Keywords: acute renal failure, gene expression, open reading frames, sepsis

Abstract

Significance Statement

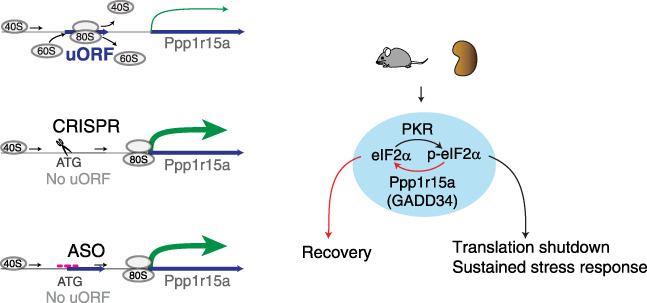

Extreme stress, such as life-threatening sepsis, triggers the integrated stress response and causes translation shutdown, a hallmark of late-phase, sepsis-induced kidney injury. Although a brief period of translation shutdown could be cytoprotective, prolonged translation repression can have negative consequences and has been shown to contribute to sepsis-induced kidney failure. Using a murine model of endotoxemia, the authors show that the duration of stress-induced translation shutdown in the kidney can be shortened by overexpressing protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 15A (Ppp1r15a, also known as GADD34), a key regulator of the translation initiation complex. They achieved overexpression of Ppp1r15a with genetic and oligonucleotide approaches, targeting its upstream open reading frame (uORF). Altering Ppp1r15a expression through its uORF to counter translation shutdown offers a potential strategy for the treatment of sepsis-induced kidney failure.

Background

Translation shutdown is a hallmark of late-phase, sepsis-induced kidney injury. Methods for controlling protein synthesis in the kidney are limited. Reversing translation shutdown requires dephosphorylation of the eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2) subunit eIF2α; this is mediated by a key regulatory molecule, protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 15A (Ppp1r15a), also known as GADD34.

Methods

To study protein synthesis in the kidney in a murine endotoxemia model and investigate the feasibility of translation control in vivo by boosting the protein expression of Ppp1r15a, we combined multiple tools, including ribosome profiling (Ribo-seq), proteomics, polyribosome profiling, and antisense oligonucleotides, and a newly generated Ppp1r15a knock-in mouse model and multiple mutant cell lines.

Results

We report that translation shutdown in established sepsis-induced kidney injury is brought about by excessive eIF2α phosphorylation and sustained by blunted expression of the counter-regulatory phosphatase Ppp1r15a. We determined the blunted Ppp1r15a expression persists because of the presence of an upstream open reading frame (uORF). Overcoming this barrier with genetic and antisense oligonucleotide approaches enabled the overexpression of Ppp1r15a, which salvaged translation and improved kidney function in an endotoxemia model. Loss of this uORF also had broad effects on the composition and phosphorylation status of the immunopeptidome—peptides associated with the MHC—that extended beyond the eIF2α axis.

Conclusions

We found Ppp1r15a is translationally repressed during late-phase sepsis because of the existence of an uORF, which is a prime therapeutic candidate for this strategic rescue of translation in late-phase sepsis. The ability to accurately control translation dynamics during sepsis may offer new paths for the development of therapies at codon-level precision.

Sepsis-induced kidney failure is a major life-threatening condition with no effective therapy. The current paradigm views inflammation as the centerpiece of early sepsis pathology.1–4 However, this paradigm falls short in connecting inflammation to kidney failure that is frequently observed in the late phase of sepsis. A crucial molecular event underpinning this transition is phosphorylation of the main translation regulator eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α).5 Phosphorylated eIF2α causes nearly all translation initiation processes to be stalled because phosphorylated eIF2α inhibits the guanosine triphosphate/guanosine diphosphate exchange required for recycling of eIF2 between successive rounds of initiation. Transient inhibition of protein synthesis could be cytoprotective because it attenuates energy consumption and upregulates the adaptive response to stress (the integrated stress response).6 Furthermore, reduced translation early in the course of sepsis may be beneficial because it limits the production of inflammatory cytokines. However, persistent inhibition of global protein synthesis is clearly detrimental.7,8 Indeed, we showed that pharmacologic reversal of translation shutdown in late-phase sepsis improves kidney function and recovery.5 In this manuscript, we investigate the molecular pathways involved in persistent translation shutdown during septic injury to the kidney.

In bacterial sepsis, we showed that the broad inflammatory response triggers antiviral pathways in many cell types, including renal epithelial cells.5,9 This antiviral component of bacterial sepsis leads to activation of EIF2AK2/PKR (protein kinase, IFN-inducible double-stranded RNA dependent; Supplemental Figure 1A). In turn, activated PKR phosphorylates eIF2α, causing translation shutdown.5,10,11 Reversal of translation shutdown requires dephosphorylation of eIF2α. This dephosphorylation is catalyzed by eIF2α holophosphatases that are composed of ubiquitous protein phosphatase 1 (PP1; catalytic subunit) bound to one of two regulatory subunits (PP1 regulatory subunit 15A [Ppp1r15a], also known as GADD34, and Ppp1r15b).12,13 Of the two regulatory subunits, only Ppp1r15a is induced by stress. Therefore, our central hypothesis is that insufficient induction of Ppp1r15a underlies sustained translation shutdown and kidney failure in sepsis.

Here, we report Ppp1r15a is translationally repressed during late-phase sepsis due to the existence of an upstream open reading frame (uORF) in the 5′ leader sequence of Ppp1r15a. Using genetic and oligonucleotide approaches, we characterize the significance of the uORF in blunting Ppp1r15a expression and causing sustained translation shutdown. We show that the Ppp1r15a uORF is a prime therapeutic candidate for this strategic rescue of translation in late-phase sepsis. Our work provides insights into how a single uORF can deeply affect the pathophysiology of sepsis and serves as a distinct layer of molecular regulation in health and disease.

Methods

Generation of PPP1R15A uORF Mutant Cell Lines

We designed single-guide RNA (sgRNA) and single-stranded oligo DNA nucleotides (ssODN; also known as homology-directed repair donor oligos [HDR]), and generated mutant HEK293T cell lines using the CRISPR/Cas9 system (Table 1). In all cases, target knock-in and PAM block14 (synonymous mutation) were introduced in the vicinity of the double-strand break (±10 bp). Cells were cultured in 10-cm plates to 70% confluency before nucleofection. Approximately 150 × 103 cells (5 µl) were mixed with 1.49 µl of ssODN (100 µM) and Cas9 complex consisting of 18 µl SF 4D-nucleofector X solution with Supplement 1 (V4XC-2012; Lonza), 6 µl of sgRNA (30 pmol/µl), 1 µl of Cas9 2NLS nuclease, and Streptococcus pyogenes (20 pmol/µl; Synthego). Nucleofection was done using Amaxa 4D-Nucleofector X (CM-130 program; Lonza). Cells were seeded in 15-cm plates at various concentrations. We performed manual clonal isolation. After clonal expansion and genotyping, we performed further subcloning in some cases to ensure purity. On average, the rate of successful biallelic HDR knock-in was approximately 10%–20%, and the rest of the clones showed a mixture of nonhomologous end joining and HDR knock-in. Less than 10% of clones showed no evidence of mutation at target sites. We used the Quick DNA Miniprep kit (catalog number D3025; Zymo Research) for DNA extraction. For PCR, we used Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB), PCR primers as listed in Table 1, and Monarch PCR Cleanup Kit (T1030; NEB). PCR products were electrophoresed in 2% agarose gel (TopVision Agarose Tablets R2801; Thermo Fisher), and bands were excised and extracted using QIAQuick Gel Extraction kit (catalog number 28706; Qiagen). GeneWiz performed the Sanger sequencing. Software used for design and analysis of mutant cell lines include CRISPRdirect, SnapGene, Primer3Plus, NEB Tm calculator, and Synthego ICE.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides

| Oligonucleotide Name and Sequence | Vendor | Identifier |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR sgRNA | ||

| Human PPP1R15A sgRNA U**G**A**GGGTGAGAUGAACGCGC |

Synthego | NA |

| Human PPP1R15A sgRNA (for polyproline and StrepII tag insertion) A**A**C**CGGCGCTCCTGCCCCCG |

Synthego | NA |

| Mouse Ppp1r15a sgRNA AGCGGGTTCATGTCGCCCTC |

JAX | NA |

| CRISPR ssODN (HDR template) | ||

| ssODN human PPP1R15A (no uORF) AGGCAGCCGGAGATACTCTGAGTTACTCGGAGCCCGACGCCTGAGGG TGAGCTCAACGCGCTCGCCTCCCTAACCGTCCGGACCTGTGATCGCTTC TGGCAG |

IDT | NA |

| ssODN human PPP1R15A (polyproline + StrepII tag) C*GGACCTGTGATCGCTTCTGGCAGACCGAACCGGCGCTCCTGCCCCCG GGTGGTTCAGCTTGGTCACATCCGCAGTTTGAAAAGTGACGCGCAGCT CCCAGCCGGTGAGTAAGGGGTCGGAACGCC*T |

IDT | NA |

| ssODN human PPP1R15A (no polyproline + StrepII tag) C*GGACCTGTGATCGCTTCTGGCAGACCGAACCGGCGCTCCTGGGCGGG GGTTCAGCTTGGTCACATCCGCAGTTTGAAAAGTGACGCGCAGCTCCCA GCCGGTGAGTAAGGGGTCGGAACGCCTGGGTC*C |

IDT | NA |

| ssODN mouse Ppp1r15a (no uORF) GATATCCCGCGCGACCCCGCATCCCTTTGCCGGCCGGGACAGCCTTTGCT ACAGCCTGTGAAACATTGCGTCCCCGAGCCCCACGCGTGAGGGCGACAT AAACCCGCTGGCTTCGCGAGCAGTCCGG |

JAX | NA |

| PCR primers | ||

| Human PPP1R15A Fwd: TCTTATGCAAGACGCTGCAC Rev: GTTCCGACCCCTTACTCACC |

IDT | NA |

| Human PPP1R15A Fwd: AACCGTCCGGACCTGTGA Rev: TGCTCCTTTTACTGCTTCCA |

IDT | NA |

| Mouse Ppp1r15a Fwd: TTGTGGAAGATTACATGCGATA Rev: AGAGAGTCCTCCCTCAAAGG |

IDT | NA |

| Human GAPDH Fwd: GTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCG Rev: ACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCAAA |

IDT | NA |

| ASO for uORF masking | ||

| Mouse Ppp1r15a ASO1 5′-mCmAmUmGmUmCmGmCmCmCmUmCmAmGmGmCmGmU-3′ |

IDT | NA |

| Mouse Ppp1r15a ASO2 5′-mUmGmCmUmCmGmCmGmAmAmGmCmCmAmGmCmGmG-3′ |

IDT | NA |

| Mouse Ppp1r15a ASO1 scramble 5′-mGmUmGmCmGmGmCmAmUmAmCmUmUmCmCmGmCmC-3′ |

IDT | NA |

| Mouse Ppp1r15a ASO2 scramble 5′-mCmCmGmCmGmAmGmCmGmGmUmAmAmGmUmGmCmC-3′ |

IDT | NA |

| Human PPP1R15A ASO1 5′-mCmAmUmCmUmCmAmCmCmCmUmCmAmGmGmCmGmU-3′ |

IDT | NA |

| Human PPP1R15A ASO2 5′-mGmUmUmAmGmGmGmAmGmGmCmCmAmGmCmGmCmG-3′ |

IDT | NA |

| Human PPP1R15A ASO1 scramble 5′-mUmCmCmAmAmUmCmGmCmUmCmUmGmAmCmGmCmC-3′ |

IDT | NA |

| Human PPP1R15A ASO1 scramble 5′-mCmGmCmGmAmAmCmGmGmUmGmGmCmGmGmAmGmU-3′ |

IDT | NA |

| Oligonucleotides for PPP1R15A pulldown | ||

| Biotin TEG-A+A+G*A*T*C*A*A*C*A*A*C*T*G*G*G*A*T+G+G | IDT | NA |

| Biotin TEG-A+T+C+A*A*A*A*G*G*C*T*T*T*A*T*T*C+C+T+T | IDT | NA |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1a-copGFP-T2A-Puro (cloning site NotI/KpnI) | Addgene | Catalog number 72263 |

| Mouse Ppp1r15a 5′ UTR (sequence below)—firefly luciferase—T2A—puro (pCDH backbone as above) AGCGCCGCGTCAGGGTATAAAAGCCGCGTGGACGATGTTGGCGCAGATT GAGTCAGCTCTGAGTTTGTGGAAGATTACATGCGATATCCCGCGCGACCC CGCATCCCTTTGCCGGCCGGGACAGCCTTTGCTACAGCCTGTGAAACATT GCGTCCCCGAGCCCCACGCCTGAGGGCGACATGAACCCGCTGGCTTCGCG AGCAGTCCGGACCCACGATCGCTTTTGGCAACCAGAACCGGCGCTTCAGCC CCCGGGGTGACGTGCAGCCCGCCGCCCAGACACATGGGATCC |

Pepmic | NA |

| Mouse Ppp1r15a mutant 5′UTR (sequence below)—firefly luciferase—T2A—puro (pCDH backbone) AGCGCCGCGTCAGGGTATAAAAGCCGCGTGGACGATGTTGGCGCAGATT GAGTCAGCTCTGAGTTTGTGGAAGATTACATGCGATATCCCGCGCGACCC CGCATCCCTTTGCCGGCCGGGACAGCCTTTGCTACAGCCTGTGAAACATTG CGTCCCCGAGCCCCACGCCTGAGGGCGACATAAACCCGCTGGCTTCGCGA GCAGTCCGGACCCACGATCGCTTTTGGCAACCAGAACCGGCGCTTCAGCC CCCGGGGTGACGTGCAGCCCGCCGCCCAGACACATGGGATCC |

Pepmic | NA |

| Human PPP1R15A 5′ UTR uORF2 only—twin StrepII (sequence below)—firefly luciferase—T2A—puro (pCDH backbone) GCTCTTATCGGTTCCCATCCCAGTTGTTGATCTTGTTACTCGGAGCCCGACG CCTGAGGGTGAGATGAACGCGCTGGCCTCCCTAACCGTCCGGACCTGTGA TCGCTTCTGGCAGACCGAACCGGCGCTCCTGCCCCCGGGGGGTGGTTCAG CTTGGTCACATCCGCAGTTTGAAAAGGGTGGTGGTTCAGGTGGTGGTTCA GGTGGTTCAGCTTGGTCACATCCGCAGTTTGAAAAGTGACGCGCAGCTCC CAGCCGCCAGACACATGGGATCC |

GenScript | NA |

| Human PPP1R15A 5′ UTR uORF2—twin StrepII—uORF1 (sequence below)—firefly luciferase—T2A—puro (pCDH backbone) GCTCTTATCGGTTCCCATCCCAGTTGTTGATCTTATGAACGCGCTGGCCTCC CTAACCGTCCGGACCTGTGATCGCTTCTGGCAGACCGAACCGGCGCTCCT GCCCCCGGGTGGTTCAGCTTGGTCACATCCGCAGTTTGAAAAGGGTGGTG GTTCAGGTGGTGGTTCAGGTGGTTCAGCTTCAGCTTGGTCACATCCGCAGT TTGAAAAGTGAGTTACTCGGAGCCCGACGCCTGAGGGTGAGATGCAAGAC GCTGCACGACCCCGCGCCCGCTTGTCGCCACGGCACTTGAGGCAGCCGGA GATACTCTGACGCGCAGCTCCCAGCCGCCAGACACATGGGATCC |

GenScript | NA |

| Human PPP1R15A 5′ UTR uORF2 only, no polyproline—twin StrepII (sequence below)—firefly luciferase—T2A—puro (pCDH backbone) GCTCTTATCGGTTCCCATCCCAGTTGTTGATCTTGTTACTCGGAGCCCGACG CCTGAGGGTGAGATGAACGCGCTGGCCTCCCTAACCGTCCGGACCTGTGA TCGCTTCTGGCAGACCGAACCGGCGCTCCTGGGCGGGGGGGGTGGTTCA GCTTGGTCACATCCGCAGTTTGAAAAGGGTGGTGGTTCAGGTGGTGGTTC AGGTGGTTCAGCTTGGTCACATCCGCAGTTTGAAAAGTGACGCGCAGCTC CCAGCCGCCAGACACATGGGATCC |

GenScript | NA |

| Human PPP1R15A 5′ UTR uORF2, no polyproline—twin StrepII—uORF1 (sequence below)—firefly luciferase—T2A—puro (pCDH backbone) GCTCTTATCGGTTCCCATCCCAGTTGTTGATCTTATGAACGCGCTGGCCTCC CTAACCGTCCGGACCTGTGATCGCTTCTGGCAGACCGAACCGGCGCTCCT GGGCGGGGGTGGTTCAGCTTGGTCACATCCGCAGTTTGAAAAGGGTGGT GGTTCAGGTGGTGGTTCAGGTGGTTCAGCTTCAGCTTGGTCACATCCGCAG TTTGAAAAGTGAGTTACTCGGAGCCCGACGCCTGAGGGTGAGATGCAAGA CGCTGCACGACCCCGCGCCCGCTTGTCGCCACGGCACTTGAGGCAGCCGG AGATACTCTGACGCGCAGCTCCCAGCCGCCAGACACATGGGATCC |

GenScript | NA |

mNmN, 2′-O-methyl RNA bases; NNN or NNN, key mutation sequence; sgRNA, single-guide RNA; NA, not applicable; **, 2′-O-methyl and phosphorothioate bond; JAX, The Jackson Laboratory; *, phosphorothioate bond; fwd, forward; rev, reverse; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; +, locked nucleic acids.

Generation of Ppp1r15a uORF Mutant Mouse Model

We designed the following sgRNA and ssODN to introduce uORF3 start codon mutation and PAM block14 within 10 bp from the double-strand break. We used an asymmetric donor DNA strategy15 (36 bp|cut|91 bp for the nontarget strand).

sgRNA: 5′-AGCGGGTTCATGTCGCCCTC-3′ (AGG/PAM) ssODN/HDR donor oligos:

5′-GATATCCCGCGCGACCCCGCATCCCTTTGCCGGCCGGGACAGCCTTTGCTACAGCCTGTGAAACATTGCGTCCCCGAGCCCCACGCGTGAGGGCGACATAAACCCGCTGGCTTCGCGAGCAGTCCGG-3′

Embryo manipulation and generation of founder mice on C57BL/6J background were performed by the Jackson Laboratory Mouse Model Generation Services. This mouse strain has been transferred to the Jackson Laboratory Repository (stock number 037609; C57BL/6-Ppp1r15a<em1Hato>/J).

Animals

Ppp1r15a uORF knock-in mice (uORF−/−, uORF+/−, and uORFWT littermates) were housed at Indiana University School of Medicine under a 12-hour light/dark cycle at 25°C. For studies that did not require the knock-in mice, C57BL/6J mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. All mice were 8–12 weeks of age and weighed 24–32 g. We used male mice unless indicated. Animals were subjected to a single-dose, 5 mg/kg endotoxin (LPS) tail vein intravenous injection (Escherichia coli serotype 0111:B4; MilliporeSigma). Untreated mice received an equivalent volume of sterile, normal saline vehicle. Cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) was performed under isoflurane anesthesia; 75% of the mouse cecum was ligated and punctured twice with a 25-gauge needle. Animals were resuscitated with 500 μl of normal saline intraperitoneally at the time of abdominal closure. No antibiotics were used. For in vivo antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) treatment, Ppp1r15a uORF-targeted oligonucleotides or corresponding scrambles (Table 1) were reconstituted in water (1 mM stock solution) and rediluted in sterile normal saline with a final volume of 300 µl for tail vein intravenous injection.

Cells

HEK293T cells and PPP1R15A uORF mutant cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS and 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Thermo Fisher). All cell types were cultured at 37°C with 5% carbon dioxide.

Transformation of E. coli and Transfection of HEK293T Cells

Chemically competent E. coli (One Shot Top10, catalog number C404003; Invitrogen) were transformed with pCDH plasmids (Table 1) using the heat-shock method (on ice for 30 minutes followed by 42°C heat shock for 45 seconds). Transformed E. coli were incubated overnight in LB broth with 100 µg/ml carbenicillin at 225 rpm, 37°C. We used the Nucleobond Xtra Midi Kit (catalog number 740410.50; Takara) for plasmid isolation, following the manufacture’s protocol. For DNA gel electrophoresis, 1% agarose gel was prepared using TopVision Agarose Tablets (R2801; Thermo Fisher) and GelGreen nucleic acid stain (catalog number 41005; Biotium). Samples were electrophoresed with NEB 6× gel loading dye in 0.5 times TAE buffer at 100 V. Transfection of plasmids was done using lipofectamine 2000, following the manufacturer’s instructions (sequential mixing of lipofectamine, Opti-MEM, and plasmid into freshly replaced DMEM/10% FBS medium; catalog number 11668027; Thermo Fisher). For all experiments, either 1 or 10 µg plasmid DNA was used per well of a six-well plate or 10-cm dish, respectively.

For poly(I:C) transfection, cells with 60%–80% confluency were transfected with synthetic double-stranded RNA poly(I:C) (high molecular weight; catalog number tlrl-pic; InvivoGen) using lipofectamine 2000 following the manufacture’s protocol. Final working concentrations of poly(I:C) ranged from 0.1 to 1.5 µg/ml. Cells were incubated for 1–16 hours and harvested for downstream analyses. In some experiments, other stress-inducing reagents were used (without transfection): 10 µg/ml tunicamycin (Sigma), 1 µM thapsigargin (Sigma), recombinant human IFN-γ protein (20 ng/ml; catalog number 285-IF; R&D Systems). For ASO transfection, we used Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Thermo Fisher) according to the manufacture’s protocol (80 nM of indicated ASOs for 6 hours).

Luciferase Assay

HEK293T cells were split on the previous day to result in 60%–80% confluency. Cells were transfected with 10 µg of pCDH-Ppp1r15a 5′ untranslated region (UTR; uORF3 start codon mutant)-luciferase-T2A-puroR or pCDH-Ppp1r15a 5′ UTR (WT)-luciferase-T2A-puroR constructs per 10-cm petri dish with lipofectamine 2000 overnight. Cells were split into 96-well plates at 50,000 cells per well in 200 µl DMEM without penicillin/streptomycin and allowed to adhere overnight. Detection of luciferase signal was done using the Bright Glo luciferase assay system (E2610; Promega). After cell incubation at 37°C, we read the luciferase luminescence signal using the CLARIOstar plate reader.

Polyribosomal Profiling

For polyribosome profiling of tissues, we performed cardiac perfusion using 6 ml of cycloheximide (100 μg/ml in PBS; Sigma). Harvested tissues were immediately placed in a lysis buffer consisting of 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% deoxycholate, 20 mM Tris–hydrogen chloride (Tris-HCl), 100 mM sodium chloride (NaCl), 10 mM magnesium chloride (MgCl2), EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablet (Roche), and 100 μg/ml cycloheximide. Tissues were homogenized using a Minilys tissue homogenizer (Bertin Instruments). Tissue homogenates were incubated on ice for 20 minutes, then centrifuged at 9600 × g for 10 minutes. The supernatant was added to the top of a sucrose gradient, generated by BioComp Gradient Master (10% sucrose on top of 50% sucrose in 20 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 100 μg/ml cycloheximide), and centrifuged at 283,800 × g for 2 hours at 4°C. The gradients were harvested from the top in a Biocomp harvester (Biocomp Instruments), and the RNA content of eluted ribosomal fractions was continuously monitored with ultraviolet absorbance at 254 nm. For polyribosome profiling of cultured cells, cells were rinsed with cold PBS first, and cells were then scraped using the lysis buffer on ice. The remaining procedure was identical to tissue polyribosome profiling.

Ribosome-Profiling Analysis

Since we reported our prior ribosome-profiling (ribosome-sequencing [Ribo-seq]) analysis,5 Illumina TruSeq RNase was discontinued. Consequently, we reoptimized our workflow, primarily focusing on the choice and condition of RNase digestion. RNase T1, S7 micrococcal nuclease, and RNase I were evaluated using polyribosomal profiling (enrichment of monosomal peak and disappearance of polysomes as a readout)16 and sequencing. We opted for RNase I because it has no sequence bias in its endonuclease activity. However, as reported by others,17 we also noted that ribosome footprint periodicity was not fully preserved with RNase I, possibly due to the aggressive nature of the enzyme. We also compared custom oligo-based ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion versus no rRNA depletion because Ribo-Zero Gold (Illumina) was discontinued as a standalone product.18 Although rRNA was depleted with the custom biotinylated oligos, the overall loss of ribosome-protected fragments was not negligible. Therefore, we did not include the depletion step in the following workflow.

Kidneys were snap frozen and pulverized under liquid nitrogen. Cryo-lysis was done using a Minilys tissue homogenizer in a polysome buffer (1 ml per one mouse kidney) consisting of 20 mM Tris pH 7.5 (140 µl of 1 M Tris 7.0 plus 60 µl of 1 M Tris 8.0 for 10 ml final buffer), 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate (D-6750; Sigma), dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.02 U/µl Turbo DNase (AM2238; Thermo Fisher), 200 µg/ml cycloheximide (Sigma), and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablet (Roche). Tissue lysates were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 minutes. Equal volumes of supernatant aliquots were made for Ribo-seq and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) workflows (200 µl each). Polysome digestion was performed using RNase I (AM2294; Thermo Fisher/Ambion) for 60 minutes at 4°C, and the reaction was stopped with 10 μl SUPERase In (AM2696; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Ribosome-protected fragments were isolated using microspin S-400 (GE HealthCare) following the manufacturer’s instruction. Microspin buffer consisted of 20 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, and 5 mM MgCl2. RNA fragments were purified using the TRIzol/chloroform method and chill precipitated in isopropanol (50% vol/vol), 0.3 M sodium acetate, and GlycoBlue overnight at −20°C. We next performed time-gated size selection using the Pippin HT system (7–28 minutes on 3% agarose; Sage Science). Size-selected RNA samples were purified using Zymo RNA Clean & Concentrator-5 kit (R1013; Zymo). The RNA 3′ end dephosphorylation reaction consisted of T4 PNK (20 U/10 μl sample; M0201S; NEB), SUPERase in 1× T4 PNK buffer without ATP for 60 minutes at 37°C. Adapter ligation was done using NEXTFLEX Small RNA-seq kit version 3 (NOVA-5132-05; PerkinElmer). After 3′ 4N adenylated adapter ligation and excess adapter inactivation (step C in the NEXTFLEX manual), 5′ end repair was done using T4 PNK with 2 mM ATP (P0756S; NEB). After RNA purification with Zymo Oligo Clean & Concentrator (D4060), we proceeded with the remaining NEXTFLEX steps through G following the manufacture’s manual. Library size selection for sequencing was done using the Pippin System (range mode, 135–190 bp). Sequencing was performed at Indiana University School of Medicine Medical Genomics Core using Illumina NovaSeq (single-end 75-bp reads). Cutadapt was used to trim adapters, including the four random oligonucleotides between each adapter and sample read. Reads were first aligned to rRNA followed by mapping to the rest of the mm10 reference genome using STAR and, in some cases, bowtie for transcriptome. Data analysis was done using multiple tools we previously described.5 Gedi PRICE19 was used for detection of ATG and non-ATG uORF genome wide and construction of a custom reference for MHC peptidomics. For determination of reads coverage, P-site, and periodicity, we used samtools, bedtools, awk, and the following R packages: RiboWaltz, GenomicRanges, IRanges, and BiocGenerics (https://github.com/hato-lab/uORF).

RNA-Seq

Kidneys were snap frozen and RNA was extracted using Zymo Direct-zol RNA kit. We determined RNA quality using Agilent Bioanalyzer (RNA integrity number values greater than seven). Sequencing was performed at the Indiana University Center for Medical Genomics Core, using 100 ng of total RNA. cDNA library preparation included mRNA capture/enrichment, RNA fragmentation, cDNA synthesis, ligation of index adaptors, and amplification, following the KAPA mRNA HyperPrep Kit Technical Data Sheet (KR1352, v4.17; Roche). Each resulting indexed library was quantified, its quality accessed by Qubit and Agilent Bioanalyzer, and multiple libraries were pooled in equal molarity. The pooled libraries were then denatured, and neutralized, before loading to the NovaSeq 6000 sequencer at 300 pM final concentration for 100-bp paired-end sequencing (Illumina). Approximately 40M reads per library was generated. Phred quality score (Q score) was used to measure the quality of sequencing. More than 90% of the sequencing reads reached Q30 (99.9% base call accuracy). The sequenced data were mapped to the mm10 genome using STAR. Uniquely mapped sequencing reads were assigned to mm10 refGene genes using featureCounts, and counts data were analyzed using edgeR.

MHC Peptidomics

The MHC-I molecules can bind and present intracellular protein fragments/peptides to the cell surface for immunosurveillance. The binding affinity between MHC-I and peptides is determined by the MHC haplotype (e.g., C57BL/6 harbors H-2Kb and H-2Db) and amino acid residues at specific positions (anchor residues; the length of peptides fitting into the MHC-I groove is largely restricted to eight to 12 residues). With the structural protection afforded by the MHC-I groove, unstable peptides, such as uORF-derived microproteins, acquire longer t1/2s and are over-represented in the repertoire of all peptides presented by the MHC-I molecules as compared with general mass spectrometry.20–22 The profiling of MHC-I–bound peptides (i.e., MHC peptidomics/immunopeptidomics) is increasingly used to catalog uORF-derived microproteins in conjunction with Ribo-seq.23

To harvest a large amount of mAbs against MHC-I haplotype H2-Kb, Y-3 hybridoma cells (HB-176; ATCC) were incubated in a membrane cell culture flask following the manufacturer’s instructions (CELLine Bioreactor Flask [Wheaton] and Hybridoma-SFM 12045076 [Thermo Fisher]). Crosslinking of Y-3 antibody and Protein A+G was done using sulfosuccinimidyl (4-iodoacetyl)aminobenzoate (Sulfo-SIAB; 22327; Thermo Fisher). For 1 ml of Protein A+G agarose (catalog number 20421; Thermo Fisher/Pierce), 1.5 ml of Y-3 antibody (0.5 mg/ml) was added and incubated at room temperature for 40 minutes. Next, Sulfo-SIAB (25 mM working concentration) was added and incubated for 30 minutes in the dark. Excess crosslinkers were removed by washing with 50 mM borate buffer (50 mM borate buffer, 5 mM EDTA, pH 8.5). The crosslinking reaction was quenched with 5 mM cysteine incubation at room temperature for 15 minutes in the dark. The crosslinked column was then washed with PBS. Mouse kidney tissues were lysed using Minilys (45 seconds at the highest speed) with the following buffer: 20 mM Tris pH 8, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 60 mM octyl glucoside (Sigma), 2 mM MgCl2, DNase I (0.1 U/µL; AM2222; Ambion), Benzonase (25 U/mL; 70746-4; EMD Millipore), 10 mM chloroacetamide (Sigma), cOmplete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma), and phosStop inhibitor (Roche). Samples were left on ice for 10 minutes and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 minutes. The supernatant was mixed with crosslinked Y-3 antibody and incubated for 2 hours at 4°C. The resin was washed with 10 column volumes of wash buffer (10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, and 0.1% Triton X-100), 10 column volumes of 10 mM Tris (pH 8), followed by water. MHC peptides were eluted from the resin by rocking for 1 hour at room temperature with 1 ml of 0.1 N acetic acid. Trifluoroacetic acid (0.5%) was added, and peptides were loaded onto Waters Sep-Pak Vac C18 cartridges (WAT054955; Waters), washed with 0.5% trifluoroacetic acid in water, and eluted in 1 ml 30% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid followed by 1 ml 60% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid. Samples were dried by speed-vac before liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry analysis. A third of each sample was injected using an Easynano LC1200 coupled with 25-cm Aurora column (AUR2-25075C18A; Ionopticks) on an Eclipse Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptides were eluted on an 84-minute gradient using 5%–30% B, increasing to 90% B over 9 minutes, and holding at 90% B for 5 minutes (solvent A, 0.1% formic acid; solvent B, 80% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid) following the protocol by Ouspenskaia et al.20 The instrument was operated with FAIMS pro 2 CVs (−50, −70 V), positive mode, and 1.5-second cycle time per CV with APD and Easy-IC on. Settings for each cycle were as follows: full scan, 300–1800 m/z with 120,000 resolution, standard AGC and 50 ms maximum IT, 30% RF lens, 5 × 104 intensity threshold, and 20-second dynamic exclusion. MS2 parameters were operated in a decision tree with charge states two to seven prioritized, precursor selection range of 300–1800 m/z, 1.1 m/z quadrupole isolation, 30% fixed HCD CE, 30000 orbitrap resolution, standard AGC, and dynamic IT. Charge states one and undetermined were the second branch with precursor selection of 800–1700 m/z with the same fragmentation settings as the previous branch. Data were analyzed in MSFragger/FragPipe using the default option for MHC peptidomics (“nonspecific-HLA,” closed search)24 except for peptide lengths, which were restricted to eight to 12 amino acids, and addition of STY phosphorylation as a variable modification. The reference FASTA file was prepared by combining the UniProt mouse reference (UP000000589_10090), common contaminants, custom uORF database (see below), and decoys (reverse sequence). Only top hit-rank peptides (hit rank=1) were subsequently analyzed using NetMHCpan4.1b for H2-Kb and H2-Db with default settings (rank threshold for strong binding peptides, 0.5; weak binding peptides, 2.0).25 Peptides with binding percentage rank <2.0 were further filtered for nine-mers and H2-Kb. Nonmetric multidimensional scaling was done using R packages motifStack, HDMD, and ecodist, as described by Sarkizova et al.26 seq2logo was used for nine-mer logo display. We performed Jaccard analysis using base R function (%in%) and heatmap3. Pathway analysis was done using pathfindR.

Regarding the custom uORF database, we built it on the basis of kidney Ribo-seq data,5 in which a model of endotoxin-induced kidney injury was applied, similarly to the peptidomics study. This allowed us to construct a condition-specific uORF database (https://github.com/hato-lab/uORF). Because non-ATG start codon use is pervasive in uORF, computational ORF prediction (canonic ATG start|TGA/TAA/TAG stop) does not capture a full spectrum of translated uORF. Thus, to systematically detect uORFs from Ribo-seq data, we used the Gedi PRICE pipeline.19 BAM files were converted to CIT files and detected ORFs were annotated according to PRICE ORF annotation types (https://github.com/erhard-lab/gedi/wiki/Price). uoORF, uORF, iORF, and dORF reads from the main output table (orfs.tsv) were reorganized and converted into a BED file. Transcription and translation of the BED file were done using bedtools (getfasta function) and faTrans.

Immunoprecipitation and Mass Spectrometry

Cells were lysed using the Minilys homogenizer with the following extraction buffer: 20 mM Tris pH 8, 100 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM MgCl2, DNase I (0.1 U/µl; AM2222; Ambion), Benzonase (25 U/ml; 70746-4; EMD Millipore), Halt protease inhibitors (Pierce), and phosStop inhibitor (Roche). For PP1 immunoprecipitation, supernatants were incubated with anti-PP1 antibody conjugated to agarose for 3 hours at 4°C (E-9, sc-7482 AC, 25% agarose; Santa Cruz). Samples were washed with washing buffer five times (20 mM Tris pH 8, 500 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 2 mM MgCl2). Samples were trypsin digested, desalted, and run on an Orbitrap Exploris 480 mass spectrometer with FAIMS. Pulldown of the StrepII tag was done according to the MagStrep-Tactin beads protocol (2-4090-002; IBA-Lifesciences). For pulldown of PPP1R15A mRNA and RNA-bound proteins, we followed the protocol described by Iadevaia et al.27 Cells were ultraviolet crosslinked and lysed in a buffer consisting of 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 500 mM lithium chloride, 10 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 5 mM DTT, 20 U/ml DNase I, SUPERase In, and cOmplete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail. We prepared 5′ biotin-TEG–modified antisense oligos targeting the 5′ and 3′ ends of PPP1R15A mRNA (Table 1) and incubated them at 70°C for 5 minutes. Supernatants were incubated with the denatured oligos for 30 minutes at 25°C, and then streptavidin-coupled magnetic beads were added (Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin C1; 65001; Thermo Fisher). RNA and proteins were recovered following Iadevaia et al.’s protocol.27 In a separate experiment (without immunoprecipitation), cells were treated with poly(I:C) (1.5 µg/ml for 4 hours) and a combination of proteasome inhibitor (2 µM Bortezomib; 5043140001; Sigma/Calbiochem) and prolyl endopeptidase inhibitors (10 µM Pramiracetam, SLM-0816; 10 µM Baicalein, 465119; 10 µM Berberine Chloride, B3251; all from Sigma) for 4 hours, and cell lysates were analyzed using the Orbitrap Exploris 480 mass spectrometer. Data were analyzed in a Proteome Discoverer 2.5 and SEQUEST HT. Precursor mass tolerance was set to 10 ppm and fragment mass tolerance set at 0.02 D. Dynamic modifications include methionine oxidation; deamidation of asparagine and glutamine; and phosphorylation on serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues. Dynamic peptide modifications were acetylation, met-loss, and met-loss plus acetylation. Static modifications were carbamidomethylation on cysteines. Percolator false discovery rate filtration of 1% was applied to both the peptide-spectrum match and protein levels. For the Proteome Discoverer consensus workflow, isobaric impurities corrections were turned on, the reporter ion coisolation threshold was set to 50%, and the average signal-to-noise threshold was seven. Peptides were normalized to the total peptide amount in each channel and scaled to the control channels. Differential expression of the protein groups is assessed by ANOVA-calculated P values.

Western Blotting

Proteins from cells and tissues were extracted using RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Pierce) with 0.5 M EGTA, 0.5 M EDTA, DNase I (0.1 U/µl; AM2222; Ambion), Halt protease inhibitors (Pierce), phosStop inhibitor (Roche), and benzonase nuclease (25 U/ml; 70746-4; EMD Millipore). Total protein levels were determined using a modified Lowry assay (Bio-Rad). Equal amounts of total proteins (10–20 μg) were mixed with NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (Thermo Fisher) with 100 mM of DTT, separated by electrophoreses on NuPage 4%–12% Bis-Tris gels, and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Antibodies used include the following: Ppp1r15a/GADD34 (rabbit polyclonal, 1:1000 dilution; 10449-1-AP; Proteintech), p-eIF2α (Ser51; catalog number PIPA537800; Invitrogen), eIF2α (catalog number 9722; Cell Signaling Technology), mIgG2b κ isotype (control antibody for Y-3 antibody Western blot, 1:3000 dilution; 14-4732-82; eBioscience/Thermo Fisher), Alexa Fluor 680 and 790 secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and histone H3 (mouse monoclonal, 1:1000 dilution; catalog number 9715; Cell Signaling Technology). For PPP1R15A protein turnover determination, cells were incubated with 250 µg/ml of cycloheximide for the indicated duration before cell lysis. Quantitation was done using Image Studio.

PCR

RNA was extracted using TRI Reagent and Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep Plus (R2070; Zymo Research). Reverse transcription was done using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (4368814; Thermo Fisher/Applied Biosystems). For SYBR Green quantitative PCR, SensiFAST SYBR Green No-ROXSYBRgreen (BIO-94002; Bioline) was used on ViiA7 Real-Time PCR systems (ABI). We used the ΔΔCt method to analyze the relative changes in gene expression. PCR primers used are listed in Table 1. Conventional PCR was done using 2% agarose gel.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, sectioned (5 μm), and deparaffinized. Low pH antigen retrieval was used. Tissues were stained for Ppp1r15a (10449-1-AP; Proteintech) and imaged using a Keyence BZ-X810 fluorescence microscope. Quantitation was done using the ImageJ plug-in IHC Toolbox.

Single-Cell ATAC Sequencing

We followed the Humphreys laboratory protocol for single-nuclei isolation.28 Each mouse kidney was minced and homogenized using Dounce homogenizer (5× loose, 10× tight; KT885300-0002; Kimble Chase) in 2 ml Nuclei EZ lysis buffer (N-3408; Sigma) supplemented with SUPERase In and cOmplete ULTRA Tablets Mini (05892791001; Roche). Samples were rediluted in the lysis buffer, filtered through a 40-µm cell strainer, and centrifuged for 5 minutes at 500 × g. The pellet was resuspended in 3.5 ml of lysis buffer. After another centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended in Nuclei Buffer provided by 10x Genomics, and nuclei counts were adjusted with additional filtering and centrifugation. The single-cell ATAC analysis was conducted using a 10× Chromium single-cell system (10x Genomics) and a NovaSeq 6000 sequencer (Illumina) at the Indiana University School of Medicine Center for Medical Genomics Core. A final nuclei concentration of ≥3000/µl was applied to target nuclei recovery of 10,000. Tagmentation was performed immediately, followed by GEM generation and barcoding, and then library preparation using the Chromium Single-Cell ATAC Reagent Kits User Guide (CG000168 Rev A; 10x Genomics). The quality of the library was examined by Bioanalyzer and Qubit. The resulting library was sequenced for 50-bp paired-end sequencing on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000. About 50K reads per nuclei were generated and 91% of the sequencing reads reached Q30 (99.9% base call accuracy). Phred quality score (Q score) was used to measure the quality of sequencing. Data processing and visualization were done using the Cell Ranger ATAC pipeline and Loupe Brower.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed for statistical significance and visualization with R software 4.1.0. Error bars show SD. For multiple comparisons, one-way ANOVA followed by pairwise t tests was performed using the Benjamini and Hochberg method to adjust P values. All analyses were two sided, and P<0.05 was considered significant. For RNA-seq and Ribo-seq, data were analyzed using edgeR (edgeR::filterByExpr, exactTest, decideTestsDGE, with false discovery rate–adjusted P value of 0.01).

Study Approval

All animal protocols were approved by the Indiana University Institutional Animal Care Committee and conform to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Results

Effects of Ppp1r15a uORF Modulation In Vivo

Progression and recovery of sepsis-induced kidney injury correlate with changes in global translation as we previously determined using nascent proteomics, Ribo-seq, and polyribosome profiling.5 The early phase of kidney injury is characterized by an increase in overall translation (Figure 1A, Supplemental Figure 1B). Tissue-derived proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines are rapidly produced during this time.5,9,29 The resultant stress responses converge on the phosphorylation of the main translation regulator eIF2α mediated by PKR, leading to translation shutdown at later time points in sepsis (12–18 hours after LPS/endotoxemia and CLP in mice5; Figure 1B, Supplemental Figure 1C). Importantly, bypassing eIF2α phosphorylation with ISRIB30,31 rescues translation and accelerates renal recovery.5 This suggests defective protein synthesis in late-phase sepsis is a driver of sustained tissue damage rather than a by-product. Using our published RNA-seq and Ribo-seq data, here we searched for a molecular target that could be contributing to this sustained global translation shutdown. We identified that translation efficiency of Ppp1r15a was low during endotoxemia (Figure 1C, left panel; translation efficiency=Ribo-seq/RNA-seq coverage ratio over protein coding sequence region [CDS], excluding the preceding uORF region). Ppp1r15a is a key counter-regulatory molecule required for the reversal of eIF2α phosphorylation. Indeed, although endotoxemia increased the Ppp1r15a mRNA levels, the concomitant increase in Ppp1r15a protein was more modest (Figure 1, B–D). Importantly, despite this increase in Ppp1r15a protein, eIF2α remained phosphorylated, indicating an ineffective Ppp1r15a response (Figure 1B, right panel). This insufficient Ppp1r15a expression could explain delayed recovery from translation shutdown. Comparison of Ribo-seq, RNA-seq, and ATAC sequencing data indicates that Ppp1r15a expression is translationally repressed in sepsis, possibly because of the presence of an uORF in front of the canonic CDS (Supplemental Figure 1, B and D).

Figure 1.

Ppp1r15a uORF inhibits translation of Ppp1r15a CDS. (A) Polyribosome profiling of kidney extracts from mice treated with LPS 5 mg/kg intravenously for indicated durations. Ribosomal subunit 40S, 60S, monoribosome (80S), and polyribosomes were separated using sucrose density gradient (10%–50%). The increased polyribosome signal peaked at 4 hours, indicating increased translation. Conversely, at later time points, an increase in monosomal signal and decrease in polyribosomal signal indicate decreased global translation, with a nadir observed at 16 hours after endotoxin challenge. Data are representative of two independent experiments. Polysome/monosome ratios: 8.3, 6.3, 3.8, and 4.7 at 0, 4, 16, and 28 hours, respectively. (B) Time-course analysis of eIF2α serine-51 phosphorylation and Ppp1r15a protein expression by Western blot are shown (mouse kidney extracts). Signal intensity was normalized to 0-hour samples and scaled (hence values range from −2 to +2; right panel). (C) Reanalysis of published mouse kidney Ribo-seq and RNA-seq data.5 Combined Ribo-seq (red, blue, green) and RNA-seq (gray) analysis enables the determination of translation efficiency. P-site offset was computed from ribosome-protected mRNA fragments mapped to transcriptome genome wide. P-site read coverage is shown for Ppp1r15a and Ppp1r15b, and these reads are color coded on the basis of their codon frame use (red, blue, green). The codon-frame periodicity was calculated from the transcription start site (TSS) in the genome coordinate. Thus, codon frame colors can be different before and after an intronic region for a given coding sequence (CDS). Note the low translation efficiency of Ppp1r15a (but not Ppp1r15b), as determined by the low Ribo-seq/RNA-seq ratio over the CDS. Arrow in the left upper panel points to distinct three-nucleotide periodicity throughout the 26 amino acid codons of the third Ppp1r15a uORF (blue). (D) Scatterplot of translation efficiency changes (TE, Ribo-seq/RNA-seq; x axis) and mRNA abundance changes (y axis) from 0-hour baseline to 16 hours after LPS for all protein coding genes with counts value >100. (E) Reporter constructs used in HEK293T cell lines and the Sanger sequencing chromatograms. Full-length mouse Ppp1r15a 5′ UTR was fused to firefly luciferase in frame on the pCDH backbone vector. In the mutant construct, the third uORF (uORF3) was abolished by introducing a single nucleotide mutation in the start codon. (F) Luciferase activity levels are shown for HEK293T cells transfected with Ppp1r15a 5′ UTR wild-type (WT) and mutant plasmids. Chr, chromosome; H3, histone; Ile, isoleucine; Met, methionine; p-eIF2α, phosphorylated eIF2α; PuroR, puromycin resistance; Ser51-p, phosphorylated serine 51; T2A, thosea asigna virus 2A-like self-cleaving peptide.

A wide range of uORFs have been implicated in cis-acting translational control of their main CDS.17,32–34 Conversely, thousands of other uORFs are not characterized or do not have such a regulatory function. For example, Ppp1r15b, the isoform of Ppp1r15a, exhibited a ribosome-occupying uORF similar to Ppp1r15a (Figure 1C, right panel). However, and in contrast to Ppp1r15a, the robust ribosome engagement with the Ppp1r15b uORF did not alter its CDS translation efficiency throughout the course of sepsis. These findings support the notion that uORF-mediated translational control is gene and context dependent.35,36 Therefore, to investigate the functionality of the Ppp1r15a uORF in our models of sepsis, we designed plasmid constructs consisting of intact (wild-type) and mutant 5′ leader sequences of Ppp1r15a inserted between a promoter and the luciferase reporter CDS in frame (Figure 1E). We focused on the third uORF (uORF3, closest to the CDS start site) because of its prominent ribosome occupancy and high sequence conservation across species (Supplemental Figure 1E, mouse uORF3 corresponds to human uORF2). In the mutant construct, the uORF3 start codon was abolished by a single nucleotide mutation while maintaining the overlapping uORF2 stop codon intact. We found elimination of the uORF3 start codon signal substantially increased the amount of downstream CDS translation (Figure 1E), consistent with a model in which the Ppp1r15a uORF serves as a barrier, rather than an enhancer, of its CDS translation, as shown by various groups (Supplemental Figure 1F).37–39

To extend the above plasmid-based study and to elucidate the role of endogenous uORF in the genome, we next generated PPP1R15A uORF mutant human cell lines using CRISPR-Cas9 with homology-directed repair templates (Table 1). These mutant cell lines include start codon mutant (effectively no uORF), short uORF (11 codons as opposed to 26 codons in wild type), long uORF (99 codons), and substitution of difficult-to-translate polyprolines40 (wild-type PPP1R15A uORF harbors polyprolines at the carboxy terminus; Figure 2, A and B, Supplemental Figure 2). As shown in Figure 2C, elimination of genomic uORF (no-uORF) resulted in marked increases in the expression of PPP1R15A protein at baseline. Similarly, truncation of uORF (short uORF) and elimination of polyproline resulted in higher levels of PPP1R15A protein expression compared with wild type. Conversely, long uORF resulted in minimal PPP1R15A protein expression (Figure 2, C–E). These findings are in line with existing literature that both uORF length and polyproline content inversely affect the translation efficiency of downstream CDS.35,36 Despite the high PPP1R15A protein levels, overall translation profiles were comparable between no-uORF and wild type at baseline (Figure 2F, top). This suggests phosphorylated eIF2α, the target of PPP1R15A, is negligible in these cell lines under normal culture conditions, or eIF2α is adequately dephosphorylated by constitutive expression of PPP1R15B.

Figure 2.

Modulation of Ppp1r15a uORF sequence differentially affects Ppp1r15a translation. (A) Schematic of mutant HEK293T cell lines generated with CRISPR/Cas9. No-uORF cell line lacks the uORF methionine (Met, ATG) start codon (instead leucine [CTC, Leu]). Short uORF harbors a truncated 11-mer uORF instead of 26 amino acids in wild type (WT). Long uORF encodes 99-mer uORF due to a single nucleotide deletion and frameshift. Wild-type uORF ends with polyprolines (PP; proline-proline-glycine-stop). Polyproline(+) cell line retains this polyproline sequence followed by a linker and single Strep II Tag (proline-proline-glycine-linker-StrepTag-stop). Polyproline(−) cell line lacks this polyproline sequence, and instead glycine is inserted (glycine-glycine-glycine-linker-StrepTag-stop). (B) Sanger sequencing chromatograms for the indicated cell lines. Chromatograms for the rest of cell lines are shown in Supplemental Figure 2. (C) Western blot and traditional PCR gel electrophoresis for PPP1R15A of indicated cell lines at baseline and after 1 µg/ml poly(I:C) transfection. The shift of PCR products in PP(+) and PP(−) is due to the StrepTag insert. (D) Quantitation of PPP1R15A protein levels, as determined by Western blot under indicated conditions. n=4, independent replicates. (E) Quantitation of PPP1R15A mRNA levels as determined by real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) under indicated conditions. n=3, independent replicates. (F) Polyribosome profiling of wild-type versus no-uORF cell line at baseline (upper panel) and 16 hours after poly(I:C) transfection (lower panel). Polysome/monosome ratios: 1.3 for both cell lines at baseline, and 1.8 and 0.5 at 16 hours for wild-type and no-uORF cell lines, respectively. Ratios indicate higher translation in no-uORF cell line after poly(I:C). Data are representative of two independent experiments. (G) Western blot for PPP1R15A and eIF2α under indicated conditions. Poly(I:C) concentrations used were 0.1, 0.5, and 1.0 µg/ml for 4 hours. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (H) RNA-seq analysis. Representative antiviral genes upregulated after 16 hours of poly(I:C) treatment are shown (all within top 40 differentially expressed genes, as shown in Supplemental Figure 3A). aa, amino acids; ctrl, control; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; H3, histone; p-eIF2α, phosphorylated eIF2α.

Next, we investigated the response of these mutant cell lines to the widely used viral mimicry molecule poly(I:C).41,42 LPS was not used because these mutant cell lines, although ideal for transfection and CRISPR, do not express its receptor TLR4. Moreover, poly(I:C) is a specific and direct activator of double-stranded RNA sensors, including PKR, thus mimicking the antiviral response and translation shutdown observed with LPS in mice (Supplemental Figure 3A). Exposure of cells to poly(I:C) revealed a contrasting effect on PPP1R15A protein expression between wild-type and no-uORF cells. Upon poly(I:C) challenge, wild-type cells showed a mild increase in PPP1R15A protein expression (Figure 2, C and D), similar to the in vivo sepsis model (Figure 1B). In contrast, no-uORF cells had notably high basal expression of PPP1R15A that could not be further increased by poly(I:C) challenge. Similar patterns were observed in cells harboring leaky uORF (short uORF and no polyproline; Figure 2, C–E, Supplemental Figure 3, B and C). This increase in PPP1R15A protein expression correlated with preserved overall protein synthesis upon poly(I:C) challenge (Figure 2F, bottom). Interestingly, a challenge with very high doses of poly(I:C) led to a decrease in PPP1R15A expression (Figure 2G, Supplemental Figure 3D). We reasoned that, in these mutant cells, uninhibited PPP1R15A protein expression at baseline could cause excessive translation of antiviral and inflammatory molecules upon high-dose poly(I:C) challenge. This, in turn, can lead to breakthrough phosphorylation of eIF2α despite high level of PPP1R15A, resulting in translation shutdown, including the translation of PPP1R15A protein itself. Indeed, we found that cells with no-uORF or leaky uORF had a more robust antiviral response to poly(I:C) compared with wild-type cells (Figure 2H). This suggests wild-type uORF plays a beneficial role in limiting inflammation. Additionally, we observed the lack of PPP1R15A protein expression, as seen with long uORF, also resulted in a heightened antiviral response (Figure 2H). This indicates some degree of PPP1R15A expression is required for preventing excessive phosphorylation of eIF2α and resultant integrated stress response, as shown by others.42

In aggregate, these results show that PPP1R15A uORF is a major determinant of PPP1R15A protein translation, and the removal of the uORF increases PPP1R15A protein expression and rescues translation shutdown after poly(I:C) challenge. However, the activity of PPP1R15A also affects the inflammatory surge and the integrated stress response. This underscores the importance of fine-tuning the temporal activity of this PPP1R15A-eIF2α axis along the sepsis timeline.

To determine the significance of Ppp1r15a uORF in vivo, we next generated a knock-in mutant mouse model in which the uORF was abolished by introducing a point mutation in its start codon (Ppp1r15a uORF−/−, Figure 3A). Mutant mice were born at expected Mendelian ratios with no gross abnormalities (Supplemental Figure 4). Elimination of Ppp1r15a uORF resulted in a marked increase in the expression of Ppp1r15a protein at baseline and after LPS challenge in the kidney (Figure 3, B and C). Similar changes in Ppp1r15a protein expression were observed in other organs as well (Figure 3D). However, and in contrast to the cell culture model, several organs showed increases in overall translation at baseline, implicating low-grade phosphorylation of eIF2α is operative in these tissues under normal conditions (kidney and brain, Figure 3E, Supplemental Figure 5A).

Figure 3.

Ppp1r15a uORF-deficient mice show less kidney injury compared with wild type upon endotoxin challenge. Phenotype characterization of Ppp1r15a uORF-deficient mice. (A) Sanger sequencing chromatograms of Ppp1r15a uORF mutant and wild-type (WT) mice. (B) Representative immunohistochemistry staining of Ppp1r15a (brown) is shown for Ppp1r15a uORF−/− and WT mouse kidneys under indicated time points. Ppp1r15a signal is most pronounced in S1 proximal tubule, thick ascending limb (TA), and collecting duct (CD). Quantitation is on the basis of percentage area over threshold staining positive for Ppp1r15a (nine representative areas from n=3 mice per condition). *P<0.05 versus WT. (C) Ribo-seq analysis of Ppp1r15a mouse kidney tissues under indicated conditions. RNA-seq reads are shown in gray and Ribo-seq reads in blue (all three codon frames combined). Data are representative of n=3 mice per condition. (D) Western blot analysis of liver, lung, and brain of Ppp1r15a uORF mutant and WT mice at baseline and 26 hours after 5 mg/kg LPS tail vein injection. Lower panel: Ppp1r15a signal intensity was normalized to 0 hours and scaled for each organ. *P<0.05 versus WT. (E) Polyribosome profiling of kidney extracts from mice treated with LPS intravenously for indicated durations. For clarity, traces are overlayed within (upper four panels) or between (lower five panels) Ppp1r15a uORF−/− and WT mice for select time points. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (F) Heatmap of select antiviral genes in Ppp1r15a uORF mutant and wild-type mouse kidneys under indicated conditions, as determined by RNA-seq. (G) Serum creatinine levels at baseline and 24 hours after 5 mg/kg LPS intravenously for Ppp1r15a uORF−/− and WT male mice. (H) Survival curves after CLP are shown for homozygous (Homo), heterozygous (Hetero) Ppp1r15a uORF mutant, and WT mice (n=7–9 per condition). *P<0.05 versus heterozygous mice. ATA(Ile), isoleucine; ATG(Met), methionine; chr, chromosome; H3, histone.

Time-course analysis of polyribosome profiling showed the increased translation at baseline was sustained in uORF−/− kidneys and remained higher than in wild type at all time points after LPS challenge (Figure 3E). Importantly, this increased translation in uORF−/− animals did not lead to an exaggerated antiviral response (Figure 3F, Supplemental Figure 5, B and C). Finally, uORF−/− animals sustained less kidney injury after LPS compared with wild type (Figure 3F). Both the preserved translation and the lack of a vigorous antiviral response likely explain the improved renal function in the uORF−/− animals. The temporal changes in translation after LPS in other organs were variable, as shown in Supplemental Figure 5, A and D.

Lastly, we examined the effects of increased Ppp1r15a expression in CLP, a severe and lethal model of sepsis. We report the heterozygous animals (uORF+/−) showed improved survival after CLP. In contrast, homozygous animals (uORF−/−) had increased mortality compared with wild type (uORF+/+; Figure 3H). The causes of mortality in CLP are complex and determined by systemic factors and damage in multiple organs besides the kidney. The magnitude and temporal changes in Ppp1r15a levels and their effects on protein synthesis are likely different in various organs and were not examined in this study.

Strategy to Modulate Ppp1r15a uORF In Vivo

The results described above with uORF−/− mice underscore the complexity of the role of translation along the sepsis timeline. Therefore, we developed an in vivo uORF knockdown strategy whereby translation rescue could be temporally controlled. To this end, we designed ASOs to mask the uORF, allow continued ribosome scanning,43,44 and boost the translation efficiency of downstream CDS (Figure 4A). As inspired by a recent study,43 we specifically focused on regions adjacent to the uORF start codon. ASOs were modified with 2′-O-methyl to enhance binding affinity and to confer resistance to nucleases. Using luciferase as a readout in cell culture, we determined that ASO targeting downstream of Ppp1r15a uORF start codon was particularly effective in inducing CDS translation (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Antisense oligonucleotide targeting Ppp1r15a uORF increases Ppp1r15a protein expression and mitigates endotoxin-induced kidney injury. In vivo therapeutic effects of uORF-targeted oligonucleotides in sepsis. (A) ASO-based strategy to increase translation efficiency is shown. (B) Luciferase activity levels are shown for HEK293T cells transfected with wild-type PPP1R15A 5′ UTR luciferase reporter (Figure 1E) and indicated ASOs. Control consists of scramble ASO mix. (C) In vivo time-course experiment demonstrating the upregulation of Ppp1r15a protein levels in the kidneys of ASO2-treated wild-type mice, as determined by Western blot. Mice were injected with 10 mg/kg ASO via tail vein at indicated time points after 5 mg/kg LPS intravenously and tissues were harvested 24 hours after LPS. n=3 per condition. (D) Serum creatinine levels 24 hours after 5 mg/kg LPS intravenously under indicated conditions. ASO2, scramble or saline vehicle were administered one time approximately 8 hours after LPS. n=5–7 per condition. (E) Representative polyribosome profiling of kidney extracts from wild-type mice treated with indicated conditions. Polysome/monosome ratios: 8.4 (control), 4.4 (LPS), 7.4 (LPS plus 20 mg/kg ASO 5 hours after LPS), 5.2 (LPS plus 10 mg/kg ASO 5 hours after LPS), and 4.7 (LPS plus 10 mg/kg ASO 12 hours after LPS). H3, histone.

We next tested the efficacy of ASO-based induction of Ppp1r15a protein in vivo using our mouse model of endotoxemia. The tissue distribution of ASOs is similar to in vivo small interfering RNA.45,46 Indeed, ASOs enrich in the proximal tubules,47–49 where translation shutdown is most prominent in the kidney.5 We found that the antisense therapy, administered after LPS injection, enhanced Ppp1r15a protein expression, improved overall translation, and promoted functional recovery in the kidneys of septic mice (Figure 4, C–E).

Effects of Ppp1r15a uORF Modulation on MHC-I Immunopeptidome

Nearly 50% of our genes harbor at least one uORF, and many of them are believed to be translated into peptides on the basis of their ribosome footprints.23,50 Such peptides could have broad effects beyond modulating scanning ribosome kinetics. However, the actual existence of the vast majority of putative uORF-derived peptides await further experimental evidence, including a Ppp1r15a uORF-derived peptide. Recent work by others revealed that uORF-derived peptides are presented on the MHC-I.20,21 Compared with the whole proteome, the immunopeptidome (MHC-I IP/MS) significantly enriches noncanonic ORF-derived peptides, possibly due to preferential antigen presentation or stabilization of these short peptides in the MHC groove (0.1% in whole proteome versus approximately 2% in immunopeptidome).20 Thus, in our search for Ppp1r15a uORF-derived peptide, we performed immunopeptidomics of the mouse kidney using our endotoxemia model. To enable the detection of unannotated uORF peptides, we built a custom reference database using our kidney Ribo-seq data (see Methods). To enrich C57BL/6 MHC-I haplotype H2-Kb, we used mAbs produced by Y-3 hybridoma (Supplemental Figure 6, A and B). In Figure 5A, we show the landscape of kidney immunopeptidomics for wild-type and Ppp1r15a uORF−/− mice at baseline and after endotoxin challenge. We found the overall difference in the immunopeptidomic profile was more pronounced between the two genotypes than with endotoxin-induced changes, pointing to the uORF sequence playing a significant role in immunologic governance (Figure 5B, Supplemental Figure 6C). Pathways involved in oxidative phosphorylation and defense against bacterial invasion were enriched in all samples across time points (Supplemental Figure 6D). No changes were found in the degree of peptide/MHC complex immunogenicity51 between wild-type and Ppp1r15a uORF−/− kidneys (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Modulation of Ppp1r15a enables accelerated renal recovery in a model of endotoxemia. Ppp1r15a uORF−/− mouse kidney exhibits distinct MHC-I immunopeptidome. (A) Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plots of MHC-I associated peptides detected from wild-type (WT) and Ppp1r15a uORF−/− mouse kidneys. H2-Kb haplotype, nine-mers are shown. Each dot represents a unique peptide. Peptide distance was defined on the basis of amino acid sequence similarity. Overlay of WT and Ppp1r15a uORF−/− NMDS plots are shown in Supplemental Figure 6. (B) Jaccard similarity index analysis performed on H2-Kb nine-mers per sample. (C) Predicted immunogenicity of peptide/MHC-I complex (T-cell recognition score)51 is shown for the indicated conditions (nine-mers from n=3 samples are combined for each condition in the scatterplot; no significant differences). (D) Summary of noncanonic peptides (light blue) supported by both Ribo-seq and MHC-I immunopeptidomics under indicated conditions. Liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry spectrum of Polr1a uORF is shown on the right. (E) Ratios of phosphorylated peptides adjusted for total peptide counts are shown under indicated conditions. dORF, downstream ORF; iORF, internal out-of-frame ORF; uoORF, upstream overlapping ORF.

Although our target uORF peptide was not detected with this immunopeptidomics approach (see also Supplemental Figure 7), various other uORF-derived peptides were identified. Interestingly, a peptide originating from the uORF of Polr1a (RNA polymerase I subunit A, required for ribosomal RNA transcription) was found in wild-type mouse kidneys, but not in Ppp1r15a uORF−/− (Figure 5D). Ribo-seq data corroborate that Polr1a uORF is translated in wild type but not in Ppp1r15a uORF−/− (Supplemental Figure 8). In addition, mass spectrometry spectra indicate this Polr1a uORF peptide is phosphorylated (Figure 5D, right panel). Although various modifications of MHC peptides have been reported, pathophysiologic implications of uORF peptide phosphorylation are largely unknown. It is tempting to speculate that Ppp1r15a uORF−/− (hence increased Ppp1r15a protein) affected global phosphatase activity, leading to alteration of peptide turnover. Indeed, we found global reduction of phosphorylated immunopeptides across the LPS time points in Ppp1r15a uORF−/− mouse kidneys, uncovering the pervasive dephosphorylation property of Ppp1r15a beyond its canonic target eIF2α (Figure 5E).

Discussion

Ppp1r15a is a key regulatory molecule required for programmed recovery from stress-induced translation shutdown.52 Notably, a very recent, large-scale, genome-wide association analyses revealed the PPP1R15A missense variant is one of the most significant loci associated with susceptibility to coronavirus disease 2019,53 underscoring the clinical relevance of this gene in sepsis. In fact, a role for PPP1R15A has been described in a variety of conditions, such as neurodegenerative disorders, and fundamental processes, like autophagy.54 Here, we propose an essential role for the highly conserved Ppp1r15a uORF in the outcomes of sepsis-induced kidney injury. Sepsis is a complex pathologic state where multiple pathways are aberrantly activated.55–60 Although these changes are spatially and temporally diverse, one major driver that underlies this dynamic state is the activation of antiviral responses. These responses, in turn, lead to the phosphorylation of eIF2α, causing translation shutdown and persistent tissue injury. This converging point offers an attractive route to develop targeted therapy. However, blind manipulation of the core initiation factor eIF2α could lead to unintended consequences, such as uncontrolled translation and complete blockade of the integrated stress response. Therefore, we reasoned it is safer to modulate eIF2α phosphorylation status through Ppp1r15a. One way to alter protein expression of Ppp1r15a is by targeting its uORF. Importantly, this approach enables the stimulation of Ppp1r15a protein translation, which is otherwise difficult to achieve by targeting the protein itself or mRNA expression. Indeed, our studies indicate the Ppp1r15a uORF is directly relevant to the underpinnings of translation shutdown and is a druggable target using the antisense approach (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Modulation of Ppp1r15a enables accelerated renal recovery in a murine model of endotoxemia. Scheme depicting overall approaches used and findings of the study. Overexpression of Ppp1r15a protein was achieved by genetic and antisense oligonucleotide approaches targeting Pppr15a uORF. ATG, methionine; p-eIF2α, phosphorylated eIF2α.

Our in vivo studies provide critical insight into the role of Ppp1r15a uORF in sepsis. Although the general role of Ppp1r15a uORF as a translational repressor of its CDS has been well characterized with plasmid reporters,37–39 the magnitude and consequences of endogenous Ppp1r15a uORF modulation remained unclear until now. Our genetic mouse and cell models permitted the determination of the in vivo significance of the Ppp1r15a uORF. In aggregate, our findings support the role of uORF-based translation rescue in nonlethal, moderate septic kidney injury. In contrast, the complete absence of uORF was deleterious in a severe form of sepsis (CLP), pointing to the existence of nonlinear relationships between disease severity and optimal dosing of Ppp1r15a. Thus, the effect of excessive or insufficient upregulation of Ppp1r15a is context dependent, highlighting the importance of establishing a refined strategy to calibrate this critical node. A grand challenge is then to develop a pragmatic approach to defining the timeline of sepsis and quantitating translation to precisely stratify such uORF-based therapy.

In agreement with existing literature, our study also revealed the importance of uORF attributes, such as length and codon composition, in determining CDS translation in vivo. Whether these effects are mediated solely by altered ribosome scanning kinetics over the Ppp1r15a mRNA in cis, or through a much deeper peptide-level network, remains undetermined. Small uORF-derived peptides are generally unstable unless dedicated protective mechanisms exist. Indeed, very little is known about localization, modification, and lifetimes of uORF-derived peptides. Regardless, our study revealed strikingly broad biologic consequences mediated by modulation of uORF in vivo, including under basal conditions in which Ppp1r15a protein expression is hardly detectable. In particular, the wide-ranging effects on protein phosphorylation and the immunopeptidome suggest Ppp1r15a uORF modulation has powerful influences even outside of the eIF2α axis. Finally, because thousands of genes harbor ribosome-engaged uORFs that are believed to be functional,23,61–67 our general approach to controlling protein levels through uORF manipulation is highly promising.

Limitations of the Study

This is the first report on the role of Ppp1r15a uORF in sepsis and septic kidney injury using a newly generated knock-in mouse model, mutant cell lines, and an in vivo oligonucleotide approach. This work reveals the intricacy of uORF-dependent Ppp1r15a translation and extends our understanding of Ppp1r15a biology at large.7,37,38,42,52,68–71 Future work will involve broader disease models, tissues, and cell types, with the goal of fully harnessing the power of uORF modulation. Given the significant changes observed in the MHC-I immunopeptidome, it will be interesting to examine the effects of Ppp1r15a uORF on adaptive immunity using long-term disease models. Addressing these limitations is important for proposing uORF-based therapies to control translation and disease trajectory.

We recognize our mouse models of sepsis do not fully recapitulate the complex human sepsis pathophysiology. For example, although gene expression signatures of patients with sepsis and human endotoxemia (LPS injection to healthy subjects) largely correlate,59,72 such correlation is limited between human and mouse models of endotoxemia.73–77 Nevertheless, the eIF2α axis is highly conserved across species, and we believe interrogation of simple and reproducible murine models is one step toward elucidating the dynamic and complex feedback mechanisms operative along the eIF2α axis in sepsis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ronald C. Wek for his careful reading and insightful comments. We also thank Dr. Amber Mosley, Dr. Aruna Wijeratne, Dr. Guihong Qi, and Dr. Whitney Smith-Kinnamari at the Indiana University School of Medicine Proteomics Core; Dr. Yunlong Liu, Dr. Hongyu Gao, Dr. Patrick McGuire, and Dr. Mandy Bittner at the Center for Medical Genomics; Dr. Constance Temm and Dr. Connor Gulbronson for assistance with tissue staining and imaging; and former laboratory member Thomas W. McCarthy.

Footnotes

A.K. and S.P.S.Y. contributed equally to this work.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “Targeting a Single Codon to Rescue Septic Acute Kidney Injury,” on pages 179–181.

Disclosures

E.H. Doud reports receiving honoraria from PEAKS Bioinformatics Solutions. A. Halim reports having ownership interest in OVIBIO Corporation. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Measurement of serum creatinine concentration was performed by Dr. John Moore and Dr. Yang Yan, et al. at the University of Alabama at Birmingham/University of California San Diego O’Brien Center Core for Acute Kidney Injury Research, supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant P30DK079337, using isotope dilution LC-MS. This work was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant R01-AI148282, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant K08-DK113223, US Department of Veterans Affairs Merit award BX002901, the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (to T. Hato), and NIH grant R01-DK107623 to P.C. Dagher.

Author Contributions

K. Banno, E.H. Doud, A.B. Waffo, X. Xuei, and L. Zeng were responsible for resources; P.C. Dagher and T. Hato provided supervision, reviewed and edited the manuscript, and were responsible for funding acquisition and project administration; P.C. Dagher, T. Hato, A. Kidwell, and B. Maier conceptualized the study; E.H. Doud, A. Halim, T. Hato, D. Janosevic, A. Kidwell, B. Maier, K. Ni, F. Syed, S.P.S. Yadav, and A. Zollman were responsible for methodology; A. Halim, T. Hato, A. Kidwell, B. Maier, K. Ni, S.P.S. Yadav, and A. Zollman were responsible for investigation; T. Hato wrote the original draft and was responsible for validation; T. Hato, A. Kidwell, F. Syed, S.P.S. Yadav, and A. Zollman were responsible for data curation; and T. Hato and J. Myslinski were responsible for formal analysis and visualization.

Data Sharing Statement

RNA-seq, Ribo-seq, and single-nucleus ATAC sequencing data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession nos. GSE191262 and GSE210938). Proteomics data are deposited in ProteomeXchange (accession no. PXD030889). Scripts are available through GitHub: https://github.com/hato-lab.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://links.lww.com/JSN/D723.

Supplemental Figure 1. Single-cell RNA-sequencing and ATAC-sequencing data analyses.

Supplemental Figure 2. Sanger sequencing chromatograms for cell lines used in this study.

Supplemental Figure 3. Cell line characterization including RNA-sequencing and PPP1R15A protein turnover.

Supplemental Figure 4. Histology of Ppp1r15a uORF mutant mouse tissues.

Supplemental Figure 5. Polyribosomal profiling and ribo-seq analyses of Ppp1r15a uORF mutant mice.

Supplemental Figure 6. Additional MHC peptidomics analyses.

Supplemental Figure 7. Methods used for Ppp1r15a uORF-derived peptide search.

Supplemental Figure 8. Ribo-seq analysis of Polr1a.

Supplemental Figure 9. Ppp1r15a antibody validation and full uncut gels under indicated conditions.

References

- 1.Deutschman CS, Tracey KJ: Sepsis: Current dogma and new perspectives. Immunity 40: 463–475, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Poll T, Shankar-Hari M, Wiersinga WJ: The immunology of sepsis. Immunity 54: 2450–2464, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casanova JL, Abel L: Mechanisms of viral inflammation and disease in humans. Science 374: 1080–1086, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hato T, Dagher PC: How the innate immune system senses trouble and causes trouble. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1459–1469, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hato T, Maier B, Syed F, Myslinski J, Zollman A, Plotkin Z, et al. : Bacterial sepsis triggers an antiviral response that causes translation shutdown. J Clin Invest 129: 296–309, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pakos-Zebrucka K, Koryga I, Mnich K, Ljujic M, Samali A, Gorman AM: The integrated stress response. EMBO Rep 17: 1374–1395, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harding HP, Zhang Y, Scheuner D, Chen JJ, Kaufman RJ, Ron D: Ppp1r15 gene knockout reveals an essential role for translation initiation factor 2 alpha (eIF2alpha) dephosphorylation in mammalian development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 1832–1837, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costa-Mattioli M, Walter P: The integrated stress response: From mechanism to disease. Science 368: eaat5314, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janosevic D, Myslinski J, McCarthy TW, Zollman A, Syed F, Xuei X, et al. : The orchestrated cellular and molecular responses of the kidney to endotoxin define a precise sepsis timeline. eLife 10: 62270, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smyth R, Sun J: Protein kinase R in bacterial infections: Friend or foe? Front Immunol 12: 702142, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balachandran S, Roberts PC, Brown LE, Truong H, Pattnaik AK, Archer DR, et al. : Essential role for the dsRNA-dependent protein kinase PKR in innate immunity to viral infection. Immunity 13: 129–141, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rojas M, Vasconcelos G, Dever TE: An eIF2α-binding motif in protein phosphatase 1 subunit GADD34 and its viral orthologs is required to promote dephosphorylation of eIF2α. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112: 3466–3475, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choy MS, Yusoff P, Lee IC, Newton JC, Goh CW, Page R, et al. : Structural and functional analysis of the GADD34:PP1 eIF2α phosphatase. Cell Rep 11: 1885–1891, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwart D, Paquet D, Teo S, Tessier-Lavigne M: Precise and efficient scarless genome editing in stem cells using CORRECT. Nat Protoc 12: 329–354, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richardson CD, Ray GJ, DeWitt MA, Curie GL, Corn JE: Enhancing homology-directed genome editing by catalytically active and inactive CRISPR-Cas9 using asymmetric donor DNA. Nat Biotechnol 34: 339–344, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerashchenko MV, Gladyshev VN: Ribonuclease selection for ribosome profiling. Nucleic Acids Res 45: 6, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez TF, Chu Q, Donaldson C, Tan D, Shokhirev MN, Saghatelian A: Accurate annotation of human protein-coding small open reading frames. Nat Chem Biol 16: 458–468, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zinshteyn B, Wangen JR, Hua B, Green R: Nuclease-mediated depletion biases in ribosome footprint profiling libraries. RNA 26: 1481–1488, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erhard F, Halenius A, Zimmermann C, L’Hernault A, Kowalewski DJ, Weekes MP, et al. : Improved ribo-seq enables identification of cryptic translation events. Nat Methods 15: 363–366, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ouspenskaia T, Law T, Clauser KR, Klaeger S, Sarkizova S, Aguet F, et al. : Unannotated proteins expand the MHC-I-restricted immunopeptidome in cancer. Nat Biotechnol 40: 209–217, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruiz Cuevas MV, Hardy MP, Hollý J, Bonneil É, Durette C, Courcelles M, et al. : Most non-canonical proteins uniquely populate the proteome or immunopeptidome. Cell Rep 34: 108815, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laumont CM, Daouda T, Laverdure JP, Bonneil É, Caron-Lizotte O, Hardy MP, et al. : Global proteogenomic analysis of human MHC class I-associated peptides derived from non-canonical reading frames. Nat Commun 7: 10238, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mudge JM, Ruiz-Orera J, Prensner JR, Brunet MA, Calvet F, Jungreis I, et al. : Standardized annotation of translated open reading frames. Nat Biotechnol 40: 994–999, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kong AT, Leprevost FV, Avtonomov DM, Mellacheruvu D, Nesvizhskii AI: MSFragger: Ultrafast and comprehensive peptide identification in mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nat Methods 14: 513–520, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reynisson B, Alvarez B, Paul S, Peters B, Nielsen M: NetMHCpan-4.1 and NetMHCIIpan-4.0: Improved predictions of MHC antigen presentation by concurrent motif deconvolution and integration of MS MHC eluted ligand data. Nucleic Acids Res 48: 449–454, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarkizova S, Klaeger S, Le PM, Li LW, Oliveira G, Keshishian H, et al. : A large peptidome dataset improves HLA class I epitope prediction across most of the human population. Nat Biotechnol 38: 199–209, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iadevaia V, Matia-González AM, Gerber AP: An oligonucleotide-based tandem RNA isolation procedure to recover eukaryotic mRNA-protein complexes. J Vis Exp (138): 58223, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirita Y, Wu H, Uchimura K, Wilson PC, Humphreys BD: Cell profiling of mouse acute kidney injury reveals conserved cellular responses to injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117: 15874–15883, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]