Abstract

Objectives:

We describe the prevalence and correlates of non-use of preferred contraceptive method among women 18–44 years of age in Ohio using contraception.

Study Design:

The population-representative Ohio Survey of Women had 2,529 participants in 2018–2019, with a response rate of 33.5%. We examined prevalence of preferred method non-use, reasons for non-use, and satisfaction with current method among current contraception users (n=1,390). We evaluated associations between demographic and healthcare factors and preferred method non-use.

Results:

About 25% of women reported not using their preferred contraceptive method. The most common barrier to obtaining preferred method was affordability (13%). Those not using their preferred method identified long-acting methods (49%), oral contraception (33%), or condoms (21%) as their preferred methods. The proportion using their preferred method was highest among intrauterine device (IUD) users (86%) and lowest among emergency contraception users (64%). About 16% of women using permanent contraception reported it was not their preferred method. Having the lowest socioeconomic status (versus highest) (prevalence ratio [PR]: 1.47, 95% CI: 1.11–1.96), Hispanic ethnicity (versus non-Hispanic white) (PR: 1.83, 95% CI: 1.15–2.90), reporting poor provider satisfaction related to contraceptive care (PR: 2.33, 95% CI: 1.02–5.29), and not having a yearly women’s checkup (PR: 1.31, 95% CI: 1.01–1.68) were significantly associated with non-use of preferred method. Compared to preferred method non-users, higher proportions of preferred method users reported consistent contraceptive use (89% vs. 73%, p<0.001) and intent to continue use (79% vs. 58%, p<0.001).

Conclusions:

Affordability and poor provider satisfaction related to contraceptive care were associated with non-use of preferred contraceptive method. Those using their preferred method reported more consistent use.

Keywords: contraception, patient preference, patient centered, reproductive health, Ohio, United States

1. Introduction

While contraception use is well-characterized in the U.S., the mismatch between contraceptive use and preference is not as well studied. Small studies found that 36% of adult women do not use their preferred method [1] and that 69% of women attending a community college preferred a more effective method [2]. A recent analysis of 2015–2017 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) data found that 22% of reproductive-age U.S. women at risk of unplanned pregnancy would have preferred a different contraceptive method if cost were not a factor [3].

Although understanding contraceptive method preference is essential for understanding unmet contraceptive need (generally characterized as the proportion of fertile individuals who want to prevent pregnancy, but are not using contraception), true method preference is difficult to capture, especially at the population level. Population-based surveys, such as the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, lack questions about contraceptive method preference. The NSFG recently added a question about preference, but the question only focuses on cost as a barrier and does not collect information on methods preferred [3].

People may face barriers in obtaining their preferred method. Cost or lack of insurance coverage prevents women from using their preferred methods [1,2]. Postpartum women in Texas had considerable unmet demand for long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) and sterilization [4,5]. Low use of these methods among publicly-insured postpartum women was attributed to financial and system-level barriers [5]. Misconceptions about contraception, especially LARC [6–8], may also be barriers to preferred method use, which may be mitigated by high-quality contraceptive counseling [9,10].

The Ohio Survey of Women (OSW), a population-based survey about reproductive health conducted among adult, reproductive-age women in Ohio, collects detailed information about contraceptive preference and use. Ohio is the seventh most populous state in the US, with an economically diverse population. Abortion access is limited in Ohio [11], and infant mortality is high [12]. State legislation generally has supported access to contraception for people with low income, but barriers recently have been introduced. Since 2006, women with a household income below 185% of the federal poverty level (FPL) were eligible for an Ohio Medicaid ‘family planning waiver’ to receive free contraceptive care [13]. In June 2017, the Ohio Department of Medicaid made a change to permit reimbursement to hospitals for postpartum LARC placement [14,15]. Nonetheless, more recent legislative changes enacted by state and federal legislatures, such as Ohio HB 294 and the Trump administration’s changes to Title X regulations in March 2019, have also increased barriers for Ohioans seeking contraception. Notably, some of these were contemporaneous with the OSW’s data collection.

Our objective was to measure the gap between preferred and actual contraceptive method use. We also examined stated reasons for non-use of preferred method, knowledge of where to obtain methods at low or no cost, and correlates of preferred method non-use. Furthermore, we compared satisfaction with current method, frequency of use of current method, confidence in correct use of current method, intent to discontinue current method, and control over method between preferred method users and non-users.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and population

We analyzed the first wave of OSW data, a population-based survey of adult, reproductive-aged women in Ohio (n=2,529) collected in October 2018 to June 2019. NORC at the University of Chicago conducted the survey, using similar methods and questions as those employed for the South Carolina Initiative (SCI) and Delaware Contraceptive Access Now (Del-CAN). NORC’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the study and the Ohio State University IRB deemed the present analysis exempt from further review.

Survey sampling methods were similar to related surveys conducted in other states [16]. In brief, NORC randomly sampled households from an address-based sampling frame, oversampling households in the 31 rural Appalachia counties in the state. NORC invited households via a postal letter to complete the questionnaire online. Women 18–44 years of age from the sampled households, including multiple women from a single household, were eligible to participate. Non-respondent households were mailed a paper survey to complete. A total of six survey request attempts were made to contact non-responders. The response rate was 33.5%. Survey weights account for base sampling, adjustment for unknown eligibility, non-response, adjustment for household size, and post-stratification.

Because information about contraception preference was unavailable for contraception non-users, we restricted the analysis to respondents who were current users of at least one of the following methods: withdrawal, oral contraception, patch, ring, injectable contraception, IUD, implant, male condom, other barrier methods, natural family planning, emergency contraception, or partner’s vasectomy. We excluded respondents with missing data about contraceptive preference.

We note that the survey is titled Ohio Survey of Women, and the screener question asked females aged 18–44 years to complete the survey. Thus, anyone who identified as a woman or female in the screener question could participate in the survey. Subsequent survey questions asked participants to describe their gender. We restricted the analytic sample to contraception users of the methods listed above; we did not restrict the sample based on participant descriptions of their gender. Few transgender, gender-nonbinary, and gender-nonconforming individuals completed the survey, possibly a result of the order of the screener question and gender questions.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Use of preferred contraceptive method

The primary outcome was whether the respondent was a user or non-user of her preferred contraceptive method. Current contraceptive method was measured using the question, “What kind(s) of birth control method(s) are you currently using?” We measured preferred contraceptive method using the question, “If you could use any birth control method you wanted, what method(s) would you use?” Respondents could select “I am using the method that I want” or they could choose a specific method or methods from a list. Respondents were also able to check “Other” and provide a write-in response. We classified users of preferred method based solely on whether they selected the response option “I am using the method that I want.” The survey began with descriptions of contraceptive methods, including pictures, which respondents could refer to as a resource while completing the survey.

2.2.2. Reasons for Non-Use of Preferred Method

Reasons for not using a preferred contraceptive method were captured using the question, “What is the main reason you are not using the birth control method you want to use?” Participants were prompted to select all applicable responses from a list of options (e.g., “I can’t afford it,” “My insurance doesn’t cover it,” and “I don’t know where I can get it”). The survey also included the question, “Do you know where you can go to get any of the following birth control methods for free or low cost?” Respondents selected “yes” or “no” for the following methods: condom, IUD, implant, injectable contraception, oral contraception, and vaginal ring.

2.2.3. Correlates of using preferred method

We evaluated the following as potential correlates of non-use of preferred contraceptive method: age, race/ethnicity, marital status, rural Appalachian residence, and socioeconomic status (SES) (a combined income and education indicator). For SES, age, and race, we used variables with imputed missing values using single hot-deck imputation method carried out by NORC. We also evaluated measures of healthcare access and quality: health insurance status, having a yearly women’s check-up in the past 12 months, receiving counseling or information about birth control from a medical provider in the past 12 months, and satisfaction with care received related to birth control, measured with a 4-item version of the Interpersonal Quality of Family Planning (IQFP) Scale [17]. We used the mean of the four items, which had excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.95), and we rounded the values to the nearest whole number to simplify interpretability of the composite by ensuring the composite uses the same metric as the original items.

2.2.4. Use of and satisfaction with current method

We evaluated use and satisfaction of current method with the following questions: (1) “Thinking about the past three months, how often did you use a method of birth control when you had penile/vaginal sex?” (2) “How satisfied are you with your birth control method?” (3) “How confident are you that you have been using your method of birth control correctly for the past 3 months?” (4) “Stopping your current birth control method in the next 3 months is:” with answer choices ranging from “very likely” to “very unlikely,” and (5) “Your use of your birth control method in the past 3 months was:” with answer choices ranging from “completely under my control” to “not at all under my control.”

2.3. Statistical analysis

We calculated the prevalence of reporting non-use of preferred method and the reasons for preferred contraceptive non-use. Next, we used bivariate log binomial regression to examine the potential correlates of preferred method non-use. We reported unadjusted associations only, because the goal of the analysis was descriptive: to identify the demographic and healthcare-related factors associated with preferred method non-use. Finally, we reported the prevalence of consistency of use, intention to continue use and satisfaction of current method, each stratified by users and non-users of their preferred method. We used STATA 16 (College Station, TX) and the statistical weights provided by NORC for all analyses.

3. Results

Among the 2,529 participants in the first wave of the OSW, 1,746 reported currently using at least one contraceptive method. Of these women, we excluded those with missing data about method preference (n=356), leading to an analytic sample of 1,390 respondents.

3.1. Participant characteristics

Overall, 1,046 respondents (75%) reported using their preferred method, and 344 respondents (25%) reported not using their preferred method (Table 1). Nearly half of preferred method non-users (46%) were in the lowest SES category (some college or less and household income less than $75,000). In contrast, just over one-third (36%) of those using their preferred method were in this SES category. Most women (82%) were partnered or married. Similar proportions of preferred method users and non-users reported not having health insurance throughout the past year (11% and 12%, respectively). Overall, most rated their provider as “very good” or “excellent.”

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Sample, Ohio Survey of Women, October 2018-June 2019, N=1,390

| Total (N=1,390) |

Using Preferred Method (N=1,046) |

Not Using Preferred Method (N=344) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Weighted % | N | Weighted % | N | Weighted % | |

|

| ||||||

| Age category (years) | ||||||

| 18–24 | 236 | 25.9 | 176 | 26.1 | 60 | 25.6 |

| 25–29 | 268 | 23.3 | 209 | 24.5 | 59 | 19.8 |

| 30–34 | 265 | 22.5 | 193 | 21.5 | 72 | 25.4 |

| 35–39 | 323 | 13.6 | 239 | 13.2 | 84 | 14.7 |

| 40–44 | 298 | 14.7 | 229 | 14.8 | 69 | 14.6 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Education and Income (SES) | ||||||

| Highest: Bachelor’s degree+, $75k+ | 462 | 23.8 | 365 | 25.4 | 97 | 19.1 |

| Medium-high: Bachelor’s degree+, <$75k | 339 | 27.4 | 261 | 27.9 | 78 | 26.1 |

| Medium-low: Some college or less, $75k+ | 165 | 10.1 | 121 | 10.4 | 44 | 9.0 |

| Lowest: some college or less, <$75k | 424 | 38.6 | 299 | 36.2 | 125 | 45.7 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 1,193 | 76.9 | 903 | 78.5 | 290 | 71.9 |

| Black | 67 | 12.8 | 46 | 11.5 | 21 | 16.6 |

| Hispanic | 39 | 2.3 | 27 | 1.8 | 12 | 3.9 |

| Multi/Other | 91 | 8.1 | 70 | 8.2 | 21 | 7.6 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Partnered/Currently Married | ||||||

| Yes | 1,190 | 82.0 | 899 | 82.4 | 291 | 80.9 |

| No | 192 | 18.0 | 145 | 17.7 | 47 | 19.1 |

| Missing | 8 | 2 | 6 | |||

| Resides in Rural Appalachia | ||||||

| Yes | 271 | 13.5 | 202 | 13.4 | 69 | 13.8 |

| No | 1,119 | 86.5 | 844 | 86.6 | 275 | 86.2 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Had Health Insurance for All of the Past Year | ||||||

| Yes | 1,268 | 88.7 | 961 | 88.9 | 307 | 88.2 |

| No | 115 | 11.3 | 79 | 11.1 | 36 | 11.8 |

| Missing | 7 | 6 | 1 | |||

| Birth Control Care Satisfaction | ||||||

| Excellent | 662 | 64.0 | 527 | 68.1 | 135 | 51.9 |

| Very Good | 204 | 20.1 | 150 | 19.3 | 54 | 22.2 |

| Good | 104 | 13.9 | 61 | 10.8 | 43 | 23.1 |

| Fair | 19 | 1.7 | 12 | 1.5 | 7 | 2.1 |

| Poor | 7 | 0.4 | 4 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.8 |

| Missing | 394 | 292 | 102 | |||

| Had a Yearly Women’s Check-Up in the Past 12 Months | ||||||

| Yes | 1,034 | 73.3 | 798 | 75.2 | 236 | 67.8 |

| No | 342 | 26.7 | 241 | 24.9 | 101 | 32.2 |

| Missing | 14 | 7 | 7 | |||

| Had Counseling or Information about Birth Control from Medical Provider in the Past 12 Months | ||||||

| Yes | 439 | 33.3 | 333 | 33.7 | 106 | 32.3 |

| No | 925 | 66.7 | 695 | 66.3 | 230 | 67.7 |

| Missing | 26 | 18 | 8 | |||

Participants who were excluded from the study because of missing data on method preference were somewhat older, had lower SES, and were from rural Appalachia compared to those with data (Supplemental Table 1). Participants who were excluded for contraception non-use had a lower SES compared to participants in the analytic sample (Supplemental Table 1).

3.2. Preferred methods and methods used among non-users of preferred method

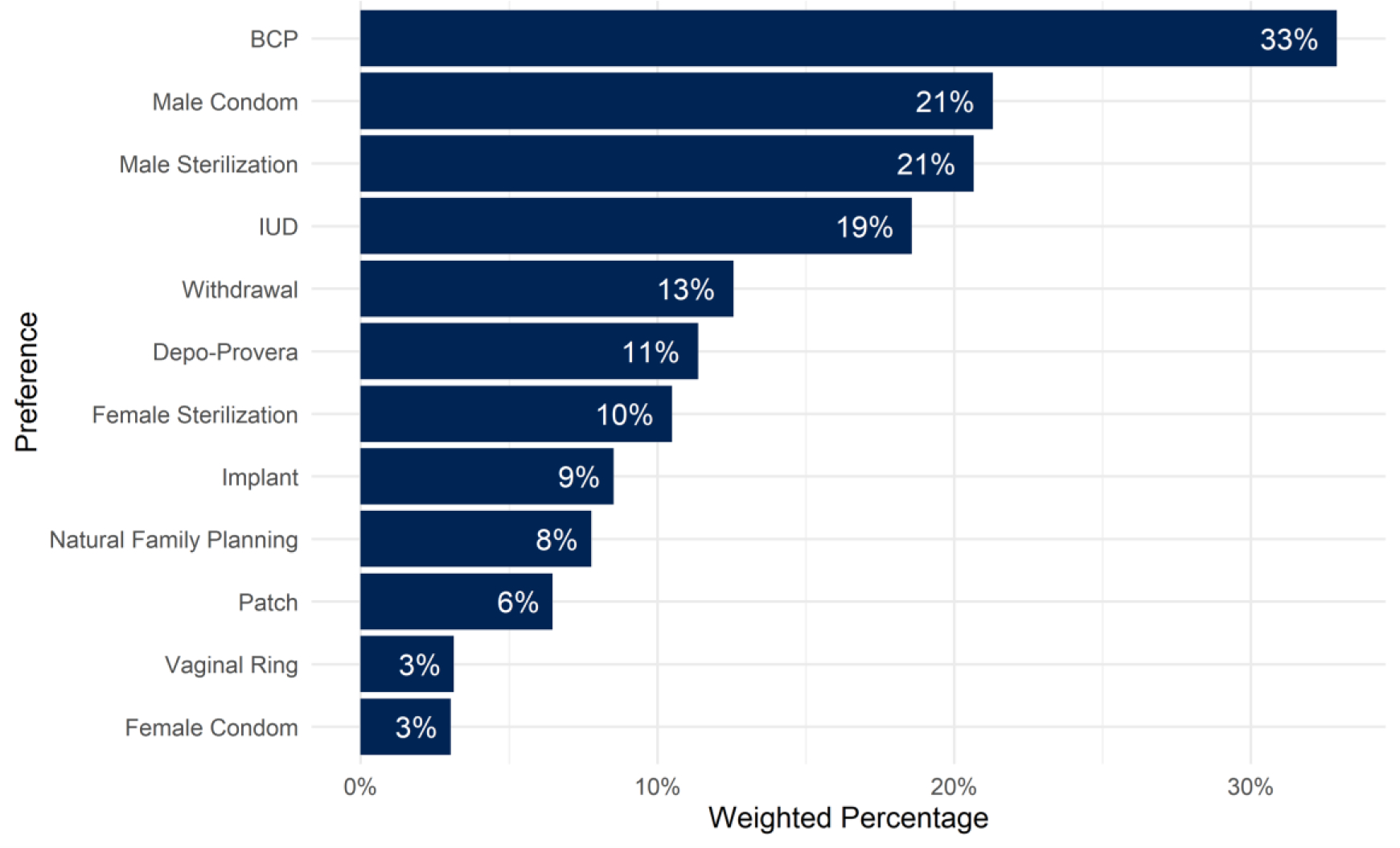

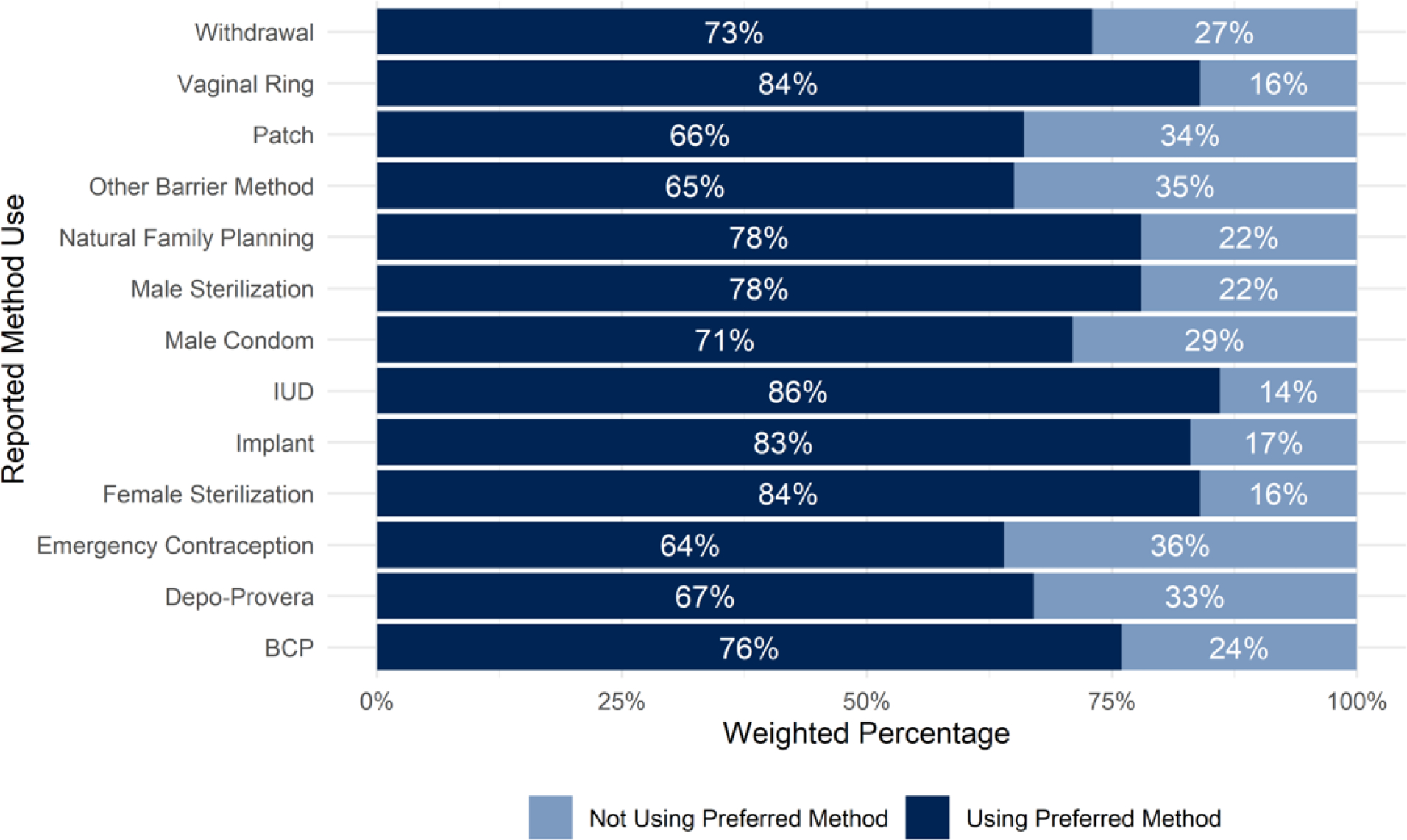

Among preferred method non-users, respondents commonly identified LARC methods (25%), sterilization (28%), oral contraception (33%), or condoms (21%) as their preferred methods (Figure 1). IUD users had the highest proportion who were using their preferred method (86%) (Figure 2). Most women using female sterilization (84%), vaginal ring (84%) or implant (83%) also were using their preferred method. However, we note that 16% of women using female sterilization reported it was not their preferred method, and instead preferred oral contraception (8%), the patch (2%), the vaginal ring (2%), or the male condom (2%). Preferred method use was lower among women using the contraceptive patch (66%), emergency contraception (64%), DMPA (67%), male condoms (71%), or other barrier methods (65%).

Figure 1.

Methods preferred among non-users of preferred method, Ohio Survey of Women, October 2018-June 2019, N=344

Figure 2.

Proportion of respondents reporting they were using their preferred contraceptive by method used, Ohio Survey of Women, October 2018-June 2019, N=1,390

3.3. Reported reasons for not using preferred contraceptive method

Among women reporting that they were not using their preferred contraceptive method, the most common reasons provided were “I can’t afford it” (12%) and “I’m not sure” (18%) (Table 2). Few respondents reported not using their preferred methods because the doctor or clinic did not offer it (1%), because they lacked insurance coverage (1%), or because they did not know where to obtain it (3%). A higher proportion of preferred method users reported not experiencing delays or trouble obtaining their method compared to preferred method non-users (88.6% vs. 80.4, p-value=0.01) (Supplemental Table 2). The most common reasons for delays or troubles in obtaining birth control were related to cost and insurance; although a higher proportion of preferred method non-users reported these barriers compared to preferred method users, this difference was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Reasons reported for not using preferred method, N=344

| Reported Reason* | N | Weighted % |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| I can’t afford it | 27 | 12.5 |

| My partner doesn’t want me to use it | 17 | 7.1 |

| I’m not currently sexually active | 19 | 6.8 |

| I have an appointment scheduled | 16 | 6.6 |

| My doctor advised against it | 14 | 6.4 |

| It’s too much hassle to get it (no transportation or childcare, hard to take time off work) | 13 | 5.1 |

| I’m trying to get pregnant | 5 | 3.1 |

| I don’t know where I can get it | 7 | 2.9 |

| My insurance doesn’t cover it | 5 | 1.3 |

| My doctor/clinic doesn’t offer it | 3 | 1.1 |

| I’m not sure | 53 | 18.4 |

| Other | 87 | 39.0 |

| Missing | 78 | |

Respondents were asked to choose one main reason

3.4. Knowledge of where to obtain methods for free or low cost

In general, relative to those using their preferred method, fewer preferred method non-users knew where to get condoms, IUD, implant, injectable contraception, oral contraception, and the vaginal ring at low or no cost. However, this difference was statistically significant only for the IUD and implant (Table 3).

Table 3.

Frequency and weighted percentages of respondents who knew where to get select contraceptive methods for free*, Ohio Survey of Women, October 2018-June 2019, N=1,390

| Method | Total (N=1,390) |

Using Preferred Method (N=1,046) |

Not Using Preferred Method (N=344) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Weighted (%) | N | Weighted (%) | N | Weighted (%) | p-value† | |

|

| |||||||

| Condom | 758 | 59.1 | 589 | 60.8 | 169 | 54.0 | 0.082 |

| IUD | 407 | 33.1 | 324 | 35.3 | 83 | 26.5 | 0.022 |

| Implant | 329 | 27.4 | 265 | 29.2 | 64 | 21.9 | 0.048 |

| DMPA | 414 | 33.3 | 320 | 34.1 | 94 | 31.0 | 0.426 |

| Oral contraception | 847 | 63.8 | 656 | 65.2 | 191 | 59.5 | 0.137 |

| Vaginal ring | 373 | 30.0 | 292 | 31.0 | 81 | 27.0 | 0.303 |

DMPA = medroxyprogesterone acetate, IUD = intrauterine device

values in cells are weighted percentages of those who said they know where to get the corresponding methods for free

from Pearson χ2 test corrected for the survey design, comparing the proportion of respondents who knew where to get each method for free between preferred method users and non-users

3.5. Correlates of not using preferred contraceptive method

Only SES and race were significantly associated with preferred method non-use (Table 4). The lowest SES category was associated with preferred method non-use compared to the highest SES category (prevalence ratio [PR]: 1.47, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.11–1.96). Hispanic ethnicity was associated with non-use of preferred contraceptive method compared to identifying as non-Hispanic white (PR: 1.83, 95% CI: 1.15–2.90).

Table 4.

Unadjusted associations between select demographic and healthcare access factors and not using preferred contraceptive method, Ohio Survey of Women, October 2018-June 2019, N=1,390

| PR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–24 | 1 | Ref |

| 25–29 | 0.86 | (0.60, 1.24) |

| 30–34 | 1.14 | (0.80, 1.65) |

| 35–39 | 1.10 | (0.78, 1.55) |

| 40–44 | 1.00 | (0.70, 1.44) |

| Education and Household Income (SES) | ||

| Bachelor’s degree+, $75k+ | 1 | Ref |

| Bachelor’s degree+, <$75k | 1.19 | (0.87, 1.63) |

| Some college or less, $75k+ | 1.11 | (0.76, 1.62) |

| Some college or less, <$75k | 1.47 | (1.11, 1.96) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 1 | Ref |

| Black | 1.39 | (0.90, 2.13) |

| Hispanic | 1.83 | (1.15, 2.90) |

| Multi/other | 1.00 | (0.64, 1.59) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Not partnered | 1 | Ref |

| Partnered | 0.93 | (0.68, 1.28) |

| Resides in Rural Appalachia | ||

| No | 1 | Ref |

| Yes | 1.02 | (0.78, 1.34) |

| Had Health Insurance for All of the Past Year | ||

| Yes | 1 | Ref |

| No | 1.05 | (0.72, 1.54) |

| Had Counseling or Information about Birth Control from Medical Provider in the Past 12 Months | ||

| Yes | 1 | Ref |

| No | 1.05 | (0.81, 1.36) |

| Had a Yearly Women’s Check-Up in the Past 12 Months | ||

| Yes | 1 | Ref |

| No | 1.31 | (1.01, 1.68) |

| Birth Control Care Provider Satisfaction Factor Score | ||

| Excellent | 1 | Ref |

| Very Good | 1.36 | (0.97, 1.92) |

| Good | 2.05 | (1.45, 2.91) |

| Fair | 1.54 | (0.70, 3.37) |

| Poor | 2.33 | (1.02, 5.29) |

PR = prevalence ratio, CI = confidence interval

Note: Bold font indicates confidence intervals that do not contain the null value of 1

Of the healthcare quality and access variables, scoring low on the IQFP scale (PR: 2.33, 95% CI: 1.02–5.29) and not having a yearly women’s check-up (PR: 1.31, 95% CI: 1.01–1.68) were associated with preferred method non-use.

3.6. Use and satisfaction of current method among users and non-users of preferred method

Preferred method users reported higher satisfaction (79% vs. 48%, p<0.001), frequency of use (89% vs. 73%, p<0.001), confidence in correct use (85% vs. 68%, p<0.001), intent to continue use (79% vs. 58%, p<0.001), and control (89% vs. 76%, p<0.001) compared preferred method non-users (Table 5).

Table 5.

Satisfaction and use of current contraceptive method, Ohio Survey of Women, October 2018-June 2019, N=1,390

| Method | Using Preferred Method (N=1,046) |

Not Using Preferred Method (N=344) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Weighted (%) | N | Weighted (%) | p-value† | |

|

| |||||

| Used method every time respondent had sex in the past 3 months | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 813 | 89.0 | 216 | 73.0 | |

| No | 82 | 11.1 | 69 | 27.0 | |

| Missing | 151 | 59 | |||

| Very satisfied with current birth control method | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 825 | 79.3 | 160 | 48.2 | |

| No | 197 | 20.8 | 164 | 51.8 | |

| Missing | 24 | 20 | |||

| Completely confident that respondent used method correctly in the last 3 months | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 884 | 85.3 | 233 | 68.3 | |

| No | 140 | 14.7 | 93 | 31.7 | |

| Missing | 22 | 18 | |||

| Very unlikely to stop current birth control method in the next 3 months | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 825 | 79.3 | 208 | 58.3 | |

| No | 193 | 20.8 | 113 | 41.7 | |

| Missing | 28 | 23 | |||

| Use of current birth control method was completely under the respondent’s control | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 892 | 88.9 | 243 | 75.6 | |

| No | 124 | 11.2 | 79 | 24.4 | |

| Missing | 30 | 22 | |||

values in cells are weighted percentages of those who said they know where to get the corresponding methods for free

from Pearson χ2 test corrected for the survey design, comparing preferred method users and non-users

4. Discussion

Overall, 25% of women reported not using their preferred contraceptive method. Among permanent contraception users, 16% reported not using their preferred method. Identifying as Hispanic or lower SES, reporting less satisfying contraception care experiences, and having no checkup in the past year were associated with preferred method non-use. Findings are similar to estimates from 2015–2017 NSFG data, which revealed that 22% were not using their preferred method due to cost, and that preferred method non-use was more common among Black or Hispanic women and those with lower incomes [3]. The present analysis excluded 28% of women who were not using contraception. This is lower than the prevalence of nonuse (35%) from 2015–2017 NSFG data [18]. We found that preferred use was higher among LARC and ring users but lower among users of emergency contraception, patch, injectable contraception, or barrier methods. Consistent with previous evidence [9,19,20], cost was a common barrier to obtaining contraception.

Many factors can shape method preferences: method knowledge (and misconceptions), experience, perceived health risks, side effects, effectiveness, non-contraceptive benefits, ease of use, availability, partner’s preferences, and cost [21,22]. Contraceptive counseling is key for increasing preference for more effective methods [9,10]. Providers often do not engage in individually-tailored conversations on preferences but instead privilege LARC due to its higher typical-use effectiveness [23,24]. This approach risks being coercive and misses other factors important in contraceptive decision-making [22,24–27]. We found an association between preferred method and an excellent provider rating for birth control but not with receiving birth control counseling.

People should have reproductive autonomy [28] to use preferred methods. Users of preferred methods might also be more adherent users. Our findings suggest that women who use their preferred methods perceive more satisfaction and control of their methods, and report more consistent use and confidence in correct use. Although a higher proportion of preferred method users reported being very satisfied with their method compared to non-users, almost half of the non-users reported satisfaction with their method; preferences for different methods may be weak. Furthermore, consistent and confident use may not apply to methods that are not user dependent.

A primary study strength is that findings are generalizable to adult, reproductive-aged women in Ohio who are current contraception users. Second, we used rich data that included questions about method preference and factors regarding access to preferred methods. However, a limitation is that because contraception non-users were not asked about method preference, we could not evaluate preferences among those who likely face the strongest barriers to contraception access. Furthermore, questionnaire design could affect responses to questions about preferred use [4], and some participants might have lacked knowledge of the full range of contraceptive options. While the survey included pictures and method descriptions, whether respondents read or understood them is unknown. Additionally, some analyses involved small subgroups; future surveys may consider over-sampling these subgroups. Finally, our response rate was low; although the weights adjusted for some differential non-response biases, non-respondents might have varied in their contraceptive preferences.

Overall, we found that perceived cost is an important, but not the sole, barrier to use of preferred methods. Reporting cost barriers was higher among preferred method non-users (but this difference was not statistically significant), suggesting that both preferred method users and non-users experience cost barriers, but users may be more likely to overcome them. An excellent provider rating may also facilitate use of preferred methods. These population-based findings extend our understanding of whether women are using methods that meet their preferences, which is an important step for defining gaps in care and designing interventions that truly elicit contraception preferences in a non-coercive way.

Supplementary Material

Implications:

Cost is an important barrier for women in obtaining their preferred contraceptive methods. Low quality birth control care may also be a barrier to preferred method use. Removal of cost barriers and improvement in contraceptive counseling strategies may increase access to preferred contraceptive methods.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to acknowledge NORC at the University of Chicago for implementing this survey.

Funding:

This study was funded by a philanthropic foundation that makes grants anonymously.

Role of the funding source:

The funder had no role in this analysis, including the analytic plan, the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: None

References

- [1].He K, Dalton VK, Zochowski MK, Hall KS. Women’s contraceptive preference-use mismatch. J Womens Health 2017;26:692–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hopkins K, Hubert C, Coleman-Minahan K, Stevenson AJ, White K, Grossman D, et al. Unmet demand for short-acting hormonal and long-acting reversible contraception among community college students in Texas. J Am Coll Health 2018;66:360–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Burke KL, Potter JE, White K. Unsatisfied contraceptive preferences due to cost among women in the United States. Contracept X 2020;2:100032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Potter JE, Hopkins K, Aiken ARA, Hubert C, Stevenson AJ, White K, et al. Unmet demand for highly effective postpartum contraception in Texas. Contraception 2014;90:488–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Potter JE, Coleman-Minahan K, White K, Powers DA, Dillaway C, Stevenson AJ, et al. Contraception after delivery among publicly insured women in Texas: Use compared with preference. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:393–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Russo JA, Miller E, Gold MA. Myths and misconceptions about long-acting reversible contraception (LARC). Journal of Adolescent Health 2013;52:S14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hathaway M, Torres L, Vollett-Krech J, Wohltjen H. Increasing LARC utilization: any woman, any place, any time. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 2014;57:718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].McNicholas C, Peipert JF. Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) for adolescent. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2012;24:293–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Peipert JF, Madden T, Allsworth JE, Secura GM. Preventing unintended pregnancies by providing no-cost contraception. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:1291–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Coleman-Minahan K, Potter JE. Quality of postpartum contraceptive counseling and changes in contraceptive method preferences. Contraception 2019;100:492–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Norris AH, Chakraborty P, Lang K, Hood RB, Hayford SR, Keder L, et al. Abortion access in Ohio’s changing legislative context, 2010–2018. Am J Public Health 2020;110:1228–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ohio Infant Mortality Data Brief. Ohio Department of Health; 2019. https://odh.ohio.gov/wps/portal/gov/odh/know-our-programs/infant-and-fetal-mortality/reports/data-brief [accessed December 13, 2020].

- [13].Ohio Department of Health Report: Reproductive Health & Wellness Program. Title X Clinical Services & Protocols 2020. Ohio Department of Health. https://odh.ohio.gov/wps/wcm/connect/gov/5f3d1d55-4e0f-4470-9c59-d9bb65eaaacb/2020+RHWP+Clinical+Protocols.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CONVERT_TO=url&CACHEID=ROOTWORKSPACE.Z18_M1HGGIK0N0JO00QO9DDDDM3000-5f3d1d55-4e0f-4470-9c59-d9bb65eaaacb-n8JYsO3 [accessed December 13, 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hospital Handbook Transmittal Letter (HHTL) 3352–17-08 2017. https://medicaid.ohio.gov/Portals/0/Resources/Publications/Guidance/MedicaidPolicy/Hosp/HHTL-3352-17-08.pdf?ver=2017-06-27-120019-060 [accessed December 13, 2020].

- [15].Lessons Learned About Payment Strategies to Improve Postpartum Care in Medicaid and CHIP. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2019. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/quality-of-care/downloads/postpartum-payment-strategies.pdf [accessed December 13, 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Evaluation of the Delaware Contraceptive Access Now Initiative. https://popcenter.umd.edu/delcaneval/ [accessed 5 May 2020].

- [17].Dehlendorf C, Fox E, Ahrens K, Gavin L, Hoffman A, Hessler D. Creating a brief measure for patient experience of contraceptive care: reduction of the interpersonal quality of family planning scale in preparation for testing as a performance measure. Contraception 2017;96:290. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Daniels K, Abma JC. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15–49: United States, 2015–2017. NCHS Data Brief 2018;327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gawron LM, Simmons RG, Sanders JN, Myers K, Gundlapalli AV, Turok DK. The effect of a no-cost contraceptive initiative on method selection by women with housing insecurity. Contraception 2020;101:205–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].White K, Portz KJ, Whitfield S, Nathan S. Women’s postabortion contraceptive preferences and access to family planning services in Mississippi. Womens Health Issues 2020;30:176–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Grady WR, Klepinger DH, Nelson-Wally A. Contraceptive characteristics: the perceptions and priorities of men and women. Fam Plann Perspect 1999;31:168–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lessard LN, Karasek D, Ma S, Darney P, Deardorff J, Lahiff M, et al. Contraceptive features preferred by women at high risk of unintended pregnancy. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2012;44:194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Dehlendorf C, Krajewski C, Borrero S. Contraceptive counseling: best practices to ensure quality communication and enable effective contraceptive use. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2014;57:659–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Brandi K, Fuentes L. The history of tiered-effectiveness contraceptive counseling and its effects on patient-centered family planning care. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Samari G, Foster DG, Ralph LJ, Rocca CH. Pregnancy preferences and contraceptive use among US women. Contraception 2020;101:79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Marshall C, Kandahari N, Raine-Bennett T. Exploring young women’s decisional needs for contraceptive method choice: a qualitative study. Contraception 2018;97:243–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dehlendorf C, Grumbach K, Schmittdiel JA, Steinauer J. Shared decision making in contraceptive counseling. Contraception 2017;95:452–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Purdy L Women’s reproductive autonomy: medicalisation and beyond. J Med Ethics 2006;32:287–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.