Abstract

The goal of this study was to examine whether family involvement and gender moderated daily changes in affect associated with interpersonal stressors. Adults (N = 2022; Mage = 56.25, Median = 56, SD = 12.20, Range = 33–84) from the second wave of the National Study of Daily Experiences participated in eight consecutive daily diaries. Each day they reported whether a daily interpersonal stressor occurred, whether family was involved, and their positive and negative affect. Results from multilevel models indicated that family involvement did not significantly moderate daily interpersonal stressor-affect associations; however, gender was a significant moderator in some instances. Women showed greater increases in negative affective reactivity to arguments and avoided arguments compared to men. Further, compared to men, women reported larger decreases in positive affective reactivity, but only for avoided arguments. Neither family involvement, gender, nor the interaction between family involvement and gender predicted affective residue. Gender differences in daily interpersonal stressors and affective reactivity may be attributable to overarching gender norms and roles that are still salient in the U.S. Our results suggest that daily interpersonal stressors may be detrimental to affective well-being, regardless of family involvement. Future work should explore associations between daily interpersonal stressors and family involvement by specific relationship roles, such as mother or spouse, for a more comprehensive understanding of what stressor characteristics impact daily affective well-being.

Keywords: Interpersonal, daily stress processes, affective reactions, family, gender

Experiences in daily life, including interpersonal experiences, are often innocuous or positive; however, a number are negative (Gunaydin et al., 2016). Indeed, daily stressors involving an individual’s social network —termed interpersonal daily stressors—are the most commonly occurring and distressing type of daily stressor (Almeida, 2005; Bolger et al., 1989; Cichy et al., 2007). Research suggests that these interpersonal daily stressors are associated with poorer physical (Leger et al., 2018), mental (Charles et al., 2013), emotional (Schilling & Diehl, 2014), and cognitive (Stawski et al., 2019) health. One critical mechanism linking daily stress and health occurs through affective responses to a daily stressor, such as an increase in negative affect during or following an argument (e.g., Almeida, 2005; Stawski et al., 2019; Witzel & Stawski, 2021). Considerable research has shown that affective responses to daily stressors, or stressor-related affect, vary within-persons over time (Almeida et al., 2011) and stressor-related affect may persist after the day when stressors occurred (i.e., affective residue; Witzel & Stawski, 2021). Less is known, however, about what stressor characteristics may moderate stressor-affect associations (Witzel & Stawski, 2021). In addition, individual characteristics, such as gender, have explained differential stressor-related affect (Almeida, 2005; Bolger et al., 1989; Stawski et al., 2019) but have not been comprehensively examined in conjunction with stressor characteristics. As such, it is unclear how stressor characteristics and individual characteristics may interact to influence stressor-related affect. One way to address this gap is by examining characteristics of daily stressors – such as who was involved in a daily stressor – and of individuals – such as gender – as moderators of affective responses to daily stressors. The goal of this study was to evaluate whether stressor-related affect associated with interpersonal daily stressors depended on either family involvement (a stressor characteristic), or gender (an individual characteristic), or both.

Conceptual models of daily stress processes and developmental theoretical perspectives imply that adults occupy multiple social roles, which inherently leads to diverse interpersonal experiences and associated stressor-related affect (Almeida, 2005; Elder, 1994; Settersten, 2018). Family relationships are some of the closest relationships individuals have, shaping well-being and development (Settersten, 2018); therefore, interpersonal stressors involving family may produce a stronger affective response than those not involving family. In addition, gender is an important individual characteristic to consider when investigating interpersonal stressors because gender influences stressor-related affect as well as family roles and relationships (Blackstone, 2003). As such, studying family involvement in daily interpersonal stressors necessitates investigating the role of gender as well. Understanding how both stressor characteristics and individual differences influence stressor-related affect could help inform interventions by identifying (a) what type of interpersonal stressors (involving family members or not) might be most impactful to target to reduce negative stressor-affect associations and who (i.e., men or women) might benefit from these interventions.

Daily stress process model

Widely recognized by stress researchers, the daily stress process (DSP) model depicts how daily, routine challenges disrupt daily life, and accumulate to influence longer-term health and well-being (Almeida, 2005). Almeida (2005) acknowledges that daily stressors are not comparable; instead, some daily stressors are more detrimental than others. The DSP model depicts stressor exposure and stressor reactivity as mechanisms linking daily stressors to health and affective well-being. Stressor exposure refers to the likelihood an individual experiences a daily stressor, and stressor reactivity refers to the likelihood that individuals will have an emotional reaction to the stressor exposure. This conceptual model is widely recognized by stress researchers and both exposure and reactivity have been associated with a host of health and well-being outcomes (e.g., Charles et al., 2013; Piazza et al., 2013; Sin et al., 2015; Stawski et al., 2019) and even increased mortality (Chiang et al., 2018). As will be discussed in detail later, the DSP model also delineates both stressor and individual characteristics that can impact stressor-related affect.

Affective reactivity and residue

More recently, research on daily stress processes has highlighted additional dimensions of affective responses to daily stressors complementing stressor reactivity (Smyth et al., 2018; Smyth et al., 2022). Such dimensions, broadly referred to as stressor-related affect and operationalized as changes in affect related to a daily stressor (Stawski et al., 2019), can be reflected by both increased negative affect (NA) and decreased positive affect (PA; Watson, 1988). Further, stressor-related affect is an umbrella term including affective responses over different temporal intervals: same-day (reactivity) and next-day (residue) affective reactions to a stressful experience (Witzel & Stawski, 2021). For example, on a given day, an individual may have an argument with a family member and become angry that same day (reactivity) and continue to be angry the next day (residue).

Affective reactivity is a known mechanism linking daily stress to worse physical (Charles et al., 2013), mental (Piazza et al., 2013), cognitive (Stawski et al., 2019), and biological (Sin et al., 2016) health. Recent research additionally supports examining stressor-related affect into the following day to better understand both proximal and prolonged effects of daily stressors (Smyth & Heron, 2016; Smyth et al., 2022). Indeed, although sparse compared to research on affective reactivity, recent evidence suggests that affective residue is a complementary mechanism linking daily stress to poorer health outcomes including less sleep (Leger et al., 2020) and worse emotional (Leger et al., 2019) and physical (Leger et al., 2018) health. Although the literature on moderators of affective reactivity and residue continues to grow, it is still largely unclear how both stressor characteristics and individual differences moderate affective reactivity and residue.

Daily stressor and individual characteristics of stressor-affect associations

According to the DSP model (Almeida, 2005), both daily stressor characteristics and individual difference characteristics moderate stressor reactivity. First, as mentioned previously, daily stressors and their impact on health and well-being are not invariant (Almeida, 2005). As such, stressor characteristics, including the type of daily stressor (i.e., content) and who was involved in a daily stressor (i.e., focus of involvement), help explain the differential influence of daily stressors on health and well-being. In this study, we examined one type of daily stressor: daily interpersonal stressors. The impact of daily interpersonal stressors on daily affect could additionally vary by who was involved, such as family members. Second, the DSP model recognizes individual differences in exposure and reactivity to daily stressors. Individual difference characteristics, termed resilience and vulnerability factors, such as gender, also modify exposure and affective reactivity to daily stressors. Below we provide our rationale for focusing on daily interpersonal stressors, as well as family involvement and gender as potential moderators, in understanding affective reactivity and residue.

Daily interpersonal stressors

According to life course theory (Elder, 1994), the tenet of linked lives underscores the importance of social relationships and interactions therein for affect, specifically, and development, broadly. Theorists have proposed, for example, that people influence and are influenced by the lives of family and others that they interact with (Settersten, 2015). Social interactions with people occur quite often, with research suggesting that individuals between the ages of 20 and 80 experienced an average of approximately twelve social interactions per day (Zhaoyang et al., 2020). Thus, understanding the context of these interactions, particularly negative social interactions, may provide a deeper understanding of how daily life disrupts daily affective well-being.

These negative social interactions, termed daily interpersonal stressors, are among the most common and distressing type of negative daily experience (Bolger et al., 1989; Charles et al., 2009; Rook, 2001). Indeed, Almeida (2005) reported that daily interpersonal stressors made up 50% of daily stressor events in a sample of 1483 adults. Moreover, evidence suggests that daily interpersonal stressors are nearly twice as emotionally distressing as other types of daily stressors (Bolger et al., 1989) and are uniquely related to both worse daily (Birditt et al., 2005; Cichy et al., 2012; Witzel & Stawski, 2021) and global reports of well-being (Fuentecilla et al., 2020). However, appraisals, de-escalation, and coping associated with interpersonal daily stressors may differ by type of interpersonal daily stressors. As such, and in line with previous research (e.g., Almeida, 2005; Birditt et al., 2005; Charles et al., 2009; Witzel & Stawski, 2021), the current study differentiates daily interpersonal stressors into arguments and avoided arguments. Arguments refer to stressful interactions occurring between two individuals, whereas avoided arguments are negative interpersonal interactions that could have occurred, but did not (Almeida, 2005; Witzel & Stawski, 2021). Both arguments and avoided arguments have previously been uniquely associated with negative and positive affect (e.g., Witzel & Stawski, 2021).

Family involvement as a moderator of stressor-affect associations

The DSP model suggests that the focus of involvement (i.e., who is involved) is one characteristic of daily stressors that may moderate stressor-affect associations. From a life course theoretical perspective, Settersten (2018) acknowledges that family relationships are some of the most intimate and intertangled relationships individuals have. Midlife is a time of expansive family relationships—often individuals are married, are parents, and interact with in-laws, their own parents, and grandparents. Therefore, during midlife, family is a prominent proximal relationship in daily life that influences individual health and well-being (Antonucci, 2001; Bronfenbrenner, 1995; Elder, 1994).

Indeed, research demonstrates that family involvement plays an integral part in the influence stressors have on affective well-being (e.g., Antonucci et al., 1998; Birditt et al., 2005; Cichy et al., 2012) and developmental processes (Elder, 1994). Some extant research has focused specifically on daily family stressors (e.g., Birditt et al., 2005; Cichy et al., 2012). Both Birditt and colleagues (2005) and Cichy and colleagues (2012) explored the impact of interpersonal stressors by whom was involved. Cichy et al. (2012) reported for both White and Black adults, arguments involving family were associated with worse negative affect and positive affect reactivity and worse negative affective residue compared to days when no family stressor occurred. Only affective residue, specifically prolonged elevation of negative affect, was significantly larger for Black adults compared to White adults.

In another study, Birditt et al. (2005) disaggregated family interpersonal stressors by who was involved. Specifically, they explored the impact of who was involved (both family and non-family) in a daily interpersonal stressor on behavioral and emotional reactivity. They conceptualized behavioral reactions as strategies used in reaction to a stressor (i.e., active or passive and constructive or destructive) and referred to emotional reactions as how stressful the experience was. Birditt et al. (2005) compared associations across four distinct categories of individuals involved in the stressor: spouse/partner, child, other family, or non-family. Results suggested that individuals reported more interpersonal tensions with individuals outside the family, followed by spouses or partners. Further, the emotional severity of the stressor varied between categories; interpersonal stressors involving children were associated with more stress compared to interpersonal stressors involving spouses, but there was no clear indication whether severity differed as a function of family involvement compared to non-family involvement. It is additionally important to note that Birditt and colleagues (2005) focused on severity ratings of stressors, not affective reactions (e.g., anger, sadness) reflected in changes affect associated with an interpersonal stressor. Unfortunately, neither study directly compared interpersonal stressors involving non-family members to interpersonal stressors involving family members, so it is unclear whether family involvement differentially impacts stressor-related affect. Thus, our first aim was to assess whether family involvement differentially moderates the association between interpersonal daily stressors and stressor-related affect compared to interpersonal daily stressors not involving family.

Gender as a moderator of stressor-affect associations

Gender is a socially constructed role and structural system that underlies all social interactions and the inequalities therein (Ridgeway & Correll, 2004). Specifically, gender role theories posit that differential experiences between men and women are due to societies,’ groups,’ and individuals’ beliefs, norms, and expectations about gender (Aneshensel & Pearlin, 1987; Blackstone, 2003; Eisend, 2019). As such, gender roles and norms impact health and well-being, and in the DSP model, gender is an individual characteristic proposed to explain vulnerability or resilience to daily stress (Almeida, 2005; Matud, 2004; Verma et al., 2011). Further, Dedovic and colleagues (2009) theorized that differences in the physiological responses to stress through the HPA axis cannot be explained solely through biological means; instead, gender socialization provides a foundation for understanding differences in the daily stress process. As such, gender may moderate associations between daily interpersonal stressors and stressor-related affect. Accordingly, both experimental and naturalistic studies reveal gender differences in exposure (Almeida & Kessler, 1998; Matud, 2004) and biological reactivity (Stroud et al., 2002 in Dedovic et al., 2009) to stress. Almeida and Kessler (1998) found women reported higher frequency of daily stress and a higher frequency of highly stressful days compared to men. Moreover, women reported more family demands, whereas husbands had more frequent arguments with single or multiple others. In addition, Matud (2004) found that while there were few gender differences in life events, women reported more family-related events than men. These associations may highlight the socialization process by which women are socialized in Western cultures to emphasize social integration and social networks compared to men. In addition, women reported more health- and family-related stressful events compared to men (Almeida & Kessler, 1998; Matud, 2004).

Research examining gender differences in affective reactivity to daily stressors has yielded mixed results (e.g., Almeida & Kessler, 1998; Birditt et al., 2005; Matud, 2004). Compared to men, women reported more distress (Almeida & Kessler, 1998; Matud, 2004) and were more affectively reactive (Birditt et al., 2005) on stressor days than non-stressor days; however, other studies have shown gender differences in some indices of stressor-related affect to be non-significant (e.g., Sin et al., 2016). Studies also suggest gender differences in stressor-related affect to daily stressors generally and interpersonal stressors specifically (Almeida & Kessler, 1998; Birditt & Fingerman, 2003). For example, Almeida and Kessler (1998) found that, compared to men, women were more reactive when an interpersonal argument occurred, but did not observe gender differences in staying distressed following a daily stressor (i.e., residue). By contrast, Birditt and Fingerman (2003) found women reported a higher intensity of emotional reactivity and prolonged duration of emotional reactions compared to men. Importantly, these studies differ in several dimensions, including sample demographics, operationalization of stressors, and measures employed, which may account inconsistencies in findings across studies. Almeida and Kessler (1998), for example, operationalized stressors as an exposure to common stressors every day whereas Birditt and Fingerman (2003) asked participants to discuss an emotionally upsetting situation with someone within their close social relationships. Taken together, there is reasonably robust evidence of gender differences in affective reactivity associated with interpersonal daily stressors, but research on and evidence for gender differences in affective residue is comparatively scant. Given the mixed findings regarding gender differences in affective responses to daily stressors, it may be that clarifying the nature of gender differences depends on family involvement in interpersonal daily stressors.

Interaction of family involvement and gender in stressor-affect associations

The life course theoretical perspective highlights the import of gender differences in daily life and development, and researchers (Moen, 2011) have noted that men and women lead different lives resulting from socialized pre-existing schema. These differing lives and pre-existing schema help shape policies and practices that reproduce and re-enforce gender roles within the family. As such, gender shapes the behaviors and roles of family life as well as interactions with family members. Although egalitarian gender role attitudes have increased, traditional gender role behaviors persist in U.S. families as women continue to shoulder family-related demands such as housework, parenting across all stages of child development, and kin work (Perry-Jenkins & Gerstel, 2020). Conversely, traditional and on-going gender roles for men include being the primary breadwinner of the family, responsible for financial and job security (Perry-Jenkins & Gerstel, 2020). Despite changing family expectations, men are still more likely to work overtime and full-time compared to women (Cha & Weeden, 2014).

Gender differences within relationships and social networks have garnered considerable attention in literature. Research suggests that compared to men, women tend to be more relationship-oriented (e.g., Moskowitz et al., 1994), have a larger social network (Antonucci, 1985; Antonucci & Akiyama, 1987), and be more integrated into said social networks (Thomas et al., 2017; Umberson et al., 1996). Further, Zhaoyang et al. (2018) found that across five ecological momentary assessments every day for 7 days, 45% of individuals’ social interactions were with family members, and although this percentage did not differ by gender, it is important to note that they did not examine how these interactions may influence health and well-being. As such, while the number of family interactions may not differ by gender, reactions to daily stressors with family may differ by gender (Birditt & Fingerman, 2003). These differences may be attributable to gender attitudes, identities, and social norms, the overarching cultural beliefs and structures vis-à-vis gender and have implications for men’s and women’s health, with women more vulnerable to stress involving family.

Current study

The current study leveraged the daily diary design of the second wave of the National Study of Daily Experiences (NSDE II) to examine family involvement, as a stressor characteristic, and gender, as an individual difference characteristic, associated with stressor-related affect to interpersonal daily stressors. First, we examined family involvement as a moderator of changes in negative and positive affect associated with interpersonal daily stressors. We predicted that when an interpersonal daily stressor involves family, participants would report increases in stressor-related affect compared to when interpersonal daily stressors do not involve family (H1). Specifically, we predicted that same-day (i.e., affective reactivity) and next-day (i.e., affective residue) changes in negative and positive affect would be larger when daily interpersonal stressors involve family compared to when they do not. Second, we explored the potential gender differences stressor-related affect associated with interpersonal daily stressors. We hypothesized that when interpersonal daily stressors occur, women would report increases stressor-related affect compared to men (H2). Specifically, compared to men, women would exhibit larger same-day (i.e., affective reactivity) and next-day (i.e., affective residue) change in negative and positive affect associated with daily interpersonal stressors. Finally, we examined the interaction between family involvement and gender on the associations between interpersonal daily stressors and stressor-related affect. We hypothesized that women would be more impacted by interpersonal daily stressors when family is involved and less impacted by interpersonal daily stressors when family is not involved compared to men (H3). Specifically, when an interpersonal daily stressor occurs and involves family, women would report larger increases in negative and larger decreases in positive affect in the same-day (i.e., affective reactivity) and next-day (i.e., affective residue) compared to men. Further, when an interpersonal daily stressor occurs and does not involve family, women would report smaller increases in negative and smaller decreases in positive affect in the same-day (i.e., affective reactivity) and next-day (i.e., affective residue) compared to men.

Method

Procedure and participants

We utilized data from the second wave of the National Study of Daily Experiences (NSDE) in the national study of Midlife in the United States (MIDUS; see Almeida, 2005; Cichy et al., 2012; Stawski et al., 2019 for more information). The aim of the MIDUS study is to understand how a variety of factors influence health and well-being as people age from early adulthood into midlife and old age. From 1995 to 1996, approximately 7100 people participated in the first wave of the MIDUS data collection. This baseline sample included individuals from a national random digit dialing sample and over-sampling from five metropolitan areas within the U.S. A subset of the MIDUS project participants also participated in the NSDE (from 1996–1997), an end-of-day diary study that includes eight consecutive days of data obtained via phone interviews.

For the present study, we utilized data from 2022 participants in the second wave of the daily diary component of the MIDUS project: the NSDE II. The NSDE II data collection occurred approximately 10 years after the first wave from 2004 to 2009 (Almeida, 2005). Each of the eight end-of-day phone interviews lasted 10 to 15 minutes, and respondents reported the interpersonal stressors they experienced that day and their affect. Over the 8 days, participants responded to 14,912 of the 16,176 possible daily interviews (92% completion rate). The MIDUS and NSDE data are publicly available (https://www.icpsr.umich.edu) and over three hundred related publications stem from these data (http://midus.wisc.edu/). Participants’ ages ranged from 33–84 (Mage = 56.25, Median = 56, SD = 12.20). See Table 1 for more information pertaining to demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographic information.

| Percent of sample (N = 2022) | |

|---|---|

| Race | |

| White | 83.88 |

| Minority | 16.12 |

| Gender | |

| Men | 42.78 |

| Women | 57.22 |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Straight | 97.16 |

| Lesbian or gay | 1.68 |

| Bisexual | 1.16 |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 72.26 |

| Other | 27.74 |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 36.00 |

| Some college | 46.29 |

| Bachelors or higher | 17.71 |

| Student status | |

| Student (full or part-time) | 0.76 |

| Not student | 99.24 |

| Received disability benefits in past 12 months | |

| Yes | 4.49 |

| No | 95.51 |

Measures

Affect.

Positive and negative affect were measured with twenty-seven items (Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998; Watson et al., 1988). Participants rated how often they felt a certain emotion on a scale of none of the time (0) to all of the time (4). An example of the negative affect items is, “How much of the time today did you feel anxious?” An example of the positive affect items is, “How much of the time today did you feel cheerful?” 14 negative emotion items and 13 positive emotion items were averaged to create negative (αwithin = 0.77, αbetween = 0.97) and positive (αwithin = 0.86, αbetween = 0.99) affective scores for each day (Scott et al., 2020). The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) of the unconditional models were .47 and .67 for negative and positive affect, respectively.

Interpersonal stressors.

The Daily Inventory of Stressful Events (DISE; Almeida & Kessler, 1998; Almeida et al., 2002) provided information on interpersonal daily stressors. The DISE is a semi-structured measure consisting of probe questions for daily stressors. Initially, participants reported if a specific type of negative event (e.g., argument, work, network stressor) occurred within the last 24 hours or since the last time they were contacted. The different stressors were coded as the daily stressor did not occur (0) or the specific daily stressor did occur (1). For our purposes, we only utilize data from items probing experiences of arguments and avoided arguments. The item for arguments was, “Did you have an argument or disagreement with anyone since (this time/we spoke) yesterday?” For avoided arguments, participants were asked, “Since (this time/we spoke) yesterday, did anything happen that you could have argued about, but you decided to let pass in order to avoid a disagreement?”

Family involvement.

If a daily stressor occurred, participants were asked the following, “Think of the most stressful (type of stressor here) you had since yesterday. Who was that with?” The participant reported one person the event included, and the item was coded from spouse or partner [including ex-] (1), to no one else was involved (25). For the purposes of this study, who is involved was coded as no family was involved (0), or family was involved (1). The family members included in family involvement were spouse or partner, child or grandchild, parent, sibling, general family, or other relative.

Gender.

Gender was assessed with one question; participants indicated whether they were a man (1) or woman (2). No other genders were indicated.

Covariates.

Marital status (married or not), age, race (White or other), education (high school/GED or less, some college, bachelor’s degree or more), day in study (1–8), and day of week (weekday or weekend) were included as covariates given their relationships to daily stressor-affect associations (Almeida & Horn, 2004; Almeida, 2005; Stawski et al., 2019).

Analytic strategy

We utilized multilevel modeling due to the clustered nature of the data and to allow for time-varying associations among the interpersonal daily stressors and affect. Analyses utilized maximum likelihood estimation in SAS PROC MIXED v.9.4 (SAS Institute, 2013). We ran separate models for predicting daily negative and positive affect; both arguments and avoided arguments were included in the models simultaneously. Each model covaried for marital status, age, race, education, day in study, and day of week.

| (1) |

The above equation (equation (1)) is an example of the models employed and, for brevity, does not include parameters for covariates. The intercept (b00) reflects level of affect on days when neither arguments nor avoided arguments were reported. Affective reactivity was represented by the time-varying effects of current day arguments (b01) and avoided arguments (b05). Affective residue was similarly represented by time-varying effects, but for previous-day arguments and avoided arguments (b02 & b06, respectively). b03 and b07 represent the slope parameters for the time-varying associations of same-day arguments and avoided arguments involving family where an individual’s change in negative or positive affect depend on whether the stressor involved a family member. Of note, family involvement was a measure that only occurs when a daily stressor has also occurred, as such, the inclusion of the variable indicates its moderating status. b04 and b08 represent similar family involvement effects, but for previous day arguments and avoided arguments involving family.

Three primary models included the time varying slopes representing the main effects of family involvement and/or gender and the interactions between family involvement and gender. Two models per affect valance were utilized and augmented from equation (1) for each research question. Variables at level 1 (i.e., variables that vary across days) included same day and previous day arguments and avoided arguments, family involvement in both arguments and avoided arguments, day of week, and day in study. Level 2 variables (i.e., person-level variables that are invariant) including person-mean frequencies of arguments and avoided arguments across 8 days, gender, marital status, age, race, and education. Two models were run for each hypothesis; models for negative affect are noted in in the first three models in Table 2 and models for positive affect are noted in the second three models in Table 2. Models 1 and 2 detail the moderating effects of gender and family involvement separately for both negative and positive affect. Model 3 examines the interaction between gender and family involvement on interpersonal daily stressor-affect associations. Model fit (seen in Table 2) is indicated by lower −2LLs and BICs. Nested model comparisons were evaluated using likelihood ratio Chi-square tests based on changes in −2LLs and parameters estimated. While Model 3 resulted in lower −2LL, indicative of better model fit relative to Models 1 and 2, there was minimal evidence suggesting this change in model fit was statistically significant. Importantly, none of the family involvement by gender interactions were statistically significant. As such, and to maintain consistency in interpretation for hypotheses 1 and 2, our interpretations focused on the unique effects of family involvement and gender respectively indicated by Models 1 and 2 in Table 2. Of note, the significance and patterning of results was not impacted by this decision.

Table 2.

Multi-level model parameter estimates for stressor-related affect associated with daily interpersonal stressors by family involvement and gender.

| Negative affect | Positive affect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 2a | Model 3a | Model 1b | Model 2b | Model 3b | |

| Model fit | ||||||

| −2LL | 6326.40 | 6316.70 | 6308.30 | 20,938.80 | 20,928.70 | 20,924.40 |

| Covariance parameters | 20 | 20 | 28 | 20 | 20 | 28 |

| BIC | 6285.80 | 6476.10 | 6366.40 | 21,098.30 | 21,088.10 | 21,144.60 |

| Δ −2LL | 106.4 | 132.70 | 18.1/8.4 | 1.1 | 11.20 | 14.4/4.3 |

| Δ Parameters | 5 | 5 | 8/8 | 5 | 5 | 8/8 |

| Fixed Parameter estimates | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.06 (0.02)* | 0.05 (0.02)* | 0.01 (0.02) | 3.04 (0.06)*** | 3.03 (0.06)*** | 3.03 (0.06)*** |

| Person mean arguments | 0.21 (0.05)*** | 0.21 (0.05)*** | 0.21 (0.05) *** | −0.55 (0.13)*** | −0.55 (0.13)*** | −0.55 (0.13)** |

| Person mean avoided arguments | 0.37 (0.05)*** | 0.37 (0.04)*** | 0.37 (0.04) *** | −0.67 (0.11)*** | −0.67 (0.11)*** | −0.67 (0.11)** |

| Gender main effect | — | 0.003 (0.01) | 0.003 (.01) | — | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.02 (0.03) |

| Reactivity (same-day effects) | ||||||

| Argument main effect | 0.21 (0.02)*** | 0.16 (0.02)*** | 0.20 (.02) *** | −0.20 (0.02)*** | −0.17 (0.03)*** | −0.14 (0.04)** |

| Family involvement | −0.03 (0.02) | — | −0.07 (.03)* | −0.01 (0.03) | — | −0.04 (0.05) |

| Argument*gender | — | 0.05 (0.02)* | 0.02 (.03) | — | −0.07 (0.04) | −0.12 (0.06)* |

| Family involvement*gender | — | — | 0.06 (0.04) | — | — | 0.08 (0.07) |

| Avoided arguments main effect | 0.09 (0.01)*** | 0.07 (0.01)*** | 0.07 (.02)* | −0.06 (0.02)** | −0.03 (0.03) | −0.01 (0.03) |

| family involvement | −0.01 (0.02) | — | 0.001 (0.03) | −0.001 (0.03) | — | −0.03 (0.04) |

| Avoided argument*gender | — | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.05 (0.02) | — | −0.06 (0.03)* | −0.09 (0.04)* |

| Family involvement*gender | — | — | −0.03(0.03) | — | — | 0.06 (0.06) |

| Residue (Previous-day effects) | ||||||

| Argument main effect | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.03 (0.02)* | 0.04 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.03) | −0.04 (0.03) | −0.02 (0.04) |

| Family involvement | 0.02 (0.02) | — | −0.01 (0.03) | −0.02 (0.03) | — | −0.02 (0.05) |

| Argument*gender | — | −0.03 (0.02) | −0.06 (0.03) | — | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.06 (0.05) |

| Family involvement*gender | — | — | 0.04 (0.04) | — | — | −0.01 (0.07) |

| Avoided arguments main effect | 0.01 (0.01) | −0.001 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.02) | −0.003 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.03) |

| family involvement | 0.003 (0.01) | — | 0.01 (0.02) | −0.02 (0.02) | — | −0.04 (0.04) |

| Avoided argument*gender | — | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.02) | — | 0.003 (0.03) | −0.01 (0.04) |

| Family involvement*gender | — | — | −0.01 (0.03) | — | — | 0.03 (0.05) |

Note. All models included covariates for marital status, age, race, education, day in study, and day of week. Family involvement was coded as 0 = did not involve family and 1 = involved family. The inclusion of family involvement makes associations conditional on family involvement (or no family involvement). Gender was coded as 0 = men, 1 = women.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Of the 2022 individuals in the full dataset, 1473 men (n = 604) and women (n = 869) reported at least one argument or avoided argument during the 8 days of the study. Individuals in the study reported 1355 arguments (9.10% of days); of these arguments, 886 (65.38%) involved family members. Similarly, 2177 individuals reported avoided arguments (14.63% of days), and 1256 of these avoided arguments (57.69%) included family members.

Family involvement as a moderator of stressor-affect associations

We predicted that when an interpersonal daily stressor involved family, participants would report higher negative and lower positive affective reactivity and residue compared to when interpersonal daily stressors did not involve family (H1). Note that the inclusion of family involvement makes associations conditional on family involvement.

Reactivity.

As seen in Models 1a and 1b in Table 2, family involvement did not moderate associations between arguments or avoided arguments and affective reactivity for negative or positive affect.

Residue.

Family involvement did not significantly moderate associations between arguments or avoided arguments and negative or positive affective residue (see Models 1a and 1b in Table 2).

Gender as a moderator for stressor-affect associations

We hypothesized that when interpersonal daily stressors occur, women would report higher negative and lower positive affective reactivity and residue compared to men (H2).

Reactivity.

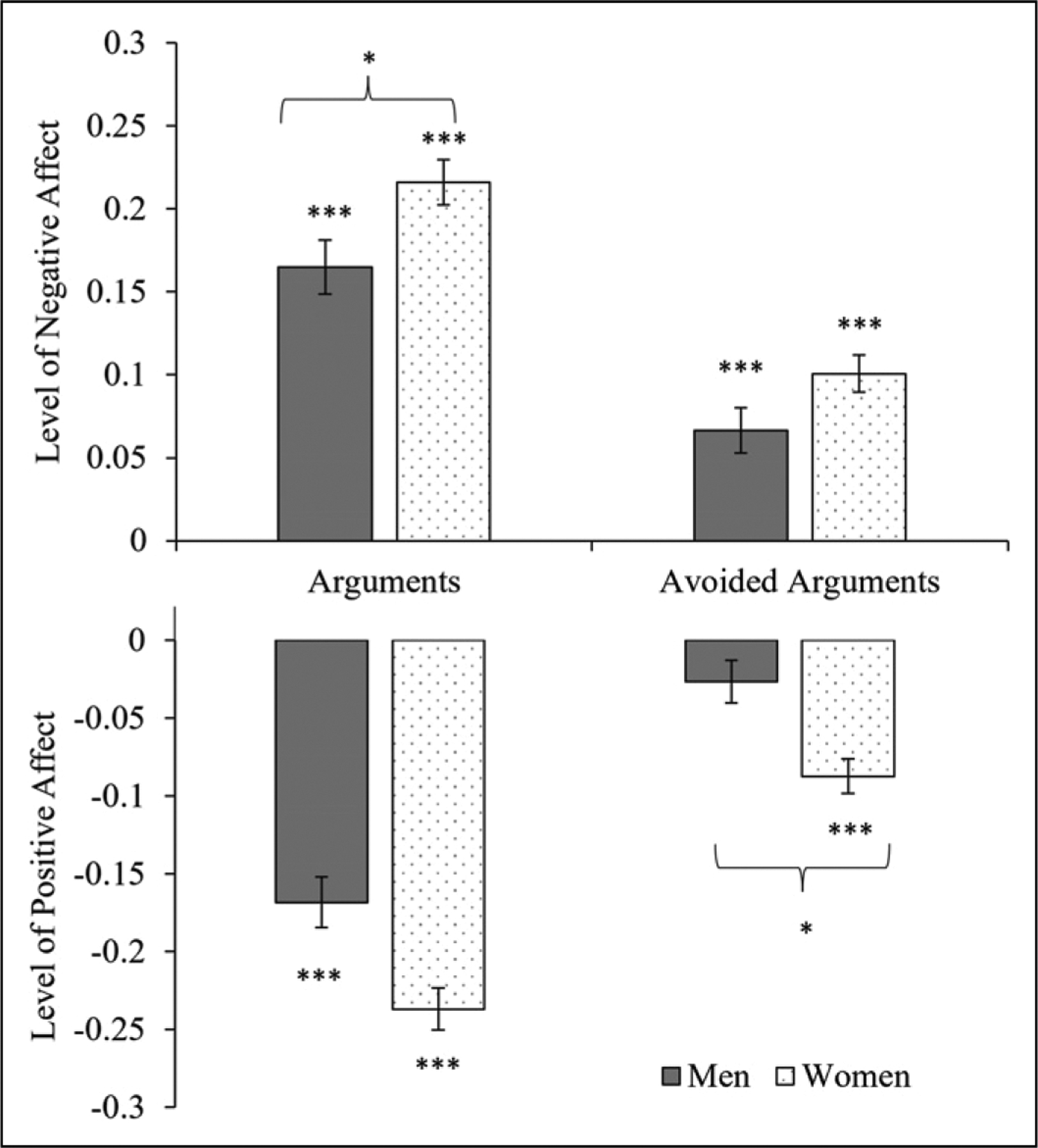

Models 2a and 2b in Table 2 show the interaction gender and both arguments and avoided arguments for both negative and positive affective reactivity, respectively. The interaction between gender and arguments or avoided arguments was significant for some but not all associations (see Figure 1). Post hoc analyses, women exhibited significantly greater increases in negative affect (estimate = 0.22, SE = 0.01, p < .0001) compared to men (estimate = 0.16, SE = 0.02, p < .0001) on days when an argument occurred.

Figure 1.

Associations between Daily Interpersonal Stressors and Stressor-Related Affect by Gender. Note. Top panel represents gender differences in negative affective reactivity. Bottom panel represents gender differences in positive affective reactivity. Error bars are standard errors. Asterisks represent significance of estimates: *p < .05 **p < .01 ***p < .001.

For positive affective reactivity, gender significantly interacted with avoided arguments, but not arguments. As shown in Figure 1, women reported significant decreases in positive affect reactivity (estimate = −0.09, SE = 0.02, p < .0001), whereas men did not show any significant decreases in positive affect (estimate = −.02, SE = 0.03, p = .25) when avoided arguments occurred. To understand whether this was the result of women experiencing more interpersonal stressors than men, we examined an additional model accounting for gender differences in average exposure to arguments and avoided arguments - associations remained.

Residue.

Gender did not significantly interact with previous-day arguments or avoided arguments to predict negative or positive affective residue.

Interactions between family involvement and gender predicting stressor-related affect

We hypothesized that women would be more impacted by interpersonal daily stressors when family is involved and less impacted by interpersonal daily stressors when family is not involved compared to men (H3).

Reactivity.

Models examining negative and positive affective reactivity are in Table 2, Models 3a and 3b. The interaction between gender and family involvement in arguments or avoided arguments was not significant for negative or positive affective reactivity.

Residue.

The interaction between gender and family involvement in arguments or avoided arguments was not significant for negative or positive affective residue.

Discussion

Guided by the daily stress process model (Almeida, 2005) and the linked lives tenet of life course theory (Elder, 1994), the aim of this study was to examine how family involvement and gender differentially impacted daily interpersonal stressor-affect associations. Daily interpersonal stressors are common and potent influences of health and well-being. Because family relationships are salient in midlife and gender shapes family relationships, daily stressors, and health and well-being, the current study adds to the literature by examining how both family involvement and gender are associated with daily interpersonal stressor-affect associations. Considering which daily interpersonal stressors are most potent, and for whom these stressors are most potent, may provide important information for personalized interventions.

Contrary to our hypothesis one, we found that reactivity and residue associated with arguments and avoided arguments did not differ depending on whether family was involved. We found partial support for hypothesis two in that women exhibited more stressor-related affect than men, but these gender differences manifested in specific ways based on the type of daily interpersonal stressor and affect valence. Compared to men, women exhibited larger affective reactions including increased negative affect associated with arguments and decreased positive affect associated with avoided arguments. Further, and contrary to hypothesis three, family involvement and gender did not interact to predict reactivity or residue associated with daily interpersonal stressors. Finally, across all hypotheses and models, associations were only significant for affective reactivity and not affective residue.

Family involvement in stressor-related affect

As family is a crucial context in both development (Settersten, 2018) and daily stress processes (Almeida, 2005), we hypothesized that participants would report lower positive and higher negative affective reactivity and residue when interpersonal stressors did not involve family; however, this hypothesis was not supported. Instead, we found that associations between both daily interpersonal stressors and stressor-related affect did not differ by family involvement. Because all daily stressors within this study are interpersonal in nature, individuals often will have an on-going relationship with other people involved in the daily stressor (e.g., spouse, work colleague). The quality and closeness of these relationships may create stronger ties across both family and non-family members. As such, individuals may be similarly invested in these relationships (Rustbult et al., 1991) and thus may be more reactive regardless of whether family was involved or not. Rustbult and colleagues (1991) suggest that when individuals are invested in their relationships, they may work to preserve the relationship. These arguments and avoided arguments may, however, be a threat to that relationship and result in more stressor-related affect, indicative of the quality and closeness of the relationship respondents shared with the people they interacted with. Thus, our results are consistent with research suggesting that individuals report significant affective reactivity with daily stressors involving friends and other people within their social networks (Almeida et al., 2011; Birditt et al., 2005). This result also suggests that while the type of the relationship (e.g., family, non-family) is important, the quality and closeness of the relationship may be key mechanisms for differentiating affective responses to daily interpersonal stressors.

Gender differences in stressor-related affect

The conceptual DSP model suggests gender is a resilience or vulnerability factor that influences daily stress processes (Almeida, 2005). Further, based upon theoretical perspectives on gender roles (Moen, 2011), we hypothesized that, compared to men, women would evince higher negative and lower positive affective reactivity and residue to interpersonal stressors. Women reported fewer arguments and avoided arguments, and when these daily interpersonal stressors occurred, women were less likely to report them involving family compared to without family. Interestingly, this is in opposition to previous research suggesting that women report more interpersonal problems compared to men (e.g., Antonucci et al., 1998). It may be that women did not appraise interactions as arguments and avoided arguments in a similar fashion as men, thus resulting in fewer reports of these interactions. Although the DISE prompts individuals to indicate if they had an argument or avoided argument, reporting depends on how individuals interpret and define these interactions. It could be that how women typically define an argument or avoided argument is different than how men do. As women tend to be more relationship-oriented (e.g., Moskowitz et al., 1994) and gender socialization supports women focusing on social integration (Dedovic et al., 2009), the association between gender and exposure to interpersonal daily stressors may be the result of attempting to minimize both arguments and avoided arguments with other people from occurring to keep cohesion within an individual’s social network.

Previous literature has suggested that women are socialized to understand and be more attuned to the emotional aspects of negative interactions, particularly in spousal relationships (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001). Specific to our study, we found gender differences in some, but not all, associations regarding daily interpersonal stress and stressor-related affect. In line with Kiecolt-Glaser and Newton’s (2001) findings, women showed higher levels of negative affective reactivity for arguments and avoided arguments compared to men. Moreover, women showed larger decreases in positive affect for avoided arguments compared to men. This is additionally in line with some previous research suggesting that women are more reactive to daily stressors, and interpersonal daily stressors specifically, when they occur (Almeida, 2005; Almeida & Kessler, 1998; Birditt & Fingerman, 2003, Birditt et al., 2005; Dedovic et al., 2009; Matud, 2004). We note that information and theoretical perspectives around gender differences and gender socialization most closely align with white, middle-class, straight, cisgender men and women (Ridgeway & Correll, 2004). Our results support ideas surrounding gender socialization and roles in that women reported more affective reactivity to these interpersonal daily stressors; however, this may be attributable to our sample that is mostly White, with a high educational background. Future work on daily stressor-related affect is needed among diverse samples, as these results may not generalize to other samples within or outside of the U.S.

No significant interactions between family involvement and gender

We hypothesized that women would be more impacted by interpersonal daily stressors when family is involved and less impacted by interpersonal daily stressors when family is not involved compared to men. The lack of significant interaction may be capturing the salience of working roles and relationship-related roles that have begun to blur for women and men, potentially because of the move toward more egalitarian gender roles (Perry-Jenkins & Gerstel, 2020).

Limitations and future directions

Our study has notable strengths. First, this study utilized data from an 8-day daily diary design. This multiple day design allowed us to examine both affective reactivity and affective residue as a means of comprehensively exploring associations between characteristics of interpersonal daily stressors and stressor-related affect. Additionally, this study is one of few to explore how daily stressor characteristics might interact with individual difference characteristics to moderate associations between daily stressors and stressor-related affect.

Although our study has strengths, it is important to acknowledge its weaknesses. First, when examining family involvement, we did not disambiguate between which family members was involved (e.g., spouse, child, parent, grandparent). Unfortunately, the frequency of stressors broken down by family member category resulted in quite small cell sizes; thus, we chose to dichotomize between family involvement or no family involvement. Affective responses to interactions, however, may depend on the specific family member relationship involved in the interpersonal interaction. Other scholars have documented differences in daily stress processes by which family members were involved. For example, Birditt and colleagues (2005) found that older adults reported more interpersonal daily stressors with spouses than with their children. Thus, future work should aim to further disambiguate how interactions with specific family members could impact affective reactivity to daily interpersonal stressors uniquely. Second, we note that the results of this study are limited to daily stressors that are interpersonal in nature. Future research would benefit from extending the investigation of family involvement into other types of stressors. Third, the current study is limited by using a binary gender variable. Specifically, individuals were only able to report on whether they identified as men or women which significantly limits generalizability to those who identify within the gender binary. Future work should explore the experiences of those who identify outside of the gender binary.

In addition, we were limited in the measure of affect; specifically, the MIDUS/NSDE dataset utilizes frequency of affect, rather than intensity. Therefore, future directions should explore how family involvement and gender may impact the intensity of affective associated with interpersonal daily stressors, affect-specific reactivity, and residue. Further, future research may even consider expanding this research by levels of arousal (e.g., Smyth et al., 2022). Indeed, given that affect socialization focuses on teaching young boys to hide more low-arousal emotions (e.g., sadness) and are more accepting of higher-arousal emotions (e.g., anger; Chaplin et al., 2005) different patterns may emerge when exploring these associations by valence. Finally, the NSDE II was conducted between 2004–2009, urging some caution regarding the generalizability of findings to daily life now. Notable social changes have occurred since, including broader social consideration and acceptance of gender fluidity, as well as radical changes to the type and nature of interpersonal interactions in daily life due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Future work would benefit from understanding how social changes may influence these daily phenomena.

Implications for practice

These findings have implications for programs and practice. One promising application is just-in-time interventions. Just-in-time interventions for daily stress have begun to garner attention in research (e.g., Sarker et al., 2017; Smyth & Heron, 2016), but can be intensive as they are ecological momentary interventions (EMI). EMIs, particularly those focusing on daily stress, utilize sensor-based assessments of stress to deliver an intervention protocol to an individual to help manage the daily stressor (Sarker et al., 2017). For example, an individual may have a device to note details of a stressor when it occurs. When a stressor occurs, the device (or a connected device) might be activated to deliver a specific intervention depending on whether a person identifies as a man or woman. Understanding both the stressor and individual characteristics associated with the most potent affective responses to daily interpersonal stressor can be leveraged to streamline interventions and decrease participant burden through targeting what types of daily stress may be most impactful to intervene on and for whom.

Conclusion

The current study underscores the importance of stressor and individual characteristics contributing to differential affective responsivity. Indeed, this study examined associations between family involvement, gender, and stressor-related affect in the context of daily interpersonal stressors. While there is variability in daily stressor characteristics, we found little evidence to suggest that when family is involved in arguments, there was a smaller affective toll than when arguments did not involve family. Thus, it may be important for individuals, regardless of gender or who their interpersonal stressor involved, to focus on resolving or mitigating their stressor-related affect. Some gender differences in affective responsivity to daily interpersonal stressors were observed but were not symmetric across arguments and avoided arguments. Our study highlights the importance of interpersonal interactions in daily lives. Research such as this can contribute to understanding how minimizing stressful interpersonal interactions can promote both short-term and long-term health and well-being. Moreover, the results of our study may reflect long-standing gender roles and social norms that are recognized in the U.S. today and expressed in social relational contexts (Ridgeway & Correll, 2004). We find that our results highlight salience of these roles and norms in daily interpersonal interactions. Under particular circumstances, women may benefit more from managing and reducing stressor-related affect and mitigating the impact stressor-related affect has on health and well-being.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Dr Richard A. Settersten, Jr. for valuable comments and feedback during the initial stages of this work.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Publicly available data from the MIDUS study was used for this research. Since 1995 the MIDUS study has been funded by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network, and National Institute on Aging (P01-AG020166; U19-AG051426). Preparation of this manuscript was partially supported through funding by the National Insititute of Health (T32 AG049697).

Footnotes

Open research statement

As part of IARR’s encouragement of open research practices, the authors have provided the following information: This research was not pre-registered. The data used in the research are available. Data and codebooks can be found at https://www.icpsr.umich.edu. Analytic code can be made available upon request of the first author by emailing: ddw5372@psu.edu

References

- Almeida DM (2005). Resilience and vulnerability to daily stressors assessed via diary methods. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(2), 64–68. 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00336.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, & Horn MC (2004). Is daily life more stressful during middle adulthood? In Brim OG, Ryff CD, & Kessler RC (Eds.), How healthy are we? A national study of midlife (pp. 425–451). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, & Kessler RC (1998). Everyday stressors and gender differences in daily distress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(3), 670–680. 10.1037/0022-3514.75.3.670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Stawski RS, & Cichy KE (2011). Combining checklist and interview approaches for assessing daily stressors: The Daily Inventory of Stressful Events. In Contrada RJ, & Baum A (Eds.), The handbook of stress science: Biology, psychology, and health. Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Wethington E, & Kessler RC (2002). The daily inventory of stressful events: An interview-based approach for measuring daily stressors. Assessment, 9(1), 41–55. 10.1177/1073191102009001006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, & Pearlin LI (1987). Structural contexts of sex differences in stress. In Barnett RC, Biener L, & Baruch GK (Eds.), Gender and stress (pp. 75–95). Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC (1985). Social support: Theoretical advances, recent findings and pressing issues. In Social support: Theory, research and applications (pp. 21–37). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC (2001). Social relations: An examination of social networks, social support, and sense of control. In Birren JE, & Schaie KW (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (pp. 427–453). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, & Akiyama H (1987). Social networks in adult life and a preliminary examination of the convoy model. Journal of Gerontology, 42(5), 519–527. 10.1093/geronj/42.5.519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Akiyama H, & Lansford JE (1998). Negative effects of close social relations. Family Relations, 47(4), 379–384. 10.2307/585268 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt KS, & Fingerman KL (2003). Age and gender differences in adults’ descriptions of emotional reactions to interpersonal problems. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58(4), P237–P245. 10.1093/geronb/58.4.p237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt KS, Fingerman KL, & Almeida DM (2005). Age differences in exposure and reactions to interpersonal tensions: A daily diary study. Psychology and Aging, 20(2), 33–340. 10.1037/0882-7974.20.2.330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstone AM (2003). Gender roles and society. In Miller JR, Lerner RM, & Schiamberg LB (Eds.), Human ecology: An encyclopedia of children, families, communities, and environments (pp. 335–338). ABC-CLIO. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, DeLongis A, Kessler RC, & Schilling EA (1989). Effects of daily stress on negative mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), 808–818. 10.1037/0022-3514.57.5.808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1995). Developmental ecology through space and time: A future perspective. In Moen P, ElderJr GH., & Lüscher K (Eds.), Examining lives in context: Perspectives on the ecology of human development (pp. 619–647). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/10176-018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cha Y, & Weeden KA (2014). Overwork and the slow convergence in the gender gap in wages. American Sociological Review, 79(3), 457–484. 10.1177/0003122414528936 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin TM, Cole PM, & Zahn-Waxler C (2005). Parental socialization of emotion expression: Gender differences and relations to child adjustment. Emotion, 5(1), 80–88. 10.1037/1528-3542.5.1.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Piazza JR, Luong G, & Almeida DM (2009). Now you see it, now you don’t: Age differences in affective reactivity to social tensions. Psychology & Aging, 24(3), 645–653. 10.1037/a0016673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Piazza JR, Mogle J, Sliwinski MJ, & Almeida DM (2013). The wear and tear of daily stressors on mental health. Psychological Science, 24(5), 733–741. 10.1177/095679612462222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang JJ, Turiano NA, Mroczek DK, & Miller GE (2018). Affective reactivity to daily stress and 20-year mortality risk in adults with chronic illness: Findings from the National Study of Daily Experiences. Health Psychology, 37(2), 170–178. 10.1037/hea0000567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichy KE, Fingerman KL, & Lefkowitz ES (2007). Age differences in types of interpersonal tensions. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 64(2), 171–193. 10.2190/8578-7980-301V-8771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichy KE, Stawski RS, & Almeida DM (2012). Racial differences in exposure and reactivity to daily family stressors. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(3), 572–586. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00971.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedovic K, Wadiwalla M, Engert V, & Pruessner JC (2009). The role of sex and gender socialization in stress reactivity. Developmental Psychology, 45(1), 45–55. 10.1037/a0014433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisend M (2019). Gender roles. Journal of Advertising, 48(1), 72–80. 10.1080/00913367.2019.1566103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH Jr. (1994). Time, human agency, and social change: Perspectives on the life course. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57(1), 4–15. 10.2307/2786971 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentecilla JL, Huo M, Birditt KS, Charles ST, & Fingerman KL (2020). Interpersonal tensions and pain among older adults: The mediating role of negative mood. Research on Aging, 42(3–4), 105–114. 10.1177/0164027519884765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunaydin G, Selcuk E, & Ong AD (2016). Trait reappraisal predicts affective reactions to daily positive and negative events. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(1000), 1–9. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, & Newton TL (2001). Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin, 127(4), 472–503. 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leger K, Charles S, & Almeida D (2020). Positive affect and negative emotional responses to daily stressors. Innovation in Aging, 4(Suppl 1), 638. 10.1093/geroni/igaa057.2189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leger KA, Charles ST, & Almeida DM (2018). Let it go: Lingering negative affect in response to daily stressors is associated with physical health years later. Psychological Science, 29(8), 1283–1290. 10.1177/0956797618763097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leger KA, Charles ST, & Almeida DM (2019). Positive emotions experienced on days of stress are associated with less same-day and next-day negative emotion. Affective Science, 1–8(1), 20–27. 10.1007/s42761-019-00001-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matud MP (2004). Gender differences in stress and coping styles. Personality and Individual Differences, 37(7), 1401–1415. 10.1016/j.paid.2004.01.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moen P (2011). From ‘work–family’ to the ‘gendered life course’ and ‘fit’: Five challenges to the field. Community, Work & Family, 14(1), 81–96. 10.1080/13668803.2010.532661 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz DS, Suh EJ, & Desaulniers J (1994). Situational influences on gender differences in agency and communion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(4), 753–761. 10.1037/0022-3514.66.4.753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, & Kolarz CM (1998). The effect of age on positive and negative affect: A developmental perspective on happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(5), 1333–1349. 10.1037//0022-3514/98/S3-00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry-Jenkins M, & Gerstel N (2020). Work and family in the second decade of the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 420–453. 10.1111/jomf.12636 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza JR, Charles ST, Sliwinski MJ, Mogle J, & Almeida DM (2013). Affective reactivity to daily stressors and long-term risk of reporting a chronic physical health condition. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 45(1), 110–120. 10.1007/s12160-012-9423-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway CL, & Correll SJ (2004). Unpacking the gender system: A theoretical perspective on gender beliefs and social relations. Gender & Society, 18(4), 510–531. 10.1177/0891243204265269 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rook KS (2001). Emotional health and positive versus negative social exchanges: A daily diary analysis. Applied Developmental Science, 5(2), 86–97. 10.1207/S1532480XADS0502_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, Verette J, Whitney GA, Slovik LF, & Lipkus I (1991). Accommodation processes in close relationships: Theory and preliminary empirical evidence. Journal of Personality and social Psychology, 60(1), 53–78. 10.1037/0022-3514.60.1.53 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sarker H, Hovsepian K, Chatterjee S, Nahum-Shani I, Murphy SA, Spring B, Ertin E, al’Absi M, Nakajima M, & Kumar S (2017). From markers to interventions: The case of just-in-time stress intervention. In Mobile health (pp. 411–433). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute (2013). SAS (Version 9.4). SAS Institute, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Settersten RA (2018). Nine ways that social relationships matter for the life course. In: Social networks and the life course (pp. 27–40). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling OK, & Diehl M (2014). Reactivity to stressor pile-up in adulthood: Effects on daily negative and positive affect. Psychology and Aging, 29(1), 72–83. 10.1037/a0035500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott Stacey B, Sliwinski Martin J, Zawadzki Matthew, Stawski Robert S, Kim Jinhyuk, Marcusson-Clavertz David, Lanza Stephanie T, Conroy David E, Buxton Orfeu, Almeida David M, & Smyth Joshua M (2020). A Coordinated Analysis of Variance in Affect in Daily Life. Assessment, 1552–348927(8), 1683–1698. 10.1177/1073191118799460. 30198310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settersten RA Jr. (2015). Relationships in time and the life course: The significance of linked lives. Research in Human Development, 12(3–4), 217–223. 10.1080/15427609.2015.1071944 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sin NL, Graham-Engeland JE, & Almeida DM (2015). Daily positive events and in-flammation: Findings from the national study of daily experiences. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 43(1), 130–138. 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.07.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sin NL, Sloan RP, McKinley PS, & Almeida DM (2016). Linking daily stress processes and laboratory-based heart rate variability in a national sample of midlife and older adults. Psychosomatic Medicine, 78(5), 573–582. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM, & Heron KE (2016). Is providing mobile interventions” just-in-time” helpful? An experimental proof of concept study of just-in-time intervention for stress management. In: 2016 IEEE Wireless health (WH) (pp. 1–7). IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM, Sliwinski MJ, Zawadzki MJ, Scott SB, Conroy DE, Lanza ST, Marcusson-Clavertz D, Kim J, Stawski RS, Stoney CM, Buxton OM, Sciamanna CN, Green PM, & Almeida DM (2018). Everyday stress response targets in the science of behavior change. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 101(1), 20–29. 10.1016/j.brat.2017.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM, Zawadzki MJ, Marcusson-Clavertz D, & Scott S (2022). Computing components of everyday stress: Exploring conceptual challenges and new opportunities. Perspectives on Psychological Science. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stawski RS, Cerino EC, Witzel DW, & MacDonald WS (2019). Daily stress processes as contributors to and targets for promoting cognitive health in later life. Psychosomatic Medicine, 81(1), 81–89. 10.1097/psy.000000000000643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas PA, Liu H, & Umberson D (2017). Family relationships and well-being. Innovation in Aging, 1(3), 1–11. 10.1093/geroni/igx025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Chen MD, House JS, Hopinks K, & Slaten E (1996). The Effect of Social Relationships on Psychological Well-Being: Are Men and Women Really So Different? American Sociological Review, 61(5), 837–857. 10.2307/2096456 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verma R, Balhara YPS, & Gupta CS (2011). Gender differences in stress response: Role of developmental and biological determinants. Industrial Psychiatry Journal, 20(1), 4–10. 10.4103/0972-6748.98407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D (1988). Intraindividual and interindividual analysis of positive and negative affect: Their relation to health complaints, perceived stress, and daily activities. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1020–1030. 10.1037/0022-3514.6.1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, & Tellegen A (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witzel DD, & Stawski RS (2021). Resolution status and age as moderators for interpersonal everyday stress and stressor-related affect. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. Advance online publication. 10.1093/geronb/gbab006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhaoyang R, Scott SB, Smyth JM, Kang JE, & Sliwinski MJ (2020). Emotional responses to stressors in everyday life predict long-term trajectories of depressive symptoms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 54(6), 402–412. 10.1093/abm/kaz057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhaoyang R, Sliwinski MJ, Martire LM, & Smyth JM (2018). Age differences in adults’ daily social interactions: An ecological momentary assessment study. Psychology and Aging, 33(4), 607–618. 10.1037/pag0000242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]