Significance

The E2F transcription factor regulates the expression of a large panel of genes, but some of these remain largely unexplored. Our current knowledge on how E2F regulates gene expression is based on in vitro assays, such as luciferase reporters, electrophoretic mobility shift assay, and chromatin immunoprecipitation assay. The limitation of these approaches is that they may not reflect how E2F regulates gene expression in vivo, in a particular tissue and developmental context. Here, the CRISPR/Cas9 technology allowed us to examine the relevance of E2F regulation of the endogenous E2F targets. This approach could also be applied to study the function of other transcription factors showing pleiotropic phenotypes.

Keywords: E2F transcription factor, Drosophila, metabolism, Retinoblastoma protein, Phosphoglycerate kinase (Pgk)

Abstract

The canonical role of the transcription factor E2F is to control the expression of cell cycle genes by binding to the E2F sites in their promoters. However, the list of putative E2F target genes is extensive and includes many metabolic genes, yet the significance of E2F in controlling the expression of these genes remains largely unknown. Here, we used the CRISPR/Cas9 technology to introduce point mutations in the E2F sites upstream of five endogenous metabolic genes in Drosophila melanogaster. We found that the impact of these mutations on both the recruitment of E2F and the expression of the target genes varied, with the glycolytic gene, Phosphoglycerate kinase (Pgk), being mostly affected. The loss of E2F regulation on the Pgk gene led to a decrease in glycolytic flux, tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates levels, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) content, and an abnormal mitochondrial morphology. Remarkably, chromatin accessibility was significantly reduced at multiple genomic regions in PgkΔE2F mutants. These regions contained hundreds of genes, including metabolic genes that were downregulated in PgkΔE2F mutants. Moreover, PgkΔE2F animals had shortened life span and exhibited defects in high-energy consuming organs, such as ovaries and muscles. Collectively, our results illustrate how the pleiotropic effects on metabolism, gene expression, and development in the PgkΔE2F animals underscore the importance of E2F regulation on a single E2F target, Pgk.

The E2F transcription factor is a heterodimeric complex between E2F and DP subunits, which has been initially characterized by its binding to a short 8 bp degenerative sequence in the adenovirus E2 promoter. These, so-called E2F-binding sites, are also present in the promoters of many cell cycle genes and mediate their transcriptional activation in a cell cycle–dependent manner. The activity of the E2F transcription factor is negatively regulated by the Retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein (pRB). The pRB binds to E2F and masks its transactivation domain. The inhibition of E2F by pRB is released in late G1, as cyclin-dependent kinases phosphorylate pRB, thus dissociating E2F–pRB complexes and releasing free E2F that activates the transcriptional program for G1-S transition and drives the entry to S phase (1–5).

The model of how pRB regulates E2F-dependent transcription served as a framework for follow-up studies that revealed a much more complex picture. Unexpectedly, the list of E2F target genes extends far beyond cell cycle genes (6–12). Among the E2F targets are genes involved in differentiation programs, metabolism, mitochondrial function, apoptosis, and others. Many of these transcriptional programs appear to be cell-type–specific illustrating that E2F may have unique functions in different contexts (13, 14). Collectively, these observations support the idea that E2F-dependent transcription is a key aspect of E2F function and, thus, highlight the significance of E2F sites that mediate the recruitment of E2F to its target genes.

Given that E2F regulates thousands of genes, one of the important questions is how many among them are the key effector genes. Is the function of E2F the net result of E2F controlling hundreds of genes with either many of them being important or only a few being rate-limiting? Earlier studies in both flies and mammals showed that the overexpression of cyclin E can rescue defects in S phase entry in E2F-deficient cells (15, 16), thus, leading to the idea that cyclin E is the key downstream target of E2F. The other key target is thought to be string, encoding Cdc25, which can drive E2F mutant cells through G2/M transition (17). One limitation of these experiments is that genes are overexpressed at nonphysiologically high levels and that the rescue is incomplete as cells are unable to sustain normal proliferation. Later genetic experiments demonstrated that the list of key cell cycle targets is likely to be much larger, as haploinsufficiency for half of E2F-target genes modified the E2F-dependent phenotype (18). Although these experiments provided a glimpse at the potential rate-limiting E2F targets, they did not address the functional importance of E2F binding sites in their promoters. Another complexity arises from E2F participating in multiple tissue-specific transcriptional programs. Thus, the relative importance of E2F targets likely varies between different cell types, and therefore, this question cannot be easily addressed in cell lines.

Model systems, such as Drosophila, which has a streamlined and highly conserved version of the Rb pathway, are advantageous in exploring context dependency of E2F-dependent transcription during animal development (19). In flies, there are two E2F genes, E2f1 and E2f2, a single Dp gene, and an Rb ortholog, Rbf. Since Dp is required for both E2Fs to bind to DNA, inactivation of Dp either by RNA interference (RNAi) or by genetic mutations has been often used to explore the consequence of the loss of E2F regulation (20, 21). Surprisingly, Dp-deficient animals develop relatively normally until late pupal stages when the lethality occurs due to defects in metabolic tissues, such as muscle and fat body (22, 23). A common feature in both Dp-deficient tissues is a change in carbohydrate metabolism, which, at least partially, accounts for animal lethality (24). Integrative analysis of proteomic, transcriptomic, and chromatin immunoprecipitation assay with sequencing (ChIP-seq) data suggest that E2F/Dp/Rbf directly activates the expression of glycolytic and mitochondrial genes during muscle development (12). Given the importance of this transcriptional program, and that many of these metabolic genes contain E2F binding sites, we aimed to study how these genes are regulated by E2F.

Using CRISPR/Cas9 technology in Drosophila, we systematically edited putative E2F binding sites in five metabolic genes. We determined the impact of these mutations on the recruitment of E2F/Dp/Rbf to the regulatory regions of these genes, the expression of the target genes, and the impact on fly physiology. Collectively, our data illustrate that E2F-dependent regulation is a complex combination of both direct and indirect effects.

Results

E2F Binding Sites Contribute to the Transcriptional Activation of Metabolic Genes in Reporter Assays In Vitro.

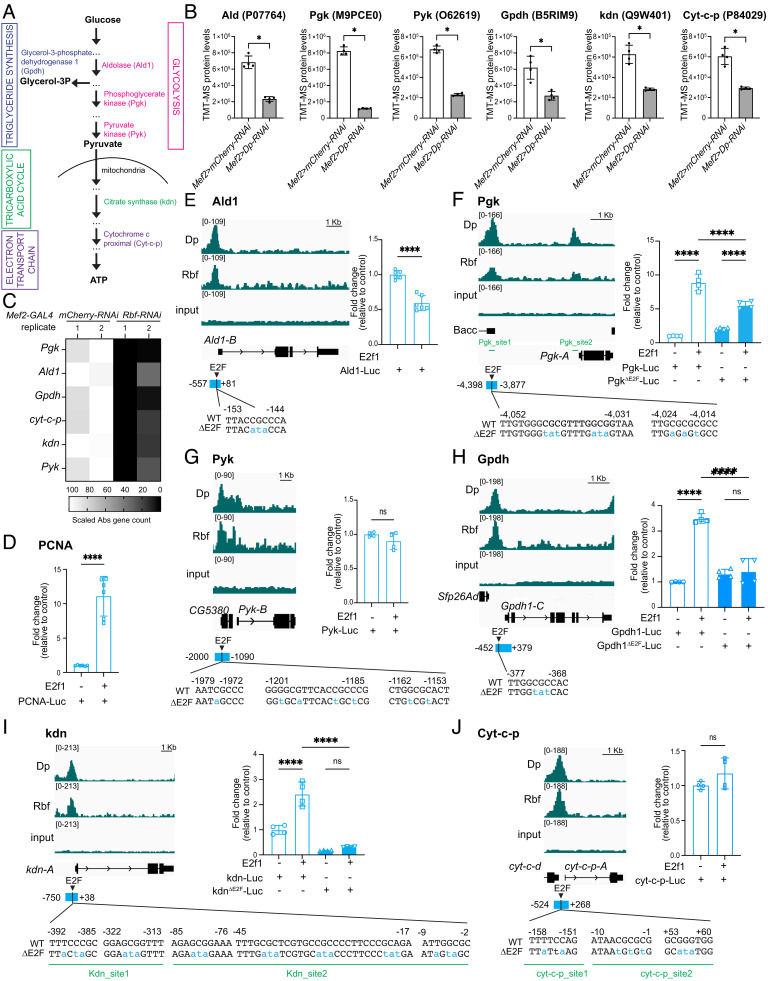

E2F/Dp has an essential role in adult skeletal muscle (23). Unlike its canonical role in the regulation of the cell cycle genes, E2F/Dp together with Rbf directly activates the expression of metabolic genes during the late stages of muscle development (12). To understand the mechanisms by which E2F regulates this process, we examined the function of the cis-regulating elements located on the vicinity of E2F-target genes that mediate the recruitment of E2F/Dp/Rbf. We took advantage of available proteomic and transcriptomic profiles for Dp- and Rbf-deficient muscles (24), respectively, as well as muscle-specific ChIP-seq for both Dp and Rbf (12). Since the loss of Dp results in severe changes in carbohydrate metabolism, we first focused on analyzing genes encoding for proteins involved in glucose metabolism (Fig. 1A), in which the protein levels were reduced in Dp-depleted muscles (Fig. 1B, ref. 24). Then, from this list, we selected genes that were downregulated upon Rbf-depletion using the RNA-seq dataset for Rbf-deficient muscles and defined a set of genes in which both Dp and Rbf are needed for their transcriptional activation (Fig. 1C, ref. 12). Finally, we mined ChIP-seq for Dp and Rbf to identify genes with closely matching summits of both Dp and Rbf peaks in the vicinity of their transcription start sites [TSS, (12)]. Using these three stringent criteria, we selected three glycolytic genes, Aldolase 1 (Ald1), Phosphoglycerate kinase (Pgk), and Pyruvate kinase (Pyk), and one gene linking glycolysis to triglyceride synthesis, Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 (Gpdh) (Fig. 1A). To broaden the list of candidates, we also included the citrate synthase, knockdown (kdn), of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and Cytochrome c proximal (Cyt-c-p) of the electron transport chain in our analysis (Fig. 1A). In sum, all selected genes encoding for metabolic enzymes are strongly downregulated in both Dp- and Rbf- depleted muscles and have closely matching Dp and Rbf peaks in the vicinity of their TSSs (Fig. 1 E–J), thus implying that E2F could be directly activating the expression of these genes.

Fig. 1.

E2F target genes involved in metabolism. (A) Simplified illustration of the enzymes Ald1, Pgk, and Pyk in the glycolytic pathway, Gpdh connecting triglyceride synthesis with glycolysis, kdn in the TCA cycle, and Cyt-c-p in the electron transport chain. (B) Protein levels quantified by TMT-MS in flight muscles of Mef2>mCherry-RNAi and Mef2>Dp-RNAi, scatter dot plots with bars, mean ± SD, Mann–Whitney U test, *P < 0.05, n = 4. (C) Heatmap depicting selected transcripts levels measured by RNAseq in Mef2>mCherry-RNAi and Mef2>Rbf-RNAi. Abs count normalized and scaled, n = 2 samples/genotype. (D–J) Left panel: ChIPseq for Rbf, Dp, and input visualized with Integrative Genomics Viewer browser for the genomic regions surrounding the genes. The most predominantly expressed transcript in adult flies, based on the FlyAtlas 2 profile (25), is displayed; n = 2 samples/condition. Read scales and genomic scales included on top left and top right, respectively. GroupAuto scale. Right panel: Dual luciferase reporter assay in S2R+ cells for (D) PCNA-Luc, (E) Ald1-Luc, (F) Pgk-Luc, (G) Pyk-Luc, (H) Gpdh-Luc, (I) kdn-Luc, and (J) Cyt-c-p-Luc. Values for Firefly Luciferase luminescence normalized to Renilla luminescence. Fold change relative to control (no E2f1 expression). Mutated E2F sites are indicated as ΔE2F. Scatter dot plots with bars, mean ± SD, (F, H, and I) One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, (D, E, G, and J) Unpaired t test, ns P > 0.05, ****P < 0.0001, n = 2 replicates/group, N = 2 independent experiments. Bottom panel: E2F binding sites identified using degenerated motif WKNSCGCSMM. Mutations on the core are indicated in blue as ΔE2F. Blue rectangles indicate regions amplified and cloned upstream luciferase reporter. Positions are relative to transcription start site (TSS). Green bars indicate different sites amplified by ChIP-qPCR in Fig. 2 C–F and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A. Full genotypes: (B) w-;Mef2-GAL4/UAS-mCherry-RNAi (white bar) and w-;UAS-Dp-RNAi;Mef2-GAL4 (gray bar) (C) w-, UAS-Dicer2;+;Mef2-GAL4/UAS-mCherry-RNAi, and w-, UAS-Dicer2;+;Mef2-GAL4/UAS-Rbf-RNAi

Next, we analyzed the sequences encompassing the Dp and Rbf summits to identify putative E2F sites. We used the degenerative motif WKNSCGCSMM that was previously identified by de novo discovery motif as an E2F site in the flight muscles (12). For each gene, a single or multiple predicted E2F sites were found (Fig. 1 E–J). As an initial test, we generated six luciferase constructs containing the corresponding genomic regions for each gene (visualized as a blue rectangle) and tested the ability of a sole Drosophila E2F activator, E2f1, to activate these reporters in S2R+ cells in transient transfection assays. As expected, the transfection of the E2f1 expression plasmid led to a 10-fold activation of the PCNA-luc reporter, a well-known E2F reporter (Fig. 1D) (26). The generated luciferase constructs responded differently to the same amount of transfected E2f1. Pgk-luc, Gpdh-luc, and kdn-luc, were activated 3- to 10-fold by E2f1 and largely matched the activity of the PCNA-luc reporter (Fig. 1 D, F, H, and I). To determine whether E2f1-dependent activation is mediated through E2F binding sites, point mutations in the core of the E2F motif for each predicted E2F site were introduced (blue labels, Fig. 1 F, H, and I). The GpdhΔE2F-Luc and kdnΔE2F-Luc reporters no longer responded to E2f1 (Fig. 1 H and I). Mutating E2F binding sites in the PgkΔE2F-luc significantly reduced but did not completely abrogate the ability of E2f1 to activate the reporter (Fig. 1F). Unlike Pgk-luc, Gpdh-luc, and kdn-luc, the luciferase reporters for Ald1, Pyk, and Cyt-c-p failed to be activated by E2f1 (Fig. 1 E, G, and J). Overall, these data indicate that E2F regulates the transcription of several metabolic genes, including Gpdh, Pgk, and kdn, in vitro.

The E2F Binding Sites Recruit the Transcriptional Complex E2F/Dp/Rbf for Full Activation of Gene Expression In Vivo.

To understand the role of the newly identified E2F binding sites in the regulation of the endogenous metabolic genes in vivo, we introduced precise point mutations in the core elements of E2F motifs via genome editing using CRISPR/Cas-9-catalyzed homology-directed repair. We generated flies carrying such mutant alleles. For Pgk, Gpdh, and kdn, the point substitutions are identical to the mutated sequences of the luciferase reporters PgkΔE2F-Luc, GpdhΔE2F-Luc, and kdnΔE2F-Luc (Fig. 1 F, H, and I). For the exception of Pyk, we successfully generated GpdhΔE2F, PgkΔE2F, kdnΔE2F, Ald1ΔE2F, and Cyt-c-pΔE2F mutant alleles. The mutations in E2F sites labeled in blue (Fig. 1 E–J) were confirmed by sequencing. In order to eliminate off-target effects of CRISPR/Cas-9 gene editing, all ΔE2F site-edited lines were backcrossed en masse to the wild-type strain w1118 for six consecutive generations and at least two independent lines for each allele were established. The GpdhΔE2F, PgkΔE2F, kdnΔE2F, Ald1ΔE2F, and Cyt-c-pΔE2F alleles were homozygous viable.

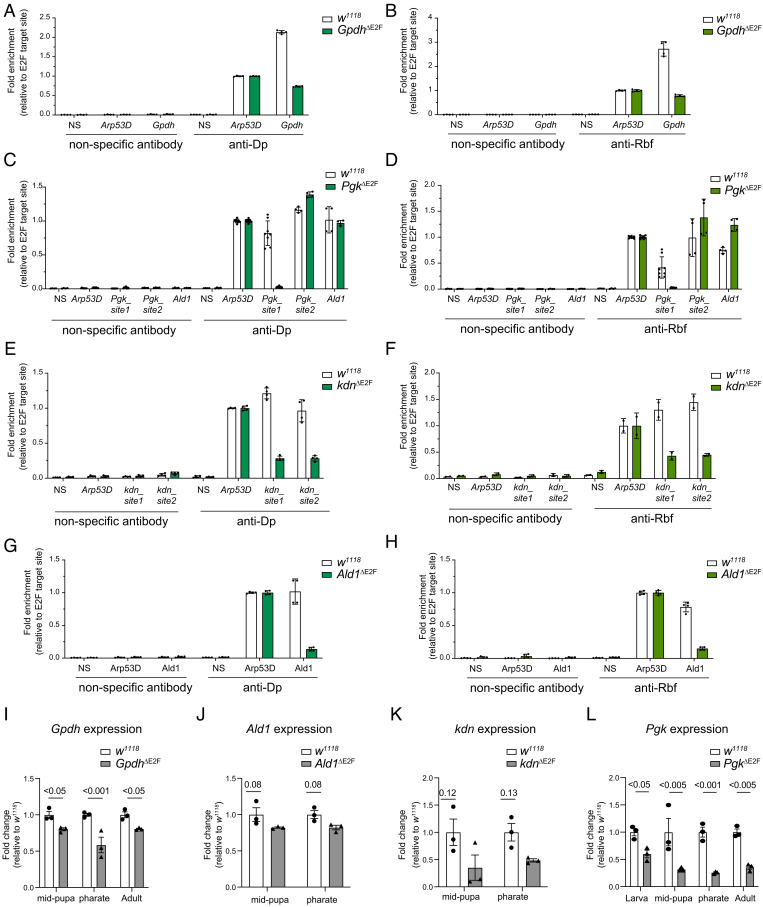

To determine the effect on the recruitment of E2F/Dp/Rbf in response to mutating E2F sites, we performed ChIP-qPCR using anti-Dp and anti-Rbf antibodies and nonspecific antibodies. A known E2F target gene, Arp53D, was used as a positive internal control to assess the level of Dp and Rbf enrichment in each chromatin immunoprecipitation (Fig. 2 A–H and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). Chromatin was prepared from third instar larva of the wild type, w1118, along with GpdhΔE2F, PgkΔE2F, kdnΔE2F, Ald1ΔE2F, and Cyt-c-pΔE2F homozygous mutant animals. Remarkably, with the exception of Cyt-c-pΔE2F, the recruitments of both Dp and Rbf were severely reduced when E2F sites were mutated (Fig. 2 A–H and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). We noticed that the extent of reduction in the occupancies of Dp and Rbf varied among the mutant alleles. For example, there was a 3-to-4-fold reduction in Dp and Rbf recruitment to the GpdhΔE2F and kdnΔE2F alleles while mutating E2F sites in Ald and Pgk resulted in much stronger effects. Remarkably, the binding of Dp and Rbf was completely lost in PgkΔE2F as the enrichments for Dp and Rbf at Pgk_site1 were indistinguishable from that of the negative control site (NS) (Fig. 2 C and D). Notably, the binding to Pgk_site2, another E2F target site in the vicinity of Pgk-A TSS that is about 4 kb downstream from where mutations were introduced (Fig. 1F), and the binding to Ald1, an E2F target site for another glycolytic gene, were not affected (Fig. 2 C and D). Thus, our data suggest that the engineered mutations prevent the recruitment of E2F/Dp/Rbf in a highly specific manner.

Fig. 2.

The requirement of the E2F binding sites for the recruitment of E2F/Dp/Rbf and gene expression regulation in vivo. (A–H) Chromatin from third instar larvae immunoprecipitated with anti-Dp (Left), anti-Rbf (Right), and nonspecific control antibodies (IgG and anti-Myc on the Left and Right panel, respectively). Recruitment measured by qPCR flanking the E2F binding sites of the following genes (A and B) Gpdh, (C and D) Pgk, (E and F) kdn, and (G and H) Ald1. The negative site (NS) does not contain predicted E2F-binding sites. Scatter dot plots with bars, mean ± SD, fold enrichment relative to the positive site, Apr53D, for each ChIP sample. N = 2 independent experiments. Genomic location of primers amplifying site1 and site2 are indicated in Fig. 1 F, I, and J. (I–L) The expression of the genes (I) Gpdh, (J) Ald1, (K) kdn, and (L) Pgk measured by RT-qPCR in whole animals staged at third instar larva, mid pupa, pharate, and 1-d-old adults. Fold change relative to control. Scatter dot plots with bars, mean ± SEM, N = 3 samples/group, multiple unpaired t tests followed by corrected FDR method (Benjamini and Yekutieli), q-value for each comparison is indicated in the plot. Full genotypes: (A–L) w1118, (A, B, and I) w1118;GpdhΔE2F;+, (C, D, and L) w1118;PgkΔE2Fline12;+, (E, F, and K) w1118,kdnΔE2F;+; +, (G, H, and J) w1118;+;Ald1ΔE2F

To determine how the changes in the recruitment of E2F/Dp/Rbf impact the expression of the endogenous genes, RNA was isolated from w1118 control and from homozygous mutant GpdhΔE2F, PgkΔE2F, kdnΔE2F, Ald1ΔE2F, and Cyt-c-pΔE2F animals that were staged at midpupa and pharate. The expression of the corresponding genes was determined by RT-qPCR. There was no reduction in Cyt-c-p expression in cyt-c-pΔE2F (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B), which was expected given that recruitment of Dp was not affected (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). In the GpdhΔE2F and Ald1ΔE2F lines, the expression of Gpdh and Ald1 genes were slightly reduced respectively, even though the changes were not statistically significant for Ald1 (Fig. 2 I and J). The level of the kdn messenger RNA (mRNA) showed a greater reduction in its expression in the kdnΔE2F line. However, it was accompanied by larger variation among the replicates and, therefore, the difference in the expression of kdn between the wild type and the kdnΔE2F line was not statistically significant (Fig. 2K).

The strongest effect on gene expression was observed in the PgkΔE2F line. The expression of Pgk was reduced several folds in PgkΔE2F at both midpupal and pharate stages (Fig. 2L). We expanded the analysis and examined Pgk expression at larval and adult stages and found it to be similarly reduced (Fig. 2L), thus suggesting that mutating E2F binding sites affects the level of Pgk mRNA throughout development. We confirmed that Pgk expression was reduced using another, independently generated, PgkΔE2F line (line 23, SI Appendix, Fig. S1C) (for details see: Materials and Methods). To exclude the possibility that mutations on the E2F site in PgkΔE2F affect the expression of the neighboring gene Bacc, the level of Bacc mRNA was measured by RT-qPCR. We found these to be relatively unaffected between control and PgkΔE2F (SI Appendix, Fig. S1D).

We concluded that E2F binding sites in PgkΔE2F are required for the recruitment of E2F/Dp/Rbf to the Pgk gene and mediate the full activation of Pgk expression throughout development. The effects associated with targeted mutations in the PgkΔE2F allele are highly specific. Given that among the five generated alleles that targeted the E2F sites, the PgkΔE2F allele had the strongest effect on both recruitment of E2F/Dp/Rbf and gene expression, we selected PgkΔE2F for further analysis.

Mutation of E2F Sites in PgkΔE2F Lines Severely Reduced Levels of Glycolytic and TCA Cycle Intermediates.

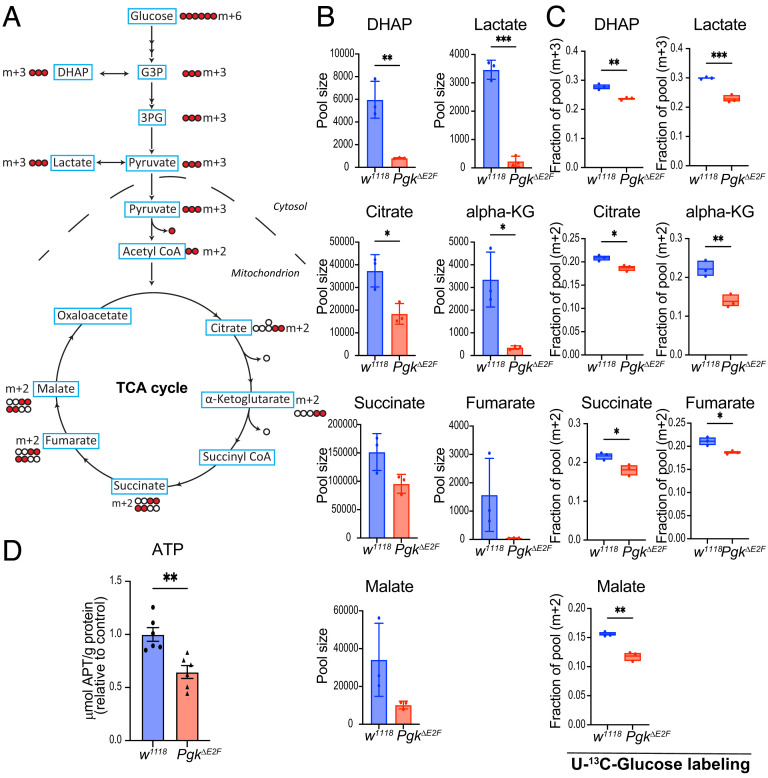

Pgk catalyzes one of the final steps in glycolysis. The reduction of Pgk expression in PgkΔE2F mutant raises the question whether it leads to an alteration in metabolic homeostasis. To address this question, we measured the steady-state levels of the glycolytic and TCA cycle intermediates (Fig. 3A). We collected 5-d-old PgkΔE2F and w1118 control males that were reared in identical noncrowded conditions and determined the levels of selected metabolites by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (Fig. 3B). Given that PGK is a glycolytic enzyme we first examined the level of lactate that is commonly used as a readout of glycolytic activity. Lactate pool size was strongly reduced in PgkΔE2F mutant animals (Fig. 3B). The level of dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) that is interconverted with glycose-3-phosphate (G3P) and, thus, can be used as a proxy for the G3P level, was also reduced. Our results suggest that the glycolytic intermediates both downstream of Pgk (lactate) and upstream of Pgk (DHAP) are reduced. Thus, our findings indicate that the activity of the glycolytic pathway is perturbed in PgkΔE2F mutants.

Fig. 3.

Metabolic changes in PgkΔE2F. (A) Glucose flux in the stable isotope tracing experiment showing the fate of 13C from 13C-glucose through glycolysis and TCA cycle. (B) Steady-state levels of lactate, dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP), citrate, alpha-ketoglutarate (alpha-KG), succinate, fumarate, and malate measured by GC-MS in w1118 and PgkΔE2F 5-d-old males. Scatter dot plots with bars, mean ± SD, unpaired t test: *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01. (C) Contribution of 13C glucose to DHAP, lactate, citrate, α-ketoglutarate, and malate after 12 h of treatment. M + 3 and M + 2-labeled fractions of pool representing direct flux of 13Cglucose into glycolysis and TCA cycle, respectively. Box plot, whiskers min to max values, line at mean, unpaired t test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. n = 3 samples/group, N = 2 independent experiments. (D) ATP levels measured in 5-d-old males by luminescence. Total µmol ATP normalized to g protein. Scatter dot plot with bars, mean ± SEM, unpaired t test, **P < 0.01, n = 3 samples/genotype, N = 2 independent experiments. Genotypes: w1118 and w1118;PgkΔE2Fline12;+

Pyruvate, the end product of glycolysis, shuttles into mitochondria to fuel the TCA cycle and, thus, serves as a major substrate for the generation of mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate (ATP) through oxidative phosphorylation. Accordingly, we found a severe reduction in the total levels of several TCA cycle metabolites in PgkΔE2F mutants, specifically, alpha-ketoglutarate (alpha-KG), malate and fumarate, and to a less extent succinate and citrate (Fig. 3B). To determine whether low levels of TCA intermediates are due to reduced glycolytic activity in PgkΔE2F mutant, we used 13C-glucose to measure the incorporation of the [U-13C] into the glycolytic and TCA cycle metabolites. Adult flies were fed on a 13C-glucose diet for 12 h and then harvested, and the samples were processed to measure isotope-labeled metabolites by GC-MS. Consistent with the reduction in the steady-state levels of glycolytic and TCA cycle intermediates (Fig. 3B), the 13C-labeled DHAP and lactate (m+3 isotopologue) were reduced in PgkΔE2F mutant compared to control (Fig. 3C). Strikingly, there was a corresponding decrease in the 13C fraction for several TCA cycle intermediates. The 13C-labeled (m+3) citrate, alpha-KG, succinate, fumarate, and malate were significantly lower than in wild type, thus pointing to a reduction in the glucose flux into the TCA cycle (Fig. 3C). To determine whether abnormal TCA cycle would lead to defects in ATP production, we measured the ATP level using the bioluminescent assay for the quantitative determination of ATP. The levels of ATP were strongly reduced in the PgkΔE2F mutant (Fig. 3D), and these findings were confirmed in another independent line with the PgkΔE2F allele (line 23, SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

Our data show that mutating the E2F sites in the PgkΔE2F line leads to a reduction in glycolytic activity and disruption of the TCA cycle. Consequently, the generation of ATP is significantly reduced. Thus, we concluded that the loss of E2F regulation on Pgk gene expression induces severe metabolic defects.

The Loss of E2F Regulation on Pgk Gene Expression Leads to Mitochondrial Defects.

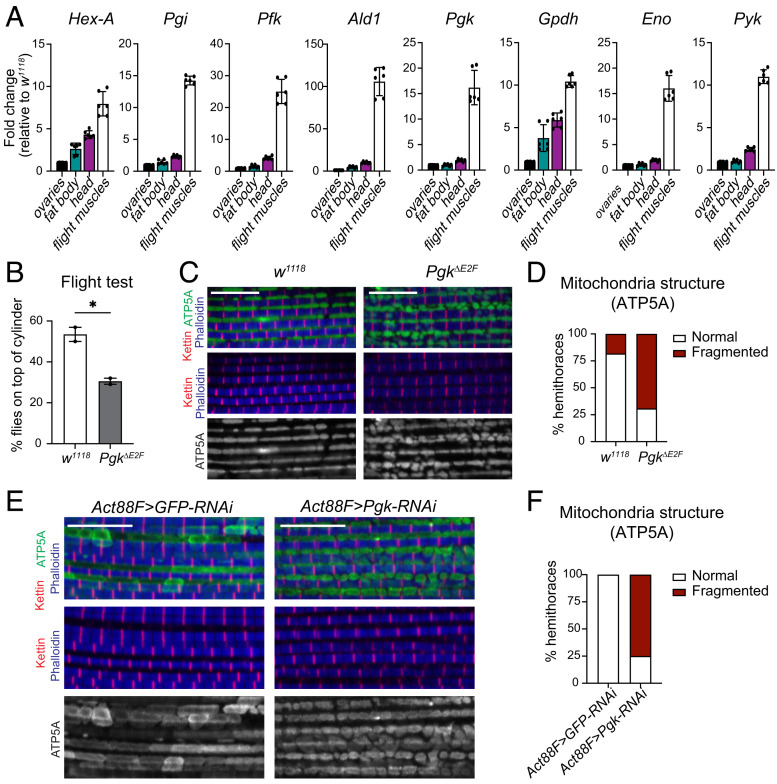

We reasoned that the tissues expressing high levels of Pgk mRNA will likely be more sensitive to reduced Pgk expression. To determine which organ has the highest expression of Pgk, RNA was extracted from different tissues dissected from adult female flies. The level of Pgk mRNA across ovaries, dorsal abdomen containing fat body, and head and flight muscles was measured by RT-qPCR. Notably, the Pgk mRNA was approximately 15-fold higher in flight muscles than in other organs (Fig. 4A). Since the expression of the glycolytic genes is coordinately regulated during development, we extended our analysis beyond Pgk and compared relative expression of other glycolytic genes among these tissues. Indeed, the levels of phosphoglucose isomerase (Pgi), phosphofructokinase (Pfk), enolase (Eno), and Pyk transcripts were 10-fold to 20-fold higher in flight muscles than in other tissues, and the increase was almost 100-fold for Ald1 expression (Fig. 4A). These results are consistent with high energy demand in the muscles and the major role of glycolysis in energy metabolism and ATP generation to sustain muscle function (27).

Fig. 4.

Mitochondrial defects in PgkΔE2F led to dysfunctional muscles. (A) The expression of the glycolytic genes Hex-A, Pgi, Pfk, Ald1, Pgk, Gpdh, Eno, and Pyk measured by RT-qPCR in dissected ovaries, head, flight muscles, and dorsal abdomen containing fat body tissue in 2 to 3-d-old females. Fold change relative to control. Scatter dot plots with bars, mean ± SD, N = 3 samples/group. (B) Flight ability scored by quantifying the percentage of flies landing on top section of the column; 5- to 7-d-old males were tested. Scatter dot plots with bars, mean ± SEM, unpaired t test, *P < 0.05, N = 196 (w1118) and 158 (PgkΔE2F), N = 2 independent experiments. (C) Confocal section images of flight muscles in a sagittal view. Hemithorax sections of 5-d-old males stained with Phalloidin (blue), anti-kettin (red), and anti-ATP5A (green). (D) Quantification of percentage of hemithoraces displaying either normal morphology of mitochondria or fragmented shape (i.e., round). Stacked bars, N = 11 to 13 hemithoraces/group, (E) same as C, (F) same as D, N = 11 to 12 hemithoraces/group. Scale 10 μm. Genotypes: (A–D) w1118, (B–D) w1118;PgkΔE2Fline12;+, (E and F) Act88F-GAL4/Y;UAS-GFP-RNAi;+, and Act88F-GAL4/Y;+;UAS-Pgk-RNAiGL00101.

The indirect flight muscles are the largest muscles among the thoracic muscles, and their main role is to provide power to fly. We used a flight test assay to quantitatively assess muscle function in the PgkΔE2F mutant flies. In this test, flies are tapped into a cylinder coated with mineral oil. Wild-type animals land in the top part of the cylinder, while flies with dysfunctional flight muscle land in the lower part or at the bottom of the cylinder. The flight test revealed that the muscle function is compromised in the PgkΔE2F mutant flies, as significantly less PgkΔE2F mutant animals landed in the top part of the cylinder in comparison to control flies (Fig. 4B). This result was confirmed with the independent PgkΔE2F mutant line (line 23, SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). Given the significance of these findings, we confirmed that the expression of Pgk, measured by RT-qPCR specifically in flight muscles, was significantly reduced in PgkΔE2F mutants (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). Thus, defects in the flight test are likely a direct result of low Pgk expression in PgkΔE2F flight muscles.

To determine whether the weakness in muscle function of the PgkΔE2F mutants was due to an overall defect in muscle structure, we dissected the indirect flight muscles and stained these with phalloidin and anti-Kettin antibody to visualize sarcomeres, as well as anti-ATP5A antibody to label mitochondria. The wild-type muscles displayed a regular array of sarcomeres and the shape of their mitochondria was globular and highly elongated (Fig. 4 C, Left). While the sarcomere structure of the PgkΔE2F mutant muscles was largely indistinguishable from the wild type, the mitochondrial morphology was highly abnormal. Specifically, the shape of mitochondria was highly fragmented and round (Fig. 4 C and D), which is indicative of mitochondrial disfunction (28). We confirmed the results using a second independently established PgkΔE2F mutant line (line 23, SI Appendix, Fig. S3 C and D). Furthermore, defective mitochondria morphology was accurately phenocopied by knocking down the expression of Pgk using an UAS-Pgk-RNAiGL00101 line driven by the flight muscle driver Act88F-GAL4 (Fig. 4 E and F). Thus, our data strongly suggest that the reduced expression of Pgk in PgkΔE2F mutants results in dysfunctional mitochondria, consistent with low ATP generation, and thus consequently, leads to defective muscles.

The PgkΔE2F Allele Reduces Chromatin Accessibility That Is Accompanied by Low Expression of Metabolic Genes.

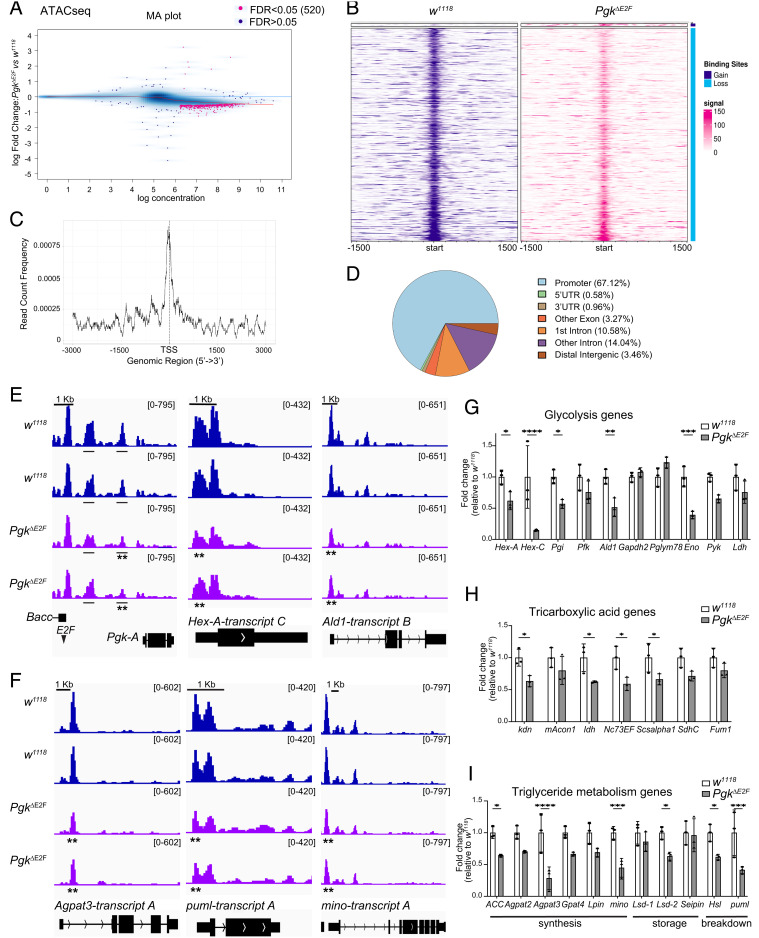

Accumulating evidence suggests that many metabolites serve as cofactors for histone-modifying enzymes that play a central role in epigenetic regulation (29–31). One of the striking consequences of the loss of E2F regulation of the Pgk gene is the severe reduction in several glycolytic and TCA cycle intermediates raising the possibility that these defects may lead to epigenetic changes. To test this idea, we analyzed the global epigenetic landscape in PgkΔE2F mutants using the assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with high-throughput sequencing (ATAC-seq). Nuclei from flight muscles of pharate animals were collected and treated with Tn5 transposase followed by PCR to map chromatin accessibility genome-wide (32). Genomic regions displaying active chromatin regions are open, not densely packed by nucleosomes, and are therefore amplified and sequenced. Over twenty-five thousand regions peaks were identified as open chromatin regions (Dataset S1). Each peak was annotated to promoter, 5′ untranslated region, 3′ untranslated region, exon, intron, or intergenic region and assigned to the closest TSS using ChIPseeker package (33) (Dataset S2).

Next, we compared the chromatin accessibility among sites in common between PgkΔE2F and control animals using DiffBind (34). We identified a subset of 513 genomic regions showing a significant reduction in peak intensity in PgkΔE2F mutants and only seven genomic regions with a significant increase (False Discovery Rate (FDR) < 0.05, Fig. 5 A and B and SI Appendix, S4A). Peaks showing significant changes in chromatin accessibility were annotated to the nearest TSS using ChIPSeeker (33). Only 3.5% of peaks were in distal intergenic regions, while 29.4% were mapped to the gene and 67.1% were located at the promoter site (Fig. 5 C and D and Dataset S3). A gene set enrichment analysis was performed using clusterProfiler (35) to determine the overrepresentation of gene ontology terms among the 513 regions that showed a significant reduction in chromatin accessibility in PgkΔE2F mutants. The biological processes related to development, morphogenesis, and differentiation, including muscle development, were among the most significant GO terms (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B and Dataset S4). Concordantly, the cellular compartment terms related to actin cytoskeleton and muscles, such as fiber, sarcomere, and myofibril, were significantly enriched (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C and Dataset S4). Lastly, we found that numerous molecular function terms related to transcription were also enriched (SI Appendix, Fig. S4D and Dataset S4), thus suggesting that changes in global gene expression are associated with an overall reduction in chromatin accessibly in PgkΔE2F mutants. Interestingly, several metabolic genes displayed reduced chromatin accessibility. These included Pgk, Hexokinase A (Hex-A), and Ald1 from the glycolytic pathway and 1-Acylglycerol-3-phosphate O-acyltransferase 3 (Agpat3), Lipin (Lpin), minotaur (mino), and pummelig (puml) from lipid metabolism (Fig. 5 E and F and Dataset S3). We noticed that many other metabolic genes, such as Mitochondrial aconitase 1 (mAcon1), Pyk, Lipid storage droplet-2 (Lsd-2), Pfk, Isocitrate dehydrogenase (Idh), Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), and others, had apparent reduction in peak signal albeit with a higher FDR (FDR < 0.1, Dataset S3). Thus, ATAC-seq reveals that chromatin accessibility is broadly reduced in PgkΔE2F mutants.

Fig. 5.

Reduction in chromatin accessibility and gene expression in PgkΔE2F (A) MA plot representing differential chromatin accessibility analyzed using DiffBind. The common 23,315 sites for ATAC-seq between PgkΔE2F and control animals plotted as a blue cloud. FDR < 0.05 cutoff (pink dots). The x axis values (“log concentration”) represent logarithmically transformed, normalized counts, averaged for all samples, for each site. The y axis values represent log 2 (fold change) values in PgkΔE2F relative to w1118. (B) Heatmaps showing the enrichment of ATAC reads in a 3,000 bp window centered on the summit for each peak. Scale is as indicated in the signal. Only 520 sites with differential chromatin accessibility are included, in which seven sites show a gain in enrichment in PgkΔE2F and 513 show a loss (reduction). (C) Distribution of reads for ATAC-seq data in a 6,000 bp window centered on the TSS of the gene for each peak. Only the 520 sites with differential chromatin accessibility in PgkΔE2F are included. (D) Peak annotation pie chart for the 520 sites with differential chromatin accessibility in PgkΔE2F. (E and F) Differential chromatin accessibility determined by ATAC-seq visualized with Integrative Genomics Viewer browser for the genomic regions surrounding (E) the glycolytic genes: Pgk, Hex-A, and Ald1, and (F) the lipid metabolism genes: Agpat3, puml, and mino. The most predominantly expressed transcript in adult flies, based on the FlyAtlas 2 profile (25), is displayed; n = 2 samples/genotype, each track is shown separately for each replicate. Read scales and genomic scales included on top right and top left, respectively. GroupAuto scale. **FDR < 0.05 in chromatin accessibility. (G–I) The expression of the metabolic genes measured by RT-qPCR in whole animals staged at pharate. (F) glycolytic genes: Hex-A, Hex-C, Pgi, Pfk, Ald1, Gapdh2, Pglym78, Eno, Pyk, and Ldh (G) TCA genes: kdn, mAcon1, Idh, Oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (Nc73EF), Succinyl-coenzyme A synthase, alpha subunit 1 (Scsalpha1), Succinate dehydrogenase, subunit C (SdhC), and Fumarase 1 (Fum1) (H) lipid metabolism genes: ACC1, Acylglycerol-3-phosphate O-acyltransferase 2 (Agpat2), Agpat3, Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase 4 (Gpat4), Lpin, mino, Lipid storage droplet-1 (Lsd-1), Lsd-2, Seipin, Hormone-sensitive lipase (Hsl), and Puml. Fold change relative to control. Scatter dot plots with bars, mean ± SEM, N = 3 samples/group, multiple unpaired t tests followed by corrected Holm–Šídák method for multiple comparison correction. *P < 0.05. Full genotypes: w1118 and w1118; PgkΔE2F line12;+.

The reduced chromatin accessibility, particularly in promoter regions, indicates potential changes in the expression of the corresponding genes. Therefore, we examined the expression of the metabolic genes that showed reduced ATAC peak intensity in PgkΔE2F mutants. RNA was isolated from animals staged at pharate, and gene expression was measured by RT-qPCR. Remarkably, the levels of metabolic genes mentioned above Hex-A, Ald1, Agpat3, Lpin, mino, and puml were significantly reduced in both PgkΔE2F mutant lines compared to w1118 (Fig. 5 G–I and SI Appendix, S4 E and F). Interestingly, there was also a reduction in the expression of mAcon1, Pyk, Lsd-2, Pfk, Idh, and ACC that had low chromatin accessibility, but with a higher FDR value (FDR < 0.1, Dataset S3). Next, we examined the rest of the glycolytic, TCA cycle, and lipid metabolism genes and found that, in total, almost half of them were significantly reduced, while the remaining genes exhibited a similar trend albeit the changes were not statistically significant (Fig. 5 G–I and SI Appendix, Fig. S4 E and F). Given that the recruitment of Dp and Rbf to the other metabolic targets, such as the Ald1 gene, was unaltered, as shown in Fig. 2 C and D, we concluded that the changes in gene expression in PgkΔE2F mutants, described above, are not due to abnormal recruitment of E2F/Dp/Rbf.

To confirm that the changes in the expression of metabolic genes were specific to PgkΔE2F mutants, we examined the expression of the same panel of genes in heterozygous flies carrying a hypomorphic mutant allele PgkKG06443. As expected, there was a two-fold reduction in the Pgk mRNA levels in PgkKG06443 heterozygotes (SI Appendix, Fig. S4G). However, unlike PgkΔE2F mutants, in which the Pgk expression is downregulated several folds, the expression of glycolytic and TCA cycle genes were indistinguishable between PgkKG06443 heterozygous and control animals (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 H and I).

In Drosophila, estrogen-receptor–related (ERR) directs a transcriptional induction that promotes glycolysis, TCA cycle, and electron transport chain during pupal development (36). Interestingly, ERR expression was reduced in both PgkΔE2F mutant alleles but not in PgkKG06443 heterozygotes (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 J and K).

Thus, we concluded that the loss of E2F regulation on the Pgk gene results in a broad reduction in chromatin accessibility that may reflect changes in the global epigenetic profile. Importantly, many metabolic genes associated with decreased accessibility regions were expressed at low levels in PgkΔE2F mutants.

The Loss of E2F Regulation on Pgk Gene Has a Broad Impact on Adult Physiology.

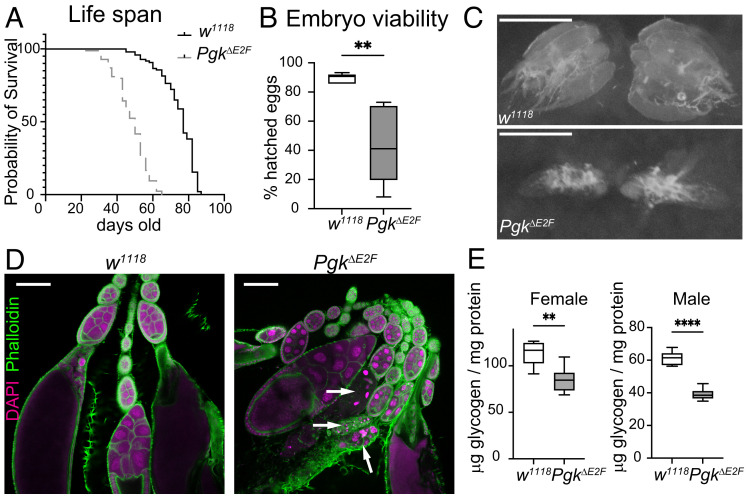

The data described above show that the low expression of Pgk in PgkΔE2F animals severely impacts the levels of glycolytic and TCA cycle intermediates and the generation of ATP, which impairs the function of high-energy consuming organs, such as muscles. These observations raise the question, what other physiological functions are affected in PgkΔE2F mutant? Given that previous studies of a temperature-sensitive allele Pgk allele, nubian, have shown that it shortens the life span (37), we measured the life span of PgkΔE2F animals and found it to be similarly affected. The median survival of PgkΔE2F males was significantly reduced in both independent lines carrying the PgkΔE2F allele compared to w1118 (Fig. 6A and SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). Additionally, we noticed that fewer larvae were hatching from eggs in both independent PgkΔE2F lines (Fig. 6B and SI Appendix, Fig. S5B), thus, indicating reduced embryonic viability in PgkΔE2F mutants. Given that this phenotype can be associated with poor oocyte quality (38), we explored oocyte production. We dissected ovaries from both PgkΔE2F-independent mutant animals and found that roughly 30% of their ovaries were smaller than those in control animals (Fig. 6C and SI Appendix, Fig. S5C). Next, we stained PgkΔE2F and control ovarioles with anti-Arm, phalloidin, and DAPI to visualize the overall structure of the egg chambers. Remarkably, in agreement with the small size in ovaries, we consistently observed degenerated egg chambers at stages 7 to 8 in both PgkΔE2F-independent mutant lines (Fig. 6D and SI Appendix, Fig. S5D). Degenerated egg chambers were evidenced by the condensation of the chromatin in nurse cell nuclei at midoogenesis, thus indicating that egg chambers were undergoing apoptosis at the onset of vitellogenesis. The choice between egg development or apoptosis is determined by the midoogenesis checkpoint that relays on the nutritional status of the female and other hormonal signals (39). When PgkΔE2F egg chambers passed the midoogenesis checkpoint, the uptake of both lipid and glycogen, which was analyzed at stage 10 by staining ovarioles with Bodipy and Periodic acid Schiff, respectively, proceeded normally compared to control egg chambers (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 E and F).

Fig. 6.

Impact on adult physiology and development in PgkΔE2F. (A) Adult life span determined as survival curves in male flies. Kaplan–Meier analysis, P < 0.0001, median survival = 77 (w1118) and 50 (PgkΔE2F). N = 97 and 84 flies/genotype. (B) Percentage of hatched eggs quantified as number of first instar larva over number of laid eggs. Box plot and whiskers represent 5 to 95 percentile. Mann–Whitney U test, **P < 0.01. N = 533 eggs for w1118 and 496 for PgkΔE2F. (C) Representative images of the ovaries found in ~20 to 40% of females, scale 500 μm. (D) Confocal section images of ovarioles dissected out of 2 to 3-d-old females. Ovaries were stained with Phalloidin (green) and DAPI (magenta). Condensed and fragmented nurse cell nuclei, indicating degenerated egg chambers (white arrows), found in ~30% ovaries at midoogenesis (around st8), scale 100 μm. (E) Measurement of total whole-body glycogen content in 5-d-old females and males normalized to protein content. Box plot and whiskers represent 5 to 95 percentile, n = 6 sample/group, N = 2 independent experiments, unpaired t test, **P < 0.01. One representative experiment shown. Full genotypes: w1118 and w1118;PgkΔE2Fline12;+.

The arrest in oogenesis could be indicative of insufficient energetic storage required to meet the biosynthetic demands for egg production (40). As glycogen is a major source of energy storage, we measured its level in the whole animals and normalized the total glycogen content to the protein content. The level of glycogens in both males and females were significantly reduced in the PgkΔE2F mutant compared to the control animals w1118 (Fig. 6E). This observation was confirmed in another line carrying the PgkΔE2F mutant allele (line 23, SI Appendix, Fig. S5G).

Thus, we concluded that the loss of E2F binding sites that contribute to activating the expression of the Pgk gene broadly impacts animal physiology and leads to shortening of life span. In addition, we found that it results in reduced embryonic survival, smaller ovaries, degenerated egg chambers, and reduced glycogen storage, which represent novel phenotypes associated with low Pgk levels. Collectively, these results illustrate a broad manifestation of the metabolic disbalance in the PgkΔE2F mutant at the organismal level.

Discussion

E2F regulates thousands of genes and is involved in many cellular functions (10, 12, 41–43). One of the central unresolved issues is whether E2F function is the net result of regulating all E2F targets or only a few key genes. However, the importance of individual E2F targets cannot simply be deduced by either examining global transcriptional changes in E2F-deficient cells or analyzing ChIP-validated lists of E2F targets. The most straightforward approach is to mutate E2F sites in the endogenous E2F targets, yet this was done in very few studies (44–46). Genome editing tools provided us with the opportunity to begin addressing this question by systematically introducing point mutations in E2F sites of genes involved in the same biological process. Despite using the same stringent criteria in mining proteomic, transcriptomic, and ChIP-seq to select E2F targets, we find that this knowledge is largely insufficient to predict the functionality of E2F binding sites, as well as the contribution of E2F in controlling the expression of individual targets. Notably, we showed that among five, similarly high-confidence metabolic targets, the loss of E2F regulation is particularly important only for the Pgk gene (Table 1). Our findings underscore the value of this approach in dissecting the function of the transcription factor E2F.

Table 1.

Summary of the effects on mutating E2F sites among five metabolic genes

| Gene | No. of E2F sites | Reduction in protein levels in Mef2>Dp-RNAi compared to control | Activation by E2f1 in luciferase reporter assays | ΔE2F flies | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT-Luc | ΔE2F-Luc | E2F/Dp/Rbf recruitment | Reduction in gene expression | |||

| Ald1 | 1 | Yes | No | NA | Loss | Mild |

| Pgk | 4 | Yes | Strong | Mild | Loss | Strong |

| Gpdh | 1 | Yes | Strong | No | Partial loss | Mild |

| kdn | >7 | Yes | Strong | No | Partial loss | Mild |

| Cyt-c-p | 4 | Yes | No | NA | No effect | No effect |

The availability of orthogonal datasets for proteomic changes in Dp-deficient muscles combined with genome-wide binding for Dp and Rbf in the same tissue allowed us to select for target genes that should be highly dependent on E2F regulation. Surprisingly, we find significant variation in the recruitment of E2F/Dp/Rbf and the expression of the target gene upon mutating E2F sites among five metabolic genes (Table 1). Neither the number of E2F sites, their positions, nor the response of the luciferase reporter to E2F1 is sufficient to predict E2F regulation of the endogenous targets in vivo. Strikingly, although Cyt-c-p contained multiple E2F binding sites, the introduction of mutations in all these sites had no effect on the recruitment of E2F/Dp/Rbf and the expression of Cyt-c-p. For the remaining genes, mutations in the core element of the E2F binding sites reduced the recruitment of E2F/Dp/Rbf and, consequently, the expression of the target gene albeit to various degrees. Our work illustrates that the contribution of E2F in gene expression regulation is highly context- and target-dependent and that one could not simply predict the functionality of E2F binding sites or the importance of a target by relying on existing transcriptomic, proteomic, and ChIP-seq datasets.

One explanation for the partial loss of binding for Dp and Rbf in the GpdhΔE2F and kdnΔE2F lines is that since the whole animal was used for ChIP-qPCR, we cannot distinguish whether the reduction in the recruitment is due to the loss of E2F binding in either a subset of cells or across all cells, thus consistent with a tissue-specific role of E2F. Another possibility is that E2F still retains a weak affinity to the mutant sequence. It is also possible that E2F sites are not the only DNA elements that recruit E2F complexes to chromatin. Indeed, other DNA sequences, such as cell cycle homology region sites, were shown to help in tethering the E2F complex to DNA as a part of the MuvB complex (47). Additionally, it has been suggested that other DNA binding factors may facilitate E2F binding (14, 48). Overall, our results suggest that unlike in vitro assays with recombinant proteins, mutation of E2F sites does not always fully prevent the recruitment of E2F in vivo.

In Drosophila, the E2F activity is a net effect of the activator E2F1/Dp and the repressor E2F2/Dp complexes that work antagonistically at cell cycle promoters during development (49). One limitation of the approach described here is that it does not distinguish the relative contribution of activator and repressor E2Fs. In earlier studies, in which the roles of E2F1, E2F2, and Rbf were examined during flight muscles development (12, 23), we found that unlike E2F1, the loss of E2F2 is largely inconsequential, while Rbf acts as an activator. Given that the mutations in E2F sites did not lead to an increase in gene expression, our data are consistent with the idea that the repressive E2F2/Dp complex does not have a major contribution in this particular context for these genes.

Among five genes that we analyzed here, mutating E2F sites upstream Pgk gene completely prevents the recruitment of E2F/Dp/Rbf and results in several-fold reduction in the expression of the Pgk gene. The neuron-specific Pgk knockdown markedly decreases the levels of ATP and results in locomotive defects (50). In another study, flies carrying a temperature-sensitive allele of Pgk, nubian, exhibit reduced lifespan and several-fold reduction in the levels of ATP (37). Thus, altered generation of ATP and shorten lifespan appear to be the hallmarks of diminished Pgk function in flies. Notably, the PgkΔE2F mutant animals show low glycolytic and TCA cycle intermediates and low ATP levels and die earlier, thus suggesting that in the absence of E2F regulation, the normal function of Pgk is compromised.

The loss of E2F function on the Pgk gene leads to defects in high energy–consuming organs, such as flight muscles and ovaries. The morphology of mitochondria is abnormal in PgkΔE2F and muscles are dysfunctional, as revealed by the flight test. The ovaries in PgkΔE2F females were smaller and contained a high number of degenerated egg chambers at the onset of vitellogenesis. Intriguingly, just like in the PgkΔE2F mutant animals, occasional degenerating early egg chambers (stage 8 and earlier) were previously described in the Dp and E2f1 mutants (51) raising the possibility that this aspect of the Dp mutant phenotype may be due to loss of E2F regulation on the Pgk gene. Interestingly, degenerating egg chambers have previously been associated with metabolic defects, including alteration in the TCA cycle intermediates (52), nutritional status (39, 40), and lipid transport (53). Egg chambers can degenerate before investing energy into egg production, in particular vitellogenesis. Given that multiple signals are integrated during the midoogenesis checkpoint, we reasoned that low levels of glycogen in PgkΔE2F mutants may contribute, at least to some extent, to egg chamber degeneration in PgkΔE2F mutants. Collectively, our data strongly argue that E2F is important for regulating the function of Pgk.

Recent studies revealed that metabolic intermediates can function as cofactors for histone-modifying enzymes by regulating their activities and therefore change chromatin dynamics. For example, alpha-KG is a cofactor for Jumonji C domain-containing histone lysine demethylases, and low alpha-KG levels can lead to histone hypermethylation (29, 30). In contrast, fumarate and succinate can serve as alpha-KG antagonists and inhibit lysine demethylases (31). Metabolic analysis of PgkΔE2F animals revealed a severe reduction in glycolytic and TCA cycle intermediates, including alpha-KG, succinate, and fumarate, thus, raising the possibility that activities for the histone demethylase are altered in PgkΔE2F mutants. Another metabolite affected in PgkΔE2F is lactate that serves as a precursor for a new histone modification known as lactylation that was shown to directly promote gene transcription (54). Our findings that the loss of E2F regulation on the Pgk gene is accompanied by changes in several metabolites, which can regulate the activity of multiple histone-modifying enzymes, raises the possibility that the epigenetic landscape may change. This idea is supported by altered chromatin accessibility at multiple loci in PgkΔE2F mutants, as revealed by ATAC-seq. Notably, it is accompanied by a reduction in the expression of several genes, including metabolic genes. The effect was specific to the loss of E2F regulation on the Pgk gene because it has been validated in two independent lines carrying the mutation on the E2F sites, while no changes in gene expression were observed in Pgk loss of function in heterozygous animals (hypomorph PgkKG06443). Interestingly, published microarray analysis for Pgknubian animals revealed changes in the expression of genes involved in glucose and lipid metabolism (37). In sum, our data suggest that abnormal flux through Pgk leads to changes in chromatin accessibility and, subsequently, transcriptional changes.

Comparison of transcriptomes, proteomes, and metabolomes for Rbf-deficient animals led to unexpected conclusion that very few of these metabolic changes actually corresponded to matching transcriptional changes at direct Rbf targets (55). This result raised the question of the relative importance of transcriptional regulation mediated by E2F/Rb function. Our observation that the loss of E2F regulation of a single glycolytic gene can affect chromatin accessibility and elicit broad transcriptional changes at numerous metabolic genes may provide an explanation for this discordance. Ironically, many glycolytic and mitochondrial genes that are misexpressed in PgkΔE2F mutants are E2F target genes based on ChIP-seq data. However, the changes in their expression occur without changes in E2F recruitment. Thus, the transcriptional changes observed in the E2F-deficient animals are indeed a complex combination of both direct effects of E2F at the target genes and indirect, yet E2F-dependent, effects at other targets as exemplified by Pgk. These indirect effects were missed when an entire E2F/Rbf module was inactivated. This finding further highlights the value of mutating E2F binding sites in individual E2F target genes to dissect different tiers of E2F regulation.

Materials and Methods

Detailed materials on the fly stocks, luciferase vectors, and generation of the CRISPR lines are listed in SI Appendix. Gene expression and occupancy enrichment measured by RT-qPCR, ChIP-qPCR follow standard procedures. Detailed methods are listed in SI Appendix, and primers are included in Dataset S5. The detailed methods and analysis for immunofluorescence, isotope labeling, ATAC-Seq, and other physiological assays are listed in SI Appendix. Statistical analysis was done using GraphPad Prism v9.4. Details regarding data presentation and statistical analysis were included in legends to Figures.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (XLSX)

Dataset S02 (XLSX)

Dataset S03 (XLSX)

Dataset S04 (XLSX)

Dataset S05 (XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Nick Dyson for critical reading of the manuscript and Kostas Chronis for advice with the assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with sequencing (ATAC-seq) experiments and analysis. We thank Adam Didier for making the Gpdh-WT-luc construct for luciferase reporter and R.M. Cripps for sharing fly stock Act88F-GAL4. Other stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (NIH P40OD018537). The α-Armadillo (N2-71A1) antibody was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank. We are grateful to Flybase for online resources on the Database of Drosophila Genes and Genomes. This work was supported by NIH grant R35GM131707 (M.V.F.).

Author contributions

M.P.Z. and M.V.F. designed research; M.P.Z., Y.-J.K., A.W., I.L., and H.M.L. performed research; A.B.M.M.K.I. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; M.P.Z., Y.-J.K., H.M.L, J.K., and M.V.F. analyzed data; and M.P.Z. and M.V.F. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. S.M.R. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

ATAC-seq data from this publication have been deposited to the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and assigned the identifier Series GSE217225 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE217225) (56). All other data are included in the manuscript and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Dyson N., The regulation of E2F by pRB-family proteins. Genes Dev. 12, 2245–2262 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dyson N. J., RB1: A prototype tumor suppressor and an enigma. Genes Dev. 30, 1492–1502 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubin S. M., Sage J., Skotheim J. M., Integrating old and new paradigms of G1/S control. Mol. Cell 80, 183–192 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinberg R. A., The retinoblastoma protein and cell cycle control review. Cell 81, 323–330 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blais A., Dynlacht B. D., Hitting their targets: An emerging picture of E2F and cell cycle control. Curr. Opin. Genet Dev. 14, 527–532 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muller H., et al. , E2Fs regulate the expression of genes involved in differentiation, development, proliferation, and apoptosis. Genes Dev. 2, 267–285 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Julian L. M., et al. , Tissue-specific targeting of cell fate regulatory genes by E2f factors. Cell Death Differ 23, 1–11 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denechaud P. D., et al. , E2F1 mediates sustained lipogenesis and contributes to hepatic steatosis. J. Clin. Inves. 126, 137–150 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Georlette D., et al. , Genomic profiling and expression studies reveal both positive and negative activities for the Drosophila Myb MuvB/dREAM complex in proliferating cells. Genes Dev. 21, 2880–96 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korenjak M., Anderssen E., Ramaswamy S., Whetstine J. R., Dyson N. J., RBF binding to both canonical E2F targets and noncanonical targets depends on functional dE2F/dDP complexes. Mol. Cell Biol. 32, 4375–87 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dimova D. K., Stevaux O., Frolov M. V., Dyson N. J., Cell cycle-dependent and cell cycle-independent control of transcription by the Drosophila E2F/RB pathway. Genes Dev. 17, 2308–20 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zappia M. P., Rogers A., Islam A. B. M. M. K., Frolov M. V., Rbf activates the myogenic transcriptional program to promote skeletal muscle differentiation. Cell Rep. 26, 702–719.e6 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chicas A., et al. , Dissecting the unique role of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor during cellular senescence. Cancer Cell 17, 376–387 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabinovich A., Jin V. X., Rabinovich R., Xu X., Farnham P. J., E2F in vivo binding specificity: Comparison of consensus versus nonconsensus binding sites. Genome Res. 18, 1763–1777 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duronio R. J., O’Farrell P. H., Xie J.-E., Brook A., Dyson N., The transcription factor E2F is required for S phase during Drosophila embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 9, 1445–1455 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lukas J., et al. , Cyclin E-induced S phase without activation of the pRb/E2F pathway. Genes Dev. 11, 1479–1492 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neufeld T. P., de la Cruz A. F. A., Johnston L. A., Edgar B. A., Coordination of growth and cell division in the Drosophila wing. Cell 93, 1183–1193 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herr A., et al. , Identification of E2F target genes that are rate limiting for dE2F1-dependent cell proliferation. Dev. Dyn. 241, 1695–1707 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van den Heuvel S., Dyson N. J., Conserved functions of the pRB and E2F families. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 713–724 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frolov M. V., Moon N.-S., Dyson N. J., dDP Is needed for normal cell proliferation. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 3027–3039 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Royzman I., Whittaker A. J., Orr-Weaver T. L., Mutations in Drosophila DP and E2F distinguish G1-S progression from an associated transcriptional program. Genes Dev. 11, 1999–2011 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guarner A., et al. , E2F/DP prevents cell-cycle progression in endocycling fat body cells by suppressing dATM expression. Dev. Cell 43, 689–703.e5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zappia M. P., Frolov M. V., E2F function in muscle growth is necessary and sufficient for viability in Drosophila. Nat. Commun. 7, 1–16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zappia M. P., et al. , E2f/dp inactivation in fat body cells triggers systemic metabolic changes. Elife 10, e67753 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leader D. P., Krause S. A., Pandit A., Davies S. A., Dow J. A. T., FlyAtlas 2: A new version of the Drosophila melanogaster expression atlas with RNA-Seq, miRNA-Seq and sex-specific data. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D809–D815 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sawado T., et al. , The DNA replication-related element (DRE)/DRE-binding factor: System is a transcriptional regulator of the Drosophila E2F gene. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 26042–26051 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chatterjee N., Perrimon N., What fuels the fly: Energy metabolism in Drosophila and its application to the study of obesity and diabetes. Sci. Adv. 7, eabg4336 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Avellaneda J., et al. , Myofibril and mitochondria morphogenesis are coordinated by a mechanical feedback mechanism in muscle. Nat. Commun. 12, 2091 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsukada Y. I., et al. , Histone demethylation by a family of JmjC domain-containing proteins. Nature 439, 811–816 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whetstine J. R., et al. , Reversal of histone lysine trimethylation by the JMJD2 family of histone demethylases. Cell 125, 467–481 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao M., et al. , Inhibition of α-KG-dependent histone and DNA demethylases by fumarate and succinate that are accumulated in mutations of FH and SDH tumor suppressors. Genes Dev. 26, 1326–1338 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buenrostro J. D., Wu B., Chang H. Y., Greenleaf W. J., ATAC-seq: A method for assaying chromatin accessibility genome-wide. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2015, 21.29.1-21.29.9 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu G., Wang L. G., He Q. Y., ChIP seeker: An R/Bioconductor package for ChIP peak annotation, comparison and visualization. Bioinformatics 31, 2382–2383 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stark R.,Brown G.,DiffBind: Differential binding analysis of ChIP-Seq peak data https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DiffBind.html. Accessed 11 September 2022.

- 35.Yu G., Wang L. G., Han Y., He Q. Y., ClusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 16, 284–287 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beebe K., et al. , Drosophila estrogen-related receptor directs a transcriptional switch that supports adult glycolysis and lipogenesis. Genes Dev. 34, 701–714 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang P., et al. , A Drosophila temperature-sensitive seizure mutant in phosphoglycerate kinase disrupts ATP generation and alters synaptic function. J. Neurosci. 24, 4518–4529 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gandara A. C. P., Drummond-Barbosa D., Warm and cold temperatures have distinct germline stem cell lineage effects during Drosophila oogenesis. Development 149, dev200149 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCall K., Eggs over easy: Cell death in the Drosophila ovary. Dev. Biol. 274, 3–14 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drummond-Barbosa D., Spradling A. C., Stem cells and their progeny respond to nutritional changes during Drosophila oogenesis. Dev. Biol. 231, 265–278 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weinmann A. S., Yan P. S., Oberley M. J., Huang T. H. M., Farnham P. J., Isolating human transcription factor targets by coupling chromatin immunoprecipitation and CpG island microarray analysis. Genes Dev. 16, 235–244 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu X., et al. , A comprehensive ChIP-chip analysis of E2F1, E2F4, and E2F6 in normal and tumor cells reveals interchangeable roles of E2F family members. Genome Res. 17, 1550–61 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cam H., et al. , A common set of gene regulatory networks links metabolism and growth inhibition. Mol. Cell 16, 399–411 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tavner F., Frampton J., Watson R. J., Targeting an E2F site in the mouse genome prevents promoter silencing in quiescent and post-mitotic cells. Oncogene 26, 2727–2735 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Payankaulam S., Hickey S. L., Arnosti D. N., Cell cycle expression of polarity genes features Rb targeting of Vang. Cells Dev. 169, 203747 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burkhart D. L., Wirt S. E., Zmoos A. F., Kareta M. S., Sage J., Tandem E2F binding sites in the promoter of the p107 cell cycle regulator control p107 expression and its cellular functions. PLoS Genet. 6, 1–16 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Müller G. A., et al. , The CHR site: Definition and genome-wide identification of a cell cycle transcriptional element. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 10331–10350A (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanidas I., et al. , Chromatin-bound RB targets promoters, enhancers, and CTCF-bound loci and is redistributed by cell-cycle progression. Mol. Cell 82, 3333–3349 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frolov M. V., et al. , Functional antagonism between E2F family members. Genes Dev. 15, 2146–2160 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shimizu J., et al. , Novel Drosophila model for parkinsonism by targeting phosphoglycerate kinase. Neurochem. Int 139, 104816 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Royzman I., et al. , The E2F cell cycle regulator is required for Drosophila nurse cell DNA replication and apoptosis. Mech. Dev. 119, 225–237 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rai M., et al. , The Drosophila melanogaster enzyme glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 is required for oogenesis, embryonic development, and amino acid homeostasis. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 12, jkac115 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matsuoka S., Armstrong A. R., Sampson L. L., Laws K. M., Drummond-Barbosa D., Adipocyte metabolic pathways regulated by diet control the female germline stem cell lineage in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 206, 953–971 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang D., et al. , Metabolic regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature 574, 575–580 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nicolay B. N., et al. , Loss of RBF1 changes glutamine catabolism. Genes Dev. 27, 182–96 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zappia M. P., Frolov M. V., Islam A. B. M. M. K., E2F regulation of Phosphoglycerate kinase (Pgk) gene is functionally important in Drosophila development. Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE217225. Deposited 3 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (XLSX)

Dataset S02 (XLSX)

Dataset S03 (XLSX)

Dataset S04 (XLSX)

Dataset S05 (XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

ATAC-seq data from this publication have been deposited to the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and assigned the identifier Series GSE217225 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE217225) (56). All other data are included in the manuscript and/or SI Appendix.