Keywords: dialysis, COVID-19 pandemic, health care providers, hemodialysis, qualitative study, semidirected interviews

Abstract

Key Points

Hemodialysis workers' well-being and work were affected by the COVID-19 pandemics.

Effective communication strategies and taking into account psychological distress are ways to mitigate the challenges faced by health care workers.

Background

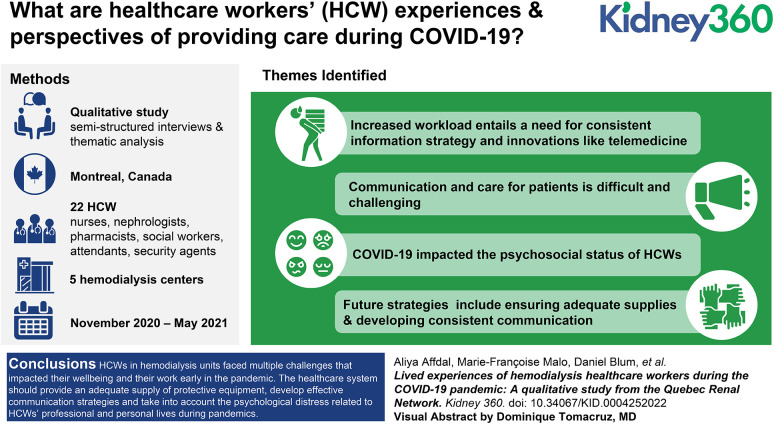

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted health systems and created numerous challenges in hospitals worldwide for patients and health care workers (HCWs). Hemodialysis centers are at risk of COVID-19 outbreaks given the difficulty of maintaining social distancing and the fact that hemodialysis patients are at higher risk of being infected with COVID-19. During the COVID-19 pandemic, HCWs have had to face many challenges and stressors. Our study was designed to gain HCWs' perspectives on their experiences of the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in hemodialysis units.

Methods

Semistructured interviews were conducted with 22 HCWs (nurses, nephrologists, pharmacists, social workers, patient attendants, and security agents) working in five hemodialysis centers in Montreal, between November 2020 and May 2021. The content of the interviews was analyzed using thematic analysis.

Results

Four themes were identified during the interviews. The first was the impact of COVID-19 on work organization, regarding which participants reported an increased workload, a need for a consistent information strategy, and positive innovations such as telemedicine. The second theme was challenges associated with communicating and caring for dialysis patients during the pandemic. The third theme was psychological distress experienced by hemodialysis staff and the psychosocial impact of COVID-19 on their personal lives. The fourth theme was recommendations made by participants for future public health emergencies, such as maintaining public health measures, ensuring an adequate supply of protective equipment, and developing a consistent communication strategy.

Conclusions

During the first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, HCWs working in hemodialysis units faced multiple challenges that affected their well-being and their work. To minimize challenges for HCWs in hemodialysis during a future pandemic, the health care system should provide an adequate supply of protective equipment, develop effective communication strategies, and take into account the psychological distress related to HCWs' professional and personal lives.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted health systems and created numerous challenges in hospitals worldwide for patients and health care workers (HCWs). In the Canadian province of Quebec, a public health emergency and a general lockdown were declared on March 13, 2020. During the first wave of the pandemic, Quebec was considered a hot spot, the city of Montreal being particularly affected, with very high rates of community transmission.1 During this period, approximately 14% of HCWs working in Montreal had a positive serology for COVID-19.2

Hemodialysis units are particularly at risk of COVID-19 outbreaks and infection among patients. COVID-19 infection is associated with a high mortality rate among hemodialysis patients (approximately 20%–30%).3–5 This could be explained by the difficulty of maintaining social distancing between patients and health care providers, the fact that the hemodialysis population is at higher risk of COVID-19 infection because of their comorbid conditions, and that numerous patients attending hemodialysis units live in nursing homes where COVID-19 infection can spread rapidly.5–7

In the Canadian province of Quebec, hemodialysis units are all publicly funded. Patients are cared for by nurses and nephrologists. Most dialysis facilities are in-center, but there are satellite units attached to hospitals. Nursing home patients receive their dialysis treatment either in in-center dialysis units or satellite units.

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous protective measures were quickly implemented in dialysis units, such as symptom assessments before entering the treatment area, isolating suspected or confirmed cases, sanitizing, social distancing, and mandatory mask wearing.8 Infection rates approached 25% in patients receiving in-center hemodialysis in Montreal.5,9

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, HCWs, including dialysis staff, have been at risk of increased psychological stress and distress given their exposure to death, lack of appropriate equipment, moral injury, increased workload, and the risks of COVID-19 infection.10,11 The objective of our study, which is part of a larger study documenting the impact of COVID-19 on hemodialysis clinics in Quebec,12–14 was to gather HCWs' experiences and perspectives of providing care during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. A better understanding of the scope and magnitude of the challenges faced by hemodialysis staff during the pandemic would help to inform interventions during future public health emergencies and could also provide strategies to mitigate stress for dialysis staff and improve care for patients.

Methods

This exploratory study relied on semistructured interviews of hemodialysis staff. We used the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research checklist.15 Recruitment and interviews were carried out between November 2020 and May 2021, during the second and third wave of COVID-19 in Quebec. Convenience and purposive sampling16 were used to recruit HCWs from five hemodialysis centers in the Montreal area, Quebec, Canada. Purposive sampling consisted of recruiting participants with varying sociodemographic characteristics (age, years of practice, sex, type of work, ethnic origin, etc.) who will provide information-rich data to better understand the topic studied.16,17 HCWs were recruited by a local coordinator at each site and then referred to the research team to schedule an interview.

Interviews were conducted in English or French over the phone or videoconference by two different interviewers who do not work in dialysis units, had no relationship with the participants, and have experience in qualitative methodology (A.A. and F.B.). The interviews lasted between 20 and 57 minutes and were recorded and transcribed. The Centre Hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal Research Ethics Board approved the study (CE 20.065, MP-02–2021-9006), and all participants provided informed consent. The interview transcripts were sent to all participants for approval. Themes covered during the interviews were outlined in an interview guide with open-ended questions that are summarized in Table 1. The interview guide was developed by the research team and modified as new topics emerged from the interviews.16,18

Table 1.

Themes addressed during the qualitative interviews

| Theme |

|---|

| Overall experience of providing care to hemodialysis patients during the pandemic |

| Fears and concerns related to the pandemic |

| Psychosocial impacts of the pandemic |

| Recommendations for future interventions in pandemic contexts |

We used a qualitative description approach to describe the experiences of hemodialysis staff during the COVID-19 pandemic.19,20 The goal of this pragmatic approach was to stay close to the data and provide a comprehensive summary of the topic studied,20 using thematic analysis.16,18 The latest version of NVivo (QSR International) software was used to facilitate the analysis. Before coding the verbatims, A.A. and F.B. (who had previous experience in qualitative analysis) created the initial coding frame on the basis of the interview grid and a review of the literature. New codes were added to the coding frame on the basis of the interview content. The research team met frequently to discuss the coding frame and data analysis. AA coded the interviews, and no new codes were created after the 18th interview. The number of participants allowed for data saturation.21 An independent researcher (M.-F.M.) with experience in qualitative methods coded 30% of the raw data with the rate of coding agreement assessed at 89%, and disagreements were discussed. Coded quotes were then organized by themes and subthemes.

Results

Participants' Characteristics

During the study period, 53 HCWs were approached to participate, and 27 agreed. Three HCWs declined before the interview because of time constraints, and two could not be interviewed because of conflicting schedules. Twenty-two HCWs from five hemodialysis centers all located in Montreal in the province of Quebec were interviewed. Four of these five hemodialysis centers were associated with a teaching hospital. Fifteen HCWs were female and seven were male, with a mean age of 49 years. Six participants were nephrologists, and five were nurses. They had been working in nephrology for an average of 13 years. Table 2 summarizes the HCWs' characteristics.

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants

| Characteristic | n=22 (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 15 (68.2) |

| Male | 7 (31.8) |

| Language | |

| French | 14 (63.6) |

| English | 8 (36.4) |

| Age (yr) | 48.8 ± 9.7 Ranging from 23 to 64 |

| Ethnic group | |

| White | 18 (81.8) |

| Indigenous | 1 (4.5) |

| Others | 3 (13.6) |

| Type of job | |

| Nephrologist | 6 (27.3) |

| Nurse | 5 (22.7) |

| Social worker | 3 (13.6) |

| Nutritionist | 2 (9.1) |

| Patient attendant | 2 (9.1) |

| Others | 4 (18.2) |

| Tested for COVID-19 | 18 (81.2) |

| Number of times tested for COVID-19 (ranging from 1 to 10) | 3.33 ± 2.1 |

| Years of experience in nephrology (yr) | 12.5 ± 10.2 Ranging from 1 to 34 |

Qualitative Interviews

Respondents highlighted a range of issues that they considered important in relation to the impacts of the pandemic in hemodialysis and in their work. These issues can be grouped around four main themes: (1) impacts of COVID-19 on work organization, (2) challenges associated with communicating with and caring for hemodialysis patients, (3) work-related psychological distress and the psychosocial impact of COVID-19 on personal life, and (4) recommendations for future pandemic contexts.

1. Impacts of COVID-19 on Work Organization

In the dialysis units, where one or two nephrologists and nurses are assigned to the care of patients, COVID-19 and preventive measures were associated with a worsening of working conditions. Some reported changes in their schedules and working location, increased workload, and increased caution to avoid being infected. In addition, isolating infected patients on a dedicated floor, although useful, increased the workload of HCWs (Table 3).

“Well, it had a big impact in the sense that it brought the need to reorganize many working methods, it fragilized nursing teams, and it had an impact on work organization even within our team of physicians. It changed the face of our unit, and we did have several deaths.” Female 05, nurse

Table 3.

Consequences of COVID-19 on work organization

| Themes and Interview Excerpts | N=22 |

|---|---|

|

Increased workload “Definitely we had work overload and COVID infections. We always had the bases covered, but it just intensified our work.” Female 10, patient attendant “Well, at the beginning, we had to take stock of everything: we did a test, and after that had to check the result (…) It was always me that had to look at contacts, you get a call from the STM (public transport company), he was in contact with such and such a patient who is positive. Then I had to look at the result after so many days, and after that do another test at the end. It was five days, 12 days, so then I had to check the results. When I saw that patients were symptomatic, right, okay, I had to make a note of that on a list, and I had to go back and see whether, is the patient positive? Is he not positive? All that, all that management, it was very, it was a big workload on top of what we already had.” Female 09, nurse “After working a 16-hour shift one day and then coming back in the next morning, you know? I imagine it's affecting the care in some ways.” Male 02, nurse |

5 |

|

Information provided to HCWs on COVID-19 “During the first wave, certainly the information was extremely volatile, we were getting between 20 and 30 different bulletins per day with information that changed over the course of the day. Internally we often felt that we were receiving information too late, so that when we received a bulletin, it was something that had already gone cold, that dated from a few hours before. (…)” Female 13, nurse “I think the nurse manager was doing the very best she could, you know? Contacting everybody with email updates, even at night from home, you know? I mean not everything was well known, but she would keep us up to date on, you know, what is being considered, what the government might be thinking, what might be happening in the next few days. Obviously, a lot of the information was vague, but it wasn't because, you know, our manager wasn't trying to keep us informed. She was doing her best.” Male 03, clerical clerk “I think they did their best, right? We were having weekly information sessions informing us of the development of the pandemic. They were very informative (…) In some cases, we had to kind of understand the reality of things and understand that we are healthcare workers, we need to get, put all-hands-on deck and try to fight the situation as best as we can and the best we can is whatever knowledge we are able to gather so far, implement that and as we find more information, do the other extra mile. And this is a new disease or a new virus if we can say so and we are still in the learning process. We all have good intentions and like nothing is done like mistakenly. Everything is done like according to the protocols, according to the regulations or recommendations.” Female 06, patient attendant “I felt very strongly that I had to go and get information myself, and then figure things out and use my common sense with my team (…). ” Female 12, nephrologist |

9 |

|

Increased collaboration “I think so, I think it did force everybody to learn to work as a team to a higher level, you know? I think there was a little bit more individualism, you know, in the, before this started, and it's just not possible and everybody seems to have understood that. So, in a sense it's been, it's become more collaborative and more cooperative, you know? Which is a positive, I guess. ” Female 05, nurse “Yes, it wasn't easy. At the start of the pandemic, when everybody thought it would be a sprint, there was enormous collaboration and creativity. People supported each other to a very great extent. ” Female 12, nephrologist |

4 |

|

Innovative solution “Well, definitely… As regards patient interviews, meetings were no longer conducted directly in my office. It was really at the bedside and those who were isolated, I didn't meet them in person, it was done remotely by telephone.” Female 01, social worker “Well, that changed a lot, let's say for like usually we have once a week the multidisciplinary meeting. We discuss the cases of the patients, and, but then we had to switch to Zoom or Teams, like the online. So, it's new but it worked pretty good actually, so lots of things, yes.” Male 07, nephrologist |

3 |

|

Increased efficiency at work “Certainly that made our work a little more efficient, because no longer having to attend meetings in person was much easier.” Female 12, nephrologist |

2 |

|

Investing in additional resources “We finally got additional resources that we had been needing for years anyway (…) Finally we got additional beds, we got some additional resources, you know. We had faster technical support for problems, and a lot more could be done in that direction, you know.” Female 08, social worker |

1 |

Some participants recognized the importance of having accurate information during the pandemic to facilitate the organization of their work. Few believed that the information provided by their institution was sufficient and appropriate. Some said that they lacked information, and this was mentioned by participants from every hemodialysis center. However, others reported that they received a great amount of mixed information from different sources such as webinars or emails.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic had some negative impacts on the work of hemodialysis staff, some HCWs reported positive consequences on their work, including increased collaboration between different professionals and the development of innovative solutions to the challenges brought by the pandemic, such as the use of technology and telemedicine. Others stated that the COVID-19 pandemic helped them to be more efficient at work with the use of technology and online meetings. Finally, one participant considered that the COVID-19 pandemic was an opportunity for the government to realize the need to invest more resources in the health care system. Table 3 presents quotes.

2. Challenges Associated with Communicating with and Caring for Hemodialysis Patients

A major problem during the COVID-19 pandemic identified by HCWs was the difficulty of communicating with patients. Protective measures, such as masks and protective equipment, were associated with decreased time for HCWs to talk with patients; this was particularly marked in the case of patients with hearing disabilities (Table 4).

Table 4.

Challenges associated with communication with and caring for hemodialysis patients

| Themes and Interview Excerpts | N=22 |

|---|---|

|

Difficulty of communicating with patients “The only other, like the main thing is really communication, right? (…) it's really the communication aspect of things. Not being able to effectively or safely provide information to my patients, in the sense that I can't necessarily yell, right? At the clinic when they have hearing problems, so it's really finding alternatives. So, the communication aspect has been a difficult thing as well as kind of getting in touch with the patients over the phone. It becomes a challenge.” Female 06, patient attendant “Yes, for sure, you know I think of one patient in particular who's very hard of hearing and you really got to shout and get close to her to, for her to hear you, so that, when she was coming by herself, that was very difficult. I ended up writing things down and showing them to her cause she was very, very hard of hearing, and even at best times, you know you have to yell, you have to use a pretty high volume of voice to communicate with her.” Male 02, nurse “Yes, so we spend less time to communicate, I mean to socialize with the patients and ask: How are you doing? Even what we do when we connect patients, disconnect patients, we still have time too with them, but it's less than before and during like these brief conversations still we can feel that some of them, they really have hard time to cope with the situation.” Male 05, nutritionist |

7 |

|

Patients avoiding hospital or missing hemodialysis sessions “I know a lot of the patients when this first started were also trying to negotiate, you know: Do I really need to come in 3 times a week? Can I maybe come in twice a week? There was one patient that came in twice a week: Oh, do I even need dialysis.” Female 14, nephrologist “Absolutely. I had several who came less frequently, or who skipped appointments… When we had cases, or when we brought in new measures, they skipped dialyses, one or two dialyses, and that was out of fear of catching COVID.” Female 02, nurse “Yes, that's been a huge issue for my dialysis patients (…) Transport systems were refusing to pick the patients up to come to the hospital initially. That finally got straightened out and we had transport. And during the height of the first wave of the pandemic, my patients were coming in taxis alone, they weren't sharing their taxis with one another and transport adapté had some pretty good rules in place. But my patients since the fall or late summer have started to complain that all of a sudden, it was two people in a taxi.” Female 04, social worker |

16 |

|

Prohibition of visitors in dialysis “Yes, somewhat, because certain patients were often accompanied by their family. For example, there were some men whose spouse was practically always present at all the dialysis sessions, and often interventions were easier with the spouse or sometimes with the spouse or the child of the elderly dialyzed patient. So there were patients who were systematically accompanied at each treatment, and so that was a problem.” Female 03, nutritionist “But several people told me that they found it difficult, not being able to have their family or friends with them, if only to relieve the boredom. After all, these are four-hour sessions, so it's very difficult for people. Certainly, for me, having access to natural caregivers helped a lot. So yes, that could have had an impact.” Female 07, nephrologist “In all honesty, it has simplified our way of working, because often families intervene a great deal during the treatment, which, so no, most the time it made the job simpler. But with more disadvantaged patients or for patients who have a language deficit or a comprehension difficulty or who speak a foreign language, it was much more difficult to communicate with those patients.” Female 13, nurse |

11 |

Some HCWs were unable to provide care to some patients because the patients failed to come to the hospital. The reasons evoked for missing a dialysis session were problems with patient transportation or fears of being infected with COVID-19 in the hemodialysis units. Some patients tried to negotiate to reduce the frequency of dialysis sessions to twice a week instead of three times a week. Others wanted to postpone their dialysis sessions because they were very fearful of being exposed to COVID-19 infection.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, in most hemodialysis centers, visitors and caregivers could no longer accompany patients. HCWs were divided on this prohibition of visitors. Some saw it as an inconvenience, since visitors and caregivers could provide helpful assistance. Others saw it as positive, because visitors are not always seen as allies when providing care to patients.

“Because the people who accompany patients are not always allies, people who help us. Sometimes they can even be a hindrance. So no, it's not necessarily a bad thing. Of course some of the patients found it hard, but there you are. It's not something that really bothered me personally.” Female 05, nurse

3. Work-Related Psychological Distress and the Psychosocial Impact of COVID-19 on Personal Life

Some participants experienced psychological distress at work because of changing and conflicting information on public health measures. Participants said that they felt anxious in the face of acute stress at work and colleagues leaving the profession because of burn-out. Most participants were afraid of being infected with COVID-19. This fear was strong at the beginning of the pandemic and decreased over time. However, they were more afraid of being infected outside the hospital rather than in the dialysis unit, where infection prevention and control measures were described as comforting and reassuring. Participants who did not need to see patients physically were not afraid of being infected in the dialysis unit (Table 5).

Table 5.

Work-related psychological distress and psychosocial impact of COVID-19 on personal life

| Themes and Interview Excerpts | N=22 |

|---|---|

|

Psychological distress at work “I would say it's more stressful than like, than as usual because of the scheduling and with the patients, we have to put all the COVID positive patients in the same run and we have to reorganize the schedules. Sometimes it's very hard and plus the hospitalization, some patients they're hospitalized, so we have to like, we're already short of staff, plus like also from nurse's perspective, we're short and then we have to provide the care, however the patients are still the same patients and we can even get more. So, it's a very stressful situation, especially well, this year so far, we are better, but last year during the wave 1, it was very hard for us”. Male 05, nutritionist “And nurses are creatures of habit, they really like to have a routine and whenever there's an interruption in that routine, it can cause a little bit of anxiety and stress for nurses. It's probably the same for everybody but I've notice that with nurses especially and so when you're getting all this information you know and changing constantly, it caused quite a lot of frustration and anxiety amongst my colleagues, but I always tempered it with: Look, it's an evolving situation, you know?” Male 04, nurse “During the first and second waves, no, but I would say that right now, in the heart of the third wave, the shortage of staff is starting to be felt. We've had a lot of people leaving, a lot of sickness related to the stress of the pandemic, a lot of mental health cases who are on medical leave. So now the staff shortage is being felt, but during the first and second waves, we had sufficient staff.” Female 04, social worker |

6 |

|

Fears of being infected “Well, it's not an overwhelming fear, not a huge fear that paralyzes me. Certainly there is always a fear, but having had COVID at the start of the pandemic, I feel that fear to a lesser extent, but the fact remains that, you know, I take all precautions anyway, because there is no proof… I don't have any convincing proof that I could never get it again, you know… So we are still careful. So it's not an overwhelming fear, and, you know, if I am afraid, it's up to me to protect myself more, so I wash my hands more often, and all that…” Female 02, nurse “The thing is that personally, I feel safer at my work, because I know that all my colleagues take precautions. I feel safer at work than I do going to the supermarket, because let's face it at the supermarket lots of people lower their mask or don't wash their hands, and touch everything. Whereas at work, as soon as we arrive in the morning, it's disinfection before putting on your gloves, after putting on your gloves. It's clear that a lot of disinfection is being done. So no, as regards my work, I feel safer.” Female 10, patient attendant “Indeed, yes. The fear is different. In the beginning, in the first few months, we were really dealing with the unknown. Fear was more constant in our daily life in the sense that we felt that everything we touched or the virus was present everywhere, there was really this fear of bringing it home. You changed your clothes, but you wondered whether your coat had touched one thing or another. That is what the fear was like during the first wave, or should I say the first months. Now, I would say that the fear of being infected has more to do with long-term secondary effects or what we now know more about COVID, finally.” Female 03, nutritionist |

17 |

|

Anxiety “Yes, yes, yes, anxiety about organizing the family cell, anxiety about what might happen at work, anxiety in the face of the responsibility of keeping both my employees and my patients safe, and that responsibility was on my shoulders. So in fact it was a feeling that the responsibility lay with me.” Female 13, nurse “Anxiety increased, yes, yes, not necessarily about COVID, but about… In fact, it creates a, in fact since the context in which we work is conducive to anxiety to some extent, yes it definitely increases, it predisposes you to go about things with more anxiety.” Female 05, nurse “ (…) But definitely, anxiety is mainly a question of facing up to the unknown, wanting the best for patients, wanting with children doing distance schooling, no school at all during the first wave or distance schooling, then distance schooling one day in two for kids in high school, and for those who were at college (CEGEP), almost everything was online. That kind of anxiety, those preoccupations, yes, they affected my mental health.” Female 12, nephrologist |

7 |

|

Impact on family organization “Well, it's a bit of both because… I am a single mother of a child aged 6, so… I'm really on my own with her, and at the start, when the school closed, in March, I sent her to my parents… Except that we have never really been separated for very long, and so after a week my daughter found it very difficult. During the daytime, it was okay, but at night it was very, very, very difficult. So I talked with my bosses, and since I already had access rights with the ministry, etc., to work remotely and since my clinic allows me to work remotely, unlike people who deal with hospitalized patients, well they sent me home.” Female 01, social worker |

3 |

|

Feeling of loneliness and isolation “Yes, a lot. Isolation is our daily life, whether it's… I'm lucky to have a little family bubble with my small son, of whom I have shared custody, but otherwise it's not being able to see my parents as they get older, it's not being able to see my friends. There were friendships that were already fragile and which deteriorated completely through absence, to not seeing each other. So yes, I feel isolation on a daily basis.” Female 13, nurse “Well, I was isolated for almost six weeks, so yes… But all the same, I always felt supported, both by the hospital and by my family, and by my partner, all of them. I never felt completely alone amongst all those people” Female 02, nurse “Sure, you don't see anyone anymore, you are afraid of everybody, you are suspicious of everybody. There is no longer any connection, you feel you are growing apart. Yes, that's it, we become anti-social.” Female 08, social worker |

12 |

|

Unintended positive impacts of the pandemic “Some, I think, yes, I think people are revaluating, you know, what's important, you know, reprioritizing things in their lives, you know? I hear from nurses that they, you know, after 20 years away, they started taking piano lessons, and you know, things like these are all signs to me that people have been, you know, confronted with themselves and are, have decided to do away with useless distractions that were keeping them busy in the past. So, to me that's very positive, yes.” Male 03, nurse |

2 |

The COVID-19 pandemic also affected HCWs' personal lives. Some said that the new challenges caused them concern, even during their personal time. They also reported difficulties balancing work and family life. Women reported greater anxiety related to the challenges of family organization, such as home schooling during the first lockdown in spring 2020. Some of the participants—both women and men—were not able to see members of their family, notably their children, not only because of the lockdown but also because of the fear of infecting the rest of the family. To minimize the risks of exposing family members to the virus, some participants adopted cleaning routines to alleviate this fear, such as showering and putting their clothes in the washing machine as soon as they arrived home.

Most participants were concerned about a third or fourth wave of COVID-19. The development of variants and the small proportion of the Quebec population that was fully vaccinated at the time of the interviews contributed to their fears and anxiety.

A significant proportion of participants reported feeling lonely during the first wave, particularly nephrologists and patient attendants. Having a family appeared to alleviate the feeling of loneliness. A HCW's personality also seemed to affect their ability to tolerate isolation and loneliness: Those who said they liked staying at home felt less lonely and regarded not being able to go to restaurants or movie theaters as less of an inconvenience.

Some participants reported some positive impacts, such as having more time to devote to a new activity—learning to play the piano, for example. Others said that they learned to prioritize and focus on what they found important or that the pandemic led them to put things in perspective, enjoy life, and look at the bright side of things.

4. Recommendations for Future Pandemic Contexts

Participants made numerous recommendations for future pandemics. First, some participants encouraged people to continue practicing social distancing and observing public health measures to prevent overloading the health care system (Table 6).

“ (…) keeping vigilant with our social distancing and keep encouraging the community to be vigilant as well to kind of help us out so we’re not so overwhelmed.” Male 02, nurse

Table 6.

Recommendations for future pandemics

| Themes and Interview Excerpts | N=22 |

|---|---|

|

Social distancing and preventive measures “In the hospital setting, I think we must continue to maintain the precautions that are already in place. I think that would be helpful for reassuring people, and teams, that there was a degree of predictability regarding the second dose of vaccine.” Female 05, nurse “Other than just keeping vigilant with our social distancing and keep encouraging the community to be vigilant as well to kind of help us out so we're not so overwhelmed.” Male 02, nurse |

7 |

|

An adequate supply of protective equipment “There was definitely some messing up regarding the availability of protective equipment. There is definitely a strong need for improvement, because the pandemic may stretch on for how long?” Female 13, nurse |

2 |

|

Consistent communication strategies “Well I think we are now in the third wave. What I don't understand is that lockdown is being lifted and they know we are heading for a third wave, so I at least can't really understand why. I'm not in the government, that's not my job, but I don't understand at all. If you know you're heading into a third wave, why are you lifting restrictions? I don't understand. (…) So, because there are now more people, we are starting to have an outbreak in the hospital, in the clinic, and now they are opening the schools. But what they say is that we are going into a third wave. I'm just repeating what the government is saying. But if we start to open up, there is going to be more, definitely, but I don't understand what their goal is. I'm not more frightened than in the first wave, I'm just fed up.” Female 08, social worker |

1 |

|

Promoting vaccination “In terms of the nephrology community I think we have figured out the protocols. There's nothing I would want to change. So, no, I think the only thing is the vaccine campaign, both nurses and patients, they are all both offered and surprisingly the vaccine uptake on dialysis nurses is very low,” Female 11, nephrologist |

2 |

|

Screening protocols “Well, I find it strange that we employees are not tested more often regularly. Because, just this week, we received an email saying that there was a nurse who was asymptomatic, who worked for a whole week, and as a result cases are starting to rise in her three units… And finally to find out that it was an asymptomatic nurse who… how should I say… was spreading the disease to other people, who then became symptomatic, you know. So it was an employee who had zero symptoms who in fact, in spite of herself, it's not her fault, but I mean, you know, in spite of herself who… So that worries me because I think to myself, ‘Maybe I'm a carrier, but not aware of it.’ You know, perhaps I didn't develop symptoms as such.” Female 01, social worker |

1 |

HCW, health care worker.

Second, participants recommended that hospitals and the health care systems should ensure an adequate supply of protective equipment, develop improved communication strategies, develop screening protocols for patients and HCWs, and encourage HCWs and patients to be vaccinated. Another recommendation seen as important was to introduce measures to guarantee the confidentiality of patients' medical (infectious) status to prevent alarm in other patients, who could ask to change to another dialysis center for fear of being infected.

Finally, participants had recommendations for the government and the department of health, such as improving communications with the public, which should be consistent and should clearly explain the rationales behind lockdown, public health measures, and vaccination. They also recommended that the government should be better prepared for any future public health emergency.

Discussion

Our study documents the experiences of hemodialysis staff during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Canadian province of Quebec, which was particularly affected by COVID-19 in the first and second waves of the pandemic. Participants in our study reported increased workload, communication challenges, anxiety, and feelings of loneliness and isolation associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. That said, positive consequences were also associated with the pandemic, such as increased use of technology and innovative and collaborative solutions. Another qualitative study conducted with 23 health care providers in the United States during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the following themes, which share some similarities with our findings: (1) managing isolation, fear, and increased anxiety; (2) adapting to changes in health care policy and practice; (3) addressing the physical needs of patients and families; and (4) navigating workplace safety.22

One of the main consequences of COVID-19 reported by participants was the difficulty of communicating with patients, particularly patients with hearing disabilities, because of masks. Our study of hemodialysis patients also found that masks interfered with their communication with HCWs, since they were unable to see HCWs' facial expressions.14 In a recent systematic review of studies looking at physician and patient communication during the COVID-19 pandemic, protective equipment as a barrier to verbal and nonverbal expression was the most important theme under the topic of reduced communication.23 Masks could also prevent patients from visually recognizing their HCWs.24

One of the major themes raised by participants was information on pandemics. Participants wanted accurate and updated information and did not want to be overwhelmed with contradictory information. A survey conducted in Australia with intensive care HCWs showed that 32.1% of them felt the information they received on COVID-19 was excessive.11 This finding may have been influenced by the low rate of COVID-19 in Australia at this time. A qualitative study conducted with intensive care HCWs showed that inconsistent and contradictory information negatively affected their well-being.25 Providing HCWs with clear, updated information on the virus, transmission, and protective measures is a way of promoting their resilience.26

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the psychosocial status of HCWs. Numerous studies in various countries have shown an increased prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress disorders.27–31 A social media analysis has shown that nurses experienced anger, anxiety, and sadness.32 The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the health care system as a whole, including nephrology and hemodialysis. For instance, rapidly changing policies and care practice and fear of being infected have been reported as sources of moral distress among nephrology HCWs.33 A Swedish study showed that nephrology departments are where staff reported poorer working conditions.34

In our study, women emerged as more prone than men to stress and anxiety related to the COVID-19 pandemic. An international survey of HCWs conducted during the first wave of COVID-19 also found that women were more likely than men to be affected by stress arising out of the pandemic.35 Partly, this could be explained by work and family life organization during the lockdowns. Many women have had to pursue their professional activities and also manage family organization, which was particularly demanding when all schools closed in March 2020 and did not reopen until September 2020.

Although HCWs participating in our study expressed anxiety and psychosocial distress related to the COVID-19 pandemic, they did not mention moral distress, which occurs when HCWs are not able to work in accordance with their ethical standards.33 That said, the issue of moral distress was not specifically addressed during the interviews.

Some preventive strategies have been formulated in a recent review on moral distress to help HCWs face the psychosocial and moral challenges associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. These include (1) providing HCWs with a safe working environment with an adequate supply of protective equipment, (2) developing approaches to enhance communication and connection among HCWs and between HCWs and families, and (3) dynamic, responsive communication from the health service to inform HCWs about changes and the allocation of scarce resources.33 These preventive strategies are aligned with the recommendations for future pandemics made by participants in our study.

The first recommendation formulated by our participants was to pursue social distancing and observe public health measures. This recommendation was made during the second and third waves of COVID-19 infection. Currently, after the seventh wave of COVID-19 and the availability of new treatments and preventive strategies for COVID-19 for patients, there are almost no public health recommendations for the population (no mandatory masking in public locations except hospitals). It would, therefore, be interesting to survey HCPs on their views regarding the removal of public health measures.

We recognize our study limitations. We interviewed HCWs working in dialysis centers in an urban region predominantly affected by the first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. The results of our study could not be generalized to other health care contexts. Most of our participants were nephrologists or nurses and were mostly White and female and may not be representative of other HCWs' views. The experiences of HCWs could have evolved with the subsequent waves of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In conclusion, the findings of this study revealed that during the COVID-19 pandemic, HCWs in hemodialysis units faced multiple challenges that affected their well-being. The study highlights the need to take into account the work-related psychological distress suffered by HCWs, which could also affect their personal lives. To alleviate the challenges, participants made numerous recommendations for future pandemics, such as to continue social distancing and public health measures, ensure an adequate supply of protective equipment, and develop effective communication strategies. Further long-term studies on the psychosocial impact of pandemics on HCWs are needed to develop appropriate interventions to address their emotional well-being during these challenging times.

Disclosures

A. Affdal reports the following: Advisory or Leadership Role: Scientific Director—Canadian Journal of Bioethics. W. Beaubien-Souligny reports the following: Research Funding: Astra-Zeneca and Bayer. D. Blum reports the following: Honoraria: AstraZeneca and Otsuka. M.-C. Fortin reports the following: Advisory or Leadership Role: I am a member of the ethics committee of Transplant Quebec, the Collège des médecins du Québec, and the Canadian Society of Transplantation. I am also a member of different committees of the Canadian Blood Services. A.-C. Nadeau-Fredette reports the following: Other Interests or Relationships: Current Scholarship from Fonds de la recherche du Québec en Santé (FRQS). R. Suri reports the following: Honoraria: Amgen and Otskuka; and Advisory or Leadership Role: Canadian Society of Nephrology, Canadian Institutes of Health Research Institute of Circulatory and Respiratory Health, and McGill University. M. Vasilevsky reports the following: Consultancy: Doreen Wolpert Consulting Inc; Drug Intelligence.com; Ownership Interest: Bank of America, Birchcliff Energy Ltd, Brookfield Infrastructure Partners, CAE Inc, Canadian National Railway, CCL Industries Inc, Cenovus Energy, Eli Lilly, Enbridge Inc, Inovio Pharmaceuticals, Microsoft, Parkland Corporation, Precigen Inc, Rogers Communications, Sirius XM Holdings, Stellantis N.V., Teck Resources Ltd, Toronto Dominion Bank, West Fraser Timber Co Ltd, and Yamana Gold Inc; and Research Funding: GSK/PPD Investigator Services; Canadian Institute of Health Research via Sunnybrooke Research Institute. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This study was funded by Gouvernement du Canada|Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grant 447760.

Author Contributions

M.-C. Fortin and R. Suri conceptualized the study; A.-C. Nadeau-Fredette, W. Beaubien-Souligny, and R. Suri were responsible for funding acquisition; A. Affdal, M.-C. Fortin, and M.-F. Malo were responsible for formal analysis; A. Affdal, F. Ballesteros, D. Blum, M.-L. Caron, M.-C. Fortin, A.-C. Nadeau-Fredette, N. Rios, R. Suri, and M. Vasilevsky were responsible for investigation; M.-C. Fortin was responsible for methodology; A. Affdal and M.-C. Fortin wrote the original manuscript; and A.-C. Nadeau-Fredette, F. Ballesteros, W. Beaubien-Souligny, D. Blum, M.-L. Caron, M.-F. Malo, N. Rios, R. Suri, and M. Vasilevsky reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Data Sharing Statement

Partial restrictions to the data and/or materials apply (please include a detailed explanation). Data are available upon request.

References

- 1.Gouvernement du Québec. Data on COVID-19 in Quebec. 2021. Accessed September 23, 2021. https://www.quebec.ca/en/health/health-issues/a-z/2019-coronavirus/situation-coronavirus-in-quebec [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brousseau N Morin L Ouakki M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in health care workers from 10 hospitals in Quebec, Canada: a cross-sectional study. CMAJ. 2021;193(49):E1868-e1877. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.202783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salerno S Messana JM Gremel GW, et al. COVID-19 risk factors and mortality outcomes among Medicare patients receiving long-term dialysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(11):e2135379. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.35379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carriazo S Mas-Fontao S Seghers C, et al. Increased 1-year mortality in haemodialysis patients with COVID-19: a prospective, observational study. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15(3):432-441. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfab248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaubien-Souligny W Nadeau-Fredette AC Nguyen MN, et al. Infection control measures to prevent outbreaks of COVID-19 in Quebec hemodialysis units: a cross-sectional survey. CMAJ Open. 2021;9(4):E1232-E1241. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20210102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rombolà G, Brunini F. COVID-19 and dialysis: why we should be worried. J Nephrol. 2020;33(3):401-403. doi: 10.1007/s40620-020-00737-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiner DE, Watnick SG. Hemodialysis and COVID-19: an Achilles' heel in the pandemic health care response in the United States. Kidney Med. 2020;2(3):227-230. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2020.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institut National de Santé Publique. COVID-19: Infection Prevention and Control Measures for Hemodialysis Units. 2021. Accessed September 23, 2021. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/en/publications/2980-infection-prevention-control-measures-hemodialysis-units-covid19 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Cancer, dialysis patients infected as COVID-19 sweeps through Montreal's Sacré-Coeur hospital. 2020. Accessed September 24, 2021. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/sacr%C3%A9-c%C5%93ur-de-montr%C3%A9al-hospital-montreal-covid-19-1.5540492

- 10.McDougall RJ, Gillam L, Ko D, Holmes I, Delany C. Balancing health worker well-being and duty to care: an ethical approach to staff safety in COVID-19 and beyond. J Med Ethics. 2021;47:318-323. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2020-106557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammond NE Crowe L Abbenbroek B, et al. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on critical care healthcare workers' depression, anxiety, and stress levels. Aust Crit Care. 2021;34(2):146-154. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2020.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beaudet M Ravensbergen L DeWeese J, et al. Accessing hemodialysis clinics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transp Res Interdiscip Perspect. 2022;13:100533. doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2021.100533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goupil R Benlarbi M Beaubien-Souligny W, et al. Short-term antibody response after 1 dose of BNT162b2 vaccine in patients receiving hemodialysis. CMAJ. 2021;193(22):E793-E800. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.210673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malo M-F Affdal A Blum D, et al. Lived experiences of patients receiving hemodialysis during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study from the Quebec Renal Network. Kidney360. 2022;3603(6):1057-1064. doi: 10.34067/KID.0000182022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Healthc. 2007;19(6):349-357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. 3rd ed. SAGE; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(5):533-544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miles MB, Huberman MA. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Source Book of New Methods, Première ed. SAGE publications; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandelowski M. What's in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(1):77-84. doi: 10.1002/nur.20362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334-340. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poses PM, Isen AM. Qualitative research in medicine and health care. Questions and controversy. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(1):32-38. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00005.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ness MM, Saylor J, Di Fusco LA, Evans K. Healthcare providers' challenges during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: a qualitative approach. Nurs Health Sci. 2021;23(2):389-397. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wittenberg E, Goldsmith JV, Chen C, Prince-Paul M, Johnson RR. Opportunities to improve COVID-19 provider communication resources: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(3):438-451. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.12.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marler H, Ditton A. “I'm smiling back at you”: exploring the impact of mask wearing on communication in healthcare. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2021;56(1):205-214. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elliott R, Crowe L, Abbenbroek B, Grattan S, Hammond NE. Critical care health professionals' self-reported needs for wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic: a thematic analysis of survey responses. Aust Crit Care. 2022;35(1):40-45. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2021.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rieckert A Schuit E Bleijenberg N, et al. How can we build and maintain the resilience of our health care professionals during COVID-19? Recommendations based on a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e043718. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong F Liu HL Yang M, et al. Immediate psychosocial impact on healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2021;12:645460. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.645460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamb D Gnanapragasam S Greenberg N, et al. Psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on 4378 UK healthcare workers and ancillary staff: initial baseline data from a cohort study collected during the first wave of the pandemic. Occup Environ Med. 2021;78(11):801-808. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2020-107276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smallwood N Karimi L Bismark M, et al. High levels of psychosocial distress among Australian frontline healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey. Gen Psychiatry. 2021;34(5):e100577. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2021-100577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Kock JH Ann Latham H Cowden RG, et al. The mental health of NHS staff during the COVID-19 pandemic: two-wave Scottish cohort study. BJPsych Open. 2022;8(1):e23. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2021.1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Kock JH Latham HA Leslie SJ, et al. A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: implications for supporting psychological well-being. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):104. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-10070-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koren A, Alam MAU, Koneru S, DeVito A, Abdallah L, Liu B. Nursing perspectives on the impacts of COVID-19: social media content analysis. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(12):e31358. doi: 10.2196/31358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ducharlet K Trivedi M Gelfand SL, et al. Moral distress and moral injury in nephrology during the COVID-19 pandemic. Semin Nephrol. 2021;41(3):253-261. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2021.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jonsdottir IH, Degl'Innocenti A, Ahlstrom L, Finizia C, Wijk H, Åkerström M. A pre/post analysis of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the psychosocial work environment and recovery among healthcare workers in a large university hospital in Sweden. J Public Health Res. 2021;10(4):2329. doi: 10.4081/jphr.2021.2329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Couarraze S Delamarre L Marhar F, et al. The major worldwide stress of healthcare professionals during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic - the international COVISTRESS survey. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0257840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Partial restrictions to the data and/or materials apply (please include a detailed explanation). Data are available upon request.