Keywords: hepatitis, economic analysis, epidemiology and outcomes, chronic hemodialysis, cost-benefit analysis, health policy catalyst

Abstract

Significance Statement

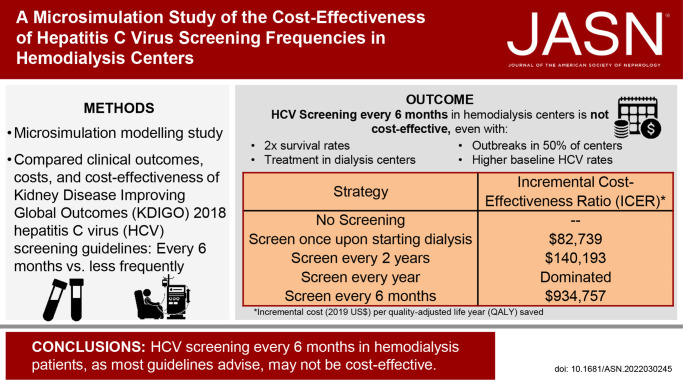

Studies examining the cost-effectiveness of hepatitis C virus (HCV) screening methods or frequencies are lacking. The authors examined the cost-effectiveness of the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2018 guidelines' recommendation to test in-center hemodialysis patients for HCV every 6 months. They demonstrated that with current HCV prevalence, incidence, and treatment practices in patients receiving hemodialysis, screening for HCV every 6 months is not cost-effective under a willingness-to-pay threshold of US$150,000, even if baseline survival rates doubled or all patients received treatment on diagnosis. Screening only at dialysis initiation or every 2 years are cost-effective approaches, however, with incremental cost-effectiveness ratios of $82,739 and $140,193, respectively, per quality-adjusted life-year saved compared with no screening. These data suggest that reevaluation of HCV screening guidelines in hemodialysis patients should be considered.

Background

National guidelines recommend twice-yearly hepatitis C virus (HCV) screening for patients receiving in-center hemodialysis. However, studies examining the cost-effectiveness of HCV screening methods or frequencies are lacking.

Methods

We populated an HCV screening, treatment, and disease microsimulation model with a cohort representative of the US in-center hemodialysis population. Clinical outcomes, costs, and cost-effectiveness of the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2018 guidelines–endorsed HCV screening frequency (every 6 months) were compared with less frequent periodic screening (yearly, every 2 years), screening only at hemodialysis initiation, and no screening. We estimated expected quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) between each screening strategy and the next less expensive alternative strategy, from a health care sector perspective, in 2019 US dollars. For each strategy, we modeled an HCV outbreak occurring in 1% of centers. In sensitivity analyses, we varied mortality, linkage to HCV cure, screening method (ribonucleic acid versus antibody testing), test sensitivity, HCV infection rates, and outbreak frequencies.

Results

Screening only at hemodialysis initiation yielded HCV cure rates of 79%, with an ICER of $82,739 per QALY saved compared with no testing. Compared with screening at hemodialysis entry only, screening every 2 years increased cure rates to 88% and decreased liver-related deaths by 52%, with an ICER of $140,193. Screening every 6 months had an ICER of $934,757; in sensitivity analyses using a willingness-to-pay threshold of $150,000 per QALY gained, screening every 6 months was never cost-effective.

Conclusions

The KDIGO-recommended HCV screening interval (every 6 months) does not seem to be a cost-effective use of health care resources, suggesting that re-evaluation of less-frequent screening strategies should be considered.

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is highly prevalent among ESKD populations in the United States; approximately 7.2%–8.4% of chronic hemodialysis patients are HCV seropositive.1,2 HCV infection in dialysis patients is associated with increased mortality,1 and patients with ESKD are among the few populations for whom the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and US Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommend periodic—not just one time—HCV screening.3,4

The Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2018 HCV guidelines recommend screening all patients for HCV infection on initiation of hemodialysis or on transferring dialysis centers or modality.5 In addition, they recommend routine testing, by HCV immunoassay (antibody) or ribonucleic acid (RNA) testing, of all hemodialysis patients every 6 months, with increased screening frequency if a new HCV infection is detected within a center; every 1–3 months is suggested during outbreaks (Table 1). Individuals with resolved (spontaneously cleared or treated) HCV infection should be RNA-tested every 6 months (as their antibody testing will remain positive). Furthermore, the guideline suggests checking serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels in all hemodialysis patients monthly and diagnostic testing for HCV for any unexplained ALT elevations.

Table 1.

Professional society recommendations for hepatitis C virus screening in individuals on chronic hemodialysis

| Guideline | Date | General Screening Frequencya | Outbreak Screening Frequency | Type of Testingb | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KDIGO | 2018 | Every 6 months | Every 1–3 months | Antibody with reflex to RNA or just RNAc; monthly ALT | Jadoul et al.5 |

| CDC | 2020 | “Routine periodic” (none specified) | None specified | Not specifiedd | Schillie4 |

| USPSTF | 2020 | “Routine periodic” (none specified)d | None specified | Not specifiede | Owens et al.3 |

| AASLD and IDSA | 2021f | Periodic/none specified | None specified | RNAg | Lawitz et al.50 |

| US CDCh | 2001 | Every 6 months | Every 1–3 months | Antibody; monthly ALT | AASLD6 |

KDIGO, Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes; RNA, ribonucleic acid; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CDC, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; USPSTF, US Preventative Services Task Force; AASLD, American Association for the Study of Liver Disease; IDSA, Infectious Diseases Society of America; HD, hemodialysis; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

In addition to screening at entry to a new HD center, which is recommended by each guideline.

For individuals not already HCV seropositive; all guidelines recommend RNA testing only for individuals with spontaneously cleared or treated HCV, who will remain seropositive.

RNA testing alone recommended in HD centers with high HCV prevalence.

Dialysis is not even specifically mentioned in the USPSTF guideline as one of the risk factors for periodic screening (only injection drug use is specifically named).

For HD population in particular; HCV antibody testing with reflex to RNA for positive antibody testing recommended in general.

This a frequently updated living document guideline, with most recent updates to testing recommendations in fall 2021.

RNA testing recommended for immunocompromised individuals, including those on chronic HD.

This was a specific guideline for preventing infections in chronic HD patients.

By contrast, although the 2020 USPSTF and CDC guidelines recommend consideration of periodic screening in individuals on chronic hemodialysis, only the 2001 CDC guideline specifies a screening frequency (every 6 months) or the type of screening test to use for hemodialysis patients (Table 1; consistent with KDIGO recommendations).3,4,7 Similarly, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) joint guidelines also note hemodialysis patients merit additional HCV screening but also without advising a frequency.6 The AASLD/IDSA guideline also suggests screening using RNA rather than antibody for immunocompromised populations, including chronic dialysis patients.

In practice, most large dialysis organizations adhere to the KDIGO testing strategy (large dialysis organization online source and expert opinion of authors).8 Each guideline's screening frequency and test choice recommendations are based on expert opinion; to our knowledge, no data exist to compare the clinical or cost-effectiveness of different HCV screening strategies in hemodialysis patients.

Central to these recommendations is the desire to reduce, or ideally eliminate, HCV transmission within the dialysis unit. While HCV acquisition in dialysis centers is of great clinical concern and a marker of infection control lapses, overall, it is quite rare. Older national surveillance data from 2002 reported an annual HCV incidence rate in US dialysis centers of 0.34%9; data collected from 45 facilities from 1997 to 2004 demonstrated a slightly higher annual incidence of 0.96%.10 However, these studies occurred when HCV prevalence among hemodialysis patients was much higher (estimated between 9% and 40%) and attributed to contaminated blood transfusions pre-1992 or intraunit transmissions before most dialysis centers screened for HCV.7 In a more contemporary period, only 102 total outbreak-associated cases of HCV transmission within a dialysis unit were reported to the CDC from 2008 to 2017.11 Yet, dialysis centers routinely test patients far more frequently than is suggested even for other categories of individuals at highest risk of HCV acquisition, such as people who inject drugs, men who have sex with men, or individuals living with HIV, calling into question the cost-effectiveness of this strategy.3–5,7,12 While dialysis laboratory tests are included in the Medicare bundled payments to dialysis centers, unnecessary testing diverts resources away from other health expenditures and patients bear their own coinsurance costs related to testing. Furthermore, false positive testing, as occurs in approximately 1%–2% of patients, can result in additional costs and emotional stressors for patients and providers.13

We undertook this study to assess the relative cost-effectiveness of different guideline-based HCV testing strategies for in-center hemodialysis patients. We modeled scenarios with and without intraunit HCV transmission. Using generally accepted “willingness-to-pay” thresholds, we aimed to determine the most cost-effective HCV screening strategy for hemodialysis centers.

Methods

Project Overview

For this study, we used a Monte Carlo–based microsimulation model, Hepatitis C cost-effectiveness (HEP-CE), described previously,14,15 which simulates a hypothetical cohort of people through states of HCV infection, liver disease, and HCV diagnosis and treatment over a specified time horizon. The model simulates a patient cohort by assigning a baseline HCV prevalence, age distribution, population size, distribution of liver disease stages, and proportion with active or previous injection drug use. This cohort then progresses through a series of 1-month cycles. In each cycle, hypothetical individuals experience literature-defined probabilities of transitioning between states: initiation or cessation of injection drug use, HCV infection, liver disease progression, HCV diagnosis, linkage to care and treatment, and death.

We employed the HEP-CE model to compare the clinical benefits and cost-effectiveness of various HCV screening strategies for in-center hemodialysis patients.

Model Overview

HEP-CE uses states to model each hypothetical individual's progression through the HCV care cascade (infected, tested, diagnosed, linked to care, treated, and cured) and liver disease (measured by METAVIR fibrosis stages, F0–F4, and decompensated cirrhosis; Supplemental Exhibit 1). Higher liver disease stages correspond to increased health care costs and increased mortality risk for the patient. After recovery (sustained virologic response [SVR]), individuals' risk of liver disease progression stops, and mortality risk from liver disease decreases, unless HCV reinfection occurs. Treatments and other interventions and care costs accrue as the patient progresses through various stages of the cascade of care. This model structure allows us to follow individual patients through HCV infection, disease, and care to compare health outcomes and costs of different testing strategies under a variety of scenarios. We used the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) to guide reporting of this analysis (Supplemental Table 1).

Population, Setting, Perspective

To simulate the adult US hemodialysis population, we based our cohort on 2017 United States Renal Data System (USRDS) data, which includes all individuals enrolled in outpatient dialysis for at least 6 months in the United States.16 Age- and sex-stratified mortality from competing risks of death, including ESKD, and yearly per-patient health care costs were determined using data for in-center hemodialysis patients from USRDS (Table 2). For baseline HCV seroprevalence (7.2%) and liver fibrosis distribution, we used secondary data analysis from a large hemodialysis study (Supplemental Table 3)1 and assumed 33% of those seropositive had ongoing current infection. The relatively low prevalence of infection among those seropositive reflects past HCV treatment with highly effective directing acting antiviral therapies (personal communication with director of a large dialysis organization). We conducted the study from a Medicare perspective (as ESKD is a categorical qualification for Medicare coverage) to determine the health care costs and cost-effectiveness of guideline-recommended HCV screening frequency in hemodialysis patients.

Table 2.

Key model parameter estimates, ranges, and sources

| Parameter | Estimatea | Range/Distributionb | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population/demography | |||

| Prevalence of IDU | Current: 0.3% | 0.25–10× baseline current IDU rate | 21-23 |

| Former: 6.0% | |||

| Distribution of METAVIR fibrosis stage | Varies by age/sex | 1 | |

| Mean age (years) | 63.4 | 18–99 | 15 |

| Chronic HCV infection | 2.4% | 0%–5.4% | 1, 8 |

| Background mortality rates | Varies by age/sexc | 0.5× baseline rates | 15 |

| IDU | |||

| SMR, former or current IDU | 1.58 | 1.27–1.67 | 51 |

| HCV disease | |||

| IDU-related HCV incidence (cases/100 PY) | 12.3 | 8.5–17.8 | 52 |

| HD center outbreak-related HCV incidence (cases/100 PY) | 4.23 | 1.68–31.8, Poisson | 10, 53, 54 |

| % HD centers with an HCV outbreak | 1% | 1%–50% | 10 |

| Monthly cirrhosis mortality | |||

| F4 (deaths/100 PY) | 3 | 1–5, Poisson | 55 |

| Decompensated cirrhosis (deaths/100 PY) | 21 | 3–30, Poisson | 55 |

| Post-SVR mortality multiplier | 0.06 | 0.01–1 | 56 |

| Screening and linkage | |||

| Background HCV screening (outside HD) | 0 | 0%–20.8% | 57 |

| Referral to HCV-specific care | 95% | — | Expert opinion |

| Percent of patients successfully linked to and retained in treatment | 75% | 50–100% | 58-64 |

| HCV antibody test sensitivity/specificity | 98%/98% | 88%d–98%/98%–99% (Beta) | 12, 37-41 |

| HCV RNA test sensitivity/specificity | 99.3%/99.9% | 98%–100%/100% | 65 |

| Utilities | |||

| Background (HD-specific) | 0.69 | 0.59–0.80 | 39 |

| Costs (2019 USD) | |||

| HCV antibody test | $15.85 | Gamma ($13.19, $18.27) | 33 |

| HCV RNA test | $79.41 | Gamma ($72.85, $85.62) | 33 |

| False-positive test result coste | $492.63 | — | 33 |

| Treatment cost (per month) | $9507.35 | Gamma |

IDU, injection drug use; HCV, hepatitis C virus; SMR, standardized mortality ratio; HD, hemodialysis; PY, person-years; SVR, sustained virologic response (cure); RNA, ribonucleic acid.

All probabilities, incidences, and costs are monthly unless otherwise indicated.

Range listed for deterministic sensitivity analyses, distribution for probabilistic sensitivity analyses, with 25th and 75th percentile estimates listed in parentheses for test costs.

On the basis of age- and sex-stratified annual mortality rates from USRDS 2019 Reference Sheet H.8_1 with overall mortality across all ages of 183.4 deaths per 1000 person-years.

Lower antibody sensitivity range represents estimate halfway in between historical low HCV antibody sensitivity estimates59,60 and more recent, small studies with sensitivity 94%–100% in dialysis patients.61-63

False-positive test costs include HCV genotype and two physician visits.

HCV Incidence

We simulated HCV incidence through either ongoing high-risk behavior (a present but low prevalence of injection drug use as this is the primary risk factor for HCV transmission in the United States)4 or hemodialysis center outbreaks. Simulated individuals were only exposed to a risk of HCV infection if they were currently injecting drugs or experiencing a hemodialysis center outbreak in that cycle of the simulation.

Outbreak Simulation

To simulate an outbreak, we model two scenarios: (1) a dialysis center without an outbreak and (2) the same center with an outbreak. In the simulation of an outbreak, HCV incidence is constant throughout the outbreak and is informed by CDC reports of dialysis center outbreaks. All outbreaks start 1 year into the simulation (cycle 13). The screening strategy determines outbreak duration—with more frequent screening resulting in shorter outbreak periods because the frequent testing detects cases more quickly and removes them from the transmission chain. We then take a weighted average of outcomes from the two simulations. The weight for the simulation with an outbreak is the probability of an outbreak occurring in a dialysis center, and the weight for the simulation without outbreak is 1 minus the probability of outbreak. The result is a simulation that reflects the average experience of dialysis patients in the United States, assuming a given risk of an outbreak occurring (see Supplemental Table 2 for full description).

On the basis of review of CDC-reported HCV outbreaks (102 cases at 21 hemodialysis centers from 2008 to 2017) and an average of 6126 hemodialysis centers operating in the United States over that period, we estimated that over a 20-year simulation, approximately 0.68% of hemodialysis centers would experience a reported HCV outbreak.11,41,42 Given expected under-reporting,43 we estimated that approximately 1% of centers would experience an HCV outbreak overall. To simulate this, we first ran strategies with no outbreak simulated and then ran each strategy again simulating an outbreak. During the simulated outbreak, in addition to the baseline screening intervals, we modeled increased screening frequency (every 3 months) to reflect professional society recommendations to increase screening to every 1–3 months during an outbreak.

Injection Drug Use Prevalence

We derived prevalence of injection drug use (as a proxy for HCV risk) using age- and sex-specific reported drug use from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health combined with electronic health record problem list and social history data from a national network of federally qualified health centers (OCHIN, formerly the Oregon Community Health Information Network) to determine the proportions of individuals with active, former, or no injection drug use by sex and age, as described elsewhere.17-19,44,45 We used monthly injection drug use cessation probabilities from the AIDS Linked to the IntraVenous Experience (ALIVE) cohort46 and assumed no new injection drug use initiation or relapse for individuals already on hemodialysis (expert opinion).

HCV Disease

To simulate various states of liver damage, which occur due to HCV infection, we assigned METAVIR stage-specific liver disease (fibrosis) progression rates from the literature with a mean to time to development of cirrhosis of 35 years.47,48 While currently infected, each cycle, individuals are exposed to a stage-specific fibrosis progression probability. In this way, we use stochastic probability to determine, which individuals go on to experience cirrhosis and its inherent higher mortality rates, costs, and lower quality-of-life measures.

HCV Diagnosis, Linkage

We assumed for this study 100% adherence to screening guidelines among hemodialysis centers because most hemodialysis centers have procedures in place for universal testing among patients for guideline-recommended regular screening tests. We also assumed a 100% acceptance rate of HCV testing for patients given frequent care exposure (thrice weekly) and laboratory testing during such sessions. To estimate rates of linkage to HCV-specific care once diagnosed and loss to follow-up before initiating treatment, we used high-end estimates from general population HCV linkage to care in the direct-acting antiviral era given the frequent health care exposure of this population but knowledge that some patients will not link to appointments outside the hemodialysis center or may have contraindications to treatment (e.g., medication interactions; Table 2). In sensitivity analyses, we varied both screening and linkage rates, inclusive of a 100% linkage to care rate to simulate HCV treatment in hemodialysis centers, which is a proposed future endeavor but only practiced in limited settings currently.49 We also simulated a high relinkage rate for individuals who attend an initial HCV treatment referral but are subsequently lost to HCV follow-up given the likelihood of frequent reminders and re-referrals from the hemodialysis center (50% relinkage rate over 2 years and a new linkage opportunity with each additional HCV screen; expert opinion).

HCV Treatment

We simulated HCV treatment using 8 weeks of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir for all patients to reflect a pangenotypic regimen approved and recommended for patients with ESKD.50 We based treatment efficacy on ESKD-specific (largely hemodialysis-specific) results from clinical trials.51–53 We did not simulate retreatment for treatment failures. Costs of treatment, monthly visits, and toxicity were determined from federal pricing lists and expected number of HCV-specific visits and laboratory tests during treatment evaluation and monitoring (Table 2; Supplemental Table 4).40,54

Calibration

The HEP-CE model was previously calibrated to match survival, HCV, and liver disease targets in a general population.15,19 For this study, we calibrated overall survival to USRDS survival data (Supplemental Figure 1A) and also graphed the per cycle incident HCV cases and prevalent cirrhosis cases (Supplemental Figure 1, B and C) because of our added outbreak simulation to ensure reasonable numbers resulted. We also ran 1000 simulations of increasing sample size from 1 to 400 million and compared mean incremental quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) between strategies to determine the sample size needed to minimize stochastic variation (Supplemental Figure 1D).

Strategies

To test the cost-effectiveness of different HCV screening frequencies in the hemodialysis population, we applied five different strategies to the simulations. We chose strategies on the basis of current KDIGO recommendations for hemodialysis centers (every 6-month screening) and compared this with strategies simulating less frequent (every year, every 2 years, or only screening on entry to a hemodialysis center) or no screening (as a comparator).5,6 We ran each strategy with and without a simulated HCV outbreak, beginning 1 year into the simulation, for a 20-year time horizon. To reduce Monte Carlo variance, we used a cohort size of 200 million simulated individuals (Supplemental Figure 1D).

Costs and Health Utilities

We determined costs of HCV disease, screening, staging, and treatment from the literature and federal cost schedules (Table 2; Supplemental Table 4)40,54–56 and expressed costs in 2019 US$, with a 3% discount rate to account for time preference. For preference-based health outcomes, we measured health utilities through QALYs, on the basis of published studies for individuals with HCV infection,34,57 injection drug use,35 and on hemodialysis36 (Table 2; Supplemental Table 4). We combined multiple utility functions for one health state (for example, utilities for ESKD and HCV disease stage in an HCV-infected ESKD patient) by multiplying the two utility values.37

Outcomes of Interest

Simulation outcomes included average remaining lifespan, number of HCV infections identified and cured (defined as those achieving SVR, which is the conventional definition of cure), number of cirrhotic individuals, liver-related deaths, QALYs, and undiscounted and discounted costs. We calculated incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) comparing each strategy with the next least expensive nondominated strategy. We interpreted ICERs using a willingness-to-pay threshold of US$150,000/QALY gained.37,38 To estimate a total Medicare budgetary impact and total QALYs gained, and cases of cirrhosis and liver death avoided by each strategy, we also multiplied average discounted costs and QALYs for each strategy by the total number of dialysis patients in the United States reported by the USDRS.58

Sensitivity Analyses

We reviewed medical literature to derive prior feasible ranges for key model parameters and conducted a series of deterministic one-way sensitivity analyses by ranging those parameters through their feasible range (Table 2). In addition, we developed probability density functions around key model parameters for probabilistic sensitivity analyses, including treatment cost, HCV antibody and RNA test costs, outbreak-related HCV incidence, mortality from cirrhosis, and HCV antibody and RNA test sensitivity and specificity. We also investigated several scenarios of interest including (1) HCV treatment in hemodialysis centers (decreased loss to follow-up to 0% but still simulated approximately 5% of patients as ineligible for or declining treatment and a small percent with treatment failure; Supplemental Table 4), (2) decreased future ESKD-related mortality to simulate either a healthier population or future advances in dialysis care, (3) using HCV RNA testing only rather than antibody testing with reflex to RNA if positive, (4) simulating a decreased sensitivity of HCV antibody in the hemodialysis population, and (5) higher than reported rates of injection drug use and HCV outbreaks. For the RNA testing–only strategy, we simulated shortened outbreak periods as RNA testing only would essentially shorten the “window period” during which someone is infected but not yet detected by testing from approximately 6 months to approximately 2 weeks (Supplemental Table 2) and directly compared the RNA testing–only strategies with base case and to lower HCV antibody sensitivity strategies.

This study was considered not human subjects research by the Boston University Medical Campus institutional review board given use of only published or deidentified data.

Results

Base Case

Without any HCV screening, the average life expectancy was 5.22 years, and 2.59% of the population experienced an HCV infection (Table 3). In the simulation, 0.69% developed cirrhosis from HCV, and 0.18% experienced a liver-related death. Screening for HCV only at hemodialysis initiation identified 94.2% of HCV infections, and 79.3% of HCV-infected individuals were cured. This approach decreased the number of cirrhotic individuals by 37% and liver deaths by 82%, with an ICER of $82,739 per QALY saved compared with no screening. With a US center hemodialysis population of 492,096 people, that translates into 1248 fewer cases of cirrhosis and 741 fewer deaths from liver disease compared with no screening. Increasing to every 2-year screening decreased total HCV infections to 2.57% of the population and identified 97.8% of infections, and 88.2% of those infected achieved cure. This decreased cirrhotic individuals by an additional 5.6% (118 fewer cirrhotic patients) and liver-related deaths by 52% (79 fewer deaths), with an ICER of $140,193, over screening at hemodialysis entry only. Screening annually (dominated) or every 6 months (ICER $934,757) was not cost-effective using a willingness-to-pay threshold of $150,000. Annual and every 6-month screening identified more HCV infections than screening every 2 years (98.5%–99.0% versus 97.8%) and decreased the number of cirrhotic individuals by an additional 1.5%–3.2% (approximately 32–63 fewer cases), which resulted in only 3%–3.5% of cirrhotic individuals experiencing a liver-related death compared with 4.2% (17–27 fewer deaths) in the screening every 2 years of strategy. HCV treatment costs varied little between strategies ($215–249 per person), whereas testing costs varied from $26 to 346 per person (Supplemental Table 5).

Table 3.

Base case clinical and cost-effectiveness results

| Strategy | HCV Infections, % | HCV Infections Identified, Lifetime, % | SVR Achieved (% of Total Infections) | Cirrhosis Cases, % | Liver Related Deaths, % | Remaining Life Expectancy | Undiscounted Cost ($) | Discounted Cost, $ | Discounted QALYs | ICER | Incremental Medicare 20-Year Budgetary Impacta | Population-Level QALYs Gaineda |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No screening | 2.59 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.686 | 0.184 | 5.2202 | $500,591 | $434,932 | 3.0872 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Screen on entering dialysis center | 2.58 | 94.2 | 79.3 | 0.432 | 0.033 | 5.2272 | $501,364 | $435,587 | 3.0951 | $82,739 | $322,145,027 | 3893 |

| Screen every 2 yr | 2.57 | 97.8 | 88.2 | 0.408 | 0.017 | 5.2278 | $501,479 | $435,680 | 3.0958 | $140,193 | $45,892,231 | 327 |

| Screen every yr | 2.56 | 98.5 | 90.5 | 0.402 | 0.014 | 5.2273 | $501,516 | $435,719 | 3.0957 | Dominated | Dominated | Dominated |

| Screen every 6 mo | 2.55 | 99.0 | 92.5 | 0.395 | 0.012 | 5.2277 | $501,742 | $435,904 | 3.0960 | $934,757 | $110,307,782 | 118 |

HCV, hepatitis C virus; SVR, sustained virologic response; QALYs, quality-adjusted life-years; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

Incremental cost or QALYs of each strategy over the next least expensive, nondominated strategy multiplied by the total number of people on hemodialysis in the United States (492,096 people in 2019 per the United States Renal Data System).58

On the basis of USRDS estimates that 492,096 people received center hemodialysis in the United States in 2019, screening at dialysis entry over no screening or treatment would cost $322,145,027 over 20 years for this cohort and save 3893 QALYs (Table 3). Screening every 2 years would likely generate 327 additional QALYs for an incremental cost of $45,892,231, and screening every 6 months would likely generate an additional 118 QALYs for an incremental cost of $110,307,782 over every 2-year screening.

Sensitivity Analyses

Perfect Linkage to Care

Simulating perfect linkage to care for individuals diagnosed with HCV to represent HCV treatment in hemodialysis centers without loss to follow-up for those referred off-site to care, we observed similar results, though with higher ICERs. Screening only at hemodialysis entry resulted in 88.5% of individuals achieving SVR (compared with only 79.3% in the base case where 25% experience loss to follow-up after each initial linkage to care). Screening every 2 years yielded 93.0% of identified individuals achieving SVR, and screening every year or 6 months resulted in 94.0% and 94.7% achieving SVR, respectively. Although this decreased the number of cirrhotic individuals and liver-related deaths compared with base case, life expectancy and average QALYs over the entire population (with only 2.6% of individuals HCV-infected) increased minimally over the base case results, and ICERs were over the willingness-to-pay threshold for all strategies except screening at hemodialysis entry only ($83,543; Table 4). Simulating higher loss to follow-up, on the other hand (50% to represent general population rates), resulted in larger differences between strategies for the percent of individuals cured (65.8%–88.4%), developing cirrhosis, and dying a liver-related death. ICERs were similar to but slightly lower than those in the base case scenario. Screening at hemodialysis center entry and every 2-year screening yielded ICERs lower than the willingness-to-pay threshold ($79,674 and $124,289, respectively; Table 4).

Table 4.

Main sensitivity analysis results

| Strategy | HCV Infections, % | HCV Infections Identified, Lifetime, % | SVR Achieved (% of Total Infections) | Cirrhosis Cases, % | Liver Related Deaths, % | Remaining Life Expectancy | Undiscounted Cost, $ | Discounted Cost, $ | Discounted QALYs | ICER |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No loss to follow-up (treatment in HD center) | ||||||||||

| No screening | 2.60 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0.687 | 0.184 | 5.2195 | $500,521 | $434,886 | 3.0869 | Ref |

| Screen on entering dialysis center | 2.59 | 94.13 | 88.5 | 0.402 | 0.017 | 5.2279 | $501,437 | $435,650 | 3.0960 | $83,543 |

| Screen every 2 yr | 2.58 | 97.77 | 93.0 | 0.392 | 0.010 | 5.2282 | $501,523 | $435,721 | 3.0964 | $212,728 |

| Screen every yr | 2.57 | 98.45 | 94.0 | 0.390 | 0.010 | 5.2283 | $501,607 | $435,792 | 3.0965 | $686,950 |

| Screen every 6 mo | 2.56 | 98.99 | 94.7 | 0.388 | 0.009 | 5.2276 | $501,731 | $435,898 | 3.0961 | Dominated |

| Higher loss to follow-up (literature-suggested linkage rates of 50%) | ||||||||||

| No screening | 2.60 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0.686 | 0.184 | 5.2199 | $500,559 | $434,911 | 3.0868 | Ref |

| Screen on entering dialysis center | 2.58 | 94.17 | 65.8 | 0.477 | 0.058 | 5.2254 | $501,179 | $435,435 | 3.0934 | $79,674 |

| Screen every 2 yr | 2.56 | 97.84 | 79.8 | 0.437 | 0.030 | 5.2273 | $501,428 | $435,632 | 3.0950 | $124,289 |

| Screen every yr | 2.56 | 98.51 | 84.2 | 0.424 | 0.023 | 5.2274 | $501,511 | $435,704 | 3.0953 | $248,950 |

| Screen every 6 mo | 2.55 | 99.02 | 88.4 | 0.410 | 0.017 | 5.2272 | $501,693 | $435,858 | 3.0955 | $791,958 |

| Halve baseline mortality rates (simulate younger/healthier population or longer lifespan on HD in future) | ||||||||||

| No screening | 2.66 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0.937 | 0.400 | 9.5391 | $916,020 | $747,398 | 5.2973 | Ref |

| Screen on entering dialysis center | 2.63 | 93.26 | 81.1 | 0.468 | 0.066 | 9.5614 | $918,003 | $748,847 | 5.3157 | $78,657 |

| Screen every 2 yr | 2.62 | 98.11 | 92.8 | 0.414 | 0.026 | 9.5620 | $918,148 | $748,951 | 5.3167 | $99,277 |

| Screen every yr | 2.61 | 98.56 | 94.2 | 0.406 | 0.021 | 9.5633 | $918,420 | $749,159 | 5.3176 | $254,265 |

| Screen every 6 mo | 2.60 | 99.02 | 95.3 | 0.399 | 0.018 | 9.5631 | $918,790 | $749,455 | 5.3177 | $2,577,647 |

| HCV RNA testing only (KDIGO/AASLD/IDSA guidelines; varies outbreak duration as well because of smaller window period) | ||||||||||

| No screening | 2.59 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0.686 | 0.184 | 5.2200 | $500,565 | $434,918 | 3.0871 | Ref |

| Screen on entering dialysis center | 2.57 | 94.27 | 79.4 | 0.433 | 0.034 | 5.2269 | $501,410 | $435,637 | 3.0950 | $91,842 |

| Screen every 2 yr | 2.56 | 97.81 | 88.2 | 0.409 | 0.018 | 5.2273 | $501,618 | $435,812 | 3.0956 | $293,513 |

| Screen every yr | 2.55 | 98.50 | 90.5 | 0.402 | 0.014 | 5.2278 | $501,874 | $436,028 | 3.0960 | $521,788 |

| Screen every 6 mo | 2.54 | 99.03 | 92.6 | 0.396 | 0.0120 | 5.2276 | $502,261 | $436,375 | 3.0960 | $10,240,431 |

| Lower HCV antibody test sensitivity (88%) | ||||||||||

| No screening | 2.59 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0.686 | 0.1845 | 5.2202 | $500,588 | $434,934 | 3.0869 | Ref |

| Screen on entering dialysis center | 2.58 | 84.92 | 71.5 | 0.458 | 0.0486 | 5.2267 | $501,301 | $435,535 | 3.0960 | $65,653 |

| Screen every 2 yr | 2.57 | 94.81 | 85.5 | 0.418 | 0.0215 | 5.2273 | $501,434 | $435,642 | 3.0964 | $324,554 |

| Screen every yr | 2.56 | 96.81 | 89.0 | 0.407 | 0.0163 | 5.2273 | $501,512 | $435,713 | 3.0965 | $683,807 |

| Screen every 6 mo | 2.55 | 98.10 | 91.7 | 0.399 | 0.0129 | 5.2279 | $501,760 | $435,920 | 3.0961 | Dominated |

| Lower IDU prevalence (0.25× baseline age- and sex-stratified prevalence) | ||||||||||

| No screening | 2.59 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0.686 | 0.1843 | 5.2203 | $500,594 | $434,935 | 3.0873 | Ref |

| Screen on entering dialysis center | 2.58 | 94.17 | 79.3 | 0.432 | 0.0337 | 5.2273 | $501,368 | $435,590 | 3.0952 | $82,746 |

| Screen every 2 yr | 2.57 | 97.81 | 88.2 | 0.408 | 0.0176 | 5.2278 | $501,483 | $435,683 | 3.0958 | $140,208 |

| Screen every yr | 2.56 | 98.50 | 90.5 | 0.402 | 0.0142 | 5.2274 | $501,520 | $435,722 | 3.0958 | Dominated |

| Screen every 6 mo | 2.55 | 99.01 | 92.5 | 0.395 | 0.0120 | 5.2278 | $501,745 | $435,907 | 3.0961 | $775,958 |

| Higher IDU prevalence (10× baseline age- and sex-stratified prevalence) | ||||||||||

| No screening | 3.23 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0.689 | 0.1832 | 5.1705 | $496,107 | $431,505 | 3.0409 | Ref |

| Screen on entering dialysis center | 3.24 | 75.17 | 63.2 | 0.441 | 0.0351 | 5.1780 | $496,930 | $432,195 | 3.0490 | $85,553 |

| Screen every 2 yr | 3.30 | 89.86 | 80.6 | 0.411 | 0.0175 | 5.1781 | $497,045 | $432,295 | 3.0496 | $164,960 |

| Screen every yr | 3.32 | 92.54 | 84.4 | 0.404 | 0.0143 | 5.1784 | $497,167 | $432,399 | 3.0500 | $289,525 |

| Screen every 6 mo | 3.34 | 95.07 | 87.6 | 0.398 | 0.011 | 5.1783 | $497,353 | $432,564 | 3.0500 | $2,204,716 |

HD, hemodialysis; HCV, hepatitis C virus; SVR, sustained virologic response; QALYs, quality-adjusted life-years; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; RNA, ribonucleic acid; KDIGO, Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes; AASLD, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; IDSA, Infectious Diseases Society of America; IDU, injection drug use.

Decreased Mortality

Halving age- and sex-specific mortality from competing risks of death from ESKD resulted in a near-doubling of remaining life expectancy across all strategies, from 9.54 years in the no screening, no treatment scenario to 9.56 years in all screening strategies (Table 4). However, overall differences between strategies remained similar. The ICER was $78,657 for screening at hemodialysis entry only compared with no screening and $99,277 for screening every 2 years. ICERs for screening every year or every 6 months remained over the willingness-to-pay threshold ($254,265 and $2,577,647, respectively).

RNA Testing Only or Decreased Antibody Sensitivity

Using RNA testing only (instead of starting with HCV antibody testing and reflexing to RNA if positive), even with shortened outbreak duration because of elimination of “window period” infections, yielded relatively small clinical benefits (slightly fewer infections total, slightly higher identification and SVR rates, lower cirrhosis cases and liver-related deaths) and nearly identical QALYs (Table 4). Combined with higher testing costs, ICERs were higher: $91,842 for screening at hemodialysis entry only, $293,513 for every 2-year screening, $521,788 for yearly screening, and $10,240,431 for every 6-month screening. Simulating lower HCV antibody sensitivity (88% versus 95% in the base case) demonstrated higher ICERs for each periodic screening strategy; only screening at hemodialysis entry had an ICER below the willingness-to-pay threshold ($65,653; Table 4). Compared with base case (95%) and 88% antibody sensitivity testing strategies, the RNA testing–only strategies were all dominated or, in other words, yielded an equivalent or smaller number of QALYs (benefits) for higher costs (Supplemental Table 6).

Injection Drug Use Prevalence

Varying initial cohort injection drug use prevalence, to simulate centers with varying HCV acquisition risk outside the center, yielded similar results. Decreasing injection drug use prevalence to one-quarter of that reported in the literature did not vary significantly from base case or change the comparative cost-effectiveness of strategies (Table 4). Increasing injection drug use prevalence to ten times base case age- and sex-stratified values or allowing new initiation of and relapse to injection drug use yielded lower remaining life expectancy and mean QALYs across strategies and more HCV infections in the population (3.2%–3.3% and 4.5%–5%, respectively). More frequent screening strategies identified and cured more infections compared with screening less frequently; however, ICERs for screening at hemodialysis center entry and every 2 years were very similar to base case ICERs (Table 4). Every year screening, although lower than base case estimates, was still well over the willingness-to-pay threshold ($289,525–$307,879) as was the ICER for screening every 6 months ($2.2 million and $361,532, respectively).

Varying Outbreak Prevalence

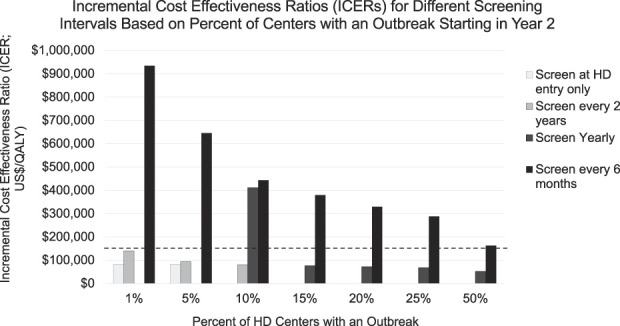

We varied outbreak prevalence among hemodialysis centers to determine at what outbreak threshold more frequent testing would become cost-effective. Once outbreaks occurred in 10% of hemodialysis centers, the screening only at hemodialysis entry strategy was dominated, and the ICER for yearly testing was no longer dominated (Figure 1). With outbreaks in 15% of centers, every 2-year testing was dominated, and the ICER for yearly testing dropped below the $150,000 willingness-to-pay threshold ($76,636) and remained the most cost-effective strategy in the scenarios with outbreaks at 15%–50% of centers. Although every 6-month testing yielded the most clinical benefit in all scenarios, even with outbreaks at 50% of centers, the ICER for every 6-month testing remained just above the $150,000 willingness-to-pay threshold ($163,447).

Figure 1.

ICERs for different screening intervals on the basis of percent of centers with an outbreak starting in year 2. Bars depict ICERs (in 2019 US dollars per QALY) for each screening strategy (screen at hemodialysis center entry only, every 2 years, yearly, or every 6 months) compared with next least expensive, nondominated strategy (initial reference: no screening). Each strategy uses base case parameters, varying prevalence of a simulated outbreak from 1% of centers (per literature estimate) up to an outbreak occurring in 50% of centers. In each case, a single outbreak occurs starting in year 2 of the simulation and lasts 19–60 months on the basis of screening frequency (see Supplemental Table 2). If a strategy is dominated, it does not appear on the graph. Dashed black line denotes $150,000 willingness-to-pay threshold.

Additional Sensitivity Analyses

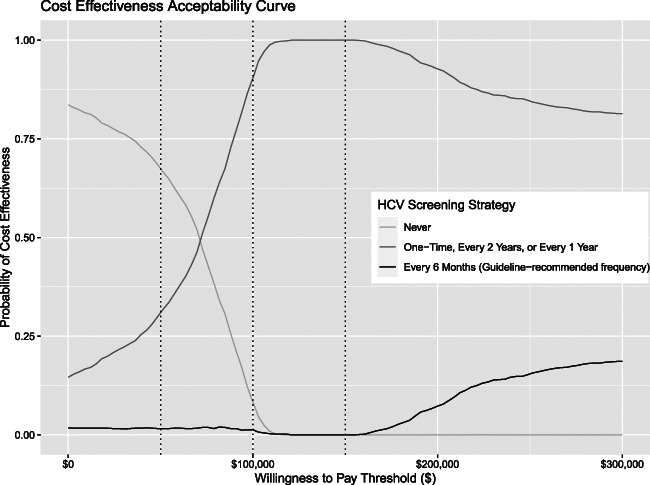

Additional sensitivity analyses varying each key parameter within the literature or expert-determined plausible ranges produced overall similar results to the main analyses (Supplemental Table 7). In one-way sensitivity analyses ranging HCV testing cost, ICERs for testing every 6 months or annually remained >$200,000/QALY or were dominated. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses revealed that results are sensitive to model assumptions, but they confirmed base case conclusions (Supplemental Table 8). At commonly cited US willingness-to-pay thresholds ($50,000–$100,000/QALY), screening once at dialysis entry was the preferred strategy in 20%–50% of simulations (Supplemental Figure 2). At the higher willingness-to-pay thresholds experts recommend using currently ($150,000–$200,000/QALY),38 every 2-year screening became more likely cost-effective. Even with a willingness-to-pay threshold of $300,000, the guideline-recommended every 6-month screening was likely to be cost-effective in <20% of simulations (Figure 2). Finally, comparing differences in health benefits (QALYs) between base case strategies with increasing cohort sizes revealed 95% confidence bands for mean differences that cross zero when comparing annual with every 2-year screening and with every 6-month screening (Supplemental Figure 1D).

Figure 2.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve comparing guideline-recommended screening interval (every 6 months) with other frequencies. Graph represents results of the probabilistic sensitivity analyses, comparing the no HCV screening strategy and the guideline-recommended every 6-month screening with the other three strategies combined (one time, every 2 years, and yearly screening). The x-axis depicts different willingness-to-pay thresholds in US$, with dotted lines indicating $50,000, $100,000, and $150,000, respectively. The y-axis is the probability that a given strategy (or any of a combination of strategies) will be the “winner” at the corresponding willingness-to-pay threshold: the strategy that yields the highest number of QALYs for a cost under the willingness-to-pay threshold. The probability was determined by doing 1000 runs, each with a different set of parameters drawn from the probability distributions noted in Supplemental Table 4 and then calculating the strategy with the highest net monetary benefit (QALYs gained × willingness-to-pay threshold − incremental costs comparing each strategy with the next least expensive, nondominated strategy) at each willingness-to-pay threshold.

Discussion

In this cost-effectiveness analysis of HCV screening in hemodialysis centers, we demonstrate that testing only at hemodialysis initiation is cost-effective, and the addition of follow-up screening every 2 years generated cost estimates also within accepted willingness-to-pay thresholds while yielding important clinical benefits to those diagnosed and cured. Importantly, the current KDIGO and CDC guideline-proposed testing frequency of every 6 months was not cost-effective. These findings remained robust to deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses simulating decreased baseline hemodialysis-related mortality, increased injection drug use prevalence, and HCV treatment in hemodialysis centers. Only with extremely high outbreak rates among hemodialysis centers (15% of centers), did yearly HCV testing drop below the $150,000 willingness-to-pay threshold. Furthermore, in contrast to KDIGO and AASLD/IDSA recommendations, we did not find RNA testing alone to be a cost-effective strategy, even when sensitivity of available HCV antibody assays dropped to 88%.

One of the main cost-effectiveness drivers in this study was dialysis patient survival. Despite improvements in hemodialysis patient clinical care, average life expectancy on hemodialysis remains approximately 5 years. In sensitivity analyses, to determine whether results would change significantly if the average lifespan for individuals on hemodialysis were longer and to simulate a younger, healthier population at certain centers, we halved age- and sex-specific background mortality rates. Although this doubled the current mean dialysis patient survival, the KDIGO-recommended every 6-month testing strategy was still not cost-effective. Furthermore, across all analyses, only one strategy (screening only at dialysis entry with reduced cirrhosis-related mortality) had an ICER <$50,000. The elevated ICERs of repeat screening strategies reflect in part high competing risks of death among hemodialysis patients and short average life expectancy and therefore very small marginal benefits from additional screening; cost savings from curing liver disease are relatively small if someone lives <5 years after cure, with ongoing hemodialysis costs. Averaged out over the entire hemodialysis population, additional screening beyond every 2 years does not result in significantly higher health benefits. Determinations of cost-effectiveness also depend on setting and budget. Although in the United States, $100,000 (the estimated cost of maintaining a patient on hemodialysis for a year) has been the most cited willingness-to-pay threshold, with inflation and rising health care costs, $150,000 may be a more appropriate threshold.37

Intraunit transmission remains an important concern for patients and dialysis providers; avoiding HCV transmission is a major driver of current screening strategies. The published literature suggests this is a relatively uncommon event, but these reports could be an underestimate.43 While possible that the low reported outbreak frequency is due to the frequent screening recommended by KDIGO, in our model, we found that even increasing the outbreak incidence to 4 times that reported in the literature or the prevalence to include outbreaks at 50% of centers failed to render the 6-month testing approach cost-effective.

We also explored the potential role of RNA-based testing in dialysis centers. Even with superior test characteristics and the potential to shorten center-based outbreak duration, unless HCV Ab is very insensitive in ESKD patients, RNA testing likely does not yield sufficiently improved clinical outcomes to be a cost-effective screening method. The current AASLD/IDSA guidelines recommend HCV RNA testing as the preferred assay in hemodialysis patients because of the potential for false negative antibody screening in this population, and KDIGO suggests considering RNA testing.5,8 However, the data most commonly cited to support the poor HCV antibody sensitivity (22%–83%) in hemodialysis patients were collected in the early 1990s using first- and second-generation enzyme immunoassays (EIAs) or recombinant immunoblot assay tests.59,60 More recent data with currently available third-generation HCV EIAs suggest 94%–100% antibody sensitivity in chronic hemodialysis patients, albeit in studies with relatively small sample sizes.61–63 Additional research in this area could help determine when RNA testing is needed; however, from a cost-effectiveness standpoint, even when HCV antibody testing is only 88% sensitive, RNA testing likely does not add sufficient value to be considered cost-effective.

Our study has several strengths. The HEP-CE model is a validated approach to studying HCV screening strategy cost-effectiveness in other high-risk populations.18,64,65 Our results also remained consistent across numerous sensitivity analyses that varied essential model input parameters and simulated scenarios to represent varied hemodialysis populations and future improvements in dialysis and HCV care. We based population characteristics, mortality, and background health care costs on robust USRDS data and recent estimates of HCV prevalence from a large in-center hemodialysis population.

Our work does have limitations. HEP-CE does not model HCV transmission; therefore, our estimates of outbreak likelihood and outbreak HCV incidence were inputs to the simulation rather than outputs that depended directly on the number of infected and unidentified cases. We did, however, use data from previous HCV outbreaks to inform the average number of cases during a hemodialysis center-based outbreak, and we simulated the benefits of HCV testing and treatment on shortening outbreak durations and the total number of people infected during an outbreak event. In addition, published estimates of injection drug use in dialysis patients are imprecise, and our baseline prevalence may have underestimated or overestimated injection drug use frequency among dialysis patients. However, we demonstrated in sensitivity analyses that within reasonable ranges of prevalence, the same overall findings hold true. Similarly, it is possible that some new HCV infections are detected outside the dialysis setting (through transplant evaluations or in primary care), but we expect this is relatively uncommon, and our sensitivity analysis, which included background screening of 20.8% to reflect the proportion of hemodialysis patients undergoing transplant evaluation laboratory workup, revealed similar results to the main analysis (Supplemental Table 7). In addition, we model complex interactions between HCV incidence and screening over time that make parameter estimation uncertain. To explore the impact of that uncertainty, however, we conducted broad deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses that demonstrate that the primary conclusions are robust across feasible parameter values. The multistate utility function for patients on dialysis and with HCV is also not certain. We assumed that each condition independently affects total health state utility. If interactions exist between dialysis and HCV health state utilities, then results could be biased in either direction.

We were unable to fully explore the effect of transplantation in this model; however, our sensitivity analyses applicable to transplant-eligible individuals (lower background mortality, higher background HCV screening) demonstrated consistent overall findings. Finally, this analysis makes many assumptions in its inputs and structure and uses United States–based estimates for most parameters. Although this creates uncertainty and limits generalizability outside the United States, the many sensitivity analyses, which each reveal similar results, support the robustness of these findings and allow estimation of relative cost-effectiveness in settings with varied parameter values.

Cost-effectiveness is not the only consideration for screening programs. Testing and subsequent HCV treatment can significantly improve health and mortality for anyone with undiagnosed disease, decrease transmission, and help ensure appropriate safety and infection control measures occur in hemodialysis centers. This study sought to compare the costs and clinical outcomes of possible HCV testing strategies and frequencies to provide data, which hemodialysis centers and guiding bodies can use to determine ideal screening frequencies in US settings.

We found that testing for HCV at the initiation of hemodialysis provides good economic value, and screening dialysis patients every 2 years can provide additional health benefits. More frequent screening, however, as is currently recommended by most HCV guidelines, provides few additional health benefits and likely is not a cost-effective use of health care resources. These data could inform future guidance for HCV testing recommendations.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

B.P.L. and D.S. are cosenior authors to this work.

See related editorial, “How Frequently Should We Screen for Hepatitis C in US Hemodialysis Centers? Evaluating the Cost-Effectiveness of Different Strategies,” on pages 193–194.

Disclosures

P.P. Reese reports consultancy: VALHealth-identification of patients with CKD and behavior change strategies; ownership interest: various equities, but none specifically health-focused and none directly related to author's research; research funding: co-principal investigator for investigator-initiated and collaborative trials with funding and/or antiviral medication supplied by AbbVie, Gilead, and Merck paid to the University of Pennsylvania to support research on transplantation of HCV-infected organs into uninfected recipients, followed by antiviral treatment; honoraria: salary from the National Kidney Foundation for work as Associate Editor of the American Journal of Kidney Diseases; advisory or leadership role: unpaid ethics consultation to eGenesis, related to patient selection and education, unpaid DSMB service in two trials; and other interests or relationships: legal consultation for private defendants, in a setting where the plaintiffs requiring kidney disease care. D. Sawinski reports ownership interest: CareDx; research funding: National Institutes of Health; advisory or leadership role: American Journal of Kidney Diseases, American Society of Transplantation Board of Directors, Clinical Transplantation, Councilor at Large; and other interests or relationships: UNOS Kidney Committee member and Expert witness testimony. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This study was supported by the Charles A. King Trust postdoctoral research fellowship (to R.L. Epstein), the Providence and Boston Center for AIDS Research under grant P30AI042853, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (P30DA040500 to B.P.L. and 1K01DA052821 to R.L. Epstein), and the Donaghue Foundation Greater Value Portfolio grant (to R.L. Epstein).

Author Contributions

R.L. Epstein, B.P. Linas, and D. Sawinski conceptualized the study; D. Baptiste, B. Buzzee, R.L. Epstein, B.P. Linas, and T. Pramanick were responsible for data curation; B. Buzzee, R.L. Epstein, B.P. Linas, P.P. Reese, and D. Sawinski were responsible for methodology; B. Buzzee and R.L. Epstein were responsible for visualization; R.L. Epstein, T. Pramanick, and D. Sawinski were responsible for investigation; B.P. Linas and R.L. Epstein were responsible for funding acquisition and resources; R.L. Epstein was responsible for project administration; B.P. Linas and D. Sawinski provided supervision; R.L. Epstein, T. Pramanick, and D. Sawinski wrote the original draft; and all authors were responsible for formal analysis and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Data Sharing Statement

All data used in this study are either publicly available online or secondary analysis of deidentified data from previous studies and included in the supplemental materials.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://links.lww.com/JSN/A481.

Supplemental Exhibit 1. HEP-CE model structure.

Supplemental Table 1. CHEERS 2022 reporting checklist.

Supplemental Table 2. Hemodialysis Center hepatitis C virus outbreak literature review and calculations.

Supplemental Table 3. HCV seropositivity and fibrosis stage data, initial cohort.

Supplemental Table 4. Full list of model parameters.

Supplemental Table 5. Breakdown of HCV testing and treatment costs, base case model.

Supplemental Table 6. Comparison of testing using RNA versus antibody testing.

Supplemental Table 7. Additional sensitivity analysis results.

Supplemental Table 8. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis results.

Supplemental Figure 1. Calibration results.

Supplemental Figure 2. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses cost-effectiveness acceptability curve.

References

- 1.Sawinski D, Forde KA, Lo Re V, et al. Mortality and kidney transplantation outcomes among hepatitis C virus-seropositive maintenance dialysis patients: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;73:815-826. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodkin DA, Bieber B, Jadoul M, Martin P, Kanda E, Pisoni RL. Mortality, hospitalization, and quality of life among patients with hepatitis C infection on hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12:287-297. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07940716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;323:970-975. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schillie S. CDC recommendations for hepatitis C screening among adults—United States, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69:1-17. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6902a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jadoul M, Berenguer MC, Doss W, et al. Executive summary of the 2018 KDIGO hepatitis C in CKD Guideline: welcoming advances in evaluation and management. Kidney Int. 2018;94:663-673. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. Accessed June 13, 2022. www.hcvguidelines.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Alter MJ, Lyerla RL, Tokars JI, et al. Recommendations for preventing transmission of infections among chronic hemodialysis patients. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2001;50:1-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Labs Not for the Treatment of ESRD FAQs—OneView Knowledge Base. https://help.oneviewdps.davita.com/article/122-labs-not-for-the-treatment-of-esrd-faqs. Accessed July 21, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finelli L, Miller JT, Tokars JI, Alter MJ, Arduino MJ. National surveillance of dialysis-associated diseases in the United States, 2002. Semin Dial. 2005;18:52-61. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2005.18108.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Somsouk M, Langfield DE, Inadomi JM, Yee HF, Jr. A cost-identification analysis of screening and surveillance of hepatitis C infection in a prospective cohort of dialysis patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:1093-1099. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9966-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Care-Associated Hepatitis B and C Outbreaks (≥2 Cases) Reported to the CDC 2008-2019. Reported to the CDC 2008-2019. 2021. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/outbreaks/healthcarehepoutbreaktable.htm. Accessed December 11, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 12.AASLD-IDSA HCV Guidance Panel. Hepatitis C Guidance 2018 Update: AASLD-IDSA Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(10):1477-1492. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang W, Chen W, Amini A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of tests to detect hepatitis C antibody: a meta-analysis and review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:695. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2773-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linas BP, Morgan JR, Pho MT, et al. Cost effectiveness and cost containment in the era of interferon-free therapies to treat hepatitis C virus genotype 1. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;4:ofw266. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linas BP, Barter DM, Morgan JR, et al. The cost-effectiveness of sofosbuvir-based regimens for treatment of hepatitis C virus genotype 2 or 3 infection. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:619-629. doi: 10.7326/m14-1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Center USRDSC. United States Renal Data System. Accessed 2020. https://usrds.org/. Accessed December 11, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Assoumou SA, Wang J, Nolen S, et al. HCV testing and treatment in a national sample of US federally qualified health centers during the opioid epidemic. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:1477-1483. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05701-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Assoumou SA, Nolen S, Hagan L, et al. Hepatitis C management at federally qualified health centers during the opioid epidemic: a cost-effectiveness study. Am J Med. 2020;133:e641-e658. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.05.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barocas JA, Savinkina A, Lodi S, et al. Projected long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hepatitis C outcomes in the United States: a modelling study. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75:e1112-e1119. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grubbs V, Vittighoff E, Grimes B, Johansen KL. Mortality and illicit drug dependence among hemodialysis patients in the United States: a retrospective cohort analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17:56. doi: 10.1186/s12882-016-0271-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sacks-Davis R, Grebely J, Dore GJ, et al. Hepatitis C virus reinfection and spontaneous clearance of reinfection—the InC3 study. J Infect Dis. 2015;212:1407-1419. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shamshirsaz AA, Kamgar M, Bekheirnia MR, et al. The role of hemodialysis machines dedication in reducing hepatitis C transmission in the dialysis setting in Iran: a multicenter prospective interventional study. BMC Nephrol. 2004;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-5-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bravo Zuñiga JI, Loza Munárriz C, López-Alcalde J. Isolation as a strategy for controlling the transmission of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in haemodialysis units. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;8:CD006420. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006420.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruno S, Zuin M, Crosignani A, et al. Predicting mortality risk in patients with compensated HCV-induced cirrhosis: a long-term prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1147-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Meer AJ, Veldt BJ, Feld JJ, et al. Association between sustained virological response and all-cause mortality among patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced hepatic fibrosis. JAMA. 2012;308:2584-2593. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.144878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patzer RE, McPherson L, Wang Z, et al. Dialysis facility referral and start of evaluation for kidney transplantation among patients treated with dialysis in the Southeastern United States. Am J Transplant. 2020;20:2113-2125. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coyle C, Moorman AC, Bartholomew T, et al. The HCV care continuum: linkage to HCV care and treatment among patients at an urban health network, Philadelphia, PA. Hepatology. 2019;70:476-486. doi: 10.1002/hep.30501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsui JI, Miller CM, Scott JD, Corcorran MA, Dombrowski JC, Glick SN. Hepatitis C continuum of care and utilization of healthcare and harm reduction services among persons who inject drugs in Seattle. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;195:114-120. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.11.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott J, Fagalde M, Baer A, et al. A population-based intervention to improve care cascades of patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatol Commun. 2020;5:387-399. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dupont SC, Fluker S-A, Quairoli KM, et al. Improved hepatitis C cure cascade outcomes among urban baby boomers in the direct-acting antiviral era. Public Health Rep. 2019;135:107-113. doi: 10.1177/0033354919888228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Konerman MA, Thomson M, Gray K, et al. Impact of an electronic health record alert in primary care on increasing hepatitis C screening and curative treatment for baby boomers. Hepatology. 2017;66:1805-1813. doi: 10.1002/hep.29362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reader SW, Kim HS, El-Serag HB, Thrift AP. Persistent challenges in the hepatitis C virus care continuum for patients in a central Texas public health System. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7:ofaa322. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calner P, Sperring H, Ruiz-Mercado G, et al. HCV screening, linkage to care, and treatment patterns at different sites across one academic medical center. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0218388. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McLernon DJ, Dillon J, Donnan PT. Health-state utilities in liver disease: a systematic review. Med Decis Making. 2008;28:582-592. doi: 10.1177/0272989X08315240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pyne JM, French M, McCollister K, Tripathi S, Rapp R, Booth B. Preference-weighted health-related quality of life measures and substance use disorder severity. Addiction. 2008;103:1320-1329. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02153.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wyld M, Morton RL, Hayen A, Howard K, Webster AC. A systematic review and meta-analysis of utility-based quality of life in chronic kidney disease treatments. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neumann PJ, Ganiats TG, Russell LB, Siegel JE, Ganiats TG. Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neumann PJ, Cohen JT, Weinstein MC. Updating cost-effectiveness—the curious resilience of the $50,000-per-QALY threshold. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:796-797. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1405158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schalasta G, Speicher A, Börner A, Enders M. Performance of the new aptima HCV quant Dx assay in comparison to the Cobas TaqMan HCV2 test for use with the high pure system in detection and quantification of hepatitis C virus RNA in plasma or serum. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:1101-1107. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03236-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Department of Health and Human Services. Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule Files 2020. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/medicaremedicare-fee-service-paymentclinicallabfeeschedclinical-laboratory-fee-schedule-files/20clabq2. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notes from the field: hepatitis C outbreak in a dialysis clinic—Tennessee, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64:1386-1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic Kidney Disease Surveillance System—United States. http://www.cdc.gov/ckd. Accessed December 14, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nguyen DB, Bixler D, Patel PR. Transmission of hepatitis C virus in the dialysis setting and strategies for its prevention. Semin Dial. 2019;32:127-134. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (CBHSQ), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and by RTI International. Results From the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. 2017. Available from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2016/NSDUH-DetTabs-2016.htm. Accessed July 23, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Assoumou SA, Tasillo A, Leff JA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of one-time hepatitis C screening strategies among adolescents and young adults in primary care settings. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:376-384. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galai N, Safaeian M, Vlahov D, Bolotin A, Celentano DD. Longitudinal patterns of drug injection behavior in the ALIVE Study Cohort, 1988–2000: description and determinants. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:695-704. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith DJ, Combellick J, Jordan AE, Hagan H. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) disease progression in people who inject drugs (PWID): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26:911-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Erman A, Krahn MD, Hansen T, et al. Estimation of fibrosis progression rates for chronic hepatitis C: a systematic review and meta-analysis update. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e027491. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Program to Eradicate Hep C From Dialysis Patients Finds Early Success|FMCNA, Accessed December 12, 2021. https://fmcna.com/insights/articles/program-to-eradicate-hep-c-from-dialysis-patients-finds-early-success/. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lawitz E, Flisiak R, Abunimeh M, et al. Efficacy and safety of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir in renally impaired patients with chronic HCV infection. Liver Int. 2019;40:1032-1041. doi: 10.1111/liv.14320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reau N, Kwo PY, Rhee S, et al. Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir treatment in liver or kidney transplant patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2018;68:1298-1307. doi: 10.1002/hep.30046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lawitz E, Flisiak R, Abunimeh M, et al. Efficacy and safety of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir in renally impaired patients with chronic HCV infection. Liver Int. 2020;40:1032-1041. doi: 10.1111/liv.14320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gane E, Lawitz E, Pugatch D, et al. Glecaprevir and pibrentasvir in patients with HCV and severe renal impairment. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1448-1455. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Pharmaceutical Prices. https://www.va.gov/oal/business/fss/pharmPrices.asp. Accessed January 21, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davis KL, Mitra D, Medjedovic J, Beam C, Rustgi V. Direct economic burden of chronic hepatitis C virus in a United States managed care population. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:e17-e24. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181e12c09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coffin PO, Sullivan SD. Cost-effectiveness of distributing naloxone to heroin users for lay overdose reversal. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:1-9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-1-201301010-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan V. Preference-based EQ-5D index scores for chronic conditions in the United States. Med Decis Making. 2006;26:410-420. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06290495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.United States Renal Data System. 2021 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD; 2021. Available from https://adr.usrds.org/. Accessed August 4, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sakamoto N, Enomoto N, Marumo F, Sato C. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among long-term hemodialysis patients: detection of hepatitis C virus RNA in plasma. J Med Virol. 1993;39:11-15. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890390104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pereira BJ, Levey AS. Hepatitis C virus infection in dialysis and renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 1997;51:981-999. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Papadopoulos N, Griveas I, Sveroni E, et al. HCV viraemia in anti-HCV-negative haemodialysis patients: do we need HCV RNA detection test? Int J Artif Organs. 2018;41:168-170. doi: 10.1177/0391398817752326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vidales-Braz BM, da Silva NM, Lobato R, et al. Detection of hepatitis C virus in patients with terminal renal disease undergoing dialysis in southern Brazil: prevalence, risk factors, genotypes, and viral load dynamics in hemodialysis patients. Virol J. 2015;12:8. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0238-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Konstantinidou EI, Kontekaki EG, Kefas A, et al. The prevalence of HCV RNA positivity in anti-HCV antibodies-negative hemodialysis patients in Thrace Region. Multicentral study. Germs. 2021;11:52-58. doi: 10.18683/germs.2021.1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Assoumou SA, Tasillo A, Vellozzi C, et al. Cost-effectiveness and budgetary impact of hepatitis C virus testing, treatment, and linkage to care in US prisons. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70:1388-1396. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tasillo A, Eftekhari Yazdi G, Nolen S, et al. Short-term effects and long-term cost-effectiveness of universal hepatitis C testing in prenatal care. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:289-300. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study are either publicly available online or secondary analysis of deidentified data from previous studies and included in the supplemental materials.