Abstract

Objective

To study factors associated with systolic blood pressure(SBP) control for patients post-discharge from an ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack(TIA) during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic compared to pre-pandemic periods within the Veterans Health Administration(VHA).

Materials and Methods

We analyzed retrospective data from patients discharged from Emergency Departments or inpatient admissions after an ischemic stroke or TIA. Cohorts consisted of 2,816 patients during March–September 2020 and 11,900 during the same months in 2017-2019. Outcomes included primary care or neurology clinic visits, recorded blood pressure readings and average blood pressure control in the 90-days post-discharge. Random effect logit models were used to compare clinical characteristics of the cohorts and relationships between patient characteristics and outcomes.

Results

The majority (73%) of patients with recorded readings during the COVID-19 period had a mean post-discharge SBP within goal (<140 mmHg); this was slightly lower than the pre-COVID-19 period (78%; p=0.001). Only 38% of the COVID-19 cohort had a recorded SBP in the 90-days post-discharge compared with 83% of patients during the pre-pandemic period (p=0.001). During the pandemic period, 29% did not have follow-up primary care or neurologist visits, and 33% had a phone or video visit without a recorded SBP reading.

Conclusions

Patients with an acute cerebrovascular event during the initial COVID-19 period were less likely to have outpatient visits or blood pressure measurements than during the pre-pandemic period; patients with uncontrolled SBP should be targeted for follow-up hypertension management.

Keywords: COVID-19, Blood pressure control, Ischemic stroke, Transient ischemic attack, Observational cohort

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Patients who have experienced a stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) are at elevated risk for a subsequent stroke, other vascular events, and mortality.1 , 2 Providing high quality, guideline-concordant management of hypertension is an essential strategy for preventing recurrent events.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Effective management of blood pressure relies on timely access to follow-up outpatient care after an index stroke or TIA.

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted access to healthcare in the United States (US) and in other countries.12 The US experienced a decline in hospital admissions for stroke and other conditions.13, 14, 15 There was also a precipitous decline in primary care visits with a shift from in-person to telephone or video visits.16 , 17 Chronic disease management suffered with lower rates of preventive care18 and reduced blood pressure assessment.16 These changes in care management, along with the pandemic itself, likely contributed to the observed reduction in hypertension control rates.19 , 20

As was the case for the US generally, the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on access to care in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the largest integrated healthcare delivery system in the US. The VA experienced reduced emergency admissions, including for stroke and other vascular conditions.21 There was also a general decrease in the number of primary care visits,22 characterized by fewer in-person appointments as well as a marked increase in virtual healthcare including telephone visits.23

Even with these changes in care delivery stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic, the overall quality of inpatient stroke and TIA care did not change in the VA system; a composite measure of seven guideline concordant care processes did not decline significantly when comparing the first nine months of the pandemic (2020) to same nine months a year before (2019).24 However, one of these seven processes of care, post-discharge blood pressure control, appeared to suffer during the pandemic.24 Specifically, the proportion of VA patients with blood pressure control (systolic blood pressure <140 mmHg) in the 90-days post-discharge was significantly lower during the pandemic than before.

The purpose of the present study was to examine in greater depth the decline in systolic blood pressure (SBP) control for stroke and TIA patients in the VA system during the early COVID-19 pandemic period. Hypertension management is affected by access to primary care and neurologist visits because blood pressure measurements are obtained during outpatient visits. The analysis focuses on outpatient primary care and neurology clinic visits for patients with SBP above goal (SBP ≥140 mmHg) at discharge from an index cerebrovascular event as well as comorbid conditions that would make them targets for prioritized follow-up care (e.g., diabetes mellitus). We compared a cohort of patients presenting to VA Medical Centers with an index ischemic stroke or TIA in the initial seven months of the COVID-19 pandemic and a cohort presenting during the same months in previous years.

Methods

Data sources

This analysis relied on data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), which includes a broad range of information from the VA electronic medical record system, known as the Veterans Information Systems and Technology Architecture. This system is used across the VA system nationwide and includes clinical and administrative functionality. The CDW data were used to identify patients with TIA or ischemic stroke who were cared for in the emergency department (ED) or inpatient setting from March 2017 to September 2020. Primary diagnosis codes (International Classification of Diseases Tenth Revision, ICD-10) were used to identify patients with ischemic stroke (ICD-10 I63, I66, I67.89, I97.81, I97.82) and TIA (ICD-10 G45.0, G45.1, G45.8, G45.9, I67.848) during the index ED visit or inpatient admission.3 , 25 , 26 The CDW was also the source of information on other study variables such as comorbidity, outpatient clinic visits, and blood pressure measurements.

The study was approved by the human subjects committee at the Indiana University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board and the Roudebush VAMC Research and Development Committee.

Study cohorts

The sample consisted of patients with an index cerebrovascular event, defined as presenting at the ED or having an inpatient admission for a stroke or TIA. Patients were discharged from their index event during the early months of COVID-19 (March-September 2020) or during the comparison pre-COVID-19 period of March-September 2017-2019. Patients were excluded if they died at discharge, left against medical advice (AMA), transferred to a non-VA inpatient facility, had a history of dialysis, or were hospice/palliative care patients. In addition, patients had to have survived at least 90 days after discharge because the post-discharge blood pressure control metric was based on the average systolic blood pressure in the 90-days post-discharge.

Measures

In line with our prior research27 and landmark studies such as the SPRINT trial,28 we selected systolic blood pressure as our primary outcome. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure measurements were obtained at discharge from the ED or inpatient setting and over the 90-days post-discharge from VA outpatient medicine and neurology clinics (e.g., primary care, cardiology, endocrinology, nephrology, neurology) that are the main settings in the VA for hypertension care management (these clinics are referred to in the text and tables as “outpatient clinic visits” for ease of communication). We excluded BP measurements during ED visits, inpatient stays, and visits to specialty clinics (e.g., podiatry) because these measurements were less likely to reflect blood pressure under normal conditions and hence unlikely to be the target of routine hypertension management. If a patient had multiple blood pressure readings recorded during a visit, then we used the last reading for the analysis. If a patient had blood pressure readings from multiple visits during the 90-day period, then we calculated the mean SBP recorded over the multiple visits.

Additional variables in the analysis included whether the index event was a stroke versus TIA; inpatient admission versus discharge from the ED; APACHE score (a measure of physiologic disease severity); Charlson Index at presentation (a measure of comorbidity); age group; black/African American race; history of stroke, and TIA or other comorbid chronic conditions. There were also variables indicating pass rates for six other processes of care measures (brain imaging, carotid artery imaging, anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation, antithrombotics, receipt of high or moderate potency statins, and neurology consultation) for the same patients.24 The two pass rates were percentage of the 6 measures passed and a binary variable for passing all of measures vs. failing one or more. The three primary outcomes for the study were: the presence of one or more outpatient visits in the 90-days post-discharge, presence of blood pressure measurements in the 90-days post-discharge, and mean SBP at goal (<140 mmHg) in the 90 days post-discharge.

Analysis

The first step in the analysis was to compare SBP at discharge, comorbid conditions, and other characteristics of patients presenting in the COVID-19 and pre-COVID-19 periods. Next, we described monthly trends in the three study outcomes. Then we applied random effect logit models, with VA facility as a random effect, to determine the association between patient characteristics and outcomes. We modeled the likelihood of having an outpatient clinic visit, having a SBP measurement among patients with visits, and SBP meeting goal (<140 mmHg) among patients with readings. All analysis was performed with SAS Version 8.0 (SAS Institute). Random effect logit models were estimated with the SAS GLIMMIX procedure.

Results

The sample consisted of 14,716 patients; 11,900 in the pre-COVID-19 period and 2,816 in the COVID-19 period. Table 1 compares characteristics of patients presenting with a stroke or TIA in the COVID-19 period to patients in the pre-COVID-19 period in the 90 days after discharge. Most characteristics of stroke and TIA patients presenting during the COVID-19 period were not significantly different than during the pre-COVID-19 period. When differences were significant, they were relatively small from a clinical perspective. For example, patients during the COVID-19 period were more likely to present with a stroke rather than a TIA (66% vs. 64%, p=0.014), be admitted to an inpatient unit (86% vs. 84%, p=0.036), and pass on a higher percentage of other quality indicators (87% vs. 85%, p=0.001). Patients during the COVID-19 period had a lower mean APACHE score (9.70 vs. 10.02, p=0.001); and were less like to have a history of TIA (24% vs. 26%, p=0.019) or atrial fibrillation (13% vs. 15%, p=0.013).

Table 1.

Systolic blood pressure and other characteristics of ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA) patients: pre-COVID-19 versus COVID-19 periods*

| Patient Characteristics | Pre-COVID-19 Period (N=11,900) |

COVID-19 Period (N=2,816) |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % or Mean | Standard Deviation | % or Mean | Standard Deviation | ||

| Admit to inpatient ward (versus ED-only) | 84% | 86% | 0.036 | ||

| Index event: Stroke (versus TIA) | 64% | 66% | 0.014 | ||

| Age: <65 years | 29% | 28% | 0.315 | ||

| Age: ≥89 years | 19% | 18% | 0.551 | ||

| Black/African American | 26% | 25% | 0.455 | ||

| APACHE score | 10.02 | 6.47 | 9.70 | 6.10 | 0.001 |

| Charlson score | 2.53 | 2.53 | 2.38 | 2.47 | 0.137 |

| Congestive heart failure or myocardial infarction on presentation | 5% | 5% | 0.340 | ||

| Past Medical History | |||||

| Hypertension | 80% | 79% | 0.580 | ||

| Transient Ischemic Attack | 26% | 24% | 0.019 | ||

| Stroke | 56% | 57% | 0.445 | ||

| Diabetes Mellitus | 43% | 43% | 0.721 | ||

| Atrial Fibrillation | 15% | 13% | 0.013 | ||

| Myocardial Infarction | 7% | 8% | 0.083 | ||

| Congestive Heart Failure | 14% | 13% | 0.189 | ||

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 20% | 19% | 0.691 | ||

| Peripheral Arterial Disease | 14% | 13% | 0.046 | ||

| Dementia | 8% | 7% | 0.057 | ||

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 17% | 18% | 0.057 | ||

| Cancer | 10% | 10% | 0.936 | ||

| Hyperlipidemia | 64% | 66% | 0.061 | ||

| Sleep apnea | 18% | 20% | 0.050 | ||

| Liver Disease | 6% | 6% | 0.248 | ||

| Migraine | 3% | 4% | 0.270 | ||

| Passing Quality Indicators: % | 85% | 20% | 87% | 19% | 0.041 |

| Passed all Quality Indicators: (yes/no) % | 53% | 59% | |||

| Outpatient clinic visit within 90 days of discharge⁎⁎ | 92% | 71% | < 0.001 | ||

| SBP‡ measurement present: among all patients | 83% | 38% | < 0.001 | ||

| SBP‡ measurement present: among patients with an outpatient clinic visit†⁎⁎ | 91% | 54% | < 0.001 | ||

| Mean SBP‡ at discharge from index event | 138.37 | 19.96 | 139.15 | 19.88 | 0.953 |

| Mean DBP‡ at discharge from index event | 78.28 | 11.33 | 78.62 | 10.91 | 0.051 |

| Discharge SBP‡ <140 mmHg | 55% | 52% | 0.002 | ||

| 90-Day SBP‡ <140 mmHg: among all patients | 65% | 28% | < 0.001 | ||

| Mean 90-day SBP‡ for patients with BP measurements§ | 130.02 | 15.1 | 131.43 | 17.0 | < 0.001 |

| Mean 90-day DBP‡ for patients with BP measurements§ | 74.61 | 9.29 | 75.92 | 9.82 | <0.001 |

| 90-Day SBP‡ <140 mmHg for patients with BP measurements | 78% | 73% | 0.001 | ||

The COVID-19 period was March-September 2020; the pre-COVID-19 period was March-September 2017-2019.

Denominators: Pre-COVID-19 period, N=10,899; COVID-19 period, N=1,993; Total, N=12,892.

Denominators: Pre-COVID-19 period, N=10,899; COVID-19 period, N=9,931; Total, N=11,013.

The outpatient clinics that were included are the main settings in the VA for hypertension care management (e.g., primary care, cardiology, endocrinology, neurology).

SBP refers to systolic blood pressure; DBP refers to diastolic blood pressure.

Patients in the COVID-19 period were much less likely to have an outpatient visit or recorded SBP reading. Only 38% of all patients during the COVID-19 period had a recorded SBP measurement in the 90-days post-discharge, whereas during the pre-COVID-19 period 83% of all patients had a recorded SBP measurement. The proportion of patients with an outpatient clinic visit was lower during the COVID-19 period (71% vs. 92%, p=0.001). Among patients with an outpatient clinic visit, the proportion with a recorded SBP was lower during the COVID-19 period (54% vs. 91%, p=0.001).

Although the mean SBP at discharge did not differ between periods, a lower proportion of patients met the SBP goal of <140 mmHg at discharge during the COVID-19 period (52% vs. 55%, p=0.002). In the 90 days post-discharge, patients in the COVID-19 period had a modestly higher mean SBP (131.43 mmHg vs. 130.02 mmHg, p=0.001) and a lower proportion of patients met the SBP goal of <140 mmHg (73% vs. 78%, p=0.001). Diastolic blood pressure (DBP) followed a similar pattern with no significant difference between periods in mean DBP at discharge, a decline in mean DBP between discharge and the following 90 days during both periods, and significantly higher mean DBP during the COVID-19 period compared to the pre-COVID-19 period.

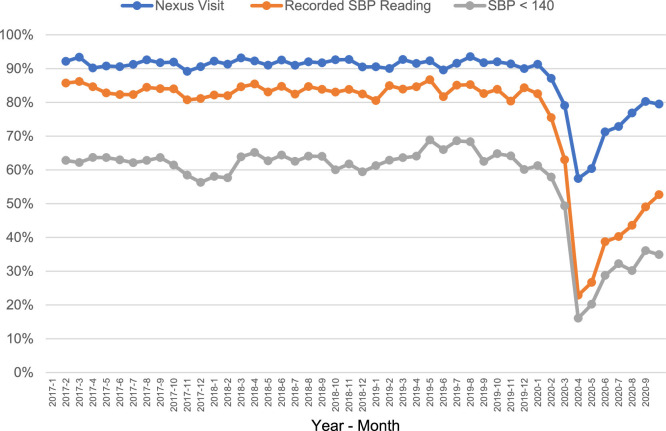

Detailed monthly trends in percentages of patients with outpatient clinic visits, recorded SBP measurements, and SBP <140 mmHg are presented in Figure 1 . Percentages are based on patients discharged from March 2017 to September 2020. The trends held steady for discharges through December 2019. In that month, 91% of discharged patients had an outpatient clinic visit over the following 90 days, 83% had recorded SBP readings, and 61% had a SBP <140 mmHg. A precipitous drop in discharges followed for January through March 2020, reaching a low in March 2020 of 57% of patients with outpatient clinic visits, 23% with a recorded SBP and 16% with a SBP <140 mmHg. By September 2020 the percentages had rebounded somewhat: 79% of patients had an outpatient clinic visit, 53% had a recorded SBP and 35% had a SBP <140 mmHg. It is noteworthy that the percentage of patients with SBP <140 mmHg among those who had an outpatient clinic visit and a SBP reading remained relatively steady at 77% for January 2020 discharges, 70% for March 2020 discharges and 66% for September 2020 discharges.

Figure 1.

Outpatient clinic visits, systolic blood pressure (SBP) measurements, and SBP control (<140 mmHg) within 90 days post-discharge over time

Figure Legend: The outpatient clinic visits that were included are those where blood pressure measurements are taken and acted upon (e.g., primary care) and excludes clinics where blood pressure measurements may not be taken (e.g., optometry).

Logit models for outcomes of outpatient clinic visits, SBP readings, and SBP control are presented in Table 2 . Patients discharged during the COVID-19 period, as opposed to the pre-COVID-19 period, were much less likely to have an outpatient clinic visit (OR=0.206, p <.001)) or a recorded SBP measurement (OR=0.010, p < .001), but they were only slightly less likely to have a SBP below a goal of <140 mmHg (OR=.808, p=.054). Several patient characteristics were also significantly related to one or more outcomes.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics amongst subsamples with outpatient visits, systolic blood pressure measurements, and blood pressure at goal.

| Patient Characteristics | Outpatient Clinic Visit* (N=14,716) |

SBP Measurement# (n=12,892) |

SBP < 140 mmHg (n=11,013) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Limits | P-value | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Limits | P-value | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Limits | P-value | ||||

| Admit to inpatient ward (versus ED-only) | 1.007 | 0.828 | 1.225 | 0.950 | 0.986 | 0.803 | 1.212 | 0.897 | 1.057 | 0.882 | 1.266 | 0.548 |

| Index event: Stroke (versus TIA) | 1.208 | 0.998 | 1.461 | 0.052 | 1.032 | 0.843 | 1.263 | 0.761 | 0.873 | 0.73 | 1.042 | 0.133 |

| Age: <65 years | 0.965 | 0.851 | 1.094 | 0.577 | 0.868 | 0.762 | 0.989 | 0.034 | 1.242 | 1.107 | 1.393 | 0.000 |

| Age: ≥89 years | 0.854 | 0.741 | 0.985 | 0.030 | 0.883 | 0.759 | 1.026 | 0.104 | 0.936 | 0.823 | 1.064 | 0.310 |

| Black/African American | 0.86 | 0.758 | 0.976 | 0.020 | 0.916 | 0.8 | 1.05 | 0.207 | 0.921 | 0.82 | 1.035 | 0.168 |

| APACHE score | 0.997 | 0.988 | 1.007 | 0.584 | 0.989 | 0.98 | 0.998 | 0.018 | 0.969 | 0.962 | 0.977 | <0.001 |

| Charlson score | 1.075 | 1.04 | 1.112 | <0.001 | 0.948 | 0.919 | 0.978 | 0.001 | 1.02 | 0.991 | 1.049 | 0.183 |

| History of Transient Ischemic Attack | 1.096 | 0.904 | 1.329 | 0.351 | 1.104 | 0.904 | 1.348 | 0.333 | 0.956 | 0.802 | 1.138 | 0.611 |

| History of Stroke | 0.994 | 0.846 | 1.167 | 0.937 | 0.825 | 0.7 | 0.972 | 0.021 | 1.044 | 0.903 | 1.207 | 0.558 |

| History of Diabetes Mellitus | 1.113 | 0.98 | 1.264 | 0.100 | 1.124 | 0.987 | 1.28 | 0.079 | 0.913 | 0.815 | 1.022 | 0.113 |

| History of Atrial Fibrillation | 1.049 | 0.891 | 1.235 | 0.564 | 0.966 | 0.821 | 1.135 | 0.673 | 1.223 | 1.058 | 1.415 | 0.007 |

| History of Myocardial Infarction | 0.988 | 0.771 | 1.266 | 0.924 | 0.895 | 0.71 | 1.128 | 0.348 | 1.063 | 0.854 | 1.323 | 0.586 |

| History of Congestive Heart Failure | 1.206 | 1.002 | 1.451 | 0.047 | 1.04 | 0.872 | 1.239 | 0.664 | 1.139 | 0.974 | 1.332 | 0.103 |

| History of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 0.927 | 0.805 | 1.067 | 0.290 | 0.952 | 0.827 | 1.097 | 0.498 | 1.166 | 1.026 | 1.325 | 0.019 |

| History of Dementia | 0.616 | 0.513 | 0.739 | <0.001 | 0.607 | 0.502 | 0.734 | <0.001 | 1.168 | 0.962 | 1.417 | 0.117 |

| History of Chronic Kidney Disease | 0.811 | 0.69 | 0.953 | 0.011 | 1.33 | 1.12 | 1.578 | 0.001 | 1.037 | 0.9 | 1.196 | 0.614 |

| History of Hypertension | 0.985 | 0.853 | 1.138 | 0.841 | 1.094 | 0.938 | 1.275 | 0.253 | 0.495 | 0.425 | 0.576 | <0.001 |

| History of Peripheral Arterial Disease | 0.896 | 0.759 | 1.058 | 0.196 | 0.926 | 0.786 | 1.091 | 0.356 | 0.915 | 0.793 | 1.056 | 0.224 |

| History of Cancer | 1.124 | 0.914 | 1.383 | 0.269 | 1.038 | 0.853 | 1.263 | 0.710 | 1.172 | 0.98 | 1.4 | 0.082 |

| History of Sleep Apnea | 1.293 | 1.113 | 1.502 | 0.001 | 1.27 | 1.095 | 1.473 | 0.002 | 1.282 | 1.129 | 1.456 | 0.001 |

| History of Liver Disease | 1.111 | 0.88 | 1.401 | 0.376 | 0.789 | 0.638 | 0.975 | 0.028 | 1.089 | 0.89 | 1.333 | 0.407 |

| History of Arrhythmia | 1.003 | 0.846 | 1.19 | 0.969 | 1.194 | 0.999 | 1.427 | 0.051 | 1.095 | 0.939 | 1.277 | 0.249 |

| History of Migraine | 1.199 | 0.875 | 1.644 | 0.259 | 1.601 | 1.133 | 2.263 | 0.008 | 1.255 | 0.935 | 1.684 | 0.131 |

| History of Hyperlipidemia | 1.222 | 1.084 | 1.378 | 0.001 | 1.113 | 0.98 | 1.264 | 0.099 | 1.18 | 1.057 | 1.318 | 0.003 |

| History of Hemiplegia | 0.86 | 0.764 | 0.969 | 0.013 | 0.838 | 0.743 | 0.946 | 0.004 | 1.044 | 0.939 | 1.161 | 0.423 |

| Passing QIs % | 3.278 | 2.146 | 5.009 | <0.001 | 1.582 | 0.967 | 2.587 | 0.068 | 1.157 | 0.725 | 1.846 | 0.541 |

| Pass all QIs (yes/no) % | 0.94 | 0.795 | 1.113 | 0.473 | 1.24 | 1.035 | 1.485 | 0.019 | 0.99 | 0.841 | 1.166 | 0.903 |

| Discharge SBP < 140 | 0.977 | 0.876 | 1.09 | 0.794 | 0.855 | 0.761 | 0.961 | 0.008 | 2.482 | 2.127 | 2.897 | <0.001 |

| COVID-19 Period⁎⁎ | 0.206 | 0.185 | 0.229 | <0.001 | 0.101 | 0.090 | 0.114 | <0.001 | 0.808 | 0.693 | 0.943 | 0.054 |

The outpatient clinics that were included are the main settings in the VA for hypertension care management (e.g., primary care, cardiology, endocrinology, neurology).

SBP refers to systolic blood pressure.

The COVID-19 period was March-September 2020; the pre-COVID-19 period was March-September 2017-2019.

Patients who were Black/African American, age 80 or older, or had a history of dementia or chronic kidney disease were less likely to have an outpatient clinic visit in the 90 days post-discharge. Patients with a higher Charlson comorbidity score, history of congestive heart failure, hyperlipidemia, or sleep apnea, or met more of the other stroke-related quality indicators were more likely to have an outpatient clinic visit. Neither a history of hypertension nor systolic blood pressure at discharge from the index cerebrovascular event were associated with receiving an outpatient clinic visit in the 90-days post-discharge.

Patients were less likely to have a SBP measurement recorded in the 90-days post-discharge if they were less than age 65, had presented with a higher APACHE or Charlson comorbidity score, had displayed hemiplegia symptoms or had a history of stroke, dementia, or liver disease, or if they had a SBP <140 mmHg at discharge from the index cerebrovascular event. In contrast, patients with a history of chronic kidney disease, sleep apnea, or migraines, or who met all the other stroke-related quality indicators were more likely to have a SBP measurement recorded in the 90-days post-discharge.

Finally, among patients with a blood pressure reading, they were more likely to have an average SBP below 140 mmHg in the 90-days post-discharge if they had an SBP below 140 mmHg at discharge, if they were younger than age 65 years, or had a history of atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), sleep apnea, or hyperlipidemia. Patients were less likely to have an average SBP <140 mmHg in the 90-days post-discharge if they had a history of hypertension or had a higher APACHE score during the index presentation.

Discussion

Overall, only a modest decrement in hypertension control was observed among patients with ischemic stroke or TIA in the 90-days post-discharge from their index cerebrovascular event of ischemic stroke or TIA during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: 78% of patients in the pre-COVID-19 period (versus 73% during the COVID-19 period) had an average SBP within goal (<140 mmHg). However, this comes with an important caveat, in that 62% of patients during the COVID-19 period did not have routine outpatient follow-up visits where blood pressure measurements are recorded, so their SBP is unknown. Furthermore, patients with a history of hypertension or SBP above goal at discharge—clinical indications for timely hypertension follow-up care—were not more likely to have a follow-up visit after discharge from the ED/inpatient setting.

These findings are consistent with other patterns observed during the pandemic, where preventive care was disrupted29 and primary care visits were either delayed or deferred entirely.30 , 31 During the pandemic, prior reports have described reduced HbA1c monitoring among patients with diabetes, as well as decreased blood pressure measurements among patients with hypertension. 32 During the early pandemic period, the VA deployed virtual outpatient visits via telephone or video.33 During those visits, it is possible providers may have discussed blood pressure concerns with their patients; however, vital signs (including blood pressure) were typically only recorded in the electronic medical record system during in-person clinic visits. Recently, the VA has implemented protocols to collect verified blood pressure measurements during video visits. Future studies should examine whether the observed decrement in outpatient visits and blood pressure measurements persists up to the present.

The high rate of missing follow-up blood pressure measurements reported in this study raises major questions about the pandemic's effect on blood pressure control among patients after an acute cerebrovascular event. Given the paramount importance of blood pressure management for secondary stroke prevention, one major implication of this study is that clinicians should consider prioritizing outpatient hypertension care for patients who are post-stroke or TIA, 34 especially patients with either poorly controlled blood pressure prior to the index event or at the time of discharge.27 Investigators should examine the degree to which COVID-19 related disruptions in hypertension management persist among patients with cerebrovascular disease and evaluate how telehealth delivery modalities might ameliorate such disruptions.

Limitations

Our study had several important limitations. First, we had an absence of information about social determinants of health; delivery-system variables such as policies regarding who should receive an in-person visit and under what conditions; use of antihypertensive medication or other treatments; and the patient's perspective on obtaining follow-up care. Second, we used SBP <140 mmHg as the goal for BP care because that was the threshold in the VA during the period of the study. A lower threshold, i.e., SBP <130 mmHg, is becoming the standard goal for high-risk patients, such as those suffering a stroke or TIA. Third, we lacked information about the type of visits, particularly for virtual visits (e.g., whether by phone or video). Fourth, we were unable to track patients beyond the 90-day period of the study to see if absence of primary care visits, missing SBP readings, or SBP above goal made a difference in outcomes, such as long-term mortality or recurrent vascular events. Finally, this study described hypertension care among a largely male population within VA facilities and the results may not generalize to other healthcare systems.

Conclusion

During the initial COVID-19 pandemic period of resource constraints, patients with an acute cerebrovascular event were less likely to have an outpatient visit or blood pressure measurements than during the pre-pandemic period. Patients discharged after a recent stroke or TIA, especially those with uncontrolled SBP, should be targeted for close follow-up hypertension management

Data sharing statement

The data that support the findings of this study must remain on Department of Veterans Affairs servers. Please contact the corresponding author if you are interested in working with these data.

Funding

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Health Services Research & Development Service (HSRD), Expanding Expertise Through E-health Network Development Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI; QUE HX0003205-01). The funding agency had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Greg Arling: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Edward J. Miech: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Laura J. Myers: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Ali Sexson: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Dawn M. Bravata: Funding acquisition, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Acknowledgments

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study received human subjects (institutional review board [IRB]) and VA research and development committee approvals.

Acknowledgements

There are no non-author contributors.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2023.107140.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Bronnum-Hansen H, Davidsen M, Thorvaldsen P, Danish MSG. Long-term survival and causes of death after stroke. Stroke. 2001;32:2131–2136. doi: 10.1161/hs0901.094253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss A, Beloosesky Y, Kenett RS, Grossman E. Systolic blood pressure during acute stroke is associated with functional status and long-term mortality in the elderly. Stroke. 2013;44:2434–2440. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bravata DM, Myers LJ, Homoya B, Miech EJ, Rattray NA, Perkins AJ, Zhang Y, Ferguson J, Myers J, Cheatham AJ, Murphy L, Giacherio B, Kumar M, Cheng E, Levine DA, Sico JJ, Ward MJ, Damush TM. The protocol-guided rapid evaluation of veterans experiencing new transient neurological symptoms (PREVENT) quality improvement program: rationale and methods. BMC neurology. 2019;19:294. doi: 10.1186/s12883-019-1517-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fletcher RD, Amdur RL, Kolodner R, McManus C, Jones R, Faselis C, Kokkinos P, Singh S, Papademetriou V. Blood pressure control among US veterans: a large multiyear analysis of blood pressure data from the Veterans Administration health data repository. Circulation. 2012;125:2462–2468. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.029983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mouradian MS, Majumdar SR, Senthilselvan A, Khan K, Shuaib A. How well are hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and smoking managed after a stroke or transient ischemic attack? Stroke. 2002;33:1656–1659. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000017877.62543.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bravata DM, Myers LJ, Reeves M, Cheng EM, Baye F, Ofner S, Miech EJ, Damush T, Sico JJ, Zillich A, Phipps M, Williams LS, Chaturvedi S, Johanning J, Yu Z, Perkins AJ, Zhang Y, Arling G. Processes of care associated with risk of mortality and recurrent stroke among patients with transient ischemic attack and nonsevere ischemic stroke. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cushman WC, Ford CE, Cutler JA, Margolis KL, Davis BR, Grimm RH, Black HR, Hamilton BP, Holland J, Nwachuku C, Papademetriou V, Probstfield J, Wright JT, Jr., Alderman MH, Weiss RJ, Piller L, Bettencourt J, Walsh SM, Group ACR. Success and predictors of blood pressure control in diverse North American settings: the antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT) J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2002;4:393–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2002.02045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, Bravata DM, Chimowitz MI, Ezekowitz MD, Fang MC, Fisher M, Furie KL, Heck DV, Johnston SC, Kasner SE, Kittner SJ, Mitchell PH, Rich MW, Richardson D, Schwamm LH, Wilson JA. American Heart Association Stroke Council CoC, Stroke Nursing CoCC and Council on Peripheral Vascular D. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:2160–2236. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ovbiagele B, Diener HC, Yusuf S, Martin RH, Cotton D, Vinisko R, Donnan GA, Bath PM, Investigators P. Level of systolic blood pressure within the normal range and risk of recurrent stroke. JAMA. 2011;306:2137–2144. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitagawa K, Yamamoto Y, Arima H, Maeda T, Sunami N, Kanzawa T, Eguchi K, Kamiyama K, Minematsu K, Ueda S, Rakugi H, Ohya Y, Kohro T, Yonemoto K, Okada Y, Higaki J, Tanahashi N, Kimura G, Umemura S, Matsumoto M, Shimamoto K, Ito S, Saruta T, Shimada K, Recurrent Stroke Prevention Clinical Outcome Study G Effect of standard vs intensive blood pressure control on the risk of recurrent stroke: a randomized clinical trial and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2019 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arling G, Perkins A, Myers LJ, Sico JJ, Bravata DM. Blood pressure trajectories and outcomes for veterans presenting at VA medical centers with a stroke or transient ischemic attack. Am J Med. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2022.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moynihan R, Sanders S, Michaleff ZA, Scott AM, Clark J, To EJ, Jones M, Kitchener E, Fox M, Johansson M, Lang E, Duggan A, Scott I, Albarqouni L. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on utilisation of healthcare services: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berkhemer OA, Fransen PS, Beumer D, van den Berg LA, Lingsma HF, Yoo AJ, Schonewille WJ, Vos JA, Nederkoorn PJ, Wermer MJ, van Walderveen MA, Staals J, Hofmeijer J, van Oostayen JA, Lycklama a Nijeholt GJ, Boiten J, Brouwer PA, Emmer BJ, de Bruijn SF, van Dijk LC, Kappelle LJ, Lo RH, van Dijk EJ, de Vries J, de Kort PL, van Rooij WJ, van den Berg JS, van Hasselt BA, Aerden LA, Dallinga RJ, Visser MC, Bot JC, Vroomen PC, Eshghi O, Schreuder TH, Heijboer RJ, Keizer K, Tielbeek AV, den Hertog HM, Gerrits DG, van den Berg-Vos RM, Karas GB, Steyerberg EW, Flach HZ, Marquering HA, Sprengers ME, Jenniskens SF, Beenen LF, van den Berg R, Koudstaal PJ, van Zwam WH, Roos YB, van der Lugt A, van Oostenbrugge RJ, Majoie CB, Dippel DW, Investigators MC. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blecker S, Jones SA, Petrilli CM, Admon AJ, Weerahandi H, Francois F, Horwitz LI. Hospitalizations for chronic disease and acute conditions in the time of COVID-19. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:269–271. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diegoli H, Magalhaes PSC, Martins SCO, Moro CHC, Franca PHC, Safanelli J, Nagel V, Venancio VG, Liberato RB, Longo AL. Decrease in hospital admissions for transient ischemic attack, mild, and moderate stroke during the COVID-19 era. Stroke. 2020;51:2315–2321. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexander GC, Tajanlangit M, Heyward J, Mansour O, Qato DM, Stafford RS. Use and content of primary care office-based vs telemedicine care visits during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel SY, Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Uscher-Pines L, Ganguli I, Barnett ML. Trends in outpatient care delivery and telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:388–391. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wright A, Salazar A, Mirica M, Volk LA, Schiff GD. The invisible epidemic: neglected chronic disease management during COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:2816–2817. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06025-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laffin LJ, Kaufman HW, Chen Z, Niles JK, Arellano AR, Bare LA, Hazen SL. Rise in blood pressure observed among US adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Circulation. 2022;145:235–237. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.057075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah NP, Clare RM, Chiswell K, Navar AM, Shah BR, Peterson ED. Trends of blood pressure control in the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am Heart J. 2022;247:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2021.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baum A, Schwartz MD. Admissions to veterans affairs hospitals for emergency conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324:96–99. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffith KN, Ndugga NJ, Pizer SD. Appointment wait times for specialty care in veterans health administration facilities vs community medical centers. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baum A, Kaboli PJ, Schwartz MD. Reduced In-person and increased telehealth outpatient visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:129–131. doi: 10.7326/M20-3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myers LJ, Perkins AJ, Kilkenny MF, Bravata DM. Quality of care and outcomes for patients with acute ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2022;31 doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2022.106455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arling G, Sico JJ, Reeves MJ, Myers L, Baye F, Bravata DM. Modelling care quality for patients after a transient ischaemic attack within the US Veterans Health Administration. BMJ Open Qual. 2019;8 doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bravata DM, Myers LJ, Cheng E, Reeves M, Baye F, Yu Z, Damush T, Miech EJ, Sico J, Phipps M, Zillich A, Johanning J, Chaturvedi S, Austin C, Ferguson J, Maryfield B, Snow K, Ofner S, Graham G, Rhude R, Williams LS, Arling G. Development and validation of electronic quality measures to assess care for patients with transient ischemic attack and minor ischemic stroke. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10 doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arling G, Perkins A, Myers LJ, Sico JJ, Bravata DM. Blood pressure trajectories and outcomes for veterans presenting at VA Medical Centers with a Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack. Am J Med. 2022;135:889–896. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2022.02.012. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soliman E.Z., Ambrosius W.T., Cushman W.C., Zhang Z.M., Bates J.T., Neyra J.A., Lewis C.E. Effect of intensive blood pressure lowering on left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with hypertension: SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) Circulation. 2017;136(5):440–450. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.028441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laing S, Johnston S. Estimated impact of COVID-19 on preventive care service delivery: an observational cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:1107. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-07131-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khera A, Baum SJ, Gluckman TJ, Gulati M, Martin SS, Michos ED, Navar AM, Taub PR, Toth PP, Virani SS, Wong ND, Shapiro MD. Continuity of care and outpatient management for patients with and at high risk for cardiovascular disease during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scientific statement from the American Society for Preventive Cardiology. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2020;1 doi: 10.1016/j.ajpc.2020.100009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atherly A, Van Den Broek-Altenburg E, Hart V, Gleason K, Carney J. Consumer reported care deferrals due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the role and potential of telemedicine: cross-sectional analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6:e21607. doi: 10.2196/21607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nielsen VM, Song G, Ojamaa LS, Blodgett RP, Rocchio CM, Pennock JN. The COVID-19 pandemic and access to selected ambulatory care services among populations with severely uncontrolled diabetes and hypertension in Massachusetts. Public Health Rep. 2022;137:344–351. doi: 10.1177/00333549211065515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Der-Martirosian C, Wyte-Lake T, Balut M, Chu K, Heyworth L, Leung L, Ziaeian B, Tubbesing S, Mullur R, Dobalian A. Implementation of telehealth services at the US Department of Veterans Affairs During the COVID-19 pandemic: mixed methods study. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5:e29429. doi: 10.2196/29429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kleindorfer DO, Towfighi A, Chaturvedi S, Cockroft KM, Gutierrez J, Lombardi-Hill D, Kamel H, Kernan WN, Kittner SJ, Leira EC, Lennon O, Meschia JF, Nguyen TN, Pollak PM, Santangeli P, Sharrief AZ, Smith SC, Jr., Turan TN, Williams LS. 2021 Guideline for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2021;52:e364–e467. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.