate, provider characteristics, patient demographics, and frequent diagnoses.

3.g). Clinical documentation:

Dey, Wang, Byrd et al. [49] used text mining and hierarchical clustering to analyze the signs and symptoms documented in EHR notes. Three groups of primary care physicians were identified with distinct documentation behaviors, which were not explained by either disease burden or medication use.

4. Literature review and synthesis

4.a). Reasons for intended MPV:

Arts, Voncken, Medlock et al. [13] performed a systematic review on intentional CPG nonadherence. A total of 16 studies were included, and 7 of them reported assessing appropriateness of the nonadherent incidents. Among those 7 studies, 3 reported that above 80% of the nonadherence to be appropriate (e.g., accommodating patient preference), plus 1 study that stated “large proportion” as appropriate without specifying the actual percentage. No outcome assessment regarding the intended nonadherence was summarized in their review.

4.b). Advice for CDSS implementation:

Morris, Stagg, Lanspa et al. [50] reviewed MPV issues especially in the context of EHR and the value of evidence-based CDSS tools (or referred to as eActions) for reducing MPV. They summarized seven elements (e.g., usability and iterative refinement) for successful implementation of the eActions.

4.c). Advice for MPV research in informatics:

Partially a review and partially conceptual modeling, Holzemer and Reilly [11] summarized the significance, stakeholders, and methodological challenges for informatics research on MPV. The seminal work formally introduced MPV to the informatics community along with valuable advice.

5. Retrospective auditing of compliance with CPG

5.a). Machine-assisted chart review:

Toussi, Ebrahiminia, Toumelin et al. [53] used a rule-based program to compare clinician’s prescriptions in a type 2 diabetes cohort versus CPG-recommended treatments. Cho, Park, and Chung [51] leveraged an EHR system with standardized nursing terminology to audit the MPV among nurses administering preventive care for pressure ulcer patients. Using a retrospective quality reporting registry and clinical data warehouse, Sims, Dale, Johnson et al. [52] identified MPV in prescribing antibiotics for community-acquired pneumonia. Compliance with CPG was found to correlate with better outcomes and lower costs.

5.b). Factors associated with CPG noncompliance:

By analyzing CDSS logs, Waks, Goldbraich, Farkash et al. [58] studied the treatment MPV in adult soft tissue sarcoma. They found that deviation from CPG was associated with disease attributes such as metastasis. In a subsequent study [56], the group refined their methods by including natural language processing and treatment sequence comparison to further understand the factors that drove deviation from the CPG. Bouaud and Séroussi [55] proposed a conceptual model for clinical decision-making and formulized major reasons for noncompliance with CPG, including the clinicians’ subjective assessment of the patient, inadequate coverage of the guidelines, and patient preferences. In two follow-up studies, the team explored formal concept analysis [54] and association rule mining [57] methods to identify those factors behind noncompliance.

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of key findings

In their 1973 seminal paper on practice variation, Wennberg and Gittelsohn [15], echoed later by Bakken [12], advocated for “a population-based health information system” to monitor MPV and inform policymaking. Since the 1995 review paper by Holzemer and Reilly [11], the informatics discipline has made modest contributions to MPV research, often published in preliminary format, and not fully engaging with MPV as an area of investigation and innovation. One hypothesis for the lack of engagement was that informatics is more method-driven versus the HSR discipline is more problem-driven, in which MPV as a problem could more likely take a central stage. There have been few studies on how MPV affected patient outcomes, likely due to the challenges in measuring outcomes or the sensitive nature of reporting outcomes as a result from MPV in health organizations. Our analysis of the roles that informatics played indicates the existing studies paid considerable attention to detecting MPV, but less to advanced endeavors such as generating reusable knowledge from the MPV. One caveat in interpreting the relatively few studies on knowledge generation (see the exploit role in Fig. 4) though, is that the small proportion may still top that in other disciplines that do not at all try to induce knowledge from MPV. The comparison would require surveying the literature of other disciplines and is beyond this scoping review.

The identified themes and sub-themes demonstrate a wide spectrum of research topics and techniques, including several sizable clusters on the development of algorithms for detecting MPV, prospective trials that assessed how the implementation of CDSS might reduce MPV, and the application of automated rules to audit MPV in retrospective EHR data. Note that the distribution of the sub-themes should be viewed as a discovery itself instead of validation, since our scoping review was not hypothesis driven. The hindsight might allude that adding “CDSS” upfront would have yielded higher recall, but such a strategy would untowardly bias the result by presuming that informatics research on MPV must involve CDSS. Moreover, the purposeful focus within informatics journals and conferences allowed our review to faithfully represent work that chose an informatics publication route plus referring to MPV as its subject – we see this a unique sample that captured the authors’ intention regarding both the “what” and “where” to publish an MPV-related study.

Our scoping review has found several opportunity areas for informatics research on MPV. As a strength of informatics, recent advances in intelligent analytics hold great promise for eliciting the context and decision process that justify warranted deviant practices in care. A critical task is to reliably capture patient outcomes in the loop and establish causal relations with MPV, as informatics moves toward answering the key questions of “why” and “how” certain MPV leads to better care quality and outcomes. An area of further exploration is the contribution that the personal and socioeconomic situation of each patient and their goals, priorities, values, and preferences make to MPV. Their role could be important even in situations where the variation may appear unwarranted as clinicians work with patients to make care fit [60]. Another vital area that demands informatics research is to examine the legal or ethical implications when computer algorithms get involved in regulating MPVs. Technology itself is not sufficient to make judgments but complicates the arena by adding another artificial agent on top of the many stakeholders.

5.2. Limitations

Given that MPV is not a concrete subject in the discipline of informatics, we were aware that our search strategy could not exhaust the naming variation itself and therefore could miss studies that were called differently. Although multiple sub-themes around CDSS have been identified (Table 4), our approach likely left out a swath of CDSS research tangent to MPV. There are other ways that informatics interacts with the field of MPV, but we chose to focus on studies mentioning about guideline, protocol, recommendation, or best practice. In addition, the informatics discipline has gradually ventured into a wider variety of publication paths, so the primary informatics journals and conferences would not fully represent the discipline’s identity. We recognize the thematic synthesis could not be free from our subjective interpretations.

6. Conclusion

We performed a scoping review to understand how informatics has contributed to MPV research. The results reveal that the informatics field has investigated heavily around the detection of treatment variation and deviation from recommended practice. The effect of MPV on patient outcomes has been under-studied. Methodological advances and the availability of big data in health care make now the prime time for informatics research to elevate its contribution toward explaining, preventing, and learning from MPV.

Supplementary Material

Summary table.

What was known on the topic:

Medical practice variation (MPV) is a significant issue in both clinical practice and research.

MPV has been a well-established subject in health services research and appears to be of interest to some informatics researchers.

What the study added to our knowledge:

The informatics discipline has made modest contributions to MPV research during 1995–2021, without exhibiting maturity of treating MPV as a prime area of investigation.

There were few informatics studies on how MPV affected patient outcomes and few on generating knowledge from the MPV.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the support from the Mayo Clinic Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery.

Funding

This study was partially supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health AI142702 and AG068007.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2022.104833.

References

- [1].Lay-Yee R, Scott A, Davis P, Patterns of family doctor decision making in practice context. What are the implications for medical practice variation and social disparities? Soc. Sci. Med 76 (2013) 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wennberg JE, Unwarranted variations in healthcare delivery: implications for academic medical centres, BMJ 325 (7370) (2002) 961–964, doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7370.961[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Krumholz HM, Variations in health care, patient preferences, and high-quality decision making, JAMA 310 (2) (2013) 151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Horwitz RI, Hayes-Conroy A, Caricchio R, Singer BH, From evidence based medicine to medicine based evidence, Am. J. Med 130 (11) (2017) 1246–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tomson CRV. ,van der Veer SN, Learning from practice variation to improve the quality of care, Clin. Med 13 (1) (2013) 19–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bach PB, A map to bad policy — hospital efficiency measures in the dartmouth atlas, N. Engl. J. Med 362 (7) (2010) 569–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].The Wennberg International Collaborative Data Statement, Secondary The Wennberg International Collaborative Data Statement. <https://wennbergcollaborative.org/data-statement/>.

- [8].Atsma F, Elwyn G, Westert G, Understanding unwarranted variation in clinical practice: a focus on network effects, reflective medicine and learning health systems, Int. J. Qual. Health Care 32 (4) (2020) 271–274, doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzaa023[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Reschovsky JD, Rich EC, Lake TK, Factors contributing to variations in physicians’ use of evidence at the point of care: a conceptual model, J. Gen. Intern. Med 30 (S3) (2015) 555–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hlatky MA, DeMaria AN, Does practice variation matter? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 62 (5) (2013) 447–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Holzemer WL, Reilly CA, Variables, variability, and variations research: implications for medical informatics, J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc 2 (3) (1995) 183–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bakken S, An informatics infrastructure is essential for evidence-based practice, J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc 8 (3) (2001) 199–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Arts DL, Voncken AG, Medlock S, Abu-Hanna A, van Weert HCPM, Reasons for intentional guideline non-adherence: a systematic review, Int. J. Med. Inf 89 (2016) 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Glover JA, The incidence of tonsillectomy in school children, Int. J. Epidemiol 37 (1) (2008) 9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wennberg J, Gittelsohn A, Small area variations in health care delivery: a population-based health information system can guide planning and regulatory decision-making, Science 182 (4117) (1973) 1102–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Adler-Milstein J, Health informatics and health services research: reflections on their convergence, J Am Med Inform Assoc 26 (10) (2019) 903–904, doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocz080[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Godfrey CM, Macdonald MT, Langlois EV, Soares-Weiser K, Moriarty J.o., Clifford T, Tunçalp Ö, Straus SE, PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation, Ann. Intern. Med 169 (7) (2018) 467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Toussi M, Lamy J-B, Le Toumelin P, Venot A, Using data mining techniques to explore physicians’ therapeutic decisions when clinical guidelines do not provide recommendations: methods and example for type 2 diabetes, BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Making 9 (1) (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Advani A, Goldstein M, Musen MA, A framework for evidence-adaptive quality assessment that unifies guideline-based and performance-indicator approaches, in: Proceedings/AMIA 2002; Annual Symposium, pp. 2–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Advani A, Lo K, Shahar Y, Intention-based critiquing of guideline-oriented medical care, in: Proc. AMIA Symp 1998; Annual Symposium, pp. 483–487. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Li X, Liu H, Zhang S, et al. , Automatic variance analysis of multistage care pathways, Stud. Health Technol. Inform 205 (2014) 715–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Metfessel BA, An automated tool for an analysis of compliance to evidence-based clinical guidelines, Stud. Health Technol. Inform 84 (Pt 1) (2001) 226–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Muro N, Larburu N, Bouaud J, Seroussi B, Weighting experience-based decision support on the basis of clinical outcomes’ assessment, Stud. Health Technol. Inform 244 (2017) 33–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].van de Klundert J, Gorissen P, Zeemering S, Measuring clinical pathway adherence, J. Biomed. Inform 43 (6) (2010) 861–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Konrad R, Tulu B, Lawley M, Monitoring adherence to evidence-based practices: a method to utilize HL7 messages from hospital information systems, Appl. Clin. Inform 04 (01) (2013) 126–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Codish S, Shiffman RN, A model of ambiguity and vagueness in clinical practice guideline recommendations, in: AMIA; 2005; Annual Symposium Proceedings/AMIA Symposium, pp. 146–150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].de Lusignan S, Singleton A, Wells S, Lessons from the implementation of a near patient anticoagulant monitoring service in primary care, Inform. Prim. Care 12 (1) (2004) 27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bindels R, Hasman A, Kester AD, Talmon JL, De Clercq PA, Winkens RAG, The efficacy of an automated feedback system for general practitioners, Inform. Prim. Care 11 (2) (2003) 69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Martens JD, van der Weijden T, Severens JL, de Clercq PA, de Bruijn DP, Kester ADM, Winkens RAG, The effect of computer reminders on GPs’ prescribing behaviour: a cluster-randomised trial, Int. J. Med. Inf 76 (2007) S403–S416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Panzarasa S, Quaglini S, Micieli G, et al. , Improving compliance to guidelines through workflow technology: implementation and results in a stroke unit, Stud. Health Technol. Inform 129 (Pt 2) (2007) 834–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Seroussi B, Bouaud J, Gligorov J, Uzan S, Supporting multidisciplinary staff meetings for guideline-based breast cancer management: a study with OncoDoc2, in: AMIA; 2007; Annual Symposium Proceedings/AMIA Symposium, pp. 656–660. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Seroussi B, Falcoff H, Sauquet D, Julien J, Bouaud J, Role of physicians’ reactance in e-iatrogenesis: a case study with ASTI guiding mode on the management of hypertension, AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings/AMIA Symposium 2010 (2010) 737–741. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Agrawal A, Mayo-Smith MF, Adherence to computerized clinical reminders in a large healthcare delivery network, Stud. Health Technol. Inform 107 (Pt 1) (2004) 111–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Balas EA, Li ZR, Spencer DC, Jaffrey F, Brent E, Mitchell JA, An expert system for performance-based direct delivery of published clinical evidence, J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc 3 (1) (1996) 56–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Beeler PE, Orav EJ, Seger DL, Dykes PC, Bates DW, Provider variation in responses to warnings: do the same providers run stop signs repeatedly? J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc 23 (e1) (2016) e93–8, doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv117[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sward K, Orme J, Sorenson D, Baumann L, Morris AH, Reasons for declining computerized insulin protocol recommendations: application of a framework, J. Biomed. Inform 41 (3) (2008) 488–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Quaglini S, Grandi M, Baiardi P, et al. , A computerized guideline for pressure ulcer prevention, Int. J. Med. Inf 58–59 (2000) 207–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hashem A, Chi MTH, Friedman CP, Medical errors as a result of specialization, J. Biomed. Inform 36 (1–2) (2003) 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ellervall E, Brehmer B, Knutsson K, How confident are general dental practitioners in their decision to administer antibiotic prophylaxis? A questionnaire study, BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Making 8 (1) (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Parry DT, Parry EC, Pattison NS, An online tool for investigating clinical decision making, Med. Inform. Intern. Med 29 (1) (2004) 75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sboner A, Aliferis CF, Modeling clinical judgment and implicit guideline compliance in the diagnosis of melanomas using machine learning, in: AMIA; 2005; Annual Symposium Proceedings/AMIA Symposium, pp. 664–668. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Noshad M, Rose CC, Chen JH, Signal from the noise: A mixed graphical and quantitative process mining approach to evaluate care pathways applied to emergency stroke care, J. Biomed. Inform 127 (2022) 104004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kahol K, Vankipuram M, Patel VL, Smith ML, Deviations from protocol in a complex Trauma environment: errors or innovations? J. Biomed. Inform 44 (3) (2011) 425–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Vankipuram M, Ghaemmaghami V, Patel VL, Adaptive behaviors of experts in following standard protocol in trauma management: implications for developing flexible guidelines, AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings/AMIA Symposium 2012 (2012) 1412–1421. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Hripcsak G, Ryan PB, Duke JD, Shah NH, Park RW, Huser V, Suchard MA, Schuemie MJ, DeFalco FJ, Perotte A, Banda JM, Reich CG, Schilling LM, Matheny ME, Meeker D, Pratt N, Madigan D, Characterizing treatment pathways at scale using the OHDSI network, PNAS 113 (27) (2016) 7329–7336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Rosenberg A, Fucile C, White RJ, Trayhan M, Farooq S, Quill CM, Nelson LA, Weisenthal SJ, Bush K, Zand MS, Visualizing nationwide variation in medicare Part D prescribing patterns, BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Making 18 (1) (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Liu S, Edson B, Gianforcaro R, Saif K, Multivariate analysis of physicians’ practicing behaviors in an urgent care telemedicine intervention, AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc 2019 (2019) 1139–1148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Schweiberger K, Hoberman A, Iagnemma J, et al. , Practice-level variation in telemedicine use in a pediatric primary care network during the COVID-19 pandemic: Retrospective analysis and survey study, J. Med. Int. Res 22 (12) (2020) (no pagination) doi: 10.2196/24345[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Dey S, Wang Y, Byrd RJ, et al. , Characterizing physicians practice phenotype from unstructured electronic health records, AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc 2016 (2016) 514–523. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Morris AH, Stagg B, Lanspa M, et al. Enabling a learning healthcare system with automated computer protocols that produce replicable and personalized clinician actions. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc 2021;28(6):1330–44 10.1093/jamia/ocaa294[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Cho InSook, Park H-A, Chung E, Exploring practice variation in preventive pressure-ulcer care using data from a clinical data repository, Int. J. Med. Inform 80 (1) (2011) 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Sims SA, Dale JA, Johnson TJ, Christensen K, Ward E, Electronic quality measurement predicts outcomes in community acquired pneumonia, in: AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings/AMIA Symposium, 2012, pp. 876–881. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Toussi M, Ebrahiminia V, Le Toumelin P, Cohen R, Venot A, An automated method for analyzing adherence to therapeutic guidelines: application in diabetes, Stud. Health Technol. Inform 136 (2008) 339–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Bouaud J, Messai N, Laouenan C, Mentre F, Seroussi B, Elicitating patient patterns of physician non-compliance with breast cancer guidelines using formal concept analysis, Stud. Health Technol. Inform 180 (2012) 477–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Bouaud J, Seroussi B, Revisiting the EBM decision model to formalize non- compliance with computerized CPGs: results in the management of breast cancer with OncoDoc2, in: AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings/AMIA Symposium, 2011, pp. 125–134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Goldbraich E, Waks Z, Farkash A, et al. , Understanding Deviations from clinical practice guidelines in adult soft tissue Sarcoma, Stud. Health Technol. Inform 216 (2015) 280–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Seroussi B, Soulet A, Messai N, Laouenan C, Mentre F, Bouaud J, Patient clinical profiles associated with physician non-compliance despite the use of a guideline-based decision support system: a case study with OncoDoc2 using data mining techniques, in: AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings/AMIA Symposium, 2012, pp. 828–837. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Waks Z, Goldbraich E, Farkash A, et al. , Analyzing the “CareGap”: assessing gaps in adherence to clinical guidelines in adult soft tissue sarcoma, Stud. Health Technol. Inform 186 (2013) 46–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Hart E, Bond M, Action Research for Health and Social Care: A Guide to Practice, Open University Press, Buckingham; Philadelphia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Kunneman M, Montori V, Making care fit in the lives and loves of patients with chronic conditions, JAMA Netw. Open 4 (3) (2021) e211576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.