Key Points

Genetically induced decay-accelerating factor (DAF) overexpression prevents adriamycin (ADR)-induced focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) in mice.

Pharmacologic inhibition of DAF cleavage reduces complement activation in the glomeruli and albuminuria in murine ADR-induced FSGS.

Inhibition of complement activation represents a valuable therapeutic strategy for FSGS and, potentially, other glomerular diseases.

Keywords: glomerular and tubulointerstitial diseases, adriamycin, basic science, C3, C3aR, CD55 antigens, complement, DAF, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

Introduction

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is a heterogeneous group of disorders in which podocyte injury and loss drive proteinuria and progressive kidney function deterioration.1 Despite significant advances in the field, the molecular mechanisms that govern the disease pathophysiology are still incompletely understood, which severely limits therapeutic options. Current therapies on the basis of generalized immunosuppression are effective in less than half of patients, and persistence of nephrotic syndrome is associated with a relentless progression to kidney failure.2,3 These features make the treatment of primary FSGS a largely unmet medical need.

Because complement deposition in FSGS is not a universal finding, the role of the complement cascade in the pathogenesis of these disorders has been historically overlooked. However, the complement system has been increasingly recognized as a pivotal player in the pathogenesis of other kidney diseases without evidence of antibody deposition, such as C3 glomerulopathies where dysregulated complement activation constitutes the main pathogenic mechanism.4

Evidence in mice indicates that an intact alternative complement pathway is required for the development of glomerular lesions in the adriamycin (ADR)-induced nephropathy model of FSGS.5,6 Case series have described the presence of increased complement split products in the urine of patients with FSGS compared to healthy subjects, and increased urinary levels of C3 and factor B or C3b deposition in the glomeruli have been associated with more severe renal injury or faster disease progression.7,8 Altogether, these findings support the concept that the complement system is involved in the development of podocyte damage and loss in FSGS.

We have recently shown that ADR administration promotes the enzymatic cleavage from podocytes of decay-accelerating factor (DAF), a membrane-bound negative regulator of the complement pathway that locally prevents the formation of surface-bound C3-convertase.9 DAF cleavage and loss initiate complement activation and trigger C3a/C3aR signaling in podocytes, leading to an autocrine IL-1β/IL-1R1 loop that ultimately causes podocyte cytoskeleton rearrangement and podocyte loss.9

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that genetic or pharmacologic inhibition of DAF cleavage on podocytes would prevent the development and progression of ADR-induced FSGS.

Methods

Mice and Procedures

WT C57BL/6J (B6) and BALB/c mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Daf-TM (Rosa26lox-STOP-lox-DAF.TM) transgenic mice were obtained, as previously described.10 In brief, the Daf-TM transgenic gene was constructed using the coding sequence of the mouse Daf1 gene (Cd55) containing the complement regulatory domain, replacing the signal sequence for GPI (Glycosylphosphatidylinositol)-anchor addition with that of the transmembrane helix domain of human tissue factor. Transgene expression driven by the CAG promoter in the Rosa26 locus is regulated by a loxP-flanked transcriptional stop element. To obtain tamoxifen-inducible expression of transgenic Daf in mice lacking endogenous DAF (Daf−/−), we first intercrossed B6 Daf1−/− (Daf−/−) mice11 with UBC-ERT2Cre+ mice (The Jackson Laboratory). Next, we crossed Daf-TM with Daf−/− UBC-ERT2Cre+ (Daf−/−Daf-TMUBC-ERT2) or Daf−/− animals (Daf−/−Daf-TM).

Male mice (aged 8–12 weeks), with a body weight of 20–25 g, were treated with a single retro-orbital injection of ADR (doxorubicin HCl; Ben Venue Laboratories, Bedford, OH) at the dose of 10 mg/kg (BALB/c background) or 20 mg/kg (B6 background). In selected experiments, tamoxifen (2 mg/mouse) was injected intraperitoneally for 4 days 1 week before or 10 days after ADR treatment. WT BALB/c mice were injected intraperitoneally with 5 mg/kg of 5-fluoro-2-indolyl-des-chlorohalopemide (FIPI, Selleckchem.com, Houston, TX) or DMSO (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) as vehicle control three times a week for 5 weeks.

Urine Albumin and Creatinine

Urine spot samples were collected from individual mice before treatment and at weekly intervals until euthanization. Urinary creatinine was quantified using commercial kits from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Urinary albumin was determined using a commercial assay from Bethyl Laboratories (Montgomery, TX), and urinary albumin excretion was expressed as the ratio of urinary albumin to creatinine.

Renal Histology

Mice were deeply anesthetized, and kidneys were harvested and frozen in optimal cutting temperature compound (Tissue-Tek O.C.T., Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) or embedded in paraffin, as previously described.9 Paraffin-embedded kidney sections (3 µm) were stained with periodic acid–Schiff.

Immunofluorescence staining was performed on cryosections (5 µm thick) as per our protocol9 using the following primary antibodies: anti-DAF antibody (rabbit anti-mouse, 1:50; Thermo Fisher), anti-C3b antibody (rat anti-mouse, 1:50; Hycult Biotech, Wayne, PA), and synaptopodin (anti-mouse, 1:5; Fitzgerald, Acton, MA) at 4°C overnight. Sections were then washed and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody for 60 min at room temperature: goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa fluor 594, goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488, and goat anti-rat Alexa Fluor 488 (1:200, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Histologic scoring was performed in a blinded manner, as previously described.12 The extent of glomerular sclerosis was assessed by examining all glomeruli on a kidney cross section and calculating the percentage involved. All animal experiments were performed with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City (New York, NY; IACUC No. 2016-0055).

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables were reported as mean±SE. Comparisons between groups were carried out with unpaired t tests or two-way ANOVA with Šidák test for multiple comparisons, as appropriate. P values <0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Prism, version 7, for Windows (GraphPad Software Inc.).

Results

Genetic Overexpression of Noncleavable DAF Prevents Experimental FSGS and Ameliorates the Severity of Established Disease

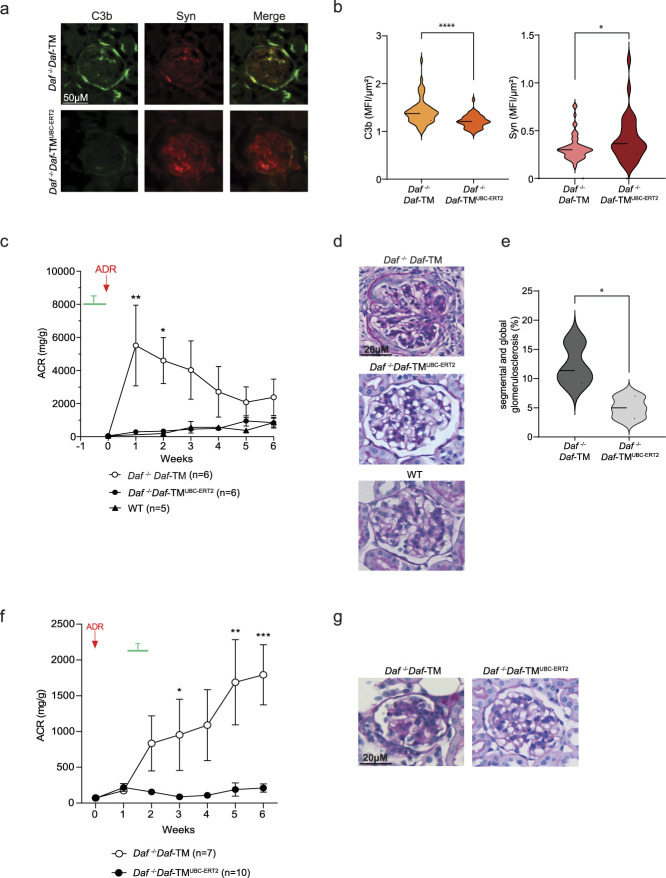

To explore the effects of DAF cleavage inhibition in FSGS, we used a recently generated mouse strain expressing a conditional noncleavable transgenic form of DAF (Daf-TM) on the C57BL/6J background.10 These mice were crossed with Daf−/−UBC-ERT2Cre animals, which lack wild-type DAF expression and present virtually ubiquitous expression of a tamoxifen-inducible Cre-recombinase. The progeny of Daf−/−Daf-TMUBC-ERT2 mice lack DAF expression at baseline, but, on tamoxifen treatment, they overexpress the noncleavable form of DAF.10 We injected tamoxifen 1 week before ADR administration, and DAF overexpression prevented C3b deposition in the glomeruli (Figure 1, A and B). Inhibition of complement activation also protected mice from glomerular injury, as documented by the maintained synaptopodin expression in the glomeruli, lack of glomerulosclerosis (Figure 1, D and E), and the virtual absence of albuminuria (Figure 1C). Control WT C57BL/6J mice were resistant to ADR injury (Figure 1, C and D).12

Figure 1.

DAF expression in podocytes modulates the severity of ADR-associated FSGS. (A) Representative pictures and (B) data quantification of the glomerular expression of C3b and synaptopodin in Daf−/−Daf-TM (n=6), and Daf−/−Daf-TMUBC-ERT2 (n=6) animals at 6 weeks after ADR injection. Scale bars: 50 µm. (C) Urinary ACR over time in Daf−/−Daf-TM (n=6), Daf−/−Daf-TMUBC-ERT2 (n=6), and B6 WT (n=5); (D) representative glomerular pictures (PAS, scale bars: 20 µm) in the same mice; and (E) glomerular sclerosis quantification in Daf−/−Daf-TM (n=6) and Daf−/−Daf-TMUBC-ERT2 (n=6) animals at 6 weeks after ADR injection. Tamoxifen was injected for 4 days, starting 1 week before ADR injection. (F) Urinary ACR over time and (G) glomerular sclerosis (PAS, scale bars: 20 µm) in Daf−/−Daf-TM (n=7) and Daf−/−Daf-TMUBC-ERT2 (n=10) animals at 6 weeks after ADR injection. Tamoxifen was injected starting on day 10 after ADR injection. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired t test for immunofluorescence, and two-way ANOVA with Šidák test for multiple comparisons for ACR. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001.

Next, we tested the hypothesis that DAF overexpression ameliorates severity in already established disease. We induced DAF overexpression by injecting tamoxifen 10 days after ADR administration, a time point when glomerular damage and scarring have already manifested. Delayed tamoxifen administration conferred significant protection from further progression of the nephropathy, as confirmed by low urinary protein excretion and normal histology (Figure 1, F and G).

Collectively, these data indicate that genetically induced overexpression of DAF prevents the onset and reduces the severity of established disease in the ADR murine model of FSGS.

Pharmacologic Inhibition of Phospholipase D–Mediated DAF Cleavage Prevents ADR-Induced FSGS

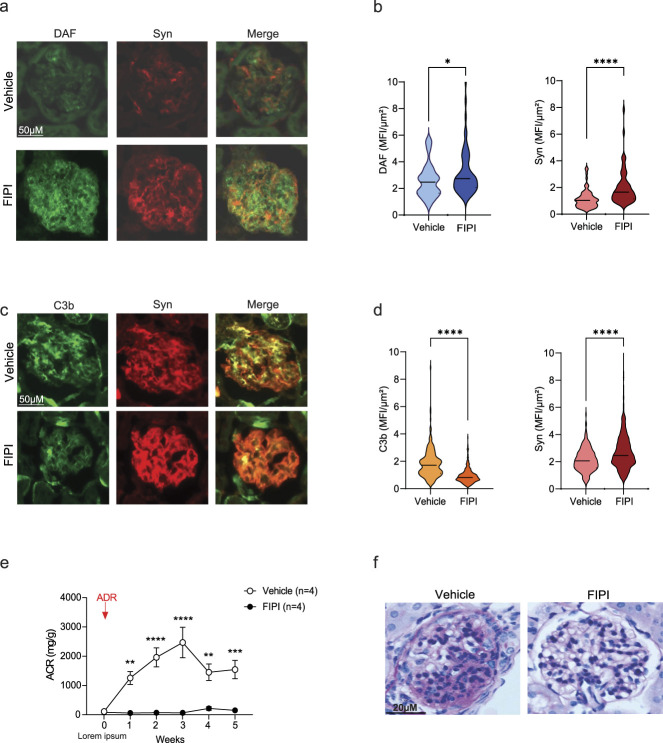

We previously showed that DAF cleavage induced by ADR is mediated by phospholipase D (PLAD).9 Therefore, we tested the effect of a selective PLAD inhibitor, FIPI,13 on ADR-induced FSGS. We treated BALB/c mice (susceptible to the disease) with FIPI starting on the day of ADR administration. Compared with vehicle-treated controls, animals that received FIPI showed an increased expression of DAF in podocytes (Figure 2, A and B) along with a significant reduction of C3b deposition at the glomerular level (Figure 2, C and D). This treatment resulted in preserved synaptopodin expression in the glomeruli (Figure 2, A–D), normal urinary protein excretion (Figure 2E), and normal renal histology at 5 weeks after ADR injection (Figure 2F).

Figure 2.

Pharmacologic inhibition of DAF enzymatic cleavage prevents ADR-induced FSGS in WT BALB/c mice. (A) Representative pictures and (B) data quantification of glomerular expression of DAF and synaptopodin in WT BALB/c mice treated with vehicle control (DMSO) (n=4) or FIPI (n=4) starting from the day of ADR injection. (C) Representative pictures and (D) data quantification of the glomerular expression of C3b and synaptopodin in WT BALB/c mice treated with vehicle control or FIPI starting from the day of ADR injection. Scale bars: 50 µm. (E) Urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) over time and (F) representative light microscopy images (PAS, scale bars: 20 µm) of glomeruli in the same mice. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired t test for immunofluorescence and two-way ANOVA with Šidák test for multiple comparisons for ACR. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001.

Overall, these data demonstrate that PLAD inhibition and the resulting increase of DAF in podocytes can fully prevent the development of ADR-induced FSGS in vivo.

Discussion

We previously showed that unrestrained complement activation resulting from the enzymatic cleavage of DAF on podocytes drives proteinuria and glomerular scarring in the ADR mouse model of FSGS. However, C3aR removal from DAF-deficient mice fully prevented disease development.9

By leveraging a novel mouse model expressing an inducible, noncleavable isoform of DAF, we were able to test for the first time the relevance of DAF expression before and after the induction of experimental FSGS. In addition to the complete prevention of disease development, stable DAF overexpression could also rescue an early but established disease phenotype, an observation with clear potential clinical implications.

Because PLAD targets DAF GPI anchor and promotes the shedding of this molecule from the podocyte cell surface, we decided to use the reversible, PLAD-selective inhibitor FIPI to pharmacologically stabilize DAF expression on podocyte during FSGS induction. Consistent with our hypothesis, FIPI administration prevented PLAD-mediated DAF cleavage, drastically reducing local complement activation at the glomerular level and protecting podocytes from damage. This effect was remarkably associated with the normalization of urinary protein excretion and complete prevention of FSGS lesions, suggesting the potential for clinical translation.

Downstream C3a/C3aR signaling leads to the production of active IL-1β, which mediates podocyte damage.9 This pathway seems to be relevant in humans because glomeruli of patients with FSGS express low levels of DAF, and urinary C3a directly correlated with the entity of proteinuria.9 Consistently, a preliminary report indicates that blockade of IL-1β signaling with the IL-1R-antagonist Anakinra reduces disease severity in FSGS patients resistant to conventional immunosuppression.14 However, activation of IL-1β/IL-1R signaling in podocytes occurs in later phases of the disease and its inhibition provides only partial protection.9,14 Therefore, upstream inhibition of complement activation could provide more effective renoprotection.

The clinical use of FIPI could be challenging because of its relatively short half-life (5.5 hours) and moderate bioavailability.13 Moreover, despite the fact that systemic administration was well-tolerated during the study, we cannot exclude possible long-term off-target effects. Both issues could be addressed with podocyte-specific micro- or nanocarriers, which could increase the compound half-life and allow targeted delivery. We also acknowledge that our studies have been performed in a single FSGS model. More studies using alternative models should be performed to validate our findings.

In summary, this study demonstrates that the inhibition of DAF cleavage on podocytes confers protection from ADR-induced FSGS and that PLAD inhibition in vivo with FIPI could be a feasible option to halt disease progression.

Acknowledgment

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures

J.R. Azzi reports the following: Consultancy: CareDx, Kezar Life Sciences, Moderna Inc., Pirch, Trustech Inc., and Vertex; Research Funding: CareDx., ExosomeDx, and Moderna Inc.; Patents or Royalties: Intellectual Properties and Royalties from Accrue Health Inc.; Intellectual Properties in ExosomeDx; and Advisory or Leadership Role: CareDx: scientific advisory; Trustech: scientific advisory. P. Cravedi reports the following: Consultancy: Calliditas Therapeutics and Chinook Therapeutics; Research Funding: Renel Research Institute; Honoraria: Advisor for Chinook Therapeutics; and Advisory or Leadership Role: Associate Editor for Journal of Nephrology and American Journal of Transplantation. G. La Manna reports the following: Consultancy: Alexion, Astrellas, Eli-Lilly, Hansa-Biopharm, Travere Therapeutics, and Vifor. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant R01 DK119431 awarded to P. Cravedi.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Paolo Cravedi.

Data curation: Sofia Bin, Kelly Budge, Paolo Cravedi.

Formal analysis: Kelly Budge, Paolo Cravedi.

Funding acquisition: Paolo Cravedi.

Investigation: Sofia Bin, Micaela Gentile, Yaseen Khan.

Methodology: Kelly Budge.

Supervision: Paolo Cravedi.

Writing – original draft: Sofia Bin, Paolo Cravedi.

Writing – review & editing: Jamil R. Azzi, Sofia Bin, Kelly Budge, Paolo Cravedi, Micaela Gentile, Yaseen Khan, Gaetano La Manna, Manuel Alfredo Podestà, Luis Sanchez Russo.

Data Sharing Statement

All data are included in the manuscript and/or supporting information.

References

- 1.Kopp JB Anders HJ Susztak K, et al. Podocytopathies. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):68. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0196-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cravedi P, Kopp JB, Remuzzi G. Recent progress in the pathophysiology and treatment of FSGS recurrence. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(2):266–274. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Podesta MA, Ponticelli C. Autoimmunity in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: a long-standing yet elusive association. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020;7:604961. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.604961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith RJH Appel GB Blom AM, et al. C3 glomerulopathy—understanding a rare complement-driven renal disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2019;15(3):129–143. doi: 10.1038/s41581-018-0107-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turnberg D, Lewis M, Moss J, Xu Y, Botto M, Cook HT. Complement activation contributes to both glomerular and tubulointerstitial damage in adriamycin nephropathy in mice. J Immunol. 2006;177(6):4094–4102. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.4094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lenderink AM Liegel K Ljubanovic D, et al. The alternative pathway of complement is activated in the glomeruli and tubulointerstitium of mice with adriamycin nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293(2):F555–F564. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00403.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu J Xie J Zhang X, et al. Serum C3 and renal outcome in patients with primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):4095. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03344-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thurman JM Wong M Renner B, et al. Complement activation in patients with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0136558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angeletti A Cantarelli C Petrosyan A, et al. Loss of decay-accelerating factor triggers podocyte injury and glomerulosclerosis. J Exp Med. 2020;217(9):e20191699. doi: 10.1084/jem.20191699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cumpelik A Heja D Hu Y, et al. Dynamic regulation of B cell complement signaling is integral to germinal center responses. Nat Immunol. 2021;22(6):757–768. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-00926-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heeger PS Lalli PN Lin F, et al. Decay-accelerating factor modulates induction of T cell immunity. J Exp Med. 2005;201(10):1523–1530. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma LJ, Fogo AB. Model of robust induction of glomerulosclerosis in mice: importance of genetic background. Kidney Int. 2003;64(1):350–355. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00058.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stegner D, Thielmann I, Kraft P, Frohman MA, Stoll G, Nieswandt B. Pharmacological inhibition of phospholipase D protects mice from occlusive thrombus formation and ischemic stroke—brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33(9):2212–2217. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angeletti A Magnasco A AntonellaTrivelli, et al. Refractory minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerular sclerosis treated with Anakinra. Kidney Int Rep. 2022;7(1):121–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are included in the manuscript and/or supporting information.