Abstract

The present study examined what kind of parenting best supports toddlers’ self-control in the context of poverty. Parents and toddlers (52% female; Mage = 2.60 years) in 117 families (35% White, 25% Black, 22% Latinx, 15% Multiracial, and 3% Asian; M family income = $1,845/month) engaged in structured interaction tasks, and toddlers completed a snack delay task concurrently and after 6 months. Latent profile analysis based on eight observed parenting behaviors representing learning support and responsiveness/sensitivity (e.g., teaching, technical scaffolding, teamwork, instructions, choices, language use, specific praise, and warmth) identified four parenting profiles: Lower Learning Support/Lower Responsiveness, Moderate Learning Support/Moderate Responsiveness, High Responsiveness, and High Learning Support. Toddlers with parents in the High Learning Support profile demonstrated the greatest self-control 6 months later, compared with toddlers of parents in the other three profiles, and there were no statistically significant differences in self-control among toddlers of parents in those other three profiles. Results were robust even after controlling for initial levels of self-control, as well as multiple other child, parent, and family characteristics. These study findings highlight the importance of parents’ learning support in understanding the early development of toddlers’ self-control in the context of poverty and reinforce the need to create and refine preventive interventions in this area.

Keywords: parenting, toddlers, self-control, latent profile analysis, poverty

Self-control refers to the tendency to recognize social and task demands and adjust behavior accordingly. As toddlers begin to assert their autonomy, they also must learn self-control through socialization (Murray & Kochanska, 2002). Due to brain maturation, self-control develops most rapidly, and may be most malleable, during the first few years of life (Kopp, 1982). Early self-control predicts multiple adaptive outcomes in adolescence and adulthood, including educational achievement, social-emotional functioning, and physical health (Eigsti et al., 2006; Moffitt et al., 2011; Schlam et al., 2013).

Living in poverty is associated with multiple risk factors and chronic stressors that can create challenges for the optimal development and strategic deployment of self-control (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002; Li-Grining, 2007). However, parents can buffer those negative effects of poverty (Kopystynska et al., 2016; Lengua et al., 2007; Merz et al., 2016). The present study examined which configurations of parenting behaviors among families living in poverty are most associated with toddlers’ development of self-control.

The Importance of Toddlers’ and Young Children’s Self-Control

As an umbrella term, self-control highlights the similarities and bridges the differences among multiple related but distinct constructs, including delay of gratification, effortful control, and executive function. All of these constructs feature a common process, including executive attention, acting in the service of a common goal, and inhibition (Zhou et al., 2012). They vary in their relative positions along the continuum of top-down emotional versus cognitive processing systems, with both delay of gratification and effortful control tending to involve metaphorically “hot,” motivationally relevant, and emotion-laden stimuli, and executive function tending to involve metaphorically “cool” and affectively neutral stimuli (Zelazo & Carlson, 2012; Zhou et al., 2012). Self-control is implicated in delay of gratification, wherein young children exercise willpower, often by distracting themselves, and refrain from choosing an immediate reward to achieve a more desirable future reward (Mischel et al., 1989; Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999). It appears that the common components of self-control account for much of the value of delay of gratification in predicting future adjustment (Duckworth et al., 2013). Self-control includes aspects of effortful control, a characteristic of infant and toddler temperament reflected in the tendency to follow caregiver instructions (or household rules) and suppress dominant behavioral responses to perform modulated or subdominant responses instead (Kochanska et al., 2000; Kopp, 1982; Rothbart et al., 2011). Factors such as secure attachment predict children’s ability and willingness to regulate emotions and refrain from enacting those dominant responses (Nordling et al., 2016). Over time, this particular form of inhibition becomes the foundation for committed compliance, the internalization of rule-based principles of conduct, and the perception of oneself as moral (Kochanska, 2002). Self-control also includes aspects of executive function, which is composed of working memory, set shifting, and inhibitory control, and acts as “… a set of general-purpose control mechanisms, often linked to the prefrontal cortex of the brain, that regulate the dynamics of human cognition and action” (Miyake & Friedman, 2012, p. 8). Although working memory, set shifting, and inhibitory control tend to be overlapping and difficult to distinguish among toddlers and young children (Wiebe et al., 2011), they differentiate as children grow older (Miyake et al., 2000).

Self-control in young children has been measured through multiple behavioral measures, as well as computerized tasks and parent, teacher, and observer ratings (Carlson, 2005; Gagne, 2017; Kochanska et al., 2000; Smith-Donald et al., 2007). Some of the better measures of self-control in young children are delay tasks (Murray & Kochanska, 2002; Smith-Donald et al., 2007). They tend to be good indicators of individual differences that are not overly determined by psychosocial, sociodemographic, or residential risk factors (Li-Grining, 2007). In the famous marshmallow test, a delay of gratification task, children, ages 4- to 5-years-old, are typically told they can have one treat any time they like or two treats if they wait until the experimenter returns, usually 7 or 15 min (Shoda et al., 1990; Watts et al., 2018). In this task, there may be one critical threshold effect separating children who can and cannot wait at least 20 s, another threshold effect around 2 min, and yet more important variability among children who can wait at least 7 min but not the full 15 min (Falk et al., 2020; Watts et al., 2018). Toddlers, ages 2- to 3-years-old, have less self-control and struggle to understand the trade-off in the traditional delay of gratification protocol due to more limited verbal ability and future time comprehension. As a consequence, they are asked to simply wait to eat a treat until time is up (Carlson, 2005; Kochanska et al., 1996). Although success for older children in delay tasks depends on their own independent reward assessment and success for toddlers reflects their tendency to refrain from doing what they want (e.g., eat the treat now) and motivation to act in accordance with internalized social rules, the underlying attentional mechanisms are similar: focusing on a longer-term goal and suppressing the activation of immediate emotional/behavioral responses (Mischel & Ayduk, 2002).

Inherent in the value of self-control is the ability to use it strategically, as the benefits of delay may depend on the contingencies within the environment (Sturge-Apple et al., 2017). For example, when the continuing availability of future reward is uncertain, it may be more adaptive to choose an immediate reward rather than delay (Lee & Carlson, 2015). However, when there are multiple opportunities to make choices and the future is predictable, it may be better to wait (Fawcett et al., 2012). It seems most important that children develop and hone self-control tendencies they can deploy, as desired, to achieve self-identified goals.

When children have better self-control tendencies, they display positive adjustment in multiple areas. For example, they can better persevere in challenging academic tasks (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999; Shoda et al., 1990). Relatedly, when children are able to inhibit impulses that prioritize their own needs and instead think about what others might want or may feel, they are more likely to engage in prosocial behaviors and establish more positive peer relationships (Eigsti et al., 2006). Early self-control is related to later substance use and Body Mass Index (Duckworth et al., 2013; Francis & Susman, 2009). In fact, children who have better self-control by the end of preschool have different brain structures well into adulthood (Casey et al., 2011). Not surprisingly, though, the strength of those relations between self-control and future well-being varies, often dramatically, depending on the era in which a study was conducted, the specific sample of children included, and what other related characteristics are or are not controlled for (Duckworth et al., 2013; Falk et al., 2020; Shoda et al., 1990; Watts et al., 2018).

Poverty and the Development of Self-Control

Children living in poverty are more likely to face adverse experiences that can create challenges for optimal development (Duncan et al., 1994; Evans, 2004). Their families experience elevated levels of chronic stressors such as food insecurity, health problems, unsafe environments, and less access to quality social resources/services, compared with higher-income families (Bingenheimer et al., 2005; Ross & Mirowsky, 2001; Slopen et al., 2010). These chronic stressors may impair children’s neurocognitive functioning and contribute to socioeconomic disparities in well-being, including academic achievement (Evans & Schamberg, 2009). These chronic stressors also may deplete the cognitive and emotional resources necessary to support self-control (Muraven & Baumeister, 2000).

At the same time, intentional and tactical use of self-control may help children manage stress and promote positive development, even in the context of poverty. For example, higher delay of gratification tendencies in middle childhood can buffer the negative effects of early poverty experiences on working memory among young adults (Evans & Fuller-Rowell, 2013). As children develop greater self-control skills, they may feel less vulnerable to unpredictable, external forces and may be more adept at maintaining attention and focusing on important tasks (Schibli et al., 2017). Relatedly, when children are better able to regulate their emotions and behaviors, they are more likely to inhibit negative reactions to environmental pressures and sustain engagement in goal-directed activities (Compas et al., 2001). As such, self-control may operate as a protective factor for children’s academic achievement and social competence (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 2009).

Parenting as a Protective Factor for the Development of Self-Control

Parenting quality may be a key factor that buffers the adverse effects of poverty on children’s development (Blair et al., 2008; McLoyd, 1998). Although numerous studies have found negative effects of poverty on parent–child interactions, some families are more affected by their circumstances than others (Gavidia-Payne et al., 2015). Some parents appear able to devise ways to manage the seemingly overwhelming challenges they face, yet still provide responsive and sensitive caregiving that promotes children’s positive development (Carpenter & Mendez, 2013; Cook et al., 2012). Even after accounting for family demographic factors and other related child-related characteristics, parenting is a strong predictor of children’s self-control, such as delay of gratification tendencies (Bindman et al., 2015; Razza & Raymond, 2013).

There are multiple parenting behaviors involving learning support and responsiveness/sensitivity that overlap with each other and co-occur to promote toddlers’ self-control, often through the encouragement of toddlers’ autonomy. Effective teaching behaviors, including active engagement, clear communication patterns, and consistent structure, appear important for children’s development of self-control, especially in the context of poverty (Wyman et al., 2000). Parents’ technical scaffolding, which comprises providing optimal support for children’s independent mastery of a task, is associated with children’s self-control, particularly emotional and behavioral regulation (Hoffman et al., 2006). In contrast to commands without explanations, instructions and directions that provide reasons for following rules can help children internalize those rules, which also helps with emotional and behavioral regulation (Houck & Lecuyer-Maus, 2004; Kochanska & Knaack, 2003).

Parents’ responsiveness is related to children’s self-control (Kochanska et al., 2000). Indeed, changes in parents’ responsiveness and sensitivity are related to changes in children’s executive functions, including inhibitory control (Blair et al., 2014). Parents’ appropriate expectations, support for children’s agency, and sensitivity toward distress can help children learn to manage negative emotions, like frustration, and persist in challenging tasks (Hughes & Ensor, 2009; Kochanska et al., 2000; Razza & Raymond, 2013; Williams & Berthelsen, 2017). Likewise, mutual parent–child affect regulation between parents and children is related to self-control, especially when children have a more difficult temperament (Feldman et al., 1999).

Because parenting is dynamic and complex, it is important to understand how those different parenting behaviors related to learning support and responsiveness operate together. For example, parents’ verbal instructions and guidance affect children’s self-control, but only in the context of high sensitivity (Kopystynska et al., 2016). To better capture the interplay of individual parenting behaviors, much research has focused on configurations or profiles of multiple parenting behaviors (Borden et al., 2014; Brody & Flor, 1998; Carpenter & Mendez, 2013; Cook et al., 2012; Iruka et al., 2018; McGroder, 2000; McWayne et al., 2009). Compared with studies of individual parenting behaviors in isolation, these person-oriented approaches have the potential to provide more useful insight on how parenting is related to children’s development.

The Present Study

The present study sought to understand self-control among toddlers living in poverty during one of the periods of most rapid development. Specifically, this study examined how different profiles of parenting behaviors involving learning support and responsiveness were related to self-control, assessed 6 months later. It also tested whether relations between parenting behaviors and toddlers’ future self-control were robust and not altered substantially by other child, parent, and family characteristics, including initial levels of self-control.

Method

The Institutional Review Boards of the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Pennsylvania State University approved all procedures for this study (Study Title: Promoting Self-Regulation Skills and Healthy Eating Habits in Early Head Start, #2016-0465).

Participants

Families were recruited through Early Head Start programs in seven urban and rural areas of Wisconsin and Pennsylvania. To be eligible for Early Head Start, most families had to have incomes below the federal poverty threshold. To be eligible for this study, families had to be able to complete assessments in English and include toddlers, ages 2- to 3-years-old. About 65% of eligible families chose to participate in this study.

This study relied on data from families in the control condition of the Recipe 4 Success clinical trial. Families in the control condition continued to receive standard Early Head Start home visits, but, unlike families in the intervention condition, did not participate in activities specifically designed to promote toddlers’ self-control.

This study included 117 families. Thirty-five percent of families were White; 25% were Black; 22% were Latinx; 15% were Multiracial; and 3% were Asian. Ninety-five percent of parents were mothers. Fifty-six percent of parents were married or living with a romantic partner. Sixty-six percent of parents had a high school degree or less. Thirty-six percent of parents were employed outside the home, about equally divided between having a part-time or full-time job; M family income was $1,845 per month.

In those families, 52% of toddlers were girls, and 48% were boys. On average, toddlers were 2.60 years old (SD = .33) at the beginning of this study.

Assessment Procedures

All assessments were conducted in families’ homes by project interviewers, selected for their experience, interpersonal skills, and attention to detail, and trained in all study procedures. The Time 1 assessments were conducted as soon as parents indicated they were interested in the study and before they had been randomly assigned to the control condition. Time 2 assessments were conducted about 6 months later (M = 189.70 days, SD = 54.48). Both Time 1 and Time 2 assessments lasted about 90 min, plus two 10-min follow-up telephone calls. Each time, parents received monetary payments of $75, and toddlers received stickers and small prizes.

Measures

For this study, the measures of parenting behaviors were collected at Time 1, as were all child, parent, and family characteristics. The measure of toddlers’ self-control was collected at both Time 1 and Time 2.

Parenting Behaviors

This study relied on three 3-min structured parent–child interaction tasks—playing with a stuffed bowling ball and pins, building a block tower with different-sized blocks, and completing a shape sorter puzzle—to assess eight parenting behaviors, derived from prior interaction coding protocols (Bierman et al., 2015; Hoffman et al., 2006; McNeil & Hembree-Kigin, 2010). Four of the parenting behaviors represented aspects of learning support: Teaching reflected parents’ attempts to impart new knowledge or gently quiz toddlers about previously learned facts; technical scaffolding represented parents’ ability to organize materials and task procedures, providing just enough structure so toddlers could be successful on their own; teamwork assessed parents’ tendency to coordinate and combine their own efforts with those of their toddlers in pursuit of a joint goal; and instructions signified telling toddlers what to do, to help achieve their goal. The other four parenting behaviors represented aspects of responsiveness: Choices assessed how often parents asked toddlers what they would prefer among clear options and followed their toddlers’ lead in determining the direction of activities; language use assessed parents’ listening carefully to what their toddlers were trying to communicate and repeating back or expanding on what they were saying as a means of encouragement; specific praise involved noticing toddlers’ sustained effort and providing positive verbal or physical reinforcement; and warmth reflected parents’ tendencies to be gentle, kind, and attuned to toddlers’ needs and wishes.

Teams of two trained research assistants viewed each video recording of each interaction task and completed ratings. Teaching, teamwork, instructions, and warmth were rated on 5-point Likert scales with 1 = rarely or never and 5 = almost always. Technical scaffolding was rated on a 5-point scale with detailed behavioral descriptions as anchor points (Hoffman et al., 2006). Choices, language use, and specific praise were based on counts with 0 = none, 1 = once, and 2 = twice or more. Intraclass correlation coefficients for each rating were .72-.87 (calculated on the entire sample of control and intervention condition families). When ratings differed by three points or less on the 5-point scales or by one point or less on the 3-point scale, they were averaged; when discrepancies were larger than that, research assistants rewatched the interaction task together to reach consensus. Ratings across each of the three structured interaction tasks were averaged for final scores.

Toddlers ’ Self-Control

Toddlers’ self-control was assessed with the snack delay task (Kochanska et al., 2000; Murray & Kochanska, 2002). Across four successive trials, project interviewers placed a single M&M on a plate and told the toddlers the candy was for them, but they had to wait before eating it. The toddlers were not told anything about the length of the trials, which lasted 5, 30, 45, and 60 s, and they were not provided with any visual cues, other than the project interviewers’ looking at a stopwatch. Each trial was scored as 0 = child ate candy before time was up and 1 = child waited entire time, and all trial scores were averaged for a total score (α = .85).

Child, Parent, and Family Characteristics

In addition to toddlers’ self-control at Time 1, this study included 15 other child, parent, and family characteristics as covariates. Three of these characteristics assessed child factors closely related to self-control. Impulsiveness was assessed with six items from the impulsiveness subscale of the Infant-Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (Carter et al., 2003), such as “Restless and cannot sit still,” rated by parents using a 3-point Likert scale with 1 = not true/rarely and 3 = very true/often (α = .54). Likewise, mastery motivation was assessed with six items from the mastery motivation subscale of the Infant-Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (Carter et al., 2003), such as “Enjoys challenging activities,” rated by parents using a 3-point Likert scale with 1 = not true/rarely and 3 = very true/often (α = .74). Social competence, which incorporates aspects of emotion regulation, was assessed with six items from the Social Competence scale (Bierman et al., 2008; Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1990), such as “Copes well with anger, frustration, or disappointment,” rated by parents using a 4-point Likert scale with 1 = rarely and 4 = almost all the time (α = .69).

Four characteristics represented aspects of parent and family functioning. Parent symptoms of depression were assessed with all 20 questions from the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (Radloff, 1977), such as “During the last week, how often did you feel depressed?,” rated by parents on a 4-point Likert scale with 0 = rarely (<1 day) and 3 = almost all of the time (5–7 days) (α = .88). Parenting stresses with young children were assessed with five items from the Daily Hassles scale (Crnic & Greenberg, 1990), such as “Children get in the way or interfere with chores,” rated by parents on a 4-point Likert scale with 1 = rarely and 4 = almost all the time (α = .70). Household chaos was assessed with six items from the Confusion, Hubbub, and Order scale (Matheny et al., 1995), such as “You cannot hear yourself think in your home,” rated by parents on a 4-point Likert scale with 1 = rarely and 4 = almost all the time (α = .82). Need for case management or therapeutic services was assessed with three items from an adapted version of the Post-Visit Inventory (Dodge et al., 1990), such as “The parent could benefit from parent training,” rated by project interviewers after completing the in-home assessment, on a 10-point Likert scale with 1 = not at all and 10 = very much (α = .83).

Finally, eight characteristics represented demographic attributes, including child age in months, gender, race and ethnicity, parent educational attainment, parent employment outside the home, parent relationship status, family size, and financial strain (i.e., number of months in the past year the family struggled to pay bills).

Plan of Analysis

In this study, latent profile analysis was used to identify distinct subgroups of parents based on patterns of scores on the eight observed parenting behaviors: teaching, technical scaffolding, teamwork, instructions, choices, language use, specific praise, and warmth. All scores on parenting behaviors were standardized (M = .00, SD = 1.00). Separate finite mixture models with 1–5 groups of parents were estimated in Mplus (Version 8.3; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017).

In the first step of the latent profile analysis, multiple criteria were used to compare the relative balance of precision and parsimony across models. The Akaike information criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1974) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC; Schwarz, 1978), in which smaller values are preferred, were used to examine model fit. The Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio test (BLRT) and Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin (VLMR) statistics, in which significant values indicate that a model with one extra profile is better than a model with one fewer profiles (Nylund et al., 2007), were also examined. Finally, entropy, which ideally should be greater than .80, was used to assess the clear delineation of profiles from one another (Hart et al., 2016; Jung & Wickrama, 2008). Data from 119 intervention condition families at Time 1, before families had participated in lessons designed to promote toddlers’ self-control, were included in this first step of the latent profile analysis to enhance statistical power and better capture sample heterogeneity. However, once the profiles in the final model were identified, intervention group families were excluded from all further analyses so that possible intervention effects did not confound the interpretation of developmental processes.

In the second step of the latent profile analysis, the match between each family and each profile was assessed. Each family has a 0–100% chance of being in each profile, based on the family’s pattern of scores on the eight observed parenting behaviors. These probabilities were used to make modal class assignments, which involves placing families in the profiles in which they have the highest likelihood of belonging. However, the probabilities also were used to calculate classification errors for each family, the inverse of which can function as weights (Bolck et al., 2004).

In the third step of the latent profile analysis, the relation between the parenting profiles and the distal outcome, toddlers’ self-control at Time 2, as measured by the snack delay task, was estimated, using the manual Bolck-Croon-Hagenaars (BCH) method (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2021; Bolck et al., 2004; Nylund-Gibson et al., 2019). In this step, family-level weights from the second step were used to account for uncertainty in profile assignment and reduce bias in point estimates and standard errors of profile means.

Finally, although relations between parenting profiles and toddlers’ self-control were assumed to have high construct validity, covariates were added to the latent profile analysis to assess the sensitivity and robustness of results to possible confounding. Most important, to estimate residualized change, toddlers’ self-control at Time 1 was added to assess relations between parenting profiles and toddlers’ self-control at Time 2, controlling for initial differences. Subsequently, the effect of each of the other 15 child, parent, and family characteristics was tested on its own. This allowed us to avoid overfitting the data—given model complexity and sample size—but pinpoint how each characteristic might alter relations between parenting profiles and toddlers’ self-control at Time 2.

Results

Two of the 119 families randomly assigned to the control group were excluded from all analyses due to missing video recordings of parent–child interactions, yielding a study sample of 117 families. Ninety-four percent of these families, n = 110, had data for toddlers’ self-control at Time 2. However, because Mplus relies on full-information maximum likelihood estimation procedures and uses all available data, all 117 families were included in analyses.

Descriptive statistics including the means, standard deviations, and observed ranges of scores for all study variables are presented in Table 1. Across the entire sample, there was virtually no change in toddlers’ self-control between Time 1 and Time 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Study variables | N | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting indicators | ||||

| Teaching | 117 | 1.95 | .59 | 1.08–3.75 |

| Technical scaffolding | 117 | 3.34 | .65 | 1.67–4.92 |

| Teamwork | 117 | 2.53 | .58 | 1.38–4.00 |

| Instructions | 117 | 2.85 | .78 | 1.38–4.00 |

| Choices | 117 | 0.20 | .28 | 0.00–1.17 |

| Language use | 117 | 0.70 | .53 | 0.00–2.00 |

| Specific praise | 117 | 0.21 | .31 | 0.00–1.17 |

| Warmth | 117 | 3.83 | .74 | 1.67–5.00 |

| Toddlers’ self-control | ||||

| Self-control at Time 1 | 116 | .54 | .39 | .00–1.00 |

| Self-control at Time 2 | 110 | .57 | .40 | .00–1.00 |

Correlations among parenting behaviors, toddlers’ self-control, and child, parent, and family characteristics are presented in Table 2. Although some correlations among the eight parenting behaviors were large, most of these correlations were small to moderate in magnitude (r = .18–.35), suggesting that the behaviors were not overly redundant with one another and that each behavior provided unique information about parent–child interactions. Teaching, technical scaffolding, teamwork, and choices, but not instructions, language use, specific praise, or warmth, had small but statistically significant concurrent or prospective correlations with toddlers’ self-control.

Table 2.

Correlations Among Study Variables

| Study variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Teaching | ||||||||||

| 2. Technical scaffolding | .49 | |||||||||

| 3. Teamwork | .39 | .69 | ||||||||

| 4. Instructions | −.10 | −.05 | .11 | |||||||

| 5. Choices | .07 | .07 | .07 | −.17 | ||||||

| 6. Language use | .45 | .25 | .08 | −.23 | .04 | |||||

| 7. Specific praise | .17 | .22 | .09 | −.17 | .05 | .22 | ||||

| 8. Warmth | .43 | .64 | .39 | −.18 | .01 | .34 | .29 | |||

| 9. Self-control at Time 1 | .06 | .13 | .16 | .03 | .18 | −.15 | −.11 | .07 | ||

| 10. Self-control at Time 2 | .23 | .33 | .35 | −.02 | .20 | −.03 | −.11 | .12 | .31 | |

| Study covariates | ||||||||||

| Impulsiveness | −.12 | −.21 | −.15 | .01 | .02 | −.12 | −.10 | −.08 | −.02 | −.08 |

| Mastery motivation | .16 | .13 | .13 | −.09 | .08 | .06 | .10 | .06 | −.12 | .12 |

| Social competence | −.04 | .07 | .19 | .06 | .15 | −.06 | .04 | .01 | .15 | .14 |

| Parent depression | .01 | −.04 | −.06 | −.10 | −.08 | .05 | −.02 | .07 | −.08 | −.07 |

| Parenting stresses | .11 | −.10 | −.07 | .05 | .03 | .00 | −.08 | .02 | .02 | .10 |

| Household chaos | .16 | −.01 | .00 | −.06 | −.02 | .02 | .01 | .12 | .02 | .04 |

| Need for services | −.14 | −.39 | −.36 | .02 | −.06 | −.05 | −.15 | −.22 | −.18 | −.22 |

| Child age | .16 | .07 | .29 | .03 | .09 | −.10 | −.10 | −.06 | .24 | .33 |

| Child gender | −.20 | −.13 | −.04 | −.07 | −.17 | −.00 | .02 | −.17 | −.19 | −.29 |

| Race/ethnicity | −.17 | −.19 | −.19 | .07 | −.15 | −.04 | −.16 | −.19 | −.17 | −.26 |

| Parent education | −.05 | .02 | .08 | −.05 | .12 | .07 | .01 | .08 | −.01 | .00 |

| Parent employment | −.05 | −.09 | −.06 | .17 | .00 | −.15 | −.13 | −.01 | .14 | −.04 |

| Relationship status | −.15 | −.06 | −.17 | −.01 | −.17 | −.06 | −.21 | −.11 | .11 | −.02 |

| Family size | .15 | .03 | .16 | −.05 | .14 | .04 | .20 | .03 | −.14 | .08 |

| Financial strain | .14 | −.04 | .08 | −.06 | .12 | −.03 | .03 | .14 | .01 | .01 |

Note. Correlations in bold are statistically significant, p < .05.

Finite Mixture Models

Fit indices for the finite mixture models with one to five groups of parents are presented in Table 3. When the one-profile model was compared with the two-profile model, the two-profile model had better fit, as suggested by a lower AIC and BIC and significant BLRT and VLMR values. When the two-profile model was compared with the three-profile model, the three-profile model had better fit, as suggested by a lower AIC and BIC, significant BLRT and VLMR values, and higher entropy. When the three-profile model was compared with the four-profile model, the four-profile model had better fit, as suggested by a lower AIC and BIC, significant BLRT and VLMR values, and higher entropy. When the four-profile model was compared with the five-profile model, the four-profile model appeared to have better fit, as suggested by a lower BIC, nonsignificant VLMR value, and higher entropy, but the five-profile model appeared to have better fit as suggested by a lower AIC and significant BLRT value. Given the weight of the evidence and a preference for parsimony, the four-profile model was selected as optimal for interpretation and additional analysis. For this model, average posterior probabilities of actually being in the profile in which families had the greatest likelihood of belonging were high, ranging from .89–.92 across the four profiles.

Table 3.

Comparison of Model Fit for Models With 1–5 Groups

| Fit indices | 1 group | 2 groups | 3 groups | 4 groups | 5 groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIC | 5,368.01 | 5,097.76 | 4,999.95 | 4,929.79 | 4,909.62 |

| BIC | 5,423.43 | 5,184.35 | 5,117.72 | 5,078.73 | 5,089.74 |

| Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test | NA | −2,668.00*** | −2,523.88*** | −2,472.32*** | −2,421.89*** |

| Vuong-Lo-Mendall-Rubin | NA | −2,668.00* | −2,523.88*** | −2,472.32** | −2,421.89 |

| Entropy | 1.00 | .77 | .81 | .83 | .81 |

Note. AIC = Akaike’s information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

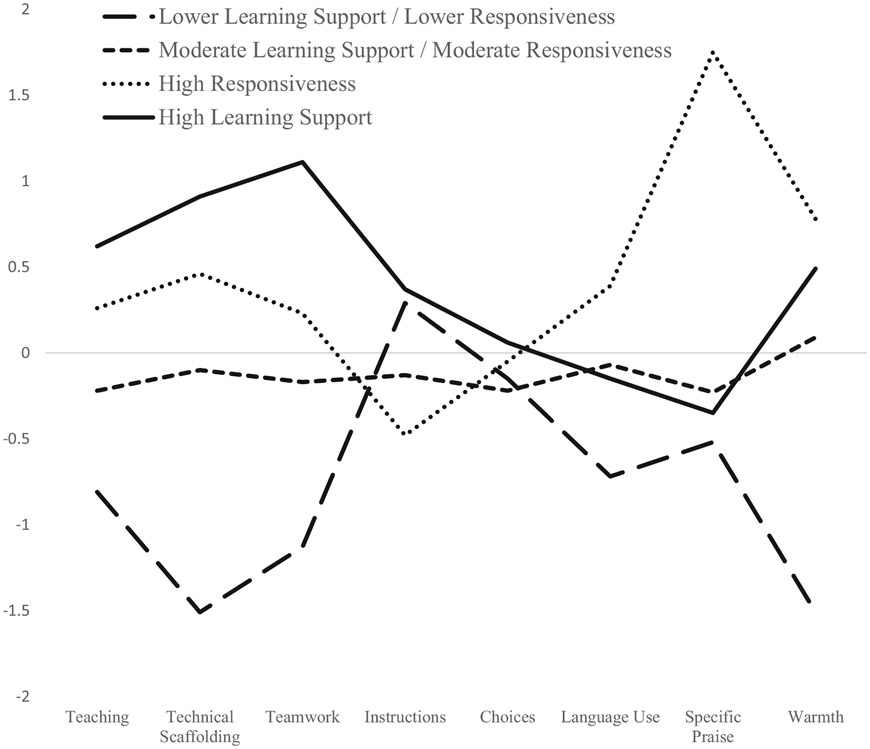

As depicted in Figure 1, the final four-profile model included the following groups of parents, named for the most salient differences among the parenting behaviors: Lower Learning Support/Lower Responsiveness, Moderate Learning Support/Moderate Responsiveness, High Responsiveness, and High Learning Support. The parents in the Lower Learning Support/Lower Responsiveness profile (approximately 23% of the sample) tended to receive below average scores on all parenting behaviors, except instructions. The parents in the Moderate Learning Support/Moderate Responsiveness profile (approximately 45% of the sample) tended to receive average scores across all parenting behaviors. The parents in the High Responsiveness profile (approximately 10% of the sample) received above average scores on teaching, technical scaffolding, and teamwork; below average scores on instructions; average scores on choices; and well-above average scores on language use, specific praise, and warmth. Finally, parents in the High Learning Support profile (approximately 22% of the sample) received well-above average scores on teaching, technical scaffolding, teamwork, and instructions; average scores on choices and language use; below average scores on specific praise; and well-above average scores on warmth. Means of the eight parenting behaviors across each of the four profiles, as well as significant differences among those means, are presented in the top part of Table 4.

Figure 1. Parenting Profiles.

Note. y-axis represents standardized scores, so a score of 1 indicates 1 SD above the sample mean.

Table 4.

Means of Parenting Behaviors and Toddlers’ Self-Control by Parenting Profiles

| Study variables | Lower learning support/lower responsiveness 23% of sample |

Moderate learning support/ moderate responsiveness 45% of sample |

High responsiveness 10% of sample |

High learning support 22% of sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting behaviors | ||||

| Teaching | −0.81a | −0.22b | 0.26b,c | 0.62c |

| Technical scaffolding | −1.51a | −0.10b | 0.46c | 0.91c |

| Teamwork | −1.13a | −0.17b | 0.23b | 1.11c |

| Instructions | 0.29a | −0.13a | −0.48a | 0.37a |

| Choices | −0.15a | −0.22a | −0.05a | 0.06a |

| Language use | −0.72a | −0.07b | 0.39b | −0.15b |

| Specific praise | −0.52a | −0.23a | 1.75b | −0.35a |

| Warmth | −1.51a | 0.09b | 0.78c | 0.49b,c |

| Toddler behaviors | ||||

| Self-control at Time 1 | −0.30a | 0.07a | −0.25a | 0.30a |

| Self-control at Time 2 | −0.50a | −0.04a | −0.16a | 0.82b |

Note. Parenting behaviors, but not toddler behaviors, were used as indicators of latent profiles. Self-control at Time 1 was a covariate, and self-control at Time 2 was a distal outcome. Profile prevalence rates, means, and mean differences were derived from the Bolck-Croon-Hagenaars (BCH) method and accounted for uncertainty in profile assignment. All means of parenting behaviors and toddlers’ self-control are standardized. Means with different subscripts within each row are statistically different, p < .05; means with the same subscripts within each row are not statistically different, p > .05. Subscripts only apply within each row, not across all rows.

Parenting Profiles and Toddlers’ Self-Control

When the manual three-step BCH method was used to estimate relations between those four parenting profiles and toddlers’ self-control at Time 2—simultaneously relying on family-level weights to account for classification uncertainty—results revealed that toddlers of parents in the High Learning Support profile displayed the highest levels of self-control at Time 2. On average, toddlers of parents in the High Learning Support profile received scores on self-control that were 1.32 SDs higher than scores of toddlers of parents in the Lower Learning Support/Lower Responsiveness profile, p < .001; .86 SDs higher than scores of toddlers of parents in the Moderate Learning Support/Moderate Responsiveness profile, p < .001; and .98 SDs higher than scores of toddlers of parents in the High Responsiveness profile, p = .004. These three differences in means still would be statistically significant with a Bonferroni correction for the false positive rate (p < [.05/6] = .008 for six comparisons) or a more appropriate Benjamini-Hochberg control of the false discovery rate (p < .05 * [3/6] = .025, for a false discovery rate of .05 for the three of six comparisons with the largest differences; Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995; Glickman et al., 2014). There were no statistically significant differences in self-control among toddlers of parents in the Lower Learning Support/Lower Responsiveness, Moderate Learning Support/Moderate Responsiveness, and High Responsiveness profiles. The means of toddlers’ self-control across each of the four parenting profiles are presented at the bottom of Table 4.

Robustness of Results

When a series of covariates representing child, parent, and family characteristics were added to the latent profile analysis to assess the robustness of results to possible confounding—again using the manual three-step BCH method—there were few substantial differences in the pattern of relations between parenting profiles and toddlers’ self-control. Most important, when toddlers’ self-control at Time 1 was controlled, toddlers of parents in the High Learning Support profile received scores on self-control at Time 2 that were 1.04 SDs higher than scores of toddlers of parents in the Lower Learning Support/Lower Responsiveness profile, p < .001; .78 SDs higher than scores of toddlers of parents in the Moderate Learning Support/Moderate Responsiveness profile, p = .006; and .79 SDs higher than scores of toddlers of parents in the High Responsiveness profile, p = .012. Once again, there were no statistically significant differences in self-control among toddlers of parents in the Lower Learning Support/Lower Responsiveness, Moderate Learning Support/Moderate Responsiveness, and High Responsiveness profiles.

Likewise, when child impulsiveness, mastery motivation, and social competence (that included aspects of emotion regulation) were controlled, one by one, the same pattern of finding emerged, with significant mean differences in self-control at Time 2 between toddlers of parents in the High Learning Support profile and the other three parenting profiles, but no differences among toddlers of parents in the other three profiles. When indicators of parent and family functioning, including parent depression, parenting stresses, household chaos, and need for case management or therapeutic support services, were each controlled, one by one, the same pattern of significant and nonsignificant mean differences emerged. In addition, when family demographic characteristics, including child age, family race and ethnicity, parent education, parent employment outside the home, family size, and financial strain, were each controlled, one by one, the same pattern of significant and nonsignificant mean differences emerged. Only child gender and parent relationship status appeared to change results. Subgroup analyses, based on very small groups of families, suggested that families with boys and families with single parents followed the familiar pattern of findings, with significant mean differences in self-control at Time 2 between toddlers of parents in the High Learning Support profile and the other three parenting profiles, but no differences among toddlers of parents in the other three profiles. However, for families with girls and families with two parents, toddlers of parents in both the High Learning Support and the Moderate Learning Support/Moderate Responsiveness profiles received scores on self-control at Time 2 that were statistically significantly higher than the scores of toddlers of parents in the Lower Learning Support/Lower Responsiveness profile, but no other statistically significant differences. Results of all analyses involving covariates are presented in the online supplemental materials.

Discussion

This study examined relations between profiles of parenting behaviors and toddlers’ self-control among families living in poverty. It contributes to our understanding of what kinds of parent–child interactions are associated with toddlers’ functioning in this critically important domain of development during this sensitive period.

Heterogeneity of Parenting in the Context of Poverty

This study highlights the heterogeneity in parenting behaviors among families living in poverty. A person-oriented approach examining patterns among teaching, technical scaffolding, teamwork, instructions, choices, language use, specific praise, and warmth during parent–child interactions revealed four parenting profiles. Parents in the Lower Learning Support/Lower Responsiveness profile were characterized by lower-than-average scores, for this sample, on most parenting behaviors, and parents in the Moderate Learning Support/Moderate Responsiveness profile were characterized by average scores, for this sample, on all parenting behaviors. Parents in both the High Responsiveness and High Learning Support profiles were characterized by higher-than-average scores on almost all parenting behaviors. In terms of statistical significance, they were similar in teaching, technical scaffolding, instructions, choices, language use, and warmth, but parents in the High Responsiveness profile displayed higher rates of specific praise, and parents in the High Learning Support profile displayed higher rates of teamwork.

There is a great need to understand those parents who display resilience as they manage economic hardships and provide the kind of caregiving that best supports their children’s development (Carpenter & Mendez, 2013; McWayne et al., 2012). The parents in the High Responsiveness profile appeared to be very positive and reinforcing when interacting with their toddlers, providing the most specific praise on average of any group of parents. They engaged in above average teaching, technical scaffolding, and teamwork, but seemed to be less directive, uttering relatively few instructions during parent–child interactions, and letting their toddlers determine how activities unfolded. In contrast, parents in the High Learning Support profile appeared equally warm, but may have been more directive, uttering relatively more instructions. Based on their patterns of scores on the parenting behaviors, the parents in the High Learning Support profile appeared more adept at embedding relatively high levels of teaching, technical scaffolding, and teamwork during somewhat routine play activities.

The nature of our parenting profiles was similar to those found in previous research. For example, in their study of parents of toddlers living in poverty, Cook et al. (2012) identified two profiles similar to our Lower Learning Support/Lower Responsiveness profile, which they labeled “Negative Parenting” and “Unsupportive Parenting” and were characterized by below-average levels of parenting behaviors, such as cognitive stimulation, teaching, sensitivity, and warmth. They identified another profile similar to our High Responsiveness and our High Learning Support profiles, which they labeled “Developmental Parenting” and was characterized by above average levels of cognitive stimulation, teaching, sensitivity, and warmth. In her study of low-income Black single mothers, McGroder (2000) found one parenting profile similar to our High Responsiveness profile, which she labeled “Patient and Nurturing” and was characterized by high levels of nurturance but lower levels of cognitive stimulation and aggravation. She also found a parenting profile similar to our High Learning Support profile, which she labeled “Cognitively Stimulating” and was characterized by high levels of cognitive stimulation, average levels of nurturance, and low levels of aggravation. In that study, children of parents in both the Patient and Nurturing and Cognitively Stimulating profiles displayed comparable school readiness. In the present study, although parents in both the High Responsiveness and High Learning Support profiles appeared quite positive overall, albeit in different ways, relations to toddlers’ self-control were quite different.

Parenting Profiles and Toddlers’ Self-Control

This study found that toddlers with parents in the High Learning Support profile demonstrated greater self-control over time, compared with toddlers of parents in the Lower Learning Support/Lower Responsiveness, Moderate Learning Support/Moderate Responsiveness, and even High Responsiveness profiles. This was true controlling for initial levels of self-control, as well as multiple other child, parent, and family characteristics that could have affected both parenting behaviors and toddlers’ self-control. Subgroup analyses suggest this was especially true for families with boys and families with a single parent. Further highlighting the potential importance of what parents in the High Learning Support profile were specifically doing, the toddlers of parents in the High Responsiveness profile did not demonstrate greater self-control than the toddlers of parents in either the Lower Learning Support/Lower Responsiveness or Moderate Learning Support/Moderate Responsiveness profiles. This pattern of findings suggests that providing high levels of learning support may be critical to toddlers’ self-control, and simply being responsive may not be sufficient.

Parents’ learning support and cognitive stimulation is related to children’s self-control (Carpenter & Mendez, 2013; Iruka et al., 2018). Although uncertain, the parents in our High Learning Support profile, compared with parents in the other profiles, may have created more opportunities for their toddlers to relish mastering new skills. In the video recordings of parent–child interactions, parents often found opportunities to teach toddlers something new or practice and reinforce something they already were learning, like animal sounds, colors, numbers, and letters. Many of the most positive interactions occurred around parents’ gentle quizzing and toddlers’ pride and satisfaction in demonstrating competence. Some parents helped toddlers notice which features of the task materials, such as block size, were relevant for accomplishing a specific goal, and some parents appeared especially good at knowing how to organize task materials and activities, so toddlers were not overwhelmed. Through such processes, parents in the High Learning Support profile may have enhanced their toddlers’ excitement and motivation to try and persist in doing something that was hard—a central tenet of self-control—and be rewarded for their effort.

Relatedly, parents in the High Learning Support profile may have been more successful in making the novel and challenging tasks fun and engaging. In prior research, both technical scaffolding and parent–child dyadic pleasure were each uniquely related to children’s positive development over time (Fenning & Baker, 2012). Toddlers and young children are going to be more successful when they frame self-control tasks as challenging games, like Simon Says, in which managing attention, tolerating suspense and other strong emotions, and inhibiting impulses are the very goal (Tominey & McClelland, 2011).

It is important to note that parents in the High Learning Support profile engaged in high levels of teaching, technical scaffolding, and teamwork in the presence of relatively high levels of warmth. This combination may be critical for toddlers’ moral internalization and committed compliance (Kochanska, 2002; Laurin & Joussemet, 2017; Nordling et al., 2016). The more engaging and reinforcing interactions with parents are, the more likely it is that toddlers will strive to both please and emulate their parents by following rules.

Finally, parents in our High Learning Support profile may have been especially good at facilitating toddlers’ independent exploration within their zone of proximal development (Vygotsky, 1978). In the video recordings, some parents initially assumed a leading role by demonstrating how to successfully accomplish a task. Quickly, however, the parents allowed their toddlers to take over, while continuing to offer gentle guidance as necessary. When toddlers devised their own creative ways of using materials, parents often chuckled, but followed their toddlers’ lead, rather than correcting them. Although some parents pulled back from active control, they remained observant, so toddlers rarely had to interrupt their own activities to reengage their parents. As a result, toddlers were able to remain focused for long periods of time in pursuit of their self-determined goals. The experience of managing attention and having persistence pay off may help lay the foundation for successful delay of gratification and self-control more broadly.

Strengths and Limitations

In examining relations between parenting profiles and toddlers’ self-control, this study has several strengths. First, it included racially and ethnically diverse families, almost all of whom were living in poverty. It is especially important we understand better how to promote optimal development among children living in poverty to reduce socioeconomic disparities that are established early and entrenched over time (Wagmiller & Adelman, 2009). Second, this study examined self-control during an important period of early development when it may be most malleable (Kochanska et al., 2000; Kopp, 1982). Third, this study relied on observations of multiple parenting behaviors, rather than self-reports that are prone to social desirability (Morsbach & Prinz, 2006). Fourth, latent profile analysis provided a more nuanced understanding of how those parenting behaviors worked together in predicting toddlers’ self-control. Although some of the eight parenting behaviors were correlated with toddlers’ self-control, even the statistically significant correlations were small to moderate in size (i.e., r =.18–.35). In contrast, when the eight parenting behaviors were used as observed indicators of latent profiles, statistically significant relations between the parenting profiles and toddlers’ self-control were quite substantial (i.e., Mdiff =.86–1.32 SDs).

Despite those strengths, several limitations warrant attention. First, this study included only one measure of toddlers’ self-control. Although that measure, snack delay, is one of the best measures of self-control and highly related to other measures (Murray & Kochanska, 2002; Smith-Donald et al., 2007), it would have been preferable to have implemented a comprehensive battery. Second, the final sample consisted of 117 families, which is relatively small. Some parenting profiles did not include many families, and some mean differences that were fairly large in magnitude were not statistically significant. Confidence in these findings will increase when replicated with more families. Third, the parenting behaviors included in this study captured somewhat limited aspects of caregiving. This was mostly due to the nature of the short, fun, and new activities in the parent–child interaction tasks, in which very few harsh or controlling behaviors occurred. In the future, it will be important to incorporate a broader range of parenting behaviors to better understand heterogeneity among families living in poverty. Fourth, almost all the study participants were mothers. It is unclear whether relations between fathers’ parenting behaviors and toddlers’ self-control would be different than what was found here. Fifth, relations between parenting behaviors and toddlers’ self-control are most likely bidirectional (Blair et al., 2014), which we could not account for in this study. Finally, although we controlled for the effects of self-control at Time 1 and multiple other child, parent, and family characteristics, some aspects of the relations between parenting profiles and toddlers’ self-control may reflect additional common factors we did not account for.

Implications and Conclusions

This study inches forward our understanding of what kind of parenting best supports toddlers’ self-control, early in development. Extending prior research, this study highlights the importance of parenting behaviors related to learning support in the presence of warm parent–child interactions.

This study’s findings may inform future family preventive interventions. To date, there are surprisingly few evidence-based preventive interventions that successfully promote toddlers’ self-control (see review by Murray et al., 2015). This study showcases the potential promise of identifying effective means of fostering parents’ learning support. In this way, we may be more successful in reducing poverty-related disparities in critically important domains of children’s development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (National Institutes of Health Grant R01HD081361) to the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Our invaluable community partners for this study included administrators and home visitors from Bedford/Fulton Head Start in Bedord Pennsylvania, Community Progress Council in York Pennsylvania, Community Services for Children in Allentown Pennsylvania, Luzerne County Head Start in Wilkes-Barre Pennsylvania, Next Door in Milwaukee Wisconsin, Reach Dane in Madison Wisconsin, and STEP Inc. in Williamsport Pennsylvania. We are grateful to all of the families who participated in the study. We also wish to thank Doug Hemken of the University of Wisconsin–Madison Social Science Computing Cooperative for his help with statistical analyses. Although this particular study was not preregistered, it was part of a larger clinical trial that was preregistered at clinicaltrials.gov: NCT03958214 (Nix, 2020). For study materials, contact the corresponding author.

Footnotes

Supplemental materials: https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001312.supp

References

- Akaike H (1974). A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 19(6), 716–723. 10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, & Muthén B (2021). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Using the BCH method in Mplus to estimate a distal outcome model and an arbitrary secondary model (Mplus Web Notes, No. 21, Version 11). http://www.statmodel.com/examples/webnotes/webnote21.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, & Hochberg Y (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 57(1), 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL, Domitrovich CE, Nix RL, Gest SD, Welsh JA, Greenberg MT, Blair C, Nelson KE, & Gill S (2008). Promoting academic and social-emotional school readiness: The head start REDI program. Child Development, 79(6), 1802–1817. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01227.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL, Welsh JA, Heinrichs BS, Nix RL, & Mathis ET (2015). Helping Head Start parents promote their children’s kindergarten adjustment: The research-based developmentally informed parent program. Child Development, 86(6), 1877–1891. 10.1111/cdev.12448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindman SW, Pomerantz EM, & Roisman GI (2015). Do children’s executive functions account for associations between early autonomy-supportive parenting and achievement through high school? Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(3), 756–770. 10.1037/edu0000017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingenheimer JB, Brennan RT, & Earls FJ (2005). Firearm violence exposure and serious violent behavior. Science, 308(5726), 1323–1326. 10.1126/science.1110096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Granger DA, Kivlighan KT, Mills-Koonce R, Willoughby M, Greenberg MT, Hibel LC, & Fortunato CK, & The Family Life Project Investigators. (2008). Maternal and child contributions to cortisol response to emotional arousal in young children from low-income, rural communities. Developmental Psychology, 44(4), 1095–1109. 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Raver CC, & Berry DJ, & The Family Life Project Investigators. (2014). Two approaches to estimating the effect of parenting on the development of executive function in early childhood. Developmental Psychology, 50(2), 554–565. 10.1037/a0033647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolck A, Croon MA, & Hagenaars JA (2004). Estimating latent structure models with categorical variables: One-step versus three-step estimators. Political Analysis, 12(1), 3–27. 10.1093/pan/mph001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borden LA, Herman KC, Stormont M, Goel N, Darney D, Reinke WM, & Webster-Stratton C (2014). Latent profile analysis of observed parenting behaviors in a clinic sample. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(5), 731–742. 10.1007/s10802-013-9815-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, & Corwyn RF (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 371–399. 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, & Flor DL (1998). Maternal resources, parenting practices, and child competence in rural, single-parent African American families. Child Development, 69(3), 803–816. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06244.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SM (2005). Developmentally sensitive measures of executive function in preschool children. Developmental Neuropsychology, 28(2), 595–616. 10.1207/s15326942dn2802_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter JL, & Mendez J (2013). Adaptive and challenged parenting among African American mothers: Parenting profiles relate to head start children’s aggression and hyperactivity. Early Education and Development, 24(2), 233–252. 10.1080/10409289.2013.749762 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Jones SM, & Little TD (2003). The Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31(5), 495–514. 10.1023/A:1025449031360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Somerville LH, Gotlib IH, Ayduk O, Franklin NT, Askren MK, Jonides J, Berman MG, Wilson NL, Teslovich T, Glover G, Zayas V, Mischel W, & Shoda Y (2011). Behavioral and neural correlates of delay of gratification 40 years later. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(36), 14998–15003. 10.1073/pnas.1108561108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, & Rogosch FA (2009). Adaptive coping under conditions of extreme stress: Multilevel influences on the determinants of resilience in maltreated children. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2009(124), 47–59. 10.1002/cd.242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, & Wadsworth ME (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 87–127. 10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (1990). The Social Competence Scale, Parent Version. https://fasttrackproject.org/techreport/s/scp

- Cook GA, Roggman LA, & D’zatko K (2012). A person-oriented approach to understanding dimensions of parenting in low-income mothers. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27(4), 582–595. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crnic KA, & Greenberg MT (1990). Minor parenting stresses with young children. Child Development, 61(5), 1628–1637. 10.2307/1130770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Bates JE, & Pettit GS (1990). Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science, 250(4988), 1678–1683. 10.1126/science.2270481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth AL, Tsukayama E, & Kirby TA (2013). Is it really self-control? Examining the predictive power of the delay of gratification task. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(7), 843–855. 10.1177/0146167213482589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, & Klebanov PK (1994). Economic deprivation and early childhood development. Child Development, 65(2), 296–318. 10.2307/1131385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigsti I-M, Zayas V, Mischel W, Shoda Y, Ayduk O, Dadlani MB, Davidson MC, Lawrence Aber J, & Casey BJ (2006). Predicting cognitive control from preschool to late adolescence and young adulthood. Psychological Science, 17(6), 478–484. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01732.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW (2004). The environment of childhood poverty. American Psychologist, 59(2), 77–92. 10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, & Fuller-Rowell TE (2013). Childhood poverty, chronic stress, and young adult working memory: The protective role of self-regulatory capacity. Developmental Science, 16(5), 688–696. 10.1111/desc.12082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, & Schamberg MA (2009). Childhood poverty, chronic stress, and adult working memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106(16), 6545–6549. 10.1073/pnas.0811910106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk A, Kosse F, & Pinger P (2020). Re-revisiting the marshmallow test: A direct comparison of studies by Shoda, Mischel, & Peake (1990) and Watts, Duncan, and Quan (2018). Psychological Science, 31(1), 100–104. 10.1177/0956797619861720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett TW, McNamara JM, & Houston AI (2012). When is it adaptive to be patient? A general framework for evaluating delayed rewards. Behavioural Processes, 89(2), 128–136. 10.1016/j.beproc.2011.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, Greenbaum CW, & Yirmiya N (1999). Mother-infant affect synchrony as an antecedent of the emergence of self-control. Developmental Psychology, 35(1), 223–231. 10.1037/0012-1649.35.1.223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenning RM, & Baker JK (2012). Mother-child interaction and resilience in children with early developmental risk. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(3), 411–420. 10.1037/a0028287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis LA, & Susman EJ (2009). Self-regulation and rapid weight gain in children from age 3 to 12 years. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 163(4), 297–302. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagne JR (2017). Self-control in childhood: A synthesis of perspectives and focus on early development. Child Development Perspectives, 11(2), 127–132. 10.1111/cdep.12223 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gavidia-Payne S, Denny B, Davis K, Francis A, & Jackson M (2015). Parental resilience: A neglected construct in resilience research. Clinical Psychologist, 19(3), 111–121. 10.1111/cp.12053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glickman ME, Rao SR, & Schultz MR (2014). False discovery rate control is a recommended alternative to Bonferroni-type adjustments in health studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(8), 850–857. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart SA, Logan JA, Thompson L, Kovas Y, McLoughlin G, & Petrill SA (2016). A latent profile analysis of math achievement, numerosity, and math anxiety in twins. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(2), 181–193. 10.1037/edu0000045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman C, Crnic KA, & Baker JK (2006). Maternal depression and parenting: Implications for children’s emergent emotion regulation and behavioral functioning. Parenting: Science and Practice, 6(4), 271–295. 10.1207/s15327922par0604_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houck GM, & Lecuyer-Maus EA (2004). Maternal limit setting during toddlerhood, delay of gratification, and behavior problems at age five. Infant Mental Health Journal, 25(1), 28–46. 10.1002/imhj.10083 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CH, & Ensor RA (2009). How do families help or hinder the emergence of early executive function? New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2009(123), 35–50. 10.1002/cd.234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iruka IU, De Marco A, Garrett-Peters P, the, F. L. P., & Key, I. (2018). Profiles of academic/socioemotional competence: Associations with parenting, home, child care, and neighborhood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 54, 1–11. 10.1016/j.appdev.2017.11.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jung T, & Wickrama KA (2008). An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(1), 302–317. 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00054.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G (2002). Committed compliance, moral self, and internalization: A mediational model. Developmental Psychology, 38(3), 339–351. 10.1037/0012-1649.38.3.339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, & Knaack A (2003). Effortful control as a personality characteristic of young children: Antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Personality, 71(6), 1087–1112. 10.1111/1467-6494.7106008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Murray KT, & Harlan ET (2000). Effortful control in early childhood: Continuity and change, antecedents, and implications for social development. Developmental Psychology, 36(2), 220–232. 10.1037/0012-1649.36.2.220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Murray K, Jacques TY, Koenig AL, & Vandegeest KA (1996). Inhibitory control in young children and its role in emerging internalization. Child Development, 67(2), 490–507. 10.2307/1131828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB (1982). Antecedents of self-regulation: A developmental perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18(2), 199–214. 10.1037/0012-1649.18.2.199 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kopystynska O, Spinrad TL, Seay DM, & Eisenberg N (2016). The interplay of maternal sensitivity and gentle control when predicting children’s subsequent academic functioning: Evidence of mediation by effortful control. Developmental Psychology, 52(6), 909–921. 10.1037/dev0000122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurin JC, & Joussemet M (2017). Parental autonomy-supportive practices and toddlers’ rule internalization: A prospective observational study. Motivation and Emotion, 41(5), 562–575. 10.1007/s11031-017-9627-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WS, & Carlson SM (2015). Knowing when to be “rational”: Flexible economic decision making and executive function in preschool children. Child Development, 86(5), 1434–1448. 10.1111/cdev.12401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, Honorado E, & Bush NR (2007). Contextual risk and parenting as predictors of effortful control and social competence in preschool children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 28(1), 40–55. 10.1016/j.appdev.2006.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li-Grining CP (2007). Effortful control among low-income preschoolers in three cities: Stability, change, and individual differences. Developmental Psychology, 43(1), 208–221. 10.1037/0012-1649.43.1.208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheny AP Jr., Wachs TD, Ludwig JL, & Phillips K (1995). Bringing order out of chaos: Psychometric characteristics of the Confusion, Hubbub, and Order scale. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 16(3), 429–444. 10.1016/0193-3973(95)90028-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGroder SM (2000). Parenting among low-income, African American single mothers with preschool-age children: Patterns, predictors, and developmental correlates. Child Development, 71(3), 752–771. 10.1111/1467-8624.00183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC (1998). Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist, 53(2), 185–204. 10.1037/0003-066X.53.2.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil CB, & Hembree-Kigin TL (2010). Parent-child interaction therapy (2nd ed.). Springer. 10.1007/978-0-387-88639-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McWayne CM, Green LE, & Fantuzzo JW (2009). A variable-and person-oriented investigation of preschool competencies and Head Start children’s transition to kindergarten and first grade. Applied Developmental Science, 13(1), 1–15. 10.1080/10888690802606719 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McWayne CM, Hahs-Vaughn DL, Cheung K, & Wright LEG (2012). National profiles of school readiness skills for Head Start children: An investigation of stability and change. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27(4), 668–683. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.10.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merz EC, Landry SH, Zucker TA, Barnes MA, Assel M, Taylor HB, Lonigan CJ, Phillips BM, Clancy-Menchetti J, Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Valiente C, de Villiers J, & Consortium, T. S. R. R. (2016). Parenting predictors of delay inhibition in socioeconomically disadvantaged preschoolers. Infant and Child Development, 25(5), 371–390. 10.1002/icd.1946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe J, & Mischel W (1999). A hot/cool-system analysis of delay of gratification: Dynamics of willpower. Psychological Review, 106(1), 3–19. 10.1037/0033-295X.106.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mischel W, & Ayduk O (2002). Self-regulation in a cognitive-affective personality system: Attentional control in the service of the self. Self and Identity, 1(2), 113–120. 10.1080/152988602317319285 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mischel W, Shoda Y, & Rodriguez MI (1989). Delay of gratification in children. Science, 244(4907), 933–938. 10.1126/science.2658056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, & Friedman NP (2012). The nature and organization of individual differences in executive functions: Four general conclusions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(1), 8–14. 10.1177/0963721411429458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, & Wager TD (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “Frontal Lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41(1), 49–100. 10.1006/cogp.1999.0734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Belsky D, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, Houts R, Poulton R, Roberts BW, Ross S, Sears MR, Thomson WM, & Caspi A (2011). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(7), 2693–2698. 10.1073/pnas.1010076108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morsbach SK, & Prinz RJ (2006). Understanding and improving the validity of self-report of parenting. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 9(1), 1–21. 10.1007/s10567-006-0001-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraven M, & Baumeister RF (2000). Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 247–259. 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray KT, & Kochanska G (2002). Effortful control: Factor structure and relation to externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30(5), 503–514. 10.1023/A:1019821031523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray DW, Rosanbalm K, & Christopoulos C (2015). Self-regulation and toxic stress report 3: A comprehensive review of self-regulation interventions from birth through young adulthood (OPRE Report #2016-2034). Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). [Google Scholar]

- Nix R (2020, February 27). Promoting self-regulation skills and healthy eating habits in early head start. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03958214 [Google Scholar]

- Nordling JK, Boldt LJ, O'Bleness J, & Kochanska G (2016). Effortful control mediates relations between children’s attachment security and their regard for rules of conduct. Social Development, 25(2), 268–284. 10.1111/sode.12139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, & Muthén BO (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(4), 535–569. 10.1080/10705510701575396 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund-Gibson K, Grimm RP, & Masyn KE (2019). Prediction from latent classes: A demonstration of different approaches to include distal outcomes in mixture models. Structural Equation Modeling, 26(6), 967–985. 10.1080/10705511.2019.1590146 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Razza RA, & Raymond K (2013). Associations among maternal behavior, delay of gratification, and school readiness across the early childhood years. Social Development, 22(1), 180–196. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2012.00665.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, & Mirowsky J (2001). Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42(3), 258–276. 10.2307/3090214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ellis LK, & Posner MI (2011). Temperament and self-regulation. In Baumeister RF & Vohs KD (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications (pp. 358–371). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schibli K, Wong K, Hedayati N, & D'Angiulli A (2017). Attending, learning, and socioeconomic disadvantage: Developmental cognitive and social neuroscience of resilience and vulnerability. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1396(1), 19–38. 10.1111/nyas.13369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlam TR, Wilson NL, Shoda Y, Mischel W, & Ayduk O (2013). Preschoolers’ delay of gratification predicts their body mass 30 years later. The Journal of Pediatrics, 162(1), 90–93. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.06.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz G (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. Annals of Statistics, 6(2), 461–464. 10.1214/aos/1176344136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shoda Y, Mischel W, & Peake PK (1990). Predicting adolescent cognitive and self-regulatory competencies from preschool delay of gratification: Identifying diagnostic conditions. Developmental Psychology, 26(6), 978–986. 10.1037/0012-1649.26.6.978 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Slopen N, Fitzmaurice G, Williams DR, & Gilman SE (2010). Poverty, food insecurity, and the behavior for childhood internalizing and externalizing disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(5), 444–452. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Donald R, Raver CC, Hayes T, & Richardson B (2007). Preliminary construct and concurrent validity of the Preschool Self-regulation Assessment (PSRA) for filed-based research. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22(2), 173–187. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sturge-Apple ML, Davies PT, Cicchetti D, Hentges RF, & Coe JL (2017). Family instability and children’s effortful control in the context of poverty: Sometimes a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush. Development and Psychopathology, 29(3), 685–696. 10.1017/S0954579416000407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominey SL, & McClelland MM (2011). Red light, purple light: Findings from a randomized trial using circle games to improve behavioral self-regulation in preschool. Early Education and Development, 22(3), 489–519. 10.1080/10409289.2011.574258 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky LS (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wagmiller RL, & Adelman RM (2009. Childhood and intergenerational poverty: The long-term consequences of growing up poor. National Center for Children in Poverty. [Google Scholar]

- Watts TW, Duncan GJ, & Quan H (2018). Revisiting the marshmallow test: A conceptual replication investigating links between early delay of gratification and later outcomes. Psychological Science, 29(7), 1159–1177. 10.1177/0956797618761661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebe SA, Sheffield T, Nelson JM, Clark CAC, Chevalier N, & Espy KA (2011). The structure of executive function in 3-year-olds. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 108(3), 436–452. 10.1016/j.jecp.2010.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KE, & Berthelsen D (2017). The development of prosocial behaviour in early childhood: Contributions of early parenting and self-regulation. International Journal of Early Childhood, 49(1), 73–94. 10.1007/s13158-017-0185-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]