Significance

African swine fever virus (ASFV) is the etiological agent for the highly contagious and fatal African swine fever (ASF) in pigs. The virulence-related genes and the mechanism of immune escape of ASFV are unclear, raising safety concerns of incomplete attenuation or virulence reversion of potential vaccines. Therefore, the elucidation of the functions of ASFV-encoded proteins is critical for understanding the ASFV–host interactions and developing and designing effective vaccines. In this study, we demonstrate that pI73R, an early nucleic-acid-binding ASFV protein containing a Zα domainplays a key role in the pathogenesis of ASFV by down-regulating the host natural immune response. Our in vivo tests suggest that I73R deletion mutant is a potent live-attenuated vaccine candidate.

Keywords: ASFV, I73R, single-stranded RNA binding, immune suppression, live-attenuated vaccine candidate

Abstract

African swine fever virus (ASFV) is a large, double-stranded DNA virus that causes a fatal disease in pigs, posing a threat to the global pig industry. Whereas some ASFV proteins have been found to play important roles in ASFV–host interaction, the functional roles of many proteins are still largely unknown. In this study, we identified I73R, an early viral gene in the replication cycle of ASFV, as a key virulence factor. Our findings demonstrate that pI73R suppresses the host innate immune response by broadly inhibiting the synthesis of host proteins, including antiviral proteins. Crystallization and structural characterization results suggest that pI73R is a nucleic-acid-binding protein containing a Zα domain. It localizes in the nucleus and inhibits host protein synthesis by suppressing the nuclear export of cellular messenger RNA (mRNAs). While pI73R promotes viral replication, the deletion of the gene showed that it is a nonessential gene for virus replication. In vivo safety and immunogenicity evaluation results demonstrate that the deletion mutant ASFV-GZΔI73R is completely nonpathogenic and provides effective protection to pigs against wild-type ASFV. These results reveal I73R as a virulence-related gene critical for ASFV pathogenesis and suggest that it is a potential target for virus attenuation. Accordingly, the deletion mutant ASFV-GZΔI73R can be a potent live-attenuated vaccine candidate.

African swine fever (ASF), caused by African swine fever virus (ASFV), is a highly contagious and lethal infectious disease that affects both domestic pigs and wild boars, with mortality rates approaching 100% (1–3). The World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) includes African swine fever (ASF) in the list of animal diseases that are legally required to be reported. The first ASF outbreak in China was reported in August 2018, and it soon spread throughout Southeast Asia (4, 5) into countries such as Mongolia, North Korea, and Vietnam (6–9). Due to its highly contagious nature and devastating impact on the pig industry, ASF is considered a significant global threat.

ASFV, which is the sole member of the genus Asfivirus belonging to the family Asfarviridae, is a large, enveloped nucleoplasmic DNA virus harboring double-stranded (ds) linear DNA of approximately 170 to 190 kilobases (kb) in size, encoding >151 open reading frames (ORFs) (10). Gene expression in ASFV is regulated through precise positioning and complex temporal programming of specific promoters in the short sequences upstream of ORFs, leading to the production transcripts of defined length. Furthermore, the ASFV genome transcribes four classes of viral mRNA, including immediate early, early, intermediate, and late genes (11–13). Early proteins typically function in regulating the expression of other viral proteins or the intracellular environment of the host to promote viral replication, such as by modulating the interferon response, cell proliferation, or cell cycle of host cells (14, 15). Viral proteins expressed late are considered to be related to virus assembly, virion formation, virus release, virus virulence, and cellular apoptosis (16). The functions of most viral ORFs are unknown, and information regarding their pathogenicity is limited. Only a few ORFs have been described as potential viral factors involved in modulating immune evasion, virus–host interaction, and virulence. When generating deletion mutants via homologous recombination, certain genes have been found nonessential for the growth of the virus in macrophages in vitro. However, recent studies have indicated that the virulence of some deletion mutants, such as that of DP96R, B119L, I177L, A137L, and I226R (17–20), is markedly decreased in domestic pigs, compared with that of wild-type virus.

In this study, we identified an ASFV virulence-related gene, I73R, as a viral factor showing an extremely high transcription at the early stage of ASFV infection. The gene encodes a small RNA-binding protein that retains cellular mRNAs in the nucleus, prevents their translation, suppresses host innate immune responses, and promotes viral replication. Therefore, I73R is a critical pathogenic factor of ASFV. The I73R deletion mutant is a potential live-attenuated vaccine candidate for ASF control with a good balance of biosafety and immunogenicity profile.

Results

The I73R Gene Is Highly Conserved among ASFV Strains and Transcribed during the Early Stage of Infection.

RNA-sequencing (RNA-Seq) was performed on ASFV [strain GZ201801, (ASFV-GZ)]-infected bone marrow–derived macrophage (BMDMs) cells at various time points to obtain an overview of the viral genomic transcriptional patterns. A total of 170 ORFs were covered by the identified transcripts (Fig. 1A). ASFV transcripts were markedly increased at 6 h postinfection (hpi), reached the maximum level at 12 hpi, and then remained relatively stable until 18 hpi. Many ASFV genes showed high transcriptional levels during the early stage of viral replication. Fig. 1B shows the 20 genes with the highest transcript abundance. Of these genes, I73R had a very high transcriptional level at the early stage of infection, comparable to that of a known early gene CP204L. The I73R gene is located between nucleotide positions 172,118 and 172,336 of the viral genomes and flanked by the genes I243L and I329L. The I73R gene in the ASFV genotype II encodes a peptide of 72 amino acids. The amino acid sequence of pI73R was aligned with its homologues from 13 isolates. The results showed that the I73R gene in ASFV-GZ is identical to that of the strains isolated in China and Europe in recent years. Only a few mutations were found compared to the earlier strains isolated in Africa and Europe, suggesting that pI73R is highly conserved among ASFV strains (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Characteristics of ASFV pI73R. I73R is a conserved gene and is transcribed and expressed in the early stage of the ASFV replication cycle. (A) Heatmap demonstrating the clustering of transcriptional patterns of the ASFV genome at various time points. The abundance of ASFV transcripts was expressed as fragments per kilobase million (FPKM) and indicated using a color key (blue and red correspond to decreased and increased transcriptional levels, respectively). Each column represents one sample, while each row represents the results of hierarchical clustering. (B) The transcript levels of the top 20 genes during ASFV replication. (C) The transcriptional levels of the I73R gene at various time points. The RNAs encoding the open reading frames of I73RB646L, and CP204L were isolated from BMDMs infected with ASFV-GZ at 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 h postinfection. (D) The protein expression levels at various time points. BMDMs were infected with ASFV-GZ at an m.o.i of 1 for 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 h. The expression levels of pI73R, p72 and p30 were detected using anti-pI73R, anti-p72 and anti-p30 antibodies, respectively. β-actin was used as the loading control. (E) Subcellular localization of pI73R in BMDMs during ASFV infection. BMDMs were infected with ASFV-GZ (m.o.i = 1) for 6, 12, and 18 hpi and reacted with anti-pI73R monoclonal antibodies and Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (green). The nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue) (63×). Note: White arrows indicate the location of the cellular virus factories (VF) formed after ASFV infection. (F) Subcellular localization of pI73R in HeLa cells. HeLa cells were transfected with recombinant pI73R-Flag plasmid and probed with anti-Flag antibodies. The nucleus were stained with DAPI. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) (pseudocolored in green), DAPI (pseudocolored in blue) images were captured using a confocal microscope (63×).

Using the well-characterized ASFV early gene CP204L encoding p30 and late gene B646L encoding p72 (18, 21) as controls, the temporal expression pattern of I73R was evaluated at the transcriptional and protein levels via qRT-PCR and immunoblotting (IB), respectively. The results showed that CP204L and I73R showed very similar transcriptional kinetics and protein expression profiles, with both expressed at an early infection stage (6 hpi) (Fig. 1 C and D).

The subcellular localization of endogenous pI73R was analyzed by probing ASFV-GZ-infected BMDMs at 6, 12, and 18 hpi with the pI73R monoclonal antibody via IFA. The results revealed that ASFV pI73R was localized in the nucleus during the early stage of infection but was found both in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm during the middle and late stages of infection (12 to 18 hpi) in a punctate pattern (Fig. 1E). The subcellular localization of pI73R was also evaluated in HeLa cells transfected with a pI73R-Flag–expressing plasmid. Staining of HeLa cells with an anti-Flag antibody showed that pI73R was localized in the nucleus (Fig. 1F). These results suggest that pI73R is an early viral protein that is mainly localized to the nucleus; but the subcellular localization is dynamic in a time-dependent manner during viral replication.

ASFV pI73R Significantly Inhibits the Protein Synthesis in Host Cells.

Luciferase (Rluc) assay was performed with a nonspecific reporter gene (Renilla gene) to examine the effects of pI73R on the intracellular environment of host cells. HEK-293T cells were cotransfected with the Flag-tagged pI73R (pI73R-Flag) or empty vector (pCAGGS) and pRL-TK plasmids (expressing thymidine kinase [TK] promoter-driven Rluc). Next, the activity of Renilla luciferase was examined using a dual-specific luciferase assay kit (Promega). The expression of Rluc in Flag-tagged pI73R plasmid-transfected cells was significantly lower than that in control cells (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, to investigate the step at which pI73R affects, qRT-PCR analysis was performed with cycloheximide (CHX)-treated cells. The results showed that the levels of Rluc mRNA in pI73R-overexpressing cells were significantly down-regulated when compared with those in control cells in the presence or absence of CHX from 12 to 24 h (Fig. 2B), suggesting that pI73R down-regulated the expression of Rluc at the transcriptional level. To determine the effects of pI73R on cellular protein synthesis, we addressed the global translational efficiency by ribopuromycylation assay (22). Gel electrophoresis revealed that overall protein synthesis was down-regulated in HEK-293T cells overexpressing pI73R (Fig. 2C, left panel). To determine whether this inhibition also occurred in swine cells, pig alveolar macrophage (PAMs) and BMDMs were prepared to further validation with exogenous I73R-mRNA (the mRNA of I73R gene was prepared by using a series of in vitro transcription kits, see SI Appendix, Materials and Methods for details). The result showed that the introduction of pI73R mRNA significantly inhibited the synthesis of host proteins as well (Fig. 2 C, Middle and Right). These findings collectively suggest that pI73R broadly suppresses host protein synthesis by regulating host mRNAs.

Fig. 2.

Broad-spectrum inhibition of host protein synthesis by ASFV pI73R. (A) Luciferase (Rluc) assay was performed to detect the effects of pI73R on the Rluc reporter gene. At 24 h posttransfection, cell extracts were also subjected to IB (Bottom) and Rluc assay (Top). Error bars indicate SD of means from three independent experiments; (***P < 0.001 was considered extremely significant). (B) The effect of exogenous pI73R on Rluc mRNA production was determined using qRT-PCR at 12 and 24 h when the cells were pretreated with or without CHX. Error bars indicate SD of means from three independent experiments. Means between different groups were compared using two-tailed Student’s t tests; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (C) HEK-293T (Left), PAM (Middle), and BMDM (Right) cells were transfected with the pCAGGS or pI73R-Flag plasmid. The cells were pulsed with 3 μM puromycin for 1 h at 24 hpt, and whole-cell lysates were obtained and subsequently subjected to IB with anti-puromycin and anti-Flag antibodies. (D) BMDMs were transfected with pI73R mRNA for 24 h, followed by infected with the ASFV-GZ strain for 6, 12, and 18 h and subsequently subjected to IB with anti-p30 and anti-HA antibodies. (E) BMDMs were transfected with pI73R mRNA for 24 h, followed by ASFV-GZ infection for 6, 12, 24, 36, or 48 h. ASFV titers were determined using the median tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) method. Data represent mean ± SDs. The sensitivity limit of virus detection was 102.45 TCID50/mL. (F) Schematic representation of the I73R gene deletion/insertion region in ASFV-GZ. All transfer vectors were designed to have 1.2-kb homology arms on both sides of the deletion/insertion cassette (represented as dashed lines), which induced deletion/insertion in the indicated viruses in the area between the dashed lines. (G) In vitro growth characteristics of recombinant mutants and parental ASFV-GZ virus. PAMs or BMDMs were infected with the viruses at an m.o.i of 0.1. The virus yields were titrated at the indicated time points postinfection. Data represent means and SDs. The sensitivity limit of virus detection was 102.45 TCID50/mL. (H) Cellular protein synthesis during ASFV and ASFV-GZΔI73R infection. PAM (Left) or BMDM (Right) cells were infected with ASFV-GZ (m.o.i = 1) or ASFV-GZΔI73R (m.o.i = 10). After 18 hpi, the cells were labeled with 3 mM puromycin for an additional hour. The whole-cell lysates were subjected to IB analysis.

ASFV I73R Is a Nonessential Gene for the Viral Replication but Plays an Important Role for Infection In Vitro.

To investigate the regulatory effect of pI73R on ASFV replication, BMDMs were transfected with I73R mRNA for 24 h and subsequently infected with ASFV at a multiplicity of infection (m.o.i) of 1. Viral replication was then evaluated via IB. The results showed that the expression of p30 protein in I73R mRNA-transfected cells was significantly up-regulated when compared with that in the mock-transfected cells after 6 h of infection (Fig. 2D). Quantification of the viral titers, which were determined using the median tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) method, in the supernatant revealed that exogenous pI73R promoted ASFV replication (Fig. 2E). This indicates that pI73R plays an important role in ASFV infection in vitro.

Next, a recombinant virus with the I73R deletion was successfully generated via homologous recombination through cotransfection with the transfer vector, followed by infection with the ASFV-GZ wild-type strain as described previously (Fig. 2 F, Middle) (23). The deletion mutant was purified via successive rounds of plaque purification and limiting dilution. PCR was performed to ensure the absence of the parental ASFV-GZ strain and to confirm the desired deletion in each recombinant strain (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). The purified recombinant strain was named ASFV-GZΔI73R. The genome sequence of the recombinant strain was analyzed via nanopore sequencing, verifying the successful deletion of I73R. The growth kinetics of ASFV-GZΔI73R were evaluated in its target primary cells [PAMs, BMDMs and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)] and compared with those of ASFV-GZ at various time points. The growth patterns of ASFV-GZΔI73R in these three types of primary cells were similar. However, compared with that of parental strain, the replication of ASFV-GZΔI73R decreased at 12 hpi and was stable until 96 hpi. The virus yields were significantly reduced (by 10-fold to 100-fold) at 48 and 96 hpi (Fig. 2G). These findings suggested that the I73R gene is a nonessential gene for replication, but nonetheless plays an important role in virus production in vitro.

Additionally, cellular mRNA translation, which was analyzed using the ribopuromycylation assay, was significantly down-regulated in ASFV-infected PAMs and BMDMs (Fig. 2H). This was consistent with the results of previous studies (24, 25). Moreover, I73R deletion significantly restored host protein levels (Fig. 2H), indicating that ASFV pI73R plays an indispensable role in the inhibition of host protein synthesis.

ASFV pI73R Is a High-Affinity RNA-Binding Protein.

The I73R protein fused with the 6× His-tag was expressed and purified to examine the molecular mechanisms underlying the pI73R-mediated inhibition of host protein synthesis. pI73R was crystallized in the H32 space group and diffracted to a resolution of 2.6 Å. The electron density was sufficient to trace the entire chain (statistics listed in Table. 1 and Dataset S1). The crystal structure of pI73R revealed that the monomer comprised a winged helix-turn-helix domain with two antiparallel β-strands and three α-helices (Fig. 3A), which are typical characteristics of the Zα domain. Furthermore, pI73R function was analyzed using the Phyre2 server. Several proteins with similar structures were identified, including human Zα-domain-containing protein (ADAR1), mouse Zα-domain-containing protein (ZBP1) and viral Zα-domain-containing protein (poxvirus E3L and herpesvirus ORF112), with a rmsds of 1.40, 1.45, 1.93, and 2.56 Å, respectively (Fig. 3 B and C). Thus, ASFV pI73R may belong to the family of Zα-domain–containing proteins, which are known to bind nucleic acids.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| I73R | |

|---|---|

|

Data collection | |

|

Space group |

H 3 |

|

Cell axial lengths (Å) |

90.54, 90.54, 49.39 |

|

Cell angles (°) |

90.00, 90.00, 120.00 |

|

Wavelength |

0.97915 |

|

Resolution range (Å) |

26.15 to 2.59 |

|

Completeness (%) |

96.7 (80.1) |

|

Rmerge (last shell) |

0.07 (0.18) |

|

I/σ (last shell) |

28.82 (11.28) |

|

Redundancy (last shell) |

9.5 (6.9) |

|

Refinement | |

|

Resolution (Å) |

26.14 to 2.59 |

|

Rwork/Rfree |

0.191/0.245 |

|

No. of reflections |

4315 |

|

No. of protein atoms |

1211 |

|

No. of solvent atoms |

41 |

|

No. of ions/ligands |

0 |

|

RMSD | |

|

Bond length (Å) |

0.68 |

|

Bond angle (°) |

0.81 |

|

B factor (Å2) |

41.69 |

|

Ramachandran plot: core, allow, disallow |

96%, 3%, 1% |

The highest-resolution values are indicated in parentheses.

Rmerge=∑∑| Ii−| /∑∑Ii; where Ii is the intensity measurement of reflection h, and is the average intensity from multiple observations.

Rwork=∑||Fo|−|Fc|| /∑|Fo|; where Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factors, respectively.

Rfree is equivalent to Rwork, but 5 % of the measured reflections have been excluded from the refinement and set aside for cross-validation.

Fig. 3.

ASFV pI73R is a high-affinity nucleic acid-binding protein. (A) Crystal structure of pI73R. The monomer structure of pI73R is shown as a colored cartoon (Left). The alpha-helices and beta-sheets are colored green and purple, respectively. The topology diagram of pI73R is also shown (Right). (B and C) Structural alignment of pI73R (gray) with human ADAR1 (cyan, PDB ID 2GXB), mouse ZBP1 (green, PDB ID 1J75), poxvirus E3L (yellow, PDB ID 1SFU), and herpesvirus ORF112 (brown, PDB ID 4HOB). (rmsd values = 1.40, 1.45, 1.93, and 2.56 Å, respectively). (D) EMSA was performed for analysing the binding between ASFV pI73R and nucleic acids. pI73R was assayed at various concentrations (0, 20, 40, 80, and 160 μM) with 1 μM 5′-Cy5-labeled ssRNA fragments. Arrow indicates the mobility shift of Cy5-labeled oligos. (E) BLI was performed for analyzing the binding kinetics between pI73R and nucleic acids. The pI73R protein was diluted to a concentration of 10 µg/mL in kinetics buffer, and loaded onto HIS1K biosensors, and incubated with twofold serially diluted nucleic acids (ssRNA, dsRNA, ssDNA, or dsDNA).

To investigate whether the pI73R has a nucleic-acid–binding activity, the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and biolayer interferometry (BLI) assay were performed to evaluate the affinity of pI73R for dsDNA, single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), dsRNA, and single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) (randomly selected oligonucleotides with sequences listed in SI Appendix, Table S2). The EMSA results showed a strong binding activity of pI73R to the various oligonucleotides tested, as evidenced by their altered mobility in the gel in a dose-dependent manner with respect to p173R concentration (Fig. 3D). Moreover, the affinity of pI73R for the ssRNA fragments was significantly higher than that for the ssDNA, dsDNA, and dsRNA fragments. Similar results were obtained with the BLI assay. The Kd values for ssRNA, dsRNA, ssDNA, and dsDNA were 37.5 nM, 70 nM, 113 nM, and 100 nM, respectively (Fig. 3E). These data demonstrated that ASFV pI73R is a high-affinity ssRNA-binding protein.

ASFV pI73R Specifically Binds to Host mRNAs with High GC Content, and Promotes Their Nuclear Retention.

To characterize the RNA-binding specificity of pI73R during ASFV infection, a recombinant ASFV-GZmI73R-HA strain was generated in which pI73R was tagged with the human influenza virus hemagglutinin tag (HA) at the carboxyl end (Fig. 2 F, Bottom). The expression levels of HA-tagged pI73R, p30 (as an early marker protein), and p72 (as a late protein marker) were assessed via IB in infected BMDMs. pI73R-HA was expressed at physiological levels, and the expression pattern was consistent with that of pI73R of the parental ASFV-GZ strain (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Next, RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (RIP-Seq) was performed using BMDMs infected with the ASFV-GZ-mI73RHA strain (Fig. 4A). The pI73R–RNA complexes were enriched using the anti-HA-tag antibodies (CST). The eluted RNA was analyzed via high-throughput sequencing technology. The RNA yields were determined via a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The quantity of RNA in the pI73R group was > threefold higher than that in the control group [immunoglobulin G (IgG)] (Fig. 4B). RIP-Seq revealed that pI73R specifically enriched 1,764 transcripts (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, most of them are encoded by the host cells. As shown in Fig. 4D, only four transcripts from ASFV were detected with very weak enrichment (SI Appendix, Table S3). These results show that pI73R preferentially binds to host cellular RNAs during ASFV infection. To evaluate the accuracy of our RIP-Seq results, 20 immune-related genes from the transcripts pulled down by pI73R were randomly selected for qRT-PCR analysis. The results verified the RIP assays results (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

Fig. 4.

ASFV pI73R binds specifically to host mRNAs, especially to ssRNA with a high GC content. (A) Flowchart of the RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assay. (B) RIP assay was performed with lysates from BMDMs infected with the ASFV-GZ-mI73RHA strain. Whole-cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with the endogenous target anti-HA mAb, with a matched IgG mAb served as the control. RNA yields were determined using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Data are presented as mean ± SD. Means were compared using unpaired t tests; ***P < 0.001, n = 3. (C) Venn diagram demonstrating the specific binding of cellular mRNA to ASFV pI73R. (D) Venn diagram demonstrating the specific binding of viral mRNA to ASFV pI73R. (E) Finding of predicted pI73R-binding motifs from the RIP-Seq data. (F) EMSA was performed with purified pI73R and 5′-Cy5-labeled with high-GC and GC-free ssRNA. Arrow indicates mobility shift of Cy5-labeled oligos. (G) RIP and RT-PCR for detecting the interaction between pI73R and TNF-α mRNA (Upper: qRT-PCR for TNF-α mRNA, lower panels: immunoblotting for pI73R). (H) MS2/MCP reporter system for detecting the migration of TNF-α mRNA (Upper: Schematic describing the constructs used in this approach. The system comprises two components, a reporter mRNA and a MS2-GFP fusion protein. The reporter mRNA containing 12x MS2-binding sites was introduced after the stop codon of TNF-α mRNA sequences. Lower panel: Re Representative images of cells expressing the pMS2-GFP and the TNF-α-12x MS2 reporter mRNA.) (I) ISH images revealed that in contrast to the empty vector control, pI73R retained the TNF-α mRNA in the nucleus. (J) Representative images of cells transfected with plasmids of pI73R fused with various nuclear export signals (pI73R/Wild, pI73R/SMAD4NES, pI73R/MEK1NES, pI73R/CPEB4NES). The nuclei were stained with DAPI. Red fluorescence protein (RFP) (pseudocolored in red) and DAPI (blue) images were captured using a confocal microscope (63×). (K) HEK-293T cells were transfected with the pCAGGS or pI73R/Wild, pI73R/SMAD4NES, pI73R/MEK1NES, and pI73R/CPEB4NES for 24 h. Next, the cells were pulsed with 3 μM puromycin for 1 h, and whole-cell lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoblotting with anti-puromycin and anti-Flag antibodies.

To further investigate the regulatory mechanism of pI73R for mRNA binding, we searched for de novo pI73R-binding motifs in the transcripts identified via RIP-Seq. Strikingly, a class of consensus motif sequence with high GC content was identified (Fig. 4E). To validate this observation, 5′-CY5-labelled high GC content and GC-free ssRNAs were prepared. Next, EMSA was performed to compare the binding of high GC content and GC-free ssRNAs to pI73R. The results suggest that pI73R exhibits a preference for binding to high-GC ssRNA over GC-free ssRNA, with weaker binding observed for the latter (Fig. 4F). These results support the interpretation that high GC content is the key element for pI73R binding to RNA targets.

Next, an mRNA with high GC content (61%) (the host cytokine TNF-α) was selected as a model to investigate the regulation mechanism of inhibition of protein synthesis by pI73R. To determine whether pI73R specifically binds to the TNF-α, Flag-tagged pI73R plasmid-transfected HEK-293T cells were subjected to RIP assay with anti-Flag-tag antibodies (ProteinTech). Exogenously expressed pI73R bound and pulled down the endogenous TNF-α mRNA (Fig. 4G). Given that pI73R is a high-affinity RNA-binding protein and localizes to the nucleus during the early stage of infection, we speculated that pI73R might also function in controlling mRNA localization. To test this hypothesis, an MS2 bacteriophage system was designed to label intracellular TNF-α mRNA molecules (Fig. 4 H, Top). HEK-293T cells overexpressing pI73R were cotransfected with the pTNF-α-MBS (MS2-binding site) and green fluorescent protein-tagged pMS2 plasmids [pMS2-Green fluorescent protein (GFP)]. GFP aggregation was observed in the nucleus, indicating that pI73R affected the nuclear export of TNF-α mRNA (Fig. 4 H, Bottom). Thus, pI73R retained TNF-α mRNA in the nucleus. Consistent with this hypothesis, the results of RNA in situ hybridization assay (ISH) revealed that in contrast to the empty vector, the exogenously expressed pI73R retained TNF mRNA in the nucleus (Fig. 4I). Together, these findings demonstrate that pI73R promotes the nuclear retention of TNF-α mRNA.

Next, the TNF-α–mediated transcriptional activation of downstream genes in pI73R-overexpressing HEK-293T cells was examined via RNA-seq. The results revealed that two types of downstream gene transcription were significantly inhibited, including the TNF-α (hsa04668) and the NF-κB (hsa04064) signaling pathway. These results were verified via qRT-PCR (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A and B). These observations further support the experimentally validated specific binding of pI73R to host mRNAs with high GC content and pI73R-mediated nuclear retention of host mRNAs.

Nuclear Location of pI73R Is Critical for the Inhibition of Host Protein Synthesis.

The role of nuclear localization of pI73R in inhibiting host protein synthesis was examined. To do this, we generated three expression plasmids in which pI73R was fused to different nuclear-export signals (NESs), specifically SMAD4, MEK1, and CPEB4 NESs. Fig. 4J shows that all three NESs successfully altered the subcellular localization of pI73R from nuclear to cytoplasm. We then performed a ribopuromycylation assay to determine the effect of the pI73R-NES on the suppressive effect of pI73R on host protein synthesis. Fig. 4K demonstrates that nonnuclear localized mutant forms of pI73R lost their ability to inhibit the host protein synthesis. These findings indicate that nuclear localization of pI73R is critical for its suppressive effect on host protein synthesis.

Deletion of I73R Results in a Complete Loss of Virulence.

The virulence of the ASFV-GZΔI73R deletion mutant was evaluated using commercial domestic piglets weighing 10 to 15 kg each. Following infection (103.0 TCID50/dose or 105.0 TCID50/dose), the body temperature and other clinical symptoms were monitored for 28 d. Additionally, the symptoms were scored using a previously described clinical scoring system (23, 26). As expected, pigs infected with ASFV-GZ exhibited increased body temperature (> 40 °C) at 3 to 5 d postinfection (dpi) (Fig. 5A and Table 2), followed by the appearance of ASF-related clinical signs, including depression, loss of appetite, purple skin discoloration, and diarrhea (Fig. 5B). These symptoms worsened with time, and all the pigs died within 9 d (Fig. 5C). However, the pigs infected with the ASFV-GZΔI73R strain did not exhibit any ASF-related clinical signs or symptoms during the 28-d observation period (Fig. 5 A and B). Similarly, all the mock-infected pigs remained clinically healthy. ASFV genomic DNA in the whole blood of the pigs was examined on days (D) 0, 3, 5, 7, 9, 14, 21, and 28 postinfection (dpi). As shown in Fig. 5D, the pigs infected with ASFV-GZ developed high viremia on 3 dpi. The genomic DNA levels were 102.91 to 105.74 copies/mL at 3 dpi and increased to 107.81 to 109.02 copies/mL at the time of death. However, pigs infected with ASFV-GZΔI73R had remarkably low viremia (102.55 to 103.85 copies/mL) between D 9 and 14 and undetectable levels between D 21 and 28. These results validated that deletion of I73R completely attenuated the virulence of the parental ASFV-GZ strain.

Fig. 5.

Evaluation of the ASFV-GZΔI73R deletion mutant in vivo. (A) The rectal temperature of pigs inoculated with 103.0 or 105.0 TCID50 of ASFV-GZΔI73R (green and blue, respectively) or the parental ASFV-GZ strain (dark red). (B) The clinical score was calculated after pigs were intramuscularly (i.m.) inoculated with 103.0 or 105.0 TCID50 of ASFV-GZΔI73R or the parental ASFV-GZ strain. (C) Survival outcomes of the pigs after inoculation with ASFV-GZΔI73R during the 28-d observation period. (D) Viremia (shown as viral DNA copies) in all groups of pigs after inoculation. (E and F) Viral shedding in oral and anal swabs were detected via qPCR against the p72 gene after inoculation. (G) Pathogenic scores were calculated in all groups of pigs and compared with those of the placebo control group. (H) Viral DNA copies in the tonsil, liver, spleen, lung, inguinal lymph node (LN), kidney, mesenteric LN, and thymus in the ASFV-GZΔI73R group were compared with those in the parental ASFV-GZ group. The sensitivity of viral DNA detection was ≥log102.45 copies/mL.

Table 2.

Swine survival and clinical presentations after inoculation in safety experiments

| Groups | No. of survivors |

Time to death [Mean (SD)] (days) |

Data for fever [mean (SD)] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| onset (days) | Duration (days) | Maximum rectal temp (°C) | |||

| ASFV-GZ 1 | 0/3 | 7.0 | 3.3 | 4 to 5 | 41.7 |

| ASFV-GZΔI73R (103.0TCID50) | 5/5 | / | / | / | 39.0 |

| ASFV-GZΔI73R (105.0TCID50) | 5/5 | / | / | / | 40.0 |

Viral shedding was assessed via both oral (Fig. 5E) and anal (Fig. 5F) swabs. The oral swab analysis of pigs infected with the ASFV-GZ strain revealed a high level of viral shedding at 5 dpi with a mean viral DNA level of 106.91 copies/mL. However, no viral shedding was detected in the pigs inoculated with ASFV-GZΔI73R during the entire observation period.

Furthermore, a necropsy was performed on the dead pigs inoculated with the ASFV-GZ strain. The surviving pigs that were inoculated with the ASFV-GZΔI73R deletion mutant and those in the control group were euthanized and subjected to necropsy at the end of the observation period. The pathogenic scoring system for gross lesions on all mentioned organs has been described previously (Table 4) (26). The pigs infected with the ASFV-GZ strain showed classic acute ASF disease, with severe gross lesions (scores, 28 to 38), and high viral loads (>105.5 TCID50/100 mg) in almost all the collected samples at the time of death (Fig. 5H). However, necropsy analysis of all pigs inoculated with the ASFV-GZΔI73R strain revealed physiological results irrespective of the inoculum size although the individual lymph nodes (LNs) were slightly swollen or hyperaemic. Additionally, no viral DNA was detected in any tissue samples, indicating that the ASFV-GZΔI73R strain was completely cleared during the 28-d observation period (Fig. 5H). Histopathological examination revealed that compared with the pigs in the control group, all the ASFV-GZ-infected pigs exhibited evident hemorrhagic necrosis and necrosis of lymphocytes and neutrophils, whereas pigs inoculated with the ASFV-GZΔI73R strain exhibited healthy tissues (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). These results indicated that I73R deletion results in a complete loss of virulence and pathogenicity.

Table 4.

Swine survival and clinical presentations after challenge in efficacy experiments

| Groups | No. of survivors |

Time to death [Mean (SD)] (days) |

Data for fever [mean (SD)] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| onset (days) | Duration (days) | Maximum rectal temp (°C) | |||

| ASFV-GZ 2 | 0/3 | 8 | 3.3 | 5-7 | 42 |

| ASFV-GZ 3 | 0/3 | 8.3 | 3.7 | 5-7 | 42.4 |

| ASFV-GZΔI73R | 3/3 | / | 6 | 7-8 | 40.9 |

ASFV-GZΔI73R Provides Effective Protection as a Vaccine Candidate.

To investigate the protective efficacy of the ASFV-GZΔI73R strain against challenge with the parental ASFV-GZ strain, three pigs were intramuscularly (i.m.) injected with 103.0 TCID50 of ASFV-GZΔI73R. The behavior of ASFV-GZΔI73R-infected pigs was compared with that of the naïve pigs (n = 3) inoculated with 104.0 TCID50 of ASFV-GZ. Additionally, three unvaccinated pigs were incorporated into the ASFV-GZΔI73R group as sentinels to detect the presence of viral shedding in the inoculated pigs. After the 28-d observation period, all the pigs inoculated with the ASFV-GZΔI73R strain were i.m. injected with 104.0 TCID50 of the parental ASFV-GZ strain. Simultaneously, an additional group of naïve pigs (n = 3) was included as a mock-vaccinated control group and challenged under the same conditions.

All the mock-vaccinated pigs exhibited increased rectal temperature (>40 °C) after 3 to 5 d of ASFV-GZ challenge (Fig. 6A), followed by the appearance of ASF-related signs after 4 to 7 d. These symptoms progressed over time, and all the pigs died within 9 d (Fig. 6 B and C). However, the pigs inoculated with ASFV-GZΔI73R developed low-grade fever (temperature, <41°C) for only a short duration after challenge. The temperature subsequently returned to physiological levels, suggesting that the vaccinated pigs were protected (Table 3).

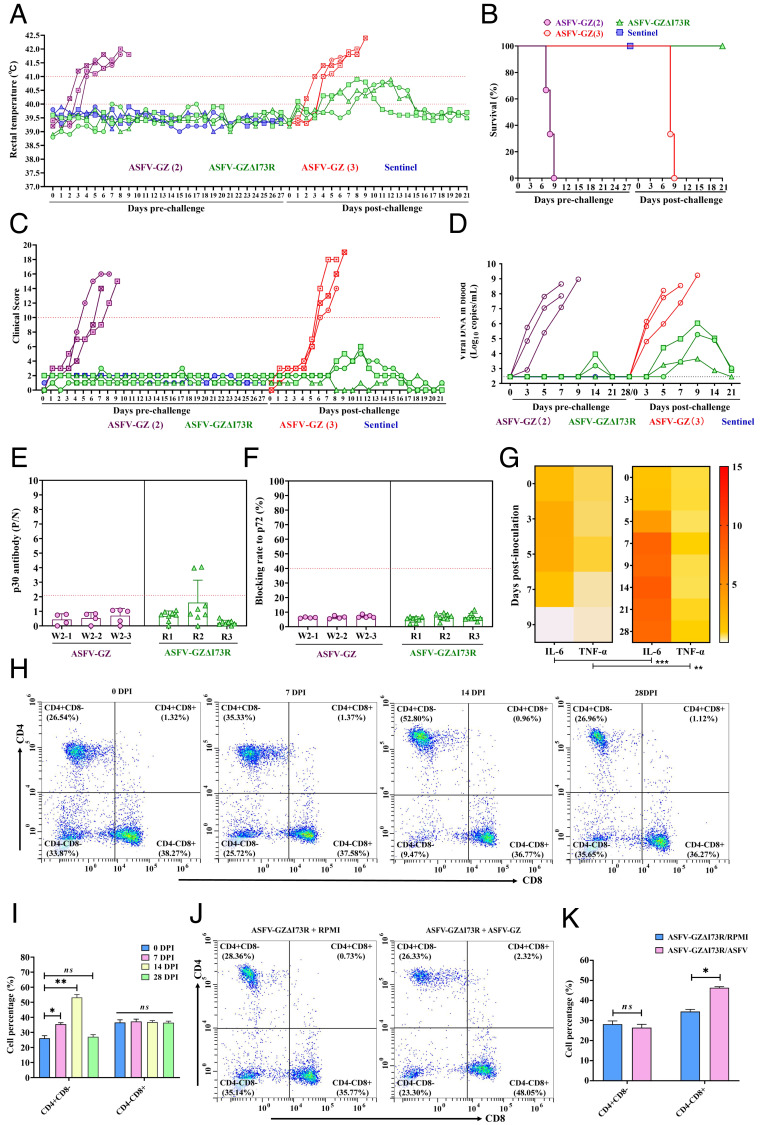

Fig. 6.

Protective efficacy of ASFV-GZΔI73R against challenge with parental ASFV-GZ. (A) The rectal temperature of pigs inoculated with 103.0 TCID50 of ASFV-GZΔI73R (green), sentinel (blue), or 104.0 TCID50 of ASFV-GZ (purple, ASFV-GZ 2) before and after challenge with 104.0 TCID50 of ASFV-GZ virus (red, ASFV-GZ 3). (B) Survival outcomes of pigs after intramuscular inoculation and challenge. (C) The clinical score of pigs inoculated with 103.0 TCID50 of ASFV-GZΔI73R (green), Sentinel (blue), or 104.0 TCID50 of ASFV-GZ (purple, ASFV-GZ 2) before and after challenge with 104.0 TCID50 of ASFV-GZ virus (red, ASFV-GZ 3). (D) Viremia (shown as viral DNA copies) in all groups of pigs after inoculation and challenge. (E and F) The anti-p30 and anti-p72 antibody response of pigs inoculated with ASFV-GZΔI73R or ASFV-GZ. (G) Proinflammatory cytokines associated with TNF signaling pathway (IL-6 and TNF-α) in pigs inoculated with 103.0 TCID50 of ASFV-GZΔI73R or 104.0 TCID50 of ASFV-GZ, respectively. The heatmap was drawn using the median of each group. Each small square represents cytokine expression, and the depth of the color represents the level of expression. Means between the two groups were compared using two-tailed Student’s t tests; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (H) Representative data from pigs on different days after immunized with ASFV-GZΔI73R. (I) Mean percentages of CD3+CD4+CD8− T cells and CD3+CD4−CD8+ T cells in PBMCs of pigs immunized with ASFV-GZΔI73R. (J) Representative data from pigs on D 28 postinoculation followed by stimulation with ASFV-GZ for 60 h in vitro. (K) Mean proliferation percentages of PBMCs after stimulation with RPMI-1640 medium (control group) or ASFV-GZ.

Table 3.

The pathogenic scores of the infected tissues from the pigs inoculated with ASFV-GZΔI73R or GZ201801 virus or the Placebo control group

| Groups | Pig No. | Gross lesions of the tissues observed during necropsy. Severity & Scoring: Mild (1), Moderate (2), Severe (3) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tonsil | Kidney | Liver | Spleen | Lung | Thymus | LNs† | Gastrointestine | Joint | ||

| 103.0 TCID50 ASFV-GZΔI73R | L1 | * | * | * | * | * | Hyperemia (1) | Hyperemia, Swell (4) | * | * |

| L2 | * | * | * | * | * | * | Hyperemia, Swell (3) | * | * | |

| L3 | * | * | * | * | * | * | Hyperemia, Swell (4) | * | * | |

| L4 | * | * | * | * | * | * | Hyperemia, Swell (5) | * | * | |

| L5 | * | * | * | * | * | * | Hyperemia, Swell (4) | * | * | |

| 105.0 TCID50 ASFV-GZΔI73R | H1 | * | * | * | * | * | * | Hyperemia, Swell (4) | * | * |

| H2 | * | * | * | * | * | * | Hyperemia, Swell (5) | * | ||

| H3 | * | * | * | * | * | * | Hyperemia, Swell (4) | * | * | |

| H4 | * | * | * | * | * | * | Hyperemia, Swell (4) | * | * | |

| H5 | * | * | * | * | * | * | Hyperemia, Swell (5) | * | * | |

| 104.0 TCID50 ASFV-GZ (1) | W1-1 | Flush (1) | Hemorrhage (3) | Hyperemia (1) | Petechia (3) | Edema (1) | * | Hyperemia, Swell (17) | * | Swell (2) |

| W1-2 | Flush (1) | Hemorrhage (3) | Hyperemia (1) | Petechia (2) | Extravasated blood (2) | Petechia (3) | Hyperemia, Swell (25) | Cecum Hemorrhage (1) | / | |

| W1-3 | Flush (1) | Hemorrhage (3) | Hyperemia (2) | Hyperemia (1) | Edema (1) | Petechia (3) | Hyperemia, Swell (25) | * | * | |

| Placebo | N1 | * | * | * | * | * | * | Hyperemia, Swell (2) | * | * |

| N2 | * | * | * | * | * | * | Hyperemia, Swell (1) | * | * | |

| N3 | * | * | * | * | * | Hyperemia (1) | Hyperemia, Swell (3) | * | * | |

*No gross lesion observed.

†Eight kinds of LNs were included: lumbar LNs, submaxillary LNs, inguinal LNs, gastrohepatic LNs, hilar LNs, groin LNs, mediastinal LNs, and mesenteric LNs.

As shown in Fig. 6D, the ASFV-GZ-infected pigs exhibited high levels of viral DNA (107.85 to 108.97 copies/mL) at the time of death. However, none of the pigs in the ASFV-GZΔI73R-immunized and challenged pigs had higher viremia levels than those of the ASFV-GZ-infected pigs. The level of viral DNA gradually decreased by D 21 of challenge (<103.02 copies/mL). Additionally, viral DNA was not detected in the blood of the three sentinel pigs cohoused with the ASFV-GZΔI73R group during the 28 d of cohabitation. This indicated that the animals vaccinated with the ASFV-GZΔI73R strain did not exhibit viral shedding, or that the amount of shed virus was insufficient to cause new infections.

Furthermore, viremia in one-third of the pigs was eliminated after 21 d of challenge. These results indicated that replication of the ASFV-GZ was significantly reduced or eliminated in the pigs vaccinated with ASFV-GZΔI73R.

ASFV-GZΔI73R Induces the Production of the Proinflammatory Cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α In Vivo.

To evaluate the immune response of pigs to ASFV-GZΔI73R, the serum samples of experimental pigs were collected on D 3, 5, 7, 9, 14, 21, and 28 of vaccination to detect ASFV-induced anti-p72 antibodies and anti-p30 antibodies and IgG and IgM expression levels. Anti-p72 and anti-p30 antibodies were not at detectable levels in ASFV-GZ-infected pigs that subsequently died (Fig. 6 E and F). Anti-p72 antibodies were not detected in the serum of pigs vaccinated with ASFV-GZΔI73R. Only one of the three pigs (Pig R2) exhibited a low level of anti-p30 antibodies on D 14 of postvaccination, which slightly increased by D 28. In contrast, the levels of IgG antibodies increased gradually in all the surviving pigs after 4 to 5 dpi and were highest after 7 to 9 d before decreasing gradually (SI Appendix, Fig. S7A). IgM antibodies were detected 3 to 5 d postvaccination before peaking on approximately 14 to 21 d postvaccination and remaining stable until the end of the observation period (SI Appendix, Fig. S7B).

The temporal expression patterns of cytokines in the pigs vaccinated with the ASFV-GZΔI73R deletion mutant were evaluated and compared with the patterns in the pigs infected with the ASFV-GZ strain. The expression levels of IL-6 and TNF-α (associated with the TNF and NF-κB signaling pathways) in the sera of pigs of each group were detected via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay after vaccination. The results showed that pigs infected with ASFV-GZ exhibited low or negligible expression of cytokines (Fig. 6 G, Left). However, the levels of IL-6 and TNF-α in the sera of pigs inoculated with ASFV-GZΔI73R were significantly higher (Fig. 6 G, Right). These results indicated that ASFV-GZΔI73R induced the production of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α in vivo.

ASFV-GZΔI73R Activates Specific T Cell Response.

The activation of CD4+ T and CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) is a major phenotype of cell-mediated immune response. The effect of ASFV-GZΔI73R on the activation of CD4+ and CD8+ CTLs was examined. PBMCs were isolated from the whole blood of pigs immunized with ASFV-GZΔI73R on 0, 7, 14, and 28 dpi and then stained with CY5.5-conjugated anti-CD3e, phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD4, and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD8a antibodies. The T cell subsets in the PBMCs were analyzed via fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). As shown in Fig. 6 H and I, the percentages of CD3+CD4+CD8− cells (helper T cells) gradually increased after ASFV-GZΔI73R immunization with a significant increase on 7, and 14 dpi when compared with those before immunization (P < 0.05), followed by a significant decrease at 28 dpi. The percentages of CD3+CD4−CD8+ cells were not significantly affected after immunization.

Subsequently, an antigen-specific T cell proliferation assay was performed with the PBMCs isolated from pigs on 28 dpi and then infected (m.o.i = 0.001) with ASFV-GZ or with a placebo (cell culture medium RPMI-1640) for 60 h in vitro. These cultured cells were then stained with CY5.5-conjugated anti-CD3e, PE-conjugated anti-CD4, and FITC-conjugated anti-CD8a antibodies and subjected to FACS analysis. As shown in Fig. 6 J and K, in contrast to the placebo (RPMI-1640), ASFV-GZΔI73R effectively activated CD8+ CTL proliferation in vitro but did not significantly affect the proliferation of CD4+ T cells. This demonstrated that ASFV-GZΔI73R can activate specific T cell responses.

Safety Evaluation of ASFV-GZΔI73R in Pigs.

To further evaluate the biosafety of ASFV-GZΔI73R, vaccination with a very high inoculum was performed followed by an extended observation period. The behavior of pigs in separate groups of five pigs i.m. inoculated with ASFV-GZΔI73R (TCID50 = 106.0) was compared with that of pigs inoculated with sentinel (phosphate-buffered saline). The body temperature and other clinical symptoms of animals were monitored during the 56-d observation period. The relevant data are summarized in SI Appendix. As shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S8, all the pigs infected with the ASFV-GZΔI73R remained healthy and did not exhibit any ASF-related clinical signs. Additionally, no death occurred in this group during the 56-d observation period (SI Appendix, Fig. S8A). Similarly, all the mock-infected pigs remained clinically healthy. The rectal temperature of all the pigs was relatively stable within the range of 38.9 to 40.5 °C. The variation in the rectal temperature of each individual pigs is illustrated in SI Appendix, Fig. S8B. The viral DNA levels in each group was illustrated in SI Appendix, Fig. S8C. In pigs inoculated with ASFV-GZΔI73R, viral DNA was detected from 7 to 9 dpi (103.4 to 104.85 copies/mL). The viral DNA levels peaked at 14 dpi (104.55 to 105.25 copies/mL) and significantly decreased at 21 dpi (103.2 to 104.2 copies/mL). Viremia was cleared at approximately 4 to 5 wk after inoculation. Viral infection did not relapse at the end of the 56-d observation period. Additionally, no viral DNA was detected in any tissue samples, indicating that the high inoculum of the ASFV-GZΔI73R strain was completely cleared during the 56-d observation period (SI Appendix, Fig. S8D). These results suggest that the ASFV-GZΔI73R strain was reasonably safe to immunize pigs.

ASFV-GZΔI73R Exhibits Good Genetic Stability In Vitro.

To investigate the genetic stability of ASFV-GZΔI73R, the full-length genome of ASFV-GZΔI73R was sequenced using nanopore sequencing after consecutive passes on BMDMs for 15 passages. The results showed that the ASFV-GZΔI73R-P15 genome did not exhibit genomic insertion, deletion and/or a significant gene mutation. Next, coinfection of the ASFV-GZΔI73R and the ASFV-GZmI73R-HA viruses was performed in vitro to assess for a potential recombination. The ASFV-GZΔI73R virus was mixed with the ASFV-GZmI73R-HA in equal volumes (105.0 TCID50/mL), and then the viral mix was used to infect primary BMDMs at an m.o.i of 0.01. At 72 hpi, the virus culture was harvested for four more passages in primary BMDMs with an inoculum size of 2 % (v/v). Then, a pair of primers specific to the flanking region of the I73R was designed. Two specific bands were detected upon PCR (SI Appendix, Fig. S9A). These PCR amplicons were cloned into the pCR™-Blunt vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and introduced into Escherichia coli, and 30 colonies were sequenced via Sanger sequencing. Of them, 18 colonies mapped to the p72-EGFP cassette (972 bp) originating from the ASFV-GZΔI73R strain, and the other 12 mapped to the I73R-HA-P72-mCherry cassette (1,212 bp) belonging to the ASFV-GZmI73R-HA strain. No other recombination events were detected (SI Appendix, Fig. S9B). Taken together, these results indicated that the ASFV-GZΔI73R exhibits good genetic stability in vitro.

Discussion

Commercial vaccines against ASFV are currently unavailable, which limits the control of ASF worldwide. Several vaccine strategies, such as inactive, subunit, DNA and vector vaccines, have been attempted. However, their efficacy of these vaccines is insufficient because they do not stimulate the desired immune-protective effect in swine (27–29). Recent studies have demonstrated that several natural isolates and recombinant viruses with deletions of various virulence-related genes can induce a robust, protective effect (17, 18, 30). Although, live-attenuated vaccines have shown potential for inducing a strong immune-protective responses to virulent ASFV challenges when compared with other types of vaccines. However, the safety of live-attenuated vaccines is a major concern. For example, recent studies have suggested that the live-attenuated virus cannot be completely eliminated and can either induce chronic diseases or side effects such as skin ulcers, persistent fever, viremia, and joint swelling (31–33). Additionally, viral shedding and circulation in pigs may also pose potential threats of virulence relapse. To facilitate improvement in ASFV vaccine master seed strains, the molecular functions of proteins that are potential virulence-related attenuation targets must be elucidated.

This study identified I73R, a virulence-related gene that is highly conserved, functionally stable, and important for ASFV infection and pathogenicity. The expression pattern of the I73R gene during viral replication was similar to that of ASFV p30. In particular, the expression of I73R was up-regulated in the early stage (Fig. 1C), which is consistent with the results of previous studies (34, 35). However, whether ASFV pI73R plays important roles in the regulation of the host intracellular environment, antagonization of host innate immunity, or in facilitating virus replication, spread, or proliferation has not been investigated until now. The results of Rluc assay, qRT-PCR, and ribopuromycylation revealed that pI73R significantly inhibited host cellular protein synthesis (Fig. 2 A–C and H).

To examine the mechanisms underlying the pI73R-mediated inhibition of host protein synthesis, pI73R was crystallized in the H32 space group. The monomer comprised a winged helix-turn-helix domain with two antiparallel β-strands and three α-helices (Fig. 3A), which are typical characteristics of the Zα domain. pI73R has indeed been reported to have strong nucleic acid-binding activity (36), we found that pI73R preferentially binds ssRNA. More interestingly, we deduced a class of consensus pI73R-binding motif from RIP-Seq data, and confirmed that pI73R preferentially binds to high-GC content of host mRNAs. For comparison, the A + T nucleotides in ASFV genome is as high as 62% (A–30%, T–32%), while the G+C content is only 38% (G–19%, C–19%) (37). This property of pI73R to preferentially bind to high-GC content of ssRNA may explain why pI73R binds predominantly to host mRNAs rather than the ASFV mRNAs of low GC content.

Related studies have reported that nucleic-acid-binding proteins, particularly RNA-binding proteins, are involved in multiple biological activities, such as RNA metabolism, pre-mRNA splicing, RNA stability, and mRNA translation. Several viruses are reported to encode such proteins (38–40). During the viral infection process, infected cells reprogram the gene expression pattern to establish a satisfactory antiviral defense. However, viruses have evolved various strategies to alter RNA metabolism and inhibit protein synthesis in host cells and consequently facilitate viral protein synthesis and replication. For example, adenovirus, vesicular stomatitis virus, and influenza virus can inhibit gene expression in host cells by modifying mRNA nuclear export. The NSP1 protein of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus suppresses host gene expression by promoting host mRNA degradation and inhibiting host translation in infected cells (41, 42). However, the mechanism underlying the regulation and translation of mRNAs by ASFV in infected cells remains unclear. It has been shown that pDP71L recruits PP1 to dephosphorylate the translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) and prevents the inhibition of global protein synthesis in host cells (43). Additionally, ASFV pE66L can interact with PKR to trigger PKR/eIF2α phosphorylation and induce translational arrest (25). Therefore, we speculated that the strong binding affinity of ASFV-encoded pI73R to host mRNA might be a viral defense strategy to alter cellular RNA metabolism by broadly inhibiting the host antiviral protein synthesis.

In this study, a cytokine-encoding gene with high GC content (TNF-α) was selected as the target to elucidate the molecular mechanism underlying the pI73R-mediated regulation of host protein synthesis. The results of the RIP assay, MS2/MS2 coat protein (MCP) reporter system, and RNA-ISH assay revealed that pI73R could bind to the endogenous TNF-α mRNA and promote its nuclear retention (Fig. 4 G–I). These results were consistent with those of RNA-Seq analysis, which revealed significant inhibitory effects of exogenous pI73R on TNF-α-mediated transcriptional activation of downstream genes in HEK-293T cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S5).

To examine the roles of I73R in the pathogenicity of ASFV in vivo, a I73R deletion mutant of the ASFV-GZ strain was constructed. Subsequently, pigs were inoculated with the mutant and parental strains subjected to challenge experiments. I73R deletion completely attenuated the highly virulent ASFV-GZ strain and elicited robust immune responses in pigs. First, all pigs inoculated with ASFV-GZΔI73R survived irrespective of the inoculum size. Second, the surviving pigs had remarkably lower viremia levels, and their death was delayed by 5 to 7 d relative to pigs infected with the parental ASFV-GZ strain, all of which died on D 9. Third, activation of the immune defense ability of T cells in pigs inoculated with ASFV-GZΔI73R was observed from 7 dpi, and significantly increased at 7 to 14 dpi. Fourth, the I73R gene-deleted strain was completely cleared from the pigs within 28 d of vaccination. This markedly decreases the risk of homologous recombination between of ASFV-GZΔI73R and wild-type viruses in a clinical setting. Fifth, oral and anal swab analyses revealed that pigs inoculated with ASFV-GZΔI73R exhibited minimal viral shedding. Sentinel pigs did not develop viremia during the 28-d observation period. These results indicate that the ASFV-GZΔI73R strain exhibited a weak ability to cause horizontal transmission. Sixth, the pigs inoculated with ASFV-GZΔI73R did not exhibit pathogenic or histopathological changes in major organs, such as the tonsil, thymus, kidney, spleen, lung, liver, inguinal LNs, or mesenteric LNs. Finally, and most importantly, all pigs were completely protected when challenged with the virulent parental ASFV-GZ strain at a lethal dose. These results suggest that the ASFV-GZΔI73R strain is a highly effective ASF vaccine candidate with high efficacy to induce protection even when low inoculum levels are used.

The molecular mechanisms involved in immune responses against ASFV have not been elucidated. Additionally, the correlation between virus-specific antibodies in the serum and immune protection is controversial. In this study, low levels of anti-p30 antibodies were detected in one-third of pigs inoculated with ASFV-GZΔI73R, whereas anti-p72 antibodies were not detected. The remaining pigs tested negative for the presence of anti-p30 or anti-p72 antibodies. Therefore, a good association was not observed between protection and virus-specific antibodies in serum. However, high levels of IgG and IgM antibodies were detected in all the animals vaccinated with ASFV-GZΔI73R. Furthermore, in contrast to the ASFV-GZ strain, the ASFV-GZΔI73R strain significantly induced the expression of cytokines related to the TNF and NF-κB signaling pathways, including IL-6 and TNF-α. These results suggest that I73R suppresses the interferon-mediated inhibition of virus infection. This is consistent with the pI73R overexpression-induced inhibition of TNF-α–mediated transcriptional activation of downstream genes in vitro.

In conclusion, I73R of ASFV was demonstrated to be a virulence factor. I73R deletion can completely block residual pathogenicity of ASFV-GZ strain in swine. Additionally, ASFV-GZΔI73R can be completely cleared from the pigs without horizontal transmission, which is crucial for biosafety. We suggest that ASFV-GZΔI73R can be used as a live-attenuated candidate vaccine.

Materials and Methods

Biosafety statement, virus and cells, virus infection and RNA-Seq, plasmid construction, in vitro transcription, protein expression, crystallization, data collection, and structural characterization, X-ray diffraction data collection and structure determination, transfection and qRT-PCR verification, reporter assay and ribopuromycylation assay, CHX chase assay, EMSA, BLI assay, homologous recombination, RIP-Seq, MS2/MCP system, ISH, IFA, animal trials, indirect ELISA, measuring specific T-cell response, and statistical analysis are described in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We especially thank Mr. Chongyu Zhang, Ms. Jing Zhang and Prof. Guihong Zhang for their kind assistance. We acknowledge Shanghai Baichuangyi Biotechnology Co., Ltd for their involvement in the Oxford Nanopore Technologies (Oxford, UK) experimental work and bioinformatics analysis. Funding: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32170161, U19A2039, U20A2059 and 32102652), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No 2021YFD1801401, 2021YFD1801300 and 2021YFD1800104), the Shanghai Sailing Program (23YF1457400), the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (CAAS-ZDRW202203), and the Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (Y2022PT11).

Author contributions

Y. Liu, Z.S., H.W., G.P., and H.C. designed research; Y. Liu, Z.S., Y.S., Y. Li, R.L., L.G., D.D., Jianqi Liu, Jingyi Liu, Z.C., W.Y., L.L., Q.Z., X.L., C.T., R.W., and Q.S. performed research; Z.X., Y.S., Y. Li, Jianqi Liu, and Q.S. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; Y. Liu, R.L., D.D., Jianqi Liu, Z.C., W.Y., L.L., Q.Z., X.L., C.T., R.W., H.W., and G.P. analyzed data; and Y. Liu and Z.S. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Contributor Information

Heng Wang, Email: wangheng2009@scau.edu.cn.

Guiqing Peng, Email: penggq@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Hongjun Chen, Email: vetchj@shvri.ac.cn.

Data, Material, and Software Availability

All data are available in the main text or SI Appendix. The transcriptional profiles of the ASFV genome reported in this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (SRA) (Accession no. PRJNA781905) (44). RNA-Seq datasets of HEK-293T cells can be retrieved from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus database (Accession no. GSE189293) (45). Next-generation sequencing datasets generated in the RIP assay have been deposited in the NCBI SRA (Accession no. PRJNA826687) (46). Nanopore raw sequencing data (FAST5 and FASTQ format) have been uploaded to the NCBI SRA (Accession no. PRJNA899338) (47).

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Gaudreault N. N., Madden D. W., Wilson W. C., Trujillo J. D., Richt J. A., African Swine fever virus: An emerging DNA arbovirus. Front. Vet. Sci. 7, 1–17 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galindo I., Alonso C., African swine fever virus: A review. Viruses 9, 1255 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alonso C., et al. , ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Asfarviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 99, 613–614 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou X., et al. , Emergence of African Swine fever in China, 2018. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 65, 1482–1484 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tao D., et al. , One year of African swine fever outbreak in China. Acta Trop. 211, 105602 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ankhanbaatar U., et al. , African swine fever virus genotype II in Mongolia, 2019. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 68, 2787–2794 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim H. J., et al. , Outbreak of African swine fever in South Korea, 2019. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 67, 473–475 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le V. P., et al. , Outbreak of African Swine Fever, Vietnam, 2019. Emerg Infect Dis. 25, 2017–2019 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mighell E., Ward M. P., African Swine fever spread across Asia, 2018–2019. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 68, 2722–2732 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dixon L. K., Chapman D. A. G., Netherton C. L., Upton C., African swine fever virus replication and genomics. Virus Res. 173, 3–14 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salas M. L., Rey-Campos J., Almendral J. M., Talavera A., Viñuela E., Transcription and translation maps of African swine fever virus. Virology 152, 228–240 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yáñez R. J., et al. , Analysis of the complete nucleotide sequence of African Swine fever virus. Virology 208, 249–278 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodríguez J. M., Salas M. L., Viñuela E., Intermediate class of mRNAs in African swine fever virus. J. Virol. 70, 8584–8589 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vin E., Salas A. L., De Biologı C., African Swine fever virus dUTPase is a highly specific enzyme required for efficient replication in swine macrophages. J. Virol. 73, 8934–8943 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goatley L. C., et al. , Nuclear and nucleolar localization of an African swine fever virus protein, I14L, that is similar to the herpes simplex virus- encoded virulence factor ICP34.5. J. Gen Virol. 80, 525–535 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallardo C., et al. , African swine fever virus (ASFV) protection mediated by NH/P68 and NH/P68 recombinant live-attenuated viruses. Vaccine 36, 2694–2704 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Donnell V., et al. , Simultaneous deletion of the 9GL and UK genes from the African Swine fever virus Georgia 2007 isolate offers increased safety and protection against homologous challenge. J. Virol. 91, 1–18 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borca M. V., et al. , Development of a highly effective African Swine fever virus vaccine by deletion of the I177L gene results in sterile immunity against the current epidemic Eurasia strain. J. Virol. 94, 1–15 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gladue D. P., et al. , Deletion of the A137R Gene from the pandemic strain of African Swine fever virus attenuates the strain and offers protection against the virulent pandemic virus. J. Virol. 95, e0113921 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y., et al. , African Swine fever virus bearing an I226R gene deletion elicits robust immunity in pigs to African Swine fever. J. Virol. 95, e01199-21 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramírez-Medina E., et al. , The MGF360-16R ORF of African swine fever virus strain Georgia encodes for a nonessential gene that interacts with host proteins SERTAD3 and SDCBP. Viruses 12, 60 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Hoewyk D., Use of the non–radioactive SUnSET method to detect decreased protein synthesis in proteasome inhibited Arabidopsis roots. Plant Methods 12, 1–7 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y., et al. , Development and in vivo evaluation of MGF100-1R deletion mutant in an African swine fever virus Chinese strain. Vet Microbiol. 261, 109–208 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castelló A., et al. , Regulation of host translational machinery by African swine fever virus. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000562 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen Z., et al. , Novel function of African Swine fever virus pE66L in inhibition of host translation by the PKR/eIF2α pathway. J. Virol. 95, 1–18 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galindo-Cardiel I., et al. , Standardization of pathological investigations in the framework of experimental ASFV infections. Virus Res. 173, 180–190 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruiz-Gonzalvo F., Rodríguez F., Escribano J. M., Functional and immunological properties of the baculovirus-expressed hemagglutinin of African swine fever virus. Virology 218, 285–289 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Argilaguet J. M., et al. , DNA vaccination partially protects against African Swine fever virus lethal challenge in the absence of antibodies. PLoS One 7, 1–11 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blome S., Gabriel C., Beer M., Modern adjuvants do not enhance the efficacy of an inactivated African swine fever virus vaccine preparation. Vaccine 32, 3879–3882 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Donnell V., et al. , African Swine Fever Virus Georgia isolate harboring deletions of MGF360 and MGF505 genes is attenuated in swine and confers protection against challenge with virulent parental virus. J. Virol. 89, 6048–6056 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leitão A., et al. , The non-haemadsorbing African swine fever virus isolate ASFV/NH/P68 provides a model for defining the protective anti-virus immune response. J. Gen. Virol. 82, 513–523 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.King K., et al. , Protection of European domestic pigs from virulent African isolates of African swine fever virus by experimental immunisation. Vaccine 29, 4593–4600 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sang H., Miller G., Lokhandwala S., Sangewar N., Progress toward development of effective and safe African Swine fever virus vaccines. Front. Vet. Sci. 7, 1–9 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alcamí A., Carrascosa A. L., Viñuela E., Interaction of African swine fever virus with macrophages. Virus Res. 17, 93–104 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodríguez J. M., Salas M. L., African swine fever virus transcription. Virus Res. 173, 15–28 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun L., et al. , Structural insight into African swine fever virus I73R protein reveals it as a Z-DNA binding protein. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 69, 1923–1935 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yáñez R. J., et al. , Analysis of the complete nucleotide sequence of African swine fever virus. Virology 208, 249–278 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stohlman S. A., et al. , Specific interaction between coronavirus leader RNA and nucleocapsid protein. J. Virol. 62, 4288–4295 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nelson G. W., Stohlman S. A., Tahara S. M., High affinity interaction between nucleocapsid protein and leader/intergenic sequence of mouse hepatitis virus RNA. J. Gen. Virol. 81, 181–188 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robbins S. G., Frana M. F., McGowan J. J., Boyle J. F., Holmest K. V., RNA-binding proteins of coronavirus MHV: Detection of monomeric and multimeric N protein with an RNA overlay-protein blot assay. Virology 150, 402–410 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hernaez B., Alonso C., Dynamin- and clathrin-dependent endocytosis in African Swine fever virus entry. J. Virol. 84, 2100–2109 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sánchez E. G., et al. , African swine fever virus uses macropinocytosis to enter host cells. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002754 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang F., Moon A., Childs K., Goodbourn S., Dixon L. K., The African Swine fever virus DP71L protein recruits the protein phosphatase 1 catalytic subunit to dephosphorylate eIF2α and inhibits CHOP induction but is dispensable for these activities during virus infection. J. Virol. 84, 10681–10689 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Y., et al. , Sus scrofa domesticus Raw sequence reads. Sequence Read Archive. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA781905. Deposited 19 Nov 2021.

- 45.Shen Z., et al. , ASFV I73R acts on HEK-293T. Gene Expression Omnibus database. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE189293. Deposited 22 Nov 2021.

- 46.Liu Y., et al. , Next-generation sequencing datasets generated in the RIP assay. Sequence Read Archive. https://submit.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/subs/bioproject/SUB11336119/overview. Deposited 21 Nov 2022.

- 47.Liu Y., et al. , Nanopore raw sequencing data of ASFV-GZ and ASFV-GZΔI73R. Sequence Read Archive. https://submit.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/subs/bioproject/SUB12266641/overview. Deposited 21 Nov 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text or SI Appendix. The transcriptional profiles of the ASFV genome reported in this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (SRA) (Accession no. PRJNA781905) (44). RNA-Seq datasets of HEK-293T cells can be retrieved from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus database (Accession no. GSE189293) (45). Next-generation sequencing datasets generated in the RIP assay have been deposited in the NCBI SRA (Accession no. PRJNA826687) (46). Nanopore raw sequencing data (FAST5 and FASTQ format) have been uploaded to the NCBI SRA (Accession no. PRJNA899338) (47).