Abstract

Introduction

The 2022 Presidential Address for the Association for Academic Surgery was focused on better understanding the personal and professional challenges faced by surgeons during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

As part of this work, we embarked on a listening tour, inviting surgeons from all over the country to tell us their stories. This led to forming a panel of five selected participants based on how their stories crosscut many of the most prevalent themes during those conversations. Here, we present thematic excerpts of the 2022 presidential panel, intending to capture that moment and challenge surgeons to contribute to an ever-evolving movement that pushes us to unpack some of our greatest areas of discomfort.

Results

We found that, in many ways, the COVID-19 pandemic brought into focus what many surgeons from marginalized groups have historically struggled with. Dominant themes from these conversations included the role of surgery in informing identity, the tensions between personal and professional identity, the consequences of maintaining medicine as an apolitical space, and reflections on initiatives to address inequities. Panelists also reflected on the hope that these conversations are part of a movement that leads to sustained change rather than a passing moment.

Conclusions

The primary goal of this work was to center voices and experiences in a way that challenges us to become comfortable with topics that often cause discomfort, validate experiences, and foster a community that allows us to rethink what and whom we value in surgery. We hope this work serves as a guide to having these conversations in other institutions.

Keywords: Culture change, DEI initiatives, Surgeon identity

Introduction

In July 2021 the Association for Academic Surgery Executive Council held their annual retreat in Detroit, Michigan. In preparation for the retreat, the following question was posed to this group of rising leaders in academic surgery: What questions have the past 18 mo raised for you personally and/or professionally? The following are just a few of the questions that were submitted by these rising leaders. Am I ever going to be successful? Am I going to still be a surgeon in 10 y? How do I go back to the rat race in my career given the freedom given to me to spend time with my family during the pandemic? How do academic surgeons better support colleagues who struggle with burnout and suicidality? What is the value of healthcare professionals beyond the bedside? Will I always have to forgo the myriad identities that make me whole, in order to make myself visible as a surgeon? How do we help others in the situation and remain openly supportive of their struggle?

The vulnerability and honesty in these responses was eye-opening. What was perhaps most striking is that these were the perspectives of academic surgeons, who for all intents and purposes, have “made it”. If these were the experiences and perspectives from those who are often viewed as representing the pinnacle of success, what would the responses be from those still striving to achieve their personal and professional goals? This was the question that led to what could best be described as a listening tour. The hope was that these conversations would provide an invaluable perspective on some of the most pressing challenges facing surgeons during the unprecedented events of the last 2 y. What we found, however, was that, for many, the COVID-19 pandemic simply brought into focus what many surgeons belonging to marginalized groups have historically struggled with. The problems were not new, but the environment and framing were changing.

This experience led to the formation of a panel comprised of five participants from the listening tour. These participants were selected based on how their stories crosscut so many of the themes that were most prevalent during these conversations. The primary purpose of the panel was not to offer solutions but to offer a step toward building a culture of learning by sharing unique experiences, questioning the status quo, and challenging old ways of thinking. The conversation that follows is meant to not only capture that moment but to challenge surgeons to contribute to an ever-evolving movement that pushes us to unpack some of our greatest areas of discomfort.

Michaela Bamdad, MD, MHS (she/her/hers), Ann Arbor.

Brittany K. Bankhead, MD (she/her/hers), Lubbock.

Imani E. McElroy, MD, MPH (she/her/hers), Boston.

Harveshp Mogal, MD, MS (he/him/his), Seattle.

Ruchi Thanawala, MD, MS (she/her/hers), Portland.

Collective Statement

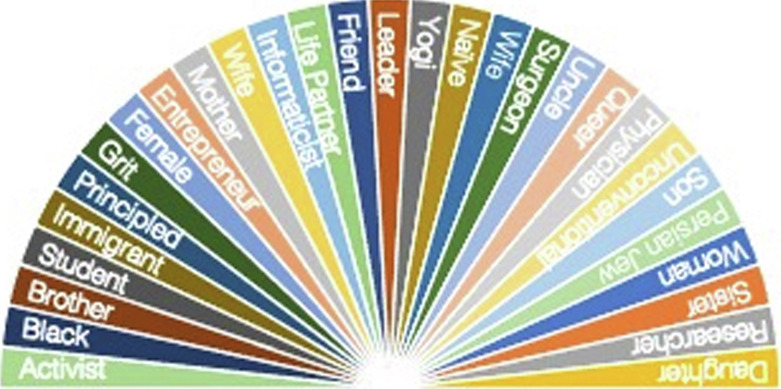

These are our stories. The experiences that helped cultivate our identities (Fig. ). The struggles and celebrations that shape our existence both as individuals and as members of communities we belong to but, most importantly, out truths. We ask that you not judge but listen, for it has taken immense strength, vulnerability, and raw emotion for us to share our personal journeys. Frequently the marginalization has been perpetuated by decades of unchanged surgical culture, these stories are steeped in the hope that you recognize us and others like us as individuals that have meaning and value far beyond the identities we bring to the table and that we move forward as a community in which our intersectional identities are respected, celebrated, and considered worthy of success.

Fig.

AAS panelist identities.

Role of Surgery Informing Identity

Dr Bankhead

Something that I still think about and struggle with, when someone says, ‘What do you do? Who are you?’- Is surgery who I am, or what I do? And if you were to look at a timeline of my day… of my week… how I spend that… it would quickly become evident that it looks like surgery is who I am. I think it's been important to not let it become who we are, and instead something we do. That doesn't make it any less important, it doesn't mean that we don't have a service to our patients in the same way. But I think remembering all these truths about us shows that we have a whole lot more in common and a lot of change to discover, and listen to, than only patients and only surgery.

Dr Thanawala

One of the big things is valuing fluidity and uncertainty. We spend so much of our training trying to manage uncertainty. What's happened over the last one and a half, 2 y is recognizing that we can't turn uncertainty into certainty. And incorporating that into who we are, that it’s okay to be uncertain about where one of the identities fits in, in that moment. And supporting that fluidity that I am someone right now, and I might be someone else in a little bit. And that's okay. That's probably one of the hardest challenges for us. Not only cognitively but in practice. And we're being forced to do that more.

Dr Mogal

The identity of who you are as a surgeon, what value is brought to the table by you as a surgeon, what are the metrics of success that you use to define yourself, is a huge part of what shapes that identity. I think we have built systems overtime that prescribe a certain set of guidelines that tells you what a successful surgeon is. We celebrate people that send emails at 3 AM, or who are taking calls, while on vacation or recouping from illness, or are running the list, while they're actively in labor. Because those are considered the quintessential traits of conscientious, dedicated surgeons. But is this something that is worth celebrating? We struggle with these expectations that we have given so much importance to, in defining our self-worth. And I think the more we pause, think and reset, which the pandemic has given us a lot of opportunity to do, we realize that there is a lot more to us that defines our value and is inseparably linked to our identities as surgeons, but almost always ignored.

Dr McElroy

Personally, for me, I never considered surgery to be my main identity. Because even within surgery my other identities have directly influenced how I practice and interact with my colleagues and patients. Being a Black woman in surgery is not easy. And even within the expectations of what I'm expected to do as a resident and expected to do as a colleague there are all these extra hoops I must jump through. So, I don't have the luxury of even letting surgery define who I am. Because first and foremost to the world, I'm a Black person. And from there I'm a woman or some combination of the two. Thus, my career has never been allowed to define me, if anything, it's something that might save me or make my presence acceptable. Like “oh by the way, I'm a doctor” but even then, that only gives me so many degrees of freedom. So, I think the value of being a surgeon is something that's a life fulfilling career goal. And I'm very pleased with this opportunity to be a surgeon and I understand the privilege that comes with it. But honestly, surgery has forced me into more boxes more than anything else. And I think I've spent the last 2 y in the pandemic very systematically trying to break down and get out of those boxes. I don't know what that will look like 5 y from now. But at least right now I can sit here and be my completely authentic self, which I think for the first time in a long time, or possibly ever, people see me that way. Just now do I think people look me in the face and see me for me, rather than that's one of the Black surgery residents?

Tensions Between Personal and Professional Identity

Dr Bamdad

When one part of your identity is being challenged by another, the assumption is that the part that is doing the challenging is going to win out, right? So, the culture of surgery says you must put me first. You must show devotion to surgery over devotion to everything else, the assumption there is that's going to be what we choose. But I think especially when we've had harrowing experiences, whether health related or otherwise, that the opposite ends up happening. Where you end up valuing the very thing that is being undermined, and you realize that the most important thing in my life is not necessarily being a surgeon but having a healthy, live child at the end of a pregnancy. I think that a couple of us have had that experience and I think it's one of the reasons why becoming a mother and being a mother is such a huge part of my identity and I think I probably think about it more than my mom friends who are accountants or work in HR because it's been challenged. And within that I think there's almost something special about residency babies because of that, that you feel like you must fight for them so much, that they'll just forever be these special little things in your heart.

Dr Thanawala

The toll of asking someone to pick is high, regardless of the outcome. I understand why we focus on outcomes because they're actionable, they're measurable. But the outcome doesn't always relate to the toll. And by asking someone to pick one or the other we're losing the hearts of people, which embody more of what we do daily as surgeons than our technical skill and decision making. It is who we are in the moment where we're taking care of our patients and deciding to come in and to not place that toll on us as people, so we can keep being what we need to be in those moments for our patients and for our families.

Dr McElroy

The idea of having to choose who you are at work versus who you aren't creates a great tension that honestly makes you resent some of the things too. Having to choose between working for someone who is an excellent technician and excellent clinician, but at the same time, you're going to be subjected to mental torture, should not be a choice that we have to make. And I think there's this idea that especially in surgery, the idea that we tolerate things. We have a lot of racial tolerance. I personally don't want to be tolerated. I want to be fully myself and still be able to practice and learn and be able to be treated just like any of my other co-residents. But now I feel like such a big burden to them because it's like, they must switch the culture and change what they believe or be challenged, and have their belief challenged by a resident in a way that makes them uncomfortable. The preference then is that I must choose my own discomfort to not rock the boat and shrink myself. So that choice, that really does make you resent the field in some ways. It's like, I want to be here so badly but you're making it so clear that you don't want me here.

Dr Mogal

The other source of tension is when we're told, this is really all in your head. We embrace you, you're apart of us, we welcome you. Well, why is it that it’s taken me so long to piece parts of these identities together to even feel comfortable expressing them. There's an innate differential in what we perceive, not because we're making this up but because the culture makes us feel that way, that it’s always a choice. That otherness, that feeling that if we choose one identity we will be made to feel even more of an outsider, is always playing in our heads. And a large part of it is where we're at with our culture which has failed to keep up with the progress we have made with the science and the field itself. And the fact that we're sitting here in 2022 talking about this, is not only indicative of how much still needs to be done, but that whatever is being done, doesn't do anything to address what so many of us have been talking about before, during and after the pandemic.

Consequences of Maintaining Medicine as an Apolitical Space

Dr McElroy

Medicine is inherently political. You can't separate the two. I will die on that hill every day. One, the AMA is a lobbying body in the government. We have ways that we go to the government and ask for things as medicine. Two, outcomes that are directly related to what we try to label as genetics or personal failure, that is Black people are higher risk for this or that disease, that's directly related to social determinants of health, which are driven by politics. Our patients not being able to afford medication, our patients not having access to care, that's directly driven by policy and government institutions. In our push to be the best version of ourselves, to be able to care for the most people, we must acknowledge that. We must be better advocates for our patient, if we want to have better outcomes, that means we must step out of our ivory tower and come down and get back into the streets with the people. I think we've siloed ourselves in a lot of different ways and I think that's also why I reject that notion of surgery is who I am. It's not. Because at the end of the day I must walk back out into the world and live amongst people who don't have the same privileges that I do, and I was afforded. So, to be able to back away from medicine and be like, oh we should keep politics out of it is just a way to hide, and not challenge ourselves to be better, to not challenge an unjust system, and most importantly, to not care for other humans. Ludicrous. So, I think there really is no benefit to continuing this false narrative of apoliticallness within medicine. And I think it should be honestly on the forefront of all our minds to directly confront how politics influences everything that we do.

Dr Mogal

I think to expect that our political identities can be completely divorced from our surgical identities is unrealistic. How do you expect the murder of George Floyd not to affect a Black resident in your residency program? And why is the narrative always, well let's train them to be more resilient? When do we stop being apolitical and saying we've got to have a bigger voice out there because this is the environment that we live in? I remember when the Pulse massacre happened, surgical societies were largely silent. Even though close to 50 people lost their lives simply because they shared a common identity. How do you divorce that from who you are as an individual and say, it's our job to take care of patients, so we should be completely divorced from what's happening outside our own academic bubbles in the world, and not let that affect us?

Dr McElroy

I think it goes back to that idea of pushing ourselves back into smaller and smaller pieces. I was that Black resident who was on trauma call the day after George Floyd was killed and the video went viral. I had to come in and take a picture with the rest of my program and then return to my shift in the Emergency Department. I remember the first case I saw was a gastric volvulus for a patient with a hiatal hernia. And I saw the patient, I took care of the patient, but the heaviness that was on my chest that day and to walk around and to have no acknowledgment of this horrific thing that we had just seen, and we knew the entire world saw it because we were in lockdown. So, to have to walk through life and still be expected, and I did my best, to show up and not acknowledge the pain I was feeling. I mean, I did just that. I showed up for my patients and I did everything that I could, but to be expected to not feel that is very different. I think it drives that sense of us not being seen. It was a couple of weeks later, I was operating with another attending at another location, and she was the first attending that in person, reached out and was like, “Hey the world is insane right now, how are you doing?” And I think that was the first time I felt seen in my program as a full individual, as someone who was of value to the program and not a box that was checked or a commodity. Like I know in my heart of hearts my attendings and colleagues care about me in some form. But in that moment, for the first time someone peeled back a curtain, looked me in the eyes and was like, you're dealing with something else that no one else is dealing with and you seem to be on your own with it. In many ways that is the bare minimum what we're asking for. Just acknowledging that something happened and that it was unjust, and people are struggling because we're not siloed individuals. We try as surgeons to compartmentalize, but it's not possible to always do that. And so, by going back to making medicine apolitical and staying out of it, you're functionally silencing a very large portion of your workforce at this point and telling them that it’s not okay to feel. And it's not okay for their differences to be brought into the hospital.

Dr Thanawala

I think apolitical is not in line with apathy, lack of listening and lack of recognition. Sometimes we lump all of those together because we don't want to pick a side. But sometimes there is a right and wrong side. And in an avoidance of picking a side, we don't do anything, we don't acknowledge, we don't appreciate, or we don't mourn. And I think that's where we fall apart in trying to be apolitical because there is a right and wrong many times. And we should be willing to take a risk and commit.

Reflections on Initiatives to Address Inequities

Dr Bamdad

I think without completely veering into the solutions, right? Because that's not the goal and there's no easy way to solve everything, I think that the first thing to address are things that don't help. Gaslighting doesn't help anyone. When somebody comes to you with a concern or with a fear or a feeling that they were treated differently or wrongly or in an unfair manner, acting like it's all in their head is probably not the best move. It's only going to push people away and make people more disenfranchised. I think first realizing when you're diminishing or gaslighting somebody and telling them that it’s not happening and it's not that bad and maybe it was in your head or you took it the wrong way, all that stuff needs to stop. The second thing is realizing when you start to blame the other person. When somebody comes to you with something that needs change, it's really easy to get into defensive mode and not only say that it’s not happening, but if it's happening, it's because it's their fault. Maybe if you had handled it better, maybe if you had said this instead of that, maybe if you had just done this slightly differently then it wouldn't have gone down that way. I think that all those responses really sidestep problems and don't really create a space where people feel like they can bring you areas of growth, areas where we need to grow and where we need to be able to change. I think that within that, having a piece of paper that says what you believe in or what you value isn't the final step, but I do think that it’s an important first step to have on paper, what people can and cannot expect and how we are going to ideally try to navigate certain challenges. I think that creates a situation where it's not a backdoor conversation, it's not all happening in somebody's office with the door closed, and it's not really going to differ too much among different residents. Everybody knows what to expect and how we're going to try to create a better space. We then actually must put our money where our mouth is. That's a whole other thing. But I think that at least starting by establishing in clear writing, this is what we're going to try to do and really engaging the people who have suffered within that space because those are the people that are going to know the areas that need the most change. That's an important first step. Not the final step, but the first step.

Dr Bankhead

I think we have started to create a safe space to voice these adversities and these troubles. You can now say “mental health” without being totally outcast, you can talk about PTSD or suicidality or these things in a mildly more public platform. But what I've seen is-we're okay talking about it… as long as it doesn't impact our clinical box. Like-let's not impinge on that. We can talk about it when there's time, but let's not let it impinge on clinical time to do so. So, this actionable item of creating a safe space of ‘Hey, it sounds like you need counseling, we'll cover afternoon clinic, you go do that’. Or ‘Hey, you need an ultrasound, scrub out, we've got this covered.’ Or even ‘You need a week to go and do this thing, not a problem.’ ‘You need a sick day because you're just distraught about this, that's all right. Patient care moves on, we're here to help, we've got it covered, you take care of you.’ For me, that's the thing that I've seen that's actionable to help the most. It's okay to step away; clinical things will move on.

Dr Mogal

One of the things we also have talked about is that navigating a path in surgery, in academic surgery, is like walking a tightrope. We often see that people who have crossed that tightrope and made it to the other end are celebrated because they've accomplished, they've gone through it. And we heard yesterday I think, the phrase of “getting over it”, you know, getting over yourself, and that's not a helpful narrative to a lot of us because for every person that crosses and makes it on the other side of that tightrope, a lot of people fall. And some of us are fortunate to have safety nets outside of surgery. The other identities that we hold very, very dear, and that are sometimes even more important than us as surgeons. But a lot of people don't have those safety nets. And I think that's a problem with where we are and what we need to do to change culture not only within our institutions but within our societies.

Dr Bamdad

I often think about how many people we've lost and shut out by not creating space. Whether it's medical students who have a bad experience or who see what people go through and decide that they don't want that for themselves. Or if it's residents that drop out, or if it's attendings who leave or pursue other career paths afterward. I think a lot about the people that we lose along the way and what they could have offered. And I probably think about that because that was almost me. I had an unofficial family med spot offer, and I was very close to taking it, and if things hadn't aligned time wise slightly differently and if I hadn't gotten a pep talk that I really needed, who was like, I don't know what's going on, but you're a good resident and you can't leave, okay? It was one of these things that it happened to be passing in the hallway kind of thing. I could have been the person that left residency and it would have not been the right decision for me, but I was close to doing it anyways. And having felt that feeling, I just can't think of how many other people have been there and haven't had the pep talk when they needed it and haven't had the chief resident who pulls you into the call room and says, you're not quitting until you can show me a signed contract to get you through. I think a lot about the people that we close out by not actually creating a space in surgery for them.

Less of a Moment, More of a Movement

Dr Thanawala

My biggest fear is that we'll continue with our transactional interactions where people come to hear someone speak with a list of objectives of what they're going to get out of it and we're going to keep engaging with people because it's transactional and we'll not be willing, like what we've tried to do, to leave our experiences in a space and just leave it there for everyone to think about and let it be. And we'll go back to how it's been of well, what's the point of that. But the point was to leave the story with everyone. I want us to experience these stories. So that's my biggest fear.

Dr Mogal

I think one of my biggest fears is how many times are we going to keep being vulnerable, put ourselves out there and still have nothing change. How many times are we going to keep telling everyone that we feel invisible and yet we continue to stay invisible. I'll just leave it at that.

Dr McElroy

I stepped away from Twitter and into the real world and shared probably more than I've ever shared in my entire life with the hopes of really progressing the field so that nobody else must feel like this. And my biggest fear is waking up tomorrow and we're in this exact, well I know we will, but waking up 10 y from now and looking at a younger version of myself retell the same story and being just absolutely devastated. That it feels like we're doing it for almost nothing.

Dr Bankhead

This is still a forward marching thing, and I worry sitting here too that a future employer, future boss sees what we're talking about, sees that I said the word mental health on a platform- and that becomes what I'm known as. ‘That's the mental health person.’ And that becomes my identity more than the other things that I've done. A lot of us talked about being a mother and what that has meant to us, and I'm a little bit afraid of using my own children as kind of a scapegoat in all of this. Here I am talking about them, but I'm not home with them. And what does that make me? How does that look? I'm not tucking them in tonight, but I'm talking about how much I love them. And that juxtaposition is hard for me. So, I fear that kind of identity crisis is still ongoing.

Dr Bamdad

I think one of the fears that I have is that I worry that people are going to continue to view this as kind of a–when we talk about a cultural problem or systematic problem or anything like that, I think it becomes easy for people to not actually take any personal responsibility. I think that it gets easy for people to look around and be like, oh that's not me, that's not me. I just worry that people aren't necessarily going to introspect on the ways that they're contributing to this daily. Or even if it's just when they slip up. I know there are people who think that they're great advocates who do things to undermine important causes. So instead of looking at this as like a grand problem as the culture of surgery, I just worry that we're not all just going to stop and realize the ways that we contribute to it.

Dr McElroy

I'm sure that this conversation has not been easy to listen to. But really taking a moment to realize that prioritization of your comfort over our discomfort is exactly why we're sitting up here. We really do want you to walk away from this and just think about what was said. Even though it means you must be uncomfortable, understanding that all our humanity is tied to one another, so in the long run, my failure to progress for whatever reason or your patient's death and outcome is directly reflected upon the fact that we're prioritizing our own comfort over the discomfort of others.

Closing Thoughts

We want to stress that the main intent of this process was to begin to learn how we can sit with discomfort and validate these experiences. It remains our collective belief that this is just the beginning. To offer solutions at this point would only perpetuate a cycle of harm on the voices that have historically been underrepresented or marginalized. However, we do understand the value in offering something that “we” as a global community can do next. What we propose is that especially for those in positions of leadership, find the mechanisms in your own institutions to have these conversations. We offer the questions that helped guide this conversation as a starting point (Table ), but it is ultimately up to leaders in the local environment to ensure that conversations like this are not definitive events—rather they are a spark for ongoing dialogue and change. Further, we stress the importance of these conversations happening with significant intention, preferably by someone with experience with participatory approaches, and ensuring that the surgeons being asked to do this work are compensated and considered in the same way as other surgeons asked to participate in Grand Rounds events.

Table.

Question to guide conversations.

| Domains | Questions to guide conversation |

|---|---|

| Identity |

|

| Value |

|

| Well-being |

|

| Moving forward |

|

Author Contributions

Conceptualization of current opinion, critical review and revisions of all drafts, approval of final draft, and agreement for accountability – all authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the participants who shared their stories as part of the Association for Academic Surgery project exploring the challenges facing surgeons during the CoVID-19 pandemic.

Disclosure

Ruchi Thanawala is a cofounder and stakeholder of Firefly Lab. No other disclosures to report.

Funding

None.