Abstract

Catanionic surfactant vesicles (SVs) composed of sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate (SDBS) and cetyltrimethylammonium tosylate (CTAT) have potential applications as targeted drug delivery systems, vaccine platforms, and diagnostic tools. To facilitate these applications, we evaluated various methods to attach proteins to the surface of SDBS/CTAT vesicles. Acid phosphatase from wheat germ was used as a model protein. Acid phosphatase was successfully conjugated to vesicles enriched with a Triton-X 100 derivative containing an unsaturated ester. Enzymatic activity of acid phosphatase attached to vesicles was assessed using an acid phosphatase assay. Results from the acid phosphatase assay indicated that 15 ± 3% of the attached protein remained functional but the presence of vesicles interferes with the assay. DLS and zeta potential results correlated with the protein functionalization studies. Acid phosphatase-functionalized vesicles had an average diameter of 175 ± 85 nm and an average zeta potential of −61 ± 5 mV in PBS. As a control, vesicles enriched with Triton-X 100 were prepared and analyzed by DLS and zeta potential measurements. Triton X-100 enriched vesicles had an average diameter of 140 ± 67 nm and an average zeta potential of −49 ± 2 mV in PBS. Functionalizing the surface of SVs with proteins may be a key step in developing vesicle-based technologies. For drug delivery, antibodies could be used as targeting molecules; for vaccine formulation, functionalizing the surface with spike proteins may produce novel vaccine platforms.

Graphical Abstract

A novel method to covalently attach proteins to the surface of catanionic surfactant vesicles is described.

Introduction

Catanionic surfactant vesicles (SVs) are soft, spherical materials that spontaneously form in aqueous solution when two surfactants bearing oppositely charged head groups are mixed in the correct ratio at specific concentrations. A variety of cationic and anionic surfactants have been paired to create different vesicle systems.1 We have focused our attention on the sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate (SDBS) and cetyltrimethylammonium tosylate (CTAT) systems first reported by Kaler et. al.2 SDBS and CTAT can be combined in aqueous solutions to create cationic or anionic vesicles. Phase diagrams of SDBS/CTAT SVs have been reported by English and Kaler.3, 4, 5 When SDBS and CTAT are combine with CTAT in excess, CTAT-rich, cationic SVs will form. When SDBS and CTAT are combine and SDBS is in excess, SDBS-rich, anionic SVS will form. For example, anionic vesicles will form when the molar ratio of SDBS to CTAT is 3 to 1 and the total surfactant concentration is less than 3% by weight.3, 4 Anionic SVs have a surfactant bilayer, inner lumen, and negative zeta potentials. We are interested in anionic SDBS/CTAT SVs due to their potential as drug delivery vehicles, vaccine platforms6, systems used to investigate carbohydrate-protein interactions7, 8, 9 and bacterial surface molecules10.

Anionic SVs are attractive for drug delivery and vaccine applications due to their ease of preparation and functionalization, and payload capacity. It has been demonstrated that small molecules can be incorporated into vesicles,3, 11, 12 and vesicles have been functionalized with carbohydrates6, 8, biotin13, folic acid, and peptides. Anionic vesicles are better suited for drug delivery, vaccine, and other therapeutic purposes over cationic vesicles because cationic vesicle-based systems are expected to indiscriminately bind to negatively charged cells throughout the body, hindering their biocompatibility and the specificity of cationic vesicle-based targeted drug delivery systems.

SVs can be functionalized using hydrophobically modified molecules. The hydrophobic moieties become incorporated into the vesicles’ bilayer and anchor the molecules to the vesicles’ surface. Park and Thomas created carbohydrate functionalized vesicles using hydrophobically modified carbohydrates.7, 8 Importantly, the authors demonstrated that lectins can bind to the carbohydrate functionalized surface. Mahle and coworkers also created glycan-functionalized vesicles and enzymatically modified the surface glycans.9 Walker and Zasadzinski created biotin functionalized vesicles using biotin-lipid conjugates.13 Addition of streptavidin to the biotin functionalized vesicles caused the vesicles to aggregate, indicating that streptavidin binds to biotin moieties attached to the surface. Vesicles can also be functionalized via electrostatic interactions. Cationic molecules will associate with the negatively charged surface of anionic surfactant vesicles.3

Creating SV-based drug delivery systems or vaccine platforms may require functionalizing the surface of SVs with proteins. For example, antibodies could be used as targeting moieties in drug delivery systems.14 Others have reported electrostatically binding proteins to catanionic vesicle systems. Letizia et. al. studied the binding of lysozyme to SDS/CTAB and SDS/DDAB vesicles15, while Sciscione et. al. studied the binding of lysozyme to AOT/DODAB vesicles.16 In addition, the interaction of insulin with SDS/CTAB vesicles was reported by Tah and coworkers.17 Proteins passively adsorbed to surfaces can disassociate from the surface or denature and lose their function. In addition, the isoelectric point of proteins dictates their ability to electrostatically associate with SVs at certain pH values. For example, proteins with pI values below 7 may not associate with anionic SVs at pH values above 7.

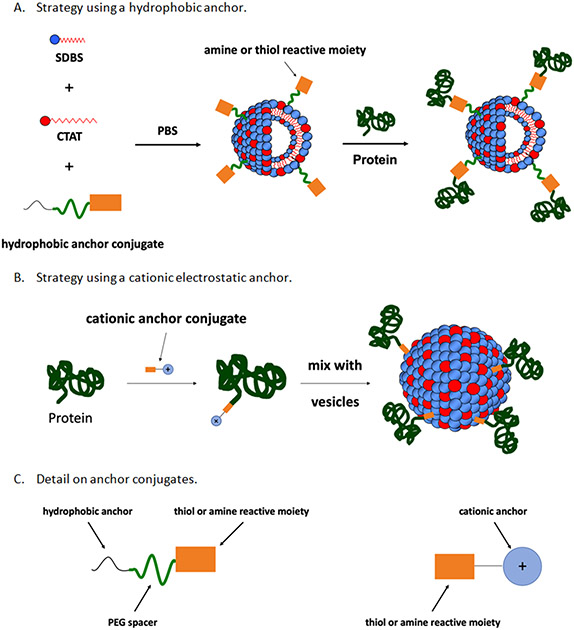

While developing SV-based vaccine platforms, the authors of this article discovered that ovalbumin (pI < 7) would not associate with pre-formed anionic SDBS/CTAT SVs in PBS at pH 7.4. The aim of the work described here was to develop a method to covalently link proteins to the surface of SDBS/CTAT SVs in a way that would enable the protein to maintain its native structure and function. Different bifunctional linkers containing an amine or thiol reactive group and a hydrophobic moiety that can be incorporated into the surfactant bilayer of the vesicles or a cationic moiety that can form strong electrostatic interactions with the vesicles’ anionic surfaces were studied (see Table 1). Acid phosphatase from wheat germ was used a model protein because the native protein does not electrostatically bind to anionic SDBS/CTAT SVs under the conjugation conditions and enzymatic function could be assessed after the proteins were attached to vesicles. The functionalization strategies that were employed are depicted in Figure 1 and were dependent on the type of bifunctional linker that was used. Hydrophobic-based anchors were first incorporated into vesicles and the functionalized vesicles were then mixed with acid phosphatase; electrostatic-based anchors were first conjugated to acid phosphatase and the conjugates were then mixed with pre-formed vesicles. After evaluating the different methods and anchors, it was determined that binding protein to vesicles enriched with Triton X-100 derivative, 1, was found to be the best strategy.

Table 1:

Bifunctional linkers examined in this study

| Entry | Structure | Name | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

DSPE-PEG-Maleimide | hydrophobic |

| 2 |

|

Esterified Triton X-100, 1 | hydrophobic |

| 3 |

|

Rhodamine B isothiocyanate | electrostatic |

| 4 |

|

Glycidyltrimethylammonium | electrostatic |

Hydrophobic anchors contain a hydrophobic moiety that is expected to incorporate into the SV bilayer. Electrostatic anchors contain a cationic group that is expected to associate with the negatively charged SV surface.

Figure 1: Schematic representation of surface functionalization strategies.

In method A, a bifunctional linker containing a hydrophobic anchor is incorporated into vesicles and then the functionalized vesicles react with protein. In method B, an electrostatic anchor is conjugated to a protein and the protein conjugate is mixed with pre-formed vesicles.

Experimental

Materials and Instrumentation

Sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate (SDBS), cetyltrimethylammonium p-toluenesulfonate (CTAT), acid phosphatase from wheat germ, 4-nitrophenyl phosphate disodium salt hexahydrate, Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP), acryloyl chloride, glycidyltrimethylammonium chloride, rhodamine B isothiocyanate, and Sepharose CL-2B were purchased from Millipore Sigma. 4-(dimethylamino)pryridine (DMAP) was purchased from Shweizerhall, Inc and Triton X-100 was obtained from EM Industries, Inc. DSPE-PEG(2000) Maleimide, 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[maleimide(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (ammonium salt), was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. Corning® phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was obtained from VWR and Pierce® BCA Protein Assay Kits were obtained from ThermoFisher Scientific. CTAT was recrystallized from ethanol using acetone as an antisolvent. Dichloromethane and triethylamine were dried over molecular sieves prior to use. All other chemicals were used as received from the manufacturer.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) and zeta potential measurements were conducted on a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS with Zetasizer Nano software at 25 °C. Folded capillary zeta cells, purchased from Malvern Panalytical, were used for DLS and zeta potential analyses. The scattering angle for DLS measurements was 173 degrees. Samples were suspended in PBS (1X, pH = 7) for DLS and zeta potential measurements. Absorbance measurements were obtained on a BioTek Synergy H1 microwell plate reader or a Cary UV-Vis instrument. Mass spectra were obtained via thin layer chromatography-mass spectrometry (ESI) using J. T. Baker silica TLC plates (Baker-flex; silica gel IB2-F) and an Advion expression compact_mass spectrometer; sample solutions were spotted on a TLC plate and analyzed in positive mode with a mixture of methanol, water, and formic acid (ratio: 80:20:0.1, respectively) as solvent.

Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) Assay

The enhanced test tube protocol was used. Five standard solutions of acid phosphatase in PBS were prepared with concentrations of 200, 100, 50, 25, and 12.5 μg/mL. PBS was used as a blank. Standard and sample solutions (100 μL) were added to separate one-dram vials. BCA reagents A and B were combined in a 50:1 ratio respectively to create the working reagent. The working reagent (2.0 mL) was added to each vial in 1mL portions. Vials were placed into a water bath heated to 60 degrees Celsius for 30 minutes. The vials were removed and placed in an ice bath. Once cool, the vials were removed from ice and allowed to come to room temperature (21 °C). Absorbance was then measured at 562 nm. A standard curve was created and the concentration of phosphatase in the samples was determined.

Citric Acid-Phosphatase Assay

4-Nitrophenyl phosphate disodium hexahydrate (2.0mg) was added to each of three 1-dram vials labeled positive, negative, and sample. 800 μL of PBS was added to the negative control (blank sample) vial, 800 μL of a 50 μg/mL solution of phosphatase in PBS was added to the positive control vial, and 800 μL of a sample was added to the sample vial. To each vial, Citric acid (66 μL, 10mg citric acid/ mL PBS) was added to reach pH of 4.0. The solutions were placed in a water bath heated to 37 degrees Celsius for 1 hour. An aliquot of each sample (100 μL) was added to a vial with DI water (100 μL) and NaOH (100 μL, 0.1M) and diluted to 3 mL with DI water. A blank was prepared by combining PBS (100 μL), NaOH (100 μL) and Citric acid (10 μL, 10 mg citric acid/ mL PBS) and diluting to 2 mL. Absorbance was then measured at 410 nm. Absorbance values of negative control samples were subtracted from positive control and sample absorbance values.

Vesicle Purification by Size Exclusion Chromatography

A gravity filtration protocol was followed. PD-10 columns were packed with pre-swollen Sepharose CL-2B or Sephadex G100 gel to a height of 5.0-5.5 cm. 1.0 mL vesicle samples were added to the top of the column and allowed to fully enter the gel bed. 1.0 mL aliquots of eluent (PBS) were added to the column and 1.0 mL fractions were collected. Vesicles eluted from the column in fractions 3.1 to 5.0 mL.

Preparation of Esterified Triton X-100 Conjugate

All Glassware was oven dried (110 °C) for at least 24 hours before use. Using a spatula, Triton X-100 (196 mg, 0.327 mmol) and DMAP (8 mg, 0.07 mmol) were added to a small oven-dried vial with a stir bar. The vial was then placed under nitrogen atmosphere. Dry DCM (1.0 mL) was added to dissolve the Triton X-100 and DMAP. Dry triethylamine (188 μL, 1.35 mmol) was acryloyl chloride (107 μL, 1.32 mmol) were added quickly. The reaction mixture stirred at room temperature (21 °C) for 1 hour. The reaction mixture was then dried in vacuo using a rotary evaporator and then analyzed by thin layer chromatography-mass spectrometry (ESI).

Bare Vesicles Mixed with Acid Phosphatase

SDBS (175 mg), CTAT (75 mg) and PBS (9.9 mL) were mixed in a 20 mL vial. The solution stirred for about 1.5 hours. 1.0 mL of the vesicle sample was purified via SEC (Sepharose CL-2B) with PBS as eluent, and fractions 3.1-5.0 mL were collected. 1.0 mL of a 1% SDBS solution was placed into the column before the vesicle sample.

Acid Phosphatase (20 mg) and TCEP (1.0 mg) were dissolved in PBS (2.0 mL). 20 μL of this solution was added to the purified vesicles (1.0 mL) and the mixture stirred for 18 hours at room temperature (21 °C). 1.0 mL of the vesicle sample was then purified via SEC (Sepharose CL-2B) with PBS as the eluent. Vesicles eluted in fractions 3.1-5.0 mL.

Maleimide Vesicles Mixed with Acid Phosphatase

PBS (1.0 mL) was added to a vial containing DSPE-PEG-Maleimide (2.0 mg), SDBS (175 mg) and CTAT (75 mg). The mixture stirred for 2 minutes, then PBS (8.9 mL) was added. The solution stirred for about 1.5 hours. 1.0 mL of the vesicle sample was purified via SEC (Sepharose CL-2B) with PBS as eluent, and fractions 3.1-5.0 mL were collected. 1.0 mL of a 1% SDBS solution was placed into the column before the vesicle sample.

Acid Phosphatase (20 mg) and TCEP (1.0 mg) were dissolved in PBS (2.0 mL). 20 μL of this solution was added to the purified vesicles (1.0 mL) and the mixture stirred for 18 hours at room temperature (21 °C). 1.0 mL of the vesicle sample was then purified via SEC (Sepharose CL-2B) with PBS as the eluent. Vesicles eluted in fractions 3.1-5.0 mL.

Esterified Triton X-100 Vesicles Mixed with Acid Phosphatase

Esterified triton X-100 reaction mixture (50 mg) was added to a vial and dissolved in PBS (2.0 mL). This solution was then transferred to a vial containing SDBS (175 mg) and CTAT (75 mg). PBS (7.9 mL) was then added. The solution stirred for about 1.5 hours. 1.0 mL of the vesicle sample was purified via SEC (Sepharose CL-2B) with PBS as eluent, and fractions 3.1-5.0 mL were collected. 1.0 mL of a 1% SDBS solution was loaded on to the column before the vesicle sample.

Acid Phosphatase (20 mg) and TCEP (1.0 mg) were dissolved in PBS (2.0 mL) and 20 μL of this solution was added to an aliquot of purified esterified Triton X-100 vesicles (1.0 mL). The mixture stirred for 18 hours at room temperature (21 °C). 1.0 mL of the vesicle sample was then purified via SEC (Sepharose CL-2B) with PBS as the eluent. Vesicles eluted in fractions 3.1-5.0 mL.

Triton X-100 Vesicles Mixed with Acid Phosphatase

Triton X-100 (50 mg) was added to a vial and dissolved in PBS (2.0 mL). This solution was then transferred to a vial containing SDBS (175 mg) and CTAT (75 mg). PBS (7.9 mL) was then added. The solution stirred for about 1.5 hours. 1.0 mL of the vesicle sample was purified via SEC (Sepharose CL-2B) with PBS as eluent, and fractions 3.1-5.0 mL were collected. 1.0 mL of a 1% SDBS solution was loaded on to the column before the vesicle sample.

Acid Phosphatase (20 mg) and TCEP (1.0 mg) were dissolved in PBS (2.0 mL) and 20 μL of this solution acid was added to an aliquot of purified esterified Triton X-100 vesicles (1.0 mL). The mixture stirred for 18 hours at room temperature (21 °C). 1.0 mL of the vesicle sample was then purified via SEC (Sepharose CL-2B) with PBS as the eluent. Vesicles eluted in fractions 3.1-5.0 mL.

Quaternary Ammonium-Labeled Acid Phosphatase Mixed with Bare Vesicles

Acid Phosphatase (8.0 mg) was added to a sodium bicarbonate solution (2.0 mL, 0.1M, pH=9). While stirring, glycidyltrimethylammonium chloride (100 μL) was added slowly to the protein solution. The mixture stirred for 18 hours at room temperature (21 °C). The phosphatase-conjugate solution was then purified through a G-100 SEC column using PBS as the eluent and fractions 2.5-4.0 mL were collected. Phosphatase standards were prepared at concentrations of 1, 0.5, 0.25, and 0.125 mg/mL. Absorbance was then measured at 280 nm. A standard curve was made, and the concentration of the phosphatase conjugate in solution was determined.

2.5% Bare vesicles were purified through CL-2B. Before the sample was applied to the column, 1.0 mL of a 1% SDBS solution was added to the column. To a vial, purified Bare vesicles (1.0 mL) were added. While stirring, PBS (450 μL) was added slowly to the side of the vial. The solution stirred for 10 minutes. The G-100 purified conjugate-phosphatase solution (220 μL, 1.1 mg phosphatase/mL PBS) was added slowly to the side of the vial. The solution stirred for 18 hours at room temperature (21 °C). 1.0 mL was then purified via SEC (Sepharose CL-2B) with PBS as the eluent. Vesicles eluted in fractions 3.1-5.0 mL.

Rhadamine B-Labeled Acid Phosphatase Mixed with Bare Vesicles

Rhodamine B isothiocyanate (2.0 mg) was dissolved in DMSO (2.0 mL). This solution (100 μL) was added to a solution of phosphatase (8.0 mg) in 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate (2.0 mL, pH=9) slowly to the side of the vial while stirring and allowed to incubate in the refrigerator (10 °C) for 18 hours. Ammonium chloride (5.4 mg) was added to the solution. The solution was stirred for 2 minutes, then placed in the fridge for 2 hours. The phosphatase-conjugate solution was then purified through a G-100 SEC column using PBS as the eluent and fractions 2.5-4.0 mL were collected. Phosphatase standards were prepared at concentrations of 1, 0.5, 0.25, and 0.125 mg/mL. Absorbance was then measured at 280 nm. A standard curve was made, and the concentration of the phosphatase conjugate in solution was determined.

2.5% Bare vesicles were purified through CL-2B. Before the sample was applied to the column, 1.0 mL of a 1% SDBS solution was added to the column. To a vial, purified Bare vesicles (1.0 mL) were added. While stirring, PBS (480 μL) was added slowly to the side of the vial. The solution stirred for 10 minutes. The G-100 purified phosphatase-conjugate solution (230 μL, 1.0 mg phosphatase/mL PBS) was added slowly to the side of the vial. The solution stirred for 18 hours at room temperature (21 °C). 1.0 mL was then purified via SEC (Sepharose CL-2B) with PBS as the eluent. Vesicles eluted in fractions 3.1-5.0 mL.

Results and Discussion

Protein Functionalization Studies

The goal of this work was to develop methods to covalently link proteins to the surface of catanionic surfactant vesicles (SVs). The methods should be robust yet gentle enough so that attached proteins maintain their three-dimensional structure and overall function. Acid phosphatase was selected as a model protein because enzymatic activity could be assessed after the proteins were conjugated to SVs. In addition, acid phosphatase proteins were experimentally determined to not electrostatically bind to anionic vesicles under the conditions used for protein-vesicle conjugations (PBS, pH 7.4). Bare, purified vesicles were stirred with acid phosphatase in PBS and subsequently purified by SEC and analyzed for protein content. Two trials were performed and acid phosphatase was not detected in either sample. This result was expected because the majority of acid phosphatase proteins have calculated isoelectric points below 7.0.18 Protein-SV conjugations were carried out in PBS at pH 7.4 and the overall negative charge on the proteins at pH 7.4 will prevent acid phosphatase protein from interacting with anionic vesicles. Therefore, under the conjugation conditions, attachment of acid phosphatase to SVs is expected to be via a bifunctional linker.

Protein concentration in SV samples could not be measured from tryptophan and tyrosine residue absorbances at 280 nm due to interfering absorbance from SDBS. Thus, the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (enhanced protocol) was used to detect and quantify protein within vesicle samples. The assay was selected due to its ease of use and compatibility with surfactants and PBS buffer. The manufacturer of the BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific) lists the working range for the enhanced protocol as 5 – 250 μg/mL with a detection limit of 5 μg/mL. We found that external calibration curves of acid phosphatase were linear (R2 values >0.99) between 12.5 and 200 μg/mL and estimated the detection limit to be 13 μg/mL (refer to supporting information for detail on LOD calculations). 19, 20 Though the estimated LOD is higher than the LOD listed by the manufacturer, the estimated detection limit was the lowest point in the working range of our assay, which is consistent with the manufacture’s protocol.

SDBS/CTAT SVs form in mixtures of total surfactant concentrations of 1% by weight7 and up to 3% by weight.3 Adding proteins to initial vesicle-formation procedures would likely cause proteins to denature due to the high concentrations of anionic and cationic surfactants. Therefore, our initial approach was to prepare SVs that were functionalized with a protein reactive moiety, purify the crude SVs via size exclusion chromatography to remove excess surfactant and anchor conjugate, and then mix the purified SVs with acid phosphatase. The resulting mixtures were then purified again by SEC to separate SVs from unbound protein. After purification, SV fractions were pooled and analyzed for protein content using the enhanced protocol for the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. The acid phosphatase assay was used to gauge the percentage of protein attached to vesicles that retained their native form and function. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was used to assess vesicle size and zeta potential measurements were conducted to measure vesicle surface charge.

The ability to separate vesicles from excess surfactant and ligand is not only key to this study, but it is also required for their biocompatibility. Others have shown that SEC can be used to separate SDBS/CTAT vesicles from small molecules. 6, 7, 11, 12 Most notably, Richard et. al. used Sephadex G-100 to separate vesicle-based vaccine formulations from excess SDBS and tosylate ions.6 SEC purified vesicles used as control samples did not exhibit acute toxicity—indicating that very little, if any, free SDBS was in the purified samples. For our studies, we needed a SEC gel capable of separating protein from vesicles and found that Sepharose CL-2B was a suitable choice. We used a variety of analyses (gravimetric, 1H-NMR, TLC, and TLC-MS) to assess the ability of Sepharose CL-2B to separate vesicles from excess surfactant (see supplemental material). The results from all of our analyses show that excess SDBS and Triton X-100, as well at tosylate ions, are successfully separated from vesicles during Sepharose CL-2B SEC purification. Vesicles elute from the SEC column first while smaller micelles and molecules elute in later fractions.

Catanionic vesicles are similar to phospholipid-based liposomes. SVs have a surfactant bilayer while liposomes have a phospholipid bilayer. Vabbilisetty and Sun investigated different anchoring lipids to attach molecules to the surface of liposomal formulations.21 The authors used cholesterol and hydrophobically modified phosphatidylethanolamine (DSPE) derivatives to create glycol-functionalized liposomes. We began our work by studying similar commercially available lipid anchors. Vesicles enriched with DSPE-PEG-maleimide conjugates (entry 1 in Table 1) were initially investigated. However, BCA assay results from multiple trials indicated that no or very little acid phosphatase protein bound to the maleimide-functionalized vesicles with the concentration of protein in the vesicle samples below the limit of detection.

The failure of the DSPE-PEG-maleimide conjugate lead us to pursue other hydrophobic anchors. Previous studies in our lab had revealed that the nonionic surfactant, Triton-X 100, can be incorporated into SDBS/CTAT SVs. The structure of Triton-X 100 is shown in Figure 2. We were interested in Triton X-100 because it contains a hydrophobic moiety, a PEG unit, and a terminal alcohol that can be transformed into an alpha-beta unsaturated ester. The ester could then react with amine or thiol groups in proteins. To prepare the esterified Triton X-100 derivative, 1, Triton X-100 was reacted with acryloyl chloride following a method reported by Oppolzer and coworkers (Figure 2).22 Analysis of the reaction mixture by thin layer chromatography-mass spectrometry indicates that the conversion to the ester was successful (see supplemental information). However, the reaction did not go to completion, as unmodified Triton X-100 was still present in the reaction mixture, but the amount of esterified conjugate in the mixture was enough to carry the mixture forward into vesicle formulations. Incorporating the reaction mixture into vesicle formulations would produce vesicles functionalized with both PEG and the esterified conjugate.

Figure 2:

Schematic representation of Triton X-100 esterification.

The esterified Triton X-100 reaction mixture was incorporated into SVs, and after purification via SEC, the vesicle sample was analyzed via TLC-MS. Peaks consistent with esterified Triton X-100 were observed in the ESI mass spectrum, and indicated that the vesicles were enriched with the esterified conjugate. Acid phosphatase was added to the esterified-Triton X-100 vesicle sample. The mixture was purified to separate free protein from protein-functionalized SVs and SV fractions were analyzed by BCA assay. BCA analyses indicated that acid phosphatase protein bound to the esterified Triton X-100 enriched SVs. Over six trials, acid phosphatase functionalized SV samples (prepared by mixing esterified Triton X-100 enriched vesicles with acid phosphatase) contained an average of 31 ± 9 μg/mL of protein. Encouraged by these results, we conducted multiple control experiments. Triton X-100 (non-esterified) was incorporated in to vesicles and the Triton X-100 enriched vesicle samples were purified, mixed with acid phosphatase, and purified again (following the same procedure as esterified Triton X-100 enriched SVs). However, BCA assay results indicate acid phosphatase protein does not bind to Triton X-100 enriched SVs. In addition, esterified Triton X-100 vesicles that were not mixed with acid phosphatase did not produce a positive BCA assay result—demonstrating that esterified Triton X-100 vesicle samples do not cause a false positive result in the BCA assay. The BCA assay results from different vesicle formulations are summarized in Table 2. From these results, we concluded that acid phosphatase protein binds to esterified Triton X-100 enriched vesicles.

Table 2:

BCA protein assay results of various surfactant vesicle (SV) samples

| Entry | Sample | Protein Concentration, μg/mL |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bare SVs mixed with acid phosphatase | Below LOD |

| 2 | Maleimide functionalized SVs mixed with acid phosphatase | Below LOD |

| 3 | Triton X-100 enriched SVs mixed with acid phosphatase | Below LOD |

| 4 | Esterified Triton X-100 enriched SVSs | Below LOD |

| 5 | Esterified Triton X-100 enriched SVs mixed with acid phosphatase* | 31 ± 9 |

| 6 | Bare SVs mixed with rhodamine-B labelled acid phosphatase | Below LOD |

| 7 | Bare SVs mixed with trimethyl ammonium labelled acid phosphatase | Below LOD |

The limit of detection for the assay is 13 μg/mL. See supporting information for calculated protein concentrations for each vesicle formulation.

Also referred to as acid phosphatase functionalized SVs (AP SVs) in the text, figures, and subsequent tables.

SDBS/CTAT SV formulations containing Triton X-100 conjugates, and DSPE-PEG-maleimide, were limited by the amount of the hydrophobic anchors that can be added to the formulations. The weight percent of Triton X-100 and esterified Triton X-100 conjugate, 1, in their respective formulations is 0.5%. SVs formed in mixtures containing 0.7% w/w Triton X-100 are very turbid and polydisperse, indicating that SV formation is disrupted, or vesicles aggregate, at higher Triton X-100 concentrations. In fact, SDBS/CTAT SVs do not form in mixtures containing Triton X-100 in concentrations of 1% by weight. SDBS/CTAT SVs have very low tolerance for the DSPE-PEG-maleimide conjugate as well. The concentration of the DSPE-PEG-maleimide conjugate in vesicle formulations was only 0.02% by weight. Increasing the concentration to 0.04% resulted in very turbid samples.

The percent of Triton X-100 molecules incorporated into SVs was determined by analyzing size exclusion chromatography fractions of Triton X-100 enriched vesicles using UV-Vis spectroscopy. 47% of Triton X-100 that is added to SV formulations is incorporated into SVs. Esterified Triton X-100 SV samples were purified twice; once to remove excess surfactant before protein conjugation, and then again after protein conjugation to separate protein functionalized vesicles from free, unbound protein. Tondre and coworkers showed that entrapped glucose releases from vesicles.12 To assess if Triton X-100 conjugates leach from SVs during the protein functionalization step, purified Triton x-100 enriched SVs were stirred for 18 hours and then purified a second time by SEC. The resulting fractions were then analyzed for Triton X-100. UV-Vis analysis indicated that 90% of Triton X-100 is retained in SVs during the protein functionalization step and after subsequent SEC purification. Results from Tondre and Kaler indicate that surfactants and other small molecules in solution with vesicles are in equilibrium with molecules incorporated into vesicles.5, 12 Triton X-100 molecules are relatively water soluble and remain in solution after leaching from vesicles. Released Triton X-100 molecules free in solution are expected to be in equilibrium with Triton X-100 molecules incorporated into vesicles.

Danoff and Lioi showed that cationic dyes electrostatically bind to the negatively charged surface of anionic SDBS/CTAT SVs.3, 11 Based on these reports, we explored the potential of electrostatic-based anchors--Rhodamine B-isothiocyanate and Glycidyltrimethylammonium chloride (Table 1, entry 3 and 4) We hypothesized that these cationic molecules could be conjugated to protein and then electrostatically anchor the protein to the surface of anionic SVs. Acid phosphatase was labeled with the conjugates following standard labelling protocol and purified by SEC. Labeled acid phosphatase was then stirred with bare, purified SVs. Samples were then purified by SEC and analyzed by BCA assay. The BCA assay results indicated that the labeled proteins did not bind to the anionic SVs. The inability to anchor proteins using the cationic moieties may be due to the size of the cationic anchors in comparison to the larger proteins. Once conjugated to proteins, the cationic anchors do not associate with the surface of SVs because the anchor moieties are a small part of a larger system with an overall negative charge that is repelled from anionic SVs in a similar manner as non-labelled acid phosphatase protein.

Acid Phosphatase Assay Results

As mentioned above, the goal of this project was to develop a method to covalently link proteins to the surface of anionic SDBS/CTAT SVs and to have the attached protein retain their native form and function. Acid phosphatase was chosen as a model protein so that the activity of the proteins could be evaluated after they were attached to the vesicles. A standard colorimetric assay using 4-nitrophenyl phosphate as the substrate was used. The percent of protein that remained functional after conjugation was calculated based on acid phosphatase standard solutions prepared in PBS. Protein-functionalized vesicles (prepared by conjugating acid phosphatase protein to esterified Triton X-100 vesicles) were analyzed. The average of four trials indicated that 15 ± 3% of the attached protein remained functional. However, further studies indicated that the presence of vesicles interferes with the acid phosphatase assay. Figure 3 depicts the results of a single trial of an acid phosphatase assay. The acid phosphatase functionalized SVs (AP vesicles) that were analyzed had an acid phosphatase concentration of 30 μg/mL (determined by BCA assay). The other samples analyzed in that trial also contained acid phosphatase at 30 μg/mL. Enzymatic activity was diminished in the presence of bare SVs and greatly diminished in the presence of Triton-X 100 enriched SVs and in the acid phosphatase functionalized SV sample. Notably, protein-functionalized vesicles gave similar results to a mixture of acid phosphatase and Triton X-100 enriched vesicles. Additional control experiments were conducted on mixtures of bare vesicles and acid phosphatase, and Triton X-100 enriched vesicles and acid phosphatase. Standard solutions of acid phosphatase that did not contain vesicles had higher enzymatic activity. The difference in enzymatic activity between standard solutions of acid phosphatase and mixtures of Triton X-100 enriched SVs with acid phosphatase was significant at a 99% confidence level.

Figure 3: Acid phosphatase assay results of acid phosphatase functionalized vesicles and other acid phosphatase samples.

Sample key: AP control = acid phosphatase control sample; BV with AP = bare vesicles mixed with acid phosphatase; TXV with AP: Triton X-100 enriched vesicles mixed with acid phosphatase; AP SVs: acid phosphatase functionalized vesicles. Results from a single trial of different acid phosphatase samples. Acid phosphatase functionalized vesicles demonstrated diminished enzymatic activity compared to vesicle formulations in which acid phosphatase was mixed with vesicle solutions but had similar activity to acid phosphatase that was mixed with Triton X-100 enriched vesicles. The acid phosphatase concentration in each sample is 30 μg/mL. Negative control samples (samples containing the substrate but no acid phosphatase) were used to normalize absorbance values.

The reduced phosphatase activity in samples that contain SVs indicates that the enzymes and/or substrate molecules are interacting with the surface of vesicles in situ and inhibit the enzymes from reacting with the substrate. The acid phosphatase assay is conducted at a pH of 4—a pH at which acid phosphatase proteins will be predominately cationic. Therefore, under the assay conditions, acid phosphatase is expected to interact with the anionic vesicles. The substantial reduction in activity in the presence of Triton X-100 vesicles is attributed to polyethylene glycol units on the vesicle surface. It is known that polyethylene glycols interact with proteins.23 The PEG units on the surface of Triton-X-100 functionalized vesicles may facilitate hydrophobic interactions between acid phosphatase and the vesicles surface that would not occur between proteins and bare vesicles. Additionally, the substrate may associate more strongly with PEG-functionalized vesicles (through hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions) than with bare vesicles. Increased interactions between vesicles and acid phosphatase, and vesicles and the substrate, would likely reduce or interfere with substrate-protein interactions, and result in reduced enzymatic activity.

On average, enzymatic activity was reduced to 30% in the presence of Triton X-100 enriched SVs and the enzymatic activity of acid phosphatase conjugated to SVs was reduced to 15%. Others have reported reduction of enzymatic activity after conjugation.24, 25 For example, Rodríguez-Martínez and coworkers reported a significant reduction of enzymatic activity of α-Chymotrypsin after modifying the protein with PEG. Under the conditions of the assay, acid phosphatase on acid phosphatase-functionalized SVs may be interacting with the surface of the vesicle to which they are attached or other vesicles. Alternatively, some proteins conjugated to the surface could be attached in an orientation that blocks an active site or may become denatured after conjugation. Though our analyses demonstrate that free surfactant is separated from vesicles during SEC purification, a small amount of Triton X-100 leaches from vesicles after purification. Therefore, the reduced enzymatic activity observed in solutions containing vesicles could also be attributed to protein or substrate molecules interacting with free surfactant in solution.

Dynamic Light Scattering Analyses

SV samples were analyzed by dynamic light scattering (DLS) to measure the average diameters and size distributions of vesicles. Average values from cumulant analyses and distribution by intensity analyses are summarized in Table 3. Foremost, the DLS data indicates that vesicles are present in all samples and shows that vesicles formed under the various formulation conditions. Bare SVs and Triton X-100 enriched vesicles had similar average diameters to previously reported SDBS/CTAT vesicle formulations.5, 7, 11 Size analyses for all vesicle samples indicate a single population with relatively broad size distributions as indicated by their cumulant analysis polydispersity index (PDI) values and size distribution by intensity standard deviation (standard deviation values are in parentheses in Table 3). The relatively wide size distribution indicates that the mean and standard deviation of the intensity distribution analyses are best suited for vesicle size analysis and characterization. The mean diameter of bare SDBS/CTAT vesicles was 138 ± 68 nm and the average diameter of Triton X-100 enriched vesicles was 140 ± 67 nm. Two samples of vesicles functionalized with acid phosphatase protein (prepared from esterified Triton X-100 enriched vesicles) were analyzed and both samples had larger overall diameters than the bare and Triton X-100 enriched samples. The average and standard deviation of the two samples (six total measurements from two samples, see entries 4 and 5 in Table 3) was 175 ± 85 nm. Triton X-100 enriched vesicles that were mixed with acid phosphatase, purified, and did not contain protein after purification (as indicated by BCA assay) had an average diameter of 115 ± 40 nm. DLS data correlates well with BCA analyses and indicates that protein is attached to the surfaced of vesicles functionalized with esterified Triton X-100 conjugate, 1. Figure 4 shows an overlay of size distributions from one DLS measurement of Triton X-100 enriched vesicles and one DLS measurement of acid phosphatase functionalized vesicles. The overall increase in size is attributed to proteins on the surface of vesicles increasing the hydrodynamic radii of the vesicles.

Table 3:

Dynamic light scattering data

| Entry | Sample | Cumulant Analysis Z-Ave, nm | PdI | Distribution Analysis Mean Diameter, nm (stdev) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bare SVs | 120 | 0.242 | 138 (68) |

| 2 | Triton X-100 enriched SVs | 116 | 0.179 | 140 (67) |

| 3 | TX SVs x AP | 102 | 0.102 | 115 (40) |

| 4 | AP SVs —Trial 1 | 142 | 0.279 | 169 (74) |

| 5 | AP SVs—Trial 2 | 141 | 0.180 | 180 (97) |

Sample key: TX SVs x AP = Triton X-100 enriched vesicles that were mixed with acid phosphatase and then purified by SEC; AP SVs = acid phosphatase functionalized vesicles (prepared by mixing esterified Triton X-100 enriched vesicles with acid phosphatase and then purified by SEC)

Samples were analyzed on a Malvern Zetasizer ZS. Values are averages of three measurements. Size measurements were measured by intensity with a scattering angle of 173. Values in parentheses are pooled standard deviation of three measurements.

Figure 4: DLS size distributions of Triton X-100 enriched vesicles and acid phosphatase functionalized vesicles.

Sample key: TX SVs: Triton X-100 enriched vesicles; AP vesicles: acid phosphatase functionalized vesicles (prepared by mixing acid phosphatase with esterified Triton X-100 enriched vesicles and then purifying by SEC). Data is from a single, representative DLS measurement from each sample. The increase in size is attributed to proteins attached to the surface.

Notably, micelles were not detected in the DLS size distribution analysis of any SV sample. Triton X-100 micelles have reported diameters of 11 nm in pure water and 13 nm in 0.5 M aqueous NaCl, while SDBS micelles have reported diameters of 6 nm in 0.1 M aqueous NaCl and 10 nm in 0.15 M aqueous NaCl (the concentration of NaCl in 1X PBS is 0.137 M).26, 27 The mono-nodal size distributions with the absence of peaks consistent with micelles in DLS size distributions correlates with our finding that SEC purification successfully separates excess surfactant and conjugate molecules from SVs and only a small amount of surfactants leach out of vesicles after purification. Free surfactant and acid phosphatase-Triton X −100 conjugates are likely in solution at concentrations below their critical micelle concentration and in equilibrium with molecules incorporated into SVs.

Based on an average diameter of 140 nm and the results of encapsulation studies, the concentration of vesicles in purified acid phosphatase functionalized vesicle samples is estimated to be 3.2 x 1012 vesicles/mL (see supporting information for detail on the encapsulation studies and vesicle concentration calculations). Acid phosphatase functionalized vesicle samples had an average acid phosphatase concentration of 31 μg/mL. Thus, the average number of acid phosphatase molecules per vesicle is approximately 1.0 x 102. The theoretical maximum number of acid phosphatase molecules in a close-packed monolayer on a vesicle with a diameter of 140 nm is 7.3 x 102. The theoretical maximum value for a close-packed monolayer was estimated using a model28 where acid phosphatase molecules are spherical with 5.2 nm radii (based on a structure of purple acid phosphatase obtained from the Protein Data Bank in Europe—see supporting information). Using this model, protein covers 14% of the acid phosphatase functionalized vesicles’ surfaces.

Zeta Potential Measurements

The zeta potential of vesicle samples was measured using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS instrument. The results are summarized in Table 4. All samples were analyzed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 1X) with a pH of 7.4 and in triplicate. Bare vesicles had an average zeta potential of −55.3 ± 4.0 mV while Triton X-100 enriched vesicles had an average zeta potential of −49.0 ± 2.0 mV. The decrease in the zeta potential of Triton X-100 enriched vesicles is attributed to Triton X-100 molecules passivating the surface of the particles. Triton X-100 enriched vesicles that were mixed with acid phosphatase, purified, and had no protein associated with the surface of the vesicles, had zeta potentials of −44.7 ± 3.0 mV. Two protein-functionalized vesicle samples (prepared from esterified Triton X-100 enriched vesicles) were analyzed and had a combined average zeta potential of −61.1 ± 5.4 mV. As mentioned above, acid phosphatase proteins are expected to be predominately anionic at a pH of 7.4. The difference in zeta potential between Triton X-100 enriched vesicles and protein functionalized vesicles provides further evidence that the conjugation of proteins to the surface of esterified Triton X-100 vesicles was successful.

Table 4:

Dynamic light scattering, zeta potential measurement, and protein analysis data

| Entry | Sample | Distribution Analysis Mean Diameter, nm (stdev) | Zeta Potential, mV (stdev) | Protein Concentration, μg/mL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bare SVs | 138 (68) | −55.3 (4.0) | NA |

| 2 | Triton X-100 enriched SVs | 140 (67) | −49.0 (2.0) | NA |

| 3 | TX SVs x AP | 115 (40) | −44.7 (3.0) | Below LOD |

| 4 | AP SVs —Trial 1 | 169 (74) | −56.7 (1.0) | 30 |

| 5 | AP SVs—Trial 2 | 180 (97) | −65.5 (3.7) | 20 |

Sample key: TX SVs x AP = Triton X-100 enriched vesicles that were mixed with acid phosphatase and then purified by SEC; AP vesicles = acid phosphatase functionalized vesicles (prepared by mixing esterified Triton X-100 enriched vesicles with acid phosphatase).

Samples were analyzed on a Malvern Zetasizer ZS. Mean diameter and zeta potential values are averages of three measurements. Associated standard deviation is shown in parentheses. Samples were purified via SEC before analysis with PBS (1X, pH = 7.4) as the eluent.

The modest reduction in the zeta potential of Triton X-100 enriched SVs in comparison to bare SVs coincides with our finding that only 47% of Triton X-100 that is added to the SV formulations is incorporated into vesicles. As noted above, vesicle formulations cannot tolerate high concentrations of Triton X-100 and DSPE conjugates. The long-term stability of catanionic vesicles is partially attributed to the repulsive interactions between vesicles in solution.5 Vesicles more highly enriched with Triton X-100 and DSPE-PEG conjugates may be unstable due to the PEG moieties passivating the surface to a point where coulombic repulsion between vesicles is reduced—resulting in vesicle aggregation. The DSPE-PEG-maleimide conjugate has a longer PEG unit than Triton X-100 derivatives. Though longer PEG moieties are expected to reduce protein-surface interactions better than short PEG units, longer PEG units are also expected to passivate the surface of SVs more efficiently than short PEG moieties and may be why the DSPE conjugate can only be used at low concentrations.

Conclusions

The goal of the work presented here was to find a method to covalently attach proteins to the surface of anionic SDBS/CTAT SVs. Results from BCA assays, and analysis by DLS and zeta potential measurements indicate that acid phosphatase proteins were successfully conjugated to the surface of SVs enriched with esterified Triton X-100 derivative, 1. The derivative was synthesized in a single step from readily available starting materials and worked better than a commercially available DSPE-PEG-maleimide conjugate and cationic anchors. The enzymatic activity of protein attached to the surface of vesicles was analyzed using an acid phosphatase assay. The enzymatic activity of protein attached to vesicles was reduced to 15%. However, studies revealed that the presence of SVs interferers with the assay. Enzymatic activity of acid phosphatase was reduced to 30% in the presence of Triton X-100 enriched vesicles. When compared to mixtures of acid phosphatase and Triton X-100 enriched SVs, enzymatic activity of proteins attached to vesicles was reduced to 50%. Attaching proteins to the surface of vesicles could be a key step to providing systems with versatile applications and this work may lead to SV-based drug delivery systems, diagnostic tools, vaccine platforms, or other SV-based technologies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

M.H. is grateful to Dr. Jeffrey Halpern and Shawn Banker for their assistance with acquiring DLS and zeta potential measurements at the University of New Hampshire. M.H. also thanks Dr. Mary Kate Donais for her assistance with statistical analyses and Dr. Elizabeth Greguske for helping secure funding for this project.

This research was supported by New Hampshire-INBRE through an Institutional Development Award (IDeA), P20GM103506, from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH, and COBRE grant, NIH P20 GM113131.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

There are no conflicts to declare.

References

- (1).Tondre C; Caillet C Properties of the amphiphilic films in mixed cationic/anionic vesicles: a comprehensive view from a literature analysis. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci 2001, 93 (1-3), 115–134, 10.1016/S0001-8686(00)00081-6. DOI: 10.1016/S0001-8686(00)00081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Kaler EW; Murthy AK; Rodriguez BE; Zasadzinski JA Spontaneous vesicle formation in aqueous mixtures of single-tailed surfactants. Science 1989, 245 (4924), 1371–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Lioi SB; Wang X; Islam MR; Danoff EJ; English DS Catanionic surfactant vesicles for electrostatic molecular sequestration and separation. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2009, 11 (41), 9315–9325, 10.1039/B908523H. DOI: 10.1039/B908523H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Koehler RD; Raghavan SR; Kaler EW Microstructure and Dynamics of Wormlike Micellar Solutions Formed by Mixing Cationic and Anionic Surfactants. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2000, 104 (47), 11035–11044. DOI: 10.1021/jp0018899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Kaler EW; Herrington KL; Murthy AK; Zasadzinski JAN Phase behavior and structures of mixtures of anionic and cationic surfactants. The Journal of Physical Chemistry 1992, 96 (16), 6698–6707. DOI: 10.1021/j100195a033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Richard K; Mann BJ; Stocker L; Barry EM; Qin A; Cole LE; Hurley MT; Ernst RK; Michalek SM; Stein DC; et al. Novel catanionic surfactant vesicle vaccines protect against Francisella tularensis LVS and confer significant partial protection against F. tularensis Schu S4 strain. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2014, 21 (2), 212–226. DOI: 10.1128/CVI.00738-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Park J; Rader LH; Thomas GB; Danoff EJ; English DS; DeShong P Carbohydrate-functionalized catanionic surfactant vesicles: preparation and lectin-binding studies. Soft Matter 2008, 4 (9), 1916–1921, 10.1039/b806059b. DOI: 10.1039/b806059b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Thomas GB; Rader LH; Park J; Abezgauz L; Danino D; DeShong P; English DS Carbohydrate Modified Catanionic Vesicles: Probing Multivalent Binding at the Bilayer Interface. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2009, 131 (15), 5471–5477. DOI: 10.1021/ja8076439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Mahle A; Dashaputre N; DeShong P; Stein DC Catanionic Surfactant Vesicles as a New Platform for probing Glycan-Protein Interactions. Adv Funct Mater 2018, 28 (13). DOI: 10.1002/adfm.201706215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Stein DC; L HS; Powell AE; Kebede S; Watts D; Williams E; Soto N; Dhabaria A; Fenselau C; Ganapati S; et al. Extraction of Membrane Components from Neisseria gonorrhoeae Using Catanionic Surfactant Vesicles: A New Approach for the Study of Bacterial Surface Molecules. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12 (9). DOI: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12090787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Danoff EJ; Wang X; Tung S-H; Sinkov NA; Kemme AM; Raghavan SR; English DS Surfactant Vesicles for High-Efficiency Capture and Separation of Charged Organic Solutes. Langmuir 2007, 23 (17), 8965–8971. DOI: 10.1021/la070215n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Fischer A; Hebrant M; Tondre C Glucose encapsulation in catanionic vesicles and kinetic study of the entrapment/release processes in the sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate/cetyltrimethylammonium tosylate/water system. J Colloid Interface Sci 2002, 248 (1), 163–168. DOI: 10.1006/jcis.2001.8187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Walker SA; Zasadzinski JA Electrostatic Control of Spontaneous Vesicle Aggregation. Langmuir 1997, 13 (19), 5076–5081, 10.1021/LA970094Z. DOI: 10.1021/LA970094Z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Alley SC; Okeley NM; Senter PD Antibody-drug conjugates: Targeted drug delivery for cancer. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2010, 14 (4), 529–537, 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.06.170. DOI: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.06.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Letizia C; Andreozzi P; Scipioni A; La Mesa C; Bonincontro A; Spigone E Protein Binding onto Surfactant-Based Synthetic Vesicles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111 (4), 898–908, 10.1021/jp0646067. DOI: 10.1021/jp0646067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Sciscione F; Pucci C; La Mesa C Binding of a protein or a small polyelectrolyte onto synthetic vesicles. Langmuir 2014, 30 (10), 2810–2819. DOI: 10.1021/la500199w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Tah B; Pal P; Talapatra GB Interaction of insulin with SDS/CTAB catanionic Vesicles. Journal of Luminescence, 2014; Vol. 145, pp 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Moorman VR; Brayton AM Identification of individual components of a commercial wheat germ acid phosphatase preparation. PLoS One 2021, 16 (3), e0248717. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Harvey D Analytical Chemistry 2.1. 2016. http://dpuadweb.depauw.edu/harvey_web/eTextProject/version_2.1.html (accessed 2022 June 21). [Google Scholar]

- (20).Agency, U. S. E. P. Definition and Procedure for the Determination of the Method Detection Limit, Revision 2. 2016. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-12/documents/mdl-procedure_rev2_12-13-2016.pdf (accessed 2022 June 21).

- (21).Vabbilisetty P; Sun X-L Liposome surface functionalization based on different anchoring lipids via Staudinger ligation. Org. Biomol. Chem 2014, 12 (8), 1237–1244, 10.1039/c3ob41721b. DOI: 10.1039/c3ob41721b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Oppolzer W; Kurth M; Reichlin D; Chapuis C; Mohnhaupt M; Moffatt F Asymmetric induction of Diels-Alder reactions of acrylates derived from chiral sec-alcohols. Preliminary communication. Helv. Chim. Acta 1981, 64 (8), 2802–2807, 10.1002/hlca.19810640841. DOI: 10.1002/hlca.19810640841. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Arakawa T; Timasheff SN Mechanism of poly(ethylene glycol) interaction with proteins. Biochemistry 1985, 24 (24), 6756–6762. DOI: 10.1021/bi00345a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Rodriguez-Martinez JA; Rivera-Rivera I; Sola RJ; Griebenow K Enzymatic activity and thermal stability of PEG-alpha-chymotrypsin conjugates. Biotechnol Lett 2009, 31 (6), 883–887. DOI: 10.1007/s10529-009-9947-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Morgenstern J; Baumann P; Brunner C; Hubbuch J Effect of PEG molecular weight and PEGylation degree on the physical stability of PEGylated lysozyme. Int J Pharm 2017, 519 (1-2), 408–417. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Thakkar K; Patel V; Ray D; Pal H; Aswal VK; Bahadur P Interaction of imidazolium based ionic liquids with Triton X-100 micelles: investigating the role of the counter ion and chain length. RSC Advances 2016, 6 (43), 36314–36326, 10.1039/C6RA03086F. DOI: 10.1039/C6RA03086F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Cheng DCH; Gulari E Micellization and intermicellar interactions in aqueous sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate solutions. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 1982, 90 (2), 410–423. DOI: 10.1016/0021-9797(82)90308-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kozlowski R; Ragupathi A; Dyer RB Characterizing the Surface Coverage of Protein–Gold Nanoparticle Bioconjugates. Bioconjugate Chemistry 2018, 29 (8), 2691–2700. DOI: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.