Keywords: lupus nephritis, DDX58, pathogenic variant R109C, pathogenesis, targeted therapy

Abstract

Significance Statement

Lupus nephritis (LN) is the major cause of death among systemic lupus erythematosus patients, with heterogeneous phenotypes and different responses to therapy. Identifying genetic causes and finding potential therapeutic targets of LN is a major unmet clinical need. We identified a novel DDX58 pathogenic variant, R109C, that leads to RIG-I hyperactivation and type I IFN signaling upregulation by disrupting RIG-I autoinhibition, causing LN, which may respond to a JAK inhibitor. Genetic testing of families with multiple cases of LN that identifies this variant may lead to targeted therapy.

Background

Lupus nephritis (LN) is one of the most severe complications of systemic lupus erythematosus, with heterogeneous phenotypes and different responses to therapy. Identifying genetic causes of LN can facilitate more individual treatment strategies.

Methods

We performed whole-exome sequencing in a cohort of Chinese patients with LN and identified variants of a disease-causing gene. Extensive biochemical, immunologic, and functional analyses assessed the effect of the variant on type I IFN signaling. We further investigated the effectiveness of targeted therapy using single-cell RNA sequencing.

Results

We identified a novel DDX58 pathogenic variant, R109C, in five unrelated families with LN. The DDX58 R109C variant is a gain-of-function mutation, elevating type I IFN signaling due to reduced autoinhibition, which leads to RIG-I hyperactivation, increased RIG-I K63 ubiquitination, and MAVS aggregation. Transcriptome analysis revealed an increased IFN signature in patient monocytes. Initiation of JAK inhibitor therapy (baricitinib 2 mg/d) effectively suppressed the IFN signal in one patient.

Conclusions

A novel DDX58 R109C variant that can cause LN connects IFNopathy and LN, suggesting targeted therapy on the basis of pathogenicity.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a heterogeneous autoimmune disease with a complex etiology and diverse clinical manifestations. It can affect the skin, joints, kidneys, and neurologic and hematologic systems. Lupus nephritis (LN) is one of the most severe complications and may result in irreversible organ damage and death. Current diagnosis for LN is primarily on the basis of identification of clinical and pathologic manifestations, and management is largely limited to empirical treatment with immunosuppressants. Identifying genetic causes of LN may tailor diagnosis and lead to targeted therapy for patients. Until now, more than 30 genes have been reported to cause diseases manifesting as SLE or SLE-like phenotype.1 In particular, patients carrying pathogenic variants in C1R, DNASE1L3, IFIH1, COPA, ACP5, or PRKCD genes also presented with LN.2–7

DDX58 (DExD/H-box helicase 58) encodes the cytosolic double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) sensor retinoic-acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I), an important cytosolic pattern recognition receptor involved in sensing RNA virus infection and inducing IFN production.8 During viral infection, RIG-I binds to viral RNA and activates mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein (MAVS). Once activated, MAVS aggregates at mitochondria and further recruits the downstream TANK-binding kinase (TBK1) and IKKε. In turn, downstream phosphorylation of IFN regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and IFN regulatory factor 7 (IRF7) leads to transcriptional activation of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) and the release of proinflammatory cytokines.8

Heterozygous pathogenic variants, including C268F, E373A, E510V, and Q517H in DDX58, have previously been identified in five families with Singleton–Merten syndrome (SMS), an autosomal dominant inherited multisystemic disorder associated with IFN pathway activation and characterized by glaucoma, aortic calcification, psoriasis, and dental and skeletal abnormalities.9–11 Nearly all of the reported patients (17 of 18; 94%) present with glaucoma. Besides, aortic involvement is common (9 of 14; 64%), and a psoriasiform rash is observed in around two thirds (11 of 18; 61%) of patients (Supplemental Table 1). However, there is no report on DDX58 variants associated with LN. In this study, we identified a novel gain-of-function pathogenic variant in DDX58 that caused LN and illuminated a new mechanism of RIG-I activation leading to IFN pathway activation. This is also the first report implicating the patient with DDX58 variant may respond to JAK inhibitor treatment and highlighting the importance of identifying the underlying pathogenicity of disease to provide effective treatment of LN.

Methods

Patients

All patients who met the diagnostic criteria for SLE with biopsy-proven LN were evaluated from the Nanjing Glomerulonephritis Registry at Jinling Hospital. All patients enrolled in the study were evaluated under a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Boards. All of the patients and family members provided written informed consent, including consent to publish.

Whole-Exome Sequencing and Sanger Sequencing

One microgram of peripheral blood DNA was used for whole-exome sequencing (WES; BGI, Shenzhen, PR China). Candidate variants were filtered by removing those with high frequency, which presented in the gnomAD, Kaviar, and dbSNP databases and an in-house database. Variants were further filtered by dominant inheritance as previously described.12

Sanger sequencing was used to confirm variants identified by WES as previously described.12

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

Single-cell capture (8000–10,000 cells) and cDNA preparation were performed on a Chromium machine (10× Genomics, Pleasanton, CA). The barcoded cDNA was then amplified by PCR. The library construction, sequencing, and data analysis were performed as previously described.13

Cell Preparation, Culture, and Treatment

PBMCs were separated by lymphocyte separation medium (50494; MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA) from peripheral blood. The human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cell line was from the American Type Culture Collection. PBMCs and HEK293T cells were grown in RPMI 1640 (C11875500BT; Gibco, Grand Island, NY) or DMEM (C11995500BT; Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (NFBS-2500A; Noverse).

Poly(I:C) (P1530; Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; 5 μg/ml) was used to stimulate HEK293T cells for the indicated amount of time.

Transfection

Transient transfections of plasmids in HEK293T cells were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (11668019; Invitrogen, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were analyzed 18–24 hours after transfection.

Western Blotting and Immunoprecipitation

HEK293T cells were harvested and lysed in 1% Triton X-100 lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 2 mM EDTA). All buffers used throughout processing contained protease and phosphatase inhibitor mixture (78442; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Proteins were denatured and separated on SDS-PAGE and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. After blocking with 5% (wt/vol) BSA, the membrane was stained with the corresponding primary and secondary antibodies. Specific bands were analyzed using an Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

For immunoprecipitation, cell lysates were mixed with anti-Myc magnetic beads (B26302; Bimake, Houston, TX) at 4°C overnight. Then, immunocomplexes were washed five times using lysis buffer and subjected to Western blotting.

Native PAGE

TSDG buffer-lysed protein (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 10 mM NaCl, 1.1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM ATP, and 10% glycerol) was separated on native PAGE (3%–12%; BN1001BOX; Invitrogen) and immunoblotted as indicated.

Semi-Denaturing Detergent Agarose Gel Electrophoresis

Cellular lysate in hypotonic buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EGTA, and 1.5 mM MgCl2) was obtained and centrifuged at 1000× g for 5 minutes. The supernatant was isolated and further centrifuged at 10,000× g for 10 minutes. The supernatant and pellet were then separated. Crude mitochondria in the pellet isolated from HEK293T cells were resuspended in 1× sample buffer (0.5× TBE, 10% glycerol, 2% SDS, and 0.0025% bromophenol blue) and loaded onto a vertical 1.5% agarose gel. After electrophoresis in the running buffer (1× TBE and 0.1%×SDS) for 30 minutes with a constant voltage of 100 V at 4°C, Western blotting was performed.

Antibodies and Plasmids

The commercial antibodies were as follows: (1) Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA): p65 (8242S), p-p65 (3033S), TBK1 (3504S), p-TBK1 (5483S), STAT1 (14994), p-STAT1 (9167S), STAT2 (72604), p-STAT2 (4441S), IRF3 (11904), p-IRF3 (37829), IFIT3 (87781S), GAPDH (5174), and HA (3724); and (2) Proteintech (Chicago, IL): β-actin (66009-1-Ig), Flag (20543-1-AP), and Myc (60003-2-Ig).

Tag-tagged RIG-I was made by cloning the corresponding human cDNA into different carrier vectors. Mutant plasmids were generated by site-directed mutagenesis. The plasmids for MAVS and K63-ub were kindly provided by Dr. Pinglong Xu. All plasmids were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

RNA Extraction and Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells with RNeasy Mini kit (74104; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). cDNA was reverse transcribed (R333; Vazyme, Nanjing, PR China). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed with 2× Universal SYBR Green Fast qPCR Mix (RK21203; ABclonal, Wuhan, PR China). The reactions were run on a LightCycler 480 II (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Relative mRNA expression levels were normalized to ACTB and analyzed by the 2–ΔΔCt method. The following primers were used in human cells: ACTB-F: CGAGGCCCAGAGCAAGAGAG; ACTB-R: CGGTTGGCCTTAGGGTTCAG; IFIT1-F: GCCTTGCTGAAGTGTGGAGGAA; IFIT1-R: ATCCAGGCGATAGGCAGAGATC; IFI44L-F: TGCACTGAGGCAGATGCTGCG; IFI44L-R: TCATTGCGGCACACCAGTACAG; ISG15-F: CTCTGAGCATCCTGGTGAGGAA; ISG15-R: AAGGTCAGCCAGAACAGGTCGT; RSAD2-F: CCAGTGCAACTACAAATGCGGC; RSAD2-R: CGGTCTTGAAGAAATGGCTCTCC; IFI27-F: CGTCCTCCATAGCAGCCAAGAT; IFI27-R: ACCCAATGGAGCCCAGGATGAA.

RNA Sequencing

One microgram of RNA was used for library preparation. The libraries were generated using NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and sequenced on an Illumina Novaseq (San Diego, CA). A set of 150-bp paired-end reads was generated and mapped to the human reference genome (GRCh38) using STAR v2.7.10. featureCounts was used to count the reads numbers mapped to each gene. Differential expression analysis was performed using the DESeq2 package for R.

Calculation of IFN Score

We selected 28 IFN response genes as previously described.14 Z scores of each 28 genes were calculated with DESeq2 normalized counts from RNA sequencing using the mean and standard deviation of controls. Then, the IFN score was calculated by summing all 28 z scores for each sample. The 28 genes were as follows: CXCL10, DDX60, EPSTI1, GBP1, HERC5, HERC6, IFI27, IFI44, IFI44L, IFI6, IFIT1, IFIT2, IFIT3, IFIT5, ISG15, LAMP3, LY6E, MX1, OAS1, OAS2, OAS3, OASL, RSAD2, RTP4, SIGLEC1, SOCS1, SPATS2L, and USP18.

Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay

HEK293T cells were transfected with indicated Myc-tagged RIG-I or mutant plasmids with IFN-stimulated response element (ISRE), IFN-β, NF-κB, or luciferase construct for 48 hours using Lipofectamine 2000, and luciferase reporter gene assays were performed using a Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (E1910; Promega, Madison, WI) on the basis of the protocol provided by the manufacturer.

Cytometric Bead Array Assay

The concentrations of cytokines in serum were measured by cytometric bead array (CBA; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). All data were analyzed by FCAPArray v3 software (BD Biosciences).

Statistical Analyses

Data are expressed as mean±SD, and statistical evaluation was performed using a two-tailed t test with GraphPad Prism v8.0.2 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Identification of a Novel DDX58 Mutation in Patients with LN

The proband (P1) of the first family (Figure 1A) was a 37-year-old woman who initially had a fever accompanied by respiratory infections at the age of 12 years. She then gradually developed acute nephritis syndrome with proteinuria, hematuria, hypoalbuminemia, and elevated serum creatinine. She had a history of spontaneous abortions twice and lacunar cerebral infarction once. Renal biopsy revealed class IV+V LN (Figure 1B). Laboratory testing showed hemolytic anemia, positive ANA, anti-dsDNA and anticardiolipin antibodies, and decreased C3. She was subsequently diagnosed with SLE and LN according to the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria. Additionally, her family history was positive for a paternal grandmother (P2) with SLE and a father (P3) with psoriasis (Figure 1C). Besides, anticardiolipin antibody was detected in her twin sister (P4).

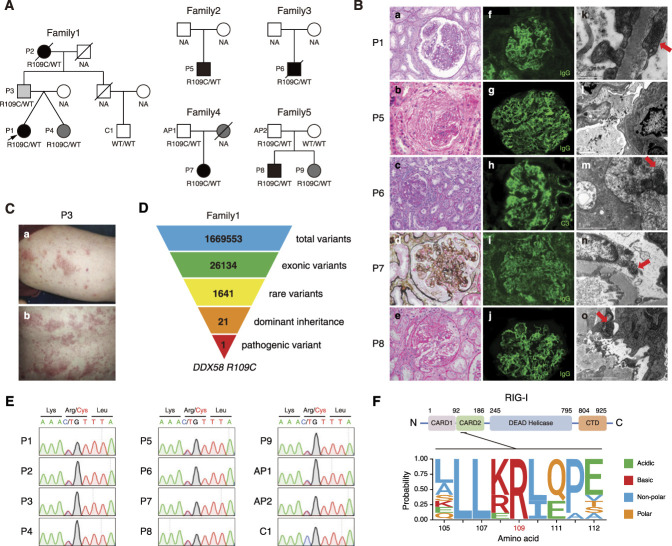

Figure 1.

Identification of a heterozygous DDX58 R109C variant in patients with LN. (A) Pedigrees of the five unrelated families carrying the DDX58 variant. The proband is indicated by an arrow. Black indicates patients with SLE or LN, dark gray indicates patients with suspected SLE, and light gray indicates patients with psoriasis. (B) Renal histopathologic lesions of patients P1, P5, P6, P7, and P8. Light microscopy: (a) Diffuse mesangial and endocapillary proliferation in the glomerulus (PAS, ×400). (b) A fibrocellular crescent compressing the tuft of glomerulus (HE, ×400). (c) The prominent mesangial hypercellularity and segmental endocapillary proliferation in the glomerulus. It also demonstrates acute tubular injury and patchy interstitial inflammation (PAS, ×200). (d) The enlarged glomerulus, which shows a membranoproliferative pattern of injury, with mesangial hypercellularity and glomerular basement membrane duplication (PASM-Masson, ×400). (e) The segmental endocapillary proliferation and a cellular crescent formation in the glomerulus (HE, ×400). Immunofluorescence: (f, g, i, and j) The granular IgG deposits in the mesangial area and along the capillary wall (IF, ×400). (h) The granular C3 deposits in the mesangium and along the glomerular basement membrane (IF, ×400). Electromicroscopy: (k, m, n, and o) Tubuloreticular inclusions in the glomerular endothelial cells (red arrows). (l) Abundant electron-dense deposits in the subendothelial area with wrinkling of the glomerular basement membrane. (C) Psoriasiform skin rash on (a) the arm and (b) the back of P3. (D) Schematic representation of the WES data-filtering approach used to identify dominant inherited pathogenic variant in DDX58 in family 1. (E) Confirmation of the DDX58 R109C variant for patients and family members by Sanger sequencing. (F) Schematic illustration of the structure of human RIG-I protein, and evolutionary conservation of the site R109 in DDX58 across various species. AP, asymptomatic patient; CTD, Carboxy-terminal domain; HE, hematoxylin and eosin; IF, immunofluorescence; NA, not available; PAS, periodic acid–Schiff; PASM, periodic Schiff–methenamine silver.

WES of the first family identified a rare, heterozygous variant, c.325C > T/p.Arg109Cys (R109C) in the DDX58 gene in patients P1–P4, which was consistent with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern (Figure 1D). This variant was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Figure 1E).

We further performed WES in 1376 Chinese LN patients and identified five additional patients (P5–P9) carrying the same DDX58 R109C variant (Figure 1, A and E). The most common clinical features in these patients were renal and hematologic involvement, positive autoantibodies, and decreased complement levels. Renal biopsy demonstrated class III LN in two patients, class IV in two patients, and class IV+V in one patient. The detailed clinical characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1 and Supplemental Appendix 1. The renal histopathologic lesions of patients are presented in Figure 1B and Table 2.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with the DDX58 R109C variant

| No. | Sex | Age at Onset (yr) |

Disease Course (yr) |

Primary Diagnosis |

Kidney Presentation |

Extrarenal Presentations |

Renal Biopsy | Positive Immunologic Features |

SMS-Related Characteristics |

Treatment | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Woman | 12 | 25 | SLE, LN, anticardiolipin antibody syndrome | Acute nephritis syndrome | Hemolytic anemia, abortion, stroke | LN-IV+V | ANA, ds-DNA, anticardiolipin, anti-Sm, SS-A, nRNP-Sm, C3↓ | No | Glucocorticoids, CTX, AZA, MMF, hydroxychloroquine | Partial remission, normal renal function |

| P5 | Man | 51 | 1.42 | SLE, LN | RPGN | Anemia, pleural effusion | LN-IV | ANA, nRNP-Sm, RF, c-ANCA, PR3-ANCA, C3 and C4↓ | No | Glucocorticoids, MMF, RRT | Loss of follow-up |

| P6 | Man | 15 | 6.42 | Psoriasis, LN | Malignant hypertension, nephrotic range proteinuria, hematuria | Psoriatic skin rash, anemia, epileptic seizure | LN-III | Anticardiolipin | Psoriasis | ACEI/ARB | Died, ESKD |

| P7 | Woman | 28 | 13.17 | SLE, LN | Nephrotic syndrome | Malar rash, oral ulcers, arthritis, pancytopenia, pleural effusion | LN-IV | ANA, ds-DNA, nRNP-Sm, C3↓ | No | Glucocorticoids, CTX, MMF, tacrolimus | Partial remission, CKD stage 3 |

| P8 | Man | 45 | 14.33 | SLE, LN | Proteinuria, hematuria, AKI | Rash, oral ulcers, arthritis, thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia | LN-III | ANA, ds-DNA, anticardiolipin, C3 and C4↓ | No | Glucocorticoids, MMF | Complete remission |

ACEI/ARB, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker; AZA, azathioprine; RPGN, rapidly progressive GN.

Table 2.

Renal biopsies of patients with the DDX58 R109C variant

| Imaging Method | P1 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light microscopy | |||||

| No. glomeruli | 23 | 34 | 12 | 30 | 22 |

| No. cellular/ fibrocellular crescents |

11 | 30 | 2 | 13 | 5 |

| Pattern of GN | DPGN | MPGN | FPGN | MPGN | FPGN |

| Acute tubular injury | + | + | + | + | + |

| Tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis | — | — | Severe | Moderate | — |

| Interstitial inflammation | Moderate | Severe | Severe | Moderate | Mild |

| Collapsing glomerulopathy | — | — | — | — | — |

| Thrombotic microangiopathy | — | — | — | — | — |

| Immunofluorescence | |||||

| IgG | 2+MES/CW | 2+MES/CW | — | 2+MES/CW/BC/TBM/BV | 2+MES/CW |

| IgA | 1+MES/CW | 1+MES/CW | 2+MES/CW | 1+MES/CW | 1+MES/CW |

| IgM | 1+MES/CW | 2+MES/CW | 1+MES/CW | 1+MES/CW | 1+MES/CW |

| C3 | 2+MES/CW/TBM | 2+MES/CW/TBM | 2+MES/CW/TBM/BC | 3+MES/CW/TBM/BV | 2+MES/CW/BV |

| C1q | 2+MES/CW | 2+MES/CW | — | trace MES/CW/TBM/BV | 1+MES/CW/BV |

| Electromicroscopy | |||||

| Electron-dense deposits | Mesangial, subendothelial, subepithelial | Mesangial, subendothelial | Mesangial, subendothelial, subepithelial | Mesangial, subendothelial, subepithelial | Mesangial, subendothelial, subepithelial |

| Podocyte foot process effacement | Diffuse | Diffuse | Diffuse | Diffuse | Focal |

| Tubuloreticular inclusions | + | — | + | + | + |

| Renal biopsy diagnosis | LN-IV+V | LN-IV | LN-III | LN-IV | LN-III |

| AI | 14 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 6 |

| CI | 2 | 2 | 9 | 4 | 2 |

AI, activity index; BC, Bowman’s capsule; BV, blood vessels; CI, chronicity index; CW, glomerular capillary wall; DPGN, diffuse proliferative (mesangial and endocapillary) GN; FPGN, focal proliferative GN; MES, mesangial; MPGN, membranoproliferative GN; TBM, tubular basement membrane.

The site R109 in DDX58 is highly conserved across species (Figure 1F). The R109C variant was very rare in the ChinaMap database (0.000047) and absent in the gnomAD database. It was predicted to be deleterious by multiple predictive models, with a combined annotation-dependent depletion score of 33 and a genomic evolutionary rate profiling score of 3.34, and it met American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics criteria for being likely pathogenic.

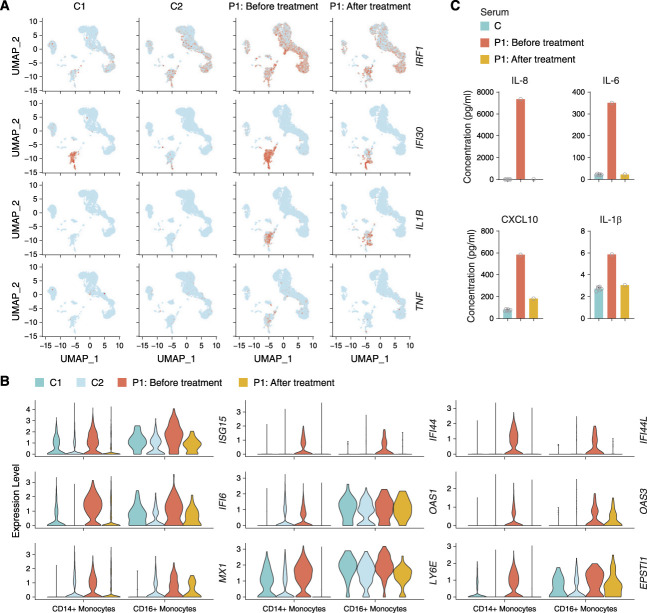

Detection of Inflammatory Signatures in Patients

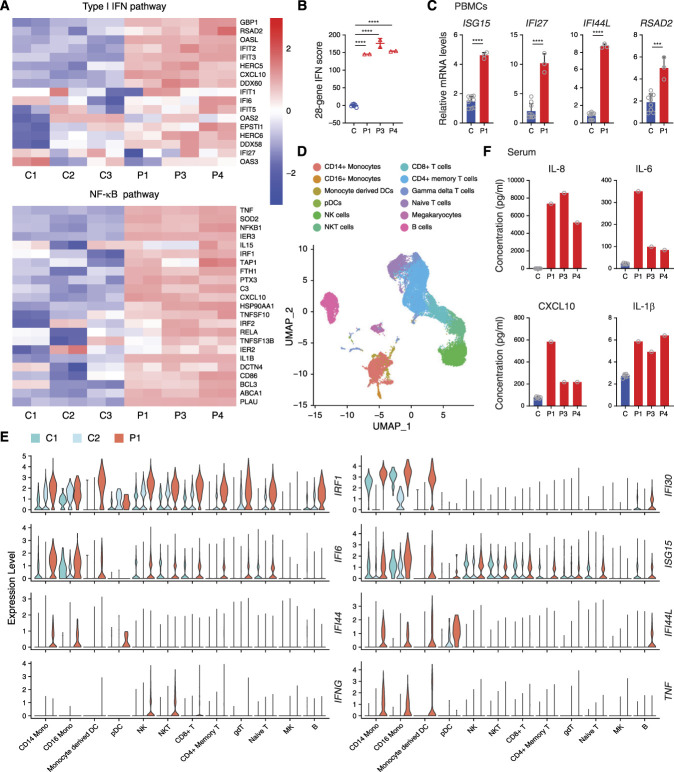

To understand the effect of this DDX58 variant in vivo better, we performed RNA sequencing in patients’ PBMCs. Divergent expression patterns implicated the striking activation of type I IFN and NF-κB pathways in patients compared with healthy controls (Figure 2A, Supplemental Figure 1A). Elevated IFN signaling was also detected using a 28-gene IFN score, a biomarker often used to diagnose and assess the IFNopathies (Figure 2B, Supplemental Figure 1B). qPCR assay confirmed the upregulated expression of ISGs in patients’ PBMCs (Figure 2C, Supplemental Figure 1C). To study the transcriptional changes related to the DDX58 R109C variant further, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) in P1’s PBMCs (Figure 2D). We observed strong signals in the type I IFN pathway in the patient’s PBMCs, especially in CD14+ and CD16+ monocytes (Figure 2E). Furthermore, we determined the serum cytokine profiles of patients using CBA analysis and found a significantly higher concentration of IL-8, IL-6, CXCL10, and IL-1β compared with healthy controls (Figure 2F). Taken together, these results demonstrated that a strong inflammatory response, especially activation of the type I IFN pathway, was detected in patients with the DDX58 R109C variant.

Figure 2.

Hyperactivation of type I IFN and NF-κB signaling in patients with the DDX58 R109C variant. (A) RNA sequencing analysis of type I IFN and NF-κB pathways in P1’s, P3’s, and P4’s PBMCs compared with three unaffected controls (C1–C3). Analysis of each sample was performed in duplicate. (B) Quantification of 28-gene IFN score of RNA sequencing data from (A). Data are presented as the mean±SD; ****P<0.0001, t test. (C) qPCR analysis of the expression of the IFN-stimulated genes in PBMCs from P1 compared with three unaffected controls. Data are presented as the mean±SD; n=3 independent experiments; ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001, t test. (D) Marker-based annotation on UMAP plot of single-cell RNA sequencing data from two unaffected controls (C1 and C2) and patient P1. (E) Visualization of upregulated IFN-stimulated and inflammatory genes among all 12 clusters of P1 compared with two unaffected controls (C1 and C2) in violin plots. (F) CBA analysis of serum proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β, and CXCL10) levels in patients (P1, P3, and P4), compared with six unaffected controls. DCs, dendritic cells; gdT, gamma deta T cells; MK, megakaryocytes; Mono, monocytes; NK, natural killer cells; pDCs, plasmacytoid dendritic cells; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

R109C Mutation Constitutively Activates IFN Signaling

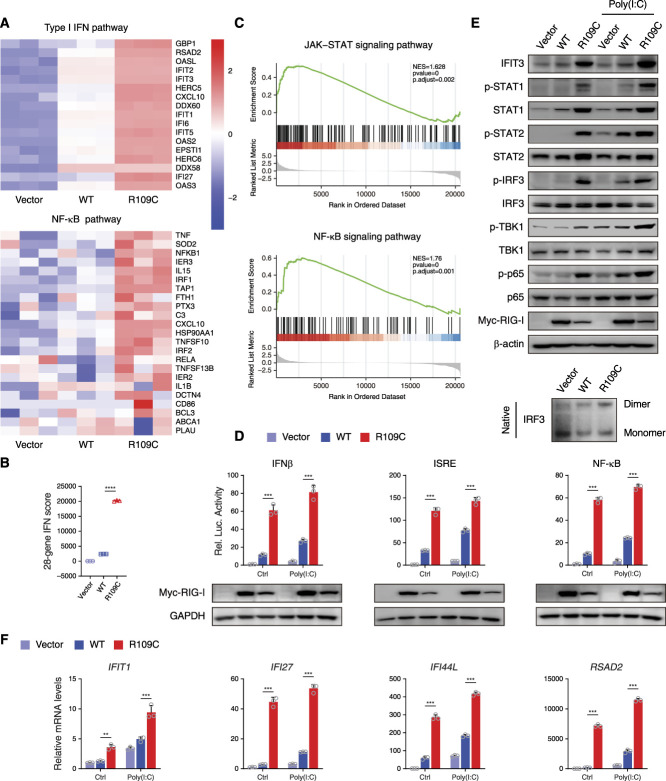

To further investigate the potential effect of the DDX58 R109C variant on type I IFN signaling, we transfected constructs of wild-type (WT) or R109C mutant RIG-I into HEK293T cells. Consistent with the results of PBMCs, RIG-I-R109C–overexpressing cells showed higher activation in type I IFN and NF-κB signaling pathways than RIG-I-WT–transfected cells detected by RNA sequencing (Figure 3A). The 28-gene IFN score analysis confirmed the activation of type I IFN signalig (Figure 3B), and the gene set enrichment analysis related the activation of JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling to the R109C variant (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

R109C mutation constitutively activates the IFN pathway in HEK293T cells. (A) RNA sequencing analysis of type I IFN and NF-κB pathways in HEK293T cells overexpressing with or without RIG-I-WT or R109C for 24 hours. Analysis of each sample was performed in triplicate. (B) Quantification of 28-gene IFN score of RNA sequencing data from (A). Data are presented as the mean±SD; ****P<0.0001, t test. (C) The gene set enrichment analysis plot of differential expression gene sets of RNA sequencing data from (A) enriched on JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways in RIG-I-WT and R109C overexpressing cells. (D) Luciferase reporter gene assay with IFN-β, ISRE, and NF-κB in HEK293T cells overexpressing with or without RIG-I-WT or R109C upon 5 μg/ml poly(I:C) stimulation for 12 hours or not. Data are presented as the mean±SD; n=3 independent experiments; ***P<0.001, t test. (E) Western blotting analysis of the activation of type I IFN and NF-κB signaling by using the indicated antibodies and IRF3 dimer detected by native PAGE in HEK293T cells overexpressing with or without RIG-I-WT or R109C for 24 hours upon 5 μg/ml poly(I:C) stimulation for 12 hours or not. (F) qPCR analysis of the expression of the IFN-stimulated genes in HEK293T cells treated as in (E). Data are presented as the mean±SD; n=3 independent experiments; **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, t test. NES, normalized enrichment score.

Transcriptional activity of the promoter of IFN-β, ISRE, and NF-κB was assessed by luciferase reporter gene assay. Significantly higher luciferase activity was detected in RIG-I-R109C–overexpressing cells than RIG-I-WT–transfected cells at the basal level, which was similar to that observed for the other four previously reported pathogenic variants (Supplemental Figure 2, A and B).9–11 Strikingly, luciferase activity in RIG-I-R109C–overexpressing cells upon no stimulation was even higher than RIG-I-WT–transfected cells stimulated with poly(I:C), which could model the actions of extracellular dsRNA15 (Figure 3D). After binding to viral dsRNA, RIG-I triggers the activation of type I IFN and NF-κB pathways, which could be reflected by the phosphorylation of TBK1, IRF3, and p65.8 Elevated phosphorylation was observed in these proteins in RIG-I-R109C–overexpressing cells, even without poly(I:C) stimulation, whereas RIG-I-WT–transfected cells presented similar levels of phosphorylation to WT cells transfected with vector (Figure 3E). The phosphorylated IRF3 is prone to be dimerized, which is essential for its nuclear translocation and the transcription of type I IFN.8 The secreted type I IFN binds to the IFNAR on the surface of adjacent cells, which leads to the activation of JAK1 and TYK2 and subsequent phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT2.8 In the RIG-I-R109C–overexpressing cells, we observed increased dimerization of IRF3 shown by native PAGE, increased phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT2, and elevated protein level of ISG-IFIT3 upon poly(I:C) stimulation or not (Figure 3E). Increased expression of ISGs was also confirmed by qPCR assay with overexpressing RIG-I-R109C than RIG-I-WT upon poly(I:C) stimulation or not (Figure 3F).

Taken together, these data suggest that the DDX58 R109C variant constitutively activates type I IFN signaling in vitro.

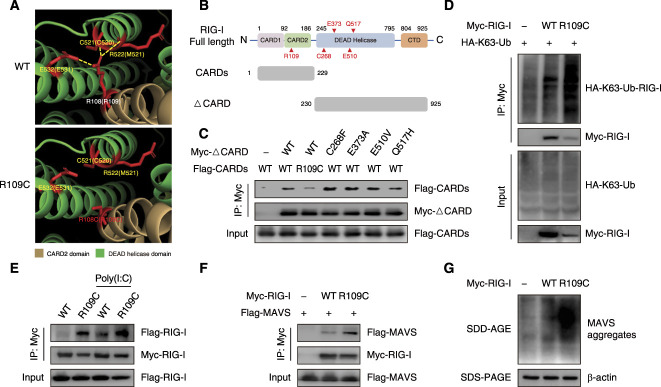

R109C Mutation Disrupts RIG-I Autoinhibition

Next, we investigated the molecular mechanism underlying the R109C mutation-mediated activation of RIG-I. In the absence of viral dsRNA, caspase activation and recruitment domains (CARDs) of RIG-I are masked by the intramolecular interaction with DEAD helicase domain, which leads RIG-I to a signaling repressed state.16 After Carboxy-terminal domain recognizing and binding to viral dsRNA in the cytosol, RIG-I undergoes a conformational change, releasing CARDs from the autorepressed state.16 The R109 residue is located in the interface between CARD2 domain and DEAD helicase domain.17 Structural modeling predicts that R109 in CARD2 domain may interact with C520, M521, and E531 in DEAD helicase domain without dsRNA bounding (Figure 4A). The substitution of Arg to Cys at residue 109 disrupts three polar bonds within the R109 residue (Figure 4A), which suggests that the R109C mutation may affect intramolecular interaction of CARDs and DEAD helicase domain. We constructed RIG-I fragments lacking the two N-terminal CARDs (ΔCARD) and WT/R109C mutated N-terminal CARDs (Figure 4B). By co-immunoprecipitation analysis, we observed that R109C mutated CARDs co-precipitated less ΔCARD fragments than WT CARDs, suggesting a weaker interaction between R109C mutated CARDs and DEAD helicase domain, and this defective binding was unique to R109C variant, which wasn’t observed for the other four previously reported pathogenic variants (Figure 4C). By attenuating the CARDs and DEAD helicase domain interaction, the R109C mutation may lead to the exposure of CARDs and release from autoinhibition state, which results in RIG-I signaling activation.

Figure 4.

R109C mutation activates IFN signaling by disrupting the autorepressed conformation of RIG-I. (A) Molecular dynamics snapshot of intramolecular interaction in the CARD2 (brown): DEAD helicase (green) interface of duck RIG-I WT and R109C. The corresponding residues in human RIG-I are shown in parentheses. The polar bonds are shown by yellow lines. Models were generated using Pymol v2.3.5 and Protein Data Bank accession 4a2w. (B) Schematic of human RIG-I full length domains and the truncated fragments (CARDs and ΔCARD) constructed in this study. (C) Co-precipitation of Myc-tagged WT ΔCARD or mutated ΔCARD with Flag-tagged WT CARDs or R109C mutated CARDs, respectively, in HEK293T cells overexpressing with indicated plasmids for 24 hours. Immunoprecipitation was carried out with anti-Myc beads, and the precipitates were analyzed using anti-Flag antibody. (D) K63-linked ubiquitination of RIG-I-WT or R109C detected by SDS-PAGE. HEK293T cells were transfected with Myc-tagged RIG-I-WT or R109C, together with HA-tagged K63-Ub for 24 hours. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc beads, followed by immunoblotting analysis with the indicated antibodies. (E) Co-precipitation of Flag-tagged RIG-I-WT or R109C with Myc-tagged RIG-I-WT or R109C, respectively, in HEK293T cells overexpressing with indicated plasmids for 24 hours, with or without 5 μg/ml poly(I:C) stimulation for 12 hours. Immunoprecipitation was carried out with anti-Myc beads, and the precipitates were analyzed using anti-Flag antibody. (F) Co-precipitation of Myc-tagged RIG-I-WT or R109C with Flag-tagged MAVS in HEK293T cells overexpressing with indicated plasmids for 24 hours. Immunoprecipitation was carried out with anti-Myc beads, and the precipitates were analyzed using anti-Flag antibody. (G) MAVS aggregates formation detected by SDD-AGE in HEK293T cells overexpressing with RIG-I-WT or R109C for 24 hours. Ub, ubiquitination.

Free CARDs are further activated by the K63-linked ubiquitination at K172, which contributes to effective RIG-I oligomerization and interaction with the adaptor protein MAVS on mitochondria.18 Because K63-linked ubiquitination is essential for RIG-I activation, we performed immunoprecipitation experiments to assess the ubiquitination level of RIG-I and found the RIG-I R109C K63-linked ubiquitination was significantly increased (Figure 4D).

The tetramer of RIG-I CARDs functions as a nucleus for the induction of MAVS filament formation. Filamentous MAVS then serves as a signaling platform for the recruitment and activation of TBK1, IRF3, and other downstream signaling, leading the transcriptional activation of type I IFN.19 The co-immunoprecipitation experiment showed that the interaction occurred between RIG-I-R109Cs but not between RIG-I-WTs without poly(I:C) stimulation (Figure 4E), indicating that the R109C mutation promotes spontaneous RIG-I oligomerization. In addition, RIG-I R109C could co-precipitate more MAVS (Figure 4F), and the induction of RIG-I R109C triggered MAVS aggregation more efficiently compared with RIG-I WT (Figure 4G).

These data suggest that the R109C mutation activates RIG-I-MAVS-mediated IFN signaling by disrupting the autorepressed conformation of RIG-I.

Potential Therapeutic Implication with JAK Inhibitor Baricitinib

When P1 was diagnosed with SLE and LN at the age of 12 years, she received intravenous methylprednisolone (MP) and cyclophosphamide (CTX) as induction therapy, and then switched to oral glucocorticoids and azathioprine for maintenance therapy. At the age of 28 years, she was given intravenous MP and CTX again as disease relapsed. After partial remission, she switched to MP 8 mg plus mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) 1.25 g and hydroxychloroquine 400 mg per day for about 6 years, but the titer of antibodies remained high, and complement levels were still low.

The strong IFN signature in patients with the DDX58 R109C variant suggests that JAK inhibitor therapy could be beneficial, as it has been used in the treatment of other IFNopathies.20 Subsequently, baricitinib treatment was initiated in patient P1. Baricitinib is an oral selective JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitor via STAT1 and STAT2 pathways, which may affect the release of several proinflammatory cytokines, including type I IFN, IL-6, and others.21

Before the targeted treatment, P1 stopped MMF for 5 weeks, and then began to receive oral baricitinib for 6 months. The dose of baricitinib was 2 mg once daily as recommended by the package insert. After baricitinib treatment for 6 months, the disease was stable, with the titer of antibody (ANA) decreasing to 1:512 and an elevated complement level. However, due to irreversible organ damage, renal disorder was not alleviated. No adverse effects or serious adverse events were observed (Supplemental Table 2).

To observe further the effectiveness of baricitinib treatment, we performed scRNAseq on the PBMCs of P1. Before baricitinib treatment, the patient exhibited enhanced gene expression in the type I IFN pathway such as IRF1 and IFI30 and proinflammatory cytokines such as IL1B and TNF compared with controls (Figures 2D and 5A). The difference in the gene expression was more significant in monocytes (Figure 5, A and B). After baricitinib treatment, we observed proinflammatory cytokines and ISG expression could be effectively suppressed, especially in CD14+ monocytes (Figure 5, A and B). Consistent with scRNAseq results, CBA analysis of serum from P1 showed a significantly decreased concentration of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, and IL-1β and chemokine CXCL10 after baricitinib treatment (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Treatment with baricitinib suppresses type I IFN signature. (A) Visualization of expression of IRF1, IFI30, IL1B, and TNF on UMAP plot from P1 before (n=8596 cells) and after baricitinib treatment for 3 months (n=5933 cells) and two unaffected controls (C1 [n=11,116 cells] and C2 [n=13,925 cells]). Colored dots indicate single cells, and cells with high expression level are highlighted in red. (B) Violin plots showing the expression of IFN-stimulated genes in the CD14+ and CD16+ monocytes of P1 before and after baricitinib treatment for 3 months compared with two unaffected controls (C1 and C2). (C) CBA analysis of serum proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β, and CXCL10) levels in P1 before and after baricitinib treatment for 3 months compared with six unaffected controls.

The suppression of type I IFN signature in P1 with JAK inhibitor therapy provided the clinical implication that inhibiting IFN/JAK/STAT pathway through baricitinib may be a potential treatment strategy for patients with LN caused by the DDX58 R109C heterozygous variant.

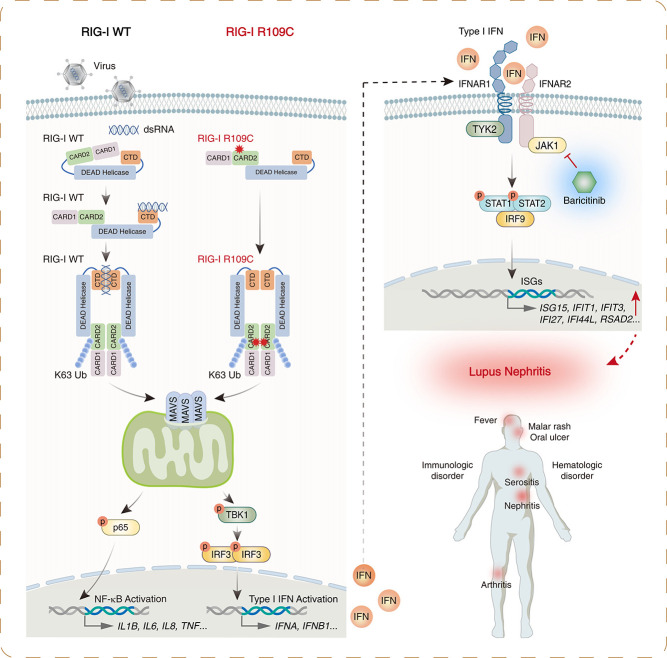

Discussion

In summary, we identified a novel heterozygous gain-of-function mutation, R109C, in the DDX58 gene in five unrelated families with LN. The RIG-I R109C mutation constitutively activated the type I IFN pathway due to impaired autoinhibition and increased K63 ubiquitination and MAVS aggregation. Furthermore, in one of the DDX58 R109C variant-driven LN patients, initial experience with the JAK inhibitor baricitinib has been positive, with the effective suppression of the type I IFN signature (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Schematic model of RIG-I R109C mutation leading to spontaneous activation of RIG-I and upregulation of type I IFN signaling and then causing LN.

DDX58 variants have been associated with an elevated IFN response in SMS patients.9–11 In this study, our patients also presented with a strong IFN signature but manifested as systematic inflammation and autoimmune disease, which were characterized strikingly by SLE and LN. This indicates that DDX58-mediated disorders may have phenotypic heterogeneity. This study demonstrates a new manifestation of DDX58-mediated disease with a distinct pathophysiology and genetic underpinning from SMS. SMS DDX58 variants (C268F and E373A), occurring in the HEL-1 domain (Supplemental Figure 2A), impair ATPase activity, preventing ATP hydrolysis, and recognizing self-RNA constitutively.22,23 The other two SMS DDX58 variants (E510V and Q517H) happened in the HEL-2i domain (Supplemental Figure 2A), weakening the RNA proofreading capabilities, failing to distinguish self from nonself RNA, and inducing hyperactivation of RIG-I.24 However, the R109C variant causing LN, located in the CARD2 domain (Supplemental Figure 2A), leads to defective CARDs binding and loss of autoinhibition of RIG-I. The different mechanisms result in various activation of RIG-I and a distinct pattern of upregulation of downstream IFN signaling, as a consequence, presenting with different phenotypes. However, identification of additional individuals with the DDX58 variant would help to define this condition further. More interestingly, in the PBMCs of our patient, scRNAseq revealed activation of the IFN signaling pathway was most significant in monocytes, highlighting the fundamental role of monocyte activation in the pathogenicity of patients with DDX58 R109C variant-driven LN.

Reduced penetrance can be seen in DDX58-associated diseases, as the patients AP1 in family 4 and AP2 in family 5 with the DDX58 R109C variant are asymptomatic. It is possible that other factors, such as modifier genes, may also contribute to disease expression. Reduced penetrance is commonly seen in dominant inherited diseases, which has been reported in individuals with the IFIH1 variant,6 for example.

The IFIH1 gene encodes the dsRNA helicase enzyme, melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5), which has similar functions to RIG-I as a dsRNA sensor.25 Gain-of-function variants in both MDA5 and RIG-I lead activation of the IFN signaling pathway. Heterozygous variants in IFIH1 have been reported in Aicardi–Goutières syndrome, SMS, and SLE.6,26–28 Intriguingly, overlapping phenotypes of SLE and SMS were identified in one patient with the IFIH1 R822Q variant.29 The disease spectrum of IFIH1 variants overlaps with those reported in this study. Given this, it appears that DDX58- and IFIH1-driven diseases are part of the same spectrum of errors in dsRNA sensor activation.

LN has been considered as a prototype of type I IFN-related kidney disease. It is supported by the fact that increased expression of ISGs in PBMCs is detectable in 50%–80% of patients with SLE,30 and high circulating type I IFN levels are associated with disease activity and flares in patients with LN.31 The common lesions of type I IFN-mediated kidney disease appear to be inflammatory-proliferative nephritis, collapsing glomerulopathy, and thrombotic microangiopathy.32 In this study, all the patients demonstrated the patterns of proliferative lesion; none of them showed collapsing glomerulopathy or thrombotic microangiopathy (Table 2). It is possible that type I IFN contributes to glomerular injury in LN through damaging resident kidney cells directly, inducing the production and deposition of autoantibodies, and recruiting the inflammatory cells.33 From this perspective, when screening the clinical phenotypes of enough individuals who carried the other DDX58 variants and presented with elevated levels of type I IFN, it is therefore possible that LN or LN-like patients would be identified. Notably, another interesting finding was that four of the patients had tubuloreticular inclusion in the glomerular endothelial cells under electromicroscopy (Figure 1B), which was referred as a lesion of IFN footprints. Our study revealed that the DDX58 R109C variant results in elevated type I IFN signaling, and the strong IFN signature was detected in our patients. Thus, it may be that this kind of ultrastructural feature is related to type I IFN, but this needs further validation.

JAK inhibitors have been approved as a therapeutic option for patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and SLE.34 In this study, one of the patients with the DDX58 variant received JAK inhibitor treatment and showed a certain response, with decreased activation of IFN signaling pathway. This is the initial experience of selected treatment with a JAK inhibitor on the basis of the DDX58 variant in a LN patient. It not only confirmed the pathogenic effect of the DDX58 mutation in the disease, but also shed light on more precisely targeted therapy for patients with the DDX58 variant. Apart from that, extended treatment observations in more patients with the DDX58 variant are needed to prove the clinical significance further.

SLE is a complex disorder, with extensive heterogeneous phenotypes. Current treatment for SLE does not adequately control disease activity and tissue damage, especially to the kidney, and is associated with significant side effects. Identifying genetic causes and finding potential therapeutic targets of LN is a major unmet clinical need. Additionally, dissecting the pathogenic genetic variants has a profound significance to define subsets of LN better and to shed light on the pathogenesis. This study provided the first example of how LN patients might be treated with targeted therapy when a genetic diagnosis is indicated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients, their families, and the unaffected controls for their contributions to this study. We thank Natalie T. Deuitch from the National Human Genome Research Institute for providing valuable advice and editing the manuscript. All samples were from Renal Biobank of National Clinical Research Center of Kidney Diseases, Jiangsu Biobank of Clinical Resources.

Footnotes

J.P., Y.W., X.H., and C.Z. contributed equally to this work.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Disclosures

All authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32141004 to Zhihong Liu, 31771548 and 81971528 to Q. Zhou, and 82170739 to C. Zhang), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LR19H100001 to Q. Zhou), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2021M692779 to Y. Wang), The Open Project of Jiangsu Biobank of Clinical Resources (JSRB2021-02 to Q. Zhou), and Jiangsu Biobank of Clinical Resources (BM2015004-1 to Zhihong Liu).

Author Contributions

Y. An, Y. Chen, E. Gao, Zhengzhao Liu, Y. Jin, F. Xu, C. Zhang, Y. Zhang, and C. Zheng were responsible for resources; X. Chen and X. Han were responsible for software; X. Han, J. Peng, and Y. Wang were responsible for data curation; X. Han, J. Peng, Y. Wang, Z. Yang, and J. Zhang were responsible for the formal analysis; Zhihong Liu, J. Peng, Y. Wang, C. Zhang, and Q. Zhou were responsible for conceptualization and project administration; Zhihong Liu, Y. Wang, C. Zhang, and Q. Zhou were responsible for funding acquisition; Zhihong Liu and Q. Zhou were responsible for the investigation and supervision and reviewed and edited the manuscript; and J. Peng and Y. Wang wrote the original draft of the manuscript.

Data Sharing Statement

All data associated with this study are present in the paper or the Supplemental Material. Primary data of DNA-based and RNA-based assays can be accessed by contacting the corresponding authors (Q. Zhou or Zhihong Liu).

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://links.lww.com/JSN/D684.

Supplemental Appendix 1. Clinical synopsis of patients with the DDX58 R109C variant.

Supplemental Table 1. Clinical comparison of individuals with DDX58-associated Singleton–Merten syndrome.

Supplemental Table 2. Changes of clinical parameters before and after treatment with baricitinib.

Supplemental Figure 1. Hyperactivation of type I IFN and NF-κB signaling in patients with the DDX58 R109C variant.

Supplemental Figure 2. Functional comparison of R109C variant with previously established pathogenic variants in DDX58.

References

- 1.Demirkaya E, Sahin S, Romano M, Zhou Q, Aksentijevich I: New horizons in the genetic etiology of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus-like disease: Monogenic lupus and beyond. J Clin Med 9: 712, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu YL, Brookshire BP, Verani RR, Arnett FC, Yu CY: Clinical presentations and molecular basis of complement C1r deficiency in a male African-American patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 20: 1126–1134, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Mayouf SM, Sunker A, Abdwani R, Abrawi SA, Almurshedi F, Alhashmi N, et al. : Loss-of-function variant in DNASE1L3 causes a familial form of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet 43: 1186–1188, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bilginer Y, Düzova A, Topaloğlu R, Batu ED, Boduroğlu K, Güçer Ş, et al. : Three cases of spondyloenchondrodysplasia (SPENCD) with systemic lupus erythematosus: A case series and review of the literature. Lupus 25: 760–765, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belot A, Kasher PR, Trotter EW, Foray AP, Debaud AL, Rice GI, et al. : Protein kinase cδ deficiency causes mendelian systemic lupus erythematosus with B cell-defective apoptosis and hyperproliferation. Arthritis Rheum 65: 2161–2171, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng S, Lee PY, Wang J, Wang S, Huang Q, Huang Y, et al. : Interstitial lung disease and psoriasis in a child with Aicardi–Goutières syndrome. Front Immunol 11: 985, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boulisfane-El Khalifi S, Viel S, Lahoche A, Frémond ML, Lopez J, Lombard C, et al. : COPA syndrome as a cause of lupus nephritis. Kidney Int Rep 4: 1187–1189, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y, Olagnier D, Lin R: Host and viral modulation of RIG-I-mediated antiviral immunity. Front Immunol 7: 662, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferreira CR, Crow YJ, Gahl WA, Gardner PJ, Goldbach-Mansky R, Hur S, et al. : DDX58 and classic Singleton–Merten syndrome. J Clin Immunol 39: 75–80, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prasov L, Bohnsack BL, El Husny AS, Tsoi LC, Guan B, Kahlenberg JM, et al. : DDX58(RIG-I)-related disease is associated with tissue-specific interferon pathway activation. J Med Genet 59: 294–304, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jang MA, Kim EK, Now H, Nguyen NT, Kim WJ, Yoo JY, et al. : Mutations in DDX58, which encodes RIG-I, cause atypical Singleton–Merten syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 96: 266–274, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Q, Yang D, Ombrello AK, Zavialov AV, Toro C, Zavialov AV, et al. : Early-onset stroke and vasculopathy associated with mutations in ADA2. N Engl J Med 370: 911–920, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tao P, Sun J, Wu Z, Wang S, Wang J, Li W, et al. : A dominant autoinflammatory disease caused by non-cleavable variants of RIPK1. Nature 577: 109–114, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim H, de Jesus AA, Brooks SR, Liu Y, Huang Y, VanTries R, et al. : Development of a validated interferon score using NanoString technology. J Interferon Cytokine Res 38: 171–185, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoneyama M, Kikuchi M, Natsukawa T, Shinobu N, Imaizumi T, Miyagishi M, et al. : The RNA helicase RIG-I has an essential function in double-stranded RNA-induced innate antiviral responses. Nat Immunol 5: 730–737, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kowalinski E, Lunardi T, McCarthy AA, Louber J, Brunel J, Grigorov B, et al. : Structural basis for the activation of innate immune pattern-recognition receptor RIG-I by viral RNA. Cell 147: 423–435, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrage F, Dutta K, Nistal-Villán E, Patel JR, Sánchez-Aparicio MT, De Ioannes P, et al. : Structure and dynamics of the second CARD of human RIG-I provide mechanistic insights into regulation of RIG-I activation. Structure 20: 2048–2061, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okamoto M, Kouwaki T, Fukushima Y, Oshiumi H: Regulation of RIG-I activation by K63-linked polyubiquitination. Front Immunol 8: 1942, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hou F, Sun L, Zheng H, Skaug B, Jiang QX, Chen ZJ: MAVS forms functional prion-like aggregates to activate and propagate antiviral innate immune response. Cell 146: 448–461, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crow YJ, Neven B, Frémond ML: JAK inhibition in the type I interferonopathies. J Allergy Clin Immunol 148: 991–993, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubo S, Nakayamada S, Sakata K, Kitanaga Y, Ma X, Lee S, et al. : Janus kinase inhibitor baricitinib modulates human innate and adaptive immune system. Front Immunol 9: 1510, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lässig C, Matheisl S, Sparrer KM, de Oliveira Mann CC, Moldt M, Patel JR, et al. : ATP hydrolysis by the viral RNA sensor RIG-I prevents unintentional recognition of self-RNA. eLife 4: 4, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng J, Wang C, Chang MR, Devarkar SC, Schweibenz B, Crynen GC, et al. : HDX-MS reveals dysregulated checkpoints that compromise discrimination against self RNA during RIG-I mediated autoimmunity. Nat Commun 9: 5366, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lei Y, Fei P, Song B, Shi W, Luo C, Luo D, et al. : A loosened gating mechanism of RIG-I leads to autoimmune disorders. Nucleic Acids Res 50: 5850–5863, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan YK, Gack MU: Viral evasion of intracellular DNA and RNA sensing. Nat Rev Microbiol 14: 360–373, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rice GI, Del Toro Duany Y, Jenkinson EM, Forte GM, Anderson BH, Ariaudo G, et al. : Gain-of-function mutations in IFIH1 cause a spectrum of human disease phenotypes associated with upregulated type I interferon signaling. Nat Genet 46: 503–509, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rutsch F, MacDougall M, Lu C, Buers I, Mamaeva O, Nitschke Y, et al. : A specific IFIH1 gain-of-function mutation causes Singleton–Merten syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 96: 275–282, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Eyck L, De Somer L, Pombal D, Bornschein S, Frans G, Humblet-Baron S, et al. : Brief report: IFIH1 mutation causes systemic lupus erythematosus with selective IgA deficiency. Arthritis Rheumatol 67: 1592–1597, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pettersson M, Bergendal B, Norderyd J, Nilsson D, Anderlid BM, Nordgren A, et al. : Further evidence for specific IFIH1 mutation as a cause of Singleton–Merten syndrome with phenotypic heterogeneity. Am J Med Genet A 173: 1396–1399, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baechler EC, Batliwalla FM, Karypis G, Gaffney PM, Ortmann WA, Espe KJ, et al. : Interferon-inducible gene expression signature in peripheral blood cells of patients with severe lupus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 2610–2615, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Postal M, Vivaldo JF, Fernandez-Ruiz R, Paredes JL, Appenzeller S, Niewold TB: Type I interferon in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Immunol 67: 87–94, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lodi L, Mastrolia MV, Bello F, Rossi GM, Angelotti ML, Crow YJ, et al. : Type I interferon-related kidney disorders. Kidney Int 101: 1142–1159, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ding X, Ren Y, He X: IFN-I mediates lupus nephritis from the beginning to renal fibrosis. Front Immunol 12: 676082, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nash P, Kerschbaumer A, Dörner T, Dougados M, Fleischmann RM, Geissler K, et al. : Points to consider for the treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases with Janus kinase inhibitors: A consensus statement. Ann Rheum Dis 80: 71–87, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data associated with this study are present in the paper or the Supplemental Material. Primary data of DNA-based and RNA-based assays can be accessed by contacting the corresponding authors (Q. Zhou or Zhihong Liu).