Significance

Although the pathophysiological relevance of α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease (PD) is clearly established, its natural function and the mechanism by which it causes toxicity are not fully understood. Recruitment of α-synuclein to membranes is required for correct vesicle dynamics, while altered oligomerization at membranes can contribute to PD. We present a high-resolution structural model of α-synuclein in its oligomeric, membrane-bound state based on solution NMR and chemical cross-linking mass spectrometry (XL-MS) restraints. The obtained structures prove useful in explaining the consequences of well-known familial PD mutations and revealed a plausible mode-of-action for UCB0599, a drug designed to interfere with membrane-bound α-synuclein showing disease-modifying potential. We expect this structural information to support future research furthering our understanding of α-synuclein’s intricate functions.

Keywords: α-synuclein, oligomeric structure, XL-MS, paramagnetic NMR spectroscopy, UCB0599

Abstract

α-synuclein (αS) is an intrinsically disordered protein whose functional ambivalence and protein structural plasticity are iconic. Coordinated protein recruitment ensures proper vesicle dynamics at the synaptic cleft, while deregulated oligomerization on cellular membranes contributes to cell damage and Parkinson’s disease (PD). Despite the protein’s pathophysiological relevance, structural knowledge is limited. Here, we employ NMR spectroscopy and chemical cross-link mass spectrometry on 14N/15N-labeled αS mixtures to provide for the first time high-resolution structural information of the membrane-bound oligomeric state of αS and demonstrate that in this state, αS samples a surprisingly small conformational space. Interestingly, the study locates familial Parkinson’s disease mutants at the interface between individual αS monomers and reveals different oligomerization processes depending on whether oligomerization occurs on the same membrane surface (cis) or between αS initially attached to different membrane particles (trans). The explanatory power of the obtained high-resolution structural model is used to help determine the mode-of-actionof UCB0599. Here, it is shown that the ligand changes the ensemble of membrane-bound structures, which helps to explain the success this compound, currently being tested in Parkinson’s disease patients in a phase 2 trial, has had in animal models of PD.

α-synuclein (αS) plays a prominent role in neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and Lewy body dementia (1) by changing its oligomeric state and ultimately forming aggregates (2). The toxic αS aggregates interact with the lipid bilayer of cells and have been shown to incorporate bilayer constituents and disrupt the bilayers themselves (3–5), Lewy bodies also to a large degree consist of αS and membranes (6). In addition, binding of αS to the surface of membranes has been demonstrated to promote further aggregation in vitro (7, 8) and the mechanism of this aggregation has been investigated recently (9), although a decrease of aggregation can also be observed (10). However, regulated interaction with lipid membranes is crucial for the proper functionality (i.e., neuronal differentiation and apoptosis) (3, 4) of αS, as it is involved in SNARE complex assembly (11, 12). In addition, it regulates exocytosis by promoting dilation of vesicle fusion pores (13). Thus, detailed knowledge about the structural properties of the various oligomeric states of αS at the membrane surface is highly desirable for an understanding of its biological role and to guide drug research which aims to modify αS aggregation behavior at the membrane (14).

αS has been shown to exist in different conformations depending on the environmental context (2). Purified from mouse brain, it is a monomeric, intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) (15). In vitro studies performed on recombinantly expressed αS with circular dichroism (16) and small-angle X-ray scattering (17) also show it to be an IDP. The technique delivering the richest data on IDPs is NMR (18), and both in vitro and in-cell NMR experiments (19) have demonstrated that monomeric αS in solution is mostly disordered.

When studied in the context of membranes, monomeric αS adopts a predominantly α-helical structure. This has been demonstrated by circular dichroism, Förster resonance energy transfer, electron paramagnetic resonance, and solid-state as well as solution NMR-based studies (4, 16, 20–24). High-resolution structures were obtained for αS bound to sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) or sodium lauroyl sarcosinate-based micelles, although the orientation of helices as well as the existence of several different states is still a matter of discussion (24–28).

In mature fibrils, much of the αS sequence adopts a β-sheet fold as shown by both cryogenic electron microscopy and solid-state NMR studies (29, 30) with fibril growth including similar charge-based interactions as those observed for membrane binding (31). Oligomer formation at the membrane has been studied by several different methods (32, 33) and various different relative orientations of the α-helical structures have been proposed (34, 35). In addition, some previous work has indicated that multimers assemble from dimers in vivo, (35) while other work has shown sequential accumulation of oligomers (36).

In this study, we employ an integrated structural biology approach combining NMR spectroscopy and chemical cross-linking mass spectrometry (XL-MS) using differently isotope-labeled forms of αS to provide for the first time detailed structural information for αS oligomers formed at and bound to membrane vesicles. We show that the phase 2 compound UCB0599 modulates these oligomers and provides a plausible mode-of-action (MoA) for this new drug.

Results

Determination of Oligomeric State Distribution.

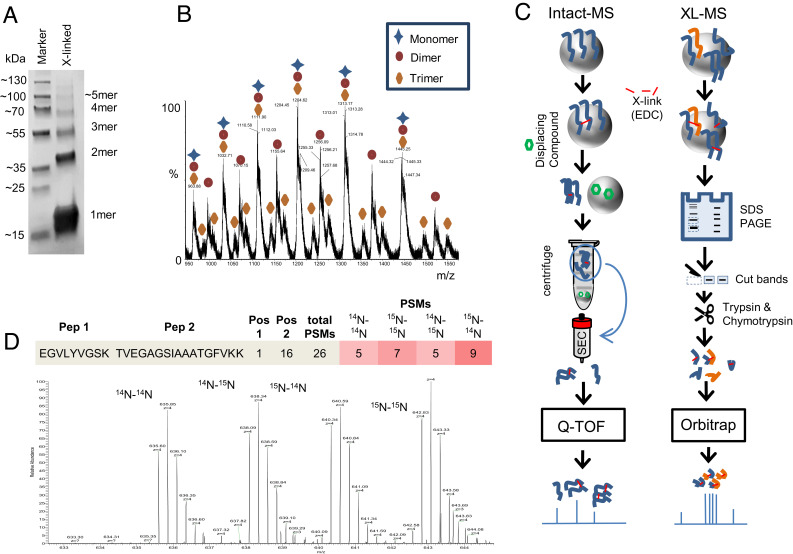

Here, we used XL-MS to probe the structural characteristics of αS in different states: monomeric SDS-micelle bound, monomeric bicelle bound, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1'-rac-glycerol) (POPG) based liposome bound, and bicelle-aggregated. The oligomer distribution of αS on membrane surface mimics (POPG-liposomes or bicelle-derived aggregates) was determined by cross-linking the protein while it is bound to the respective membrane mimic using the zero-length cross-linker 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) and detecting the oligomeric state by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (Fig. 1A). It should be noted that the experimental αS to membrane concentration ratios are expected to also occur in vivo (see SI Appendix for details). To confirm the oligomeric status seen in PAGE samples, a set of experiments was performed where the EDC cross-linked αS species were removed from the liposomes using a small-molecule compound to displace αS from POPG-based surfaces (37). The protein was separated from these liposomes by subsequent ultracentrifugation, and monomeric species present in the sample were removed by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) of the resultant supernatant. The soluble multimers obtained were subjected to intact-mass spectrometry (Fig. 1C). Most importantly, monomer, dimer, and trimer masses were clearly detected (Fig. 1B). From the observed “ladder” structure of the different oligomeric bands, it can be concluded that αS aggregation on membrane surface mimics proceeds via a stepwise oligomerization mechanism (linear growth/propagation).

Fig. 1.

Cross-linking of α-synuclein at the membrane. (A) SDS-PAGE (4 to 20%) of αS cross-linked in the presence of POPG-based liposomes and subsequent removal of liposomes followed by SEC. Molecular mass increases from monomers up to tetramers are clearly visible. Higher oligomers are present to a smaller degree. (B) Selection of m/z species showing the masses of monomeric, dimeric, and trimeric forms of cross-linked αS as detected by intact mass spectrometry post SEC. (C) Schemes for cross-linking and purification as used for detection of oligomers in intact mass (Left) and intermolecular/intramolecular cross-links of peptides (Right). A previously reported molecule that releases αS from membrane surfaces (37) is depicted as a green hexagon. (D) Spectrum demonstrating how inter- and intra-molecular cross-links can be distinguished through isotopomeric labeling. At the Top, the two different peptides detected are indicated with their cross-linking positions as well as the detected peptide spectrum matches for each combination of isotopomers. The mass spectrum allowing for this distinction is shown below.

Structural Probing of Membrane-Bound αS Using XL-MS.

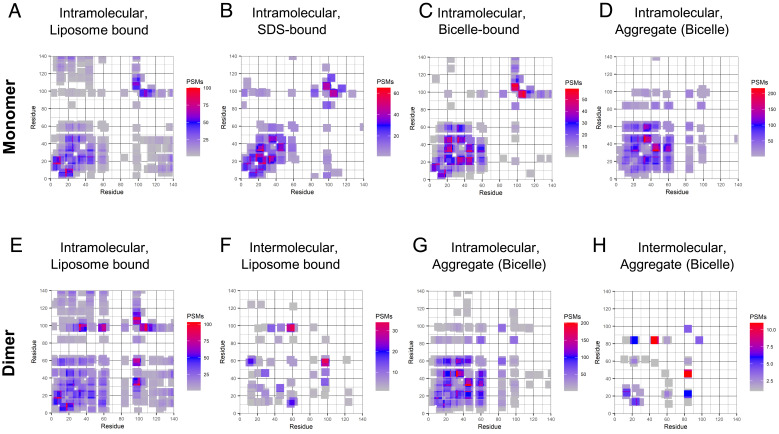

In a next step, structural investigations of liposome surface-bound αS were performed using differentially isotope-labeled (14N and 15N) proteins similar to the methodology demonstrated in ref. 38, enabling the use of an experimental strategy illustrated in Fig. 1C. Here, the analysis of individual isotopomers (14N–14N, 14N–15N, 15N–14N, and 15N–15N) allows for the discrimination of intramolecular and intermolecular cross-links. While intramolecular cross-links are exclusively observed for homoisotopomers (14N–14N and 15N–15N), intermolecular cross-links can be found for both homo- (14N–14N and 15N–15N) and hetero-isotopomeric (14N–15N and 15N–14N) forms. The prototypical MS spectrum of a cross-linked peptide shown in Fig. 1D demonstrates that the different isotopomers can be resolved and discriminated by this approach. In order to facilitate data analysis, “crosslink-contact maps” of αS were generated based on the number of peptide spectrum matches (PSMs) found for specific cross-linked residue pairs in a similar fashion as published previously (28). As this approach focuses on regions with high cross-link density, it reduces the risk of unspecific encounters between αS molecules contributing significantly to the analysis (SI Appendix, Fig. S14C). Fig. 2 A–D shows intramolecular contacts found for monomeric αS obtained for different membrane-bound states (liposome, SDS-micelle, monomeric bicelle-bound, and aggregates induced by bicelles). The majority of cross-links obtained for the various monomeric membrane-bound states of αS (a-c) are close to the diagonal and clustered at the N-terminus indicating relatively extended or slightly bent conformations. Intramolecular (homoisotopomeric) links obtained from dimer bands of αS bound to liposomes (Fig. 2E) show an overall similar pattern as the monomer band, but are enriched in specific regions. In our statistical analysis of these maps, we see the similarity of the pattern in a low Cohen’s d value, while the statistically significant change in the pattern is evaluated by the low P value (SI Appendix, Fig. S22). In the dimer band, more cross-link PSMs are observed for segments (55–65) to (90–105) and (30–40) to (90–105), indicating the higher abundance of more compact αS structures in the liposome-bound dimeric state as compared to the monomeric state. Even higher abundancies of these links were found in the trimer bands (SI Appendix, Fig. S13). In contrast, the intramolecular contact map for αS dimers obtained for the bicelle-aggregated state (Fig. 2G) is largely comparable to the bicelle-bound monomeric state (Fig. 2D), which differs in incubation time of the mix prior to cross-linking (Methods). A detailed statistical (quantitative) comparison of the obtained cross-link maps was performed by adapting a bootstrap methodology and is detailed in SI Appendix, Methods and Fig. S22.

Fig. 2.

Cross-linking patterns in α-synuclein are sensitive to conditions used. (A–D) Cross-links detected in the monomer-band of αS after incubation with various membrane mimics. The number of PSMs found in a four-residue window is indicated in the color scales. While some long-distance contacts (130–20) are observed in the liposome-bound monomer (A) and medium distances (60–35) in bicelles (C), SDS bound monomers do not show a significant amount of long-range interactions (B). Both intra- and inter-molecular contacts were detected for the bound form from the dimer band of αS (E and F). Interestingly, the intramolecular cross-linking pattern changed substantially between dimeric, bound αS (E) and the monomeric state (A) (statistical measures are available in SI Appendix, Fig. S22). Intermolecular contacts detected indicate two main regions for dimer formation (60–15 and 95–60). Note that loop-links (cross-links within a single peptide fragment) were omitted in our analysis, thus no diagonal peaks are expected. Additionally, residues located in the segment 60–80 are not amenable to the cross-linking reagents used and therefore no cross-links are observed for these residues. (G and H) When incubated with bicelles αS can form aggregates. These show dissimilar cross-linking patterns as compared to those on liposomes. Intramolecular contacts both in the monomer as well as the dimer bands (D and G) were more plentiful and show fewer medium range contacts (95–60 and 95–35). Intermolecular contacts (H), however, are less abundant and are changed drastically as compared to the liposome-bound dimer.

Mapping of the Oligomerization Interface.

Residue-resolved information about intermolecular contacts and the interaction interface was obtained by analyzing the heteroisotopomeric 14N–15N peptide cross-links. For the liposome-bound dimer state intermolecular contacts are predominantly observed for regions (90–100) to (50–65) as well as (55–65) to (10–15) and (40–50) to (25–35) (Fig. 2F). These interaction regions coincide with regions containing several of the point mutations involved in early-onset parkinsonism and have been used for the design of small-molecule therapeutic compounds (3, 39). The intermolecular interaction pattern of bicelle-aggregated αS is distinctly different (Fig. 2H and SI Appendix, Fig. S22). Since the bicelle-bound form of αS is monomeric, aggregation necessarily proceeds via interbicelle interactions (trans) rather than between two αS proteins bound to the same surface as is the case in liposomes (cis). Thus, and most importantly, the cross-link data provide evidence for different oligomeric species resulting from aggregation caused by intermolecular interactions between αS molecules bound to the same vesicle (intraliposome/cis) or located on different vesicles (interbicelle/trans), respectively.

NMR-Based High-Resolution Structure of Membrane-Bound αS.

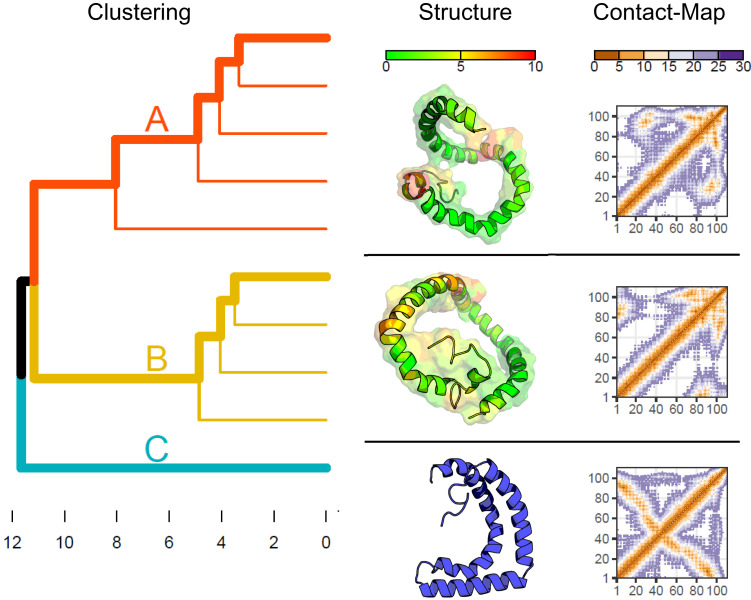

Signal assignment of αS was achieved for both the SDS-micelle (BMRB-ID 50996) and bicelle-bound states (BMRB-ID 51148) (28). The similarity between SDS-bound secondary structure propensity (SSP) data and that obtained for the bicelle-bound state (SI Appendix, Fig. S1) suggests that these structures are independent from membrane curvature and may serve as a valid model system for the membrane-bound state of αS. Due to its more favorable NMR relaxation properties, the SDS-bound state was selected for further structural characterization. NMR signal assignment of the membrane-mimic-bound state(s) in our conditions (323 K and pH = 5.5) revealed the existence of three α-helical segments largely comparable to the already reported SDS-micelle-bound state (23). In this study, we employ different NMR experiments than used previously in order to provide a larger and more comprehensive NMR data set for structural characterization of membrane-bound αS. The previous NMR study (23) largely relied on measurements of nuclear Overhauser effects (NOEs) and residual dipolar couplings. In our study, we significantly increased the number of long-range contact-dependent NMR observables and consequently the quantity of such experimental constraints in the structure calculation protocol. We employed paramagnetic relaxation enhancements (PRE) and interference (PRI) as these experiments have exquisite sensitivity and can probe even sparsely populated conformational substates (40), in contrast to conventional PREs. While the previous NMR study only involved a single PRE measurement utilizing changes in intensity, we recorded PRE-rate profiles for three independent spin label positions (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Moreover, the involvement of two additional PRI datasets (SI Appendix, Fig. S2) substantially improves the available data, as PRI experiments also provide angular constraints. The (PRE) relaxation rates obtained were not compatible with expected rates calculated from published data (SI Appendix, Fig. S3) (23), implying that additional compact conformational states must exist for αS. For the structure determination of these state(s), we adapted the well-established Xplor-NIH protein structure calculation protocol to incorporate PRE-derived distance and PRI-derived angular constraints (Methods). Additionally, NMR protein backbone chemical shift data were converted into secondary structure constraints. In order to derive an unbiased set of representative structures, an extended chain representation was used as a starting point (for details, see Methods). In Fig. 3, α-carbon to α-carbon (CA-CA) rmsd-based clustering of the 10 best solutions together with representative structures of each cluster and variations within each cluster are shown. Interestingly, one of the solutions largely corresponds to the previously determined structure (23) (cluster C in Fig. 3). Most importantly, however, the two other clusters of Fig. 3 comprise structures with a different relative orientation of the three α-helices. It is important to note that the detection of these compact states was only possible due to the substantially increased number of experimental (distance and angular) constraints and the measurement of PRI data as a sensitive probe for (globally) compacted states (40) stemming from the strong distance dependency of PREs (r−6). The quality of the obtained structures was assessed by back-calculation of PRE rates and comparison with experimental rates (SI Appendix, Fig. S19 A–C). The structures were further corroborated by comparison with intramolecular cross-link maps. Specifically, the distance map obtained for cluster B (Fig. 3, Right) shows shorter distances between the region around residue 80 to 100 and the N-terminus, which fits cross-links observed with SDS micelles (Fig. 2B), while the calculated distance map for cluster A (Fig. 3, Right) shows more similarity to the intramolecular pattern found for dimeric αS bound to liposomes (Fig. 2E and SI Appendix, Figs. S8 and S20). A thorough and quantitative assessment was performed by applying the recently developed XLmap methodology (41), an R package to visualize and score protein structure models based on sites of protein cross-linking. The calculated CMScores (SI Appendix, Fig. S20) convincingly (and quantitatively) corroborate the qualitative fits between structure and experiment (41). Taken together, the PRE and PRI experiments clearly demonstrate the presence of (at least) three conformational substates with slightly different compaction and relative orientations of α-helices. Structures within cluster C (and partly cluster B) are in good agreement with the previously determined SDS-micelle bound structure of αS (23) and likely represent the dominant state on SDS surfaces and possibly monomers on liposomes. Cluster A, however, shows structural similarity to liposome-bound dimeric forms of αS (obtained from XL-MS data) and points to the relevance of these states for membrane-induced oligomerization processes.

Fig. 3.

The PRE/PRI/SSP derived compact ensemble of α-synuclein shares features with the multimer forming ensemble at the membrane. (Left) CA-CA rmsd clustering of the 10 lowest energy structures obtained from monomer calculations. Residues 101 to 140 are excluded from the analysis as they are not constrained by experimental data. Three major clusters are indicated by different colors (A: red, B: dark yellow and C: light blue), the cluster representatives are highlighted by bold lines, rmsd [Å] is indicated at the bottom. (Middle) Representative 3D cluster structures. The surface representation includes all structures contained in the cluster aligned to the cluster representative and is colored by the maximum CA-CA distance between structures at each position. Since cluster C contains only a single structure, no common surface representation is given. (Right) CA-CA based contact map for the individual clusters. The color codes for the maximum distance in surface representations (Middle) and the distances in contact maps (Right) are indicated at the Top of each column (both given in [Å]).

Computational Modeling of Wild-Type αS Oligomers.

High-resolution models for αS dimers and higher oligomers were obtained using intermolecular XL-MS data (Fig. 2) within the Xplor-NIH structure calculation framework. Given the agreement of intramolecular XL-MS data obtained from liposome-bound αS with NMR data of SDS-bound monomer structures (Figs. 2 and 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S20), NMR structural constraints derived for the SDS-bound state were employed together with XL-MS intermolecular restraints in the calculation of the oligomers (the calculation protocol is outlined in SI Appendix, Fig. S23). Ambiguous constraints were defined based on the experimental PSMs. Specifically, the following contacts were used in the calculation: [(57, 61)–(96, 97), (10, 13)–(57, 60), (28)–(45)] (more details can be found in the Methods section). Possible structures of αS dimers were calculated assuming internal symmetry (two αS molecules with identical monomer structures in the dimer). This assumption was made as the overall conservation of cross-link patterns in dimers and trimers (SI Appendix, Fig. S13) suggests largely similar 3D structures of the different oligomers thus pointing toward a propagation mechanism which progressively links more or less structurally equivalent αS monomers. Although cluster A (Fig. 3) best reproduces the intramolecular cross-links obtained from the liposome-bound dimeric form of αS, (SI Appendix, Fig. S9A and S20) independent calculations were also performed using representative monomer structures of clusters A, B, and C (Fig. 3) as input. While the starting structures of monomer A and B are able to interconvert during the dimer structure calculation, the starting structure C—which closely resembles the previously determined SDS-micelle–bound state (23)—is locked in its starting conformation and likely represents the most populated state. Importantly, the incorporation of the new intermolecular constraints did not change the monomer structures (A and B) and thus indicate that the SDS-bound compact monomers are largely preserved in liposome-bound oligomers.

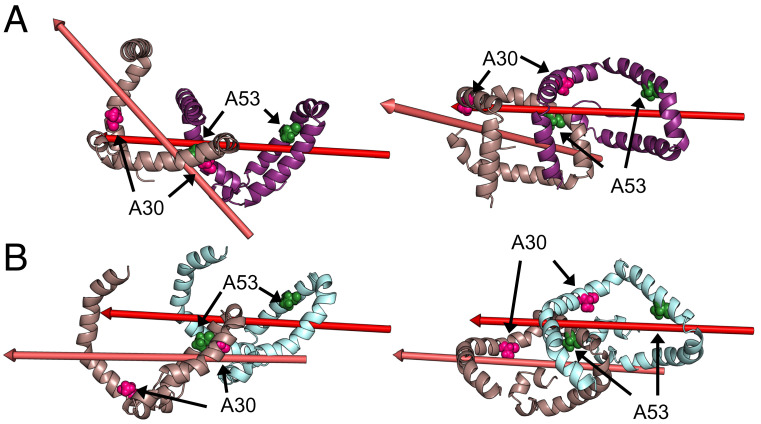

Interestingly, independent of the starting (monomer A or B) structure, only two consistent solutions for the dimer structure are found (Fig. 4). While both dimer structures share the same interaction interface between αS molecules, the relative orientation of different αS monomers in the dimer varies. This is illustrated in Fig. 4 by depicting the first major axis of the aligned monomer unit and the respective dimer solutions. Importantly, the documented familial Parkinson mutations A30P and A53T are located at the dimer interface.

Fig. 4.

Dimer structures derived from intermolecular XL-MS data. (A and B) Two prototypical solutions of the dimer calculation resembling monomer cluster A. While the interface is similar in both cases, slight deviations lead to a noticeable kink between subunits as demonstrated by the major axis of the monomers. While (A) shows an angle between the major axis of the two subunits (B) shows a near parallel offset. Mutations associated with familial forms of Parkinson’s disease and studied by XL-MS here are indicated by pink (A30) and green (A53) spheres and are located at the interface.

As αS forms oligomers on membranes, the obtained dimer structures were used to generate structural models for higher oligomers. Note that the chemical cross-link data (Fig. 1) indicate that αS oligomers are formed by progressive propagation on the membrane surface. Utilizing this information, oligomer structures were generated by joining αS dimers into larger chains, while retaining the inherent symmetry (Methods). Starting from the two dimer structures (Fig. 4), we obtain oligomeric species with distinct symmetry properties: circular structures (Fig. 5 A and B) or elongated structures with helical periodicity along the translational (propagation) axis (Fig. 5 C–F). It should be noted, however, that the structures shown in Fig. 5 are representative solutions and slightly different structures can result from minute changes in the orientation across the αS dimer interface. For example, for the circular species also other ring sizes can be obtained and, likewise, for the elongated structure, a range of twist angles are possible. Depending on the twist angle, linear αS oligomers can be continuously attached to the membrane surface (Fig. 5 C and D) or adjacent αS monomers expose their membrane attachment sites (N-terminus) to opposite sides (Fig. 5 E and F, up–down arrangement). Thus, growing αS aggregates could either cover the surface of one membrane vesicle or bridge two different vesicles. Most importantly, the obtained circular αS oligomer structure (Fig. 5 A and B) is supported by previous experimental data. For example, comparable pore diameters (~5 nm as compared to ~4 nm in Fig. 5B) were observed in EM studies of liposome-bound αS (34). Further support comes from distance measurements based ondouble electron-electron resonance experiments which are also compatible with our structures (42) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) (43) which detects particles of about ~10 nm as compared to ~11 nm in Fig. 5B.

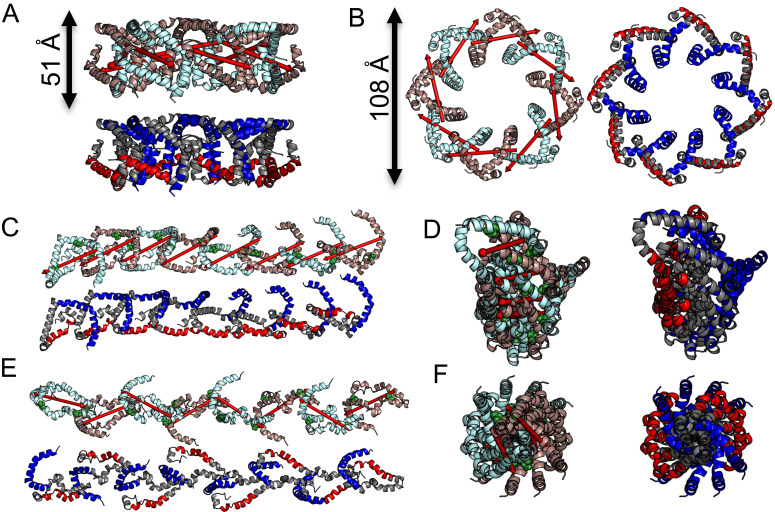

Fig. 5.

Propagation of α-synuclein into higher oligomers. Deviations of the interface demonstrated in Fig. 4 lead to distinct oligomeric structures upon further addition of monomers. Dependent on the kink between the major axes, this results in either circular (A and B) or linear/helical/extended (C–F) oligomeric structures. Individual αS molecules in the oligomers are coloured alternatingly (cyan brown) in one representation for each view [Top (A, C, and E) and Left (B, D, and F)]. Regions identified to interact with the polar head groups of the membrane surface (1–36: blue) or lipid tails within the inner layer of the lipid bilayer (70–88: red) in ref. 32 are indicated (Bottom (A, C, and E) and Right (B, D, and F)]. Ring-like structures have a height and diameter of 51 Å and 108 Å, respectively, which is in good agreement with dimensions extracted from EM-particle classifications. (C–F) Two representative structures of extended oligomers. While both oligomers form extended chains upon continuous addition of monomers, the orientation of monomers is different. Small (C and D) or large (E and F) rotational angles result in distinctly different interfaces either forming an amphiphilic-like [surface (1–36, blue) and inner layer (70–88, red) interactions on opposite sides (C and D)] or alternating [surface and inner layer interactions are alternating (E and F)] membrane interaction interface.

It is also instructive to relate our findings to published solid-state NMR data of oligomeric αS (32) which revealed the regions of αS either interacting with the lipid tail (residues 70 to 88) or the polar head groups (residues 1 to 36) of membranes. For example, insensitive nuclei enhancement by polarization transfer and dipolar-assisted rotational resonance spectra demonstrated differential mobilities for the two segments (32). The respective regions are depicted in Fig. 5 (rigid part: 70 to 88, red; mobile part: 1 to 36, blue). In the circular species, the segment demonstrated to interact with the lipid tail (70 to 88, red) is located on one side of αS while the N-terminal helix (1 to 36, blue), which is in contact with the lipid head-group, is positioned toward the top and center of the ring-like structure. The elongated form also shows a distinct distribution of lipid and head group interacting residues. Depending on the twist angle, the oligomeric form can display an amphiphilic character with both hydrophilic and hydrophobic surface. Alternatively, lipid tail and head group interaction motifs can alternate as the oligomeric propagation proceeds.

The Effect of UCB0599 on Membrane-Bound Oligomeric αS.

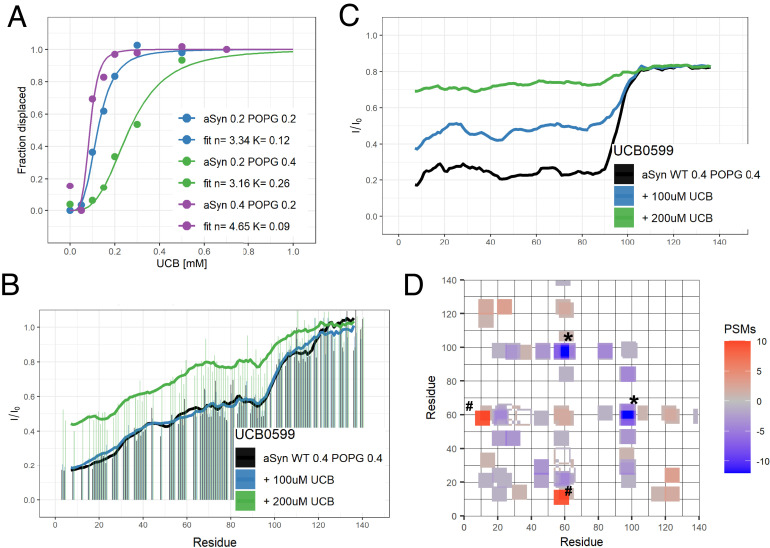

The obtained detailed structural information presented here allowed us to also gain insights into the mechanism of action of the small compound UCB0599 (SI Appendix, Fig. S18) developed to target αS in its membrane-bound state. This compound with disease-modifying potential and an acceptable safety profile (44) has entered phase 2 clinical trials as a different therapeutic strategy to combat Parkinson’s disease. The design strategy for the compound was based on the interference with and ultimate release of αS from membrane vesicles. NMR heteronuclear single quantum coherence experiments (HSQCs) were used to probe the interaction with αS and the compound-induced release of αS from the POPG-based liposomes used as membrane mimic. 15N–1H HSQC titration experiments of this compound with αS bound to POPG were performed as described previously (37). Although liposomes are beyond the size limit of NMR and, thus, do not allow for direct detection of the bound state, the measurable signal of αS reveals how much of the protein is still freely tumbling in solution. When referencing the signal intensities observed to those of αS without liposomes, we can identify the regions (and fractions) of αS bound to liposomes (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). It should be noted that while the clinical candidate is the purified enantiomer, here measurements were performed with the racemic mixture, as we have demonstrated that interactions between membrane-bound αS and the two enantiomers are identical (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Titration experiments were performed to get more detailed insights into the characteristics of the interaction between UCB0599 and membrane-bound αS (Fig. 6). Here, all detected signal intensity is stemming from unbound protein regions, and a comparison between conditions without liposomes and those with liposomes present allows for a determination of the liposome-bound fraction. Inspection of the concentration dependence (Fig. 6A) clearly reveals a pronounced cooperative transition from the membrane-bound to the free state [as also observed for NPT100-18A, an early molecule used for proof of mechanism studies (37)] indicating a specific targeting of UCB0599 to the oligomer. Most importantly, higher αS concentrations require smaller amounts of UCB0599 for displacement (as shown in Fig. 6A) indicating that the relevant species for compound binding and subsequent displacement is not monomeric αS, but rather the oligomeric state. This is further substantiated by the fact that the release is not reducing affinity for different regions of αS but releases all parts of the protein at once (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). We thus decided to analyze putative changes of the oligomeric state of αS by using low concentrations of UCB0599 insufficient to release αS from the liposome surface (Fig. 6). Most importantly, while the HSQC data (Fig. 6B) were nearly unchanged and thus confirmed the prevalence of the liposome-bound state of αS under these conditions, dark state electron-transfer (DEST) experiments (45) clearly revealed an alteration of the membrane-bound species (Fig. 6C). The decreased DEST effect (smaller signal linewidth in the bound state) suggests increased flexibility of αS in the bound state prior to displacement, presumably by weakening both (homooligomeric) interactions between individual αS units and αS interactions with the membrane.

Fig. 6.

The effect of UCB0599 on α-synuclein. Addition of the small-molecule UCB0599 to liposome-bound αS modifies the underlying ensemble at low concentration and displaces the protein at elevated ligand concentration. (A) Following the stepwise addition of the compound while referencing to the free C-terminus of the protein (SI Appendix, Fig. S5), concentration-dependent displacement of αS from POPG-based liposomes is observed. Here, signals of unbound αS regions are measured and their relative intensity between conditions with and without liposomes reports on the bound fraction. This dependence shows cooperative behavior and is dependent on the ratio between protein and liposomes. Best-HSQC (B) and DEST (C) measurements show that at lower concentrations no change in displaced αS is observed in HSQCs while an increase in DEST intensity already reflects an increase in flexibility of the bound form. When testing for changes in the bound form of the protein (D), clear changes in the cross-linking pattern are observed upon addition of the compound. Intermolecular PSMs show a reduction in links in some regions [(92–101) to (58–62), marked *] while increasing in others [(54–61) to (8–16), marked #]. These regions are found at the interface in our calculated dimer (Fig. 4A) and highlighted in SI Appendix, Fig. S7. The number of PSMs found in a four-residue window is indicated in the color scale.

In order to specifically probe UCB0599-induced structural changes in the oligomeric state, we again employ 14N/15N labeled 1:1 mixtures of isotopically labeled αS to probe XL-MS patterns of liposome-bound αS by using low concentrations of UCB0599.

The differences between intermolecular PSMs observed for αS in each form are shown in Fig. 6D (the underlying PSM maps are given in SI Appendix, Fig. S6). The addition of UCB0599 leads to clear changes of the intermolecular cross-links (Fig. 6D), while intramolecular cross-links did show relatively small fluctuations. Specifically, intermolecular interactions were less frequent between regions (94–101) and (58–62), while an increase in cross-links was observed for regions (54–61) and (8–16). These regions are located at the interface of the obtained dimer structures (SI Appendix, Figs. S7 and S12). Distinct changes of the intermolecular cross-link pattern were also observed for interfacial residues in αS versions carrying familial PD (A30P and A53T) mutations and indicate alterations of the interaction interface in membrane-bound oligomers for these pathogenic forms of αS (SI Appendix, Fig. S12). Summing up, distinct interactions exist between UCB0599 and liposome-bound αS oligomers and these interactions affect the dynamics of individual αS monomers as well as interactions across the oligomeric interface and thereby alter the oligomeric state distribution of αS, giving us a good description of the mechanism-of-action of UCB0599.

Discussion

Despite the experimental evidence linking the toxicity of αS oligomers and higher-order aggregates to the disruption of membrane integrity, little is known about the molecular-level details and how membrane permeability is modulated by αS’s oligomeric state. In this work, we utilize NMR spectroscopy to probe compact states of αS’s structural ensemble in the membrane-bound state. In combination with isotope-edited cross-linking mass spectrometry data generated with a zero-length cross-linker, we focus on the compact state of αS and derive high-resolution structural models of membrane-bound αS dimers and higher oligomers. Despite the well-established conformational flexibility (i.e., interconversion between extended and bent α-helical states) of membrane-bound αS, a surprisingly well-defined conformational ensemble was obtained with our approach. It consists of three compact states, one of which is in good agreement with the previously determined structure of SDS-micelle–bound αS (23). Importantly, however, the improved sensitivity of our integrated experimental approach (NMR spectroscopy and XL-MS, see also SI Appendix, Fig. S3) revealed the existence of an ensemble of conformational substates.

The experimental data suggest the existence of two prototypical oligomeric topologies: circular, ring-like structures and extended, twisted oligomers. Although the diameter of the circular structures and the exact twist angle of the elongated species can vary (and presumably depend on biological context and environmental conditions, i.e., additional interaction partners located at synaptic vesicles), we postulate a dynamic equilibrium between the prototypical oligomeric species. It is important to note that the oligomeric forms likely differ significantly in terms of membrane embedding and size distribution.

The circular (ring-like) structure shows features that presumably allow it to partly insert into membranes and lead to membrane distortion. Specifically, inspection of the ring-like structure in Fig. 5 suggests a plausible mechanism how αS inserts into lipid bilayers. Many amphipathic peptides can extract lipid molecules from bilayer assemblies and cause semitransmembrane defects (i.e., cathelicidin LL-37) (46) and pore disruptions (47). The distribution of hydrophobic (red) and hydrophilic (blue) residues in the ring-like structure (Fig. 5) suggests a similar insertion mechanism for αS (similarities to such a peptide are expanded upon in supplementary information SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Support for this possibility comes from an AFM study on the interaction between αS and membranes (43). AFM studies performed on planar lipid bilayers detected semitransmembrane defects induced by αS. These defects formed by lipid extraction are covered by a large number of αS nanoscale particles with a diameter of ~10 nm (43) matching the diameter of ring-like structures presented here (Fig. 5B ~11 nm). Further evidence for the plausibility of this mechanism comes from the established preference of αS for localization on liquid-disordered phases in anionic vesicles (48), where insertion into more fluid parts of the anionic vesicle is facilitated, an effect also seen in the higher affinity observed for smaller diameter vesicles (49).

In contrast, the elongated oligomeric structures can linearly propagate (without additional geometrical constraints) and form high molecular weight oligomers. Due to the inherent twist angle (Fig. 4), progressive (linear) oligomerization is not compatible with continuous membrane attachment as increasing chain length leads to a displacement of membrane-interacting residues from the surface. The proposed ultimate detachment from the membrane would, thus, lead to an oligomer with exposed interaction surfaces, which might be more prone to intermolecular interactions and subsequent aggregate formation.

We thus propose that proper regulation of the equilibrium between different oligomer topologies is crucial for the authentic functionality of αS in its biological context. The possibility to populate several oligomeric forms offers αS the possibility to interact and engage with its diverse binding partners. Conversely, misbalance or deregulation of this process might prevent proper interactions and contribute to the observed pathologies. On the other hand, interventions influencing the equilibrium or modifying the oligomeric states might alleviate pathologies that result from a misbalance of the preexisting equilibrium. Interestingly, the two well-known familial Parkinson’s mutations (A53T and A30P, see Fig. 4 B and C) are located at the interface (facing each other across the interface). Analysis of XL-MS data indicates that the overall structures of the αS monomers and dimers in the fully bound state are not strongly influenced when these point mutations are introduced while intermolecular cross-links are distinctly altered (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). We thus postulate that upon mutation, slight adaptations occur across the interaction interface and lead to a shift in the structure or prevalence of oligomeric species, which could explain the differing surface affinities observed (likely the elongated, twisted form is preferentially formed in A53T and A30P) with subsequent alterations of overall membrane affinities, as reported previously (50).

Another important finding of this study is the difference in intermolecular αS interactions depending on whether the interaction occurs on the same lipid vesicle (cis, i.e., liposomes) or between different membrane species (trans, i.e., bicelles). Importantly, both of these states show different interaction patterns than those observed in the fibrillar state, reflecting the remarkable in vivo structural heterogeneity of αS (Fig. 2) (3, 51). The data obtained in this study suggest that although the widely studied αS amyloids and their toxicity are of vital importance in PD pathology, they probably represent later stages of in vivo (in vitro) aggregation processes (2), while toxicity at the membrane is likely initially related to smaller oligomeric species with different conformations. The high amount of membrane structures and relatively low fibril content of Lewy Bodies also points toward membrane-bound αS as a main culprit in PD pathology (6). New therapeutic strategies in addition to ongoing approaches focussing on the development of antiamyloid agents disrupting large intracellular fibrils, targeting cell-to-cell propagation of misfolded beta-sheet rich aggregates or inhibiting fibril growth processes starting from protofibril “seeds” (50) might thus offer attractive opportunities. In a previous study, a small-molecule compound was identified that interferes with the initial steps of the toxicity-inducing process by altering the structural properties of membrane-bound αS and thereby preventing the subsequent formation of smaller oligomeric αS (37). Although no detailed structural information was available at that time, the hypothesis was formulated that there exists an equilibrium between different oligomeric states and that the compound reduces the conversion to propagating dimers and oligomers, as evidenced by NMR spectroscopy and electron microscopy (37). Additional development led to a compound demonstrating beneficial effects in mouse model systems (52). Building on the demonstrated mechanism, significant optimization efforts were undertaken to improve brain permeability and obtain a new molecule with pharmacological properties suitable for clinical development, yielding the compound UCB0599 (SI Appendix, Fig. S18). In contrast to the earlier compound (37), UCB0599 has much improved bioavailability and reaches the brain in sufficient quantities for clinical development. Its safety profile has also been evaluated in phase1/1b studies to support further clinical development (44). In analogy to the previous compound (37), we show a cooperative effect and increasing cooperativity at higher αS:POPG ratios, demonstrating that UCB0599 targets αS which in our conditions is present in oligomeric states. This observed cooperativity holds for all regions of the protein (SI Appendix, Fig. S5) and is sustained in point mutations (SI Appendix, Fig. S16), indicating that the oligomeric state is specifically targeted and displaced. The XL-MS and NMR data presented in our study provide strong evidence for the proposed hypothesis. Specifically, the DEST experiments (Fig. 6C) show that prior to displacement, additional flexibility is introduced to bound αS, followed by full displacement at higher concentrations. The XL-MS data (Fig. 6 and SI Appendix, Fig. S6) convincingly show that the compound leads to changes in the cross-link pattern for residues located at the interface, presumably a reflection of the same process causing increased flexibility introduced by UCB0599. Most importantly, the DEST data provided evidence that the compound affects the structural integrity (rigidity) of αS oligomers and their interactions with the membrane mimic already at low concentration. This likely diminishes membrane interactions and impairs embedding of αS oligomers into the membrane and, thus, mitigates possible semitransmembrane defects or membrane-pore formation caused by αS. Our study supports the previous hypothesis and suggests that the beneficial therapeutic effect of UCB0599 is indeed most likely due to an alteration of membrane-bound αS oligomers, the subsequent reduction in the number of membrane-bound oligomeric structures capable of seeding aggregate formation and ultimate displacement of αS from the membrane. To conclude, UCB0599 exerts its beneficial effects already in the membrane-bound state by reducing the populations and thus detrimental downstream effects of both (toxic) oligomeric forms, introducing higher flexibility to oligomers, before ultimately releasing αS in its monomeric (random-coil like) form. A model for the dynamic equilibrium of membrane-bound αS oligomers and the influence of UCB0599 is shown in Fig. 7.

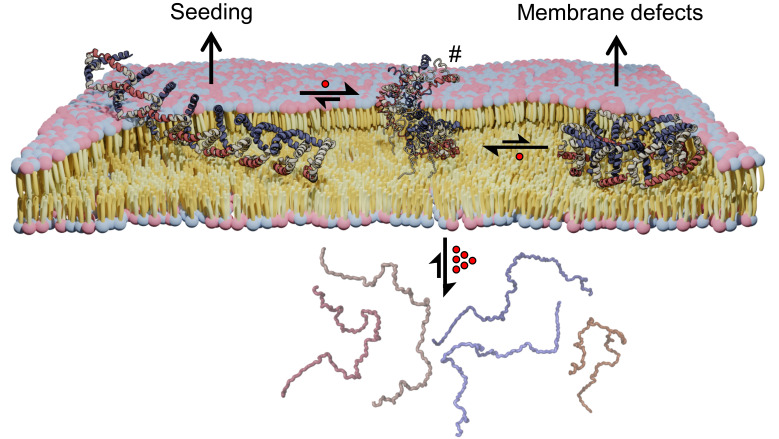

Fig. 7.

Model for membrane-bound oligomeric α-synuclein and UCB0599’s mode-of-action. The membrane-bound state of αS is characterized by an ensemble of different oligomer topologies (circular vs. elongated). While the elongated form (Left) might be involved in seeding with membranes (7) when growing too large, the circular structure (Right) is likely relevant for membrane defects and possibly pore formation (43). Proper functioning of αS requires a subtle balancing in order to avoid the formation of these toxic variants. The proposed MoA of UCB0599 involves interference with oligomeric αS on the membrane and thereby shifting the equilibrium away from species capable of generating toxic effects (elongated and circular) toward a conformational state (represented by the central cartoon marked #) characterized by increased flexibility and decreased membrane embedding. The resulting loosening of membrane-attachment facilitates displacement of αS from the membrane with UCB0599 (depicted as red spheres). At sufficiently high concentrations, αS is displaced from the membrane in a monomeric form (Bottom). Regions of αS interacting with lipid tails (red) or hydrophilic head groups (blue) are indicated (32).

Disrupting the formation of membrane-embedded αS oligomers at an early stage of aggregation before irreversible neurodegenerative processes has been initiated as a promising intervention strategy to combat Parkinson’s disease, complementing efforts to reduce amyloids. The now available (high-resolution) 3D structural information about surface-bound αS oligomers together with the XL-MS interaction data provide unique insight into UCB0599’s MoA, a molecule currently being tested in Parkinson’s disease patients in a phase 2 clinical trial. This demonstration of the potential therapeutic relevance of αS oligomer changes on membrane surfaces for Parkinson’s disease sets the stage for future intervention strategies exploiting this fundamental process. Additionally, detailed knowledge about the structural features of membrane-bound αS oligomers offers exciting possibilities to expand our understanding regarding the many facets of this still enigmatic protein.

Materials and Methods

Protein Production.

The expression and purification of recombinant human αS were carried out similarly as described previously (37). In order to obtain >95% of 15N labeling in samples used for XLMS, precultures were grown in a labeled medium. NMR samples were obtained by generating cell mass in an unlabeled medium. Samples used for assignment were produced using the same method but with D2O replacing H2O in the induced medium to partially deuterate and achieve improved TROSY efficiency (53).

Cross-Linking.

Cross-linking reactions of αS were carried similarly as published (28). As required, 50 µM 14N αS or 50 µM of a 1:1 istotopic 15N:14N mixture of αS bound to 1 mg/ml of POPG-based liposomes was incubated with 2 mM EDC and 5 mM hydroxy-2,5-dioxopyrrolidine-3-sulfonic acid for 60 min at room temperature for all cross-linking experiments containing liposomes (produced as published) (37). Despite the relatively high amount of αS relative to the liposomal surface, the majority of the protein is observed in the monomeric, bound form (SI Appendix, Fig. S14). In order to determine the effect of UCB0599 without displacement of the protein, 50 µM of the compound (racemic mixture in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)) or 1% DMSO (in the reference condition) was added. Conditions containing bicelles or SDS-micelles were generated with 100 µM of isotopically mixed αS and 15 mM bicelles (composed of 10 mM 1,2-diheptanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine and 5 mM 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1'-rac-glycerol)) or with isotopically mixed αS and 40 mM SDS, respectively. All cross-linking reactions were carried out in 50mM phosphate buffer, pH = 6.5 containing 50 mM NaCl. Cross-linking was carried out shortly after mixing the protein and membrane components with the exception of the aggregated sample where αS and bicelles were incubated at 50 °C o/n. All reactions were subjected to SDS-PAGE after being stopped with 50 mM Tris and 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Bands of the monomer and dimer forms were cut and subjected to mass spectrometric analysis.

Intact Protein Mass Spectrometry.

For intact mass measurements, unlabeled (14N only) αS was cross-linked in the presence of liposomes. After the reaction, 1 mM of the compound (37) was added to displace αS from the liposomal surface. The sample was then incubated at RT for 20 min before ultracentrifugation at 100.000 [g] for 1 h. The supernatant of this reaction was injected onto a SEC column (Superdex 75 Increase 5/150GL). We detected a peak of the monomer and a second, mixed peak. Protein solutions from the mixed peak were diluted with water to a final concentration of 5 to 10 ng/μL. Up to 30 ng of protein were injected on a nano high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Thermo Scientific, Dionex) equipped with a C4 column (AERIS C4 widepore, 3.6 µm, 150 × 4.6 mm, Phenomenex) running a step gradient from 9 to 36–63% ACN in 0.08% formic acid. The LC was coupled to the Synapt G2Si mass spectrometer via the Zspray™-ion source (both Waters) operated by MassLynx 4.1 software. The mass spectrometer was run in resolution mode, and capillary voltage was set to 3 kV cone voltage to 40 V. The source was at 120 °C, desolvation at 400 °C. Lock spray correction was applied and Glu-1-fibrinopeptide was used as lock mass. Data were acquired in the m/z range of 600 to 2,000. Spectra were summed over the peak retention time window and masses were deconvoluted using the MaxEnt1 method.

XL-MS and Data Analysis.

Isotopically mixed (14N and 15N) αS was cross-linked in the presence of liposomes as described. The resulting protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE, and bands corresponding to mono- and dimer bands were excised and destained After reduction with dithiothreitol and alkylation with iodoacetamide, trypsin and chymotrypsin were used for proteolytic cleavage. Peptides were extracted in the ultrasonication bath and desalted (54).

Peptides were analyzed on an HPLC coupled to a Q Exactive HF-X or an Orbitrap mass spectrometer, equipped with a Nanospray Flex ion source. Equal amounts of the samples were loaded on a trap column using 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid as mobile phase. After 10 min, the trap column was switched in line with the analytical C18 column and peptides were eluted applying a segmented linear gradient from 2 to 80% solvent B (80% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid; solvent A 0.1% formic acid) at 230 nL/min over 120 min. The mass spectrometer was operated in a data-dependent mode, survey scans were obtained in a mass range of 350 to 1,650 m/z with lock mass activated, at a resolution of 120,000 at 200 m/z and an AGC target value of 3E6 (HF-X) or 4E5 (Lumos). The 10 most intense ions (HF-X) were selected with an isolation width of 1.6 Thomson for a max. of 250 ms, fragmented in the higher-energy C-trap dissociation cell at 28% (HF-X) or 30% (Lumos), and the spectra were recorded at a target value of 1E5 and a resolution of 60,000. Peptides with a charge of +1, +2, or >+7 were excluded from fragmentation, peptide match was set to preferred, the exclude isotope feature was enabled, and selected precursors were dynamically excluded from repeated sampling for 20 s within a mass tolerance of 8 ppm.

Raw data were processed using the MaxQuant software package (55) (v. 1.6.0.13), and spectra were searched against a combined database of the αS construct sequence, the E. coli K12 reference proteome (Uniprot), and a database containing common contaminants.

To identify cross-linked peptides, the spectra were searched using Kojak (56) (v. 1.6.1). Raw files were converted to mzML format using msconvert in ProteoWizard (57) and searched against a database containing the 8 most abundant protein hits identified in the MaxQuant search. Carbamidomethylation of cysteine was set as a fixed modification and oxidation of methionine as variable. Trypsin/chymotrypsin was set as enzyme specificity; EDC was used for cross-linking chemistry, and the 15N mode was activated. Search results were filtered for 1% FDR (q-value < 0.01) at the PSM level using Percolator (v. 2.08). An additional PEP cutoff of < 0.05 was applied.

Due to the flexibility in our system, a large set of cross-links was observed. As the information on cross-links is too sparse to calculate reliable ensembles, we chose to make a visual representation of the average distribution of cross-links the focus of our analysis. The resulting cross-link pattern is shown as a matrix depicting contacts between positions in the primary sequence.

14N–15N and 15N–14N contacts were observed in the dimer bands of SDS-PAGE gels. PSMs detected within 14N–14N and 15N–15N isotope-labeled versions of the protein stem from both inter- and intra-molecular interactions of the protein. We, therefore, subtracted mixed isotopic contacts from those observed within each isotopic species in order to obtain the intramolecular contacts within a single αS molecule of a dimer band.

More details regarding the construction of the “PSM-matrix” and statistical treatment of the observed differences are available in supplementary methods.

NMR.

Assignment of SDS-bound αS was carried out using best versions of 3D backbone assignment pulse sequences on an AVANCE NEO 600 MHz instrument equipped with a triple resonance probe (58). Measurements were carried out on a 0.15 mM sample at 323 K with 40 mM SDS in a 20 mM phosphate buffer pH = 5.5 with 0.1 mM EDTA and 0.1 mM azide, and the resulting data along with detailed measurement parameters was deposited on the BMRB database (ID:50996) (59). Best-HSQC and DEST measurements (Fig. 6) were carried out with 0.4 mM αS and 0.4 mg/mL POPG liposomes at 35 °C, in a 50 mM phosphate buffer pH = 6.5 with 50 mM NaCl using dark state energy-transfer irradiation at +/−2 kHz offset in the nitrogen dimension with referencing to 30 kHz offset and 0.5 s of irradiation. Best-HSQC measurements in Fig. 6a also used 0.2 mM αS and 0.2 mg/ml POPG where indicated.

Molecular Structure Determination and PRI Potential.

An energy term for Xplor-NIH was developed to allow the use of experimental PRI values as restraints during structure calculation. This was implemented as a long-range angle potential that penalizes angle segments depending on the sign of the measured PRI (SI Appendix). Structures were calculated using the molecular structure determination package Xplor-NIH (60, 61). Initial monomer structure calculations were based mainly on PRE, PRI, and torsion angle restraints. In a follow up, the best monomers were used to calculate dimeric complexes by incorporating intermolecular MS-cross-links as pseudo NOEs (SI Appendix). A short graphical summary of the model generation workflow is shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S23.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (XLSX)

Dataset S02 (TXT)

Acknowledgments

Terry Baker passed away during finalization of this manuscript. He was an inspiring scientist and dedicated researcher who made countless, invaluable contributions to the discovery of therapeutic agents and will always be remembered as a great colleague. T.C.S. is grateful for funding provided by UCB Biopharma. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support to A.B. and T.H. by the Austrian Federal Ministry for Digital and Economic Affairs, the National Foundation for Research, Technology and Development and the Christian Doppler Research Association. We thank Rachel Angers for fruitful discussions and her input in finalising the manuscript, Anja-Leona Biere for continuous support of the project and Dorothea Anrather for conducting intact protein mass spectrometry. All mass spectrometry measurements were performed using the instrument pool of the Vienna BioCenter Core Facilities.

Author contributions

T.S.B., R.J.T., and R.K. designed research; T.C.S., A.B., K.L., T.G., and T.H. performed research; T.C.S., A.B., T.G., and M.H. analyzed data; and T.C.S., A.B., M.H., and R.K. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

T.S.B. and R.J.T. were employed by UCB Pharma and held stock options and shares of the same during the writing of this paper. T.C.S. and R.K. received funding from UCB Pharma and Neuropore Therapies. T.C.S., K.L., and R.K. are co-authors on a publication describing an early molecule showing a “proof-of mechanism” used by UCB0599.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Contributor Information

Thomas C. Schwarz, Email: t.schwarz@univie.ac.at.

Robert Konrat, Email: robert.konrat@univie.ac.at.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All data used to demonstrate our findings in this paper are available within the article, its SI Appendix files or in public repositories. Chemical shift assignments for SDS micelle and bicelle bound αS are deposited in the BMRB database (59) with the accession numbers 50996 and 51148. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository (62) with the dataset identifier PXD027349. Structural models of oligomeric αS are deposited on the PDB-Dev database (63) with the accession number PDBDEV_00000089.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Goedert M., Jakes R., Spillantini M. G., The synucleinopathies: Twenty years on. J. Parkinsons Dis. 7, S51–S69 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alam P., Bousset L., Melki R., Otzen D. E., α-synuclein oligomers and fibrils: A spectrum of species, a spectrum of toxicities. J. Neurochem. 150, 522–534 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong Y. C., Krainc D., alpha-synuclein toxicity in neurodegeneration: Mechanism and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Med. 23, 1–13 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Maarschalkerweerd A., Vetri V., Langkilde A. E., Fodera V., Vestergaard B., Protein/lipid coaggregates are formed during alpha-synuclein-induced disruption of lipid bilayers. Biomacromolecules 15, 3643–3654 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinreb P. H., Zhen W., Poon A. W., Conway K. A., Lansbury P. T. Jr., NACP, a protein implicated in Alzheimer’s disease and learning, is natively unfolded. Biochemistry 35, 13709–13715 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shahmoradian S. H., et al. , Lewy pathology in Parkinson’s disease consists of crowded organelles and lipid membranes. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 1099–1109 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee H. J., Choi C., Lee S. J., Membrane-bound alpha-synuclein has a high aggregation propensity and the ability to seed the aggregation of the cytosolic form. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 671–678 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perni M., et al. , A natural product inhibits the initiation of alpha-synuclein aggregation and suppresses its toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E1009–E1017 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antonschmidt L., et al. , Insights into the molecular mechanism of amyloid filament formation: Segmental folding of alpha-synuclein on lipid membranes. Sci. Adv. 7, eabg2174 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burre J., Sharma M., Sudhof T. C., Definition of a molecular pathway mediating alpha-synuclein neurotoxicity. J. Neurosci. 35, 5221–5232 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burre J., et al. , Alpha-synuclein promotes SNARE-complex assembly in vivo and in vitro. Science 329, 1663–1667 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lautenschlager J., et al. , C-terminal calcium binding of alpha-synuclein modulates synaptic vesicle interaction. Nat. Commun. 9, 712 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sulzer D., Edwards R. H., The physiological role of alpha-synuclein and its relationship to Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neurochem. 150, 475–486 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Musteikytė G., et al. , Interactions of α-synuclein oligomers with lipid membranes. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta. Biomembr. 1863, 183536 (2020), 10.1016/j.bbamem.2020.183536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burre J., et al. , Properties of native brain alpha-synuclein. Nature 498, E4–E6 (2013), discussion E6–E7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartels T., et al. , The N-terminus of the intrinsically disordered protein alpha-synuclein triggers membrane binding and helix folding. Biophys. J. 99, 2116–2124 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Araki K., et al. , A small-angle X-ray scattering study of alpha-synuclein from human red blood cells. Sci. Rep. 6, 30473 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dyson H. J., Wright P. E., NMR illuminates intrinsic disorder. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 70, 44–52 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Theillet F. X., et al. , Structural disorder of monomeric alpha-synuclein persists in mammalian cells. Nature 530, 45–50 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jao C. C., Der-Sarkissian A., Chen J., Langen R., Structure of membrane-bound alpha-synuclein studied by site-directed spin labeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 8331–8336 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uluca B., et al. , DNP-enhanced MAS NMR: A tool to snapshot conformational ensembles of alpha-synuclein in different states. Biophys. J. 114, 1614–1623 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drescher M., et al. , Antiparallel arrangement of the helices of vesicle-bound alpha-synuclein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 7796–7797 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ulmer T. S., Bax A., Cole N. B., Nussbaum R. L., Structure and dynamics of micelle-bound human alpha-synuclein. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 9595–9603 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trexler A. J., Rhoades E., Alpha-synuclein binds large unilamellar vesicles as an extended helix. Biochemistry 48, 2304–2306 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bortolus M., et al. , Broken helix in vesicle and micelle-bound alpha-synuclein: Insights from site-directed spin labeling-EPR experiments and MD simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 6690–6691 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lokappa S. B., Ulmer T. S., Alpha-synuclein populates both elongated and broken helix states on small unilamellar vesicles. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 21450–21457 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sung Y. H., Eliezer D., Structure and dynamics of the extended-helix state of alpha-synuclein: Intrinsic lability of the linker region. Prot. Sci. Publ. Prot. Soc. 27, 1314–1324 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amos S. T. A., et al. , Membrane interactions of α-Synuclein revealed by multiscale molecular dynamics simulations, markov state models, and NMR. J. Phys. Chem. B 125, 2929–2941 (2021), 10.1021/acs.jpcb.1c01281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li B., et al. , Cryo-EM of full-length alpha-synuclein reveals fibril polymorphs with a common structural kernel. Nat. Commun. 9, 3609 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tuttle M. D., et al. , Solid-state NMR structure of a pathogenic fibril of full-length human alpha-synuclein. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 23, 409–415 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumari P., et al. , Structural insights into alpha-synuclein monomer-fibril interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2012171118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fusco G., et al. , Structural basis of membrane disruption and cellular toxicity by alpha-synuclein oligomers. Science 358, 1440–1443 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lv Z., et al. , Assembly of alpha-synuclein aggregates on phospholipid bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Prot. Proteom. 1867, 802–812 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsigelny I. F., et al. , Dynamics of alpha-synuclein aggregation and inhibition of pore-like oligomer development by beta-synuclein. FEBS J. 274, 1862–1877 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burre J., Sharma M., Sudhof T. C., alpha-Synuclein assembles into higher-order multimers upon membrane binding to promote SNARE complex formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, E4274–4283 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cole N. B., et al. , Lipid droplet binding and oligomerization properties of the Parkinson’s disease protein alpha-synuclein. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 6344–6352 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wrasidlo W., et al. , A de novo compound targeting alpha-synuclein improves deficits in models of Parkinson’s disease. Brain A J. Neurol. 139, 3217–3236 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arlt C., et al. , An integrated mass spectrometry based approach to probe the structure of the full-length wild-type tetrameric p53 tumor suppressor. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 56, 275–279 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Polymeropoulos M. H., et al. , Mutation in the alpha-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson’s disease. Science 276, 2045–2047 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kurzbach D., et al. , Detection of correlated conformational fluctuations in intrinsically disordered proteins through paramagnetic relaxation interference. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 5753–5758 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schweppe D. K., Chavez J. D., Bruce J. E., XLmap: An R package to visualize and score protein structure models based on sites of protein cross-linking. Bioinformatics 32, 306–308 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Varkey J., et al. , α-Synuclein oligomers with broken helical conformation form lipoprotein nanoparticles. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 17620–17630 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pan J., Dalzini A., Khadka N. K., Aryal C. M., Song L., Lipid extraction by α-synuclein generates semi-transmembrane defects and lipoprotein nanoparticles. ACS Omega 3, 9586–9597 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smit J. W., et al. , Phase 1/1b studies of UCB0599, an Oral inhibitor of alpha-synuclein misfolding, including a randomized study in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 37, 2045–2056 (2022), 10.1002/mds.29170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fawzi N. L., Ying J., Torchia D. A., Clore G. M., Probing exchange kinetics and atomic resolution dynamics in high-molecular-weight complexes using dark-state exchange saturation transfer NMR spectroscopy. Nat. Protoc. 7, 1523–1533 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sancho-Vaello E., et al. , The structure of the antimicrobial human cathelicidin LL-37 shows oligomerization and channel formation in the presence of membrane mimics. Sci. Rep. 10, 17356 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar P., Kizhakkedathu J. N., Straus S. K., Antimicrobial peptides: Diversity, mechanism of action and strategies to improve the activity and biocompatibility in vivo. Biomolecules 8, 4 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stöckl M., Fischer P., Wanker E., Herrmann A., Alpha-synuclein selectively binds to anionic phospholipids embedded in liquid-disordered domains. J. Mol. Biol. 375, 1394–1404 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McClain S. M., Ojoawo A. M., Lin W., Rienstra C. M., Murphy C. J., Interaction of alpha-synuclein and its mutants with rigid lipid vesicle mimics of varying surface curvature. ACS Nano. 14, 10153–10167 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lashuel H. A., Overk C. R., Oueslati A., Masliah E., The many faces of α-synuclein: From structure and toxicity to therapeutic target. Nature Rev. Neurosci. 14, 38–48 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsigelny I. F., et al. , Role of alpha-synuclein penetration into the membrane in the mechanisms of oligomer pore formation. FEBS J. 279, 1000–1013 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Price D. L., et al. , The small molecule alpha-synuclein misfolding inhibitor, NPT200-11, produces multiple benefits in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease. Sci. Rep. 8, 16165 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eletsky A., Kienhöfer A., Pervushin K., TROSY NMR with partially deuterated proteins. J. Biomolecular NMR 20, 177–180 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rappsilber J., Mann M., Ishihama Y., Protocol for micro-purification, enrichment, pre-fractionation and storage of peptides for proteomics using StageTips. Nat. Protoc. 2, 1896–1906 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tyanova S., Temu T., Cox J., The MaxQuant computational platform for mass spectrometry-based shotgun proteomics. Nat. Protoc. 11, 2301–2319 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hoopmann M. R., et al. , Kojak: Efficient analysis of chemically cross-linked protein complexes. J. Proteome Res. 14, 2190–2198 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chambers M. C., et al. , A cross-platform toolkit for mass spectrometry and proteomics. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 918–920 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lescop E., Schanda P., Brutscher B., A set of BEST triple-resonance experiments for time-optimized protein resonance assignment. J. Magn. Reson. 187, 163–169 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ulrich E. L., et al. , BioMagResBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D402–D408 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schwieters C. D., Kuszewski J. J., Tjandra N., Clore G. M., The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. J. Magn. Reson. 160, 65–73 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schwieters C. D., Kuszewski J. J., Marius Clore G., Using Xplor–NIH for NMR molecular structure determination. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 48, 47–62 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perez-Riverol Y., et al. , The PRIDE database and related tools and resources in 2019: Improving support for quantification data. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D442–D450 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vallat B., Webb B., Westbrook J. D., Sali A., Berman H. M., Development of a prototype system for archiving integrative/hybrid structure models of biological macromolecules. Structure 26, 894–904.e892 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (XLSX)

Dataset S02 (TXT)

Data Availability Statement

All data used to demonstrate our findings in this paper are available within the article, its SI Appendix files or in public repositories. Chemical shift assignments for SDS micelle and bicelle bound αS are deposited in the BMRB database (59) with the accession numbers 50996 and 51148. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository (62) with the dataset identifier PXD027349. Structural models of oligomeric αS are deposited on the PDB-Dev database (63) with the accession number PDBDEV_00000089.