Abstract

We describe a gas-phase approach for the rapid screening of polypeptide anions for phosphorylation or sulfonation based on binding strengths to guanidinium-containing reagent ions. The approach relies on the generation of a complex via reaction of mixtures of deprotonated polypeptide anions with dicationic guanidinium-containing reagent ions and subsequent dipolar DC collisional activation of the complexes. The relative strengths of the electrostatic interactions of guanidinium with deprotonated acidic sites follows the order carboxylate<phosph(on)ate<sulf(on)ate. The differences between the binding strengths at these sites allows for the use of an appropriately selected dipolar DC amplitude to lead to significantly different dissociation rates for complexes derived from unmodified peptides versus phosphorylated and sulfated peptides. The difference in binding strengths between guanidinium and phosph(on)ate versus guanidinium and sulf(on)ate is sufficiently great to allow for the dissociation of a large fraction of phosphopeptide complexes with the dissociation of a much smaller fraction of sulfopeptide complexes. DFT calculations and experimental data with model peptides and with a mixture of tryptic peptides spiked with phosphopeptides are presented to illustrate and support this approach. Dissociation rate data are presented that demonstrate the differences in binding strengths for different anion charge-bearing sites and that reveal the DDC conditions most likely to provide the greatest discrimination between unmodified peptides, phosphopeptides, and sulfopeptides.

Keywords: Phosphopeptide, sulfopeptide, ion/ion reaction, charge inversion, dipolar DC collisional activation

Introduction

Protein post-translational modifications (PTMs) increase the functional diversity as well as the overall complexity of the proteome. Phosphorylation is one of the most abundant PTMs present in proteomes with as much as a third of eukaryotic proteins estimated to be phosphorylated.1 Phosphorylation plays a central role in signaling and regulatory process and, as a result, phosphoproteomics is widely practiced.2,3 A common phosphoproteomics strategy involves a bottom-up work flow that relies on enrichment and/or separation using liquid chromatography and structural characterization via tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) techniques.4 Enrichment prior to analysis is typically used, as phosphorylation is a low stoichiometry modification and must be separated from the high backgrounds of non-phosphorylated peptides. Enrichment strategies such as immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) and metal oxide affinity chromatography (MOAC) are common metal-based affinity chromatography methods. Evaluation of other affinity materials, such as amine-based species, is also being undertaken but traditional metal-based affinity chromatography remain dominant.5

Phosphopeptide analyses typically involve positive ionization in conjunction with MS/MS using one or more activation methods. Collision induced dissociation (CID) remains the most popular activation method for peptide sequencing, based partly on its widespread availability, but is ill-suited for phosphopeptide analysis due to the lability of the phosphate bond, which often leads to loss of the PTM.6 This is particularly problematic with ion trap CID and somewhat less so with beam-type CID and higher energy collisional activation (HCD), the latter of which tend to lead to greater contributions from amide bond cleavages.7 Electron-based activation methods, such as electron transfer dissociation (ETD) and electron capture dissociation (ECD) preserve PTMs on peptides while cleaving the N-Cα bond to form c- and z-type ions allowing determination of the PTM location.8,9 Negative mode ESI holds potential for phosphopeptide analysis as the presence of the acidic phosphate group facilitates efficient ionization in the negative mode.10 However, similar issues with slow heating methods, such as ion trap CID, prevail in the negative mode where the PTMs are first lost upon dissociation. Alternative activation strategies for negative mode structure determination of phosphopeptides, such as negative electron transfer dissociation (nETD) and electron detachment dissociation (EDD), have since been described and applied.11,12

Sulfonation is another PTM that appears in the proteome, although at a lesser abundance compared to phosphorylation and is less extensively studied. Sulfonation primarily appears at tyrosine whereas phosphorylation primarily occurs at tyrosine, serine, and threonine. Tyrosine sulfonation is present in secretory and transmembrane proteins and has been shown to play a role in modulating extracellular protein-protein interactions for a variety of physiological and pathogenic responses.13,14 Sulfoproteomics research is hampered by the lack of an effective enrichment method and difficulties in distinguishing sulfopeptides from phosphopeptides in the mass spectrometer. Metal based IMAC methods have been applied for enrichment of sulfopeptides but lack the specificity that has been shown for phosphopeptides.15 Application of novel antibodies for sulfopeptide enrichment has shown remarkable specificity for sulfotyrosine peptides and discrimination from phosphopeptides as well as sulfated glycans.16 However, antibody enrichment has not been broadly adapted due to costs and concerns about their structural stability. Weak anion exchange chromatography has also been used for enrichment of sulfopeptides but modifications at the primary amines are required for better specificity.17,18

The mass changes associated with sulfonation and phosphorylation are isobaric with the mass difference being only 9.5 mDa. Unless equipped with high resolution/high mass measurement accuracy mass spectrometers, such as an Orbitrap or FT-ICR, it can be challenging to distinguish between a given peptide that is either phosphorylated or sulfonated on the basis of mass. Both forms of modified peptide fragment similarly using low energy CID where major isobaric neutral losses occur (i.e., nominal losses of 80 Da (SO3 or HPO3) or −98 Da (H2SO4 or H3PO4)). While research has been done in comparing the spectra of ions derived from sulfopeptides and phosphopeptides under a variety of activation conditions, unless there is a comprehensive spectral library of sulfopeptides vs. phosphopeptides it remains challenging to distinguish a sulfopeptide from a phosphopeptide on the basis of fragmentation.19

We have investigated gas-phase charge inversion reactions via ion/ion chemistry as means for addressing measurement challenges in mass spectrometry. For example, we demonstrated charge-inversion reactions applied to ions derived from precipitated blood plasma to result in a 200-fold improvement in signal-to-noise ratio due to a significant reduction in chemical noise.20 Charge-inversion has also been used to separate isomeric phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine lipids21 as well as to facilitate location of double bonds in unsaturated fatty acids.22 Here we present another gas-phase ion/ion charge-inversion technique that allows for the distinction of phospho- and sulfopeptides from unmodified peptides as well as from each other. Research has demonstrated a relatively strong noncovalent interaction between guanidinium and phosphate and sulfate groups in both solution and in the gas phase.23,24,25,26 Histidine interactions with acidic sites have also been studied and found to be somewhat weaker than those of guanidinium.27 We seek to exploit the differences in the strengths of electrostatic interactions between guanidinium and deprotonated acidic sites (i.e., carboxylate vs. phosph(on)ate vs. sulf(on)ate) in the context of ion/ion reactions. Ion/ion reactions are induced between singly-charged peptide anion mixtures and a guanidinium containing peptide dication. The resulting cationic peptide complex is then subjected to a broadband collisional activation using dipolar DC (DDC).28 The binding strength between the two peptides in the long-lived complex is dependent upon specific functional group interactions such that the complex stabilities are composition-dependent. This allows DDC to serve as an ‘energy filter’ to assist in the distinction of the functional groups involved in binding. We demonstrate this approach with model phosphopeptides and a sulfopeptide in both a simple mixture and a more complex mixture of tryptic ubiquitin peptides spiked with a phosphopeptide.

Experimental Section

Materials.

Peptides YGGFL, GAIDDL, NVVQIY, pSGGFL, pTGGFL, pYGGFL, and sYGGFL were custom synthesized by Biomatik (Wilmington, DE, USA). The custom peptides AAARAAARA and RKRARKA were synthesized by NeoBioLab (Cambridge, MA, USA). Water, Optima™ LC/MS Grade, was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Ubiquitin from bovine erythrocytes and trypsin from bovine pancreas were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). All solutions for nanoelectrospray (nESI), using capillaries pulled to tip diameter 3–4 µm, were prepared in an aqueous solution at an initial concentration of ~1 mg/ml and diluted to desired concentration before use. The final concentration of each peptide in the peptide mixtures in aqueous solution is between 3 µM and 30 µM.

Trypsin digestion.

Approximately 1 mg of ubiquitin was dissolved in 500 uL of 50 mM NH4HCO3. A trypsin solution of 1 mg/mL was added to the protein solution at a 1:40 mass ratio. The solution was incubated at 37 °C for 12 hours before evaporated to dryness using a vacuum centrifuge. The resulting product was reconstituted in 500 uL water.

N-terminal acetylation.

Approximately 0.5 mg of peptide was dissolved in 250 µL water before 15 µL of 5 mM pH 6–7 borate buffer and 20 µL of acetic anhydride were added. The solution was left at room temperature and allowed to react for 2 hours before quenching the reaction with 2 µL glacial acetic acid. The resulting solution was evaporated to dryness using a vacuum centrifuge before being reconstituted in 500 µL water.

Mass spectrometry.

All experiments were performed on a TripleTOF 5600 mass spectrometer (SCIEX, Concord, ON, Cananda) modified for ion/ion reactions and dipolar DC (DDC), in analogy with a previously described Q-TOF instrument.29,30 Both reagent and analyte ions were formed via nano-electrospray emitters placed before the inlet aperture of the atmosphere vacuum interface. Cations and anions were formed alternately by pulsing the respective electrospray emitters.31 For ion/ion reactions, the doubly protonated reagent was isolated by Q1 and accumulated in the q2 reaction cell before the negatively charged analyte ions were generated and introduced into q2. The oppositely charged ions were allowed to react within q2 for 20 ms. After mutual storage, a ramped ion trap resonance ejection scan was performed to eject remaining reagent and proton transfer products thereby leaving only the complex ions within q2. In the experiments associated with Figures 2–4, a subsequent dipolar DC (DDC) excitation at a fixed amplitude was applied for 200 ms when the q2 RF voltage is set to be 250 m/z at a q value of 0.908 (i.e., low-mass cutoff = m/z 250) for broadband activation of the isolated complexes.

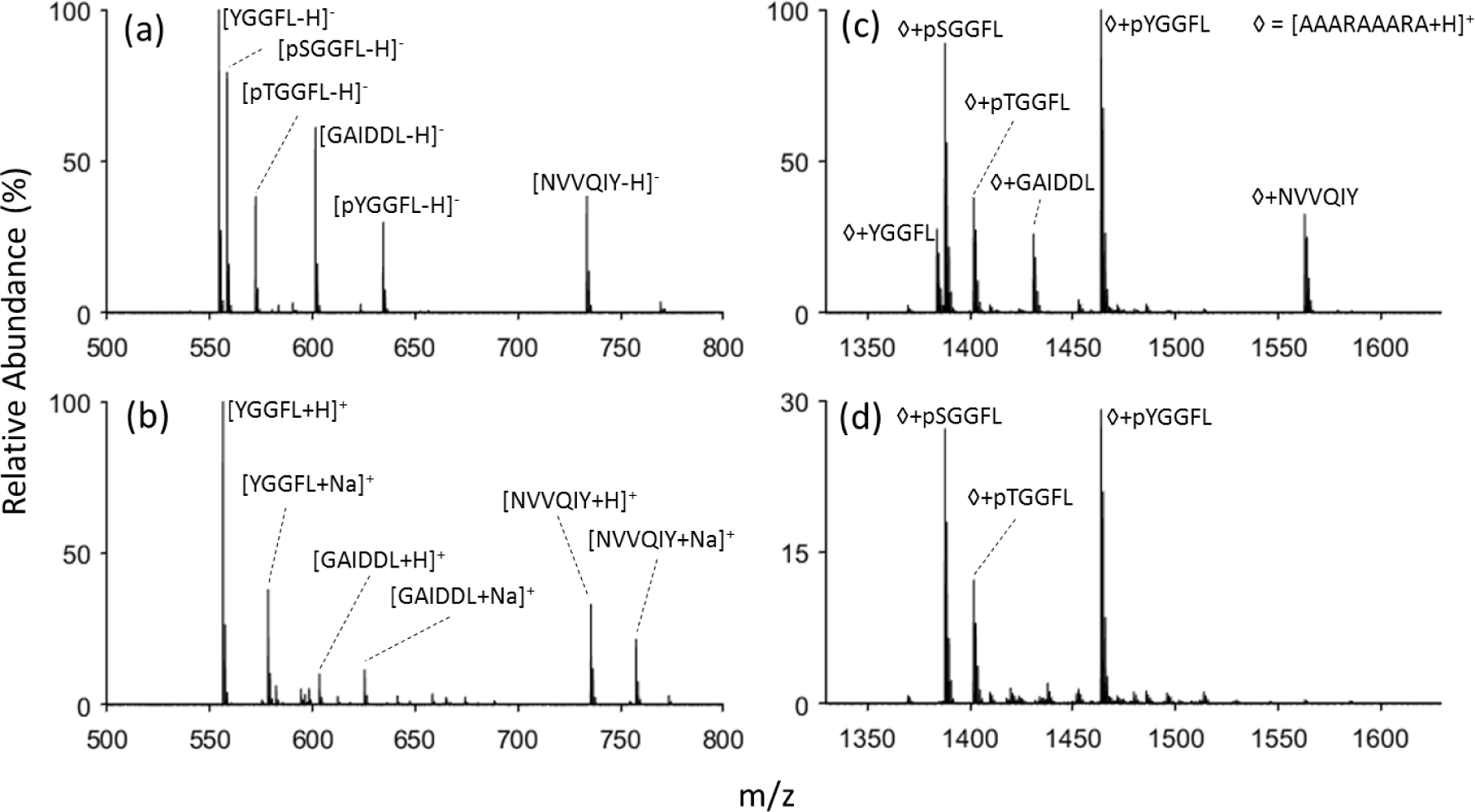

Figure 2.

Nanoelectrospray of six peptide mixture containing three phosphoepeptides in (a) negative mode and (b) positive mode. Charge-inversion ion/ion reaction of the anionic peptide mixture with [AAARAAARA+2H]2+ (c) with no DDC applied, and (d) DDC voltage of 22 volts applied.

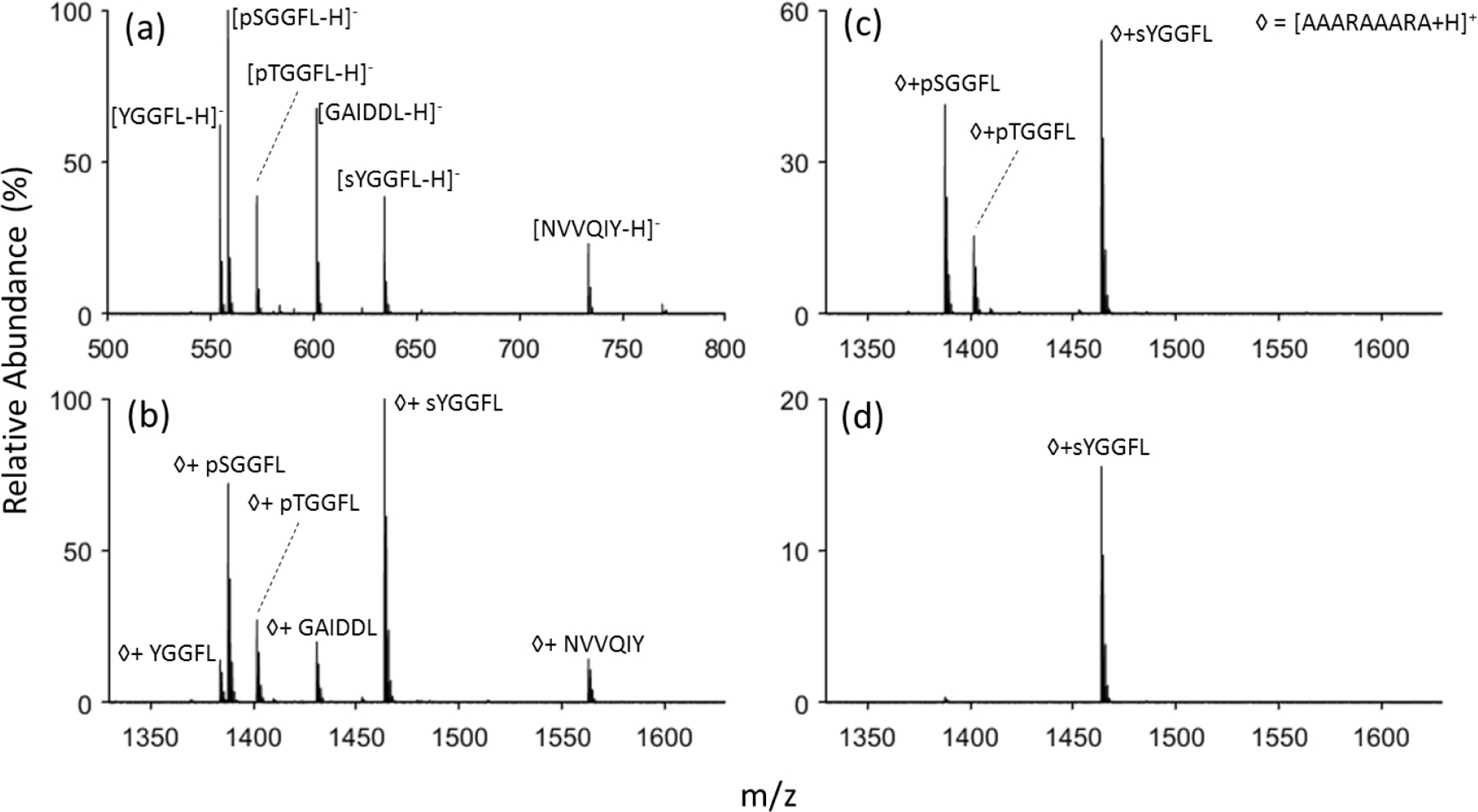

Figure 4.

(a) Negative mode nanoelectrospray of a sulfopeptide, sYGGFL, two phosphopeptides, pTGGFL and pSGGFL, and three non-PTM peptides, YGGFL, GAIDDL, and NVVQIY. (b) Post-ion/ion reaction spectrum of the anionic peptide mixture with [AAARAAARA+2H]2+ followed by (c) DDC using 22 V and (d) 25 V.

Dipolar DC Dissociation Kinetics.

The rates of complex ion dissociation follow pseudo first order kinetics under DDC conditions, as indicated in Equation 1:28,32,33,34

| (1) |

where [M]t is the molar fraction of the complex at time t, and kdiss is the pseudo-first order dissocation rate of the ion. The molar fraction of the complex is calculated as the ratio of complex ion’s abundance over the abundance of all ions present. Complex ion dissociation kinetics were determined at a fixed RF amplitude (low-mass cutoff = m/z 250) as a function of dipolar DC amplitude. For a given DC and RF amplitude, the dissociation rate for a complex ion is determined from fitting the data to Equation 2:

| (2) |

In all cases, the dominant fragment ion generated from DDC collisional activation of the complexes in this work was the protonated reagent. Error bars for kdiss correspond to the standard deviation from the linear fitting to Equation 2.

Density functional theory calculations.

All optimizations and zero-point corrected energies (ZPE) were performed using the Gaussian 09 package35 at the B3LYP/6-311++G(2d,p) level of theory. As the molecules are small, all structures were directly optimized in Gaussian 09. The anions and cations as well as their respective neutral forms were individually optimized for structure. The complex structure is a combination of the optimized anions and cations further subjected to optimizations.

Results and Discussion

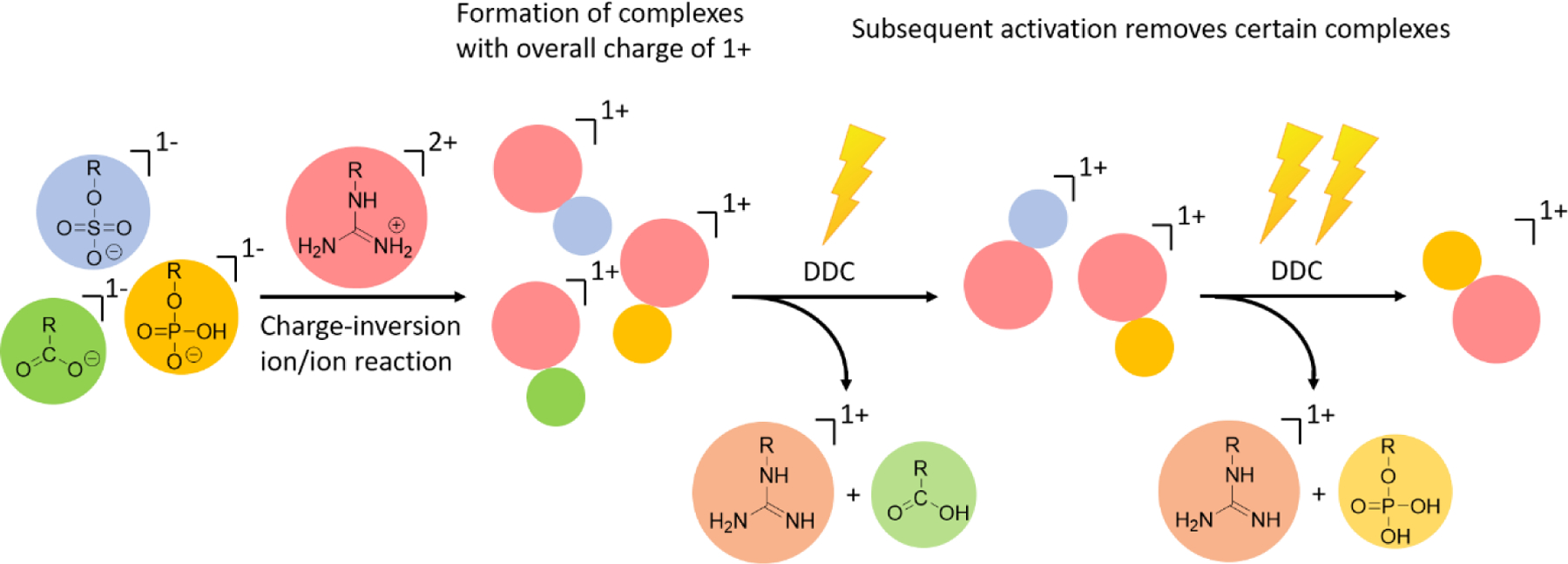

The general approach for screening of mixtures of anionic peptides with carboxylate, phosph(on)ate, or sulf(on)ate charge bearing sites is summarized schematically below:

The approach is based on reacting primarily singly-charged peptide anions with a doubly-charged cationic reagent that contains at least one arginine residue or, in this work, two protonated arginine residues. Of all the basic residues of the common amino acids, arginine has the highest proton affinity36,37 and engages in the strongest electrostatic interactions with anionic sites. Reagent dications with arginine residues are therefore more likely to react with anions to yield a complex ion, rather than undergo proton transfer. It is also advantageous for the reagent cation to be relatively large, which increases the cross-section for intimate collision. The first step of the process is therefore intended to generate singly positively charged complexes comprised of the analyte anions attached to the doubly protonated reagent. The most weakly-bound complexes can be preferentially fragmented by the judicious choice of dipolar DC amplitude while the more strongly-bound complexes survive. Provided there is a sufficiently large difference between the binding strengths associated with the different anionic charge sites, the dipolar DC conditions can be used to distinguish between the types of anionic peptides. We show below that, according to DFT calculation, complex stability based on the electrostatic interaction between a guanidinium moiety (e.g., a protonated arginine residue) and a deprotonated site increase in the order carboxylate<phosph(on)ate<sulf(on)ate. We then demonstrate that dipolar DC conditions can be established that are able to distinguish phospho- and sulfopeptides from unmodified peptides and from one another.

Density functional theory calculations of guanidinium interactions.

The key characteristic of interest here is the gas-phase binding strength between the negatively charged peptide analytes and the positively charges dicationic reagent. Acid-base chemistry generally dominates in electrospray ionization such that excess protons are localized on the most basic sites of a peptide, such as the N-terminus or lysine, arginine, and histidine side-chains, in positive ion mode and at acidic sites, such as the C-terminus or aspartic, and glutamic acid side-chains, in negative ion mode. That logic can be further extended in the presence of PTMs such as phosphorylation and sulfonation. Phosphate and sulfate groups have a lower pKa values than carboxylate groups, which makes them more likely to be the charge site when ionized in the negative mode. Hence, a carboxylate group is likely to be the moiety involved in the interaction with a cationic reagent for unmodified peptides whereas for the phosphopeptides and sulfopeptides the charge site will be at the phosphate or sulfate groups, respectively. Density functional calculations were used to quantify the binding strength between the different types of negatively charged (i.e. carboxylate, sulfonate, phosphonate) and positively charged (i.e. primary amine, imidazole, guanidinium) chemical groups in the context of ion/ion reactions. A generic Brauman-type energy diagram (i.e., reactants shown from the left, products shown on the right, intermediate shown in the middle) for doubly protonated reagent and a singly deprotonated analyte proceeding via a long-lived complex is shown in Figure 1(a). A more detailed analysis of energy surfaces for ion/ion reactions has been previously discussed.34 In this case, reactions that proceed through a relatively long-lived intermediate (i.e., a complex) are of particular interest. (Proton transfer at a crossing point without formation of a complex is possible at large impact parameters and is minimized when the physical cross-sections of the reactants are large.34) Complex formation is always thermodynamically favorable in this type of reaction by roughly 100 kcal/mol per pair of opposite charges. The lowest energy exit channel from the complex involves proton transfer to lead to a singly protonated product and a neutral product. The barrier to proton transfer from the complex is largely determined by the strength of the electrostatic interaction between the relevant protonated and deprotonated sites. The calculated energy barriers for proton transfer from a basic group cation to each of the three anionic groups of interest are listed in the table of Figure 1(b). The energies calculated via DFT shown in the table are the difference between the zero-point corrected energies (ZPE) of the complex and the sum of the two neutrals after proton transfer has occurred. (Reverse critical energies for proton transfer reactions are typically small and are expected to largely cancel so that the calculated values here are expected to be suitable for comparisons.) The calculations clearly show that interaction strength between guanidinium and the various negative charge sites follow the order sulf(on)ate>phosph(on)ate>carboxylate. For a given anionic site, the binding strengths for the cationic sites follows the order guanidinium>imidazole>primary amine. The energy-minimized structures of the complexes formed between the various cations and anions are provided in Figures S1–S7. (Protonated imidazole/carboxylate and protonated methylamine/carboxylate complexes were not found to be lower in energy than the proton transfer products and are therefore not shown in Supplemental Information.)

Figure 1.

(a) A generic energy diagram for a proton transfer ion/ion reaction involving a doubly-protonated reagent (blue) and a singly-deprotonated analyte (red). The reactants undergo a long-range attraction due to the Coulombic potential and, if they undergo an intimate collision, form a relatively long-lived complex. The complex can break up spontaneously to yield charged (yellow) and neutral (green) proton transfer products or the complex can be stabilized via collisions and/or emission. (b) The interaction strength between three basic groups and three deprotonated acids calculated via DFT. The model is a simplified version where only the interaction between positively charged basic groups and the negatively charged acidic groups are probed. The binding strength is the zero-point corrected energy difference between the complex and the sum of the products after proton transfer.

Complex formation and DDC for phosphopeptides vs. unmodified peptides.

Model phosphopeptides, pSGGFL, pTGGFL, and pYGGFL, as well as a variety of other small model peptides of similar size, YGGFL, GAIDDL, and NVVQIY, were used to evaluate the relative stabilities of complexes formed with a doubly protonated reagent with two arginine residues. Mass spectra of this peptide mixture in both positive mode and negative mode nESI are shown in Figures 2(a) and (b), respectively. In the positive mode spectrum, signals from the phosphopeptides are essentially absent as only the protonated and sodiated versions of unmodified peptides are present. In contrast, the three phosphopeptides give rise to strong signals in the negative ion mode. Ion/ion reaction between the negatively charged peptides and doubly-protonated AAARAAARA formed a long-lived stable complex with 1+ charge that was detected in the positive mode, as shown in Figure 2(c). (Residual reagent cations as well as singly-protonated AAARAAARA generated via proton transfer were ejected by a resonance ejection ramp prior to mass analysis in generating Figure 2(c). The complete spectrum prior to the voltage sweep is shown in Figure S8.) It is clear from a comparison of the relative abundances of the peptide anions (Figure 2(a)) with the relative abundances of the complexes observed in Figure 2(c) that the relative propensities for stable complex formation are peptide anion dependent. Stable complex formation competes with proton transfer at a crossing on the energy surface (without complex formation) and proton transfer via break-up of an initially formed complex.33 The likelihood for the initial formation of a long-lived complex increases with the physical sizes of the reactants (i.e., a larger analyte anion and a larger reagent increase the relative likelihood for a ‘sticky’ collision between the reactants). The relative likelihood for the survival of the initially formed complex, which leads to the observation of a stable complex, is related, in part, to the binding strength in the complex. The factors of peptide anion size and the strengths of the interactions in the complex largely determine the changes in relative abundances in Figures 2(a) and 2(c). Based on the calculations discussed above, the binding strengths of the phosphopeptide complexes are expected to be significantly greater than those involving unmodified peptides. The selective dissociation of the more weakly-bound complexes can be effected via dipolar DDC collisional activation. DDC is a broad-band collisional activation technique that provides a roughly uniform degree of excitation across a wide range of masses.27,31,32 As shown in Figure 2(d), a DDC amplitude of 22 V applied for 200 ms leads to the dissociation of essentially all of the complexes comprised of the unmodified peptides while prominent signals from the phosphopeptide-containing complexes remain. The resulting spectrum provides an illustration for how phosphopeptide anions can be distinguished from unmodified peptide anion via ion/ion complex formation and DDC collisional activation.

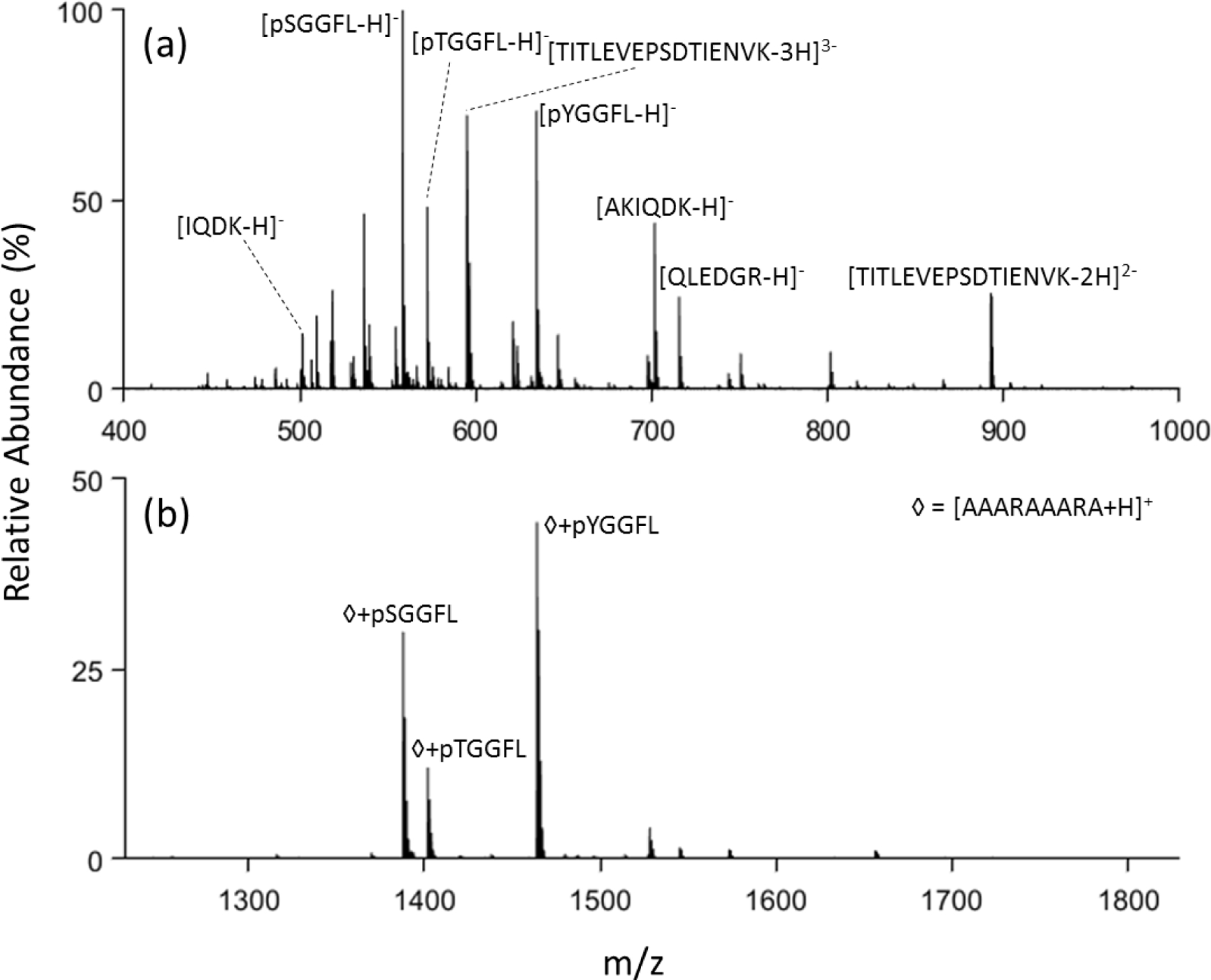

Application of this approach to a more complex sample containing phosphopeptides was also performed. Peptides derived from tryptic digestion of ubiquitin along with phosphopeptides spiked into solution were subjected to analysis. In the positive mode (see Figure S9), very little indication of the presence of the phosphopeptides is apparent while prominent signals are present in the negative mode spectrum (Figure 3(a)). Applying the charge inversion DDC process to the mixture highlights the phosphopeptide anions (Figure 3(b)). It is worthy of note that doubly- and triply-deprotonated TITLEVEPSDTIENVK ions, one of the ubiquitin tryptic peptides, are prominent in Figure 3(a). The doubly-deprotonated ion would be neutralized as a result of complex formation and the triply-deprotonated species would form a negatively charged complex. Therefore, evidence for this peptide would not be expected via a single ion/ion reaction. However, there are several pathways for generating cations with this peptide via two ion/ion reactions, such as a single proton transfer to the di-anion followed by reagent cation attachment. However, there is no evidence that any TITLEVEPSDTIENVK-containing cations survived the DDC experiment associated with Figure 3(b).

Figure 3.

(a) Negative mode nanoelectrospray of trypsin digested ubiquitin with phosphopeptides pSGGFL, pTGGFL, and pYGGFL spiked in and (b) post ion/ion reaction with DDC at 22 V applied.

Complex formation and DDC for phosphopeptides vs. sulfopeptides.

Substituting sYGGFL for pYGGFL in the model peptide mixture of Figure 2 and repeating the ion/ion reaction experiment showed that the reagent cation formed a stable complex with the sulfopeptide in analogy with the phosphopeptides (see Figure 4(a)). Application of 22 V DDC, as above, resulted in the survival of only the phosphopeptide and sulfopeptide complexes. Application of 25 V DDC for the same time (200 ms) resulted in the disappearance of almost all of the phosphopeptide complexes while retaining a significant fraction of the sulfopeptide containing complexes. This result is consistent with the expectation that the stronger binding for sulf(on)ate relative to phosph(on)ate to guanidinium, as predicted by the DFT calculations, leads to more stable electrostatic complexes. The differences in binding strengths for the three anionic sites discussed here suggests that the amplitude of DDC applied to complexes generated in reaction with guanidinium-containing reagents can be used to distinguish between unmodified peptides and modified peptides at intermediate values and between phosphopeptides and sulfopeptides at higher DDC values.

DDC dissociation kinetics.

Differences in complex dissociation rates form the basis for the use of DDC to discriminate between different classes of anions (i.e., carboxylate, phosph(on)ate, sulf(on)ate). In order to evaluate reagents and conditions for optimal discrimination between anion classes, it is instructive to determine complex ion dissociation rates over a range of conditions. Figure 5(a) shows a series of kinetic plots at various DDC amplitudes for the complex formed from deprotonated pYGGFL and doubly-protonated AAARAAARA. Examples of the spectra collected at 23 V DDC across various activation times are shown in Figure S10. Figure 5(b) summarizes the dissociation rates of the complexes formed from ion/ion reaction between doubly protonated AAARAAARA and deprotonated YGGFL, GAIDDL, pTGGFL, pSGGFL, pYGGFL, and sYGGFL. It is clear that the complexes of the unmodified peptides YGGFL and GAIDDL fragment at the lowest DDC amplitudes, which is consistent with the DFT calculations that show relatively weak interaction between guanidinium and carboxylate. With three acidic sites in GAIDDL, the opportunity for additional interactions in the complex likely underlies the requirement for higher DDC voltages to achieve dissociation rates similar to the complex with YGGFL. The complexes derived from three phosphopeptides show similar dissociation kinetics while the sulfopeptide complex requires significantly higher DDC voltages. Figure 5(b) shows why a DDC amplitude of 22 V is effective in destroying the complexes comprised of the unmodified peptides while the complexes of the modified peptides largely survive. Likewise, a DDC amplitude of 25 V is effective in destroying the complexes of the unmodified and phosphorylated peptides while the suflopeptide complex remains intact.

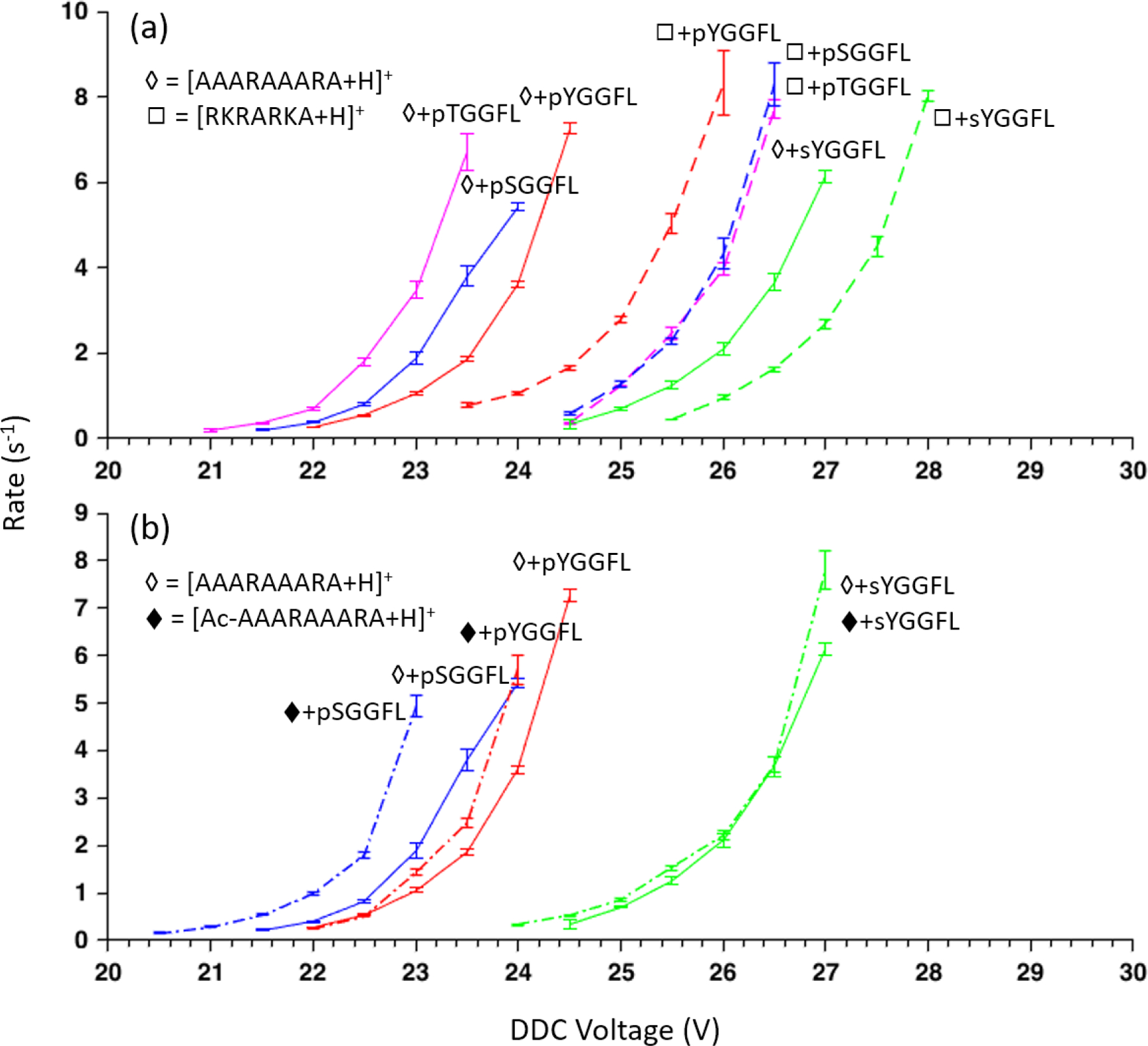

Figure 5.

(a) The kinetic data for determining the dissociation rate of the peptide complex between [pYGGFL-H]− and [AAARAAARA+2H]2+. The natural log of the peak area of the complex over the peak area of the total ion current (TIC) is plotted against the activation time of DDC. (b) The complex dissociation rate of each peptide complex, kdiss, is plotted against the DDC voltage. The error bar is two standard deviations of the slope’s fitting error in the kinetic data.

The rate data of Figure 6 illustrate how the measurement of DDC kinetics can be used to evaluate the discriminatory value of a reagent cation. Figure 6(a), for example, summarizes the dissociation rate data obtained using doubly protonated RKRARKA as the reagent for deprotonated pYGGFL, pTGGFL, pSGGFL, and sYGGFL. For comparison, the rate data for the doubly-protonated AAARAAARA reagent are also provided. The more basic reagent (i.e., RKRARKA) leads to more stable complexes for all of the peptides, as reflected by the shift of the rate data to the right on the DDC amplitude scale. In the case of the phosphopeptides, the stability order changed from the pYGGFL/AAARAAARA complex being the most stable of the three AAARAAARA complexes to being the least stable of the peptide/RKRARKA complexes. This observation highlights the importance of the additional interactions that are introduced by the incorporation of another arginine residue and two lysine residues. The sulfopeptide/RKRARKA complex was found to be significantly more stable than those of all of the phosphopeptides. However, the separation between the phosphopeptides and the sulfopeptide on the DDC scales was narrower with the RKRARKA reagent than with the AAARAAARA reagent. Overall, therefore, doubly-protonated AAARAAARA appears to be a more discriminatory reagent cation for phospho- versus sulfopeptides.

Figure 6.

(a) Kinetic data comparison between peptide complexes of AAARAAARA (◊) and RKRARKA (◻) for three phosphopeptides and a sulfopeptide. Kinetic data for AAARAAARA complexes are solid lines and dashed lines for RKRARKA complexes. (b) Kinetic data comparison of select peptides between AAARAAARA (◊) and Ac-AAARAAARA (♦). The error bar is two standard deviations of the slope’s fitting error in the kinetic data.

The comparison of Figure 6(a) suggests that interactions beyond those of a single guanidinium cation with a deprotonated acidic site can have a measureable effect on complex stability and can impact the discriminatory value of a doubly-protonated reagent for distinguishing between unmodified peptides and phospho- and sulfopeptides. Figure 6(b) compares DDC rate data for doubly-protonated AAARAAARA and N-terminally acetylated AAARAAARA to determine a possible role for the N-terminus in stabilizing the complexes with deprotonated pYGGFL, pSGGFL, and sYGGFL. Interestingly, neither of the tyrosine-containing peptide complexes showed a significant change in dissociation kinetics when the reagent peptide was N-terminally acetylated while the pSGGFL complex was observed to be less stable. This result suggests that the serine residue of pSGGFL interacts with the N-terminus in complexes with AAARAAARA more strongly than the tyrosine residues of pYGGFL and sYGGFL. It is beyond the scope of this work to examine all of the possible interactions that might take place in a complex formed between reagent and analyte polypeptides. In any case, in order to maximize the contribution from the targeted guanidinium/deprotonated acid interaction to the overall binding strength of the complex, it is desirable to minimize the possibility for other strong non-covalent interactions. Along these lines, competition between fragmentation of covalent bonds and cleavage of the phosphate-guanidinium bond in some peptide complexes has been noted under low energy collision conditions,26,38 as has intermolecular phosphate transfer between complex components.39,40 No evidence for such processes for either the phospho- or sulfo-peptides was observed in the DDC step in this work but these possibilities should be recognized when examining other reagent/peptide combinations.

Conclusions

This work provides proof-of-concept for an ion/ion reaction approach to distinguishing between unmodified, phosphorylated, and sulfated peptides. The basis for discrimination is the relative strengths of interaction between guanidinium and carboxylate, phosph(on)ate, and sulf(on)ate in the gas phase. The relative strengths of the electrostatic interactions between guanidinium and conjugate bases of the relevant acidic sites, determined by DFT calculations and supported experimentally, increase in the order carboxylate<phosph(on)ate<sulf(on)ate. The interaction is generated by reacting a doubly protonated reagent peptide with at least two arginine residues with singly deprotonated peptides in the gas phase to form a long-lived complex. The relative stabilities of the complexes are probed via dipolar DC (DDC) collisional activation, a broad-band collisional excitation technique. With an appropriately selected DDC amplitude and time, it was shown to be possible to fragment a large majority of complexes comprised of unmodified peptide anions while retaining large fractions of complexes comprised of phosphopeptides and sulfopeptides. Likewise, at a higher DDC amplitude, it was possible to fragment a large majority of phosphopeptide complexes while preserving a large fraction of the sulfopeptide complexes. The discriminatory value of the reagent and DDC conditions is readily apparent from dissociation kinetics experiments that provide dissociation rates as a function of DDC amplitude for a fixed RF amplitude. Such data point to DDC conditions that provide the greatest degree of discrimination between anion types and are useful in evaluating reagent cations used to generate complexes. The results shown here highlight the roles that non-covalent interactions other than the guanidinium-anion interaction can affect complex ion stabilities. To maximize the role of the guanidinium interaction and to avoid other interactions that may vary with the analyte ion sequence/composition, it is desirable to minimize the presence of polar groups other than the arginine residues.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 1 –

Schematic depiction of the use of a guanidinium-containing dicationic reagent and dipolar DC collisional activation for the discrimination between carboxylate, phosp(on)ate, and sulf(on)ate containing peptide anions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Grant GM R37-45372.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Additional information on supporting mass spectral data, DFT calculations with other cation types, and calculated structures of complexes.

References

- 1.Cohen P The regulation of protein function by multisite phosphorylation – a 25 year update, Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2000, 25, 596–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ubersax JA; Ferrell JE Jr. Mechanisms of specificity in protein phosphorylation, Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 2007, 8, 530–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen P The origins of protein phosphorylation, Nat. Cell. Biol 2002, 4, E127–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riley NM; Coon JJ Phosphoproteomics in the Age of Rapid and Deep Proteome Profiling, Anal Chem 2016, 88, 74–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang ZG; Lv N; Bi WZ; Zhang JL; Ni JZ Development of the affinity materials for phosphorylated proteins/peptides enrichment in phosphoproteomics analysis, ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2015, 7, 8377–8392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brodbelt JS Ion Activation Methods for Peptides and Proteins, Anal. Chem 2016, 88, 30–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jedrychowski MP; Huttlin EL; Haas W; Sowa ME; Rad R; Gygi SP Evaluation of HCD- and CID-type fragmentation within their respective detection platforms for murine phosphoproteomics, Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2011, 10, M111 009910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chi A; Huttenhower C; Geer LY; Coon JJ; Syka JE; Bai DL; Shabanowitz J; Burke DJ; Troyanskaya OG; Hunt DF Hunt, Analysis of phosphorylation sites on proteins from Saccharomyces cerevisiae by electron transfer dissociation (ETD) mass spectrometry, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 2193–2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stensballe A; Jensen ON; Olsen JV; Haselmann KF; Zubarev RA Electron capture dissociation of singly and multiply phosphorylated peptides, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 2000, 14, 1793–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flora JW; Muddiman DC Selective, Sensitive, and Rapid Phosphopeptide Identification in Enzymatic Digests Using ESI-FTICR-MS with Infrared Multiphoton Dissociation, Anal Chem 2001, 73, 3305–3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Budnik BA; Haselmann KF; Zubarev RA Electron detachment dissociation of peptide di-anions: an electron–hole recombination phenomenon, Chem. Phys. Lett 2001, 342, 299–302. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coon JJ; Shabanowitz J; Hunt DF; Syka JE Electron transfer dissociation of peptide anions, J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2005, 16, 880–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore KL Protein tyrosine sulfation: a critical posttranslation modification in plants and animals, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 14741–14742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang YS; Wang CC; Chen BH; Hou YH; Hung KS; Mao YC Tyrosine sulfation as a protein post-translational modification, Molecules 2015, 20, 2138–2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demesa Balderrama G; Meneses EP; Hernandez Orihuela L; Villa Hernandez O; Castro Franco R; Pando Robles V; Ferreira Batista CV Analysis of sulfated peptides from the skin secretion of the Pachymedusa dacnicolor frog using IMAC-Ga enrichment and high-resolution mass spectrometry, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 2011, 25, 1017–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffhines AJ; Damoc E; Bridges KG; Leary JA; Moore KL Detection and purification of tyrosine-sulfated proteins using a novel anti-sulfotyrosine monoclonal antibody, J. Biol. Chem 2006, 281, 37877–37887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amano Y; Shinohara H; Sakagami Y; Matsubayashi Y Ion-selective enrichment of tyrosine-sulfated peptides from complex protein digests, Anal Biochem 2005, 346, 124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson MR; Brodbelt JS Integrating Weak Anion Exchange and Ultraviolet Photodissociation Mass Spectrometry with Strategic Modulation of Peptide Basicity for the Enrichment of Sulfopeptides, Anal. Chem 2016, 88, 11037–11045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen G; Zhang Y; Trinidad JC; Dann C III Distinguishing Sulfotyrosine Containing Peptides from their Phosphotyrosine Counterparts Using Mass Spectrometry, J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2018, 29, 455–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hassell KM; LeBlanc Y; McLuckey SA Conversion of multiple analyte cation types to a single analyte anion type via ion/ion charge inversion, The Analyst 2009, 134, 2262–2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rojas-Betancourt S; Stutzman JR; Blanksby SJ; McLuckey SA Gas-Phase Chemical Separation of Phosphatidylcholine and Phosphatidylethanolamine Cations via Charge Inversion Ion/Ion Chemistry, Anal. Chem 2015, 87, 11255–11262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Randolph CE; Foreman DJ; Betancourt SK; Blanksby SJ; McLuckey SA Gas-Phase Ion/Ion Reactions Involving Tris-Phenanthroline Alkaline Earth Metal Complexes as Charge Inversion Reagents for the Identification of Fatty Acids, Anal. Chem 2018, 90, 12861–12869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schug KA; Lindner W Noncovalent binding between guanidinium and anionic groups: focus on biological- and synthetic-based arginine/guanidinium interactions with phosph[on]ate and sulf[on]ate residues, Chem. Rev 2005, 105, 67–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson SN; Wang HY; Yergey A; Woods AS Phosphate stabilization of intermolecular interactions, J. Proteome Res 2006, 5, 122–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patrick AL; Polfer NC H2SO4 and SO3 transfer reactions in a sulfopeptide-basic peptide complex, Anal. Chem 2015, 87, 9551–9554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woods AS; Moyer SC; Jackson SN Amazing stability of phosphate-quaternary amine interactions, J. Proteome Res 2008, 7, 3423–3427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muller L; Jackson SN; Woods AS Histidine, the less interactive cousin of arginine, Eur. J. Mass Spectrom 2019, 25, 212–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tolmachev AV; Vilkov AN; Bogdanov B; Pasa-Tolic L; Masselon CD; Smith RD Collisional activation of ions in RF ion traps and ion guides: the effective ion temperature treatment, J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2004, 15, 1616–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xia Y; Chrisman PA; Erickson DE; Liu J; Liang X; Londry FA; Yang MJ; McLuckey SA Implementation of Ion/Ion Reactions in a Quadrupole/Time-of-Flight Tandem Mass Spectrometer, Anal. Chem 2006, 78, 4146–4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Webb IK; Londry FA; McLuckey SA Implementation of Dipolar DC CID in Storage and Transmission Modes on a Quadrupole/Time-of-Flight Tandem Mass Spectrometer, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 2011, 25, 2500–2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xia Y; Liang X; McLuckey SA Pulsed Dual Electrospray Ionization for Ion/Ion Reactions. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2005, 16, 1750–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prentice BM; Santini RE; McLuckey SA Adaptation of a 3-D Quadrupole Ion Trap for Dipolar DC Collisional Activation, J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2011, 22, 1486–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prentice BS; McLuckey SA Dipolar DC Collisional Activation in a “Stretched” 3-D Ion Trap: The Effect of Higher Order Fields on RF-heating, J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2012, 23, 736–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bu J; Fisher CM; Gilbert JD; Prentice BM; McLuckey SA Selective Covalent Chemistry via Gas-Phase Ion/ion Reactions: An Exploration of the Energy Surfaces Associated with N-Hydroxysuccinimide Ester Reagents and Primary Amines and Guanidine Groups. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2016, 27, 1089–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frisch MJ; Trucks GW; Frisch MJ; Trucks GW; Schlegel HB; Scuseria GE; Robb MA; Cheeseman JR; Scalmani G; Barone V; Mennucci B; Petersson GA; Nakatsuji H; Caricato M; Li X; Hratchian HP; Izmaylov AF; Bloino J; Zheng G; Sonnenberg JL; Hada M; Ehara M; Toyota K; Fukuda R; Hasegawa J; Ishida M; Nakajima T; Honda Y; Kitao O; Nakai H; Vreven T; Montgomery JA Jr.; Peralta JE; Ogliaro F; Bearpark M; Heyd JJ; Brothers E; Kudin KN; Staroverov VN; Kobayashi R; Normand J; Raghavachari K; Rendell A; Burant J; Iyengar SS; Tomasi J; Cossi M; Rega N; Millam JM; Klene M; Knox JE; Cross JB; Bakken V; Adamo C; Jaramillo J; Gomperts R; Stratmann RE; Yazyev O; Austin AJ; Cammi R; Pomelli C; Ochterski JW; Martin RL; Morokuma K; Zakrzewski VG; Voth GA; Salvador P; Dannenberg JJ; Dapprich S; Daniels AD; Farkas Ö; Foresman JB; Ortiz JV; Cioslowski J; Fox DJ Gaussian 09, Revision A.02, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford, CT, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harrison AG The Gas-Phase Basicities and Proton Affinities of Amino Acids and Peptides, Mass Spectrom. Rev 1997, 16, 201–217. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bleiholder C; Suhai S; Paizs B Revising the Proton Affinity Scale of the Naturally Occurring α-Amino Acids, J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2006, 17, 1275–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laskin J; Yang Z; Woods AS Competition between covalent and noncovalent bond cleavages in dissociation of phosphopeptide-amine complexes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2011, 13, 6936–6946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palumbo AM; Reid GE Evaluation of Gas-Phase Rearrangement and Competing Fragmentation Reactions on Protein Pphosphorylation Site Assignment Using Collision Induced Dissocation MS/MS and MS3, Anal. Chem 2008, 80, 9735–9747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gonzalez-Sanchez M-B, Lanucara F; Hardman GE; Eyers CE Gas-phase intermolecular phosphate transfer within a phosphohistidine phosphopeptide dimer. Int. J. Mass Spectrom 2014, 367, 28–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.